Abstract

Unlike traditional small molecule drugs, fullerene is an all-carbon nanomolecule with a spherical cage structure. Fullerene exhibits high levels of antiviral activity, inhibiting virus replication in vitro and in vivo. In this review, we systematically summarize the latest research regarding the different types of fullerenes investigated in antiviral studies. We discuss the unique structural advantage of fullerenes, present diverse modification strategies based on the addition of various functional groups, assess the effect of structural differences on antiviral activity, and describe the possible antiviral mechanism. Finally, we discuss the prospective development of fullerenes as antiviral drugs.

1. Introduction

Fullerenes are all-carbon molecules discovered in 1985 [1]. They are spherical or ellipsoidal in shape, with a hollow cage structure. Three discoverers of fullerene C60 won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1996. Fullerene C60, the representative fullerene, is ~0.7 nm in diameter. In the past 30 years, with the continuous development of fullerene preparation technology [2,3,4,5], fullerenes have presented unprecedented opportunities in the fields of biomedicine, catalysis, superconduction, and photovoltaics. Nanomolecules have important applications in cancer treatment, diagnosis, imaging, drug delivery, catalysis, and biosensing [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Fullerene molecules not only have defined nanostructures, but also unique electronic characteristics, photophysical properties, and excellent biocompatibility. Fullerene molecules have properties that differ from those of traditional small molecule drugs, which make fullerenes nanodrug candidates [16], especially for diagnosis and treatment. For example, fullerenes and their derivatives can be used as antioxidants against inflammatory diseases, due to their rich conjugated double bonds, which scavenge free radicals [17,18]. Fullerene C60 activates tumor immunity by polarizing tumor-associated macrophages and combines with immune checkpoint inhibitors (PD-L1 monoclonal antibody) to achieve efficient tumor immunotherapy [19]. Fullerene C70 derivatives, as photosensitizers, produce singlet oxygen, which can effectively kill tumor cells [20]. Endohedral metal fullerenes serve as new nuclear magnetic resonance contrast agents [21,22] for treating liver steatosis [23] and tumors [24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Additionally, some fullerene derivatives stabilize immune effector cells and prevent/inhibit the release of proinflammatory mediators. Therefore, they are potential drugs for a variety of diseases, such as asthma [31], arthritis [32], and multiple sclerosis [33]. Moreover, carboxylic acid derivatives of fullerenes can cut DNA under visible light irradiation, with the potential for use as photosensitive biochemical probes [34]. Fullerene C60 carboxylic acid derivatives also exhibit neuroprotective activity [35] and strongly inhibit tumor growth in a zebrafish xenograft model [36]. Because nanoparticles have been approved as drugs and drug carriers, fullerenes have great potential as drugs or gene delivery carriers [37,38].

Currently, more than 90% of infectious diseases in humans are caused by viruses. The most well-known include the influenza virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and Ebola virus, which have caused serious damage [39,40,41,42,43]. Although several anti-HIV and anti-Ebola drugs, such as saquinavir, ritonavir, T20, lopinavir, ribavirin, tenofovir, and remdesivir, have been developed, their efficacy is not satisfactory. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which broke out in China in 2003, is a respiratory infection caused by a coronavirus. So far, there is no specific medicine for SARS. The novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, now circulating worldwide, is more infectious than SARS or HIV. For patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, there are no specific antiviral drugs.

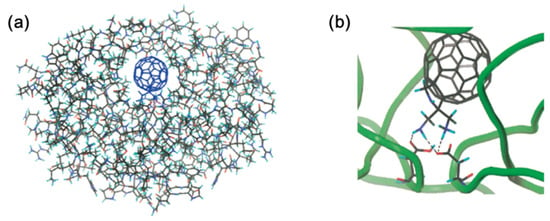

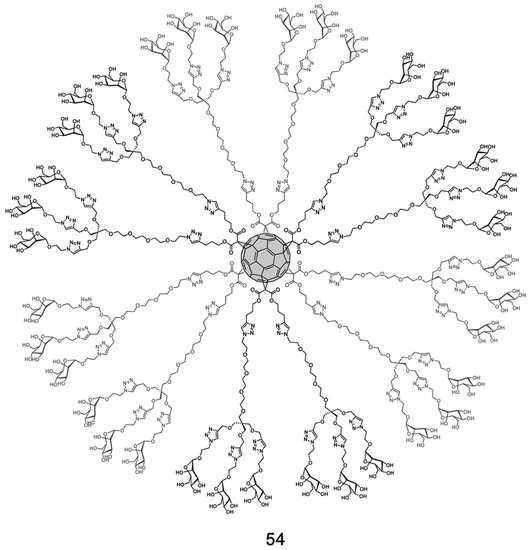

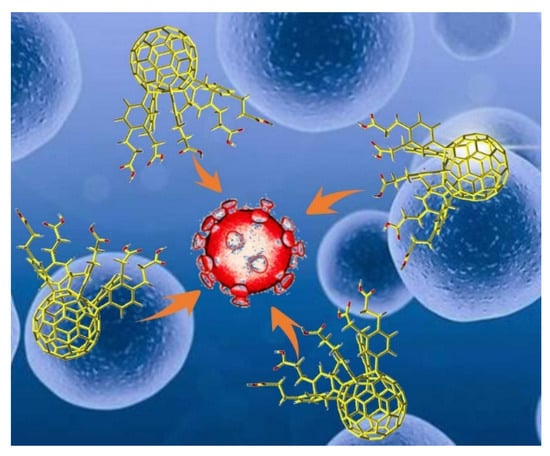

Fullerenes and their derivatives exert significant inhibitory effects against HIV [39], herpes simplex virus (HSV) [40], influenza virus [44], Ebola virus [45], cytomegalovirus (CMV) [46], and other viruses in vitro and in vivo (Figure 1). Fullerenes and their derivatives, as a class of new, broad-spectrum antiviral drugs, have attracted increasing attention as a potential treatment for SARS-CoV-2.

Figure 1.

Possible interaction between fullerene molecules and coronavirus, in which fullerene molecules inhibit virus replication.

Because fullerenes are insoluble in water and polar media, their use in biomedicine is extremely complicated [47]. To increase biocompatibility, the cage structure of fullerenes needs to be modified with appropriate hydrophilic functional groups. The modified structure and properties of the carbon cage may facilitate new applications in different biological systems. Because the fullerene carbon cage has multiple modifiable reaction sites, many fullerene derivatives with well-defined structures have been synthesized using regioselective functional group derivatization strategies. Therefore, fullerenes serve as ideal scaffolds for different bioactive drugs. Studies on the synthesis and antiviral activity of fullerenes and their derivatives have facilitated a deeper understanding of the relationship between fullerene structure and bioactivity.

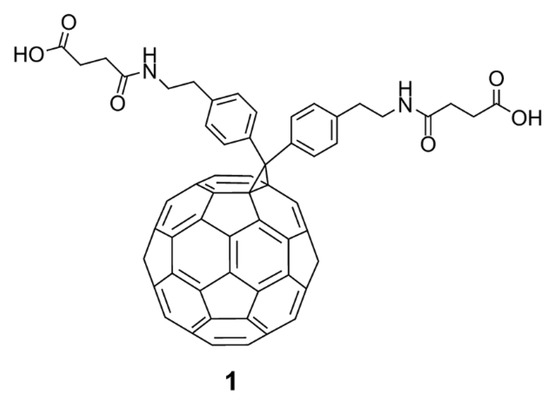

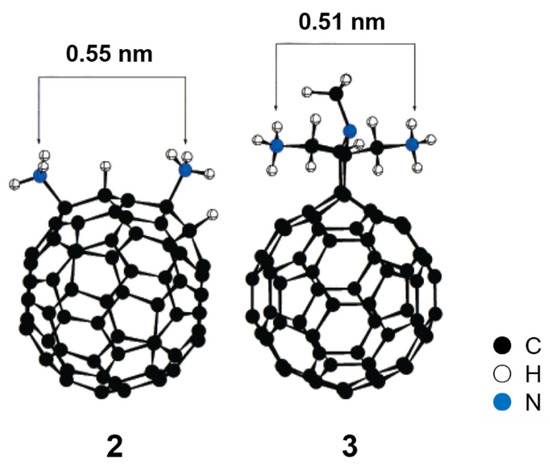

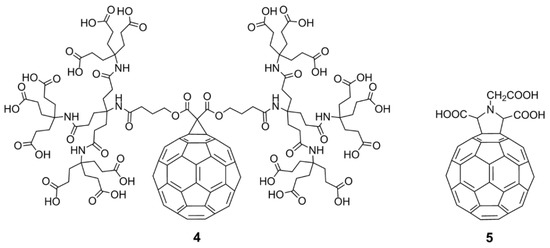

In the past, hundreds of fullerene derivatives have been synthesized and used to inhibit viruses in vitro. Most of these derivatives are water soluble. These fullerene derivatives can be classified as the following six types: (1) amino acid, peptide, and primary amine derivatives; (2) piperazine and pyrrolidine derivatives; (3) carboxyl derivatives; (4) hydroxyl derivatives; (5) glycofullerene derivatives; and (6) fullerene complexes. Numerous antiviral studies have been conducted to evaluate fullerene C60 and its derivatives; this review assesses the latest research on the ability of fullerene C60 and its derivatives to inhibit virus replication.

8. Conclusions

This review summarized the latest antiviral research conducted on fullerenes and their derivatives. Numerous water-soluble fullerene derivatives or fullerene complexes have shown great antiviral potential, mainly because fullerenes have three advantages. First, pristine fullerenes are hydrophobic, which is conducive to the formation of strong hydrophobic interactions with the active site surfaces of viruses. Second, hydrophilic groups with various functions (such as amino, carboxyl, amino acid, hydroxyl, pyrrolidine, and sugar groups) can be used to selectively modify the unique spherical skeleton of fullerenes via organic reactions. Third, fullerenes and their derivatives exhibit no or low cytotoxicity at relatively high concentrations. Although fullerenes are promising prospective antiviral drugs, antiviral research on fullerenes requires improvement. Most fullerene derivatives exhibit good antiviral effects in vitro, but the antiviral mechanism has not been thoroughly studied. Additionally, most of the studies on fullerenes have only focused on virus inhibition in vitro; there have been few antiviral studies in vivo, and relevant clinical studies involving fullerenes have not been conducted.

Viruses constantly threaten human health. Fullerenes have become an important molecular platform for the development of antiviral drugs. Research on fullerenes as antiviral drugs urgently needs the joint efforts of scientists working in synthesis, molecular design, biology, and medicine. Some fullerene derivatives display inhibitory activity against multiple types of viruses. Therefore, fullerene derivatives have the potential to become a class of broad-spectrum antiviral drugs effective against SARS-CoV-2, which remains a global threat. We believe that this review will encourage more researchers to synthesize fullerene derivatives and study their antiviral properties and applications.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (91961113, 21721001, 92061204, 21827801 and 92061000); Xiamen Youth Innovation Fund (3502Z20206054); the Funds of the Science and Technology Project of Yunnan Province-Major Project (202101AS070049).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kroto, H.W.; Heath, J.R.; O’Brien, S.C.; Curl, R.F.; Smalley, R.E. C60: Buckminsterfullerene. Nature 1985, 318, 162–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krätschmer, W.; Lamb, L.D.; Fostiropoulos, K.; Huffman, D.R. Solid C60: A new form of carbon. Nature 1990, 347, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.B.; McKinnon, J.T.; Makarovsky, Y.; Lafleur, A.L.; Johnson, M.E. Fullerenes C60 and C70 in flames. Nature 1991, 352, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.-R.; Chen, M.-M.; Wang, K.; Chen, Z.-C.; Fu, C.-Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.-H.; Deng, S.-L.; Yao, Y.-R.; Xie, S.-Y.; et al. An Unconventional Hydrofullerene C66H4 with Symmetric Heptagons Retrieved in Low-Pressure Combustion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6651–6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-G.; Zhuo, Y.-Q.; Zhang, X.-M.; Zhang, L.; Xu, P.-Y.; Tian, H.-R.; Lin, S.-C.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, S.-Y.; Zheng, L.-S. Synthesis of Fullerenes from a Nonaromatic Chloroform through a Newly Developed Ultrahigh-Temperature Flash Vacuum Pyrolysis Apparatus. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Chen, Y.; Shi, J. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)-Based Nanomedicine. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 4881–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, N.L.; Mirkin, C.A. Nanostructures in Biodiagnostics. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, K.; Luo, T.; Nash, G.T.; Lin, W. Nanoscale Metal–Organic Frameworks for Cancer Immunotherapy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtane, A.R.; Verma, M.; Karandikar, P.; Furin, J.; Langer, R.; Traverso, G. Nanotechnology approaches for global infectious diseases. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Song, C.; Wang, J.; Zou, Y.; Anderson, G.J.; Han, J.-Y.; et al. A DNA nanorobot functions as a cancer therapeutic in response to a molecular trigger in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, T.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, R.; Lang, J.; Qin, H.; Liu, X.; Shi, J.; Tao, N.; et al. Transformable Peptide Nanocarriers for Expeditious Drug Release and Effective Cancer Therapy via Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 1050–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Anderson, G.J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Reversal of pancreatic desmoplasia by re-educating stellate cells with a tumour microenvironment-activated nanosystem. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.; Gu, L.; Meziani, M.J.; Wang, X.; Luo, P.G.; Veca, L.M.; Cao, L.; Sun, Y.-P. Advances in Bioapplications of Carbon Nanotubes. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Z. Graphene based gene transfection. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 1252–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Nie, G.; Meng, H.; Xia, T.; Nel, A.; Zhao, Y. Physicochemical Properties Determine Nanomaterial Cellular Uptake, Transport, and Fate. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellinger, A.; Zhou, Z.; Connor, J.; Madhankumar, A.; Pamujula, S.; Sayes, C.M.; Kepley, C.L. Application of fullerenes in nanomedicine: An update. Nanomedicine 2013, 8, 1191–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, C.N.; McKay, R.G.; Larsen, B.S. C60 as a radical sponge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 4412–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, M. Carbon Nanomaterials as Antibacterial Colloids. Materials 2016, 9, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhen, M.; Wang, H.; Sun, Z.; Jia, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, C.; Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Bai, C. Functional Gadofullerene Nanoparticles Trigger Robust Cancer Immunotherapy Based on Rebuilding an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 4487–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Guan, M.; Xu, L.; Shu, C.; Jin, C.; Zheng, J.; Fang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C. Structural Effect and Mechanism of C70-Carboxyfullerenes as Efficient Sensitizers against Cancer Cells. Small 2012, 8, 2070–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarland, D.K.; Walker, K.L.; Lenk, R.P.; Wilson, S.R.; Kumar, K.; Kepley, C.L.; Garbow, J.R. Hydrochalarones: A Novel Endohedral Metallofullerene Platform for Enhancing Magnetic Resonance Imaging Contrast. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 3681–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-p.; Liu, Q.-l.; Zhen, M.-m.; Jiang, F.; Shu, C.-y.; Jin, C.; Yang, Y.; Alhadlaq, H.A.; Wang, C.-r. Multifunctional imaging probe based on gadofulleride nanoplatform. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 3669–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Zhen, M.; Yu, M.; Li, X.; Yu, T.; Liu, J.; Jia, W.; Liu, S.; Li, L.; Li, J.; et al. Gadofullerene inhibits the degradation of apolipoprotein B100 and boosts triglyceride transport for reversing hepatic steatosis. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Qian, P.; Zhu, T.; Zhao, Y. Gd-metallofullerenol nanomaterial as non-toxic breast cancer stem cell-specific inhibitor. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2016, 12, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-G.; Zhou, G.; Yang, P.; Liu, Y.; Sun, B.; Huynh, T.; Meng, H.; Zhao, L.; Xing, G.; Chen, C.; et al. Molecular mechanism of pancreatic tumor metastasis inhibition by Gd@C82(OH)22 and its implication for de novo design of nanomedicine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 15431–15436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhen, M.; Li, X.; Zou, T.; Li, J.; Yu, T.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, Z.; Xu, H.; et al. Real-time monitoring of tumor vascular disruption induced by radiofrequency assisted gadofullerene. Sci. China Mater. 2018, 8, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, M.; Shu, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, T.; Luo, Y.; Zou, T.; Deng, R.; Fang, F.; Lei, H.; et al. A highly efficient and tumor vascular-targeting therapeutic technique with size-expansible gadofullerene nanocrystals. Sci. China Mater. 2015, 58, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Deng, R.; Zhen, M.; Li, J.; Guan, M.; Jia, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, T.; Zou, T.; et al. Amino acid functionalized gadofullerene nanoparticles with superior antitumor activity via destruction of tumor vasculature in vivo. Biomaterials 2017, 133, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, H.; Zhen, M.; Guo, J.; Wang, L.; Jiang, L.; Shu, C.; Wang, C. Biocompatible [60]/[70] Fullerenols: Potent Defense against Oxidative Injury Induced by Reduplicative Chemotherapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 35539–35547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhen, M.; Ma, H.; Li, J.; Shu, C.; Wang, C. Inhalable gadofullerenol/[70] fullerenol as high-efficiency ROS scavengers for pulmonary fibrosis therapy. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2018, 14, 1361–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, S.K.; Wijesinghe, D.S.; Dellinger, A.; Sturgill, J.; Zhou, Z.; Barbour, S.; Chalfant, C.; Conrad, D.H.; Kepley, C.L. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids are involved in the C70 fullerene derivative–induced control of allergic asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, 761–769.e762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Lenk, R.P.; Dellinger, A.; Wilson, S.R.; Sadler, R.; Kepley, C.L. Liposomal Formulation of Amphiphilic Fullerene Antioxidants. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010, 21, 1656–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, A.S.; Frenkel, D.; Quintana, F.J.; Costa-Pinto, F.A.; Petrovic-Stojkovic, S.; Puckett, L.; Monsonego, A.; Bar-Shir, A.; Engel, Y.; Gozin, M.; et al. Reversal of axonal loss and disability in a mouse model of progressive multiple sclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 1532–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokuyama, H.; Yamago, S.; Nakamura, E.; Shiraki, T.; Sugiura, Y. Photoinduced biochemical activity of fullerene carboxylic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 7918–7919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, L.L.; Turetsky, D.M.; Du, C.; Lobner, D.; Wheeler, M.; Almli, C.R.; Shen, C.K.-F.; Luh, T.-Y.; Choi, D.W.; Lin, T.-S. Carboxyfullerenes as neuroprotective& agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 9434–9439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.-W.; Zhilenkov, A.V.; Kraevaya, O.A.; Mischenko, D.V.; Troshin, P.A.; Hsu, S.-h. Toward Understanding the Antitumor Effects of Water-Soluble Fullerene Derivatives on Lung Cancer Cells: Apoptosis or Autophagy Pathways? J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 7111–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigwalt, D.; Holler, M.; Iehl, J.; Nierengarten, J.-F.; Nothisen, M.; Morin, E.; Remy, J.-S. Gene delivery with polycationic fullerene hexakis-adducts. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 4640–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fan, J.; Fang, G.; Zeng, F.; Wang, X.; Wu, S. Water-Dispersible Fullerene Aggregates as a Targeted Anticancer Prodrug with both Chemo- and Photodynamic Therapeutic Actions. Small 2013, 9, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.H.; DeCamp, D.L.; Sijbesma, R.P.; Srdanov, G.; Wudl, F.; Kenyon, G.L. Inhibition of the HIV-1 protease by fullerene derivatives: Model building studies and experimental verification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 6506–6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashino, T.; Shimotohno, K.; Ikegami, N.; Nishikawa, D.; Okuda, K.; Takahashi, K.; Nakamura, S.; Mochizuki, M. Human immunodeficiency virus-reverse transcriptase inhibition and hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibition activities of fullerene derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 1107–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

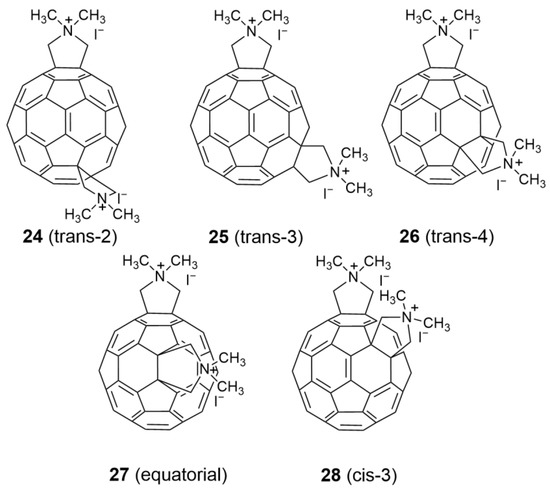

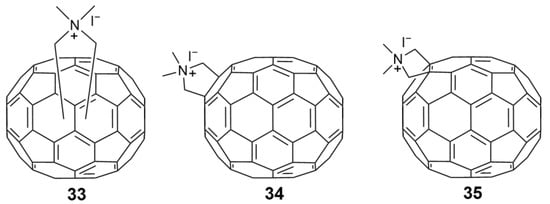

- Castro, E.; Martinez, Z.S.; Seong, C.-S.; Cabrera-Espinoza, A.; Ruiz, M.; Hernandez Garcia, A.; Valdez, F.; Llano, M.; Echegoyen, L. Characterization of New Cationic N,N-Dimethyl [70]fulleropyrrolidinium Iodide Derivatives as Potent HIV-1 Maturation Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 10963–10973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

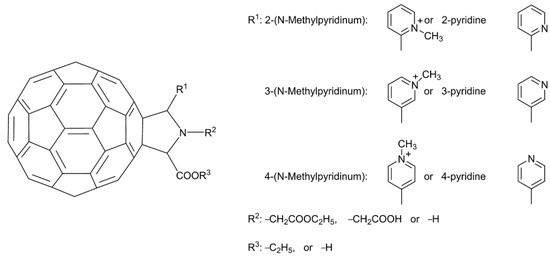

- Yasuno, T.; Ohe, T.; Takahashi, K.; Nakamura, S.; Mashino, T. The human immunodeficiency virus-reverse transcriptase inhibition activity of novel pyridine/pyridinium-type fullerene derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 3226–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

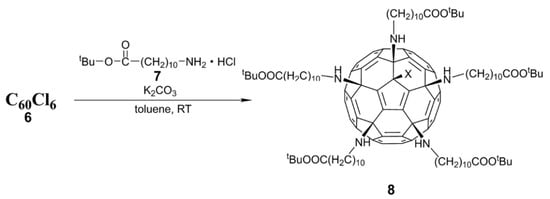

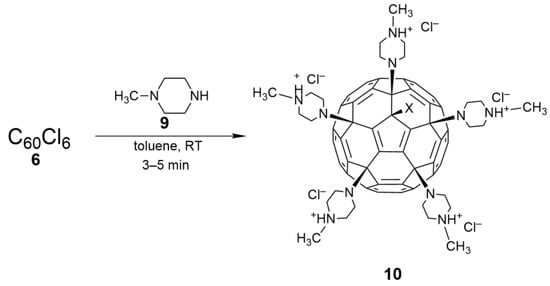

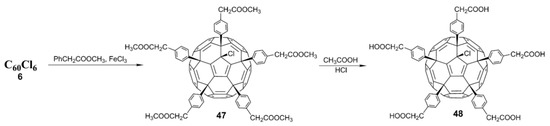

- Kornev, A.B.; Khakina, E.A.; Troyanov, S.I.; Kushch, A.A.; Peregudov, A.; Vasilchenko, A.; Deryabin, D.G.; Martynenko, V.M.; Troshin, P.A. Facile preparation of amine and amino acid adducts of [60]fullerene using chlorofullerene C60Cl6 as a precursor. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 5461–5463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollas, S.; Bereczki, I.; Borbás, A.; Batta, G.; Vanderlinden, E.; Naesens, L.; Herczegh, P. Synthesis of a cluster-forming sialylthio-d-galactose fullerene conjugate and evaluation of its interaction with influenza virus hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 2420–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

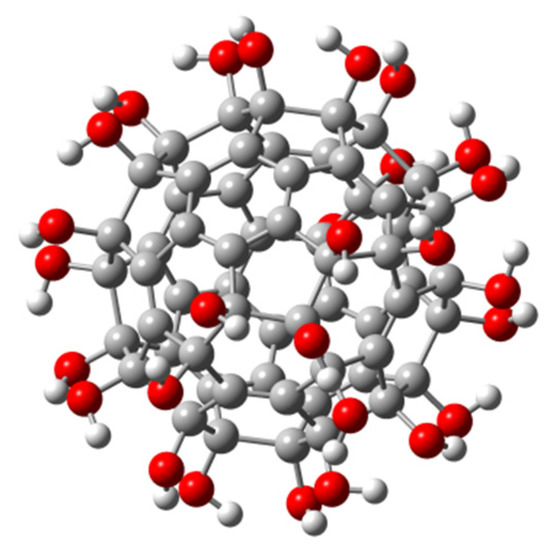

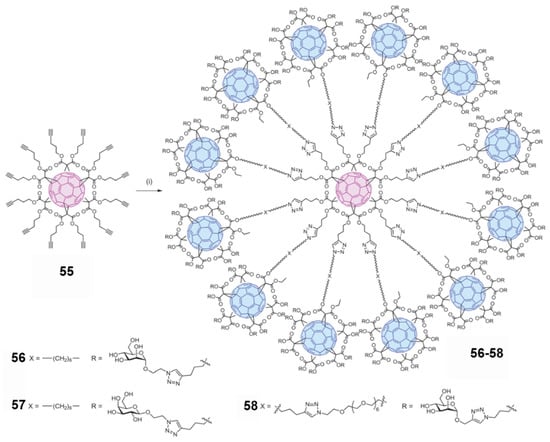

- Muñoz, A.; Sigwalt, D.; Illescas, B.M.; Luczkowiak, J.; Rodríguez-Pérez, L.; Nierengarten, I.; Holler, M.; Remy, J.-S.; Buffet, K.; Vincent, S.P.; et al. Synthesis of giant globular multivalent glycofullerenes as potent inhibitors in a model of Ebola virus infection. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, N.E.; Klimova, R.R.; Tulenev, Y.A.; Chichev, E.V.; Kornev, A.B.; Troshin, P.A.; Kushch, A.A. Carboxylic Fullerene C60 Derivatives: Efficient Microbicides Against Herpes Simplex Virus and Cytomegalovirus Infections In Vitro. Mendeleev Commun. 2012, 22, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, E.; Isobe, H. Functionalized Fullerenes in Water. The First 10 Years of Their Chemistry, Biology, and Nanoscience. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debouck, C. The HIV-1 Protease as a Therapeutic Target for AIDS. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 1992, 8, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijbesma, R.; Srdanov, G.; Wudl, F.; Castoro, J.A.; Wilkins, C.; Friedman, S.H.; DeCamp, D.L.; Kenyon, G.L. Synthesis of a fullerene derivative for the inhibition of HIV enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 6510–6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Ros, T.; Prato, M. Medicinal chemistry with fullerenes and fullerene derivatives. Chem. Commun. 1999, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, D.I.; Wilson, S.R.; Schinazi, R.F. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity and cytotoxicity of derivatized buckminsterfullerenes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1996, 6, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

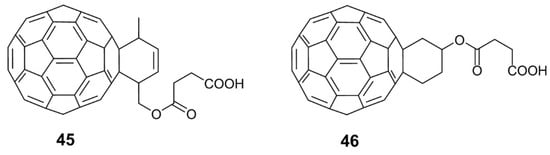

- Marcorin, G.L.; Da Ros, T.; Castellano, S.; Stefancich, G.; Bonin, I.; Miertus, S.; Prato, M. Design and Synthesis of Novel [60]Fullerene Derivatives as Potential HIV Aspartic Protease Inhibitors. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 3955–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettreich, M.; Hirsch, A. A highly water-soluble dendro [60]fullerene. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 2731–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, D.; Wilson, S.; Kirschner, A.; Schinazi, R.; Schlueter-Wirtz, S.; Barnett, T.; Martin, S.; Brettreich, M.; Hirsch, A. Evaluation of the anti-HIV Potency of a Water- Soluble Dendrimeric Fullerene Derivative. Proc. Electrochem. Soc. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Toniolo, C.; Bianco, A.; Maggini, M.; Scorrano, G.; Prato, M.; Marastoni, M.; Tomatis, R.; Spisani, S.; Palu, G.; Blair, E.D. A Bioactive Fullerene Peptide. J. Med. Chem. 1994, 37, 4558–4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

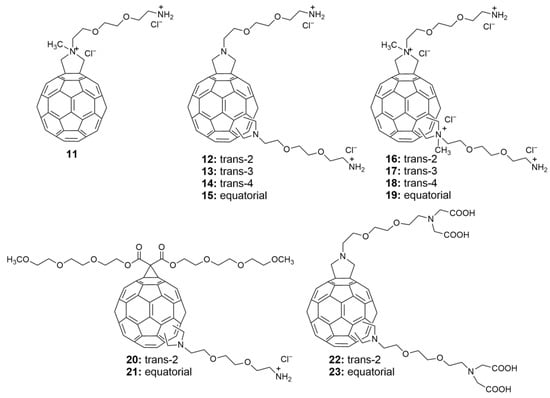

- Bosi, S.; Da Ros, T.; Spalluto, G.; Balzarini, J.; Prato, M. Synthesis and Anti-HIV properties of new water-soluble bis-functionalized [60]fullerene derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 4437–4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesan, S.; Da Ros, T.; Spalluto, G.; Balzarini, J.; Prato, M. Anti-HIV properties of cationic fullerene derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 3615–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Mashino, T. Water-soluble Fullerene Derivatives for Drug Discovery. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 2012, 79, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Yasuno, T.; Takahashi, K.; Nakamura, S.; Mashino, T.; Ohe, T. Novel pyridinium-type fullerene derivatives as multitargeting inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase, HIV-1 protease, and HCV NS5B polymerase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 49, 128267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, Z.S.; Castro, E.; Seong, C.-S.; Cerón, M.R.; Echegoyen, L.; Llano, M. Fullerene Derivatives Strongly Inhibit HIV-1 Replication by Affecting Virus Maturation without Impairing Protease Activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5731–5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

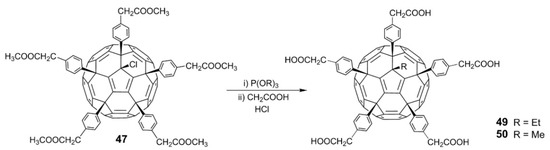

- Troshina, O.A.; Troshin, P.A.; Peregudov, A.S.; Kozlovskiy, V.I.; Balzarini, J.; Lyubovskaya, R.N. Chlorofullerene C60Cl6: A precursor for straightforward preparation of highly water-soluble polycarboxylic fullerene derivatives active against HIV. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 2783–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraevaya, O.g.A.; Peregudov, A.S.; Troyanov, S.I.; Godovikov, I.; Fedorova, N.E.; Klimova, R.R.; Sergeeva, V.A.; Kameneva, L.V.; Ershova, E.S.; Martynenko, V.M.; et al. Diversion of the Arbuzov reaction: Alkylation of C–Cl instead of phosphonic ester formation on the fullerene cage. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2019, 17, 7155–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraevaya, O.A.; Peregudov, A.S.; Godovikov, I.A.; Shchurik, E.V.; Martynenko, V.M.; Shestakov, A.F.; Balzarini, J.; Schols, D.; Troshin, P.A. Direct arylation of C60Cl6 and C70Cl8 with carboxylic acids: A synthetic avenue to water-soluble fullerene derivatives with promising antiviral activity. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 1179–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khakina, E.A.; Yurkova, A.A.; Peregudov, A.S.; Troyanov, S.I.; Trush, V.V.; Vovk, A.I.; Mumyatov, A.V.; Martynenko, V.M.; Balzarini, J.; Troshin, P.A. Highly selective reactions of C60Cl6 with thiols for the synthesis of functionalized [60]fullerene derivatives. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 7158–7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronov, I.I.; Martynenko, V.M.; Chernyak, A.V.; Balzarini, J.; Schols, D.; Troshin, P.A. Synthesis and Antiviral Activity of Water-Soluble Polycarboxylic Derivatives of [60]Fullerene Loaded with 3,4-Dichlorophenyl Units. Chem. Biodivers. 2018, 15, e1800293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornev, A.B.; Peregudov, A.S.; Martynenko, V.M.; Balzarini, J.; Hoorelbeke, B.; Troshin, P.A. Synthesis and antiviral activity of highly water-soluble polycarboxylic derivatives of [70]fullerene. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 8298–8300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

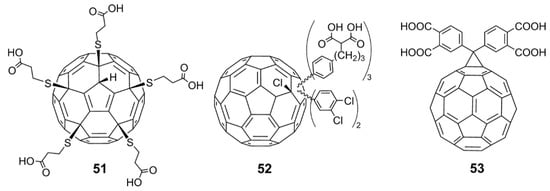

- Eropkin, M.Y.; Melenevskaya, E.Y.; Nasonova, K.V.; Bryazzhikova, T.S.; Eropkina, E.M.; Danilenko, D.M.; Kiselev, O.I. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Fullerenols with Various Contents of Hydroxyl Groups. Pharm. Chem. J. 2013, 47, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Liang, D.; Gan, L.; Li, Y. Facile Synthesis of Isomerically Pure Fullerenols and Formation of Spherical Aggregates from C60(OH)8. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5293–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozzi, C.R.; Kiessling, A.L.L. Chemical Glycobiology. Science 2001, 291, 2357–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundquist, J.J.; Toone, E.J. The Cluster Glycoside Effect. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 555–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houseman, B.T.; Mrksich, M. Model Systems for Studying Polyvalent Carbohydrate Binding Interactions. In Host-Guest Chemistry: Mimetic Approaches to Study Carbohydrate Recognition; Penadés, S., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabre, Y.M.; Roy, R. Chapter 6—Design and Creativity in Synthesis of Multivalent Neoglycoconjugates. In Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry; Horton, D., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; Volume 63, pp. 165–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondoni, A.; Marra, A.; Scherrmann, M.-C.; Casnati, A.; Sansone, F.; Ungaro, R. Synthesis and Properties of O-Glycosyl Calix [4]Arenes (Calixsugars). Chemistry—A Eur. J. 1997, 3, 1774–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, J.M.; Barrientos, A.G.; Rojas, T.C.; Rojo, J.; Cañada, J.; Fernández, A.; Penadés, S. Gold Glyconanoparticles as Water-Soluble Polyvalent Models to Study Carbohydrate Interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R. Syntheses and some applications of chemically defined multivalent glycoconjugates. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1996, 6, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewart, R.J.; Boggs, J.M. A carbohydrate-carbohydrate interaction between galactosylceramide-containing liposomes and cerebroside sulfate-containing liposomes: Dependence on the glycolipid ceramide composition. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 10666–10674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imberty, A.; Chabre, Y.M.; Roy, R. Glycomimetics and Glycodendrimers as High Affinity Microbial Anti-adhesins. Chemistry—A Eur. J. 2008, 14, 7490–7499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczkowiak, J.; Muñoz, A.; Sánchez-Navarro, M.; Ribeiro-Viana, R.; Ginieis, A.; Illescas, B.M.; Martín, N.; Delgado, R.; Rojo, J. Glycofullerenes Inhibit Viral Infection. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, A.; Vostrowsky, O. C60 Hexakisadducts with an Octahedral Addition Pattern—A New Structure Motif in Organic Chemistry. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 2001, 829–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Soriano, J.; Reina, J.J.; Illescas, B.M.; de la Cruz, N.; Rodríguez-Pérez, L.; Lasala, F.; Rojo, J.; Delgado, R.; Martín, N. Synthesis of Highly Efficient Multivalent Disaccharide/[60]Fullerene Nanoballs for Emergent Viruses. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 15403–15412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, A.; Illescas, B.M.; Luczkowiak, J.; Lasala, F.; Ribeiro-Viana, R.; Rojo, J.; Delgado, R.; Martín, N. Antiviral activity of self-assembled glycodendro [60]fullerene monoadducts. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 6566–6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattei, S.; Glass, B.; Hagen, W.J.H.; Kräusslich, H.-G.; Briggs, J.A.G. The structure and flexibility of conical HIV-1 capsids determined within intact virions. Science 2016, 354, 1434–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

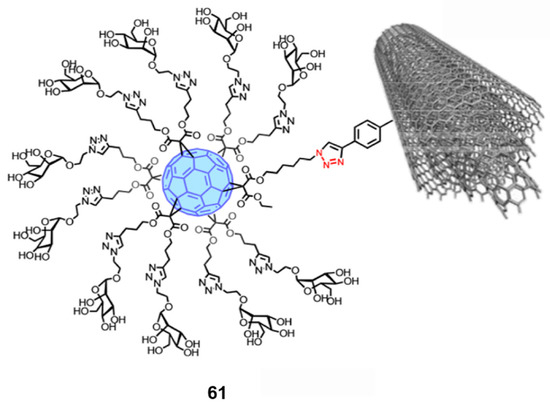

- Rodríguez-Pérez, L.; Ramos-Soriano, J.; Pérez-Sánchez, A.; Illescas, B.M.; Muñoz, A.; Luczkowiak, J.; Lasala, F.; Rojo, J.; Delgado, R.; Martín, N. Nanocarbon-Based Glycoconjugates as Multivalent Inhibitors of Ebola Virus Infection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9891–9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

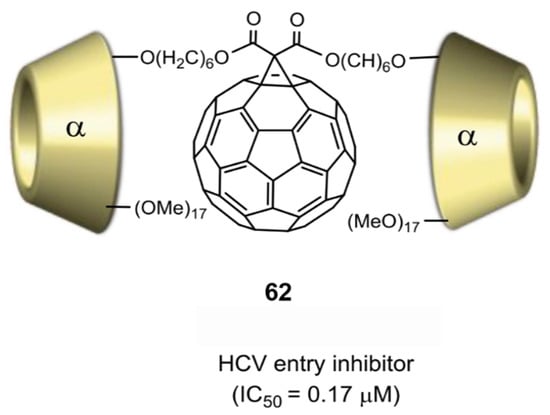

- Zhu, X.; Xiao, S.; Zhou, D.; Sollogoub, M.; Zhang, Y. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of water-soluble per-O-methylated cyclodextrin-C60 conjugates as anti-influenza virus agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 146, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.-L.; Wang, Q.; Yu, F.; Peng, Y.-Y.; Yang, M.; Sollogoub, M.; Sinaÿ, P.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Zhang, L.-H.; Zhou, D.-M. Conjugation of cyclodextrin with fullerene as a new class of HCV entry inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 5616–5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

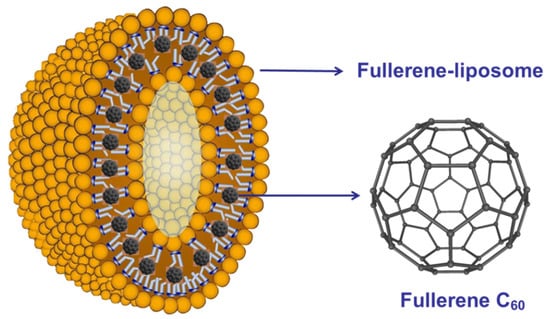

- Sirotkin, A.K.; Zarubaev, V.V.; Poznyiakova, L.N.; Dumpis, M.A.; Muravieva, T.D.; Krisko, T.K.; Belousova, I.M.; Kiselev, O.I.; Piotrovsky, L.B. Pristine Fullerene C60: Different Water Soluble Forms—Different Mechanisms of Biological Action. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostructures 2006, 14, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.X. The antiviral effect of fullerene-liposome complex against influenza virus (H1N1) in vivo. Sci. Res. Essays 2012, 7, 705–711. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).