Abstract

The world’s population is aging and, as populations age, they exhibit an increased prevalence of chronic diseases, which can reduce the independence of elderly individuals. The set of initiatives known as aging in place, a common policy response to the aging population, is preferred by both the elderly population and policymakers. Aging in place is a broad and multifaceted topic that involves multiple stakeholders and academic disciplines. A science map of the literature on aging in place can help researchers pinpoint their efforts and help policymakers make informed decisions. Thus, this study maps the scientific landscape of the aging-in-place literature. This review used bibliometric analysis to examine 3240 publications on aging in place indexed in the Web of Science. Using VOSviewer 1.6.20, it conducted various analyses, including a citation analysis and an analysis of the co-occurrence of author-provided keywords. The study identified key research areas, leading countries, institutions, and journals, central publications, and the temporal evolution of themes in the literature. Based on its keyword co-occurrence analysis, the study identified five major research-area clusters: (1) aging-in-place facilitators, (2) age-friendly communities, (3) housing, (4) assistive technologies, and (5) mental health. This study improves the understanding of the various interdisciplinary factors that have influenced the research on aging in place. By making this research more accessible, the study can help researchers and policymakers navigate the extensive information on aging in place and complex relationships more effectively.

1. Introduction

The world’s population is aging due primarily to (1) reduced mortality rates, which have resulted from improved public health, and (2) declining fertility rates [1]. As populations age, they exhibit an increased prevalence of chronic diseases, such as ischemic heart disease, diabetes, osteoarthritis, sensory impairments, and dementia [2]. Aging individuals are also more likely to experience multimorbidity (i.e., having multiple chronic conditions simultaneously), which can significantly impact their physical functions and overall quality of life [3]. In addition to such progressive impairments in various physical functions, aging is associated with a range of psychosocial problems, such as loneliness and depression, e.g., [4]. These factors diminish the ability of elderly individuals to perform the activities of daily living independently as well as their mental health, leading to poorer quality of life and increased healthcare costs, and often necessitating a move into a care institution [5].

Institutional care is often perceived as dehumanizing and detrimental to social interactions [6]. Additionally, relocating can have negative psychological effects on elderly individuals, such as stress, loneliness, and depression [7]. To address the challenges associated with an aging population, policymakers have promoted initiatives for aging in place rather than moving older adults into specialized housing or care facilities. “Aging in place” refers to the ability to live independently, safely, and comfortably in one’s own home for as long as possible, regardless of age, income, or physical abilities [1].

Aging in place is a preferred option for elderly individuals because they feel attached to their homes and communities [8]. When older adults age in place, the independence they experience can help them maintain their sense of identity and contribute to their self-reliance, self-management, and self-esteem [9]. Thus, aging in place contributes to the overall well-being of older people [10]. From the perspective of policymakers, aging in place is a better option than institutional care because aging in place is less expensive in the long term [11].

A variety of factors contribute to successful aging in place, including policies [12], home environments [13], communities and neighborhoods [14], transportation [15], facilitating physical activity [16], promoting social interactions [17], technology [18], and caregiving [19]. Hence, aging in place involves multiple disciplines and stakeholders.

Considering the breadth of the topic of aging in place, its multidisciplinary nature, and the variety of stakeholders aging-in-place initiatives involve, a science map of the literature on aging in place offers a number of benefits. First, it enables the identification of key research areas and their evolution over time. Second, it sheds light on interdisciplinary connections, which can point to opportunities for interdisciplinary research and thus lead to new insights and innovations. Third, by providing a comprehensive overview of what has been studied and published, it conserves resources by preventing duplication of effort in various disciplines. Fourth, it makes knowledge more accessible to both new and experienced researchers, facilitating their navigation of vast amounts of information. Lastly, policymakers and stakeholders can use a map of the research landscape to make more informed decisions regarding aging in place.

Various types of literature review, such as systematic, scoping, integrative, and thematic reviews, have been instrumental in mapping the literature on aging in place, e.g., [20,21,22,23]. For instance, in a scoping review, Pani-Harreman et al. [23] reviewed 34 articles and identified five major themes in the aging-in-place literature: (1) place, (2) social network, (3) support, (4) technology, and (5) personal characteristics. Similarly, Peek et al. [22] systematically reviewed the literature and identified 61 articles that addressed factors influencing the acceptance of technologies used to facilitate aging in place.

Literature reviews can offer in-depth analysis, detailed interpretation, and critical evaluation of research findings, methodologies, and theoretical frameworks but, as Donthu et al. [24] argued, they have several limitations that can restrict their applicability. First, the scope of literature reviews is often narrow and highly specific, which may limit their ability to address broader topics. Second, because the reviewing process is often conducted manually, the number of articles included in literature reviews is typically small (roughly 40–300 articles) to keep the reviewing process manageable. Third, the identification of themes in literature reviews relies on qualitative techniques, which can introduce interpretation bias into the conclusions.

Bibliometric analysis, which relies on quantitative methods, can address the limitations of traditional literature reviews by providing a broad overview of the research landscape and complementing the depth offered by literature reviews. The automated tools and algorithms used in bibliometric analysis can process vast amounts of data quickly, whereas literature reviews are often time-consuming and labor-intensive. As the volume of published research grows, bibliometric analysis remains scalable, whereas literature reviews may become increasingly impractical. Bibliometric analysis uses quantitative data, such as citation counts, the h-index, impact factors, and coauthorship networks, to provide objective measures of the influence and reach of studies. Consequently, bibliometric analysis has gained popularity across various disciplines in recent years, e.g., [25,26]. This increased popularity can be attributed to (1) the availability of metadata from databases such as the Web of Science and Scopus, and (2) computer programs like VOSviewer and Gephi, which facilitate bibliometric analysis [24].

Bibliometric analysis encompasses a variety of techniques, which can be categorized into two major types: performance analysis and science mapping. Performance analysis evaluates the research output and impact of different entities, such as individual researchers, institutions, journals, and countries. Science mapping, also known as scientific visualization, reveals the structural and dynamic aspects of scientific research. Which of these analyses a study uses depends on the research questions of interest.

For example, Oladinrin et al. [27] conducted a bibliometric analysis of the literature on aging in place, focusing mainly on performance analysis. Although their study included co-occurrence analysis—a component of science mapping—they did not identify themes in their data, which limited the scope of their contribution. In contrast, Seo and Lee’s [28] bibliometric study of aging in place incorporated both performance analysis and science mapping. However, their analysis was limited to residential environments. Although residential spaces are a crucial aspect of aging in place, it could be argued that the study may not have included other important factors, such as policies and communities. A bibliometric study that included such topics would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the literature.

Thus, considering all the factors that influence aging in place and employing appropriate types of analysis are crucial for creating a comprehensive and meaningful map of the scientific landscape of aging-in-place literature. The gaps in the existing research outlined above prompted the current paper.

This study provides a comprehensive map of the scientific landscape of aging-in-place literature. Accordingly, the study’s research questions are as follows:

- What are the leading countries, institutions, and journals in the field of aging in place?

- What are the central publications in the citation network of aging-in-place research?

- What are the most frequently occurring keywords, and how are they interconnected?

- How do these keywords evolve over time?

- What are the major themes in the literature on aging in place?

By using a dataset that is larger than that employed by previous studies and by not limiting the scope of the research, this study provides the most comprehensive map of the aging-in-place literature to date.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying Relevant Publications

To identify relevant articles, a search was conducted in the Web of Science Core Collection. This database was selected over others (such as Scopus and OpenAlex) because it yielded more relevant articles and offered more complete metadata (e.g., author-provided keywords). Various forms of the term aging in place (e.g., ageing in place and aging-in-place) were used to search in the title and author-provided-keywords fields. No restrictions were applied to this search (i.e., regarding time, geography, or document type) other than English as the document language.

The search, conducted in July 2024, yielded 3240 records published between 1908 and 2023. Some of these records were unrelated to the topic of aging in place. To streamline the review process, we did not manually screen the records for relevance. Instead, we used VOSviewer 1.6.20, a bibliometric software tool developed by van Eck and Waltman [29], to identify relevant papers and potential outliers. This automated method made the review process more manageable by eliminating the need for manual screening of all identified records.

VOSviewer 1.6.20 [29] provides five analysis methods for determining the relatedness of items (e.g., keywords, countries, and papers): (1) coauthorship analysis, (2) co-occurrence analysis, (3) citation analysis, (4) bibliometric coupling analysis, and (5) co-citation analysis. For an overview of these bibliometric-analysis techniques and examples of each, see Donthu et al. [24]. The current paper used citation analysis and co-occurrence analysis, which the following section explains.

2.2. Data Analysis

To identify the leading countries, institutions, and journals, three metrics were used: (1) total publications (TP), (2) total citations (TC), and (3) the average impact of each publication (TC/TP). Bibliometric studies often use TP as a metric of productivity. TC can indicate scholarly influence or impact. TC/TP is more normalized than TC and allows for comparisons that consider both quality and quantity of output; TC/TP can highlight entities that produced fewer but more influential papers. Using these metrics, the leading countries, institutions, and journals were ranked.

Citation analysis was used to determine the leading publications in the field of aging in place. In citation analysis, the relatedness of publications is determined based on the number of times they cite each other. This number is called the link count. Accordingly, publications with a higher link count are more central in the citation network than those with lower link counts. Using this method of analysis, outliers were filtered out, because irrelevant publications that found their way into the dataset would not have links with the publications on aging in place. Accordingly, the 20 most central publications in the citation network of aging in place were ranked.

For keyword analysis, five types of analysis were performed: (1) identifying the most frequently occurring keywords, (2) examining temporal variability in keywords, (3) graphical network mapping of keywords, (4) identifying clusters of keywords, and (5) identifying the most frequently occurring keywords in each cluster. Before conducting any of these analyses, the data from the Web of Science were cleaned by creating a thesaurus that enabled the use of one term for multiple forms of the same keyword (e.g., different spellings or singular and plural forms) or concept (e.g., adolescence and adolescent). Some general terms, such as the names of countries and research methods (e.g., literature review), were removed from the analysis.

For the examination of temporal variability in keywords, the most frequently occurring keywords in three time periods were examined to identify the evolution of research foci in the literature: 2010–2014, 2015–2019, and 2020–2024. These time periods were selected through several cycles of refinement; these iterations led to the identification of time frames that resulted in a sufficient number of keywords on the topic of aging in place, which enabled a meaningful temporal analysis.

For the graphical network mapping of keywords, co-occurrence analysis was performed in VOSviewer 1.6.20 [29]. In this paper’s co-occurrence analysis, the unit of analysis was the keywords provided by the authors of the identified publications. The graph consists of nodes and links. The size of the nodes represents the frequency of keyword occurrence, and a line between the nodes indicates that those keywords were mentioned together in a document. The thickness of the lines represents the number of instances of co-occurrence (i.e., the strength of the link); the greater the number of co-occurrences, the thicker the line. To enhance the readability of the diagram, the number of lines shown can be adjusted by focusing on the links with the highest link strengths. Hence, the lack of a visual link between two nodes in the diagram may not necessarily indicate the absence of an actual link. The distance between any two nodes reflects the similarity or relatedness of the items. VOSviewer 1.6.20 [29] applies a clustering algorithm to the network. This algorithm is based on the idea of maximizing a modularity-based quality function. The algorithm iteratively adjusts the assignment of keywords to clusters to maximize the quality function, resulting in a partition of keywords into clusters. Different clusters are indicated using different colors, making it easier to identify and interpret the clusters in the visual representation.

Lastly, to facilitate the qualitative analysis of each cluster, the most frequently occurring keywords in each cluster were ranked. Using the graphical network mapping of keywords and the ranking of keywords in each cluster, a theme was assigned to each cluster.

3. Results

3.1. Leading Countries

Table 1 presents the 10 leading countries ranked according to productivity, measured by TP. The United States ranked first, followed by Canada, England, and China. To assess the impact of the published papers, two measures were used: TC and TC/TP. Based on the TC metric, the United States ranked first, followed by Canada, England, and Australia. However, based on the TC/TP metric, New Zealand ranked highest, followed by Russia, the Netherlands, and England.

Table 1.

The 10 leading countries ranked according to productivity (TP).

3.2. Leading Institutions

Table 2 presents the 20 leading institutions ranked by productivity (TP), research impact (TC), and the average impact of each publication (TC/TP). The University of Missouri, the University of Michigan, and the University of Toronto led in terms of TP on the topic of aging in place.

Table 2.

The 20 leading institutions ranked by productivity (TP), research impact (TC), and the average impact of each publication (TC/TP).

In terms of impact (TC), the University of Auckland, Tilburg University, and the University of Missouri ranked at the top. In terms of TC/TP, the University of Utrecht, Tilburg University, and the University of Auckland ranked highest.

3.3. Leading Journals

Table 3 shows the 10 leading journals on the topic of aging in place based on productivity (TP). The top three journals in terms of productivity were The Gerontologist, followed by the Journal of Aging and Environment (formerly known as the Journal of Housing for the Elderly) and the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Table 3.

The 10 leading journals on the topic of aging in place based on productivity (TP).

Some journals in Table 3 are relatively new, which affects their citation counts and average impact per publication (TC/TP). For example, Innovation in Aging, launched in 2017, has a significantly lower average impact per publication (TC/TP) compared to older journals like The Gerontologist, which was established in 1961.

In terms of impact (TC), The Gerontologist ranked highest, followed by the International Journal of Medical Informatics and Ageing & Society (Table 4). With respect to average impact per publication (TC/TP), the International Journal of Medical Informatics, Social Science and Medicine, and Health and Social Care in the Community were the leading journals (Table 5).

Table 4.

The 10 leading journals on the topic of aging in place based on impact (TC).

Table 5.

The 10 leading journals on the topic of aging in place based on average impact of each publication (TC/TP).

3.4. Central Publications

Using citation analysis, the relatedness of papers was determined based on the number of times they cited each other. Subsequently, papers were ranked based on the number of links they had in the citation network. Table 6 lists the top 20 papers.

At the top of this list was a paper by Wiles et al. [8] published in The Gerontologist, which was ranked as the leading journal on the topic of aging in place in terms of both productivity and impact (see Table 3 and Table 4). Using qualitative methods (i.e., focus groups and interviews), Wiles et al. [8] explored the meaning of aging in place and elderly individuals’ perspectives on the ideal place to do so in New Zealand. Wiles coauthored two other papers [30,31] that ranked among the 20 most central publications (Table 6).

Four of the papers listed in Table 6 were literature reviews [20,21,22,23]; these papers could serve as sources for a more in-depth exploration of the topic. For example, the second paper on the list was a systematic literature review by Peek et al. [22], published in the International Journal of Medical Informatics (the second most influential journal on the topic). That paper reviewed factors that play a role in the acceptance of technologies used to support aging in place. Another paper coauthored by Peek [32], which ranked 16th among the top 20 papers, explored the use of technologies to support aging in place in the Netherlands. Two of the other papers listed in Table 6, including another literature review, explored the use of technology to support aging in place [18,20].

Table 6.

The 20 most central publications in the citation network of aging-in-place research.

Table 6.

The 20 most central publications in the citation network of aging-in-place research.

| Rank | Citation | Publication Title | Links Count | TC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [8] | The meaning of “aging in place” to older people | 25 | 984 |

| 2 | [22] | Factors influencing acceptance of technology for aging in place: A systematic review | 20 | 603 |

| 3 | [31] | Geographical Gerontology: The constitution of a discipline | 20 | 146 |

| 4 | [33] | The process of mediated aging-in-place: A theoretically and empirically based model | 15 | 193 |

| 5 | [23] | Definitions, key themes and aspects of ‘ageing in place’: A scoping review | 15 | 97 |

| 6 | [34] | Moving beyond ‘ageing in place’: Older people’s dislikes about their home and neighbourhood environments as a motive for wishing to move | 15 | 92 |

| 7 | [35] | Ageing in place in the United Kingdom | 14 | 221 |

| 8 | [30] | Re-spacing and re-placing gerontology: Relationality and affect | 14 | 100 |

| 9 | [18] | Ageing-in-place with the use of ambient intelligence technology: Perspectives of older users | 13 | 161 |

| 10 | [36] | Conducting research on home environments: Lessons learned and new Directions | 12 | 202 |

| 11 | [37] | Safe as houses? Ageing in place and vulnerable older people in the UK | 11 | 109 |

| 12 | [38] | Older people’s decisions regarding ‘ageing in place’: A Western Australian case study | 11 | 94 |

| 13 | [39] | Aging in place and the places of aging: A longitudinal study | 11 | 63 |

| 14 | [10] | The ideal neighbourhood for ageing in place as perceived by frail and non-frail community-dwelling older people | 10 | 76 |

| 15 | [14] | Photovoicing the neighbourhood: Understanding the situated meaning of intangible places for ageing-in-place | 10 | 51 |

| 16 | [32] | Older adults’ reasons for using technology while aging in place | 9 | 270 |

| 17 | [21] | The quality of life of older people aging in place: A literature review | 9 | 127 |

| 18 | [12] | Aging in place: From theory to practice | 9 | 114 |

| 19 | [20] | Smart homes and home health monitoring technologies for older adults: A systematic review | 8 | 352 |

| 20 | [40] | The impact of age, place, aging in place, and attachment to place on the well-being of the over 50s in England | 8 | 124 |

Note. TC = total citations

3.5. Keyword Analysis

This section reports three types of keyword analysis: (1) analysis of the most frequently occurring author-provided keywords, (2) analysis of the temporal evolution of author-provided keywords, and (3) network analysis and analysis of clusters of author-provided keywords.

3.5.1. Most Frequently Occurring Author-Provided Keywords

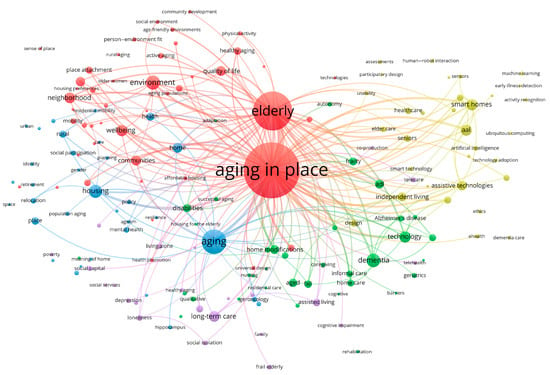

In the co-occurrence analysis, which was performed in VOSviewer 1.6.20 [29], the relatedness of keywords provided by the papers’ authors was determined based on the number of documents in which they co-occurred. After multiple iterations, a minimum occurrence value of 8 was selected; this value resulted in a manageable number of keywords and clear, meaningful clusters. The LinLog/modularity normalization method was chosen, because it results in more distinct clusters in the keyword–network layout. The clustering resolution was increased from the default value of 1 to that of 1.07 to enhance the distinctions between closely related clusters. This process resulted in the identification of the 40 most frequently occurring author-provided keywords (Table 7) and a keyword network with five clusters (Figure 1).

Table 7.

The 40 most frequently occurring author-provided keywords.

Figure 1.

The keyword network visualization, with five clusters, was created using VOSviewer 1.6.20. Each cluster is represented by a different color. This network is based on the co-occurrence analysis of the keywords provided by the authors. The size of the nodes represents the frequency of keyword occurrence, and a line between the nodes indicates that those keywords were mentioned together in a document. The thickness of the lines represents the number of instances of co-occurrence (i.e., the strength of the link); the greater the number of co-occurrences, the thicker the line.

Five major themes emerged from the qualitative examination of the 40 most frequently occurring author-provided keywords. First, two primary groups of people were evident in the list: elderly people and caregivers. Second, aging-friendly environments were discussed at various levels, including homes, communities, and cities. Third, the keywords pointed to health conditions that pose challenges for aging in place, including dementia, disabilities, frailty, and the risk of falls. Fourth, a prominent theme was the use of technology to support aging in place. Lastly, the keywords indicated potential outcomes, such as healthy aging, high quality of life, well-being, independent living, and place attachment.

3.5.2. Temporal Evolution of Author-Provided Keywords from 2010 to 2024

To examine the evolution of studies of aging in place, keywords were grouped according to their frequency of occurrence in three time periods: 2010–2014, 2015–2019, and 2020–2024 (Table 8). These time periods were selected through several cycles of refinement; these iterations led to the identification of time frames that resulted in a sufficient number of keywords on the topic of aging in place, which enabled a meaningful temporal analysis. Keywords from before 2010 were excluded from the analysis because their quantity was insufficient.

Table 8.

The 20 most frequently occurring author-provided keywords in three time periods: 2010–2014, 2015–2019, and 2020–2024.

Figure 2 shows how the ranking of keywords changed over time. The first three keywords—aging in place, elderly, and aging—maintained their ranking at the top of the list over time, because they are general terms central to the topic of aging in place.

Figure 2.

Temporal evolution of author-provided keywords from 2010 to 2024. NORC = naturally occurring retirement community; ADL = activities of daily living; AAL = ambient assisted living.

Over time, general terms moved down in the rankings, whereas more specific terms rose to the top. For example, the keyword home, which was among the top 20 keywords in 2010–2014, was not present in the later periods. Instead, the term smart homes appeared, indicating a focus on the integration of technology into home environments. Another example was the term place; it had been absent from the top 20 keywords since 2015, but place attachment emerged in 2020–2024.

Two terms that rose significantly in prominence over time were neighborhood and age-friendly cities and communities. This trend suggested a shift toward considering settings for successful aging in place that extended beyond the home environment. The ranking of the keyword dementia underwent a notable increase over time. Additionally, the rising ranking of keywords like well-being and healthy aging from 2020 to 2024 indicated a growing focus on the overall well-being of older adults.

3.5.3. Keyword Networks and Clusters of Author-Provided Keywords

Figure 1 illustrates the keyword network, representing each cluster with a different color. The size of the nodes corresponds to the frequency of keyword occurrences, and the lines between nodes indicate that those keywords were mentioned together in a document. The thickness of the lines represents the strength of the link; the thicker the line, the stronger the link. For enhanced readability, the figure shows only the top 200 lines in terms of link strength. Identifying the 10 most frequently occurring keywords in each cluster (see Table 9) facilitated the qualitative analysis of each cluster. The following paragraphs provide a detailed discussion of each cluster.

Table 9.

The 10 most frequently occurring author-provided keywords in each cluster.

Cluster 1: Aging-in-Place Facilitators. The first cluster, shown in green in Figure 1, included keywords related to factors that facilitate aging in place. These factors included technology, home modifications, informal care, and home care. They were associated with conditions that elderly individuals may face as they age, such as dementia, disability, and the risk of falls.

Cluster 2: Age-Friendly Communities. The second cluster, highlighted in red in Figure 1, focused on age-friendly communities and cities. The key terms in this cluster included place attachment, sense of place, belonging, and social support. Additionally, this cluster featured prominent keywords related to the positive outcomes of aging in place, such as quality of life, healthy aging, active aging, physical activity, and health promotion.

Cluster 3: Housing. The third cluster, highlighted in blue in Figure 1, focused on housing and homes. Two major themes emerged from this cluster: (1) relocation, which encompassed migration, and (2) health, including mental health.

Cluster 4: Assistive Technologies. Cluster 4, highlighted in yellow in Figure 1, focused on the use of technologies to support aging in place and elder care. The key terms in this cluster included smart homes, ambient assisted living, assistive technologies, gerontechnology, and the Internet of things. Notably, the inclusion of technology acceptance and technology adaptation as keywords indicated that, although these technologies can significantly enhance the independence, well-being, and overall quality of life of older adults, their minimal acceptance by the elderly population remains a crucial issue, e.g., [22].

Cluster 5: Mental Health. The fifth cluster, highlighted in purple in Figure 1, focused on mental health, encompassing concepts such as loneliness, living alone, social isolation, and depression.

4. Discussion

This study maps the scientific landscape of the literature on aging in place through a bibliometric analysis. The results highlight the multifaceted nature of aging in place, emphasizing the need for a multidisciplinary approach to understanding and addressing the diverse factors influencing successful aging in place. The study identifies key research areas, leading countries, institutions, and journals, central publications, and the temporal evolution of themes in the literature. These findings offer valuable insights into the current state of research and suggest several critical considerations for future work.

In our network analysis of the research on aging in place, we identify five major research-area clusters, each characterized by prevailing keywords and their interconnections. We label these clusters based on their dominant keywords as follows: (1) aging-in-place facilitators, (2) age-friendly communities, (3) housing, (4) assistive technologies, and (5) mental health.

As individuals age, their ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) independently can decline [41] due to physical [42] and cognitive limitations [43]. This makes caregiving an important factor in aging in place, which is also evident in Figure 1, as it is central to the aging-in-place facilitators cluster (cluster 1). For instance, Vreugdenhil [44] identified dementia, caregiving, and informal care as critical concerns related to aging. Caregiving can range from formal arrangements, like long-term care facilities to informal support through home care e.g., [45].

Both caregiving and the home environment impact successful aging in place [19]. To that end, creating a barrier-free environment is essential, making home modifications a critical strategy to ensure universal design [46]—an idea that connects the aging-in-place facilitators cluster to the housing cluster. Evidence shows that such home modifications can lead to longer stays in one’s home, thereby supporting aging in place [13].

Technology is another important facilitator, enabling tools like telehealth [47]. As shown in Figure 1, keywords such as telehealth and telecare connect the aging-in-place facilitators and assistive technologies clusters, emphasizing the role of technology in supporting independent living and providing care [48]. Technologies can help with early illness detection [49], fall and emergency detection through sensors [50], and assistance from robots [51]. However, several factors, such as age, education level, and whether individuals live alone, can influence the acceptance of technology by older adults, as highlighted by Chimento-Diaz et al. [52].

Formal care is also essential in supporting older adults, with long-term care emerging as a key concept in the mental health cluster. Studies indicate that long-term care facilities can lead to negative outcomes, including loneliness [53], social isolation [54], and depression [55]. On the other hand, Bolton and Dacombe [4] investigated how social isolation can impact health among older adults who are aging in place. Their study emphasized that aging in place can increase the risk of social isolation, which may in turn lead to various health problems.

The keywords mental health and health promotions bridge the housing and mental health clusters. This connection is logical, as promoting aging in place—allowing elderly individuals to remain in their homes rather than transitioning to long-term care facilities—can have a positive impact on their health [56]. Studies show that elderly individuals prefer to remain in their homes [8], where they feel a sense of belonging and attachment. For example, Muszyński [57] examined various aspects of housing and found that the home environment reflects multiple dimensions of an older person’s identity, including physical, biographical, aesthetic, and axiological dimensions. The study highlighted two key aspects of place: (1) objects collected by older adults and (2) activities in which they engage in their homes.

The housing cluster connects with the assistive technologies cluster via keywords like smart homes e.g., [58]. However, they appear distantly related in Figure 1, indicating limited overlap between these research areas.

Cluster 2, titled age-friendly communities, is closest to the housing cluster since both pertain to built environments at different scales. This suggests that age-friendly environments require planning at various levels, from urban [59] to home scales [60], to create a supportive fit between individuals and their environments [39]. The place attachment theory can explain the positive effects of such environments [12,61]. Lewis and Buffel [39] explored how place attachment and the sense of belonging in neighborhoods evolve over time for individuals who are aging in place. The study found that these feelings can vary widely among people based on their personal circumstances and changes in their community.

4.1. Limitations

This study has three major limitations. First, it relies solely on the Web of Science database. While comprehensive, the Web of Science may not include all relevant studies, and our review may thus have left some out of the analysis. For example, PubMed is frequently used in medical fields, and excluding it could lead to omitting relevant studies. However, because this study encompasses 3240 records, and most high-quality literature in PubMed is also indexed in the Web of Science, it is reasonable to assume that the study provides representative coverage of the main topics.

Second, it is possible that some irrelevant studies were included among the identified publications. However, the use of co-occurrence analysis, which assesses the relevance of studies based on the co-occurrence of keywords in the same document, mitigates this problem. Because keywords unrelated to aging in place are less likely to appear with relevant keywords, co-occurrence analysis reduces the inclusion of irrelevant studies.

Third, bibliometric analysis does not reveal the direction of relationships or indicate causal connections between nodes. Therefore, it should be used as a complementary method alongside a traditional literature review [24].

4.2. Conclusions

This study provides an overview of the landscape of the literature on aging in place, identifying key research areas, influential publications, and evolving trends. The findings highlight the importance of a multidisciplinary and holistic approach to supporting aging in place that encompasses its physical, cognitive, social, and technological dimensions as well as the built environment in which aging in place occurs. By leveraging the insights enabled by this study’s scientific map, future multidisciplinary research can contribute to the development of holistic and effective strategies that allow older adults to age in place with dignity and a high quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J. and S.H.; methodology, S.J. and S.H.; formal analysis, S.J. and S.H.; data curation, S.J.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J. and S.H.; writing—review and editing, S.J. and S.H.; visualization, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication fees for this article were supported by the UNLV University Libraries Open Article Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-92-4-156504-2. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Health Estimates 2020: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marengoni, A.; Angleman, S.; Melis, R.; Mangialasche, F.; Karp, A.; Garmen, A.; Meinow, B.; Fratiglioni, L. Aging with Multimorbidity: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, E.; Dacombe, R. “Circles of Support”: Social Isolation, Targeted Assistance, and the Value of “Ageing in Place” for Older People. Qual. Ageing Older Adults 2020, 21, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlinac, M.E.; Feng, M.C. Assessment of Activities of Daily Living, Self-Care, and Independence. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016, 31, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonifas, R.P.; Simons, K.; Biel, B.; Kramer, C. Aging and Place in Long-Term Care Settings: Influences on Social Relationships. J. Aging Health 2014, 26, 1320–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapin, R.; Dobbs-Kepper, D. Aging in Place in Assisted Living: Philosophy versus Policy. Gerontologist 2001, 41, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, J.L.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R.E.S. The Meaning of “Aging in Place” to Older People. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, C. There’s No Place Like Home: Place and Care in an Ageing Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, H.M.; Cramm, J.M.; Exel, J.V.; Nieboer, A.P. The Ideal Neighbourhood for Ageing in Place as Perceived by Frail and Non-Frail Community-Dwelling Older People. Ageing Soc. 2015, 35, 1771–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, H.S.; LaPlante, M.P.; Harrington, C. Do Noninstitutional Long-Term Care Services Reduce Medicaid Spending? Health Aff. 2009, 28, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iecovich, E. Aging in Place: From Theory to Practice. Anthropol. Noteb. 2014, 20, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, E.; Cummings, L.; Sixsmith, A.; Sixsmith, J. Impacts of Home Modifications on Aging-in-Place. J. Hous. Elder. 2011, 25, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hees, S.; Horstman, K.; Jansen, M.; Ruwaard, D. Photovoicing the Neighbourhood: Understanding the Situated Meaning of Intangible Places for Ageing-in-Place. Health Place 2017, 48, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehning, A.J. City Governments and Aging in Place: Community Design, Transportation and Housing Innovation Adoption. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Shepley, M.M.; Rodiek, S.D. Aging in Place at Home Through Environmental Support of Physical Activity: An Interdisciplinary Conceptual Framework and Analysis. J. Hous. Elder. 2012, 26, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tümer, A.; Dönmez, S.; Gümüşsoy, S.; Balkaya, N.A. The Relationship among Aging in Place, Loneliness, and Life Satisfaction in the Elderly in Turkey. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2022, 58, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hoof, J.; Kort, H.S.M.; Rutten, P.G.S.; Duijnstee, M.S.H. Ageing-in-Place with the Use of Ambient Intelligence Technology: Perspectives of Older Users. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2011, 80, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, A. Aging in Place with Age-Related Cognitive Changes: The Impact of Caregiving Support and Finances. Societies 2021, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Stroulia, E.; Nikolaidis, I.; Miguel-Cruz, A.; Rios Rincon, A. Smart Homes and Home Health Monitoring Technologies for Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 91, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanleerberghe, P.; De Witte, N.; Claes, C.; Schalock, R.L.; Verté, D. The Quality of Life of Older People Aging in Place: A Literature Review. Qual. Life Res. 2017, 26, 2899–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, S.T.M.; Wouters, E.J.M.; van Hoof, J.; Luijkx, K.G.; Boeije, H.R.; Vrijhoef, H.J.M. Factors Influencing Acceptance of Technology for Aging in Place: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2014, 83, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani-Harreman, K.E.; Bours, G.J.J.W.; Zander, I.; Kempen, G.I.J.M.; van Duren, J.M.A. Definitions, Key Themes and Aspects of ‘Ageing in Place’: A Scoping Review. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 2026–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamari, H.; Golshany, N.; Naghibi Rad, P.; Behzadi, F. Neuroarchitecture Assessment: An Overview and Bibliometric Analysis. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1362–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milfont, T.L.; Amirbagheri, K.; Hermanns, E.; Merigó, J.M. Celebrating Half a Century of Environment and Behavior: A Bibliometric Review. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 469–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladinrin, O.; Gomis, K.; Jayantha, W.M.; Obi, L.; Rana, M.Q. Scientometric Analysis of Global Scientific Literature on Aging in Place. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.; Lee, S. Implications of Aging in Place in the Context of the Residential Environment: Bibliometric Analysis and Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.J.; Evans, J.; Wiles, J.L. Re-Spacing and Re-Placing Gerontology: Relationality and Affect. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 1339–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G.J.; Cutchin, M.; McCracken, K.; Phillips, D.R.; Wiles, J. Geographical Gerontology: The Constitution of a Discipline. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 65, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, S.T.M.; Luijkx, K.G.; Rijnaard, M.D.; Nieboer, M.E.; van der Voort, C.S.; Aarts, S.; van Hoof, J.; Vrijhoef, H.J.M.; Wouters, E.J.M. Older Adults’ Reasons for Using Technology While Aging in Place. Gerontology 2016, 62, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutchin, M.P. The Process of Mediated Aging-in-Place: A Theoretically and Empirically Based Model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 57, 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillcoat-Nallétamby, S.; Ogg, J. Moving beyond ‘Ageing in Place’: Older People’s Dislikes about Their Home and Neighbourhood Environments as a Motive for Wishing to Move. Ageing Soc. 2014, 34, 1771–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixsmith, A.; Sixsmith, J. Ageing in Place in the United Kingdom. Ageing Int. 2008, 32, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, L.N. Conducting Research on Home Environments: Lessons Learned and New Directions. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Means, R. Safe as Houses? Ageing in Place and Vulnerable Older People in the UK. Soc. Policy Adm. 2007, 41, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldy, D.; Grenade, L.; Lewin, G.; Karol, E.; Burton, E. Older People’s Decisions Regarding ‘Ageing in Place’: A Western Australian Case Study. Australas. J. Ageing 2011, 30, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.; Buffel, T. Aging in Place and the Places of Aging: A Longitudinal Study. J. Aging Stud. 2020, 54, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilleard, C.; Hyde, M.; Higgs, P. The Impact of Age, Place, Aging in Place, and Attachment to Place on the Well-Being of the Over 50s in England. Res. Aging 2007, 29, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, C.; Bietz, M.; Vidauri, M.; Chen, Y. Senior Care for Aging in Place: Balancing Assistance and Independence. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, New York, NY, USA, 25 February 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1605–1617. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, S.; Newell, K.M. Aging, Neuromuscular Decline, and the Change in Physiological and Behavioral Complexity of Upper-Limb Movement Dynamics. J. Aging Res. 2012, 2012, 891218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deary, I.J.; Corley, J.; Gow, A.J.; Harris, S.E.; Houlihan, L.M.; Marioni, R.E.; Penke, L.; Rafnsson, S.B.; Starr, J.M. Age-Associated Cognitive Decline. Br. Med. Bull. 2009, 92, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreugdenhil, A. “Ageing-in-Place”: Frontline Experiences of Intergenerational Family Carers of People with Dementia. Health Sociol. Rev. 2014, 23, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelker, L.S.; Bass, D.M. Home Care for Elderly Persons: Linkages Between Formal and Informal Caregivers. J. Gerontol. 1989, 44, S63–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, K.; Weir, P.L.; Azar, D.; Azar, N.R. Universal Design: A Step toward Successful Aging. J. Aging Res. 2013, 2013, 324624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanRavenstein, K.; Davis, B.H. When More Than Exercise Is Needed to Increase Chances of Aging in Place: Qualitative Analysis of a Telehealth Physical Activity Program to Improve Mobility in Low-Income Older Adults. JMIR Aging 2018, 1, e11955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowes, A.; McColgan, G. Telecare for Older People: Promoting Independence, Participation, and Identity. Res. Aging 2013, 35, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Bian, H.; Chang, C.K.; Dong, L.; Margrett, J. In-Home Monitoring Technology for Aging in Place: Scoping Review. Interact. J. Med. Res. 2022, 11, e39005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantz, M.J.; Skubic, M.; Miller, S.J.; Galambos, C.; Alexander, G.; Keller, J.; Popescu, M. Sensor Technology to Support Aging in Place. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mois, G.; Beer, J.M. Chapter 3—Robotics to Support Aging in Place. In Living with Robots; Pak, R., de Visser, E.J., Rovira, E., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 49–74. ISBN 978-0-12-815367-3. [Google Scholar]

- Chimento-Diaz, S.; Sanchez-Garcia, P.; Franco-Antonio, C.; Santano-Mogena, E.; Espino-Tato, I.; Cordovilla-Guardia, S. Factors Associated with the Acceptance of New Technologies for Ageing in Place by People over 64 Years of Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimelow, R.E.; Wollin, J.A. Loneliness in Old Age: Interventions to Curb Loneliness in Long-Term Care Facilities. Act. Adapt. Aging 2017, 41, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, S.A.; Weldrick, R.; Lee, T.-S.J.; Taylor, N. Social Isolation Among Older Adults in Long-Term Care: A Scoping Review. J. Aging Health 2021, 33, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Blazer, D.G. Depression in Long-Term Care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2008, 9, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, K.D.; Rantz, M.J. Aging in Place: A New Model for Long-Term Care. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2000, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muszyński, M. The Image of Old Age Emerging from Place Personalization in Older Adults’ Dwellings. J. Aging Stud. 2022, 63, 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tural, E.; Lu, D.; Austin Cole, D. Safely and Actively Aging in Place: Older Adults’ Attitudes and Intentions Toward Smart Home Technologies. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 23337214211017340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, P.; Gallagher, N.A. Optimizing Mobility in Later Life: The Role of the Urban Built Environment for Older Adults Aging in Place. J. Urban Health 2013, 90, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, C.C.; Yearns, M.H.; Martin, P. Aging in Place: Home Modifications Among Rural and Urban Elderly. Hous. Soc. 2005, 32, 85–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrusán, I.; Gómez, M.V. The Importance of Place Attachment in the Understanding of Ageing in Place: “The Stones Know Me”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).