Photochemical Oxidative Cyclisation of Stilbenes and Stilbenoids—The Mallory-Reaction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

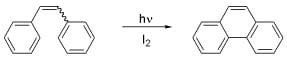

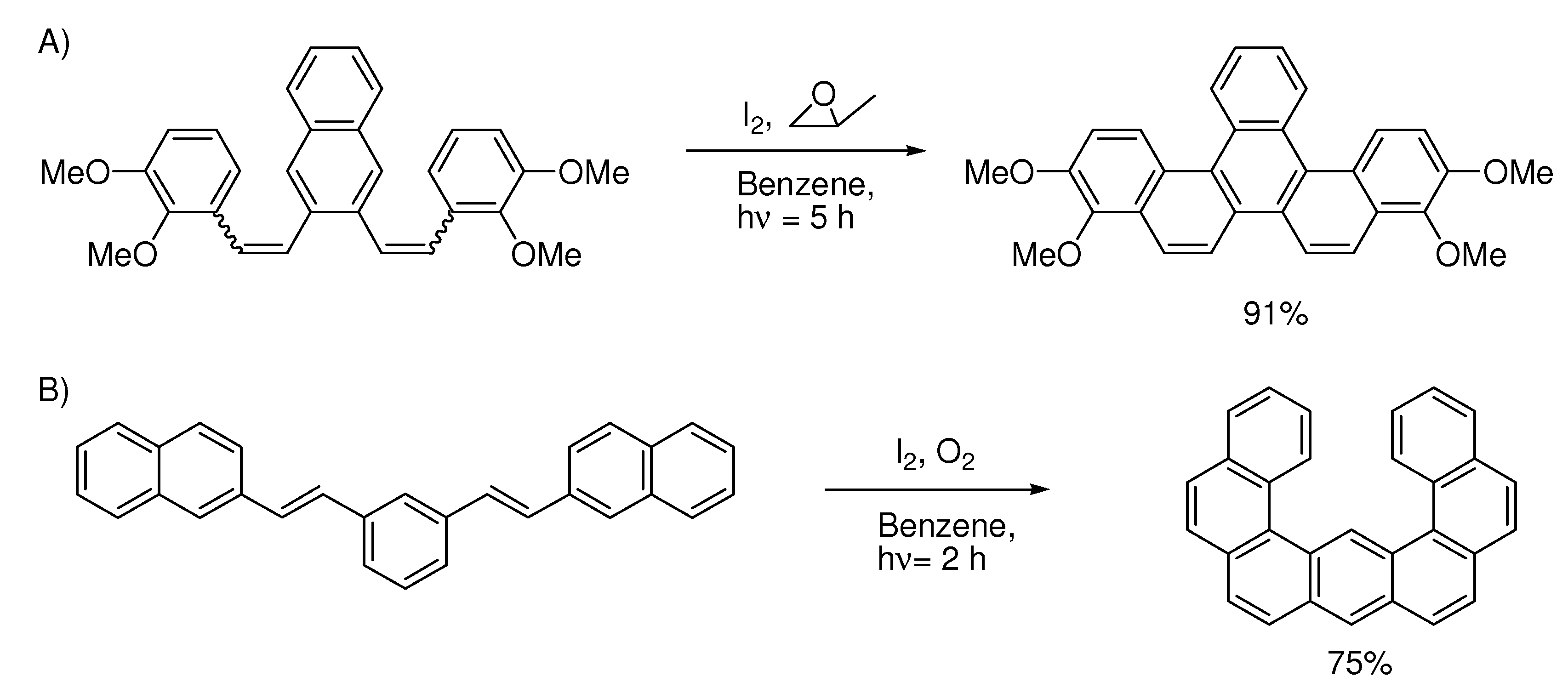

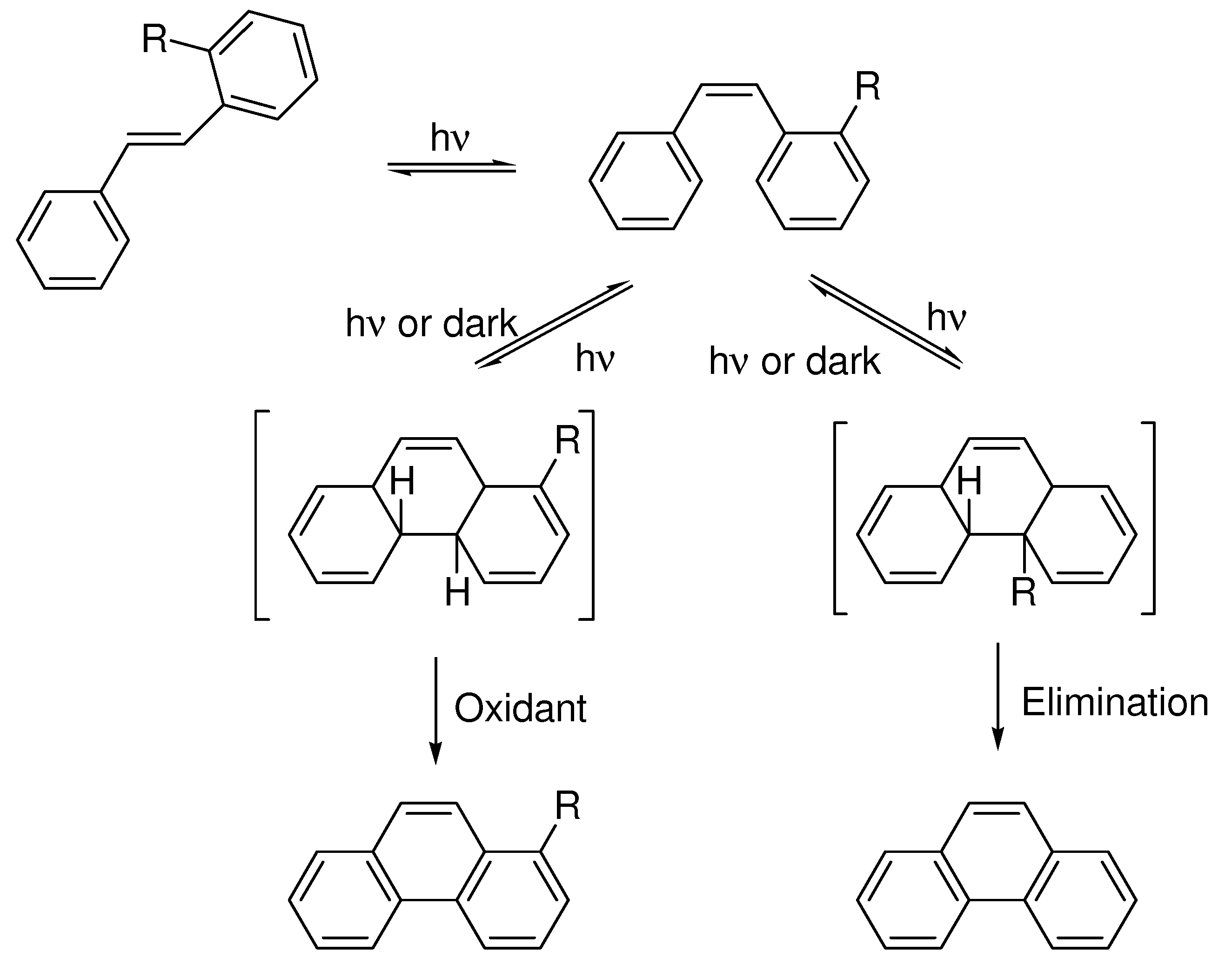

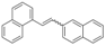

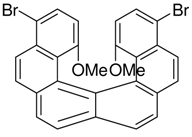

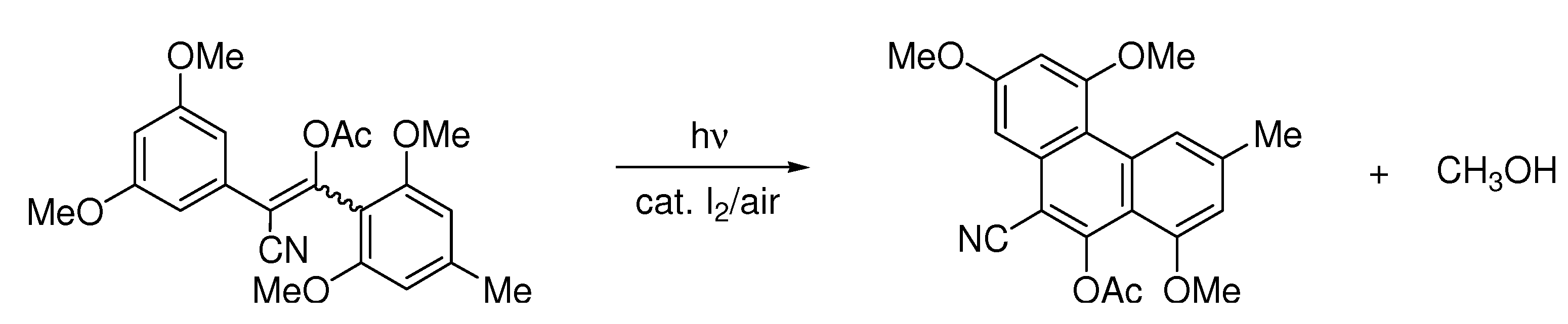

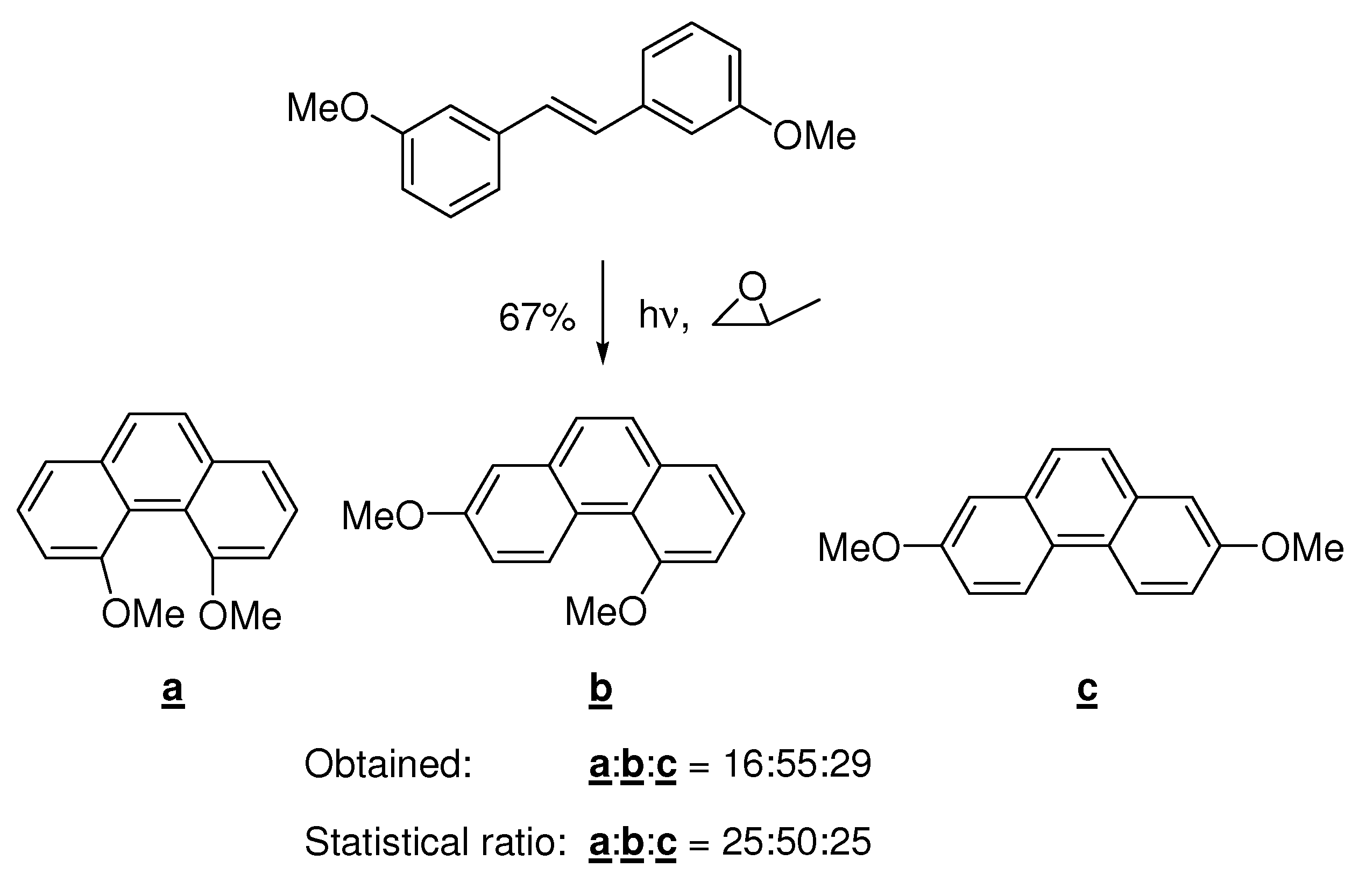

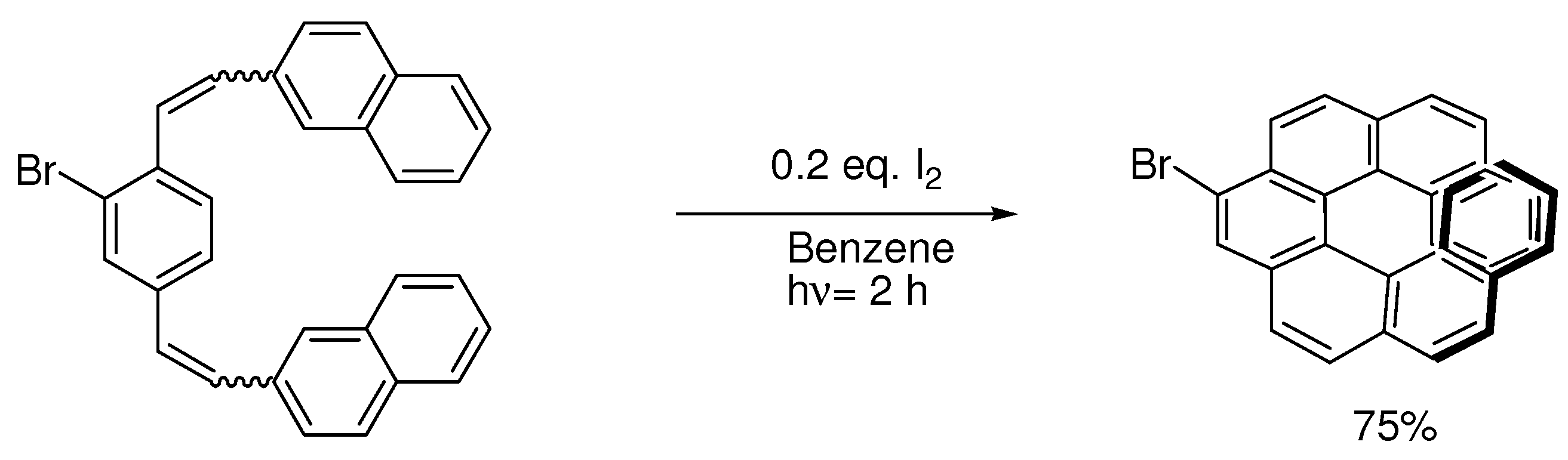

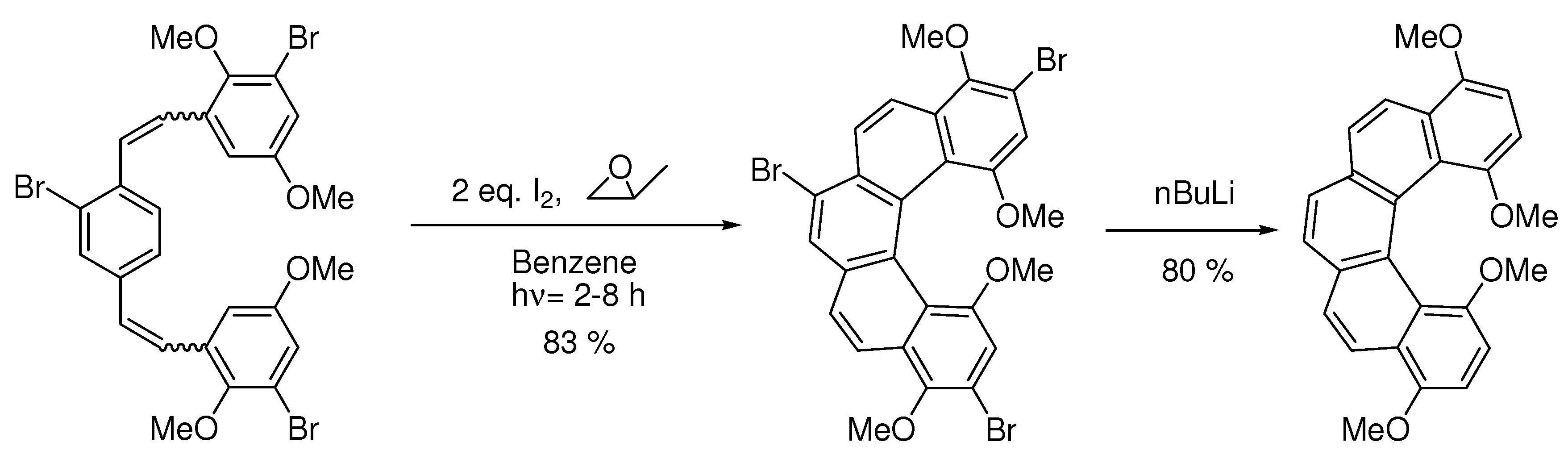

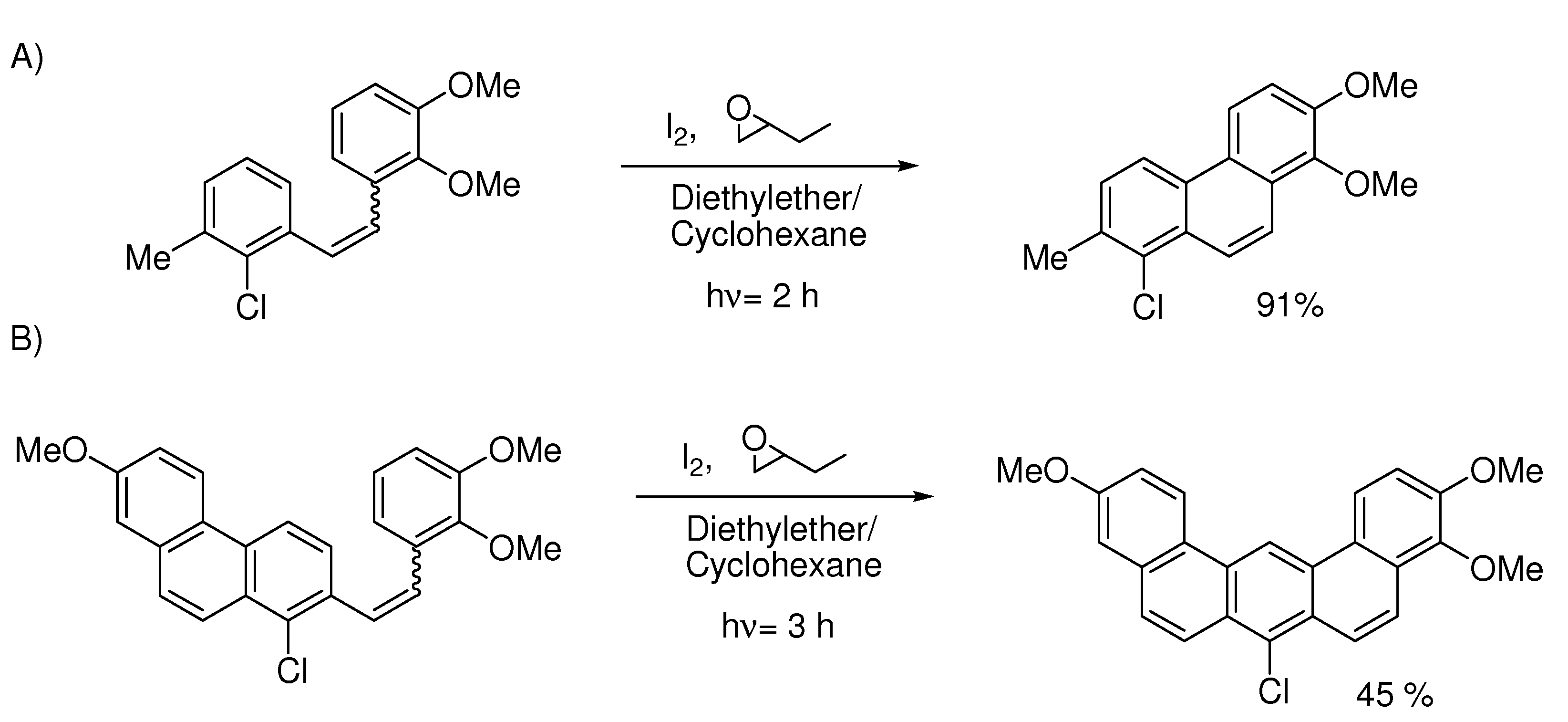

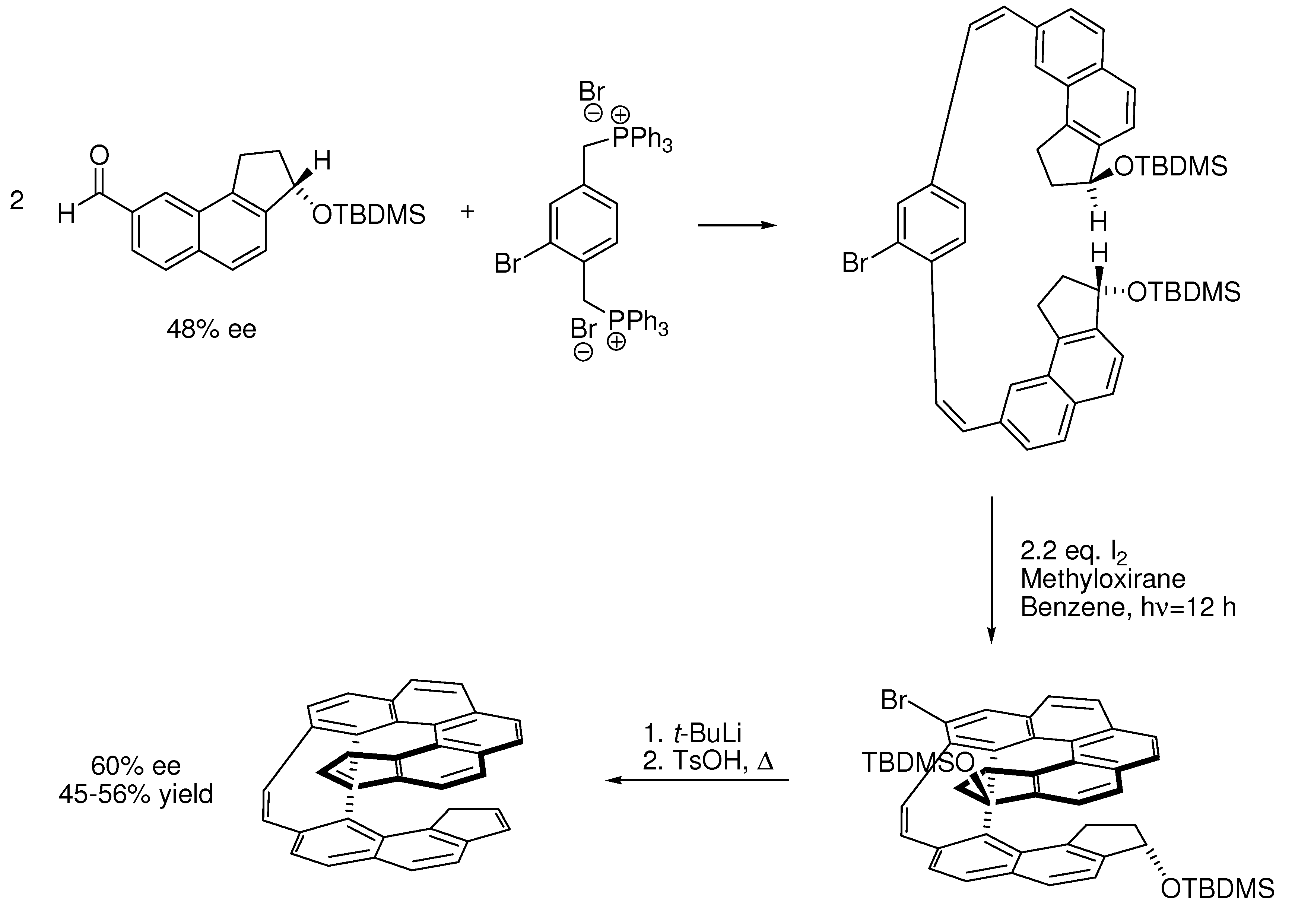

2. Oxidative Photocyclization

3. Katz’s Conditions

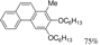

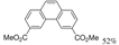

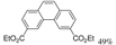

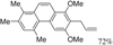

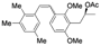

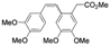

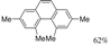

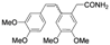

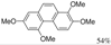

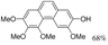

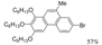

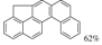

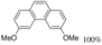

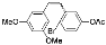

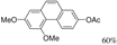

| Starting material | Product | Cat. I2 | Katz’s conditions |

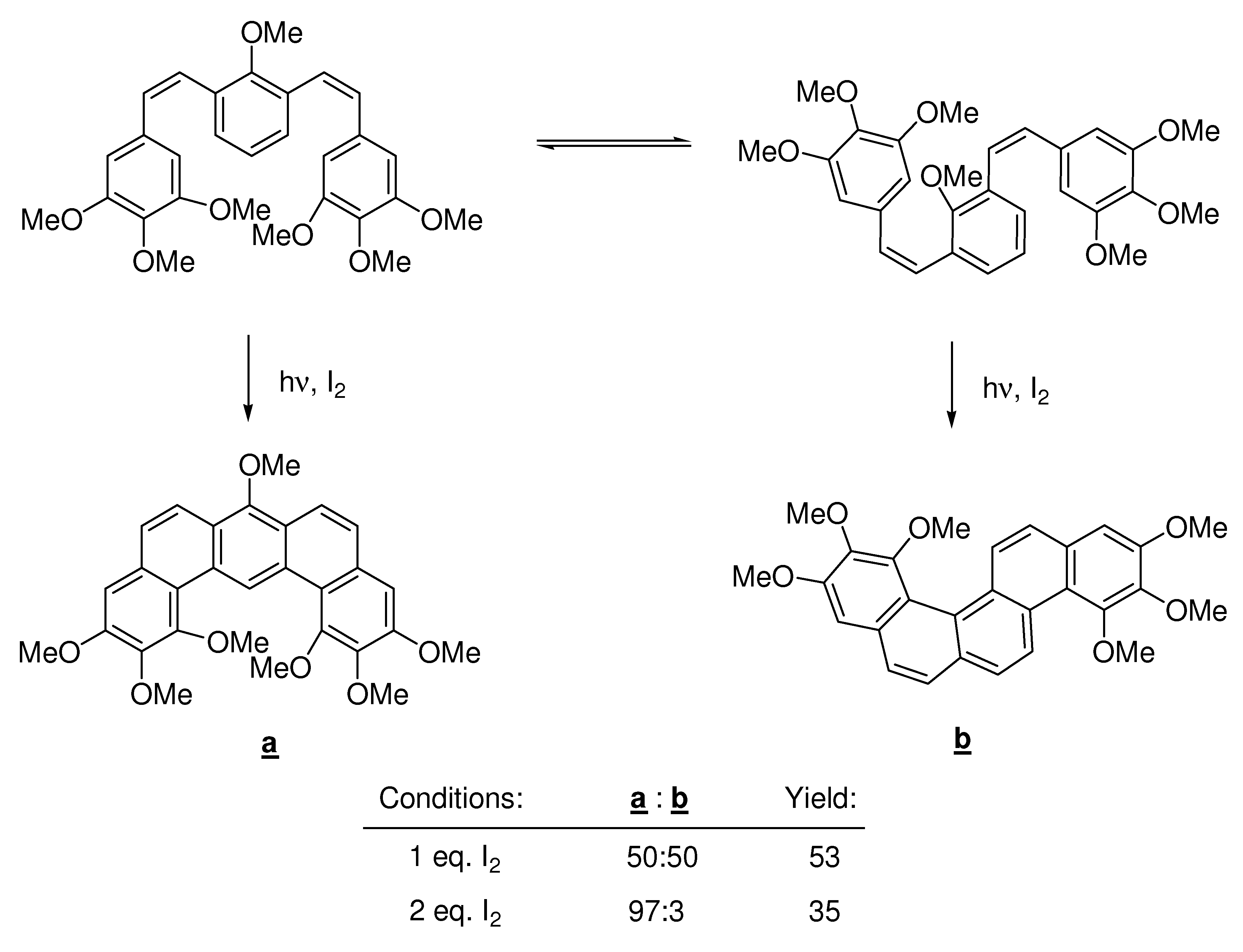

|---|---|---|---|

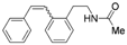

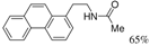

|  | 51% | 95% |

| (8 h) | (8 h) | ||

|  | 61% | 100% |

| (4 h) | (1 h) | ||

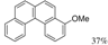

|  | <8% | 61% |

| (3.5 h) | (13 h) | ||

|  | 66% | 87% |

| (1.2 h) | (1.2 h) | ||

|  | <4% | 71% |

| (4.5 h) | (4.5 h) | ||

|  | 64% | 71% |

| Ref [17] | Ref [18] |

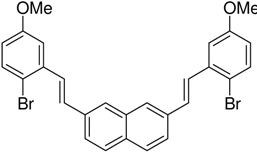

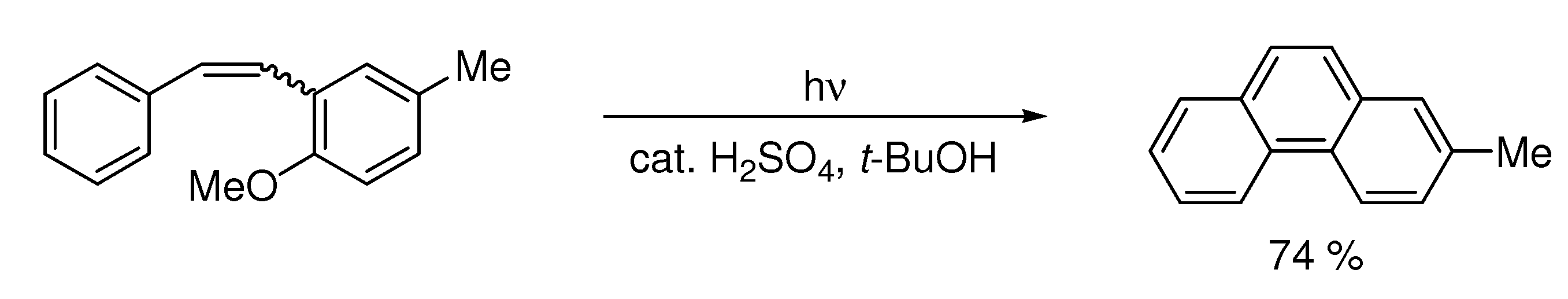

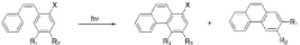

4. Elimination Photocyclizations

| ||||||

| X | R1 | R2 | Conditions | a | b | Product ratio |

| Cl | CH3 | H | Oxidative | 95 | 0 | >20 |

| Basic | 8 | 31 | 4.0 | |||

| Br | CH3 | H | Oxidative | 65 | 0 | >20 |

| Basic | 16 | 20 | 1.3 | |||

| Br | OCH3 | H | Oxidative | 71 | 7 | 10 |

| Basic | 10 | 41 | 4.1 | |||

| Br | OCH2O | Oxidative | 63 | 12 | 5.3 | |

| Basic | 0 | 57 | >20 |

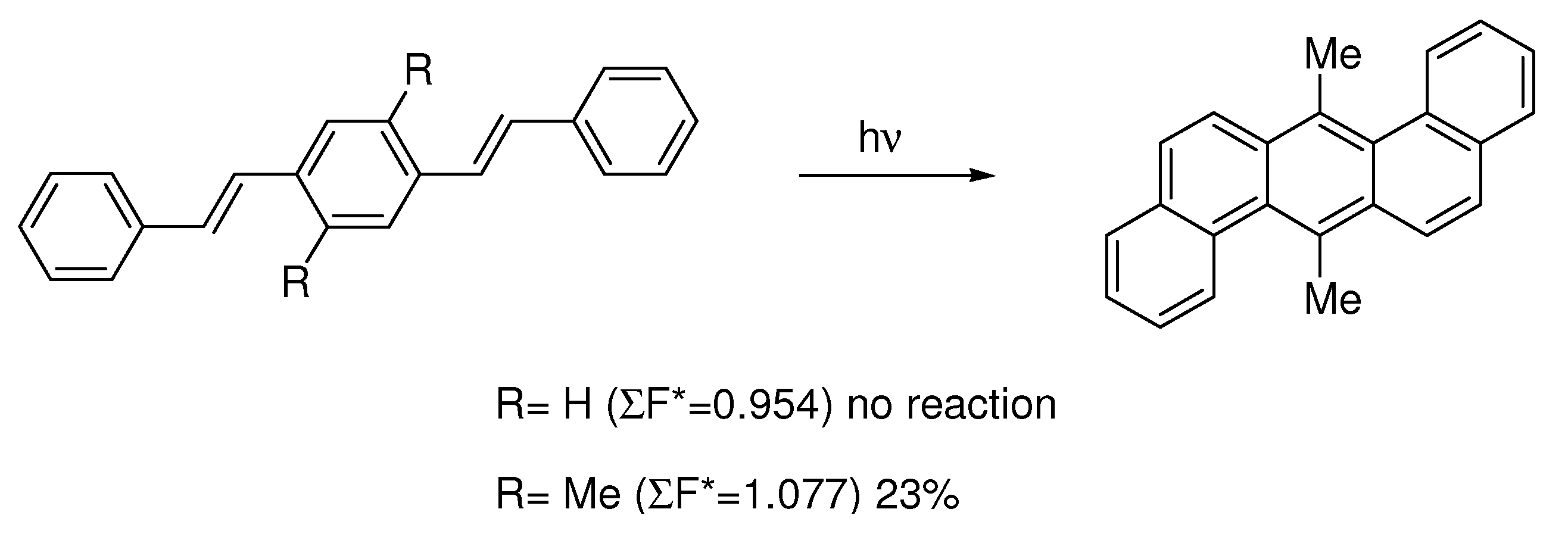

5. Reactivity Parameters

- (i)

- Photocyclizations do not occur when ∑F*rs<1.0.

- (ii)

- When two or more cyclizations are possible in a particular compound, only one product arises if ∆(∑F*rs) > 0.1; more products are formed if the differences are smaller.

- (iii)

- The second rule holds when only planar or non-planar products (penta- or higher helicenes) can arise. When planar as well as non-planar products can be formed, the planar aromatic in general is the main product, provided that for its formation ∑F*rs> 1.0

6. Controlling Product Formation with Blocking Groups

- Samples Availability: Not available.

References

- Smakula, A. The photochemical transformation of trans-stilbene. 1934, B25, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Buckles, R.E. Illumination of cis- and trans-stilbenes in dilute solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955, 77, 1040–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, F.B.; Wood, C.S.; Gordon, J.T. Photochemistry of Stilbenes. III. Some Aspects of the Mechanism of Photocyclization to Phenanthrenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 3094–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, F.B.; Wood, C.S. Photochemistry of Stilbenes IV. The Preparation of Substituted Phenyanthrenes. J. Org. Chem. 1964, 29, 3374–3377. [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, F.B.; Mallory, C.W. Photocyclization of stilbenes and related molecules. Org. React. 1984, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Laarhoven, W.H. Photochemical cyclizations and intramolecular cycloadditions of conjugated arylolefins. Part I: Photocyclization with dehydrogenation. Rec. Trav. Chim.-J. Roy. Neth. Chem. 1983, 102, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, S.; Hopf, H. Modern routes to extended aromatic compounds. In Carbon Rich Compounds I; Springer-Verlag Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 1998; Volume 196, pp. 45–89. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, H. The photochemistry of stilbenoid compounds and their role in materials technology. Angew.Chem. Int. Ed. Eng. 1992, 31, 1399–1420. [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga, Y.; Castle, R.N. Photocyclization of aryl- and heteroaryl-2-propenoic acid derivatives. Synthesis of polycyclic heterocycles. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1996, 33, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laarhoven, W.H. Photocyclizations and intramolecularphotocycloadditions of conjugated arylolefins and related compounds. Org. Photochem. 1989, 10, 163–308. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, T.; Inoue, Y. C=C photoinducedisomerization reactions. Mol. Supramol. Photochem. 2005, 12, 417–452. [Google Scholar]

- Zertani, R.; Meier, H. Photochemistry of 1,3-distyrylbenzene. A new route to syn-[2.2](1,3)cyclophanes. Chem. Ber. 1986, 119, 1704–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noller, K.; Kosteyn, F.; Meier, H. Photochemistry of electron-rich 1,3-distyrylbenzenes. Chem. Ber. 1988, 121, 1609–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, B.; Katz, T.J.; Poindexter, M.K. Improved methodology for photocyclization reactions. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 3769–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, A.; Katz, T.J. Directive effect of bromine on stilbene photocyclizations. An improved synthesis of [7]helicene. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986, 27, 2231–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, A.; Katz, T.J.; Yang, B. Synthesis of a helical Metallocene Oligomer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 2790–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Mah, H.; Chaturvedi, S.; Jeknic, T.M.; Baird, W.M.; Katz, A.K.; Carrell, H.L.; Glusker, J.P.; Okazaki, T.; Laali, K.K.; Zajc, B.; Lakshman, M.K. Synthetic, crystallographic, computational, and biological studies of 1,4-difluorobenzo c phenanthrene and its metabolites. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 7625–7633. [Google Scholar]

- Plater, M.J. Synthesis of benzo[ghi]fluoranthenes from 1-halobenzo[c]phenanthrenes by flash vacuum pyrolysis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 6147–6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigglesworth, T.J.; Sud, D.; Norsten, T.B.; Lekhi, V.S.; Branda, N.R. Chiral discrimination in photochromic helicenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 7272–7273. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, A.; Cote, B.; Ducharme, Y.; Frenette, R.; Friesen, R.; Gagnon, M.; Giroux, A.; Martins, E.; Yu, H.; Wu, T. Preparation of 2-(phenyl or heterocyclyl)-1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazoles as microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1) enzyme inhibitors. WO 2007/059610, 31 May 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, A.; Cote, B.; Ducharme, Y.; Frenette, R.; Friesen, R.; Gagnon, M.; Giroux, A.; Martins, E.; Yu, H.; Hamel, P. Preparation of phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazoles as inhibitors of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1). WO 2007/095753, 30 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, A.; Cote, B.; Ducharme, Y.; Frenette, R.; Friesen, R.; Gagnon, M.; Giroux, A.; Martins, E.; Yu, H.; Wu, T. Preparation of 1H-phenanthro[9,10-d]imidazoles as mPGES-1 inhibitors. WO 2006/063466, 22 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, K.B.; Joensen, M. Photochemical synthesis of chrysenols. Polycycl.Aromat. Compound. 2008, 28, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmann, H.; Muller, K.; Kolshorn, H.; Schollmeyer, D.; Meier, H. Triphenanthro-anellated 18 annulenes with alkoxy side-chains - A novel class of discotic liquid-crystals. Chem. Ber. 1994, 127, 1735–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastalerz, M.; Hueggenberg, W.; Dyker, G. Photochemistry of styrylcalix[4]arenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 3977–3987. [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto, H.; Kawano, T.; Ueji, N.; Sakamoto, N.; Araki, T.; Miyoshi, N.; Suzuki, I.; Shibuya, M. Synthesis of a water-soluble molecular tweezer and a recognition study in an aqueous media. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 551–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos, R.I., Jr.; Tung, J.S.; Rapoport, H. A high-yield modification of the Pschorrphenanthrene synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 1984, 49, 5243–5246. [Google Scholar]

- Finnie, A.A.; Hill, R.A. The synthesis of 1,5,7,10-tetraoxygenated 3-methylphenanthrenes. J. Chem. Res., Synop. 1987, 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, F.B.; Rudolph, M.J.; Oh, S.M. Photochemistry of stilbenes. 8. Eliminative photocyclization of o-methoxystilbenes. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 4619–4626. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, J.F.; Castedo, L.; Fernandez, D.; Neo, A.G.; Romero, V.; Tojo, G. Base-Induced Photocyclization of 1,2-Diaryl-1-tosylethenes. A Mechanistically Novel Approach to Phenanthrenes and Phenanthrenoids. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 4939–4941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, R.J.; Pruett, S.R. Photocyclization of o-halostilbenes. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 5457–5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyker, G.; Koerning, J.; Stirner, W. Synthesis and photocyclization of macrocyclicstilbene derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.J.; Harvey, R.G. Syntheses of fjord region bis-dihydrodiol and bis-anti-diolepoxide metabolites of benzo s picene. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 1168–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, F.B.; Mallory, C.W.; Sen Loeb, S.E. Photochemistry of stilbenes. 7. Formation of a dinaphthanthracene by a stilbene-like photocyclization. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 3773–3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.; Mühlstädt, M.; Dietz, F. Chemie Angeregter Zustände. I. Mitt die Richlung der Photocycliserung Naphthalinsubstituerter Äthylene. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967, 665–668. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, J.; Zimmerman, M. Photocyclization of substituted 1,4-distyrylbenzenes to dibenz[a,h]anthracenes. Tetrahedron 1972, 28, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Katz, T.J. Bromine auxiliaries in photosynthesis of [5]helicenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 6831–6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, F.; El Abed, R.; Guerfel, T.; Ben Hassine, B. Synthesis and X-Ray Analysis of a New [6]helicene. Synth.Commun. 2006, 36, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, D.; Krzeminski, J.; Amin, S. Convenient synthesis of 3-methoxybenz[a]anthracene-7,12-dione. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1994, 7, 722–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.G.; Dai, W.; Zhang, J.T.; Cortez, C. Synthesis of potentially carcinogenic higher oxidized metabolites of dibenz a,j anthracene and benzo c chrysene. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 8118–8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.G.; Zhang, F.J. New synthetic approaches to PAHs and their carcinogenic metabolites. Polycycl.Aromat. Compound. 2002, 22, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.J.; Cortez, C.; Harvey, R.G. New synthetic approaches to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their carcinogenic oxidized metabolites: Derivatives of benzo s picene, benzo rst pentaphene, and dibenzo b,def chrysene. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 3952–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-T.; Dai, W.; Harvey, R.G. Synthesis of Higher Oxidized Metabolites of Dibenz[a,j]anthracene Implicated in the Mechanism of Carcinogenesis. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 8125–8132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, W.J.C.; Laarhoven, W.H. The influence of the chiral environment in the photosynthesis of enantiomerically enriched hexahelicene. Rec. Trav. Chim.-J. Roy. Neth. Chem. 1995, 114, 470. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, M.S.M.; Carbery, D.R. Studies toward the Photochemical Synthesis of Functionalized [5]- and [6]Carbohelicenes. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 5320–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Tang, J.; Beetz, T.; Guo, X.; Tremblay, N.; Siegrist, T.; Zhu, Y.; Steigerwald, M.; Nuckolls, C. Transferring Self-Assembled, Nanoscale Cables into Electrical Devices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 10700–10701. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, B.; Amin, S. An improved synthesis of anti-benzo[c]phenanthrene-3,4-diol-1,2-epoxide via 4-methoxybenzo[c]phenanthrene. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 4478–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, F.B.; Butler, K.E.; Berube, A.; Luzik, E.D.; Mallory, C.W.; Brondyke, E.J.; Hiremath, R.; Ngo, P.; Carroll, P.J. Phenacenes: a family of graphite ribbons. Part 3: Iterative strategies for the synthesis of large phenacenes. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 3715–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, F.B.; Butler, K.E.; Evans, A.C.; Brondyke, E.J.; Mallory, C.W.; Yang, C.; Ellenstein, A. Phenacenes: A Family of Graphite Ribbons. 2. Syntheses of Some [7]Phenacenes and an [11]Phenacene by Stilbene-like Photocyclizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 2119–2124. [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, F.B.; Butler, K.E.; Evans, A.C.; Mallory, C.W. Phenacenes: a family of graphite ribbons. 1. Synthesis of some [7]Phenacene by stilbene-like photocyclizations. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 7173–7176. [Google Scholar]

- Puls, C.; Stolle, A.; de Meijere, A. Preparation and properties of new methano-bridged dibenzo[c,g]phenanthrenes. Chem. Ber. 1993, 126, 1635–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.I.; Shu, C.S.; Yeh, M.K.; Chen, F.C. A novel synthetic approach to biphenyls. Synthesis 1987, 795–797. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, S.R.; Kapadi, A.H. Synthesis of eulophioldimethyl ether. Indian J. Chem. Sect. B 1985, 24B, 204–205. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, H.; Kretzschmann, H.; Kolshorn, H. abc]-Annelated [18]annulenes. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 6847–6852. [Google Scholar]

- Langenegger, S.M.; Haner, R. The effect of a non-nucleosidicphenanthrene building block on DNA duplex stability. Helv.Chim. Acta 2002, 85, 3414–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, A.I.; Pitt, A.R.; Scobie, M.; Suckling, C.J.; Urwin, J.; Waigh, R.D.; Fishleigh, R.V.; Young, S.C.; Wylie, W.A. The synthesis of some head to head linked DNA minor groove binders. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 5225–5239. [Google Scholar]

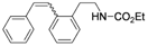

- Carme Pampin, M.; Estevez, J.C.; Estevez, R.J.; Maestro, M.; Castedo, L. Heck-mediated synthesis and photochemically induced cyclization of [2-(2-styrylphenyl)ethyl]carbamic acid ethyl esters and 2-styrylbenzoic acid methyl esters: Total synthesis of naphtho[2,1f]isoquinolines (2-azachrysenes). Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 7231–7243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampin, C.; Estevez, J.C.; Castedo, L.; Estevez, R.J. Palladium-mediated total synthesis of 2-styrylbenzoic acids: a general route to 2-azachrysenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 4551–4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliakoudas, D.; Eugster, C.H.; Ruedi, P. Synthesis of plectranthones, diterpenoid phenanthrene-1,4-diones. Helv.Chim. Acta 1990, 73, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, J.C.; Villaverde, M.C.; Estevez, R.J.; Seijas, J.A.; Castedo, L. New total synthesis of phenanthrene alkaloids. Can. J. Chem. 1990, 68, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampin, M.C.; Estevez, J.C.; Estevez, R.J.; Suau, R.; Castedo, L. First total syntheses of the 1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphtho[2,1-f]isoquinolinesannoretine and litebamine. Tetrahedron 2003, 59, 8057–8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, E.; Estevez, J.C.; Estevez, R.J.; Castedo, L. Photochemically induced cyclization of N-[2-(o-styryl)phenylethyl]acetamides and 5-styryl-1-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolines: New total syntheses of 1-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphtho[2,1-f]isoquinolines. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 1981–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.R.; Schiller, C.D. Hydroxy substituted 10-ethyl-9-phenylphenanthrenes. Compounds for the investigation of the influence of E,Z-isomerization on the biological properties of mammary tumor-inhibiting 1,1,2-triphenylbutenes. Arch. Pharm. 1987, 320, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, C.J.; Rees, C.W.; Young, R.G. Synthesis and properties of 4H-imidazoles. Part 2. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1991, 335–339. [Google Scholar]

- Hopf, H.; Hucker, J.; Ernst, L. Paracyclophanes. Part 58. On the use of the stilbene-phenanthrene photocyclization in 2.2 paracyclophane chemistry. Polish J. Chem. 2007, 81, 947–969. [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Takeda, K.; Murahashi, K.; Horikawa, M.; Katagiri, K.; Masu, H.; Kato, T.; Azumaya, I.; Fujii, S.; Furuta, T.; Tanaka, K.; Kan, T. Synthesis and characteristic stereostructure of a biphenanthryl ether. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2008, 19, 1407–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Nishimura, J. Intramolecular [2+2]-photocycloaddition. 19. 1,2-Ethano-syn-[2.n](1,6)phenanthrenophanes; first isolated syn-phenanthrenophanes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 5563–5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, T.J.; Muller, T.J.J. The first synthesis and electronic properties of tetrakis[(hetero)phenanthrenyl]methanes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 2269–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, S.; Kurono, N.; Senboku, H.; Tokuda, M.; Orito, K. Synthesis of phenanthro[9,10-b]indolizidin-9-ones, phenanthro[9,10-b]quinolizidin-9-one, and related benzolactams by Pd(OAc)2-catalyzed direct aromatic carbonylation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Purushothaman, E.; Pillai, V.N.R. Photoreactions of 4,5-diarylimidazoles: Singlet oxygenation and cyclodehydrogenation. Indian J. Chem. Sect. B 1989, 28B, 290–293. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.-H.; Tsau, M.-H.; Weng, D.T.C.; Lee, G.H.; Peng, S.-M.; Luh, T.-Y.; Biedermann, P.U.; Agranat, I. Oxidative Photocyclization of Tethered Bifluorenylidenes and Related Compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 7380–7381. [Google Scholar]

- Sabitha, G.; Reddy, G.J.; Rao, A.V.S. Synthesis of 3-phenylbenzo[g][1]benzopyrano[4,3-e]indazol-8(3H)-ones and benzo[b]phenanthro[9,10-d]pyran-9-ones by photooxidation of 3-aryl-4-(1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)coumarins and 3,4-diarylcoumarins. Synth.Commun. 1988, 18, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, J.N.; Venkatakrishnan, P.; Sengupta, S.; Baidya, M. Facile synthesis, fluorescence, and photochromism of novel helical pyrones and chromenes. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 4891–4894. [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga, Y.; Castle, R.N.; Lee, M.L. Synthesis of aminochrysenes by the oxidative photocyclization of acetylaminostilbenes. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1993, 41, 1853–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, F.B.; Mallory, C.W.; Ricker, W.M. Nuclear spin-spin coupling via nonbonded interactions. 4. Fluorine-fluorine and hydrogen-fluorine coupling in substituted benzo[c]phenanthrenes. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utermoehlen, C.M.; Singh, M.; Lehr, R.E. Fjord region 3,4-diol 1,2-epoxides and other derivatives in the 1,2,3,4- and 5,6,7,8-benzo rings of the carcinogen benzo[g]chrysene. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 5574–5582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, A.; Glatt, H.R.; Oesch, F.; Garrigues, P. 2,9-Dimethylpicene: synthesis, mutagenic activity, and identification in natural samples. Polycycl.Aromat. Compound. 1990, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, E.K.; Behrend, S.J.; Meyerson, S.; Winzenburg, M.L.; Ortega, B.R.; Hall, H.K. Diaryl-substituted maleic anhydrides. J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 5165–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, N.J.; Ghani, F.A.; Hepworth, L.A.; Hadfield, J.A.; McGown, A.T.; Pritchard, R.G. The synthesis of (E)- and (Z)-combretastatins A-4 and a phenanthrene from Combretumcaffrum. Synthesis 1999, 1656–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Schnorpfeil, C.; Fetten, M.; Meier, H. Synthesis of tripyreno2,3,4-abc:2,3,4-ghi:2,3,4-mno][18]annulenes. J. Prakt. Chem. 2000, 342, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Yamazaki, T.; Nishimura, J. Synthesis and Fluorescence Spectra of Oxa[3.n]phenanthrenophanes. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 3259–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Fujii, T.; Nishimura, J. Synthesis and fluorescence emission behavior of anti-[2.3](3,10)phenanthrenophane: Overlap between phenanthrene rings required for excimer formation. Chem. Lett. 2001, 970–971. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, T.R.; Sestelo, J.P.; Tellitu, I. New molecular devices: In search of a molecular ratchet. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 3655–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plater, M.J. Fullerene tectonics .2. Synthesis and pyrolysis of halogenated benzo c phenanthrenes. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1997, 2903–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.J.; Harvey, R.G. Efficient synthesis of the carcinogenic anti-diolepoxide metabolite of 5-methylchrysene. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 2771–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, H.; Fetten, M.; Schnorpfeil, C. Synthesis of areno-condensedb [24]annulenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 779–786. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.T.; Harvey, R.G. Syntheses of oxidized metabolites implicated as active forms of the highly potent carcinogenic hydrocarbon dibenzo def,p chrysene. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.X.; Harvey, R.G. Synthesis of methylene-bridged polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 4155–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, A.; Hu, J.Y.; Yamato, T. Synthesis and structural properties of novel polycyclic aromatic compounds using photo-induced cyclisation of 2,7-di-tert-butyl-4-(phenylethenyl)pyrenes. J. Chem. Res.-S 2008, 457–460. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, R.G.; Zhang, J.T.; Luna, E.; Pataki, J. Synthesis of benzo s picene and its putative carcinogenic trans-3,4-dihydrodiol and fjord region anti-diolepoxide metabolites. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 6405–6408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

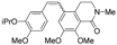

- Blanco, O.; Castedo, L.; Cid, M.; Seijas, J.A.; Villaverde, C. N-Methylsecoglaucine, a new phenanthrene alkaloid from fumariaceae. Heterocycles 1990, 31, 1077–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castedo, L.; Granja, J.A.; Rodriguez de Lera, A.; Villaverde, M.C. Structure and synthesis of goudotianine, a new 7-methyldehydroaporphine from Guatteriagoudotiana. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1988, 25, 1561–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soicke, H.; Al-Hassan, G.; Frenzel, U.; Goerler, K. Photochemical synthesis of bulbocapnin. Arch. Pharm. 1988, 321, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

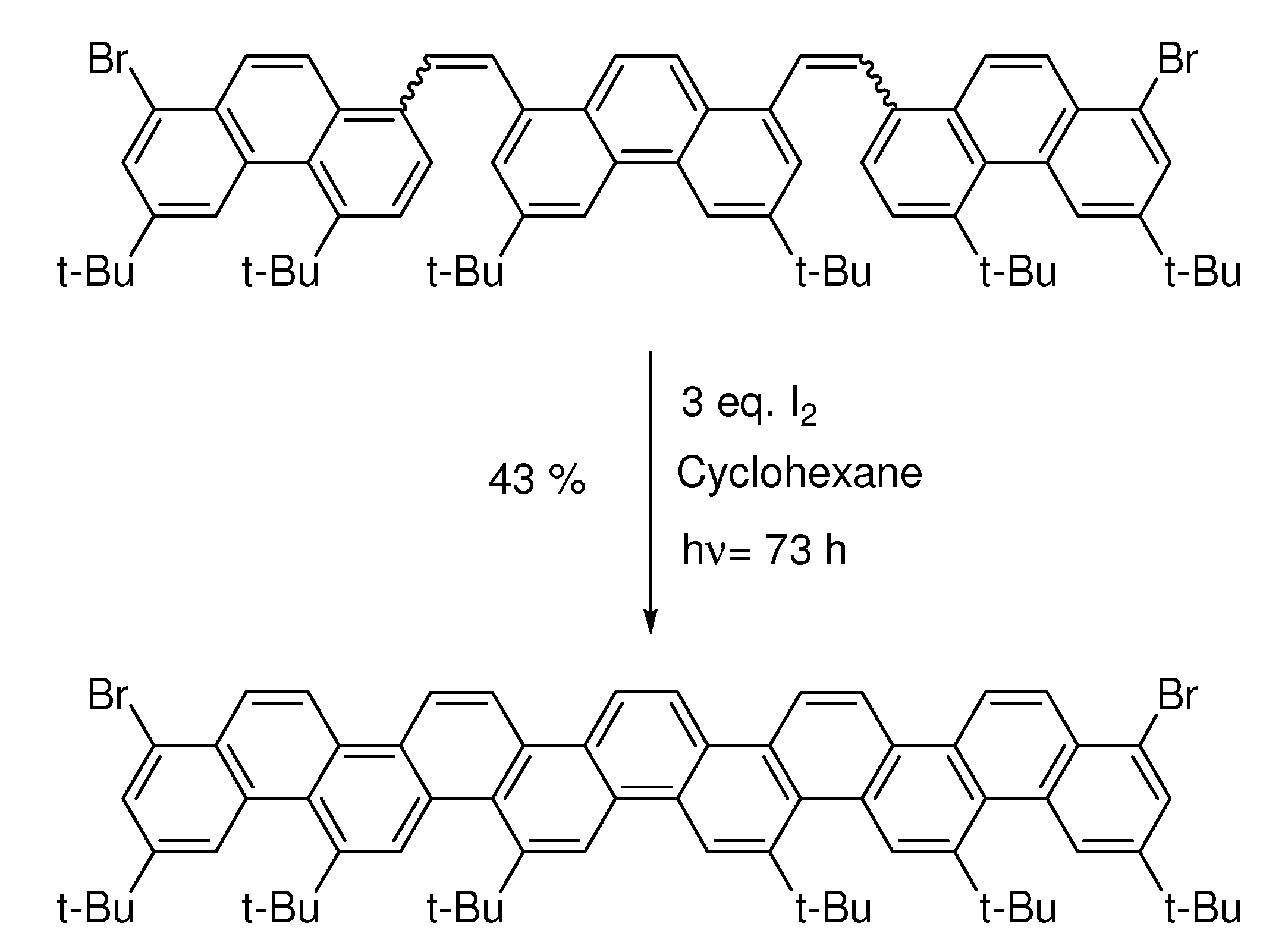

Appendix 1

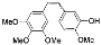

| Staring material | Conditions | Products | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 eq. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = ? |  | [51] | ||

| 0.5 eq. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = 24 h (42 mmol/L) |  | [52] | ||

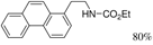

| Cat. I2, Ethanol, hν = 8 h |  | [53] | ||

| 0.67 eq. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = 47 h |  | [54] | ||

| 0.3 eq. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = ? |  | [51] | ||

| Cat. I2, Toluene, hν = 24 h |  | [55] | ||

| 0.5 eq. I2, Toluene, hν = 3 days |  | [56] | ||

| Cat. I2, Methanol, hν = 30 h |  | [57] | ||

| 1 eq. I2, Diethylether/ DCM, hν = ? |  | [58] | ||

| Cat. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = 7 h |  | [59] | ||

| Cat. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = 2 h |  | [59] | ||

| Cat. I2, Diethylether, hν = 3 h |  | [60] | ||

| Cat. I2, Diethylether, hν = 3 h |  | [60] | ||

| Cat. I2, Diethylether/ DCM, hν = 2 h |  | [57] | ||

| Cat. I2, Diethylether/ DCM, hν = 5 h |  | [61] | ||

| Cat. I2, Diethylether, hν = 2 h |  | [62] | ||

| Cat. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = 3 h |  | [63] | ||

| Cat. I2, DCM/ Cyclohexane, hν = 1 h |  | [64] | ||

| 0.25 eq. I2, Biacetyl, Toluene, hν = 40 min. |  | [65] | ||

| Cat. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = ? |  | [66] | ||

| Cat. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = ? |  | [67] | ||

| Cat. I2, Toluene, hν = 12 h |  | [68] | ||

The free acid did not react. The free acid did not react. | Cat. I2, Benzene, hν = 24 h |  | [69] | ||

| Cat. I2, Benzene, hν = 2 days |  | [69] | ||

| Cat. I2, Methanol, hν = 21 h |  | [70] | ||

| 2 eq. I2, Benzene, hν = 8 h |  | [71] | ||

| Cat. I2, Benzene, hν = 24 h |  | [72] | ||

| 0.5 eq. I2, Benzene, hν = 15 h |  | [73] | ||

| 0.5 eq. I2, Benzene, hν = 36 h |  | [73] | ||

| Cat. I2, Benzene, hν = 4 h |  | [74] | ||

| Cat. I2, Benzene, hν = 12 h |  | [47] | ||

| Cat. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = ? |  | [75] | ||

| Cat. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = ? |  | [75] | ||

| Cat. I2, Cyclohexane, hν = 40 h |  | [76] | ||

| Cat. I2, Benzene, hν = 7 days |  | [77] | ||

| Cat. I2, Acetone, hν = 16 h |  | [78] | ||

| 1 eq.I2, Toluene/Hexanes, hν = 60 h |  | [48] | ||

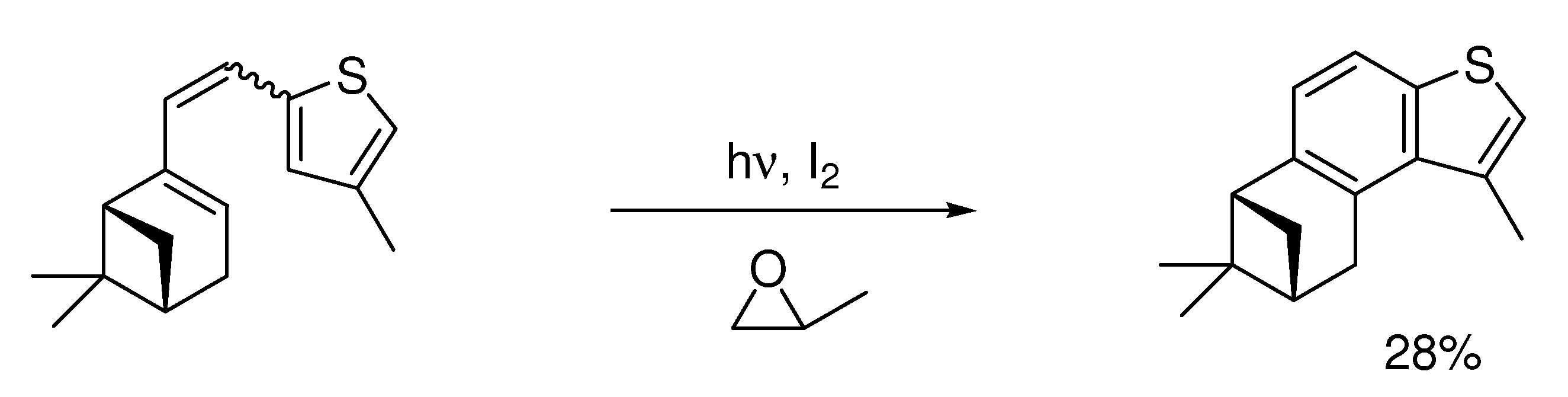

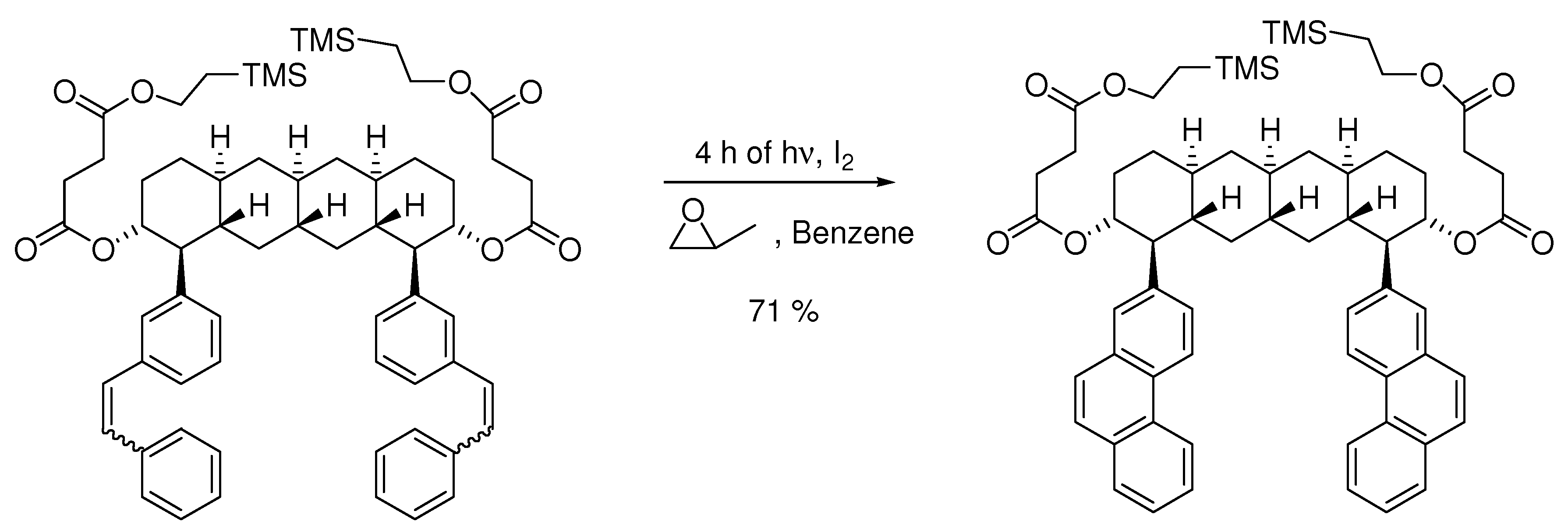

| Staring material | Conditions | Products | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2, Methyloxirane, Toluene, hν = 1.5 h |  | [38] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Toluene, hν= 4 h |  | [32] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Benzene, hν = 3 h |  | [79] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Cyclohexane, hν = 4 h |  | [24] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Cyclohexane, hν = 12 h |  | [80] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Toluene, hν = ? |  | [81] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Toluene, hν = ? |  | [82] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Benzene, hν = 40 h |  | [83] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Light petroleum, hν = 2 h |  | [84] | |||||

| I2, Epoxybutane, Toluene, hν = 1.5 h |  | [23] | |||||

| I2, Epoxybutane, Benzene, hν = 2 h |  | [85] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Cyclohexane, hν = 50 h |  | [86] | |||||

| I2, Epoxybutane, Benzene, hν = 8 h |  | [87] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Benzene, hν = 5 h |  | [88] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Benzene, hν = 6 h |  | [89] | |||||

| I2, Epoxybutane, Diethylether/ Cyclohexane, hν = 8 h |  | [90] | |||||

| I2, Methyloxirane, Benzene, hν = 12 h |  | [46] | |||||

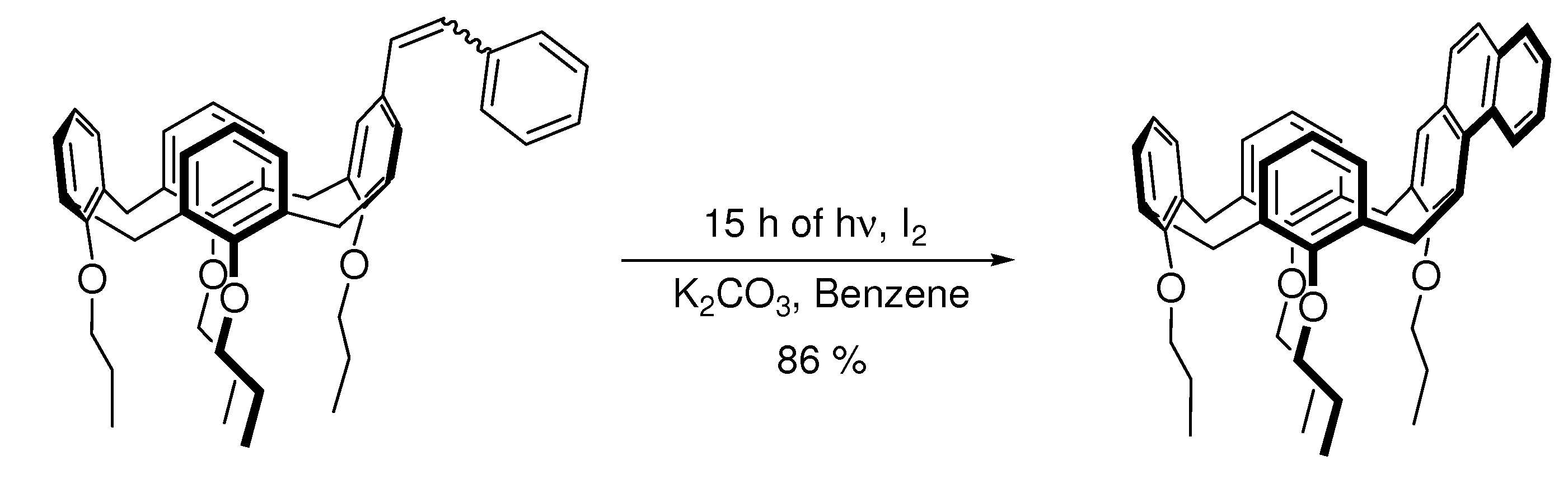

| Staring material | Conditions | Products | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cat. H2SO4, t-BuOH/Benzene, hν = 175 h |  | [29] | |

| Cat. H2SO4, t-BuOH/Benzene, hν = 26 h |  | [29] | |

| 5 eq. DBU, THF, hν = 11 h |  | [30] | |

| 5 eq. DBU, THF, hν = 6.5 h |  | [30] | |

| t-BuOK, t-BuOH/Toluene, hν = 6 h |  | [31] | |

| t-BuOK, t-BuOH/Toluene, hν = 8 h |  | [91] | |

| t-BuOK, t-BuOH/Toluene, hν = 10 h |  | [92] | |

| t-BuOK, t-BuOH/Toluene, hν = 15 min. (?) |  | [93] |

© 2010 by the authors;

Share and Cite

Jørgensen, K.B. Photochemical Oxidative Cyclisation of Stilbenes and Stilbenoids—The Mallory-Reaction. Molecules 2010, 15, 4334-4358. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15064334

Jørgensen KB. Photochemical Oxidative Cyclisation of Stilbenes and Stilbenoids—The Mallory-Reaction. Molecules. 2010; 15(6):4334-4358. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15064334

Chicago/Turabian StyleJørgensen, Kåre B. 2010. "Photochemical Oxidative Cyclisation of Stilbenes and Stilbenoids—The Mallory-Reaction" Molecules 15, no. 6: 4334-4358. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15064334

APA StyleJørgensen, K. B. (2010). Photochemical Oxidative Cyclisation of Stilbenes and Stilbenoids—The Mallory-Reaction. Molecules, 15(6), 4334-4358. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15064334