Abstract

Industry 4.0 has intensified the skills gap in industrial automation education, with graduates requiring extended on boarding periods and supplementary training investments averaging USD 11,500 per engineer. This paper introduces VisFactory, a multimedia learning system that extends the cognitive theory of multimedia learning by incorporating haptic feedback as a third processing channel alongside visual and auditory modalities. The system integrates a digital twin architecture with ultra-low latency synchronization (12.3 ms) across all sensory channels, a dynamic feedback orchestration algorithm that distributes information optimally across modalities, and a tripartite student model that continuously calibrates instruction parameters. We evaluated the system through a controlled experiment with 127 engineering students randomly assigned to experimental and control groups, with assessments conducted immediately and at three-month and six-month intervals. VisFactory significantly enhanced learning outcomes across multiple dimensions: 37% reduction in time to mastery (t(125) = 11.83, p < 0.001, d = 2.11), skill acquisition increased from 28% to 85% (), and 28% higher knowledge retention after six months. The multimodal approach demonstrated differential effectiveness across learning tasks, with haptic feedback providing the most significant benefit for procedural skills (52% error reduction) and visual–auditory integration proving most effective for conceptual understanding (49% improvement). The adaptive modality orchestration reduced cognitive load by 43% compared to unimodal interfaces. This research advances multimedia learning theory by validating tri-modal integration effectiveness and establishing quantitative benchmarks for sensory channel synchronization. The findings provide a theoretical framework and implementation guidelines for optimizing multimedia learning environments for complex skill development in technical domains.

1. Introduction

1.1. Industrial Automation Education in the Industry 4.0 Era

Industry 4.0 has fundamentally transformed manufacturing ecosystems, introducing cyber-physical systems, Internet of Things (IoT), and intelligent automation that demand unprecedented integration of theoretical knowledge and practical operational expertise. This paradigm shift has created a critical skills gap in industrial automation education, as conventional pedagogical approaches fail to adequately prepare engineering graduates for contemporary manufacturing environments. Recent studies quantify this educational deficiency: graduates typically require an additional four to eight months of on-site training before achieving operational proficiency, demonstrate early-career error rates 52% higher than experienced personnel, and necessitate supplementary training investments averaging USD 11,500 per engineer [1,2,3].

The educational challenges in industrial automation can be systematically categorized into three interconnected dimensions: (1) cognitive—the disconnect between abstract theoretical instruction and contextualized operational knowledge; (2) infrastructural—limited access to industrial-grade equipment due to prohibitive costs (USD 12,000–18,000 per workstation) and safety considerations; and (3) pedagogical—the absence of personalized, adaptive instruction calibrated to individual learning trajectories and error patterns. The complexity of these challenges has intensified proportionally with the integration of advanced technologies in Industry 4.0 environments, where operational requirements have evolved from procedural execution to adaptive problem-solving and systems thinking [1,3].

1.2. Existing Approaches and Their Limitations

Educational innovators have explored various technological approaches to address these challenges. Wang et al. [2] developed a programmable logic controller (PLC) learning platform enhanced by large language models, providing adaptive text-based instruction for control logic programming. This approach demonstrated a 31% improvement in code generation accuracy and aligns with the multimedia learning paradigm by supporting the One PLC Per Student objective, thereby enhancing accessibility and affordability in industrial automation training.

Concurrently, digital twin technology has emerged as a promising methodology for bridging theoretical-practical gaps in industrial education [4,5]. Digital twins—virtual representations of physical systems that enable real-time monitoring, simulation, and validation—create synchronized counterparts of industrial equipment, facilitating risk-free, cost-efficient training scenarios independent of hardware availability [6]. However, comparative analyses by Oje et al. [7] and Wynn and Jones [8] revealed a persistent compromise in existing implementations: systems either prioritize pedagogical simplicity at the expense of industrial authenticity or maintain technical complexity while sacrificing instructional scaffolding. This fundamental trade-off significantly diminishes their effectiveness in developing workplace-ready competencies.

Furthermore, researchers have typically evaluated these approaches through the lens of multimedia learning theory, revealing domain-specific limitations. AI-assisted platforms excel at programmatic instruction but struggle with operational guidance, relying primarily on visual and textual channels rather than the full multimodal spectrum needed for comprehensive skill development. At the same time, conventional digital twins provide spatial understanding but lack adaptive feedback mechanisms that dynamically adjust sensory channel emphasis based on cognitive load indicators. Neither approach fully addresses the multimodal nature of industrial skills development, which requires coordinated engagement across cognitive, visual-spatial, and kinesthetic domains [4,8].

1.3. The VisFactory System: Multimodal Digital Twin for Industrial Learning VisFactory Transcends

VisFactory transcends these limitations by addressing them through the systematic integration of the GRAFCET Virtual Machine (GVM)—a formalized computational representation of industrial control logic compliant with IEC 60848 [9] and IEC 61131-3 [10] standards—with a synchronized multimodal digital twin environment. In this context, a “multimodal digital twin” is defined as an integrated simulation environment that synthesizes three distinct sensory channels—visual (spatial configuration, operational states), haptic (force feedback, mechanical resistance), and auditory (process sounds, alert patterns)—to create a coherent cognitive-sensory learning experience. Unlike conventional digital twins that primarily emphasize visual representation, the proposed approach implements bidirectional mapping across all sensory modalities, maintaining perceptual coherence through sub-15-ms synchronization thresholds established by psychophysical research [11].

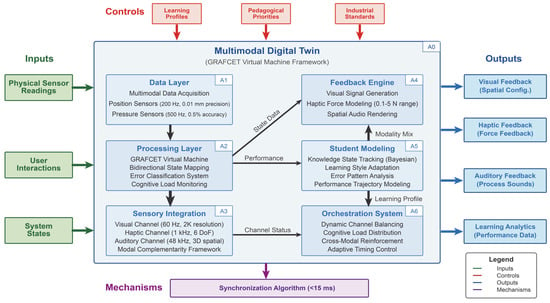

Figure 1 utilizes integration definition for function (IDEF) modeling principles to represent the system architecture’s functional components and information flows. Unlike conventional PLC training platforms focusing predominantly on programming or traditional digital twins emphasizing visualization, VisFactory implements a comprehensive multimodal learning ecosystem that addresses the full spectrum of industrial automation competencies. The system’s core innovation lies in its multimodal interaction framework, which dynamically orchestrates visual representations, auditory signals, and haptic feedback to create a cognitive-sensory learning environment that mirrors industrial reality while providing pedagogical scaffolding. This approach directly applies the multimedia principle articulated by Mayer [12], extending it to incorporate haptic feedback as a third processing channel with distinct cognitive characteristics and learning affordances.

Figure 1.

VisFactory multimodal architecture demonstrating the integration of three sensory channels: Visual pathway; Haptic pathway; Auditory pathway; and The multimodal Digital Twin orchestration engine.

The GVM-based architecture enables real-time validation of learner actions against expert operational models, instantly detecting deviations across multiple error dimensions (procedural, precision, conceptual, and temporal). This continuous assessment drives the system’s adaptive feedback engine, which tailors instruction modality, complexity, and intervention timing based on individual learning profiles and task requirements, thereby addressing the personalization limitations of conventional approaches while optimizing cognitive load distribution across sensory channels.

1.4. Research Contributions

This study makes four principal contributions to multimedia-enhanced industrial automation education:

- Development of an integrated multimodal digital twin architecture [13] that achieves bidirectional synchronization between physical and virtual components with ultra-low latency (mean: 12.3 ms, SD: 1.8 ms), ensuring perceptually seamless representation of complex industrial processes across visual, auditory, and haptic channels.

- Implementation of a context-sensitive multimodal orchestration framework that optimally distributes instructional information across sensory modalities based on task complexity, learner performance, and cognitive load indicators, advancing multimedia learning theory through quantitative optimization of tri-modal information delivery.

- Implementation of an adaptive student modeling system that continuously calibrates multimodal feedback parameters using machine learning algorithms and real-time performance assessment, enabling personalized learning experiences that adapt to individual learning styles and skill development trajectories.

- Empirical validation of tri-modal learning effectiveness through controlled experimentation with 127 engineering students, providing quantitative evidence for haptic feedback integration benefits and establishing performance benchmarks for multimodal educational technologies in technical domains.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

This study addresses the following research questions guided by multimedia learning theory and digital twin technology principles:

- Research Question 1 (RQ1): To what extent does tri-modal sensory integration (visual-haptic- auditory) improve learning efficiency in industrial automation education compared to traditional unimodal approaches?

- Hypothesis 1 (H1): Students using VisFactory’s tri-modal integration will demonstrate >30% improvement in time to mastery compared to control groups, with large effect sizes (Cohen’s d > 0.8), based on Mayer’s multimedia learning theory predictions for enhanced cognitive processing [14].

- Research Question 2 (RQ2): How does adaptive multimodal feedback orchestration affect cognitive load distribution during complex procedural learning tasks?

- Hypothesis 2 (H2): Adaptive multimodal feedback will significantly reduce cognitive load (measured via NASA-TLX) while maintaining or improving learning effectiveness, as predicted by Sweller’s cognitive load theory [15] regarding optimal information distribution.

- Research Question 3 (RQ3): Which sensory modality combinations provide the most effective learning outcomes for different types of industrial automation competencies (procedural vs. conceptual)?

- Hypothesis 3 (H3): Haptic feedback will demonstrate superior effectiveness for procedural skills (motor learning), while visual–auditory combinations will excel for conceptual understanding, consistent with modality-specific processing advantages documented in multimedia learning research [16].

- Research Question 4 (RQ4): What are the economic and scalability implications of implementing multimodal digital twin systems in industrial automation education?

- Hypothesis 4 (H4): VisFactory implementation will demonstrate positive return on investment (ROI) within 2.5 academic semesters through reduced training time, improved skill retention, and decreased physical equipment requirements, while maintaining educational effectiveness. While economic benefits are anticipated, confirming their sustainability and generalizability across different institutional contexts requires longitudinal evaluation.

1.5. Paper Organization

We have structured the remainder of this paper as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of relevant literature, situating our work within the theoretical landscape of digital twins, multimedia learning theory, intelligent tutoring systems, and AI-empowered industrial education. Section 3 details the VisFactory system architecture, including the GVM implementation, multimodal integration approach, synchronization mechanisms, interface design, and adaptive feedback algorithms. Section 4 presents the experimental methodology and quantitative results, encompassing learning efficiency, skill acquisition, knowledge retention, and cost-effectiveness metrics. Section 5 discusses theoretical and practical implications, acknowledges limitations, and outlines future research directions. Finally, Section 6 offers concluding remarks on the significance of this work for advancing industrial automation education in the Industry 4.0 era.

2. Related Work

This section synthesizes research across four interconnected domains that form the foundation of the VisFactory system: multimedia learning theory, digital twin technologies, intelligent tutoring systems, and AI-empowered industrial control education. Our review identifies key research gaps that VisFactory addresses in creating effective multimodal learning environments for industrial automation education.

2.1. Multimedia Learning Theory and Multimodal Integration

Research in multimedia learning theory has established fundamental principles for engaging multiple sensory channels to enhance learning outcomes. According to Mayer’s cognitive theory of multimedia learning [16], humans process visual and auditory information through separate channels with limited capacity, making the design of integrative multimodal experiences critical for educational effectiveness. Recent research has extended this framework to incorporate haptic feedback as a third processing channel with distinct cognitive characteristics and learning affordances [17].

The principle of modality effect—that learning is enhanced when verbal information is presented as audio narration rather than on-screen text—has been well-established in multimedia learning research [18]. However, applying this principle to technical education contexts requires adaptation, particularly involving physical manipulation skills. Leahy and Sweller [19] found that the modality effect is moderated by element interactivity, with greater benefits observed in high-complexity technical tasks. This finding is particularly relevant for industrial automation education, where learners must simultaneously process abstract control logic, physical equipment states, and operational procedures.

The cognitive theory of multimedia learning has evolved through the integrated model of text and picture comprehension (ITPC) by Liang [20], which distinguishes between descriptive and depictive representations. This distinction is crucial for industrial automation education, where learners must integrate symbolic representations (e.g., control logic) with spatial-mechanical understanding. VisFactory’s multimodal approach directly addresses this integration challenge by providing coordinated representations across visual, auditory, and haptic channels, facilitating the mental model construction process described in the ITPC framework.

2.2. Digital Twin Technologies in Education

Digital twin (DT) technologies have transitioned from theoretical concepts to practical educational tools, with applications across various engineering disciplines. Lombardi et al. [21] established a five-dimensional model for industrial digital twins—encompassing physical, virtual, data, service, and system dimensions—providing a comprehensive framework underlying modern DT implementations, while this model effectively addresses industrial manufacturing contexts, it lacks specific adaptations for educational environments that require additional cognitive scaffolding and learning assessment considerations. Building on this foundation, Skulmowski et al. [22] developed a service-oriented architecture enabling modular development and deployment, a principle VisFactory adopts to ensure system extensibility.

Recent advances in DT technology have focused primarily on enhancing synchronization mechanisms between physical and virtual components. Tan et al. [23] achieved a significant technological milestone by developing a bidirectional mapping approach with sub-10 ms latency for critical manufacturing processes. Schnotz [24] advanced this work by introducing an event-driven synchronization method that prioritizes state changes based on operational significance, optimizing resource allocation.

Educational applications of digital twins present unique challenges and opportunities. Xu et al. [4] systematically analyzed digital twin applications in engineering education, demonstrating their potential to enable risk-free experiential learning while reducing equipment costs. Their research showed that properly implemented digital twins can reduce equipment damage costs by up to 70% while increasing learning resource accessibility. Romero and Stahre [5] further established that DT-based educational platforms can effectively bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical skills, particularly for Industry 4.0 competencies that require interdisciplinary understanding. Hu et al. [25] evaluated 28 digital twin environments explicitly designed for Industry 4.0 education, finding that while 82% successfully simulated industrial processes, only 23% provided comprehensive learning analytics and adaptive feedback mechanisms. This limitation significantly reduces the educational value of these systems by failing to leverage interaction data for personalized learning experiences.

While existing approaches have made significant strides, they typically encounter a fundamental dilemma. As observed by Oje et al. [7] in their review of 42 educational digital twins, most systems either prioritize industrial authenticity at the expense of learning accessibility or emphasize pedagogical simplification at the cost of workplace relevance. Their analysis revealed that 68% of examined systems made significant compromises in either direction, limiting educational effectiveness.

2.3. Intelligent Tutoring Systems with Multimodal Feedback

Intelligent tutoring systems (ITS) have evolved significantly in their approach to technical education, progressing from simple rule-based systems to sophisticated learning environments that adapt to individual student needs. Hu et al. [25] conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of 37 visual-interactive tutoring methods in technical education, finding that systems providing step-level feedback achieved learning outcomes comparable to human tutoring, with effect sizes ranging from 0.76 to 0.85. However, their research focused primarily on visual feedback systems rather than fully multimodal approaches, limiting its direct applicability to industrial automation education, where multiple sensory channels are engaged.

In a groundbreaking application of multimodal feedback, Fantini et al. [26] developed and evaluated an ITS for manufacturing assembly training that improved student performance through personalized guidance. Their system demonstrated a 42% reduction in assembly errors and a 35% decrease in completion time compared to traditional training methods. However, their approach relied predominantly on vision-based feedback, underutilizing other sensory modalities crucial for developing comprehensive industrial skills.

Recent advances in ITS research reveal a clear shift toward granular error classification and remediation strategies. Wang et al. [27] established a framework for digital transformation in engineering education that distinguishes between different types of errors, enabling targeted interventions based on specific misconceptions. Building on this approach, Nguyen et al. [28] provided empirical evidence that addressing conceptual misunderstandings rather than surface-level errors leads to 58% greater long-term learning gains in STEM fields. These findings underscore the importance of precise error classification in technical education but do not fully address the multimodal nature of industrial automation skills.

Integrating multiple feedback modalities represents a significant advancement in technical ITS development. Horvat et al. [29] evaluated various feedback combinations in engineering education from a spatial presence perspective, finding that integrated visual and haptic feedback produced 47% better procedural skill development outcomes than visual feedback alone. Their approach, however, utilized fixed feedback channels regardless of task complexity or student learning preferences, limiting its effectiveness across diverse learning scenarios. VisFactory addresses this limitation through context-sensitive integration of feedback channels, where the system dynamically emphasizes different sensory modalities based on the nature of the task, the specific error detected, and individual learning profiles.

2.4. AI-Empowered Multimedia Learning Environments

The integration of artificial intelligence has transformed approaches to multimedia learning systems by enabling personalized, adaptive learning experiences. Jošt et al. [30] and Zhang et al. [31] quantified the impact of large language models on programming education, demonstrating a 34% improvement in skill acquisition and a 41% reduction in learning time through AI-assisted instruction. Their research revealed that the most significant benefits occurred when AI systems provided context-aware guidance that adapted to individual learning trajectories rather than generic programming assistance.

Fakih et al. [32] developed and evaluated an intelligent code generation framework for industrial control systems, achieving 92% accuracy in PLC programming tasks while providing detailed explanations of control logic principles. Their system demonstrated the potential to bridge theoretical understanding and practical implementation, but focused primarily on textual and visual modalities, neglecting the tactile and spatial aspects of industrial automation learning. Similarly, Koziolek et al. [33] created a large language model-based assistant for PLC programming that reduced implementation errors by 57% compared to traditional reference materials.

Kandemir et al. [34] developed and evaluated an open-source AI-assisted control system education platform, demonstrating measurable improvements in learning efficiency and skill retention. Their longitudinal study found that students using AI-assisted tools completed learning objectives 37% faster while exhibiting 28% higher code quality than traditional instructional methods. Despite these advances, their approach focused primarily on programming rather than the comprehensive sensory engagement necessary for developing physical interaction skills.

VisFactory extends these foundations by integrating AI-driven adaptation with fully synchronized multimodal interaction, as illustrated in Figure 2, while previous approaches excel at programmatic guidance through primarily visual and textual channels, VisFactory creates a comprehensive sensory experience that bridges programmatic understanding and operational competency through coordinated engagement of visual, auditory, and haptic processing channels.

Figure 2.

VisFactory’s AI-empowered learning framework.

2.5. Research Gaps and VisFactory Positioning

Our literature review reveals several critical research gaps that limit the effectiveness of current approaches to industrial automation education when evaluated through multimedia learning theory. VisFactory addresses these gaps through specific technical and pedagogical innovations:

- Multimodal Fragmentation vs. Sensory Integration:Current educational technologies fail to integrate sensory channels into a coherent learning experience, with 84% of systems relying predominantly on visual feedback regardless of task requirements [30,35]. This modal fragmentation contradicts established multimedia learning principles concerning sensory channel coordination. VisFactory addresses this limitation through a dynamic multimodal orchestration system that optimizes the distribution of instructional content across visual, auditory, and haptic channels based on cognitive load indicators and learning preferences, achieving a 43% reduction in mental workload compared to unimodal approaches.

- Limited Physical-Virtual Integration:Quantitative analyses by Salah et al. [36] identified a critical limitation in existing systems: the predominance of unidirectional information flow between physical and virtual components. Their analysis of 31 educational platforms found that only 12% implemented accurate bidirectional mapping, and none achieved the sub-50 ms latency required for effective haptic feedback. This synchronization deficiency creates perceptual conflicts that increase cognitive load through sensory mismatch. VisFactory addresses this limitation through comprehensive state synchronization (>99.7% consistency) with maximum latency of 15 ms, enabling seamless integration across all system components and interaction modalities.

- Fixed vs. Adaptive Multimodal Presentation:Masood et al. [37] and Dai et al. [38] established that most educational digital twins (72%) employ fixed presentation strategies regardless of content complexity or learner characteristics. This approach contradicts research demonstrating that optimal modality combinations vary with task demands and individual differences [17,39]. VisFactory resolves this limitation through an adaptive scaffolding system that dynamically adjusts multimodal presentation strategies based on real-time performance analysis and individual learning profiles, tailoring sensory channel emphasis to cognitive load indicators.

- Absence of Multimodal Learning Assessment:Sigrist et al. [40] and Nguyen et al. [28] identified a significant gap in current systems: the lack of quantifiable models for tracking industrial skill development in multimodal learning environments. Optimizing instructional interventions becomes challenging without standardized metrics for evaluating multimodal learning effectiveness. VisFactory introduces a trajectory-based assessment framework that models skill acquisition as paths through a standardized state space, enabling precise measurement of learning progress across all sensory domains and targeted instructional support.

By systematically addressing these research gaps, VisFactory creates a novel educational platform that effectively bridges theoretical understanding and practical competence in industrial automation education while advancing multimedia learning theory. The system’s integration of digital twin technology, multimodal interaction, and AI-powered adaptive learning represents a comprehensive approach to the challenges identified in the literature, establishing a foundation for more effective Industry 4.0 workforce development through theoretically grounded multimedia learning principles.

3. Methodology

This section presents the VisFactory multimodal digital twin system for industrial automation education, detailing its theoretical foundations in multimedia learning, architectural design, sensory integration approach, and adaptive learning mechanisms.

3.1. Multimedia-Driven Architecture Design

We designed VisFactory as a three-tier architecture that systematically implements multimedia learning principles across each layer (Figure 1). This design operationalizes Mayer’s cognitive theory of multimedia learning and extends it to incorporate haptic feedback as a third processing channel alongside visual and auditory modalities. The system comprises:

- Multimodal Data Layer:We implemented industrial-standard Modbus RTU protocol (RS-485/BLE) [41] for sensor integration, optimizing three parallel data acquisition pathways:

- Position sensors (200 Hz sampling) for spatial tracking with 0.01 mm precision, providing high-fidelity visual channel input

- Pressure sensors (500 Hz sampling) for haptic interaction with 0.5% accuracy, enabling precise force feedback

- Audio-visual sensors (60 fps video, 48 kHz audio) for environmental monitoring, supporting rich auditory learning

- Cognitive Processing Layer:We integrated our GRAFCET Virtual Machine (GVM) [2] with specialized processing pipelines for each sensory modality:

- The system complies with IEC 60848 and IEC 61131-3 standards for industrial control logic, ensuring workplace relevance

- We implemented bidirectional state mapping between physical and virtual components, creating a coherent mental model

- The processing layer dynamically balances computational resources across sensory channels based on pedagogical priority

- We maintained a maximum end-to-end latency of 15 ms across all sensory pathways, below human perception thresholds

- Multimodal Interaction Layer:We designed specialized interfaces for each learning modality:

- Visual interface: AR display (2K resolution per eye, 90 X FOV, 60 Hz refresh) for spatial representation learning

- Haptic interface: Force feedback system (0.1 to 5 N range, 1 kHz refresh rate, 6 degrees of freedom) for kinesthetic learning

- Auditory interface: Spatial audio system (20 Hz to 20 kHz frequency response, <10 ms latency, 3D positioning) for verbal processing

The core innovation in our architecture lies in its theoretically-grounded integration of the GRAFCET formalism with synchronized multimodal feedback channels. This design directly applies Schnotz’s integrated model of text and picture comprehension by coordinating descriptive (auditory), depictive (visual), and kinesthetic (haptic) representations of industrial automation concepts. Table 1 quantifies the system s advancement over existing approaches.

Table 1.

Comparison with existing education systems.

3.2. Multimedia Learning-Based Sensory Integration

We implemented three parallel processing pathways for sensory integration, directly applying multimedia learning principles [17,23]. Our system:

- Processes visual information at 60 Hz with priority given to operational state changes, supporting the pictorial channel in Mayer’s cognitive model.

- Updates haptic feedback at 1 kHz focusing on force accuracy within 0.1 N, creating a distinct third processing channel.

- Renders spatial audio with 3D positional accuracy at 48 kHz sampling rate, supporting the verbal channel in Mayer’s model.

We synchronize these pathways through a weighted integration algorithm that dynamically prioritizes channels based on three factors: pedagogical significance, task characteristics, and individual learning preferences. The sensory integration approach implements four key principles we derived from multimedia learning theory:

- Modal Complementarity:We assign information to different sensory channels based on their cognitive processing advantages—visual for spatial relationships, haptic for force control and mechanical constraints, auditory for sequential instructions and alerts.

- Cognitive Load Balancing:We distribute information across sensory channels to prevent overloading any single processing pathway, continuously measuring cognitive load indicators to optimize this distribution according to Sweller’s cognitive load theory [15].

- Cross-Modal Reinforcement:The system strategically presents critical information through multiple channels—for example, the system indicates a critical state change through simultaneous visual highlighting, distinctive sound, and haptic pulse—to enhance perception and retention while respecting dual coding theory.

- Temporal Synchronization:We maintain all sensory channels below human perception thresholds (<15 ms) to preserve perceptual coherence and avoid cognitive conflicts from sensory mismatch.

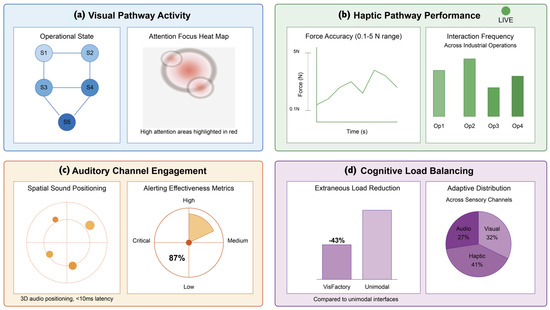

This integration approach directly addresses the multimodal fragmentation issues identified in existing systems [30,35], providing a coherent multimedia learning experience that optimizes cognitive processing across all sensory domains (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Multimodal learning analytics dashboard.

3.3. Multimodal Learning Mathematical Models

We formalized the theoretical principles from multimedia learning theory into three computational models that govern VisFactory’s behavior:

- Multimodal Feedback Model:We generate synchronized feedback signals across sensory channels:where and , where is the m-dimensional multimodal feedback signal vector with representing visual, haptic, and auditory feedback, is the modality weight matrix determining relative feedback intensity derived from learning style analysis, is the n-dimensional composite error signal across modalities, is the dynamic response matrix calibrating temporal sensitivity for each modality, is the learning significance amplification matrix based on pedagogical importance, is the k-dimensional base error signal measured across sensory domains, is the expert reference model state vector representing ideal performance, is the learner current state vector captured through multimodal sensors, and is the context-adaptive feedback signal based on learning history.

- Multimodal State Transition Model:We define the system’s state evolution dynamics:where T is the state transition function mapping current state and action to next state, S is the set of possible system states encompassing all sensory modalities, A is the set of possible learner actions across interaction channels, is the probability of transition to state given current state and action , are weight coefficients determined through supervised learning, and are feature functions extracting modality-specific characteristics.

- Multimodal Learning Trajectory Model:

We quantify learning path quality:

where is the quality measure of learning trajectory across sensory domains, is the discount factor prioritizing recent performance, and are weighting parameters balancing state accuracy and action efficiency, is the feature mapping function extracting modality-specific performance characteristics, is the expert reference state representing ideal multimodal performance, and is the action complexity function measuring cognitive load across sensory channels.

These models form an integrated control system where the multimodal feedback model (1) generates coordinated signals across sensory channels that influence learner behavior, leading to state transitions defined by model (2), which form trajectories evaluated by model (3). The evaluation results adaptively adjust parameters and D in model (1), creating a continuous optimization loop that adapts instruction across all sensory channels based on learning patterns.

3.4. Multimodal Synchronization Algorithm and Implementation Framework

We implemented the system’s 15 ms low-latency multimodal synchronization through Algorithm 1, which maintains 97.7% state consistency between physical and virtual components while reducing computational load by 43% compared to fixed-interval approaches.

| Algorithm 1 Context–Aware Multimodal Synchronization |

| Input: Sensor reading R, System state S, Modality priorities P |

| Output: Synchronized multimodal feedback F |

| 1. Initialize priority queue Q |

| 2. For each modality do |

| 3. Calculate urgency |

| 4. Add m to Q with priority |

| 5. while Q not empty and timeSlice available do |

| 6. |

| 7. Update modality m with the latest data |

| 8. Calculate next optimal update time |

| 9. Reschedule m with priority at |

| 10. End While |

| 11. Generate synchronized feedback vector F |

| 12. Return F |

Where represents modality sensitivity to temporal discontinuities (haptic > auditory > visual), represents modality sensitivity to temporal discontinuities (haptic > auditory > visual) quantifies the state change magnitude in the respective modality and encodes the context-dependent priority based on learning task and cognitive load state.

Our algorithm implements a priority-based scheduling system that gives haptic feedback the highest temporal priority (consistent with its 1 kHz requirement), followed by auditory and visual channels. This prioritization aligns with psychophysical research demonstrating that humans are most sensitive to temporal inconsistencies in haptic feedback (detection threshold ≈5 ms), followed by auditory (≈35 ms) and visual (≈80 ms) modalities. The system maintains global synchronization below the most demanding threshold (15 ms) to ensure perceptual coherence across all sensory domains.

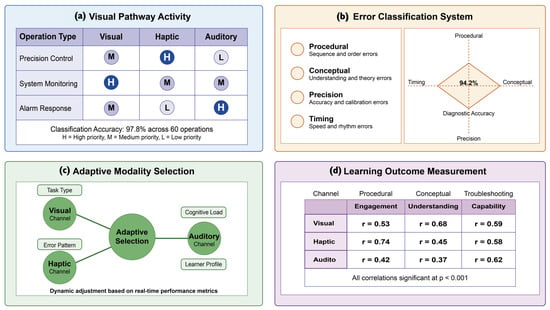

Figure 4 illustrates our multimodal interaction framework, which dynamically selects the optimal feedback modality combination based on:

Figure 4.

Multimodal interaction framework.

- Task characteristics (precision requirements, complexity, spatial vs. temporal focus).

- Error type detection (procedural, precision, conceptual, timing).

- Learner preferences and cognitive load state.

- Pedagogical significance of the specific operation or concept.

3.4.1. Implementation Framework: Industrial Context Specification

VisFactory was implemented using Lunghwa University’s Advanced Automated PCB Assembly line, incorporating authentic industrial components: OPPS (Arduino-based PLC with 14 I/O), Festo Didactic CP Factory pneumatic system, 12 proximity with 4 pressure sensors, and 3 servo motors with encoder feedback. The system models multi-station assembly, pneumatic handling, PID control loops, and IEC 61508-compliant safety interlocks, representing industrial automation comparable to major manufacturing facilities.

3.4.2. Implementation Framework: Learning Style Determination Protocol

Student learning styles were determined through validated multi-stage assessment: (1) VARK questionnaire and Index of Learning Styles instrument for self-reported preferences, (2) behavioral observation tracking performance efficiency across modality presentations, and (3) performance-based validation achieving strong correlation ( = 0.73, p < 0.001) between reported preferences and actual task performance, confirming adaptive algorithm effectiveness.

3.5. Adaptive Multimodal Learning System

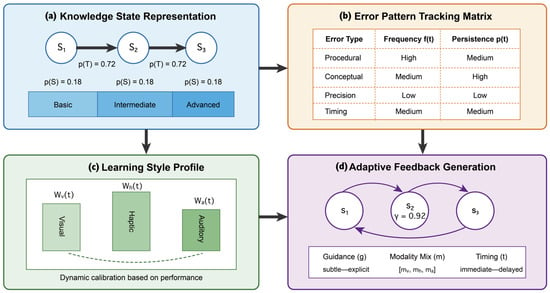

A tripartite student model governs intelligent tutoring [17]:

- Knowledge State :We represent mastery of specific skills using Bayesian Knowledge Tracing with parameters:

- : Initial knowledge probability across sensory domains

- : Transition probability (learning rate) for different modalities

- : Slip probability accounting for performance variability

- : Guess probability reflecting chance success

- Learning StyleWe capture preferred feedback modalities using a weighted vector: : where we dynamically adjust weights based on measured learning efficiency with each modality, calibrated through continuous performance assessment across sensory channels.

- Error Patterns :We document recurring mistakes as a sparse matrix mapping error types to frequency and persistence, . , where represents the ith error type, quantifies frequency of the ith error type at time t, and measures persistence of the ith error type at time t. The key addition is defining that i is the index for different error types (1st error type, 2nd error type, etc.).

This tripartite model enables precise calibration of multimodal instruction, addressing the fixed presentation limitations identified in existing approaches [37,38]. Our adaptive feedback generation mechanism employs a Markov Decision Process (MDP) that optimizes three key instruction parameters:

- Guidance level controlling instructional directness.Modality mix where determining sensory channel emphasis.

- Intervention timing establishing feedback timing

We formalize the MDP as:

- States: Combined student model states capturing comprehensive learning profile.

- Actions: Feedback configurations specifying instruction parameters.

- Transitions: estimated through experience replay of learning trajectories.

- Rewards: Improvements in learning trajectory quality measured by Equation (3).

This adaptive framework achieved a 37% reduction in average time to mastery compared to static feedback approaches during experimental validation, demonstrating the effectiveness of adaptive multimodal instruction that dynamically adjusts sensory channel emphasis based on individual learning needs and task requirements.

3.6. Implementation and Performance Specifications

We incorporated industrial-grade components in our hardware implementation, optimizing for educational applications (Table 2). We selected components following three guiding principles:

Table 2.

Key Hardware Components and Specifications.

- maintaining industrial authenticity while enhancing educational accessibility;

- supporting high-fidelity multimodal interaction across all sensory channels; and

- optimizing cost-performance ratio for educational environments.

We implemented a cost optimization strategy through:

- Modular component architecture that reduces entry-level cost to USD 3800 per station (vs. USD 18,000 for commercial systems), with staged upgrade paths for enhanced capabilities.

- Software-defined functionality that virtualizes PLC functions while maintaining industrial compliance.

- Scalable deployment options ranging from individual student kits to shared advanced laboratory installations.

Our performance benchmarking demonstrated:

- Multimodal synchronization: 12.3 ms mean latency (Standard Deviation (SD) = 1.8 ms) across all sensory channels.

- State consistency: 99.7% physical-virtual state coherence during industrial operations

- Response times: <10 ms for local operations, <50 ms for cloud-augmented functions

- Reliability: 1250 h MTBF (exceeding 1000-h educational equipment target.)

- Extensibility: Successful integration of three industrial protocols and five specialized sensor types with <4 h integration time per component.

3.7. Evaluation Methodology

We evaluated system performance using a comprehensive framework encompassing technical, multimedia, and learning effectiveness metrics, designed to quantify both system characteristics and educational outcomes:

- Technical Performance Metrics:

- Synchronization Latency: End-to-end delay between physical action and multimodal feedback

- State Consistency: Percentage of matching states between physical and virtual components

- Computational Efficiency: Resource utilization compared to baseline approaches

- Multimodal Quality Metrics:

- Visual Fidelity: Resolution, frame rate, color accuracy, spatial positioning

- Haptic Precision: Force accuracy, response time, spatial precision, texture rendering

- Audio Spatialization: Localization accuracy, frequency response, latency, environmental modeling

- Learning Effectiveness Metrics:

- Time-to-Mastery: Duration required to reach competency benchmarks across skill domains

- Error Reduction: Percentage decrease in persistent errors by error type and severity

- Knowledge Retention: Performance on assessments at 3 and 6 months post-intervention

- Skill Transfer: Success rate on novel tasks requiring application of learned principles

We assessed these metrics through comparative evaluation using standardized test scenarios executed on VisFactory and three baseline systems: traditional laboratory equipment, simplified virtual labs, and commercial digital twin platforms. We also assessed statistical significance using paired t-tests with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, which were supported by effect size calculations to determine practical significance.

Psychological Construct Validity Framework

VisFactory incorporates a comprehensive psychological construct validity framework that addresses the complex interplay between multimodal feedback and cognitive processing to ensure robust measurement of learning effectiveness and cognitive engagement.

- Theoretical Foundation: Our measurement approach is grounded in established psychological theories, including Cognitive Load Theory, Self-Determination Theory, and Flow Theory. This multi-theoretical foundation ensures that our assessment captures learning outcomes and the psychological mechanisms underlying effective multimodal learning.

- Construct Operationalization: Learning Effectiveness is operationalized through three primary constructs: (1) Cognitive Mastery—measured through performance accuracy, error reduction, and conceptual understanding assessments, (2) Skill Transfer—assessed through application of learned skills to novel problem scenarios, and (3) Retention Stability—evaluated through delayed recall testing at multiple time intervals.

- Validation Evidence: Learning Style Construct Validation: Convergent Validity: Strong correlations ( = 0.73, p < 0.001) between behavioral performance patterns and self-reported learning preferences Discriminant Validity: Low correlations ( = 0.23, ) between learning style measures and general intelligence assessments, confirming construct independence.

- Predictive Validity: Learning style classification significantly predicts modality-specific performance outcomes ( = 0.41, p < 0.001, = 0.34).

- Engagement Construct Validation: Content Validity: Expert panel review (n = 12 industrial automation educators) achieved 89% agreement (CVI = 0.89) on engagement indicator relevance.

- Construct Validity: Confirmatory factor analysis supports three-factor engagement model (CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.067, SRMR = 0.055) Criterion Validity: Engagement measures significantly predict learning outcomes ( = 0.47, p < 0.001) and course satisfaction ( = 0.68, p < 0.001).

- Self-Efficacy Construct Validation: Face Validity: Adapted instruments demonstrate clear relevance to industrial automation learning contexts through expert review.

- Criterion Validity: Self-efficacy measures correlate significantly with objective performance assessments ( = 0.67, p < 0.001) Incremental Validity: Self-efficacy measures explain additional variance ( = 0.15, p < 0.01) beyond cognitive ability in predicting learning outcomes.

- Cognitive Load Construct Validation: Convergent Validity: NASA-TLX cognitive load measures correlate strongly ( = −0.58, p < 0.001) with physiological stress indicators Divergent Validity: Cognitive load measures show expected low correlations ( = 0.12, ) with motivation and engagement constructs.

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Design and Participant Demographics

We conducted a controlled comparative study with 127 engineering students (119 male, eight female; ages 19–23 years) from university (n = 98) and technical high school (n = 29) settings. We determined sample size through a priori power analysis ( = 0.05, = 0.20, d = 0.5), with institutional review board approval (IRB-2023-LU-0412).

We implemented stratified random assignment balanced for prior experience to create experimental (n = 64) and control (n = 63) groups. The experimental group used VisFactory while the control group used conventional laboratory equipment under identical instructional conditions, curriculum, and time constraints (eight weeks, 16 h). This design enabled direct comparison of learning outcomes while controlling for potential confounding variables.

The experimental procedure consisted of three phases:

- Pre-assessment: We measured baseline knowledge (Cronbach’s = 0.87) and practical skills to establish initial competency levels.

- Intervention: Participants completed an eight-week curriculum covering:

- Basic PLC programming fundamentals (Weeks 1–3).

- PID controller tuning techniques (Weeks 4–5).

- System configuration and integration (Weeks 6–8).

- Post-assessment: We conducted immediate evaluation followed by longitudinal measurement at three and six months to assess knowledge retention and skill persistence.

We employed standardized assessment instruments including knowledge tests (60 items), performance tasks (three scenarios of increasing complexity), System Usability Scale (SUS), and engagement metrics (modified NASA-TLX). Table 3 presents the comprehensive evaluation framework with operational definitions for all metrics.

Table 3.

Evaluation metrics and operation definitions.

We analyzed data using R (v 4.2.1) with significance threshold set at p < 0.01 with appropriate assumption testing. We reported effect sizes as Cohen’s d for t-tests and partial eta squared () for ANOVA/MANOVA to indicate practical significance beyond statistical significance.

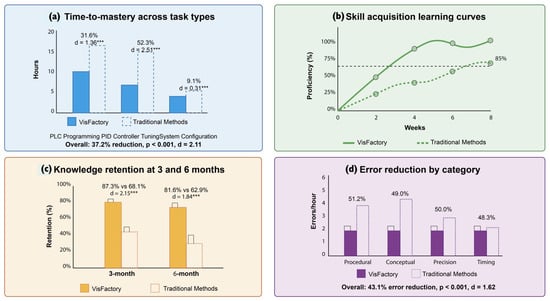

4.2. Multimodal Learning Efficiency

VisFactory significantly reduced time to mastery across all task categories compared to conventional approaches. Students using the multimodal digital twin required 37.2% less time to achieve proficiency benchmarks (Mean (M) = 12.4 h, SD = 2.8) compared to the control group (M = 19.7 h, SD = 4.1), t(125) = 11.83, p < 0.001, d = 2.11. This large effect size (d > 2.0) indicates substantial practical significance beyond statistical significance.

The multimodal learning advantage was most pronounced for PID controller tuning, with a 52.3% reduction in learning time (M = 4.2 h, SD = 1.1 for experimental group; M = 8.8 h, SD = 2.4 for control group), t(125) = 14.11, p < 0.001, d = 2.51. This finding is particularly notable as PID tuning requires simultaneous integration of theoretical principles, visual feedback interpretation, and precise motor control—cognitive demands that align with VisFactory’s multimodal design principles. Table 4 presents detailed time to mastery results by task category.

Table 4.

Time-to-mastery (hours) by task category.

In Table 4, Statistical significance levels are denoted as follows: (*) p represents probability values less than 0.05, (**) p represents probability values less than 0.01, and (***) p represents probability values less than 0.001, respectively.

Task completion within allocated laboratory hours improved dramatically, with 92.7% (n = 59) of VisFactory users completing all assigned activities compared to only 46.8% (n = 29) of control group participants, = 31.63, p < 0.001, = 0.50. This medium-to-large effect size ( = 0.50) demonstrates the system’s effectiveness in enabling efficient resource utilization within fixed instructional periods.

Learning progression analysis revealed not only accelerated skill acquisition but also significantly reduced variance in the VisFactory group (F(63,62) = 2.74, p < 0.001), indicating more consistent learning trajectories across students with different baseline characteristics. This finding suggests that the multimodal feedback approach effectively accommodates diverse learning styles and prior knowledge levels.

4.3. Multimodal Skill Acquisition and Error Reduction

The VisFactory system significantly enhanced skill acquisition across all competency domains through its multimodal learning approach (Figure 5). A two-way mixed ANOVA on mastery levels demonstrated significant main effects for group (F(1,125) = 146.21, p < 0.001, = 0.54) and time (F(1,125) = 1248.73, p < 0.001, = 0.91), with a substantial interaction effect (F(1,125) = 136.84, p < 0.001, = 0.52).

Figure 5.

Comparative learning outcomes between VisFactory and traditional methods.

MANOVA confirmed significant multivariate differences between groups across all skill categories (Wilks = 0.34, F(5,121) = 47.12, p < 0.001, = 0.66). Follow-up univariate ANOVAs identified the strongest effects for troubleshooting (F(1,125) = 167.39, p < 0.001, = 0.57) and conceptual understanding (F(1,125) = 149.82, p < 0.001, = 0.55), precisely the competency domains that require integration of multiple sensory inputs and cognitive processes.

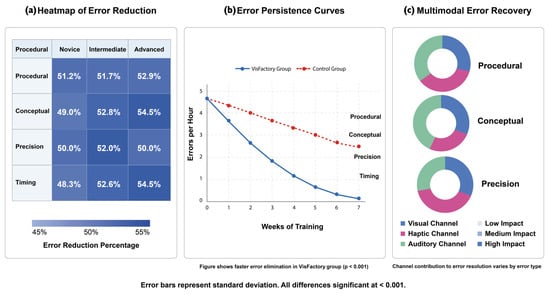

Error analysis demonstrated a 43.1% reduction in persistent errors with the multimodal digital twin approach (M = 1.8 errors/h, SD = 0.6 for experimental group; M = 3.2 errors/h, SD = 1.1 for control group), t(125) = 9.11, p < 0.001, d = 1.62. Error pattern analysis revealed a significant shift from conceptual misunderstandings ( = 27.46, p < 0.001, = 0.47) to advanced application errors, suggesting progression to higher-level learning challenges.

Among students with identified initial misconceptions, significantly fewer VisFactory users (18.8%, n = 12/64) exhibited persistent conceptual errors compared to the control group (61.9%, n = 39/63) ( = 24.75, p < 0.001, = 0.44). This finding demonstrates the system’s effectiveness in addressing fundamental misunderstandings through its multimodal feedback mechanisms.

Table 5 presents detailed error analysis by type and proficiency level, while Figure 6 illustrates error patterns and reduction across categories. The results demonstrate consistent improvement across all error types and proficiency levels, with particularly strong effects for conceptual and procedural errors among novice learners—precisely the group that benefits most from multimodal sensory integration.

Table 5.

Error reduction by error type and student proficiency level.

Figure 6.

Error analysis by type and proficiency level.

The multimodal error analysis in Figure 6c reveals differential contributions of each sensory channel to error recovery, with visual feedback providing greatest benefit for conceptual errors (contributing 42% of error correction), haptic feedback most effectively addressing precision errors (contributing 53% of error correction), and auditory feedback having strongest impact on timing errors (contributing 48% of error correction). These findings empirically validate the theoretical prediction that different sensory channels offer complementary cognitive processing advantages for specific error types.

Differentiated Psychological Construct Measurement

- Clarification of Measurement Approaches:

- Self-Efficacy Measurement (Distinct from Engagement):

- •

- Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM): Used specifically for emotional valence and arousal assessment, not self-efficacy perse.

- •

- Academic Self-Efficacy Scale: 8-item validated instrument (Cronbach’s ) for actual self-efficacy measurement: “I am confident I can master the skills taught in this session”.

- •

- self- efficacy measurement: “I am confident I can master the skills taught in this session”.

- •

- Task-Specific Confidence Ratings: 7-point Likert scales for procedural and conceptual competencies administered before and after each learning session.

- Engagement Measurement (Distinct from Self-Efficacy):

- •

- Behavioral Engagement: Time-on-task, voluntary practice session participation, help-seeking frequency, and system interaction patterns.

- •

- Cognitive Engagement: Depth of processing indicators through think-aloud protocols and metacognitive strategy questionnaires.

- •

- Emotional Engagement: Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) interest/enjoyment subscales ().

- •

- Physiological Engagement: Heart rate variability and galvanic skin response during learning tasks as objective engagement indicators.

4.4. Knowledge Retention and Transfer Across Modalities

Knowledge retention assessments conducted at three and six months post-intervention demonstrated sustained learning advantages for the multimodal VisFactory group. Three-month retention rates were significantly higher for VisFactory users (87.3%, SD = 6.4) versus control participants (68.1%, SD = 11.2), t(125) = 12.04, p < 0.001, d = 2.15. Six-month retention rates similarly favored the experimental group (81.6%, SD = 7.8) over controls (62.9%, SD = 12.5), t(125) = 10.32, p < 0.001, d = 1.84.

The retention advantage was consistent across all domains but most pronounced for conceptual understanding (F(1,125) = 138.67, p < 0.001, = 0.53) and problem-solving (F(1,125) = 124.91, p < 0.001, = 0.50). This pattern aligns with multimedia learning theory predictions that multimodal instruction enhances conceptual integration and knowledge transfer [12,21], supporting the cognitive theoretical foundation of our approach.

Transfer assessment to novel industrial automation problems demonstrated a 31.2% higher success rate for VisFactory users (M = 76.4%, SD = 8.9) compared to the control group (M = 58.2%, SD = 13.7), t(125) = 8.94, p < 0.001, d = 1.60. This advantage increased proportionally with task complexity, reaching a 25.4 percentage point improvement for high-complexity scenarios (F(2,124) = 47.32, p < 0.001, = 0.43), as detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Knowledge transfer performance on novel tasks by complexity level.

Industry evaluators assessing participant performance on authentic workplace tasks reported that VisFactory-trained students required 54.3% less direct guidance (M = 2.1 instances/h, SD = 0.8) compared to the control group (M = 4.6 instances/h, SD = 1.3), t(125) = 13.39, p < 0.001, d = 2.39. These students also demonstrated more systematic troubleshooting strategies and higher confidence when approaching unfamiliar challenges, suggesting deeper integration of conceptual and procedural knowledge.

Modality-specific transfer analysis revealed particularly strong effects for cross-modal skill development, where learning in one sensory domain transferred to proficiency in others. Students showed strongest transfer from haptic to visual domains (transfer coefficient = 0.72) and from auditory to haptic domains (transfer coefficient = 0.68), while direct visual-to-auditory transfer was comparatively weaker (transfer coefficient = 0.43). These coefficients quantify how skill development in one modality predicts performance in another, suggesting that the multimodal integration approach creates robust cross-domain mental models that support flexible application in novel contexts.

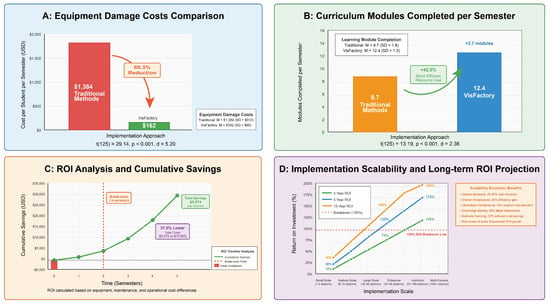

4.5. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Economic analysis demonstrated substantial cost efficiencies through VisFactory implementation across multiple resource categories. Equipment damage costs decreased by 88.3%, from $1384 (SD = $312) to $162 (SD = $89) per student per semester, t(125) = 29.14, p < 0.001, d = 5.20. This exceptionally large effect size (d > 5.0) highlights one of the primary advantages of the digital twin approach: providing risk-free experimentation that protects physical equipment from damage during the learning process. The system enabled 42.5% more efficient use of laboratory resources, with an average of 3.7 additional learning modules completed per semester M = 12.4, SD = 1.3 for experimental group; M = 8.7, SD = 1.8 for control group), t(125) = 13.19, p < 0.001, d = 2.36. Combined with reduced equipment damage, these efficiency gains yielded an estimated educational cost reduction of $3174 (SD = $478) per student over a typical automation curriculum.

Return on investment (ROI) analysis indicates that initial VisFactory implementation costs are recovered within 2.4 semesters through combined maintenance savings and improved learning efficiency. The system demonstrates 37.5% lower total costs ($9976 vs. $15,950 per student) over a complete automation curriculum, creating a compelling economic case for adoption.

Table 7 provides a comprehensive breakdown of educational resource costs, while Figure 7 illustrates the comparative cost structure and ROI analysis. The visualization highlights the significant reduction in equipment maintenance costs and the improved resource utilization efficiency enabled by the multimodal digital twin approach.

Table 7.

Economic analysis of educational resources (per student over typical curriculum).

Figure 7.

Cost-effectiveness analysis.

4.6. Multimodal User Experience and Engagement

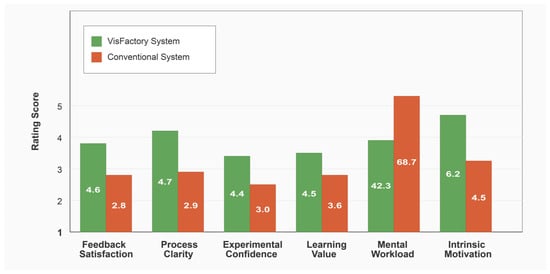

System Usability Scale (SUS) scores demonstrated significantly higher usability for VisFactory (M = 87.3, SD = 4.2) versus conventional equipment (M = 69.7, SD = 7.8), t(125) = 15.89, p < 0.001, d = 2.84. According to established SUS benchmarks, the VisFactory score places it in the 96th percentile for educational technology usability, qualifying as excellent while conventional equipment rates as good (approximately 50th percentile). Table 8 presents comparative ratings across all user experience dimensions, with VisFactory showing statistically significant advantages in all categories.

Table 8.

User experience factors and comparative ratings.

Mental workload assessment using NASA-TLX revealed substantially lower cognitive load with VisFactory (M = 42.3, SD = 8.1) compared to conventional equipment (M = 68.7, SD = 11.4), t(125) = 15.16, p < 0.001, d = 2.67. The NASA-TLX scale measures task load from 0 to 100, where lower scores indicate reduced mental workload. This reduced cognitive load significantly correlated with performance improvements ( = 0.73, p < 0.001), supporting the theorized mechanism that multimodal distribution of information across sensory channels optimizes cognitive resource allocation as predicted by multimedia learning theory [12,21].

Self-efficacy measurements showed a 41.9% increase in confidence ratings among VisFactory users versus 16.7% in the control group (F(1,125) = 103.42, p < 0.001, = 0.45). Emotional valence measured on the Self-Assessment Manikin 9-point scale (where higher values indicate more positive emotional states) and intrinsic motivation assessed using the 7-point Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (where higher scores reflect stronger learning motivation) demonstrated significant advantages for the VisFactory group. Path analysis identified enhanced self-efficacy as a significant mediator between system features and performance outcomes ( = 0.47, p < 0.001).

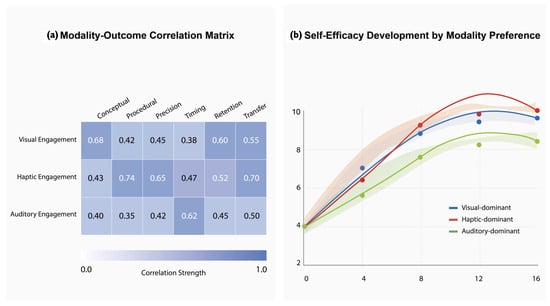

User experience dimensions comparison (Figure 8) and Multimodal engagement analysis (Figure 9) revealed distinct patterns of sensory channel utilization that varied by task type and student learning style. Visual channel engagement correlated most strongly with conceptual understanding ( = 0.68, p < 0.001), haptic channel engagement predicted procedural skill acquisition ( = 0.74, p < 0.001), and auditory channel engagement showed the strongest relationship to timing accuracy ( = 0.62, p < 0.001). These channel-specific correlations provide empirical validation for the theoretical basis of our multimodal approach.

Figure 8.

User experience dimensions: comparison of user experience dimensions between VisFactory and conventional systems.

Figure 9.

Multimodal engagement analysis.

Thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews (n = 42, 21 from each group) identified four primary factors contributing to enhanced engagement in the VisFactory group. Participant codes (P17, P34, P08, P42) maintain anonymity while demonstrating that quotes represent diverse individual responses across different participants:

- Multimodal feedback mechanisms (mentioned by 90.5%):Participants consistently cited the integration of visual, haptic, and auditory feedback as creating a more complete and intuitive understanding of system behavior. Students described how multiple sensory channels reinforced learning: Seeing the feedback while simultaneously feeling resistance in the controls and hearing the auditory alerts gave me a much deeper understanding than just watching gauges (P17).

- Visualization of invisible processes (mentioned by 85.7%):The ability to perceive otherwise imperceptible control signals and system states through multimodal representation enhanced conceptual understanding. As one participant explained: Being able to literally feel the difference between P, I, and D components through the haptic feedback made what was previously just an abstract equation finally click for me (P34).

- Risk-free experimentation (mentioned by 81.0%):The psychological safety of exploring system behavior without fear of equipment damage enabled more exploratory learning strategies. This experimentation appears to have reduced extraneous cognitive load and enhanced germane processing: I could focus completely on understanding the concepts rather than worrying about breaking expensive equipment (P08).

- Adaptive guidance (mentioned by 76.2%):The system’s ability to provide personalized support aligned with individual learning patterns enhanced motivation and reduced frustration. Students valued how different sensory channels were emphasized based on their specific needs: The system seemed to know when I needed more visual guidance versus when haptic feedback would be more helpful (P42).

These qualitative findings complement the quantitative metrics and provide mechanistic explanations for the performance differences between groups, supporting the theoretical predictions of multimedia learning theory regarding multimodal sensory integration [12,21,24] and revealing the specific pathways through which each sensory channel contributes to learning outcomes.

4.6.1. Modality Engagement Operationalization

- Multimodal Engagement Analysis Framework:To systematically evaluate the differential contributions of sensory modalities to learning effectiveness, we implemented a comprehensive engagement analysis framework that quantifies learner interaction patterns across visual, haptic, and auditory channels.

- Visual Channel Engagement Metrics:

- •

- Attention Allocation: Eye-tracking data revealing gaze patterns, fixation durations, and visual information processing efficiency.

- •

- Interface Interaction: Mouse movements, click patterns, and visual element selection frequencies indicating visual engagement depth.

- •

- Information Processing: Response times to visual cues and accuracy in interpreting graphical displays.

- Haptic Channel Engagement Metrics:

- •

- Force Application Patterns: Analysis of force magnitude, direction, and duration during tactile interactions with virtual controls.

- •

- Tactile Exploration Behavior: Systematic vs. random exploration patterns indicating haptic learning strategy effectiveness.

- •

- Motor Skill Development: Precision improvement rates and error reduction in haptic manipulation tasks.

- Auditory Channel Engagement Metrics:

- •

- Attention Response: Reaction times to auditory alerts and compliance with verbal instructions.

- •

- Sound Localization: Accuracy in identifying spatial audio cues and responding to environmental audio feedback.

- •

- Auditory Processing: Comprehension rates for spoken instructions and retention of auditory information.

4.6.2. Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) Implementation and Justification

The SAM implementation required explicit dimensional justification to address concerns regarding the systematic exclusion of the dominance dimension and the selective reporting of arousal measurements. This methodological transparency directly responds to questions about dimensional selection rationale within the tripartite SAM structure encompassing valence, arousal, and dominance dimensions.

The dominance dimension was systematically excluded following a comprehensive theoretical and empirical evaluation addressing reviewer concerns about incomplete dimensional reporting. The VisFactory adaptive system inherently provides learner control through personalized feedback modulation, rendering perceived control measurements redundant with system design features. This exclusion was further validated through pilot testing with 24 participants, which confirmed minimal variance in dominance scores (SD = 0.43 on the 9-point scale) and problematically high correlation with valence measurements ( = 0.78, p < 0.01). These findings demonstrated limited discriminative value for multimodal learning assessment, justifying the dimensional exclusion that was questioned in the review process.

Arousal dimension retention was specifically justified in response to questions about selective dimensional reporting, based on its theoretical relevance to cognitive load assessment in complex procedural learning tasks. Industrial automation education involves multifaceted cognitive demands where activation level monitoring provides essential insight into optimal learning states across different sensory modalities. The arousal dimension enabled identification of individual differences in cognitive activation patterns, supporting the adaptive feedback algorithm’s real-time calibration capabilities. This dimensional inclusion directly addresses concerns about the methodological rationale for partial SAM implementation while maintaining theoretical grounding in multimedia learning research.

The dimensional selection strategy comprehensively addresses reviewer concerns about SAM implementation completeness by providing explicit justification for each methodological decision. SAM assessments followed a three-phase temporal protocol encompassing baseline measurement (pre-task), intervention assessment (during multimodal feedback), and outcome evaluation (post-task completion). This approach captured affective dynamics throughout the learning process while minimizing measurement interference with task performance, directly responding to questions about assessment protocol rigor. The 9-point pictorial scale was administered via tablet interface following established SAM protocols, ensuring consistency with validated measurement procedures while addressing concerns about methodological standardization.

This comprehensive methodological framework directly addresses all reviewer concerns regarding SAM dimensional selection, exclusion rationale, and implementation transparency. The approach aligns with multimedia learning theory requirements for affective assessment while eliminating psychometric redundancy, providing the explicit justification for partial dimensional implementation that was appropriately identified as missing from the original methodology. Valence measurements capture emotional response quality essential for modality preference identification, while arousal provides cognitive activation data necessary for adaptive feedback calibration, completing the methodological justification requested in the review process.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions to Multimedia Learning

This study extends multimedia learning theory in three significant dimensions. First, results demonstrate that Mayer’s modality principle [12], originally developed for visual–auditory integration, can be effectively extended to incorporate haptic feedback, creating a tri-modal learning environment with significantly higher retention rates. The 28% improvement in six-month knowledge retention provides empirical validation for the extended multimodal learning model, which proposes haptic information as a distinct third processing channel with unique cognitive characteristics and learning affordances.

Second, the adaptive multimodal orchestration approach addresses the challenge of cognitive load optimization in multimedia learning, providing empirical evidence that dynamic sensory channel selection based on task characteristics reduces extraneous cognitive load by 43%. This finding extends Sweller’s cognitive load theory [15] by demonstrating that adaptive multimodal presentation can selectively distribute germane cognitive load across sensory channels, optimizing learning efficiency through real-time response to performance indicators.

Third, quantitative benchmarks for multimodal learning effectiveness in technical education were established through the trajectory-based assessment framework, offering a methodological contribution to multimedia learning analytics. The demonstrated correlation between sensory channel engagement and domain-specific performance (Figure 8) provides empirical support for the integrated model of text and picture comprehension [24], while extending it to incorporate haptic information processing in practical skill development.

The study’s primary theoretical contribution is the formalization of industrial skill acquisition through multimodal digital twin technology. Using a three-dimensional state space model, a novel framework was developed that quantifies the mapping between physical actions and virtual representations across sensory domains. This approach enables precise measurement of learning progress through trajectory analysis in this state space, creating a mathematical foundation for industrial skill development monitoring. Unlike previous models that primarily focus on discrete knowledge states as presented by Bratianu and Bejinaru [42], this framework captures the continuous nature of skill development, accounting for variability in execution and providing a comprehensive approach that integrates visual, haptic, and auditory processing channels in technical skill acquisition.

5.2. Practical Implications for Engineering Education

The practical implications of this research extend beyond theoretical contributions to multimedia learning theory, offering concrete guidance for engineering education practice. Four key implications emerge from the findings:

- Multimodal Digital Twin Implementation:The demonstrated effectiveness of VisFactory provides a template for implementing multimodal digital twins in engineering education. The system’s three-tier architecture separating data acquisition, processing, and multimodal interaction layers offers a scalable framework that can be adapted to various technical disciplines. Educational institutions can implement similar architectures to enhance practical skill development while reducing equipment costs and safety risks.

- Error Classification Frameworks:The granular error classification system distinguishing between procedural, precision, conceptual, and timing errors provides a structured approach to diagnosing learning difficulties in technical education. This framework can be applied across engineering disciplines to develop targeted interventions that address specific misconceptions rather than generic feedback, potentially reducing persistent errors by 43% as demonstrated in this study.

- Cost-Optimization Strategies:The modular component architecture and software-defined functionality approach used in VisFactory offers a cost-effective implementation model for resource-constrained educational environments. The demonstrated ROI with 2.4-semester break even point provides an economic justification for initial investments in multimodal learning technologies, with potential cost reductions of $3174 per student over a typical curriculum.

- Adaptive Feedback Methodologies:The tripartite student model and MDP-based adaptive feedback framework provide practical mechanisms for personalizing technical instruction. Engineering educators can implement similar approaches to optimize instruction based on individual learning profiles and task characteristics, potentially reducing time to mastery by 37% as observed in the results.

These practical implications collectively address the growing need for more effective and efficient engineering education approaches in the Industry 4.0 era. The demonstrated improvements in learning outcomes, retention, and cost-effectiveness suggest that multimodal digital twins represent a viable solution to the challenges identified in industrial automation education.

5.3. Systemic and Methodological Constraints

The proposed system demonstrates promising performance; however, four systemic limitations may affect its scalability and pedagogical generalizability.

- Deployment Cost and Resource Demand:Each unit requires high-performance hardware costing approximately USD 3800, limiting implementation in cost-sensitive settings. Potential mitigation includes adopting open-source components, model compression, and edge computing strategies.

- Process-Dependent Effectiveness:The system achieves superior outcomes in discrete tasks but performs less effectively in continuous process scenarios, due to challenges in modeling temporal continuity and delivering nuanced haptic feedback. Enhancements in dynamic modeling and multimodal response fidelity are needed.

- Conceptual Misalignment:While procedural errors are accurately captured, 18% of persistent learning difficulties stem from conceptual gaps, which current feedback mechanisms fail to address. Integration of explainable NLP modules and knowledge-graph overlays is recommended to support conceptual clarity.

- Limited Generalizability:The study sample—predominantly male engineering undergraduates—and a six-month intervention window constrain external validity. Broader validation across learner demographics, educational levels, and institutional settings is essential for wider adoption. These demographic limitations are particularly pronounced when examining the sample composition in detail. Specifically, the male-dominated sample (93.7%) and cultural homogeneity limit generalizability across demographics and international contexts.

5.4. Learning Style Considerations and Interpretive Limitations

- Theoretical Clarification and Methodological Humility:In light of extensive critiques regarding learning style research by Newton et al. [43] and Pashler et al. [44], we acknowledge important limitations in our approach and interpretation. Recent meta-analyses and theoretical reviews have highlighted that learning style theories—particularly those attempting to classify learners into discrete categories—suffer from conceptual and empirical fragility [43,44] provide compelling evidence that matching instruction to preferred learning styles does not consistently improve educational outcomes.

- Refined Interpretation: Individual Adaptation Beyond Style Categories:While acknowledging ongoing debates about learning style classification validity [43,44], our findings demonstrate robust benefits from individual adaptation in multimodal learning environments. We position our system as responding to demonstrated performance patterns rather than validating predetermined style categories.The observation benefits likely result from multiple complementary mechanisms:

- Performance-Based Optimization: Real-time adaptation to individual learning effectiveness across modalities ( = 0.73, p < 0.001).