Abstract

(1) Background: Data on persisting symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents are conflicting. Due to the absence of a clear pathophysiological correlate and a definitive diagnostic test, the diagnosis of Long COVID currently rests on consensus definitions only. This review aims to summarise the evidence regarding Long COVID in children and adolescents, incorporating the latest studies on this topic. (2) Methods: We designed a comprehensive search strategy to capture all relevant publications using Medline via the PubMed interface, with the initial literature search conducted in April 2023. To be included, publications had to present original data and include >50 participants with Long COVID symptoms aged between 0 and18 years. (3) Results: A total of 51 studies met the inclusion criteria, with most studies originating from Europe (n = 34; 66.7%), followed by the Americas (n = 8; 15.7%) and Asia (n = 7; 13.7%). Various study designs were employed, including retrospective, cross-sectional, prospective, or ambispective approaches. Study sizes varied significantly, with 18/51 studies having fewer than 500 participants. Many studies had methodological limitations: 23/51 (45.1%) studies did not include a control group without prior COVID-19 infection. Additionally, a considerable number of papers (33/51; 64.7%) did not include a clear definition of Long COVID. Other limitations included the lack of PCR- or serology-based confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the study group. Across different studies, there was high variability in the reported prevalence of Long COVID symptoms, ranging from 0.3% to 66.5%, with the majority of studies included in this review reporting prevalences of approximately 10–30%. Notably, the two studies with the highest prevalences also reported very high prevalences of Long COVID symptoms in the control group. There was a relatively consistent trend for Long COVID prevalence to decline substantially over time. The prevalence of Long COVID appeared to differ across different paediatric age groups, with teenagers being more commonly affected than younger children. Furthermore, data suggest that children and adolescents are less commonly affected by Long COVID compared to adults. In children and adolescents, Long COVID is associated with a very broad range of symptoms and signs affecting almost every organ system, with the respiratory, cardiovascular, and neuropsychiatric systems being most commonly affected. (4) Conclusions: The heterogeneity and limitations of published studies on Long COVID in children and adolescents complicate the interpretation of the existing data. Future studies should be rigorously designed to address unanswered questions regarding this complex disease.

1. Introduction

In the winter of 2019, a novel pathogenic virus, SARS-CoV-2, emerged in China and rapidly spread globally throughout 2020 [1,2]. The disease caused by this virus, closely related to the virus causing Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), was initially termed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and is commonly referred to as simply COVID.

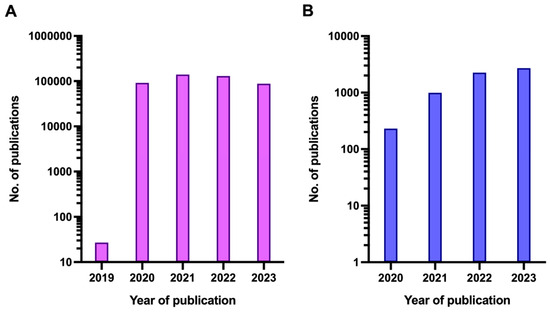

By summer 2023, there had been more than 700 million confirmed COVID-19 cases and almost 7 million COVID-19-related deaths globally according to World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates, although it is likely that these official figures substantially underestimate the true burden of the disease and the fatalities caused by SARS-CoV-2 [3]. Simultaneous with the rise in COVID-19 cases, the literature on COVID-19 started to increase exponentially, with the number of publications peaking at a total annual rate of 138,949 in 2021 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of publications featuring the term COVID (A) or any of the terms ‘Long COVID’, ‘Post-acute COVID’ or ‘PASC’ (B) per year since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Note that the y-axis is logarithmic.

During and shortly after the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, two new disease entities were described: multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) and Long COVID, the topic of this review. In both conditions variations in the terminology used by authors of early publications led to some degree of confusion among medical practitioners, as well as the general public. MIS-C was first described by authors from Italy and the United Kingdom [4,5], although the term was not used in either publication. In the Italian paper, ‘Kawasaki-like disease’ was used, while the UK paper referred to ‘Hyperinflammatory sepsis’. While in the United Kingdom, the term ‘Paediatric Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome Temporally Associated with SARS-CoV-2’ (PIMS-TS) was mainly used subsequently, the term MIS-C dominated in papers originating from the United States [6,7,8]. In May 2020, the WHO adopted the latter term with some expansion [9].

Similar to MIS-C, a plethora of terms have been used to describe Long COVID, which will be used in this review, including long-term COVID, chronic COVID, post-acute COVID, post-COVID conditions, long-haul COVID, long-term effects of COVID, and post-acute SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). Recent evidence suggests that Long COVID phenotypes may cluster into four distinct phenotypes: (a) type 1: heart, kidney, and circulatory problems, (b) type 2: lung conditions, sleep disorders, and anxiety, (c) type 3: muscle pain, connective tissue disorders, and nervous system disorders, and (d) type 4: digestive and respiratory problems [10]. However, both the literature and our personal experience suggest that patients not infrequently suffer from a range of symptoms that do not conform to a single one of those phenotypes.

Since at present there is no pathophysiological correlate of Long COVID and no diagnostic test, the diagnosis of Long COVID rests on somewhat vague definitions alone (Table 1). The WHO defined Long COVID (Post-COVID-19 condition) as “the continuation or development of new symptoms 3 months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, with these symptoms lasting for at least 2 months with no other explanation” [11]. The relevant WHO fact sheet states that “Long COVID can include fatigue, shortness of breath and cognitive dysfunction; over 200 different symptoms have been reported that can have an impact on everyday functioning”. In contrast, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition states that Long COVID is characterised by signs, symptoms, and conditions that are present four weeks or more after the initial phase of infection (Table 1) [12]. Importantly, the DHHS/CDC highlights that Long COVID is likely not a single disease entity, but rather a collection of entities.

Table 1.

Overview of key definitions for acute COVID-19 and health conditions following the acute infection.

Another definition specifically for children and adolescents has been proposed by a team of UK-based researchers, who conducted a Delphi process that included input from young patients (aged 11–17 years) suffering from Long COVID [15]. The consensus definition was as follows: “Post-COVID-19 condition occurs in young people with a history of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, with one or more persisting physical symptoms for a minimum duration of 12 weeks after initial testing that cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis” (Table 1).

While the WHO definition is probably the most commonly used definition, there is a plethora of alternative definitions frequently designed by researchers who have conducted studies on patients with Long COVID. This heterogeneity in disease definitions across studies is problematic, as individual definitions are potentially over- or under-inclusive and significantly complicate comparisons between studies, as well as data synthesis in systematic reviews.

Several reviews on Long COVID in general and in children in particular have been published in the past [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. However, even between systematic reviews (i.e., rather than narrative reviews), there is incomplete overlap in the studies included, potentially introducing bias into the data and conclusions presented in each review. It appears likely that this issue resulted from, firstly, difficulties in designing an all-encompassing search strategy that can identify all relevant papers (primarily due to the heterogeneity of terms and definitions used for Long COVID), and secondly, from the fact that all studies have been conducted in the very recent past, and consequently, the corresponding papers were at various stages of the publication process (e.g., accepted and published on journal homepage, electronically published and linked to PubMed records, or published in print) when reviews were conducted, and thereby some studies evaded detection.

The aim of this systematic review was to produce the most comprehensive review on Long COVID in children and adolescents to date, incorporating the latest studies on this topic.

2. Materials and Methods

For the purpose of this review, we designed a search strategy aimed to be as inclusive as possible. After trialling a number of variations in wording and combinations, we arrived at the following search string: ((COVID) OR (SARS-CoV-2)) AND ((child) OR (adolescent) OR (paediatric) OR (paediatric)) AND ((long) OR (long-term) OR (long term) OR (prolonged) OR (post-COVID) OR (post COVID) OR (PASC) OR (persisting) OR (persistent) OR (chronic) OR (post-acute) OR (sequelae)).

To be included in this review, publications had to fulfil the following inclusion criteria: 1. the publication reports a study on Long COVID in children and/or adolescents (aged 0–18 years) or a study including paediatric and adult patients in which the data of paediatric and adult patients can be separated; 2. the publication includes more than 50 paediatric patients with Long COVID; and 3. the publication is written in English, French, German, or Spanish. Publications not meeting all three criteria, non-peer-reviewed publications, and conference abstracts were excluded.

The initial search was conducted on 24 April 2023, using Medline via the PubMed interface. Abstracts identified in this search were subsequently screened by one of the authors (MR). In instances where it was uncertain if a publication met the inclusion criteria, a second author reviewed the abstract (MT). Following this initial round of selection, full-text articles were retrieved to determine eligibility for inclusion and to extract the relevant data in a structured fashion using a specifically designed template. All relevant publications were hand-searched for further references potentially fulfilling the inclusion criteria, as were the aforementioned reviews [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

3. Results

A total of 51 articles met the inclusion criteria outlined above and were therefore included in this review. Of these, 42 studies broadly focused on Long COVID, 3 focused on mental health only, 3 on anosmia/ageusia, 2 on cardiac aspects, and 1 on pulmonary function and inflammatory markers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of all studies providing data on Long COVID in children and adolescents included in this review.

Only 2 studies were multi-country studies, while the remaining 49 studies were conducted in a single country. The large majority of studies originated from Europe (n = 34; 66.7%), followed by the Americas (n = 8; 15.7%) and Asia (n = 7; 13.7%). Among the European studies, the highest number of reports originated from the United Kingdom (n = 9), followed by studies from Italy (n = 8), Russia (n = 4), and Denmark (n = 4). Among non-European studies, a comparatively high number originated from the United States and Israel (both n = 5). The included studies employed a range of study designs and were retrospective, cross-sectional, prospective, or ambispective. Eighteen of the studies included fewer than 500 patients (Table 2); five of those included fewer than 100 patients [26,54,68,74,75].

3.1. Quality of the Included Studies and Their Limitations

As shown in Table 2, a large proportion of the included studies had methodological limitations. Twenty-three of the studies did not include a control group without prior COVID-19 infection, complicating the interpretation of the study findings. This is particularly relevant as the unusual living conditions (e.g., school closures, stay-at-home policies, and shielding at home) and social isolation during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to have had a substantial impact on the psychological well-being of children in general, and therefore it cannot be ruled out that many of the neuropsychiatric symptoms observed by those uncontrolled studies were the result of those conditions rather than the consequence of preceding SARS-CoV-2 infection. Importantly, studies that did include a control group without COVID-19 infection showed that the prevalence of fatigue, mood swings, anxiety, concentration difficulties, and pain symptoms in that group was substantial, commonly affecting 5–20% of the control population [29,42,52,56,61,64]. This is consistent with robust data from large-scale studies that have shown that living conditions during the pandemic adversely affected mental health, causing a significant increase in major depression and anxiety disorders [76]. Furthermore, many of the neuropsychiatric symptoms reported by various studies, such as fatigue, weakness, lack of energy, low mood, lack of concentration, sleep disturbance, and pain symptoms (e.g., headaches, myalgia, arthralgia), are highly subjective. A number of papers did not include a definition for Long COVID, complicating the interpretation of the data presented, as well as comparisons with other studies. Two studies appeared to exclusively include children who experienced symptomatic COVID-19, while children with asymptomatic infection seem to have been excluded for unclear reasons [27,28]. Other studies included children with significant pre-existing medical conditions (e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and neuropsychiatric disorders), and it remains uncertain whether certain symptoms reported, including sleep issues, concentration issues, and fatigue, were due to medical conditions that predated SARS-CoV-2 infection rather than representing Long COVID [26]. Other studies included a substantial proportion of children in whom there was no clear evidence of prior COVID-19 infection (i.e., based on PCR or serology), which potentially resulted in skewing of the reported data [27,30,71]. Furthermore, a large proportion of studies did not reliably exclude prior COVID-19 in the individuals that constituted the control group (e.g., via serological testing). None of the included studies provide a detailed analysis of the impact of prior vaccination directed against SARS-CoV-2. Finally, some of the study populations of the included studies comprised mainly adult patients, with only a minority of study subjects being in the paediatric age range [36,49,62].

3.2. Prevalence of Prolonged Symptoms in Children following SARS-CoV-2 Infection

The reported prevalences of Long COVID varied widely between studies. The majority of studies included in this review reported prevalences of Long COVID following acute SARS-CoV-2 infection of approximately 10–30%. The studies that reported the lowest and highest prevalences are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of studies reporting the lowest (top) and highest (bottom) prevalence figures of Long COVID in children and adolescents, including how the diagnosis was established.

The study that observed the lowest overall prevalence (0.31%) was the study conducted by Merzon et al., which was based on electronic health records [47]. Other studies with low prevalences (4.1–5.8%) were solely based on self-reporting [27,37,48,50]. Notably, three of the five studies reporting the lowest prevalences did not include a control group [27,37,47]. The study by Molteni et al. was the only one among these that included a control group and provided the overall prevalence of Long COVID symptoms in that group [50]. The authors found that 4.4% of SARS-CoV-2-positive patients had symptoms compatible with Long COVID at 4 weeks, compared with 0.9% in the control group.

The studies reporting the highest prevalences were those by Kikkenborg Berg et al. and Stephenson et al., with prevalences of 61.9% and 66.5% in SARS-CoV-2-positive patients at >8 weeks and >12 weeks, respectively. However, both studies also reported very high prevalences of Long COVID symptoms in the control group (57.0% and 53.3%, respectively), raising the possibility that the definition of Long COVID used in the studies had a tendency to be overinclusive [41,63].

A very large study from Denmark, including more than 15,000 children who had experienced SARS-CoV-2 infection and more than 15,000 controls, found that a large proportion of participants in both groups had symptoms lasting >4 weeks (25.4% vs. 22.9%) [29]. Although this difference in proportions appears small, it was highly statistically significant. In preschool children, fatigue, loss of smell, and muscle weakness were more common in the case group than in the control group; in school children loss of smell, loss of taste, dizziness, fatigue, respiratory problems, chest pain, and muscle weakness were more common in the former than in the latter group. However, overall, the risk differences (RD) between cases and controls for each of these symptoms were small, except for loss of smell (RD 0.12), loss of taste (RD 0.10), and fatigue (RD 0.05) (Table 2).

An Italian study that included both children and adults found that persisting symptoms (>4 weeks) after SARS-CoV-2 infection were significantly more common in adults than in children [33]. At the first follow-up (1–3 months after infection), 67% of adults had persisting symptoms, compared with only 32% of children (p < 0.0001). Children were also more likely to have fully recovered at the 6–9 months follow-up compared with their adult counterparts (p = 0.01).

Another paper from Italy reported differences in the range of symptoms experienced depending on gender [34]. While headache, insomnia, and altered taste were the most common persisting symptoms in girls, persistent cough, myalgia, confusion, reduced appetite, and diarrhea predominated in boys. The same study also found that a substantial proportion of patients with initially persisting symptoms improved or showed complete resolution over time.

Several of the included studies provided data showing that the prevalence of Long COVID following SARS-CoV-2 infection differs across various paediatric age groups, with the highest prevalences observed in teenagers [37,38,42,51,53,61]. Kikkenborg Berg et al. observed persistent symptoms lasting more than 8 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection in 34.0% of children aged 4–11 years, compared with 42.1% of children/adolescents aged 12–14 years.

Similarly, a study analysing data from a tertiary children’s hospital in Moscow, using multivariable regression analysis, found that older age was associated with persistent symptoms lasting longer than 5 months. Compared with children <2 years of age, children aged 6–11 years and 12–18 years had a significantly higher risk of developing persistent symptoms [Odds Ratio (OR) 2.7 (1.4–5.8) and OR 2.7 (1.4–5.4)], respectively; notably, the figures in the abstract diverge from those shown in the results section of the paper] [53]. However, it has to be taken into account that determining the presence of symptoms in children younger than 2 years is challenging; notably, children of that age would not be able to report a substantial number of the symptoms included in the study’s questionnaire, such as chest tightness, dizziness, disturbed smell, loss of taste, or feeling nauseous.

Furthermore, a study from England by Atchison et al. reported that persistent symptoms occurred in 4.4% of 5–11-year-olds compared with 13.3% of 12–17-year-olds, corresponding to an adjusted odds ratio of 3.4 (95% CI 2.8–4.0) [27].

3.3. Range of Symptoms

The papers included in this review report a very broad range of symptoms and signs associated with Long COVID in children and adolescents. The most commonly affected systems overall were the respiratory, cardiovascular, and neuropsychiatric systems. However, the prevalence of individual symptoms in patients with Long COVID varied substantially between studies (Table 2).

A review by Lopez-Leon et al. published in 2022, which included 21 studies in a meta-analysis, found that the most common neuropsychiatric symptoms in paediatric Long COVID patients were mood changes, fatigue, and sleep disorders, followed by headaches, impaired cognition, and dizziness [20]. The most common cardiorespiratory symptoms included dyspnoea, chest pain/tightness, cough, sore throat, rhinorrhoea, and orthostatic intolerance. Other symptoms that were common included loss of taste and smell, loss of appetite, myalgia/arthralgia and hyperhidrosis. The authors also calculated the pooled Odds Ratios (OR) of 13 key symptoms using data from four studies that included both cases and controls, and found that only three of these symptoms (dyspnoea, fever, and anosmia/ageusia) were significantly more common in patients with prior microbiologically-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection than in controls [OR 2.69 (95% CI: 2.30–3.14), OR 2.23 (95% CI: 1.2–4.07), and OR 10.68 (95% CI: 2.48–46.03), respectively]. In contrast, there was no significant difference between cases and controls regarding mood, fatigue, headache, concentration problems, loss of appetite, rhinitis, myalgia/arthralgia, cough, sore throat, and nausea/vomiting.

A study by Sorensen et al., which evaluated persistent symptoms in PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases (n = 2350) and SARS-CoV-2-negative controls (n = 3181) aged 15–19, years provided data stratified by gender. In females, dyspnoea [RD 2.37 (95% CI: 1.09–3.65)], chest pain [RD 2.62 (95% CI: 1.43–3.98)], dizziness [RD 2.38 (95% CI: 0.84–3.99)], fatigue/exhaustion [RD 7.37 (95% CI: 5.41–9.49)], headaches [RD 2.59 (95% CI: 0.99–4.33)], dysosmia [RD 11.77 (95% CI: 9.80–13.72)], dysgeusia [RD 9.56 (95% CI: 7.87–11.23)], reduced appetite [RD 8.89 (95% CI: 3.24–6.62)], and reduced strength in legs/arms [RD 1.75 (95% CI: 0.54–2.95)] were more common in cases than in controls. Among males, only dysosmia [RD 8.46 (95% CI: 6.08–10.72)], dysgeusia [RD 6.97 (95% CI: 5.25–8.92)], reduced appetite [RD 2.63 (95% CI: 1.10–4.28)], and reduced strength in legs/arms [RD 1.76 (95% CI: 0.61–3.03)] were observed more frequently in cases than in controls. The study also found that in both genders, difficulties concentrating, memory issues, mental exhaustion, physical exhaustion, and sleep problems occurred in a substantially higher proportion of cases compared with controls. Furthermore, the study found that cases were more likely to have received a formal diagnosis of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and fibromyalgia compared with controls, suggesting a significant overlap between the symptoms associated with these entities and those of Long COVID [62].

A U.S. study involving children and adolescents aged 0–17 years, based on medical claims and commercial laboratory data and including 781,419 patients with COVID-19 and 2,344,257 patients without, compared the prevalence of a range of symptoms and medical conditions between the two groups [43]. The authors reported that smell and taste disturbances [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 1.17 (95% CI: 1.11–1.24)], circulatory signs and symptoms [aHR 1.07 (95% CI: 1.05–1.08)], malaise and fatigue [aHR 1.05 (95% CI: 1.03–1.06)], and musculoskeletal pain [aHR 1.02 (95% CI: 1.02–1.03)] were more common in cases than in controls. Surprisingly, sleep disorders [aHR 0.91 (95% CI: 0.90–0.93)], respiratory signs and symptoms [aHR 0.91 (95% CI: 0.91–0.92)], and symptoms of mental conditions [aHR 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89–0.93)] were more common in controls than in cases. Notably, all reported aHR values were close to 1, indicating that differences between cases and controls were relatively small. It was also notable that neurological conditions [aHR 0.94 (95% CI: 0.92–0.95)], anxiety and fear-related disorders [aHR 0.85 (95% CI: 0.84–0.86)] and mood disorders [aHR 0.78 (95% CI: 0.75–0.80)] were more commonly observed in controls than in cases [43].

3.4. Periodicity versus Chronicity of Long COVID

One survey-based study that included the parents of more than 500 children with persistent symptoms after COVID-19 examined the temporal characteristics of symptoms in children with possible Long COVID [32]. The authors found that in only 25% of those children, symptoms that had occurred during the original infection had persisted (i.e., chronicity), while 49% were experiencing an intermittent pattern of symptoms (i.e., switching between being asymptomatic and symptomatic); in a smaller proportion (19%) of participants, symptoms had newly emerged after a period of being well following COVID-19. However, one crucial limitation of that study was that in 41% of the children, the diagnosis of COVID-19 had not been confirmed by a test or a medical professional.

3.5. Impact of Virus Strain on the Likelihood of Long COVID

Most included papers provided no details regarding the circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains during the study period, complicating an assessment of the impact of the infecting strain on the risk of developing Long COVID. One study from Italy by Buonsenso et al. compared the prevalence of persisting symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection between children infected with the wild-type virus and children who had acquired infection with the Omicron variant [35]. The authors found that all symptoms included in the analyses were more common after infection with the wild-type virus (comparisons statistically significant for: fatigue, insomnia, myalgia, joint pain/swelling, and altered taste), except for persistent cough, which was more common after infection with the Omicron variant.

3.6. Risk Factors for Long COVID other than Virus Strain

One multicentre study that included 39 emergency departments across 8 countries found that the risk of developing Long COVID was lower in children who had PCR-confirmed COVID-19 but could be discharged from the emergency department than in children who had to be hospitalised due to the infection (4.6% vs. 9.8%) [37], indicating that greater disease severity may result in a higher chance of developing Long COVID. Although a statistical comparison of these two subgroups was not included in the original paper, we performed this comparison using data provided in the manuscript, which was statistically highly significant (Fisher’s exact test; p = 0.0001). The same study also found that SARS-CoV-2 positive patients who required hospitalisation had a higher risk of having persistent symptoms than matched SARS-CoV-2 negative controls that had been hospitalised during the same period. Using multiple logistic regression, the authors identified the following risk factors for Long COVID: age 14–18 years, ≥4 symptoms at ED presentation, and hospitalisation for ≥48 h.

Five of the included studies analysed whether there was an association between Long COVID and pre-existing comorbidities in children and adolescents [47,51,53,55,61]. However, four of these studies lacked a control group without exposure to SARS-CoV-2, which complicates the interpretation of the data presented [47,51,53,55]. Merzon et al. found that the risk of developing Long COVID was increased in children with attention deficit hyperkinetic disorder, chronic allergic rhinitis, and chronic urticaria. Osmanov et al. found an increased risk in children with a history of allergic disease. Pazukhina et al. observed an elevated risk in patients with neurological comorbidities or allergic respiratory disease. The only study that included a control group, by Seery et al., observed an increased risk in patients with pre-existing respiratory diseases, renal diseases, and diabetes [61].

3.7. Duration of Symptoms

One prospective cohort study from Italy, which included 676 participants aged 0–18 years, reported that symptoms related to presumed Long COVID tended to resolve over the course of several months [34]. In this study, patients were assessed at three different time intervals: (1) at 1–5 months (n = 355), (2) at 6–9 months (n = 157), and (3) at >12 months (n = 154). Over time, there was a significant reduction in the proportion of patients reporting myalgia (at 1st interval 10% vs. 3.2% at 3rd interval), chest pain (3.8% vs. 0), and difficulties breathing/chest tightness (3.9% vs. 0). Most other symptoms assessed also showed a decline, but the corresponding statistical comparisons did not reach significance. At the last time period, 89% of parents reported that their child had completely or almost completely recovered. Only 0.7% (equating to one family) believed that their child had shown ‘poor recovery’ at that point.

Other studies included in this review also observed a trend for Long COVID prevalence to decline over time, including the studies by Jamaica Balderas et al., Morello et al., and Pazukhino et al. [39,51,55]. The former group observed persistent symptoms in 32.6% of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients after 2 months, which declined to 9.3% after 4 and 2.3% after 6 months. Morello et al. found a prevalence of Long COVID of 23% at 3 months; of the patients who also had a follow-up at 6 months, 53% still reported symptoms, with the prevalence declining to 23% at 12 months and 19% at 18 months. However, only 77 of 294 patients with Long COVID symptoms at 3 months were followed up for the entire duration of the study [51]. Finally, Pazukhina et al. observed at least one persistent symptom after SARS-CoV-2 infection in 20% of children at 6 months, declining to 11% at 12 months [55].

3.8. Impact of Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2

One important issue that has been investigated after the completion of our review is whether vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 can modify the risk of developing Long COVID. Some adult studies have suggested that prior vaccination reduces the risk of Long COVID, but others have not made the same observation [77,78,79,80,81,82]. A detailed discussion of this issue is outside the scope of this paper, but a comprehensive review of the recent literature on this topic can be found elsewhere [83].

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the prevalence of Long COVID in children and adolescents, as well as the range of symptoms associated with the disease and risk factors predisposing to its development, remain uncertain despite the existence of a large number of studies investigating those aspects. We found considerable variation in the reported prevalences of Long COVID in children and adolescents in the studies included in this review. Studies that included age stratification indicate that Long COVID is more common in adolescents than in younger children. The published data suggest that Long COVID can affect almost every organ system, although the respiratory, cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric systems appear to be most commonly affected. One finding consistently observed across different studies was that the prevalence of symptoms associated with Long COVID declines substantially over time, indicating that spontaneous resolution of the condition is common.

Lack of consistency between disease definitions of Long COVID considerably complicates comparisons between studies. Many existing studies had methodological limitations, including the lack of any control group or the absence of a control group in which prior COVID-19 infection had been excluded with some degree of certainty. Many studies exclusively relied on self-reporting (or parent-reporting) of symptoms and signs, rather than a detailed clinical evaluation by trained clinicians or allied health professionals.

Importantly, studies that included a control group without prior COVID-19 infection found that neuropsychiatric symptoms were common in the control population, especially in adolescents. This raises the question to what extent symptoms had been caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection and to what extent they were attributable to the unusual living circumstances during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, the literature on Long COVID is heavily dominated by European data, and it is unclear whether the results can be extrapolated to other geographical regions.

Further controlled studies are required to obtain more robust data on Long COVID in children and adolescents, although finding individuals who have never experienced SARS-CoV-2 infection at this point in time is likely to prove challenging. Additionally, further studies are needed to clarify the potential pathomechanisms underlying Long COVID and to identify biomarkers that could aid in the diagnosis of this condition.

Author Contributions

A.Z. conceived of the review. M.R. and F.L. did the literature search, supervised by M.T.; M.R. and M.T. wrote the first version of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Danilo Buonsenso, Eugene Merzon, Sarah E. Messiah, Anna Irene Vedel Sørensen and Snehal Pinto Pereira for kindly providing additional data related to their original manuscripts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Worobey, M. Dissecting the early COVID-19 cases in Wuhan. Science 2021, 374, 1202–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotzinger, F.; Santiago-Garcia, B.; Noguera-Julian, A.; Lanaspa, M.; Lancella, L.; Calo Carducci, F.I.; Gabrovska, N.; Velizarova, S.; Prunk, P.; Osterman, V.; et al. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: A multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Coronavirus Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Verdoni, L.; Mazza, A.; Gervasoni, A.; Martelli, L.; Ruggeri, M.; Ciuffreda, M.; Bonanomi, E.; D’Antiga, L. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: An observational cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1771–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riphagen, S.; Gomez, X.; Gonzalez-Martinez, C.; Wilkinson, N.; Theocharis, P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020, 395, 1607–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, S.; Aydin, S.I.; Derespina, K.R.; Bansal, P.B.; Kowalsky, S.; Trachtman, R.; Gillen, J.K.; Perez, M.M.; Soshnick, S.H.; Conway, E.E., Jr.; et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (MIS-C): A multi-institutional study from New York City. J. Pediatr. 2020, 224, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, A.H. Understanding SARS-CoV-2-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 453–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldstein, L.R.; Rose, E.B.; Horwitz, S.M.; Collins, J.P.; Newhams, M.M.; Son, M.B.F.; Newburger, J.W.; Kleinman, L.C.; Heidemann, S.M.; Martin, A.A.; et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Scientific Brief: Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and Adolescents Temporally Related to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-and-adolescents-with-covid-19 (accessed on 4 September 2023).

- Zhang, H.; Zang, C.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Bian, J.; Morozyuk, D.; Khullar, D.; Zhang, Y.; Nordvig, A.S.; et al. Data-driven identification of post-acute SARS-CoV-2 infection subphenotypes. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Fact Sheet: Post COVID-19 Condition (Long COVID). Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition#:~:text=It%20is%20defined%20as%20the,months%20with%20no%20other%20explanation (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Long COVID Terms & Definitions. Available online: https://www.covid.gov/be-informed/longcovid/about#term (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- World Health Organization. A Clinical Case Definition of Post COVID-19 Condition by a Delphi Consensus. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post_COVID-19_condition-Clinical_case_definition-2021.1 (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- World Health Organization. A Clinical Case Definition for Post COVID-19 Condition in Children and Adolescents by Expert Consensus. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Post-COVID-19-condition-CA-Clinical-case-definition-2023-1 (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Stephenson, T.; Allin, B.; Nugawela, M.D.; Rojas, N.; Dalrymple, E.; Pinto Pereira, S.; Soni, M.; Knight, M.; Cheung, E.Y.; Heyman, I.; et al. Long COVID (post-COVID-19 condition) in children: A modified Delphi process. Arch. Dis. Child. 2022, 107, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: COVID-19 Rapid Guideline: Managing the Long-Term Effects of COVID-19. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188/history (accessed on 2 February 2024).

- Behnood, S.A.; Shafran, R.; Bennett, S.D.; Zhang, A.X.D.; O’Mahoney, L.L.; Stephenson, T.J.; Ladhani, S.N.; De Stavola, B.L.; Viner, R.M.; Swann, O.V. Persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection amongst children and young people: A meta-analysis of controlled and uncontrolled studies. J. Infect. 2022, 84, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fainardi, V.; Meoli, A.; Chiopris, G.; Motta, M.; Skenderaj, K.; Grandinetti, R.; Bergomi, A.; Antodaro, F.; Zona, S.; Esposito, S. Long COVID in children and adolescents. Life 2022, 12, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, P.; Pittet, L.F.; Curtis, N. How common is long COVID in children and adolescents? Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, e482–e487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Ayuzo Del Valle, N.C.; Perelman, C.; Sepulveda, R.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Cuapio, A.; Villapol, S. Long-COVID in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrino, R.; Chiappini, E.; Licari, A.; Galli, L.; Marseglia, G.L. Prevalence and clinical presentation of long COVID in children: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 3995–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, T.; Shafran, R.; Ladhani, S.N. Long COVID in children and adolescents. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 35, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.B.; Zeng, N.; Yuan, K.; Tian, S.S.; Yang, Y.B.; Gao, N.; Chen, X.; Zhang, A.Y.; Kondratiuk, A.L.; Shi, P.P.; et al. Prevalence and risk factor for long COVID in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, L.; Israel, M.; Yehoshua, I.; Azuri, J.; Hoffman, R.; Shahar, A.; Mizrahi Reuveni, M.; Grossman, Z. Long COVID symptoms in Israeli children with and without a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e064155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashkenazi-Hoffnung, L.; Shmueli, E.; Ehrlich, S.; Ziv, A.; Bar-On, O.; Birk, E.; Lowenthal, A.; Prais, D. Long COVID in children: Observations from a designated pediatric clinic. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, e509–e511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atchison, C.J.; Whitaker, M.; Donnelly, C.A.; Chadeau-Hyam, M.; Riley, S.; Darzi, A.; Ashby, D.; Barclay, W.; Cooke, G.S.; Elliott, P.; et al. Characteristics and predictors of persistent symptoms post-COVID-19 in children and young people: A large community cross-sectional study in England. Arch. Dis. Child. 2023, 108, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergia, M.; Sanchez-Marcos, E.; Gonzalez-Haba, B.; Hernaiz, A.I.; de Ceano-Vivas, M.; Garcia Lopez-Hortelano, M.; Garcia-Garcia, M.L.; Jimenez-Garcia, R.; Calvo, C. Comparative study shows that 1 in 7 Spanish children with COVID-19 symptoms were still experiencing issues after 12 weeks. Acta Paediatr. 2022, 111, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borch, L.; Holm, M.; Knudsen, M.; Ellermann-Eriksen, S.; Hagstroem, S. Long COVID symptoms and duration in SARS-CoV-2 positive children—A nationwide cohort study. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brackel, C.L.H.; Lap, C.R.; Buddingh, E.P.; van Houten, M.A.; van der Sande, L.; Langereis, E.J.; Bannier, M.; Pijnenburg, M.W.H.; Hashimoto, S.; Terheggen-Lagro, S.W.J. Pediatric long-COVID: An overlooked phenomenon? Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 2495–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonsenso, D.; Munblit, D.; De Rose, C.; Sinatti, D.; Ricchiuto, A.; Carfi, A.; Valentini, P. Preliminary evidence on long COVID in children. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 2208–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonsenso, D.; Pujol, F.E.; Munblit, D.; Pata, D.; McFarland, S.; Simpson, F.K. Clinical characteristics, activity levels and mental health problems in children with long coronavirus disease: A survey of 510 children. Future Microbiol. 2022, 17, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonsenso, D.; Munblit, D.; Pazukhina, E.; Ricchiuto, A.; Sinatti, D.; Zona, M.; De Matteis, A.; D’Ilario, F.; Gentili, C.; Lanni, R.; et al. Post-COVID condition in adults and children living in the same household in Italy: A prospective cohort study using the ISARIC global follow-up protocol. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 834875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonsenso, D.; Pazukhina, E.; Gentili, C.; Vetrugno, L.; Morello, R.; Zona, M.; De Matteis, A.; D’Ilario, F.; Lanni, R.; Rongai, T.; et al. The prevalence, characteristics and risk factors of persistent symptoms in non-hospitalized and hospitalized children with SARS-CoV-2 infection followed-up for up to 12 months: A prospective, cohort study in Rome, Italy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonsenso, D.; Morello, R.; Mariani, F.; De Rose, C.; Mastrantoni, L.; Zampino, G.; Valentini, P. Risk of long Covid in children infected with Omicron or pre-Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variants. Acta Paediatr. 2023, 112, 1284–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevinsky, J.R.; Tao, G.; Lavery, A.M.; Kukielka, E.A.; Click, E.S.; Malec, D.; Kompaniyets, L.; Bruce, B.B.; Yusuf, H.; Goodman, A.B.; et al. Late conditions diagnosed 1–4 months following an initial Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) encounter: A matched-cohort study using inpatient and outpatient administrative data—United States, 1 March–30 June 2020. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, S5–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funk, A.L.; Kuppermann, N.; Florin, T.A.; Tancredi, D.J.; Xie, J.; Kim, K.; Finkelstein, Y.; Neuman, M.I.; Salvadori, M.I.; Yock-Corrales, A.; et al. Post-COVID-19 conditions among children 90 days after SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2223253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guido, C.A.; Lucidi, F.; Midulla, F.; Zicari, A.M.; Bove, E.; Avenoso, F.; Amedeo, I.; Mancino, E.; Nenna, R.; De Castro, G.; et al. Neurological and psychological effects of long COVID in a young population: A cross-sectional study. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 925144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamaica Balderas, L.; Navarro Fernandez, A.; Dragustinovis Garza, S.A.; Orellana Jerves, M.I.; Solis Figueroa, W.E.; Koretzky, S.G.; Marquez Gonzalez, H.; Klunder Klunder, M.; Espinosa, J.G.; Nieto Zermeno, J.; et al. Long COVID in children and adolescents: COVID-19 follow-up results in third-level pediatric hospital. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1016394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsuta, T.; Aizawa, Y.; Shoji, K.; Shimizu, N.; Okada, K.; Nakano, T.; Kamiya, H.; Amo, K.; Ishiwada, N.; Iwata, S.; et al. Acute and postacute clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in children in Japan. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikkenborg Berg, S.; Dam Nielsen, S.; Nygaard, U.; Bundgaard, H.; Palm, P.; Rotvig, C.; Vinggaard Christensen, A. Long COVID symptoms in SARS-CoV-2-positive adolescents and matched controls (LongCOVIDKidsDK): A national, cross-sectional study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2022, 6, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikkenborg Berg, S.; Palm, P.; Nygaard, U.; Bundgaard, H.; Petersen, M.N.S.; Rosenkilde, S.; Thorsted, A.B.; Ersboll, A.K.; Thygesen, L.C.; Nielsen, S.D.; et al. Long COVID symptoms in SARS-CoV-2-positive children aged 0–14 years and matched controls in Denmark (LongCOVIDKidsDK): A national, cross-sectional study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2022, 6, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kompaniyets, L.; Bull-Otterson, L.; Boehmer, T.K.; Baca, S.; Alvarez, P.; Hong, K.; Hsu, J.; Harris, A.M.; Gundlapalli, A.V.; Saydah, S. Post-COVID-19 symptoms and conditions among children and adolescents—United States, March 1, 2020-January 31, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuitunen, I. Long COVID-19 is rarely diagnosed in children: Nationwide register-based analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2023, 108, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorman, V.; Rao, S.; Jhaveri, R.; Case, A.; Mejias, A.; Pajor, N.M.; Patel, P.; Thacker, D.; Bose-Brill, S.; Block, J.; et al. Understanding pediatric long COVID using a tree-based scan statistic approach: An EHR-based cohort study from the RECOVER Program. JAMIA Open 2023, 6, ooad016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messiah, S.E.; Xie, L.; Mathew, M.S.; Shaikh, S.; Veeraswamy, A.; Rabi, A.; Francis, J.; Lozano, A.; Ronquillo, C.; Sanchez, V.; et al. Comparison of long-term complications of COVID-19 illness among a diverse sample of children by MIS-C status. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merzon, E.; Weiss, M.; Krone, B.; Cohen, S.; Ilani, G.; Vinker, S.; Cohen-Golan, A.; Green, I.; Israel, A.; Schneider, T.; et al. Clinical and socio-demographic variables associated with the diagnosis of Long COVID syndrome in youth: A population-based study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, F.; Nguyen, D.V.; Navaratnam, A.M.; Shrotri, M.; Kovar, J.; Hayward, A.C.; Fragaszy, E.; Aldridge, R.W.; Hardelid, P.; VirusWatch, C. Prevalence and characteristics of persistent symptoms in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a household cohort study in England and Wales. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2022, 41, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizrahi, B.; Sudry, T.; Flaks-Manov, N.; Yehezkelli, Y.; Kalkstein, N.; Akiva, P.; Ekka-Zohar, A.; Ben David, S.S.; Lerner, U.; Bivas-Benita, M.; et al. Long covid outcomes at one year after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: Nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2023, 380, e072529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molteni, E.; Sudre, C.H.; Canas, L.S.; Bhopal, S.S.; Hughes, R.C.; Antonelli, M.; Murray, B.; Klaser, K.; Kerfoot, E.; Chen, L.; et al. Illness duration and symptom profile in symptomatic UK school-aged children tested for SARS-CoV-2. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morello, R.; Mariani, F.; Mastrantoni, L.; De Rose, C.; Zampino, G.; Munblit, D.; Sigfrid, L.; Valentini, P.; Buonsenso, D. Risk factors for post-COVID-19 condition (Long Covid) in children: A prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugawela, M.D.; Stephenson, T.; Shafran, R.; De Stavola, B.L.; Ladhani, S.N.; Simmons, R.; McOwat, K.; Rojas, N.; Dalrymple, E.; Cheung, E.Y.; et al. Predictive model for long COVID in children 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osmanov, I.M.; Spiridonova, E.; Bobkova, P.; Gamirova, A.; Shikhaleva, A.; Andreeva, M.; Blyuss, O.; El-Taravi, Y.; DunnGalvin, A.; Comberiati, P.; et al. Risk factors for post-COVID-19 condition in previously hospitalised children using the ISARIC Global follow-up protocol: A prospective cohort study. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 59, 2101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, S.; Krivchenia, K.; Eisner, M.; Young, B.; Ramilo, O.; Mejias, A.; Lee, S.; Kopp, B.T. Long-term pulmonary sequelae in adolescents post-SARS-CoV-2 infection. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2022, 57, 2455–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazukhina, E.; Andreeva, M.; Spiridonova, E.; Bobkova, P.; Shikhaleva, A.; El-Taravi, Y.; Rumyantsev, M.; Gamirova, A.; Bairashevskaia, A.; Petrova, P.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of post-COVID-19 condition in adults and children at 6 and 12 months after hospital discharge: A prospective, cohort study in Moscow (StopCOVID). BMC Med. 2022, 20, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto Pereira, S.M.; Nugawela, M.D.; Rojas, N.K.; Shafran, R.; McOwat, K.; Simmons, R.; Ford, T.; Heyman, I.; Ladhani, S.N.; Cheung, E.Y.; et al. Post-COVID-19 condition at 6 months and COVID-19 vaccination in non-hospitalised children and young people. Arch. Dis. Child. 2023, 108, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto Pereira, S.M.; Shafran, R.; Nugawela, M.D.; Panagi, L.; Hargreaves, D.; Ladhani, S.N.; Bennett, S.D.; Chalder, T.; Dalrymple, E.; Ford, T.; et al. Natural course of health and well-being in non-hospitalised children and young people after testing for SARS-CoV-2: A prospective follow-up study over 12 months. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2023, 25, 100554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roessler, M.; Tesch, F.; Batram, M.; Jacob, J.; Loser, F.; Weidinger, O.; Wende, D.; Vivirito, A.; Toepfner, N.; Ehm, F.; et al. Post-COVID-19-associated morbidity in children, adolescents, and adults: A matched cohort study including more than 157,000 individuals with COVID-19 in Germany. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1004122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roge, I.; Smane, L.; Kivite-Urtane, A.; Pucuka, Z.; Racko, I.; Klavina, L.; Pavare, J. Comparison of persistent symptoms after COVID-19 and other non-SARS-CoV-2 infections in children. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 752385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurada, Y.; Otsuka, Y.; Tokumasu, K.; Sunada, N.; Honda, H.; Nakano, Y.; Matsuda, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; Ochi, K.; Hagiya, H.; et al. Trends in Long COVID symptoms in Japanese teenage patients. Medicina 2023, 59, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seery, V.; Raiden, S.; Penedo, J.M.G.; Borda, M.; Herrera, L.; Uranga, M.; Marco Del Pont, M.; Chirino, C.; Erramuspe, C.; Alvarez, L.S.; et al. Persistent symptoms after COVID-19 in children and adolescents from Argentina. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 129, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, A.I.V.; Spiliopoulos, L.; Bager, P.; Nielsen, N.M.; Hansen, J.V.; Koch, A.; Meder, I.K.; Ethelberg, S.; Hviid, A. A nationwide questionnaire study of post-acute symptoms and health problems after SARS-CoV-2 infection in Denmark. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, T.; Pinto Pereira, S.M.; Shafran, R.; de Stavola, B.L.; Rojas, N.; McOwat, K.; Simmons, R.; Zavala, M.; O’Mahoney, L.; Chalder, T.; et al. Physical and mental health 3 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection (long COVID) among adolescents in England (CLoCk): A national matched cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2022, 6, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, T.; Pinto Pereira, S.M.; Nugawela, M.D.; McOwat, K.; Simmons, R.; Chalder, T.; Ford, T.; Heyman, I.; Swann, O.V.; Fox-Smith, L.; et al. Long COVID-six months of prospective follow-up of changes in symptom profiles of non-hospitalised children and young people after SARS-CoV-2 testing: A national matched cohort study (The CLoCk) study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0277704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, G.; Alarcon-Andrade, G.; Schulze-Schiapacasse, C.; Rodriguez, R.; Garcia-Salum, T.; Pardo-Roa, C.; Levican, J.; Serrano, E.; Avendano, M.J.; Gutierrez, M.; et al. Short-term complications and post-acute sequelae in hospitalized paediatric patients with COVID-19 and obesity: A multicenter cohort study. Pediatr. Obes. 2023, 18, e12980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren-Gash, C.; Lacey, A.; Cook, S.; Stocker, D.; Toon, S.; Lelii, F.; Ford, B.; Ireland, G.; Ladhani, S.N.; Stephenson, T.; et al. Post-COVID-19 condition and persisting symptoms in English schoolchildren: Repeated surveys to March 2022. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommen, S.L.; Havdal, L.B.; Selvakumar, J.; Einvik, G.; Leegaard, T.M.; Lund-Johansen, F.; Michelsen, A.E.; Mollnes, T.E.; Stiansen-Sonerud, T.; Tjade, T.; et al. Inflammatory markers and pulmonary function in adolescents and young adults 6 months after mild COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1081718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, E.; Cop, E.; Dinc, G.S.; Goker, Z.; Parlakay, A.O.; Demirel, B.D.; Mutlu, M.; Kirmizi, B. Loneliness, internalizing symptoms, and inflammatory markers in adolescent COVID-19 survivors. Child Care Health Dev. 2022, 48, 1112–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blankenburg, J.; Wekenborg, M.K.; Reichert, J.; Kirsten, C.; Kahre, E.; Haag, L.; Schumm, L.; Czyborra, P.; Berner, R.; Armann, J.P. Comparison of mental health outcomes in seropositive and seronegative adolescents during the COVID19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shachar-Lavie, I.; Shorer, M.; Segal, H.; Fennig, S.; Ashkenazi-Hoffnung, L. Mental health among children with long COVID during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erol, N.; Alpinar, A.; Erol, C.; Sari, E.; Alkan, K. Intriguing new faces of Covid-19: Persisting clinical symptoms and cardiac effects in children. Cardiol. Young 2022, 32, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatino, J.; Di Chiara, C.; Di Candia, A.; Sirico, D.; Dona, D.; Fumanelli, J.; Basso, A.; Pogacnik, P.; Cuppini, E.; Romano, L.R.; et al. Mid- and long-term atrio-ventricular functional changes in children after recovery from COVID-19. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 12, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, F.; Morello, R.; Traini, D.O.; La Rocca, A.; De Rose, C.; Valentini, P.; Buonsenso, D. Risk factors for persistent anosmia and dysgeusia in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection: A retrospective study. Children 2023, 10, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namazova-Baranova, L.; Karkashadze, G.; Zelenkova, I.; Vishneva, E.; Kaytukova, E.; Rusinova, D.; Ustinova, N.; Sergienko, N.; Nesterova, Y.; Yatsyk, L.; et al. A non-randomized comparative study of olfactory and gustatory functions in children who recovered from COVID-19 (1-year follow-up). Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 919061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusetsky, Y.; Meytel, I.; Mokoyan, Z.; Fisenko, A.; Babayan, A.; Malyavina, U. Smell status in children infected with SARS-CoV-2. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, E2475–E2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborators, C.-M.D. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoubkhani, D.; Bosworth, M.L.; King, S.; Pouwels, K.B.; Glickman, M.; Nafilyan, V.; Zaccardi, F.; Khunti, K.; Alwan, N.A.; Walker, A.S. Risk of Long COVID in people infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 after 2 doses of a coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine: Community-based, matched cohort study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Bowe, B.; Xie, Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzolini, E.; Levi, R.; Sarti, R.; Pozzi, C.; Mollura, M.; Mantovani, A.; Rescigno, M. Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and Long COVID after infections not requiring hospitalization in health care workers. JAMA 2022, 328, 676–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emecen, A.N.; Keskin, S.; Turunc, O.; Suner, A.F.; Siyve, N.; Basoglu Sensoy, E.; Dinc, F.; Kilinc, O.; Avkan Oguz, V.; Bayrak, S.; et al. The presence of symptoms within 6 months after COVID-19: A single-center longitudinal study. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 192, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meza-Torres, B.; Delanerolle, G.; Okusi, C.; Mayor, N.; Anand, S.; Macartney, J.; Gatenby, P.; Glampson, B.; Chapman, M.; Curcin, V.; et al. Differences in clinical presentation with Long COVID after community and hospital infection and associations with all-cause mortality: English sentinel network database study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 8, e37668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, M.; Penfold, R.S.; Merino, J.; Sudre, C.H.; Molteni, E.; Berry, S.; Canas, L.S.; Graham, M.S.; Klaser, K.; Modat, M.; et al. Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: A prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boufidou, F.; Medic, S.; Lampropoulou, V.; Siafakas, N.; Tsakris, A.; Anastassopoulou, C. SARS-CoV-2 Reinfections and Long COVID in the Post-Omicron Phase of the Pandemic. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).