Abstract

The emergence and popularization of dating apps have changed the way people meet and interact with potential romantic and sexual partners. In parallel with the increased use of these applications, a remarkable scientific literature has developed. However, due to the recency of the phenomenon, some gaps in the existing research can be expected. Therefore, the objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the empirical research of the psychosocial content published in the last five years (2016–2020) on dating apps. A search was conducted in different databases, and we identified 502 articles in our initial search. After screening titles and abstracts and examining articles in detail, 70 studies were included in the review. The most relevant data (author/s and year, sample size and characteristics, methodology) and their findings were extracted from each study and grouped into four blocks: user dating apps characteristics, usage characteristics, motives for use, and benefits and risks of use. The limitations of the literature consulted are discussed, as well as the practical implications of the results obtained, highlighting the relevance of dating apps, which have become a tool widely used by millions of people around the world.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, the popularization of the Internet and the use of the smartphone and the emergence of real-time location-based dating apps (e.g., Tinder, Grindr) have transformed traditional pathways of socialization and promoted new ways of meeting and relating to potential romantic and/or sexual partners [1,2,3,4].

It is difficult to know reliably how many users currently make use of dating apps, due to the secrecy of the developer companies. However, thanks to the information provided by different reports and studies, the magnitude of the phenomenon can be seen online. For example, the Statista Market Forecast [5] portal estimated that by the end of 2019, there were more than 200 million active users of dating apps worldwide. It has been noted that more than ten million people use Tinder daily, which has been downloaded more than a hundred million times worldwide [6,7]. In addition, studies conducted in different geographical and cultural contexts have shown that around 40% of single adults are looking for an online partner [8], or that around 25% of new couples met through this means [9].

Some theoretical reviews related to users and uses of dating apps have been published, although they have focused on specific groups, such as men who have sex with men (MSM [10,11]) or on certain risks, such as aggression and abuse through apps [12].

Anzani et al. [1] conducted a review of the literature on the use of apps to find a sexual partner, in which they focused on users’ sociodemographic characteristics, usage patterns, and the transition from online to offline contact. However, this is not a systematic review of the results of studies published up to that point and it leaves out some relevant aspects that have received considerable research attention, such as the reasons for use of dating apps, or their associated advantages and risks.

Thus, we find a recent and changing object of study, which has achieved great social relevance in recent years and whose impact on research has not been adequately studied and evaluated so far. Therefore, the objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the empirical research of psychosocial content published in the last five years (2016–2020) on dating apps. By doing so, we intend to assess the state of the literature in terms of several relevant aspects (i.e., users’ profile, uses and motives for use, advantages, and associated risks), pointing out some limitations and posing possible future lines of research. Practical implications will be highlighted.

2. Materials and Methods

The systematic literature review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13,14], and following the recommendations of Gough et al. [15]. However, it should be noted that, as the objective of this study was to provide a state of the art view of the published literature on dating apps in the last five years and without statistical data processing, there are several principles included in the PRISMA that could not be met (e.g., summary measures, planned methods of analysis, additional analysis, risk of bias within studies). However, following the advice of the developers of these guidelines concerning the specific nature of systematic reviews, the procedure followed has been described in a clear, precise, and replicable manner [13].

2.1. Literature Search and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We examined the databases of the Web of Science, Scopus, and Medline, as well as PsycInfo and Psycarticle and Google Scholar, between 1 March and 6 April 2020. In all the databases consulted, we limited the search to documents from the last five years (2016–2020) and used general search terms, such as “dating apps” and “online dating” (linking the latter with “apps”), in addition to the names of some of the most popular and frequently used dating apps worldwide, such as “tinder”, “grindr”, and “momo”, to identify articles that met the inclusion criteria (see below).

The selection criteria in this systematic review were established and agreed on by the two authors of this study. The database search was carried out by one researcher. In case of doubt about whether or not a study should be included in the review, consultation occurred and the decision was agreed upon by the two researchers.

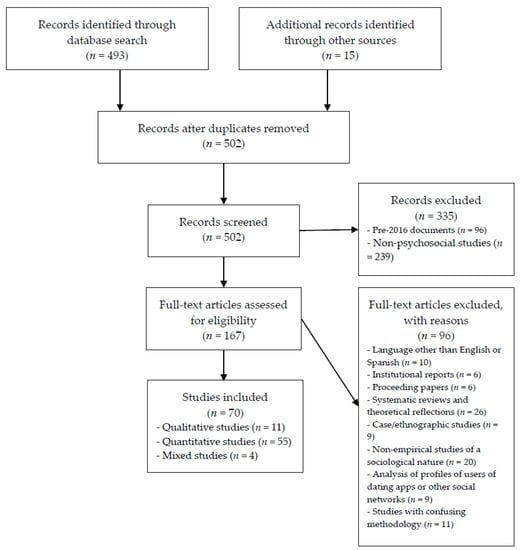

Four-hundred and ninety-three results were located, to which were added 15 documents that were found through other resources (e.g., social networks, e-mail alerts, newspapers, the web). After these documents were reviewed and the duplicates removed, a total of 502 records remained, as shown by the flowchart presented in Figure 1. At that time, the following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) empirical, quantitative or qualitative articles; (2) published on paper or in electronic format (including “online first”) between 2016 and 2020 (we decided to include articles published since 2016 after finding that the previous empirical literature in databases on dating apps from a psychosocial point of view was not very large; in fact, the earliest studies of Tinder included in Scopus dated back to 2016; (3) to be written in English or Spanish; and (4) with psychosocial content. No theoretical reviews, case studies/ethnography, user profile content analyses, institutional reports, conference presentations, proceeding papers, etc., were taken into account.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the systematic review process.

Thus, the process of refining the results, which can be viewed graphically in Figure 1, was as follows. Of the initial 502 results, the following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) pre-2016 documents (96 records excluded); (2) documents that either did not refer to dating apps or did so from a technological approach (identified through title and abstract; 239 records excluded); (3) published in a language other than English or Spanish (10 records excluded); (4) institutional reports, or analysis of the results of such reports (six records excluded); (5) proceeding papers (six records excluded); (6) systematic reviews and theoretical reflections (26 records excluded); (7) case studies/ethnography (nine records excluded); (8) non-empirical studies of a sociological nature (20 records excluded); (9) analysis of user profile content and campaigns on dating apps and other social networks (e.g., Instagram; nine records excluded); and (10) studies with confusing methodology, which did not explain the methodology followed, the instruments used, and/or the characteristics of the participants (11 records excluded). This process led to a final sample of 70 empirical studies (55 quantitative studies, 11 qualitative studies, and 4 mixed studies), as shown by the flowchart presented in Figure 1.

2.2. Data Collection Process and Data Items

One review author extracted the data from the included studies, and the second author checked the extracted data. Information was extracted from each included study of: (1) author/s and year; (2) sample size and characteristics; (3) methodology used; (4) main findings.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the information extracted from each of the articles included in this systematic review. The main findings drawn from these studies are also presented below, distributed in different sections.

Table 1.

Characteristics of reviewed studies.

3.1. Characteristics of Reviewed Studies

First, the characteristics of the 70 articles included in the systematic review were analyzed. An annual increase in production can be seen, with 2019 being the most productive year, with 31.4% (n = 22) of included articles. More articles (11) were published in the first three months of 2020 than in 2016. It is curious to note, on the other hand, how, in the titles of the articles, some similar formulas were repeated, even the same articles (e.g., Love me Tinder), playing with the swipe characteristic of this type of application (e.g., Swiping more, Swiping right, Swiping me).

As for the methodology used, the first aspect to note is that all the localized studies were cross-sectional and there were no longitudinal ones. As mentioned above, 80% (n = 55) of the studies were quantitative, especially through online survey (n = 49; 70%). 15.7% (n = 11) used a qualitative methodology, either through semi-structured interviews or focus groups. And 5.7% (n = 4) used a mixed methodology, both through surveys and interviews. It is worth noting the increasing use of tools such as Amazon Mechanical Turk (n = 9, 12.9%) or Qualtrics (n = 8, 11.4%) for the selection of participants and data collection.

The studies included in the review were conducted in different geographical and cultural contexts. More than one in five investigations was conducted in the United States (22.8%, n = 16), to which the two studies carried out in Canada can be added. Concerning other contexts, 20% (n = 14) of the included studies was carried out in different European countries (e.g., Belgium, The Netherlands, UK, Spain), whereas 15.7% (n = 11) was carried out in China, and 8.6% (n = 6) in other countries (e.g., Thailand, Australia). However, 21.4% (n = 15) of the investigations did not specify the context they were studying.

Finally, 57.1% (n = 40) of the studies included in the systematic review asked about dating apps use, without specifying which one. The results of these studies showed that Tinder was the most used dating app among heterosexual people and Grindr among sexual minorities. Furthermore, 35% (n = 25) of the studies included in the review focused on the use of Tinder, while 5.7% (n = 4) focused on Grindr.

3.2. Characteristics of Dating App Users

It is difficult to find studies that offer an overall user profile of dating apps, as many of them have focused on specific populations or groups. However, based on the information collected in the studies included in this review, some features of the users of these applications may be highlighted.

Gender. Traditionally, it has been claimed that men use dating apps more than women and that they engage in more casual sex relationships through apps [3]. In fact, some authors, such as Weiser et al. [75], collected data that indicated that 60% of the users of these applications were male and 40% were female. Some current studies endorse that being male predicts the use of dating apps [23], but research has also been published in recent years that has shown no differences in the proportion of male and female users [59,68].

To explain these similar prevalence rates, some authors, such as Chan [27], have proposed a feminist perspective, stating that women use dating apps to gain greater control over their relationships and sexuality, thus countering structural gender inequality. On the other hand, other authors have referred to the perpetuation of traditional masculinity and femmephobic language in these applications [28,53].

Age. Specific studies have been conducted on people of different ages: adolescents [49], young people (e.g., [21,23,71]), and middle-aged and older people [58]. The most studied group has been young people between 18 and 30 years old, mainly university students, and some authors have concluded that the age subgroup with a higher prevalence of use of dating apps is between 24 and 30 years of age [44,59].

Sexual orientation. This is a fundamental variable in research on dating apps. In recent years, especially after the success of Tinder, the use of these applications by heterosexuals, both men and women, has increased, which has affected the increase of research on this group [3,59]. However, the most studied group with the highest prevalence rates of dating apps use is that of men from sexual minorities [18,40]. There is considerable literature on this collective, both among adolescents [49], young people [18], and older people [58], in different geographical contexts and both in urban and rural areas [24,36,43,79]. Moreover, being a member of a sexual minority, especially among men, seems to be a good predictor of the use of dating apps [23].

For these people, being able to communicate online can be particularly valuable, especially for those who may have trouble expressing their sexual orientation and/or finding a partner [3,80]. There is much less research on non-heterosexual women and this focuses precisely on their need to reaffirm their own identity and discourse, against the traditional values of hetero-patriate societies [35,69].

Relationship status. It has traditionally been argued that the prevalence of the use of dating apps was much higher among singles than among those with a partner [72]. This remains the case, as some studies have shown that being single was the most powerful sociodemographic predictor of using these applications [23]. However, several investigations have concluded that there is a remarkable percentage of users, between 10 and 29%, who have a partner [4,17,72]. From what has been studied, usually aimed at evaluating infidelity [17,75], the reasons for using Tinder are very different depending on the relational state, and the users of this app who had a partner had had more sexual and romantic partners than the singles who used it [72].

Other sociodemographic variables. Some studies, such as the one of Shapiro et al. [64], have found a direct relationship between the level of education and the use of dating apps. However, most studies that contemplated this variable have focused on university students (see, for example [21,23,31,38]), so there may be a bias in the interpretation of their results. The findings of Shapiro et al. [64] presented a paradox: while they found a direct link between Tinder use and educational level, they also found that those who did not use any app achieved better grades. Another striking result about the educational level is that of the study of Neyt et al. [9] about their users’ characteristics and those that are sought in potential partners through the apps. These authors found a heterogeneous effect of educational level by gender: whereas women preferred a potential male partner with a high educational level, this hypothesis was not refuted in men, who preferred female partners with lower educational levels.

Other variables evaluated in the literature on dating apps are place of residence or income level. As for the former, app users tend to live in urban contexts, so studies are usually performed in large cities (e.g., [11,28,45]), although it is true that in recent years studies are beginning to be seen in rural contexts to know the reality of the people who live there [43]. It has also been shown that dating app users have a higher income level than non-users, although this can be understood as a feature associated with young people with high educational levels. However, it seems that the use of these applications is present in all social layers, as it has been documented even among homeless youth in the United States [66].

Personality and other psychosocial variables. The literature that relates the use of dating apps to different psychosocial variables is increasingly extensive and diverse. The most evaluated variable concerning the use of these applications is self-esteem, although the results are inconclusive. It seems established that self-esteem is the most important psychological predictor of using dating apps [6,8,59]. But some authors, such as Orosz et al. [55], warn that the meaning of that relationship is unclear: apps can function both as a resource for and a booster of self-esteem (e.g., having a lot of matches) or to decrease it (e.g., lack of matches, ignorance of usage patterns).

The relationship between dating app use and attachment has also been studied. Chin et al. [29] concluded that people with a more anxious attachment orientation and those with a less avoidant orientation were more likely to use these apps.

Sociosexuality is another important variable concerning the use of dating apps. It has been found that users of these applications tended to have a less restrictive sociosexuality, especially those who used them to have casual sex [6,7,8,21].

Finally, the most studied approach in this field is the one that relates the use of dating apps with certain personality traits, both from the Big Five and from the dark personality model. As for the Big Five model, Castro et al. [23] found that the only trait that allowed the prediction of the current use of these applications was open-mindedness. Other studies looked at the use of apps, these personality traits, and relational status. Thus, Timmermans and De Caluwé [71] found that single users of Tinder were more outgoing and open to new experiences than non-user singles, who scored higher in conscientiousness. For their part, Timmermans et al. [72] concluded that Tinder users who had a partner scored lower in agreeableness and conscientiousness and higher in neuroticism than people with partners who did not use Tinder.

The dark personality, on the other hand, has been used to predict the different reasons for using dating apps [48], as well as certain antisocial behaviors in Tinder [6,51]. As for the differences in dark personality traits between users and non-users of dating apps, the results are inconclusive. A study was localized that highlighted the relevance of psychopathy [3] whereas another study found no predictive power as a global indicator of dark personality [23].

3.3. Characteristics of Dating App Use

It is very difficult to know not only the actual number of users of dating apps in any country in the world but also the prevalence of use. This varies depending on the collectives studied and the sampling techniques used. Given this caveat, the results of some studies do allow an idea of the proportion of people using these apps. It has been found to vary between the 12.7% found by Castro et al. [23] and the 60% found by LeFebvre [44]. Most common, however, is to find a participant prevalence of between 40–50% [3,4,39,62,64], being slightly higher among men from sexual minorities [18,50].

The study of Botnen et al. [21] among Norwegian university students concluded that about half of the participants appeared to be a user of dating apps, past or present. But only one-fifth were current users, a result similar to those found by Castro et al. [23] among Spanish university students. The most widely used, and therefore the most examined, apps in the studies are Tinder and Grindr. The first is the most popular among heterosexuals, and the second among men of sexual minorities [3,18,36,70].

Findings from existing research on the characteristics of the use of dating apps can be divided among those referring to before (e.g., profiling), during (e.g., use), and after (e.g., offline behavior with other app users). Regarding before, the studies focus on users’ profile-building and self-presentation more among men of sexual minorities [52,77]. Ward [74] highlighted the importance of the process of choosing the profile picture in applications that are based on physical appearance. Like Ranzini and Lutz [59], Ward [74] mentions the differences between the “real self” and the “ideal self” created in dating apps, where one should try to maintain a balance between one and the other. Self-esteem plays a fundamental role in this process, as it has been shown that higher self-esteem encourages real self-presentation [59].

Most of the studies that analyze the use of dating apps focus on during, i.e. on how applications are used. As for the frequency of use and the connection time, Chin et al. [29] found that Tinder users opened the app up to 11 times a day, investing up to 90 minutes per day. Strubel and Petrie [67] found that 23% of Tinder users opened the app two to three times a day, and 14% did so once a day. Meanwhile, Sumter and Vandenbosch [3] concluded that 23% of the users opened Tinder daily.

It seems that the frequency and intensity of use, in addition to the way users behave on dating apps, vary depending on sexual orientation and sex. Members of sexual minorities, especially men, use these applications more times per day and for longer times [18]. As for sex, different patterns of behavior have been observed both in men and women, as the study of Timmermans and Courtois [4] shows. Men use apps more often and more intensely, but women use them more selectively and effectively. They accumulate more matches than men and do so much faster, allowing them to choose and have a greater sense of control. Therefore, it is concluded that the number of swipes and likes of app users does not guarantee a high number of matches in Tinder [4].

Some authors are alert to various behaviors observed in dating apps which, in some cases, may be negative for the user. For example, Yeo and Fung [77] mention the fast and hasty way of acting in apps, which is incongruous with cultural norms for the formation of friendships and committed relationships and ends up frustrating those who seek more lasting relationships. Parisi and Comunello [57] highlighted a key to the use of apps and a paradox. They referred to relational homophilia, that is, the tendency to be attracted to people similar to oneself. But, at the same time, this occurs in a context that increases the diversity of intimate interactions, thus expanding pre-existing networks. Finally, Licoppe [45] concluded that users of Grindr and Tinder present almost opposite types of communication and interaction. In Grindr, quick conversations seem to take precedence, aimed at organizing immediate sexual encounters, whereas, in Tinder, there are longer conversations and more exchange of information.

The latest group of studies focuses on offline behavior with contacts made through dating apps. Differences have been observed in the prevalence of encounters with other app users, possibly related to participants’ sociodemographic characteristics. Whereas Strugo and Muise [2], and Macapagal et al. [49] found that between 60 and 70% of their participants had had an encounter with another person known through these applications, in other studies this is less common, with prevalence being less than 50% [3,4,62]. In fact, Griffin et al. [39] stated that in-person encounters were relatively rare among users of dating apps.

There are also differences in the types of relationships that arose after offline encounters with other users. Strugo and Muise [2] concluded that 33% of participants had found a romantic partner and that 52% had had casual sex with at least one partner met through an app. Timmermans and Courtois [4] found that one-third of the offline encounters ended in casual sex and one-fourth in a committed relationship. Sumter and Vandenbosch [3], for their part, concluded that 18.6% of the participants had had sex with another person they had met on Tinder. And finally, the participants in the study of Timmermans and De Caluwé [71] indicated that: (1) they had met face-to-face with an average of 4.25 people whom they had met on Tinder; (2) they had had one romantic relationship with people met on Tinder; (3) they had had casual sex with an average of 1.57 people met on Tinder; and (4) they had become friends with an average of 2.19 people met on Tinder.

3.4. Motives for Dating App Use

There is a stereotype that dating apps are used only, or above all, to look for casual sex [44]. In fact, these applications have been accused of generating a hookup culture, associated with superficiality and sexual frivolity [2]. However, this is not the case. In the last five years, a large body of literature has been generated on the reasons why people use dating apps, especially Tinder, and the conclusion is unanimous: apps serve multiple purposes, among which casual sex is only one [1,4,44]. It has been found that up to 70% of the app users participating in a study [18] indicated that their goal when using it was not sex-seeking.

An evolution of research interest can be traced regarding the reasons that guide people to use dating apps [55]. The first classification of reasons for using Tinder was published by Ranzini and Lutz [59], who adapted a previous scale, designed for Grindr, composed of six motives: hooking up/sex (finding sexual partners), friendship (building a social network), relationship (finding a romantic partner), traveling (having dates in different places), self-validation (self-improvement), and entertainment (satisfying social curiosity). They found that the reason given by most users was those of entertainment, followed by those of self-validation and traveling, with the search for sex occupying fourth place in importance. However, the adaptation of this scale did not have adequate psychometric properties and it has not been reused.

Subsequently, Sumter et al. [68] generated a new classification of reasons to use Tinder, later refined by Sumter and Vandenbosch [3]. They proposed six reasons for use, both relational (love, casual sex), intrapersonal (ease of communication, self-worth validation), and entertainment (the thrill of excitement, trendiness). The motivation most indicated by the participants was that of love, and the authors concluded that Tinder is used: (1) to find love and/or sex; (2) because it is easy to communicate; (3) to feel better about oneself; and (4) because it’s fun and exciting.

At the same time, Timmermans and De Caluwé [70] developed the Tinder Motives Scale, which evaluates up to 13 reasons for using Tinder. The reasons, sorted by the scores obtained, were: to pass time/entertainment, curiosity, socializing, relationship-seeking, social approval, distraction, flirting/social skills, sexual orientation, peer pressure, traveling, sexual experience, ex, and belongingness. So far, the most recently published classification of reasons is that of Orosz et al. [55], who in the Tinder Use Motivations Scale proposed four groups of reasons: boredom (individual reasons to use Tinder to overcome boredom), self-esteem (use of Tinder to improve self-esteem), sex (use of Tinder to satisfy sexual need) and love (use of Tinder to find love). As in the previous scales, the reasons of seeking sex did not score higher on this scale, so it can be concluded that dating apps are not mainly used for this reason.

The existing literature indicates that reasons for the use of dating apps may vary depending on different sociodemographic and personality variables [1]. As for sex, Ranzini and Lutz [59] found that women used Tinder more for friendship and self-validation, whereas men used it more to seek sex and relationships. Sumter et al. [68] found something similar: men scored higher than women in casual sex motivation and also in the motives of ease of communication and thrill of excitement.

With regard to age, Ward [74] concluded that motivations change over time and Sumter et al. [68] found a direct association with the motives of love, casual sex, and ease of communication. In terms of sexual orientation, it has become commoner for people from sexual minorities, especially men, than for heterosexual participants to use these applications much more in the search for casual sex [18].

Finally, other studies have concluded that personality guides the motivations for the use of dating apps [3,72]. A line of research initiated in recent years links dark personality traits to the reasons for using Tinder. In this investigation, Lyons et al. [48] found that people who score high in Machiavellianism and psychopathy offer more reasons for use (e.g., get casual sex, acquiring social or flirting skills).

3.5. Benefits and Risks of Using Dating Apps

In the latter section, the benefits and advantages of the use of dating apps are analyzed. There is also an extensive literature on the risks associated with use. Many studies indicate that dating apps have opened a new horizon in how to meet potential partners, allowing access to many [3,6,8], which may be even more positive for certain individuals and groups who have been silenced or marginalized, such as some men from sexual minorities [80]. It has also been emphasized that these applications are a non-intimidating way to start connecting, they are flexible and free, and require less time and effort than other traditional means of communication [1,55].

On the other hand, the advantages of apps based on the technology they use and the possibilities they pose to users have been highlighted. Ranzini and Lutz [59] underlined four aspects. First is the portability of smartphones and tablets, which allows the use of apps in any location, both private and public. Second is availability, as their operation increases the spontaneity and frequency of use of the apps, and this, in turn, allows a quick face-to-face encounter, turning online interactions into offline relationships [70,77]. Thirdly is locatability, as dating apps allow matches, messages, and encounters with other users who are geographically close [77]. Finally is multimediality, the relevance of the visual, closely related to physical appearance, which results in two channels of communication (photos and messages) and the possibility of linking the profile with that of other social networks, such as Facebook and Instagram [4].

There is also considerable literature focused on the potential risks associated with using these applications. The topics covered in the studies can be grouped into four blocks, having in common the negative consequences that these apps can generate in users’ mental, relational, and sexual health. The first block focuses on the configuration and use of the applications themselves. Their emergence and popularization have been so rapid that apps pose risks associated with security, intimacy, and privacy [16,20]. This can lead to more insecure contacts, especially among women, and fears related to the ease of localization and the inclusion of personal data in apps [39]. Some authors highlight the paradox that many users suffer: they have more chances of contact than ever before, but at the same time this makes them more vulnerable [26,80].

This block can also include studies on the problematic use of apps, which can affect the daily lives of users [34,56], and research that focuses on the possible negative psychological effects of their use, as a link has been shown between using dating apps and loneliness, dissatisfaction with life, and feeling excluded from the world [24,34,78].

The second block of studies on the risks associated with dating apps refers to discrimination and aggression. Some authors, such as Conner [81] and Lauckner et al. [43], have argued that technology, instead of reducing certain abusive cultural practices associated with deception, discrimination, or abuse (e.g., about body types, weight, age, rural environments, racism, HIV stigma), has accentuated them, and this can affect users’ mental health. Moreover, certain antisocial behaviors in apps, such as trolling [6,51], have been studied, and a relationship has been found between being a user of these applications and suffering some episode of sexual victimization, both in childhood and adulthood [30].

The following block refers to the risks of dating app use regarding diet and body image. These applications, focusing on appearance and physical attractiveness, can promote excessive concerns about body image, as well as various negative consequences associated with it (e.g., unhealthy weight management behaviors, low satisfaction and high shame about the body, more comparisons with appearance [22,36,67,73]). These risks have been more closely associated with men than with women [61], perhaps because of the standards of physical attractiveness prevalent among men of sexual minorities, which have been the most studied collective.

The last block of studies on the risks of dating app use focuses on their relationship with risky sexual behaviors. This is probably the most studied topic in different populations (e.g., sexual minority men, heterosexual people). The use of these applications can contribute to a greater performance of risky sexual behaviors, which results in a higher prevalence of sexually transmitted illnesses (STIs). However, the results of the studies analyzed are inconclusive [40].

On the one hand, some studies find a relationship between being a user of dating apps and performing more risky sexual behaviors (e.g., having more sexual partners, less condom use, more relationships under the effects of alcohol and other drugs), both among men from sexual minorities [19] and among heterosexual individuals [32,41,62]. On the other hand, some research has found that, although app users perform more risky behaviors, especially having more partners, they also engage in more prevention behaviors (e.g., more sex counseling, more HIV tests, more treatment) and they do not use the condoms less than non-users [18,50,64,79]. Studies such as that of Luo et al. [46] and that of Wu [76] also found greater use of condoms among app users than among non-users.

Finally, some studies make relevant appraisals of this topic. For example, Green et al. [38] concluded that risky sexual behaviors are more likely to be performed when sex is performed with a person met through a dating app with whom some common connection was made (e.g., shared friends in Facebook or Instagram). This is because these users tend to avoid discussing issues related to prevention, either because they treat that person more familiarly, or for fear of possible gossip. Finally, Hahn et al. [40] found that, among men from sexual minorities, the contact time prior to meeting in person was associated with greater prevention. The less time between the conversation and the first encounter, the more likely the performance of risky behaviors.

4. Discussion

In a very few years, dating apps have revolutionized the way of meeting and interacting with potential partners. In parallel with the popularization of these applications, a large body of knowledge has been generated which, however, has not been collected in any systematic review. Given the social relevance that this phenomenon has reached, we performed this study to gather and analyze the main findings of empirical research on psychosocial content published in the last five years (2016–2020) on dating apps.

Seventy studies were located and analyzed, after applying stringent inclusion criteria that, for various reasons, left out a large number of investigations. Thus, it has been found that the literature on the subject is extensive and varied. Studies of different types and methodologies have been published, in very diverse contexts, on very varied populations and focusing on different aspects, some general and others very specific. Therefore, the first and main conclusion of this study is that the phenomenon of dating apps is transversal, and very present in the daily lives of millions of people around the world.

This transversality has been evident in the analysis of the characteristics of the users of dating apps. Apps have been found to be used, regardless of sex [59,68], age [49,58,71], sexual orientation [3,59], relational status [72], educational and income level [9,66], or personality traits [23,48,72].

Another conclusion that can be drawn from this analysis is that there are many preconceived ideas and stereotypes about dating apps, both at the research and social level, which are supported by the literature, but with nuances. For example, although the stereotype says that apps are mostly used by men, studies have concluded that women use them in a similar proportion, and more effectively [4]. The same goes for sexual orientation or relational status; the stereotype says that dating apps are mostly used by men of sexual minorities and singles [1], but some apps (e.g., Tinder) are used more by heterosexual people [3,59] and there is a remarkable proportion of people with a partner who use these apps [4,17].

A third conclusion of the review of the studies is that to know and be able to foresee the possible consequences of the use of dating apps, how and why they are used are particularly relevant. For this reason, both the use and the motives for use of these applications have been analyzed, confirming the enormous relevance of different psychosocial processes and variables (e.g., self-esteem, communication, and interaction processes), both before (profiling), during (use), and after (off-line encounters) of the use of dating apps.

However, in this section, what stands out most is the difficulty in estimating the prevalence of the use of dating apps. Very disparate prevalence have been found not only because of the possible differences between places and groups (see, for example [18,23,44,64]), but also because of the use of different sampling and information collection procedures, which in some cases, over-represent app users. All this hinders the characterization and assessment of the phenomenon of dating apps, as well as the work of the researchers. After selecting the group to be studied, it would be more appropriate to collect information from a representative sample, without conditioning or directing the study toward users, as this may inflate the prevalence rates.

The study of motives for the use of dating apps may contain the strongest findings of all those appraised in this review. Here, once again, a preconceived idea has been refuted, not only among researchers but across society. Since their appearance, there is a stereotype that dating apps are mostly used for casual sex [2,44]. However, studies constantly and consistently show that this is not the case. The classifications of the reasons analyzed for their use have concluded that people use dating apps for a variety of reasons, such as to entertain themselves, out of curiosity, to socialize, and to seek relationships, both sexual and romantic [3,59,68,70]. Thus, these apps should not be seen as merely for casual sex, but as much more [68].

Understanding the reasons for using dating apps provides a necessary starting point for research questions regarding the positive and negative effects of use [70]. Thus, the former result block reflected findings on the advantages and risks associated with using dating apps. In this topic, there may be a paradox in the sense that something that is an advantage (e.g., access to a multitude of potential partners, facilitates meeting people) turns into a drawback (e.g., loss of intimacy and privacy). Research on the benefits of using dating apps is relatively scarce, but it has stressed that these tools are making life and relationships easier for many people worldwide [6,80].

The literature on the risks associated with using dating apps is much broader, perhaps explaining the negative social vision of them that still exists nowadays. These risks have highlighted body image, aggression, and the performance of risky sexual behaviors. Apps represent a contemporary environment that, based on appearance and physical attractiveness, is associated with several negative pressures and perceptions about the body, which can have detrimental consequences for the physical and mental health of the individual [67]. As for assaults, there is a growing literature alerting us to the increasing amount of sexual harassment and abuse related to dating apps, especially in more vulnerable groups, such as women, or among people of sexual minorities (e.g., [12,82]).

Finally, there is considerable research that has analyzed the relationship between the use of dating apps and risky sexual behaviors, in different groups and with inconclusive results, as has already been shown [40,46,76]. In any case, as dating apps favor contact and interaction between potential partners, and given that a remarkable percentage of sexual contacts are unprotected [10,83], further research should be carried out on this topic.

Limitations and Future Directions

The meteoric appearance and popularization of dating apps have generated high interest in researchers around the world in knowing how they work, the profile of users, and the psychosocial processes involved. However, due to the recency of the phenomenon, there are many gaps in the current literature on these applications. That is why, in general terms, more research is needed to improve the understanding of all the elements involved in the functioning of dating apps.

It is strange to note that many studies have been conducted focusing on very specific aspects related to apps while other central aspects, such as the profile of users, had not yet been consolidated. Thus, it is advisable to improve the understanding of the sociodemographic and personality characteristics of those who use dating apps, to assess possible differences with those who do not use them. Attention should also be paid to certain groups that have been poorly studied (e.g., women from sexual minorities), as research has routinely focused on men and heterosexual people.

Similarly, limitations in understanding the actual data of prevalence of use have been highlighted, due to the over-representation of the number of users of dating apps seen in some studies. Therefore, it would be appropriate to perform studies in which the app user would not be prioritized, to know the actual use of these tools among the population at large. Although further studies must continue to be carried out on the risks of using these applications (e.g., risky sexual behaviors), it is also important to highlight the positive sexual and relational consequences of their use, in order to try to mitigate the negative social vision that still exists about dating app users. Last but not least, as all the studies consulted and included in this systematic review were cross-sectional, longitudinal studies are necessary which can evaluate the evolution of dating apps, their users and their uses, motives, and consequences.

The main limitations of this systematic review concern the enormous amount of information currently existing on dating apps. Despite having applied rigorous exclusion criteria, limiting the studies to the 2016–2020 period, and that the final sample was of 70 studies, much information has been analyzed and a significant number of studies and findings that may be relevant were left out. In future, the theoretical reviews that are made will have to be more specific, focused on certain groups and/or problems.

Another limitation—in this case, methodological, to do with the characteristics of the topic analyzed and the studies included—is that not all the criteria of the PRISMA guidelines were followed [13,14]. We intended to make known the state of the art in a subject well-studied in recent years, and to gather the existing literature without statistical treatment of the data. Therefore, there are certain criteria of PRISMA (e.g., summary measures, planned methods of analysis, additional analysis, risk of bias within studies) that cannot be satisfied.

However, as stated in the Method section, the developers of the PRISMA guidelines themselves have stated that some systematic reviews are of a different nature and that not all of them can meet these criteria. Thus, their main recommendation, to present methods with adequate clarity and transparency to enable readers to critically judge the available evidence and replicate or update the research, has been followed [13].

Finally, as the initial search in the different databases was carried by only one of the authors, some bias could have been introduced. However, as previously noted, with any doubt about the inclusion of any study, the final decision was agreed between both authors, so we expect this possible bias to be small.

5. Conclusions

Dating apps have come to stay and constitute an unstoppable social phenomenon, as evidenced by the usage and published literature on the subject over the past five years. These apps have become a new way to meet and interact with potential partners, changing the rules of the game and romantic and sexual relationships for millions of people all over the world. Thus, it is important to understand them and integrate them into the relational and sexual life of users [76].

The findings of this systematic review have relevant implications for various groups (i.e., researchers, clinicians, health prevention professionals, users). Detailed information has been provided on the characteristics of users and the use of dating apps, the most common reasons for using them, and the benefits and risks associated with them. This can guide researchers to see what has been done and how it has been done and to design future research.

Second, there are implications for clinicians and health prevention and health professionals, concerning mental, relational, and sexual health. These individuals will have a starting point for designing more effective information and educational programs. These programs could harness the potential of the apps themselves and be integrated into them, as suggested by some authors [42,84].

Finally and unavoidably, knowledge about the phenomenon of dating apps collected in this systematic review can have positive implications for users, who may have at their disposal the necessary tools to make a healthy and responsible use of these applications, maximizing their advantages and reducing the risks posed by this new form of communication present in the daily life of so many people.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Á.C. and J.R.B.; methodology, Á.C. and J.R.B.; formal analysis, Á.C. and J.R.B.; investigation, Á.C. and J.R.B.; resources, Á.C. and J.R.B.; data curation, Á.C. and J.R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Á.C.; writing—review and editing, J.R.B. and Á.C.; project administration, Á.C.; funding acquisition, Á.C. and J.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by: (1) Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, Government of Spain (PGC2018-097086-A-I00); and (2) Government of Aragón (Group S31_20D). Department of Innovation, Research and University and FEDER 2014-2020, “Building Europe from Aragón”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Anzani, A.; Di Sarno, M.; Prunas, A. Using smartphone apps to find sexual partners: A review of the literature. Sexologies 2018, 27, e61–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strugo, J.; Muise, A. Swiping for the right reasons: Approach and avoidance goals are associated with actual and perceived dating success on Tinder. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2019, 28, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumter, S.R.; Vandenbosch, L. Dating gone mobile: Demographic and personality-based correlates of using smartphone-based dating applications among emerging adults. New Media Soc. 2019, 21, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, E.; Courtois, C. From swiping to casual sex and/or committed relationships: Exploring the experiences of Tinder users. Inf. Soc. 2018, 34, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Market Forecast. eServices Report 2019—Dating Services. Available online: https://www.statista.com/study/40456/dating-services-report/ (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Duncan, Z.; March, E. Using Tinder® to start a fire: Predicting antisocial use of Tinder® with gender and the Dark Tetrad. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 145, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevi, B.; Aral, T.; Eskenazi, T. Exploring the hook-up app: Low sexual disgust and high sociosexuality predict motivation to use Tinder for casual sex. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 133, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatter, K.; Hodkinson, K. On the differences between Tinder versus online dating agencies: Questioning a myth. An exploratory study. Cogent Psychol. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyt, B.; Vandenbulcke, S.; Baert, S. Are men intimidated by highly educated women? Undercover on Tinder. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2019, 73, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, G. The use of geosocial networking smartphone applications and the risk of sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ward, J. The mediation of gay men’s lives: A review on gay dating app studies. Sociol. Compass 2018, 12, e12560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillett, R. Intimate intrusions online: Studying the normalisation of abuse in dating apps. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2018, 69, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gough, D.; Oliver, S.; Thomas, J. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews; SAGE: New Park, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Albury, K.; Byron, P. Safe on my phone? Same-sex attracted young people’s negotiations of intimacy, visibility, and risk on digital hook-up apps. Soc. Media Soc. 2016, 2, 205630511667288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexopoulos, C.; Timmermans, E.; McNallie, J. Swiping more, committing less: Unraveling the links among dating app use, dating app success, and intention to commit infidelity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 102, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badal, H.J.; Stryker, J.E.; DeLuca, N.; Purcell, D.W. Swipe Right: Dating Website and App Use Among Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2018, 22, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonchutima, S.; Kongchan, W. Utilization of dating apps by men who have sex with men for persuading other men toward substance use. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2017, 10, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith Boonchutima; Sopon Sriwattana; Rungroj Rungvimolsin; Nattanop Palahan Gays dating applications: Information disclosure and sexual behavior. J. Health Res. 2016, 30, 231–239. [CrossRef]

- Botnen, E.O.; Bendixen, M.; Grøntvedt, T.V.; Kennair, L.E.O. Individual differences in sociosexuality predict picture-based mobile dating app use. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 131, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, A.S.; Sandil, R.; Brewster, M.E.; Parent, M.C.; Chan, A.; Yucel, A.; Bensmiller, N.; Glaeser, E. Adonis on the apps: Online objectification, self-esteem, and sexual minority men. Psychol. Men Masc. 2020, 21, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, Á.; Barrada, J.R.; Ramos-Villagrasa, P.J.; Fernández-del-Río, E. Profiling Dating Apps Users: Sociodemographic and Personality Characteristics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, L.S. The role of gay identity confusion and outness in sex-seeking on mobile dating apps among men who have sex with men: A conditional process analysis. J. Homosex. 2017, 64, 622–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, L.S. Who uses dating apps? Exploring the relationships among trust, sensation-seeking, smartphone use, and the intent to use dating apps based on the Integrative Model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.S. Ambivalence in networked intimacy: Observations from gay men using mobile dating apps. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 2566–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.S. Liberating or disciplining? A technofeminist analysis of the use of dating apps among women in urban China. Commun. Cult. Crit. 2018, 11, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.S. Paradoxical associations of masculine ideology and casual sex among heterosexual male geosocial networking app users in China. Sex Roles 2019, 81, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.; Edelstein, R.S.; Vernon, P.A. Attached to dating apps: Attachment orientations and preferences for dating apps. Mob. Media Commun. 2019, 7, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.P.H.; Wong, J.Y.H.; Fong, D.Y.T. An emerging risk factor of sexual abuse: The use of smartphone dating applications. Sex. Abuse J. Res. Treat. 2016, 107906321667216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.P.H.; Wong, J.Y.H.; Lo, H.H.M.; Wong, W.; Chio, J.H.M.; Fong, D.Y.T. The association between smartphone dating applications and college students’ casual sex encounters and condom use. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2016, 9, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.P.H.; Wong, J.Y.H.; Lo, H.H.M.; Wong, W.; Chio, J.H.M.; Fong, D.Y.T. Association between using smartphone dating applications and alcohol and recreational drug use in conjunction with sexual activities in college students. Subst. Use Misuse 2017, 52, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.P.-H.; Wong, J.Y.-H.; Lo, H.H.-M.; Wong, W.; Chio, J.H.-M.; Fong, D.Y.-T. The impacts of using smartphone dating applications on sexual risk behaviours in college students in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coduto, K.D.; Lee-Won, R.J.; Baek, Y.M. Swiping for trouble: Problematic dating application use among psychosocially distraught individuals and the paths to negative outcomes. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2020, 37, 212–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, L.; Duguay, S. Tinder’s lesbian digital imaginary: Investigating (im)permeable boundaries of sexual identity on a popular dating app. New Media Soc. 2020, 22, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filice, E.; Raffoul, A.; Meyer, S.B.; Neiterman, E. The influence of Grindr, a geosocial networking application, on body image in gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men: An exploratory study. Body Image 2019, 31, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedel, W.C.; Krebs, P.; Greene, R.E.; Duncan, D.T. Associations between perceived weight status, body dissatisfaction, and self-objectification on sexual sensation seeking and sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men using Grindr. Behav. Med. 2017, 43, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.M.; Turner, D.; Logan, R.G. Exploring the effect of sharing common Facebook friends on the sexual risk behaviors of Tinder users. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.; Canevello, A.; McAnulty, R.D. Motives and concerns associated with geosocial networking app usage: An exploratory study among heterosexual college students in the United States. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, H.A.; You, D.S.; Sferra, M.; Hubbard, M.; Thamotharan, S.; Fields, S.A. Is it too soon to meet? Examining differences in geosocial networking app use and sexual risk behavior of emerging adults. Sex. Cult. 2018, 22, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, M.M.; Zdravkov, J.; Plaha, K.; Cooper, F.; Allen, K.; Fuller, L.; Jones, R.; Day, S. Digital sex and the city: Prevalent use of dating apps amongst heterosexual attendees of genito-urinary medicine (GUM) clinics. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2016, 92, A1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kesten, J.M.; Dias, K.; Burns, F.; Crook, P.; Howarth, A.; Mercer, C.H.; Rodger, A.; Simms, I.; Oliver, I.; Hickman, M.; et al. Acceptability and potential impact of delivering sexual health promotion information through social media and dating apps to MSM in England: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauckner, C.; Truszczynski, N.; Lambert, D.; Kottamasu, V.; Meherally, S.; Schipani-McLaughlin, A.M.; Taylor, E.; Hansen, N. “Catfishing,” cyberbullying, and coercion: An exploration of the risks associated with dating app use among rural sexual minority males. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2019, 23, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeFebvre, L.E. Swiping me off my feet: Explicating relationship initiation on Tinder. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2018, 35, 1205–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licoppe, C. Liquidity and attachment in the mobile hookup culture. A comparative study of contrasted interactional patterns in the main uses of Grindr and Tinder. J. Cult. Econ. 2020, 13, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Y.; Mi, G.; Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Rou, K.; Zhao, Y.; Scott, S.R. App use frequency and condomless anal intercourse among men who have sex with men in Beijing, China: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. STD AIDS 2019, 30, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, C.; Ranzini, G. Where dating meets data: Investigating social and institutional privacy concerns on Tinder. Soc. Media Soc. 2017, 3, 205630511769773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M.; Messenger, A.; Perry, R.; Brewer, G. The Dark Tetrad in Tinder: Hook-up app for high psychopathy individuals, and a diverse utilitarian tool for Machiavellians? Curr. Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macapagal, K.; Kraus, A.; Moskowitz, D.A.; Birnholtz, J. Geosocial networking application use, characteristics of app-met sexual partners, and sexual behavior among sexual and gender minority adolescents assigned male at birth. J. Sex. Res. 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macapagal, K.; Moskowitz, D.A.; Li, D.H.; Carrión, A.; Bettin, E.; Fisher, C.B.; Mustanski, B. Hookup app use, sexual behavior, and sexual health among adolescent men who have sex with men in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 62, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, E.; Grieve, R.; Marrington, J.; Jonason, P.K. Trolling on Tinder® (and other dating apps): Examining the role of the Dark Tetrad and impulsivity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 110, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B. A picture is worth 1000 messages: Investigating face and body photos on mobile dating apps for men who have sex with men. J. Homosex. 2019, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.; Behm-Morawitz, E. “Masculine Guys Only”: The effects of femmephobic mobile dating application profiles on partner selection for men who have sex with men. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numer, M.; Holmes, D.; Joy, P.; Thompson, R.; Doria, N. Grinding against HIV discourse: A critical exploration of social sexual practices in gay cruising apps. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2019, 23, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orosz, G.; Benyó, M.; Berkes, B.; Nikoletti, E.; Gál, É.; Tóth-Király, I.; Bőthe, B. The personality, motivational, and need-based background of problematic Tinder use. J. Behav. Addict. 2018, 7, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orosz, G.; Tóth-Király, I.; Bőthe, B.; Melher, D. Too many swipes for today: The development of the Problematic Tinder Use Scale (PTUS). J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, L.; Comunello, F. Dating in the time of “relational filter bubbles”: Exploring imaginaries, perceptions and tactics of Italian dating app users. Commun. Rev. 2020, 23, 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, A.A.F.L.N.; de Sousa, A.F.L.; Brignol, S.; Araújo, T.M.E.; Reis, R.K. Vulnerability to HIV among older men who have sex with men users of dating apps in Brazil. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 23, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranzini, G.; Lutz, C. Love at first swipe? Explaining Tinder self-presentation and motives. Mob. Media Commun. 2017, 5, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochat, L.; Bianchi-Demicheli, F.; Aboujaoude, E.; Khazaal, Y. The psychology of “swiping”: A cluster analysis of the mobile dating app Tinder. J. Behav. Addict. 2019, 8, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Campagna, J.; Attawala, R.; Richard, C.; Kakfa, C.; Rizzo, C. In the eye of the swiper: A preliminary analysis of the relationship between dating app use and dimensions of body image. Eat. Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, A.N.; Smith, E.R.; Benotsch, E.G. Dating Application Use and Sexual Risk Behavior Among Young Adults. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2018, 15, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreurs, L.; Sumter, S.R.; Vandenbosch, L. A prototype willingness approach to the relation between geo-social dating apps and willingness to sext with dating app matches. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, G.K.; Tatar, O.; Sutton, A.; Fisher, W.; Naz, A.; Perez, S.; Rosberger, Z. Correlates of Tinder use and risky sexual behaviors in young adults. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solis, R.J.C.; Wong, K.Y.J. To meet or not to meet? Measuring motivations and risks as predictors of outcomes in the use of mobile dating applications in China. Chin. J. Commun. 2019, 12, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Rusow, J.A.; Holguin, M.; Semborski, S.; Onasch-Vera, L.; Wilson, N.; Rice, E. Exchange and survival sex, dating apps, gender identity, and sexual orientation among homeless youth in Los Angeles. J. Prim. Prev. 2019, 40, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strubel, J.; Petrie, T.A. Love me Tinder: Body image and psychosocial functioning among men and women. Body Image 2017, 21, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumter, S.R.; Vandenbosch, L.; Ligtenberg, L. Love me Tinder: Untangling emerging adults’ motivations for using the dating application Tinder. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.T.-S. All I get is an emoji: Dating on lesbian mobile phone app Butterfly. Media Cult. Soc. 2017, 39, 816–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, E.; De Caluwé, E. Development and validation of the Tinder Motives Scale (TMS). Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, E.; De Caluwé, E. To Tinder or not to Tinder, that’s the question: An individual differences perspective to Tinder use and motives. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 110, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, E.; De Caluwé, E.; Alexopoulos, C. Why are you cheating on tinder? Exploring users’ motives and (dark) personality traits. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 89, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.; Suharlim, C.; Mattie, H.; Davison, K.; Agénor, M.; Austin, S.B. Dating app use and unhealthy weight control behaviors among a sample of U.S. adults: A cross-sectional study. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, J. What are you doing on Tinder? Impression management on a matchmaking mobile app. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 1644–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, D.A.; Niehuis, S.; Flora, J.; Punyanunt-Carter, N.M.; Arias, V.S.; Hannah Baird, R. Swiping right: Sociosexuality, intentions to engage in infidelity, and infidelity experiences on Tinder. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 133, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, O. Tinder y conductas sexuales de riesgo en jóvenes españoles [Tinder and sexual risk behaviors in Spanish youth]. Aloma 2019, 37, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, T.E.D.; Fung, T.H. “Mr Right Now”: Temporality of relationship formation on gay mobile dating apps. Mob. Media Commun. 2018, 6, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zervoulis, K.; Smith, D.S.; Reed, R.; Dinos, S. Use of ‘gay dating apps’ and its relationship with individual well-being and sense of community in men who have sex with men. Psychol. Sex. 2020, 11, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachur, R.; Copen, C.; Strona, F.; Furness, B.; Bernstein, K.; Hogben, M. P509 Use of internet/mobile dating apps to find sex partners among a nationally representative sample of men who have sex with men. In Poster Presentations; BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.: London, UK, 2019; p. A234. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, D. Disconnected connectedness: The paradox of digital dating for gay and bisexual men. J. Gay Lesbian Ment. Health 2019, 23, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, C.T. The Gay Gayze: Expressions of inequality on Grindr. Sociol. Q. 2019, 60, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowse, J.; Bolt, C.; Gaya, S. Swipe right: The emergence of dating-app facilitated sexual assault. A descriptive retrospective audit of forensic examination caseload in an Australian metropolitan service. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2020, 16, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ward, J. Looking for “interesting people”: Chinese gay men’s exploration of relationship development on dating apps. Mob. Media Commun. 2019, 205015791988855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleuteri, S.; Rossi, R.; Tripodi, F.; Fabrizi, A.; Simonelli, C. How the smartphone apps can improve your sexual wellbeing? Sexologies 2018, 27, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).