Abstract

Retirement marks a pivotal transition not only for individuals but also for their families. Existing research has examined relational aspects of retirement but primarily focuses on how family members influence the retiree’s well-being rather than on the impact of this transition on other family members and the broader family system. To address this imbalance, the present review synthesizes evidence drawing upon Family Life Course Theory and Family Systems Theory. Using a well-established five-stage framework, we conducted extensive database searches and refined our guiding research question. Of the 4034 studies identified, 61 were selected for detailed analysis. Data extraction and thematic coding, supported by MAXQDA 24 software, revealed eight interconnected themes: marital quality and conflict; dyadic adjustments between partners; financial impacts and concerns; time use and leisure; redistribution of domestic roles; health outcomes; emotional and psychological effects on the family unit; and intergenerational dynamics. Across these domains, gender consistently emerged as a central, asymmetrical determinant of adaptation. Ultimately, this review demonstrates that retirement constitutes a relational turning point within families and calls for future research to adopt inclusive, longitudinal designs, and for practitioners and policymakers to develop family-centred interventions that recognize the systemic impact of retirement.

1. Introduction

Retirement has traditionally been conceptualized as a discrete event marking the end of paid employment. Increasingly, however, it is understood as a complex and layered life-course transition with implications for both individuals and their families. Research indicates that retirement’s impact on personal well-being is varied, underscoring the importance of examining this transition within its broader life-course and social contexts and also considering couples’ conjoint experiences (Mitchell et al., 2021; Tunney et al., 2024; Wickrama et al., 2013). In the context of an aging global population and evolving work patterns, it is crucial to examine the broader societal and relational consequences of retirement. Despite this, dominant perspectives continue to frame retirement primarily through financial and health-related lenses. Systematic reviews by Ingale and Paluri (2023) and Nazar et al. (2025), for example, highlight how scholarly and policy discussions often prioritize financial planning and physical health outcomes, yet disregard relational dimensions that may be at the root of family maladaptation. Recognizing these limitations invites a broader conceptualization of retirement—one that accounts for its ripple effects across family systems, reshaping roles, relationships, and collective well-being.

Theoretical frameworks such as Family Life Course Theory and Family Systems Theory underscore this inherent interconnectedness and provide analytical tools. Family Systems Theory posits that the family operates as an interconnected unit (Papero, 1990) where changes, such as the retirement of one member, inevitably reverberate through the entire system, influencing communication patterns, role distribution, and overall well-being (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983; Olson, 2000; Priest, 2021). Similarly, Life Course Theory emphasizes how cumulative work and family experiences throughout an individual’s lifespan shape their retirement trajectory and the subsequent impact of retirement on family dynamics (Elder & Giele, 2009; Han & Moen, 1999). Together, these theories guide our understanding of retirement as a process embedded within broader family systems in which members are interdependent and collectively adjust to significant life changes. They provide a crucial lens for examining how the accumulation of work and family experiences across the adult lifespan can lead to divergent outcomes in retirement, not only for the individual, but for the family as a whole.

Despite growing recognition of retirement as a relational transition that affects the emotional, practical, and structural aspects of family life, existing research often presents as a fragmented collection of studies, primarily centring on individual-level outcomes or dyadic relationships with limited theoretical integration. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of retirement’s impact on the broader family unit remains elusive, underscoring the absence of a systematic synthesis that integrates work-family life with family-level dynamics.

Prior syntheses, such as those by Fisher et al. (2016) and Teques et al. (2025), have made valuable contributions to the understanding of retirement. Fisher et al. (2016) provide a comprehensive overview of retirement timing, its antecedents, and consequences. While their model includes familial factors, its overarching framework, and detailed discussions predominantly centre on individual-level determinants like health, economic status, and psychological factors of the retiree. Relational dynamics, such as marital factors and family caregiving, are discussed in relation to their impact on the individual’s retirement timing or satisfaction, rather than as interdependent processes within the family unit. Similarly, Teques et al. (2025) advance the literature through a systematic review and meta-analysis of well-being in retirement across Europe, yet their analysis privileges personal well-being indicators and largely omits the interdependent processes within couples and families. Even when family relations and grandparenting are included among their themes, the focus remains on how these aspects influence the individual retiree’s well-being, such as the impact of widowhood on an individual’s mental health or grandchild care on a grandparent’s health. These earlier reviews, while acknowledging relational aspects, tend to re-centre the individual, treating family dynamics as peripheral to the retiree’s experience.

A more comprehensive approach would foreground the couple or family as the unit of analysis, focusing on how one person’s retirement shapes the experiences, roles, and well-being of other family members. This perspective acknowledges the dynamic nature of later-life partnerships, where retirement may coincide with or influence periods of both stability and instability, including marital dissolution. It also broadens the conceptualization of family beyond the traditional marital dyad to encompass the diverse configurations that characterize contemporary later-life families. Rather than centring solely on the retiree’s adjustment, this approach considers how accumulated work-family life courses, occupational characteristics, and intra-family dynamics (e.g., marital quality, conflict, solidarity) reconfigure patterns of interaction, communication, and relationship quality across the family system. In doing so, it moves beyond dominant individual-level paradigms to offer a relational and systemic understanding of retirement as a transition that reverberates throughout the family unit. Grounded in a scoping review methodology, our approach also incorporates theory-informed interpretation to make sense of patterns that are otherwise fragmented across the literature.

This scoping review addresses this critical gap by systematically exploring research on retirement transitions and their effects on family dynamics and relationships. Specifically, our review asks: How do individual retirement transitions affect family well-being, considering the interplay of work–life experiences, family structures, and relationship dynamics? This question is grounded in Family Life Course Theory, which highlights the long-term accumulation of experiences (Elder & Giele, 2009), and Family Systems Theory, which emphasizes the interactive nature of family life (Papero, 1990). These theoretical perspectives also highlight the profound influence of family life-course factors, such as the presence and geographical proximity of parents, children, and grandchildren, on significant life events like retirement (Svensson et al., 2015). Furthermore, they underscore how early investments in work and caregiving roles, conceptualized as a “family organizational economy” (Henretta et al., 1993), can shape later-life transitions and their broader family implications, often mediated by micro-relational dynamics operating within families and macro-institutional conditions arising from social and policy structures. Ultimately, this approach enables an integrated examination of how these elements collectively shape the family’s adaptation to retirement.

To clarify our central argument, we examined three secondary questions: (1) How does the nature of the individual’s occupation prior to retirement shape the family’s retirement experience and subsequent well-being?; (2) How do family circumstances and relationships prior to retirement shape the family’s retirement experience and subsequent well-being?; and (3) How does the retirement transition affect family dynamics, such as marital quality, conflict, and solidarity? This review frames retirement as a shared family process, distills core themes and frameworks, and draws out implications for advancing research, practice, and policy.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review maps how retirement transitions affect family dynamics and relationships. Scoping reviews help explore complex, interdisciplinary topics by identifying patterns, frameworks, and gaps in the literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Aromataris & Munn, 2020; Levac et al., 2010). Synthesizing findings across diverse disciplines can advance our understanding of retirement’s relational dimensions and provide direction for future research and resource development. The review was conducted using Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) five-stage framework and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist (Tricco, 2018) (Table S1). The registered protocol is accessible through the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/g82kj/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

During piloting, the primary research question was refined to sharpen the review’s focus. The original question—How do work-family life courses and family-level dynamics shape the relationship between an individual’s retirement transition and the well-being of the family unit?—was revised to: How do individual retirement transitions affect family well-being, considering the interplay of work–life experiences, family structures, and relationship dynamics? This refinement, made before full-text screening, clarified the relationships and mechanisms under investigation and did not change the inclusion criteria or methodological boundaries.

2.1. Search Strategy

Search strategies were developed in collaboration with a health sciences librarian to ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant disciplines and terminology. In February 2025, searches were conducted across six databases: Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, PsycINFO, SocINDEX, and MEDLINE. Boolean operators and keyword variations were used to capture concepts related to retirement, family relationships, and transitional processes. The search strings included terms related to retirement, family well-being, work-family dynamics, and occupational characteristics. To validate the search strategy, a benchmark set of ten articles, identified through preliminary searching and known to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria, was used to test the final query strings. The search query was adjusted if any benchmark articles were missing from the results. Hand searching of reference lists identified additional records beyond the original search, which were screened using the same process as database results.

2.2. Screening Process

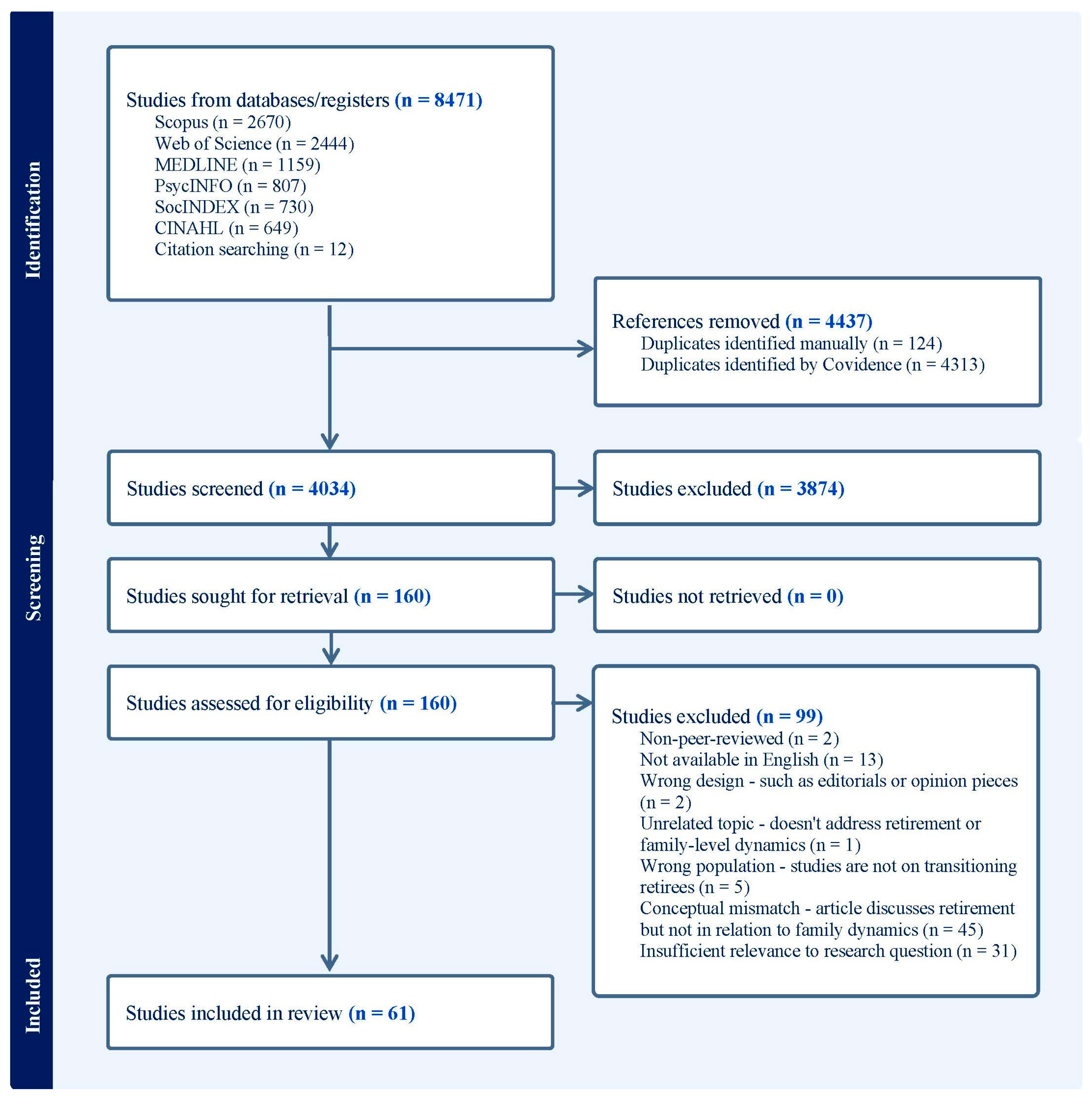

Search results were imported into Covidence (https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 12 December 2025)), where duplicates were automatically removed. Because Covidence can miss duplicates due to bibliographic variations, the team manually deduplicated to remove those missed. Title and abstract screening were conducted independently by two reviewers, with conflicts resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. Eligibility criteria were piloted and refined before screening to ensure consistent application. Weekly team meetings supported consensus-building and procedural transparency. Full-text screening was conducted using the same procedure as title and abstract screening. Reasons for exclusion were documented and presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). All full texts were accessed through the university library system, and no author contact was required. These procedures were designed to ensure a transparent and rigorous screening process that minimizes selection bias.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they examined the relationship between retirement and family well-being; explored how work-family life courses or family-level dynamics shaped retirement experiences; investigated links between pre-retirement occupation and family outcomes; or analyzed the impact of retirement transitions on family relationships. While much of the literature focused on later-life retirement, our eligibility criteria did not include age restrictions to allow for the inclusion of studies on younger retirees, such as athletes. No date restrictions were applied. Studies were excluded if they focused solely on individual-level outcomes without family context; did not examine work-family trajectories or occupational factors; were not published in English or available in full-text; were not peer-reviewed (e.g., unpublished dissertations, conference abstracts, or other forms of grey literature); or lacked empirical data or evidence-based insights, such as opinion-based articles.

2.4. Data Extraction

To ensure consistency and relevance, the research team conducted a calibration exercise using sample articles to refine the data extraction framework. This process involved identifying qualitative data fragments, study characteristics, metadata, and theoretical frameworks relevant to retirement transitions and family dynamics. Reliability was assessed by having team members independently extract data from a subset of included studies, followed by collaborative comparison and consensus-building. Each included study was then assigned to a team member for final extraction. Extracted data included descriptions, narratives, and accounts of the retirement transition’s impact on family relationships; study characteristics such as research design, sample size, participant demographics, and data collection methods; metadata including title, author(s), journal, country of origin, study population, and year of publication; and theoretical frameworks such as Life Course Theory, Family Systems Theory, or other models relevant to work-family dynamics and relational health.

All extracted data were compiled into a centralized dataset and reviewed by the lead researcher for completeness and accuracy. Team members consulted the lead as needed to resolve uncertainties and maintain data quality throughout the process. To facilitate the thematic synthesis of qualitative findings, MAXQDA software was used to organize and code extracted data. This tool enabled systematic categorization of recurring concepts and themes across studies. Coding was conducted primarily inductively, allowing themes to emerge from the data while remaining attentive to the review’s guiding questions. The software’s features—such as code mapping, memoing, and retrieval functions—supported iterative refinement of themes and ensured transparency in the analytic process. Coding was performed by six reviewers, with regular meetings held to discuss discrepancies and maintain consistency.

2.5. Data Management and Sharing

The list of all included articles, together with their key themes and findings, is provided in Appendix A. Full references for all included articles are available in the reference list. The registered protocol is accessible through the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/g82kj/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

3. Results

This scoping review synthesized findings from the included literature in relation to the review’s guiding questions. The analysis highlights how retirement transitions affect family well-being, shaped by pre-retirement family circumstances and relationship dynamics such as marital quality, conflict, and solidarity. Occupational histories were also considered, though the specific nature of individuals’ work prior to retirement was less frequently emphasized in the literature.

After removing duplicates, 4034 studies underwent title and abstract screening. Of these, 160 were selected for full-text review, and 61 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1). Among the included studies, 15 were published before 2000, 18 between 2000 and 2014, and 28 in the last decade (2015–2025). The largest proportion originated from the United States (n = 26), whereas all other countries contributed substantially fewer, typically between one and four studies each. A full breakdown of countries of origin is available in Appendix A. In terms of research design, 41 studies were quantitative, 15 qualitative, three mixed methods, and two were literature reviews. A more granular analysis of these designs revealed that all 15 qualitative studies and all three mixed methods studies employed a cross-sectional approach. Among the quantitative studies, 12 were cross-sectional, while 29 were longitudinal. This means that, excluding the two literature reviews, our synthesis draws upon 29 longitudinal studies and 30 cross-sectional studies. Appendix A summarizes the included literature in a table with the author, publication year, country of origin, research design, primary themes, and key findings.

The synthesis of the included literature allowed us to map eight overarching and interconnected themes that directly address the review’s guiding questions. These themes, which include marital quality and conflict, dyadic adjustments between partners, financial impacts and concerns, time use and leisure, redistribution of domestic roles, health outcomes, emotional and psychological effects on the family unit, and intergenerational dynamics, often intersect. Beyond simply identifying these domains, our analysis also revealed emergent insights into how gendered experiences, financial implications, and health outcomes influence multiple domains, thereby contributing to varied patterns of family adaptation. Each theme is explored in the sections that follow, illustrating the complex nature of retirement as a shared family process.

3.1. Marital Quality (Satisfaction, Conflict)

Retirement significantly impacts marital relationships, presenting both opportunities for enhanced connection and potential sources of strain. Several studies suggest that the quality of the relationship prior to retirement can strongly shape post-retirement outcomes: couples with strong relationships are more likely to report positive adjustments, whereas those with pre-existing conflict may face greater challenges, particularly when compounded by financial pressures or shifts in domestic roles (Davey & Szinovacz, 2004; Fitzpatrick & Vinick, 2003; Moen et al., 2001; Myers & Booth, 1996; Szinovacz & Davey, 2004; van Solinge & Henkens, 2005; Vinick & Ekerdt, 1991), though findings are not uniform across all studies.

While several studies indicate a positive association between concurrent spousal retirement and higher marital satisfaction (Davey & Szinovacz, 2004; Kridahl & Duvander, 2024; Moen et al., 2001; Szinovacz & Davey, 2004; Weber & Hülür, 2021), a comprehensive understanding of this relationship remains elusive due to historical research biases that emphasize individual (primarily male) retirement, methodological limitations in capturing dynamic couple interactions, and mediating factors. From a life course perspective, the positive association aligns with the expectation that synchronizing major role transitions situates partners within the same life stage, thereby supporting shared routines and, in turn, greater marital contentment. Gendered patterns are also evident, as men’s satisfaction is often linked to their wives’ retirement status (Chen, 2022; Davey & Szinovacz, 2004; Haug et al., 1992; Moen et al., 2001; D. B. Smith & Moen, 2004; Szinovacz & Davey, 2004), while wives’ satisfaction is more closely tied to overall relational quality (Keating & Cole, 1980; Kulik, 2001; Pina & Bengtson, 1993; Vinick & Ekerdt, 1991), although the dynamics underlying these associations are nuanced. For wives, voluntary retirement is associated with positive outcomes (Hill & Dorfman, 1982; Moen et al., 2001), whereas continuing to work after a husband’s retirement is linked to diminished satisfaction (Cooley & Adorno, 2016; Lee & Shehan, 1989; Moen et al., 2001).

Marital conflict and strain can stem from disagreements over household chores, financial management, and time allocation (Cooley & Adorno, 2016; Davey & Szinovacz, 2004; Heyman, 1970; Myers & Booth, 1996; Szinovacz & Schaffer, 2000). Wives frequently report higher levels of strain, particularly if they remain employed after their husbands retire (Cooley & Adorno, 2016; Ekerdt & Vinick, 1991; Lee & Shehan, 1989; Moen et al., 2001; Myers & Booth, 1996; Szinovacz & Schaffer, 2000). Szinovacz and Schaffer (2000) also found that when wives scale back their paid work hours, marital arguments become less frequent. Beyond the sources of strain and conflict, couples also differ in how they communicate during this transition, with some couples experiencing greater emotional connection and openness, while others report diminished authenticity (Brown et al., 2019; Horn et al., 2021; Keating & Cole, 1980; Pedreiro et al., 2023; Szinovacz & Schaffer, 2000). Despite these challenges, retirement can foster greater marital solidarity and spousal support through increased shared time, emotional backing, and a more equitable division of labour—factors linked to higher marital satisfaction (Barnes & Parry, 2004; Cohn-Schwartz et al., 2021; D’Cruz, 2005; Dressler, 1973; Szinovacz, 1980).

3.2. Dyadic Adjustments

Dyadic adjustment, which focuses on mutual adaptation within couples, is a critical and often challenging aspect of retirement. Retirement adaptation should be analyzed dyadically, as one partner’s retirement invariably affects the well-being of the other, often leading to shifts in the balance of power, renegotiation of roles and responsibilities, and potential for both increased connection and new sources of tension within the couple (Curl & Townsend, 2013; D’Cruz, 2005; Damman et al., 2019; Haug et al., 1992; Moen et al., 2001; Müller & Shaikh, 2018; Nashef-Hamuda et al., 2025; Szinovacz, 2000; Szinovacz & Schaffer, 2000; Weber & Hülür, 2021). Indeed, various factors can significantly influence the ease or difficulty of this mutual adaptation, as exemplified by how forced (involuntary) retirement has been identified as a strong predictor of adjustment problems for both individuals and the couple, making negative outcomes more likely (van Solinge & Henkens, 2005).

Retirement can alter the balance of power within marriages, often prompting a renegotiation of roles and responsibilities. If husbands become more reliant on their spouses, for reasons that vary across studies, women’s influence and authority within the relationship may increase (Caltabiano et al., 2016; Chen, 2022; Haug et al., 1992; Szinovacz, 2000; Szinovacz & Schaffer, 2000). However, these shifts can also introduce new sources of tension and conflict (Cliff, 1993; Cooley & Adorno, 2016; Fitzpatrick & Vinick, 2003; Keating & Cole, 1980; Kulik, 2001; Szinovacz & Davey, 2004; Szinovacz & Schaffer, 2000), especially if traditional gendered divisions of labour persist (see Section 3.5). The timing of retirement is pivotal in shaping household dynamics; when one partner retires earlier, their bargaining power may decline, particularly if the other continues to earn income and thus maintains greater perceived resources (Austen et al., 2022; Kridahl & Duvander, 2024; Xiong et al., 2024).

Role realignment is another key dimension of this transition. Although men may increase their participation in domestic tasks post-retirement, entrenched gendered divisions of labour often persist, which can lead to marital strain and perceptions of disruptive change (Alvarez et al., 2007; Fengler, 1975; Kulik, 2001; Lee & Shehan, 1989; Moen et al., 2001; Myers & Booth, 1996; Szinovacz, 2000; Szinovacz & Schaffer, 2000). The consequences for marital quality are mixed: while some studies report similar outcomes for both men and women (Kulik, 2001; Moen et al., 2001; D. B. Smith & Moen, 2004), others highlight notable gender-based differences in adjustment experiences (Foley et al., 2023; Haug et al., 1992; Hwang et al., 2025; Kulik, 2001). Ultimately, successful dyadic adjustment depends on the couple’s capacity to collaboratively redefine their roles, expectations, and daily routines in response to the evolving demands (Agnew et al., 2025; Barnes & Parry, 2004; Cliff, 1993; Cooley & Adorno, 2016; Pedreiro et al., 2023; D. B. Smith & Moen, 2004).

3.3. Financial Impacts and Concerns

Although financial stability, often shaped by employment history, is consistently linked to retirement satisfaction and family well-being, the reviewed studies offer limited evidence on how the broader nature of pre-retirement occupations directly influences family experiences. Financial security, a condition often rooted in stable employment, makes retirement satisfaction and family well-being more likely, whereas income decline and financial strain have adverse effects (Austen et al., 2022; Cliff, 1993; Damman et al., 2019; Fitzpatrick & Vinick, 2003). Retirement can introduce disruptions, reductions, or a shift to fixed income, creating financial pressures that negatively affect retirees and their families (Agnew et al., 2025; Brown et al., 2019; Giffen & McNeil, 1967; Hill & Dorfman, 1982; Mergenthaler & Cihlar, 2018; Myers & Booth, 1996; Rawat & Rawat, 2006; D. B. Smith & Moen, 2004; Xiong et al., 2024).

These financial shifts frequently have gendered implications, such as men’s loss of the traditional provider role, which can increase family conflict, especially if the wife remains employed (Cliff, 1993; Moen et al., 2001; Myers & Booth, 1996; Szinovacz & Schaffer, 2000). Some studies reported that men’s retirement can be accompanied by a substantial decrease in family income, potentially lowering couples’ standard of living, although these findings are based on early research and on work conducted in specific cultural contexts (Fitzpatrick & Vinick, 2003; Myers & Booth, 1996; Xiong et al., 2024). Financial conditions also shape well-being in gender-specific ways, with some studies distinguishing between husbands and wives and others reporting financial consequences at the couple level when either spouse retires, reflecting anxieties about financial stability or dependence (Austen et al., 2022; Hill & Dorfman, 1982; Myers & Booth, 1996; Newmyer et al., 2023; Xiong et al., 2024). Pre-retirement financial planning and education are shown to ease financial concerns and support couples’ adjustment to retirement, but findings are mixed on whether they consistently reduce stress or avert financial tensions (Cooley & Adorno, 2016; Damman et al., 2019; Hill & Dorfman, 1982).

3.4. Time Use (Shared Time, Impingement, Leisure)

Changes in time use are a prominent theme affecting family dynamics, encompassing shifts in daily routines, work–life balance, leisure, and social participation. Retirement can bring increased freedom and opportunities for joint activities, slowing and relaxing daily routines, which can foster greater connection but may also necessitate adjustments to individual pursuits. Early research suggested that husbands often experience a surplus of free time and reduced activity (Dressler, 1973; Fengler, 1975; Heyman, 1970; Hill & Dorfman, 1982; Vinick & Ekerdt, 1991). Subsequent findings show that a husband’s retirement can shift his wife’s activity patterns, though not in a consistently leisure-enhancing direction, whereas a wife’s retirement is more clearly associated with increases in her husband’s leisure, voluntary work, and social engagement (Atalay & Zhu, 2018; Fitzpatrick & Vinick, 2003).

These shifts also intersect with how couples negotiate shared space and routines. Despite the benefits of increased togetherness, greater shared time sometimes leads to impingement or underfoot dynamics. This occurs when one retired spouse is perceived by the other, typically the non-retired partner, as intruding on established routines, personal space, or daily activities, thereby introducing marital strain. The problem is often exacerbated when retirees lack personal activities or encounter later-stage retirement transitions, in which the novelty of leisure gives way to challenges sustaining engagement and managing household tensions, with complaints including reduced activity, lack of privacy, too much togetherness, and strain over domestic responsibilities. Although it is conceivable that retired wives could encroach upon their husbands’ activities, the studies reviewed consistently show that husbands impinge on their wives’ activities and personal space, though the extent and significance of this intrusion vary, with some studies identifying it as a substantial source of strain and others noting it only as a minor irritant (Bushfield et al., 2008; Cliff, 1993; Cooley & Adorno, 2016; Ekerdt & Vinick, 1991; Fengler, 1975; Foley et al., 2023; Heyman, 1970; Hill & Dorfman, 1982; Keating & Cole, 1980; Kulik, 2001; Loureiro et al., 2016; Myers & Booth, 1996; Szinovacz & Schaffer, 2000; Vinick & Ekerdt, 1991).

Studies note that couples spend more time together after retirement, but the implications for broader social engagement vary, with some research reporting reduced involvement in external networks (Dressler, 1973) and other studies showing that retirees maintain or even expand their social activities, often through more joint interactions with family and friends (Cliff, 1993; Cohn-Schwartz et al., 2021; Fengler, 1975). These shifts matter because they reshape couples’ support systems and shared social identity, with many couples simultaneously establishing new routines around common interests (Horn et al., 2021; Lally & Kerr, 2008). Research indicates that husbands’ retirement does not generally increase wives’ social participation, with studies showing that wives’ individual pursuits tend to decrease or remain stable (Fitzpatrick & Vinick, 2003; Fitzpatrick et al., 2005; D. B. Smith & Moen, 2004). One study reports that wives may expand shared activities by integrating their husbands into their own social circles, though some wives report frustration at having to incorporate their husbands into activities they previously pursued independently (Heyman, 1970). Husbands often benefit from their wives’ emotional and social support in retirement, and some men describe turning to their wives to avoid feeling alone (Barnes & Parry, 2004; Keating & Cole, 1980; Loureiro et al., 2015). Such reliance can place new demands on wives as they respond to their husbands’ increased need for companionship and connection. In contrast, a notably different pattern emerges when wives retire. Husbands who tend to expand their own social participation, through volunteer and leisure activities, are more likely to retire themselves, which positively impacts their mental health (Atalay & Zhu, 2018). This stands in marked contrast to the ways women’s retirement often draws them further into meeting their husbands’ relational needs rather than opening space for their own needs.

3.5. Redistribution of Roles & Domestic Responsibilities

Family circumstances and pre-retirement relationships significantly shape retirement experiences, often necessitating a renegotiation of roles and identities within the family unit. Retirement naturally brings changes in spouses’ responsibilities and shifts in both individual and couple identities, and the ways partners understand and renegotiate gender roles can shape their marital dynamics in this stage of life. These renegotiations often shift more labour onto the retiree, though the effects vary across households. In more traditional arrangements, men may be prompted to take on a greater share of domestic roles (Bonsang & van Soest, 2020; Caltabiano et al., 2016; Cliff, 1993; Heyman, 1970; Kulik, 2001), though entrenched gendered roles often persist. Research shows that wives frequently remain responsible for a disproportionate share of domestic work in retirement, revealing persistent gendered inequalities and, as some authors note, constraints on women’s personal autonomy (Cooley & Adorno, 2016; Foley et al., 2023; Heyman, 1970; Hwang et al., 2025; Xiong et al., 2024). While there is evidence that wives’ retirement leads to little or no change in household task allocation (Szinovacz, 1980), Bonsang and van Soest (2020) found that women substantially increase their home production after retirement, by approximately 7–11 h per week. Earlier studies noted that husbands sometimes justify the persistence of established divisions by claiming that wives preferred to maintain their roles, or felt that husbands were intrusive when attempting to take on additional tasks (Ekerdt & Vinick, 1991; Keating & Cole, 1980; Szinovacz, 1980).

Such gendered patterns are linked to lower marital satisfaction among couples adhering to traditional divisions of labour (Myers & Booth, 1996), though some evidence suggests men with traditional beliefs may report improved satisfaction following wives’ retirement from paid employment (Szinovacz & Schaffer, 2000). By contrast, in families with more egalitarian gender roles, retirement transitions are often more successful when male retirees increase involvement in household tasks (Szinovacz, 2000). Marital satisfaction tends to be higher when spouses foster a more equal redistribution of roles, particularly when wives are employed full-time and hold egalitarian beliefs (Pina & Bengtson, 1993). Wives of retired husbands may desire greater involvement from their partners, and research highlights that shared activities and more equitable household contributions support their well-being (Cooley & Adorno, 2016; Fitzpatrick & Vinick, 2003; Hill & Dorfman, 1982).

Beyond the marital dyad, retirement can also reshape identities within intergenerational relationships. For example, retiring early and becoming more available may increase the likelihood that adult children have children, positioning some women as active grandparents and influencing broader family dynamics (Bolano & Bernardi, 2024). These identity shifts are closely tied to changes in caregiving responsibilities, which extend across multiple generations and family members. Retirement often enables grandparents, particularly women, to provide childcare for grandchildren, strengthening intergenerational ties (Bolano & Bernardi, 2024; Loureiro et al., 2016). Retired parents may also support adult children in other ways, and for those with adult children with disabilities, retirement can affect their ongoing capacity to provide care (Dow & Meyer, 2010). Spousal caregiving becomes more salient in later life, with wives disproportionately assuming care for ill partners, a shift that can disrupt household balance and influence retirement timing and planning (Caltabiano et al., 2016; Dow & Meyer, 2010; Foley et al., 2023; Haug et al., 1992). Retirees may also find themselves supporting their own aging parents (Dow & Meyer, 2010). In grandchild care, husbands may increase their involvement when both partners retire (Bonsang & van Soest, 2020), although women remain the primary caregivers, a pattern associated with lower bargaining power and interrupted employment histories (Barnes & Parry, 2004; Caltabiano et al., 2016; Mergenthaler & Cihlar, 2018; Xiong et al., 2024). These caregiving patterns ultimately reinforce a gendered distribution of unpaid work, leaving women with heavier responsibilities while men retain more opportunities for leisure or continued employment.

3.6. Health Outcomes

Retirement has complex spillover effects on the physical and mental health of both spouses, producing mixed outcomes and shifts in lifestyle behaviours. The impact on physical health varies, with some retirees reporting improvements when both partners retire, while others show declines (Müller & Shaikh, 2018). Contrary to a hypothesis of adverse spillover, Curl and Townsend (2013) identify a positive association between one spouse’s retirement and the other’s self-rated health. Retirement also prompts lifestyle changes: increased physical activity and leisure time are common (D’Cruz, 2005), though some individuals experience negative shifts such as increased smoking or drinking (Müller & Shaikh, 2018), highlighting how behavioural adjustments can amplify or mitigate health spillovers between spouses.

Mental health outcomes are similarly mixed. While retirement can reduce depressive symptoms for some couples, others experience heightened depression linked to financial stress or impingement. A husband’s retirement may lessen depressive tendencies in wives (Zang, 2020), but other studies suggest it can worsen these tendencies due to reduced income and constrained autonomy (Bertoni & Brunello, 2017). In contrast, wives’ retirement has been found to positively influence husbands’ mental health, particularly by reducing depressive symptoms (Atalay & Zhu, 2018). The cross-spouse effects highlight the interdependence of partners’ emotional states, demonstrating emotional contagion—the process through which one person’s emotions and behaviours elicit similar responses in others (Mazzuca et al., 2019)—while individual differences in coping and emotion-regulation capacities can buffer the mental health impact of stressors (Giffen & McNeil, 1967; Horn et al., 2021).

Overall, these findings reflect the broader role of underlying health in shaping couples’ retirement experiences. Poor health can precipitate earlier retirement and heighten strain within the partnership, whereas better health generally supports smoother adjustment and higher satisfaction (Fitzpatrick & Vinick, 2003; Haug et al., 1992; Myers & Booth, 1996; Newmyer et al., 2023). Still, some studies report minimal spillover from the retiree’s health to the partner’s adaptation (Damman et al., 2019; D. B. Smith & Moen, 2004), underscoring the heterogeneity of health-related retirement dynamics.

3.7. Emotional and Psychological Effects on the Family Unit

Retirement can have a wide range of emotional and psychological effects on the family unit, influencing well-being, adjustment, and identity. These effects arise through the everyday emotional exchanges and shifting roles that shape family life. The transition often requires families to renegotiate roles and provide mutual support, and can involve turbulence when expectations are unclear or coping resources are limited (Brown et al., 2019; Cliff, 1993; Keating & Cole, 1980; Loureiro et al., 2016; Nashef-Hamuda et al., 2025; S. D. Smith, 1997). The research highlights that couples can face challenges in managing emotions and maintaining harmony during the transition to retirement, with some experiencing greater connection and others conflict or feelings of intrusion (Brown et al., 2019; Horn et al., 2021; Pedreiro et al., 2023; Vinick & Ekerdt, 1991). Effective emotion regulation and dyadic coping—where both partners actively manage stress together (Falconier & Kuhn, 2019)—can buffer stress and support positive adjustment (Horn et al., 2021), highlighting the coordinated efforts couples use to manage emotional demands.

Emotional well-being may improve through greater structure, stability, and shared time post-retirement, with many families reporting increased satisfaction (Cohn-Schwartz et al., 2021; D’Cruz, 2005; Fengler, 1975; Rawat & Rawat, 2006; Szinovacz, 1980; Vinick & Ekerdt, 1991). However, excessive togetherness can reduce satisfaction, leading to feelings of spousal intrusion (Bozoglan, 2015; Bushfield et al., 2008; Keating & Cole, 1980; Kulik, 2001; Szinovacz, 1980). The emotional toll on families can be substantial when a retiree faces mental health challenges, as reported in professions like firefighters (Alvarez et al., 2007), athletes (Agnew et al., 2025; Brown et al., 2019; Lally & Kerr, 2008), and the military (Giffen & McNeil, 1967; Rawat & Rawat, 2006). Retirement satisfaction often reflects couples’ emotional dynamics, and research on husbands’ retirement shows positive effects frequently emerge when husbands leave the workforce (Austen et al., 2022; Barnes & Parry, 2004; Keating & Cole, 1980; Rawat & Rawat, 2006). Broader conclusions about gendered patterns, however, will require studies that examine wives’ retirement in relation to this dynamic.

Adjustment extends beyond couples to the broader later-life family unit, with families providing crucial social support during the transition (Alvarez et al., 2007; Brown et al., 2019; Giffen & McNeil, 1967; S. D. Smith, 1997). Emotional responses vary widely, ranging from improved harmony (Horn et al., 2021; Pedreiro et al., 2023; Weber & Hülür, 2021), to heightened strain (Hwang et al., 2025; Moen et al., 2001; Nashef-Hamuda et al., 2025). In families of retired athletes, adjustment is complicated by identity loss and feelings of guilt among parents and partners (Agnew et al., 2025; Brown et al., 2019; Lally & Kerr, 2008). Similar emotional challenges are observed in later-life retirees, where external activities such as participation in Men’s Sheds can provide respite and renewal, reducing guilt and easing relational tensions (Foley et al., 2023). Overall, emotional adjustment is closely tied to both the nature of retirement itself and the relational context in which it unfolds.

3.8. Intergenerational Impacts and Family Structure

Retirement has wide-ranging intergenerational effects, shaping the quality of relationships between parents and adult children and influencing family dynamics beyond direct caregiving. Changes in work status often reverberate across multiple domains of family life, altering expectations, responsibilities, and patterns of interaction (Agnew et al., 2025; D’Cruz, 2005; Yang et al., 2024). Research on younger retirees, such as elite athletes transitioning out of professional sport, further illustrates how retirement can introduce distinctive relational shifts. In these families, parents often remain emotionally invested in their child’s pursuits even after the athletic career ends, highlighting the strength of intergenerational bonds (Agnew et al., 2025; Brown et al., 2019; Lally & Kerr, 2008). Early retirement in such contexts can also affect family solidarity and children’s educational opportunities, particularly when the loss of income or resources occurs before key developmental milestones (Rawat & Rawat, 2006). These cases broaden our understanding of retirement as a transition that encompasses not only later-life exits from the workforce but also bridge employment and phased retirement pathways.

Cross-cultural evidence further demonstrates how retirement can reshape family roles in practical and sometimes unexpected ways. In China, for example, fathers-in-law’s retirement has been shown to increase daughters-in-law’s labour force participation by freeing up time for household and childcare support (Yang et al., 2024), highlighting how retired parents’ availability can directly influence adult children’s economic activity. At the same time, adult children often interpret their parents’ retirement positively, viewing it as a well-deserved period of rest and renewal (D’Cruz, 2005; Loureiro et al., 2015). Taken together, these examples show that retirement is not merely an individual milestone but a complex social transition with far-reaching intergenerational implications, reshaping roles, redistributing responsibilities, and affecting the well-being of multiple family members across cultural and life-course contexts.

Grandparenthood, while often involving caregiving, may also strengthen family ties and dynamics more broadly. The transition to grandparenthood can influence the timing of major life-course decisions such as retirement, as some older adults choose to exit the labour market earlier to provide intergenerational support. Bolano and Bernardi (2024) show that becoming a grandparent increases the likelihood of early retirement for both men and women, with a somewhat stronger effect among grandmothers, suggesting that grandparenthood can function as a meaningful alternative social role to continued employment. Beyond the practical provision of childcare, grandparents’ involvement contributes to family cohesion, enhances life satisfaction, and reinforces intergenerational solidarity—effects that are particularly salient in contexts with low fertility and limited formal childcare (Bolano & Bernardi, 2024). Yet, research has paid little attention to the emotional, social, and identity transformations that accompany this new role. Recognizing these broader impacts invites a more holistic understanding of grandparenthood as a life transition that influences identity, enriches later-life well-being, and reconfigures intergenerational relationships.

The interconnectedness of spousal experiences and adjustments during retirement influences the broader family system, extending to intergenerational relationships (Fitzpatrick & Vinick, 2003; Loureiro et al., 2016). Retirement is a shared process rather than an individual event, involving joint decisions with repercussions for both partners (Moen et al., 2001; Nashef-Hamuda et al., 2025; D. B. Smith & Moen, 2004), though there is research that suggests that the degree of mutual influence during adjustment varies (van Solinge & Henkens, 2005). These dyadic dynamics, in turn, shape interactions with adult children and grandchildren; for example, a wife’s emotional outlook on her husband’s retirement can influence their engagement with younger generations (Hill & Dorfman, 1982). Furthermore, broader societal shifts, such as increased female labour participation and longer life expectancy, have transformed retirement from a male-centric event into a complex, shared family transition, thereby reconfiguring intergenerational roles and support structures within the family system (Mergenthaler & Cihlar, 2018).

Beyond financial or health outcomes, retirement influences family well-being through structural factors such as education and occupational status. Economic stability, often tied to pre-retirement occupation, is a key determinant of family life satisfaction (Hill & Dorfman, 1982; D. B. Smith & Moen, 2004). Men with lower education may remain in the workforce longer to support adult children, linking retirement timing directly to intergenerational financial support (Bolano & Bernardi, 2024). Lower educational attainment among spouses is associated with worse baseline health, while higher education can modestly buffer retirement’s long-term impact on spousal health (Curl & Townsend, 2013). Education also influences the likelihood of employment, with lower levels increasing the risk of unemployment. Because employment conditions accumulate across the life course, these stratification factors underpin varied health outcomes during retirement. Level of education also plays a role in how spouses adapt to retirement, with a wife’s higher education being important for her own adaptation (Haug et al., 1992). Together, these findings underscore education and occupation as key determinants of both individual and spousal health outcomes and broader family adjustments.

The timing and voluntariness of retirement are also factors with significant family-level implications, particularly for intergenerational dynamics. When retirement is early or involuntary, it can introduce substantial financial strain (Damman et al., 2019; Dow & Meyer, 2010). Families with dependent children may be affected, mainly when retirement occurs earlier in the life course, which can increase the vulnerability of the family unit (Rawat & Rawat, 2006). This financial precarity can directly influence children’s educational opportunities and prospects, creating ripple effects across generations. Moreover, the ability to control retirement timing could shape retirees’ capacity to provide intergenerational support, such as grandchild care or financial assistance to adult children, or conversely, their need for support from younger generations. These factors underscore that retirement timing is not merely an individual preference but a powerful determinant of the family’s long-term adaptive capacity and the well-being of its members across the life course.

4. Discussion

This scoping review critically examined the relational impacts of retirement, moving beyond mapping the literature to addressing a gap concerning the comprehensive integration of work-family life courses with family-level dynamics. While prior syntheses, such as those by Fisher et al. (2016) and Teques et al. (2025), offer valuable insights into individual-level determinants and well-being indicators, they largely omit the interdependent processes within couples and families. This review, by contrast, foregrounds the couple or family as the primary unit of analysis, providing a more integrated, system-oriented understanding of how retirement transitions reverberate across family systems. This approach allows us to consider retirement not merely as an individual event, but as a disturbance or reconfiguration of an existing family ecology, where various relational, occupational, and life-course dimensions combine to shape adaptation. The predominance of couple-focused studies reflects the structure of the existing literature rather than our conceptual intent. This limits the ability to capture retirement within diverse later-life family configurations such as cohabiting partnerships, blended families, single-parent households, and chosen families. Our review further highlights the need for a more nuanced understanding of later-life partnership dynamics. Although we identified themes related to marital quality and conflict, a more explicit focus on broader demographic trends, such as the increasing prevalence of grey divorce and other forms of partnership instability in later life, was less prominent in the synthesized literature. This suggests a gap in how retirement research has historically engaged with the full spectrum of relational contexts beyond intact, long-term marriages. This limitation is further amplified by the historical context of many studies, which reflect norms around marriage, cohabitation, and divorce, that have significantly evolved. Accordingly, the ways families experience retirement across more diverse later-life relationships and family configurations may not be fully captured in the evidence informing this review. Taken together, these gaps point to the value of an integrative perspective that more fully reflects the diverse relational contexts through which families navigate retirement in contemporary later life.

The collective findings from the 61 included studies strongly affirm the utility of Family Life Course Theory and Family Systems Theory in understanding retirement. The consistent demonstration that changes experienced by one family member during retirement inevitably influence the entire family unit, affecting communication, roles, and collective well-being, directly supports Family System Theory’s core tenet of inherent interconnectedness and illustrates how these elements form complex patterns of adaptation (McCubbin & Patterson, 1983; Papero, 1990). Similarly, the observed variations in retirement trajectories and their impacts across families underscore Life Course Theory’s emphasis on the cumulative nature of work and family experiences throughout the lifespan (Elder & Giele, 2009). This reinforces the conceptualization of retirement as an inherently relational and systemic transition, moving beyond individual-centric paradigms and offering key theoretical implications for future research.

The analysis identifies recurring configurations of factors that shape family adaptation to retirement. We move beyond merely describing individual themes to analyze how elements such as gendered work histories, financial security, pre-retirement marital quality, and caregiving obligations interact and combine to produce specific family-level outcomes. For instance, a combination of strong pre-retirement marital quality and adequate financial security often buffers the family unit against potential strains, leading to smoother dyadic adjustments and enhanced well-being. Conversely, pre-existing marital conflict coupled with financial precarity can amplify tensions and lead to less favorable outcomes, particularly for women who often bear a disproportionate share of caregiving responsibilities and experience greater economic vulnerability post-retirement.

A key strength of this review was the deliberate inclusion of studies on younger retirees and the absence of date restrictions. Although most identified studies focused on later-life retirement, a small subset examined retirement occurring earlier in the life course, such as among athletes or military personnel. This breadth allowed us to capture a wider spectrum of relational impacts, revealing how diverse retirement trajectories, from early career shifts to later-life cessation of work, manifest in varied family dynamics and across different historical and social contexts. While most included studies were more recent (since 2000), the range of publication years ensured that both enduring and evolving patterns in family adaptation to retirement were reflected in our thematic synthesis.

An emergent insight from this analysis is the pervasive and asymmetrical role gender plays in shaping retirement adaptation within families. Our findings consistently reveal that gender is not merely a demographic variable but a fundamental organizing principle that shapes patterned experiences across all identified themes. This observation is reinforced by Harris and Fasbender (2025), whose systematic review of retirement decisions and outcomes demonstrates that gendered roles and norms significantly influence life-course trajectories, particularly in shaping retirement timing, financial security, and post-retirement well-being. For instance, the recurring theme of impingement, where a retired husband is perceived as intruding on his wife’s established routines, illustrates how deeply ingrained gendered expectations around domestic space and activity, often reinforced by occupational histories and societal norms, can generate marital strain, a pattern observed from early studies (Heyman, 1970) through to contemporary research (Foley et al., 2023; Mergenthaler & Cihlar, 2018). This goes beyond simply noting that men and women experience retirement differently; it highlights how deeply ingrained gender roles, often reinforced by occupational histories and societal norms, lead to uneven burdens and benefits within the family unit, forming distinct gendered patterns of adaptation. Notably, these gendered patterns are most pronounced in earlier studies, reflecting traditional norms (Fengler, 1975; Keating & Cole, 1980), yet they remain evident in research from the past decade (Cooley & Adorno, 2016; Hwang et al., 2025), indicating continuity alongside gradual shifts in how these patterns are expressed. In line with these enduring patterns, unpaid caregiving remains central to women’s retirement experiences, including grandchild care and the disproportionate and heightened demands of spousal support in later life (Bolano & Bernardi, 2024; Caltabiano et al., 2016). These overlapping forms of care work sustain gendered divisions of labour and shape the timing and conditions under which women exit paid employment. This persistence underscores the enduring influence of gender norms on retirement pathways, with women often retiring earlier due to caregiving responsibilities and societal expectations, a pattern consistently documented across both European contexts and the U.S.A. (Harris & Fasbender, 2025). The evidence points to important conceptual insights into gendered experiences of retirement.

Findings suggest that, although men may increase their participation in household tasks, this often does not alleviate the overall burden on wives, who frequently retain primary responsibility for domestic and caregiving roles. This finding aligns with feminist theories of labour and care, which highlight the persistent undervaluation and unequal distribution of unpaid work (Folbre, 2001). It is reinforced by the concept of “mental load,” defined by Dean et al. (2022) as the invisible, boundaryless, and enduring cognitive and emotional labour involved in managing family life. Even when men increase their physical contributions to domestic tasks post-retirement, the underlying mental load often remains with women (Barnes & Parry, 2004; Caltabiano et al., 2016), contributing to greater adjustment challenges and perpetuating gender inequalities. These dynamics extend beyond domestic labour into financial satisfaction and intra-household power relations. Men’s retirement can reduce household income, causing women’s economic well-being to stagnate or decline (Haug et al., 1992; Heyman, 1970; Keating & Cole, 1980). This outcome reflects persistent gendered disparities in access to and accumulation of financial resources, highlighting the spillover effects of retirement and the economic vulnerability that women can experience (Austen et al., 2022).

Furthermore, gender differences are central to emotional and relational dynamics, reflecting broader psychological literature on gendered emotional expression and coping strategies (Eagly, 1987). Women generally experience greater challenges adjusting to retirement due to persistent obligations and a greater tendency to report negative feelings (Cooley & Adorno, 2016), while men often report improved marital satisfaction (Barnes & Parry, 2004; D. B. Smith & Moen, 2004). This aligns with findings that women are more likely to retire early to assume caregiving roles, often compromising their financial security, while men tend to delay retirement to provide financial support, reflecting traditional gender norms (Harris & Fasbender, 2025). The reliance of husbands on wives for social support can amplify strain if wives cannot accommodate these needs (Keating & Cole, 1980; D. B. Smith & Moen, 2004), underscoring the emotional asymmetry in adjustment. Health outcomes also exhibit gendered patterns; men’s own retirement tends to negatively affect their self-rated health, but their wives’ retirement does not significantly affect men’s long-term health (Curl & Townsend, 2013). Conversely, women’s health appears more sensitive to both their own and their spouse’s retirement, with self-reported chronic conditions more influenced by both (Newmyer et al., 2023). For example, a husband’s poor health can significantly increase his likelihood of retiring early and jointly, whereas wives’ decisions are more influenced by their spouse’s health than their own (Harris & Fasbender, 2025). These gendered patterns also illustrate how retirement can function as a life-course transition that is differentially structured by institutional expectations and caregiving norms, producing uneven coordination of roles across partners. The findings collectively demonstrate that gender is a critical lens through which to understand the complexities of retirement’s impact on family well-being.

This review also underscores the critical predictive power of pre-retirement family circumstances and occupational characteristics in shaping post-retirement well-being, a central tenet of the life course perspective (Elder & Giele, 2009). These factors, which can lead to divergent life pathways (life-course bifurcations) or structured, socially recognized shifts (institutionalized transitions), include the quality of the marital relationship before retirement, the financial security derived from one’s career, and even the voluntariness of the retirement decision. Together, they emerge as powerful determinants of how successfully families navigate this transition. In this sense, retirement represents not only a major institutional transition but also a potential point of incomplete coordination when partners’ timing, expectations, or resources do not align, reinforcing Elder and Giele’s (2009) emphasis on the timing and sequencing of lives. This synthesis moves beyond a simple correlation, suggesting that these factors act as foundational elements that either buffer against or amplify the stresses of retirement, consistent with continuity theory’s emphasis on maintaining established patterns of behaviour, identity, and social relationships across the life course, and contributing to varied adaptive patterns in retirement.

From an ecological standpoint, our analysis moves from a thematic map to a more integrated understanding, highlighting how the interplay of micro-level relational dynamics (such as dyadic adjustment, emotional contagion, and the negotiation of domestic roles), meso-level family configurations (including family systems, intergenerational arrangements, and shared time structures), and macro-level societal conditions (like pension regimes, gendered labour markets, and cultural norms around care) are not merely co-occurring but are deeply interconnected and mutually influential in shaping family-level outcomes. This multi-level perspective reveals how immediate interactions, broader family structures, and wider societal forces are not isolated but are deeply intertwined, creating complex patterns of adaptation to retirement. The so what here is that interventions and policy considerations for retirement planning must extend far beyond individual financial literacy. They must encompass comprehensive family-level assessments that address relational health, role expectations, and the potential financial strain on all family members, not just the retiree, recognizing that pre-existing conditions profoundly shape the adaptive capacity of the entire family system.

4.1. Implications

The insights generated by this scoping review have implications for future research, practice, and policy. For the research community, this review serves as a comprehensive map, identifying not only well-trodden paths but also significant unexplored territories. The most glaring gap remains the overwhelming heteronormative bias in the existing literature, which severely limits our understanding of retirement’s relational impacts on diverse family structures, including same-sex couples and single-parent households. Furthermore, while our review underscores the importance of marital quality, it also reveals a relative lack of attention in the literature to the broader demographic and relational context of aging, specifically phenomena like grey divorce and other forms of partnership instability in later life. These omissions limit our understanding of how retirement transitions may interact with, or be impacted by, such significant life changes. Notably, despite our framing of the review as family-centred, the empirical literature itself remains largely couple-focused, often implicitly equating family with a long-term marital dyad. This narrow focus restricts the ability to fully capture retirement as an event occurring within the increasingly diverse family configurations prevalent in later adulthood. Future research must actively seek to diversify samples and methodologies to capture these underrepresented experiences. From a research design perspective, the consistent call for longitudinal studies is reinforced, as cross-sectional approaches are inherently limited in capturing the dynamic and evolving nature of family adaptation. For practitioners, the findings advocate for a paradigm shift towards family-centred retirement counselling. This would involve addressing not just financial planning, but also proactive discussions around role renegotiation, managing increased shared time, anticipating emotional adjustments, and acknowledging potential gendered disparities in workload and well-being, recognizing how these elements interact within the family system. For policymakers, the review highlights the need for support systems that recognize the family as an interdependent unit, informing policies related to caregiving, social support networks, and flexible work arrangements that account for the diverse needs and experiences of all family members during retirement.

4.2. Limitations

While this review provides a valuable synthesis, it is important to acknowledge its inherent limitations. Despite employing rigorous, systematic search strategies across multiple databases, the expansive, interdisciplinary nature of retirement research means that some pertinent literature, particularly from highly specialized or emerging subfields, might have been inadvertently overlooked. This is an inherent challenge in any comprehensive review, especially in a scoping review, which prioritizes mapping the breadth of a field rather than exhaustive capture of every piece of evidence. We also note that, while methodologically sound for the scope of this review, the exclusion of grey literature means that some practical or policy-oriented insights, particularly relevant to later-life family dynamics, may not be fully represented. As a scoping review, the primary objective was to delineate the scope and nature of the existing literature rather than to conduct an in-depth critical appraisal of the methodological quality of individual studies. Consequently, while overarching themes and patterns were identified, the strength of the evidence for each theme was not individually assessed, and the specific nuances of particular study designs or potential biases within the primary literature were not examined in detail. Future systematic reviews building on this foundation could incorporate a quality appraisal to provide a more nuanced understanding of the evidence base.

A notable methodological limitation concerns the temporal nature of the data, particularly within qualitative research. Our analysis revealed that all 15 qualitative studies included in this review were cross-sectional. While these studies offer rich, in-depth insights into subjective experiences and perceptions at a given point in time, their cross-sectional design means they often rely on participants’ recollections of past events and transitions. This introduces a potential for recollection bias, where individuals’ current perspectives or emotional states might influence their recall of previous situations, potentially shaping the reported experiences of retirement and family dynamics. This is a significant consideration, as much of the nuanced understanding of relational impacts, emotional adjustments, and role renegotiations presented in our themes is drawn from these qualitative accounts. In contrast, a substantial majority of the quantitative studies (29 out of 41) were longitudinal, providing a stronger basis for understanding causal pathways and changes over time. However, the absence of longitudinal qualitative data limits our ability to fully capture the dynamic, evolving nature of family adaptation to retirement through lived experience over extended periods. This methodological imbalance suggests that while we have a better understanding of what changes occur (from quantitative longitudinal data), the in-depth understanding of how and why these changes unfold over time, as perceived by individuals, is more heavily influenced by retrospective accounts.

Furthermore, while our review aimed for a global perspective, the geographical distribution of the included studies presents a limitation regarding the generalizability of our findings. The largest proportion of studies (n = 26) originated from the United States, with other regions less frequently represented (see Appendix A for full details). This geographical concentration means that many of the insights and identified themes may be predominantly shaped by cultural, social, and economic contexts prevalent in these regions, particularly Western societies. Consequently, the applicability of these findings to more diverse global contexts, with varying retirement policies, family structures, and cultural norms around aging, may be limited. Future research would benefit from a broader geographical scope to capture the full spectrum of relational impacts of retirement worldwide.

Additionally, while marital quality and conflict were identified as key themes, our synthesis found limited explicit attention to the broader demographic and relational context of aging, such as later-life divorce and other forms of partnership instability. The interplay between retirement transitions and these significant relational changes remains an underdeveloped area within the current body of literature we reviewed. Moreover, because many of the findings synthesized in this review are derived from older studies conducted largely in Western contexts, their applicability to today’s more diverse and fluid family and partnership patterns is uncertain. Contemporary developments in aging—such as longer life expectancy, increased repartnering, and more complex later-life family structures—may shape retirement dynamics in ways not reflected in this earlier evidence. Despite our family-centred framing, the empirical literature continues to operate from an implicitly couple-centred lens, commonly equating family with a marital dyad. This limits the ability of our review to fully capture retirement as an event occurring within the increasingly diverse family configurations present in later adulthood. A further limitation concerns the terminology used throughout the presentation of themes. The terms “husbands” and “wives” appear frequently, reflecting the language of the original studies, many of which were conducted within heteronormative frameworks and published before 2000. This language fails to capture the diversity of contemporary couple and family relationships and, in doing so, constrains how partnership is understood within the literature. We encourage future research to adopt more inclusive language and examine broader relational configurations.

5. Conclusions

Retirement is more than a personal milestone; it is a relational turning point that reshapes the family system. Through a family-centric lens, this review maps the ripple effects of retirement across roles, dynamics, and collective well-being. Anchored in Family Life Course and Family Systems Theories, our synthesis reveals the profound interdependence among family members during this pivotal life stage. While scoping reviews are inherently exploratory, a significant aspect of this work is its ability to move beyond mere description, offering a more integrated understanding of family adaptation to retirement. This is achieved by identifying and analyzing how recurring combinations of factors—such as gendered work histories, financial security, pre-retirement marital quality, and caregiving obligations—appear to shape diverse family-level outcomes. This reframing of retirement as a shared process rather than an isolated event offers a compelling argument for a paradigm shift in how retirement is conceptualized and addressed. It provides a clear mandate for future research to pursue more inclusive and integrated studies, and for practitioners and policymakers to develop family-centred approaches that recognize and respond to role renegotiation, emotional adjustment, and gendered disparities, while strengthening relational resilience. Future scholarship must move beyond heteronormative and individual-centric models to adopt inclusive, longitudinal approaches that capture diverse family structures and interdependencies, including blended, multigenerational, and non-marital forms as well as the complexities of partnership stability and dissolution in later life. This also necessitates a broader conceptualization of family to encompass the full spectrum of contemporary family forms and to explicitly reflect on how evolving social norms and demographic trends in aging reshape retirement experiences. Ultimately, this synthesis provides a foundation for understanding retirement as a relational turning point and offers guidance for interventions that enhance the well-being of families navigating this universal and transformative life stage.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/famsci2010004/s1, Table S1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and H.C.; methodology, M.C.; formal analysis, M.C.; resources, H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C. and H.C.; project administration, M.C. and H.C.; funding acquisition, H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research in the 201911 Team Grant: Mental Wellness in Public Safety Team Grants, and the Article Processing Charge received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The list of all included articles, together with their key themes and findings, is provided in Appendix A. Full references for all included articles are available in the reference list. The registered protocol is accessible through the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/g82kj/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the valuable contributions of research trainees Clare Ashton, Megan Christoforidis, Jasmin Ezaddoustdar, Abebe Getachew Fantaw, Samantha Rae, and Mikayla Smith with the School of Rehabilitation Therapy, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, whose contributions to the literature review and synthesis were integral to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary table of included literature.

Table A1.

Summary table of included literature.

| Author/Year | Country | Design | Primary Themes | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Agnew et al., 2025) | Australia | qualitative cross- sectional | time use; dyadic adjustments; financial impacts | Retired rugby players observed their transition affected partners through changes in family time, lifestyle, and relationship dynamics. |

| (Alvarez et al., 2007) | U.S.A. | mixed methods cross- sectional | emotional & psych. effects; marital quality; redistribution of domestic roles | Formal support helped retired firefighters and families navigate identity loss/marital issues post 9/11, improving satisfaction/problem resolution. |

| (Atalay & Zhu, 2018) | Australia | quantitative longitudinal | health outcomes; time use; emotional & psych. effects | Wives’ retirement positively impacts husbands’ mental health and social engagement, strengthening over time. |

| (Austen et al., 2022) | Australia | quantitative longitudinal | financial impacts; time use; redistribution of domestic roles | Retirement impacts well-being differently for men and women within couples, with gendered financial and free time outcomes. |

| (Barnes & Parry, 2004) | U.K. | qualitative cross- sectional | financial impacts; time use; redistribution of domestic roles | Gendered roles and flexible approaches to identity significantly impact retirement adjustment and marital dynamics. |

| (Bertoni & Brunello, 2017) | Japan | quantitative longitudinal | health outcomes; emotional & psych. effects; financial impacts | Husband’s earlier retirement negatively impacts wife’s mental health in Japan. |

| (Bolano & Bernardi, 2024) | International | quantitative longitudinal | financial impacts; time use; intergenerational dynamics | Becoming a grandparent increases early retirement chances, especially for grandmothers and highly educated grandfathers. |

| (Bonsang & van Soest, 2020) | Germany | quantitative longitudinal | dyadic adjustment; time use; redistribution of domestic roles | Retirement increases both partners’ household work, with each partner’s retirement slightly reducing the other’s contribution. |

| (Bozoglan, 2015) | Turkey | quantitative cross- sectional | marital quality; dyadic adjustments; redistribution of domestic roles | Dyadic adjustment mitigates the negative effect of spousal intrusion on wives’ marital satisfaction during their husbands’ retirement. |

| (Brown et al., 2019) | U.K. | qualitative cross- sectional | financial impacts; emotional & psych. effects; dyadic adjustments | Elite athletes’ retirement is a shared family transition, impacting parents’ and partners’ identities and relationships. |

| (Bushfield et al., 2008) | U.S.A. | quantitative cross- sectional | marital quality; dyadic adjustments; redistribution of domestic roles | As husbands’ retirement advanced, wives’ impingement perceptions increased, and were more strongly linked to marital dissatisfaction. |

| (Caltabiano et al., 2016) | Italy | quantitative longitudinal | redistribution of domestic roles; time use; intergenerational dynamics | After retirement, Italian men take on more household work, but traditional gender ideology limits this increase. |

| (Chen, 2022) | China | quantitative longitudinal | health outcomes; time use; redistribution of domestic roles | Retirement affects men’s and women’s health in distinct ways, shaped by marital dynamics and whether a spouse also retires. |

| (Cliff, 1993) | U.K. | qualitative cross- sectional | marital quality; dyadic adjustments; redistribution of domestic roles | Early retirement prompts varied gender role renegotiations, from increased sharing to reinforced traditional divisions, impacting marital adjustment. |

| (Cohn-Schwartz et al., 2021) | Switzerland | quantitative longitudinal | marital quality; dyadic adjustment; time use | Retirement increases spouses shared social activities and network overlap, especially for husbands. |

| (Cooley & Adorno, 2016) | U.S.A. | qualitative cross- sectional | marital quality; dyadic adjustments; financial impacts | For working women, communication and planning are essential to navigating a partner’s retirement and shifting family dynamics. |