Abstract

Exosomes have been proven to play a positive role in tendon and tendon–bone healing. Here, we systematically review the literature to evaluate the efficacy of exosomes in tendon and tendon–bone healing. Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, a systematic and comprehensive review of the literature was performed on 21 January 2023. The electronic databases searched included Medline (through PubMed), Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library and Ovid. In the end, a total of 1794 articles were systematically reviewed. Furthermore, a “snowball” search was also carried out. Finally, forty-six studies were included for analysis, with the total sample size being 1481 rats, 416 mice, 330 rabbits, 48 dogs, and 12 sheep. In these studies, exosomes promoted tendon and tendon–bone healing and displayed improved histological, biomechanical and morphological outcomes. Some studies also suggested the mechanism of exosomes in promoting tendon and tendon–bone healing, mainly through the following aspects: (1) suppressing inflammatory response and regulating macrophage polarization; (2) regulating gene expression, reshaping cell microenvironment and reconstructing extracellular matrix; (3) promoting angiogenesis. The risk of bias in the included studies was low on the whole. This systematic review provides evidence of the positive effect of exosomes on tendon and tendon–bone healing in preclinical studies. The unclear-to-low risk of bias highlights the significance of standardization of outcome reporting. It should be noted that the most suitable source, isolation methods, concentration and administration frequency of exosomes are still unknown. Additionally, few studies have used large animals as subjects. Further studies may be required on comparing the safety and efficacy of different treatment parameters in large animal models, which would be conducive to the design of clinical trials.

1. Introduction

Tendons are structures composed of fibrous connective tissue that transmit power from muscles to bones. Although tendons can withstand different loadings, their damage is extremely severe. Due to the lack of blood vessels, the regeneration ability of tendons is poor. Therefore, tendon repair is a huge challenge in medicine. Tendon or ligament injuries are common. In the United States, every year there are more than 300,000 patients who require surgery to repair tendons or ligaments, and the number is growing as the population grows and sports are becoming more popular [1,2].

Common tendon injury can be divided into chronic injury caused by degeneration and acute injury caused by direct rupture, both of which significantly change the structure and function of the tendon. In severe cases, the tendon–bone interface is also damaged [3]. Generally, four stages take place in tendon or tendon–bone healing. The first stage is the inflammation stage, when macrophages are recruited to the injured site and vascular permeability increases. The second stage is the proliferation stage, which takes a long time. In this stage, cells proliferate and produce some growth factors. The next stage is the remodeling stage, when fibrocartilage and fibers form. In the last stage, the maturation stage, the biomechanical strength of the tendon gradually recovers [4,5,6].

For acute and chronic tendon injuries, different treatment methods are usually adopted in clinical practice (Table 1). However, as there are few blood vessels in the tendon and the metabolism is low, traditional treatment methods can not completely restore the structure and function of the tendon, and may even cause complications such as tendon adhesion and osteolysis [7,8,9]. The rotator cuff is a typical tendon structure composed of tendons from the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis muscle, which is prone to injury. It is known that rotator cuff tear (RCT) and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury are the two most common diseases that require tendon graft, which may cause severe pain, dysfunction and even disability [10,11]. After the reconstruction of the rotator cuff and ACL, the rates of re-tear and failure are still high [11,12]. The most important reason may be that the tendon–bone healing process is not ideal [1,13].

Table 1.

Summary of existing treatment options for acute tendon injury and chronic tendon injury.

The tendon–bone interface, where the tendon or ligament insert into bone, is also called “enthesis” [20]. It includes both soft and hard tissues, which are divided into four gradual and continuous histological zones. The first zone is the tendon, consisting of well-aligned type I collagen fibers, type II collagen, elastin, and small leucine-rich proteoglycan; the second zone is unmineralized fibrocartilage, predominantly consisting of type II and III collagen; the third zone, mineralized fibrocartilage, contains type II and III collagen, as well as aggrecan and type X collagen; the last zone is bone [21,22,23]. Compared with other tissues, there are very limited blood vessels at the tendon–bone interface. As a result, oxygen, growth factors, and nutrients delivered here are insufficient, which may exacerbate the inflammatory reaction and affect cell proliferation and tissue reconstruction [24,25]. It was reported that the key biological process of tendon–bone healing after ACL reconstruction may last for more than 1 year [26]. Therefore, there is no denying that tendon–bone healing is one of the most significant but challenging processes in tendon healing.

In recent years, the application of biomaterials in medicine has become increasingly widespread and it is important to select appropriate biomaterials for the treatment of specific diseases [27,28,29]. In order to promote tendon and tendon–bone healing, many biological methods based on platelet plasma [30], growth and differentiation factors [31], cell therapy [32] and tissue engineering [33] have been used (Table 2). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can be easily isolated from tissues and have the potential to differentiate into multiple cells. Multiple studies have demonstrated their effectiveness in tendon and tendon–bone healing [32,34,35]. However, stem cell therapy may pose clinical risks such as immune rejection, thrombosis and some ethical problems [36,37,38]. It was also reported that bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells cultured in vitro are prone to malignant transformation spontaneously, which is a serious threat to the safety of cell-based therapies and regenerative medicine [38]. Therefore, cell-free therapies based on stem cell secretions have become the focus of attention. Exosomes, a kind of extracellular vesicle with a diameter of 30~150 nm secreted by cells, which contain a variety of proteins, lipids and nucleic acids such as microRNA (miRNA), mRNA and DNA, play an important role in cell-to-cell communication [39,40,41]. Exosomes have been reported to play an effective therapeutic role in a variety of cancers [42,43,44], neurological diseases [45] and acute organ injuries [46]. In recent years, exosomes have also been proven to promote tendon and tendon–bone healing [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90].

Table 2.

Summary of existing cellular therapy options for tendon injury.

The purpose of this systematic review is to summarize and scrutinize existing preclinical studies to illustrate the following aspects: 1. The efficacy of exosomes in tendon healing and tendon–bone healing, and how to improve the therapeutic effect of exosomes. 2. Separation and administration methods of exosomes. 3. The mechanisms of exosomes promoting tendon healing and tendon–bone healing. 4. Inconsistency in existing studies and possible explanations. This is the most up-to-date synthesis of evidence on this topic, and we first systematically reviewed the signaling pathways and gene expression changes of exosomes in promoting tendon healing and tendon–bone healing to elucidate their mechanisms. For different animal models, treatment parameters and some key therapeutic outcomes, we present and discuss the results of tendon healing studies and tendon–bone healing studies separately.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods Literature Retrieval

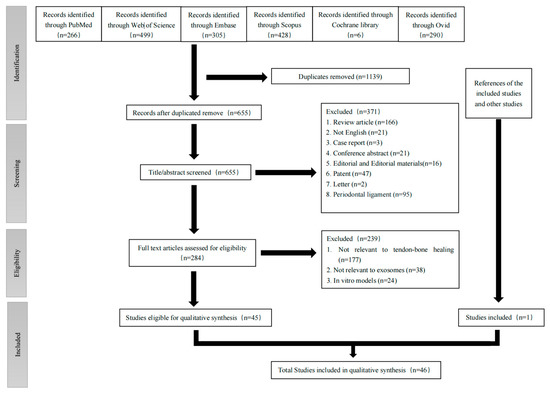

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement protocol published in 2020 [97] (the checklist is shown in Supplementary Table S1). A flowchart of the literature screening is provided in Figure 1. On 21 January 2023, a systematic and comprehensive search for this review was performed. We used the following key words: “exosome*”, “extracellular vesicle*”, “exosomal”, “Cell-Derived Microparticle*”, “secretome*”, “tendon*”, “ligament*”, “rotator cuff”, “Achilles”, “enthesis”, “footprint”, “tendinous*” “tendinopathy”, “Tendinopathies”, “Tendinosis” and “Tendinitis”. The electronic databases searched included Medline (through PubMed), Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library and Ovid. The specific search strategy is shown in Supplementary Table S2. The methods of analysis, inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Supplementary Table S3. A “snowball” search was also carried out to identify additional eligible studies by searching the reference lists of articles eligible for a full-text review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow chart.

All studies found by our search were imported into Endnote 20, which helped remove the duplicates. The eligibility assessment was conducted independently by MRZ and JZW. Two reviewers completed the title, abstract and conclusion of each article, and excluded the articles whose study types were Patent, Conference Abstract, Letter, Case report, Editorial, or Review and articles focusing on periodontal ligament or dental-related diseases. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer (ZXS) was contacted to discuss whether to include the article. Next, full-text screening of the rest of the articles was conducted independently by the two reviewers based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria shown in Supplementary Table S3. Additionally, a third reviewer (ZXS) was contacted to solve any disagreement.

It is significant to point out that current methods for exosome purification are immature and imperfect. Sometimes, other types of extracellular vesicles are present in purified exosomes, resulting in a diameter distribution that is not completely contained within the range of 30~150 nm [47,48,51,61,62,71,74,78,98,99,100]. So, for articles that focus on the effect of extracellular vesicles promoting tendon or tendon–bone healing, we examined the distribution of extracellular vesicle diameters. Articles in which the distribution of diameters was significantly outside the distribution of exosomes (30~150 nm) were excluded [98,99,100]. In this review, “EV”, “exosome” and “extracellular vesicle (EV)” all indicate “exosome”.

2.2. Data Extraction

Data extraction was individually conducted by two reviewers. In case of disagreement, the reviewers discussed until an agreement was reached. Apart from the descriptives of individual included studies, other data were collected, such as: 1. Characteristics and isolation of exosomes, which include the origin, source, isolation methods, storage condition, verification methods, size distribution and biomarkers of exosomes. 2. Information of in vivo experimental animal models, which include how the model was established, gender, euthanasia time and number of animals used in each group; the concentration, volume, and delivery route and frequency of the reagent. 3. In vivo therapeutic outcomes, including morphological outcomes, histology outcomes, biomechanical outcomes, and biochemical outcomes. 4. In vitro experimental outcomes, which include cell survival, proliferation, differentiation and migration.

2.3. Assessment of Quality of Studies

Assessment of the quality of studies was also conducted by the two reviewers. The Systematic Review Centre for Laboratory Animal Experimentation (SYRCLE) risk of bias assessment tool was used to evaluate the selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attribution bias, reporting bias and other biases of the studies [101].

2.4. Data Analysis

The results of the studies were largely evaluated qualitatively as there were insufficient quantitative data in the studies.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

Details about the selection process are shown in a PRISMA flow chart in Figure 1. After searching the six databases, a total of 1794 studies were found. Forty-five articles were included after screening and all of them were case–control studies [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,86,87,88,89,90]. Another article was included by searching the references of the included articles and review articles related to the topic [85]. Finally, 46 studies were included for synthesis.

3.2. Assessment of Quality of Studies

The detailed assessment of the quality of each study is demonstrated in Supplementary Table S4. All studies had a low risk of baseline characteristics under selection bias, random outcome assessment under detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other biases [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. All studies reported baseline characteristics of the animals used which included the species, age and gender of the animals, and the outcomes were randomly assessed [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. Therefore, all studies were assigned low risk for baseline characteristics and random outcome assessment [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. All studies reported average results of all animal experiments; therefore, they were assigned low risk for random outcome assessment [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. No studies reported the death of animals before the end of experiments, which ensured the low risk of attrition bias. No studies reported relevant information on sequence generation and allocation concealment. So, for these two categories, all studies were assigned unclear risks. Ten studies reported that animals were housed in the same and specific living environment, so they had a low risk of random housing [8,9,47,48,50,58,62,66,80,89]. However, one study pointed out that animals were not assigned randomly, and the order of surgical treatments was not randomized either, which would be more economical [59]. So, this study was assigned a high risk of performance bias which included random housing and blinding [59]. Other studies did not report the use of blinding methods during the process of animal housing; therefore, they were assigned unclear risks for blinding under performance bias [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. Sixteen studies reported blinding of the assessors when assessing for the outcomes and were therefore classified as low risk for blinding under detection bias [8,47,48,56,57,60,62,69,70,72,73,74,79,81,82,90]. On the whole, the risk of biases in the included studies was low [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90].

3.3. Source of Exosomes

The detailed results of sources of exosomes were shown in Supplementary Table S5. Human MSC exosomes [8,9,47,48,51,55,58,60,63,64,65,69,70,74,76,79,83,90] and rat MSC exosomes [49,53,62,66,67,71,72,73,75,77,78,81,82,85,88,89] were the two most common sources, and about one-third of studies used them, respectively. Mouse MSC exosomes [50,54,56,68,80,84] and rabbit MSC exosomes [57,61,86] were also used in a few studies. Three studies used purified exosome products [52,59,87]. Sources of human MSC exosomes included adipose MSCs [60,65,74,76,79,90], umbilical cord MSCs [9,55,63,69,70], induced pluripotent MSCs [47,51,58], bone marrow MSCs [48,64,83] and tendon stem/progenitor cell (TSPCs) [8]. Sources of rat MSC exosomes included bone marrow MSCs [62,71,73,82,85,88,89], adipose MSCs [72,75,77,78], tendon stem cells (TSCs) [49,53,66,67] and infrapatellar fat pad MSCs [81]. Sources of mouse MSC exosomes included bone marrow MSCs [80,84], bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) [56,68], fibroadipogenic progenitor (FAPs) [54], and adipose MSCs [50]. Sources of rabbit MSC exosomes included bone marrow MSCs [57,86] and adipose MSCs [61].

In most studies, the origin and source of exosomes across experimental groups were generally the same. However, in one study, Hayashi et al. compared the therapeutic effect of EVs derived from bone marrow MSCs at passage 5 and passage 12. The results showed that mice treated with P5 EVs demonstrated a better therapeutic effect. There were no significant adhesions between the tendon and surrounding tissue, the histological score was better, and the newly formed collagen fibers and tendon were similar to normal tendon tissue. However, different from P12 EVs, the particle size diameter range of P5 EVs was contained within the range of exosome (30~150 nm) [48].

3.4. Isolation and Characterization of Exosomes

The detailed results of the isolation and characterization of exosomes were shown in Supplementary Table S5. Ninety-one percent of studies isolated exosomes based on centrifugation [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,53,54,55,56,57,58,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,88,89,90], among which thirty-eight studies performed differential centrifugation followed by ultracentrifugation [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,53,54,55,57,58,60,62,63,64,65,66,67,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,88,89,90]. Three studies used purified exosome products. [52,59,87] One study used a total exosome isolation reagent to obtain exosomes [86]. As for characterization, nanoparticle tracking analysis, transmission electron microscope and Western blot were the three most common methods to visualize exosomes and analyze their size distribution. Other methods such as nano-flow analysis (NFA), dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), flow cytometry (FCM), atomic force microscopy (AFM) and colloidal nano plasmonic assay (CONAN) were also used by a few studies [8,47,62,64,70,78,86]. The size distribution of exosomes mainly ranged from approximately 30 to 150 nm. However, as we mentioned before, as current methods for exosomes purification are immature and imperfect, the exosomes isolated were sometimes not completely pure [9,47,48,51,53,61,62,66,69,71,73,74,78,83,85,86,87]. Interestingly, two studies compared the therapeutic effect of exosomes with extracellular vesicles with larger diameters and they reported different results [58,72]. Ye et al. reported that the therapeutic effects of exosomes and EVs were similar while Xu et al. pointed out that exosomes demonstrated better therapeutic effects [58,72]. CD9, CD63, CD80, TSG101 and HSP70 were the most common positive makers of exosomes. Some studies also reported the absence of negative makers of exosomes including GM130 and Calnexin [47,51,58,63,65,69,72,74,83,85,86,89,90]. Fifteen studies reported that the exosomes were stored at −80 °C before being used [9,47,55,58,61,62,70,72,73,74,83,84,85,87,88], while one study stored exosomes at 4 °C [54].

3.5. Animal Models

The detailed results of animal models were shown in Table 3 and Table 4. Among the thirty-five studies on tendon healing [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79], five animal species were used to construct animal models, which included rats, mice, rabbits, dogs and sheep. Most studies chose male animals. Rats were the most common animal used for animal models, and were used in twenty-two studies [8,9,47,49,51,53,55,58,62,63,65,66,67,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78], and Sprague Dawley rats were used in twenty studies, which were the most frequent [8,9,47,49,51,55,58,63,65,66,67,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78]. One-fifth of the studies used mice [48,50,54,56,64,68,79], and New Zealand rabbits [57,59,60,61], dogs [52], sheep [70] were also used by a few studies. Methods for constructing tendon injury models can be divided into three main categories: performing surgeries; injection of solution; training animals with a treadmill. Eighty percent of studies performed surgeries on animals [8,9,48,49,50,52,54,55,56,57,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,67,68,69,70,71,73,74,75,76,77,78]. As the Achilles tendon and rotator cuff were the most common sites of tendon injury, they were damaged for animal models in twelve [9,48,49,50,55,59,61,62,63,64,69,74] and seven [54,57,60,65,70,75,76] studies, respectively. The central part of the patellar tendon [8,67,71,73,77], the flexor digitorum longus [56,68], and the tendon of the interphalangeal joint [52] were resected or removed to establish animal models in a few studies. Six studies injected solutions to create models [47,51,53,58,66,72]. Three injected a carrageenan solution [47,51,58], and three injected a type I collagenase solution [53,66,72]. One study used a treadmill to train the mice, which is a novel method and may simulate the natural degeneration process of the tendon [79].

Table 3.

Summary of characteristics of animal models used (tendon healing).

Table 4.

Summary of characteristics of animal models used (tendon–bone healing).

Across the 11 studies on tendon–bone healing [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90], Sprague Dawley rats were used to construct animal models in nearly half of the studies [81,82,83,87,88]. Three studies used C57BL/6J mice [80,84,85], two used rabbits [86,90] and one used Wistar rats [89]. Similar to tendon healing studies, most animals were male. However, the tendon site and specific method of constructing animal models of tendon–bone healing studies are significantly different from those of tendon healing studies. The majority of studies resected the anterior cruciate ligament and created bone tunnels [81,82,83,89] or constructed tendon–bone injury models at the rotator cuff [85,86,87,88,90]. Only two studies damaged the enthesis of the Achilles tendon [80,84].

3.6. Group Assignment and Treatment Parameters of Animal Experiments

The detailed results of treatment parameters are shown in Supplementary Table S6 and Supplementary Table S7. Different concentrations of exosomes were used in different studies. Among all 46 studies [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,90], only 1 compared the effect of the concentration of exosomes on therapeutic efficacy [62]. Gissi et al. compared between 2.8 particles/mL and 8.4 particles/mL of exosomes. The studies reported that exosomes of high concentration (8.4 particles/mL) significantly promoted the expression of type I collagen fibers and inhibited the expression of type III collagen fibers, with higher histological scores and more obvious promotion of tendon healing [62]. However, even for this study, it only set up two different concentrations for comparison. There were no studies that set up multiple different concentration gradients to explore the most appropriate concentration for in vivo administration [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,90].

Direct injection and implantation with biomaterials are the two most common ways to deliver exosomes. Thirty-five studies used different injection methods, which included local injection, subcutaneous injection and intravenous injection [9,47,48,49,51,53,54,56,58,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,69,71,72,73,75,76,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,88,89,90]. Different from studies on tendon healing, whose injection site was the tendon, the injection sites of the studies on tendon–bone healing included a bone tunnel, joint cavity or the tendon–bone interface [9,47,48,49,51,53,54,56,58,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,69,71,72,73,75,76,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,88,89,90]. Ten studies used biomaterials which included collagen sheet, hydrogel, fibrin glue, fiber patch, type I collagen scaffold, collagen sponge and fibrin sealant to carry exosomes [8,50,52,55,57,59,70,74,77,87]. Although these delivery methods based on biomaterials were proven to be therapeutically effective and control groups in which animals were only treated with the biomaterials were used, no study used an additional group of animals only treated with exosomes to explore whether the biomaterials promote or inhibit the therapeutic efficacy of exosomes [8,50,52,55,57,59,70,74,77,87].

As for frequency of administration, only six studies conducted administration multiple times, and the frequencies were weekly, at day 1 and day 7, once every three days, twice a week, weekly, and day 0, day 3 and day 7, respectively [47,48,56,66,81,89]. Different from other studies, administration was initiated several weeks after model establishment in six studies to establish chronic injury animal models [57,75,76,79,88,90]. The optimal timing and frequency of administration in vivo remain to be investigated, as no studies compared the effects of different dosing times and dosing frequencies on the test results.

3.7. Methods of Modification to Improve the Biological Function of Exosomes

To enhance the biological function of exosomes, many strategies were used to precondition the MSCs or exosomes. Ten studies preconditioned MSCs before the isolation of exosomes [50,54,63,68,71,74,80,82,83,85]: Shen et al. preconditioned adipose MSCs with interferon-γ (IFN-γ) primers, Davies et al. compared the therapeutic effect of exosomes from FB (FAPs that have assumed a beige adipose tissue differentiation state) with exosomes from NFB (FAPs that did not assumed a beige adipose tissue differentiation state), Li et al. preconditioned human umbilical cord MSCs with hydroxycamptothecin, Yu et al. down-regulated circRNA-Ep400 of macrophages before the isolation of exosomes, Li et al. preconditioned bone marrow MSCs with Eugenol, Xu et al. preconditioned adipose MSCs with bioactive glasses, Wang et al. used bone marrow MSCs overexpressing Scleraxis (Scx) to isolate exosomes, Zhang et al. simulated the MSCs under hypoxia circumstance, Wu et al. used magnetically actuated MSCs, and Wu et al. preconditioned bone marrow MSCs with Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Stimulation (LIPUS) [50,54,63,68,71,74,80,82,83,85]. Three studies preconditioned exosomes before in vivo administration [53,86,89]: Liu et al. modified exosomes by a nitric oxide nanomotor, Han et al. treated exosomes with BMP-2-loaded microcapsules, and Li et al. overexpressed miR-23a-3p in bone marrow MSC exosomes [53,86,89]. All the studies above reported that pre-treated exosomes or exosomes secreted by pre-treated MSCs demonstrated better therapeutic effects, which meant the modifications were effective [50,53,54,63,68,71,74,80,82,83,85,86,89].

3.8. Histological Outcomes

The detailed results of key therapeutic outcomes were shown in Table 5 and Table 6 on tendon healing, the therapeutic effects of exosomes on different animal models were similar, while there were still some differences [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. In Achilles tendon injury models, animals treated with exosomes demonstrated higher fiber expression, higher histological scores, and collagen type I/III ratios close to that of normal tendons [9,48,49,50,55,59,61,62,63,64,69,74]. In addition, exosomes significantly inhibited the inflammatory reaction, inhibited the adhesion of tendon and surrounding tissues, promoted the maturation of blood vessels, and made the arrangement of fibers and blood vessels more orderly [9,48,49,50,55,59,61,62,63,64,69,74]. In patellar tendon injury models, exosomes increased the number of TSCs, increased the expression and deposition of type I collagen, and the density and arrangement of cells in the injured area were more similar to those of normal tendons [8,67,71,73,77]. The expression of type III collagen was promoted in the early stage while inhibited in the late stage [67]. In rotator cuff injury models, the treatment of exosomes significantly inhibited fat infiltration, promoted the formation of fibrocartilage, and made collagen fibers arrange more orderly [54,57,60,65,70,75,76]. The expression of type I collagen was promoted and the expression of type III collagen was suppressed [60]. In tendon injury models induced by carrageenan or collagenase, exosomes reduced the infiltration of inflammatory cells and inflammatory reaction, promoted the expression of type I collagen and the formation of the extracellular matrix (ECM), and inhibited the expression of type III collagen [47,51,53,58,66,72]. The remaining five studies reported that exosomes promoted the expression of type I collagen, inhibited the expression of type III collagen, promoted the proliferation and migration of fibroblasts and tenocytes, and induced peritendon fibrosis [52,56,68,78,79].

Table 5.

Summary of key therapeutic outcomes (tendon healing).

Table 6.

Summary of key therapeutic outcomes (tendon–bone healing).

Three kinds of animal models—ACL injury, rotator cuff injury and Achilles tendon injury—were established in eleven tendon–bone healing studies [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. In the ACL injury models, animals treated with exosomes demonstrated higher histological scores, higher expression of fibers and cartilage, lighter inflammatory reaction and better angiogenesis [81,82,83,89]. In the rotator cuff injury models, exosomes significantly inhibited fat infiltration, promoted the expression of fibrocartilage and type I collagen, and promoted angiogenesis, thus promoting the formation of ECM and accelerating the process of tendon–bone healing [85,86,87,88,90]. In contrast to the control group, which showed severe fatty infiltration and collagen disorder, the treatment of exosomes was effective [85,86,87,88,90]. In the Achilles tendon injury models, exosomes inhibited osteoclastogenesis and prevented osteolysis [80,84]. As the number of chondrocytes increased, collagen became arranged in order, and the transitional structure of the tendon–bone interface gradually formed [80,84].

On the whole, exosomes promoted the expression of type I collagen and fibrocartilage and optimized the arrangement of fibers and blood vessels, thus promoting the formation of ECM [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. At the same time, exosomes inhibited the expression of type III collagen and osteolysis and inhibited inflammatory reaction and fat infiltration, thus promoting tendon healing and tendon–bone healing [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. However, the roles of exosomes in inhibiting tendon adhesion and promoting peritendinous fibrosis were controversial in several studies, which are worth discussing [9,56,63,68].

3.9. Biomechanical Outcomes

Across the 11 studies on tendon–bone healing [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90], biomechanical outcomes were reported in 10 studies, which all showed positive effects on biomechanical properties [80,81,82,83,84,85,87,88,89,90]. The biomechanical test indexes included stiffness, ultimate failure load, Young’s modulus and stress [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90].

Similar to studies on tendon–bone healing, sixty-nine percent of studies on tendon healing reported biomechanical outcomes and the indexes also included stiffness, ultimate failure load, Young’s modulus and stress [8,9,47,51,52,55,56,57,59,60,61,63,64,65,66,67,68,72,73,74,75,76,77,79]. Interestingly, two studies used SWB (static weight-bearing) and PWT (paw-withdrawal threshold) to measure the extent of pain, and both of them reported that the SWB and PWT of groups treated with exosomes were obviously improved, which indicated that the pain induced by tendinopathy was significantly relived [47,51]. However, there were four studies that did not report obvious positive effects [9,56,59,63]. Yao et al. and Li et al. both studied the effect of exosomes on tendon adhesion, both of which reached the conclusion that there was not an obvious difference in biomechanical properties between groups [9,63]. Additionally, Cui et al. reported that the biomechanical properties of the group treated with exosomes and the control group showed few differences [56]. Wellings et al. reported that the promoting effect was not obvious [59]. Chamberlain et al. reported that even though exosomes promoted the biomechanical properties of the tendon, the effect of exosome-educated macrophages was better [64]. From the results reported in 34 articles [8,9,47,51,52,55,56,57,59,60,61,63,64,65,66,67,68,72,73,74,75,76,77,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,87,88,89,90], the role of exosomes in enhancing the biomechanical properties of tendons or tendon–bone interfaces is indisputable, but there are still some issues worth discussing.

3.10. Macroscopic Appearance and Morphological Outcomes

Some studies on tendon healing reported the macroscopic appearance of experimental animals, but most of the outcomes were limited to visual observation [9,53,56,60,63,67,70,72,73,74]. On the whole, the injured tendons treated with exosomes demonstrated better healing [9,53,56,60,63,67,70,72,73,74]. To be specific, Liu et al. reported that the inflammation areas were significantly decreased with the treatment of exosomes [53]. Yao et al., Li et al. and Jenner et al. reported that exosomes inhibited the adhesion of tendons and surrounding tissues effectively [9,63]. Wang et al. reported that the group treated with exosomes was similar to the sham group macroscopically, with a significant increase in the thickness of the supraspinatus tendon [60]. Xu et al. reported that the treatment of EVB reduced scarring and deleterious morphological changes of the Achilles tendon [74]. Cui et al. reported that exosomes promote the formation of fibrotic tissue [56]. Xu et al. and Jenner et al. confirmed that exosomes reduced the inflammatory reaction with the help of nuclear magnetic resonance imaging [70,72].

Six out of eleven studies of tendon–bone healing reported the macroscopic appearance and morphological outcomes [81,82,83,86,88,89]. Similarly, the macroscopic appearances of the tendon–bone interface of the groups treated with exosomes were better, as there was more fibrocartilage and collagen fibers were more orderly arranged [81,82,83,86,88,89]. The morphological analyses were mainly conducted by micro-CT [81,82,83,86,89], and two studies used X-ray to analyze in addition [83,89]. According to the outcomes of micro-CT and X-ray, the animals treated with exosomes showed smaller mean bone tunnel areas and higher BV/TV ratios, which provided strong evidence for exosomes promoting tendon–bone healing [81,82,83,86,89]. Additionally, Wu et al. reported that the trabecular thickness, trabecular number, trabecular separation, structure model index, and bone mineral density of groups treated with exosomes were significantly improved [83].

3.11. Macrophage Polarization and Regulation of Inflammatory Reaction

Twenty-three out of forty-six studies reported that exosomes significantly inhibited the inflammatory reaction, down-regulated the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and M1 macrophage markers which included TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, CD31, CD86, NGF, CCR7, COX-2 and NOS-2, up-regulated the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines and M2 macrophage markers which included CD163, CD206, IL-10 and TGF-β, and promoted M2 polarization of macrophages [47,49,50,51,52,53,58,61,64,65,74,75,76,77,78,79,81,84,86,87,88,89,90]. In terms of mechanism, Ye et al. reported that exosomes delivered DUSP2 and DUSP3 to macrophages and inhibited the activation of the P38 MAPK signaling pathway, thus promoting M2 polarization of macrophages [58].

3.12. MicroRNAs and Signaling Pathways

Multiple microRNAs and signaling pathways were reported to play important roles in tendon and tendon–bone healing. Across the 35 studies on tendon healing [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79], fourteen studies reported nine microRNAs and nine signaling pathways which were suggested to be important intermediate processes in the mechanisms of exosomes promoting tendon healing [8,9,49,51,55,56,58,63,67,68,69,74,77,78]. For instance, Zhang et al. reported that the activation of PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK1/2 signaling molecules might play an important role in tendon healing [49]. Tao et al. reported that with the treatment of exosomes, H19 regulated YAP phosphorylation and translocation through H19-pp1-YAP interaction, thus promoting tendon-related gene expression [8]. Gao et al. reported that exosomes inhibited the activation of mast cells via the HIF-1 signaling pathway and reduced pain induced by tendinopathy [51]. Yao et al. reported that HUMSC exosomes might manipulate p65 activity by delivering low-abundance miR-21a-3p, ultimately inhibiting tendon adhesion [9]. Cui et al. reported that miR-21-5p from exosomes acted on Smad7 to promote the proliferation and migration of tendon cells and fibroblasts [56]. Yao et al. reported that exosomes regulated the PTEN/mTOR/TGF-β1 pathway via miR-29a-3p, up-regulated the expression of tendon-related genes, promoted TSCs differentiation into the tendon, and thus promoted tendon healing [55]. Ye et al. reported that exosomes delivered DUSP2 and DUSP3 to macrophages and inhibited the activation of the P38 MAPK signaling pathway, thus promoting M2 polarization of macrophages [58]. Li et al. reported that HCPT-EVs up-regulated the expression of GRP78, CHOP and BAX, and down-regulated the expression of BCL-2, which might activate the ERS pathway to inhibit adhesion [63]. Song et al. reported that exosomes regulated cell proliferation, migration and tendon healing via mi-144-3 [67]. Yu et al. reported that exosomes containing circ-RNA-Ep400 secreted by M2 macrophages promoted peritendinous fibrosis via the miR-15b-5p/FGF-1/7/9 pathway [68]. Han et al. reported that HUMSC exosomes promoted tendon healing by down-regulating ARHGAP5 expression and activating RhoA via mir-27b-3p [69]. Xu et al. reported that HSA-miR-125a-5p, HSA-miR-199b-3p, and miR-92b-5p were highly expressed in EVB, and the first two regulated macrophage polarization and promoted angiogenesis [74]. Liu et al. reported that exosomes promoted TSC proliferation and migration by activating Smad2/3 and Smad1/5/9 signaling pathways [77]. Zhao et al. reported that exosomes inhibited IGFBP3 expression via miR-19a, promoted tendon cell proliferation and reduced apoptosis rate [78].

Across the eleven studies on tendon–bone healing [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90], five studies reported the roles of micro RNAs and signaling pathways [80,83,85,88,89]. Huang et al. reported that rat bone marrow MSC exosomes activated the Hippo signaling pathway through VEGF, which promoted the proliferation and migration of HUVECs (human umbilical vein endothelial cells) and thus promoted tendon–bone healing [88]. Wang et al. reported that exosomes secreted by Scx-overexpressing bone marrow MSCs targeted OCSTAMP and CXCL12 via miR-6924-5p, which inhibited osteolysis and thus promoted tendon–bone healing [80]. Li et al. reported that bone-marrow MSCs exosomes promoted M2 polarization of macrophages via miR-23a-3p [89]. Wu et al. reported that IONP-exosomes (exosomes derived from magnetically actuated bone morrow mesenchymal stem cells) promoted tendon–bone healing by down-regulating SMAD7 via miR-21-5p, promoting NIH3T3 fibroblast proliferation and migration, and up-regulating the expression of COL I, COL III, and -SMA [83]. Wu et al. reported that exosomes from bone marrow MSCs preconditioned by LIPUS promoted tendon–bone healing by up-regulating the expression of chondrogenic genes and down-regulating the expression of adipogenic genes via miR-140 [85].

In summary, exosomes promoted the expression of angiogenesis, cell proliferation, migration and differentiation, macrophage M2 polarization, chondrogenesis and collagen production via multiple microRNAs and signaling pathways, effectively promoting tendon healing and tendon–bone healing. As we know, exosomes contain a variety of proteins, RNAs, and growth factors [39,40,41]. So, these reported results are not surprising.

3.13. Changes in Gene Expression

Twenty-five studies reported that the treatment of exosomes altered the expression of multiple genes [9,49,50,52,53,55,56,61,63,67,68,71,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,83,84,85,86,87]. Expressions of several types of genes were up-regulated, including the type I collagen gene; the inhibitor of metalloproteinase gene, TIMP-1; chondrogenic genes, COL II and SOX-9; tenogenesis genes, TNMD, TNC, Scx, DCN and MKX; ECM genes, BGN and ACAN; fibroblast growth factor genes, FGF-1, FGF-7 and FGF-9; the cell proliferation gene, PCNA; osteogenic genes, RUNX2 and OCN; and anti-inflammatory genes, IL-10, IGF-1, IGF-2 and TGF–β [9,49,50,52,53,55,56,61,63,67,68,71,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,83,84,85,86,87]. Additionally, expressions of some genes were down-regulated, which included the type III collagen gene; metalloproteinase gene, MMP; proinflammatory genes, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1α and IL-1β; proapoptotic genes, Caspase-3 and IGFBP3; osteoclastogenic genes, ACP5, CALCR, NFATc1 and ITGB3; and adipogenic genes, Adipo, Retn and Pparg [9,49,50,52,53,55,56,61,63,67,68,71,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,83,84,85,86,87].

Interestingly, four studies reported that the expression of α-SMA was promoted [56,68,83], while three other studies reported the opposite conclusion [9,49,63]. This paradox may be related to proper fibrosis and excessive scarring, which will be discussed in the “Discussion” section.

3.14. In Vitro Experiment Outcomes (Cell Proliferation, Migration and Differentiation)

Some studies also provided results of in vitro cell experiments to further verify the conclusion of in vivo experiments [8,9,47,48,49,53,54,55,56,57,61,62,63,67,68,69,71,73,74,75,76,77,78,82,83,87,88]. Twenty-five studies reported that exosomes had a positive effect on the proliferation or/and migration or/and differentiation of a variety of cells which included tenocytes, TPSCs, TSCs, fibroblast, endothelial cells, HUVECs, bone marrow MSCs and osteoblasts [8,47,48,49,53,54,55,56,57,61,62,67,68,69,71,73,74,75,76,77,78,82,83,87,88]. Among these, five studies found that this positive effect was in a dose-dependent manner [49,51,61,69,76]. Ren et al. reported that purified exosome products significantly promoted the proliferation and migration of tenocytes and osteoblasts and accelerated the fusion of the two cells [87]. This was the only study that focused on the effect of exosomes on osteoblasts, which provided strong evidence that exosomes promoted tendon–bone healing [87]. Strangely, two studies about exosomes inhibiting tendon adhesion reported that exosomes inhibited the proliferation of fibroblasts, which deserves to be discussed [9,63]. On the whole, exosomes significantly promoted cell proliferation, migration and differentiation, and thus promoted tendon and tendon–bone healing.

4. Discussion

From the above results, it can be seen that exosomes can effectively promote tendon healing and tendon–bone healing, and their therapeutic efficacy is mainly manifested in the following ways: 1. Promoting cell proliferation and differentiation into tendon cells and chondrocytes. 2. Alleviating inflammatory reactions and providing a good microenvironment for tissue repair. 3. Promoting the expression of type I collagen and inhibiting the expression of type III collagen, thereby promoting tissue repair and reducing scar formation. 4. Improving the biomechanical properties of tendons and increasing the strength of the tendon–bone interface. In the following sections, we will mainly discuss: 1. The methods of improving the therapeutic efficacy of exosomes. 2. Separation and administration methods of exosomes. 3. Mechanisms of exosomes promoting tendon and bone healing. 4. Inconsistencies in existing studies and possible explanations.

4.1. The Most Suitable Source of Exosomes for Tendon and Tendon–Bone Healing

Across the forty-six studies, the exosomes used were from four species—humans, rats, mice and rabbits—and three studies used purified exosome products [8,9,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. As for the types of cells (most of which are MSCs), nine types were used, which included ASCs, IP-MSCs, BM-MSCs, TSPCs, HU-MSCs, TSCs, IPFP-MSCs, FAPs, and BMDMs. Although exosomes from different sources were proven effective, it is still important to discuss exosomes from which species and which kinds of cells are the most suitable. As obtaining MSCs from human tissue is convenient and rats are the most common experimental animals, it is noticeable that humans and rats are the two most common species, and BM-MSCs and ASCs are the two most common types of MSCs. Different kinds of MSCs have their own characteristics. For example, ASCs are abundant and easy to obtain [102]; TSCs have greater tenogenesis and proliferation capacity [103]; HU-MSCs cost less and take less time to obtain [104]. Martinez-Lorenzo et al. reported that MSCs from rabbits and sheep tissue demonstrated more capacity to differentiate into cartilage than human MSCs [105]. As the formation of fibrocartilage is essential in the process of tendon–bone healing, exosomes from rabbits or sheep MSCs may be better. However, no studies compare exosomes from different species and MSCs, and which kinds of MSCs are the most suitable for extraction of exosomes to treat injured tendons remains to be studied. Hayashi et al. reported that the therapeutic effects of EVs derived from bone marrow MSCs at passage 5 were better than those at passage 12 [48], which poses a new research direction: the appropriate passage number of MSCs used to obtain exosomes.

4.2. Modification of Exosomes or MSCs

Multiple studies proved that the efficacy of exosomes was affected by the culture conditions of MSCs and the modification of exosomes. Preconditioning MSCs with small molecules such as IFN-γ primers, hydroxycamptothecin and eugenol was proven to enhance the effect of exosomes [50,63,71]. Special culture conditions such as hypoxia circumstance, magnetic actuation and LIPUS made a positive influence on the potency of exosomes [82,83,85]. Modification of exosomes included preconditioning with small molecules, overexpressing certain factors or microRNAs and loading certain proteins, such as NO, BMP-2 and miR-23a-3p and circRNA-Ep400, which were also effective [53,68,86,89].

We speculate that preconditioning and special culture conditions promote the effect of exosomes mainly in the following two ways: 1. Promoting MSC differentiation in different directions and the expression of genes for tendon healing. 2. Changing the content of non-coding RNA and some functional proteins in exosomes, which, to a large extent, mediate the biological function of exosomes.

There is no denying that some special culture conditions such as hypoxia and low pH improve the production or potency of exosomes [106,107]. However, these extreme-culture conditions are not suitable for the mass production of exosomes, so new culture conditions remain to be explored. MicroRNA, small molecules and certain factors provide future research directions for studying the specific mechanism of exosomes promoting tendon and tendon–bone healing, which are worthy of attention.

4.3. Exosomes Isolation and Administration

In the included studies, the most common methods to isolate exosomes were differential centrifugation and ultracentrifugation. Ultracentrifugation is currently the gold standard for the isolation of exosomes, but it also has certain drawbacks: the time of the whole process is long and the purity of exosomes is low [108]. In addition to ultracentrifugation and differential centrifugation, which is also called gradient centrifugation, other methods for isolation include co-precipitation, size-exclusion chromatography, immunoaffinity capture and field flow fractionation [108,109,110,111]. Aside from NFA, DLS, NTA, TEM and AFM, which were reported in the included studies, methods to measure the physical characteristics also include scanning electron microscopy, cryo-electron microscopy, tunable resistive pulse sensing and single EV analysis [112,113,114,115].

It is well acknowledged that current methods for exosome purification are immature and imperfect, and the exosomes isolated were sometimes not completely pure. Additionally, there are some differences between the biogenesis of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. The volume of microcapsules is relatively large, and they are vesicular structures formed directly through cell germination. The volume of exosomes is small, and their formation process is relatively complex. Usually, cytoplasmic membranes sprout inward to form endosomes that encapsulate proteins and nucleic acids. Subsequently, multiple endosomes approach each other to form larger vesicles, known as a multivesicular body. Finally, the multivesicular body fuse with the plasma membrane and the released vesicles are exosomes. [116]. So, for tendon and tendon–bone healing, they may demonstrate different effects. As we mentioned before, Ye et al. reported that the therapeutic effects of exosomes and EVs were similar, while Xu et al. pointed out that exosomes demonstrated better therapeutic effects than ectosomes [58,72]. However, those comparisons are not convincing enough. More research is needed in this area.

In the included studies, injection was the most common method for the administration of exosomes, which included local injection, subcutaneous injection and intravenous injection. Obviously, with the flow of blood, exosomes could not maintain an effective concentration at the injured site for a long time, so it is not the best administration method. Ten studies used biomaterials which included collagen sheet, hydrogel, fibrin glue, fiber patch, type I collagen scaffold, collagen sponge and fibrin sealant to carry exosomes [8,50,52,55,57,59,70,74,77,87]. Compared with injection, administrating exosomes with biomaterials has some advantages. For example, Shi et al. reported that Tisseel plus a purified exosome product could release exosomes stably for over two weeks [52]. Additionally, hydrogel was also reported to prolong the release time of exosomes and thus improve their bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy [73]. In this way, even with a lower exosome concentration than in other studies, the therapeutic effects were still achieved [73]. Furthermore, a fiber-aligned patch could further promote tendon and tendon–bone healing by providing bioactive stimulation and mechanical support [57]. However, these studies only compare the groups treated with exosomes with biomaterials and groups only treated with biomaterials to prove the role of exosomes. An extra kind of group only treated with exosomes is also needed to demonstrate whether the biomaterials promote or inhibit the efficacy of exosomes. In addition, the promoting effects of different biomaterials on the exosomes also need to be compared. Choosing the most suitable biomaterial for the treatment of a tendon injury is extremely important.

The concentration of exosomes and the frequency of administration also varied across different studies. Although Gissi et al. reported that high-concentration exosomes showed better effects than low-concentration exosomes [62], the most appropriate concentration and frequency of administration still remain to be explored. Different concentration gradients of exosomes were set for in vitro experiments in some studies, which were also needed for in vivo experiments. Another important issue is that as exosomes contain a variety of bioactive components [39,40,41], exosomes are fragile in the external environment and have fragile biological activity. However, no studies monitored the biological activity of exosomes after administration, nor did studies explore the pharmacokinetics of exosomes in vivo after administration. In future research, exosomes with different concentration gradients can be applied to cells or animal models, and their content changes should be monitored over a certain period of time. We can further evaluate the efficacy of exosomes through pharmacokinetic results.

4.4. Animal Models

Across studies on tendon healing, Achilles tendon injury models were the most common, while ACL injury models and rotator cuff injury models were the most common in tendon–bone healing studies. This is reasonable as ACL and rotator cuff injuries are usually accompanied by the separation of tendon and bone. In six studies, administration was initiated several weeks after model establishment to establish chronic injury animal models [57,75,76,79,88,90]. Other studies simulated acute tendon injury. However, many chronic tendon injuries in daily life are natural degenerative processes, especially for the elderly. Among the studies included, only one study used a treadmill to train animals to simulate this process [79]. Therefore, the role of exosomes in alleviating tendon degeneration needs further research. It is significant to point out that the animals used for in vivo experiments are relatively young. However, the incidence rate of tendinopathy-like rotator cuff tears is higher in the elderly [90]. More importantly, except for one study which chose sheep to establish animal models [70], animal models in other studies were established on small animals. The problem may be that the healing time of tendon injury in rats is relatively small, which could not completely reflect the healing process of tendon injuries in humans [81]. Therefore, the experiment also needs to be verified in larger animals.

Common biomechanical test indexes included stiffness, ultimate failure load, Young’s modulus and stress. Only two studies used SWB and PWT to measure the extent of pain [47,51]. The evaluation of pain could further evaluate the treatment effect, which is worth carrying out. So, in future studies, the degree of pain could be evaluated before killing animals and taking tendons for biomechanical tests.

4.5. Mechanism of Exosomes Promoting Tendon Healing

Although no studies reported the exact mechanisms through which exosomes played their therapeutic roles in tendon and tendon–bone healing, we could still obtain some insights from a large number of reported microRNA, signaling pathways and changes of phenotypes in cells and animals.

The mechanism of exosomes promoting tendon healing can be summarized in the following three ways: 1. Inhibiting inflammatory reaction and regulating macrophage polarization. 2. Promoting the migration and proliferation of tenocytes, up-regulating the expression of collagen fibers, regulating the ratio of type I/III collagen and reducing scar formation. 3. Promoting the expression of tenogenesis factors and cytokines, reconstructing the ECM.

Firstly, exosomes could significantly inhibit the inflammatory reaction and promote the M2 polarization of macrophages. It was reported that M1 macrophages could eradicate harmful bacteria and simulate inflammatory reactions [117]. In general, the number of M1 macrophages increases significantly at the early stage of tendon injury [118]. TNF-α and IL-6 are common makers of M1 macrophages, which are closely related to the NF-κB pathway, and have strong pro-inflammatory effects [119,120]. M2 macrophages could secrete IL-10, a kind of anti-inflammatory factor to inhibit inflammatory reactions [121]. In addition, M2 macrophages could secrete TGF-β and VEGF, which promote tissue repair and the formation of ECM [121,122]. Therefore, M1 macrophages are not conducive to tendon healing, while M2 macrophages promote tendon healing. A number of included studies reported that exosomes down-regulated the expression of M1 macrophage makers and pro-inflammatory factors, up-regulated the expression of M2 macrophage makers and anti-inflammatory factors, promoted M2 polarization of macrophages and significantly inhibited the inflammatory reaction [47,49,50,51,52,53,58,61,64,65,74,75,76,77,78,79]. As for how exosomes regulate the process of polarization, Ye et al. reported that exosomes delivered DUSP2 and DUSP3 to macrophages and inhibited the activation of the P38 MAPK signaling pathway, thus promoting M2 polarization of macrophages [58]. However, more specific mechanisms remain to be further studied.

Secondly, exosomes could improve the histological characteristics of the tendon. Studies have reported that exosomes could promote the migration, proliferation and fibrosis of tenocytes, thus promoting tendon healing [56,67,123,124,125]. This process is closely related to TGF-β1, VEGFA and several kinds of microRNA. Exosomes could promote the expression of collagen fibers, make the fibers more orderly and increase the ratio of type I/III collagen [59,72]. The most abundant collagen in a tendon is type I collagen, which has a stiff structure and good strength [126]. However, after tendon injury, the expression of both type I collagen and type III collagen increases, and type III collagen is mainly present in scars [127,128]. Exosomes promote tendon healing while reducing scar formation [59,72]. Therefore, improving the histological characteristics of tendons is also one of the mechanisms of exosomes promoting tendon healing.

In addition, exosomes promote the expression of tenogenesis factors and cytokines, reconstructing the ECM. Exosomes can promote the expression of tenogenesis genes such as TNMD, TNC, Scx, DCN and MKX, and ECM genes such as BGN and ACAN, while inhibiting the expression of metalloproteinase genes. It is the expression changes of these genes that increase the synthesis of matrix and fibers, while reducing their degradation, which contributes to the formation of ECM and provides a favorable environment for the proliferation and migration of tendon cells, thus promoting tendon healing [50,55,61,71,73].

4.6. Mechanism of Exosomes Promoting Tendon–Bone Healing

The mechanism of exosomes promoting tendon–bone healing can be summarized in the following four ways: 1. Inhibiting inflammatory reaction and regulating macrophage polarization. 2. Promoting the expression of some cytokines, thus promoting the reconstruction of cell phenotype gradients at the tendon–bone interface. 3. Promoting the expression of bone metabolism factors, thus promoting osteogenesis and inhibiting osteolysis. 4. Promoting angiogenesis.

Similar to tendon healing, exosomes promoting M2 polarization of macrophages and inhibiting inflammatory reactions also play an important role in tendon–bone healing. Seven studies of tendon–bone healing reported this effect [81,84,86,87,88,89,90], which is one of the mechanisms of exosomes promoting tendon–bone healing.

Exosomes promote the expression of some cytokines, thus promoting the reconstruction of cell phenotype gradients at the tendon–bone interface. As we know, the tendon–bone interface is a gradient structure that can be divided into four layers [20]. It is the gradient structure that can disperse the stress and make the tendon–bone interface have some mechanical strength [22]. Exosomes promoted the expression of Scx and SOX-9 [77,86,87], which were reported to regulate the differentiation of progenitor cells and promote the establishment of cell phenotype gradients of the tendon–bone interface [22,129]. Multiple studies have reported that the hedgehog proteins and the hedgehog signaling pathway played a significant role in the reconstruction of the tendon–bone interface gradient [130,131,132]. However, no studies have reported whether there is a regulatory relationship between exosomes and hedgehog proteins. For future research, we suggest changing the expression level of exosomes while detecting the expression level of hedgehog proteins to determine whether there is a regulatory relationship between the two. If the regulatory relationship exists, it is possible to upregulate the expression of exosomes while inhibiting the expression of hedgehog proteins to determine whether exosomes promote tendon healing through hedgehog proteins. Exosomes also promoted the expression of collagen fibers and ECM components [84,86]. For example, COL II is related to chondrogenesis, and Smad and other proteins regulate cell transcription through multiple signaling pathways, thus promoting the formation of ECM components and cell phenotype gradient at the tendon–bone interface [133,134].

Additionally, exosomes promote the expression of bone metabolism factors, thus promoting osteogenesis and inhibiting osteolysis. A previous study reported that osteolysis or bone loss decreased the stiffness and strength of the tendon–bone interface, which was not conducive to tendon–bone healing [135]. Therefore, promoting osteogenesis and inhibiting osteolysis are significant in tendon–bone healing. Several studies have reported exosomes promoted tendon–bone healing by promoting osteogenesis and inhibiting osteolysis [76,80,86,87]. Wang et al. reported that exosomes secreted by Scx-overexpressing BM-MSCs targeted OCSTAMP and CXCL12 via miR-6924-5p, which inhibited osteolysis and thus promoted tendon–bone healing. The expression of osteoclast markers such as ACP5, CALCR, NFATc1 and ITGB3 was also suppressed [80]. Han et al. reported that exosomes with BMP-2 promoted the expression of RUNX2 and Smad, improved the strength of the tendon–bone interface, and promoted tendon–bone healing through the Smad/RUNX2 pathway [86]. Ren et al. reported that purified exosome products promoted the proliferation, migration and fusion of tenocytes and osteoblasts in vitro [87]. Fu et al. reported that exosomes promoted the expression of RUNX2, SOX-9, and TNC, which regulated osteogenesis, chondrogenesis and tenogenesis [76].

Finally, angiogenesis is also one of the significant mechanisms of exosomes promoting tendon–bone healing. One of the difficulties in tendon–bone healing is that there are few vessels at the tendon–bone interface [24]. Blood vessels provide adequate oxygen and nutrients and remove metabolic wastes effectively, which may contribute to the formation of cell phenotype gradients [136]. Therefore, angiogenesis is crucial in the process of tendon–bone healing. However, few studies have reported that exosomes promote angiogenesis and thus promote tendon–bone healing. Huang et al. reported that animals treated with exosomes had more neovascularization at the injured site [88]. In their in vitro experiment, they found that exosomes activated the Hippo signaling pathway through VGEF, which promoted the proliferation and migration of HUVECs [88]. In the future, the role of angiogenesis in exosomes promoting tendon–bone healing needs to be further studied. In current studies, it is rare to see study on the role of angiogenesis in tendon–bone healing in animal models. Future researchers can consider making breakthroughs in this area.

4.7. Inconsistency and Possible Explanations

4.7.1. Inconsistency between Different Studies

It was mentioned before that the roles of exosomes in tendon adhesion and peritendinous fibrosis were controversial in several studies and the expression of α-SMA was up-regulated in some studies while down-regulated in some other studies [9,49,56,63,68,83]. Previous studies have reported that TGF-β1 promoted the expression of α-SMA and the proliferation of fibroblasts, and thus enhanced the formation of ECM and tendon adhesion [125,137]. Yao et al. reported that exosomes inhibited the roles of TGF-β1 and thus inhibited the proliferation of fibroblasts via miR-21a-3p [9]. Similarly, Li et al. also reported that exosomes inhibited the promoting effects of TGF-β on the proliferation of fibroblasts and the expression of α-SMA [63]. Conversely, Cui et al. reported that miR-21-5p in exosomes from macrophages targeted and inhibited Smad7, resulting in the activation of the TGF-β1 signaling pathway, and thus the migration and proliferation of tenocytes and fibroblasts were promoted [56]. Yu et al. reported that circRNA-Ep400 was expressed in exosomes from M2 macrophages, and the exosomes promoted the expression of TGF-β1 and peritendinous fibrosis via the miR-15b-5p/FGF-1/7/9 pathway [68]. Wu et al. also reported that miR-21-5p was abundant in IONP-exosomes, which targeted Smad7 and activated the TGF-β1/Smad pathway, thus promoting the formation of ECM and tissue fibrosis [83]. Zhang et al. also reported that the expression of α-SMA was down-regulated but did not explore the mechanism [49].

4.7.2. Reasonable Explanations

We could draw a preliminary conclusion that exosomes from different sources contain different non-coding RNAs, which may act on different signaling pathways, and thus promote or inhibit the function of TGF-β1. Therefore, different exosomes may have different effects on peritendinous fibrosis and the expression of α-SMA. It is evident that miR-21-5p and circRNA-Ep400 up-regulate TGF-β1 activity and promote peritendinous fibrosis, while miR-21a-3p negatively regulates TGF-β1 activity and inhibits peritendinous fibrosis. We have mentioned before that there were few differences between the biomechanical outcomes of groups in these studies [9,56,63]. We speculate that exosomes promoted tendon fibrosis and adhesion, which maintained the mechanical strength of the tendon. A study reported that TGF-β1 also promoted scar formation, and inhibition of expression of α-SMA may be related to the inhibition of scar formation [138]. That exosomes inhibit scar formation seems to be a reasonable explanation. So, different exosomes can mediate TGF-β1 to play different roles, which may be related to the sources, concentration, and acting time of exosomes. However, the exact mechanism remains to be explored.

4.7.3. Future Research Directions

It is clear that exosomes have both advantages and disadvantages for tendon and tendon–bone healing. In some cases, exosomes promote the expression of collagen fibers and fibrocartilage while inhibiting the adhesion of the tendon and surrounding tissues, thus promoting tendon and tendon–bone healing. However, in other cases, exosomes may excessively promote fibrosis, leading to the adhesion of a tendon and scar formation. This may be related to the source, concentration, acting time and the type of non-coding RNA of exosomes, which is a significant research direction in the future. With the continuous development of technology, the application of computational simulation and computer technology in medical science research is becoming increasingly widespread. Computer technology has lower costs and faster results, and the full application of computer technology can further verify the reliability of preclinical and clinical studies. Therefore, computer technology has broad application prospects and needs to be paid attention to in future research.

4.8. Limitations

Our systematic review also has some limitations. Firstly, the quality of studies included limited the persuasiveness of this review. Few studies reported the methodology of sequence generation, allocation concealment, random housing or blinding methods. There were some unclear risks in these studies according to the SYRCLE risk of bias assessment tool [101]. Therefore, standardization of outcome reporting should be established, and more detailed documentation of the methodology should be demonstrated in future studies. Secondly, researchers still lack a certain understanding of exosomes as a therapeutic drug. The most suitable source, isolation methods, concentration and administration frequency of exosomes are still unknown. The results of the included studies are not convincing enough. Furthermore, the monitoring of biological activity changes and the pharmacokinetics of exosomes were lacking in the studies. Thirdly, the animal models of studies also limit the power of this review. The animals used to establish the tendon injury models were relatively small and young, which cannot simulate the complete process of tendon healing in humans. Additionally, the biomechanical test indexes need to be improved. Finally, the heterogeneity of the reporting form of outcomes precluded a more rigorous analysis of the studies. Due to the lack of uniform reports of the outcomes, especially quantitative reports, this systematic review cannot use meta-analysis to further analyze the results. In the future, the reports on the methodology and outcomes need to be standardized. In this way, more conclusions could be drawn from the studies.

5. Conclusions

We systematically assessed the existing preclinical animal studies on tendon and tendon–bone healing, and demonstrated that it is promising to use exosomes to promote tendon healing and tendon–bone healing. These findings provide basic support for the clinical translation of exosomes as a tendon and tendon–bone healing therapy. For future work, researchers can focus on the following aspects: 1. Specific mechanisms by which pre-conditioning of MSCs or exosomes enhances the therapeutic effect of exosomes. 2. The most suitable method, concentration, and frequency of the administration of exosomes. 3. Researchers can use larger animal models to simulate human tendon injuries more realistically. 4. The detailed molecular biological mechanisms of exosomes promoting tendon healing and tendon–bone healing. 5. Using computer technology to simulate clinical and preclinical studies. However, the unclear-to-low risk of bias highlights the significance of the standardization of outcome reporting. Further preclinical studies are still needed to produce the most suitable exosomes which promote tendon and tendon–bone healing while inhibiting adhesion and scar formation for future clinical studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jfb14060299/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 checklist; Table S2: Specific search Strategy; Table S3: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria; Table S4: Risk of bias assessed using SYRCLE risk of bias assessment tool; Table S5: Summary of parameters of exosomes (tendon healing and tendon–bone healing); Table S6: Summary of animal studies and treatment parameters (tendon healing); Table S7: Summary of animal studies and treatment parameters (tendon–bone healing).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, resources and data curation, M.Z. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.; Writing—review and editing, M.Z. and Z.S.; supervision, funding acquisition, Z.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81871770) and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (L222094).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviation

RCT, rotator cuff tear; ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; TSC, tendon stem cell; TSPCs, tendon stem/progenitor cells; BMDM, bone-marrow-derived macrophages; FAP, Fibroadipogenic progenitor; EVs, extracellular vesicles; P5 EVs, extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stem cell at passage 5; P12 EVs, extracellular vesicles from mesenchymal stem cell at passage 12; NFA, Nano-flow analysis; DLS, Dynamic Light Scattering; FCM, Flow Cytometry; AFM Atomic Force Microscopy; CONAN Colloidal Nano plasmonic assay; C57BL/6J, C57 black 6 Jackson Laboratory; ASCs, Adipose stem cells; FB, FAPs that have assumed a beige adipose tissue differentiation state; HU-MSCs, Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells; BM-MSCs, bone morrow mesenchymal stem cells; Scx, Scleraxis; LIPUS, Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Stimulation; BMP, Bone morphogenetic protein; SWB, static weight-bearing; PWT, paw withdrawal threshold; EVB, bioactive glasses-elicited mesenchymal stem cell extracellular vesicle; MRI, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Imaging; micro-CT; BV/TV, bone volume/total volume; Tb. Th, trabecular thickness; Tb. N, trabecular number; Tb. SP, trabecular separation; SMI, structure model index; BMD, bone mineral density; NGF, Nerve growth factor; NOS, Nitric Oxide Synthase; IL, interleukin; TGF-β1: Transforming growth factor-β1; DUSP, Dual Specificity Phosphatase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; PI3K, Phosphatidylinositol3-kinase; AKT, protein kinase B; ERK, extracellular regulated protein kinases; YAP, yes-associated protein; HIF-1, Hypoxia-inducible factor-1; Smad, Mothers Against Decapentaplegic Homolog; PTEN: Phosphatase and tensin homolog; mTOR, mammalian Target of Rapamycin; HCPT, hydroxycamptothecin; GRP, glucose regulated protein; ERS: Endoplasmic reticulum stress; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; ARHGAP, Rho GTPase activating protein; HSA, Human Serum Albumin; IGFBP, Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; VEGF, Vascular endothelial growth factor; IONP-exosomes, Exosomes derived from magnetically actuated bone morrow mesenchymal stem cells; LIPUS-BM-MSC, Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Preconditioned by Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Stimulation; TNMD, TNC, Tenascin C; DCN, Decorin; MKX, Mohawk; ECM, Extracellular matrix; BGN, biglycan; ACAN, Aggrecan; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; OCN, osteocalcin; RUNX, Runt-related Transcription Factor; IGF, Insulin-like Growth Factor; MMP, Matrix metalloproteinases; Adipo, adiponectin; Retn, resistin; Pparg, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-g; SEM, Scanning electron microscopy; CEM, Cyro-electron microscopy; TRPS, Tunable resistive pulse sensing; SEA, Single EV Analysis.

References

- Lim, W.L.; Liau, L.L.; Ng, M.H.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Law, J.X. Current Progress in Tendon and Ligament Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 16, 549–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Rothrauff, B.B.; Tuan, R.S. Tendon and Ligament Regeneration and Repair: Clinical Relevance and Developmental Paradigm. Birth Defects Res. Part C-Embryo Today-Rev. 2013, 99, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voleti, P.B.; Buckley, M.R.; Soslowsky, L.J. Tendon healing: Repair and regeneration. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 14, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacevic, D.; Rodeo, S.A. Biological augmentation of rotator cuff tendon repair. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008, 466, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.H.; Agrawal, D.K.; Thankam, F.G. “Smart Exosomes”: A Smart Approach for Tendon Regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part B-Rev. 2022, 28, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jin, M.; He, H.; Dong, J.; Li, J.; Nie, J.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Wu, F. Mesenchymal stem cells and macrophages and their interactions in tendon-bone healing. J. Orthop. Translat. 2023, 39, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Maffulli, N. Biology of tendon injury: Healing, modeling and remodeling. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2006, 6, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, S.C.; Huang, J.Y.; Li, Z.X.; Zhan, S.; Guo, S.C. Small extracellular vesicles with LncRNA H19 “overload”: YAP Regulation as a Tendon Repair Therapeutic Tactic. iScience 2021, 24, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Peng, S.; Ning, J.; Qian, Y.; Fan, C. Microrna-21-3p engineered umbilical cord stem cell-derived exosomes inhibit tendon adhesion. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 13, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Franceschi, F.; Berton, A.; Maffulli, N.; Droena, V. Conservative treatment and rotator cuff tear progression. Med. Sport Sci. 2012, 57, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Benedetto, P.; Di Benedetto, E.; Fiocchi, A.; Beltrame, A.; Causero, A. Causes of Failure of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction and Revision Surgical Strategies. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2016, 28, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanopoulos, I.; Ilias, A.; Karliaftis, K.; Papadopoulos, D.; Ashwood, N. The Impact of Re-tear on the Clinical Outcome after Rotator Cuff Repair Using Open or Arthroscopic Techniques—A Systematic Review. Open Orthop. J. 2017, 11, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, S.; Del Castillo, J.; Moatshe, G.; LaPrade, R.F. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction failure and revision surgery: Current concepts. J. Isakos Jt. Disord. Orthop. Sport. Med. 2020, 5, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadakia, A.R.; Dekker, R.G., 2nd; Ho, B.S. Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures: An Update on Treatment. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2017, 25, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, J.A.; Yablon, C.M.; Henning, P.T.; Kazmers, I.S.; Urquhart, A.; Hallstrom, B.; Bedi, A.; Parameswaran, A. Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: Percutaneous Tendon Fenestration Versus Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection for Treatment of Gluteal Tendinosis. J. Ultrasound Med. 2016, 35, 2413–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, S.F.; Olewinski, L.H.; Tamminga, K.S. Management of Chronic Tendon Injuries. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 100, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Skjong, C.C.; Meininger, A.K.; Ho, S.S. Tendinopathy treatment: Where is the evidence? Clin. Sport. Med. 2012, 31, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimenti, R.L.; Stover, D.W.; Fick, B.S.; Hall, M.M. Percutaneous Ultrasonic Tenotomy Reduces Insertional Achilles Tendinopathy Pain With High Patient Satisfaction and a Low Complication Rate. J. Ultrasound Med. 2019, 38, 1629–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, J.; Bulsara, M.; Zheng, M.H. The Effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Tendinopathy: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Am. J. Sport. Med. 2017, 45, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killian, M.L. Growth and mechanobiology of the tendon-bone enthesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 123, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffino, S.; Camy, C.; Foucault-Bertaud, A.; Lamy, E.; Pithioux, M.; Chopard, A. Negative impact of disuse and unloading on tendon enthesis structure and function. Life Sci. Space Res. 2021, 29, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]