Abstract

Generalized mutual information (GMI) is used to compute achievable rates for fading channels with various types of channel state information at the transmitter (CSIT) and receiver (CSIR). The GMI is based on variations of auxiliary channel models with additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) and circularly-symmetric complex Gaussian inputs. One variation uses reverse channel models with minimum mean square error (MMSE) estimates that give the largest rates but are challenging to optimize. A second variation uses forward channel models with linear MMSE estimates that are easier to optimize. Both model classes are applied to channels where the receiver is unaware of the CSIT and for which adaptive codewords achieve capacity. The forward model inputs are chosen as linear functions of the adaptive codeword’s entries to simplify the analysis. For scalar channels, the maximum GMI is then achieved by a conventional codebook, where the amplitude and phase of each channel symbol are modified based on the CSIT. The GMI increases by partitioning the channel output alphabet and using a different auxiliary model for each partition subset. The partitioning also helps to determine the capacity scaling at high and low signal-to-noise ratios. A class of power control policies is described for partial CSIR, including a MMSE policy for full CSIT. Several examples of fading channels with AWGN illustrate the theory, focusing on on-off fading and Rayleigh fading. The capacity results generalize to block fading channels with in-block feedback, including capacity expressions in terms of mutual and directed information.

1. Introduction

The capacity of fading channels is a topic of interest in wireless communications [1,2,3,4]. Fading refers to model variations over time, frequency, and space. A common approach to track fading is to insert pilot symbols into transmit symbol strings, have receivers estimate fading parameters via the pilot symbols, and have the receivers share their estimated channel state information (CSI) with the transmitters. The CSI available at the receiver (CSIR) and transmitter (CSIT) may be different and imperfect.

Information-theoretic studies on fading channels distinguish between average (ergodic) and outage capacity, causal and non-causal CSI, symbol and rate-limited CSI, and different qualities of CSIR and CSIT that are coarsely categorized as no, perfect, or partial. We refer to [5] for a review of the literature up to 2008. We here focus exclusively on average capacity and causal CSIT as introduced in [6]. Codes for such CSIT, or more generally for noisy feedback [7], are based on Shannon strategies, also called codetrees ([8], Chapter 9.4), or adaptive codewords ([9], Section 4.1). (The term “adaptive codeword” was suggested to the author by J. L. Massey.) Adaptive codewords are usually implemented by a conventional codebook and by modifying the codeword symbols as a function of the CSIT. This approach is optimal for some channels [10] and will be our main interest.

1.1. Block Fading

A model that accounts for the different time scales of data transmission (e.g., nanoseconds) and channel variations (e.g., milliseconds) is block fading [11,12]. Such fading has the channel parameters constant within blocks of L symbols and varying across blocks. A basic setup is as follows.

- The fading is described by a state process independent of the transmitter messages and channel noise. The subscript “H” emphasizes that the states may be hidden from the transceivers.

- Each receiver sees a state process where is a noisy function of for all i.

- Each transmitter sees a state process where is a noisy function of for all i.

The state processes may be modeled as memoryless [11,12] or governed by a Markov chain [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The memoryless models are particular cases of Shannon’s model [6]. For scalar channels, is usually a complex number . Similarly, for vector or multi-input, multi-output (MIMO) channels with M- and N-dimensional inputs and outputs, respectively, is a matrix .

Consider, for example, a point-to-point channel with block-fading and complex-alphabet inputs and outputs

where the index i, , enumerates the blocks and the index ℓ, , enumerates the symbols of each block. The additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) is a sequence of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables that have a common circularly-symmetric complex Gaussian (CSCG) distribution.

1.2. CSI and In-Block Feedback

The motivation for modeling CSI as independent of the messages is simplicity. If one uses only pilot symbols to estimate the in (1), for example, then the independence is valid, and the capacity analysis may be tractable. However, to improve performance, one can implement data and parameter estimation jointly, and one can actively adjust the transmit symbols using past received symbols , , if in-block feedback is available. (Across-block feedback does not increase capacity if the state processes are memoryless; see ([22], Remark 16).) An information theory for such feedback was developed in [22], where a challenge is that code design is based on adaptive codewords that are more sophisticated than conventional codewords.

For example, suppose the CSIR is . Then, one might expect that CSCG signaling is optimal, and the capacity is an average of terms, where SNR is a signal-to-noise ratio. However, this simplification is based on constraints, e.g., that the CSIT is a function of the CSIR and that the cannot influence the CSIT. The former constraint can be realistic, e.g., if the receiver quantizes a pilot-based estimate of and sends the quantization bits to the transmitter via a low-latency and reliable feedback link. On the other hand, the latter constraint is unrealistic in general.

1.3. Auxiliary Models

This paper’s primary motivation is to further develop information theory for adaptive codewords. To gain insight, it is helpful to have achievable rates with terms. A common approach to obtain such expressions is to lower bound the channel mutual information as follows.

Suppose X is continuous and consider two conditional densities: the density and an auxiliary density . We will refer to such densities as reverse models; similarly, and are called forward models. One may write the differential entropy of X given Y as

where the first expectation in (2) is an average cross-entropy, and the second is an average informational divergence, which is non-negative. Several criteria affect the choice of : the cross-entropy should be simple enough to admit theoretical or numerical analysis, e.g., by Monte Carlo simulation; the cross-entropy should be close to ; and the cross-entropy should suggest suitable transmitter and receiver structures.

We illustrate how reverse and forward auxiliary models have been applied to bound mutual information. Assume that for simplicity.

Reverse Model: Consider the reverse density that models as jointly CSCG:

where and

is the mean square error (MSE) of the estimate . In fact, is the linear estimate with the minimum MSE (MMSE), and is the linear MMSE (LMMSE) which is independent of ; see Section 2.5. The bound in (2) gives

Thus, if X is CSCG, then we have the desired form

where the parameters h and are

The bound (6) is apparently due to Pinsker [23,24,25] and is widely used in the literature; see e.g., [18,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. The bound is usually related to channels with additive noise but (2)–(6) show that it applies generally. The extension to vector channels is given in Section 2.7 below.

Forward Model: A more flexible approach is to choose the reverse density as

where is a forward auxiliary model (not necessarily a density), is a parameter to be optimized, and

Inserting (8) into (2) we compute

The right-hand side (RHS) of (10) is called a generalized mutual information (GMI) [39,40] and has been applied to problems in information theory [41], wireless communications [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51], and fiber-optic communications [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. For example, the bounds (6) and (10) are the same if and

where h and are given by (7). Note that (11) is not a density unless but is a density. (We require to be a density to apply the divergence bound in (2).)

We compare the two approaches. The bound (5) is simple to apply and works well since the choices (7) give the maximal GMI for CSCG X; see Proposition 1 below. However, there are limitations: one must use continuous X, the auxiliary model is fixed as (11), and the bound does not show how to design the receiver. Instead, the GMI applies to continuous/discrete/mixed X and has an operational interpretation: the receiver uses rather than to decode. The framework of such mismatched receivers appeared in ([62], Exercise 5.22); see also [63].

1.4. Refined Auxiliary Models

The two approaches above can be refined in several ways, and we review selected variations in the literature.

Reverse Models: The model can be different for each , e.g., on may choose X as Gaussian with mean and variance

and where

Inserting (13) in (2) we have the bound

which improves (5) in general, since is the MMSE of X given the event . In other words, we have for all and the following bound improves (6) for CSCG X:

In fact, the bound (15) was derived in ([50], Section III.B) by optimizing the GMI in (10) over all forward models of the form

where , depend on y; see also [47,48,49]. We provide a simple proof. By inserting (16) into (8) and (9), absorbing the s parameter in and , and completing squares, one can equivalently optimize over all reverse densities of the form

where so that is a density. We next bound the cross-entropy as

with equality if ; see Section 2.5. The RHS of (18) is minimized by , so the best choice for , , gives the bound (14).

Remark 1.

Remark 3.

The RHS of (15) has a more complicated form than the RHS of (6) due to the outer expectation and conditional variance, and this makes optimizing X challenging when there is CSIR and CSIT. Also, if is known, then it seems sensible to numerically compute and directly, e.g., via Monte Carlo or numerical integration.

Remark 4.

Decoding rules for discrete X can be based on decision theory as well as estimation theory; see ([64], Equation (11)).

Forward Models: Refinements of (11) appear in the optical fiber literature where the non-linear Schrödinger equation describes wave propagation [52]. Such channels exhibit complicated interactions of attenuation, dispersion, nonlinearity, and noise, and the channel density is too challenging to compute. One thus resorts to capacity lower bounds based on GMI and Monte Carlo simulation. The simplest models are memoryless, and they work well if chosen carefully. For example, the paper [52] used auxiliary models of the form

where h accounts for attenuation and self-phase modulation, and where the noise variance depends on . Also, X was chosen to have concentric rings rather than a CSCG density. Subsequent papers applied progressively more sophisticated models with memory to better approximate the actual channel; see [53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. However, the rate gains over the model (20) are minor (≈12%) for 1000 km links, and the newer models do not suggest practical receiver structures.

A related application is short-reach fiber-optic systems that use direct detection (DD) receivers [65] with photodiodes. The paper [60] showed that sampling faster than the symbol rate increases the DD capacity. However, spectrally efficient filtering gives the channel a long memory, motivating auxiliary models with reduced memory to simplify GMI computations [61,66]. More generally, one may use channel-shortening filters [67,68,69] to increase the GMI.

Remark 5.

The ultimate GMI is , and one can compute this quantity numerically for the channels considered in this paper. We are motivated to focus on forward auxiliary models to understand how to improve information rates for more complex channels. For instance, simple let one understand properties of optimal codes, see Lemma 3, and they suggest explicit power control policies, see Theorem 2.

Remark 6.

The paper [37] (see also ([2], Equation (3.3.45)) and ([70], Equation (6))) derives two capacity lower bounds for massive MIMO channels. These bounds are designed for problems where the fading parameters have small variance so that, in effect, in (7) is small. We will instead encounter cases where grows in proportion to and the RHS of (6) quickly saturates as grows; see Remark 20.

1.5. Organization

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 defines notation and reviews basic results. Section 3 develops two results for the GMI of scalar auxiliary models with AWGN:

- Proposition 1 in Section 3.1 states a known result, namely that the RHS of (6) is the maximum GMI for the AWGN auxiliary model (11) and a CSCG X.

- Lemma 1 in Section 3.2 generalizes Proposition 1 by partitioning the channel output alphabet into K subsets, . We use to establish capacity properties at high and low SNR.

- Section 4.3 treats adaptive codewords and develops structural properties of their optimal distribution.

- Lemma 2 in Section 4.4 generalizes Proposition 1 to MIMO channels and adaptive codewords. The receiver models each transmit symbol as a weighted sum of the entries of the corresponding adaptive symbol.

- Lemma 3 in Section 4.5 states that the maximum GMI for scalar channels, an AWGN auxiliary model, adaptive codewords with jointly CSCG entries, and is achieved by using a conventional codebook where each symbol is modified based on the CSIT.

- Lemma 4 in Section 4.6 extends Lemma 3 to MIMO channels, including diagonal or parallel channels.

- Theorem 1 in Section 5.1 generalizes Lemma 3 to include CSIR; we use this result several times in Section 6.

- Lemma 5 in Section 5.3 generalizes Lemmas 1 and 2 by partitioning the channel output alphabet.

Section 6, Section 7 and Section 8 apply the GMI to fading channels with AWGN and illustrate the theory for on-off and Rayleigh fading.

- Lemma 6 in Section 6 gives a general capacity upper bound.

- Section 6.5 introduces a class of power control policies for full CSIT. Theorem 2 develops the optimal policy with an MMSE form.

- Theorem 3 in Section 6.6 provides a quadratic waterfilling expression for the GMI with partial CSIR.

Section 9 develops theory for block fading channels with in-block feedback (or in-block CSIT) that is a function of the CSIR and past channel inputs and outputs.

- Theorem 4 in Section 9.2 generalizes Lemma 4 to MIMO block fading channels;

- Section 9.3 develops capacity expressions in terms of directed information;

- Section 9.4 specializes the capacity to fading channels with AWGN and delayed CSIR;

- Proposition 3 generalizes Proposition 2 to channels with special CSIR and CSIT.

Section 10 concludes the paper. Finally, Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C, Appendix D, Appendix E, Appendix F and Appendix G provide results on special functions, GMI calculations, and proofs.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Basic Notation

Let be the indicator function that takes on the value 1 if its argument is true and 0 otherwise. Let be the Dirac generalized function with . For , define . The complex-conjugate, absolute value, and phase of are written as , , and , respectively. We write and .

Sets are written with calligraphic font, e.g., and the cardinality of is . The complement of in is where is understood from the context.

2.2. Vectors and Matrices

Column vectors are written as where M is the dimension, and T denotes transposition. The complex-conjugate transpose (or Hermitian) of is written as . The Euclidean norm of is . Matrices are written with bold letters such as . The letter denotes the identity matrix. The determinant and trace of a square matrix are written as and , respectively.

A singular value decomposition (SVD) is where and are unitary matrices and is a rectangular diagonal matrix with the singular values of on the diagonal. The square matrix is positive semi-definite if for all . The notation means that is positive semi-definite. Similarly, is positive definite if for all , and we write if is positive definite.

2.3. Random Variables

Random variables are written with uppercase letters, such as X, and their realizations with lowercase letters, such as x. We write the distribution of discrete X with alphabet as . The density of a real- or complex-valued X is written as . Mixed discrete-continuous distributions are written using mixtures of densities and Dirac- functions.

Conditional distributions and densities are written as and , respectively. We usually drop subscripts if the argument is a lowercase version of the random variable, e.g., we write for . One exception is that we consistently write the distributions and of the CSIR and CSIT with the subscript to avoid confusion with power notation.

2.4. Second-Order Statistics

The expectation and variance of the complex-valued random variable X are and , respectively. The correlation coefficient of and is where

for . We say that and are fully correlated if for some real . Conditional expectation and variance are written as and

The expressions , are random variables that take on the values , if .

The expectation and covariance matrix of the random column vector are and , respectively. We write for the covariance matrix of the stacked vector . We write for the covariance matrix of conditioned on the event . is a random matrix that takes on the matrix value when .

We often consider CSCG random variables and vectors. A CSCG has density

and we write .

2.5. MMSE and LMMSE Estimation

Assume that . The MMSE estimate of given the event is the vector that minimizes

Direct analysis gives ([71], Chapter 4)

where the last identity is called the orthogonality principle.

The LMMSE estimate of given with invertible is the vector where is chosen to minimize . We compute

and we also have the properties (22)–(24) with replaced by . Moreover, if and are jointly CSCG, then the MMSE and LMMSE estimators coincide, and the orthogonality principle (24) implies that the error is independent of , i.e., we have

2.6. Entropy, Divergence, and Information

Entropies of random vectors with densities p are written as

where we use logarithms to the base e for analysis. The informational divergence of the densities p and q is

and with equality if and only if almost everywhere. The mutual information of and is

The average mutual information of and conditioned on is . We write strings as and use the directed information notation (see [9,72])

where .

2.7. Entropy and Information Bounds

The expression (2) applies to random vectors. Choosing as the conditional density where the are modeled as jointly CSCG we obtain a generalization of (5):

The vector generalization of (6) for CSCG is

where (cf. (7))

and step in (30) follows by the Woodbury identity

and the Sylvester identity

We also have vector generalizations of (14) and (15):

2.8. Capacity and Wideband Rates

Consider the complex-alphabet AWGN channel with output and noise . The capacity with the block power constraint is

The low SNR regime (small P) is known as the wideband regime [73]. For well-behaved channels such as AWGN channels, the minimum and the slope S of the capacity vs. in bits/(3 dB) at the minimum are (see ([73], Equation (35)) and ([73], Theorem 9))

where and are the first and second derivatives of (measured in nats) with respect to P, respectively. For example, the wideband derivatives for (36) are and so that the wideband values (37) are

The minimal is usually stated in decibels, for example dB. An extension of the theory to general channels is described in ([74], Section III).

Remark 7.

A useful method is flash signaling, where one sends with zero energy most of the time. In particular, we will consider the CSCG flash density

where so that the average power is . Note that flash signaling is defined in ([73], Definition 2) as a family of distributions satisfying a particular property as . We use the terminology informally.

2.9. Uniformly-Spaced Quantizer

Consider a uniformly-spaced scalar quantizer with B bits, domain , and reconstruction points

where . The quantization intervals are

where . We will consider . For we choose .

Suppose one applies the quantizer to the non-negative random variable G with density to obtain . Let and be the probability mass functions of without and with conditioning on G, respectively. We have

and using Bayes’ rule, we obtain

3. Generalized Mutual Information

We re-derive the GMI in the usual way, where one starts with the forward model rather than the reverse density in (8). Consider the joint density and define as in (9) for . Note that neither nor must be densities. The GMI is defined in [39] to be where (see the RHS of (10))

and where the expectation is with respect to . The GMI is a lower bound on the mutual information since

Moreover, by using Gallager’s derivation of error exponents, but without modifying his “s” variable, the GMI is achievable with a mismatched decoder that uses for its decoding metric [39].

3.1. AWGN Forward Model with CSCG Inputs

A natural metric is based on the AWGN auxiliary channel where h is a channel parameter and is independent of X, i.e., we have the auxiliary model (here a density)

where h and are to be optimized. A natural input is so that (9) is

We have the following result, see [43] that considers channels of the form (1) and ([47], Proposition 1) that considers general .

Proposition 1.

Proof.

Remark 9.

Proposition 1 generalizes to vector models and adaptive input symbols; see Section 4.4.

Remark 10.

The estimate is the MMSE estimate of h:

and is the variance of the error. To see this, expand

where the final step follows by the definition of in (47).

Remark 11.

Remark 12.

The LM rate (for “lower bound to the mismatch capacity”) improves the GMI for some [40,75]. The LM rate replaces with for some function and permits optimizing s and ; see ([41], Section 2.3.2). For example, if has the form then the LM rate can be larger than the GMI; see [76,77].

3.2. CSIR and K-Partitions

We consider two generalizations of Proposition 1. The first is for channels with a state known at the receiver but not at the transmitter. The second expands the class of CSCG auxiliary models. The motivation is to obtain more precise models under partial CSIR, especially to better deal with channels at high SNR and with high rates. We here consider discrete and later extend to continuous .

CSIR: Consider the average GMI

where is the usual GMI where all densities are conditioned on . The parameters (47) and (48) for the event are now

The GMI (57) is thus

K-Partitions: Let be a K-partition of and define the auxiliary model

Observe that is not necessarily a density. We choose so that (9) becomes (cf. (45))

Define the events for . We have

and inserting (61) and (62) we have the following lemma.

Lemma 1.

Remark 13.

K-partitioning formally includes (57) as a special case by including as part of the receiver’s “overall” channel output . For example, one can partition as where .

Remark 14.

Remark 15.

One can generalize Lemma 1 and partition rather than only. However, the in (62) might not have a CSCG form.

Remark 16.

Remark 17.

The LMMSE-based GMI (68) reduces to the GMI of Proposition 1 by choosing the trivial partition with and . However, the GMI (68) may not be optimal for . What can be said is that the phase of in (64) should be the same as the phase of for all k. We thus have K two-dimensional optimization problems, one for each pair , .

Remark 18.

Suppose we choose a different auxiliary model for each , i.e., consider . The reverse density GMI uses the auxiliary model (19) which gives the RHS of (15):

Instead, the suboptimal (68) is the complicated expression

where . We show how to compute these GMIs in Appendix C.

3.3. Example: On-Off Fading

Consider the channel where are mutually independent, , and . The channel exhibits particularly simple fading, giving basic insight into more realistic fading models. We consider two basic scenarios: full CSIR and no CSIR.

Full CSIR: Suppose and

which corresponds to having (58) and (59) as

The GMI (60) with thus gives the capacity

The wideband values (37) are

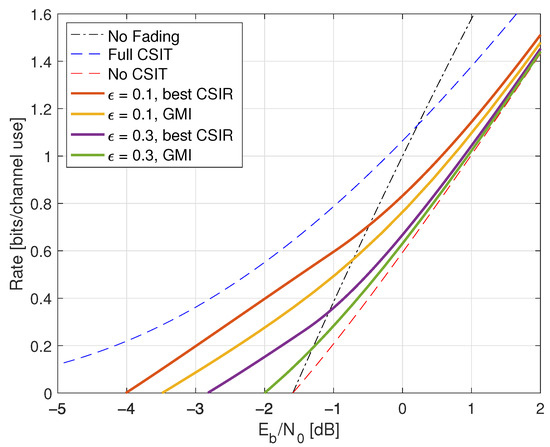

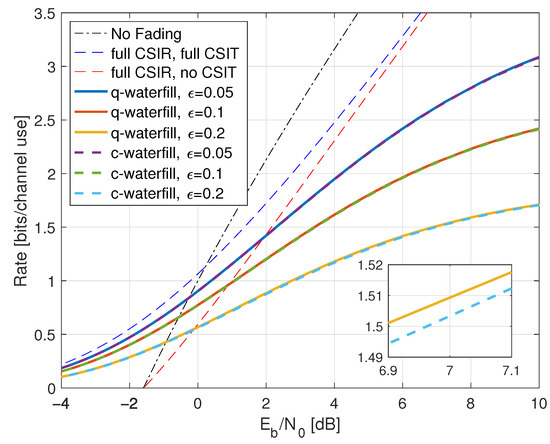

Compared with (38), the minimal is the same as without fading, namely dB. However, fading reduces the capacity slope S; see the dashed curve in Figure 1.

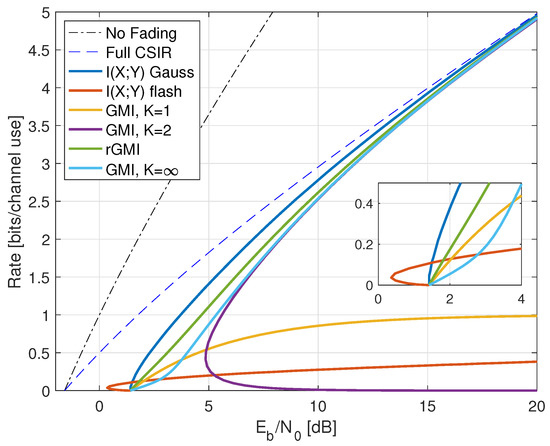

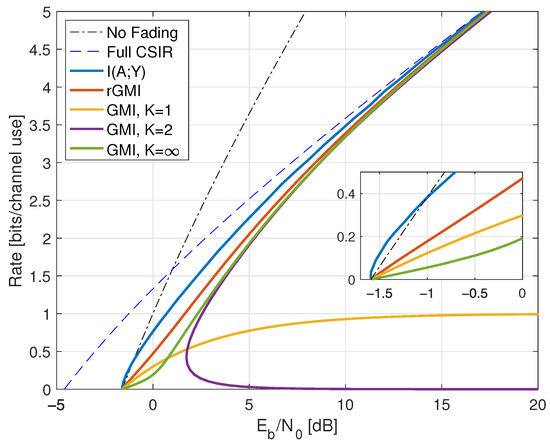

Figure 1.

Rates for on-off fading with . The curve “Full CSIR” refers to and is a capacity upper bound. Flash signaling uses ; the GMI for the partition uses the threshold .

No CSIR: Suppose and and consider the densities

The mutual information can be computed by numerical integration or by Monte Carlo integration:

where the RHS of (77) converges to for long strings sampled from . The results for are shown in Figure 1 as the curve labeled “ Gauss”.

Next, Proposition 1 gives , , and

The wideband values (37) are

so the minimal is 1.42 dB and the capacity slope S has decreased further. Moreover, the rate saturates at large SNR at 1 bit per channel use.

The “ Gauss” curve in Figure 1 suggests that the no-CSIR capacity approaches the full-CSIR capacity for large SNR. To prove this, consider the partition specified in Remark 14 with , , and . Since we are not using LMMSE auxiliary models, we must compute the GMI using the general expression (64), which is

In Appendix B.1, we show that choosing where and b is a real constant makes all terms behave as desired as P increases:

The GMI (80) of Lemma 1 thus gives the maximal value (73) for large P:

Figure 1 shows the behavior of for , , and . Effectively, at large SNR, the receiver can estimate H accurately, and one approaches the full-CSIR capacity.

Remark 19.

Consider next the reverse density GMI (69) and the forward model GMI (70). Appendix C.1 shows how to compute , , and , and Figure 1 plots the GMIs as the curves labeled “rGMI” and “GMI, K = ∞”, respectively. The rGMI curve gives the best possible rates for AWGN auxiliary models, as shown in Section 1.4. The results also show that the large-K GMI (70) is worse than the GMI at low SNR but better than the GMI of Remark 14.

Finally, the curve labeled “ Gauss” in Figure 1 suggests that the minimal is 1.42 dB even for the capacity-achieving distribution. However, we know from ([73], Theorem 1) that flash signaling (39) can approach the minimal of dB. For example, the flash rates with are plotted in Figure 1. Unfortunately, the wideband slope is ([73], Theorem 17), and one requires very large flash powers (very small p) to approach dB.

Remark 20.

As stated in Remark 6, the paper [37] (see also [2,70]) derives two capacity lower bounds. These bounds are the same for our problem, and they are derived using the following steps (see ([37], Lemmas 3 and 4)):

Now consider where are mutually independent, , , and . We have

where (84) and (85) follow by (5), in the latter case with the roles of X and Y reversed. The bound (85) works well if is small, as for massive MIMO with “channel hardening”. However, for our on-off fading model, the bound (83) is

which is worse than the and GMIs and is not shown in Figure 1.

4. Channels with CSIT

This section studies Shannon’s channel with side information, or state, known causally at the transmitter [5,6]. We begin by treating general channels and then focus mainly on complex-alphabet channels. The capacity expression has a random variable A that is either a list (for discrete-alphabet states) or a function (for continuous-alphabet states). We refer to A as an adaptive symbol of an adaptive codeword.

4.1. Model

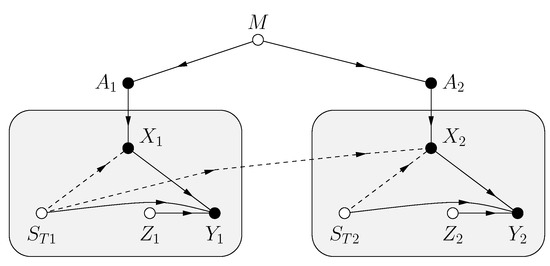

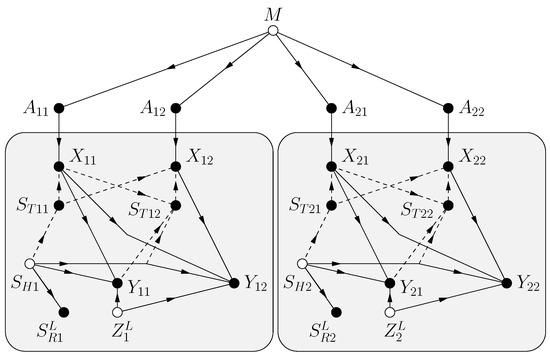

The problem is specified by the functional dependence graph (FDG) in Figure 2. The model has a message M, a CSIT string , and a noise string . The variables M, , are mutually statistically independent, and and are strings of i.i.d. random variables with the same distributions as and Z, respectively. is available causally at the transmitter, i.e., the channel input , , is a function of M and the sub-string . The receiver sees the channel outputs

for some function and .

Figure 2.

FDG for uses of a channel with CSIT. Open nodes represent statistically independent random variables, and filled nodes represent random variables that are functions of their parent variables. Dashed lines represent the CSIT influence on .

Each represents a list of possible choices of at time i. More precisely, suppose that has alphabet and define the adaptive symbol

whose entries have alphabet . Here means that is transmitted, i.e., we have . If has a continuous alphabet, we make A a function rather than a list, and we may again write . Some authors therefore write A as . (Shannon in [6] denoted our A and X as the respective X and x.)

Remark 21.

The conventional choice for A if is

where U has , , and is a phase shift. The interpretation is that U represents the symbol of a conventional codebook without CSIT, and these symbols are scaled and rotated. In other words, one separates the message-carrying U from an adaptation due to via

Remark 22.

One may define the channel by the functional relation (87), by , or by ; see Shannon’s emphasis in ([6], Theorem); see ([22], Remark 3). We generally prefer to use since we interpret A as a channel input.

Remark 23.

One can add feedback and let be a function of , but feedback does not increase the capacity if the state and noise processes are memoryless ([22], Section V).

Remark 24.

The model (87) permits block fading and MIMO transmission by choosing and as vectors [11,78].

4.2. Capacity

The capacity of the model under study is (see [6])

where forms a Markov chain. One may limit attention to A with cardinality satisfying (see ([22], Equation (56)), [79], ([80], Theorem 1))

As usual, for the cost function and the average block cost constraint

the unconstrained maximization in (90) becomes a constrained maximization over the A for which . Also, a simple upper bound on the capacity is

where step follows by the independence of A and . This bound is tight if the receiver knows .

Remark 25.

The chain rule for mutual information gives

The RHS of (94) suggests treating the channel as a multi-input, single-output (MISO) channel, and the expression (95) suggests using multi-level coding with multi-stage decoding [81]. For example, one may use polar coded modulation [82,83,84] with Honda-Yamamoto shaping [85,86].

Remark 26.

For and the conventional adaptive symbol (88), we compute and

4.3. Structure of the Optimal Input Distribution

Let be the alphabet of A and let , i.e., we have for discrete . Consider the expansions

Observe that , and hence , depends only on the marginals of A; see ([80], Section III). So define the set of densities having the same marginals as A:

This set is convex, since for any and we have

Moreover, for fixed , the expression is a convex function of , and is a linear function of . Maximizing over is thus the same as minimizing the concave function over the convex set . An optimal is thus an extreme of . Some properties of such extremes are developed in [87,88].

For example, consider and , for which (91) states that at most adaptive symbols need have positive probability (and at most adaptive symbols if ). Suppose the marginals have , and consider the matrix notation

where we write for . The optimal must then be one of the two extremes

For the first , the codebook has the property that if then while if then is uniformly distributed over .

Next, consider and marginals , that are uniform over . This case was treated in detail in ([80], Section VI.A), see also [89], and we provide a different perspective. A classic theorem of Birkhoff [90] ensures that the extremes of are the distributions for which the matrix

is a permutation matrix multiplied by . For example, for we have the two extremes

The permutation property means that is a function of , i.e., the encoding simplifies to a conventional codebook as in Remark 21 with uniformly-distributed U and a permutation indexed by such that . For example, for the first in (101) we may choose , which is independent of . On the other hand, for the second in (101) we may choose where ⊕ denotes addition modulo-2.

For , the geometry of is more complicated; see ([80], Section VI.B). For example, consider and suppose the marginals , , are all uniform. Then the extremes include related to linear codes and their cosets, e.g., two extremes for are related to the repetition code and single parity check code:

This observation motivates concatenated coding, where the message is first encoded by an outer encoder followed by an inner code that is the coset of a linear code. The transmitter then sends the entries at position of the inner codewords, which are vectors of dimension . We do not know if there are channels for which such codes are helpful.

4.4. Generalized Mutual Information

Consider the vector channel with input set and output set . The GMI for adaptive symbols is where

and the expectation is with respect to . Suppose the auxiliary model is and define

The GMI again provides a lower bound on the mutual information since (cf. (43))

where is a reverse channel density.

We next study reverse and forward models as in Section 1.3 and Section 1.4. Suppose the entries of A are jointly CSCG.

Reverse Model: We write when we consider A to be a column vector that stacks the . Consider the following reverse density motivated by (13):

A corresponding forward model is and the GMI with becomes (cf. (35))

To simplify, one may focus on adaptive symbols as in (89):

where and the are covariance matrices. We thus have (cf. (96)) and using (105) but with replaced with we obtain

Forward Model: Perhaps the simplest forward model is for some fixed value . One may interpret this model as having the receiver assume that . A natural generalization of this idea is as follows: define the auxiliary vector

where the are complex matrices, i.e., is a linear function of the entries of . For example, the matrices might be chosen based on . However, observe that is independent of . Now define the auxiliary model

where we abuse notation by using the same . The expression (103) becomes

Remark 27.

We often consider to be a discrete set, but for CSCG channels we also consider so that the sum over in (109) is replaced by an integral over .

We now specialize further by choosing the auxiliary channel where is an complex matrix, is an N-dimensional CSCG vector that is independent of and has invertible covariance matrix , and and are to be optimized. Further choose whose entries are jointly CSCG with correlation matrices

Since in (109) is independent of , we have

Moreover, is CSCG so (110) is

where

We have the following generalization of Proposition 1.

Lemma 2.

Proof.

See Appendix D. □

Remark 28.

Remark 29.

Remark 30.

Suppose that is an estimate other than (115). Generalizing (55), if we may choose

where

Appendix D shows that (102) then simplifies to (cf. (56))

4.5. Optimal Codebooks for CSCG Forward Models

The following Lemma maximizes the GMI for scalar channels and A with CSCG entries without requiring A to have the form (89). Nevertheless, this form is optimal, and we refer to ([10], page 2013) and Section 6.4 for similar results. In the following, let for all .

Lemma 3.

Proof.

See Appendix E. □

Remark 32.

The expression (121) is based on (A58) in Appendix E and can alternatively be written as where

Remark 33.

The power levels may be optimized, usually under a constraint such as .

Remark 34.

By the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, we have

Furthermore, equality holds if and only if is a constant for each , but this case is not interesting.

4.6. Forward Model GMI for MIMO Channels

The following lemma generalizes Lemma 3 to MIMO channels without claiming a closed-form expression for the optimal GMI. Let for all .

Lemma 4.

A GMI (102) for the channel , an adaptive vector A with jointly CSCG entries, the auxiliary model (111), and with fixed is given by (112) that we write as

where for unitary we have

and and are unitary and rectangular diagonal matrices, respectively, of the SVD

for all , and the are unitary matrices. The GMI (124) is achieved by choosing the symbols (cf. (122) and (A87) below):

and for some invertible matrix and a common M-dimensional vector . One may maximize (124) over the unitary .

Proof.

See Appendix G. □

Using Lemma 4, the theory for MISO channels with is similar to the scalar case of Lemma 3; see Remark 35 below. However, optimizing the GMI is more difficult for because one must optimize over the unitary matrices in (125); see Remark 36 below.

Remark 35.

Remark 36.

Remark 37.

Remark 38.

For general , one might wish to choose diagonal and a product model

where the are scalar AWGN channels

with possibly different and for each m. Consider also

for some complex weights , i.e., is a weighted sum of entries from the list . The maximum GMI is now the same as (134) but without requiring the actual channel to have the form (132).

Remark 39.

If the actual channel is then

where the final step follows because forms a Markov chain. The expression (135) is useful because it separates the effects of the channel and the transmitter.

5. Channels with CSIR and CSIT

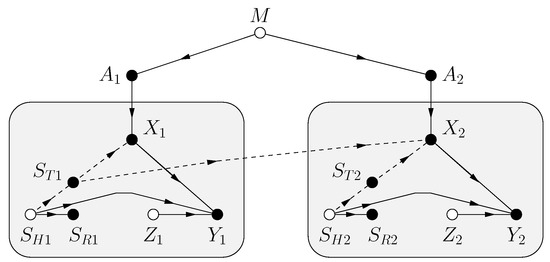

Shannon’s model includes CSIR [11]. The FDG is shown in Figure 3 where there is a hidden state , the CSIR and CSIT are functions of , and the receiver sees the channel outputs

for some function and . (By defining and calling the hidden channel state we can include the case where and are noisy functions of .) As before, M, , are mutually statistically independent, and and are i.i.d. strings of random variables with the same distributions as and Z, respectively. Observe that we have changed the notation by writing Y for only part of the channel output. The new Y (without the ) is usually called the “channel output”.

Figure 3.

FDG for channel uses with different CSIT and CSIR. The hidden channel state permits dependent and .

5.1. Capacity and GMI

Forward Model: Consider the expansion

where is the GMI (102) with all densities conditioned on . We choose the forward model

where similar to (109) we define

for complex weights , i.e., is a weighted sum of entries from the list . We have the following straightforward generalization of Lemma 3.

Theorem 1.

Remark 41.

To establish Theorem 1, the receiver may choose to be independent of . Alternatively, the receiver may choose . Both choices give the same GMI since the expectation in (144) does not depend on the scaling of ; see Remark 31.

Remark 42.

Remark 43.

Remark 44.

A related model is a compound channel where is indexed by the parameter ([91], Chapter 4). The problem is to find the maximum worst-case reliable rate if the transmitter does not know . Alternatively, the transmitter must send its message to all receivers indexed by . A compound channel may thus be interpreted as a broadcast channel with a common message.

5.2. CSIT@ R

An interesting specialization of Shannon’s model is when the receiver knows and can determine . We refer to this scenario as CSIT@R. The model was considered in ([10], Section II) when is a function of . More generally, suppose is a function of . The capacity (138) then simplifies to (see ([10], Proposition 1))

where step follows because is a function of ; step follows because A and are independent, X is a function of , and forms a Markov chain; and step follows because one may optimize separately for each .

As discussed in [10], a practical motivation for this model is when the CSIT is based on error-free feedback from the receiver to the transmitter. In this case, where is a function of , the expression (144) becomes

Remark 45.

The insight that one can replace adaptive symbols A with channel inputs X when X is a function of A and past Y appeared for two-way channels in ([9], Section 4.2.3) and networks in ([22], Section V.A), ([72], Section IV.F).

5.3. MIMO Channels and K-Partitions

We consider generalizations to MIMO channels and K-partitions as in Section 3.2.

MIMO Channels: Consider the average GMI

and choose the parameters (113) and (114) for the event . We have

and the GMI (149) is (cf. (60) and (112))

K-Partitions: Let be a K-partition of and define the events for . As in Remark 13, K-partitioning formally includes (149) as a special case by including as part of the receiver’s “overall” channel output . The following lemma generalizes Lemma 1.

Lemma 5.

A GMI with for the channel is

where the and , , can be optimized.

Remark 46.

Remark 47.

Consider Remark 14 and choose , , . The GMI (154) then has only the term, and it again remains to select , , and .

Remark 48.

Remark 49.

We may proceed as in Remark 18 and consider large K. These steps are given in Appendix F.

6. Fading Channels with AWGN

This section treats scalar, complex-alphabet, AWGN channels with CSIR for which the channel output is

where are mutually independent, , and . The capacity under the power constraint is (cf. (138))

However, the optimization in (160) is often intractable, and we desire expressions with terms to gain insight. We develop three such expressions: an upper bound and two lower bounds. It will be convenient to write .

Capacity Upper Bound: We state this bound as a lemma since we use it to prove Proposition 2 below.

Lemma 6.

Proof.

Consider the steps

where step is because A and are independent, and step follows by the entropy bound

which we applied with . Finally, we compute . □

Reverse Model GMI: Consider the adaptive symbol (88) and the GMI (139). We expand the variances in (139) as

Appendix C shows that one may write

and

We use the expressions (164) and (165) to compute achievable rates by numerical integration. For example, suppose that and , i.e., we have full CSIR and no CSIT. The averaging density is then

and the variance simplifies to the capacity-achieving form

Forward Model GMI: A forward model GMI is given by Theorem 1 where

so that (143) becomes

Remark 50.

Remark 51.

Remark 52.

For MIMO channels we replace (159) with

where are mutually independent and . One usually considers the constraint .

Remark 53.

6.1. CSIR and CSIT Models

We study two classes of CSIR, as shown in Table 1. The first class has full (or “perfect”) CSIR, by which we mean either or . The motivation for studying the latter case is that it models block fading channels with long blocks where the receiver estimates using pilot symbols, and the number of pilot symbols is much smaller than the block length [10]. Moreover, one achieves the upper bound (161), see Proposition 2 below.

We coarsely categorize the CSIT as follows:

- Full CSIT: ;

- CSIT@R: where is the quantizer of Section 2.9 with ;

- Partial CSIT: is not known exactly at the receiver.

The capacity of the CSIT@R models is given by expressions [10,92]; see also [93]. The partial CSIT model is interesting because achieving capacity generally requires adaptive codewords and closed-form capacity expressions are unavailable. The GMI lower bound of Theorem 1 and Remark 42 and the capacity upper bound of Lemma 6 serve as benchmarks.

The partial CSIR models have being a lossy function of H. For example, a common model is based on LMMSE channel estimation with

where and are uncorrelated. The CSIT is categorized as above, except that we consider for some function rather than .

To illustrate the theory, we study two types of fading: one with discrete H and one with continuous H, namely

For on-off fading we have and for Rayleigh fading we have .

Remark 54.

For channels with partial CSIR, we will study the GMI for partitions with and . The full CSIT model has received relatively little attention in the literature, perhaps because CSIR is usually more accurate than CSIT ([5], Section 4.2.3).

6.2. No CSIR, No CSIT

Without CSIR or CSIT, the channel is a classic memoryless channel [94] for which the capacity (160) becomes the usual expression with and . For CSCG X and , the reverse and forward model GMIs (139) and (168) are the respective

For example, the forward model GMI is zero if .

6.3. Full CSIR, CSIT@ R

Consider the full CSIR models with and CSIT@R. The capacity is given by expressions that we review.

First, the capacity with (no CSIT) is

The wideband derivatives are (see (37))

so that the wideband values (37) are (see ([73], Theorem 13))

The minimal is the same as without fading, namely dB. However, Jensen’s inequality gives with equality if and only if . Thus, fading reduces the capacity slope S.

More generally, the capacity with full CSIR and is (see [10])

To optimize the power levels , consider the Lagrangian

where is a Lagrange multiplier. Taking the derivative with respect to , we have

as long as . If this equation cannot be satisfied, choose . Finally, set so that .

For example, consider and . We then have and therefore

where is chosen so that . The capacity (178) is then (see ([95], Equation (7)))

Consider now the quantizer of Section 2.9 with . We have two equations for , namely

Observe the following for (183) and (184):

- both and decrease as increases;

- the maximal permitted by (183) is which is obtained with ;

- the maximal permitted by (184) is which is obtained with .

Thus, if , then at P below some threshold, we have and . The capacity in nats per symbol at low power and for fixed is thus

where we used

for small x. The wideband values (37) are

One can thus make the minimum approach if one can make as large as desired by increasing .

6.4. Full CSIR, Partial CSIT

Consider first the full CSIR and then the less informative .

: We have the following capacity result that implies this CSIR is the best possible since one can achieve the same rate as if the receiver sees both H and ; see the first step of (162). We could thus have classified this model as CSIT@R.

Proposition 2

Proof.

Achievability follows by Theorem 1 with Remark 51. The converse is given by Lemma 6. □

Remark 56.

Proposition 2 gives an upper bound and (thus) a target rate when the receiver has partial CSIR. For example, we will use the K-partition idea of Lemma 1 (see also Remark 46) to approach the upper bound for large SNR.

Remark 57.

Proposition 2 partially generalizes to block-fading channels; see Proposition 3 in Section 9.5.

: The capacity is (138) with

where and where

and

For example, if each entry of A is CSCG with variance then

In general, one can compute numerically by using (190)–(192), but the calculations are hampered if the integrals in (191) and (192) do not simplify.

For the reverse model GMI (139), the averaging density in (164) and (165) is here

We use numerical integration to compute the GMI.

To obtain more insight, we state the forward model rates of Theorem 1 and Remark 51 as a Corollary.

Corollary 1.

An achievable rate for the fading channels (159) with and partial CSIT is the forward model GMI

where

and

Remark 58.

Jensen’s inequality gives

by the concavity of the square root. Equality holds if and only if is a constant given .

Remark 59.

Remark 60.

For large P, the in (196) saturates unless for all , i.e., the high-SNR capacity is the same as the capacity without CSIT. The CSIT thus must become more accurate as P increases to improve the rate.

6.5. Partial CSIR, Full CSIT

Suppose is a (perhaps noisy) function of H; see (172). The capacity is given by (160) for which we need to compute and . The GMI with a K-partition of the output space can be helpful for these problems. We assume that the CSIR is either or for some transmitter threshold t; see [95].

Suppose that . We then have

Now select the to be jointly CSCG with variances and correlation coefficients

and where . We then have

As in (97), and therefore depend only on the marginals of A and not on the . We thus have the problem of finding the that minimize

However, we study the conventional A in (88) for simplicity.

For the reverse model GMI (139), the averaging density in (164) and (165) is (cf. (194))

We again use numerical integration to compute the GMI.

For the forward model GMI, consider the same model and CSCG X as in Theorem 1. Since H is a function of , we use (169) in Remark 50 to write

where (see (170))

The transmitter compensates for the phase of H, and it remains to adjust the transmit power levels . We study five power control policies and two types of CSIR; see Table 2.

Table 2.

Power Control Policies and Minimal SNRs.

Heuristic Policies: The first three policies are reasonable heuristics and have the form

for some choice of real a and where

In particular, choosing , we obtain policies that we call truncated constant power (TCP), truncated matched filtering (TMF), and truncated channel inversion (TCI), respectively; see ([5], page 487), [95]. For such policies, we compute

These policies all have the form for some function that is independent of P. The minimum SNR in (37) with replaced with the GMI is thus

For instance, consider the threshold (no truncation). The TCP () and TMF () policies have while TCI () has . For TCP, TMF, and TCI, we compute the respective

Applying Jensen’s inequality to the square root, square, and inverse functions in (210)–(212), we find that for :

- the minimum of TCP and TCI is larger (worse) than dB unless there is no fading;

- the minimum of TMF is smaller (better) than dB unless .

However, we emphasize that these claims apply to the GMI and not necessarily the mutual information; see Section 8.4.

GMI-Optimal Policy: The fourth policy is optimal for the GMI (202) and has the form of an MMSE precoder. This policy motivates a truncated MMSE (TMMSE) policy that generalizes and improves TMF and TCI.

Taking the derivative of the Lagrangian

with respect to we have the following result.

Theorem 2.

The optimal power control policy for the GMI for the fading channels (159) with is

where is chosen so that and

Proof.

Remark 62.

Remark 63.

Consider the expression (214). We effectively have a matched filter for small ; for large , we effectively have a channel inversion. Recall that LMMSE filtering has similar behavior for low and high SNR, respectively.

Remark 64.

A heuristic based on the optimal policy is a TMMSE policy where the transmitter sets if , and otherwise uses (214) but where , are independent of h. There are thus four parameters to optimize: λ, α, β, and t. This TMMSE policy will outperform TMF and TCI in general, as these are special cases where and , respectively.

: For this CSIR, the GMI (202) simplifies to and the heuristic policy (TCP, TMF, TCI) rates are

Moreover, the expression (209) gives

For TCP, TMF, and TCI, we compute the respective

Again applying Jensen’s inequality to the various functions in (221)–(223), we find that:

- the minimum of TMF is smaller (better) than that of TCP and TCI unless there is no fading, or if the minimal is ;

- the best threshold for TMF is and the minimal is dB.

For the optimal policy, the parameters and in (215) and (216) are constants independent of h, see Remark 62, and the TMMSE policy with is the GMI-optimal policy.

Remark 65.

The TCI channel densities are

Remark 66.

At high SNR, one might expect that the receiver can estimate precisely even if . We show that this is indeed the case for on-off fading by using the partition (154) of Remark 46. Moreover, the results prove that at high SNR one can approach ; see Section 7.3.

Remark 67.

For Rayleigh fading, the GMI with in (154) is helpful for both high and low SNR. For instance, for and TCI, the GMI approaches the mutual information for as the SNR increases; see Remark 74 in Section 8.4. We further show that for , the TCI policy can achieve a minimal of dB, see (301) in Section 8.4.

Moreover, the expression (209) is

For TCP, TMF, and TCI we compute the respective

- the minimum of all policies can be better than dB by choosing ;

- the minimum of TMF is smaller (better) than that of TCP and TCI unless there is no fading or the minimal is .

For the optimal policy, Remark 62 points out that and depend on only. We compute

where for we have

Remark 68.

The GMI (224) for TCI () is the mutual information . To see this, observe that the model has

and thus we have for all .

6.6. Partial CSIR, CSIT@ R

Suppose next that is a noisy function of H (see for instance (172)) and . The capacity is given by (147) and we compute

where writing we have

For example, if is CSCG with variance then

One can compute numerically using (231) and (232). However, optimizing over is usually difficult.

For the reverse model GMI (139), the averaging density in (164) and (165) is now (cf. (194) and (201))

We use numerical integration to compute the rates.

The forward model GMI again gives more insight. Define the channel gain and variance as the respective

Theorem 3.

An achievable rate for AWGN fading channels (159) with power constraint and with partial CSIR and is

where . The optimal power levels are obtained by solving

In particular, if determines (CSIR@T) then we have the quadratic waterfilling expression

where

and where λ is chosen so that .

Proof.

Remark 69.

The optimal power control policy with CSIT@R and CSIR@T can be written explicitly by solving the quadratic in (239). The result is

where we have discarded the dependence on for convenience. The alternative form (239) relates to the usual waterfilling where the left-hand side of (239) is . Observe that gives conventional waterfilling.

Remark 70.

As in Section 3.3, we show that at high SNR the GMI of Remark 42 approaches the upper bound of Proposition 2 in some cases; see Section 7.4. The channel parameters depend on , and we choose and for all .

7. On-Off Fading

Consider again on-off fading with . We study the scenarios listed in Table 1. The case of no CIR and no CSIT was studied in Section 3.3.

7.1. Full CSIR, CSIT@ R

Consider . The capacity with (no CSIT) is given by (175) (cf. (73)):

and the wideband values are given by (177) (cf. (74)); the minimal is and the slope is .

The capacity with (or ) increases to

where and . This capacity is also achieved with since there are only two values for G. We compute and , and therefore

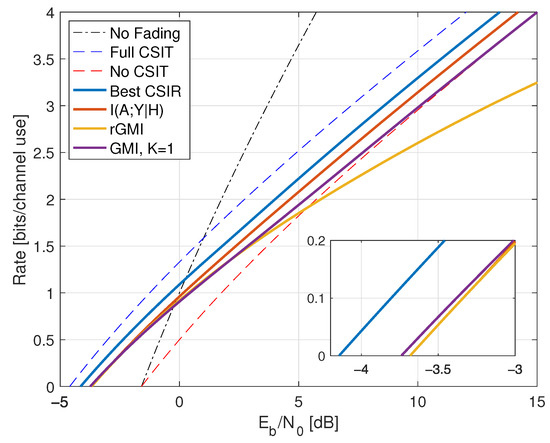

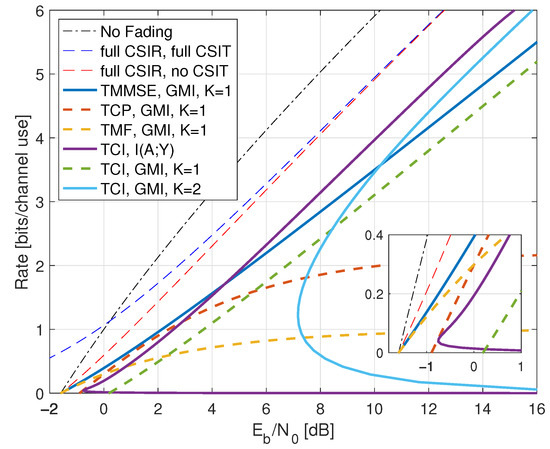

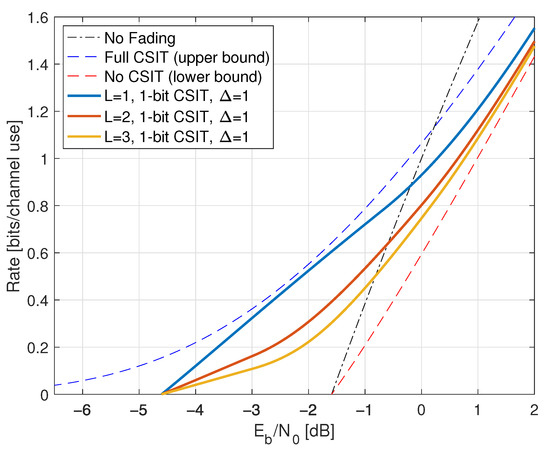

The power gain due to CSIT compared to no fading is thus 3.01 dB, but the capacity slope is the same. The rate curves are compared in Figure 4.

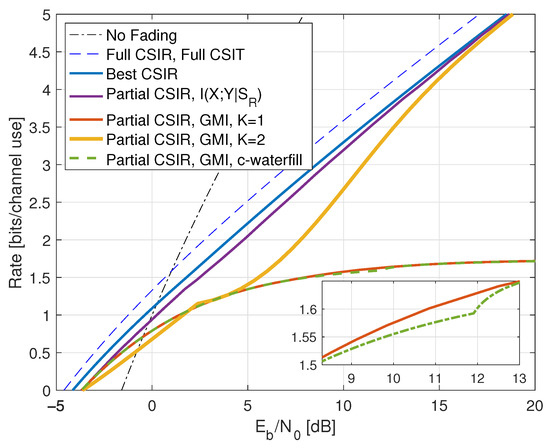

Figure 4.

Rates for on-off fading with full CSIR and partial CSIT with noise parameter . The curve “Best CSIR” shows the capacity with . The curves for , the reverse model GMI (rGMI), and the forward model GMI (GMI, K = 1) are for with CSCG inputs . The and rGMI curves are indistinguishable in the inset.

7.2. Full CSIR, Partial CSIT

Consider next noisy CSIT with and

: The capacity of Proposition 2 is

Optimizing the power levels, we have

Figure 4 shows for as the curve labeled “Best CSIR”. For , we compute

where is the binary entropy function. For example, if then for one gains bits over the capacity without CSIT. This translates to an SNR gain of dB. On the other hand, for we have , , and the capacity is

We have and lose a fraction of of the power as compared to having full CSIT (). For example, if , the minimal is approximately dB.

: To compute in (190), we write (191) and (193) for CSCG as

Figure 4 shows the rates as the curve labeled “”. This curve was computed by Monte Carlo integration with and , which is near-optimal for the range of SNRs depicted.

The reverse model GMI (139) requires . We show how to compute this variance in Appendix C.2 by applying (164) and (165). Figure 4 shows the GMIs as the curve labeled “rGMI”, where we used the same power levels as for the curve. The two curves are indistinguishable for small P, but the “rGMI” rates are poor at large P. This example shows that the forward model GMI with optimized powers can be substantially better than the reverse model GMI with a reasonable but suboptimal power policy.

The forward model GMI (195) is

where is given by (196) with

Applying Remark 61, the optimal power control policy is

where

and is chosen so that . Figure 4 shows the resulting GMI as the curve labeled “GMI, K = 1”. At low SNR, we achieve the rate and the optimal power control has so that

and therefore

We have and lose a fraction of of the power as compared to having full CSIT (). For example, if , the minimal is approximately dB.

We remark that the and reverse model GMI curves lie above the forward model curve if we choose the same power policy as for the forward channel.

7.3. Partial CSIR, Full CSIT

This section studies . The capacity with partial CSIR is given by (138) for which we need to compute and . We consider two cases.

: Here we recover the case with full CSIR by choosing t to satisfy .

: The best power policy clearly has and . The mutual information is thus and the channel densities are (cf. (75) and (76))

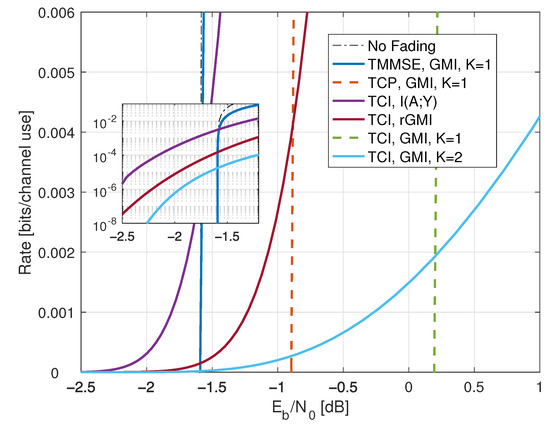

The rates are shown in Figure 5. Observe that the low-SNR rates are larger than without fading; this is a consequence of the slightly bursty nature of transmission.

Figure 5.

Rates for on-off fading with and . The GMI for the partition uses the threshold .

The reverse model GMI (139) requires . We compute this variance in Appendix C.3 by using (164) and (165) with (201) and . Figure 5 shows the GMIs as the curve labeled “rGMI”.

Next, the TCP, TMF, TCI, and TMMSE policies are the same for , since they use and . The resulting rate is given by (202)–(204) with , , and and

The rates are plotted in Figure 5 as the curve labeled “GMI, K = 1”. This example again shows that choosing is a poor choice at high SNR.

To improve the auxiliary model at high SNR, consider the GMI (154) with and the subsets (65). We further choose the parameters , , , , and adaptive coding with , , , where . The GMI (154) is

In Appendix B.2, we show that choosing where and b is a real constant makes all terms behave as desired as P increases:

We thus have

Figure 5 shows the behavior of for and as the curve labeled “GMI, K = 2”. As for the case without CSIT, the receiver can estimate H accurately at large SNR, and one approaches the capacity with full CSIR.

Finally, the large-K forward model rates are computed using (70) but where replaces X. One may again use the results of Appendix C.3 and the relations

The rates are shown as the curve labeled “GMI, K = ∞” in Figure 5. So again, the large-K forward model is good at high SNR but worse than the best model at low SNR.

7.4. Partial CSIR, CSIT@ R

Consider partial CSIR with and

where . We thus have both CSIT@R and CSIR@T. To compute in (230), we write (231) and (232) as

where is CSCG. We choose the transmit powers and as in (250) to compare with the best CSIR. Figure 6 shows the resulting rates for as the curve labeled “Partial CSIR, ”. Observe that at high SNR, the curve seems to approach the best CSIR curve from Figure 4 with . We prove this by studying a forward model GMI with .

Figure 6.

Rates for on-off fading with partial CSIR and CSIT@R. The curve “Best CSIR” shows the capacity with . The mutual information and the GMI are for and with CSCG inputs . The GMI for the partition uses . The curve labeled ‘c-waterfill’ shows the conventional waterfilling rates.

The reverse model GMI requires , which can be computed by simulation; see Appendix C.4. However, optimizing the powers seems difficult. We instead focus on the forward model GMI of Theorem 3 for which we compute

and therefore (237) is

For CSIR@T, the optimal power control policy is given by the quadratic waterfilling specified by (239) or (245):

The rates are shown in Figure 6 as the curve labeled “Partial CSIR, GMI, K = 1”. Observe that at high SNR the GMI (263) saturates at

For example, for , we approach bits at high SNR. On the other hand, at low SNR, the rate is maximized with and so that . We thus achieve a fraction of of the power compared to full CSIT. For example, if , the minimal is approximately dB.

Figure 6 also shows the conventional waterfilling rates as the curve labeled “Partial CSIR, GMI, c-waterfill”. These rates are almost the same as the quadratic waterfilling rates except for the range of between 9 to 13 dB shown in the inset.

To improve the auxiliary model at high SNR, we use a GMI with (see Remark 70)

for . The receiver chooses (see Remark 41) and we have (see Remark 42)

where the , , are given by (122). We consider and that scale in proportion to P. In this case, Appendix B.3 shows that choosing where gives the (best) full-CSIR capacity for large P, which is the rate specified in (249):

In other words, by optimizing and , at high SNR the GMI can approach the capacity of Proposition 2. This is expected since the receiver can estimate reliably at high SNR.

Figure 6 shows the behavior of this GMI and , and where we have chosen and according to (250). The abrupt change in slope at approximately 2.5 dB is because becomes positive beyond this . Keeping for up to about 12 dB gives better rates, but for high SNR one should choose the powers according to (250).

8. Rayleigh Fading

Rayleigh fading has . The random variable thus has the density . Section 8.1 and Section 8.2 review known results.

8.1. No CSIR, No CSIT

Suppose and . The densities to compute for CSCG X are

The minimum is approximately 9.2 dB, and the forward model GMI (174) is zero. The capacity is achieved by discrete and finite X [96], and at large SNR, the capacity behaves as [97]. Further results are derived in [98,99,100,101,102].

8.2. Full CSIR, CSIT@ R

The capacity (175) for (no CSIT) is

where the exponential integral is given by (A4) below. The wideband values are given by (177):

The minimal is dB, but the fading reduces the capacity slope. At high SNR, we have

where is Euler’s constant. The capacity thus behaves as for the case without fading but with an SNR loss of approximately 2.5 dB.

The capacity (182) with (or ) is (see ([95], Equation (7)))

where is given by (181) and is chosen so that

At low SNR we have large and using the approximation (A7) below we compute

We thus have and the minimal is .

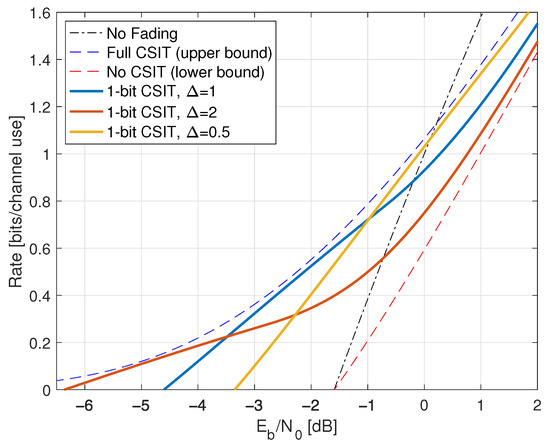

Figure 7 shows the capacities for and . The minimum value is

and for we gain 3 dB, 4.8 dB, 1.8 dB, respectively, over no CSIT at low power. Note that one bit of feedback allows one to approach the full CSIT rates closely.

Figure 7.

Capacities for Rayleigh fading with full CSIR, a one-bit quantizer with threshold , and CSIT@R.

Remark 71.

For the scalar channel (159), knowing H at both the transmitter and receiver provides significant gains at low SNR [73] but small gains at high SNR ([95], Figure 4) as compared to knowing H at the receiver only. Furthermore, the reliability can be improved ([78], Figures 5–7). Significant gains are also possible for MIMO channels.

8.3. Full CSIR, Partial CSIT

Consider noisy CSIT with

We begin with the most informative CSIR.

: Proposition 2 gives the capacity

It remains to optimize , and . The two equations for the Lagrange multiplier are

where and . The rates are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Capacities for Rayleigh fading, , and a one-bit quantizer with threshold , and various CSIT error probabilities .

For fixed and large P, we have and approach the capacity (269) without CSIT. In contrast, for small P we may use similar steps as for (183) and (184). Observe the following for (278) and (279):

Thus, if and , then for P below some threshold we have , and the capacity is

We compute which is given by (281) so that , as expected from (274). For example, for and we have and therefore the minimal is approximately dB.

The best is the unique solution of the equation

and the result is . We have the simple bounds

where the left inequality follows by taking logarithms and using , and the right inequality follows by using in (283). For example, for we have , and for we have .

: For the less informative CSIR, one may use (191) and (193) to compute . The reverse model GMI requires , which can be computed by simulation; see Appendix C.2. Again, however, optimizing the powers seems difficult. We instead focus on the forward model GMI of Corollary 1, which is

where

and

It remains to optimize , and . Computing the derivatives seems complicated, so we use numerical optimization for fixed as in Figure 8. The results are shown in Figure 9. For fixed and large P, it is best to choose so that and we approach the rate of no CSIT. For small P, however, the best is no longer zero and is smaller than (281).

Figure 9.

Rates for Rayleigh fading, and , a one-bit quantizer with threshold , and various . The curves labeled “best CSIR” show the capacities with . The curves labeled “GMI” show the rates (285) for the optimal powers and .

8.4. Partial CSIR, Full CSIT

Consider and suppose we choose the to be jointly CSCG with variances and correlation coefficients

and where . We then have

As in (97), and depend only on the marginals of A and not on the . We thus have the problem of finding the that minimize

We will use fully-correlated as discussed in Section 6.5. We again consider and .

: For the heuristic policies, the power (206) is

and the rate (219) is

where is the upper incomplete gamma function; see Appendix A.3. Moreover, the expression (220) is

We remark that where is the gamma function. We further have

For example, the TCP policy () has . At low SNR, it turns out that the best choice is for which we have . The minimum in (222) is thus dB. At high SNR, the best choice is so that (289) with gives

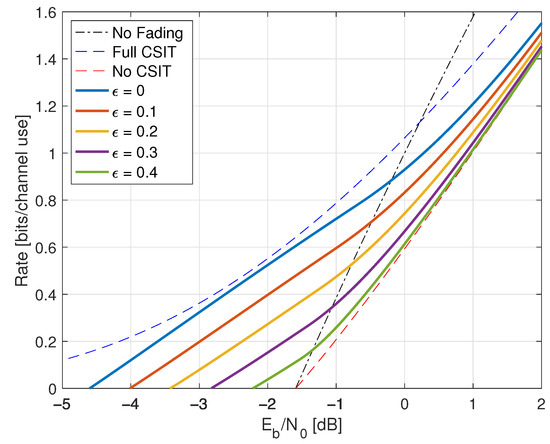

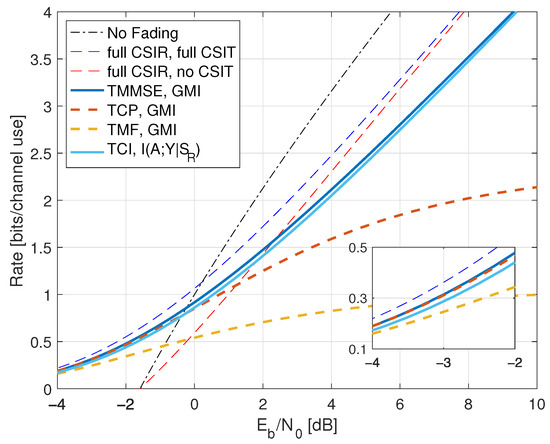

The TCP rate thus saturates at bits per channel use; see the curve labeled “TCP, GMI, K = 1” in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Rates for Rayleigh fading with and . The threshold t was optimized for the curves, while for the and curves. The GMI uses .

The TMF policy () has . The best choice is for which we have and and therefore (289) is

The minimum in (222) is dB, and at high SNR, the TMF rate saturates at 1 bit per channel use. The rates are shown as the curve labeled “TMF, GMI, K = 1” in Figure 10.

The TCI policy () has and using and gives

The minimum in (290) is

Optimizing over t by taking derivatives (see (A5) below), the best t satisfies the equation which gives and the minimal is approximately 0.194 dB. On the other hand, for large SNR, we may choose and using for small t gives

Since the pre-log is at most 1, the capacity grows with pre-log 1 for large P. We see that TMF is best at small P while TCI is best at large P. The rates are shown as the curve labeled “TCI, GMI, K = 1” in Figure 10.

The simple channel output of TCI permits further analysis. Using Remark 65, we compute the mutual information by numerical integration; see the curve labeled “TCI, ” in Figure 10. We see that at high SNR, the TCI mutual information is larger than the GMI for TCP, TMF, and (of course) TCI. Moreover, as we show, the TCI mutual information can work well at low SNR.

Motivated by Section 7.3 and Figure 5, we again use the GMI (154) with and (65). We further choose , , and

The expression (154) simplifies to

The GMI (295) exhibits interesting high and low SNR scaling by choosing the following thresholds .

- Inserting , we thus haveWe further have by using (A6) in Appendix A.2, and the high-SNR slope of the GMI matches the slope of but the additive gap to increases. The high SNR rates are shown as the curve labeled “TCI, GMI, K = 2” in Figure 10 for .

- For low SNR, we choosefor a constant . As P decreases, both t and increase and Appendix B.4 shows that

Figure 11.

Low-SNR rates for Rayleigh fading with and . The threshold t was optimized for the curves, while for the , rGMI, and curves. The GMI uses . The TMF and TMMSE GMIs are indistinguishable for this range of rates.

Figure 11 shows that the TCI mutual information achieves a minimal below dB. At dB, we computed and . The partition is thus useful to prove that TCI can achieve arbitrarily close to zero. Figure 11 also shows the reverse model GMI as the curve labeled “TCI, rGMI” which has the rate at dB.

We compare the full CSIR and full CSIT rates. At high SNR, the GMI for achieves the same capacity pre-log as . At low SNR, recall from (271) that with full CSIR/CSIT we have . To compare the rates for similar , we set , where t is as in (299) and . The TCI GMI without CSIR is approximately while the full CSIR rate (271) is approximately . Thus, the GMI with no CSIR is a fraction of the full CSIR capacity.

Moreover, the expression (225) is

which is the same as (290) except for the factor in the denominator. This implies that the minimal can be improved for .

Remark 73.

As pointed out in Remark 68, the TCI GMI (306) is . One can also understand this by observing that the receiver knows for all G. The mutual information is thus related to the rate (189) of Proposition 2.

The minimal in (303) are the respective

The above expressions mean that, for all three policies, we can make the minimal as small as desired by increasing t. For example, for TCI, we can bound (see (A9) below)

TCI thus has a slightly larger (slightly worse) minimal than TMF for the same t, as discussed after (212).

For large P, the TCP rate (304) is optimized by and the rate saturates at bits per channel use. The TMF rate (305) is optimized with , and the rate saturates at 1 bit per channel use. For the TCI rate (306), we again choose and use for small t to show that the capacity grows with pre-log 1:

Again, TMF is best at small P while TCI is best at large P.

Remark 74.

Optimal Policy: Consider now the optimal power control policy. Suppose first that for which Theorem 2 gives the TMMSE policy with :

For Rayleigh fading, we thus have (see (A13) below)

with the two expressions (see (A12) and (A14) below)

Given P and , we may compute from (312). We then search for the optimal for fixed P. The rates are shown as the curve labeled “TMMSE, GMI, K = 1” in Figure 10 and Figure 11 and we see that the TMMSE strategy has the best rates.

Consider next and the TMMSE policy. We compute (see (A13) below)

and (see (A12) and (A14) below)

We optimize as for the case: given P, , t, we compute from (315). We then search for the optimal for fixed P and t. The optimal t is approximately a factor of 1.1 smaller than for the TCI policy. The rates are shown in Figure 12 as the curve labeled “TMMSE, GMI”.

Figure 12.

Rates for Rayleigh fading with full CSIT and .

8.5. Partial CSIR, CSIT@ R

Suppose is defined by (see (172))

where and are independent with distribution . We further consider the CSIT .

The reverse model GMI again requires , which can be computed by simulation; see Appendix C.4. However, as in Section 7.4 and Section 8.3, optimizing the powers seems difficult, and we instead focus on forward models. The expressions (235) and (236) are

The GMI (237) of Theorem 3 is

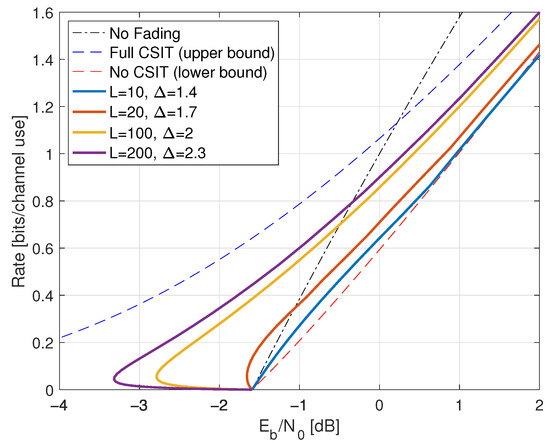

where the power control policy is given by (245). The parameter is chosen so that . For example, for we recover the waterfilling solution (181). Figure 13 shows the quadratic and conventional waterfilling rates, which lie almost on top of each other. For example, the inset shows the rates for and a small range of .

Figure 13.

Rates for Rayleigh fading with partial CSIR and CSIT@R. The curves labeled ‘q-waterfill’ and ‘c-waterfill’ are the quadratic and conventional waterfilling rates, respectively.

9. Channels with In-Block Feedback

This section generalizes Shannon’s model described in Section 4.1 to include block fading with in-block feedback. For example, the model lets one include delay in the CSIT and permits many other generalizations for network models [22].

9.1. Model and Capacity

The problem is specified by the FDG in Figure 14. The model has a message M, and the channel input and output strings

for blocks . The channel is specified by a string of i.i.d. hidden channel states. The CSIR is a (possibly noisy) function of for all i and ℓ. The receiver sees the channel outputs (see (159))

for some functions , . Observe that the influence the in a causal fashion. The random variables are mutually independent.

Figure 14.

FDG for a block fading model with blocks of length and in-block feedback. Across-block dependence via past is not shown.

We now permit past channel symbols to influence the CSIT; see Section 1.2. Suppose the CSIT has the form

for some function and for all i and ℓ. The motivation for (321) is that useful CSIR may not be available until the end of a block or even much later. In the meantime, the receiver can, e.g., quantize the and transmit the quantization bits via feedback. This lets one study fast power control and beamforming without precise knowledge of the channel coefficients.

Define the string of past and current states as

The channel input at time is and the adaptive codeword is defined by the ordered lists

for and . The adaptive codeword is a function of M and is thus independent of and .

The model under consideration is a special case of the channels introduced in ([22], Section V). However, the model in [22] has transmission and reception begin at time rather than . To compare the theory, one must thus shift the time indexes by 1 unit and increase L to . The capacity for our model is given by ([22], Theorem 2) which we write as

where follows by normalizing by L rather than , and step follows by the independence of and .

9.2. GMI for Scalar Channels

We will study scalar block fading channels; extensions to vector channels follow as described in Section 4.4. Let be the vector form of and similarly for other strings with L symbols. The GMI with parameter s is

Reverse Model: For the reverse model, let be a column vector that stacks the for all and ℓ. Consider a reverse density as in (105):

where

Using the forward model , the GMI with becomes

To simplify, consider adaptive symbols as in (89) (cf. (107)):

where . In other words, consider a conventional codebook represented by the and adapt the power and phase based on the available CSIT. The mutual information becomes (cf. (96)) and the GMI with is (cf. (108))

In fact, one may also consider choosing for all ℓ in which case we compute (cf. (139))

Forward Model: Consider the following forward model (cf. (111) and (141)):

with

and where similar to (142) we define

where the are complex matrices. Note that

so is a function of and , .

We have the following generalization of Lemma 4 (see also Theorem 1) where the novelty is that is replaced with . Define and for all .

Theorem 4.

A GMI (325) for the scalar block fading channel , an adaptive codeword with jointly CSCG entries, the auxiliary model (330), and with fixed is

where

and for unitary the matrix is

and and are unitary and rectangular diagonal matrices, respectively, of the SVD

for all , and the are unitary matrices. One may maximize (333) over the unitary .

9.3. CSIT@ R

Continuing as in Section 5.2, suppose the CSIT in (321) can be written by replacing with for all i and ℓ:

The capacity (324) then simplifies to a directed information. To see this, expand the mutual information in (324) as

where step follows because is a function of and in (338), and step follows by the Markov chains

The capacity is therefore (see the definition (27))

The maximization in (341) under a cost constraint becomes a constrained maximization for which for some cost function .

Remark 75.

As outlined at the end of Section 9.1, the capacity (341) is a special case of the theory in ([22], Equation (48)). To see this, define the extended and time-shifted strings

Since and are independent, one may expand (339) as

where step follows because is a function of and in (338), and where , and step follows by the Markov chains

The expression (342) is the desired directed information

Remark 76.

Consider the basic CSIT model

for some function and for and . This model was studied in ([103], Section III.C) and its capacity is given as (see ([103], Equation (35) with Equation (13)))

To see that (346) is a special case of (341), observe that

where step follows by (339), and step follows by the Markov chains

The expression (347) gives (346). Related results are available in ([10], Section III) and [104,105].

Remark 77.