Abstract

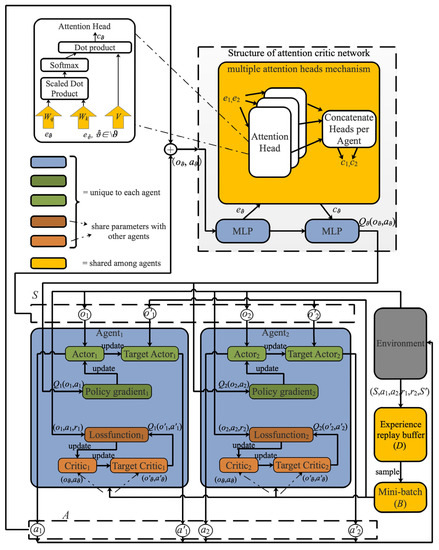

The breakthrough of wireless energy transmission (WET) technology has greatly promoted the wireless rechargeable sensor networks (WRSNs). A promising method to overcome the energy constraint problem in WRSNs is mobile charging by employing a mobile charger to charge sensors via WET. Recently, more and more studies have been conducted for mobile charging scheduling under dynamic charging environments, ignoring the consideration of the joint charging sequence scheduling and charging ratio control (JSSRC) optimal design. This paper will propose a novel attention-shared multi-agent actor–critic-based deep reinforcement learning approach for JSSRC (AMADRL-JSSRC). In AMADRL-JSSRC, we employ two heterogeneous agents named charging sequence scheduler and charging ratio controller with an independent actor network and critic network. Meanwhile, we design the reward function for them, respectively, by considering the tour length and the number of dead sensors. The AMADRL-JSSRC trains decentralized policies in multi-agent environments, using a centralized computing critic network to share an attention mechanism, and it selects relevant policy information for each agent at every charging decision. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed AMADRL-JSSRC can efficiently prolong the lifetime of the network and reduce the number of death sensors compared with the baseline algorithms.

1. Introduction

Wireless sensor networks (WSNs) have been widely applied in target tracking, environment monitoring, intelligent medical and military monitoring, etc. [1,2], which have advantages including fast construction, self-organization, fault tolerance, and low-cost deployment [3]. Meanwhile, WSNs are usually composed of a large scale of sensors deployed in an area. However, sensors in WSN are always powered by batteries, and the capacity of these batteries is constrained by the volume of the sensor, which limits the lifetime of the sensors. Furthermore, the energy constraint problem affects the quality of service of WSN directly and greatly hinders the development of WSN. In recent years, the breakthrough of wireless energy transmission (WET) technology has greatly promoted the wireless rechargeable sensor networks (WRSNs) [4], since it provides a highly reliable and efficient energy supplement for the sensors. Particularly, a promising method to overcome the energy constraint problem in WRSNs is mobile charging by employing one or more mobile chargers (MCs) with a high capacity to charge sensors via WET. The MC can move to sensors autonomously and charge them according to a mobile charging scheduling scheme, which is formulated by MC based on the status information of sensors, including the residual energy, energy consumption rate, and position of sensors in WRSN. The status information of sensors is highly controllable and predictable. Theoretically, WRSNs could work indefinitely under a well-designed charging scheme [5]. Therefore, the design of the charging scheme in WRSN is critical, and it has drawn extensive attention from the research community.

There are plenty of works that have been presented to design the mobile charging schemes on WRSN. According to whether MC carries the determined charging scheme before starting from the base station, the existing works can be divided into two categories [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]: (1) offline methods [7,8,9,10,11,12] and (2) online methods [6,13,14,15,16]. In offline methods, before starting from the base station, MC will formulate a transparent charging scheme according to the status of sensors, including accurate location, fixed energy consumption rate, regular information transmission rate, etc. The MC will charge sensors with a scheduled trajectory determined by the charging scheme. The offline methods ignore the dynamic change in the status of sensors. Hence, the offline method is not suitable for dealing with application scenarios where the energy consumption rate of the sensor changes in real time and the large-scale WRSN. For example, Yan et al. [17] first attempted to introduce particle swarm optimization into optical wireless sensor networks, which could optimize the positioning of nodes, reduce the energy consumption of nodes effectively and converge faster. In [18], Shu et al. made the first attempt to deal with the jointly charging energy and designing operation scheduling in WRSN. They proposed an f-Approximate algorithm to address this problem and verify that the proposed algorithm could obtain an average 39.2% improvement of network lifetime beyond the baseline approaches. In [19], Feng et al. designed a novel algorithm called the newborn particle swarm optimization algorithm for charging-scheduling in industrial rechargeable sensor networks by adding new particles to improve the particle diversity. This improvement made the algorithm achieve better global optimization ability and improved the searching speed. V.K. Chawra et al. proposed a novel algorithm for scheduling multiple mobile rechargers using the hybrid meta-heuristic technique in [20], which combined the best features of the Cuckoo Search and Genetic Algorithm to optimize the path scheduling problem to achieve shorter charging latency and more significant energy usage efficiency. To enhance the charging efficiency [21,22,23,24], Zhang et al., Liang et al., and Wu et al. proposed some hierarchical charging methods for multiple MCs to charge sensors and themselves.

Different from the offline methods, in some application scenarios, the energy consumption rate of sensors is time-variant, and there are many uncertain factors in the network, which make the offline approaches unable to obtain an acceptable charging scheduling scheme according to the information in the network, while online approaches could successfully deal with these issues. The specific implementation is that the MC does not need to know the status of sensors clearly before starting from the base station but only needs to build candidate charging queues. When the residual energy of the sensor is lower than the set threshold, it will send a charging request and its energy information to the MC. The MC accepts the charging request and inserts it into all candidate charging queues. Then, the charging sequence will update according to the status of the sensors. For example, Lin et al. aimed to maximize the charging efficiency while minimizing the number of dead sensors to achieve the purpose of prolonging the lifetime of WRSN in [16]. Therefore, they developed a temporal–spatial real-time charging scheduling algorithm (TSCA) for the on-demand charging architecture. Furthermore, they also verified that the TSCA algorithm could obtain a better charging throughput, charging efficiency, and successful charging rate than the existing online algorithms, including Nearest-Job-Next with Preemption scheme and Double Warning thresholds with Double Preemption charging scheme. Feng et al. [25] proposed a mobile energy charging scheme that can improve the charging performance in WRSN by merging the advantages of online mode and offline mode. It includes the dynamicity of sensors’ energy consumption in the online mode and the benefit of lower charging consumption by optimizing the charging path of the mobile charger in offline mode. Kaswan et al. converted a charging scheduling problem to a linear programming problem and presented a gravitational search algorithm [26]. This approach presented a novel agent representation scheme and an efficient fitness function. In [27], Tomar et al. proposed a novel scheduling scheme for on-demand charging in WRSNs to address the joint consideration of multiple mobile chargers and the issue of ill-timed charging response to the nodes with variable energy consumption rates.

Unfortunately, although the online methods can address the mobile charging dynamic scheduling problem, they still have disadvantages, including short-sightedness, non-global optimization, and unfairness. Specifically, most recent works assume that the sensor closest to MC is usually inserted into the current charging queue. Meanwhile, sensors with low energy consumption rates are always ignored, resulting in their premature death and a reduction in the service quality of the WRSN. It is generally known that the mobile charging path planning problem in WRSN is a Markov decision process, which has been proved to be an NP-hard problem in [28]. Therefore, the most difficult problem is how to design an effective scheduling scheme to find the optimal or near-optimal solution more quickly and reliably when the size of network increases gradually.

It is known that Reinforcement Learning (RL) is an effective method to address the Markov decision process. As mentioned above, the charging scheduling problem in WRSN is NP-hard; thus, it is unable to provide available optimal labels for supervised learning. However, the quality of a set of charging decision can be evaluated via the reward feedback. Therefore, we need to design a reasonable reward function according to the states of WRSN for RL. During the interaction between agent and environment, the charging scheduling scheme will be found through learning strategies that can maximize the reward. There are several works that have tried to solve the charging scheduling problem with RL algorithms. For example, Wei et al. [29] and Soni and Shrivastava [30] proposed a charging path planning algorithm (CSRL), combining RL and MC to extend the network lifetime and improve the autonomy of MC. However, the proposed CSRL method only suits offline mode, where the energy consumption of sensor nodes is time-invariant. Meanwhile, this method can only be used to address small-scale networks, since the Q-learning algorithm generally fails to handle high-dimensional state space or large state space. Cao et al. [28] proposed a deep reinforcement learning-based on-demand charging algorithm to maximize the sum of rewards collected by the mobile charger in WRSN, which is subject to the energy capacity constraint on the mobile charger and the charging times of all sensor nodes. A novel charging scheme for dynamic WRSNs based on an actor–critic reinforcement learning algorithm was proposed by Yang et al. [31], which aimed to maximize the charging efficiency while minimizing the number of dead sensors to prolong the network lifetime. The above works have made significant model innovation and algorithm innovation, yet they ignore the impact of sensor charging energy on the optimization performance. Although Yang et al. [31] proposed a charging coefficient to constrain the upper charging energy threshold, they assumed that all sensors have a fixed charging coefficient during the scheduling, which cannot adjust according to the needs of the sensors. Specifically, the charging coefficient could directly determine the charging energy for the sensor. Therefore, how to select the next sensor to be charged and determining its corresponding charging energy brings novel challenges to the design of the charging scheme.

We study a joint mobile charging sequence scheduling and charging ratio control problem (JSSRC) to address the challenges mentioned above, where charging ratio is a parameter introduced to determine the charging energy for the sensor and replace on-demand charging requests with real-time changing demands. JSSRC provides timely, reliable, and global charging schemes for WRSNs in which sensors’ energy changes dynamically. Meanwhile, we propose the attention-shared multi-agent actor–critic deep reinforcement learning approach for JSSRC; this approach is abbreviated as AMADRL-JSSRC. We assume that the network deployment scenarios are friendly, barrier-free, and accessible. The transmission of information about real-time changes in energy consumption is reliable and deterministic. When the residual energy of MC is insufficient, it is allowed to return to the depot to renew its battery.

Table 1 highlights the performance comparison of the existing approaches and the proposed approach with respect to four key attributes.

Table 1.

Performance Comparison of the Existing Approaches and the Proposed Approach.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows.

- (1)

- Different from the existing works, we consider both charging sequence and charging ratio optimization simultaneously in this paper. We introduce two heterogeneous agents named charging sequence scheduler and charging ratio controller. These two agents give the charging decisions separately under the dynamic changing environments, which aims to prolong the lifetime of the network and minimize the number of dead sensors.

- (2)

- We design a novel reward function with a penalty coefficient by comprehensively considering the tour length of MC and the number of dead sensors for AMADRL-JSSRC, so as to promote the agents to make better decisions.

- (3)

- We introduce the attention shared mechanism in AMADRL-JSSRC to the problem that charging sequence and charging ratio have different contributions to the reward function.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the system models of WRSN and formulates the JSSRC problem. The proposed AMADRL-JSSRC approach is described in Section 3. Simulation results are reported in Section 4. The impacts of the parameters on the charging performance are discussed in Section 5. Conclusions and future work are given in Section 5.

2. System Model and Problem Formulation

In this section, we present the network structure, energy consumption model of sensors, energy analysis of MC, and the formulation of the charging scheduling problem in WRSNs.

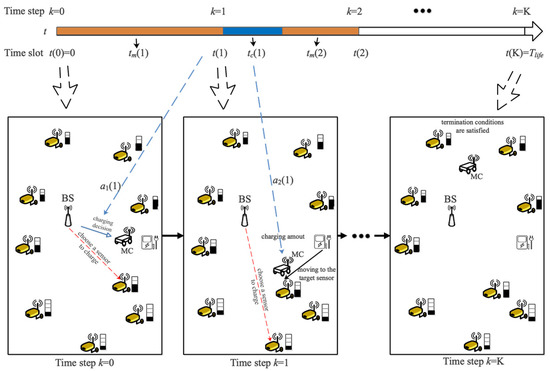

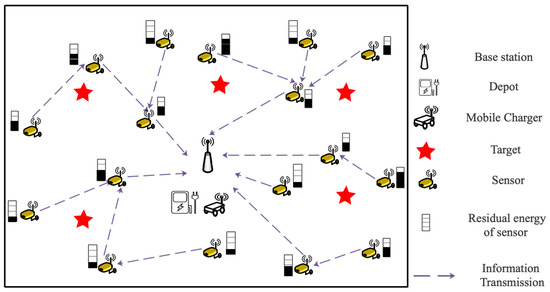

2.1. Network Structure

In Figure 1, a WRSN with n heterogeneous isomorphic sensors , an MC, a base station (BS), and a depot are adopted. It is assumed that due to different information transmission tasks, all sensors have the same energy capacity and sensing ability but different energy consumption rates. They are deployed in a 2D area without obstacles; the positions of all sensors are fixed and can be determined accurately, and they are recorded as , and the position of BS is set as . Therefore, a weighted undirected graph is used to describe the network model of WRSN, where is the set of distances between sensors, which is expressed as with . The set of initial residual energy and the energy consumption rate of each sensor are represented by and , respectively. is defined as the position of the depot.

Figure 1.

An example WRSN with a mobile charger.

It is assumed that each sensor in WRSN collects data and communicates with BS via ad hoc communication. The BS could estimate their residual energy according to data sampling frequency and transmission flow. MC can obtain the state information of the sensor but will not interfere with the working state of the sensor. Meanwhile, the total moving distance of MC during the charging tour is defined as .

Although, in theory, the lifetime of the network can be extended indefinitely with single or multiple MC. The network will shut down, since the energy modules of sensors will age. Therefore, inspired by [28,31], we define the lifetime in this article as below.

Definition 1 (Lifetime).

The lifetime of WRSNs is defined as the period from the beginning of the network to the number of dead sensors reaching a threshold.

The lifetime and the threshold are described with and , respectively. Furthermore, the abbreviations used in this paper are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Abbreviations used in this paper.

2.2. Energy Consumption Model of Sensors

The energy of the sensor is mainly consumed in data transmission and reception. Therefore, based on [32,33], the energy consumption model at time slot t is adopted as below:

where is the energy consumption for receiving or transmitting 1 kb data from sensor to sensor (or BS). represents the energy consumption for transmitting 1 kb data between each sensor, where is the distance between and . and represent the distance-free and distance-related energy consumption index, respectively. r is the signal attenuation coefficient. means the data flow of receiving, and are the data flow of transmitting from to and BS. Hence, represents the energy consumption of receiving information from all sensor nodes. is the energy consumption of by sending information to other sensors and BS.

2.3. Charging Model of MC

In this paper, the sensors in WRSN are charged by MC wirelessly, and the empirical wireless charging model is defined as [34]

where represents the distance between the sensor and the mobile charger, is the output power, is the gain of the source antenna which is equipped on the mobile charger, is the gain of the receiver antenna, is the distance between the mobile charger and the sensor, , and denote the rectifier efficiency and the parameter to adjust the Friis’ free space equation for short-distance transmission, respectively.

Since the MC moves to the position near the sensors, the distance can be regarded as a constant. Therefore, (2) can be simplified to (3)

in which , .

The moving speed of the MC is set as , and the energy consumed per meter is . The capacity of MC is , and the target sensor will be charged with one-to-one charging mode only when the MC reaches it.

2.4. Problem Formulation

We define three labels to describe the working states of the visited point at time slot t, , and . They represent that is selected to charge, not be selected and dead, respectively, while represents that the visited point is a depot. The residual energy of the sensor is defined as , the charging demand of sensor is defined as and the residual energy of MC is defined as .

At time slot t, the residual energy of the sensor is described as (4), and the charging demand will also be updated with (5)

where is the charging ratio, it could decide the upper threshold of charging energy, and its value range in .

To effectively charge the sensors, more energy in the MC should be used on charging sensors, while the energy wasted on moving between the sensors and the depot should be minimized. Hence, within the network lifetime , the JSSRC problem under WRSNs with the dynamic energy changing is defined as below.

Definition 2 (JSSRC).

The joint mobile charging sequence scheduling and the charging ratio control problem, which aims to prolong the lifetime of the network and minimize the number of dead sensors in WRSNs with dynamic energy changing, is defined as the JSSRC problem.

The relevant notations are defined as follows: at time slot , the current state of sensor i is defined as (6) according to its residual energy, if , it indicates that the sensor is alive, and represents that the sensor has died.

Furthermore, the number of dead sensors is defined as (t), which is obtained with (7)

There are three termination conditions of the JSSRC scheme, and they are described with (8):

- (1)

- The number of dead sensors reaches % of the total number, .

- (2)

- The remaining energy of MC is insufficient to return to the depot.

- (3)

- The target lifetime or the base time is reached.where represent the distance from the MC’s current location to the depot, is the running time of the test, and is a given base time. Specifically, when any of the termination conditions in (8) are met, the charging process will end.

Then, within the network lifetime, the JSSRC problem can be formulated as

4. Experimental Setup and Results

In this section, we will conduct experiments to evaluate the performance of AMADRL-JSSRC. The simulations are divided into two phases: (1) the training phase of AMADRL-JSSRC and (2) the testing phase for a comparative study with baseline algorithms. The experiment setting and training details are described in Section 4.1. The testing details of the comparison with the baseline algorithms are described in Section 4.2.

4.1. Experimental Environment and Details

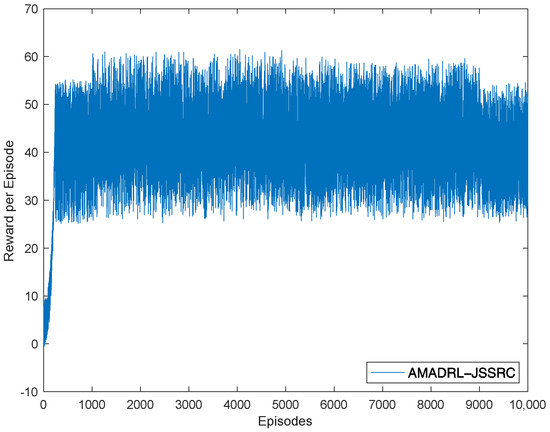

We conduct the AMADRL-JSSRC using Python 3.9.7 and TensorFlow 2.7.0 over 10,000 episodes, and each episode is divided into 100 time slots. Then, AMADRL-JSSRC has tested over ten episodes, where the average values of the important metrics are calculated.

We use the same simulation settings as described in [31], and some details are supplemented here. We assume that the locations of sensors are assigned uniformly at random in the unit square , and the residual energy of each sensor is randomly generated between 10 and 20 J. The moving speed of MC is 0.1 m/s, and the energy consumption rate of moving unit distance is 0.1 J/s. The rate at which MC charges the sensor is 1 J/s, and the time that the MC returns to the depot to charge itself is ignored here. The main simulation settings are provided in Table 4. In addition, the relevant data of the real-time energy consumption rate of the sensor are shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

The Parameters of the Simulation Settings.

Table 5.

Energy parameters of sensor.

After the network environment is initialized, we will conduct simulation training on the environment. Our implementation uses an experience replay buffer of . The size of the minibatch is 1024. As for the neural networks, all networks (separate policies and those contained within the centralized critic networks) use a hidden dimension of 128, and the Leaky Rectified Linear units are used as the nonlinear activation. We train our models with the Adam optimizer [44] and set different initial learning rates when the network size is different. The key parameters used in the training stage are described in Table 6.

Table 6.

Key Parameters of the Training Stage.

We have trained our model for three different environment settings on four NVIDIA GeForce GTX 2080ti for 10 h, after which the observed qualitative differences between the results of consecutive training iterations were ignored. We present one set of experimental results to describe the relationship between episodes and reward, which is shown in Figure 4. We can see that obtained rewards increase slowly through episodes to reach peak values after 240 training episodes. This is mainly caused by the efficient learning of AMADRL-JSSRC to the WRSN with dynamic energy changes so that agents could make reasonable decisions to obtain a greater reward.

Figure 4.

Reward per episode.

Since the reward discount factor and penalty coefficient have a great impact on the performance of the algorithm in the training and testing process, we have made two sets of experiments, and the results are shown in Table 7 and Table 8, respectively. These experimental results prove that AMADRL-JSSRC will strive for a long-term reward rather than a short-sight reward when the reward discount factor approaches 1. Furthermore, with the increase in the penalty coefficient, the number of dead sensors gradually decreases. The reason is that in order to obtain a high global charging reward, AMADRL-JSSRC preferentially charges the sensors with low residual energy to avoid sensor death when a large value is assigned to . Therefore, in this paper, the penalty coefficient is set as 10, and the reward discount factor is set as 0.9.

Table 7.

Impact of the reward discount ().

Table 8.

Impact of the penalty coefficient ().

4.2. Comparison Results against the Baselines

In this section, we compare the performance of the AMADRL-JSSRC with that of the ACRL algorithm, the GREEDY algorithm, the dynamic programming algorithm, and two typical online charging schemes algorithms NJNP and TSCA [16]. The detailed execution process of the above algorithms is shown in [31]. It is noted that some details of the baseline algorithms need to be adjusted. For example, we have replaced the reward calculation equation in line 13 of Algorithm 1, line 6 of Algorithm 2, and the line 10 of Algorithm 3 described in [31] with , and we change their seeking rule from the minimum global reward to the maximum global reward.

We consider three networks with different scales, including 50, 100, and 200 sensors; these environments are denoted as JSSRC50, JSSRC100, and JSSRC200. We have run our tests on WRSNs based on these environments, and the corresponding MC capacity is set as 50, 80, and 150 J. In addition, the base time of these three tests is set as 100 s, 200 s, and 300 s, respectively. Unless otherwise specified, these parameters are fixed during the test.

The tour length, the extra time, and the number of dead sensors obtained via different algorithms based on different JSSRC environments are shown in Table 9. It is observed that when the network size is small, such as the network with 50 sensors, the exact heuristic algorithm is better than AMADRL-JSSRC and ACRL algorithms in terms of average tour length and the average number of dead sensors. Meanwhile, the ACRL performance is slightly better than that of AMADRL-JSSRC at JSSRC 50. However, with the increase in network scale, the results of AMADRL-JSSRC and ACRL outperform the GREEDY, DP, JNJP, and TSCA significantly; the AMADRL-JSSRC and ACRL algorithms begin to show their superiority. The AMADRL-JSSRC algorithm is better than the ACRL algorithm, especially in the terms of the number of dead sensors. The reason for this phenomenon is that the charging ratio of the ACRL algorithm is fixed and cannot adjust adaptively according to the real-time charging demand, which will lead to some sensors becoming dead during the MC charging the selected sensors. The extra time comparisons are also presented in this table, where all the times are reported on one NVIDIA GeForce GTX 2080ti. We find that our proposed approach significantly improves the solution while only adding a small computational cost in runtime. Moreover, the extra time of AMADRL-JSSRC is longer than that of ACRL, verifying that multi-agent collaborative decision making consumes more computational cost.

Table 9.

The Results Based on Different Algorithms Over Test Set.

5. Discussions

The impacts of the parameters on the charging performance, including the capacity of the sensor and the capacity of MC, and the performance comparison in terms of lifetime are discussed in this section. The test environment is set as 100 sensors, the baseline time is 300 s, the initial capacity of the sensor is 50 J, and the initial capacity of MC is 100 J. Meanwhile, the initial residual energy of sensors will change with the capacity of sensors. Since the baseline algorithms do not have the ability to adaptively control the charging ratio for each sensor, for a fair comparison, we introduce the optimal charging ratio from Table 4, which is named the charging coefficient in [31]. Therefore, the charging ratio of the baseline algorithms are ACRL , GREEDY , DP , NJNP , and TSCA respectively.

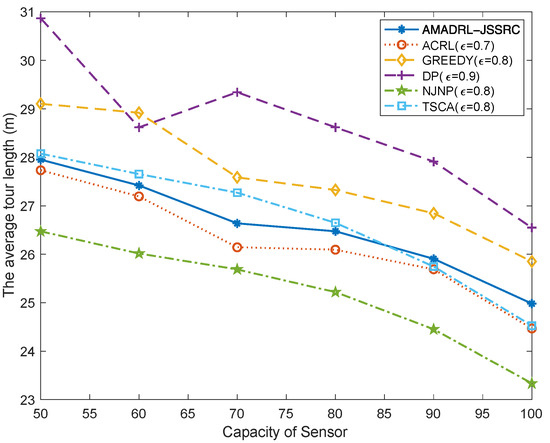

5.1. The Impacts of the Capacity of the Sensor

As depicted in Figure 5, NJNP has the lowest tour length, and the average tour length gradually decreases with the increase in the capacity of sensors. The reason is that with the increase in the capacity of the sensor, the number of sensors’ charging requests will decrease on the premise of sufficient residual energy. Moreover, the charging for each sensor is also prolonged due to the increase in sensor capacity. Based on the fixed baseline time, the more time the MC spends on charging sensors, the less time it will spend on moving. Therefore, the average tour length decreases gradually. The fluctuation in Figure 5 is caused by the random distribution of sensor positions and the dynamic change of their energy consumption rate in each test experiment. Furthermore, the NJNP algorithm has the lowest tour length is because it preferentially charges the sensors close to MC. It is noted that the moving distance of AMADRL-JSSRC is slightly longer than that of ACRL. This is because AMADRL-JSSRC can determine different charging ratios for the selected sensors according to the real-time charging demand to avoid the punishment caused by the dead sensors. Therefore, AMADRL-JSSRC spends slightly less time on charging than ACRL. When the base time is fixed, more time will be spent on moving, resulting in a longer moving distance.

Figure 5.

The impact of the capacity of the sensor on the average tour length.

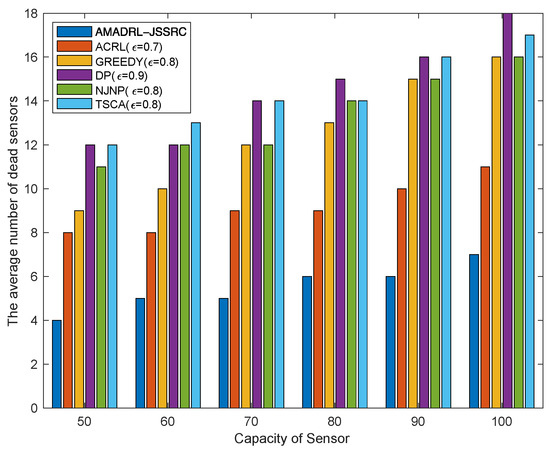

Figure 6 shows that with the increase in the capacity of the sensor, the average number of dead sensors shows an opposite change to the average tour length. Obviously, the average number of dead sensors of AMADRL-JSSRC is always the smallest. This is because the optimal charging ratios of the baseline algorithms are fixed, while the baseline algorithms are fixed. With the increase in the capacity of the sensor, the charging ratio for each selected sensor will be prolonged, increasing the risk of subsequent low residual energy sensor death. This result proves that the adaptive control of the charging ratio for each sensor could improve the charging performance effectively for the network.

Figure 6.

The impact of the capacity of the sensor on the average number of dead sensors.

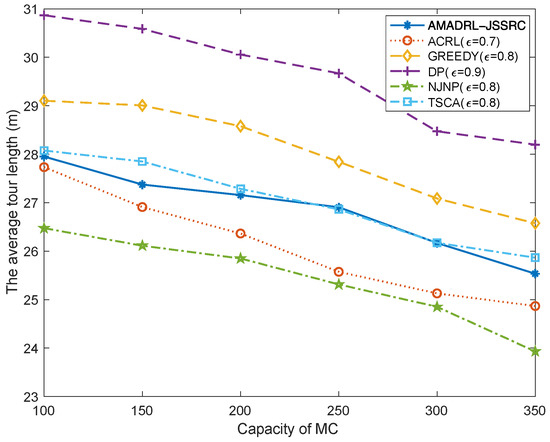

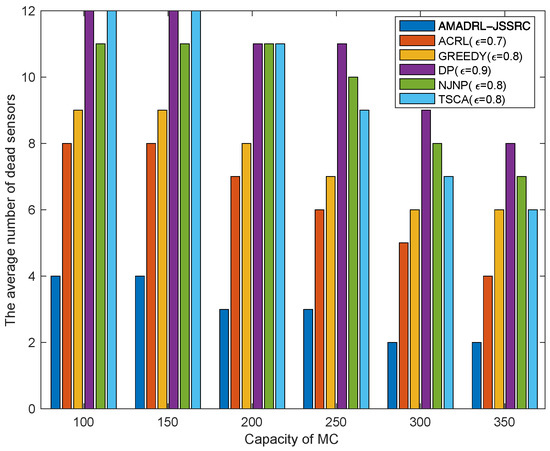

5.2. The Impacts of the Capacity of MC

Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the impacts of the capacity of MC change on the average tour length and the average number of dead sensors, respectively. With the increase in MC capacity, when the baseline time is fixed, the MC could reduce the time of returning to the depot to charge itself. This change could shorten the moving distance of the MC and decrease the risk of subsequent low residual energy sensor death when it returns to or leaves the depot. Meanwhile, figures verify that compared with the ACRL algorithm, AMADRL-JSSRC gains a smaller number of dead sensors at the cost of increasing a certain moving distance.

Figure 7.

The impact of capacity of MC on the average tour length.

Figure 8.

The impact of capacity of MC on the average number of dead sensors.

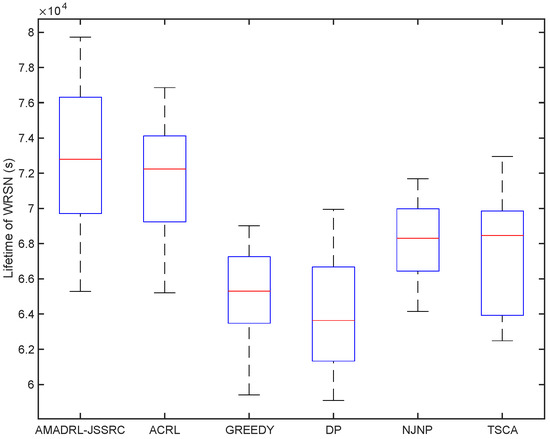

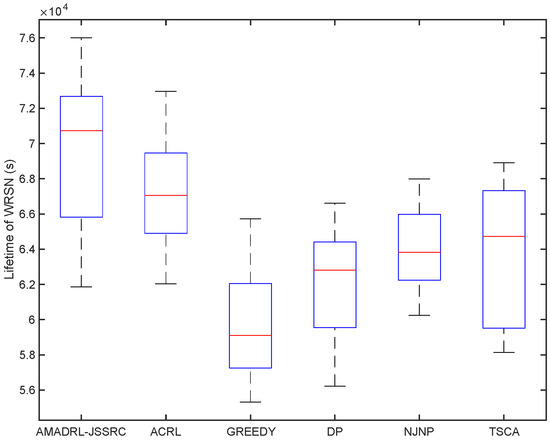

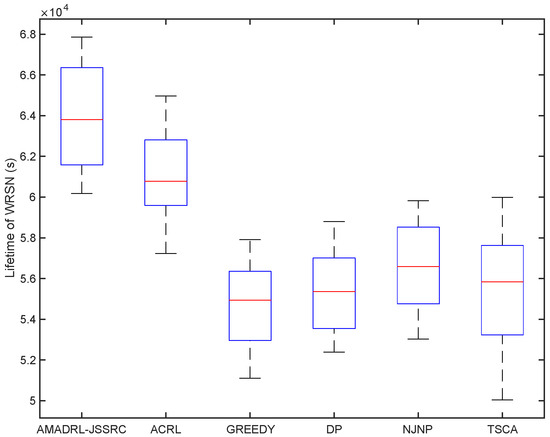

5.3. Performance Comparison in Terms of Lifetime

We have analyzed the test results of six schemes under the fixed baseline lifetime. In this section, we explore the lifetime of the six schemes under different JSSRCs, which are JSSRC50, JSSRC100, and JSSRC200, until the termination condition is satisfied. These six algorithms have run 50 times independently, and the test results are shown in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. It can be seen from the figure that although the fluctuation range of network lifetime obtained by the AMADRL-JSSRC algorithm is large, the lower and the upper bounds of network lifetime are still higher than the other five algorithms significantly. Moreover, with the increase in the number of sensors, this performance is outstanding significantly. It is noted that the network lifetime obtained by the AMADRL-JSSRC is better than the ACRL, which further proves that adjusting the charging ratio adaptively for each sensor could prolong the network lifetime effectively.

Figure 9.

The lifetime of different algorithms on JSSRC50.

Figure 10.

The lifetime of different algorithms on JSSRC100.

Figure 11.

The lifetime of different algorithms on JSSRC200.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, a novel joint charging sequence scheduling and charging ratio control problem is studied, and an attention-shared multi-agent actor–critic-based deep reinforcement learning approach (AMADRL-JSSRC) is proposed, where a charging sequence scheduler and a charging ratio controller are employed to determine the target sensor and charging ratio by interacting with the environment. AMADRL-JSSRC trains decentralized policies in multi-agent environments, using a centralized computing critic network to share an attention mechanism, and it selects relevant policy information for each agent. Meanwhile, the AMADRL-JSSRC performance significantly prolongs the lifetime of the WRSN and minimizes the number of dead sensors, and the performance is more significant when dealing with large-scale WRSNs. In future work, the multi-agent reinforcement learning approach for multiple MCs to complete the charging tasks jointly is the key point for further study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.J. and Z.W.; methodology, J.L.; data curation, S.C. and H.W.; investigation, J.X.; project administration, W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grant 62173032, Grant 62173028 and the Foshan Science and Technology Innovation Special Project under Grant BK20AF005.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, G.; Su, X.; Hong, F.; Zhong, X.; Liang, Z.; Wu, X.; Huang, Z. A Novel Epidemic Model Base on Pulse Charging in Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. Entropy 2022, 24, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayaz, M.; Ammad-Uddin, M.; Baig, I.; Aggoune, M. Wireless Sensor’s Civil Applications, Prototypes, and Future Integration Possibilities: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.; Aslam, N.; Le-Minh, H.; Hussain, S.; Cao, Y.; Khan, N.M. A Critical Analysis of Research Potential, Challenges, and Future Directives in Industrial Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2018, 20, 39–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Peng, Z.; Liang, Z.; Li, J.; Cheng, L. Dynamics Analysis of a Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Network for Virus Mutation Spreading. Entropy 2021, 23, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Huang, Z.; Wu, X.; Liang, Z.; Hong, F.; Su, X. Modelling and Analysis of the Epidemic Model under Pulse Charging in Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. Entropy 2021, 23, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Yu, G.; Pan, J.; Zhu, T. On-Demand Charging in Wireless Sensor Networks: Theories and Applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Mobile Ad-Hoc & Sensor Systems, Hangzhou, China, 14–16 October 2013; pp. 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. Stochastic Mobile Energy Replenishment and Adaptive Sensor Activation for Perpetual Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), Shanghai, China, 7–10 April 2013; pp. 974–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, N.; Wang, F.; Qian, Q.; Li, X. Starvation Avoidance Mobile Energy Replenishment for Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 22–27 May 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Xu, Z.; Xu, W.; Shi, J.; Mao, G.; Das, S.K. Approximation Algorithms for Charging Reward Maximization in Rechargeable Sensor Networks via a Mobile Charger. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2017, 25, 3161–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, W.; Qiao, D. Prolonging Sensor Network Lifetime through Wireless Charging. In Proceedings of the 2010 31st IEEE Real-Time Systems Symposium, RTSS 2010, San Diego, CA, USA, 30 November—3 December 2010; pp. 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Qiao, D. J-RoC: A Joint Routing and Charging Scheme to Prolong Sensor Network Lifetime. In Proceedings of the 2011 19th IEEE International Conference on Network Protocols, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–20 October 2011; pp. 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, F.; Zhao, Z.; Min, G.; Wu, Y. A Novel Approach for Path Plan of Mobile Chargers in Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 12th International Conference on Mobile Ad-Hoc and Sensor Networks (MSN), Hefei, China, 16–18 December 2016; pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, Z.; Yiwen, Z.; Shuaihua, M.; Xiaoyan, K.; Jianliang, G. RCSS: A Real-Time on-Demand Charging Scheduling Scheme for Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. Sensors 2018, 18, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, L.; Kong, L.; Gu, Y.; Pan, J.; Zhu, T. Evaluating the on-Demand Mobile Charging in Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2015, 14, 1861–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Han, D.; Deng, J.; Wu, G. P2S: A Primary and Passer-By Scheduling Algorithm for On-Demand Charging Architecture in Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 8047–8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, L.; Zhou, J.; Guo, C.; Song, H.; Obaidat, M.S. TSCA: A Temporal-Spatial Real-Time Charging Scheduling Algorithm for on-Demand Architecture in Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2018, 17, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Goswami, P.; Mukherjee, A.; Yang, L.; Routray, S.; Palai, G. Low-Energy PSO-Based Node Positioning in Optical Wireless Sensor Networks. Opt.-Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 2018, 181, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Shin, K.G.; Chen, J.; Sun, Y. Joint Energy Replenishment and Operation Scheduling in Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017, 13, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Han, G.; Kang, Y.; Wang, J. A Newborn Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Charging-Scheduling Algorithm in Industrial Rechargeable Sensor Networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 11014–11027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawra, V.K.; Gupta, G.P. Correction to: Hybrid Meta-Heuristic Techniques Based Efficient Charging Scheduling Scheme for Multiple Mobile Wireless Chargers Based Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. Peer-Peer Netw. Appl. 2021, 14, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Lu, S. Collaborative Mobile Charging. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2015, 64, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Xu, W.; Ren, X.; Jia, X.; Lin, X. Maintaining Large-Scale Rechargeable Sensor Networks Perpetually via Multiple Mobile Charging Vehicles. ACM Trans. Sens. Netw. 2016, 12, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Collaborative Mobile Charging and Coverage. J. Comp. Sci. Technol. 2014, 29, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhja, A.; Nikoletseas, S.; Raptis, T.P. Hierarchical, Collaborative Wireless Charging in Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 9–12 March 2015; pp. 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Guo, L.; Fu, X.; Liu, N. Efficient Mobile Energy Replenishment Scheme Based on Hybrid Mode for Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2019, 19, 10131–10143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaswan, A.; Tomar, A.; Jana, P.K. An Efficient Scheduling Scheme for Mobile Charger in on-Demand Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2018, 114, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, A.; Muduli, L.; Jana, P.K. A Fuzzy Logic-Based On-Demand Charging Algorithm for Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks with Multiple Chargers. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2021, 20, 2715–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Peng, J.; Liu, T. A Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based on-Demand Charging Algorithm for Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2021, 110, 102278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Liu, F.; Lyu, Z.; Ding, X.; Shi, L.; Xia, C. Reinforcement Learning for a Novel Mobile Charging Strategy in Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. In Wireless Algorithms, Systems, and Applications; Chellappan, S., Cheng, W., Li, W., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Shrivastava, M. Novel Wireless Charging Algorithms to Charge Mobile Wireless Sensor Network by Using Reinforcement Learning. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, M.; Liu, N.; Zuo, L.; Feng, Y.; Liu, M.; Gong, H.; Liu, M. Dynamic Charging Scheme Problem with Actor-Critic Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Shi, Y.; Hou, Y.T.; Sherali, H.D. Making Sensor Networks Immortal: An Energy-Renewal Approach with Wireless energy transmission. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2012, 20, 1748–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.T.; Shi, Y.; Sherali, H.D. Rate Allocation and Network Lifetime Problems for Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2008, 16, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Yousefi, H.; Cheng, P.; Chen, J.; Gu, Y.J.; He, T.; Shin, K.G. Near-Optimal Velocity Control for Mobile Charging in Wireless Rechargeable Sensor Networks. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2016, 15, 1699–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Littman, M.L. Markov Games as a Framework for Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. In Machine Learning Proceeding 1994; Cohen, W.W., Hirsh, H., Eds.; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lowe, R.; Wu, Y.; Tamar, A.; Harb, J. Multi-Agent Actor-Critic for Mixed Cooperative-Competitive Environments. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.02275 (accessed on 7 June 2017).

- Yu, C.; Velu, A.; Vinitsky, E.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y. The Surprising Effectiveness of PPO in Cooperative, Multi-Agent Games. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.01955 (accessed on 2 March 2021).

- Graves, A.; Wayne, G.; Danihelka, I. Neural Turing Machines. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1410.5401v1 (accessed on 20 October 2014).

- Oh, J.; Chockalingam, V.; Singh, S.; Lee, H. Control of Memory, Active Perception, and Action in Minecraft. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1605.09128 (accessed on 30 May 2016).

- Foerster, J.; Farquhar, G.; Afouras, T.; Nardelli, N.; Whiteson, S. Counterfactual Multi-Agent Policy Gradients. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1705.08926 (accessed on 24 May 2017).

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762. (accessed on 12 June 2017).

- Iqbal, S.; Sha, F. Actor-Attention-Critic for Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.02912 (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- Wei, E.; Wicke, D.; Freelan, D.; Luke, S. Multiagent Soft Q-Learning. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.09817 (accessed on 25 April 2018).

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6980 (accessed on 22 December 2014).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).