Abstract

Perilla, also termed as purple mint, Chinese basil, or Perilla mint, is a flavoring herb widely used in East Asia. Both crude oil and essential oil are employed for consumption as well as industrial purposes. Fatty acids (FAs) biosynthesis and oil body assemblies in Perilla have been extensively investigated over the last three decades. Recent advances have been made in order to reveal the enzymes involved in the fatty acid biosynthesis in Perilla. Among those fatty acids, alpha-linolenic acid retained the attention of scientists mainly due to its medicinal and nutraceutical properties. Lipids synthesis in Perilla exhibited similarities with Arabidopsis thaliana lipids’ pathway. The homologous coding genes for polyunsaturated fatty acid desaturases, transcription factors, and major acyl-related enzymes have been found in Perilla via de novo transcriptome profiling, genome-wide association study, and in silico whole-genome screening. The identified genes covered de novo fatty acid synthesis, acyl-CoA dependent Kennedy pathway, acyl-CoA independent pathway, Triacylglycerols (TAGs) assembly, and acyl editing of phosphatidylcholine. In addition to the enzymes, transcription factors including WRINKLED, FUSCA3, LEAFY COTYLEDON1, and ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE3 have been suggested. Meanwhile, the epigenome aspect impacting the transcriptional regulation of FAs is still unclear and might require more attention from the scientific community. This review mainly outlines the identification of the key gene master players involved in Perilla FAs biosynthesis and TAGs assembly that have been identified in recent years. With the recent advances in genomics resources regarding this orphan crop, we provided an updated overview of the recent contributions into the comprehension of the genetic background of fatty acid biosynthesis. The provided resources can be useful for further usage in oil-bioengineering and the design of alpha-linolenic acid-boosted Perilla genotypes in the future.

1. Introduction

Perilla frutescens var. frutescens is an oil crop from the mint family that is widely distributed in East Asia including India, Vietnam, China, and Korea [1]. The Perilla genetic resource encompasses the oil crop type P. frutescens var. frutescens, the weedy/wild type P. frutescens, and wild species Perilla setoyensis, Perilla hirtella, and Perilla citriodora [2]. While P. citriodora is known as one of the diploid progenitors [3] of tetraploid P. frutescens, the second diploid donor has not yet been elucidated. In Korean dietary habits, P. frutescens var. frutescens is used for its oil and as leafy vegetable. The fresh leaves can serve as a wrap for meat and boiled rice and are also prepared in a pickled form [2]. In China, where it originated [1,2], Perilla is used secularly as a traditional herbal medicine and fragrance [2]. The health-promoting properties of this plant are attributable to its wide panel of phytochemical compounds [4]. Among them, fatty acids including omega-3, -6, and -9 have been reported as anti-cancer agents [5,6,7], coronary heart-disease protectants [8], anti-diabetic agents [9], insulin-resistant [10], anti-cardiovascular disease agents [11], and anti-depressive agents [12,13,14]. In addition, preclinical tests revealed the positive effect of Perilla for mitigating moderate dementia [15]. However, further investigations are required to confirm its role before a recommendation for its use as an antioxidative complement for patients with dementia [4,15]. In addition, Perilla is also used as a supplement in animal feeding [16,17]. Due to the numerous applications of fatty acids from Perilla in the health industry, the oil industry, and for animal breeding, a comprehensive background underpins fatty acid biosynthesis as a fundamental prerequisite for proper utilization in the biomedical, bioengineering, and animal industries.

Recently, Perilla entered into the genomics era with the sequencing of tetraploid P. frutescence and one diploid donor P. citriodora [3], laying a foundation for unraveling the genetic basis of its multiple health and nutraceutical benefits. In the present review, we will examine recent breakthroughs on the genetic basis of fatty acid biosynthesis in Perilla.

2. Earlier Identification and Cloning of Fatty Acid Encoding Gene in Perilla

The genetic characterization interest for Perilla as an oil crop with numerous health beneficial attributes started as early as the 1900s. Several fatty acid genes have been cloned and functionally characterized. Lee et al. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/U59477.1/, accessed on 12 February 2021) first characterized a ω-3 fatty acid desaturase PfrFAD7 (Genbank accession: U59477.1) extracted from a Korean cultivar “Okdong” seedling. Subsequently, a cloning of a second gene PrFAD3 was conducted by Chung et al. [18]. PrFAD3 exhibited a seed-specific expression when compared to other organs including the leaf, stem, and root, suggesting a preferential accumulation of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) in the seed.

Hwang et al. [19,20] also reported four 3-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthases (KAS) encoding genes, PfKAS3a (KAS III) and PfKAS3b (KAS III), PfFAB1 (KAS I), and PfFAB24 (KAS II/IV), which were responsible in the high accumulation of alpha-linolenic synthesis in P. frutescens seeds. Another alpha-linolenic acid-related gene, the microsomal oleate 12-desaturase (PfFAD2) gene, was functionally characterized for the first time in P. frutescens var. frutescens seed [21] in later studies. In addition to the previously identified FAD3 and FAD7 type genes, Xue et al. [22] isolated two FAD8 alpha-linoleic-related genes (PrFAD8a and PrFADb) harboring two pyrimidine stretches. Interestingly, the expression of PrFAD8 genes was predominantly observed in the Perilla bud while its accumulation increased under injury, Methyl jasmonate (MeJA), Salicylic Acid (SA), and Abscisic acid (ABA) effects; highlighting their implications in plant defense, growth, and development.

3. Transcriptomics Sheds Lights into Key Master Player Enzymes of Perilla Fatty Acid Biosynthesis

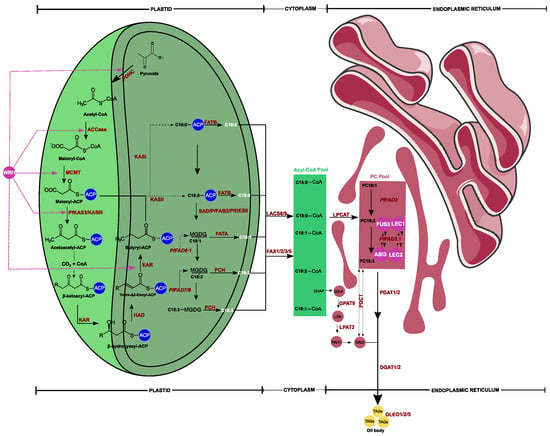

Although some genes have been investigated earlier, the fully resolved biosynthesis pathway of fatty acids in Perilla was still unclear. To fill this gap, the RNA sequencing approach has been extensively used because it helps in uncovering expressed genes related to a biological process. By deciphering the transcriptome of Perilla using diverse organs, scientists were able to identify key genes related to fatty acid biosynthesis via de novo transcripts assembly and functional gene prediction. Thus, extensive transcriptome studies have been initiated using different materials, including P. fruescens var. frutescens, Perilla frutescens var. crispa f. purpurea (red Perilla), and P. frutescens var. crispa f. viridis (green Perilla) [23,24,25,26]. The uncovered key genes involved in fatty acid biosynthesis in Perilla have been summarized in Figure 1. Briefly, based on Perilla’s fatty acid desaturase subcellular localization prediction [27] and the well-studied Arabidopsis fatty acid biosynthesis model [28], most fatty acids, including palmitic acid (C16:0), stearic acid (C18:0), and oleic acid (C18:1), were exclusively synthesized in plastids and conveyed into the cytoplasm where they entered into an acyl-CoA pool for the esterification process at sn-2 position resulting in phosphatidylcholine under the acyl-CoA:lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase (LPCAT) enzyme effect.

Figure 1.

A simplified putative diagram view of fatty acids biosynthetic pathway in Perilla and triacylglycerols (TAGs) assembly. The schematic view involved bio-chemical interactions occurring in plastid, cytoplasm, and endoplasmic reticulum, respectively. The resulting TAGs are indicated in yellow. Purple circles indicate transcription factors, including WRINKLED (WRI1), FUSCA3 (FUS3), LEAFY COTYLEDON1 (LEC1, LCE2), and ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE3 (ABI3). The transcriptional regulation of FUS3, LCE1, LCE2, and ABI3 with PfFAD3.1 is not yet uncovered. PDHC: plastidial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; ACCase: acetyl-CoA carboxylase; MCMT: malonyl-CoA ACP transacylase; KASIII: ketoacyl-ACP synthase type III; KAR: 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase; HAD: 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP dyhydratase; EAR: 2-enoyl-ACP reductase; KASII: ketoacyl-ACP synthase type II; KASI: ketoacyl-ACP synthase type I; SAD: stearoyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase; FATB: acyl-ACP thioesterase B; FATA: acyl-ACP thioesterase A; MGDG: monogalactosyldiacylglycerol; PfFAD: Perilla frutescens fatty acid desaturase; PC Pool: phosphatidylcholines pool; PCH: palmitoyl-CoA hydrolase; LACS: long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase; PDCT: phosphatidylcholinediacylglycerol cholinephosphotransferase; FAX: fatty acid export; LPCAT: lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase; PDAT: phospholipid diacylglycerol acyltransferase; DGAT: diacylglycerolacyltransferase; GPAT: glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase; LPAT: 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase; DHAP: dihydroxyacetone phosphate; PAH: phosphatidic acid phosphatase; OLEO: Oleosin.

Oleic acid was then desaturated in the endoplastic rediculum (ER) to become consecutively linoleic acid (LA) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) under FAD2 and FAD3 genes, respectively. The resulting polyunsaturated fatty acids were transacylated onto the sn-3 position of diacylglycerol by phospholipid:diacylglycerol acyltransferase (PDAT) or returned to the acyl-CoA pool via LPCAT to be incorporated into TAG through the Kennedy pathway, inducing the production of triacylglycerols (TAGs) [29].

Using Perilla as a plant model, numerous fatty acid-related genes have been identified. From a time-course seed transcriptome analysis, Kim et al. [25] identified 43 acyl-lipid related genes in P. frutescens var. frutescens cv. Dayudeulkkae (Table 1). The identified genes via Arabidopsis orthologs detection covered the de novo fatty acid biosynthetic key enzymes present in the plastid, endoplasmic reticulum desaturases, oil body proteins, acyl-CoA-, and phosphatidylcholine-mediated TAG synthesis.

Table 1.

Summary of Identified Major Genes Involved in Fatty Acid and Triacylglycerols Biosynthesis in Perilla.

Transcriptome mining revealed five sub-unit genes (α-PDH, β-PDH, EMB3003, LTA2, and LPD1) of the precursor enzyme plastidial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHC) involved in the synthesis of acetyl-CoA from pyruvate. Afterward, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase) transformed acetyl-CoA ito malonyl-CoA [30]. The ACCase in Perilla encompassed two ACCases subunits alpha (α-CTa and α-CTb), one ACCase subunit beta (β-CT), two isoforms of biotin carboxyl-carrier protein (BCCP1 and BCCP2), and one biotin carboxylase (BC).

Furthermore, the malonyl-CoA ACP transacylase, an acyl carrier protein transacylase, catalyzed malonyl-CoA to form malonyl-ACP, paving the way for fatty acid elongation under the action of acyl-chain enzymes, i.e., 3-keto-acyl-ACP synthase (KAS), 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase (KAR), 3-hydroxylacyl-ACP dehydratase (HAD), and Trans-∆2-enoyl-ACP reductase (EAR), respectively [23,24,31]. It is worth mentioning that WR1 is well conserved in plant species. For instance, homologous genes have been identified in Brachypodium distachyon [32], Camelina sativa [33], Solanum tuberosum [34], Cocos nucifera [35], Brassica napus [36], Elaeis guineensis [37], and Jatropha curcas [38]. In A. thaliana, through the promoter binding element AW-box, WRI1 targets upstream genes encoding for malonyl-CoA:ACP malonyl transferase, enoyl-ACP reductase, pyruvate dehydrogenase, oleoyl-ACP thioesterase, biotin carboxyl carrier protein 2, ketoacyl-ACP synthase, and hydroxyacyl-ACP dehydrase [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. The homologous sequence of WR1 has been demonstrated in augmentation from 10 to 40% of seed oil in transgenic maize [47] and Brassica napus [36], suggesting that Perilla’s WR1 gene might be a promising candidate for oil-oriented bioengineering in Perilla.

Through carbon chain elongation, palmitoyl-ACP (C16:0) is converted into stearoyl-ACP (C18:0). The latter is transformed into oleic acid (C18:1)-ACP under the catalysis of stearoyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase (SAD). In Perilla, two SAD genes have been identified, including PfFAB2 and PfDES6 [25]. Using a red Perilla (Perilla frutescens var. crispa F. purpurea) seed transcriptome, Liao et al. [23] identified fatty acid desaturases PfFAD6 and PfFAD7/8 that act on the vector glycerolipid, i.e., monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG), in order to process (C18:1) into (C18:2) and (C18:2) to (C18:3), respectively (Figure 1).

To terminate fatty acids synthesis in Perilla plastids, fatty acyl-ACP thioesterase (FATA), palmitoyl/stearoyl-acyl carrier protein thioesterase (FATB), and palmitoyl-CoA hydrolase (PCH) were solicitated. PCH specifically induced C18:1- and C18:2-synthesis, while FATA was a C18:1-exclusive catalyst. Meanwhile, FATB transformed only C16:0-ACP or C18:0-ACP to C16:0 or C18:0, respectively (Figure 1). Representative gene coding for these enzyme has been pinpointed by de novo transcriptome analysis and comparative transcripts with regard to the well characterized A. thaliana fatty acid-related gene [23,24]. Free FAs were then moved into the cytoplasm where they were esterified to form an Acyl-CoA pool under the action of long-chain acyl-COA synthesis (LACS). Liao et al. [23] reported the important expression of LACS genes in Perilla seeds ten days after flowering, indicating an initiation of TAGs synthesis pathway in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

In the ER, esterified fatty acids are translated into phosphatidylcholines via lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase (LPCAT). Based on the Arabidopsis plant model, mainly two fatty acid desaturases have been identified in the ER: an FAD2 that converts PC-C18:1 into PC-18:2 and an FAD3 that catalyzes PC-C18:2 into PC-C18:3 [48,49,50]. Homologous sequences in Perilla seed (PfFAD2 and PfFAD3) transcriptome [23,24,25] have also been identified (Table 1).

Recently, the transcriptome assessment of Chinese cultivar PF40 highlighted 33 candidate genes involved in TAG biosynthesis-covering transcription factors (Supplementary Table S1), and fatty acids were exported from plastid, acyl editing of phospatidylcholine, acyl-CoA dependent Kennedy pathway, acyl-CoA independent pathway, and TAGs assembly into oil bodies (Table 1). The identified genes corroborated with previous findings [23,24,25], except for the first identification of fatty export1 (FAX1) as an additional enzyme to long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (LACS) that mediated plastid fatty acid export.

In the absence of a whole genome representative resources, the detection of potential genes isoforms and the full FADs gene repertoire is difficult to predict, and diverse gene targets for functional validation and bio-engineering purposes are not provided. Due to the fact that Perilla has entered into the genomics era, the next section covers genomics-based advances in the detection of fatty acids in Perilla via genome-wide identification and genome-wide association study strategies.

4. Whole-Genome-Driven Fatty Acid Genes Discovery

With the advent of long-reads and chromosome conformation capture technologies, a high-quality chromosome scale genome of tetraploid P. frutescens var. frutescens has recently been assembled [3]. The genome spanned 1.203 Gb, along with 20 chromosomes with an N50 of 62.64 Mb and a total of 38,941 predicted gene models.

From a panel of 191 accessions, a genome-wide association study for seed alpha-linolenic acid content enabled the identification of an LPCAT encoding region located in chromosome 2. This finding corroborates previous observations, suggesting the role of LPCAT in FAs and TAGs synthesis in B. napus [51] and A. thaliana [52]. Interestingly, a deletion of this gene was noted in some individuals of the studied panel corresponding to a loss of around 6% of seed oil ALA content. This suggests that the transcriptional regulation of LPCAT might be responsible for ALA content variations in Perilla.

Taking advantage of the PF40-generated high-quality genome, in silico genome-wide analysis identified a repertoire of 42 fatty acid desaturases clustered into five families including omega-3 desaturase, ∆7/∆9 desaturase, FAD4 desaturase, ∆12 desaturase, and front-end desaturase [27]. The heterologous validation of candidate fatty acid desaturase genes using A. thaliana revealed a positive impact (increase of 18–37% alpha-linolenic acid content) of the PfFAD3.1 gene.

Furthermore, the upregulation of WRINKLED (WRI1), FUSCA3 (FUS3), LEAFY COTYLEDON1 (LEC1 and LCE2), and ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE3 (ABI3) transcription factors was noted in PfFAD3.1 Arabidopsis transgenic lines [3] and Perilla seed expression profiles [23], suggesting their regulation roles in the Perilla FAs synthesis pathway.

5. Concluding Remarks and Outlook

Fatty acids play an important role in the lipid supply of plants and have valuable medicinal properties for humans. Here, we summarized the breakthroughs that shed light into the genetic and molecular determinants of FA and TAG synthesis in Perilla. Transcriptomics and genomics studies revealed the key master player enzymes responsible for FAs synthesis in Perilla, including polyunsaturated fatty acids desaturases, acyl-related enzymes, and transcription factors. However, the evidence of their role is still elusive since strong functional validation has not yet been provided.

The mechanism of the regulation of FA synthesis by TFs in Perilla is still elusive. Meanwhile, the recent work from Moreno-Perez et al. [53] suggested histone methylation (H3K4me3) implication into fatty acid biosynthesis in sunflowers with interactions with TFs. Moreover, acetyl-CoA, which is involved in fatty acid synthesis in plants, has been found to be correlated with histone acetylation and DNA methylation in A. thaliana through the beta-oxidation process [54]. Therefore, an in-depth investigation of identified TFs, such as ABI3, FUS3, LEC1, and LEC2, and the epigenome landmark of Perilla will pave a new avenue in deciphering the full landscape of fatty-acid biosynthesis in Perilla.

Functional validation using Perilla as a material instead of A. thaliana would drastically shape the validation efficiency of the identified genes. For this purpose, Agrobacterium-based protocols [55,56] have been tested and can serve as further functional validation. Moreover, in the current era of gene and genome editing with applicable cases in plants [57,58,59,60], designing appropriate gene editing strategies that fit into the Perilla system will surely expedite the production of enriched alpha-linolenic acid-Perilla genotypes. Furthermore, considering the species diversity within the Perilla genus, systematic fatty acid content evaluation within the Perilla species will help reveal potential alpha-linolenic acid-enriched species donors and characterize their respective biosynthetic pathways.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants11091207/s1, Table S1: Identified transcription factors from Perilla through trancriptome, whole genome, and in silico co-expression analyses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-H.B.; methodology, S.-H.B. and Y.A.B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-H.B., Y.A.B.Z. and T.S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.-H.B., J.-H.O., J.L., T.-H.K. and K.Y.P.; visualization, Y.A.B.Z.; supervision, J.L., T.-H.K. and K.Y.P.; funding acquisition, K.Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Table S1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nitta, M.; Lee, J.K.; Kang, C.W.; Katsuta, M.; Yasumoto, S.; Liu, D.; Nagamine, T.; Ohnishi, O. The Distribution of Perilla Species. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2005, 52, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, M.; Lee, J.K.; Ohnishi, O. Asian Perilla crops and their weedy forms: Their cultivation, utilization and genetic relationships. Econ. Bot. 2003, 57, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, Q.; Leng, L.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S.; Shi, Y.; Ning, Z.; Chen, S. Incipient diploidization of the medicinal plant Perilla within 10,000 years. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.M. Ethnomedicinal, phytochemical and pharmacological investigations of Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. Molecules 2019, 24, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banno, N.; Akihisa, T.; Tokuda, H.; Yasukawa, K.; Higashihara, H.; Ukiya, M.; Watanabe, K.; Kimura, Y.; Hasegawa, J.I.; Nishino, H. Triterpene acids from the leaves of Perilla frutescens and their anti-inflammatory and antitumor-promoting effects. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004, 68, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narisawa, T.; Takahashi, M.; Kotanagi, H.; Kusaka, H.; Yamazaki, Y.; Koyama, H.; Fukaura, Y.; Nishizawa, Y.; Kotsugai, M.; Isoda, Y.; et al. Inhibitory Effect of Dietary Perilla Oil Rich in the n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid α-Linolenic Acid on Colon Carcinogenesis in Rats. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 1991, 82, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.S.; Kuo, C.L.; Wang, J.P.; Cheng, J.S.; Huang, Z.W.; Chen, C.F. Growth inhibitory and apoptosis inducing effect of Perilla frutescens extract on human hepatoma HepG2 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007, 112, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijendran, V.; Hayes, K.C. Dietary n-6 and n-3 fatty acid balance and cardiovascular health. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2004, 24, 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, H.; Hu, M.; Wang, J.; Xia, H.; Yang, X.; Yang, L.; Sun, G. Perilla Oil Supplementation Improves Hypertriglyceridemia and Gut Dysbiosis in Diabetic KKAy Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1800299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhao, S.; Li, W.; Ma, L.; Ding, M.; Li, R.; Liu, Y. High-fat diet from perilla oil induces insulin resistance despite lower serum lipids and increases hepatic fatty acid oxidation in rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2014, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradee, N.; Utama-ang, N.; Uthaipibull, C.; Porter, J.B.; Garbowski, M.W.; Srichairatanakool, S. Extracts of Thai Perilla frutescens nutlets attenuate tumour necrosis factor-α-activated generation of microparticles, ICAM-1 and IL-6 in human endothelial cells. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, T.; Yasuda, T.; Ueda, J.; Ohsawa, K. Antidepressant-like effects of apigenin and 2,4,5-trimethoxycinnamic acid from Perilla frutescens in the forced swimming test. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 26, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, H.; Tsuji, M.; Inazu, M.; Egashira, T.; Matsumiya, T. Rosmarinic acid and caffeic acid produce antidepressive-like effect in the forced swimming test in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 449, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, H.; Tsuji, M.; Miyamoto, J.; Matsumiya, T. Rosmarinic acid and caffeic acid reduce the defensive freezing behavior of mice exposed to conditioned fear stress. Psychopharmacology 2002, 164, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamalashiran, C.; Pattaraarchachai, J.; Muengtaweepongsa, S. Feasibility and Safety of Perilla Seed Oil as an Additional Antioxidative Therapy in Patients with Mild to Moderate Dementia. J. Aging Res. 2018, 2018, 5302105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Gou, Z.; Fan, Q.; Li, L.; Lin, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, Z. Effects of dietary perilla seed oil supplementation on lipid metabolism, meat quality, and fatty acid profiles in Yellow-feathered chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 5714–5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiretti, P.G.; Gasco, L.; Brugiapaglia, A.; Gai, F. Effects of perilla (Perilla frutescens L.) seeds supplementation on performance, carcass characteristics, meat quality and fatty acid composition of rabbits. Livest. Sci. 2011, 138, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.-H.; Kim, J.-L.; Lee, Y.-C.; Choi, Y.-L. Cloning and Characterization of a Seed-Specific -3 Fatty Acid Desaturase cDNA from Perilla frutescens. Plant Cell Physiol. 1999, 40, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hwang, S.K.; Hwang, Y.S. Molecular cloning and functional expression of Perilla frutescens 3-ketoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) synthase III. Mol. Cells 2000, 10, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.K.; Kim, K.H.; Hwang, Y.S. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of 3-ketoacyl-ACP synthases in the immature seeds of Perilla frutescens. Mol. Cells 2000, 10, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-R.; Lee, Y.; Kim, E.-H.; Lee, S.-B.; Roh, K.H.; Kim, J.-B.; Kang, H.-C.; Kim, H.U. Functional identification of oleate 12-desaturase and ω-3 fatty acid desaturase genes from Perilla frutescens var. frutescens. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 2523–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Chen, B.; Win, A.N.; Fu, C.; Lian, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X.; Chai, Y. Omega-3 fatty acid desaturase gene family from two ω-3 sources, Salvia hispanica and Perilla frutescens: Cloning, characterization and expression. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, B.N.; Hao, Y.J.; Lu, J.X.; Bai, H.Y.; Guan, L.; Zhang, T. Transcriptomic analysis of Perilla frutescens seed to insight into the biosynthesis and metabolic of unsaturated fatty acids. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Song, C.; Song, L.; Shang, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhang, D.; Sun, W.; Shen, Q.; Zhao, D. RNA sequencing and coexpression analysis reveal key genes involved in α-linolenic acid biosynthesis in Perilla frutescens seed. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.U.; Lee, K.R.; Shim, D.; Lee, J.H.; Chen, G.Q.; Hwang, S. Transcriptome analysis and identification of genes associated with ω-3 fatty acid biosynthesis in Perilla frutescens (L.) var. frutescens. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, A.; Nakamura, M.; Suzuki, H.; Saito, K.; Yamazaki, M. High-throughput sequencing and de novo assembly of red and green forms of the Perilla frutescens var. crispa transcriptome. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Shi-Mei, Y.; Zhi-Wei, S.; Jing, X.; De-Gang, Z.; Hong-Bin, W.; Qi, S. Genome-Wide Analysis of the Fatty Acid Desaturase Gene Family Reveals the Key Role of PfFAD3 in α-Linolenic Acid Biosynthesis in Perilla Seeds. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 735862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liping, W.; Shen, W.; Kazachkov, M.; Chen, G.; Chen, Q.; Carlsson, A.S.; Stymne, S.; Weselake, R.J.; Zou, J. Metabolic interactions between the lands cycle and the kennedy pathway of glycerolipid synthesis in arabidopsis developing seeds. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 4652–4669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, P.D.; Fatihi, A.; Snapp, A.R.; Carlsson, A.S.; Browse, J.; Lu, C. Acyl editing and headgroup exchange are the major mechanisms that direct polyunsaturated fatty acid flux into triacylglycerols. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 1530–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, T.; Shinohara, K.; Yamada, K.; Sasaki, Y. Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase in Higher Plants: Most Plants Other Than Gramineae Have Both the Prokaryotic and the Eukaryotic Forms of This Enzyme. Plant Cell Physiol. 1996, 37, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.H.; Kim, R.J.; Kim, K.J.; Lee, D.H.; Suh, M.C. Plastidial and mitochondrial malonyl CoA-ACP malonyltransferase is essential for cell division and its overexpression increases storage oil content. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Munz, J.; Cass, C.; Zienkiewicz, A.; Kong, Q.; Ma, W.; Sanjaya, S.; Sedbrook, J.C.; Benning, C. Ectopic expression of WRI1 affects fatty acid homeostasis in Brachypodium distachyon vegetative tissues. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1836–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Kim, H.; Ju, S.; Go, Y.S.; Kim, H.U.; Suh, M.C. Expression of Camelina WRINKLED1 Isoforms Rescue the Seed Phenotype of the Arabidopsis wri1 Mutant and Increase the Triacylglycerol Content in Tobacco Leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimberg, Å.; Carlsson, A.S.; Marttila, S.; Bhalerao, R.; Hofvander, P. Transcriptional transitions in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves upon induction of oil synthesis by WRINKLED1 homologs from diverse species and tissues. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, R.; Ye, R.; Gao, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, R.; Mao, T.; Zheng, Y.; Li, D.; Lin, Y. Characterization and Ectopic Expression of CoWRI1, an AP2/EREBP Domain-Containing Transcription Factor from Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) Endosperm, Changes the Seeds Oil Content in Transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana and Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Hua, W.; Zhan, G.; Wei, F.; Wang, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, H. Increasing seed mass and oil content in transgenic Arabidopsis by the overexpression of wri1-like gene from Brassica napus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Kong, Q.; Arondel, V.; Kilaru, A.; Bates, P.D.; Thrower, N.A.; Benning, C.; Ohlrogge, J.B. WRINKLED1, A Ubiquitous Regulator in Oil Accumulating Tissues from Arabidopsis Embryos to Oil Palm Mesocarp. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yu, C.; Yan, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, F.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, W. Overexpression of the Jatropha curcas JcERF1 gene coding an AP2/ERF-Type transcription factor increases tolerance to salt in transgenic tobacco. Biochemistry 2014, 79, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, S.; Mendoza, M.S.; To, A.; Harscoët, E.; Lepiniec, L.; Dubreucq, B. WRINKLED1 specifies the regulatory action of LEAFY COTYLEDON2 towards fatty acid metabolism during seed maturation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007, 50, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, N.; Ikawa, Y.; Aoyagi, T.; Kozaki, A. Expression of the genes coding for plastidic acetyl-CoA carboxylase subunits is regulated by a location-sensitive transcription factor binding site. Plant Mol. Biol. 2013, 82, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazaz, S.; Barthole, G.; Domergue, F.; Ettaki, H.; To, A.; Vasselon, D.; de Vos, D.; Belcram, K.; Lepiniec, L.; Baud, S. Differential activation of partially redundant Δ9 stearoyl-ACP desaturase genes is critical for omega-9 monounsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis during seed development in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3613–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Shao, J.; Tang, S.; Shen, Q.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Hong, Y. Wrinkled1 accelerates flowering and regulates lipid homeostasis between oil accumulation and membrane lipid anabolism in Brassica napus. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhai, Z.; Kuczynski, K.; Keereetaweep, J.; Schwender, J.; Shanklin, J. Wrinkled1 regulates biotin attachment domain-containing proteins that inhibit fatty acid synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2019, 181, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeo, K.; Tokuda, T.; Ayame, A.; Mitsui, N.; Kawai, T.; Tsukagoshi, H.; Ishiguro, S.; Nakamura, K. An AP2-type transcription factor, WRINKLED1, of Arabidopsis thaliana binds to the AW-box sequence conserved among proximal upstream regions of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis. Plant J. 2009, 60, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouvreau, B.; Baud, S.; Vernoud, V.; Morin, V.; Py, C.; Gendrot, G.; Pichon, J.P.; Rouster, J.; Paul, W.; Rogowsky, P.M. Duplicate maize wrinkled1 transcription factors activate target genes involved in seed oil biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruuska, S.A.; Girke, T.; Benning, C.; Ohlrogge, J.B. Contrapuntal networks of gene expression during Arabidopsis seed fillingW. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 1191–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Allen, W.B.; Zheng, P.; Li, C.; Glassman, K.; Ranch, J.; Nubel, D.; Tarczynski, M.C. Expression of ZmLEC1 and ZmWRI1 increases seed oil production in maize. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browse, J.; McConn, M.; James, D.; Miquel, M. Mutants of Arabidopsis deficient in the synthesis of α-linolenate. Biochemical and genetic characterization of the endoplasmic reticulum linoleoyl desaturase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 16345–16351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuley, J.; Lightner, J.; Feldmann, K.; Yadav, N.; Lark, E.; Browse, J. Arabidopsis FAD2 gene encodes the enzyme that is essential for polyunsaturated lipid synthesis. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speerling, P.; Heinz, E. Isomeric sn-1-octadecenyl and sn-2-octadecenyl analogues of lysophosphatidylcholine as substrates for acylation and desaturation by plant microsomal membranes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993, 213, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tan, R.K.; Guo, X.J.; Fu, Z.L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Tan, X.L. Transcriptome analysis comparison of lipid biosynthesis in the leaves and developing seeds of Brassica napus. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Kazachkov, M.; Shen, W.; Bai, M.; Wu, H.; Zou, J. Deciphering the roles of Arabidopsis LPCAT and PAH in phosphatidylcholine homeostasis and pathway coordination for chloroplast lipid synthesis. Plant J. 2014, 80, 965–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Pérez, A.J.; Santos-Pereira, J.M.; Martins-Noguerol, R.; DeAndrés-Gil, C.; Troncoso-Ponce, M.A.; Venegas-Calerón, M.; Sánchez, R.; Garcés, R.; Salas, J.J.; Tena, J.J.; et al. Genome-Wide Mapping of Histone H3 Lysine 4 Trimethylation (H3K4me3) and Its Involvement in Fatty Acid Biosynthesis in Sunflower Developing Seeds. Plants 2021, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Cheng, J.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.K.; Gong, Z. Peroxisomal β-oxidation regulates histone acetylation and DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10576–10585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Saito, K. Transformation of Perill frutescens var. crispa Using an Agrobacterium-Ri Binary Vector System. Plant Biotechnol. 1997, 14, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, K.-H.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, D.; Park, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Hwang, Y.-S.; Kim, Y.-H. Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of Perilla frutescens. Plant Cell Rep. 2004, 23, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgin, E. T-cell vaccines could top up immunity to COVID, as variants loom large. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, C.; Lenderts, B.; Feigenbutz, L.; Barone, P.; Llaca, V.; Fengler, K.; Svitashev, S. CRISPR–Cas9-mediated 75.5-Mb inversion in maize. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1427–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, T.; Starr, D.; Su, X.; Tang, G.; Chen, Z.; Carter, J.; Wittich, P.E.; Dong, S.; Green, J.; Burch, E.; et al. One-step genome editing of elite crop germplasm during haploid induction. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svitashev, S.; Schwartz, C.; Lenderts, B.; Young, J.K.; Mark Cigan, A. Genome editing in maize directed by CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).