Abstract

The core of power system planning lies in optimizing resource portfolios to ensure reliable electricity supply, with generalized adequacy serving as a key indicator of supply security. As the share of renewable energy increases, the mechanisms underlying system security undergo profound changes, extending the concept of adequacy from mere power balance to encompass flexibility and inertia support while exhibiting spatial and temporal heterogeneity and wide-area characteristics. Traditional planning approaches can no longer meet these evolving requirements. To address this, a power grid coordinated planning framework is proposed based on generalized adequacy, which integrates power and energy adequacy, flexibility adequacy, and inertia adequacy. Within this framework, generalized adequacy metrics and their quantification methods are developed, and a coordinated planning strategy for wind power, photovoltaic power, multi-timescale energy storage, and transmission expansion is introduced to enhance renewable energy utilization and meet flexibility needs across multiple timescales. Furthermore, a scheme evaluation and selection method based on generalized adequacy is proposed. Finally, the effectiveness of the proposed approach is validated through case studies on the IEEE 24-bus system.

1. Introduction

With the increasing demands of economic and social development, coupled with stringent environmental protection requirements, the large-scale integration of renewable energy into power systems has become a global consensus among governments and grid operators [1,2,3]. Compared to conventional thermal power, which provides stable and reliable output, renewable energy generation is highly sensitive to extreme weather conditions and exhibits pronounced seasonal variations. These characteristics exacerbate the complexity of multi-timescale power and energy balancing in modern power systems, further underscoring the need for enhanced system flexibility [4]. Additionally, as the share of renewable energy continues to grow, the decline in system operational inertia has emerged as a critical concern, making dynamic frequency stability a key objective in power system planning [5]. In light of these challenges, traditional grid planning methodologies are increasingly inadequate in accommodating the evolving distribution of energy resources and transmission network structures. This necessitates an urgent revision of planning frameworks and evaluation criteria to facilitate the large-scale integration of renewable energy sources.

Adequacy, as a fundamental prerequisite for the stable and reliable operation of power systems, remains a core consideration in the planning phase. Conventional grid planning approaches primarily focus on thermal power, hydropower, and transmission infrastructure, typically ensuring adequacy by requiring that the total installed capacity of thermal power units exceeds the forecasted load by a predefined margin. However, as the share of renewable energy continues to expand, this criterion is becoming increasingly unreliable. The inherent seasonal variability and short-term stochastic nature of renewable energy generation exacerbate supply–demand imbalances, rendering traditional capacity-based adequacy assessments insufficient [6]. Moreover, the short-term fluctuations of renewable energy amplify net load volatility, necessitating substantial ramping resources to maintain system stability. Furthermore, as synchronous generators are progressively supplanted by inertia-free renewable sources, the system’s ability to provide inertial support continues to diminish, elevating the risk of large-scale frequency excursions. Consequently, it is imperative to extend the traditional concept of adequacy, which has historically focused on capacity adequacy, toward a more comprehensive framework that integrates power and energy adequacy, flexibility adequacy, and inertia adequacy.

To address these emerging trends, scholars worldwide have been actively investigating power system adequacy evaluation methodologies, grid planning strategies, and scheme comparison techniques. In the context of adequacy evaluation metrics, the international organization ESIG, in its latest report, emphasized the urgent need to update the conventional Loss of Load Expectation (LOLE) metric and its 0.1 d/a criterion. It advocates for the adoption of a multi-metric framework that integrates Expected Energy Not Served (EENS) alongside additional risk indicators to enhance reliability assessments [7]. The academic community has explored various methodologies to assess adequacy in the context of large-scale renewable energy integration. For instance, in [8], the authors extended the traditional adequacy assessment, which was originally based on available generating capacity, by incorporating primary energy supply constraints and multiple energy carriers, utilizing penalty functions and a multi-level energy flow model. Similarly, in [9], researchers incorporated generator reserve capacity and transmission power flow constraints into adequacy evaluations, further integrating wind turbine ramping limitations, specifically the Ramp Power Limit (RPL) and Ramp Rate Limit (RRL), within a second-order cone programming (SOCP) framework. In the domains of system flexibility and inertia evaluation, numerous indicators have been proposed to address the evolving challenges of renewable-dominated power systems. For example, in [10], a comprehensive flexibility assessment framework was developed, incorporating key statistical indicators such as flexibility shortage probability, expectation, duration, and quantiles, which were built upon conventional power and energy adequacy metrics. In [11], a probabilistic approach was introduced to define Insufficient Ramp Resource Probability (IRRP) and Insufficient Ramp Resource Expectation (IRRE) as quantitative flexibility indicators. Furthermore, ref. [12] introduced the concept of an inertia security region (ISR) and proposed a set of novel metrics, including the inertia security region aspect ratio, inertia security margin, and inertia reserve coefficient, to characterize the ISR and quantitatively assess system inertia. In addition, ref. [13] proposed four frequency security assessment metrics and established their correlation with system inertia, providing a robust framework for frequency stability analysis.

With regard to power grid planning methodologies and scheme comparisons, substantial research has been conducted on the coordinated planning of renewable energy, energy storage, and transmission networks in future power systems [14,15]. For example, ref. [16] proposed a chance-constrained transmission expansion planning approach that explicitly accounts for load demand and wind power uncertainty, optimizing the trade-off between economic efficiency and system reliability. In [17], a distributed robust optimization model was formulated to minimize transmission expansion costs under uncertainty while maximizing renewable energy penetration. Recognizing that most transmission expansion studies overlook the need for system flexibility optimization to address the variability of renewable energy. Additionally, ref. [18] developed an enhanced binary particle swarm optimization (BPSO) algorithm to solve the security-constrained transmission expansion planning problem, demonstrating its effectiveness through case studies. In terms of scheme comparison methodologies, extensive research has been conducted on various multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) techniques. Among these, commonly employed weighting methods include the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) [19], the entropy weight method [20], and the grey comprehensive evaluation method [21]. Moreover, ranking-based approaches such as the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) and the Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluations (PROMETHEE-II) [22] have been widely adopted for scheme selection, providing systematic and robust decision-making frameworks.

The primary limitation of the aforementioned studies is their fragmented treatment of adequacy across different dimensions, including power and energy adequacy, flexibility adequacy, and inertia adequacy, without ensuring consistency in resource planning. This lack of integration impedes the holistic enhancement of adequacy across all dimensions, thereby limiting the overall reliability and stability of modern power systems. To address this gap, this paper proposes a comprehensive grid planning methodology based on generalized adequacy, enabling the coordinated planning and optimization of renewable energy, short-term and long-term energy storage, and transmission infrastructure. The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 introduces the concept of generalized adequacy, establishes the corresponding evaluation metrics, and develops a systematic assessment methodology. Section 3 presents a comprehensive grid planning and scheme comparison approach based on generalized adequacy, aimed at effectively enhancing the adequacy level while facilitating scheme selection. Section 4 validates the proposed methodology through a case study using an enhanced IEEE 24-bus system.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

- Building upon conventional adequacy theories, this study introduces a generalized adequacy framework that integrates power and energy adequacy, flexibility adequacy, and inertia adequacy. To align with the evolving requirements of grid planning, seven generalized adequacy indicators are identified and employed for evaluation.

- (2)

- A novel grid planning methodology based on generalized adequacy is proposed, enabling the coordinated optimization of wind power, photovoltaic power, short-term and long-term energy storage, and transmission infrastructure. This approach effectively enhances the system’s generalized adequacy, ensuring a balanced and resilient power system design.

- (3)

- A planning scheme comparison framework incorporating generalized adequacy is developed, facilitating a systematic evaluation of alternative planning schemes. The proposed method enables a comparative analysis based on economic efficiency, generalized adequacy, renewable energy accommodation capacity, and carbon reduction effectiveness, ultimately guiding the selection of the optimal planning scheme.

2. Generalized Adequacy Theory and Its Evaluation Metrics

2.1. Transition from Traditional Adequacy to Generalized Adequacy

In conventional power system resource planning, adequacy requirements are generally considered met as long as the total installed generation capacity exceeds the system’s peak load by a predefined margin [23,24,25]. However, with the increasing penetration of high-proportion renewable energy and the growing complexity of demand-side dynamics, power system planning must now extend beyond capacity adequacy to encompass flexibility adequacy and dynamic frequency security, necessitating corresponding investments in additional resources. Whether considering traditional capacity adequacy or the emerging dimensions of flexibility adequacy and inertia adequacy, the planning process exhibits the following key characteristics:

- (1)

- Adequacy across all dimensions manifests externally as the ability of supply to meet system-wide demand.

- (2)

- Future system requirements must be addressed through the planned allocation of specific resources, as control-based measures alone cannot provide additional supply capacity to meet operational demands.

- (3)

- The dynamic matching of supply and demand is fundamentally realized through the transmission of electrical energy. While traditional adequacy ensures that total energy supply meets demand, flexibility adequacy fundamentally requires that the ramping capabilities of various resources are sufficient to track fluctuations in load-side demand. In terms of inertia adequacy, although the inertia support capability of thermal power units is independent of energy transfer, the virtual inertia effect provided by new resources such as renewables and energy storage depends on their energy output. Consequently, the realization of power and energy adequacy, flexibility adequacy, and inertia adequacy fundamentally relies on the effective transmission of electrical energy within the system.

Based on the above considerations, the traditional adequacy concept is extended, and a generalized adequacy framework is proposed, which integrates power and energy adequacy, flexibility adequacy, and inertia adequacy. This concept encompasses the supply–demand matching processes across various time scales in power systems, including inertia response and frequency response at the millisecond-to-second level, flexibility supply–demand balancing at the minute-to-hour level, and power and energy balance at the daily-to-annual scale. At the core of this framework lies the assessment of whether dynamic matching between system supply capabilities and demand is maintained across different timescales, with corresponding evaluation metrics systematically reflecting this adequacy.

2.2. Generalized Adequacy Evaluation Metrics and Quantification Methods

To evaluate whether a given planning scheme satisfies the required system operational conditions, it is essential to determine whether the proposed scheme’s evaluation metrics comply with the standards established by grid operators or relevant regulatory institutions. For example, in the context of traditional adequacy indicators, the United States commonly employs the LOLE metric, with a standard threshold of 0.1 d/a [26], whereas European countries typically adopt a similar approach using the Loss of Load Hours (LOLH) metric, with a standard threshold of 3 h/a [7]. To effectively incorporate the concept of generalized adequacy into grid planning, seven evaluation metrics are proposed along with their corresponding assessment methodologies, building upon internationally recognized adequacy indicators. These metrics are designed to systematically quantify the generalized adequacy level of planning schemes, ensuring a robust and comprehensive evaluation framework.

2.2.1. Power and Energy Adequacy Metrics

As discussed earlier, the LOLH metric is one of the most widely used indicators for power and energy adequacy, providing a probabilistic measure of supply shortages. Additionally, the Expected Energy Not Served (EENS) metric is commonly employed to quantify the magnitude of energy deficiencies during shortage events. To further account for the impact of low-probability, high-impact events—such as extreme weather conditions and geological disasters—financial risk metrics, including Value at Risk (VaR) and Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR), have been increasingly adopted in power system assessments [7]. Specifically, EENS denotes the expected value of the energy that the system is unable to supply to meet load demand within a given time period. represents the mean value of EENS corresponding to the most severe part of the EENS probability distribution across all evaluated events. As highlighted in [7], future power and energy adequacy assessment methodologies should satisfy the following three key requirements: (1) expanding from single-metric evaluation to a multi-metric framework; (2) incorporating indicators that measure the severity of load loss events; and (3) considering the impact of extreme events. Based on a comprehensive review of existing metrics, their advantages, and application needs, three evaluation indicators are introduced: LOLH, EENS, and the CVaR value of EENS, denoted as . The calculation methods are as follows:

where represents the LOLH, an adequacy evaluation metric for power and energy adequacy; denotes the total number of assessment scenario years; represents the total number of days in scenario year ; is the sign function, which equals 1 when a loss-of-load event occurs; denotes the system load at time on day in scenario year ; represents the total available generation capacity at time on day in scenario year ; represents the EENS; represents the Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR) of EENS; represents the proportion of extreme event scenarios considered, typically set at 5%; refers to the Value at Risk of ; is the probability density function. The LOLH metric primarily characterizes the average number of hours per year in which energy shortages occur, with units of h/a. EENS represents the annual average unmet energy demand, measured in MWh. In contrast, quantifies the average expected loss of load for the worst-case scenario years under extreme weather events such as heatwaves with low wind conditions, cold waves, and prolonged droughts. This metric is used to assess the potential risks posed by extreme events to power system energy supply.

In terms of assessment methodology, sequential Monte Carlo sampling is employed, incorporating a certain proportion of extreme scenarios to simulate the impact of meteorological disasters. The extreme scenarios considered in this study, along with their setup methods, are detailed in Table 1. By sampling the operational states of various generation resources across a large number of scenario years, the system’s power and energy supply–demand balance at each time step can be statistically analyzed, thereby obtaining the relevant evaluation metrics. The specific steps for applying sequential Monte Carlo sampling in adequacy evaluation can be found in [27].

Table 1.

Extreme scenario types evaluated and their configuration methods.

In Table 1, all extreme meteorological scenarios are constructed based on historical meteorological and power system data. For example, the “extreme heat with low wind” scenario uses recent three-year summer data to identify high-temperature periods, during which wind power output is set to the historical 5th percentile and load is increased by 10%. The “extreme cold with low solar” scenario is based on historical cold wave data, with PV output reduced to minimum levels and load increased by 10%. The “severe drought” scenario uses recent three-year dry-season hydrological data, reducing hydropower output to extremely low levels with a corresponding load increase. The probability of each scenario is determined by historical statistics (about 1–2%), and all parameter settings and durations are reviewed by experts for physical and engineering validity. These scenarios are randomly embedded in the Monte Carlo sampling to fully reflect the impact of extreme events on system adequacy. Single extreme meteorological events with the greatest system impact and highest frequency in actual grids were prioritized, ensuring both scientific rigor and practical feasibility. These three scenarios cover the main vulnerabilities of China’s power system in summer, winter, and dry seasons, reflecting both supply-side and demand-side extreme risks. Such scenario types have occurred frequently in practice and are also key focus areas in mainstream international adequacy assessments, meeting the needs of medium- and long-term system adequacy analysis.

All the generalized adequacy demand evaluation indicators presented above are calculated based on extreme values, with quantification performed using hourly simulation results for the entire year (8760 h). This approach was chosen to verify the adaptability of the proposed Generalized Adequacy coordinated planning framework and evaluation index system under extreme conditions. Therefore, using the maximum value provides a more intuitive representation of system performance under the most stringent constraints, thereby highlighting the effectiveness of the method in extreme scenarios.

2.2.2. Flexibility Adequacy Metrics

Currently, there is no universally accepted standard for evaluating system flexibility. Given the characteristics of the resource planning process and the intrinsic nature of flexibility regulation, flexibility adequacy metrics have been designed and selected based on the following principles:

- (1)

- The selected metrics should reflect the matching relationship between flexibility demand and supply.

- (2)

- In the planning process, the use of negative indicators, such as margin-based metrics, is more effective in highlighting existing system deficiencies and identifying gaps in flexibility regulation, thereby underscoring the necessity of resource planning.

- (3)

- Unlike power and energy adequacy, which primarily assess static capacity sufficiency, flexibility adequacy emphasizes the continuous matching of supply and demand at every moment. Therefore, it is essential to account for both the alignment between resource ramping rates and net load fluctuation rates across adjacent time intervals, as well as the consistency between ramping capacity and the overall range of net load variations.

In accordance with these principles, we propose two flexibility adequacy metrics: the flexible ramp capacity margin and flexible ramp rate margin. Flexible Ramp Capacity Margin refers to the total additional ramping capacity of flexible resources required to meet net load variations within a given time period. Flexible Ramp Rate Margin refers to the total additional ramping rate of flexible resources required to meet net load variation rates within a given time period. These metrics are systematically defined as the difference between flexibility demand and available supply within their respective dimensions, thereby quantifying the additional resources required to satisfy ramping rate and ramping capacity needs. The corresponding mathematical formulations for these metrics are provided as follows:

where represents the flexibility ramping rate margin in the studied region over a given time scale T; represents the flexibility ramping capacity margin in the studied region over time scale T; denotes the system’s flexibility ramping rate demand over time scale T, and denotes the system’s flexibility ramping capacity demand over time scale T. T represents the studied time scale. refers to the system’s normalized ramping rate over time scale T, while denotes the system’s normalized ramping capacity over time scale T.

The evaluation process first involves quantifying flexibility ramping rate demand and flexibility ramping capacity demand across different time scales. Then, the flexibility regulation capability of existing resources is assessed by computing the normalized ramping rate and normalized ramping capacity. A comparison of demand and supply capacity is conducted to obtain flexibility adequacy indicators. The quantification of demand primarily employs the first-order difference method, statistically analyzing net load variation rates and magnitudes based on historical net load curves over multiple years in the studied region. The maximum observed values are used as the flexibility demand. Supply capacity is quantified by statistically analyzing the attributes of available flexibility resources within the studied region, normalizing the results, and then computing the metrics. The specific calculation formulas are given as follows:

where represents the net load at time on day d in the -th historical load curve, while represents the net load variation rate at time on day d in the -th historical load curve over time scale . is a statistical function that derives the system’s flexibility ramping rate demand based on historical net load variation data. denotes the system’s flexibility ramping capacity demand over time scale . is a statistical function that derives the system’s flexibility ramping capacity demand based on historical net load fluctuation range data. represents the set of resources available for flexibility regulation over time scale . denotes the ramping rate of the -th type of resource available for flexibility regulation. represents the maximum output capacity of the -th type of flexibility resource. is the normalized capacity reference, set as the system’s annual peak load. represents the minimum output capacity of the -th type of flexibility resource.

2.2.3. Inertia Adequacy Metrics

Existing inertia indices in academic research primarily assess the system’s frequency security and stability from an operational perspective. However, to support the planning of inertia resources in renewable energy-integrated power systems, it is essential to develop an inertia adequacy index from a planning perspective. The critical aspect of planning inertia resources lies in quantifying the system’s minimum inertia requirement and establishing corresponding threshold standards. By synthesizing the global application of existing inertia evaluation indices, considering the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of inertia, and assessing the contribution of various inertia resources within the power system, this study proposes an inertia adequacy evaluation framework based on two key indicators: the minimum inertia requirement and the system inertia margin. The minimum inertia is defined as the minimum system inertia required to ensure that the rate of change of frequency (RoCoF) and frequency deviation do not exceed safety limits after a system disturbance, measured in MW·s. The inertia margin refers to the relative ratio between the system inertia and the minimum inertia requirement. A larger system inertia margin indicates that the system’s inertia level significantly exceeds the minimum inertia requirement. The calculation method is as follows:

where represents the minimum inertia of the power grid system. denotes the minimum inertia required for the receiving-end power grid to meet the maximum allowable rate of change of frequency. refers to the minimum inertia required to prevent the receiving-end power grid from triggering low-frequency load shedding. represents the total kinetic energy of synchronous generators. is the equivalent total kinetic energy of renewable energy virtual inertia. represents the total kinetic energy from other sources. The following presents the detailed derivation and calculation process.

- (1)

- RoCoF constraint (Initial rate of change of frequency)

The equivalent power deficit is denoted as , the system base frequency as , and the maximum allowable RoCoF as (Hz/s). The relationship is given by

- (2)

- Nadir constraint (Frequency nadir)

Assuming that primary frequency regulation ramps linearly within seconds to cover a fraction () of the power imbalance, and the maximum allowable frequency deviation is . Based on energy balance, the following approximation can be obtained:

The final minimum system inertia required is determined by adopting the more stringent constraint

where denotes the nominal system frequency, typically set to 50 Hz. represents the system base capacity. is the equivalent power deficit set for the system. refers to the maximum permissible rate of change of frequency. denotes the maximum allowable frequency deviation, used to constrain the frequency nadir. is the proportion of the imbalance that can be covered by primary frequency regulation (PFR) in the steady state. is the effective time required for PFR to reach the target output (or specified proportion) following its activation. represents the system equivalent inertia constant.

In terms of specific evaluation methods, inertia levels are assessed based on the generator dispatching strategies under different planning scenarios. Specifically, the minimum system inertia levels and required to ensure the most stringent frequency security indices (rate of change of frequency and lowest frequency point) are calculated [28]. Given that minimum inertia and inertia margin exhibit time-dependent characteristics, the effectiveness of a given planning scheme is evaluated based on the maximum value of the minimum inertia index and the minimum value of the inertia margin index over the evaluation period.

3. Comprehensive Power Grid Planning and Planning Scheme Selection Method Considering Generalized Adequacy

3.1. Comprehensive Power Grid Planning Framework Based on Generalized Adequacy

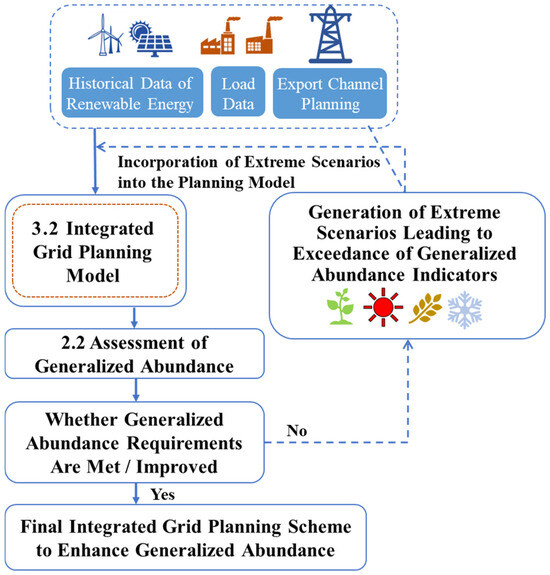

Under conventional resource and grid co-planning methodologies, a single optimal planning scheme is typically derived. However, the generalized adequacy indices proposed in Section 2 primarily serve as post-assessment tools, providing evaluation results only after a planning scheme has been formulated. This retrospective approach makes it challenging to identify directions for further optimizing resource allocation. Consequently, these indices are insufficient for guiding the coordinated planning of multi-type resources and the power grid to enhance the system’s generalized adequacy. To address this limitation, this study proposes a comprehensive power grid planning framework designed to improve generalized adequacy, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the integrated grid planning framework based on generalized adequacy.

Within this framework, the process begins by identifying representative planning scenarios through historical data curve clustering. Subsequently, the integrated power grid planning model introduced in Section 3.2 is employed to derive optimal planning schemes for multi-type resources and the power grid. For each generated planning scheme, generalized adequacy is evaluated using the methodology outlined in Section 2.2. If the generalized adequacy criteria are not met or if the level of generalized adequacy fails to improve, the framework identifies extreme scenarios where the adequacy indices exceed predefined limits. These critical scenarios are then incorporated into the scenario set utilized by the planning model. The integrated power grid planning process is iteratively executed until a planning scheme that satisfies the generalized adequacy requirements is obtained.

3.2. Integrated Power Grid Planning Model

3.2.1. Objective Function

Under the planning framework described in Section 3.2, to simulate the cross-temporal energy transfer function of energy storage at different timescales and account for the distributional differences in renewable energy and loads throughout the year, this study employs the temporal decomposition method proposed in [29]. This method decomposes the full 8760 h annual time horizon into intra-day and inter-day timescales to separately model power and energy balancing as well as resource operations. Additionally, to ensure inertia adequacy, constraints related to dynamic frequency security are incorporated into the traditional power grid planning model. Since the construction methods for certain scenario cost components and constraint conditions have been detailed in [29], they are not repeated here.

The objective of the planning model in this study is to minimize total costs, which include investment cost , operational cost , and carbon emission cost . Specifically, investment costs consist of line investment cost , renewable energy investment cost , long-duration energy storage investment cost , and short-duration energy storage investment cost . The calculation method is as follows:

where represents the total investment cost of a certain planned resource ; denotes the unit investment cost of resource ; is the investment scale of resource ; represents the set of nodes for planned resource deployment; is the investment discount rate calculated based on the annual interest rate; and represents the investment payback period. The indices , , , , and represent transmission lines, wind power units, photovoltaic power stations, short-term energy storage, and long-term energy storage, respectively.

Operating costs are categorized into long-term operating costs and short-term operating costs . The former includes long-term thermal power fuel costs and load-shedding costs , while the latter consists of short-term thermal power fuel costs , thermal power start-stop costs , and load-shedding costs . The calculation methods for specific cost components are as follows:

where is the weighting factor representing the proportion of daily electricity balance operating costs to total operating costs. It reflects the consideration of daily operating costs in the comprehensive planning. This paper assumes equal weighting between long-term and short-term costs, setting .

The carbon emission cost is calculated as follows:

where represents the total number of typical days; denotes the number of calendar days represented by typical day ; is the carbon emission penalty coefficient; represents the carbon emissions of thermal power unit at time on typical day .

3.2.2. Constraints

- (1)

- Planning Constraints

Planning constraints primarily govern the allocation and investment scale of various resources, encompassing transmission line construction constraints, renewable energy capacity constraints, and short-term and long-term energy storage capacity constraints. The mathematical formulation of these constraints is presented as follows:

where is a binary decision variable indicating whether the -th new transmission line is constructed on branch ( if the line is constructed, otherwise not); represents the set of candidate transmission lines; is the maximum number of additional lines between transmission nodes and ; and also represents the maximum operational scale of a certain planned resource .

- (2)

- Short-Term Operation Constraints

Short-term constraints are designed to ensure the balance of electricity power and energy within a daily timescale while imposing operational limitations on various resources. These constraints include nodal power balance constraints, power flow constraints, thermal power generation and start-stop constraints, renewable energy generation constraints, and short-term/long-term energy storage operation constraints. In this section, we focus on the formulation of nodal power balance constraints, power flow constraints, and dynamic frequency security constraints, which play a critical role in maintaining system stability and operational feasibility.

where and are the nodal-branch incidence matrices for the initial system lines and candidate lines, respectively; and represent the active power flow vectors of the initial system lines and candidate lines at time on typical day , respectively; and , , , , , , , , , , respectively denote the active power vectors of thermal power generation, wind power generation, photovoltaic generation, hydropower generation, short-term energy storage charging, short-term energy storage discharging, long-term energy storage charging, long-term energy storage discharging, external transmission corridor flow, nodal load, and nodal load shedding. , and represent the susceptance of a single transmission line on branch , the number of initial system lines, and the maximum number of additional candidate lines, respectively; is the set of initial system lines; represents the total active power flowing through the initial system branch at time on typical day ; represents the active power flowing through the newly built -th transmission line on branch at time on typical day ; , , represent the voltage phase angles of nodes , , and the reference balancing node at time on typical day ; and and are the inertia time constants of thermal power units and short-term energy storage, respectively. , represent the maximum output limit of thermal power unit and the planned capacity of short-term energy storage unit , respectively; is the upper bound of the frequency regulation power capacity for thermal power units, typically set at 8%; , denote the total frequency regulation capacity provided by thermal power units and energy storage at time ; represents the power disturbance due to frequency deviations at time , typically set as 10% of the system load; and denote the response times required for thermal power units and energy storage to reach a specified frequency regulation power level; represents the maximum allowable RoCoF; is the nominal system frequency; and represents the maximum permissible frequency deviation. The linearization method of Equation (35) can be found in reference [30].

3.3. Planning Scheme Selection Method Considering Generalized Adequacy

Under the planning framework proposed in Section 3.1, the integrated power grid planning model designed to enhance generalized adequacy generates a cost-minimized planning scheme in each iteration, with each scheme exhibiting a different level of generalized adequacy. A key challenge lies in evaluating the differences among various planning schemes and selecting the optimal scheme under diverse policy orientations. To address this challenge, this section first introduces a scheme evaluation index system, which incorporates the generalized adequacy indicators presented in Section 2.2. Subsequently, a combined subjective–objective weighting method is applied to determine the comprehensive weights of the indices. Finally, the PROMETHEE-II method is employed to compare and rank different planning schemes, ultimately identifying the most suitable scheme that meets the planning requirements.

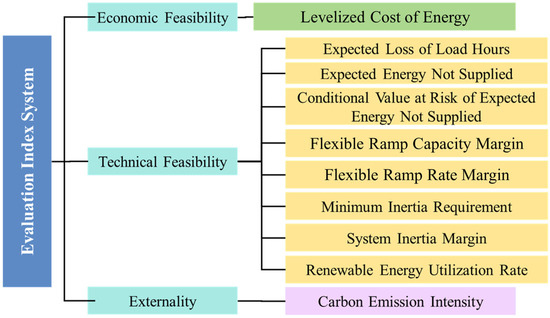

3.3.1. Scheme Evaluation Index System

During the post-evaluation stage of a planning scheme, it is essential to assess its performance from multiple dimensions, including economic viability, technical feasibility, and environmental impact. Based on these considerations, this study proposes a scheme evaluation index system encompassing three primary dimensions—economic, technical, and external factors—comprising a total of ten evaluation indicators, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The evaluation index system of generalized adequacy.

Within this evaluation framework, the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) is defined as the average cost required to generate 1 kWh of electricity within the system. The corresponding mathematical formulation is as follows:

where represents the LCOE, measured in $/kWh; denotes the total amount of electrical energy generated by all power sources within the system over the entire simulation period embedded in the planning model, measured in kWh.

The renewable energy utilization rate is defined as the percentage of renewable energy consumption relative to the total electricity generation over the entire simulation period embedded in the planning model. Its calculation method is as follows:

where represents the renewable energy utilization rate; denotes the actual consumed electricity from renewable energy sources; refers to the total electricity generation from renewable energy sources.

Carbon emission intensity is defined as the amount of carbon dioxide emissions in t/MWh of electricity generated on average over the entire simulation period embedded in the planning model. Its calculation method is as follows:

where represents the carbon emission intensity indicator, measured in t/MWh.

It is worth noting that the seven generalized adequacy indicators proposed in Section 2.2 form the technical core of the evaluation system and correspond one-to-one with seven of the ten evaluation indicators in the scheme assessment framework. Specifically, LOLH, EENS, and the indicator correspond to the evaluation of power and energy adequacy; the flexibility ramping rate margin and ramping capacity margin indicators correspond to the assessment of flexibility adequacy; and the minimum inertia requirement together with inertia margin indicators correspond to inertia adequacy. On this basis, three supplementary indicators, including LCOE, renewable energy utilization rate, and carbon emission intensity, are further incorporated to capture economic efficiency, renewable energy accommodation capability, and environmental performance. Consequently, the ten-indicator system can be regarded as an integrated framework consisting of “seven generalized adequacy indicators and three external comprehensive indicators,” in which the former reflects supply–demand balance, flexibility, and frequency security, while the latter extends the evaluation toward economic and environmental dimensions, thus ensuring a holistic and multi-criteria assessment of planning schemes.

The proposed indicators and the relevant variables involved in their calculation have been summarized as follow Table 2.

Table 2.

Indicator symbols and definitions.

3.3.2. Scheme Comparison Method

After obtaining the evaluation results of each planning scheme based on the evaluation index system proposed in Section 3.3.1, it is essential to establish a rational balance among the relative importance of different indicators and perform a corresponding comparative analysis. In this study, a combined weighting method integrating both subjective and objective approaches is employed during the index weighting stage. The subjective weights are determined using the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), while the objective weights are derived through the entropy weight method. Subsequently, a game theory-based combined weighting approach is utilized to obtain the final comprehensive weights.

Once the evaluation results and indicator weights for each planning scheme have been determined, this study adopts PROMETHEE-II as the method for scheme comparison. The fundamental procedure is outlined as follows:

- (1)

- Calculating the deviation function between schemes.

The deviation function quantifies the relative degree to which one scheme outperforms another under a specific indicator. This function is constructed based on the evaluation results of the planning schemes for the same indicator. By establishing predefined judgment criteria, the evaluation process generates a result within the range of 0 to 1. The specific construction methodology is as follows:

where represents the deviation function, indicating the relative difference between planning schemes and under evaluation indicator ; denotes the difference in evaluation values between planning schemes and under evaluation indicator ; and represent the evaluation results of planning schemes and under evaluation indicator , respectively.

Common judgment criteria include standard criteria, quasi-criteria, criteria with linear preference relationships, stepwise criteria, criteria with linear preference relationships and indifference thresholds, and Gaussian criteria. The selection of an appropriate criterion depends on specific policy requirements and planning objectives. In this study, ten key indicators—LCOE, LOLH, EENS, Conditional Value at Risk of EENS, Flexible Ramp Capacity Margin, Flexible Ramp Rate Margin, Minimum Inertia Requirement, System Inertia Margin, Renewable Energy Utilization Rate and Carbon Emission Intensity—are evaluated using criteria in which lower values indicate superior performance. The applicable judgment criterion for these indicators is as follows:

For inertia margin and renewable energy utilization rate indicators, higher values indicate better performance. The applicable judgment criterion for these indicators is

- (2)

- Constructing the Preference Index

The preference index represents the degree of priority of different schemes under the same evaluation indicator. For schemes and , incorporating the weights of each attribute, the preference index is defined as follows:

where represents the preference index; denotes the comprehensive weight of evaluation indicator , as calculated in Section 3.3.1.

- (3)

- Calculating the Net Flow of Each Scheme

Each scheme is defined with its inflow and outflow. Outflow represents the positive flow, indicating that the given scheme ranks higher relative to another scheme. The greater the outflow, the higher the ranking of the scheme. Conversely, inflow represents the negative flow, indicating a lower ranking.

where , and represent the outflow, inflow, and net flow of scheme , respectively.

- (4)

- Scheme Ranking

The schemes are ranked based on their net flow values, where a larger net flow indicates a higher ranking. If the net flow values are equal, the schemes are considered to be at the same ranking level. The best scheme can be identified through net flow ranking.

In this study, a stepwise 0/1 rule is adopted for the discrimination function in PROMETHEE-II. This choice is primarily due to its high consistency with the threshold-based logic used in adequacy indicator assessment (such as LOLH, EENS, and inertia constraints), which directly reflects whether a scheme meets or fails key constraints. This setting enhances the simplicity and transparency of the evaluation process and highlights the significant advantages or disadvantages of different schemes with respect to core indicators. Given the limited number of alternatives and the relatively substantial differences in key indicators, the 0/1 criterion is sufficient to emphasize substantial improvements and avoids the amplification of minor differences that may result from continuous preference functions, thereby ensuring the reproducibility and cross-scenario comparability of results. It should be noted, however, that when the number of candidate schemes is large or the differences between them are more subtle, linear, quasi-criterion, or Gaussian standard preference functions may better capture gradual differences.

4. Case Study

4.1. Case Study Setup

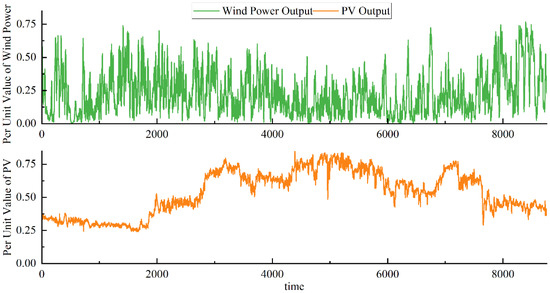

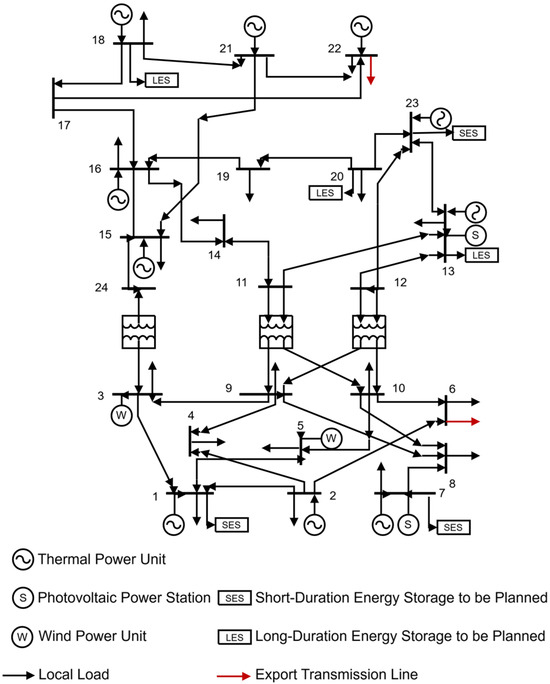

Building upon the traditional IEEE 24-node system, additional resources, including wind power, photovoltaic (PV) power, energy storage, and transmission corridors, are incorporated to validate the proposed method. The renewable energy output curves utilized in this study are depicted in Figure 3, while the transmission line power dispatch plan is derived from real-world measurement data from a province in China. The carbon price assumptions, load and renewable energy output profiles, network constraints, RoCoF and Nadir parameters, frequency response limits, response times, and other relevant parameters are consistent with those in [31]. The total installed capacity of thermal power remains unchanged in the modified system. In the modified configuration, a 250 MW wind farm is incorporated at nodes 3 and 5, and a 250 MW photovoltaic power station is integrated at nodes 7 and 13, with each node permitting a maximum planning capacity of 750 MW for wind or PV power. Planned short-term energy storage is allocated at nodes 1, 7, and 23, whereas planned long-term energy storage is designated for nodes 13, 18, and 20. The duration of short-term energy storage is no more than 4 h, while long-term energy storage is defined as having a duration greater than 4 h [32]. The cost parameters for short-term and long-term energy storage, as well as renewable energy planning, are set in accordance with the reference in [33,34]. The system’s maximum load is 3500 MW, while transmission line capacities are set at 500 MW and 800 MW, respectively. The modified 24-node topology is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Renewable energy output curve used in the study.

Figure 4.

Improved 24-bus topology.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, four comparative scenarios are established: Scenario M1 involves planning only renewable energy, short-term energy storage, and transmission lines, representing the traditional power grid coordinated planning method; Scenario M2 includes coordinated planning of renewable energy, both short-term and long-term energy storage, and transmission lines, but does not consider dynamic frequency security requirements; Scenario M3 builds upon Scenario M2 by incorporating the dynamic frequency security constraints described in Section 3.2.2; Scenario M4 applies the proposed generalized adequacy-based grid planning method. The key difference between Scenario M3 and Scenario M4 is that M3 considers planning solutions based solely on typical scenarios, whereas M4 relies on a broader framework.

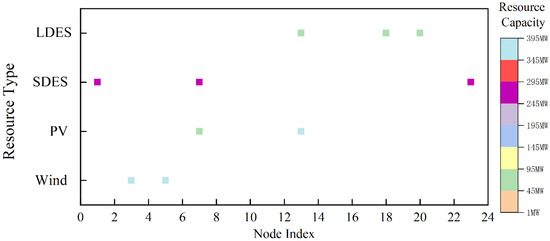

The differences between the four scenarios are summarized in Table 3, while the resource planning results for the four scenarios are presented in Table 4. The symbols “√” in Table 3 are used to indicate whether the corresponding resource or constraint is included in each scenario. The node-based planning distribution of wind power, photovoltaic power, short-term energy storage, and long-term energy storage in Scenario M4 is illustrated in Figure 5.

Table 3.

Configuration of planning scenarios.

Table 4.

Resource planning results under four scenarios.

Figure 5.

Multi-type resource planning results under the M4.

Examining the planning results presented in Table 4, the transition from Scenario M1 to M2 reveals a reduction in the scale of renewable energy deployment due to the integration of long-term energy storage. In Scenarios M3 and M4, the incorporation of dynamic frequency security constraints imposes additional requirements on the primary frequency regulation capability and inertia support capacity of energy storage and thermal power. As a result, the scale of short-term energy storage increases significantly. Furthermore, to ensure adequate primary frequency regulation response capability, thermal power units in Scenarios M3 and M4 no longer operate at full load, necessitating a moderate increase in renewable energy capacity to compensate for the overall electricity demand. The transition from Scenario M3 to M4 further incorporates generalized adequacy considerations related to extreme scenarios, such as low-probability meteorological events, leading to an overall expansion in the scale of renewable energy and short-term energy storage.

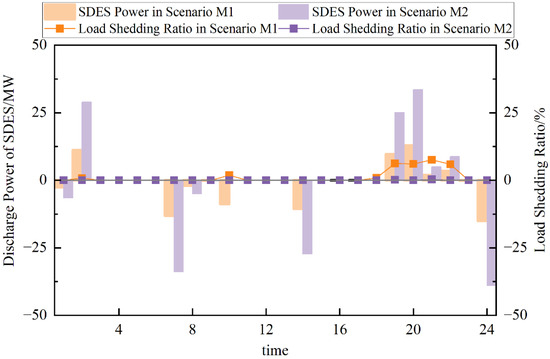

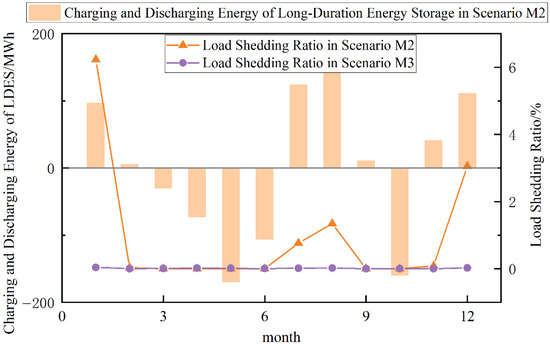

4.2. Analysis of the Synergistic Effects of Multi-Type Resources

To analyze the synergistic interactions among different resources and verify the effectiveness of the proposed dynamic frequency security constraints, system operation under Scenarios M1 to M3 is examined. Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate the charging and discharging behavior of short-term and long-term energy storage in Scenarios M1 and M2 across typical daily and intra-day periods, using the load shedding ratio as an indicator of electricity supply reliability. Observations indicate that in Scenario M1, due to the absence of intra-day energy shifting capability and the limited scale of energy storage, approximately 7.5% load shedding occurs when photovoltaic (PV) output declines sharply after 18:00. This issue persists, albeit to varying degrees, in July and August. In contrast, Scenario M2, which integrates long-term energy storage, effectively mitigates peak-period load shedding. The presence of long-term energy storage enables energy shifting across both intra-day and daily timescales, thereby significantly enhancing the system’s power and energy adequacy.

Figure 6.

Short-term energy storage daily charge/discharge profile and load shedding ratio.

Figure 7.

Long-term energy storage monthly charge/discharge profile and load shedding ratio.

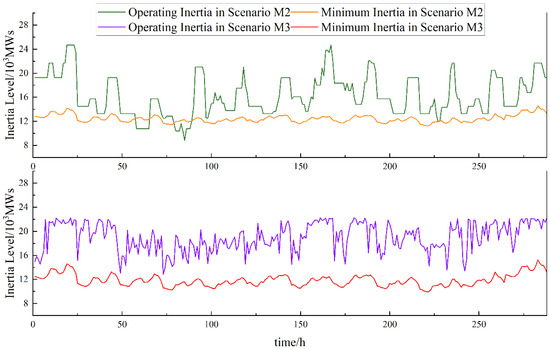

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed dynamic frequency security constraints, inertia adequacy levels in Scenarios M2 and M3 are analyzed, as shown in Figure 8. The results indicate that when frequency security constraints are not considered, a certain number of thermal power units remain operational to maintain dynamic frequency stability. However, as renewable energy generation fulfills most of the local and export load demand, the number of active thermal power units is relatively low. Consequently, the actual system inertia level falls below the threshold required for secure system operation. Under specific conditions, when frequency security verification is conducted using a 10% load disturbance, frequency deviations exceeding safe limits may occur. By incorporating dynamic frequency security constraints, the proposed pre-constraint approach accounts for the coordinated response of energy storage and thermal power during frequency events, thereby effectively ensuring inertia adequacy within the system.

Figure 8.

Relationship between operational inertia and minimum inertia under M2 and M3.

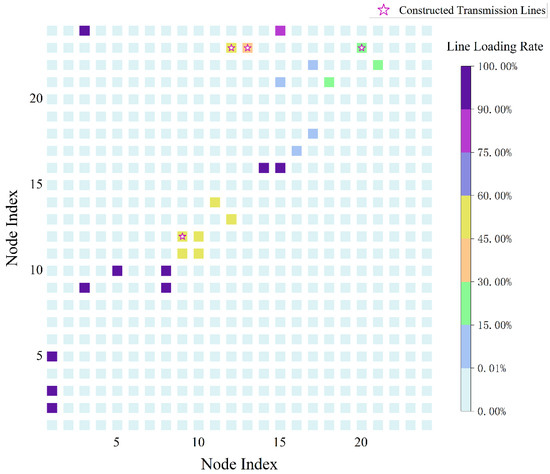

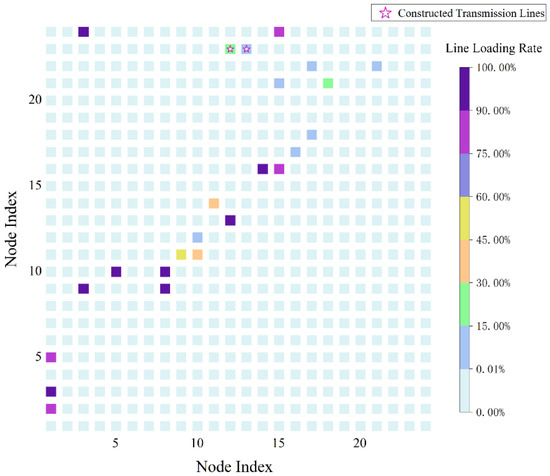

To evaluate the impact of the proposed method on transmission line loading, Figure 9 and Figure 10 illustrate the branch loading levels in Scenarios M1 and M4. The statistical metric employed is the mean load ratio of the top 50% highest-loading time periods across all planning scenarios. In Figure 9 and Figure 10, the horizontal and vertical axes represent node indices, with each small square indicating the load ratio of the corresponding transmission branch. A light blue square signifies no transmission line connection between the two nodes, while other colors denote loading levels of the connected transmission lines, with different colors representing varying load ratios. A comparative analysis of Figure 9 and Figure 10 reveals that during peak hours, the loading ratio in branches such as node pairs 1–2 and 1–5 approaches 100%, indicating severe transmission congestion. However, following the implementation of the proposed method, the load ratios on branches 1–2, 1–5, 10–12, 11–14, 12–23, and 13–23 exhibit a notable reduction. This outcome demonstrates that through coordinated planning of renewable energy, short-term and long-term energy storage, and transmission infrastructure, transmission congestion can be effectively alleviated, thereby delaying the necessity for new transmission line construction.

Figure 9.

Load factor of each branch under M1.

Figure 10.

Load factor of each branch under M4.

4.3. Quantitative Assessment of System Generalized Adequacy Improvement

To further validate the effectiveness of the proposed method in enhancing the generalized adequacy of the system, the generalized adequacy evaluation indices introduced in Section 2.2 are applied to assess the four scenarios. The evaluation results are summarized in Table 5. When the flexible ramp rate margin in the table is negative, it indicates that the available ramping capability is sufficient or surplus and can meet the maximum net load variation rate at all times; when it is positive, it means that in certain periods the ramping capability is insufficient, indicating an operational risk.

Table 5.

Partial results of multi-type resource planning.

Table 6 presents the indicator values for each scheme calculated using the 95% as the standard. The 95% represents the value below which 95% of the hourly demand falls during the annual simulation, thereby excluding the influence of a small number of extreme peaks on the indicators.

Table 6.

Planning results with the 95% demand percentile definition.

Examining Table 5, it is evident that in terms of power and energy adequacy, the evaluation index values in Scenarios M1 to M4 exhibit a progressive decline, signifying a gradual improvement in power and energy adequacy. When only typical scenarios derived from clustering are considered, the LOLH indicator in Scenario M3 still slightly exceeds the 3 h/a standard commonly adopted in Europe [7]. However, in Scenario M4, after incorporating generalized adequacy considerations, certain low-probability scenarios listed in Table 1 are integrated into the planning model. As a result, the proposed planning solution attains a degree of resilience against extreme weather events, such as cold waves, leading to a substantial reduction in power and energy adequacy evaluation indices under Scenario M4. Additionally, the results in Table 5 indicate that although low-probability extreme weather events do not significantly impact the overall EENS, they can lead to substantially more severe energy shortages than conventional outages. In Scenario M4, the worst-case energy shortage reaches up to six times the EENS value, underscoring the necessity of considering low-probability extreme weather events as renewable energy penetration increases. By strategically configuring stable generation resources, the risk of energy supply shortfalls during such adverse events can be effectively mitigated.

In terms of flexible ramping adequacy, Scenarios M2 to M4 maintain non-positive flexible ramping margins, indicating that flexible ramping requirements are fully met. However, due to the increased scale of renewable energy deployment in Scenario M4, its flexible ramping adequacy exhibits a slight increase, though it remains within an acceptable range. In contrast, Scenario M1, lacking long-term energy storage capacity, experiences minor deficiencies in flexible ramping rate, which may potentially lead to load-shedding events under certain conditions.

With regard to inertia adequacy, Scenarios M1 and M2 struggle to ensure adequate inertia support and primary frequency regulation capability at all times due to the absence of dynamic frequency security constraints. In contrast, in Scenarios M3 and M4, the incorporation of these constraints ensures that operating inertia remains consistently above the minimum required threshold. Additionally, minimum inertia levels are influenced by factors such as the number of online generating units and the dispatchability of storage resources, leading to variations in minimum inertia levels across different scenarios.

As shown in Table 6, when the 95% is used as the demand criterion, the numerical values of the shortage-related indicators decrease compared to those based on the maximum value; however, the ranking of the different schemes remains consistent. This indicates that the superiority of a scheme does not solely depend on extreme peak periods, but rather reflects structural differences across the majority of operating hours. Therefore, the relative ranking of schemes remains stable despite changes in the calculation standard. The use of the 95% as the calculation standard effectively reduces the risk of over-allocation caused by extreme cases, while maintaining the consistency of the scheme evaluation results. This demonstrates the robustness of our proposed indicators across different demand quantification approaches.

4.4. Planning Scheme Comparison

To determine the optimal planning scheme, the four scenarios analyzed in this section are evaluated using the scheme comparison methodology proposed in Section 3.3. The combined subjective–objective weighting approach is applied to derive the relative importance of each evaluation index, and the corresponding evaluation results for the four scenarios are summarized in Table 7. Additionally, the net flow values and ranking of each scenario, calculated using the PROMETHEE-II method, are presented in Table 8.

Table 7.

Evaluation results and indicator weights of planning schemes under four scenarios.

Table 8.

PROMETHEE-II Ranking Results.

As shown in Table 7, the evaluation indices assigned the highest weights include LCOE, carbon emission intensity, LOLH, and EENS. This suggests that researchers prioritizing index evaluation tend to focus on economic performance, power and energy adequacy, and decarbonization effects. Furthermore, the significant weight assigned to these indices may indicate that their variability across different scenarios is relatively large. The comparison results presented in Table 8 reveal that among the four planning scenarios, the proposed method demonstrates the best overall performance. Specifically, it effectively enhances the generalized adequacy of the power system while maintaining acceptable economic feasibility and decarbonization performance, thereby confirming its effectiveness and practical applicability.

5. Conclusions

With the rapid increase in renewable energy penetration, the concept of adequacy in power systems has evolved beyond traditional power and energy balance considerations to encompass flexible ramping adequacy and inertia adequacy. This paradigm shift introduces new challenges for power system planning methodologies, ex-post evaluation indices, and planning scheme comparison approaches. To address these challenges, this study builds upon conventional adequacy theories and introduces the generalized adequacy theory along with its evaluation indices. A comprehensive grid planning framework is developed to enhance system-wide generalized adequacy, complemented by a planning scheme comparison method that explicitly incorporates generalized adequacy considerations. Through case studies, this research validates the effectiveness of the proposed generalized adequacy-based integrated power grid planning approach, examines the synergistic effects among various resources, and quantifies the impact of the proposed method on system-wide adequacy enhancement. Compared to conventional power grid planning approaches, the introduction of generalized adequacy theory enables a more holistic evaluation of planning schemes, considering power and energy adequacy, flexible ramping capability, and inertia support capacity. This facilitates more informed decision-making in resource allocation and system expansion planning.

However, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations of this study. Specifically, only two types of energy storage operating at different timescales are considered, while demand-side response resources—such as electric vehicles and smart buildings—as well as the synergistic interactions among wind, solar, hydro, thermal, and storage resources, remain outside the current scope. As power system architectures continue to evolve, future research may focus on the following three aspects:

- (1)

- Systematically comparing various families of standard preference functions (e.g., linear, Gaussian, etc.) and conducting parameter sensitivity analyses to comprehensively examine the robustness of scheme rankings under different functional forms and threshold settings, thereby improving the generalizability and scalability of the methodology.

- (2)

- Further investigating the evolutionary trends of adequacy requirements and designing quantitative assessment methods for system adequacy under compound extreme events, with the aim of enhancing the resilience and security of power systems in the face of such events.

- (3)

- Investigating the diversified applications of demand response and thoroughly analyzing its synergistic mechanisms with renewable energy and energy storage, in order to support the enhancement of multi-dimensional adequacy in power systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en18185024/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Y., L.F., Y.L. and Z.W.; Data curation, J.Y., L.X. and Z.M.; Formal analysis, J.Y., L.F., Y.L. and Z.M.; Investigation, L.F.; Methodology, J.Y., L.F., Z.M. and Z.C.; Resources, Z.W.; Software, J.Y. and Z.M.; Supervision, L.X. and Z.C.; Validation, Z.M.; Visualization, J.Y.; Writing—original draft preparation, J.Y., Y.L. and Z.C.; writing—review and editing, L.F. and Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article is sponsored by State Grid Jiangxi Electric Power Co., Ltd. (5218A024000G).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Jian Yin, Lixiang Fu, Liming Xiao and Yuejun Luo were employed by the State Grid NanChang Electric Power Supply Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, L.; Wang, C.; Wu, Z. Reinforcement Learning-Based Time of Use Pricing Design Toward Distributed Energy Integration in Low Carbon Power System. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Skov, I.R. Full energy system transition towards 100% renewable energy in Germany in 2050. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 102, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, M.; Yu, T.; Wang, Y. The coupling effect of carbon emission trading and tradable green certificates under electricity marketization in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 187, 113750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borasio, M.; Moret, S. Deep decarbonisation of regional energy systems: A novel modelling approach and its application to the Italian energy transition. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 153, 111730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Singh, A.K.; Zhao, J.; Meliopoulos, A.S.; Pal, B.; bin Mohd Ariff, M.A.; Van Cutsem, T.; Glavic, M.; Huang, Z.; Kamwa, I.; et al. Dynamic state estimation for power system control and protection. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 5909–5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, H.; Li, F.; Zhu, J.; Tingen Ii, W.J.; Mukherjee, S. Modeling the impact of extreme summer drought on conventional and renewable generation capacity: Methods and a case study on the Eastern U.S. power system. Appl. Energy 2024, 363, 122977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenclik, D. New Resource Adequacy Criteria for the Energy Transition: Modernizing Reliability Requirements; Energy Systems Integration Group: Reston, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariatkhah, M.-H.; Haghifam, M.-R.; Chicco, G.; Parsa-Moghaddam, M. Adequacy modeling and evaluation of multi-carrier energy systems to supply energy services from different infrastructures. Energy 2016, 109, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chung, C.Y.; Mall, R.S. Power System Operational Adequacy Evaluation With Wind Power Ramp Limits. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 2706–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Li, H.; Qiao, Y. Probabilistic Flexibility Evaluation for Power System Planning Considering Its Association With Renewable Power Curtailment. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 3285–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannoye, E.; Flynn, D.; Malley, M.O. Transmission, Variable Generation, and Power System Flexibility. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2015, 30, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wen, Y.; Yang, W. Inertia Security Region: Concept, Characteristics, and Assessment Method. Proc. CSEE 2021, 41, 3065–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, P.; Zheng, Y.; Jin, Y.; Qin, C.; Jiang, Y.; Cao, L. Analytic assessment of the power system frequency security. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2021, 15, 2215–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Shao, C.; Shahidehpour, M.; Wang, X. Coordinated planning strategies of power systems and energy transportation networks for resilience enhancement. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 14, 1217–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, K.; Zadeh, S.G.; Hagh, M.T. Planning for a network system with renewable resources and battery energy storage, focused on enhancing resilience. J. Energy Storage 2024, 87, 111339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerik, G.; Karatepe, E. Stochastic chance constrained transmission expansion decisions for different investment budgets. In Proceedings of the 2018 6th International Istanbul Smart Grids and Cities Congress and Fair (ICSG), Istanbul, Turkey, 25–26 April 2018; pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Xu, X.; Ma, H.; Yan, Z. Distributionally Robust Co-optimization of Transmission Network Expansion Planning and Penetration Level of Renewable Generation. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2022, 10, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chen, H.; Liang, Z.; Zhu, Y. A Flexibility-oriented robust transmission expansion planning approach under high renewable energy resource penetration. Appl. Energy 2023, 351, 121786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mercado, J.I.; Gutiérrez-Alcaraz, G.; Gonzalez-Cabrera, N. Improved binary particle swarm optimization for the deterministic security-constrained transmission network expansion planning problem. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 150, 109110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fan, G.; Zhang, J. Suitability evaluation system for the shallow geothermal energy implementation in region by Entropy Weight Method and TOPSIS method. Renew. Energy 2022, 184, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, A.; Junhan, Q.; Huanyu, H.; Zhidong, W.; Dong, P.; Lang, Z. Comprehensive Evaluation of Power Grid Security and Benefit Based on BWM Entropy Weight TOPSIS Method. Mod. Electr. Power 2021, 38, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Zhang, X.-T.; Li, Q.-H.; Ran, L.; Cai, Z.-X. Gray theory based energy saving potential evaluation and planning for distribution networks. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2014, 57, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbáth, T.; Van Hertem, D. Appropriate transmission grid representation for European resource adequacy assessments. Appl. Energy 2024, 355, 122378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grijalva, S.; Visnesky, A.M. The effect of generation on network security: Spatial representation, metrics, and policy. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2006, 21, 1388–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazmi, A.A.; Zahedi, G. Sustainable energy systems: Role of optimization modeling techniques in power generation and supply—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 3480–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebaraj, S.; Iniyan, S. A review of energy models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2006, 10, 281–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero. Exploring Reliability Standard Metrics in a Net Zero Transition. The U.K. Government: 2023. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65e3a3323f694514a3035fbe/5-exploring-reliability-standard-metrics-in-net-zero-transition.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Amarasinghe, P.A.G.M.; Abeygunawardane, S.K.; Singh, C. Kernel Density Estimation Based Time-Dependent Approach for Analyzing the Impact of Increasing Renewables on Generation System Adequacy. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 138661–138672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guihong, Z.; Fei, L.; Shibin, W.; Jitai, L. Inertia Requirement Analysis of Frequency Stability of Renewable-dominant Power System. Proc. CSU-EPSA 2022, 34, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Du, E.; Zhang, N.; Zhuo, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Renewable Electric Energy System Planning Considering Seasonal Electricity Imbalance Risk. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 5432–5444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, C.; Zhou, M.; Sun, G.; Wu, Z. An Integrated Grid Planning Approach Considering System Adequacy: A Case Study of Shanxi Province. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 8th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Shenyang, China, 29 November–2 December, 2024; pp. 1772–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twitchell, J.; DeSomber, K.; Bhatnagar, D. Defining long duration energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 60, 105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Ghasemi, H. Security-Constrained Unit Commitment with Linearized System Frequency Limit Constraints. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2014, 29, 1536–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wei, L.; Yang, L.; Yuan, B.; Zhou, M. Understanding the synergy of energy storage and renewables in decarbonization via random forest-based explainable AI. Appl. Energy 2025, 390, 125891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).