Abstract

The reaction of the previously known bis(6-diphenylphosphinoacenaphthyl-5-)telluride (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2Te (IV) with (CO)5ReCl and (CO)5MnBr proceeded with the liberation of CO and provided fac-(6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeM(X)(CO)3 (fac-1: M = Re, X = Cl; fac-2: M = Mn, X = Br), in which IV acts as bidentate ligand. In solution, fac-1 and fac-2 are engaged in a reversible equilibrium with mer-(6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeM(X)(CO)3 (mer-1: M = Re, X = Cl; mer-2: M = Mn, X = Br). Unlike fac-1, fac-2 is prone to release another equivalent of CO to give (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeMn(Br)(CO)2 (3), in which IV serves as tridentate ligand.

1. Introduction

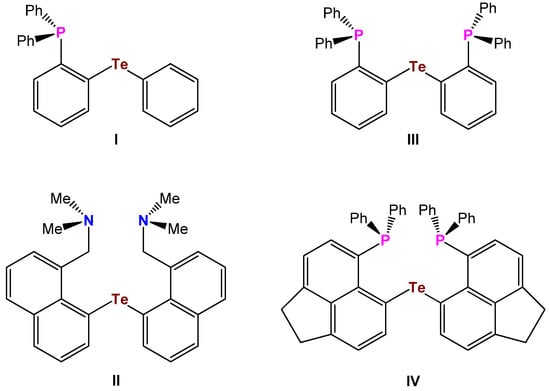

Transition metal complexes composed of multidentate ligands based upon tellurium are far less explored than those of sulfur and selenium, which might be due to the lack of easily available ligands containing tellurium, as well as the historical misconception that organotellurium compounds were extremely malodorous and toxic [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Up to the 1970s, studies of coordination chemistry were mostly restricted to monodentate ligands. The first bidentate telluroether ligand I (Te, P-type) was described by Gysling and Luss in 1984 [9], whereas the first tridentate telluroethers II (N,Te,N-type), and III (P,Te,P-type) were reported by Singh et al. [10] as well as Lin and Gabbaï (Scheme 1) [11].

Scheme 1.

Bidentate and tridentate telluroether ligands I–IV.

In preceding work, we reported on the synthesis of bis(6-diphenylphosphinoacenaphth-5-yl)telluride (IV) [12], which also holds potential as a tridentate telluroether ligand. Herein, we describe the reaction of IV with (CO)5MnBr and (CO)5ReCl, giving rise to the formation of three octahedral transition metal carbonyl complexes with this ligand.

2. Results and Discussion

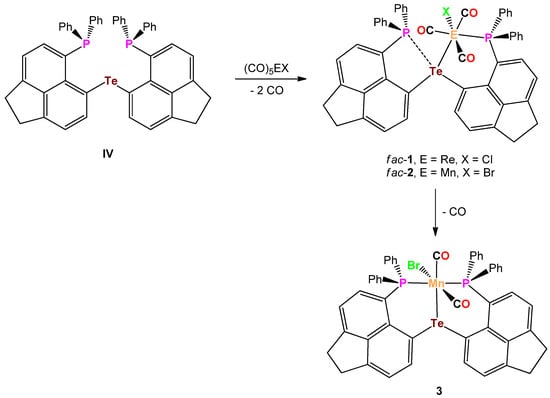

The reaction of bis(6-diphenylphosphinoacenaphth-5-yl)telluride (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2Te (IV) with (CO)5ReCl in THF at 65° for 7 days afforded an 1:1 isomeric mixture of the complex fac/mer-(6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeRe(Cl)(CO)3 (fac-1/mer-1), which slowly interconvert in solution. The progress of the reaction was followed by 31P NMR spectroscopy. Upon cooling to r.t. solely fac-1 precipitates from the reaction mixture and was isolated in 45% isolated yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the complexes fac-1, fac-2, and 3.

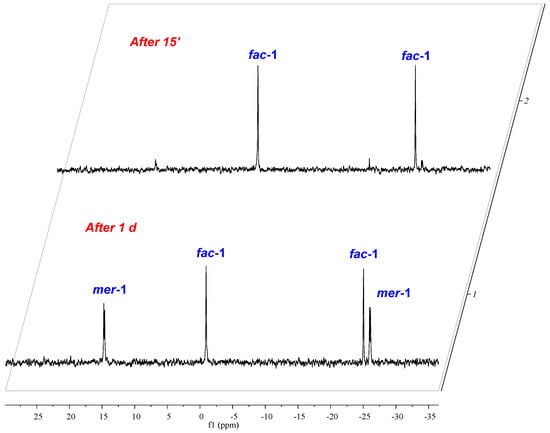

The analogous reaction of IV with (CO)5MnBr in THF at 65° occurred within 32 h and gave rise to the isomeric mixture of fac/mer-(6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeMe(Br)(CO)3 (fac-2/mer-2) and as was already observed for the Te-Re complex fac-1, fac-2 precipitates solely from the reaction mixture upon cooling to r.t. and was isolated in 47% yield (Scheme 2). In both complexes fac-1 and fac-2, the telluroether IV serves as bidentate ligand. In the solid-state, fac-1 and fac-2 are reasonably stable toward moist air and show no signs of decomposition even after prolonged times of storage. Unfortunately, both complexes show only poor solubility in the most common solvents used for NMR spectroscopy. In CDCl3 solution, both fac-1 and fac-2 are in equilibrium with their related meridional complexes mer-1 and mer-2, which can be inferred by 31P-NMR spectroscopy (Scheme 3). The 31P-NMR spectrum of a freshly prepared solution of fac-1 in CDCl3, shows almost exclusively two chemical shifts at δ = −0.9 and −25.0 ppm of equal intensity, which are assigned to the P atom that coordinates to the Re atom and the P atom that engages in interaction with the Te atom (the assignment is based upon the comparison with fac-[Re(Cl)(CO)3(PPh2C10H6PPh2)] [13], ([(Ph2P(Me2pz)2)Re(CO)3Br] and [(Ph2P(Me2pz))Re(CO)4Br (pz = pyrazole) [14]). However, the formation of mer-1 can already be detected even from the freshly prepared solution of fac-1, showing chemical shifts at δ = 14.7 and −26.4 ppm, which increase in intensity over time (Figure 1). It should be noted that the chemical shifts of fac-1 consist of singlets, whereas the doublets were observed for mer-1 with a coupling constant of J(31P-31P) = 11.6 Hz. In contrast, the Te–Mn complex 2 shows significantly faster formation of mer-2 (δ (31P) = 50.0 and −28.0 ppm) from a freshly prepared solution of fac-1 (δ (31P) = 36.2 and −25.6 ppm, Figure S2d).

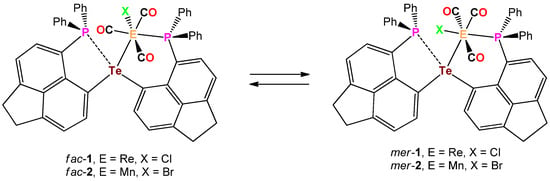

Scheme 3.

Dynamic equilibrium between fac-1 and mer-1 as well as fac-2 and mer-2.

Figure 1.

Equilibration between fac-1 and mer-1 in the CDCl3 solution.

When the reaction of IV with (CO)5MnBr was repeated with a longer reaction time of 7 days, a different product, namely (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeMn(Br)(CO)2 (3) formed, which was obtained in 40% isolated yield (Scheme 2). The formation of 3 can be rationalized by the liberation of CO from fac-2 and/or mer-2. In 3, the telluroether serves as tridentate ligand. Notably, a similar reactivity of fac-1 was not observed. The solubility of 3 in the most common solvents is slightly higher than those of fac-1 and fac-2, which allowed the acquisition of full set of NMR data. The 31P-NMR spectrum (CDCl3) of 3 shows a broad signal at δ = 59.7 ppm (ω1/2 = 110 Hz), whereas the 125Te-NMR spectrum exhibits a singlet at δ = 753.1 pm that is slightly high-field shifted in comparison to IV (δ = 704.4 ppm) [12].

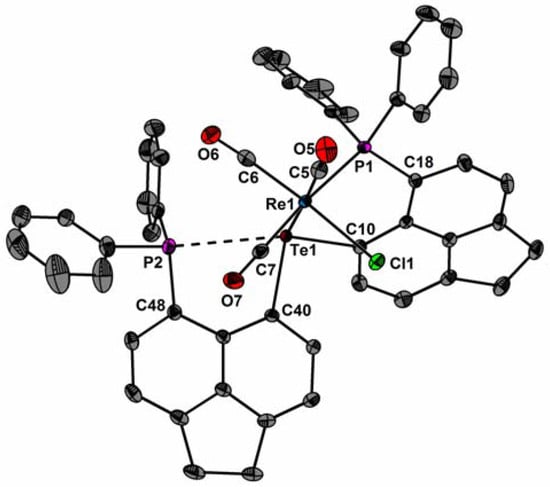

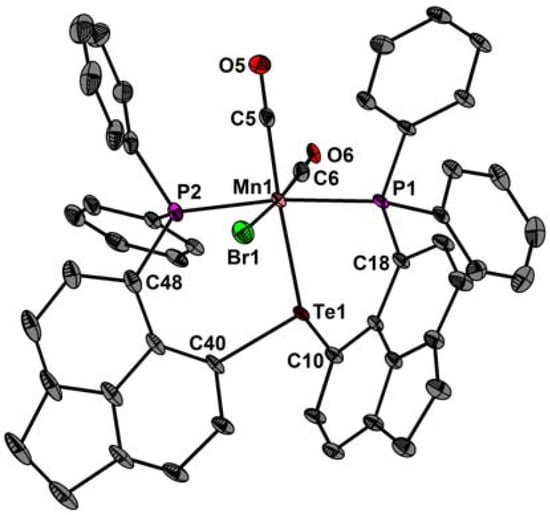

The molecular structures of fac-1, fac-2, and 3 are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4. Selected bond parameters are collected in Table 1. The spatial arrangement of the Re and Mn atoms is octahedral. In fac-1 and fac-2, only one P atom coordinates to the Re and Mn atoms, whereas the other P atoms engage in a through-space interactions with the Te atoms. Consistent with -the covalent radii of Mn and Re, the Mn–Te bond length of fac-2 (2.599(1) Å) and 3 (2.546(1) Å) are smaller than the Re–Te bond length of fac-1 (2.733(1) Å). The Mn–Te distances are in between values reported for [Mn(CO)4TePh]2 (mean 2.674(2) Å) [15,16,17] and [Cp′(CO)2Mn]2TeMes+ (2.44 Å) [18].

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of fac-1 showing 50% probability ellipsoids and the crystallographic numbering scheme.

Figure 3.

Molecular structure of fac-2 showing 50% probability ellipsoids and the crystallographic numbering scheme.

Figure 4.

Molecular structure of 3 showing 50% probability ellipsoids and the crystallographic numbering scheme.

Table 1.

Experimental interatomic distances [Å] and angles [°] of fac-1, fac-2, and 3.

Likewise, the Mn–P bond length of fac-2 (2.343(1) Å) and 3 (2.341(1) Å) is smaller than the Re–P bond length of 1 (2.466(1) Å). The average Mn–P distances are comparable with those of [Mn(Cl)(CO)3(κ1-PPh2C10H6PPh2)] (2.328(1) Å) [13] and iPrPNHPMn(CO)2Br (2.263 (1) Å) [19]. The Re(1)–C(5)/C(6) bond distances of fac-1 (2 × 1.930(2) Å) and the Mn(1)–C(5)/C(6) bond distances of fac-2 (1.817(6), 1.819(5) Å) are very similar to those of [ReCl(CO)3(PPh2C10H6PPh2)] (mean 1.952(16) Å)[13] and fac-[MnCl(CO)3(PPh2C10H6PPh2)] (mean 1.815(2) Å) [20]. Due to the trans-effect of the P atom, the Re(1)–C(7) bond distance of fac-1 (1.951(2) Å) and the Mn(1)–C(7) distance of fac-2 (1.915(7) Å) are slightly longer. The Mn(1)–C(5) and Mn(1)–C(6) bond lengths of 3 (1.800(4), 1.811(5) Å) are in average very similar than that of fac-[Mn(CO)3(dppbz)Br] (mean 1.807(4) Å; dppbz = 1,2-(diphenylphosphino)benzene) [21]. In the carbonyl region of the IR spectrum of fac-1 three strong absorption bands at = 2018, 1928, and 1882 cm−1 are visible, respectively, consistent with a facial arrangement of three carbonyl groups [12,22]. The IR spectrum of 3 reveals asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations at = 1936 and 1852 cm−1, which compare well with those of (iPrPONOP)Mn(CO)2Br (1866, 1946 cm−1) and iPrPNHPMn(CO)2Br (1824, 1916 cm−1) [19].

3. Conclusions

The present study demonstrates the ability of bis(6-diphenylphosphinoacenaphthyl-5-)telluride (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2Te (IV) [12] to act as a bidentate and tridentate ligand toward transition metals carbonyls. The reaction of IV with (CO)5ReCl and (CO)5MnBr provided three complexes, namely fac-(6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeM(X)(CO)3 (fac-1: M = Re, X = Cl; fac-2: M = Mn, X = Br) and (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeMn(Br)(CO)2 (3). In solution, the facial complexes, fac-1 and fac-2, are engaged in a reversible equilibrium with their meridional complexes, mer-(6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeM(X)(CO)3 (mer-1: M = Re, X = Cl; mer-2: M = Mn, X = Br).

4. Experimental Section

General. Reagents were obtained commercially (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) and were used as received. Dry solvents were collected from an SPS800 mBraun solvent system. Bis(6-diphenylacenaphth-5-yl)telluride, (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2Te (IV) was prepared according to literature procedures [12]. 1H-, 13C-, 31P-, and 125Te-NMR spectra were recorded at room temperature using a Bruker Avance-360 and a Bruker Avance-200 spectrometer and are referenced to tetramethylsilane (1H, 13C), phosphoric acid (85% in water) (31P), and dimethyltelluride (125Te). Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm), and coupling constants (J) are given in Hertz (Hz). The FTIR spectra were recorded on Thermo Scientific NicoletTM iS10. The ESI-MS spectra were obtained with a Bruker Esquire-LC MS. Dichloromethane/acetonitrile solutions (c = 1 × 10−6 mol L−1) were injected directly into the spectrometer at a flow rate of 3 µL min−1. Nitrogen was used both as a drying gas and for nebulization with flow rates of approximately 5 L min−1 and a pressure of 5 psi. Pressure in the mass analyzer region was usually about 1 × 10−5 mbar. Spectra were collected for 1 min and averaged. The nozzle-skimmer voltage was adjusted individually for each measurement.

Synthesis of (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeRe(CO)3Cl (fac-1): Re(CO)5Cl (9.20 mg, 25.4 µmol) was added to a solution of (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2Te (20.0 mg, 24.9 μmol) in THF (5 mL). The mixture was continually stirred at 65 °C for 7 d. The product precipitated upon cooling to room temperature as colorless microcrystals. (12.5 mg, 11.3 µmol, 45%; Mp. 197 °C (dec.)). Due to the low-solubility and the equilibrium of fac-1 and mer-1 in solution, reliable 13C- and 125Te-NMR spectra could not be obtained.

fac-1: 1H-NMR (200.1 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 7.99 (d, 3J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (m, 18H), 7.18 (dd, J = 7.9, 3.4 Hz, 4H), 6.71 (d, 3J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (d, 3J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 3.50 (s, 4H), 3.45–3.15 (m, 4H) ppm. 31P-NMR (81.0 MHz, CDCl3) δ = −0.9 (s), −25.0 (s) ppm. ESI-MS (CH2Cl2/CH3CN 1:10, positive mode): m/z = 1073.4 (C51H38O3P2ReTe) for [(6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2Te-Re(CO)3]+. FTIR: (CO) = 2018, 1928, 1882 cm−1. mer-1: 31P-NMR (81.0 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 14.7 (d, J(31P-31P) = 11.6 Hz), −26.4 (d, J(31P-31P) = 11.6 Hz) ppm.

Synthesis of (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeMn(CO)3Br (fac-2): Mn(CO)5Br (17.5 mg, 64.4 μmol) was added to a solution of (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2Te (50 mg, 62.3 μmol) in THF (10 mL). The mixture was continually stirred at 65 °C for 32 h. The product precipitated upon cooling to room temperature as orange microcrystals (30 mg, 29.4 μmol, 47%; Mp. 185 °C (dec.)). Due to the low-solubility, the equilibrium between fac-2 and mer-2 in solution and the concomitant formation of 3 reliable 13C- and 125Te-NMR spectra could not be obtained.

fac-2: 31P-NMR (81.0 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 50.4 (s, br), 39.9 (s, br), −27.4 (d, J(31P-31P) = 7.2 Hz) ppm. mer-2: 1H-NMR (200.1 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 7.95 (d, 3J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.80–6.85 (m, 26H), 3.41 (m, 8H) ppm. 31P-NMR (81.0 MHz, CDCl3) δ = 50.0 (s, br), −27.9 (d, J(31P-31P) = 7.2 Hz) ppm. ESI-MS (CH2Cl2/CH3CN 1:10, positive mode): m/z = 943.1 (C51H38O3P2MnTe) for [(6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2Te–Mn(CO)3]+. FTIR: (CO) = 2011, 1939, 1895 cm−1.

Synthesis of (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2TeMn(CO)2Br (3). Mn(CO)5Br (7.00 mg, 25.5 μmol) was added to a solution of (6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2Te (20.0 mg, 24.9 μmol) in THF (5 mL). The mixture was continually stirred at 65 °C for 7 d. The product precipitated upon cooling to room temperature as yellow microcrystals (10.0 mg, 10.0 μmol, 40%; Mp. 150 °C (dec.)).

1H-NMR (360.3 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ = 8.03 (s, 4H, Ho), 7.60 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H, H4), 7.52 (s, 6H, Hm+p), 7.35–7.19 (m, 8H, Hm’+p’+ H8), 7.19–7.05 (m, 6H, Ho’+ H4), 7.00 (m, 2H, H7), 3.50–3.34 (m, 8H, H1+2). 13C-NMR (90.6 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ = 150.8 (s, Cc), 150.2 (s, Cd), 139.9 (t, J = 4.0 Hz, Cb), 139.0 (s, C4), 136.8 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, Ca), 136.2 (s, C7), 135.7 (t, J = 18.1 Hz, Ci), 135.7 (d, J = 18.0 Hz, Ci’), 134.5 (t, J = 4.9 Hz, Co), 133.1 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, Co’), 129.8 (s, Cm), 129.0 (s, Cm’), 127.8 (t, J = 4.4 Hz, Cp), 127.5 (t, J = 4.2 Hz, Cp’), 127.0 (d, J = 17.5 Hz, C6), 119.5 (t, J = 3.9 Hz, C3), 119.4 (s, C8), 104.6 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, C5), 29.8 (s, C1), 29.7 (s, C2). 31P-NMR (81.0 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ = 59.7 (s, br). 125Te-NMR (113.7 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ = 753.1 (s). ESI-MS (CH2Cl2/CH3CN 1:10, positive mode): m/z = 859.4 (C50H36MnO2P2Te) for [[(6-Ph2P-Ace-5-)2Te–Mn(CO)2]–2CO]+. FTIR: (CO) = 1936 (s), 1852 (s) cm−1.

X-ray crystallography. Single crystals of fac-1, fac-2, and 3 were grown by slow evaporation of CH2Cl2 solutions that contained small amounts of n-hexane. Intensity data of fac-1, fac-2·CH2Cl2, and 3·2 CH2Cl2 were collected at 100 K on a Bruker Venture D8 diffractometer with graphite-monochromated Mo-Kα (0.7107 Å) radiation. All structures were solved by direct methods and refined based on F2 by use of the SHELX program package as implemented in WinGX [23]. Strongly disordered solvent molecules were accounted using the SQUEEZE routine for 1 and 2 [24]. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined using anisotropic displacement parameters. Hydrogen atoms attached to carbon atoms were included in geometrically calculated positions using a riding model. Crystal and refinement data are collected in Table 2.

Table 2.

Crystal data and structure refinement of fac-1, fac-2, and 3.

Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 were created using DIAMOND [25]. Crystallographic data (excluding structure factors) for the structural analyses have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. Copies of this information may be obtained free of charge from The Director, CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK (Fax: +44-1223-336033; e-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online.

Author Contributions

T.G.D. carried out the experimental work, the spectroscopic characterization and participated in writing the manuscript. As Co-Investor, E.H. was involved in the interpretation of the results and also participated in writing the manuscript. As Crystallographer, E.L. carried out the X-ray structure analyses. As Principal Investigator, J.B. was responsible for writing the publication.

Acknowledgments

The Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) is gratefully acknowledged for financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Murray, S.G.; Hartley, F.R. Coordination chemistry of thioethers, selenoethers, and telluroethers in transition-metal complexes. Chem. Rev. 1981, 81, 365–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gysling, H.J. The ligand chemistry of tellurium. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1982, 42, 133–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Srivastava, V. The Chemistry of Multidentate Organotellurium Ligands. J. Coord. Chem. 1992, 27, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, E.G.; Levason, W. Recent developments in the coordination chemistry of selenoether and telluroether ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1993, 122, 109–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Sharma, S. Recent developments in the ligand chemistry of tellurium. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 209, 49–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levason, W.; Orchard, S.D.; Reid, G. Recent developments in the chemistry of selenoethers and telluroethers. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 225, 159–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torubaev, Y.; Pasynskii, A.; Mathur, P. Organotellurium halides: New ligands for transition metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.K.; Chauhan, R.S. New vistas in the chemistry of platinum group metals with tellurium ligands. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 306, 270–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gysling, H.J.; Luss, H.R. Synthesis and properties of the hybrid tellurium-phosphorus ligand phenyl o-(diphenylphosphino)phenyl telluride. X-ray structure of [Pt[PhTe(o-(PPh2C6H4)]2][Pt(SCN)4]·2DMF. Organometallics 1984, 3, 596–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Singh, H.B.; Butcher, R.J. Syntheses and Characterization of Hybrid Bi- and Multidentate Tellurium Ligands Derived from N,N-Dimethylbenzylamine: Coordination Behavior of Bis[2-((dimethylamino)methyl)phenyl] Telluride with Chromium Pentacarbonyl. Organometallics 1995, 14, 4755–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.P.; Gabbaï, F.P. Two-Electron Redox Chemistry at the Dinuclear Core of a TePt Platform: Chlorine Photoreductive Elimination and Isolation of a TeVPtI Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12230–12238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, T.G.; Hupf, E.; Nordheider, A.; Lork, E.; Slawin, A.M.Z.; Makarov, S.G.; Ketkov, S.Y.; Mebs, S.; Woollins, J.D.; Beckmann, J. Intramolecularly Group 15 Stabilized Aryltellurenyl Halides and Triflates. Organometallics 2015, 34, 5341–5360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S.E.; Ahmed, F.; Ghosh, S.; Hassan, M.R.; Islam, M.S.; Sharmin, A.; Tocher, D.A.; Haworth, D.T.; Lindeman, S.V.; Siddiquee, T.A.; et al. Reactions of rhenium and manganese carbonyl complexes with 1,8-bis(diphenylphosphino)naphthalene: Ligand chelation, C–H and C–P bond-cleavage reactions. J. Organomet. Chem. 2008, 693, 2657–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyano, J.; Peterso, L.K. [LM(CO)3,4X] complexes of manganese(I) and rhenium(I) with phosphino- and thiophosphinatopyrazole ligands. Can. J. Chem. 1976, 54, 2697–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieber, W.; Kruck, T. Tellurorganyl-haltige Metallcarbonyle. Chem. Ber. 1962, 95, 2027–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, W.F.; Chiou, S.J.; Lee, W.Z.; Gene-Hsiang, P.; Peng, S.M. Syntheses and Characterization of Manganese-Tellurolate Complexes by Using Chelating Metalloligand cis-[Mn(Co)4(TePh)2]− and Potential Electrophilic TeMe+ Reagent. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 1996, 43, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadekov, I.D.; Uraev, A.I.; Garnovskii, A.D. Synthesis, reactions and structures of complexes of metal carbonyls and cyclopentadienyl carbonyls with organotellurium ligands. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1999, 68, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P.; Huttner, G.; Zsolnai, L. Trigonal-planar koordiniertes Selen bzw. Tellur in [Cp′(CO)2Mn]2EMes+ (E = Se, Te): Verbindungen vom “Iniden”-Typ. J. Organometal. Chem. 1992, 440, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondreau, A.M.; Boncella, J.M. The synthesis of PNP-supported low-spin nitro manganese(I) carbonyl complexes. Polyhedron 2016, 116, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Femia, F.J.; Babich, J.W.; Zubieta, J. Synthesis, crystal structures and magnetic properties of transition metal–azide complexes coordinated with pyridyl nitronyl nitroxides. Inorg. Chim Acta 2001, 315, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horikawa, H.; Horn, E.; Urushiyama, A.; Miyamoto, K. Crystal structure of tricarbonylbis [1,2-(diphenylphosphino)benzene]-manganese(I) bromide, Mn(CO)3(C30H24P2)Br. Z. Kristallogr. New Cryst. Struct. 2010, 225, 687–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.A.; Keene, F.R.; Horn, E.; Tiekink, E.R.T. Ambidentate coordination of the tripyridyl ligands 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridyl, tris(2-pyridyl)-amine, tris(2-pyridyl)methane and tris(2-pyridyl)phosphine to carbonylrhenium centres: Structural and spectroscopic studies. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 1990, 4, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, L.J. WinGX suite for small-molecule single-crystal crystallography. J. Appl. Cryst. 1999, 32, 837–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spek, A. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J. Appl. Cryst. 2003, 36, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, K.; Putz, H. DIAMOND V3.1d; Crystal Impact GbR: Bonn, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Sample Availability: Samples of fac-1, fac-2, and 3 are available from the authors. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).