Abstract

Objective: To systematically review the clinicopathological features of oral warty keratoma based on published literature. Materials and Methods: PubMed and Scopus databases were searched for reports of oral warty dyskeratoma. Of the 52 identified articles, only 25 articles (43 cases) satisfied the selection criteria (case report/series in the English language reporting clinicopathologically diagnosed oral warty dyskeratoma/oral focal acantholytic keratosis/oral isolated dyskeratosis follicularis in humans). Risk of bias was assessed using the Joanna Briggs institute critical appraisal checklist for case reports and case series. Results: Most cases had well-circumscribed, white, nodular verruco-papillary lesions with a central depressed/crater-like area. Alveolar ridges were the most frequent sites of occurrence and tobacco was the most commonly associated risk factor. Histopathologically, the most pathognomonic feature was the supra-basal clefting. The cleft had dyskeratotic acantholytic cells (corps ronds, and grains). Below the cleft were projections of the connective tissue villi lined by basal cells. The basal cells in a few cases exhibited hyperplasia in the form of budding into the stroma, but epithelial dysplasia was not reported. The surface epithelium had crypts filled with keratin debris. Conclusion: Oral warty dyskeratoma is a rare solitary self-limiting benign entity, which due to its clinical and histopathological resemblance and associated habit history could be misdiagnosed as leukoplakia or carcinoma. None of the assessed articles provided molecular data, which in turn could be the reason for the lack of insight into the etiopathogenesis of this enigmatic lesion.

1. Introduction

Warty dyskeratoma represents a benign solitary tumor of the skin, vulva, and oral cavity []. The cause of oral warty dyskeratoma (OWK) is yet to be determined, although most cases have shown an association with tobacco smoking/chewing, local chronic trauma/irritation from a sharp tooth, or an ill-fitting denture []. Clinically, the lesion is largely asymptomatic, thus most cases are diagnosed during a routine oral examination. Based on the clinical appearance OWK could be classified as a verruco-papillary lesion []. The shape of the lesion is often nodular and well-circumscribed. Few cases have also shown a relatively smooth surface in the form of a papule, or a patch [,,,]. The color of the lesion is white, which is attributed to the hyper-keratinized state of the surface epithelium. The white color and the associated tobacco habits often lead to a provisional diagnosis of leukoplakia in case of white patch, verrucous carcinoma/verrucous hyperplasia in case of a verrucous surface, or oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). An additional characteristic feature is the central depressed area of the lesion. The depressed area is often described as an ulcer, a crater, or a crypt. On palpation, the lesion appears firm which in turn is attributed to the keratin debris in these crypt/craters-like depressions of the surface epithelium. The ulcerated appearance in the background of a white verrucous/patch like lesion, often in combination with tobacco leads to a provisional diagnosis of OSCC presenting as a ulceroproliferative growth. The ulceration in the presence of a sharp cusp or an ill-fitting denture often results in a provisional diagnosis of a chronic ulcer. Histopathologically, the term focal acantholytic dyskeratosis (FAD) precisely describes OWK [,]. FAD presents as focal epithelial acantholysis with the acantholytic cells exhibiting varying degrees of dyskeratosis, which are often categorized as corps ronds and grains. OWK represents a small (less than 1 cm), solitary well-circumscribed lesion in the oral mucosa with histopathological features of FAD. The presence of multiple lesions, including cutaneous involvement, should prompt the consideration of Darriers disease []. Our objective is to systematically review the literature for the clinicopathological characteristics, treatment, and prognosis of OWK.

2. Materials and Methods

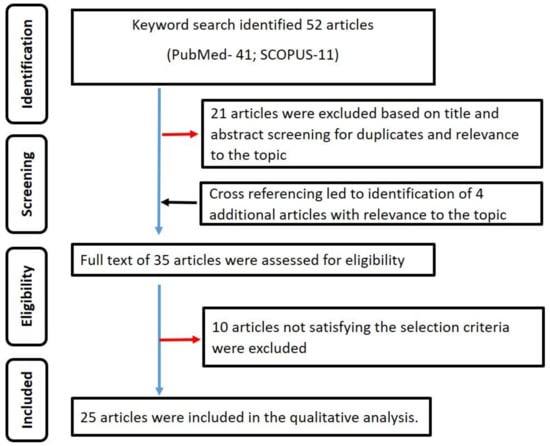

The International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) was searched for systematic reviews on oral warty dyskeratoma. There were none. Thus, the present review was registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42020213865). PRISMA guidelines [,] were strictly adhered to in the qualitative analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of the search strategy employed in the qualitative analysis.

The systematic review was conducted in three steps:

(1) PubMed and Scopus databases were searched using the keywords ‘oral warty keratoma; oral focal acantholytic keratosis; oral isolated dyskeratosis follicularis’. The search was done in May 2021.

(2) The identified articles were screened for potential duplicates and relevance to the topic using their titles and abstracts.

(3) The full text of the articles selected from screening was assessed using the following selection criteria:

Inclusion criteria: Case report/series in the English language reporting OWK/oral focal acantholytic keratosis/oral isolated dyskeratosis follicularis in humans. The diagnosis must have been determined using both clinical and histopathological examinations.

Exclusion criteria: Cases wherein the diagnosis lacked clinical and/or histopathological examination.

The publications satisfying the above criteria were included in the qualitative analysis. Data including the number of cases, clinical and histopathological features, the treatment rendered, and the follow-up data were extracted. Step 2 and 3 of the review were conducted by two reviewers (KHA and ATR). The inter-observer reliability in steps 2 and 3 was determined by assessing the kappa coefficient (κ).

Risk of bias assessment: The Joanna Briggs institute critical appraisal checklist for case reports and case series [] was applied. The risk of bias was categorized as high when the study attained up to 49% score yes, moderate when the study attained 50 to 69% score, yes, and low when the study attained more than 70% score yes.

3. Results

A total of 52 published studies were identified. Title and abstract screening led to the exclusion of 21 articles. The remaining 31 articles were manually cross-referenced to identify further potential articles. The cross-referencing led to the identification of four articles whose titles and abstracts were relevant to the topic of interest. Based on the full-text assessment of the (31 + 4) 35 articles, only 25 articles [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,] satisfied the selection criteria and were included in the systematic review. Figure 1 summarizes the search strategy used in the present review. The κ values for steps 2 and 3 of the review were 0.96 and 0.98, indicating good inter-observer reliability. Table 1 summarizes the data extracted from the included studies. A total of 43 cases were retrieved from the 25 articles [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,] included in the qualitative analysis.

Table 1.

Summary of the data extracted from the included studies.

Study characteristics: US reported the highest number of cases (34 cases) [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,], followed by UK (three cases) [,,], Korea (two cases) [,], Australia (two cases) [], Greece (one case) [], and Israel (one case) [].

Site of occurrence: The most common sites of occurrence were the masticatory mucosa including the alveolar ridge mucosa (11 cases) [,,,,,,], gingiva (eight cases) [,,,,], hard palate (seven cases) [,,,,], palatal mucosa (three cases) [,,] followed by the lining mucosa including buccal mucosa (four cases) [,,,], soft palate (three cases) [,], lower lip (three cases) [,], upper lip (two cases) [,], soft palate-hard palate junction (one case) [], lateral border of the tongue (one case) [] and the floor of the mouth (one case) [].

Presence of potential risk factors: The most common associated risk factor was the habits including consumption of tobacco and alcohol. A total of 13 cases used tobacco [,,,,,,,], one case consumed both tobacco and alcohol []. Few cases had a combination of several risk factors, such as tobacco, alcohol consumption with cheek biting in one case []; ill-fitting denture, and tobacco usage in one case []. Less frequent risk factors included maxillary and mandibular denture (one case) [], sharp tooth (one case) [], and snuff dipping (one case) [].

Size of the lesion: The lesion size ranged from 2 mm to 3 cm. The lesion was less than 1 cm in most (n = 22) of the cases.

Age and gender distribution of the patients: The age ranged from 33 to 81 years, with an average age of 55.7 years. Most (n = 32) of the patients were above 50 years old. Males (n = 26) were affected more often than females (n = 15). In two cases the gender of the patient was not mentioned.

Symptoms: A majority of cases did not report any symptoms from the oral lesion. Only five cases had symptoms including pain (one case) [], mild tenderness (one case) [], and soreness (two cases) [,].

Duration of lesion: Only 11 studies provided the duration of the lesion, of which seven studies reported less than 1 year. The shortest duration was 2 weeks [], and the longest duration was 20 years [].

Clinical diagnosis: The proximity to a sharp tooth led to the provisional diagnosis of a chronic ulcer []. The verrucous/pebbly appearance and firm consistency in palpation led to the provisional diagnosis of papilloma [,,]. The excess keratin deposition gave the lesion a white appearance, which in turn was often diagnosed clinically as hyperkeratosis [,,]. The white colour of a patch-like lesion along with an associated habit history led to the provisional diagnosis of leukoplakia []. A verrucous, or ulcerated lesion with an associated habit history led to the provisional diagnosis of OSCC [,]. One case each was diagnosed as stomatitis nicotine [], burnt palate associated with slow-healing ulcer [], fibroma [], basal cell carcinoma [], and actinic keratosis [].

Associated lesion: One case had a history of a warty lesion on the skin of the left cheek []. One case had a history of OSCC, which led to mandibulectomy, followed by reconstruction of the resected mandible with a mucocutaneous flap and reconstruction plate []. The OWK occurred on the lateral margins of the myocutaneous flap. In one case, there was a co-existing OSCC and epidermolytic hyperkeratosis []. In one case, a root stump with discharging sinus was removed following which the sinus was replaced by the warty dyskeratoma []. One case had a co-existing smoker’s keratosis []. One case had co-existing mucocele with sialadenitis in the lower lip []. One case had a co-existing verrucous xanthoma, which was diagnosed during the histopathological examination [].

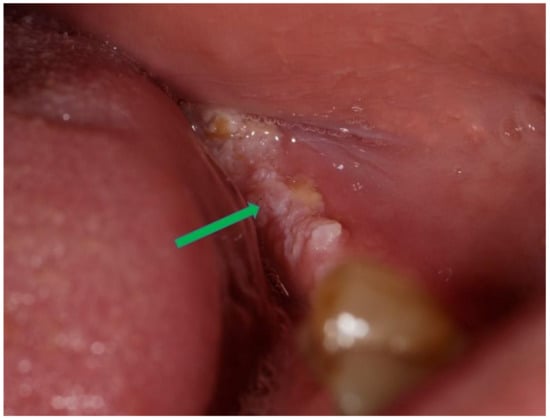

Clinical presentation: The majority of the OWK had a central depressed area which was described as ulceration, sinus opening, depressed umbilicated centre, crater, cavitation. In a few cases, the central area was described as fissures [], and fistula [] was used. The lesioned surface in most cases was verrucous/warty/pebbly (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Oral warty dyskeratoma exhibiting a verrucous/warty/pebbly surface (blue arrow).

The lesion was described as nodular to papular. The prominence of keratinization in the lesions could be evidenced by the clinical description of the lesion as a white raised lesion with a central depressed area where keratin debris could be picked off []. The lesion was well-circumscribed in most cases. Two cases had a white stria radiating from the central portion of the lesion [,]. The crusted appearance was also described in a few cases involving the lip [,].

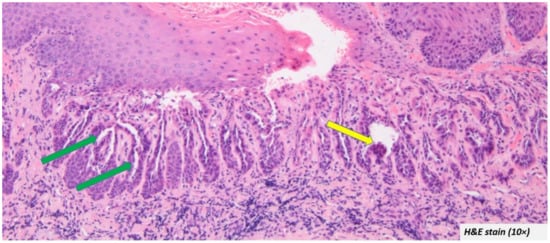

Histopathological presentation: The microscopic descriptions were largely uniform. The most common and characteristic feature was the intra epithelial clefting (Figure 3—green arrow). The cleft was in most cases noted in the supra-basal region. The bottom of the cleft had connective tissue villi projections lined by a single row of basal cells which in some cases exhibited hyperplasia without atypia (Figure 3—yellow arrow).

Figure 3.

Most oral warty dyskeratoma cases included in the systematic review showed intra epithelial clefting at the supra-basal region (green arrow) and the cleft was lined by hyperplastic basal cells (yellow arrow).

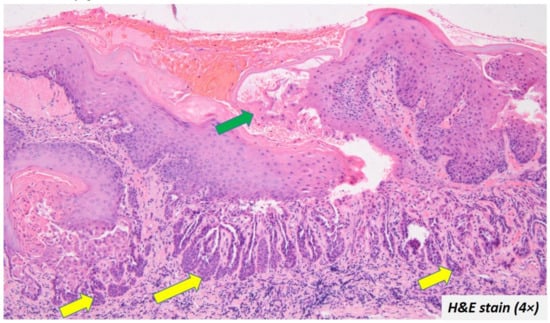

The upper portion of the cleft had the spinous layer and stratum granulosum. Acanthosis was evident in some cases. The granulosum layer was prominent with large keratohyalin granules in some cases. The cleft itself contained acantholytic cells which had a varying degree of dyskeratosis. The characteristic corps ronds and grains were also described in a few cases [,,,,,,,,,,,]. The surface epithelium showed a cup-shaped depression corresponding to the areas clinically described as ulceration, sinus opening, depressed umbilicated centre, crater, and cavitation. The depressed epithelium contained ortho/parakeratin debris (Figure 4—green arrow). The pseudo-epithelial proliferation was evident in a few cases (Figure 4—yellow arrow), which had often led to the misdiagnosis of OSCC. Despite a few atypical features, the cases did not report any epithelial dysplasia.

Figure 4.

Ortho/parakeratin debris filled the depressed epithelium (green arrow) and some cases also exhibited pseudo-epithelial proliferation (yellow arrow).

Additional investigations: Feulgen-Schiff stain and electron microscopy examination [,] did not reveal any viral, parasitic, or bacterial inclusions. Immunofluorescence showed basement membrane positivity for complement 3, albumin, and fibrinogen [].

Diagnosis: All the included cases were diagnosed as warty dyskeratoma/focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. Incisional biopsy of two cases was misdiagnosed as OSCC due to the pseudo-epithelial proliferation and dyskeratosis []. In those cases, the excisional biopsy revealed the characteristic features of FAD including the suprabasal clefting, keratin-filled debris in the crater of the surface epithelium, corp ronds, grains, and the lack of epithelial dysplasia.

Treatment: Excisional biopsy was the most common treatment strategy employed. In one case, an incisional biopsy was performed. Since the biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of warty dyskeratoma, the rest of the lesion was left untreated [].

Follow up: Only nine articles provided the follow-up period, which ranged from 5 months to 14 years. No recurrence was noted in any of the reported cases.

Risk of bias assessment: Among 20 included case reports, only four case reports [,,,] provided the follow-up details. Additionally, one case report did not provide the clinical details []. Among the 5-case series, none provided any clear data on the consecutive or the complete inclusion of participants. Two case series [,] did not provide the follow-up details. Despite the above-mentioned limitations, the Joanna Briggs institute critical appraisal checklist showed that all the included case reports and series had only a low risk of bias. Table 2 and Table 3 summarize the Joanna Briggs institute critical appraisal checklist for case reports and case series, respectively.

Table 2.

Risk of bias evaluation of the included studies- The Joanna Briggs institute critical appraisal checklist for case reports.

Table 3.

Risk of bias evaluation of the included studies - The Joanna Briggs institute critical appraisal checklist for case series.

4. Discussion

Warty Dyskeratoma was first reported in 1957 on the skin []. The first report of an OWK was issued 10 years later by Gorlin et al. []. OWK is a relatively less explored entity, which in turn could be largely attributed to its rare occurrence and benign self-limiting nature. Although it is a small non-progressive lesion, its clinical and histopathological resemblance to oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs) and OSCC often mandates additional investigation. In addition to its close appearance to a malignant entity, OWK has also been associated with major risk factors for malignancy including tobacco and alcohol [,,,,,,,]. Thus, it is necessary to understand the natural history of this enigmatic solitary lesion of the oral cavity. The present systematic review is largely based on individual case reports/case series with only one extensive published case series reporting 15 cases []. Given the rarity of the lesion, at present, no original studies exist analysing the varying aspects of OWK. Very few additional investigations (ultramicroscopic and immunofluorescence) are reported in the case reports/series [,,]. Thus, the present systematic review is focussed largely on analysing the various clinical and histopathological features of OWK.

All the cases reported in the review were solitary. The importance of a solitary presentation lies in the close resemblance of OWK with Darriers disease, even entailing the designation of ‘pseudo-darriers disease’. Thus, in cases where the OWK-like lesions are multiple as in the present cases, Darriers disease must be considered as a potential diagnosis. OWK can be distinguished from Darriers disease by the absence of germline mutations in ATP2A2 (the gene responsible for Darier disease) and the absence of SERCA2 protein. [,].

As the term warty indicates, the lesion has a verruco-papillary surface in most cases. Thus, the clinical differential diagnosis often includes verrucous hyperplasia (VH), verrucous carcinoma (VC), and papillary OSCC []. Unlike VC, VH, and OSCC, the OWK is self-limiting with no potential for malignant transformation. In such cases, the difference in the size could be a major indicator of the nature of the lesion. Most cases of OWK are less than 1 cm, which is contrary to the progressive nature of VC, VH, and OSCC. Additionally, the OWK is well-circumscribed, which is not the case in locally invasive lesions including VC, VH, and OSCC []. In addition to the larger verrucous lesions, several virus-associated oral lesions are less than 1 cm in dimension. An example of such a lesion is squamous papilloma. In such cases, the presence of the viral particles in the squamous papilloma lesion would be a distinguishing factor []. Electron microscopic studies have confirmed the absence of viral particles in OWK, although the data are based on only two included studies [,]. Warty dyskeratoma from extra-oral sites has also been shown to be negative for viral (human papillomavirus) DNA []. Thus, although similar in presentation to most virus-induced papillary lesions, OWK may not have a viral etiology.

As OWK is considered to be a result of abnormal keratinization, all the cases presented as white lesions representing excess keratin production. Most cases present as a nodule, although a few cases of patch-like or papular lesions are also reported. A white patch-like lesion is often provisionally diagnosed as leukoplakia [], especially with an associated tobacco history. In such cases, the absence of epithelial dysplasia, presence of suprabasal clefting, keratin-filled crypts, and the acantholytic dyskeratotic cells (corps ronds, grains) would be the distinguishing features from true tobacco-induced potentially malignant leukoplakic lesions. Few cases have presented data on consistency as ‘firm’ based on palpation []. The firmness can be attributed to the collection of keratin debris in the crypts of the surface epithelium. The most characteristic clinical feature of an OWK was the central areas described as depressed, crater-like, and umbilicated. This area is often filled with varying degrees of keratin debris imparting the white colour and firm consistency.

Microscopic examination reveals a series of depression and elevations in the surface epithelium which are consistent with the verruco-papillary surface of the lesion. The depression is filled with keratin debris, although overall the entire affected surface epithelium has a varying degree of hyper-ortho/parakeratosis. The characteristic histopathological feature of OWK is the cleft noted in the suprabasal region of the epithelium. The cleft is bound on its lower part by a series of projections created by connective tissue villi, which are in turn lined by a single row of basal cells. These basal cells exhibit varying degrees of hyperplasia, although atypia is not reported. The basal cell hyperplasia often leads to budding into the underlying stroma causing the appearance of pseudo-epithelial hyperplasia, which along with dyskeratosis can be misdiagnosed as OSCC []. In such cases, the absence of epithelial dysplasia and the presence of characteristic suprabasal clefting and keratin-filled crypts would aid in the diagnosis of focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. Within the suprabasal cleft are the dyskeratotic acantholytic cells (corps ronds and grains) [,,,,,,,,,,]. Above the cleft are the thickened layer of spinosum (acanthosis) [,,,,,,] and granulosum [,,,].

Although the lesions are relatively small, given their close resemblance to OPMDs and OSCC and the associated tobacco history, most cases were excised completely. None of the cases included in the present review showed any signs of recurrence or malignant transformation.

5. Conclusions

OWK is a rare benign solitary well-circumscribed, white verruco-papillary lesion involving the keratinized mucosa. The most characteristic clinical feature was the central depression/crater/umbilicated centre. Histopathologically, an OWK can be precisely described as a focal acantholytic dyskeratosis with varying degrees of dyskeratosis. The most characteristic histopathological feature was the supra-basal clefting, keratin-filled crypts, corps ronds, and grains. Their close resemblance to OPMDs and OSCC and the presence of associated tobacco habits mandates a histopathological confirmation of the true nature of the lesion. To date, there is no evidence of recurrence or malignant transformation in an OWK. Thus, despite its likeness to OPMDs and OSCC, an OWK is a benign self-limiting entity that, apart from a histopathological confirmation, requires no therapeutic interventions.

- OWK is a benign lesion with clinicopathological resemblance to OPMD and OSCC

- Common clinical feature includes central depression/crater/umbilicated centre

- Common histopathological features include supra-basal clefting, keratin-filled crypts, corps ronds, and grains

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.H.A., A.T.R. and S.P.; methodology, P.M. and S.W.; software, P.M.; validation, S.W., A.T.R. and K.H.A.; formal analysis, S.W.; investigation, P.M.; resources, A.T.R.; data curation, A.T.R. and K.H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T.R. and K.H.A.; writing—review and editing, P.M., S.W. and S.P. visualization, S.W.; supervision, A.T.R.; project administration, K.H.A. and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Peters, S.M.; Roll, K.S.; Philipone, E.M.; Yoon, A.J. Oral warty dyskeratoma of the retromolar trigone: An unusual presentation of a rare lesion. JAAD Case Reports 2017, 3, 336–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Allon, I.; Buchner, A. Warty dyskeratoma/focal acantholytic dyskeratosis - An update on a rare oral lesion. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2012, 41, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallarakkal, T.G.; Ramanathan, A.; Zain, R.B. Verrucous Papillary Lesions: Dilemmas in Diagnosis and Terminology. Int. J. Dent. 2013, 2013, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyfe, E.C.; Guest, P.G.; St. Rose, L.; Eveson, J.W. Focal acantholytic dyskeratosis arising in an intraoral skin flap. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2002, 31, 560–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrist, T.J. Oral Warty Dyskeratoma. Arch. Dermatol. 1980, 116, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Altman, D.G.; Booth, A.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (prisma-p) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for Use in JBI Systematic Reviews Checklist for Prevalence Studies. Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2020-08/Checklist_for_Prevalence_Studies.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Gorlin, R.J. Warty dyskeratoma. A note concerning its occurrence on the oral mucosa. Arch. Dermatol. 1967, 95, 292–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixey, R.J.; Fay, J.T. Oral warty dyskeratoma: Literature review and report of case. J. Oral Surg. 1981, 39, 378–380. [Google Scholar]

- Giunta, J.L.; Gomez, L.S.A.; Greer, R.O. Oral focal acantholytic dyskeratosis (warty dyskeratoma): Report of two cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1975, 39, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danforth, R.A.; Green, T.L. Oral warty dyskeratoma. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1980, 49, 523–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, P.D.; Lumerman, H.; Kerpel, S.M. Oral focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1981, 52, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, M.L.; Lambert, W.C.; Schneider, L.C.; Reibel, J. Oral warty dyskeratoma. Cutis 1984, 33, 293.e4–296.e4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, B.M.; Nickoloff, B.J. Solitary labial papular acantholytic dyskeratoma in an immunocompromised host. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 1987, 9, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.C.; Lew, W. A case of focal acantholytic dyskeratosis occurring on both the lip and the anal canal. Yonsei Med. J. 2003, 44, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.K.; Chang, S.N.; Lee, S.H. Focal acantholytic dyskeratosis on the lip. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 1995, 17, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leider, A.S.; Eversole, L.R. Focal acantholytic dyskeratosis of the oral mucosa. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1984, 58, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, J.C.; Dutton, A.R.; Triantafyllou, A.; Rajlawat, B.P. Warty dyskeratoma of the buccal mucosa. Oral Surg. 2014, 7, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, M.K.; Moss, N. Warty dyskeratoma. A note concerning its occurrence on the oral mucosa, and its possible pathogenesis. Br. J. Oral Surg. 1979, 17, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaugars, G.E.; Lieb, R.J.; Abbey, L.M. Focal Oral Warty Dyskeratoma. Int. J. Dermatol. 1984, 23, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunt, S.L.; Tomich, C.E. Oral focal acantholytic dyskeratosis. J. Dermatol. Surg. Oncol. 1990, 16, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomich, C.E.; Burkes, E.J. Warty dyskeratoma (isolated dyskeratosis follicularis) of the oral mucosa. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1971, 31, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newland, J.R.; Leventon, G.S. Warty dyskeratoma of the oral mucosa- Correlated light and electron microscopic study. Oral Surg. 1984, 58, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patibanda, R. Warty dyskeratoma of oral mucosa. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1981, 52, 422–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, B.W.; Coleman, P.J.; Richardson, M.S. Verruciform xanthoma associated with an intraoral warty dyskeratoma. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 1996, 81, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George Laskaris, A.S. Warty dyskeratoma of the oral mucosa. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1985, 23, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, M.N.Y.; Radden, B.G. Oral warty dyskeratoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 1984, 13, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, G. Focal acantholytic dyskeratosis and epidermolytic hyperkeratosis of the oral mucosa adjacent to squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1985, 59, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, F.J. Warty Dyskeratoma: A Benign Cutaneous Tumor Resembling Darier’s Disease Microscopically. AMA Arch. Dermatol. 1957, 75, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, R.B.; Kallarakkal, T.G.; Ramanathan, A.; Kim, J.; Tilakaratne, W.M.; Takata, T.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Kumar, V.; Alison Rich, H.; Mohd Hussaini, H.; et al. A consensus report from the first Asian regional meeting on the terminology and criteria for verruco-papillary lesions of the oral cavity held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, December 15-18, 2013. Ann. Dent. Univ. Malaya 2013, 20, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Patil, S.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Raj, T.; Sanketh, D.S.; Rao, R.S. Exophytic oral verrucous hyperplasia: A new entity. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, S.J. HPV-Related Papillary Lesions of the Oral Mucosa: A Review. Head Neck Pathol. 2019, 13, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaddu, S.; Dong, H.; Mayer, G.; Kerl, H.; Cerroni, L. Warty dyskeratoma-“Follicular dyskeratoma”: Analysis of clinicopathologic features of a distinctive follicular adnexal neoplasm. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002, 47, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).