Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV)-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) presents unique challenges and opportunities for treatment, particularly regarding de-escalation strategies to reduce treatment morbidity without compromising oncological outcomes. This paper examines the role of Transoral Robotic Surgery (TORS) as a de-escalation strategy in managing HPV-related OPSCC. We conducted a comprehensive literature review from January 2010 to June 2023, focusing on studies exploring TORS outcomes in patients with HPV-positive OPSCC. These findings highlight TORS’s potential to reduce the need for adjuvant therapy, thereby minimizing treatment-related side effects while maintaining high rates of oncological control. TORS offers advantages such as precise tumor resection and the ability to obtain accurate pathological staging, which can guide the tailoring of adjuvant treatments. Some clinical trials provide evidence supporting the use of TORS in specific patient populations. The MC1273 trial demonstrated promising outcomes with lower doses of adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) following TORS, showing high locoregional tumor control rates and favorable survival outcomes with minimal side effects. ECOG 3311 evaluated upfront TORS followed by histopathologically directed adjuvant therapy, revealing good oncological and functional outcomes, particularly in intermediate-risk patients. The SIRS trial emphasized the benefits of upfront surgery with neck dissection followed by de-escalated RT in patients with favorable survival and excellent functional outcomes. At the same time, the PATHOS trial examined the impact of risk-adapted adjuvant treatment on functional outcomes and survival. The ongoing ADEPT trial investigates reduced-dose adjuvant RT, and the DART-HPV study aims to compare standard adjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT) with a reduced dose of adjuvant RT in HPV-positive OPSCC patients. These trials collectively underscore the potential of TORS in facilitating treatment de-escalation while maintaining favorable oncological and functional outcomes in selected patients with HPV-related OPSCC. The aim of this scoping review is to discuss the challenges of risk stratification, the importance of HPV status determination, and the implications of smoking on treatment outcomes. It also explores the evolving criteria for adjuvant therapy following TORS, focusing on reducing radiation dosage and volume without compromising treatment efficacy. In conclusion, TORS emerges as a viable upfront treatment option for carefully selected patients with HPV-positive OPSCC, offering a pathway toward treatment de-escalation. However, selecting the optimal candidate for TORS-based de-escalation strategies is crucial to fully leverage the benefits of treatment de-intensification.

1. Introduction

Traditionally, oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) has been associated with habits like alcohol consumption and tobacco use. However, in many high-income countries, there has been a decline in smoking rates over the past two decades, leading to a decrease in the overall incidence of HNSCC. Despite this trend, the prevalence of OPSCC has risen due to another significant risk factor: infection with carcinogenic strains of human papillomavirus (HPV). This viral infection has become increasingly recognized as a critical driver behind the increased incidence of OPSCC during the same period [1].

Available evidence indicates a favorable prognosis for patients with HPV-related OPSCC when compared to those who are HPV-unrelated. This enhanced outcome is mainly due to the heightened responsiveness of HPV-positive tumors to radiation and chemotherapy treatments [2]. Traditionally, treatment protocols for both HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPSCC have been similar despite their different clinical outcomes [3]. Expanding on the unique biological and clinical characteristics of HPV-positive versus HPV-negative OPSCC can provide a more precise rationale for tailored treatment approaches, such as TORS as a de-escalation strategy, which is particularly beneficial for HPV-positive cases. This approach clarifies the specialized needs of these patients and underscores the significance of such distinctions in the broader context of head and neck oncology [3].

Traditionally, HPV-related OPSCC was primarily managed through radiotherapy (RT), administered as intensity-modulated RT (IMRT) and chemotherapy (CT). Recent clinical trials have explored various strategies for less aggressive treatment approaches. These strategies can be categorized into four main types [4]:

- Modification of chemoradiation (CRT) protocols: this approach involves either reducing the dosage or replacing cisplatin with targeted drugs like cetuximab, used alongside RT.

- Sequential therapy with induction CT: patients first receive induction CT. If they show a favorable response to CT, they might then undergo a lower total dose of RT or less extensive target volume compared to the standard RT approach, or they might receive conservative surgery alone.

- RT as an exclusive approach: some studies are investigating the effectiveness of using only RT, with either a standard or reduced dose, in place of the more conventional CRT treatment.

- Minimally invasive transoral surgery, such as transoral robotic surgery (TORS) or transoral laser microsurgery (TLM): these surgical approaches are gaining prominence, particularly for early-stage HPV-related OPSCC (T1-T2). They offer improved visualization and precise control, facilitating thorough pathological staging through resection with clear margins. The detailed insights obtained from surgical staging may enable more personalized postoperative treatments, particularly in HPV-positive patients, potentially minimizing the need for intensive follow-up therapies and associated complications. Furthermore, in cases where HPV-positive lymph node cervical metastases are present without a detectable primary tumor (CUP), TORS plays a crucial role in identifying the primary tumor site, allowing for a reduction in RT field or dosage to the oropharyngeal mucosa. The advent of de-escalation strategies represents a significant evolution in the management of OPSCC. With its ability to provide precise surgical staging and facilitate targeted therapy, TORS aligns with the goals of de-escalation strategies by enabling tailored treatment plans that optimize outcomes while minimizing treatment-related toxicities [5].

In the context of HPV-related OPSCC, the decision to opt for surgical methods like TORS over non-surgical treatments such as CRT should consider the possibility of lessening the intensity of adjuvant therapy in order to reduce the burden of toxicity. This article aims to provide insights into the decision-making process regarding the use of TORS and the potential for reduced postoperative adjuvant treatment in OPSCC, enhancing functional outcomes and quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

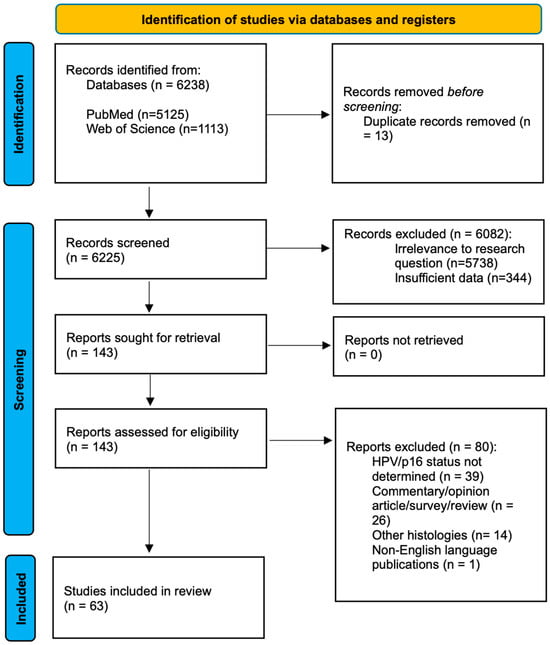

We strictly adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [6] guidelines.

For our search strategy, we conducted a thorough systematic search of articles published between January 2010 and June 2023 in the PubMed and Web of Science databases with the combined query: (“HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer” OR “HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma” OR “OPSCC”) AND (“treatment” OR “therapeutic approaches” OR “management” OR “surgical options” OR “radiation therapy” OR “chemotherapy” OR “de-escalation” OR “intensity reduction” OR “outcomes” OR “quality of life” OR “TORS”). The choice of this time frame is because, to our knowledge, the concept of de-escalation in the management of OPSCC has gained ground since 2010 [7], subsequently developing with new studies.

Subsequently, the full text of relevant studies was screened for final selection. All studies identified by the initial literature search were reviewed independently by two authors. All titles and abstracts were assessed. Our selection criteria for studies on OPSCC included articles published between January 2010 and June 2023, featuring patients with confirmed OPSCC diagnoses based on histopathological examination, with a precise determination of HPV or p16 status on surgical specimens, who underwent TORS. We excluded duplicate publications, reviews, case series with fewer than ten patients, book chapters, case reports, and poster presentations. Our focus was explicitly on OPSCC studies, and we excluded those discussing other histologies or surgical treatments aside from TORS. Additionally, studies lacking clarity on HPV or p16 status or not published in English were excluded from our analysis.

The selection process is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA.

3. Results

Following the screening process, we assessed the abstracts and reviewed the full texts of the articles. Our selection led to the inclusion of 63 relevant articles, and we compiled essential information for each article, including authorship, country, publication year, sample size, and key findings. The articles are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selected studies.

Through the examination of the chosen articles, we identified key areas that raise questions regarding the assessment of HPV status, the patients’ selection, the guidelines for endorsing or discouraging the use of TORS, and the potential roles of TORS in the context of de-escalation strategies.

4. Discussion

4.1. HPV Status Determination

Identifying HPV status is crucial in HPV-associated OPSCC, as it indicates a unique disease type with a specific molecular background. The immunohistochemical detection of p16, a key marker for HPV positivity, is of paramount importance in this context. The overexpression of p16, often a result of HPV types 16 and 18 disrupting p53 and pRB through their oncoproteins E6 and E7, serves as a proxy for HPV involvement in these cancers. The threshold for determining p16+ by immunohistochemistry is a nuclear expression of ≥+2/+3 with a distribution of >75% of the neoplasm [71].

Patients with p16-positive OPSCC exhibit markedly different prognoses compared to those with p16 negative OPSCC. Younger patients with p16-positive OPSCC generally show better treatment responses. For instance, a 5-year overall survival rate for stage IV p16 positive OPSCC is about 70%, significantly higher than the 30% for p16 negative cases. The 8th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual reflects these differences, offering distinct staging criteria for p16-positive and -negative OPSCC [72].

Another critical concern is assessing p16 expression and HPV DNA presence in OPSCC cases. The gold standard approach involves examining both factors since some cases may exhibit discordance between them. Notably, patients who are either p16- or HPV-positive tend to have a more favorable prognosis compared to those who are negative for both. However, those who are positive for both p16 and HPV show an even better prognosis, indicating an intermediate prognosis for patients with single positivity [73]. These highlight the need to include ‘real’ HPV+ OPSCC in future studies, and especially in a de-escalation setting.

4.2. Risk Determination

Several prognostic models have emerged, factoring in p16 status, smoking history, and other clinical parameters. Ang et al. [7] identified three risk groups based on these factors, observing a significant difference in overall-survival (OS) between non-smoker p16-positive patients and p16-positive patients with a smoking history of >10 pack–year and N2–N3 disease. However, their classification was limited to a specific trial population. Deschuymer et al. [74] introduced a new risk group classification for p16-positive OPSCC, focusing on the 8th staging edition, comorbidities, and smoking history. They identified a low-risk group of patients, defined as stage I, never smokers or smokers with less than 10 pack–year smoking history and low comorbidity, that showed an excellent prognosis and could benefit from de-escalation trials. Rietbergen proposed another risk model based on an unselected European cohort, considering comorbidities along with p16 status and N-stage [75]. Lassen et al. [76] further emphasized the impact of smoking on survival in p16-positive OPSCC patients, suggesting that active smokers and >30 pack–year history patients might not be ideal candidates for de-escalation trials due to decreased radiotherapy efficacy.

One key factor that could reduce the effectiveness of RT in individuals who actively smoke is tumor hypoxia. This is because the mechanism of RT largely relies on generating free radicals, a process heavily dependent on the presence and level of oxygen within the tumor. Smoking is known to lower the effectiveness of hemoglobin and the delivery of oxygen to tissues, including tumor cells [77]. However, current research on the influence of smoking in patients undergoing surgical treatments remains limited.

A study conducted by Roden et al. [78], primarily focusing on patients in clinical stage I OPSSC, found that smoking did not significantly affect recurrence-free survival (RFS), OS, or disease-specific survival (DSS). These patients underwent TORS as an initial treatment, followed by pathology-guided adjuvant therapy. The study observed that smokers were more likely to present with extra capsular spreading (ECS) and positive margins, potentially leading to more intensive treatment. However, these factors did not seem to adversely affect their prognosis. The authors of the study hypothesize that the surgical removal of tumor bulk might enhance the effectiveness of RT in such cases where tissue oxygenation is compromised due to smoking. This does not seem to adversely affect local tumor control. Therefore, they suggest that smokers, especially those with early-stage HPV-related OPSCC falling into the intermediate risk category, should not be automatically excluded from TORS-based de-escalation clinical trials.

In this regard, a recent study added information on the predictive role of tumor hypoxia in response to radiation and the possibility of modulating the dose of radiotherapy. The use of functional hypoxia imaging allowed for a drastic reduction in the dose of radiation to 30 Gy without hampering treatment efficacy and with advantages in acute and late toxicities [79].

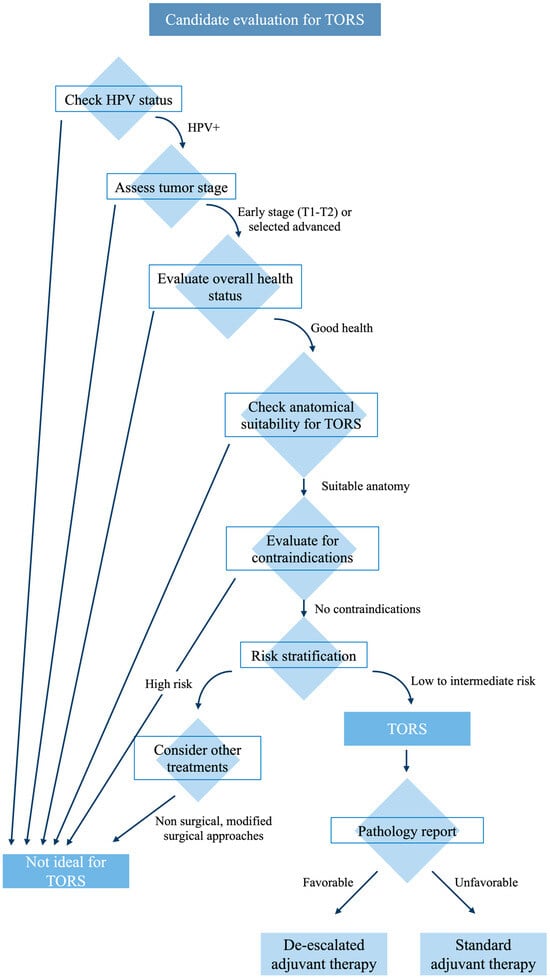

4.3. TORS Indication

TORS is emerging as a preferred treatment for HPV-positive OPSCC, offering advantages like a reduced need for reconstructive surgery and shorter operation times compared to traditional methods. TORS follows principles of minimal invasiveness and patient-specific factors like anatomy, and prior treatments significantly influence its feasibility [80,81,82]. Preoperative evaluations, including the 8Ts of endoscopic access (teeth, trismus, transverse mandibular dimensions, tori, tongue, tilt, prior RT, and tumor) [83], are also crucial in determining the suitability of TORS for a patient.

Obviously, in addition to the characteristics related to the patient, there are also characteristics related to the tumor that must be taken into consideration. In particular, three categories of contraindications to TORS related to the tumor have been identified: vascular, functional, and oncological [82].

Regarding vascular factors, TORS is not recommended in cases where a tonsillar malignancy is present alongside a retropharyngeal carotid artery, or if the tumor is located centrally at the tongue base or in the vallecula. Additionally, the proximity of the tumor to vital vascular structures such as the carotid bulb or internal carotid artery, or carotid artery encasement by the tumor or metastatic neck nodes, also rules out the use of TORS. From a functional perspective, TORS is contraindicated if the tumor removal would necessitate the excision of more than half of the deep musculature of the tongue base or the posterior pharyngeal wall. Similarly, TORS is not suitable in case of both tongue base and entire epiglottis removal. On an oncological level, there are several scenarios where TORS appears inappropriate: advanced cancers (T4b), unresectable neck disease, or in the case of multiple and multiple-site metastases. Even trismus caused by the tumor, the prevertebral fascia or the mandible or hyoid bones involvement, the lateral neck’s soft tissues tumor extension, or Eustachian tube involvement do preclude the use of TORS [84].

Despite the evolving role of TORS, the optimal postoperative treatment for HPV-positive OPSCC following this surgery remains to be defined (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Candidate selection summary.

4.4. Role of TORS as a De-Escalation Strategy

Over the last decade, TORS has been increasingly used in the treatment of HPV-related OPSCC. In a de-intensification treatment scenario, the histopathological data obtained from initial surgical procedures might provide an opportunity to lower the adverse side effects associated with non-surgical adjuvant treatments, both in the short and long term.

Some clinical trials evaluate de-escalation after TORS.

The MC1273 trial was a phase II study that focused on using a lower dose of adjuvant RT after TORS/TLM. It included patients with HPV-positive OPSCC and a smoking history of less than 10 pack–year and had undergone a surgical removal of tumors with clear margins [85].

Patients at intermediate risk received 30 Gy of adjuvant RT over 2 weeks, while those with ECS on their final pathology report received 36 Gy. The trial showed promising results, with a 2-year locoregional tumor control rate of 96.2%, a progression-free survival rate of 91.1%, and an overall survival rate of 98.7%. The occurrence of severe side effects before RT and at 1- and 2-year follow-ups was low, at 2.5%, 0%, and 0%, respectively. Additionally, there was a slight improvement in swallowing function between the time before RT and 12 months after RT [85].

ECOG 3311 (NCT01898494) took into consideration HPV+ OPSCC in stages III–IVb, the treatment performed was upfront TORS followed by histopathologically directed adjuvant therapy in order to identify which selected patients could benefit from de-escalated RT (observation/50 vs. 60 Gy/66 Gy with weekly cisplatin). This clinical trial showed that primary TORS and reduced postoperative RT result in good oncological outcome and favorable functional outcomes in intermediate-risk HPV+ OPSCC, even if the highest difference in quality of life and swallowing were identified when comparing the single modality or the double modality with the tri-modality treatment [86].

SIRS Trial (NCT02072148) took into consideration only T1 and T2 categories. After TORS, patients were assigned to group 1 (no poor risk features; surveillance), group 2 (intermediate pathological risk factors [perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion]; 50-Gy radiotherapy), or group 3 (poor prognostic pathological factors [ECS, more than three positive lymph nodes and positive margins]; concurrent 56-Gy chemoradiotherapy with weekly cisplatin). The findings suggest that performing upfront surgery with neck dissection, followed by a de-escalated RT, is associated with favorable survival outcomes and excellent functional outcomes in patients with T1–2, N1 stage p16+ OPSCC [87].

Clinical trial PATHOS (NCT02215265) is another phase II trial examining the impact of a transoral laser resection of tumors followed by risk-adapted adjuvant treatment, on functional outcomes and survival. Patients undergo TLM/TORS resection of tumors, and are then randomized to reduced dose RT or standard dose RT or to concurrent chemoradiation or RT alone, according to pathological risk factors [88].

ADEPT trial (NCT01687413) is currently investigating reduced dose-adjuvant RT and removal of chemotherapy from the adjuvant regimen of patients with ECS on final pathology [89].

The DART-HPV study (NCT02908477) is presently in the process of enrolling participants at the Mayo Clinic. In this study, patients with HPV-positive OPSCC who have undergone transoral resection and meet the criteria for adjuvant treatment are randomly assigned to either receive standard adjuvant CRT or docetaxel in combination with a reduced dose of adjuvant RT (30 Gy administered over two weeks).

4.5. TORS as a De-Escalation Strategy for cT1-cT2

Currently, there is a lack of consensus regarding the optimal supplementary treatment following upfront TORS for patients with stage I OPSCC who test positive for p16. The primary areas of uncertainty in the postoperative phase focused on two key aspects: the necessity for concurrent CT when dealing with ECS and positive margins and determining the appropriate RT dose and volume size in relation to the extent of surgical intervention. [90]

The criteria for recommending adjuvant RT are derived from the guidelines established by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [91]. These criteria include: ECS, close or positive margins, pT3 or pT4 primary tumor, one positive lymph node measuring >3 cm or multiple positive nodes, nodal involvement in levels IV or V, perineural invasion, vascular invasion, and lymphatic invasion [92].

In cases of margin positivity or ECS, combining CT with RT is highly recommended [93].

Some studies have shown that TORS yields positive oncological and functional results in the management of early-stage HPV-related OPSCC [8,11,21,22,26,27,34,35,38,41,44,48,51,61,64,69]. In clinical practice, many patients diagnosed with cT1 and cT2 HPV-related OPSCC often undergo upfront TORS. The indication for adjuvant RT with or without concomitant CT follows the abovementioned criteria, considering the number and types (major versus minor) of risk factors. The standard approach for RT involves targeting the primary tumor and lymph node regions at risk, delivering a dosage ranging from 50 to 66 Gy with conventional fractionation.

When it comes to strategies for de-intensifying adjuvant RT, two main options are being explored:

- Reducing the RT total dose;

- Reducing the extension of RT target volumes. One noteworthy strategy being investigated involves omitting adjuvant RT to the primary tumor site in cases of early T stages [89].

TORS enables precise intraoperative margin assessment, leading to a high rate of margin-negative resections and consequently low local recurrence rates, especially in early T-stage tumors [13,42,46,57,64]. The potential benefit of excluding the primary tumor site from the radiation field lies in minimizing local toxicity in a critical anatomical area, thus resulting in reduced treatment-related morbidity.

In a 2016 study, it was demonstrated that excluding RT treatment to the primary tumor site in margin-negative resected T1–T2 p16-positive OPSCC did not result in a significant compromise in terms of local control [94]. Among 202 T1–T2 patients, 92 did not receive planned RT to the primary tumor bed, with 48 of them not receiving any adjuvant treatment and 44 receiving RT only to the ipsilateral neck [94]. This group showed a local recurrence rate of 3%, compared to 0% in patients who received radiation to the primary site [94]. Furthermore, patients who did not receive planned RT to the primary site exhibited superior preservation of the swallowing function, with a temporary gastrostomy rate of 6.5%, in contrast to 41% in patients who received radiation to the primary site [94].

The first prospective single-arm phase II clinical trial published in 2020 from University of Pennsylvania (NCT02159703) yielded different outcomes when assessing the safety and effectiveness of focusing RT solely on the neck, while excluding treatment for the primary tumor site. This study included 60 patients diagnosed with stage pT1–pT2, N1–3 p16-positive OPSCC who had undergone TORS and selective neck dissection (SND). All these patients exhibited favorable features at the primary site, including negative surgical margins (≥2 mm), the absence of perineural invasion, and no lymphovascular invasion. Adjuvant RT +/− CT was administered based on lymph node involvement, including patients with extranodal extension (ENE). Target volumes (TV) for RT were defined as follows: TV1 included the ipsilateral lymph node levels II, III, and IV and any other involved lymph node level; TV2 generally included the ipsilateral level V, lateral retropharyngeal nodal stations, and the contralateral level II, III, and IV; TV3 included areas of pathological ENE if applicable. Prescriptions for the different neck TVs were 60 Gy, 54 Gy, and 63–66 Gy, respectively, in 30–33 treatment fractions. RT target volumes included all study patients’ selective nodal regions of the bilateral neck. The primary tumor site was defined as the TORS operational bed and was contoured as an avoidance structure for RT planning.

Despite this reduction in radiation dosage to the different risk areas in the neck and the primary tumor site avoidance in radiation, the study reported an excellent 2-year local control rate of 98.3% and a recurrence-free survival rate of 97.9%. Regarding adverse effects, only 3.3% of patients required a temporary feeding tube, and there was an extremely low incidence (3.3%) of soft tissue necrosis in the operative bed at the primary tumor site [61]. However, it should be observed that, due to RT planning, the mean ‘unwanted’ dose administered to the primary surgical bed was 36 Gy which is a dose equal or superior to those administered in aggressive de-escalation trials such as the MC1273 and MC1675 [85].

Additionally, another observational study conducted at the Mayo Clinic (NCT02736786) is investigating the clinical and functional outcomes of mucosal sparing proton beam therapy in patients with resected T1–T2 p16-positive oropharyngeal tumors characterized by negative margins and the absence of perineural invasion and lymphovascular invasion at the primary site [95].

This strategy to test an RT volume de-escalation approach is highly intriguing. Proton therapy offers improved tumor conformity compared to conventional photon-based radiotherapy, allowing for an accurate evaluation of volume de-escalation efficacy. It eliminates biases related to low and intermediate doses, which may control microscopic disease. Due to the proximity of the highest nodal station to the oropharyngeal mucosa, omitting low to intermediate doses—which is impossible with high conformal radiotherapy (i.e., IMRT)—could provide valuable insights into the efficacy of not irradiating the primary tumor bed after TORS [96].

4.6. TORS as a De-Escalation Strategy for cT3–cT4

Although TORS is often used for tumors at lower T stages, it has been employed in cases with advanced cervical disease, where it serves as the initial treatment followed by adjuvant RT and possibly CT. The existing literature presents promising data concerning oncological outcomes.

White et al. conducted a review involving 89 patients, 65% of whom had either T3–T4 tumors or N2–N3 disease [97]. This study showed that 92% of patients underwent TORS as their primary treatment, resulting in an overall 2-year survival rate of 89.3% [97]. Other studies reported comparable results [98,99]. In addition to the oncological benefits, they were employing TORS as the first-line treatment, and this offers advantages such as the ability for pathological analysis, which can lead to the upstaging or downstaging of the patient’s disease. This, in turn, may allow for a reduction in radiation doses and the potential avoidance of CT. Furthermore, the utilization of TORS offers the potential to mitigate the risk of positive margins, consequently enhancing patient survival outcomes. [37].

Hurtuk et al. reviewed 64 patients who underwent TORS, with 68.4% classified as N2–N3. The analysis of pathological specimens resulted in CT avoidance in 34% of patients with stage III/IV tumors [100]. However, this strategy should be used with caution because there is a risk involved in using a trimodality approach, which has been linked to a significant risk of acute and late toxicities that can negatively influence the quality of life [86].

In a study by Lukens et al., a 28% rate of late soft tissue necrosis was reported among patients with locally advanced oropharyngeal carcinoma who underwent treatment with TORS followed by postoperative RT. Tonsillar location, the depth of resection, radiation dose to the surgical bed, and severe mucositis were identified as independent risk factors, prompting the authors to carefully avoid a radiation dose exceeding 2 Gy per day to the surgical bed [101].

Another emerging field in this regard is the combination of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NCT) followed by TORS. Sadeghi et al. published a prospective cohort of patients with HPV+ locoregional advanced OPSCC undergoing NCT + transoral surgery, which was compared to a historical cohort of patients undergoing CRT. The NCT + surgery group demonstrated superior DSS and disease-free survival (DFS) compared to the CRT group, with a lower incidence of severe treatment-related toxicity and feeding tube dependence [102,103].

Costantino et al. at Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, proposed a treatment protocol consisting of NCT, including cisplatin and itanium silicate (TS-1), administered over several cycles in patients with locoregionally advanced OPSCC. About 70% of patients were p16+. TORS was performed after assessing the tumor response to NCT. The surgical approach aims to achieve a complete resection guided by pre-NCT assessments, with subsequent pathological evaluation guiding the need for adjuvant treatments. The primary tumor site showed a pathological complete response in 32.8% of patients, while regional lymph nodes exhibited a complete response in 43%. The estimated DFS rates at 1 and 3 years were 86.6% and 81.4%, respectively, with DSS rates at 1 and 3 years of 96.7% and 92.6% [20,104,105]. However, further studies are warranted to validate these findings and define the optimal integration of this treatment approach into clinical practice.

4.7. Functional Results and Quality of Life

While TORS presents a less invasive surgical approach for managing HPV+ OPSCC, the literature reveals a notable gap in comparative data on functional outcomes and quality of life across different treatment de-escalation strategies. The present studies, in fact, are characterized by a limited sample size and a relatively short follow-up period. This gap is particularly significant given the typically younger demographic and high survival rates associated with HPV+ OPSCC patients, for whom the long-term quality of life, including swallowing function and other critical functionalities, is a paramount consideration.

TORS is recognized for its minimal invasiveness and potential to yield excellent oncological outcomes. However, the necessity for adjuvant therapy, in some cases, may mitigate TORS’s benefits in terms of functional outcomes, potentially exacerbating morbidity, especially in terms of swallowing function. The nuanced balance between achieving optimal cancer control and preserving quality of life underscores the need for more robust comparative studies. Specifically, more comprehensive data must be collected to compare the functional outcomes and quality of life among patients undergoing TORS and TORS followed by de-escalated adjuvant therapy versus those subjected to de-escalated CRT or standard CRT protocols.

This deficiency in the literature highlights an urgent need for focused research efforts. Such research is essential for guiding clinical decisions that aim for the best oncological outcomes and prioritize patients’ long-term well-being and quality of life.

4.8. Further Considerations

In wrapping up our discussion on integrating TORS into clinical settings, it is imperative to critically evaluate the challenges and opportunities that this innovative surgical approach presents. The effective integration of TORS involves a consideration of several key factors.

Surgeon training and proficiency: TORS requires technical insight and a deep understanding of the complex anatomical structures affected by OPSCC. The necessity for robust training programs cannot be overstated; such initiatives ensure that surgeons are well equipped to handle the intricacies of robotic surgery. Moreover, establishing certification processes will uphold the standards of safety and efficacy that are paramount in surgical interventions. This rigorous approach to training will safeguard the quality of care provided to patients and maintain the integrity of the medical profession.

Resource allocation: the financial outlay required for procuring and maintaining robotic systems is substantial. However, one should also consider the potential long-term benefits when evaluating such investments. These include decreased complication rates and shorter recovery periods, which can significantly reduce overall healthcare costs and improve patient throughput. Therefore, a balanced perspective on resource allocation—one that weighs initial costs against long-term savings and patient benefits—is essential for making informed decisions that will benefit healthcare institutions and their patients.

Development of follow-up care protocols: establishing comprehensive follow-up protocols is crucial in monitoring the recovery and assessing the long-term functional outcomes of patients undergoing TORS. Such protocols are indispensable for ensuring ongoing patient health and well-being, evaluating their effectiveness, and refining the practice of TORS. Regular and systematic follow-ups will provide a wealth of data to inform future improvements in technique and patient care protocols.

5. Conclusions

TORS can be considered an upfront treatment option for selected patients to de-escalate the management of HPV-related OPSCC. However, the key to its appropriate use lies in carefully selecting candidates based on risk stratification associated with the patient and the tumor. There must be no anatomical or tumor-related contraindications to perform TORS.

In summarizing our review of TORS for de-escalating treatment in HPV-related OPSCC, we recognize the compelling evidence of its benefits. However, we must address several critical gaps through future research to fully leverage TORS in clinical settings.

Long-term clinical outcomes: while the short-term efficacy of TORS is well-documented, long-term survival, recurrence rates, and late complications remain less understood. Ongoing longitudinal studies are crucial to confirm the sustained benefits of TORS and its role in enhancing patient survival over decades.

Comparative effectiveness: there is a conspicuous need for direct comparisons between TORS and conventional non-surgical modalities. More randomized controlled trials could elucidate differential outcomes in efficacy, safety, and quality of life, providing a more robust foundation for treatment decision making.

Integration with emerging therapies: as new treatments such as immunotherapy emerge, their integration with TORS could redefine therapeutic protocols. Investigating these combinations could open up new pathways for personalized medicine, potentially increasing the cure rates while minimizing adverse effects.

By addressing these areas, future research can substantially advance our understanding and application of TORS, ultimately enhancing the therapeutic landscape for patients with HPV-related OPSCC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M. (Gabriele Molteni); methodology, G.M. (Gabriele Molteni) and S.B.; investigation, A.E.A. and E.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, G.M. (Giuditta Mannelli), E.O., A.D.V., P.B. and G.M. (Gabriele Molteni). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lechner, M.; Liu, J.; Masterson, L.; Fenton, T.R. HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer: Epidemiology, Molecular Biology and Clinical Management. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Issaeva, N.; Yarbrough, W.G. HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer: Current knowledge of molecular biology and mechanisms of carcinogenesis. Cancers Head Neck 2018, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.M. De-Escalation Treatment for Human Papillomavirus–Related Oropharyngeal Cancer: Questions for Practical Consideration. Oncology 2023, 37, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlandi, E.; Licitra, L. The day after De-ESCALaTE and RTOG 1016 trials results. Future Oncol. 2019, 15, 2069–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Martinez, E.; Kulich, M.; Swanson, M.S. Surgeon practice patterns in transoral robotic surgery for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2021, 121, 105460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, K.K.; Harris, J.; Wheeler, R.; Weber, R.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Nguyen-Tân, P.F.; Westra, W.H.; Chung, C.H.; Jordan, R.C.; Lu, C.; et al. Human Papillomavirus and Survival of Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achim, V.; Bolognone, R.K.; Palmer, A.D.; Graville, D.J.; Light, T.J.; Li, R.; Gross, N.; Andersen, P.E.; Clayburgh, D. Long-term Functional and Quality-of-Life Outcomes After Transoral Robotic Surgery in Patients With Oropharyngeal Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 144, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albergotti, W.G.; Jordan, J.; Anthony, K.; Abberbock, S.; Wasserman-Wincko, T.; Kim, S.; Ferris, R.L.; Duvvuri, U. A Prospective Evaluation of Short-Term Dysphagia after Transoral Robotic Surgery for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oropharynx. Cancer 2017, 123, 3132–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amit, M.; Hutcheson, K.; Zaveri, J.; Lewin, J.; E Kupferman, M.; Hessel, A.C.; Goepfert, R.P.; Gunn, G.B.; Garden, A.S.; Ferraratto, R.; et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes of Symptom Burden in Patients Receiving Surgical or Nonsurgical Treatment for Low-Intermediate Risk Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Comparative Analysis of a Prospective Registry. Oral Oncol. 2019, 91, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliga, S.; Kabarriti, R.; Jiang, J.; Mehta, V.; Guha, C.; Kalnicki, S.; Smith, R.V.; Garg, M.K. Utilization of Transoral Robotic Surgery (TORS) in patients with Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and its impact on survival and use of chemotherapy. Oral Oncol. 2018, 86, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biron, V.L.; O’connell, D.A.; Barber, B.; Clark, J.M.; Andrews, C.; Jeffery, C.C.; Côté, D.W.J.; Harris, J.; Seikaly, H. Transoral Robotic Surgery with Radial Forearm Free Flap Reconstruction: Case Control Analysis. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2017, 46, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brody, R.M.; Shimunov, D.; Cohen, R.B.; Lin, A.; Lukens, J.N.; Hartner, L.; Aggarwal, C.; Duvvuri, U.; Montone, K.T.; Jalaly, J.B.; et al. A Benchmark for Oncologic Outcomes and Model for Lethal Recurrence Risk after Transoral Robotic Resection of HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Cancers. Oral Oncol. 2022, 127, 105798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannavicci, A.; Cioccoloni, E.; Moretti, F.; Cammaroto, G.; Iannella, G.; De Vito, A.; Sgarzani, R.; Gessaroli, M.; Ciorba, A.; Bianchini, C.; et al. Single Centre Analysis of Perioperative Complications In Trans-Oral Robotic Surgery for Oropharyngeal Carcinomas. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 75, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, R.B.; Houlton, J.J.; Patel, S.; Raju, S.; Noble, A.; Futran, N.D.; Parvathaneni, U.; Méndez, E. Patterns of Cervical Node Positivity, Regional Failure Rates, and Fistula Rates for HPV+ Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Treated with Transoral Robotic Surgery (TORS). Oral Oncol. 2018, 86, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, R.M.; Brody, R.M.; Shimunov, D.; Shinn, J.R.; Mady, L.J.; Rajasekaran, K.; Cannady, S.B.; Lin, A.; Lukens, J.N.; Bauml, J.M.; et al. Locoregional Recurrence in p16-Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma After TORS. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E2865–E2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, H.; Schonewolf, C.A.; Tan, E.X.; Swisher-McClure, S.; Ghiam, A.F.; Weinstein, G.S.; O’Malley, B.W.; Chalian, A.A.; Rassekh, C.H.; Newman, J.G.; et al. The Impact of Treatment Package Time on Locoregional Control for HPV+ Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Treated with Surgery and Postoperative (Chemo)Radiation. Head Neck 2019, 41, 3858–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Sinha, P.; Last, A.; Ettyreddy, A.; Kallogjeri, D.; Pipkorn, P.; Rich, J.T.; Zevallos, J.P.; Paniello, R.; Puram, S.V.; et al. Outcomes of Patients With Single-Node Metastasis of Human Papillomavirus–Related Oropharyngeal Cancer Treated With Transoral Surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 147, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Last, A.; Ettyreddy, A.; Kallogjeri, D.; Wahle, B.; Chidambaram, S.; Mazul, A.; Thorstad, W.; Jackson, R.S.; Zevallos, J.P.; et al. 20 Pack-Year Smoking History as Strongest Smoking Metric Predictive of HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer Outcomes. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, A.; Sampieri, C.; De Virgilio, A.; Kim, S.-H. Neo-Adjuvant Chemotherapy And Transoral Robotic Surgery in Locoregionally Advanced Oropharyngeal Cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 49, 107121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.D.; Ferris, R.L.; Kim, S.; Duvvuri, U. Primary Surgery for Human Papillomavirus-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer: Survival Outcomes with or without Adjuvant Treatment. Oral Oncol. 2018, 87, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanireddy, B.; Burnett, N.P.; Sanampudi, S.; Wooten, C.E.; Slezak, J.; Shelton, B.; Shelton, L.; Shearer, A.; Arnold, S.; Kudrimoti, M.; et al. Outcomes in Surgically Resectable Oropharynx Cancer Treated with Transoral Robotic Surgery Versus Definitive Chemoradiation. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2019, 40, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Virgilio, A.; Pellini, R.; Cammaroto, G.; Sgarzani, R.; De Vito, A.; Gessaroli, M.; Costantino, A.; Petruzzi, G.; Festa, B.M.; Campo, F.; et al. Trans Oral Robotic Surgery for Oropharyngeal Cancer: A Multi Institutional Experience. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. (EJSO) 2023, 49, 106945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, A.L.; Holcomb, A.J.; Abt, N.B.; Mokhtari, T.E.; Suresh, K.; McHugh, C.I.; Parikh, A.S.; Holman, A.; Kammer, R.E.; Goldsmith, T.A.; et al. Feeding Tube Placement Following Transoral Robotic Surgery for Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2022, 166, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, S.E.; Brandwein-Gensler, M.; Carroll, W.R.; Rosenthal, E.L.; Magnuson, J.S. Transoral Robotic versus Open Surgical Approaches to Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Human Papillomavirus Status. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2014, 151, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederiksen, J.G.; Channir, H.I.; Larsen, M.H.H.; Christensen, A.; Friborg, J.; Charabi, B.W.; Rubek, N.; von Buchwald, C. Long-term Survival Outcomes after Primary Transoral Robotic Surgery (TORS) with Concurrent Neck Dissection for Early-Stage Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2021, 141, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groysman, M.; Yi, S.K.; Robbins, J.R.; Hsu, C.C.; Julian, R.; Bauman, J.E.; Baker, A.; Wang, S.J.; Bearelly, S. The Impact Of Socioeconomic and Geographic Factors on Access to Transoral Robotic/Endoscopic Surgery for Early Stage Oropharyngeal Malignancy. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2022, 43, 103243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haller, T.; Yin, X.; O’Byrne, T.; Moore, E.; Ma, D.; Price, K.; Patel, S.; Hinni, M.; Neben-Wittich, M.; McGee, L.; et al. 30-Day Morbidity and Mortality after Transoral Robotic Surgery for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) associated Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Analysis of Two Prospective Adjuvant De-Escalation Trials (MC1273 & MC1675). Oral Oncol. 2023, 137, 106248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.T.; Levine, B.J.; May, N.; Shenker, R.F.; Yang, J.H.; Lanier, C.M.; Frizzell, B.A.; Greven, K.M.; Waltonen, J.D. Survival and Swallowing Function after Primary Radiotherapy versus Transoral Robotic Surgery for Human Papillomavirus-Associated Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. ORL J. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. Its Relat. Spec. 2023, 85, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, A.L.; Channir, H.I.; von Buchwald, C.; Rubek, N.; Friborg, J.; Kiss, K.; Charabi, B.W. Transoral Robotic Surgery: A 4-Year Learning Experience in a Single Danish Cancer Centre. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2019, 140, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.S.; Sinha, P.; Zenga, J.; Kallogjeri, D.; Suko, J.; Martin, E.; Moore, E.J.; Haughey, B.H. Transoral Resection of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-Positive Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oropharynx: Outcomes with and Without Adjuvant Therapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 3494–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaffenberger, T.M.; Patel, A.K.; Lyu, L.; Li, J.; Wasserman-Wincko, T.; Zandberg, D.P.; Clump, D.A.; Johnson, J.T.; Nilsen, M.L. Quality of Life after radIation and Transoral Robotic Surgery in Advanced Oropharyngeal Cancer. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2021, 6, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucur, C.; Durmus, K.; Teknos, T.N.; Ozer, E. How Often Parapharyngeal Space is Encountered in TORS Oropharynx Cancer Resection. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2015, 272, 2521–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Torabi, S.J.; Park, H.S.; Yarbrough, W.G.; Mehra, S.; Choi, R.; Judson, B.L. Clinical Value Of Transoral Robotic Surgery: Nationwide Results from the First 5 Years of Adoption. Laryngoscope 2019, 129, 1844–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, D.C.; Chapman, B.V.; Kim, J.; Choby, G.W.; Kabolizadeh, P.; Clump, D.A.; Ferris, R.L.; Kim, S.; Beriwal, S.; Heron, D.E.; et al. Oncologic Outcomes and Patient-Reported Quality of Life in Patients with Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Treated with Definitive Transoral Robotic Surgery Versus Definitive Chemoradiation. Oral Oncol. 2016, 61, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.S.; Cao, A.C.; Shimunov, D.; Sun, L.; Lukens, J.N.; Lin, A.; Cohen, R.B.; Basu, D.; Cannady, S.B.; Rajasekaran, K.; et al. Functional Outcomes in Patients with Human Papillomavirus-Associated Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Cancer Treated with Trimodality Therapy. Laryngoscope 2023, 133, 3013–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lybak, S.; Ljøkjel, B.; Haave, H.; Karlsdottir, À.; Vintermyr, O.K.; Aarstad, H.J. Primary Surgery Results in No Survival Benefit Compared to Primary Radiation for Oropharyngeal Cancer Patients Stratified by High-Risk Human Papilloma Virus Status. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2016, 274, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, C.P.; Garneau, J.; Weimar, E.; Ali, S.; Farinhas, J.M.; Yu, E.; Som, P.M.; Sarta, C.; Goldstein, D.P.; Su, S.; et al. Occult Nodal Disease and Occult Extranodal Extension in Patients With Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Undergoing Primary Transoral Robotic Surgery With Neck Dissection. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 145, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meccariello, G.; Bianchi, G.; Calpona, S.; Parisi, E.; Cammaroto, G.; Iannella, G.; Sgarzani, R.; Montevecchi, F.; De Vito, A.; Capaccio, P.; et al. Trans Oral Robotic Surgery Versus Definitive Chemoradiotherapy for Oropharyngeal Cancer: 10-Year Institutional Experience. Oral Oncol. 2020, 110, 104889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, H.; Rapozo, D.; von Zeidler, S.V.; Harrington, K.J.; Winter, S.C.; Hartley, A.; Nankivell, P.; Schache, A.G.; Sloan, P.; Odell, E.W.; et al. Developing and Validating a Multivariable Prognostic-Predictive Classifier for Treatment Escalation of Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: The PREDICTR-OPC Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 30, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.S.; Zhao, J.; Boyce, B.J.; Amdur, R.; Mendenhall, W.M.; Danan, D.; Hitchcock, K.; Ning, K.; Keyes, K.; Lee, J.-H.; et al. HPV/p16-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer Treated with Transoral Robotic Surgery: The Roles of Margins, Extra-Nodal Extension and Adjuvant Treatment. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’hara, J.; Warner, L.; Fox, H.; Hamilton, D.; Meikle, D.; Counter, P.; Robson, A.; Goranova, R.; Iqbal, S.; Kelly, C.; et al. Primary Transoral Robotic Surgery +/− Adjuvant Therapy for Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma—A Large Observational Single-Centre Series from the United Kingdom. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2021, 46, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaleye, O.; Krishnan, G.; Beck, J.; Noor, A.; Bulsara, V.; Boase, S.; Solomon, P.; Krishnan, S.; Hodge, J.C.; Foreman, A. Validation of the TNM-8 AJCC Classification for HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancers in Patients Undergoing Trans-Oral Robotic Surgery. J. Robot. Surg. 2023, 17, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, B.; Edwards, J.; Stone, L.; Jiang, A.; Zhu, X.; Holland, J.; Li, R.; Andersen, P.; Krasnow, S.; Marks, D.L.; et al. Association of Sarcopenia With Oncologic Outcomes of Primary Surgery or Definitive Radiotherapy Among Patients With Localized Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 146, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.R.; Persky, M.J.; Wang, B.; Duvvuri, U.; Gross, N.D.; Vaezi, A.E.; Morris, L.G.T.; Givi, B. Transoral Robotic Surgery Adoption and Safety in Treatment of Oropharyngeal Cancers. Cancer 2022, 128, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.M.; Kim, H.R.; Cho, B.C.; Keum, K.C.; Cho, N.H.; Kim, S.-H. Transoral Robotic Surgery-Based Therapy in Patients with Stage III-IV Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2017, 75, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.M.; Jung, C.M.; Cha, D.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, H.R.; Keum, K.C.; Cho, N.H.; Kim, S.-H. A New Clinical Trial of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Combined With Transoral Robotic Surgery and Customized Adjuvant Therapy for Patients With T3 or T4 Oropharyngeal Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 3424–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.M.; Kim, D.H.; Kang, M.S.; Lim, J.Y.; Choi, E.C.; Koh, Y.W.; Kim, S.-H. The First Human Trial of Transoral Robotic Surgery Using a Single-Port Robotic System in the Treatment of Laryngo-Pharyngeal Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 26, 4472–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plonowska, K.A.; Ochoa, E.; Zebolsky, A.L.; Patel, N.; Hoppe, K.R.; Ha, P.K.; Heaton, C.M.; Ryan, W.R. Nasogastric Tube Feeding after Transoral Robotic Surgery for Oropharynx Carcinoma. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, P.; Kinnunen, I.; Jouhi, L.; Vahlberg, T.; Back, L.J.J.; Halme, E.; Koivunen, P.; Autio, T.; Pukkila, M.; Irjala, H. Long-term Quality of Life After Treatment of Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E1172–E1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubek, N.; Channir, H.I.; Charabi, B.W.; Lajer, C.B.; Kiss, K.; Nielsen, H.U.; Bentzen, J.; Friborg, J.; von Buchwald, C. Primary Transoral Robotic Surgery with Concurrent Neck Dissection for Early Stage Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Implemented at a Danish Head And Neck Cancer Center: A Phase II Trial on Feasibility and tumour Margin Status. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2017, 274, 2229–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.I.; Madsen, A.K.; Rubek, N.; Kehlet, H.; von Buchwald, C. Days Alive and out of Hospital after Treatment for Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma with Primary Transoral Robotic Surgery or Radiotherapy—A Prospective Cohort Study. Acta Oto-Laryngol. 2020, 141, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.I.; Madsen, A.K.O.; Rubek, N.; Charabi, B.W.; Wessel, I.; Hadju, S.F.; Jensen, C.V.; Stephen, S.; Patterson, J.M.; Friborg, J.; et al. Long-Term Quality of Life & Functional Outcomes after Treatment of Oropharyngeal Cancer. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethia, R.; Yumusakhuylu, A.C.; Ozbay, I.; Diavolitsis, V.; Brown, N.V.; Zhao, S.; Wei, L.; Old, M.; Agrawal, A.; Teknos, T.N.; et al. Quality of Life Outcomes of Transoral Robotic Surgery with or without Adjuvant Therapy for Oropharyngeal Cancer. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Patel, S.; Baik, F.M.; Mathison, G.; Pierce, B.H.G.; Khariwala, S.S.; Yueh, B.; Schwartz, S.M.; Méndez, E. Survival and Gastrostomy Prevalence in Patients With Oropharyngeal Cancer Treated With Transoral Robotic Surgery vs Chemoradiotherapy. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 142, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, J.R.; Van Abel, K.; Martin, E.J.; Lohse, C.M.; Price, D.L.; Olsen, K.D.; Moore, E.J. Management of Recurrent and Metastatic HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma after Transoral Robotic Surgery. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2017, 157, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Song, S. Clinical Outcomes Following Observation, Post-Operative Radiation Therapy, or Post-Operative Chemoradiation for HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2023, 146, 106493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, P.; Kallogjeri, D.; Gay, H.; Thorstad, W.L.; Lewis, J.S.; Chernock, R.; Nussenbaum, B.; Haughey, B.H. High Metastatic Node Number, Not Extracapsular Spread or N-Classification is a Node-Related Prognosticator in transorally-Resected, Neck-Dissected p16-Positive Oropharynx Cancer. Oral Oncol. 2015, 51, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, E.M.; Plonowska-Hirschfeld, K.; Gulati, A.; Kansara, S.; Qualliotine, J.; Zelbolsky, A.L.; van Zante, A.; Ha, P.K.; Heaton, C.M.; Ryan, W.R. Prospective Quality of Life Outcomes For Human Papillomavirus Associated Oropharynx Cancer Patients after Surgery Alone. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2023, 44, 103915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Shimunov, D.; Tan, E.X.; Swisher-Mcclure, S.; Lin, A.; Lukens, J.N.; Basu, D.; Chalian, A.A.; Cannady, S.B.; Newman, J.G.; et al. Survival and Toxicity in Patients with Human Papilloma Virus-Associated Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Cancer Receiving Trimodality Therapy Including Transoral Robotic Surgery. Head Neck 2021, 43, 3053–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swisher-McClure, S.; Lukens, J.N.; Aggarwal, C.; Ahn, P.; Basu, D.; Bauml, J.M.; Brody, R.; Chalian, A.; Cohen, R.B.; Fotouhi-Ghiam, A.; et al. A Phase 2 Trial of Alternative Volumes of Oropharyngeal Irradiation for De-intensification (AVOID): Omission of the Resected Primary Tumor Bed After Transoral Robotic Surgery for Human Papilloma Virus-Related Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oropharynx. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 106, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Abel, K.M.; Quick, M.H.; Graner, D.E.; Lohse, C.M.; Price, D.L.; Price, K.A.; Ma, D.J.; Moore, E.J. Outcomes Following TORS for HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Carcinoma: PEGs, Tracheostomies, and Beyond. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2019, 40, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Abel, K.M.; Yin, L.X.; Price, D.L.; Janus, J.R.; Kasperbauer, J.L.; Moore, E.J. One-Year Outcomes For Da Vinci Single Port Robot for Transoral Robotic Surgery. Head Neck 2020, 42, 2077–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Loon, J.W.L.; Smeele, L.E.; Hilgers, F.J.M.; Brekel, M.W.M.v.D. Outcome of Transoral Robotic Surgery for Stage I–II Oropharyngeal Cancer. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2015, 272, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waltonen, J.D.; Thomas, S.G.; Russell, G.B.; Sullivan, C.A. Oropharyngeal Carcinoma Treated with Surgery Alone: Outcomes and Predictors of Failure. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2022, 131, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, C.M.; Lee, D.Y.; Shimunov, D.; Carmona, R.; Barsky, A.R.; Sun, L.; Cohen, R.B.; Bauml, J.M.; Brody, R.M.; Basu, D.; et al. Definitive Tumor Directed Therapy Confers a Survival Advantage for Metachronous Oligometastatic HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer Following Trans-Oral Robotic Surgery. Oral Oncol. 2021, 121, 105509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.J.; Plonowska, K.A.; Gurman, Z.R.; Humphrey, A.K.; Ha, P.K.; Wang, S.J.; El-Sayed, I.H.; Heaton, C.M.; George, J.R.; Yom, S.S.; et al. Treatment Modality Impact on Quality of Life for Human Papillomavirus–Associated Oropharynx Cancer. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, E48–E56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Shan, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H. Factors Associated with the Quality of Life for Hospitalized Patients with HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2020, 103, 104590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebolsky, A.L.; George, E.; Gulati, A.; Wai, K.C.; Carpenter, P.; Van Zante, A.; Ha, P.K.; Heaton, C.M.; Ryan, W.R. Risk of Pathologic Extranodal Extension and Other Adverse Features After Transoral Robotic Surgery in Patients With HPV-Positive Oropharynx Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 147, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, F.; McMahon, J.; Afzali, P.; Cuschieri, K.; Yan, Y.S.; Schipani, S.; Brands, M.; Ansell, M. Staging and Treatment Outcomes in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Single-Centre UK Cohort. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhry, C.; Lacchetti, C.; Rooper, L.M.; Jordan, R.C.; Rischin, D.; Sturgis, E.M.; Bell, D.; Lingen, M.W.; Harichand-Herdt, S.; Thibo, J.; et al. Human Papillomavirus Testing in Head and Neck Carcinomas: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement of the College of American Pathologists Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 3152–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, B.; Huang, S.H.; Su, J.; Garden, A.S.; Sturgis, E.M.; Dahlstrom, K.; Lee, N.; Riaz, N.; Pei, X.; A Koyfman, S.; et al. Development and validation of a staging system for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer by the International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal cancer Network for Staging (ICON-S): A multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, H.; Taberna, M.; von Buchwald, C.; Tous, S.; Brooks, J.; Mena, M.; Morey, F.; Grønhøj, C.; Rasmussen, J.H.; Garset-Zamani, M.; et al. Prognostic implications of p16 and HPV discordance in oropharyngeal cancer (HNCIG-EPIC-OPC): A multicentre, multinational, individual patient data analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschuymer, S.; Dok, R.; Laenen, A.; Hauben, E.; Nuyts, S. Patient Selection in Human Papillomavirus Related Oropharyngeal Cancer: The Added Value of Prognostic Models in the New TNM 8th Edition Era. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rietbergen, M.M.; Witte, B.I.; Velazquez, E.R.; Snijders, P.J.F.; Bloemena, E.; Speel, E.J.; Brakenhoff, R.H.; Kremer, B.; Lambin, P.; Leemans, C.R. Different prognostic models for different patient populations: Validation of a new prognostic model for patients with oropharyngeal cancer in Western Europe. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 1733–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassen, P.; Huang, S.H.; Su, J.; O’Sullivan, B.; Waldron, J.; Andersen, M.; Primdahl, H.; Johansen, J.; Kristensen, C.; Andersen, E.; et al. Impact of tobacco smoking on radiotherapy outcomes in 1875 HPV-positive oropharynx cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, C.M.; Grau, C.; Overgaard, J. Effect of smoking on oxygen delivery and outcome in patients treated with radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma—A prospective study. Radiother. Oncol. 2012, 103, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden, D.F.; Hobelmann, K.; Vimawala, S.; Richa, T.; Fundakowski, C.E.; Goldman, R.; Luginbuhl, A.; Curry, J.M.; Cognetti, D.M. Evaluating the impact of smoking on disease-specific survival outcomes in patients with human papillomavirus–associated oropharyngeal cancer treated with transoral robotic surgery. Cancer 2020, 126, 1873–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.Y.; Sherman, E.J.; Schöder, H.; Wray, R.; Boyle, J.O.; Singh, B.; Grkovski, M.; Paudyal, R.; Cunningham, L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Hypoxia-Directed Treatment of Human Papillomavirus–Related Oropharyngeal Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Kotecha, J.; Acharya, A.; Garas, G.; Darzi, A.; Davies, D.C.; Tolley, N. Determination of biometric measures to evaluate patient suitability for transoral robotic surgery. Head Neck 2015, 37, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luginbuhl, A.; Baker, A.; Curry, J.; Drejet, S.; Miller, M.; Cognetti, D. Preoperative cephalometric analysis to predict transoral robotic surgery exposure. J. Robot. Surg. 2014, 8, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weinstein, G.S.; O’malley, B.W.; Rinaldo, A.; Silver, C.E.; Werner, J.A.; Ferlito, A. Understanding contraindications for transoral robotic surgery (TORS) for oropharyngeal cancer. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2014, 272, 1551–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, J.T.; Milov, S.; Lewis, J.S., Jr.; Thorstad, W.L.; Adkins, D.R.; Haughey, B.H. Transoral laser microsurgery (TLM)±adjuvant therapy for advanced stage oropharyngeal cancer: Outcomes and prognostic factors. Laryngoscope 2009, 119, 1709–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.; Ford, S.; Bush, B.; Holsinger, F.C.; Moore, E.; Ghanem, T.; Carroll, W.; Rosenthal, E.; Sweeny, L.; Magnuson, J.S. Salvage Surgery for Recurrent Cancers of the Oropharynx: Comparing TORS with Standard Open Surgical Approaches. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013, 139, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.J.; Price, K.A.; Moore, E.J.; Patel, S.H.; Hinni, M.L.; Garcia, J.J.; Graner, D.E.; Foster, N.R.; Ginos, B.; Neben-Wittich, M.; et al. Phase II Evaluation of Aggressive Dose De-Escalation for Adjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Human Papillomavirus–Associated Oropharynx Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, R.L.; Flamand, Y.; Weinstein, G.S.; Li, S.; Quon, H.; Mehra, R.; Garcia, J.J.; Chung, C.H.; Gillison, M.L.; Duvvuri, U.; et al. Phase II Randomized Trial of Transoral Surgery and Low-Dose Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy in Resectable p16+ Locally Advanced Oropharynx Cancer: An ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group Trial (E3311). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, B.A.; Posner, M.R.; Gupta, V.; Teng, M.S.; Bakst, R.L.; Yao, M.; Misiukiewicz, K.J.; Chai, R.L.; Sharma, S.; Westra, W.H.; et al. De-Escalated Adjuvant Therapy After Transoral Robotic Surgery for Human Papillomavirus-Related Oropharyngeal Carcinoma: The Sinai Robotic Surgery (SIRS) Trial. Oncologist 2021, 26, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owadally, W.; Hurt, C.; Timmins, H.; Parsons, E.; Townsend, S.; Patterson, J.; Hutcheson, K.; Powell, N.; Beasley, M.; Palaniappan, N.; et al. PATHOS: A Phase II/III Trial of Risk-Stratified, Reduced Intensity Adjuvant Treatment in Patients Undergoing Transoral Surgery for Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strohl, M.P.; Wai, K.C.; Ha, P.K. De-Intensification Strategies in HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma–A Narrative Review. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yom, S.S.; Clair, J.M.-S.; Ha, P.K. Controversies in Postoperative Irradiation of Oropharyngeal Cancer After Transoral Surgery. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 26, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN Guidelines for Head and Neck Cancers V.1.2023. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Machiels, J.-P.; Leemans, C.R.; Golusinski, W.; Grau, C.; Licitra, L.; Gregoire, V. Reprint of “Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, larynx, oropharynx and hypopharynx: EHNS-ESMO-ESTRO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up”. Oral Oncol. 2021, 113, 105042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molony, P.; Kharytaniuk, N.; Boyle, S.; Woods, R.S.R.; O’Leary, G.; Werner, R.; Heffron, C.; Feeley, L.; Sheahan, P. Impact of positive margins on outcomes of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma according to p16 status. Head Neck 2017, 39, 1680–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, P.; Patrik, P.; Thorstad, W.L.; Gay, H.A.; Haughey, B.H. Does elimination of planned postoperative radiation to the primary bed in p16-positive, transorally-resected oropharyngeal carcinoma associate with poorer outcomes? Oral Oncol. 2016, 61, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, J.L.; Ku, J.A. Postoperative Treatment of Oropharyngeal Cancer in the Era of Human Papillomavirus. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2019, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlandi, E.; Iacovelli, N.A.; Cavallo, A.; Resteghini, C.; Gandola, L.; Licitra, L.; Bossi, P. Could the extreme conformality achieved with proton therapy in paranasal sinuses cancers accidentally results in a high rate of leptomeningeal progression? Head Neck 2019, 41, 3733–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.N.; Moore, E.J.; Rosenthal, E.L.; Carroll, W.R.; Olsen, K.D.; Desmond, R.A.; Magnuson, J.S. Transoral Robotic-Assisted Surgery for Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: One-and 2-Year Survival Analysis. Arch. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2010, 136, 1248–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zenga, J.; Wilson, M.; Adkins, D.R.; Gay, H.A.; Haughey, B.H.; Kallogjeri, D.; Michel, L.S.; Paniello, R.C.; Rich, J.T.; Thorstad, W.L.; et al. Treatment Outcomes for T4 Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2015, 141, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.A.; Weinstein, G.S.; O’Malley, B.W.; Feldman, M.; Quon, H. Transoral robotic surgery and human papillomavirus status: Oncologic results. Head Neck 2010, 33, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kejner, A.; Gentile, C.; Porterfield, Z.; Carroll, W.R.; Buczek, E.P. Positive Deep Initial Incision Margin Affects Outcomes in TORS for HPV plus Oropharynx Cancer. Laryngoscope 2023, 133, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtuk, A.; Agrawal, A.; Old, M.; Teknos, T.N.; Ozer, E. Outcomes of Transoral Robotic Surgery: A Preliminary Clinical Experience. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 145, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukens, J.N.; Lin, A.; Gamerman, V.; Mitra, N.; Grover, S.; McMenamin, E.M.; Weinstein, G.S.; O’Malley, B.W.; Cohen, R.B.; Orisamolu, A.; et al. Late consequential surgical bed soft tissue necrosis in advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas treated with transoral robotic surgery and postoperative radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2014, 89, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, N.; Mascarella, M.A.; Khalife, S.; Ramanakumar, A.V.; Richardson, K.; Joshi, A.S.; Taheri, R.; Fuson, A.; Bouganim, N.; Siegel, R. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery for HPV-associated locoregionally advanced oropharynx cancer. Head Neck 2020, 42, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, N.; Khalife, S.; Mascarella, M.A.; Ramanakumar, A.V.; Richardson, K.; Joshi, A.S.; Bouganim, N.; Taheri, R.; Fuson, A.; Siegel, R. Pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in HPV-associated oropharynx cancer. Head Neck 2019, 42, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Virgilio, A.; Costantino, A.; Festa, B.M.; Sampieri, C.; Spriano, G.; Kim, S.-H. Compartmental Transoral Robotic Lateral Oropharyngectomy with the da Vinci Single-Port System: Surgical Technique. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 30, 5728–5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).