Abstract

In many therapeutic settings, remote health services are becoming increasingly a viable strategy for behavior management interventions in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). However, there is a paucity of tools for recovering social-pragmatic skills. In this study, we sought to demonstrate the effectiveness of a new online behavioral training, comparing the performance of an ASD group carrying out an online treatment (n°8) with respect to a control group of demographically-/clinically matched ASD children (n°8) engaged in a traditional in-presence intervention (face-to-face). After a 4-month behavioral treatment, the pragmatic skills language (APL test) abilities detected in the experimental group were almost similar to the control group. However, principal component analysis (PCA) demonstrated that the overall improvement in socio-pragmatic skills was higher for ASD children who underwent in-presence training. In fact, dimensions defined by merging APL subscale scores are clearly separated in ASD children who underwent in-presence training with respect to those performing the online approach. Our findings support the effectiveness of remote healthcare systems in managing the social skills of children with ASD, but more approaches and resources are required to enhance remote services.

1. Introduction

After the new era of pandemic emergencies, telehealth systems have become a fundamental service for pursuing and maintaining healthcare protocols. In neurological diseases, such as Parkinson’s [1,2]; Alzheimer’s [3,4] and Multiple Sclerosis [5,6], a large number of tools and services have been proposed.

A clinical domain where the definition of new remote health assistance is mandatory refers to children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Indeed, in ASD the need for developing this kind of assistance emerged only after the first COVID-19 pandemic waves. In the last few years, ASD therapy delivery methods using telehealth have been researched, firstly looking at how these technologies might enhance diagnostic testing by providing strategies to assist families in gathering clinically pertinent movies at home and distributing them to diagnostic specialists using telehealth tools [7,8]. Moreover, several authors have demonstrated the effectiveness of telehealth approaches for promoting parent training programs [9,10,11], reducing behavior problems [12] and teaching communication skills [13], and reporting better cognitive and behavioral performance after telehealth protocols, similar to that reached during in-person treatments. Moreover, parents of children with ASD report positive feelings of empowerment [14] and high satisfaction with the use of telemedicine [15,16].

The vast majority of protocols translated on telematic systems with subjects with ASD concern the enhancement of specific domains: social skills [16,17,18,19], parent training [9,19,20], verbal communication [21], and behavioral problems [12,22]. On the other hand, the rehabilitation of social-pragmatic skills has been sparsely translated into telehealth protocols. Pragmatics is widely considered the domain that is distinctively and uniformly lacking in ASD. Problems with pragmatic language (i.e., the appropriate social use of language) continue in ASD even when structural language appears to be intact. A pragmatic language impairment is characterized by a mismatch between the language used and the context in which it is used, such that it is somehow unsuitable for the needs of the circumstance [23]. Some promising approaches have been proposed to treat these deficits, demonstrating that the active involvement of the child and parent in the intervention was found to be a key mediator of the intervention effect [24]. The vast majority of previous protocols have been validated for in-presence treatments. For this reason, a remote assistance protocol focused on this specific deficit is mandatory.

For this reason, this study is aimed at validating a new telehealth program for the recovery of social-pragmatic skills in ASD using an RCT approach, comparing the performance of an ASD group carrying out an online treatment with respect to a control group of ASD children engaged in a traditional in-presence intervention (face-to-face). The current study adds to this literature with the employment of a new remote online tool for improving social-pragmatic abilities in ASD children and with a comparison of behavioral performance analyzed by means of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for increasing the interpretability and enabling the visualization of data in a new multidimensional way.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Enrollment

Children were recruited and tested at the clinical facilities of the Institute for Biomedical Research and Innovation of the National Research Council of Italy (IRIB-CNR) in Messina. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) between 8 and 13 years of age; (2) clinical diagnosis of ASD based on the DSM-5 criteria from a licensed clinical child neuropsychiatrist; (3) a verbal and performance Intelligence Quotient above 75 [25], as assessed by the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-4th edition (WISC-IV); (4) no current problems with aggressive behavior or severe oppositional tendency; (5) no hearing, visual, or physical disabilities that would prevent participation in the intervention; (6) not being on psychiatric medication. All participants have a previous diagnosis that was further confirmed through the assessment and the consensus of experienced professionals on the research team (i.e., a child neuropsychiatrist and a clinical psychologist).

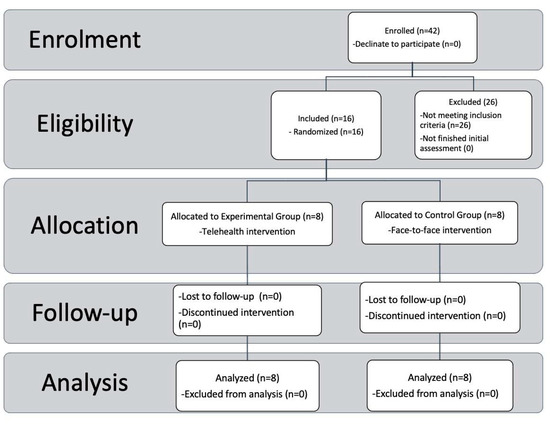

From an initial sample of 42 ASD children, n = 26 were excluded because they did not meet the study inclusion criteria. Sixteen children fully met the admission criteria and were enrolled in the present study. Experimental and control groups were pair matched according to demographic variables. All children completed all phases of the rehabilitation protocols and were included in the statistical analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Subject recruitment assignment, and assignment procedures. CONSORT Flow diagram showing the phases of a parallel randomized trial of two groups of ASD individuals underwent telehealth (experimental group) or traditional (control) interventions.

2.2. Study Design

The objective of the study was to enhance and develop pragmatic skills in children, diagnosed with ASD, aged 8 to 13 years. A single-blind, randomized controlled study was conducted as part of an ongoing research program and tested at our clinical facilities within the Project INTER PARES “Inclusione, Tecnologie e Rete: un Progetto per l’Autismo fra Ricerca, E-health e Sociale”—POC Metro 2014–2020, Municipality of Messina, ME 1.3.1.b, CUP F49J18000370006, CIG 7828294093. The study’s recruiting of ASD children was the focus of the first phase. Then, at baseline (T0), eligible people received a clinical evaluation. Using a computer-generated randomization code, participants were split into two groups at random in the third stage. The physicians (who conducted the clinical baseline assessment (T0) and post-treatment examination (T1)), were blinded to the parents’ group affiliation. Participants in the experimental group completed a Web intervention of social pragmatic skills, whereas children assigned to the control group underwent the same protocol in a face-to-face approach. At the end of treatment, participants from both groups were given a final evaluation (T1), using the same protocol as the baseline. Four therapists were involved in the different phases of treatment with distinct roles. One therapist (C.F.) was responsible for implementing the protocol in the online setting, another for in-person therapy (P.C.), and two others (R.M., N.V.) for conducting blind evaluations before and after treatment.

2.3. Treatment

Following an Italian well-validated protocol for ASD children [26], the treatment was thought to increase the ability to understand the speaker’s intentions and the use of non-literal linguistic expressions. ASD children were trained on 13 specific categories (Table 1) during two sessions characterized by two video training. Each video is made up of drawings of animated animals as if they were cartoons. Two questions are asked at the end of each video. The first is used to understand whether the child has correctly interpreted the general meaning of the story; the second is used to determine the degree to which the child is aware that the expression must be intense in a nonliteral sense.

Table 1.

Video Training.

The training sessions were carried out following a rigid order (Table 2). In summary, the first step is devoted to improving group social skills. The beginning of the session was devoted to greetings among participants and social interest questions. During the second step, videos were administered and participants answered the target questions, in order to understand if the child has correctly interpreted the general meaning of the story, and to determine the degree to which the child is aware that the expression must be understood in a non-literal sense. In the third step, a role-play was performed among the participants by re-enacting the situations seen in the videos by having all group members take turns participating. During the last step, participants were prompted to share experiences from their lives in which they used or could use the pragmatic skill just analyzed. For the experimental group involved in the telehealth protocol, the training sessions were similar. The online protocol was carried out via a web platform [G-Suite; Google LLC; Mountain View, CA, USA] that provided access to video conferencing tools. The protocol sessions were carried out by children and therapists via videoconference twice a week. Two face-to-face meetings were held during the pre and post-intervention phases to assess socio-pragmatic skills.

Table 2.

Training sessions.

2.4. Protocol Phases

The experimental protocol consisted of a total of fifteen phases (see Table 3) divided into 31 sessions/meetings. The training phases lasted 45 min each, twice a week.

Table 3.

Protocol structure.

During phase 0, a meeting was organized with the families, where the therapists explained the research objectives and collected consent to participate in the study. At this stage, parents were informed that if their children met the inclusion criteria for the study, two ways of working would be formed: face-to-face treatment and online group treatment.

During phase 1, two meetings were held to assess the subjects with ASD by administering an intelligence test (WISC) to obtain information on the overall level of functioning and one specific test to evaluate the specific difficulty in the sociopragmatic language (APL-MEDEA). At the end of the assessment phase, the subjects were divided into two groups, face-to-face treatment and online treatment. In particular, two groups of four subjects carried out the classic face-to-face training, and two groups of four subjects carried out the treatment online together with a therapist.

From phase 2 to phase 14 ASD children underwent the 13 training phases described above.

During the last step, phase 15, two blind therapists performed a new evaluation of cognitive performance using the same battery employed at baseline.

2.5. Training Experience and Setting

The therapists who delivered the interventions were all chartered psychologists, or psychotherapists, with behavioral analyst training and at least 5 years of experience in working with ASD children.

The setting for in-person therapy sessions was characterized by a therapy room equipped with a television that is used to broadcast videos related to each phase of the therapy protocol. This provides a dedicated space for participants to focus on their therapy and receive the necessary support and guidance. For online therapy, parents of participants are encouraged to place their children in a room without any distractions. This means creating an environment that is free from noise, other people, and televisions. This quiet setting helps the child to concentrate on their therapy, ensuring that they receive the full benefits of the therapy sessions. Prior to the beginning of the protocol, the therapist and parent established home settings (such as the family room, kitchen, and bedroom) where the laptop may be put for the best viewing. The therapist could then watch a variety of parent-child behaviors and interactions without having to stop what they were doing to ask the parent to adjust the monitor.

2.6. Outcome Measurements

The only outcome measure was collected through the administration of a standardized language pragmatics test (APL-MEDEA). Pragmatic Skills Language (APL Medea) [27]) is a pragmatic language skills assessment battery measuring the ability to communicate effectively, taking into account the context, the communicative situation, and the interlocutor’s knowledge. The battery was designed to investigate how pragmatic language skills develop and progress between the ages of 5 and 14.

The battery consists of five sub-tests:

- Metaphors (M), divided into Verbal Metaphors (MV) and Figured Metaphors (MF): investigate the ability to understand metaphorical language.

- Understanding of implied meaning (CSI): evaluates the ability to draw inferences on non-explicit content.

- Comics (C): evaluates the ability to understand and respect the dialogic structure in communication.

- Situations (S): evaluates the ability to understand and embrace the meaning assumed by particular expressions in social interaction.

- The color game (CG): evaluates the ability to use language in a referential way and to use skills related to the “Theory of Mind”.

This battery is useful for providing a quantitative assessment of pragmatic skills in understanding and using verbal language.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Univariate analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (Version 4.1.2—R Core Team; https://www.R-project.org/; access date: 1 October 2022). Firstly, the pragmatic language abilities of the two groups were compared at time T0 in order to exclude significant differences before the treatment.

A statistical power analysis was performed for the estimation of the sample size (G*Power, 3.1; https://www.psychologie.hhu.de (accessed on 1 January 2022). The analysis was based on our clinical experience together with the lack of similar studies in the literature. To estimate the variables for computing power, we considered (1) the average score for typical children from the APL-MEDEA standardization; (2) the average score for children with ASD and normal intelligence from our database; (3) the average age of the participants and; (4) the average differences between ASD and typical participants on the five subscales; (5) we calculated a ‘best case’ scenario with post-training scores in the normal range and a ‘fair case’ scenario with post-training scores at the midpoint between typical and pre-training ASD scores. The average difference between scales is expected to be 4.4 points. We should expect a best-case gain of 4.4 points and a minimum gain of 2.2 points to consider the training worthwhile. Due to the standardization of the measures and the homogeneity of the sample, we expected an average standard deviation of the subscores of 3.1. We should also adjust the alpha value using the Bonferroni correction; therefore, with alpha’ = 0.001 and power = 0.8, the estimated sample size needed for this effect size is approximately n = 18 for each group in the best case (expected effect size d = 1.4) and n = 68 for each group in the fair scenario (expected effect size d = 0.7). Thus, our initial sample of n = 21 for each group would only have been sufficient in the best-case scenario, yet the sample was underpowered after applying the selection criteria.

For this reason, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was employed. Then, the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to evaluate differences between time T0 and time T1 separately for each of the two groups in order to assess the efficacy of the treatment. All statistical analyses were two-tailed; the statistical threshold was corrected according to Bonferroni: p < 0.05/5 = 0.01, considering the five comparisons (APL clinical sub-tests).

Finally, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to reduce the multiple dimensionalities of all the variables related to the assessment of socio-pragmatic skills. The first and second principal components were used for performing scatter plots and observing the separation of treatment in the two groups (Experimental vs. Control) before and after training.

3. Results

No significant differences in demographic, IQ values and pragmatic skills at the time of enrollment were detected between the experimental and control groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Demographic characteristics of children with ASD.

Behavioral treatments for socio-pragmatic abilities carried out better performance in both groups (Table 5). In particular, we detected significant increments for ASD children in-presence (control group) in all the parameters except for APL-C and APL-S, while for subjects undergoing online training (experimental group), significant improvements were found only for APL-M (Table 6).

Table 5.

Delta values (T1–T0) of behavioral improvements in the Experimental (Online) and Control (In-presence) groups after treatments.

Table 6.

Paired t-test analysis between T0 and T1 values in the two groups.

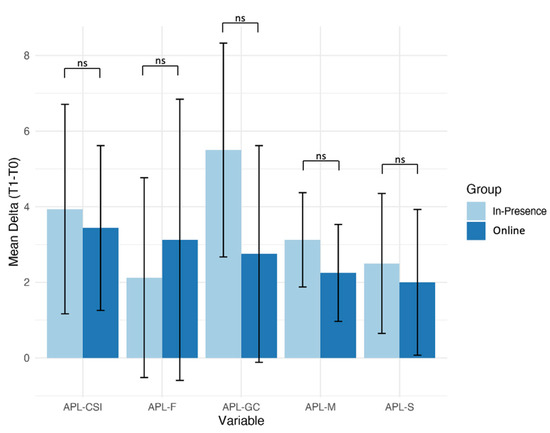

Direct comparisons between the experimental and control groups at follow-up indicated a similar improvement in pragmatic ability, without any predominant main effect of the group (Table 7). Despite no significant differences between groups being detected, it is possible to highlight a general better trend emerging in ASD children who underwent the in-presence treatment (Figure 2).

Table 7.

t-Test Analysis between Delta values (T1−T0) between groups.

Figure 2.

Mean Delta values (T1−T0) for each APL subtests in the two groups. Behavioral changes before and after treatment were calculated as the delta-values. Online training: Experimental group; In-presence: Control group. Error bars represent the SD. ns: no significant.

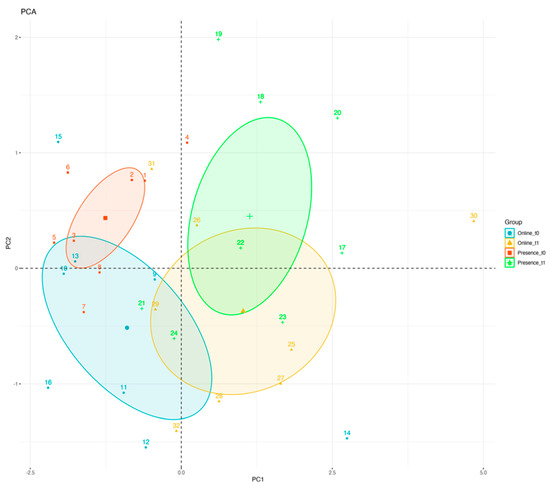

To better understand the nature of behavioral improvement stimulated by training of pragmatic abilities and how the different modalities (online vs. in-presence approach) impact ASD children, a Principal Component Analysis was performed on the data recorded at baseline versus follow-up. Results of the principal component analysis (Figure 3) demonstrated that the overall improvement in socio-pragmatic skills is higher for ASD children who underwent in-presence training. In fact, the two clusters face-to-face pre-training and face-to-face post-training are separated, while the two clusters referring to tele pre-training and tele post-training are partially overlapped.

Figure 3.

Principal Component Analysis Results. Principal component analysis of behavioral improvements in socio-pragmatic skills as detected in the Experimental group (Online training) and Control group (in-presence training).

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that our telehealth service is as efficacious as in-person usual care to improve social-pragmatic skills in children with ASD. After a 4-month behavioral treatment, the cognitive abilities detected in the experimental group were almost similar to a group of demographically and clinically matched ASD children followed in-presence. No significant differences were detected in the ability to communicate effectively, taking into account the metaphors (APL-M), the inferences on non-explicit content (CSI), the dialogic structure in a communication (C), the meaning assumed by particular expressions in social interaction (Situations) and the ability to use skills related to the “Theory of Mind” (CG).

Despite early results from univariate investigations, the main conclusion of this study is based on information from PCA. This statistical analysis shows that the area of variability linked with APL performance after treatment was farther out in the in-person group compared to the group that received remote assistance, despite a similar trend being found at follow-up between groups. In fact, the PCI study found overlap in the enhanced performance in the latter group. This result implies that face-to-face rehabilitation of pragmatic abilities is possible to have a bigger impact on the end performance relative to baseline, despite an apparent similar improvement prompted by the two alternative techniques. Instead, developing pragmatic skills through telehealth technology led to a noticeable improvement in behavior; however, the final variability found across all pragmatic sub-scales may have overlapped baseline performance.

Several studies in the literature demonstrated the efficacy and validity of online treatments for recovering behavioral skills in ASD. The majority of studies in the field of study used telemedicine to provide Parent-Training interventions [9,19,20,28], functional life skills training [29], and social skills training for parents or teachers of ASD children [16,17,18,19,30,31]. Lindgren et al. [12] conducted an RCT study to demonstrate the effectiveness of an online treatment delivered to parents of children with ASD by comparing the results to a traditional intervention (face-to-face). These authors found that there were no statistically significant differences in behavioral outcomes between the different approaches. Vismara and colleagues performed a series of telehealth training programs for parents of children with ASD. In the first preliminary study, they used live video conferencing and a self-guided website for teaching parents to implement autism-specific interventions for verbal language and joint attention initiations [21]. Significant improvements were detected in verbal skills but not in attention. In another larger RCT study, these authors found high fidelity in parents when examined 3 months later at follow-up, although children’s social communication did not improve as a result of treatment. Up to now, telehealth is currently regarded as a practical, popular, affordable, and available option for bringing together specialists working with people with ASD [29], although the magnitude of behavioral improvements resulting from remote intervention remains to be defined yet. The employment of different statistical approaches, such as PCA, could aid in increasing the interpretability and enabling the visualization of behavioral data in a new multidimensional way.

This study has two specific innovations. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first RCT study aimed at validating the application of a remote social-pragmatic skills training protocol applied directly to ASD children. Indeed, previous studies [29,30,31] demonstrated the effectiveness of telehealth intervention on social skills but mediated by parents, who were taught the principles of behavior analysis and the implementation of interventions that target functional living skills [29]. Similar to previous evidence, also in this study we confirm that the telehealth approach is effective, as an in-presence modality, to induce evident improvements in social-pragmatic skills. However, the two strategies—tele and in-person—have differing effects on the performance as a whole. Our study is, in fact, the first to use PCA analysis to more thoroughly assess behavioral performance brought on by treatment. We discovered that the in-person rehabilitation strategy is still the most effective way to cause a distinct difference between baseline and follow-up performance reports.

Limitations

The first limitation of this study was the limited number of participants. A larger sample could provide a more accurate analysis of the effects of treatment. However, the employment of demographically and clinically matched groups, as well as the employment of an RCT approach highlights the importance of our findings. Given the dearth of online behavioral treatments for recovering social skills in ASD children, this constraint is still also a strength. In fact, we feel that we have demonstrated the viability of this kind of training, and we anticipate that this will encourage a wider range of subsequent research that does not solely concentrate on one technique. Other possible limitations refer to the lack of a satisfaction questionnaire in relation to the online service, and a cost analysis to compare the cost of providing traditional face-to-face treatment in situ versus via telehealth.

5. Conclusions

In the post-pandemic era, telehealth networks have emerged as a crucial service for pursuing and upholding healthcare regulations. New remote assistance services for children with ASD are defined as an emerging topic of study that is critically needed to meet therapeutic demands. Remote health services can offer a long-term framework for carrying out assessments and educating healthcare workers and personnel on how to apply different behavioral methods. Based on the results of this study, we contend that training sessions for kids with ASD can be carried out using a straightforward remote service while retaining the effectiveness of conventional therapy. To achieve the benefit offered by a face-to-face approach, however, data from PCA analysis reveals that other strategies and tools for improving remote services need to be put into place.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.M., C.F., A.C. and G.P.; methodology, F.M., C.F., P.C., R.M. and A.C.; software, R.B., G.T. and D.V.; validation, C.F., P.C. and R.M.; formal analysis, R.B., G.T. and D.V.; investigation, F.M., C.F., N.V., I.S., G.D., P.C. and A.C.; resources, F.M., C.F., P.C., R.B., G.T., D.V., A.C. and G.P.; data curation, R.B., G.T., C.F., N.V., I.S., G.D., A.C. and R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M., C.F., A.C., R.B. and G.P.; writing—review and editing, F.M., D.V., A.C. and G.P.; visualization, F.M., D.V. and G.P.; supervision, F.M., A.C. and G.P.; project administration, G.P.; funding acquisition, G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Project INTER PARES “Inclusione, Tecnologie e Rete: un Progetto per l’Autismo fra Ricerca, E-health e Sociale”—POC Metro 2014–2020, Municipality of Messina, ME 1.3.1.b, CUP F49J18000370006, CIG 7828294093.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Research Ethics and Bioethics Committee (http://www.cnr.it/ethics, accessed on 17 December 2021) of the National Research Council of Italy (CNR) (Prot. N. CNR-AMMCEN 54444/2018 01 August2018) and by the Ethics Committee Palermo 1 (http://www.policlinico.pa.it/, accessed on 17 December 2021) of Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Policlinico Paolo Giaccone Palermo (report n. 10/2020–25 November 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ellis, T.D.; Earhart, G.M. Digital therapeutics in Parkinson’s disease: Practical applications and future potential. J. Park. Dis. 2021, 11, S95–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, M. Telehealth increases access to palliative care for people with Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9 (Suppl. 1), S75–S79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindauer, A.; Messecar, D.; McKenzie, G.; Gibson, A.; Wharton, W.; Bianchi, A.; Tarter, R.; Tadesse, R.; Boardman, C.; Golonka, O.; et al. The Tele-STELLA protocol: Telehealth-based support for families living with later-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 4254–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousaf, K.; Mehmood, Z.; Awan, I.A.; Saba, T.; Alharbey, R.; Qadah, T.; Alrige, M.A. A comprehensive study of mobile-health based assistive technology for the healthcare of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Health Care Manag. Sci. 2020, 23, 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.M.; Bernard, J. Telehealth in multiple sclerosis clinical care and research. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2021, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasadzka, E.; Trzmiel, T.; Pieczyńska, A.; Hojan, K. Modern Technologies in the Rehabilitation of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis and Their Potential Application in Times of COVID-19. Medicina 2021, 57, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbott, M.R.; Dufek, S.; Zwaigenbaum, L.; Bryson, S.; Brian, J.; Smith, I.M.; Rogers, S.J. Brief Report: Preliminary Feasibility of the TEDI: A Novel Parent-Administered Telehealth Assessment for Autism Spectrum Disorder Symptoms in the First Year of Life. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 3432–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.J.; Rozga, A.; Matthews, N.; Oberleitner, R.; Nazneen, N.; Abowd, G. Investigating the accuracy of a novel telehealth diagnostic approach for autism spectrum disorder. Psychol. Assess. 2017, 29, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, F.; Chilà, P.; Failla, C.; Minutoli, R.; Vetrano, N.; Luraschi, C.; Carrozza, C.; Leonardi, E.; Busà, M.; Genovese, S.; et al. Psychological Interventions for Children with Autism during the COVID-19 Pandemic through a Remote Behavioral Skills Training Program. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.L.; Majeski, M.J.; McEachin, J.; Leaf, R.; Cihon, J.H.; Leaf, J.B. Evaluating discrete trial teaching with instructive feedback delivered in a dyad arrangement via telehealth. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2020, 53, 1876–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, L.; MacNaul, H.; Gregori, E.; Cantrell, K. Effects of telehealth-mediated behavioral assessments and interventions on client outcomes: A quality review. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2021, 54, 484–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindgren, S.; Wacker, D.; Suess, A.; Schieltz, K.; Pelzel, K.; Kopelman, T.; Lee, J.; Romani, P.; Waldron, D. Telehealth and Autism: Treating Challenging Behavior at Lower Cost. Pediatrics 2016, 137, S167–S175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simacek, J.; Dimian, A.F.; McComas, J.J. Communication intervention for young children with severe neurodevelopmental disabilities via telehealth. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 744–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallisch, A.; Little, L.; Pope, E.; Dunn, W. Parent perspectives of an occupational therapy telehealth intervention. Int. J. Telerehabil. 2019, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, L.M.; Wallisch, A.; Pope, E.; Dunn, W. Acceptability and cost comparison of a telehealth intervention for families of children with autism. Infants Young Child. 2018, 31, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vismara, L.A.; Young, G.S.; Rogers, S.J. Telehealth for expanding the reach of early autism training to parents. Autism Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 121878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vismara, L.A.; McCormick, C.E.B.; Wagner, A.L.; Monlux, K.; Nadhan, A.; Young, G.S. Telehealth Parent Training in the Early Start Denver Model: Results from a Randomized Controlled Study. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 2016, 33, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estabillo, J.A.; Moody, C.T.; Poulhazan, S.J.; Adery, L.H.; Denluck, E.M.; Laugeson, E.A. Efficacy of PEERS® for Adolescents via Telehealth Delivery. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022, 52, 5232–5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.S.; Falkmer, M.; Chen, N.; Bölte, S.; Girdler, S. Development and feasibility of MindChip™: A social emotional telehealth intervention for autistic adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 51, 1107–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.G.; Thomas, R.P.; Brennan, L.; Helt, M.S.; Barton, M.L.; Dumont-Mathieu, T.; Fein, D.A. Development and acceptability of a new program for caregivers of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Online parent training in early behavioral intervention. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 4166–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vismara, L.A.; McCormick, C.; Young, G.S.; Nadhan, A.; Monlux, K. Preliminary findings of a telehealth approach to parent training in autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2013, 43, 2953–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bearss, K.; Burrell, T.L.; Challa, S.A.; Postorino, V.; Gillespie, S.E.; Crooks, C.; Scahill, L. Feasibility of parent training via telehealth for children with autism spectrum disorder and disruptive behavior: A demonstration pilot. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, R.; Norbury, C. Language Disorders from Infancy through Adolescence-E-Book: Listening, Speaking, Reading, Writing, and Communicating; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, L.; Cordier, R.; Munro, N.; Joosten, A.; Speyer, R. A systematic review of pragmatic language interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition (WISC-IV); CITAZIONE WISC-IV; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rosati, S.; Urbinati, N. Allenare le abilità socio-pragmatiche. In Storie Illustrate per Bambini con Disturbi dello Spettro Autistico e Altri Deficit di Comunicazione; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2016; ISBN 9788859010616. [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso, M.T. APL-Medea. In Abilità Pragmatiche del Linguaggio; Giunti OS: Firenze, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Togashi, K.; Minagawa, Y.; Hata, M.; Yamamoto, J. Evaluation of a Telehealth Parent-Training Program in Japan: Collaboration with Parents to Teach Novel Mand Skills to Children Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Behav. Anal. Pract. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, E.A.; Dounavi, K.; Ferguson, J. Telehealth to train interventionists teaching functional living skills to children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2021, 54, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.; Dounavi, K.; Craig, E.A. The impact of a telehealth platform on ABA-based parent training targeting social communication in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2022, 34, 1089–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruble, L.A.; McGrew, J.H.; Toland, M.D.; Dalrymple, N.J.; Jung, L.A. A randomized controlled trial of COMPASS web-based and face-to-face teacher coaching in autism. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).