Community and Scientists Work Together to Identify Koalas Within the Plantations Inside the Proposed Great Koala National Park in New South Wales, Australia

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

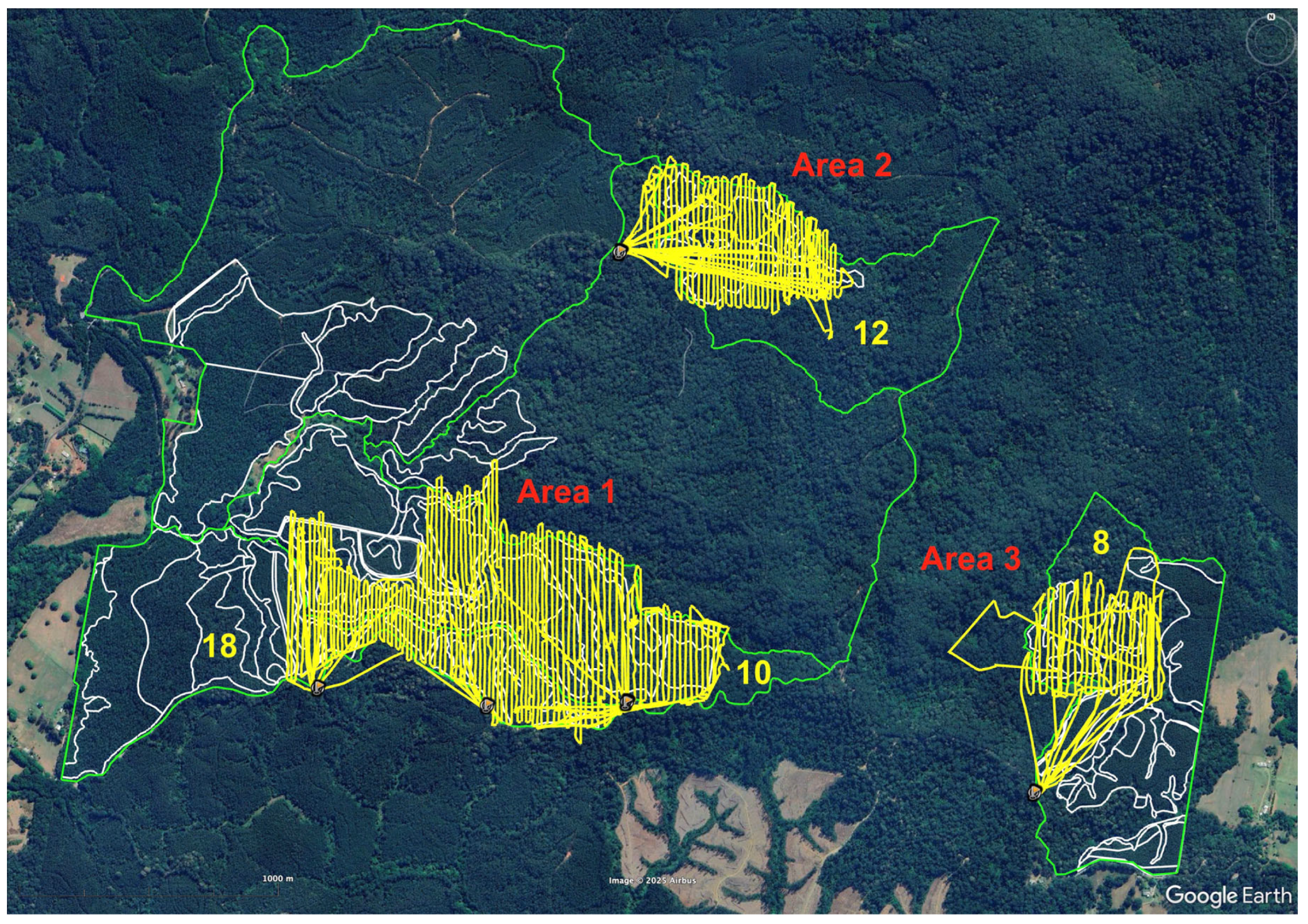

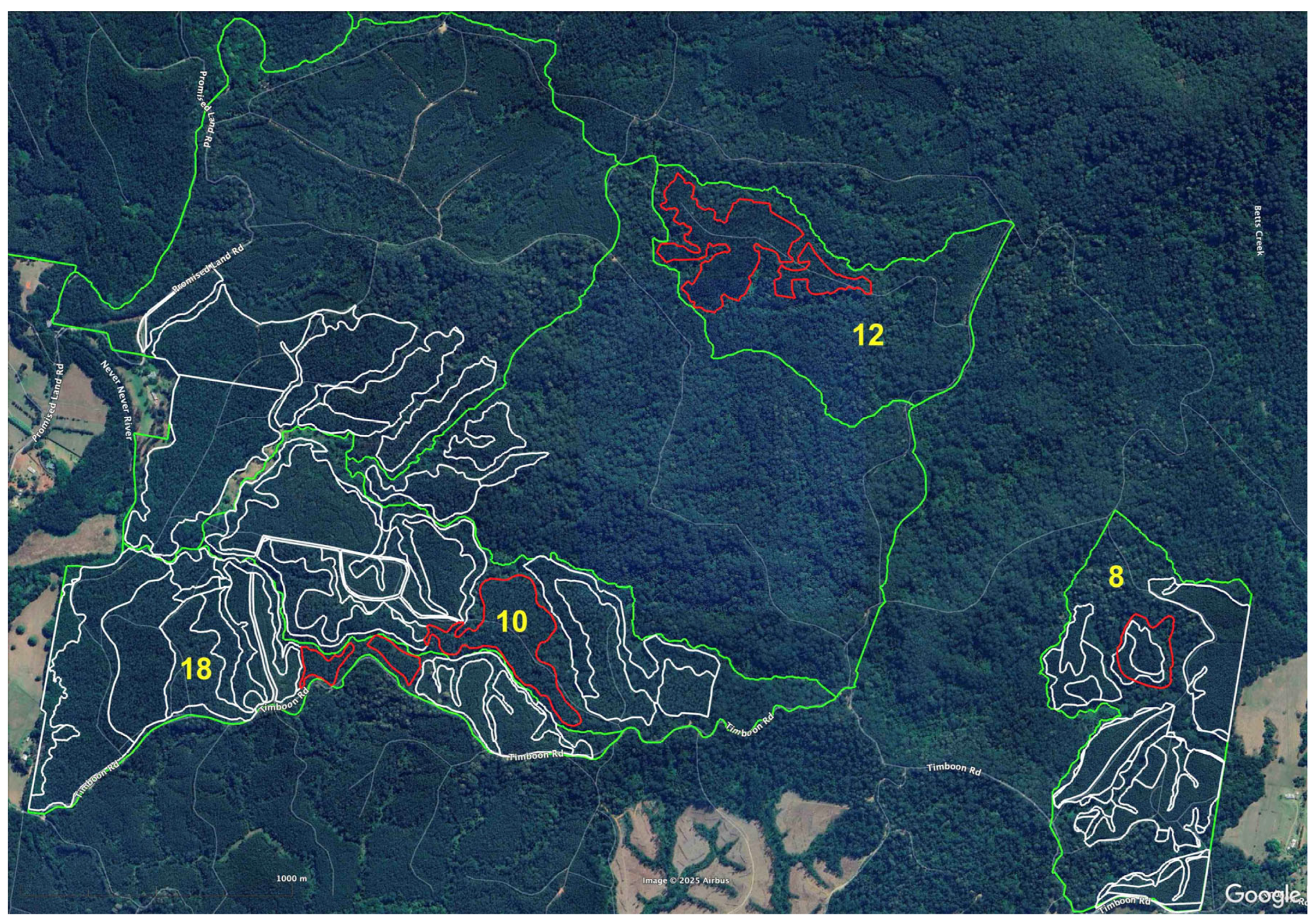

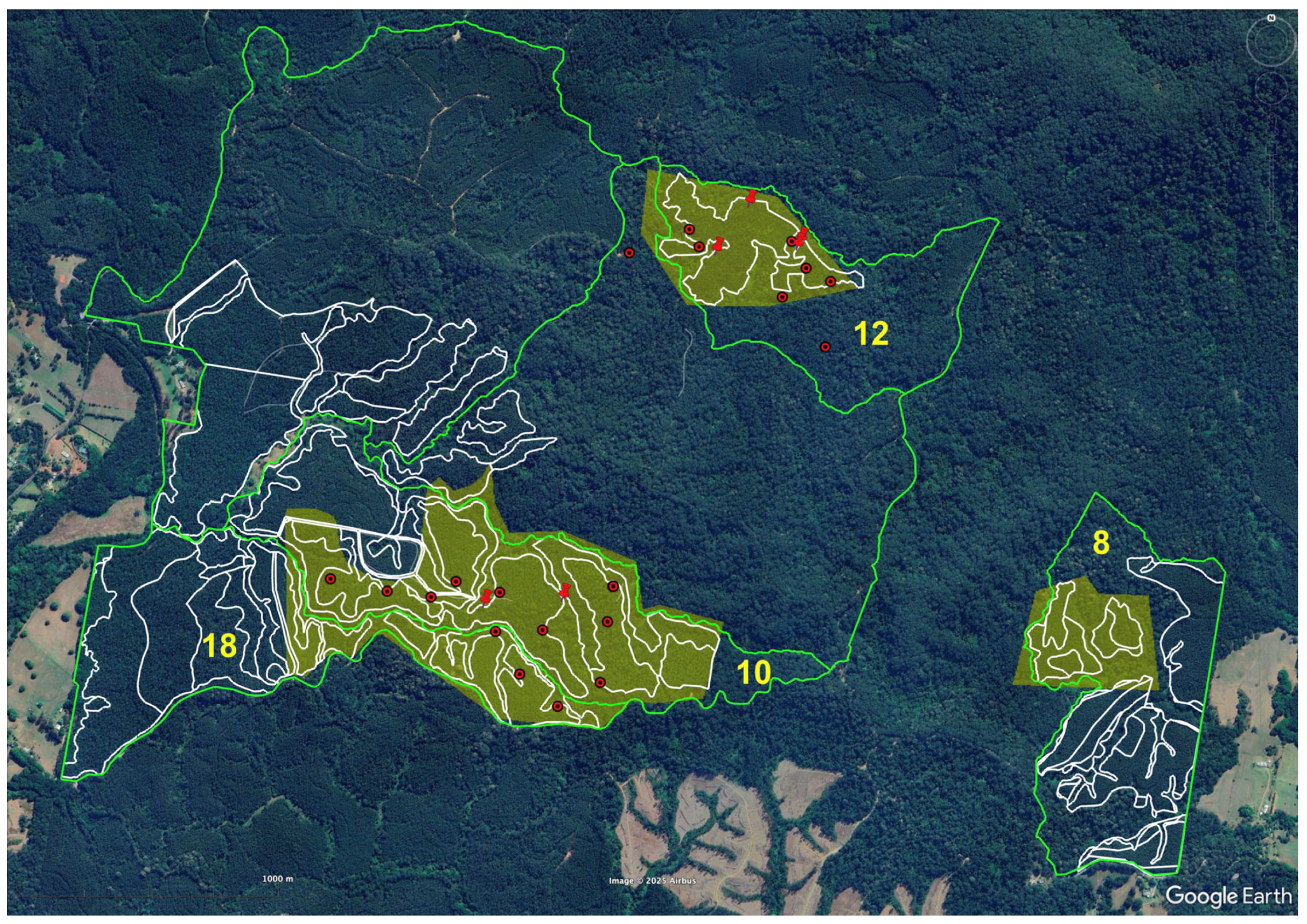

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Original Trees and Forest Remnants

2.2.2. Koala Records

- Area 1, partially covering the plantations in compartments 10 and 18 (94 ha);

- Area 2, encompassing all the plantations in compartment 12 (29 ha);

- Area 3, including some of the plantations in compartment 8 (19 ha).

2.3. Caveats

3. Results

3.1. Remnant Forest and Original Trees

3.2. Koala Scats and Sightings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. Conservation Advice for Phascolarctos cinereus (Koala) Combined Populations of Queensland, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory; Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment: Canberra, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cadman, T.; Schlagloth, R.; Santamaria, F.; Morgan, E.; Clode, D.; Cadman, S. Koalas, Climate, Conservation, and the Community: A Case Study of the Proposed Great Koala National Park, New South Wales, Australia. Int. J. Soc. Qual. 2023, 13, 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahir, F.; Schlagloth, R.; Clark, I.D. The historic importance of the koala in Aboriginal society in New South Wales, Australia: An exploration of the archival record. ab-Orig. J. Indig. Stud. First Nations First Peoples’ Cult. 2020, 3, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadman, T.; Clode, D. A Home Among the Gum Trees: Will the Great Koala National Park Actually Save Koalas? The Conversation. 2023. Available online: https://theconversation.com/a-home-among-the-gum-trees-will-the-great-koala-national-park-actually-save-koalas-217276 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Cadman, T.; Macdonald, K.; Morgan, E.; Cadman, S.; Karki, S.; Dell, M.; Barber, G.; Koju, U. Forest conversion and timber certification in the public plantation estate of NSW: Implications at the landscape and policy levels. Land Use Policy 2024, 143, 107179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leys, A.J.; Vanclay, J.K. Land-use change conflict arising from plantation forestry expansion: Views across Australian fencelines. Int. For. Rev. 2010, 12, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, C.A.; Rhodes, J.R.; Callaghan, J.G.; Bowen, M.E.; Lunney, D.; Mitchell, D.L.; Pullar, D.V.; Possingham, H.P. The importance of forest area and configuration relative to local habitat factors for conserving forest mammals: A case study of koalas in Queensland, Australia. Biol. Conserv. 2006, 132, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlagloth, R.; Golding, B.; Kentish, B.; McGinnis, G.; Clark, I.D.; Cadman, T.; Cahir, F.; Santamaria, F. Koalas–Agents for Change: A case study from regional Victoria. J. Sustain. Educ. 2022, 26, 1–16. Available online: https://www.susted.com/wordpress/?s=koala (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Schlagloth, R.; Santamaria, F.; Golding, B.; Thomson, H. Why is It Important to Use Flagship Species in Community Education? The Koala as a Case Study. Anim. Stud. J. 2018, 7, 127–148. [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira, A.M.M.; Roetman, P.E.J.; Daniels, C.B.; Baker, A.K.; Bradshaw, C.J.A. Distribution models for koalas in South Australia using citizen science-collected data. Ecol. Evol. 2014, 4, 2103–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; McAlpine, C.; Rhodes, J.; Lunney, D.; Goldingay, R.; Fielding, K.; Hetherington, S.; Hopkins, M.; Manning, C.; Wood, M.; et al. Assessing the validity of crowdsourced wildlife observations for conservation using public participatory mapping methods. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 227, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollow, B.; Roetman, P.E.; Walter, M.; Daniels, C.B. Citizen science for policy development: The case of koala management in South Australia. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 47, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, E.; Jones, D.; Bernede, L. Can citizen science assist in determining koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) presence in a declining population? Animals 2016, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenhouse, A.; Roetman, P.; Lewis, M.; Koh, L.P. Koala Counter: Recording citizen scientists’ search paths to improve data quality. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 24, e01376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, R.B.; Stevenson, M.; Allavena, R.; Henning, J. The value of long-term citizen science data for monitoring koala populations. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaher, M.; Schlagloth, R.; Hewson, M.; Geddes, C. One person and a camera: A relatively non-intrusive approach to Koala citizen science. Aust. Zool. 2023, 43, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, G. Welcome to the anatomy of the great koala count. Nat. N. S. W. 2013, 57, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Predavec, M.; Lunney, D.; Shannon, I.; Lemon, J.; Sonawane, I.; Crowther, M. Using repeat citizen science surveys of koalas to assess their population trend in the north-west of New South Wales: Scale matters. Aust. Mammal. 2017, 40, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSW Government (Office of Environment and Heritage). Squirrel Glider Profile. 2024. Available online: https://threatenedspecies.bionet.nsw.gov.au/profile?id=10604 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- NSW Government (Office of Environment and Heritage). Southern Greater Glider. 2024. Available online: https://threatenedspecies.bionet.nsw.gov.au/profile?id=20306 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Government of NSW Spatial Services. NSW Elevation Data Service. 2023. Available online: https://portal.spatial.nsw.gov.au/portal/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=437c0697e6524d8ebf10ad0d915bc219 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Briggs, J.; Prahalad, V.; Sharples, C.; Dell, M. An Adaptive Multiple-Criteria Decision Analysis Approach to Mapping Regional-Scale Post-Colonisation Changes to the Tidal Wetlands of Kanamaluka/River Tamar, Tasmania, Australia. In Estuaries and Coasts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; Volume 48, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Committee on Surveying and Mapping (Undated). Elvis—Elevation and Depth—Foundation Spatial Data, Undated. Available online: https://elevation.fsdf.org.au (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Government of NSW Spatial Services. Six Maps. 2023. Available online: https://maps.six.nsw.gov.au (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Avenza Systems Inc. System Software Company. 2025. Available online: www.avenza.com (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Nearmap. Turn Location Data into Insightful Answers. 2025. Available online: www.nearmap.com/au (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Canines for Wildlife. Conservation Detection Dogs. 2025. Available online: https://caninesforwildlife.com/ (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- State of NSW and Department of Planning Environment Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) Biodiversity Assessment Method Survey Guide Environment Heritage Group Department of Planning Environment Parramatta NSW. 2022. Available online: https://www2.environment.nsw.gov.au/publications/koala-phascolarctos-cinereus-biodiversity-assessment-method-survey-guide (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Ryan, S.A.; Southwell, D.M.; Beranek, C.T.; Clulow, J.; Jordan, N.R.; Witt, R.R. Estimating the landscape-scale abundance of an arboreal folivore using thermal imaging drones and binomial N-mixture modelling. Biol. Conserv. 2025, 309, 111207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beranek, C.T.; Roff, A.; Denholm, B.; Howell, L.G.; Witt, R.R. Trialling a real-time drone detection and validation protocol for the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Aust. Mammal. 2020, 43, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geocentric Datum of Australia. The Australian Geospatial Reference System. Intergovernmental Committee on Survey and Mapping. 1994. Available online: https://www.icsm.gov.au/datum/geocentric-datum-australia-1994-gda94. (accessed on 10 August 2024).

- Glascott, J. From the Archives, 1982: Conservationists Win the Rainforest Battle; Sydney Morning Herald: North Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1982; Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/environment/conservation/from-the-archives-1982-conservationists-win-the-rainforest-battle-20221017-p5bqgk.html (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Australian Government Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, National Vegetation Information System (NVIS). 2025. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/environment-information-australia/national-vegetation-information-system (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Walstra, J.; Chandler, J.; Dixon, N.; Wackrow, R. Evaluation of the controls affecting the quality of spatial data derived from historical aerial photographs. Earth Surf. Process Landf. 2011, 36, 853–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Miller, C.C.; Bethel, J. Automated georeferencing of historic aerial photography. J. Terr. Obs. 2010, 2, 6. [Google Scholar]

- FCNSW Forestry Corporation of NSW Hardwood Forests Division Draft Plantation Harvest Map Tuckers Nob State Forest Compartments TCK_008_10-_11_12_17_18, 2024. Crown Copyright 2013. Available online: https://aws-codestar-ap-southeast-2-712553626359-plans-webapp-files.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/HPRP_TUCKERS_NOB_Plantation_8_10_11_12_17_18_Locality.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Schlagloth, R.; Santamaria, F.; Mitchell, D.; Rhodes, J. Use of Blue Gum Plantations by Koalas—A Report to Stakeholders in the Plantation Industry; Australian Koala Foundation: Brisbane, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.P.; Pile, J. Koala density, habitat, conservation, and response to logging in eucalyptus forest; a review and critical evaluation of call monitoring. Aust. Zool. 2024, 44, 44–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, R.; Antoniou, V.; Hummer, P.; Potsiou, C. Citizen science in the digital world of apps. In The Science of Citizen Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 461–474. [Google Scholar]

| Source | Name | Date | Scale | Resolution (dpi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSW Historical Imagery | 1279_09_249.jp2.jpeg | 12/8/1964 | 1:40,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 1279_09_250.jp2.jpeg | 12/8/1964 | 1:40,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 1279_09_251.jp2.jpeg | 12/8/1964 | 1:40,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 1279_10_263.jp2.jpeg | 12/8/1964 | 1:40,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 1279_10_264.jp2.jpeg | 12/8/1964 | 1:40,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 1279_10_265.jp2.jpeg | 12/8/1964 | 1:40,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 2256_07_117.jp2.jpeg | 18/8/1974 | 1:40,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 2256_07_118.jp2.jpeg | 18/8/1974 | 1:40,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 3405_07_031.jp2.jpeg | 2/9/1984 | 1:40,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 3405_07_030.jp2.jpeg | 2/9/1984 | 1:40,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 4197_11_071.jp2.jpeg | 17/5/1994 | 1:25,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 4197_11_072.jp2.jpeg | 17/5/1994 | 1:25,000 | 600 |

| NSW Historical Imagery | 4197_11_073.jp2.jpeg | 17/5/1994 | 1:25,000 | 600 |

| SIX Maps | Dorrigo_2009_41 | 11/9/2009 | 1:5669 | 72 |

| SIX Maps | l8olps_nsw_2014_dbal0 | 1/1/2014 | 1:5669 | 72 |

| Compartment | Year Established | Area (ha) | Planned Operations | Remnants (n) | Area (ha) | Trees (n) | Koala Scats (n) | Sightings (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCK008 | 1992 | 2.79 (1.23; 1.56) | Delayed Thinning | 4 | 0.14 | |||

| Subtotal | 12 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| TCK010 | 1964 | 10 | Clearfall—Stage 1 | 22 | 3.44 | |||

| Subtotal | 198 | 2 | 10 | |||||

| TCK011 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Subtotal | 1 | |||||||

| TCK012 | 1989 | 14.57 (11.8; 2.77) | Delayed Thinning | 20 | 2.27 | |||

| Subtotal | 182 | 4 | 7 (5) | |||||

| TCK018 | 1980 | 2.83 (1.44; 1.39) | Thinning—Stage 2 | 3 | 0.52 | |||

| Subtotal | 46 | 0 | 3 | |||||

| Grand totals | 30.19 | 49 | 6.37 | 438 | 6 | 21 (2 outside survey) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schlagloth, R.; Santamaria, F.; Cadman, T.; McEwan, A.; Danaher, M.; McGinnis, G.; Clark, I.D.; Cahir, F.; Cadman, S.; Dell, M. Community and Scientists Work Together to Identify Koalas Within the Plantations Inside the Proposed Great Koala National Park in New South Wales, Australia. Wild 2025, 2, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2040042

Schlagloth R, Santamaria F, Cadman T, McEwan A, Danaher M, McGinnis G, Clark ID, Cahir F, Cadman S, Dell M. Community and Scientists Work Together to Identify Koalas Within the Plantations Inside the Proposed Great Koala National Park in New South Wales, Australia. Wild. 2025; 2(4):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2040042

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchlagloth, Rolf, Flavia Santamaria, Tim Cadman, Alexandra McEwan, Michael Danaher, Gabrielle McGinnis, Ian D. Clark, Fred Cahir, Sean Cadman, and Matt Dell. 2025. "Community and Scientists Work Together to Identify Koalas Within the Plantations Inside the Proposed Great Koala National Park in New South Wales, Australia" Wild 2, no. 4: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2040042

APA StyleSchlagloth, R., Santamaria, F., Cadman, T., McEwan, A., Danaher, M., McGinnis, G., Clark, I. D., Cahir, F., Cadman, S., & Dell, M. (2025). Community and Scientists Work Together to Identify Koalas Within the Plantations Inside the Proposed Great Koala National Park in New South Wales, Australia. Wild, 2(4), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/wild2040042