Abstract

We present a simple method to approximate the Fisher–Rao distance between multivariate normal distributions based on discretizing curves joining normal distributions and approximating the Fisher–Rao distances between successive nearby normal distributions on the curves by the square roots of their Jeffreys divergences. We consider experimentally the linear interpolation curves in the ordinary, natural, and expectation parameterizations of the normal distributions, and compare these curves with a curve derived from the Calvo and Oller’s isometric embedding of the Fisher–Rao d-variate normal manifold into the cone of symmetric positive–definite matrices. We report on our experiments and assess the quality of our approximation technique by comparing the numerical approximations with both lower and upper bounds. Finally, we present several information–geometric properties of Calvo and Oller’s isometric embedding.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Fisher–Rao Normal Manifold

Let be the set of symmetric matrices with real entries and denote the set of symmetric positive–definite matrices that forms a convex regular cone. Let us denote by the set of d-variate normal distributions, MultiVariate Normals or MVNs for short, also called Gaussian distributions. A MVN distribution has probability density function (pdf) on the support :

where denotes the determinant of matrix M.

The statistical model is of dimension since it is identifiable, i.e., there is a one-to-one correspondence between and . The statistical model is said to be regular since the second-order derivatives and third-order derivatives are smooth functions (defining the metric and cubic tensors in information geometry [1]), and the set of first-order partial derivatives are linearly independent.

Let denote the covariance of X (variance when X is scalar). A matrix M is a semi-positive–definite if and only if . The Fisher information matrix [1,2] (FIM) is the following symmetric semi-positive–definite matrix:

For regular statistical models , the FIM is positive–definite: , i.e., . denotes Löwner partial ordering, i.e., the fact that is positive–definite.

The FIM is covariant under the reparameterization of the statistical model [2]. That is, let be a new parameterization of the MVNs. Then we have:

For example, we may parameterize univariate normal distributions by or . We obtain the following Fisher information matrices for these parameterizations:

In higher dimensions, parameterization corresponds to the parameterization while parameterization where is the unique Cholesky decomposition with , the group of invertible matrices. Another useful parameterization for optimization is the log–Cholesky parameterization [3] ( for univariate normal distributions) which ensures that a gradient descent always stays in the domain. The Fisher information matrix with respect to the log–Cholesky parameterization is with .

Since the statistical model is identifiable and regular, the Fisher information matrix can be written equivalently as follows [2,4]:

For multivariate distributions parameterized by a m-dimensional vector (with )

with and (inverse half-vectorization of matrices [5]), we have [6,7,8,9]:

By equipping the regular statistical model with the Fisher information metric

we obtain a Riemannian manifold called the Fisher–Rao Gaussian or normal manifold [6,7]. The tangent space is identified with the product space . Let be a natural vector basis in , and denote by and the vector components in that natural basis. We have

The induced Riemannian geodesic distance is called the Rao distance [10] or the Fisher–Rao distance [11,12]:

where the Riemannian length of any smooth curve is defined by

where denotes the derivative with respect to parameter t, is the Riemannian length element of and . We also write for .

The minimizing curve of Equation (3) is called the Fisher–Rao geodesic. The Fisher–Rao geodesic is also an autoparallel curve [2] with respect to the Levi–Civita connection induced by the Fisher metric .

Remark 1.

If we consider the Riemannian manifold for instead of then the length element is scaled by : . It follows that the length of a curve c becomes

However, the geodesics joining any two points and of are the same: (with and ).

Historically, Hotelling [13] first used this Fisher Riemannian geodesic distance in the late 1920s. From the viewpoint of information geometry [1], the Fisher metric is the unique Markov invariant metric up to rescaling [14,15,16]. The counterpart to the Fisher metric on the compact manifold has been reported in [17], proving its uniqueness under the action of the diffeomorphism group. The Fisher–Rao distance has been used to design statistical hypothesis testing [18,19,20,21], to measure the distance between the prior and posterior distributions in Bayesian statistics [22], in clustering [23,24], in signal processing [25,26,27,28], and in deep learning [29], just to mention a few.

The squared line element induced by the Fisher metric of the multivariate normal family [6,7] is

There are many ways to calculate the FIM/length element for multivariate normal distributions [7,9]. Let us give a simple approach based on the fact that the family of normal distributions forms a regular exponential family [30]:

with the natural parameters and log-partition function (also called cumulant function)

The vector inner product is , and the matrix inner product is . The exponential family is said to be regular when the natural parameter space is open. Using Equation (2), it follows that the MVN FIM is . This proves that the FIM is well-defined, i.e., . As an exponential family [1], we also have , where is the sufficient statistic. Thus, the Fisher metric is a Hessian metric [31]. Let with and . We obtain the following block-diagonal expression of the FIM:

Therefore with and . Let us note in passing that is a fourth order tensor [4].

The family can also be considered to be an elliptical family [32], thus highlighting the affine-invariance property of the Fisher information metric. That is, the Fisher metric is invariant with respect to affine transformations [33]: Let be an element of the affine group with and . The group identity element of is and the group operation is with inverse ). Then we have

Property 1

(Fisher–Rao affine invariance). For all , we have

This can be proven by checking that where and . It follows that we can reduce the calculation of the Fisher–Rao distance to a canonical case where one argument is , the standard d-variate distribution:

where is the fractional matrix power which can be calculated from the Singular Value Decomposition of (where O is an orthogonal matrix and a diagonal matrix): with .

The family of normal elliptical distributions can be obtained from the standard normal distribution by the action of the affine group [12,32] :

1.2. Fisher–Rao Distance between Normal Distributions: Some Subfamilies with Closed-Form Formula

In general, the Fisher–Rao distance between two multivariate normal distributions and is not known in closed form [34,35,36,37], and several lower and upper bounds [38], and numerical techniques such as the geodesic shooting [39,40,41] have been investigated. See [42] for a recent review. Unfortunately, the geodesic shooting (GS) approach is time-consuming and numerically unstable for large Fisher–Rao distances [21,42]. In 3D Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI), covariance matrices are stored a 3D grid locations thus generating 3D MVNs with means regularly spaced to each others. The Fisher–Rao distances can be calculated between an MVN and another MVN in a neighborhood of (using 6- or 26-neighborhood) using geodesic shooting. For larger Fisher–Rao distances between non-neighbors MVNs, we can use the shortest path distance using Dijkstra’s algorithm [43] on the graph induced by the MVNs with edges between adjacent MVNs weighted by their Fisher–Rao distances.

The two main difficulties with calculating the Fisher–Rao distance are

- to know explicitly the expression of the Riemannian Fisher–Rao geodesic and

- to integrate, in closed form, the length element along this Riemannian geodesic.

Please note that the Fisher–Rao geodesics [1] are parameterized by constant speed (i.e., and ), or equivalently parametrized using the arc length:

However, in several special cases, the Fisher–Rao distance between normal distributions belonging to restricted subsets of is known.

Three such prominent cases are (see [42] for other cases)

- when the normal distributions are univariate (),

- when we consider the set of normal distributions sharing the same mean (with the embedded submanifold ), and

- when we consider the set of normal distributions sharing the same covariance matrix (with the corresponding embedded submanifold ).

Let us report the formula of the Fisher–Rao distance in these three cases:

- In the univariate case , the Fisher–Rao distance between and can be derived from the hyperbolic distance [44] expressed in the Poincaré upper space since we havewhere and . It follows thatThus, we have the following expression for the Fisher–Rao distance between univariate normal distributions:withIn particular, we have

- –

- when (same mean),

- –

- when (same variance),

- –

- when and (standard normal).

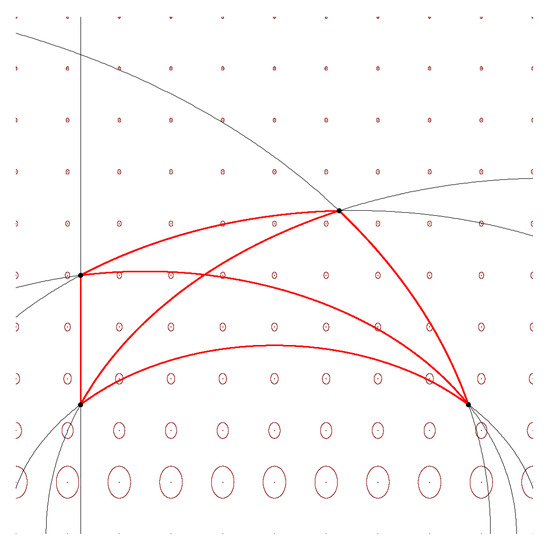

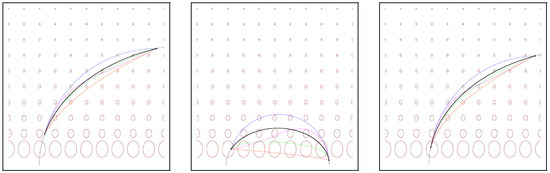

In 1D, the affine-invariance property (Property 1) extends to function as follows:Using one of the many identities between inverse hyperbolic functions (e.g., arctanh, arccosh, arcsinh), we can obtain an equivalent formula for Equation (7). For example, since for , we have equivalently:The Fisher–Rao geodesics are semi-ellipses with centers located on the x-axis. See Appendix A.1 for the parametric equations of Fisher–Rao geodesics between univariate normal distributions. Figure 1 displays four univariate normal distributions with their pairwise geodesics and Fisher–Rao distances. Figure 1. Four univariate normal distributions , , , , and their pairwise full geodesics in gray and geodesics linking them in red. The Fisher–Rao distances are , , , , and The ellipses are Tissot indicatrices, which visualize the metric tensor at grid positions.Using the identity with , we also haveSince the inverse hyperbolic cosecant (CSC) function is defined by , we further obtainWe can also writeThus, using the many-conversions formula between inverse hyperbolic functions, we obtain many equivalent different formulas of the Fisher–Rao distance, which are used in the literature.

Figure 1. Four univariate normal distributions , , , , and their pairwise full geodesics in gray and geodesics linking them in red. The Fisher–Rao distances are , , , , and The ellipses are Tissot indicatrices, which visualize the metric tensor at grid positions.Using the identity with , we also haveSince the inverse hyperbolic cosecant (CSC) function is defined by , we further obtainWe can also writeThus, using the many-conversions formula between inverse hyperbolic functions, we obtain many equivalent different formulas of the Fisher–Rao distance, which are used in the literature. - In the second case, the Fisher–Rao distance between and has been reported in [6,7,45,46,47]:where denotes the i-th generalized largest eigenvalue of matrix M, where the generalized eigenvalues are solutions of the equation . Let us notice that since and . Matrix may not be SPD and thus the ’s are generalized eigenvalues. We may consider instead the SPD matrix which is SPD and such that . The Fisher–Rao distance of Equation (11) can be equivalently written [48] aswhere is the matrix logarithm (unique when M is SPD) and is the matrix Fröbenius norm. This metric distance between SPD matrices although first studied by Siegel [45] in 1964 was rediscovered and analyzed recently in [49] (2003). Let so that .The Riemannian SPD distance enjoys the following well-known invariance properties:

- –

- Invariance by congruence transformation:

- –

- Invariance by inversion:Let be the Cholesky decomposition (unique when ). Then apply the congruence invariance for :We can also consider the factorization where is the unique symmetric square root matrix [50]. Then we have

- The Fisher–Rao distance between and has been reported in closed form [42] (Proposition 3). The method is described with full details in Appendix B. We present a simpler scheme based on the inverse of the symmetric square root factorization [50] of (ith ). Let us use the affine-invariance property of the Fisher–Rao distance under the affine transformation and then apply affine invariance under translation as follows:The right-hand side Fisher–Rao distance is computed from Equation (7) and justified by the method [42] (Proposition 3) described in Appendix B using a rotation matrix R with so thatThen we apply the formula of Equation (23) of [42]. Section 1.5 shall report a simpler closed-form formula by proving that the Fisher–Rao distance between and is a scalar function of their Mahalanobis distance [51] using the algebraic method of maximal invariants [52].

1.3. Fisher–Rao Distance: Totally versus Non-Totally Geodesic Submanifolds

Consider a statistical submodel of the MVN statistical model . Using the Fisher information matrix , we obtain the intrinsic Fisher–Rao manifold . We may also consider to be an embedded submanifold of . Let us write the embedded submanifold.

A totally geodesic submanifold is such that the geodesics fully stay in for any pair of points . For example, the submanifold of MVNs with fixed mean is a totally geodesic submanifold [53] of but the submanifold of MVNs sharing the same covariance matrix is not totally geodesic. When an embedded submanifold is totally geodesic, we always have . Thus, we have . However, when an embedded submanifold is not totally geodesic, we have because the Riemannian geodesic length in is necessarily longer or equal than the Riemannian geodesic length in . The merit to consider submanifolds is to be able to calculate in closed form the Fisher–Rao distance which may then provide an upper bound on the Fisher–Rao distance for the full statistical model. For example, consider and in , a non-totally geodesic submanifold. The Rao distance between and in is upper bounded by the Riemannian distance in (with line element ) which corresponds to the Mahalanobis distance [10,51]:

The Mahalanobis distance can be interpreted as the Euclidean distance (where I denotes the identity matrix) after an affine transformation: Let be the Cholesky decomposition of with L a lower triangular matrix or an upper triangular matrix. Then we have

where denotes the vector -norm.

The Rao distance of Equation (A1) between two MVNs with fixed covariance matrix emanates from the property that the submanifold is totally geodesic [54].

Let us emphasize that for a submanifold to be totally geodesic or not depend on the underlying metric in . The same subset with equipped with two different metrics and can be totally geodesic regarding and non-totally geodesic regarding . See Remark 3 for such an example.

In general, using the triangle inequality of the Riemannian metric distance , we can upper bound with and as follows:

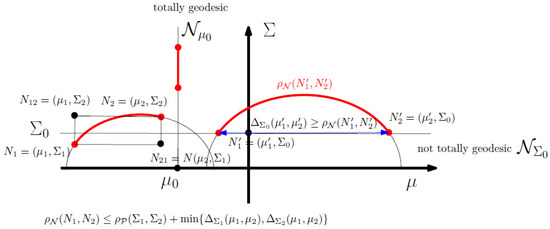

where and . See Figure 2 for an illustration of the Fisher–Rao geodesic triangle . Furthermore, since and , we obtain the following upper bound on the Rao distance between MVNs:

See also [55].

Figure 2.

The submanifolds are not totally geodesic (i.e., is upper bounded by their Mahalanobis distance) but the submanifolds are totally geodesic. Using the triangle inequality of the Riemannian metric distance , we can upper bound .

In general, the difficulty with calculating the Fisher–Rao distance comes from the fact that

- we do not know the Fisher–Rao geodesics with boundary value conditions (BVP) in closed form but the geodesics with initial value conditions [48] (IVP) are known explicitly using the natural parameters of MVNs,

- we must integrate the line element along the geodesic.

As we shall see in Section 3.1, the above first problem is much harder to solve than the second problem which can be easily approximated by discretizing the curve. The lack of a closed-form formula and fast and good approximations for between MVNs is a current limiting factor for its use in applications. Indeed, many applications (e.g., [56,57]) consider the restricted case of the Rao distance between zero-centered MVNs which have closed form (distance of Equation (11) in the SPD cone). The SPD cone is a symmetric Hadamard manifold, and its isometries have been fully studied and classified in [58] (Section 4). The Fisher–Rao geometry of zero-centered generalized MVNs was recently studied in [59].

1.4. Contributions and Paper Outline

The main contribution of this paper is to propose an approximation of based on Calvo and Oller’s embedding [19] (C&O for short) and report its experimental performance. First, we concisely recall C&O’s family of embeddings of as submanifolds of in Section 2. Next, we present our approximation technique in Section 3 which differs from the usual geodesic shooting approach [39], and report experimental results. Finally, we study some information–geometric properties [1] of the isometric embedding in Section 5 such as the fact that it preserves mixture geodesics (embedded C&O submanifold is autoparallel with respect to the mixture affine connection) but not exponential geodesics. Moreover, we prove that the Fisher–Rao distance between multivariate normal distributions sharing the same covariance matrix is a scalar function of their Mahalanobis distance in Section 1.5 using the framework of Eaton [52] of maximal invariants.

1.5. A Closed-Form Formula for the Fisher–Rao Distance between Normal Distributions Sharing the Same Covariance Matrix

Consider the Fisher–Rao distance between and for a fixed covariance matrix and the translation action of the translation group (a subgroup of the affine group). Both the Fisher–Rao distance and the Mahalanobis distance are invariant under translations:

To prove that for a scalar function , we shall prove that the Mahalanobis distance is a maximal invariant, and use the framework of maximal invariants of Eaton [52] (Chapter 2) who proved that any other invariant function is necessarily a function of a maximal invariant, i.e., a function of the Mahalanobis distance in our case.

The Mahalanobis distance is a maximal invariant because we can write and when in 1D there exists such that . We must prove equivalently that when that there exists such that . Assume without loss of generality that . When , there exists so that and with . Thus, using Eaton’s theorem [52], there exists a scalar function such that .

To find explicitly the scalar function , let us consider the univariate case of normal distributions for which the Fisher–Rao distance is given in closed form in Equation (7). In that case, the univariate Mahalanobis distance is and we can write formula of Equation (7) as with

using the identities

where .

Proposition 1.

The Fisher–Rao distance between two MVNs with same covariance matrix is

where is the Mahalanobis distance.

Indeed, notice that the d-variate Mahalanobis distance can be interpreted as a univariate Mahalanobis distance between the standard normal distribution and :

Thus, we have , where the right-hand-side term is the univariate Fisher–Rao distance of Equation (7). Let us notice that the square length element on is . This result can be extended to elliptical distributions [12] (Theorem 1).

Let us corroborate this result by checking the formula of Equation (1) with two examples in the literature: In [38] (Figure 4), we Fisher–Rao distance between and is studied. We find in accordance with their result shown in Figure 4. The second example is Example 1 of [42] (p. 11) with and for . Formula of Equation (18) yields the Fisher–Rao distance in accordance with [42] which reports .

Similarly, the statistical Ali–Silvey–Csiszár f-divergences [60,61]

between two MVNs sharing the same covariance matrix are increasing functions of the Mahalanobis distance because the f-divergences between two MVNs sharing the same covariance matrix are invariant under the action of the translation group [62]. Thus, we have . Since , we thus have

where the right-hand side f-divergence is between univariate normal distributions. See Table 2 of [62] for some explicit functions .

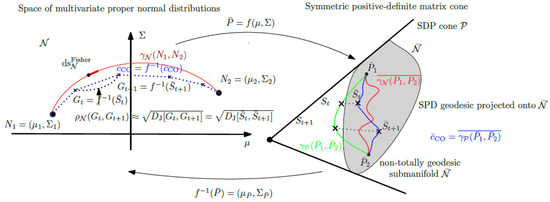

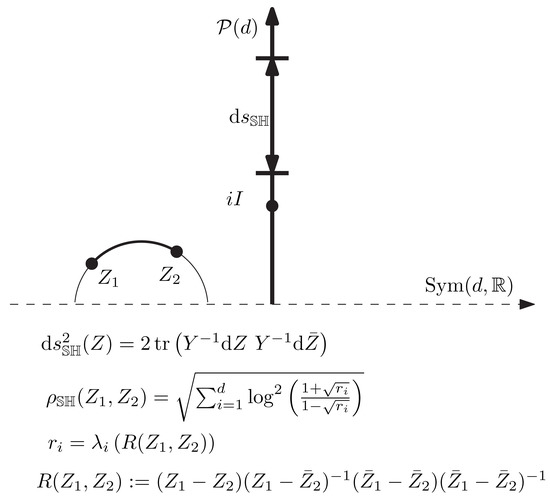

2. Calvo and Oller’s Family of Diffeomorphic Embeddings

Calvo and Oller [19,32] noticed that we can embed the space of normal distributions in by using the following mapping:

where and . Notice that since the dimension of is , we only use extra dimension for embedding into . By foliating where denotes the subsets of with determinant c, we obtain the following Riemannian Calvo and Oller metric on the SPD cone:

Let

denote the submanifold of of codimension 1, and (i.e., ). The family of mappings provides diffeomorphisms between and . Let denote the inverse mapping for , and let (i.e., ):

By equipping the cone by the trace metric [63,64] (also called the affine invariant Riemannian metric, AIRM) scaled by :

(yielding the squared line element ), Calvo and Oller [19] proved that is isometric to (i.e., the Riemannian metric of restricted to coincides with the Riemannian metric of induced by f) but is not totally geodesic (i.e., the geodesics for leaves the embedded normal submanifold . Please note that can be interpreted as the Fisher metric for the family of 0-centered normal distributions. Thus, we have , and the following diagram between parameter spaces and corresponding distributions:

Remark 2.

The trace metric was first studied by Siegel [45,65] using the wider scope of complex symmetric matrices with positive–definite imaginary parts generalizing the Poincaré upper half-plane (see Appendix D).

We omit to specify the dimensions and write for short , , and when clear from the context. Thus, C&O proposed to use the embedding to give a lower bound of the Fisher–Rao distance between normals:

We let . The distance is invariant under affine transformations such as the Fisher–Rao distance of Property 1:

Property 2

(affine invariance of C&O distance [19]). For all , we have .

When , we have . Since the Riemannian geodesics in the SPD cone are given by [66] (also written ), we have . Although the submanifold is totally geodesic with respect to the trace metric, it is not totally geodesic with respect to . Thus, although , it does not correspond to the embedded MVN geodesics with respect to the Fisher metric. The C&O distance between two MVNs and sharing the same covariance matrix [19] is

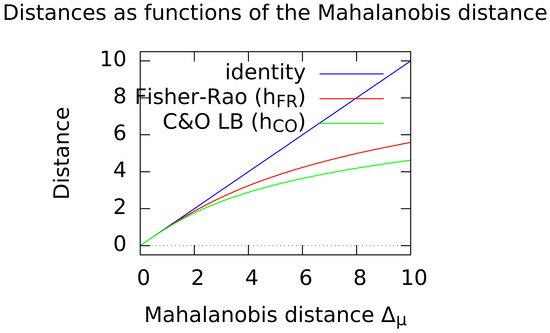

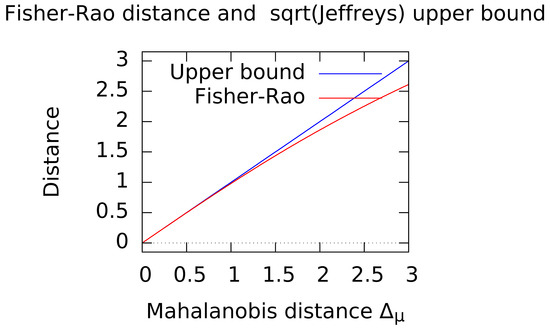

where for and is the Mahalanobis distance between and . In that case, we thus have where is a strictly monotone increasing function. Let us note in passing that in [19] (Corollary, page 230) there is a confusing or typographic error since the distance is reported as where denotes “Mahalanobis distance” [51]. Therefore, either , Mahalanobis -distance, or there is a missing square in the equation of the Corollary page 230. To obtain a flavor of how good is the approximation of the C&O distance, we may consider the same covariance case where we have both closed-form solutions for (Equation (20)) and (Equation (23)). Figure 3 plots the two functions and (with for ).

Figure 3.

Quality of the C&O lower bound compared to the exact Fisher–Rao distance in the case of (MVNs sharing the same covariance matrix ). We have .

Let us remark that similarly all f-divergences between and are scalar functions of their Mahalanobis distance too, see [62].

The C&O distance is a metric distance that has been used in many applications ranging from computer vision [57,67,68,69] to signal/sensor processing, statistics [70,71], machine learning [29,72,73,74,75,76] and analogical reasoning [77].

Remark 3.

In a second paper, Calvo and Oller [32] noticed that we can embed normal distributions in by the following more general mapping (Lemma 3.1 [32]):

where , and . It is show in [32] that the induced length element is

When , we have

Thus, to cancel the term , we may either choose or .

In some applications [78], the embedding

is used to ensure that . That is normal distributions are embedded diffeomorphically into the submanifold of positive–definite matrices with a unit determinant (also called SSPD, acronym of Special SPD). In [32], C&O showed that there exists a second isometric embedding of the Fisher–Rao Gaussian manifold into a submanifold of the cone : . Let . This mapping can be understood as taking the elliptic isometry of [64] since (see proof in Proposition 3). It follows that

Similarly, we could have mapped to obtain another isometric embedding. See the four types of elliptic isometric of the SPD cone described in [64]. Finally, let us remark that the SSPD submanifold is totally geodesic with respect to the trace metric but not with respect to the C&O metric.

Interestingly, Calvo and Oller [48] (p. 131) proved that is a maximal invariant for the action of the affine group , where and (in [48], the authors considered ). Thus, we consider the following dissimilarity

Dissimilarity is symmetric (i.e., ) and if and only if . Please note that when , is different from the Fisher–Rao distance of Equation (7).

3. Approximating the Fisher–Rao Distance

3.1. Approximating Length of Curves

Recall that the Fisher–Rao’s distance [79] is the Riemannian geodesic distance

where

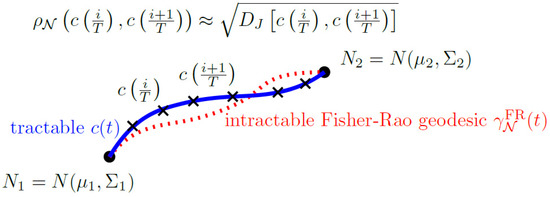

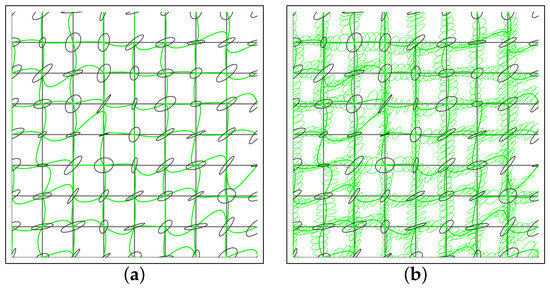

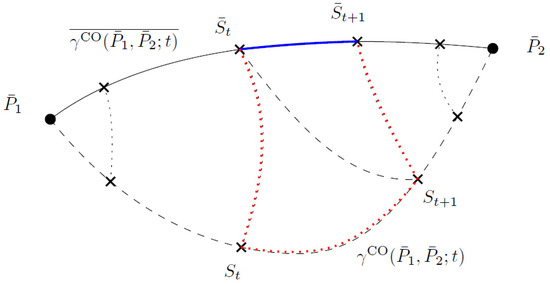

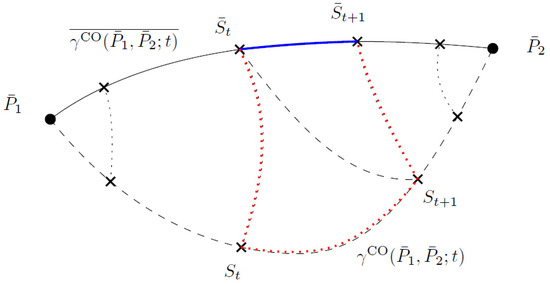

We can approximate the Rao distance by discretizing regularly any smooth curve joining to (Figure 4):

with equality holding iff is the Riemannian geodesic defined by the Levi–Civita metric connection induced by the Fisher information metric.

Figure 4.

Approximating the Fisher–Rao geodesic distance : The Fisher–Rao geodesic is not known in closed form. We consider a tractable curve , discretize at points with and , and approximate by , considering that different tractable curves yield different approximations.

When the number of discretization steps T is sufficiently large, the normal distributions and are close to each other, and we can approximate by , where is Jeffreys divergence, and is the Kullback–Leibler divergence:

Thus, the costly determinant computations cancel each other in Jeffreys divergence (i.e., ) and we have:

Figure 4 summarizes our method to approximate the Fisher–Rao geodesic distance.

In general, it holds that

between infinitesimally close distributions p and q (), where denotes a f-divergence [1]. The Jeffreys divergence is a f-divergence obtained for with . It is thus interesting to find low computational cost f-divergences between multivariate normal distributions to approximate the infinitesimal length element . Please note that f-divergences between MVNs are also invariant under the action of the affine group [62]. Thus, for infinitesimally close distributions p and q, this informally explains that is invariant under the action of the affine group (see Proposition 1).

Although the definite integral of the length element along the Fisher–Rao geodesic is not known in closed form (i.e., Fisher–Rao distance), the integral of the squared length element along the mixture geodesic and exponential geodesic coincide with Jeffreys divergence between and [1]:

Property 3

([1]). We have

Proof.

Let us report a proof of this remarkable fact in the general setting of Bregman manifolds. Indeed, since

and , where denotes the Bregman divergence induced by the cumulant function of the multivariate normals and is the natural parameter corresponding to , we have

where and denote the dual parameterizations obtained by the Legendre–Fenchel convex conjugate of . Moreover, we have [1], i.e., the convex conjugate function is Shannon negentropy.

Then we conclude using the fact that , i.e., the symmetrized Bregman divergence amounts to integral energies on dual geodesics on a Bregman manifold. The proof of this general property is reported in Appendix E. □

It follows the following upper bound on the Fisher–Rao distance:

Property 4

(Fisher–Rao upper bound). The Fisher–Rao distance between normal distributions is upper bounded by the square root of the Jeffreys divergence: .

Proof.

Consider the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality for positive functions and : ), and let and . Then we obtain:

Furthermore, since by definition of , we have

It follows for (i.e., e-geodesic) using Property 3 that we have:

Thus, we conclude that .

Please note that in Riemannian geometry, a curve minimizes the energy if it minimizes the length and is constant. Using Cauchy-Schwartz inequality, we can show that . □

This upper bound is tight at infinitesimal scale (i.e., when ) since and the f-divergence in right-hand side of the identity can be chosen as Jeffreys divergence. To appreciate the quality of the square root of Jeffreys divergence upper bound of Property 4, consider the case where . In that case, we have and (since ). The upper bound can thus be checked since we have for . The plots of Figure 5 shows visually the quality of the upper bound.

Figure 5.

Quality of the upper bound on the Fisher–Rao distance when normal distributions have the same covariance matrix.

For any smooth curve , we can thus approximate for large T by

For example, we may consider the following curves on which admit closed-form parameterizations in :

- linear interpolation (LERP, Linear intERPolation) between and ,

- the mixture geodesic [80] with and where and ,

- the exponential geodesic [80] with and where is the matrix harmonic mean,

- the curve which is obtained by averaging the mixture geodesic with the exponential geodesic.

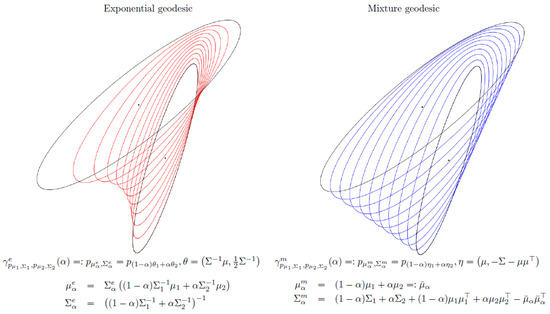

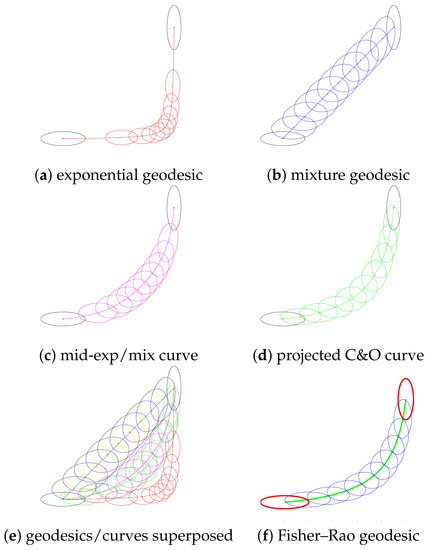

Figure 6 visualizes the exponential and mixture geodesics between two bivariate normal distributions.

Figure 6.

Visualizing the exponential and mixture geodesics between two bivariate normal distributions.

Let us denote by , , and the approximations obtained by these curves following from Equation (27). When T is sufficiently large, the approximated distances are close to the length of curve x, and we may thus consider a set of several curves and report the smallest Fisher–Rao distance approximations obtained among these curves: .

Please note that we consider the regular spacing for approximating a curve length and do not optimize the position of the sample points on the curve. Indeed, as , the curve length approximation tends to the Riemannian curve length. In other words, we can measure approximately finely the length of any curve available with closed-form reparameterization by increasing T. Thus, the key question of our method is how to best approximate the Fisher–Rao geodesic by a curve that can be parametrized by a closed-form formula and is close enough to the Fisher–Rao geodesic.

Next, we introduce our approximation curve derived from Calvo and Oller isometric mapping f which experimentally behaves better when normals are not too far from each other.

3.2. A Curve Derived from Calvo and Oller’s Embedding

This approximation consists of leveraging the closed-form expression of the SPD geodesics [63,66]:

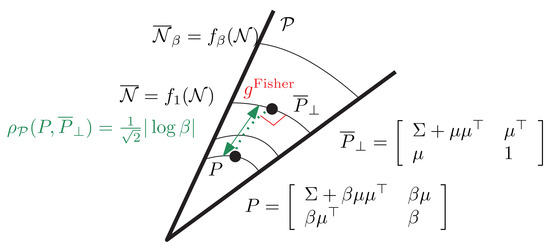

to approximate the Fisher–Rao normal geodesic as follows: Let , and consider the smooth curve

where denotes the orthogonal projection of onto (Figure 7). Thus, curve () is then defined by taking the inverse mapping (Figure 8):

Figure 7.

Projecting an SPD matrix onto : is orthogonal to with respect to the trace metric.

Figure 8.

Illustration of the approximation of the Fisher–Rao distance between two multivariate normals and (red geodesic length by discretizing curve or equivalently curve .

Please note that the matrix power can be computed as where is the eigenvalue decomposition of P.

Let us now explain how to project onto based on the analysis of the Appendix of [19] (p. 239):

Proposition 2

(Projection of an SPD matrix onto the embedded normal submanifold ). Let and write . Then the orthogonal projection at onto is:

and the SPD distance between P and is

Notice that the projection of P is easily computed since .

Remark 4.

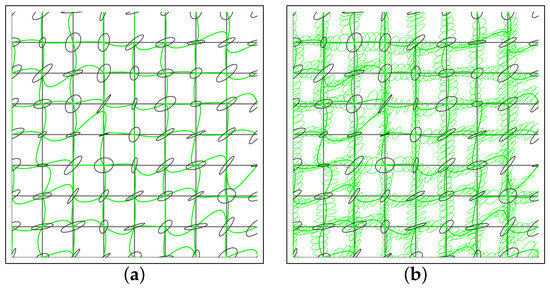

In Diffusion Tensor Imaging [39] (DTI), the Fisher–Rao distance can be used to evaluate the distance between three-dimensional normal distributions with means located at a 3D grid position. We may consider neighbor graphs induced by the grid, and for each normal N of the grid, calculate the approximations of the Fisher–Rao distance of N with its neighbors as depicted in Figure 9. Then the distance between two tensors and of the 3D grid is calculated as the shortest path on the weighted graph using Dijkstra’s algorithm [39].

Figure 9.

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) on a 2D grid: (a) Ellipsoids shown at the grid locations with C&O curves in green, and (b) some interpolated ellipsoids are further shown along the C&O curves.

Please note that the Fisher–Rao projection of onto a submanifold with fixed mean was recently reported in closed form in [72] (Equation (21)):

with

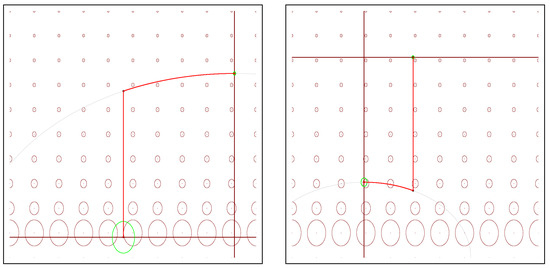

and the Fisher–Rao projection of onto submanifold is the “vertical projection” (Figure 10) with

Figure 10.

Examples of projection of onto the submanifolds and . Tissot indicatrices are rendered in green at the projected normal distributions and , respectively.

We can upper bound the Fisher–Rao distance by projecting onto and projecting onto . Let and denote those Fisher–Rao orthogonal projections. Using the triangular inequality property of the Fisher–Rao distance, we obtain the following upper bounds:

See Figure 11 for an illustration.

Figure 11.

Upper bounding the Fisher–Rao’s distance (red points) using projections (green points) onto submanifolds with fixed means.

Let and . The following proposition shows that we have .

Proposition 3.

The Kullback–Leibler divergence between and amounts to the KLD between and where :

The KLD between two centered -variate normals and is

This divergence can be interpreted as the matrix version of the Itakura–Saito divergence [81]. The SPD cone equipped with of the trace metric can be interpreted as Fisher–Rao centered normal manifolds: .

Since the determinant of a block matrix is

we obtain with : .

Let and . Checking where amounts to verify that

Indeed, using the inverse matrix

we have

Thus, even if the dimension of the sample spaces of and differs by one, we obtain the same KLD by Calvo and Oller’s isometric mapping f.

This property holds for the KLD/Jeffreys divergence but not for all f-divergences [1] in general (e.g., it fails for the Hellinger divergence).

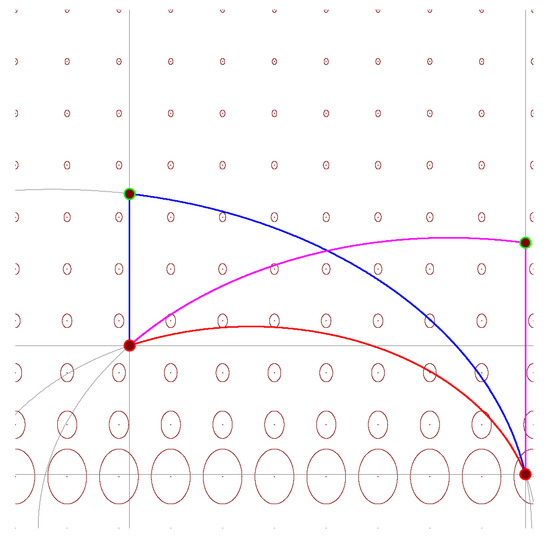

Figure 12 shows the various geodesics and curves used to approximate the Fisher–Rao distance with the Fisher metric shown using Tissot indicatrices.

Figure 12.

Geodesics and curves used to approximate the Fisher–Rao distance with the Fisher metric shown using Tissot’s indicatrices: exponential geodesic (red), mixture geodesic (blue), mid-exponential-mixture curve (purple), projected CO curve (green), and target Fisher–Rao geodesic (black). (Visualization in the parameter space of normal distributions).

Please note that the introduction of parameter is related to the foliation of the SPD cone by : . See Figure 7. Thus, we may define how good the projected C&O curve is to the Fisher–Rao geodesic by measuring the average distance between points on and their projections onto :

In practice, we evaluate this integral at the sampling points :

where and . We checked experimentally (see Section 3.3) that for close by normals and , we have small, and that when becomes further separated from , the average projection error increases. Thus, is a good measure of the precision of our Fisher–Rao distance approximation.

Lemma 1.

We have .

Proof.

The proof consists of applying twice the triangle inequality of metric distance :

See Figure 13 where the left-hand-side geodesic length is shown in blue and the right-hand-side upper bound is visualized in red. □

Figure 13.

Bounding using the triangular inequality of in the SPD cone .

Property 5.

We have .

Proof.

At infinitesimal scale when , using Lemma 1 and we have

Taking the integral along the curve , we obtain

Since , we have

□

Notice that .

Example 1.

Let us consider Example 1 of [42] (p. 11):

The Fisher–Rao distance is evaluated numerically in [42] as . We have the lower bound , and the Mahalanobis distance upper bounds the Fisher–Rao distance (not totally geodesic submanifold ). Our projected C&O curve discretized with yields an approximation . The average projection distance is , and the maximum projected distance is . We check that

The Killing distance [82] obtained for is (see Appendix C). Notice that geodesic shooting is time-consuming compared to our approximation technique.

3.3. Some Experiments

The KLD and Jeffreys divergence , the Fisher–Rao distance and the Calvo and Oller distance are all invariant under the congruence action of the affine group with the group operation

Let , and define the action on the normal space as follows:

Then we have:

This invariance extends to our approximations (see Equation (27)).

Since we have

the ratio gives an upper bound on the approximation factor of compared to the true Fisher–Rao distance :

Let us now report some numerical experiments of our approximated Fisher–Rao distances with . Although that dissimilarity is positive–definite, it does not satisfy the triangular inequality of metric distances (e.g., Riemannian distances and ).

First, we draw multivariate normals by sampling means and sample covariance matrices as follows: We draw a lower triangular matrix L with entries iid sampled from , and take . We use samples on curves and repeat the experiment 1000 times to gather average statistics on ’s of curves. Results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

First set of experiments demonstrates the advantage of the curve.

For that scenario that the C&O curve (either or ) performs best compared to the linear interpolation curves with respect to source parameter (l), mixture geodesic (m), exponential geodesic (e), or exponential-mixture mid-curve (). Let us point out that we sample for .

Strapasson, Porto, and Costa [38] (SPC)reported the following upper bound on the Fisher–Rao distance between multivariate normals

with:

where , is the eigen decomposition, and . This upper bound performs better when the normals are well-separated and worse than the -upper bound when the normals are close to each other.

Let us compare with and the upper bound by averaging over 1000 trials with and chosen randomly as before and . We have . Table 2 shows that our Fisher–Rao approximation is close to the lower bound (and hence to the underlying true Fisher–Rao distance) and that the upper bound is about twice the lower bound for that particular scenario.

Table 2.

Comparing our Fisher–Rao approximation with the Calvo and Oller lower bound and the upper bound of [38].

Second, since the distances are invariant under the action of the affine group, we can set wlog. (standard normal distribution) and let where . As normals and separate from each other, we notice experimentally that the performance of the curve degrades in the second experiment with (see Table 3): Indeed, the mixture geodesic works experimentally better than the C&O curve when .

Table 3.

Second set of experiments shows limitations of the curve.

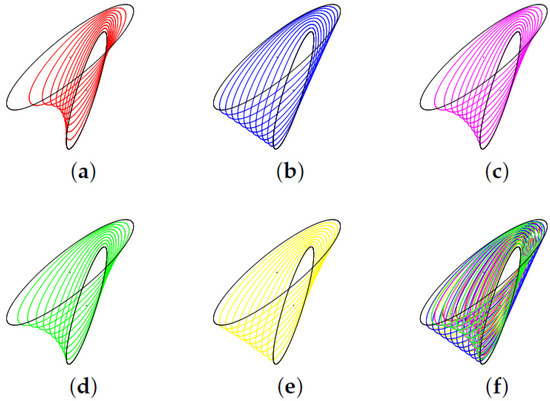

Figure 14 display the various curves considered for approximating the Fisher–Rao distance between bivariate normal distributions: For a curve , we visualize its corresponding bivariate normal distributions at several increment steps by plotting the ellipsoid

where .

Figure 14.

Visualizing at discrete positions (10 increment steps between 0 and 1) some curves used to approximate the Fisher–Rao distance between two bivariate normal distributions: (a) exponential geodesic (red), (b) mixture geodesic (blue), (c) mid-mixture-exponential curve (purple), (d) projected Calvo and Oller curve (green), (e) : ordinary linear interpolation in (yellow), and (f) All superposed curves at once.

Example 2.

Let us report some numerical results for bivariate normals with :

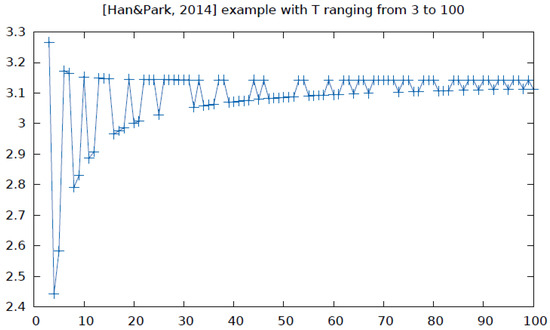

- We use the following example of Han and Park [39] (Equation (26)):Their geodesic shooting algorithm [39] evaluates the Fisher–Rao distance to (precision ).We obtain:In that setting, the upper bound is better than the upper bound of Equation (35), and the projected Calvo and Oller geodesic yields the best approximation of the Fisher–Rao distance (Figure 15) with an absolute error of (about relative error). When , we have , when , we obtain , and when we obtain (which is better than the approximation obtained for ). Figure 16 shows the fluctuations of the approximation of the Fisher–Rao distance by the projected C&O curve when T ranges from 3 to 100.

Figure 15. Comparison of our approximation curves with the Fisher–Rao geodesic (f) obtained by geodesic shooting (Figure 5 of [39]). Exponential (a) and mixture (b) geodesics with the mid-exponential-mixture curve (c), and the projected C&O curve (d). Superposed curves (e) and comparison with geodesic shooting (Figure 5 of [39]). Beware that color coding is not related between (a) and (f), and scale for depicting ellipsoids are different.

Figure 15. Comparison of our approximation curves with the Fisher–Rao geodesic (f) obtained by geodesic shooting (Figure 5 of [39]). Exponential (a) and mixture (b) geodesics with the mid-exponential-mixture curve (c), and the projected C&O curve (d). Superposed curves (e) and comparison with geodesic shooting (Figure 5 of [39]). Beware that color coding is not related between (a) and (f), and scale for depicting ellipsoids are different. Figure 16. Approximation of the Fisher–Rao distance obtained using the projected C&O curve when T ranges from 3 to 100 [39].

Figure 16. Approximation of the Fisher–Rao distance obtained using the projected C&O curve when T ranges from 3 to 100 [39]. - Bivariate normal and bivariate normal with and . We obtain

- –

- Calvo and Oller lower bound:

- –

- Upper bound of Equation (35):

- –

- upper bound:

- –

- :

- –

- :

- –

- :

- –

- :

- –

- :

- Bivariate normal and bivariate normal with and . We get:

- –

- Calvo and Oller lower bound:

- –

- Upper bound of Equation (35):

- –

- upper bound:

- –

- :

- –

- :

- –

- :

- –

- :

- –

- :

See Supplementary Materials for further experiments.

4. Approximating the Smallest Enclosing Fisher–Rao Ball of MVNs

We may use these closed-form distance between N and to compute an approximation (of the center) of the smallest enclosing Fisher–Rao ball of a set of nd-variate normal distributions:

where .

The method proceeds as follows:

- First, we convert MVN set into the equivalent set of -dimensional SPD matrices using the C&O embedding. We relax the problem of approximating the circumcenter of the smallest enclosing Fisher–Rao ball by

- Second, we approximate the center of the smallest enclosing Riemannian ball of using the iterative smallest enclosing Riemannian ball algorithm in [66] with say iterations. Let denote this approximation center: .

- Finally, we project back onto : . We return as the approximation of .

Algorithm [66] is described for a set of SPD matrices as follows:

- Let

- For to T

- –

- Compute the index of the SPD matrix which is farthest from the current circumcenter :

- –

- Update the circumcenter by walking along the geodesic linking to :

- Return

The convergence of the algorithm follows from the fact that the SPD trace manifold is a Hadamard manifold (with negative sectional curvatures). See [66] for proof of convergence.

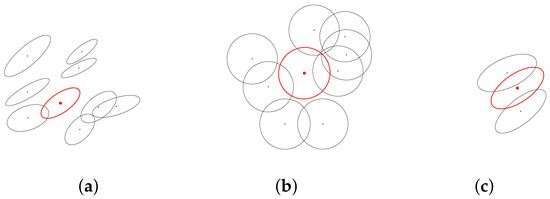

The SPD distance indicates the quality of the approximation. Figure 17 shows the result of implementing this heuristic.

Figure 17.

Approximation of the smallest enclosing Riemannian ball of a set of n bivariate normals with respect to C&O distance (the approximate circumcenter is depicted as a red ellipse): (a) with different covariance matrices, (b) with identical covariance matrices amount to the smallest enclosing ball of a set of n points , (c) displays the midpoint of the C&O geodesic visualized as an equivalent bivariate normal distribution in the sample space.

Let us notice that when all MVNs share the same covariance matrix , we have from Equation (18) or Equation (23) that and are strictly increasing function of their Mahalanobis distance. Using the Cholesky decomposition , we deduce that the smallest Fisher–Rao enclosing ball coincides with the smallest Calvo and Oller enclosing ball, and the circumcenter of that ball can be found as an ordinary Euclidean circumcenter [83] (Figure 17b). Please note that in 1D, we can find the exact smallest enclosing Fisher–Rao ball as an equivalent smallest enclosing ball in hyperbolic geometry.

Furthermore, we may extend the computation of the approximated circumcenter to k-center clustering [84] of n multivariate normal distributions. Since the circumcenter of the clusters is approximated and not exact, we extend straightforwardly the variational approach of k-means described in [85] to k-center clustering. An application of k-center clustering of MVNs is to simplify a Gaussian mixture model [42] (GMM).

Similarly, we can consider other Riemannian distances with closed-form formulas between MVNs such as the Killing distance in the symmetric space [82] (see Appendix C) or the Siegel-based distance proposed in Appendix D.

5. Some Information–Geometric Properties of the C&O Embedding

In information geometry [1], the manifold admits a dual structure denoted by the quadruple

when equipped with the exponential connection and the mixture connection . The connections and are said to be dual since , the Levi–Civita connection induced by . Furthermore, by viewing as an exponential family with natural parameter (using the sufficient statistics [80]), and taking the convex log-normalizer function of the normals, we can build a dually flat space [1] where the canonical divergence amounts to a Bregman divergence which coincides with the reverse Kullback–Leibler divergence [30,86] (KLD). The Legendre duality

(with ) yields: ,

,

and we have

where is the reverse KLD.

In a dually flat space, we can express the canonical divergence as a Fenchel–Young divergence using the mixed coordinate systems where and

The moment -parameterization of a normal is with its reciprocal function .

Let , , . Then we have the following proposition which proves that the Fenchel–Young divergences in and (as a submanifold of ) coincide:

Proposition 4.

We have

Consider now the -geodesics and -geodesics on (linear interpolation with respect to natural and dual moment parameterizations, respectively): and .

Proposition 5

(Mixture geodesics preserved). The mixture geodesics are preserved by the embedding f: . The exponential geodesics are preserved for the subspace of with fixed mean μ: .

Proof.

For the m-geodesics, let us check that

since . Thus, we have . □

Therefore, all algorithms on which only require m-geodesics or m-projections [1] by minimizing the right-hand side of the KLD can be implemented by algorithms on . See, for example, the minimum enclosing ball approximation algorithm called BBC in [87]. Notice that (fixed mean normal submanifolds) preserve both mixture and exponential geodesics: The submanifolds are said to be doubly autoparallel [88].

Remark 5.

In [2] (p. 355), exercises 13.8 and 13.9 ask to prove the equivalence of the following statements for a submanifold of :

- is an exponential family ⇔ is -autoparallel in (exercise 13.8),

- is a mixture family ⇔ is -autoparallel in (exercise 13.9).

Let (with ), , and . Then we have

Thus, is an exponential family. Therefore, we deduce that is -autoparallel in . However, is not a mixture family and thus is not -autoparallel in .

6. Conclusions and Discussion

In general, the Fisher–Rao distance between multivariate normals (MVNs) is not known in closed form. In practice, the Fisher–Rao distance is usually approximated by costly geodesic shooting techniques [39,40,41] which requires time-consuming computations of the Riemannian exponential map and are nevertheless limited to normals within a short range of each other. In this work, we consider a simple alternative approach for approximating the Fisher–Rao distance by approximating the Riemannian lengths of curves, which admits closed-form parameterizations. In particular, we considered the mixed exponential-mixture curved and the projected symmetric positive–definite matrix geodesic obtained from Calvo and Oller isometric submanifold embedding into the SPD cone [19]. We summarize our method to approximate between and as follows:

where

and

with

We proved the following sandwich bounds of our approximation

where

Notice that we may calculate equivalently as where for (see Proposition 3).

We also reported a fast way to upper bound the Fisher–Rao distance by the square root of Jeffreys’ divergence: which is tight at infinitesimal scale. In practice, this upper bound beats the upper bound of [38] when normal distributions are not too far from each other. Finally, we show that not only is Calvo and Oller SPD submanifold embedding [19] isometric, but it also preserves the Kullback–Leibler divergence, the Fenchel–Young divergence, and the mixture geodesics. Our approximation technique extends to elliptical distribution, which generalizes multivariate normal distributions [32,55]. Moreover, we obtained a closed form for the Fisher–Rao distance between normals sharing the same covariance matrix using the technique of maximal invariance under the action of the affine group in Section 1.5. We may also consider other distances different from the Fisher–Rao distance, which admits a closed-form formula: For example, the Calvo and Oller metric distance [19] (a lower bound on the Fisher–Rao distance) or the metric distance proposed in [82] (see Appendix C) whose geodesics enjoys the asymptotic property of the Fisher–Rao geodesics [89]). The C&O distance is very well-suited for short Fisher–Rao distances while the symmetric space distance is well-tailored for large Fisher–Rao distances. The calculations of these closed-form distances rely on generalized eigenvalues. We also propose an embedding of normals into the Siegel upper space in Appendix D. To conclude, let us propose yet another alternative distance, The Hilbert projective distance on the SPD cone [90], which only needs to calculate the minimal and maximal eigenvalues (say, using the power iteration method [91]):

The dissimilarity is said projective on the SPD cone because if and only if for some . However, let us notice that it yields a proper metric distance on :

since if and only if because the array element , i.e., implying by the isometric diffeomorphism f.

Notice that since , ,

, and , we have the following upper bound on Hilbert distance: .

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://franknielsen.github.io/FisherRaoMVN.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I warmly thank Frédéric Barbaresco (Thales) and Mohammad Emtiyaz Khan (Riken AIP) for fruitful discussions about this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Entities | |

| d-variate normal distribution (mean , covariance matrix ) | |

| Probability density function of | |

| Probability density function of | |

| Positive–definite matrix with matrix entries | |

| Mappings | |

| Calvo and Oller mapping [19] (1990) | |

| Calvo and Oller mapping [32] (2002) or [82] | |

| Groups | |

| Group of linear transformations (invertible matrices) | |

| Special linear group ( matrices with unit determinant) | |

| Affine group of dimension d | |

| Sets | |

| Set of multivariate normal distributions (MVNs) | |

| Set of symmetric real matrices | |

| Symmetric positive–definite matrix cone (SPD matrix cone) | |

| Set of SPD matrices with fixed determinant c () | |

| SSPD, | Set of SPD matrices with unit determinant |

| Parameter space of : | |

| , | Set of zero-centered normal distributions |

| Set of normal distributions with fixed | |

| Set of normal distributions with fixed | |

| Set of SPD matrices | |

| Riemannian length elements | |

| MVN Fisher | |

| 0-MVN Fisher | |

| SPD trace | (when , ) |

| SPD Calvo and Oller metric | |

| (with ) | |

| when , in | |

| SPD symmetric space | |

| Siegel upper space | () |

| Manifolds and submanifolds | |

| () | Manifold of multivariate normal distributions |

| Tangent space at | |

| Submanifold of MVNs with prescribed | |

| Submanifold of MVNs with prescribed | |

| manifold of (non-embedded in ) | |

| manifold of (non-embedded in ) | |

| Submanifold of MVN set | |

| where v is an eigenvector of | |

| manifold of symmetric positive–definite matrices | |

| Distances | |

| Fisher–Rao distance between normal distributions and | |

| Riemannian SPD distance between and | |

| Calvo and Oller distance from embedding N to | |

| Symmetric space distance from embedding N to | |

| Hilbert distance | |

| Kullback–Leibler divergence between MVNs and | |

| Jeffreys divergence between MVNs and | |

| Calvo and Oller dissimilarity measure of Equation (26) | |

| Geodesics and curves | |

| Fisher–Rao geodesic between MVNs and | |

| Fisher–Rao geodesic between SPD and | |

| exponential geodesic between MVNs and | |

| mixture geodesic between MVNs and | |

| projection curve (not geodesic) of onto | |

| Metrics and connections | |

| Fisher information metric of MVNs | |

| trace metric | |

| Fisher information metric of centered MVNs | |

| Killing metric studied in [82] | |

| Levi–Civita metric connection | |

| exponential connection | |

| mixture connection |

Appendix A. Geodesics on the Fisher–Rao Normal Manifold

Appendix A.1. Parametric Equations of the Fisher–Rao Geodesics between Univariate Normal Distributions

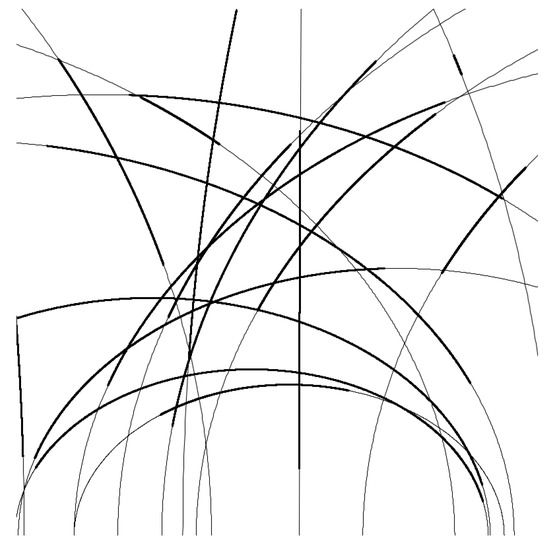

The Fisher–Rao geodesics on the Fisher–Rao univariate normal manifolds are either vertical line segments when , or semi-circle with origin on the x-axis and x-axis stretched by [92] (Figure A1):

where

and

provided that for (otherwise, we let ).

Figure A1.

Visualizing some Fisher–Rao geodesics of univariate normal distributions on the stretched Poincaré upper plane (semi-circles with origin on the x-axis and stretched by on the x-axis). Full geodesics are plotted with a thin gray style and geodesic arcs are plotted with a thick black style.

Notice that it is remarkable that the Fisher–Rao distance between normal distributions is available in closed form: Indeed, the Euclidean length (with respect to the Euclidean metric) of semi-ellipse curves (perimeters) is not known in closed form but can be expressed using the so-called complete elliptic integral of the second kind [93].

Appendix A.2. Geodesics with Initial Values on the Multivariate Fisher–Rao Normal Manifold

The geodesic equation is given by

We concisely report the parametric geodesics using another variant of the natural parameters of the normal distributions (slightly differing from the -coordinate system since natural parameters can be chosen up to a fixed affine transformation by changing accordingly the sufficient statistics by the inverse affine transformation) viewed as an exponential family:

In general, the geodesics with boundary values are not known in closed form. However, Calvo and Oller [48] (Theorem 3.1 and Corollary 1) reported the explicit equations of the geodesics when the initial values are given, i.e., where is in and .

Let

and be the Moore–Penrose generalized inverse matrix of G: or . The Moore–Penrose pseudo-inverse matrix can be replaced by any other pseudo-inverse matrix [48].

Then we have with

where the Cosh and Sinh functions of a matrix M are defined by the following absolutely convergent series [48] (Equation (9), p. 122):

and satisfies the identity . The matrix Cosh and Sinh functions can be calculated from the eigendecomposition of as follows:

When we restrict the manifold to a totally geodesic submanifold , the geodesic equation becomes , and the geodesic with initial values and is:

The geodesic with boundary values and is

Furthermore, we can convert a geodesic with boundary values to an equivalent geodesic with initial values by letting

Appendix B. Fisher–Rao Distance between Normal Distributions Sharing the Same Covariance Matrix

The Rao distance between and has been reported in closed form [42] (Proposition 3). We shall explain the geometric method in full as follows: Let be the standard frame of (ordered basis): The ’s are the unit vectors of the axis ’s. Let P be an orthogonal matrix such that (i.e., matrix P aligns vector to the first axis ). Let be the Euclidean distance between and . Furthermore, factorize matrix using the LDL decomposition (a variant of the Cholesky decomposition) as where L is a lower triangular matrix with all diagonal entries equal to one (lower unitriangular matrix of unit determinant) and D a diagonal matrix. Let . Then we have [42]:

Please note that the right-hand side term is the Fisher–Rao distance between univariate normal distributions of Equation (7).

To find matrix P, we proceed as follows: Let be the normalized vector to align on axis . Let . Consider the Householder reflection matrix [94], where is an outer product matrix. Since Householder reflection matrices have determinant , we let P be a copy of M with the last row multiplied by so that we obtain . By construction, we have . We then use the affine-invariance property of the Fisher–Rao distance as follows:

The last row follows from the fact that since is an upper unitriangular matrix, and . The right-hand side Fisher–Rao distance is computed from Equation (7).

Appendix C. Embedding the Set of Multivariate Normal Distributions in a Riemannian Symmetric Space

The multivariate Gaussian manifold can also be embedded into the SPD cone as a Riemannian symmetric space [82,89] by : . We have [82,95,96] (and textbook [97], Part II Chapter 10), and the symmetric space can be embedded with the Killing Riemannian metric instead of the Fisher information metric:

where is a predetermined constant (e.g., 1). The length element of the Killing metric is

When we consider , we may choose so that the Killing metric coincides with the Fisher information metric. The induced Killing distance [82] is available in closed form:

where is the unique lower triangular matrix obtained from the Cholesky decomposition of . Please note that and , i.e., .

When and (), we have [82]

where is the squared Mahalanobis distance. Thus, where .

When and (), we have [82]:

See Example 1. Let us emphasize that the Killing distance is not the Fisher–Rao distance but is available in closed form as an alternative metric distance between MVNs.

A Fisher geodesic defect measure of a curve c is defined in [89] by

where denotes the Levi–Civita connection induced by the Fisher metric. When the curve is said to be an asymptotic geodesic of the Fisher geodesic. It is proven that Killing geodesics at are asymptotic Fisher geodesics when the initial condition is orthogonal to .

Appendix D. Embedding the Set of Multivariate Normal Distributions in the Siegel Upper Space

The Siegel upper space is the space of symmetric complex matrices with imaginary positive–definite matrices [45,65] (so-called Riemann matrices [98]):

where is the space of symmetric real matrices. corresponds to the Poincaré upper plane. See Figure A2 for an illustration.

The Siegel infinitesimal square line element is

When and , we have , , and it follows that

That is, four times the square length of the Fisher matrix of centered normal distributions .

The Siegel distance [45] between and is

where

with denoting the matrix generalization of the cross-ratio

and denoting the i-th largest (real) eigenvalue of (complex) matrix M. (In practice, we numerically must round off the tiny imaginary parts to obtain proper real eigenvalues [65].) The Siegel upper half space is a homogeneous space where the Lie Group acts transitively on it.

We can embed a multivariate normal distribution into as follows:

and consider the Siegel distance on the embedded normal distributions as another potential metric distance between multivariate normal distributions:

Notice that the real matrix part of the ’s are all of rank one by construction.

Figure A2.

Siegel upper space generalizes the Poincaré hyperbolic upper plane.

Appendix E. The Symmetrized Bregman Divergence Expressed as Integral Energies on Dual Geodesics

Let be a symmetrized Bregman divergence. Let denote the squared length element on the Bregman manifold and denote by and the dual geodesics connecting to . We can express as integral energies on dual geodesics:

Property A1.

We have .

Proof.

The proof that the symmetrized Bregman divergence amount to these energy integrals is based on the first-order and second-order directional derivatives. The first-order directional derivative with respect to vector u is defined by

The second-order directional derivatives is

Now consider the squared length element on the primal geodesic expressed using the primal coordinate system : with and . Let us express the using the second-order directional derivative:

Thus, we have , where the first-order directional derivative is . Therefore we obtain .

Similarly, we express the squared length element using the dual coordinate system as the second-order directional derivative of with :

Therefore, we have . Since , we conclude that

Please note that in 1D, both pregeodesics and coincide. We have so that we check that . □

References

- Amari, S.I. Information Geometry and Its Applications; Applied Mathematical Sciences; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Calin, O.; Udrişte, C. Geometric Modeling in Probability and Statistics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 121. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z. Riemannian geometry of symmetric positive definite matrices via Cholesky decomposition. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2019, 40, 1353–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soen, A.; Sun, K. On the variance of the Fisher information for deep learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 5708–5719. [Google Scholar]

- Barachant, A.; Bonnet, S.; Congedo, M.; Jutten, C. Classification of covariance matrices using a Riemannian-based kernel for BCI applications. Neurocomputing 2013, 112, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovgaard, L.T. A Riemannian Geometry of the Multivariate Normal Model; Technical Report 81/3; Statistical Research Unit, Danish Medical Research Council, Danish Social Science Research Council: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Skovgaard, L.T. A Riemannian geometry of the multivariate normal model. Scand. J. Stat. 1984, 11, 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Malagò, L.; Pistone, G. Information geometry of the Gaussian distribution in view of stochastic optimization. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Foundations of Genetic Algorithms XIII, Aberystwyth, UK, 17–22 January 2015; pp. 150–162. [Google Scholar]

- Herntier, T.; Peter, A.M. Transversality Conditions for Geodesics on the Statistical Manifold of Multivariate Gaussian Distributions. Entropy 2022, 24, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, C.; Mitchell, A.F. Rao’s distance measure. SankhyĀ Indian J. Stat. Ser. 1981, 43, 345–365. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishna Rao, C. Information and accuracy attainable in the estimation of statistical parameters. Bull. Calcutta Math. Soc. 1945, 37, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, J.; Hu, S. Upper bounds for Rao distance on the manifold of multivariate elliptical distributions. Automatica 2021, 129, 109604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotelling, H. Spaces of statistical parameters. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 1930, 36, 191. [Google Scholar]

- Cencov, N.N. Statistical Decision Rules and Optimal Inference; American Mathematical Soc.: Providence, RI, USA, 2000; Volume 53. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M.; Bruveris, M.; Michor, P.W. Uniqueness of the Fisher–Rao metric on the space of smooth densities. Bull. Lond. Math. Soc. 2016, 48, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, A. Hommage to Chentsov’s theorem. Inf. Geom. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruveris, M.; Michor, P.W. Geometry of the Fisher–Rao metric on the space of smooth densities on a compact manifold. Math. Nachrichten 2019, 292, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbea, J.; Oller i Sala, J.M. On Rao Distance Asymptotic Distribution; Technical Report Mathematics Preprint Series No. 67; Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, M.; Oller, J.M. A distance between multivariate normal distributions based in an embedding into the Siegel group. J. Multivar. Anal. 1990, 35, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, M.; Villarroya, A.; Oller, J.M. Rao distance between multivariate linear normal models and their application to the classification of response curves. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 1992, 13, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, P.S.; Kshirsagar, A.M. Distances between normal populations when covariance matrices are unequal. Commun. Stat. Theory Methods 1994, 23, 3549–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, M.H. Some applications of the Rao distance to shrinkage estimators. Commun. Stat. Methods 2008, 37, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strapasson, J.E.; Pinele, J.; Costa, S.I. Clustering using the Fisher-Rao distance. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Sensor Array and Multichannel Signal Processing Workshop (SAM), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 10–13 July 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Le Brigant, A.; Puechmorel, S. Quantization and clustering on Riemannian manifolds with an application to air traffic analysis. J. Multivar. Anal. 2019, 173, 685–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S.; Bombrun, L.; Berthoumieu, Y. Texture classification using Rao’s distance on the space of covariance matrices. In Proceedings of the Geometric Science of Information: Second International Conference, GSI 2015, Proceedings 2, Palaiseau, France, 28–30 October 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Legrand, L.; Grivel, E. Evaluating dissimilarities between two moving-average models: A comparative study between Jeffrey’s divergence and Rao distance. In Proceedings of the 2016 24th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Budapest, Hungary, 8 August–2 September 2016; pp. 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Halder, A.; Georgiou, T.T. Gradient flows in filtering and Fisher-Rao geometry. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual American Control Conference (ACC), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 27–29 June 2018; pp. 4281–4286. [Google Scholar]

- Collas, A.; Breloy, A.; Ren, C.; Ginolhac, G.; Ovarlez, J.P. Riemannian optimization for non-centered mixture of scaled Gaussian distributions. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.03315. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T.; Poggio, T.; Rakhlin, A.; Stokes, J. Fisher-Rao metric, geometry, and complexity of neural networks. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, PMLR, Naha, Japan, 16–18 April 2019; pp. 888–896. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizawa, S.; Tanabe, K. Dual differential geometry associated with the Kullback-Leibler information on the Gaussian distributions and its 2-parameter deformations. SUT J. Math. 1999, 35, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, H. The Geometry of Hessian Structures; World Scientific: Singapore, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, M.; Oller, J.M. A distance between elliptical distributions based in an embedding into the Siegel group. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2002, 145, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbea, J. Informative Geometry of Probability Spaces; Technical Report; Pittsburgh Univ. PA Center for Multivariate Analysis: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, P.S. Geodesics Connected with the Fischer Metric on the Multivariate Normal Manifold; Institute of Electronic Systems, Aalborg University Centre: Aalborg, Denmark, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Berkane, M.; Oden, K.; Bentler, P.M. Geodesic estimation in elliptical distributions. J. Multivar. Anal. 1997, 63, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, T.; Takaesu, A.; Wakayama, M. Remarks on Geodesics for Multivariate Normal Models; Technical Report; Faculty of Mathematics, Kyushu University: Fukuoka, Japan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, H. Group theoretical study on geodesics for the elliptical models. In Proceedings of the Geometric Science of Information: Second International Conference, GSI 2015, Proceedings 2, Palaiseau, France, 28–30 October 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 605–614. [Google Scholar]

- Strapasson, J.E.; Porto, J.P.; Costa, S.I. On bounds for the Fisher-Rao distance between multivariate normal distributions. AIP Conf. Proc. 2015, 1641, 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.; Park, F.C. DTI segmentation and fiber tracking using metrics on multivariate normal distributions. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 2014, 49, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilté, M.; Barbaresco, F. Tracking quality monitoring based on information geometry and geodesic shooting. In Proceedings of the 2016 17th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Krakow, Poland, 10–12 May 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaresco, F. Souriau exponential map algorithm for machine learning on matrix Lie groups. In Proceedings of the Geometric Science of Information: 4th International Conference, GSI 2019, Proceedings 4, Toulouse, France, 27–29 August 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Pinele, J.; Strapasson, J.E.; Costa, S.I. The Fisher–Rao distance between multivariate normal distributions: Special cases, bounds and applications. Entropy 2020, 22, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, E.W. A note on two problems in connexion with graphs. In Edsger Wybe Dijkstra: His Life, Work, and Legacy; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 287–290. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.W. Hyperbolic Geometry; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, C.L. Symplectic Geometry; First Printed in 1964; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- James, A.T. The variance information manifold and the functions on it. In Multivariate Analysis–III; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1973; pp. 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, J.; Cook, M.; Pine, K.; Robinson, B.D. Fisher-Rao distance on the covariance cone. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.15861. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, M.; Oller, J.M. An explicit solution of information geodesic equations for the multivariate normal model. Stat. Risk Model. 1991, 9, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstner, W.; Moonen, B. A metric for covariance matrices. In Geodesy-the Challenge of the 3rd Millennium; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- Dolcetti, A.; Pertici, D. Real square roots of matrices: Differential properties in semi-simple, symmetric and orthogonal cases. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.15609. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalanobis, P.C. On the generalised distance in statistics. In Proceedings of the National Institute of Science of India; Springer: New Delhi, India, 1936; Volume 12, pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, M.L. Group Invariance Applications in Statistics; Institute of Mathematical Statistics: Beachwood, OH, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Godinho, L.; Natário, J. An introduction to Riemannian geometry: With Applications to Mechanics and Relativity. In Universitext; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Strapasson, J.E.; Pinele, J.; Costa, S.I. A totally geodesic submanifold of the multivariate normal distributions and bounds for the Fisher-Rao distance. In Proceedings of the IEEE Information Theory Workshop (ITW), Cambridge, UK, 1–11 September 2016; pp. 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, J. Multisensor Estimation Fusion on Statistical Manifold. Entropy 2022, 24, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, A.; Sra, S. Riemannian dictionary learning and sparse coding for positive definite matrices. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2016, 28, 2859–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.S. Geomnet: A neural network based on Riemannian geometries of SPD matrix space and Cholesky space for 3d skeleton-based interaction recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 13379–13389. [Google Scholar]

- Dolcetti, A.; Pertici, D. Differential properties of spaces of symmetric real matrices. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.01113. [Google Scholar]

- Verdoolaege, G.; Scheunders, P. On the geometry of multivariate generalized Gaussian models. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 2012, 43, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.M.; Silvey, S.D. A general class of coefficients of divergence of one distribution from another. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1966, 28, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiszár, I. Information-type measures of difference of probability distributions and indirect observation. Stud. Sci. Math. Hung. 1967, 2, 229–318. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, F.; Okamura, K. A note on the f-divergences between multivariate location-scale families with either prescribed scale matrices or location parameters. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.10952. [Google Scholar]

- Moakher, M.; Zéraï, M. The Riemannian geometry of the space of positive-definite matrices and its application to the regularization of positive-definite matrix-valued data. J. Math. Imaging Vis. 2011, 40, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcetti, A.; Pertici, D. Elliptic isometries of the manifold of positive definite real matrices with the trace metric. Rend. Circ. Mat. Palermo Ser. 2 2021, 70, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F. The Siegel–Klein Disk: Hilbert Geometry of the Siegel Disk Domain. Entropy 2020, 22, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaudon, M.; Nielsen, F. On approximating the Riemannian 1-center. Comput. Geom. 2013, 46, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceolin, S.R.; Hancock, E.R. Computing gender difference using Fisher-Rao metric from facial surface normals. In Proceedings of the 25th SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images, Ouro Preto, Brazil, 22–25 August 2012; pp. 336–343. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Li, P.; Zhang, L. G2DeNet: Global Gaussian distribution embedding network and its application to visual recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2730–2739. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, H.K.; Meneghetti, F.C.; Costa, S.I. The Fisher–Rao loss for learning under label noise. Inf. Geom. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtek, S.; Bharath, K. Bayesian sensitivity analysis with the Fisher–Rao metric. Biometrika 2015, 102, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, G.; Andler, S.; Nielsen, F.; Donnat, P. Optimal transport vs. Fisher-Rao distance between copulas for clustering multivariate time series. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Statistical Signal Processing Workshop (SSP), Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 26–29 June 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.; Rong, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.R. Information geometric approach to multisensor estimation fusion. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2018, 67, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, R.; Huang, Z.; Shan, S.; Chen, X. Discriminant analysis on Riemannian manifold of Gaussian distributions for face recognition with image sets. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 2048–2057. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Wang, Q.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, L. Local log-Euclidean multivariate Gaussian descriptor and its application to image classification. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picot, M.; Messina, F.; Boudiaf, M.; Labeau, F.; Ayed, I.B.; Piantanida, P. Adversarial robustness via Fisher-Rao regularization. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 2698–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collas, A.; Bouchard, F.; Ginolhac, G.; Breloy, A.; Ren, C.; Ovarlez, J.P. On the Use of Geodesic Triangles between Gaussian Distributions for Classification Problems. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 5697–5701. [Google Scholar]

- Murena, P.A.; Cornuéjols, A.; Dessalles, J.L. Opening the parallelogram: Considerations on non-Euclidean analogies. In Proceedings of the Case-Based Reasoning Research and Development: 26th International Conference, ICCBR 2018, Proceedings 26, Stockholm, Sweden, 9–12 July 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 597–611. [Google Scholar]

- Popović, B.; Janev, M.; Krstanović, L.; Simić, N.; Delić, V. Measure of Similarity between GMMs Based on Geometry-Aware Dimensionality Reduction. Mathematics 2022, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]