Abstract

TOR and PKA signaling are the major growth-regulatory nutrient-sensing pathways in S. cerevisiae. A number of experimental findings demonstrated a close relationship between these pathways: Both are responsive to glucose availability. Both regulate ribosome production on the transcriptional level and repress autophagy and the cellular stress response. Sch9, a major downstream effector of TORC1 presumably shares its kinase consensus motif with PKA, and genetic rescue and synthetic defects between PKA and Sch9 have been known for a long time. Further, studies in the first decade of this century have suggested direct regulation of PKA by TORC1. Nonetheless, the contribution of a potential direct cross-talk vs. potential sharing of targets between the pathways has still not been completely resolved. What is more, other findings have in contrast highlighted an antagonistic relationship between the two pathways. In this review, I explore the association between TOR and PKA signaling, mainly by focusing on proteins that are commonly referred to as shared TOR and PKA targets. Most of these proteins are transcription factors which to a large part explain the major transcriptional responses elicited by TOR and PKA upon nutrient shifts. I examine the evidence that these proteins are indeed direct targets of both pathways and which aspects of their regulation are targeted by TOR and PKA. I further explore if they are phosphorylated on shared sites by PKA and Sch9 or when experimental findings point towards regulation via the PP2ASit4/PP2A branch downstream of TORC1. Finally, I critically review data suggesting direct cross-talk between the pathways and its potential mechanism.

1. Introduction

Protein kinase A (PKA) and TOR signaling are two highly conserved signaling pathways that respond to nutrient and stress signals and regulate various responses that govern cellular growth. Numerous findings indicate a strong connection between the pathways, but no clear picture of the nature of this interplay has emerged. This work aims to critically review the literature on shared targets and direct cross-talk and to point out gaps in current knowledge that hinder a better understanding. Beyond providing a resource about specifics of the signaling systems discussed, the described modes of interaction are intended to serve as examples relevant for understanding signaling interplay in a wider context. I will first provide a brief introduction to the PKA and TOR pathways to introduce the main players referred to subsequently. Then, I will give an overview of genetic data that link the pathways, before describing their major shared functions and substrates. Finally, I will discuss proposed direct cross-talk.

1.1. TOR Signaling

TOR signaling is one of the most central mechanisms that allows cells to adapt their growth to nutrient availability and also functions as a stress sensor. TOR signaling has been reviewed elsewhere [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] and therefore only a short summary is given here, in particular with respect to downstream functions that are shared with PKA signaling. The TOR functions explored in this review are mediated through TOR complex 1 (TORC1), and therefore “TOR signaling” will refer to signaling through TORC1 for the rest of this review. TORC1 exerts its physiological effects mainly through regulation of ribosome production, cell cycle progression and amino acid import and metabolism, as well as repression of autophagy and the cellular stress response [3,10].

Signaling downstream of TORC1 can be divided into two major branches, namely the PP2A and Sch9 branch. PP2A is a trimeric protein phosphatase, consisting of catalytic C subunit Pph21 or Pph22, scaffold A subunit Tpd3 and regulatory B subunit Cdc55 or Rts1 [12,13,14,15]. In addition, S. cerevisiae expresses a PP2A-like phosphatase (referred to as PP2ASit4), consisting of catalytic subunit Sit4 and either Sap155, Sap185 or Sap190 [16,17]. Both PP2A and PP2ASit4 activity are inhibited through Tap42 which forms complexes with Pph21/22 and Sit4 in a TORC1-dependent manner [18,19]. The tap42-11 mutant, which renders Tap42 temperature sensitive, but also rapamycin insensitive, is a frequently used experimental tool in this context [18]. When TORC1 is inactivated, PP2ASit4 induces a transcriptional program allowing the utilization of non-preferred nitrogen sources (among others through the transcription factors Gln3 and Gat1) and alters the profile of plasma membrane amino acid transporters [20,21,22,23].

The second major direct TORC1 target is the AGC kinase Sch9. Like other AGC kinases, it is basophilic and its limited number of known substrates suggest a preference for arginines and, to a lesser extent, lysines in the P-3 and P-2 positions [24,25]. It is phosphorylated by TORC1 on six serine and threonine residues near its C-terminus that reside within the so-called hydrophobic motif and turn motif [26]. In addition to the hydrophobic motif, AGC kinases generally require phosphorylation of their activation loop for full activity, which is catalyzed by the PDK1 homologs Pkh1/2 [27,28,29]. Sch9 is phylogenetically closely related to mammalian PKB/Akt and S6K [30] and, due to its ability to phosphorylate Rps6, is generally considered the functional homolog of S6K [26]. Several mechanisms through which Sch9 regulates ribosome biogenesis are discussed below.

1.2. PKA Signaling

PKA is a hetero-tetramer of two regulatory and two catalytic subunits. In S. cerevisiae, the regulatory subunit is encoded by BCY1 and the catalytic subunits by TPK1, TPK2 and TPK3, which are members of the AGC kinase family [31,32]. Specificity of PKA for phosphorylation of sites in R[RK]x[ST] (where x is any residue) motifs is well established [33,34]. Combinatorial deletions of the catalytic subunits demonstrated that only tpk1∆ tpk2∆ tpk3∆ strains are inviable, while the viability of double deletion strains suggests a high level of redundancy [31].

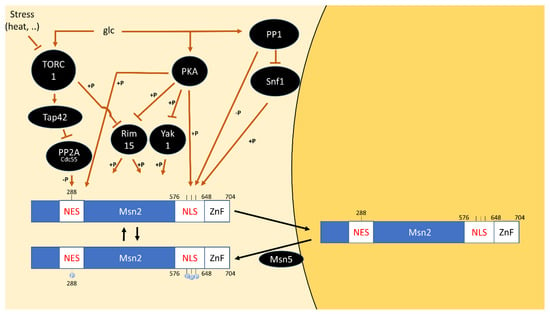

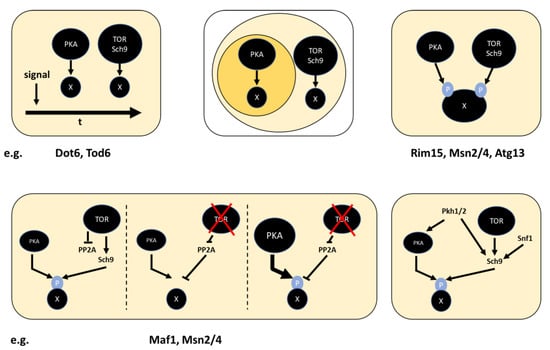

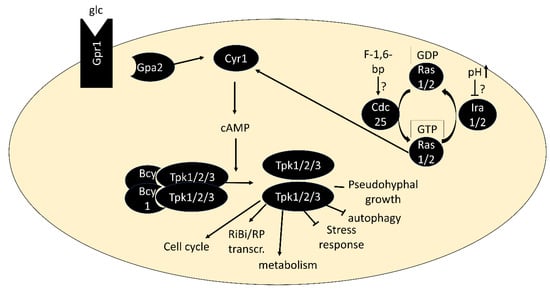

PKA is activated by the binding of cAMP to the regulatory subunits, triggering their dissociation from the catalytic subunits [35]. The second messenger cAMP is produced by adenylate cyclase Cyr1, which is activated via two routes: First, by the small G proteins Ras1 or Ras2, which are regulated by the guanine-nucleotide exchange factor Cdc25 and GTPase-activating proteins Ira1/2, and second via the G protein-coupled receptor Gpr1 and its G protein alpha subunit Gpa2 [36,37] (Figure 1). Both pathways are best known for their activation by glucose when added to cultures without a fermentable carbon source [38,39,40]. The low-affinity, high-capacity phosphodiesterase Pde1 and a high-affinity, low-capacity phosphodiesterase Pde2 are responsible for cAMP degradation [41,42]. Through upregulation of Pde1 activity and other negative feedback loops, the PKA pathway dampens its activity within minutes after glucose addition, resulting in a characteristic cAMP spike [43]. While glucose-triggered activation is the by far most studied scenario, activation of PKA in a cAMP-independent manner [44] and in response to nitrogen and other nutrients [45,46] has also been described. There is an increasing number of examples in which conveying the presence of these nutrients to PKA depends on nutrient transceptors, transporters that serve a role in signaling (see [47] for a review). PKA is also phosphorylated by the PDK homologs Pkh1/2 and undergoes autophosphorylation, but our understanding of the regulatory roles of these modifications is limited [48,49].

Figure 1.

Core components of the PKA pathway. In its inactive form, PKA exists as a tetramer of two regulatory subunits (Bcy1) and two catalytic subunits (Tpk1, Tpk2 or Tpk3). Binding of cAMP to Bcy1 leads to dissociation of the complex and activation of the catalytic subunits. Two main routes of activation of adenylate cyclase Cyr1 exist: via the G protein-coupled receptor Gpr1 and its G protein alpha subunit Gpa2 and via the small GTPases Ras1/2.

Important tools for studying PKA are strains in which the pathway is artificially activated, through BCY1 deletion or a single amino acid substitution in Ras1/2 (rasV19). These strains fail to grow on non-fermentable carbon sources and to accumulate storage carbohydrates, arrest in G0 or acquire heat-shock resistance like wild-type strains upon nutrient deprivation [32,50,51,52]. Growth of bcy1∆ strains on non-fermentable carbon sources is restored by deletion of any two of the TPK genes and a point-mutation of the third, denoted as tpkw (“wimpy”). These mutants were isolated from spontaneous revertants of strains carrying deletions of BCY1 and two TPK genes, which formed papillations after the parent strains had exhausted glucose on agar plates [53]. They form important tools for study as their remaining PKA activity can no longer be regulated by cAMP binding to Bcy1. Their capacity to accumulate glycogen upon nutrient exhaustion and utilize it upon nutrient repletion must therefore rely on signaling other than through PKA or on PKA regulation independent of cAMP [53].

Similar to TOR signaling, PKA has been implicated in the positive regulation of ribosome biogenesis and cell cycle progression and the repression of autophagy and the cellular stress response. It is also involved in pseudo-hyphal growth and meiosis. Further, PKA plays a major role in the regulation of metabolism; however, unlike for TOR signaling, this mainly evolves around the storage carbohydrates glycogen and trehalose, glycolysis and gluconeogenesis [1,11,54,55]. Several substrates regulated through direct phosphorylation by PKA have been identified [56,57,58,59].

Intriguingly, the inviability of the tpk1∆ tpk2∆ tpk3∆ triple deletion strain can be rescued by the additional deletion of YAK1, RIM15 or double deletion of MSN2 and MSN4 [60,61,62]. All these proteins, which are direct PKA substrates, play important roles in communicating stress signals and sending cells into quiescence, indicating that repression of these responses is the only essential PKA function [5,61,63,64,65].

Yak1, Msn2/4 and Rim15 are connected in a number of ways: while Yak1 phosphorylates and positively regulates Msn2/4 [66,67], Msn2/4 are conversely required for transcription of the YAK1 gene [62]. Similarly, Rim15 also appears to phosphorylate Msn2/4 and Rim15-dependent regulation of gene expression is to a large extent explained by Msn2/4 [68,69].

The interconnectivity between the three factors may explain why the removal of any of them is sufficient to restore viability of the tpk1∆ tpk2∆ tpk3∆ triple deletion strain. The fact that abolishing stress-induced anti-growth functions, is sufficient for viability of PKA-null strains, while its role in positively regulating growth is dispensable, prompts the question if another pathway supports growth in this context. TOR signaling is an obvious candidate and we will start exploring the relationship between the pathways by discussing the literature reporting their genetic interaction.

2. TOR–PKA Genetic Interactions

Findings about a genetic interaction between the TOR and PKA pathways pre-date even the discovery of TOR signaling itself, as overexpression of Sch9—later determined as the main TORC1 effector kinase—rescued a temperature-sensitive mutation of Cdc25 and deletions of components of the PKA pathway, including the catalytic subunits [70]. An overview of the many subsequently reported genetic interactions is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genetic interactions of PKA and TOR signaling.

After the discovery of TOR signaling, a series of experiments in the mid-2000s using rapamycin further strengthened the connection between PKA and TOR signaling: Deletion of BCY1 or overexpression of Cdc25, Tpk1 or an activated version of Ras (rasV19), all increased rapamycin resistance. These observations were most obvious in a gat1Δ gln3Δ background, indicating that PKA has the clearest effect on rescuing TOR inhibition when repression of the nitrogen discrimination pathway was rescued by independent means [71].

The gat1Δ gln3Δ mutations were, however, not strictly necessary, as deletion of IRA2 or BCY1 or the ras2V19 mutation caused rapamycin resistance in an otherwise wt strain, while deletion of RAS2 or of PKA catalytic subunits conferred rapamycin sensitivity [72].

Are these data consistent with a model in which PKA regulates TOR signaling or vice versa in a linear pathway? As the rescuing factor must act downstream or in parallel with the rescued factor, Sch9 should function downstream of PKA to rescue mutations in the PKA pathway, if assuming a linear connection [70]. In contrast, PKA should function downstream of TORC1 according to Schmelzle, 2004 [71] and Zurita-Martinez, 2005 [72]. The latter is not completely compelling, as temperature-sensitive or rapamycin-dependent inhibition may be incomplete and hyperactivation of an upstream function may alleviate a diminished downstream function. However, Toda, 1988 had also reported that hyperactivation of PKA via BCY1 deletion rescued the growth defect of sch9∆-strains [70].

It is therefore clear that a linear connection between PKA and TOR signaling cannot explain the experimental observations, and instead, a parallel placement of the pathways may be assumed. Independent of the wiring, all of the above studies reported a positive interaction between TOR and PKA signaling.

Conversely, antagonistic interactions have also been described: Araki et al. identified Pde2 and Bcy1 as suppressors of a temperature-sensitive mutation in the TORC1 subunit KOG1 (aka LAS24) [73]. A later study found that genetic manipulations activating the PKA pathway (bcy1∆ and expression of rasV19) increased rapamycin sensitivity, while ras1Δ ras2-23 mutants and cells overexpressing PDE2 were rapamycin resistant [74]. The latter also rescued the temperature sensitivity of a tor2-ts mutant, while the rasV19 mutation caused synthetic growth defects with partial inhibition of TORC1.

Therefore, the same genetic manipulations, bcy1∆ and expression of rasV19 from a single copy plasmid, lead to opposite outcomes in the studies by Zurita-Martinez et al. 2005 [72] and Ramachandran and Herman 2011 [74]: rapamycin resistance vs. rapamycin sensitivity. In addition to the use of different strain backgrounds, the major difference between the experiments was the use of different rapamycin concentrations, with at least ten times less in the latter study. It is interesting to note that this study observed increased phosphorylation of known PKA substrates upon rapamycin treatment, albeit on a timescale of hours [74]. As will be detailed below, there is in contrast ample evidence for reduced phosphorylation of substrates shared by PKA and TORC1/Sch9 upon rapamycin treatment.

I propose a model in which the main interaction between TOR and PKA signaling is positive via shared substrates, but a second layer of weak mutual inhibition also exists. The latter may arise due to feedback from shared substrates. If one pathway is already deleted or strongly inhibited, further loss of input to the shared targets through inhibition of the second pathway will result in lethality or severe growth defects. In contrast, if, for example, TORC1 is only mildly inhibited (e.g., via low rapamycin), the activity of shared targets will be lowered, but sufficient to support growth when also PKA signaling is reduced (e.g., by PDE2 overexpression). Negative feedback to TORC1 will be reduced, alleviating effects on TOR-unique targets and therefore resulting in rapamycin resistance. An analogous model may explain the observation that trehalase activity, generally considered a PKA-unique readout, was increased upon SCH9 deletion [75]. Further work will be needed to test the proposed antagonistic/feedback effects. Signaling through shared functions and targets, which is, in contrast, more firmly established, will be discussed next.

4. Substrate Specificity of PKA and Sch9

Up to now, I discussed how PKA and TOR signaling converge on shared substrates. It is, however, similarly important to ask how specificity is achieved for substrates that are not shared. Two phospho-proteomics studies obtained clear indications that the prevalence of shared substrates is extensive, based on the finding that the PKA motif R[R/K]x[S/T] [161,162] was enriched among sites hypo-phosphorylated upon rapamycin treatment [25,133]. Importantly, however, not all known PKA targets were affected by rapamycin treatment, which was validated for a subset [25]. Similarly, we found that some, but not all sites hypo-phosphorylated upon PKA inhibition were also hypo-phosphorylated upon Sch9 inhibition [163]. No bona fide unique Sch9 site is known to date and the sites shared with PKA reside in the R[R/K]x[S/T] motif [94,120]. (In contrast, proteins downstream of TORC1, but not PKA (e.g., Npr1, Gat1, Gln3, Rtg1 [18,22,164]), are connected to TORC1 is via PP2A/PP2ASit4 rather than Sch9.) The question, therefore, becomes, how PKA can achieve specificity for other sites with the same motif, such as in Pfk26 [56], Nth1 [58,165], Cki1 [166], Adr1 [167] and Ssn2/Srb9 [168]. If differences in substrate motifs of PKA and Sch9 do not explain why some targets are exclusively phosphorylated by PKA, different localization of the kinases relative to their targets may be invoked. Sch9 is present both in association with the vacuolar membrane and dispersed throughout the cytoplasm [26,169,170] and a recent study detected pools of Sch9 at additional locations, including the plasma membrane and nucleo-vacuolar junction [171]. As discussed below, our understanding of the subcellular localizations of PKA is still far from complete, but it is at least partially found in the cytoplasm. As also several substrates unique to PKA (e.g., Nth1, Pfk26), mainly localize to the cytoplasm [170], localization of the kinases does not appear to be the explanation for specificity, unless we were to assume that they are only active at a subset of locations. For example, one might propose that Sch9 is mainly active at the vacuolar membrane, where TORC1 resides, and PKA mainly in the vicinity of Cyr1.

5. Potential Mechanisms of TOR–PKA Interplay

Having explored how PKA and TOR signaling interact via shared targets, we will now return to discussing a potential more direct cross-talk between the pathways. As pointed out in an earlier section, the regulation of one pathway by the other is not sufficient to explain experimental observations. However, this does not rule out that such cross-talk may exist in addition to convergence on shared substrates. TOR was initially discovered by the Hall lab via a genetic screen for spontaneous rapamycin-insensitive mutants, leading to the identification of the target-of-rapamycin kinases Tor1 and Tor2 [172]. In subsequent years, knowledge about TOR signaling and its response to the availability of nitrogen sources grew and its suppression of the transcription factors Gln3 and Gat1 was described [22]. In a later study, the same lab asked if further rapamycin-insensitive mutants could be detected in a gln3Δ gat1Δ background and several genetic manipulations hyperactivating PKA signaling (rasV19 mutation, CDC25 or TPK1 overexpression) were found to further increase rapamycin resistance [71]. Based on this, they proposed a model in which TORC1 acts as an upstream activator of PKA. While none of their data could distinguish between this model and convergence of TOR and PKA signaling on shared substrates, they observed that rapamycin treatment caused Tpk1 nuclear localization, and therefore, a mechanism by which TOR may regulate PKA. This rapamycin-induced nuclear localization was reproduced later, with the additional observation that SCH9 deletion resembles the effect of rapamycin treatment in this respect [25]. It was also noted that mutations that abolish Tpk1-Bcy1 interaction prevented rapamycin-induced Tpk1 nuclear localization. This suggests that nuclear Tpk1 is bound and inhibited by Bcy1 [25].

The model of TORC1 regulating PKA gained support through a subsequent study: Martin et al. showed that hyperactivation of PKA prohibited rapamycin-induced nuclear translocation of the RP gene repressor Crf1 and that PKA inactivation led to nuclear translocation without the need for rapamycin [104] (see above). These data rule out a connection of PKA and TORC1 to Crf1 via a strict AND or strict OR gate, but may be explained by a more elaborate mechanism, such as shown in Figure 7 on a negative regulator of Crf1. Importantly, however, the same work further found that phosphorylation by Yak1 appears responsible for Crf1 translocation and that Yak1 is activated in presence of rapamycin. This argues for TORC1 acting at the level or upstream of Yak1. Notably, Schmelzle et al. had observed that YAK1 deletion is equivalent to PKA hyperactivation with respect to overcoming Gat1-Gln3-independent rapamycin effects [71]. The fact that Yak1 has been described to be inactivated by direct phosphorylation by PKA [63,65,173], but not been reported as a TORC1 or Sch9 target, supports TORC1 dependent regulation of PKA. While the model appears compelling, the absence of detectable Yak1 dephosphorylation upon rapamycin treatment is at odds with it [25]. Additionally, as pointed out earlier, the role of Crf1 on RP gene transcription was found to be yeast strain-specific [110] and a potential second mechanism may exist for its regulation. While this does not invalidate the model, it emphasizes existing gaps in our current understanding. The idea of TORC1-dependent PKA localization has also not gained widespread acceptance. In contrast to the findings described above, several other studies detected Tpk1 in the nucleus of glucose-grown cells (in the absence of rapamycin) [148,174,175]. Growth with glycerol as the sole carbon source [174] or into stationary phase [149,175] resulted in partial re-localization to the cytoplasm. Available data on Tpk2 and Tpk3 also lean towards nuclear localization under beneficial and cytoplasmic (possibly P-body or stress granule) localization under nutrient-limited conditions [174,175]. While in these cases cytoplasmic localization corresponds to the inactive state of PKA, Griffioen et al. reported Tpk1 cytoplasmic localization when treating a cyr1∆ strain with cAMP [149]. A model that rationalizes these differing observations on Tpk1 localization is lacking to date. If TOR signaling indeed activates PKA, it would be expected that nitrogen source or amino acid availability, stimuli that positively regulate TORC1 [176,177,178], also influence PKA activity. Indeed, activation of the PKA target trehalase upon addition of a nitrogen source has been demonstrated and apparently occurs in a cAMP-independent manner [46,179,180]. As this upregulation of trehalase activity additionally requires the presence of a fermentable carbon source, the proposed nitrogen source-dependent, but cAMP-independent PKA activation was referred to as the “fermentable-growth-medium induced pathway”. This concept would be consistent with TOR-dependent regulation of PKA. More recent findings point towards nitrogen source and amino acid-dependent PKA activation via nutrient transceptors and under certain conditions, most notably the addition of L-citrulline to nitrogen-starved cells, TORC1 activity was found dispensable [45,47]. While this is not inconsistent with additional activation by TORC1, it alleviates the need for positing this mechanism.

6. Conclusions

There exists compelling evidence for a tight interplay between TOR and PKA signaling, based on genetic findings and the phosphorylation state of known targets. However, genetic evidence also clearly demonstrates that the pathways are not purely epistatic. Based on the best-understood shared targets presented in this review, it is apparent that each point of convergence between the pathways needs to be considered individually. While in some cases the phospho sites targeted by the two pathways are distinct, with TORC1-dependent sites sometimes dephosphorylated by PP2A/PP2ASit4, in other cases the phospho sites are shared between PKA and Sch9 which exhibit similar substrate specificity. The mechanistic basis for some substrates being shared between the two AGC kinases and others being unique to PKA remains an important question to resolve. The review of each of these individual targets also points out that much remains to be learned about how TOR and PKA regulate even these best-understood common targets. In addition, some observations have led to the proposal of a more direct cross-talk between the pathways. While TOR signaling appears like an upstream regulator of PKA based on nucleo-cytoplasmic localization of PKA subunits and on the regulation of Yak1, a better understanding of the mechanism of this proposed cross-talk is required to lend credibility to its existence. Finally, we understand little about the physiological role of the interplay between the two major growth-regulatory pathways. The simple model, according to which PKA solely responds to carbon source availability and TOR to amino acid and nitrogen availability, has increasingly eroded in recent years. Instead, it now becomes important to ask how and why different environmental conditions impact the output of each individual pathway and their interplay.

Funding

This work was funded through a University of Arizona BIO5 Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I thank the members of the Capaldi lab (University of Arizona) for critical reading of the manuscript and the BIO5 institute of the University of Arizona for support through a BIO5 Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Zaman, S.; Lippman, S.I.; Zhao, X.; Broach, J.R. How Saccharomyces Responds to Nutrients. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008, 42, 27–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broach, J.R. Nutritional Control of Growth and Development in Yeast. Genetics 2012, 192, 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewith, R.; Hall, M.N. Target of Rapamycin (TOR) in Nutrient Signaling and Growth Control. Genetics 2011, 189, 1177–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltschinger, S.; Loewith, R. TOR Complexes and the Maintenance of Cellular Homeostasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Virgilio, C. The Essence of Yeast Quiescence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 306–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Hall, M.N. Nutrient Sensing and TOR Signaling in Yeast and Mammals. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Virgilio, C.; Loewith, R. The TOR Signalling Network from Yeast to Man. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006, 38, 1476–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoki, K.; Guan, K.-L. Complexity of the TOR Signaling Network. Trends Cell Biol. 2006, 16, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulard, A.; Cohen, A.; Hall, M.N. TOR Signaling in Invertebrates. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009, 21, 825–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Virgilio, C.; Loewith, R. Cell Growth Control: Little Eukaryotes Make Big Contributions. Oncogene 2006, 25, 6392–6415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M.; Schothorst, J.; Kankipati, H.N.; Van Zeebroeck, G.; Rubio-Texeira, M.; Thevelein, J.M. Nutrient Sensing and Signaling in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 254–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, A.M.; Zolnierowicz, S.; Stapleton, A.E.; Goebl, M.; DePaoli-Roach, A.A.; Pringle, J.R. CDC55, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gene Involved in Cellular Morphogenesis: Identification, Characterization, and Homology to the B Subunit of Mammalian Type 2A Protein Phosphatase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991, 11, 5767–5780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Van Zyl, W.; Huang, W.; Sneddon, A.A.; Stark, M.; Camier, S.; Werner, M.; Marck, C.; Sentenac, A.; Broach, J.R. Inactivation of the Protein Phosphatase 2A Regulatory Subunit A Results in Morphological and Transcriptional Defects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992, 12, 4946–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shu, Y.; Yang, H.; Hallberg, E.; Hallberg, R. Molecular Genetic Analysis of Rts1p, a B’ Regulatory Subunit of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Protein Phosphatase 2A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997, 17, 3242–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, A.A.; Cohen, P.T.; Stark, M.J. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Protein Phosphatase 2A Performs an Essential Cellular Function and Is Encoded by Two Genes. EMBO J. 1990, 9, 4339–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, A.; Immanuel, D.; Arndt, K.T. The SIT4 Protein Phosphatase Functions in Late G1 for Progression into S Phase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991, 11, 2133–2148. [Google Scholar]

- Luke, M.M.; Della Seta, F.; Di Como, C.J.; Sugimoto, H.; Kobayashi, R.; Arndt, K.T. The SAP, a New Family of Proteins, Associate and Function Positively with the SIT4 Phosphatase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996, 16, 2744–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Como, C.J.; Arndt, K.T. Nutrients, via the Tor Proteins, Stimulate the Association of Tap42 with Type 2A Phosphatases. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Broach, J.R. Tor Proteins and Protein Phosphatase 2A Reciprocally Regulate Tap42 in Controlling Cell Growth in Yeast. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 2782–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T.G. Transmitting the Signal of Excess Nitrogen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae from the Tor Proteins to the GATA Factors: Connecting the Dots. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 26, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, M.E.; Cutler, N.S.; Lorenz, M.C.; Di Como, C.J.; Heitman, J. The TOR Signaling Cascade Regulates Gene Expression in Response to Nutrients. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 3271–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Hall, M.N. The TOR Signalling Pathway Controls Nuclear Localization of Nutrient-Regulated Transcription Factors. Nature 1999, 402, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Beck, T.; Koller, A.; Kunz, J.; Hall, M.N. The TOR Nutrient Signalling Pathway Phosphorylates NPR1 and Inhibits Turnover of the Tryptophan Permease. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 6924–6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

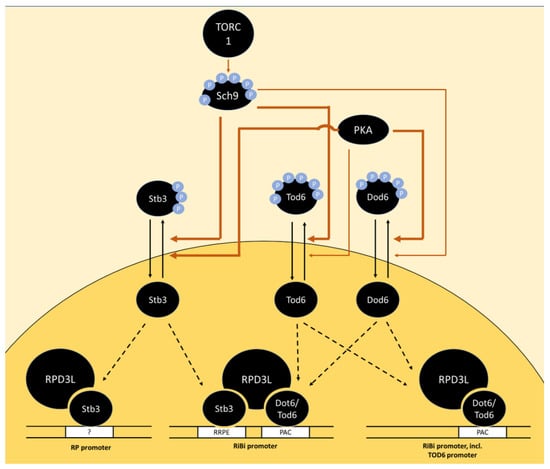

- Huber, A.; French, S.L.; Tekotte, H.; Yerlikaya, S.; Stahl, M.; Perepelkina, M.P.; Tyers, M.; Rougemont, J.; Beyer, A.L.; Loewith, R. Sch9 Regulates Ribosome Biogenesis via Stb3, Dot6 and Tod6 and the Histone Deacetylase Complex RPD3L. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 3052–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulard, A.; Cremonesi, A.; Moes, S.; Schütz, F.; Jenö, P.; Hall, M.N. The Rapamycin-Sensitive Phosphoproteome Reveals That TOR Controls Protein Kinase A toward Some but Not All Substrates. Mol. Biol. Cell 2010, 21, 3475–3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.; Soulard, A.; Huber, A.; Lippman, S.; Mukhopadhyay, D.; Deloche, O.; Wanke, V.; Anrather, D.; Ammerer, G.; Riezman, H.; et al. Sch9 Is a Major Target of TORC1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 2007, 26, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, L.R.; Komander, D.; Alessi, D.R. The Nuts and Bolts of AGC Protein Kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, X.; Lester, R.L.; Dickson, R.C. The Sphingoid Long Chain Base Phytosphingosine Activates AGC-Type Protein Kinases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Including Ypk1, Ypk2, and Sch9. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 22679–22687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casamayor, A.; Torrance, P.D.; Kobayashi, T.; Thorner, J.; Alessi, D.R. Functional Counterparts of Mammalian Protein Kinases PDK1 and SGK in Budding Yeast. Curr. Biol. CB 1999, 9, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, T.J.P.; Zwartkruis, F.J.T.; Bos, J.L.; Snel, B. Evolution of the TOR Pathway. J. Mol. Evol. 2011, 73, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, T.; Cameron, S.; Sass, P.; Zoller, M.; Wigler, M. Three Different Genes in S. Cerevisiae Encode the Catalytic Subunits of the CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Cell 1987, 50, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, T.; Cameron, S.; Sass, P.; Zoller, M.; Scott, J.D.; McMullen, B.; Hurwitz, M.; Krebs, E.G.; Wigler, M. Cloning and Characterization of BCY1, a Locus Encoding a Regulatory Subunit of the Cyclic AMP-Dependent Protein Kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987, 7, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, B.E.; Bylund, D.B.; Huang, T.S.; Krebs, E.G. Substrate Specificity of the Cyclic AMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 3448–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabb, J.B. Physiological Substrates of CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 2381–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Uno, I.; Oshima, Y.; Ishikawa, T. Isolation and Characterization of Yeast Mutants Deficient in Adenylate Cyclase and CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 2355–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraakman, L.; Lemaire, K.; Ma, P.; Teunissen, A.W.; Donaton, M.C.; Van Dijck, P.; Winderickx, J.; de Winde, J.H.; Thevelein, J.M. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae G-Protein Coupled Receptor, Gpr1, Is Specifically Required for Glucose Activation of the CAMP Pathway during the Transition to Growth on Glucose. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 32, 1002–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatchell, K.; Chaleff, D.T.; DeFeo-Jones, D.; Scolnick, E.M. Requirement of Either of a Pair of Ras-Related Genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for Spore Viability. Nature 1984, 309, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazón, M.J.; Gancedo, J.M.; Gancedo, C. Inactivation of Yeast Fructose-1,6-Bisphosphatase. In Vivo Phosphorylation of the Enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 1128–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwin, C.; Leidig, F.; Holzer, H. Cyclic AMP-Dependent Phosphorylation of Fructose-1,6-Bisphosphatase in Yeast. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1982, 107, 1482–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevelein, J.M. Fermentable Sugars and Intracellular Acidification as Specific Activators of the RAS-Adenylate Cyclase Signalling Pathway in Yeast: The Relationship to Nutrient-Induced Cell Cycle Control. Mol. Microbiol. 1991, 5, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikawa, J.; Sass, P.; Wigler, M. Cloning and Characterization of the Low-Affinity Cyclic AMP Phosphodiesterase Gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987, 7, 3629–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sass, P.; Field, J.; Nikawa, J.; Toda, T.; Wigler, M. Cloning and Characterization of the High-Affinity CAMP Phosphodiesterase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 9303–9307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, P.; Wera, S.; Van Dijck, P.; Thevelein, J.M. The PDE1-Encoded Low-Affinity Phosphodiesterase in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Has a Specific Function in Controlling Agonist-Induced CAMP Signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peeters, T.; Louwet, W.; Gelade, R.; Nauwelaers, D.; Thevelein, J.M.; Versele, M. Kelch-Repeat Proteins Interacting with the G Protein Gpa2 Bypass Adenylate Cyclase for Direct Regulation of Protein Kinase A in Yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 13034–13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conrad, M.; Kankipati, H.N.; Kimpe, M.; Van Zeebroeck, G.; Zhang, Z.; Thevelein, J.M. The Nutrient Transceptor/PKA Pathway Functions Independently of TOR and Responds to Leucine and Gcn2 in a TOR-Independent Manner. FEMS Yeast Res. 2017, 17, fox048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevelein, J.M.; Beullens, M. Cyclic AMP and the Stimulation of Trehalase Activity in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by Carbon Sources, Nitrogen Sources and Inhibitors of Protein Synthesis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1985, 131, 3199–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyfkens, F.; Zhang, Z.; Van Zeebroeck, G.; Thevelein, J.M. Multiple Transceptors for Macro- and Micro-Nutrients Control Diverse Cellular Properties Through the PKA Pathway in Yeast: A Paradigm for the Rapidly Expanding World of Eukaryotic Nutrient Transceptors up to Those in Human Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesendonckx, S.; Tudisca, V.; Voordeckers, K.; Moreno, S.; Thevelein, J.M.; Portela, P. The Activation Loop of PKA Catalytic Isoforms Is Differentially Phosphorylated by Pkh Protein Kinases in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. J. 2012, 448, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steichen, J.M.; Iyer, G.H.; Li, S.; Saldanha, S.A.; Deal, M.S.; Woods, V.L.; Taylor, S.S. Global Consequences of Activation Loop Phosphorylation on Protein Kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 3825–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M.S.; Gibbs, J.B.; Scolnick, E.M.; Sigal, I.S. Regulatory Function of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAS C-Terminus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987, 7, 2309–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, J.F.; Tatchell, K. Characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Genes Encoding Subunits of Cyclic AMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987, 7, 2653–2663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Uno, I.; Ishikawa, T. Control of Cell Division in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mutants Defective in Adenylate Cyclase and CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Exp. Cell Res. 1983, 146, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, S.; Levin, L.; Zoller, M.; Wigler, M. CAMP-Independent Control of Sporulation, Glycogen Metabolism, and Heat Shock Resistance in S. Cerevisiae. Cell 1988, 53, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, I.; Matsumoto, K.; Ishikawa, T. Characterization of a Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterase-Deficient Mutant in Yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 3539–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, G.M. Glucose Signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2006, 70, 253–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dihazi, H.; Kessler, R.; Eschrich, K. Glucose-Induced Stimulation of the Ras-CAMP Pathway in Yeast Leads to Multiple Phosphorylations and Activation of 6-Phosphofructo-2-Kinase. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 6275–6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, P.; Howell, S.; Moreno, S.; Rossi, S. In Vivo and in Vitro Phosphorylation of Two Isoforms of Yeast Pyruvate Kinase by Protein Kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 30477–30487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, W.; Van Zeebroeck, G.; Pinkse, M.; Verhaert, P.; Thevelein, J.M. In Vivo Phosphorylation of Ser21 and Ser83 during Nutrient-Induced Activation of the Yeast Protein Kinase A (PKA) Target Trehalase. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 44130–44142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittenhouse, J.; Moberly, L.; Marcus, F. Phosphorylation in Vivo of Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Fructose-1,6-Bisphosphatase at the Cyclic AMP-Dependent Site. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 10114–10119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, S.; Broach, J. Loss of Ras Activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Is Suppressed by Disruptions of a New Kinase Gene, YAKI, Whose Product May Act Downstream of the CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Genes Dev. 1989, 3, 1336–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, A.; Bürckert, N.; Boller, T.; Wiemken, A.; De Virgilio, C. Saccharomyces cerevisiae CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase Controls Entry into Stationary Phase through the Rim15p Protein Kinase. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 2943–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.; Ward, M.P.; Garrett, S. Yeast PKA Represses Msn2p/Msn4p-Dependent Gene Expression to Regulate Growth, Stress Response and Glycogen Accumulation. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 3556–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, S.; Menold, M.M.; Broach, J.R. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae YAK1 Gene Encodes a Protein Kinase That Is Induced by Arrest Early in the Cell Cycle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991, 11, 4045–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Görner, W.; Durchschlag, E.; Martinez-Pastor, M.T.; Estruch, F.; Ammerer, G.; Hamilton, B.; Ruis, H.; Schüller, C. Nuclear Localization of the C2H2 Zinc Finger Protein Msn2p Is Regulated by Stress and Protein Kinase A Activity. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Paik, S.-M.; Shin, C.-S.; Huh, W.-K.; Hahn, J.-S. Regulation of Yeast Yak1 Kinase by PKA and Autophosphorylation-Dependent 14-3-3 Binding. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 79, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Cho, B.-R.; Joo, H.-S.; Hahn, J.-S. Yeast Yak1 Kinase, a Bridge between PKA and Stress-Responsive Transcription Factors, Hsf1 and Msn2/Msn4. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 70, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcher, M.; Schladebeck, S.; Mösch, H.-U. The Yak1 Protein Kinase Lies at the Center of a Regulatory Cascade Affecting Adhesive Growth and Stress Resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2011, 187, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

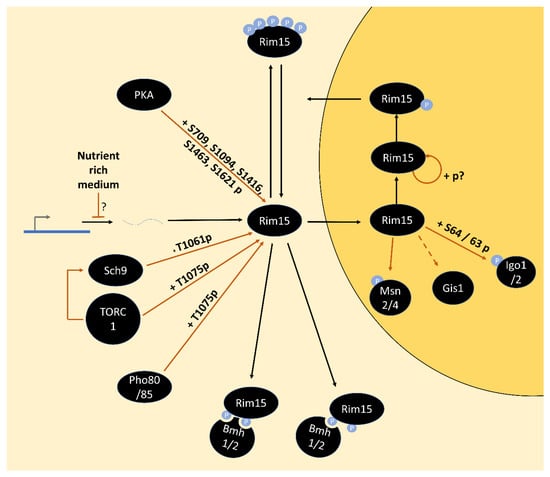

- Lee, P.; Kim, M.S.; Paik, S.-M.; Choi, S.-H.; Cho, B.-R.; Hahn, J.-S. Rim15-Dependent Activation of Hsf1 and Msn2/4 Transcription Factors by Direct Phosphorylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 3648–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameroni, E.; Hulo, N.; Roosen, J.; Winderickx, J.; De Virgilio, C. The Novel Yeast PAS Kinase Rim 15 Orchestrates G0-Associated Antioxidant Defense Mechanisms. Cell Cycle 2004, 3, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, T.; Cameron, S.; Sass, P.; Wigler, M. SCH9, a Gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae That Encodes a Protein Distinct from, but Functionally and Structurally Related to, CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase Catalytic Subunits. Genes Dev. 1988, 2, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelzle, T.; Beck, T.; Martin, D.E.; Hall, M.N. Activation of the RAS/Cyclic AMP Pathway Suppresses a TOR Deficiency in Yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurita-Martinez, S.A.; Cardenas, M.E. Tor and Cyclic AMP-Protein Kinase A: Two Parallel Pathways Regulating Expression of Genes Required for Cell Growth. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, T.; Uesono, Y.; Oguchi, T.; Toh-E, A. LAS24/KOG1, a Component of the TOR Complex 1 (TORC1), Is Needed for Resistance to Local Anesthetic Tetracaine and Normal Distribution of Actin Cytoskeleton in Yeast. Genes Genet. Syst. 2005, 80, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, V.; Herman, P.K. Antagonistic Interactions between the CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase and Tor Signaling Pathways Modulate Cell Growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2011, 187, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crauwels, M.; Donaton, M.C.; Pernambuco, M.B.; Winderickx, J.; de Winde, J.H.; Thevelein, J.M. The Sch9 Protein Kinase in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Controls CAPK Activity and Is Required for Nitrogen Activation of the Fermentable-Growth-Medium-Induced (FGM) Pathway. Microbiology 1997, 143, 2627–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra, D.; Warner, J.R. What Better Measure than Ribosome Synthesis? Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 2431–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.R. The Economics of Ribosome Biosynthesis in Yeast. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999, 24, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasch, A.P.; Spellman, P.T.; Kao, C.M.; Carmel-Harel, O.; Eisen, M.B.; Storz, G.; Botstein, D.; Brown, P.O. Genomic Expression Programs in the Response of Yeast Cells to Environmental Changes. Mol. Biol. Cell 2000, 11, 4241–4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, P.; Rupes, I.; Sharom, J.R.; Schneper, L.; Broach, J.R.; Tyers, M. A Dynamic Transcriptional Network Communicates Growth Potential to Ribosome Synthesis and Critical Cell Size. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 2491–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, M.G.; Heideman, W. Coordinated Regulation of Growth Genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pierce, M.; Schneper, L.; Güldal, C.G.; Zhang, X.; Tavazoie, S.; Broach, J.R. Ras and Gpa2 Mediate One Branch of a Redundant Glucose Signaling Pathway in Yeast. PLoS Biol. 2004, 2, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaman, S.; Lippman, S.I.; Schneper, L.; Slonim, N.; Broach, J.R. Glucose Regulates Transcription in Yeast through a Network of Signaling Pathways. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009, 5, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunkel, J.; Luo, X.; Capaldi, A.P. Integrated TORC1 and PKA Signaling Control the Temporal Activation of Glucose-Induced Gene Expression in Yeast. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosio, M.C.; Fermi, B.; Spagnoli, G.; Levati, E.; Rubbi, L.; Ferrari, R.; Pellegrini, M.; Dieci, G. Abf1 and Other General Regulatory Factors Control Ribosome Biogenesis Gene Expression in Budding Yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 4493–4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingerman, I.; Nagaraj, V.; Norris, D.; Vershon, A.K. Sfp1 Plays a Key Role in Yeast Ribosome Biogenesis. Eukaryot. Cell 2003, 2, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dequard-Chablat, M.; Riva, M.; Carles, C.; Sentenac, A. RPC19, the Gene for a Subunit Common to Yeast RNA Polymerases A (I) and C (III). J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 15300–15307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.D.; Estep, P.W.; Tavazoie, S.; Church, G.M. Computational Identification of Cis-Regulatory Elements Associated with Groups of Functionally Related Genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 296, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liko, D.; Slattery, M.G.; Heideman, W. Stb3 Binds to Ribosomal RNA Processing Element Motifs That Control Transcriptional Responses to Growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 26623–26628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, E.L.; Shamji, A.F.; Bernstein, B.E.; Schreiber, S.L. Rpd3p Relocation Mediates a Transcriptional Response to Rapamycin in Yeast. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdistani, S.K.; Robyr, D.; Tavazoie, S.; Grunstein, M. Genome-Wide Binding Map of the Histone Deacetylase Rpd3 in Yeast. Nat. Genet. 2002, 31, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, J.R.; Cardenas, M.E. The Tor Pathway Regulates Gene Expression by Linking Nutrient Sensing to Histone Acetylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippman, S.I.; Broach, J.R. Protein Kinase A and TORC1 Activate Genes for Ribosomal Biogenesis by Inactivating Repressors Encoded by Dot6 and Its Homolog Tod6. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19928–19933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes Hallett, J.E.; Luo, X.; Capaldi, A.P. State Transitions in the TORC1 Signaling Pathway and Information Processing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2014, 198, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, A.; Bodenmiller, B.; Uotila, A.; Stahl, M.; Wanka, S.; Gerrits, B.; Aebersold, R.; Loewith, R. Characterization of the Rapamycin-Sensitive Phosphoproteome Reveals That Sch9 Is a Central Coordinator of Protein Synthesis. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 1929–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deminoff, S.J.; Howard, S.C.; Hester, A.; Warner, S.; Herman, P.K. Using Substrate-Binding Variants of the CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase to Identify Novel Targets and a Kinase Domain Important for Substrate Interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2006, 173, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasten, M.M.; Stillman, D.J. Identification of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Genes STB1-STB5 Encoding Sin3p Binding Proteins. Mol. Gen. Genet. MGG 1997, 256, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budovskaya, Y.V.; Stephan, J.S.; Deminoff, S.J.; Herman, P.K. An Evolutionary Proteomics Approach Identifies Substrates of the CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 13933–13938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liko, D.; Conway, M.K.; Grunwald, D.S.; Heideman, W. Stb3 Plays a Role in the Glucose-Induced Transition from Quiescence to Growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2010, 185, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, T.; Walter, P. Regulation of Ribosome Biogenesis by the Rapamycin-Sensitive TOR-Signaling Pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 1999, 10, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.B.; Wade, J.T.; Struhl, K. An HMG Protein, Hmo1, Associates with Promoters of Many Ribosomal Protein Genes and throughout the RRNA Gene Locus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 3672–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schawalder, S.B.; Kabani, M.; Howald, I.; Choudhury, U.; Werner, M.; Shore, D. Growth-Regulated Recruitment of the Essential Yeast Ribosomal Protein Gene Activator Ifh1. Nature 2004, 432, 1058–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudra, D.; Zhao, Y.; Warner, J.R. Central Role of Ifh1p-Fhl1p Interaction in the Synthesis of Yeast Ribosomal Proteins. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, J.T.; Hall, D.B.; Struhl, K. The Transcription Factor Ifh1 Is a Key Regulator of Yeast Ribosomal Protein Genes. Nature 2004, 432, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, D.E.; Soulard, A.; Hall, M.N. TOR Regulates Ribosomal Protein Gene Expression via PKA and the Forkhead Transcription Factor FHL1. Cell 2004, 119, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lempiäinen, H.; Uotila, A.; Urban, J.; Dohnal, I.; Ammerer, G.; Loewith, R.; Shore, D. Sfp1 Interaction with TORC1 and Mrs6 Reveals Feedback Regulation on TOR Signaling. Mol. Cell 2009, 33, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, C.; Struhl, K. Protein Kinase A Mediates Growth-Regulated Expression of Yeast Ribosomal Protein Genes by Modulating RAP1 Transcriptional Activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14, 1920–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosio, M.C.; Negri, R.; Dieci, G. Promoter Architectures in the Yeast Ribosomal Expression Program. Transcription 2011, 2, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sanctis, V.; La Terra, S.; Bianchi, A.; Shore, D.; Burderi, L.; Di Mauro, E.; Negri, R. In Vivo Topography of Rap1p-DNA Complex at Saccharomyces cerevisiae TEF2 UAS(RPG) during Transcriptional Regulation. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 318, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durocher, D.; Jackson, S.P. The FHA Domain. FEBS Lett. 2002, 513, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; McIntosh, K.B.; Rudra, D.; Schawalder, S.; Shore, D.; Warner, J.R. Fine-Structure Analysis of Ribosomal Protein Gene Transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 4853–4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Hahn, J.-S. Role of CK2-Dependent Phosphorylation of Ifh1 and Crf1 in Transcriptional Regulation of Ribosomal Protein Genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Gene Regul. Mech. 2016, 1859, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudra, D.; Mallick, J.; Zhao, Y.; Warner, J.R. Potential Interface between Ribosomal Protein Production and Pre-RRNA Processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 4815–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, P.; Nishikawa, J.L.; Breitkreutz, B.-J.; Tyers, M. Systematic Identification of Pathways That Couple Cell Growth and Division in Yeast. Science 2002, 297, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, B.; Kos-Braun, I.C.; Henras, A.K.; Dez, C.; Rueda, M.P.; Zhang, X.; Gadal, O.; Kos, M.; Shore, D. A Ribosome Assembly Stress Response Regulates Transcription to Maintain Proteome Homeostasis. eLife 2019, 8, e45002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion, R.M.; Regev, A.; Segal, E.; Barash, Y.; Koller, D.; Friedman, N.; O’Shea, E.K. Sfp1 Is a Stress- and Nutrient-Sensitive Regulator of Ribosomal Protein Gene Expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 14315–14322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, K.; Lefebvre, O.; Martin, N.C.; Smagowicz, W.J.; Stanford, D.R.; Ellis, S.R.; Hopper, A.K.; Sentenac, A.; Boguta, M. Maf1p, a Negative Effector of RNA Polymerase III in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 5031–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhya, R.; Lee, J.; Willis, I.M. Maf1 Is an Essential Mediator of Diverse Signals That Repress RNA Polymerase III Transcription. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

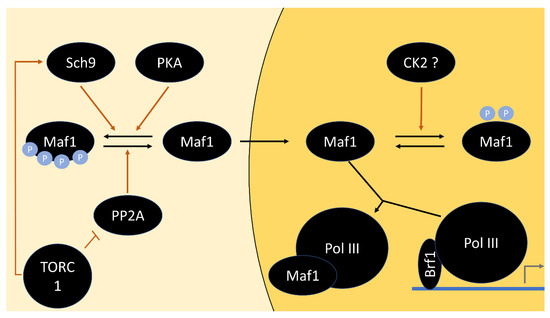

- Moir, R.D.; Lee, J.; Haeusler, R.A.; Desai, N.; Engelke, D.R.; Willis, I.M. Protein Kinase A Regulates RNA Polymerase III Transcription through the Nuclear Localization of Maf1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 15044–15049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.N.; Wilson, B.; Huff, J.T.; Stewart, A.J.; Cairns, B.R. Dephosphorylation and Genome-Wide Association of Maf1 with Pol III-Transcribed Genes during Repression. Mol. Cell 2006, 22, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Moir, R.D.; Willis, I.M. Regulation of RNA Polymerase III Transcription Involves SCH9-Dependent and SCH9-Independent Branches of the Target of Rapamycin (TOR) Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 12604–12608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oficjalska-Pham, D.; Harismendy, O.; Smagowicz, W.J.; Gonzalez de Peredo, A.; Boguta, M.; Sentenac, A.; Lefebvre, O. General Repression of RNA Polymerase III Transcription Is Triggered by Protein Phosphatase Type 2A-Mediated Dephosphorylation of Maf1. Mol. Cell 2006, 22, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noda, T.; Ohsumi, Y. Tor, a Phosphatidylinositol Kinase Homologue, Controls Autophagy in Yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 3963–3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, Y.; Funakoshi, T.; Shintani, T.; Nagano, K.; Ohsumi, M.; Ohsumi, Y. Tor-Mediated Induction of Autophagy via an Apg1 Protein Kinase Complex. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 150, 1507–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budovskaya, Y.V.; Stephan, J.S.; Reggiori, F.; Klionsky, D.J.; Herman, P.K. The Ras/CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase Signaling Pathway Regulates an Early Step of the Autophagy Process in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 20663–20671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorimitsu, T.; Zaman, S.; Broach, J.R.; Klionsky, D.J. Protein Kinase A and Sch9 Cooperatively Regulate Induction of Autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 4180–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

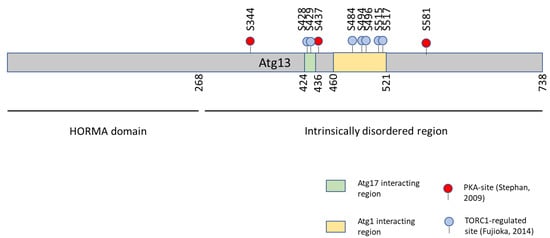

- Stephan, J.S.; Yeh, Y.-Y.; Ramachandran, V.; Deminoff, S.J.; Herman, P.K. The Tor and PKA Signaling Pathways Independently Target the Atg1/Atg13 Protein Kinase Complex to Control Autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17049–17054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funakoshi, T.; Matsuura, A.; Noda, T.; Ohsumi, Y. Analyses of APG13 Gene Involved in Autophagy in Yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 1997, 192, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeya, Y.; Noda, N.N.; Fujioka, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Inagaki, F.; Ohsumi, Y. Characterization of the Atg17-Atg29-Atg31 Complex Specifically Required for Starvation-Induced Autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 389, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, Y.; Suzuki, S.W.; Yamamoto, H.; Kondo-Kakuta, C.; Kimura, Y.; Hirano, H.; Akada, R.; Inagaki, F.; Ohsumi, Y.; Noda, N.N. Structural Basis of Starvation-Induced Assembly of the Autophagy Initiation Complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Kirisako, T.; Kamada, Y.; Mizushima, N.; Noda, T.; Ohsumi, Y. The Pre-Autophagosomal Structure Organized by Concerted Functions of APG Genes Is Essential for Autophagosome Formation. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 5971–5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kundu, M.; Viollet, B.; Guan, K.-L. AMPK and MTOR Regulate Autophagy through Direct Phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamada, Y.; Yoshino, K.; Kondo, C.; Kawamata, T.; Oshiro, N.; Yonezawa, K.; Ohsumi, Y. Tor Directly Controls the Atg1 Kinase Complex to Regulate Autophagy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Raucci, S.; Jaquenoud, M.; Hatakeyama, R.; Stumpe, M.; Rohr, R.; Reggiori, F.; De Virgilio, C.; Dengjel, J. Multilayered Control of Protein Turnover by TORC1 and Atg1. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 3486–3496.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farré, J.-C.; Subramani, S. Mechanistic Insights into Selective Autophagy Pathways: Lessons from Yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidan, S.; Mitchell, A.P. Stimulation of Yeast Meiotic Gene Expression by the Glucose-Repressible Protein Kinase Rim15p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997, 17, 2688–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, V.; Moradas-Ferreira, P. Oxidative Stress and Signal Transduction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Insights into Ageing, Apoptosis and Diseases. Mol. Aspects Med. 2001, 22, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedruzzi, I.; Bürckert, N.; Egger, P.; De Virgilio, C. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ras/CAMP Pathway Controls Post-Diauxic Shift Element-Dependent Transcription through the Zinc Finger Protein Gis1. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 2569–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarek, N.; Cameroni, E.; Jaquenoud, M.; Luo, X.; Bontron, S.; Lippman, S.; Devgan, G.; Snyder, M.; Broach, J.R.; De Virgilio, C. Initiation of the TORC1-Regulated G0 Program Requires Igo1/2, Which License Specific MRNAs to Evade Degradation via the 5’-3’ MRNA Decay Pathway. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Talarek, N.; De Virgilio, C. Initiation of the Yeast G0 Program Requires Igo1 and Igo2, Which Antagonize Activation of Decapping of Specific Nutrient-Regulated MRNAs. RNA Biol. 2011, 8, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanes, M.A.; Khoueiry, R.; Kupka, T.; Castro, A.; Mudrak, I.; Ogris, E.; Lorca, T.; Piatti, S. Budding Yeast Greatwall and Endosulfines Control Activity and Spatial Regulation of PP2A(Cdc55) for Timely Mitotic Progression. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talarek, N.; Gueydon, E.; Schwob, E. Homeostatic Control of START through Negative Feedback between Cln3-Cdk1 and Rim15/Greatwall Kinase in Budding Yeast. eLife 2017, 6, e26233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbet, N.C.; Schneider, U.; Helliwell, S.B.; Stansfield, I.; Tuite, M.F.; Hall, M.N. TOR Controls Translation Initiation and Early G1 Progression in Yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 1996, 7, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanke, V.; Cameroni, E.; Uotila, A.; Piccolis, M.; Urban, J.; Loewith, R.; De Virgilio, C. Caffeine Extends Yeast Lifespan by Targeting TORC1. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 69, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedruzzi, I.; Dubouloz, F.; Cameroni, E.; Wanke, V.; Roosen, J.; Winderickx, J.; De Virgilio, C. TOR and PKA Signaling Pathways Converge on the Protein Kinase Rim15 to Control Entry into G0. Mol. Cell 2003, 12, 1607–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, N.; DeRisi, J.; Brown, P.O. New Components of a System for Phosphate Accumulation and Polyphosphate Metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Revealed by Genomic Expression Analysis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2000, 11, 4309–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, B.L.; Lagerstedt, J.O.; Pratt, J.R.; Pattison-Granberg, J.; Lundh, K.; Shokrollahzadeh, S.; Lundh, F. Regulation of Phosphate Acquisition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 2003, 43, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanke, V.; Pedruzzi, I.; Cameroni, E.; Dubouloz, F.; De Virgilio, C. Regulation of G0 Entry by the Pho80-Pho85 Cyclin-CDK Complex. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 4271–4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.L.; Zhulin, I.B. PAS Domains: Internal Sensors of Oxygen, Redox Potential, and Light. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. MMBR 1999, 63, 479–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, G.; Anghileri, P.; Imre, E.; Baroni, M.D.; Ruis, H. Nutritional Control of Nucleocytoplasmic Localization of CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase Catalytic and Regulatory Subunits in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, G.; Thevelein, J.M. Molecular Mechanisms Controlling the Localisation of Protein Kinase A. Curr. Genet. 2002, 41, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, F.; Carlson, M. Two Homologous Zinc Finger Genes Identified by Multicopy Suppression in a SNF1 Protein Kinase Mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993, 13, 3872–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treger, J.M.; Schmitt, A.P.; Simon, J.R.; McEntee, K. Transcriptional Factor Mutations Reveal Regulatory Complexities of Heat Shock and Newly Identified Stress Genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 26875–26879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Pastor, M.T.; Marchler, G.; Schüller, C.; Marchler-Bauer, A.; Ruis, H.; Estruch, F. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Zinc Finger Proteins Msn2p and Msn4p Are Required for Transcriptional Induction through the Stress Response Element (STRE). EMBO J. 1996, 15, 2227–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, A.P.; McEntee, K. Msn2p, a Zinc Finger DNA-Binding Protein, Is the Transcriptional Activator of the Multistress Response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 5777–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Görner, W.; Durchschlag, E.; Wolf, J.; Brown, E.L.; Ammerer, G.; Ruis, H.; Schüller, C. Acute Glucose Starvation Activates the Nuclear Localization Signal of a Stress-Specific Yeast Transcription Factor. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Düvel, K.; Santhanam, A.; Garrett, S.; Schneper, L.; Broach, J.R. Multiple Roles of Tap42 in Mediating Rapamycin-Induced Transcriptional Changes in Yeast. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhanam, A.; Hartley, A.; Düvel, K.; Broach, J.R.; Garrett, S. PP2A Phosphatase Activity Is Required for Stress and Tor Kinase Regulation of Yeast Stress Response Factor Msn2p. Eukaryot. Cell 2004, 3, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, W.; Klopf, E.; De Wever, V.; Anrather, D.; Petryshyn, A.; Roetzer, A.; Niederacher, G.; Roitinger, E.; Dohnal, I.; Görner, W.; et al. Yeast Protein Phosphatase 2A-Cdc55 Regulates the Transcriptional Response to Hyperosmolarity Stress by Regulating Msn2 and Msn4 Chromatin Recruitment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wever, V.; Reiter, W.; Ballarini, A.; Ammerer, G.; Brocard, C. A Dual Role for PP1 in Shaping the Msn2-Dependent Transcriptional Response to Glucose Starvation. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 4115–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.-Y.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Sheu, J.-C.; Wu, J.-T.; Lee, F.-J.; Chen, Y.; Lin, M.-I.; Chiang, F.-T.; Tai, T.-Y.; Berger, S.L.; et al. Acetylation of Yeast AMPK Controls Intrinsic Aging Independently of Caloric Restriction. Cell 2011, 146, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, B.E.; Graves, D.J.; Benjamini, E.; Krebs, E.G. Role of Multiple Basic Residues in Determining the Substrate Specificity of Cyclic AMP-Dependent Protein Kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1977, 252, 4888–4894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, J.; Kim, P.M.; Lam, H.Y.K.; Piccirillo, S.; Zhou, X.; Jeschke, G.R.; Sheridan, D.L.; Parker, S.A.; Desai, V.; Jwa, M.; et al. Deciphering Protein Kinase Specificity through Large-Scale Analysis of Yeast Phosphorylation Site Motifs. Sci. Signal. 2010, 3, ra12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plank, M.; Perepelkina, M.; Müller, M.; Vaga, S.; Zou, X.; Bourgoint, C.; Berti, M.; Saarbach, J.; Haesendonckx, S.; Winssinger, N.; et al. Chemical Genetics of AGC-Kinases Reveals Shared Targets of Ypk1, Protein Kinase A and Sch9. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP 2020, 19, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, J.L.; Daicho, K.; Ushimaru, T.; Hall, M.N. The GATA Transcription Factors GLN3 and GAT1 Link TOR to Salt Stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 34441–34444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veisova, D.; Macakova, E.; Rezabkova, L.; Sulc, M.; Vacha, P.; Sychrova, H.; Obsil, T.; Obsilova, V. Role of Individual Phosphorylation Sites for the 14-3-3-Protein-Dependent Activation of Yeast Neutral Trehalase Nth1. Biochem. J. 2012, 443, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yu, Y.; Sreenivas, A.; Ostrander, D.B.; Carman, G.M. Phosphorylation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Choline Kinase on Ser30 and Ser85 by Protein Kinase A Regulates Phosphatidylcholine Synthesis by the CDP-Choline Pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 34978–34986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, J.R.; Johnson, T.R.; Dollard, C.; Shuster, J.R.; Denis, C.L. Cyclic AMP-Dependent Protein Kinase Phosphorylates and Inactivates the Yeast Transcriptional Activator ADR1. Cell 1989, 56, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-W.; Howard, S.C.; Herman, P.K. The Ras/PKA Signaling Pathway Directly Targets the Srb9 Protein, a Component of the General RNA Polymerase II Transcription Apparatus. Mol. Cell 2004, 15, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, E.; Jin, N.; Itakura, E.; Kira, S.; Kamada, Y.; Weisman, L.S.; Noda, T.; Matsuura, A. Vacuole-Mediated Selective Regulation of TORC1-Sch9 Signaling Following Oxidative Stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 2018, 29, 510–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, W.-K.; Falvo, J.V.; Gerke, L.C.; Carroll, A.S.; Howson, R.W.; Weissman, J.S.; O’Shea, E.K. Global Analysis of Protein Localization in Budding Yeast. Nature 2003, 425, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cottignie, I.; Van Zeebroeck, G.; Thevelein, J.M. Nutrient Transceptors Physically Interact with the Yeast S6/Protein Kinase B Homolog, Sch9, a TOR Kinase Target. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitman, J.; Movva, N.; Hall, M. Targets for Cell Cycle Arrest by the Immunosuppressant Rapamycin in Yeast. Science 1991, 253, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriya, H.; Shimizu-Yoshida, Y.; Omori, A.; Iwashita, S.; Katoh, M.; Sakai, A. Yak1p, a DYRK Family Kinase, Translocates to the Nucleus and Phosphorylates Yeast Pop2p in Response to a Glucose Signal. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Shen, Y.; Gao, W.; Dong, J. Role of Sch9 in Regulating Ras-CAMP Signal Pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 3026–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudisca, V.; Recouvreux, V.; Moreno, S.; Boy-Marcotte, E.; Jacquet, M.; Portela, P. Differential Localization to Cytoplasm, Nucleus or P-Bodies of Yeast PKA Subunits under Different Growth Conditions. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 89, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracka, D.; Jozefczuk, S.; Rudroff, F.; Sauer, U.; Hall, M.N. Nitrogen Source Activates TOR (Target of Rapamycin) Complex 1 via Glutamine and Independently of Gtr/Rag Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 25010–25020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamji, A.F.; Kuruvilla, F.G.; Schreiber, S.L. Partitioning the Transcriptional Program Induced by Rapamycin among the Effectors of the Tor Proteins. Curr. Biol. 2000, 10, 1574–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komeili, A.; Wedaman, K.P.; O’Shea, E.K.; Powers, T. Mechanism of Metabolic Control. Target of Rapamycin Signaling Links Nitrogen Quality to the Activity of the Rtg1 and Rtg3 Transcription Factors. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 151, 863–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirimburegama, K.; Durnez, P.; Keleman, J.; Oris, E.; Vergauwen, R.; Mergelsberg, H.; Thevelein, J.M. Nutrient-Induced Activation of Trehalase in Nutrient-Starved Cells of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: CAMP Is Not Involved as Second Messenger. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1992, 138, 2035–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durnez, P.; Pernambuco, M.B.; Oris, E.; Argüelles, J.C.; Mergelsberg, H.; Thevelein, J.M. Activation of Trehalase during Growth Induction by Nitrogen Sources in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Depends on the Free Catalytic Subunits of CAMP-Dependent Protein Kinase, but Not on Functional Ras Proteins. Yeast 1994, 10, 1049–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).