Abstract

This study explores how artificial intelligence can promote accessibility and inclusiveness in digital culinary environments. Centred on the Receitas +Power platform, the research adopts an exploratory, multidimensional case study design integrating qualitative and quantitative analyses. The investigation addresses three research questions concerning (i) user empowerment beyond recommendation systems, (ii) accessibility best practices across disability types, and (iii) the effectiveness of AI-enabled inclusive solutions. The system was developed following user-centred design principles and WCAG 2.2 standards, combining generative AI modules for recipe creation with accessibility features such as voice interaction and adaptive navigation. The evaluation, conducted with 87 participants, employed the System Usability Scale complemented by thematic qualitative feedback. Results indicate excellent usability (M = 80.6), high reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.798–0.849), and moderate positive correlations between usability and accessibility dimensions (r = 0.45–0.55). Participants highlighted the platform’s personalisation, clarity, and inclusivity, confirming that accessibility enhances rather than restricts user experience. The findings provide empirical evidence that AI-driven adaptability, when grounded in universal design principles, offers an effective and ethically sound pathway toward digital inclusion. Receitas +Power thus advances the field of inclusive digital gastronomy and presents a replicable framework for human–AI co-creation in accessible web technologies.

1. Introduction

Domestic cooking remains an integral aspect of contemporary lifestyles, although its frequency varies across cultural and socioeconomic contexts. The ongoing digitisation of gastronomic ecosystems has intensified the creation, experimentation, and sharing of recipes across digital platforms [1,2,3,4,5]. However, this transition has exposed persistent accessibility limitations that constrain the participation of users with diverse types of impairment.

Despite the wide availability of online culinary content, significant barriers continue to affect individuals with motor, visual, auditory, or cognitive disabilities. Recent global estimates indicate that approximately 1.3 billion people live with some form of disability, representing around 16 percent of the world population [6,7,8,9,10]. This situation underscores the relevance of developing inclusive digital solutions. Nonetheless, most culinary websites and mobile applications prioritise content sharing, recommendation mechanisms, and personalisation features, while accessibility requirements remain insufficiently addressed. As a result, only a limited number of platforms comply with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) established by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) [11,12,13]. This gap illustrates a consistent mismatch between existing technological provision and the practical needs of users with different accessibility profiles.

The literature indicates that digital accessibility, inclusive design, and personalisation are essential components for ensuring equitable user experiences in online environments. Prior studies examine food preferences, recommendation systems, and user customisation in culinary platforms, although these works rarely articulate such aspects with accessibility requirements or with the needs of users with disabilities [14,15,16]. Consequently, a clear research gap persists regarding how culinary platforms can effectively combine autonomous recipe creation, personalisation, and compliance with accessibility standards.

The Receitas +Power project was developed to address this gap. The platform integrates user-centred design principles and artificial intelligence components to support compliance with WCAG 2.2, improving perceivability, operability, understandability, and robustness [17,18]. Its web-based environment enables accessible recipe creation, visualisation, management, and sharing. This approach provides a scalable and replicable framework for inclusive user experience (UX) design within digital gastronomy.

The research was guided by the following questions:

- Q1: Do existing digital platforms enable users to create and customise their own culinary recipes beyond mere recommendation systems?

- Q2: What best practices and design principles ensure web accessibility across different disability types?

- Q3: Which digital solutions are most effective in ensuring accessibility and inclusiveness in culinary applications?

These questions delimit the research gap and support the study objectives, which aim to assess the limitations of current platforms and to propose an inclusive model informed by contemporary web development technologies and artificial intelligence.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the theoretical foundations related to digital accessibility, inclusive design, personalisation, and recommendation technologies. Section 3 presents the architecture and development process of the Receitas +Power platform. Section 4 outlines the research methodology and analytical procedures. Section 5 reports and discusses the empirical findings. Section 6 concludes the article with theoretical implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

Building on the digital gastronomy perspective, the intersection of artificial intelligence, digital accessibility, and personalisation has become increasingly relevant for contemporary food-related platforms as gastronomic practices migrate to online environments. In this context, AI-based systems have enabled advanced levels of personalisation, automation, and multimodal interactivity, fostering more intuitive and inclusive user experiences [11,12,19,20].

Digital gastronomy can be defined as a human-centred research and design territory that integrates computational technologies into culinary practice and food-related experiences, not merely to automate cooking, but to expand creativity, precision, and interaction across the full food pipeline. Recent accounts describe an evolution towards digital gastronomy 2.0, in which AI-enabled systems increasingly mediate culinary ideation, authoring, and experience design, alongside other technological trajectories such as robotic workflows and digital fabrication. Consequently, digital gastronomy spans both consumer-facing platforms and experimental culinary-tech systems, with a shared focus on how computation reshapes creation, communication, and participation in gastronomy [21,22,23].

Within this framing, AI supports digital gastronomy by enabling co-creation, adaptive guidance, and multimodal content generation that can increase user agency beyond passive recommendation. However, for digital gastronomy systems to be genuinely participatory at scale, accessibility must be treated as a first-order design requirement, given the procedural complexity and multimodality of recipes (text, images, step sequences, and interactive operations). Notably, while digital gastronomy 2.0 emphasises computational creativity and new interaction paradigms, standards-based accessibility is still inconsistently embedded in food-related digital systems; therefore, the present study positions accessibility-by-design as a complementary innovation driver within AI-enabled digital gastronomy [21].

The integration of recommendation algorithms, image recognition, and natural language generation has optimised nutritional analysis, dietary planning, and user engagement through dynamic, data-driven content. In food-related platforms, these techniques are commonly operationalised through recommender systems that suggest recipes, ingredients, or meal plans based on user preferences, dietary restrictions, or behavioural data [24,25]. These developments have broadened the scope of human–AI collaboration in food technology, allowing users to make more informed and personalised dietary choices.

Despite these advances, the dominant research and development focus in culinary platforms remains centred on efficiency, convenience, and personalization, while accessibility is frequently treated as a secondary or optional concern. Many culinary applications continue to prioritise convenience and personal customisation over universal accessibility, thereby excluding significant user groups, particularly those with disabilities [26]. This imbalance reflects a persistent gap between AI-centred innovation and inclusive digital design.

A comparative analysis of contemporary platforms such as Mealime [27], SideChef [28], BigOven [29], and Cookpad [30] reveals this limitation clearly. These systems provide comprehensive functionalities, recipe generation, ingredient management, and social interaction. However, accessibility-related features such as keyboard-only navigation, screen reader optimisation, alternative text for multimedia content, or adaptive presentation for cognitive accessibility are rarely implemented in a systematic manner. Few incorporate mechanisms such as voice control, screen reader optimisation, or adaptive visual contrast, which are essential for users with sensory, motor, or cognitive impairments. Consequently, while these platforms succeed in enhancing usability, they fall short of achieving full digital inclusiveness, indicating a continuing disparity between technological sophistication and accessibility integration. These platforms are referenced here as representative, widely adopted consumer-facing instances of digital gastronomy in practice; the associated website sources are used only to document publicly described features and interaction flows, whereas conceptual claims and research gaps are grounded in peer-reviewed literature.

Recent research has demonstrated that deep learning techniques have gained prominence in culinary informatics, encompassing areas such as ingredient recognition, recipe prediction, and automated meal planning [20,31,32]. Convolutional and transformer-based neural networks have achieved high accuracy in food classification and context-aware recommendation [19,20,32]. Nevertheless, these systems are predominantly evaluated according to predictive performance and recommendation accuracy, with limited consideration of accessibility, transparency, or user diversity as design criteria. Studies such as Pacífico et al. [32] represent preliminary attempts to address this deficiency by applying collaborative filtering to generate allergen-safe recipes, combining AI reasoning with inclusive content adaptation. However, such approaches remain the exception rather than the norm.

From an accessibility perspective, digital gastronomy platforms present specific challenges related to multimodal content, procedural complexity, and cognitive load. Recipes typically combine text, images, videos, and sequential instructions, which can pose significant barriers for users with visual, motor, or cognitive impairments if not designed according to accessibility standards. Web accessibility therefore constitutes a foundational requirement for inclusive participation in digital culinary environments.

Web accessibility forms the normative and regulatory foundation for inclusive digital development [33]. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 and 2.2, supported by ISO/IEC 40500:2012, ISO 9241-210:2019, and ISO 9241-11:2018, define four essential principles, perceivability, operability, understandability, and robustness, that underpin accessible design [13,34,35,36,37]. These principles are particularly relevant in food-related platforms, where users must be able to perceive ingredients and instructions, operate interfaces under diverse physical conditions, understand procedural steps, and rely on compatibility with assistive technologies.

Although accessibility standards have been successfully applied across sectors such as business software, educational platforms, and conversational agents [17,18,37,38], their systematic adoption in culinary and lifestyle-oriented applications remains limited. Accessibility research also exhibits a structural asymmetry, as visual impairments are disproportionately represented, whereas auditory, cognitive, and motor dimensions remain underexplored [34,37]. As Horton and Quesenbery [39] argue, accessibility must be embedded from the earliest stages of design rather than treated as a post-development corrective measure.

Personalisation and accessibility are frequently addressed as independent concerns in the literature, despite growing evidence that they can be mutually reinforced. Adaptive interfaces, simplified navigation paths, and user-controlled content generation can simultaneously support individual preferences and accessibility needs. Chemnad and Othman [17] emphasise that AI can facilitate automatic accessibility evaluation and dynamic content adaptation, enabling continuous compliance with evolving accessibility standards. Similarly, Manca et al. [18] and Vera-Amaro et al. [40] advocate for transparent, user-centred accessibility frameworks that leverage AI to detect and mitigate usability barriers in real time.

Within human–computer interaction (HCI), several authors argue that inclusive digital systems require iterative prototyping, mixed-methods evaluation, and participatory co-design to ensure responsiveness to the diverse needs of users [41,42,43]. In food-related contexts, this implies moving beyond passive recommendation toward systems that support active user participation, co-creation, and adaptive guidance. Such approaches align with emerging perspectives on human–AI co-creation, in which users retain agency and authorship while benefiting from computational assistance [44].

In this context, Receitas +Power emerges as a practical response to these conceptual and empirical gaps. The project operationalises the principles of universal design, inclusive interaction, and generative AI (GAI) within a single culinary web platform. Unlike existing applications, it treats accessibility not as an auxiliary function but as a fundamental design criterion. Through the integration of multimedia guidance, speech synthesis, and machine-generated recipe videos, it aims to provide equitable participation for users with diverse abilities.

By jointly addressing accessibility, personalisation, and AI-supported co-creation, Receitas +Power contributes to a more integrated understanding of digital gastronomy as a site of technological and social inclusion. This synthesis advances the literature by demonstrating how accessibility-aware AI systems can extend the scope of culinary platforms beyond recommendation, supporting autonomy, creativity, and inclusive user experience [11,25,38,44,45].

3. Development of the ‘Receitas +Power’ Platform

The Receitas +Power platform [46] was designed as an inclusive digital ecosystem that promotes culinary creativity while ensuring universal accessibility. Designed for users with diverse abilities, the platform enables the creation, visualisation, and sharing of recipes through an adaptive, AI-assisted interface.

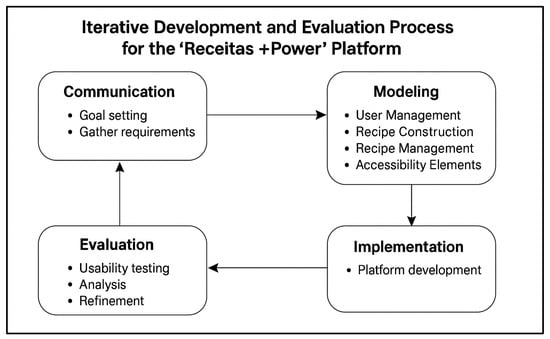

The software development methodology adopted was Prototyping [47,48], user-centred and accessibility-oriented, grounded in the WCAG 2.2 [13] guidelines and the principles of Human–Computer Interaction (HCI). Following the development phases of the methodology illustrated in Figure 1, the defined iterations were: (1) user management and authentication; (2) recipe creation and visualisation; (3) recipe storage and retrieval; and (4) integration of accessibility elements. Each iteration involved user testing and refinement cycles, ensuring that design decisions were guided by empirical feedback.

Figure 1.

Software methodology Prototyping.

3.1. Conceptual and Architectural Design

The conceptualisation and system architecture were guided by user-centred design principles [44] universal accessibility standards [49], and usability heuristics [50]. The goal was to build a platform capable of supporting independent recipe creation, editing, and sharing for all user profiles.

Accessibility was ensured through semantic HyperText Markup Language (HTML) 5 markup and Web Accessibility Initiative—Accessible Rich Internet Applications (WAI-ARIA) 1.2 attributes [51], guaranteeing compatibility with assistive technologies such as screen readers, voice navigation, and alternative input devices.

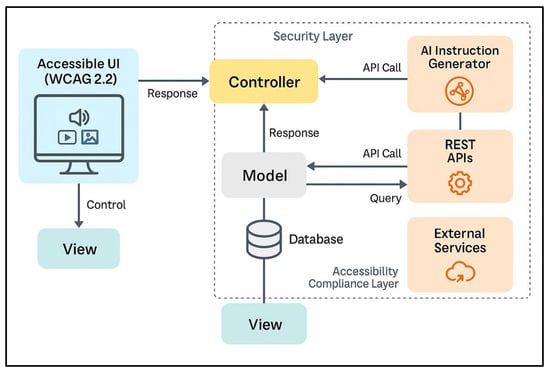

Figure 2 presents the platform’s conceptual architecture, which integrates AI modules within an accessible user interface (UI) and a compliant controller-model structure, unified under a security and accessibility validation layer.

Figure 2.

Accessible system architecture integrating AI and WCAG 2.2-compliant design.

3.2. System Architecture and Implementation

The platform’s information architecture balances simplicity and adaptability, maintaining cognitive clarity while supporting scalability. The database schema is built around four key entities, Recipe, Ingredient, Utensil, and Quantity, providing a normalised relational model for efficient data management and future AI integration [52].

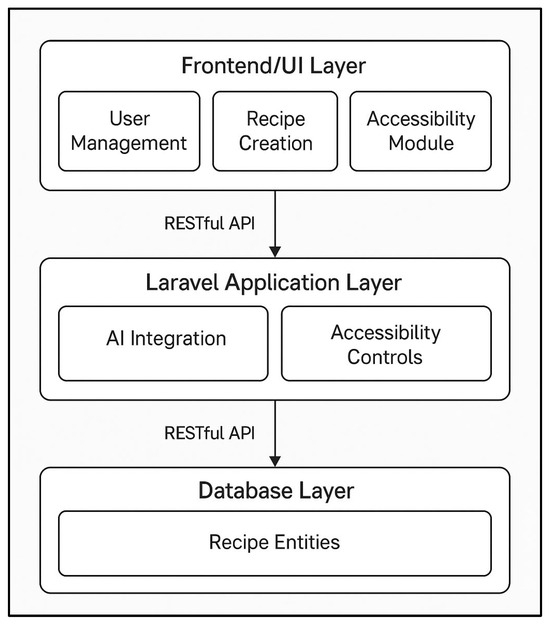

Figure 3 illustrates the modular Laravel-based layered architecture, composed of the Frontend/UI, Application, and Database layers connected through Representational State Transfer (RESTful) APIs [53]. This structure ensures maintainability, facilitates accessibility integration, and supports GAI functionalities.

Figure 3.

Modular system architecture of Receitas +Power.

3.3. Integration of Generative Artificial Intelligence and Accessibility Validation

A feature of Receitas +Power is its GAI module, which assists users in producing coherent, contextually accurate cooking instructions. Based on selected ingredients and utensils, the system automatically generates step-by-step recipes, reducing cognitive load and enhancing autonomy.

Several generative models were evaluated, including ChatGPT (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA, based on GPT-4o model) [54], Hugging Face (Hugging Face Inc., New York, NY, USA) [55], and DeepSeek (DeepSeek AI, China, employing the DeepSeek-V2 language model) [56] for text generation, and Stable Diffusion (Stability AI, London, UK, using Stable Diffusion XL and Stable Diffusion 3 models) [57] and Vidnoz (Vidnoz Ltd., Hong Kong, China) [58] for image and video synthesis. Due to computational and reliability constraints, the final implementation adopted the OpenRouter API (OpenRouter Inc., New York, NY, USA) [59] using the mistralai/mixtral-8X 7b-instruct model. This configuration provided a balance between linguistic coherence, scalability, and performance [42].

The system was implemented using the Laravel framework (v10.0, Laravel LLC, Taylor Otwell, Benton, AR, USA), chosen for its modularity, maintainability, and adherence to accessibility-oriented design. Its Model–View–Controller (MVC) architecture separated data handling, interface logic, and interaction management, ensuring clean code and scalability [60].

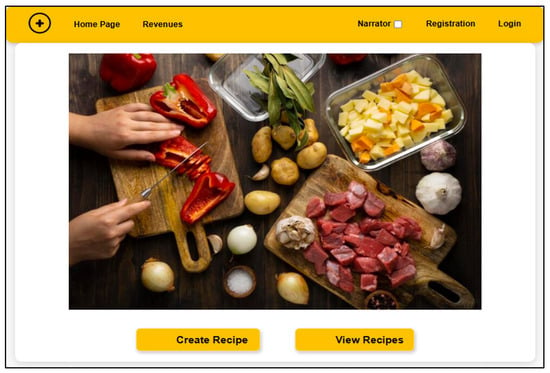

The frontend was designed to be visually appealing, responsive, and fully accessible, as illustrated by Figure 4. The main interface allows users to create and manage recipes intuitively, with consistent navigation, legible typography, and compliance with WCAG 2.2 Level AA.

Figure 4.

Accessible user interface of Receitas +Power, displaying navigation, recipe creation, and management options. All usability and accessibility tests were conducted on laptop computers running Windows 11 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) using Google Chrome (v120.0, Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA).

Security was ensured through Laravel’s built-in protocols for input validation, encryption, and role-based access control. The responsive layout guarantees accessibility across screen resolutions and device types, including smartphones, tablets, and desktop computers.

Usability testing constituted a core validation stage. A pilot group of 87 participants with diverse digital literacy and accessibility needs evaluated the platform across devices. Mixed observation and questionnaire methods were used to assess navigation ease, comprehension, satisfaction, and accessibility perception.

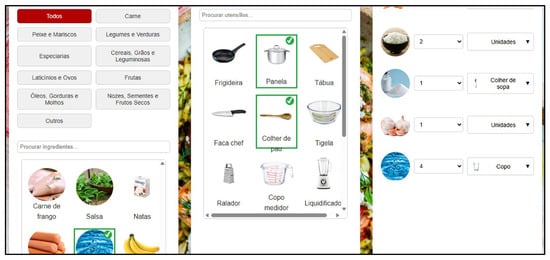

Figure 5 shows the inclusive ingredient and utensil selection interface, which allows users to choose components using visual and textual aids.

Figure 5.

Ingredient and utensil selection interface demonstrating accessible interaction design (labels shown in Portuguese). All usability and accessibility tests were conducted on laptop computers running Windows 11 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) using Google Chrome (v120.0, Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA).

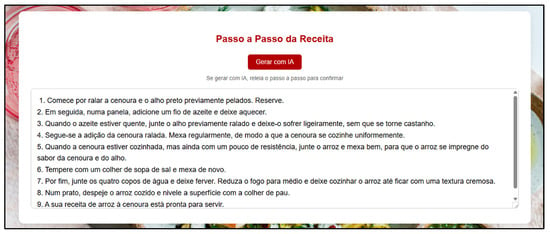

Once selections were finalised, the AI module generated procedural text and accessible formatting, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

AI-generated step-by-step recipe interface supporting text and auditory narration (labels shown in Portuguese). All usability and accessibility tests were conducted on laptop computers running Windows 11 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) using Google Chrome (v120.0, Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA).

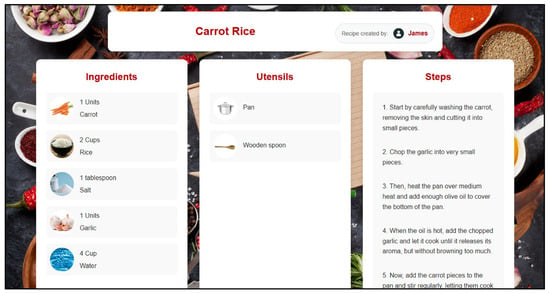

Figure 7 presents the final recipe visualisation view, combining ingredients, utensils, and sequential steps optimised for screen readers and compliant with WCAG 2.2 AA.

Figure 7.

Structured recipe visualisation interface optimised for assistive technologies. All usability and accessibility tests were conducted on laptop computers running Windows 11 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) using Google Chrome (v120.0, Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA).

Feedback-informed continuous refinements: font adjustments, enlarged buttons, optional narration, improved keyboard focus indicators, and enhanced colour contrast.

Accessibility validation was integrated across all development phases, using both automated and manual testing. The Web Accessibility Evaluation (WAVE) Tool (WebAIM, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA) [26] confirmed full WCAG 2.2 compliance, ensuring conformance to the four POUR principles: Perceivable, Operable, Understandable, and Robust [39,61].

Key accessibility features include full keyboard operability, descriptive alternative text, adjustable typography, focus indicators, and seamless compatibility with screen readers and speech input. These measures collectively ensured usability parity for all users.

3.4. Summary of Development Approach

The Receitas +Power project exemplifies how inclusive design, GAI, and scalable web technologies can converge to create a socially responsible and technologically advanced digital platform. By embedding accessibility as a structural design parameter, rather than as an afterthought, the platform demonstrates that innovation and inclusiveness are mutually reinforcing objectives.

This modular, AI-augmented, and standards-compliant framework offers a replicable model for inclusive digital transformation across other domains of human–technology interaction.

4. Methodology

This section details the methodological framework adopted to develop and evaluate the Receitas +Power platform. It outlines the research design, prototyping process, accessibility integration, participant recruitment, and data analysis procedures used to ensure methodological rigour and empirical validity.

4.1. Research Design

This study adopts an exploratory and multidimensional research design, structured as a case study centred on the Receitas +Power web platform. The approach combines qualitative and quantitative analyses to capture both the experiential and measurable aspects of accessibility and usability in AI-enhanced culinary systems. Given the project’s dual focus, technological development and inclusive user experience, the case study framework was considered the most appropriate for examining the interplay between design processes, user interaction, and accessibility outcomes [41,43,47].

Although the study follows a predominantly exploratory and qualitative orientation, complementary quantitative analyses were integrated to assess the reliability of the measurement instruments and to explore possible relationships among conceptual dimensions. This methodological pluralism aligns with current recommendations for mixed-methods research in HCI and accessibility studies [42,43].

The research design adopted in this study integrates two interdependent components, the iterative development of the platform and the empirical evaluation of its use. The exploratory case study approach was selected because it enables a contextualised and holistic examination of how accessibility principles and user-centred design practices can be operationalised within a concrete digital solution. This rationale is aligned with established methodological recommendations in Human–Computer Interaction [41,42] and accessibility research [17,33]. Within this framework, development and evaluation do not operate as parallel processes but constitute complementary stages of a continuous investigative cycle in which design decisions are informed by empirical evidence and refined through successive user testing. This multidimensional methodological structure supports an integrated examination of the three research questions, linking accessibility criteria (WCAG 2.2 [10]), design practices, and observable outcomes in real usage contexts.

The research data collected are methodologically aligned with the objectives of the study and the defined research questions. Quantitative data obtained through the System Usability Scale (SUS) and subsequent reliability and correlational analyses support the assessment of overall usability, satisfaction, and perceived inclusion. Complementarily, qualitative data derived from open-ended participant feedback enables an in-depth examination of user empowerment, accessibility perception, and interaction clarity. This mixed-methods approach ensures that both measurable outcomes and experiential dimensions are systematically addressed, thereby providing adequate empirical evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of AI-enabled accessible design within the scope of the study.

4.2. System Development and Prototyping

The development of Receitas +Power followed an iterative prototyping methodology, in line with agile user-centred design principles [41,47]. Each iteration included communication, rapid planning, modelling, construction, and user feedback. The technical implementation relied on PHP (v8.2, PHP Group, worldwide open-source community) [62], HTML5 (W3C Recommendation) [63], CSS3 (ECMAScript 2023) [64], and JavaScript (ECMAScript 2023) [65], supported by the XAMPP (v8.2, Apache Friends, Berlin, Germany) local server environment [66] and MySQL (v8.0, Oracle Corporation, Austin, TX, USA) database management system [67].

The prototyping process enabled progressive refinement of interface components, ensuring alignment between usability objectives and accessibility requirements. Early prototypes focused on user management and basic recipe creation, while later iterations incorporated multimedia elements (e.g., video instructions generated through AI) and accessibility features designed according to WCAG 2.2 and ISO 9241-210 standards [13,35,36].

Each prototyping iteration functioned simultaneously as a development step and as a mechanism for empirical data generation, consistent with iterative models widely applied in software and interaction design research [47,48]. Heuristic inspections, accessibility testing based on WCAG 2.2 and WAI-ARIA 1.2 guidelines [10,33], and participant feedback enabled the identification of barriers, adjustment of interface components, and validation of implemented accessibility solutions. This integrated process reinforces the investigative nature of the development phase, demonstrating that the platform evolved not only as a technological artefact but also as an empirical object capable of producing knowledge on accessibility, usability, and AI-assisted co-creation [17,18,44]. Consequently, the prototyping cycle contributed directly to answering the research questions by providing evidence that connects design decisions with user perceptions and interaction behaviours.

The alignment between the research questions, analytical variables, and data analysis procedures is summarised as follows.

Q1 (Personalisation) is addressed through variables related to perceived control, recipe co-creation, and adaptability, derived from specific questionnaire items and qualitative feedback.

Q2 (Accessibility) is examined through variables capturing perceived accessibility, clarity of interaction, and support for diverse functional profiles, grounded in WCAG 2.2-compliant design features and user evaluation.

Q3 (Inclusion and overall effectiveness) is analysed through global usability, satisfaction, and inclusion-related measures, integrating quantitative usability scores and qualitative perceptions.

This explicit mapping ensures coherence between the research objectives and the analytical strategy adopted in the study.

The first research question, concerning user empowerment and co-creation, is addressed through functional analysis during platform development and qualitative feedback, operationalised through variables related to perceived control, adaptability, and recipe cocreation, consistent with prior studies highlighting the role of AI in supporting creativity and authorship [40,44].

The second research question, focused on accessibility practices, is examined through the integration of WCAG 2.2 and WAI-ARIA 1.2 guidelines [10,13,34] in the design process and through evaluation involving participants with diverse functional profiles, using variables associated with perceived accessibility, interaction clarity, and support for different disability types, following international recommendations for accessibility studies [38,51].

The third research question, which investigates the effectiveness of inclusive digital solutions, is analysed through quantitative assessment using the SUS [52,60] and through reliability and correlational analyses applied to the dimensions corresponding to Q1–Q3.

These analytical procedures are appropriate to the exploratory nature of the study, as they allow the assessment of measurement consistency and the examination of associative relationships between variables without implying causal inference.

This synthesis strengthens the methodological coherence of the study by demonstrating that the different data sources contribute complementarily to an integrated understanding of the research problem.

4.3. Accessibility Integration

Accessibility was operationalised through the integration of W3C’s WCAG 2.2 guidelines and WAI-ARIA 1.2 specifications [13,34]. Design elements prioritised perceivability (clear contrast ratios and alternative text), operability (keyboard navigation and voice-assistant compatibility), understandability (simplified language and consistent layout), and robustness (cross-browser and assistive technology compatibility).

Automated evaluation tools such as WAVE [26] and manual heuristic inspections were employed to identify and address accessibility issues during development. The system architecture was informed by contemporary frameworks for AI-driven accessibility evaluation and content adaptation [14,15,17,18], ensuring compliance with both technical and ethical standards [50,51].

The alignment between the research questions and the methodological procedures is summarised as follows. The first research question, concerning user empowerment and co-creation, is addressed through functional analysis during platform development and qualitative feedback, consistent with prior studies highlighting the role of AI in supporting creativity and authorship [19,44]. The second research question, focused on accessibility practices, is examined through the integration of WCAG 2.2 and WAI-ARIA 1.2 guidelines [13,31] in the design process and through evaluation involving participants with diverse functional profiles, following international recommendations for accessibility studies [36,42]. The third research question, which investigates the effectiveness of inclusive digital solutions, is analysed through quantitative assessment using the SUS [49,57] and through internal consistency and correlational analyses exploring relationships among usability, satisfaction, and accessibility perception. This synthesis strengthens the methodological coherence of the study by demonstrating that the different data sources contribute complementarily to an integrated understanding of the research problem.

4.4. Evaluation Procedure and Participants

The empirical evaluation involved 87 participants recruited through voluntary online participation and community outreach via an open public call disseminated by educational institutions and Associação +Power. The recruitment text described the study objectives, the voluntary nature of participation, adult-only eligibility, an estimated duration of 10–15 min, and the anonymous and non-identifiable treatment of data. Participation consisted of autonomous exploration of the Receitas +Power platform followed by completion of an online questionnaire.

Eligibility criteria required participants to be at least 18 years old, able to use a computer or smartphone independently, and willing to provide informed consent. No financial or material compensation was offered, and no pre-screening questionnaire was administered. Participation therefore relied on informed self-selection, which is acknowledged as a limitation of this exploratory design [41,42].

The number of participants with self-reported disabilities reflects the exploratory nature of the study and the voluntary, non-stratified recruitment process. The inclusion of this subgroup aimed to ensure functional diversity and to validate accessibility-oriented design decisions, rather than to achieve statistical representativeness across disability types. Prior to accessing the questionnaire, all participants were presented with an informed consent statement outlining the study objectives, voluntary participation, the right to withdraw without penalty, exclusive use of data for scientific research, and aggregation of results, in accordance with established research ethics guidelines [50,51].

The evaluation combined quantitative and qualitative methods. Usability was assessed using the SUS [52,60], complemented by three open-ended questions addressing user experience: (i) what participants liked most about the platform, (ii) difficulties encountered during use, and (iii) suggestions for improving accessibility, usability, or functionalities. These qualitative questions supported the thematic analysis reported in Section 5.6 and provided contextualised insights into accessibility, visual clarity, and interaction flow, in line with mixed-methods recommendations for usability and accessibility research [41,42,43].

Participants interacted with the platform under autonomous conditions, using their own devices and assistive technologies when applicable. Core tasks included navigating recipes, creating or adapting content with AI support, and consulting culinary instructions. Accessibility features such as keyboard navigation, screen reader compatibility, and text-to-speech functionality were available. No critical accessibility barriers were identified, and reported difficulties were mainly associated with initial familiarisation with the AI-supported interaction flow.

4.5. Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics, reliability testing, and correlational analysis to assess internal consistency and interdimensional relationships among usability constructs, following established usability testing procedures [68]. The SUS was used to compute mean scores and standard deviations, while the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was applied to evaluate the internal consistency of subscales. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to examine associations between usability, satisfaction, and accessibility.

Qualitative responses were examined through thematic analysis, following a mixed inductive–deductive approach. Themes were coded manually, verified by two independent researchers, and cross-compared to ensure interpretive reliability. Integration of quantitative and qualitative findings followed a triangulation strategy, enabling cross-validation of usability metrics and user perceptions.

Internal consistency was assessed for each analytical dimension derived from the evaluation instrument. The three dimensions, Q1 (Personalisation), Q2 (Accessibility), and Q3 (Inclusion), presented satisfactory to high reliability, with Cronbach’s α values of 0.798, 0.821, and 0.849, respectively. Pearson correlation coefficients between dimensions ranged from 0.45 to 0.55, indicating moderate positive associations without conceptual redundancy.

4.6. Methodological Limitations

Consequently, the research design assumes an iterative and multidimensional structure that combines technical development, accessibility analysis, and empirical evaluation, enabling simultaneous examination of both the design process and its observed outcomes in real contexts of use. This approach consists of contemporary methodological proposals in accessibility research, which emphasise continuous evaluation, user participation, and progressive refinement of digital systems [17,18,36]. By making this integrative logic explicit, it becomes clear that the two components of the study, development and evaluation, jointly contribute to addressing the three research questions and to generating relevant knowledge on accessibility, generative AI, and digital inclusion.

As an exploratory case study, this research does not aim for statistical generalisation but rather for analytical insight into inclusive design practices. The participant sample, although diverse, was not probabilistically selected, and therefore caution should be exercised in extrapolating results. Nonetheless, the mixed-methods approach ensured both depth and reliability of analysis, making the findings relevant for subsequent empirical validation in larger and more heterogeneous populations.

Future studies should incorporate longitudinal tracking and behavioural analytics to observe sustained engagement with accessible interfaces over time. Additionally, comparative experiments across different AI models could further clarify the specific contribution of generative intelligence to accessibility outcomes.

5. Data Analysis and Results

This section presents the empirical findings derived from both quantitative and qualitative analyses. It summarises participant demographics, explores responses to each research question, and discusses the implications of the results for accessibility, usability, and AI-enabled inclusiveness.

Emphasis is placed on the interpretative integration of usability metrics, participant feedback, and the study objectives, to strengthen the analytical robustness of the findings.

5.1. Overview of Findings

The findings provide robust evidence that combining AI with accessibility standards can substantially enhance inclusiveness, usability, and user satisfaction in digital culinary environments. Quantitative and qualitative analyses collectively address the three research questions (Q1–Q3), examining user empowerment, accessibility practices, and the effectiveness of AI-enabled inclusive solutions.

Rather than treating these dimensions independently, the results reveal a consistent pattern in which perceived usability, accessibility support, and user empowerment mutually reinforce one another, thereby supporting the study’s overarching objective of evaluating inclusive, human-centred AI systems.

5.2. Participant Demographics and Digital Profiles

A total of 87 participants completed the usability and accessibility evaluation of Receitas +Power. As summarised in Table 1, the sample represented diverse age groups, balanced gender distribution, and varying levels of digital literacy. The inclusion of participants with visual, cognitive, and other functional limitations ensured that multiple accessibility perspectives were reflected in the dataset.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and digital profiles (n = 87).

Demographic diversity aligns with inclusive HCI research recommendations, strengthening the ecological validity of the analysis and ensuring that findings capture a wide range of user experiences [42,43].

This heterogeneity was particularly relevant for the qualitative analysis, as it enabled the identification of convergent themes across users with and without disabilities, as well as disability-specific accessibility priorities.

5.3. Q1: User Empowerment Beyond Recommendation Systems

Addressing Q1, participants consistently reported that Receitas +Power extended beyond traditional recommendation systems by allowing genuine recipe co-creation. Through AI-assisted ingredient recognition, allergen detection, and nutritional recalculation, users could modify or generate recipes dynamically.

Thematic analysis highlighted control, creativity, and flexibility as recurring descriptors, suggesting that participants experienced a sense of authorship rather than passive consumption. These results align with Bondevik et al. [19] and Starke et al. [24], who emphasise autonomy as a central motivator of engagement in culinary recommender systems. Consequently, Receitas +Power exemplifies human–AI co-creation by transforming recommendation algorithms into participatory creative tools [44].

Qualitative comments further clarify how empowerment was operationalised in practice. Participants frequently associated empowerment with the ability to make informed, personalised decisions, rather than merely receiving algorithmic suggestions. This perception directly addresses Q1 by demonstrating that empowerment emerged not only from functional system capabilities, but also from users’ subjective experience of control and agency during interaction.

5.4. Q2: Accessibility Design Across Disability Types

For Q2, the study investigated how accessibility guidelines could support diverse disability profiles. Automated evaluation using WAVE [26] and manual inspection confirmed compliance with WCAG 2.2 and WAI-ARIA 1.2 standards [13,34].

Participants with visual or motor impairments valued the system’s text-to-speech, voice command, and keyboard navigation features, while those with cognitive challenges highlighted the importance of clear structure, readable typography, and simplified textual content. These results reaffirm Horton and Quesenbery’s [39] assertion that accessibility must be designed proactively rather than retrofitted. They also support Miesenberger et al. [38], demonstrating that accessibility and usability reinforce one another when addressed holistically.

Importantly, qualitative feedback revealed that accessibility features were rarely perceived as auxiliary or compensatory. Instead, participants described them as integral to efficient interaction, regardless of disability status. This finding strengthens the response to Q2 by indicating that inclusive design decisions contributed to overall usability, rather than introducing barriers or trade-offs for non-disabled users.

5.5. Q3: Effectiveness of AI-Enabled Inclusive Solutions

The third research question assessed the overall usability, efficiency, and satisfaction with the platform. Quantitative analysis based on the SUS indicated consistently high ratings, as summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the SUS (n = 87) 1.

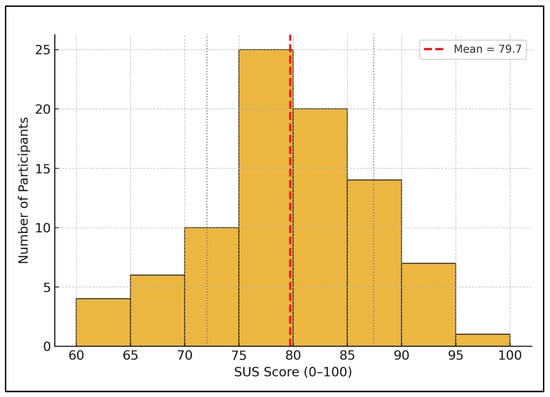

The distribution of scores is illustrated in Figure 8, which shows a clear clustering between 75 and 90, indicating that most participants evaluated the system as good to excellent.

Figure 8.

Distribution of SUS scores (n = 87).

To ensure internal consistency, Cronbach’s α and Pearson correlations were calculated for each construct, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Reliability and correlation coefficients for usability constructs 1.

A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted between all analytical dimensions considered in the study, namely Personalisation (Q1), Accessibility (Q2), and Inclusion (Q3). All bivariate relationships were positive and of moderate magnitude (r = 0.45–0.55), indicating associative links between the constructs without implying causal relationships.

The scale demonstrated good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α values ranging between 0.798 and 0.849. According to Tavakol and Dennick [69], α values above 0.70 are considered acceptable, while those between 0.80 and 0.90 indicate strong reliability without suggesting redundancy. Moderate positive correlations (r = 0.45–0.55) among usability, satisfaction, and accessibility constructs confirm that these variables are interrelated but non-redundant.

From an interpretative perspective, these quantitative results indicate that the perceived effectiveness of AI-enabled features cannot be dissociated from accessibility and satisfaction. The moderate correlations suggest that while each construct captures a distinct dimension of user experience, they jointly contribute to the overall evaluation of the platform, thereby directly addressing Q3.

5.6. Qualitative Insights

Although the open-ended questions focused explicitly on positive aspects, experienced difficulties, and suggestions for improvement, perceptions related to trust and reliability emerged transversally from participants’ reflections on clarity, consistency, and perceived usefulness of the AI-generated content.

Qualitative responses further complemented the quantitative findings, allowing a deeper interpretation of user experience. Four principal themes were identified, as summarised in Table 4. These themes extend beyond a descriptive classification, offering explanatory insight into how participants perceived and interpreted usability, accessibility, and empowerment during their interaction with the platform.

Table 4.

Thematic summary of qualitative responses (n = 87).

Personalisation and control emerged as the most prevalent theme, reinforcing findings related to Q1. Participants associated adaptive AI features with a sense of ownership over the cooking process, indicating that personalisation was perceived as an enabler of autonomy rather than as an opaque algorithmic intervention.

Accessibility and clarity were frequently linked to reduced cognitive and operational effort, particularly among participants with visual and cognitive impairments. These accounts complement the accessibility compliance results reported in Q2, illustrating how technical adherence to standards translated into meaningful interaction benefits.

Engagement and confidence were commonly mentioned in relation to independent task completion. Participants reported increased confidence in following and adapting recipes, which provides qualitative support for the high learnability and satisfaction scores observed in the SUS results.

Trust and reliability, although less frequent, were closely associated with the clarity of AI-generated suggestions and nutritional information. This theme offers qualitative context for the strong overall usability ratings, suggesting that trust played a mediating role in user acceptance of AI-driven features.

5.7. Synthesis and Implications

The quantitative and qualitative findings indicate that, within the scope of this exploratory case study, the Receitas +Power platform was associated with high perceived usability while integrating AI-based adaptability with established accessibility standards. Strong SUS scores, acceptable reliability indices, and consistent qualitative feedback support the design choices adopted in this specific context.

The analysis suggests that user empowerment (Q1), accessibility across disability profiles (Q2), and the perceived effectiveness of AI-enabled features (Q3) are interrelated within the observed usage setting, although these associations should be interpreted as context-dependent. Participants reported that AI-assisted functionalities supported perceptions of active engagement in recipe creation, extending beyond passive recommendation within the evaluated usage context, consistent with prior work on human–AI co-creation and perceived agency [19,44].

The implementation of WCAG 2.2 and WAI-ARIA 1.2 guidelines was reflected in positive accessibility perceptions among users with diverse functional profiles; however, this relationship should be interpreted as associative rather than causal, given the study design. In line with established accessibility literature, these features were experienced as integral to efficient interaction rather than as auxiliary adaptations [38,39].

Moderate positive correlations between usability, satisfaction, and accessibility perception indicate that these constructs contribute jointly to overall user experience while remaining analytically distinct, as reported in previous usability studies [42,61]. Overall, the implications of these findings are analytical and limited to the studied context, providing a basis for future validation in broader and more heterogeneous samples.

It should be emphasised that the observed relationships between usability, accessibility perception, and AI-enabled features reflect self-reported evaluations obtained from a non-probabilistic and context-specific sample. Consequently, the findings do not allow causal attribution between individual system components and user outcomes, nor do they support generalisation beyond similar exploratory settings.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Work

This study examined how artificial intelligence can support accessibility, inclusivity, and personalisation in digital culinary environments through an exploratory, multidimensional case study of the Receitas +Power platform. Three research questions were addressed, focusing on user empowerment beyond recommendation systems, accessibility across disability profiles, and the perceived effectiveness of AI-enabled inclusive solutions.

From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to the literature on digital consumers by extending existing models of technology use in consumption contexts to explicitly incorporate accessibility and inclusive design as constitutive, rather than peripheral, dimensions of user experience. The findings indicate that, within the evaluated context, Receitas +Power enabled users to create, customise, and adapt culinary recipes through AI-assisted functionalities, as perceived by participants during short-term interaction [19,44].

The integration of WCAG 2.2 and WAI-ARIA 1.2 guidelines contributed to positive accessibility perceptions among users with and without disabilities. These results align with established accessibility and human–computer interaction literature, which emphasises that accessibility and usability can be mutually reinforcing when embedded from the early stages of design [33,38,39].

Quantitative evaluation using the SUS indicated high perceived usability (M = 80.6), with acceptable to strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.798–0.849). Moderate positive correlations between usability, satisfaction, and accessibility perception (r = 0.45–0.55) suggest that these constructs are related while remaining analytically distinct. Similar interdependencies have been reported in previous usability and accessibility studies [42,52,61].

Several limitations should be explicitly acknowledged. First, as an exploratory case study based on a non-probabilistic and self-selected sample, the research does not support statistical generalisation or causal inference. The limited number of participants with self-reported disabilities further constrains the interpretation of accessibility outcomes across impairment types [41,45].

Second, the evaluation focused on perceived usability and accessibility rather than on objective performance metrics or long-term behavioural outcomes. The contribution of the specific generative AI model adopted cannot therefore be disentangled from the overall system design, limiting conclusions regarding the isolated impact of generative intelligence on accessibility.

Future research should therefore focus on larger and more diverse samples, longitudinal designs, and comparative evaluations across different application domains. Further work could also examine the specific contribution of different generative AI models to accessibility and usability outcomes, as suggested in recent accessibility and AI literature [17,18,40].

Overall, this study contributes to the consumer and human–computer interaction literature by providing empirical, context-specific evidence on how AI-supported accessibility and inclusive design can shape consumer experiences in digital gastronomy platforms. While the findings are limited to the examined case, they offer a foundation for further empirical validation and methodological refinement in the study of inclusive, AI-supported digital systems [38,44].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Â.O., F.F., L.B. and P.S.; methodology, Â.O., F.F. and P.S.; software, B.S. and T.I.; validation, Â.O., F.F., L.B. and P.S.; formal analysis, Â.O., F.F. and P.S.; investigation, Â.O.,B.S., F.F., P.S. and T.I.; resources, Â.O., B.S., F.F., P.S. and T.I.; data curation, P.S.; writing, Â.O., B.S., F.F., P.S. and T.I.; writing—review and editing, Â.O., F.F. and P.S.; supervision, Â.O., F.F., L.B. and P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by National Funds through the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), I.P., within the scope of the project UIDB/05583/2020 and DOI identifier https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/05583/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study in accordance with the national and institutional ethical guidelines for research in Social Sciences, specifically the provisions on proportional ethical safeguards for non-invasive research involving human participants (European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, Section 2.4). The study did not involve medical or biological research involving humans and concerned the usability and accessibility evaluation of a digital platform. All participants were adults, participated voluntarily, and were fully anonymous. No personally identifiable or sensitive data was collected. In line with the data protection and management principles set out in the same guidelines (Section 2.5) and in compliance with applicable regulations and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), ethics committee approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Research Centre in Digital Services (CISeD) and the Instituto Politécnico de Viseu for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AA | Accessibility Compliance Level |

| ACM | Association for Computing Machinery |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| ARIA | Accessible Rich Internet Applications |

| CSS | Cascading Style Sheets |

| GAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| HCI | Human–Computer Interaction |

| HTML | HyperText Markup Language |

| INE | Instituto Nacional de Estatística (Portugal) |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| MVC | Model–View–Controller |

| PC | Personal Computer |

| PHP | PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor |

| POUR | Perceivable, Operable, Understandable, Robust |

| RESTful API | Representational State Transfer (API architectural style) |

| SIGACCESS | ACM Special Interest Group on Accessible Computing |

| SUS | System Usability Scale |

| UI | User Interface |

| UX | User Experience |

| W3C | World Wide Web Consortium |

| WAI | Web Accessibility Initiative |

| WAI-ARIA | Web Accessibility Initiative—Accessible Rich Internet Applications |

| WCAG | Web Content Accessibility Guidelines |

References

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Survey on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC), 2010–2012; Instituto Nacional de Estatística: Lisbon, Portugal, 2013; p. 31.

- Virudachalam, S.; Long, J.A.; Harhay, M.O.; Polsky, D.E.; Feudtner, C. Prevalence and Patterns of Cooking Dinner at Home in the USA: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2008. Public. Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallup; Cookpad. Global Analysis of Cooking Around the World: A Report by Gallup & Cookpad; Gallup, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA; Cookpad Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 2023; pp. 1–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cooking Frequency in Germany. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367268785_Cooking_frequency_in_Germany (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Verduci, E.; Bronsky, J.; Embleton, N.; Gerasimidis, K.; Indrio, F.; Köglmeier, J.; De Koning, B.; Lapillonne, A.; Moltu, S.J.; Norsa, L.; et al. Role of Dietary Factors, Food Habits, and Lifestyle in Childhood Obesity Development: A Position Paper From the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021, 72, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Estatísticas Da Deficiência Em Portugal 2024 [Statistics on Disability in Portugal 2024]; Instituto Nacional de Estatística: Lisbon, Portugal, 2024.

- United Nations Factsheet on Persons with Disabilities|United Nations Enable. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/resources/factsheet-on-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Mitra, S.; Sambamoorthi, U. Disability Prevalence among Adults: Estimates for 54 Countries and Progress toward a Global Estimate. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakespeare, T.; Officer, A. World Report on Disability. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/world-report-on-disability (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Disability. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Starke, A.D.; Dierkes, J.; Lied, G.A.; Kasangu, G.A.B.; Trattner, C. Supporting Healthier Food Choices through AI-Tailored Advice: A Research Agenda. PEC Innov. 2025, 6, 100372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trattner, C.; Elsweiler, D. Investigating the Healthiness of Internet-Sourced Recipes Implications for Meal Planning and Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the 26th International World Wide Web Conference, WWW 2017, Geneva, Switzerland, 3 April 2017; pp. 489–498. [Google Scholar]

- Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0; World Wide Web Consortium (W3C): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Ara, J.; Sik-Lanyi, C.; Kelemen, A.; Guzsvinecz, T. An Inclusive Framework for Automated Web Content Accessibility Evaluation. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2024, 24, 1581–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoverde-Molina, M.; Luján-Mora, S. Artificial Intelligence in Web Accessibility: A Systematic Mapping Study. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2026, 96, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Amaro, G.; Rojano-Cáceres, J.R. Towards Accessible Website Design through Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Literature Review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2025, 186, 107821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemnad, K.; Othman, A. Digital Accessibility in the Era of Artificial Intelligence—Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review. Front. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 1349668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manca, M.; Palumbo, V.; Paternò, F.; Santoro, C. The Transparency of Automatic Web Accessibility Evaluation Tools: Design Criteria, State of the Art, and User Perception. ACM Trans. Access Comput. 2023, 16, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondevik, J.N.; Bennin, K.E.; Babur, Ö.; Ersch, C. A Systematic Review on Food Recommender Systems. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.B. Predict Food Recipe from Image Using CNN/Transformer & Knowledge Distillation for Portability. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Sensors, Electronics and Computer Engineering, ICSECE 2023, New York, NY, USA, 18 August 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 852–859. [Google Scholar]

- Zoran, A.R. Digital Gastronomy 2.0: A 15-Year Transformative Journey in Culinary-Tech Evolution and Interaction. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2025, 39, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, A.B.; Lachnish, A.Z.; Zoran, A.R. Digital Gastronomy Testcase: A Complete Pipeline of Robotic Induced Dish Variations. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 31, 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoran, A. Cooking With Computers: The Vision of Digital Gastronomy Point of View. Proc. IEEE 2019, 107, 1467–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starke, A.D.; Kløverød Brynestad, E.K.; Hauge, S.; Løkeland, L.S. Nudging Healthy Choices in Food Search through List Re-Ranking. In Proceedings of the UMAP 2021—Adjunct Publication of the 29th ACM Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, New York, NY, USA, 21 June 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, K.; Goktas, P.; Kumar, N.; Leung, M.F. Artificial Intelligence in Personalized Nutrition and Food Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Review of Methods, Applications, and Future Directions. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1636980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WAVE Web Accessibility Evaluation Tools. Available online: https://wave.webaim.org/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Mealime-Meal Planning App for Healthy Eating—Get It for Free Today! Available online: https://www.mealime.com/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- SideChef: Shop and Cook Step-by-Step Recipes. Available online: https://www.sidechef.com/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- BigOven 500,000+ Recipes, Meal Planner and Grocery List|BigOven. Available online: https://www.bigoven.com/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Guarda, Publica e Partilha Receitas Com Cozinheiros Caseiros Em Todo o Mundo—Cookpad. Available online: https://cookpad.com/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Morol, M.K.; Rokon, M.S.J.; Hasan, I.B.; Saif, A.M.; Khan, R.H.; Das, S.S. Food Recipe Recommendation Based on Ingredients Detection Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, New York, NY, USA, 10 March 2022; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Pacifico, L.D.S.; Britto, L.F.S.; Ludermir, T.B. Ingredient Substitute Recommendation Based on Collaborative Filtering and Recipe Context for Automatic Allergy-Safe Recipe Generation. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, New York, NY, USA, 5 November 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, S.L. Understanding Web Accessibility. In Constructing Accessible Web Sites; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 6–31. [Google Scholar]

- Accessible Rich Internet Applications (WAI-ARIA) 1.2. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/wai-aria-1.2/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- ISO/IEC 40500:2012; Information Technology—W3C Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- ISO 9241-210:2019; Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part 210: Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77520.html (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- ISO 9241-11:2018; Ergonomics of Human–System Interaction—Usability: Definitions and Concepts. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Miesenberger, K.; Kouroupetroglou, G.; Mavrou, K.; Manduchi, R.; Covarrubias Rodriguez, M.; Penáz, P. (Eds.) Correction to: Computers Helping People with Special Needs; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13341, ISBN 978-3-031-08647-2. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, S.; Quesenbery, W.; Gustafson, A. A Web for Everyone: Designing Accessible User Experiences; Rosenfeld Media: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781933820972. [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Amaro, G.; Rojano-Cáceres, J.R. Understanding Accessibility Needs of Blind Authors on CMS-Based Websites. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2025, 23, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix, A.; Finlay, J.; Abowd, G.; Beale, R. Human–Computer Interaction, 3rd ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-13-046109-7. [Google Scholar]

- Barnum, C.M. Usability Testing Essentials: Ready, Set…Test! 2nd ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-12-816942-6. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, P.; Pereira, B.; Figueiredo, G.; Aguiar, C.; Silva, C.; Oliveira, H.; Rosário, P. An Iterative Mixed-Method Study to Assess the Usability and Feasibility Perception of CANVAS® as a Platform to Deliver Interventions for Children. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 8057–8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.; De Cremer, D.; Van de Cruys, T. Establishing the Importance of Co-Creation and Self-Efficacy in Creative Collaboration with Artificial Intelligence. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.; Fu, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, K.; Sun, X.; Xu, T.; Chen, E. A Survey on Multimodal Large Language Models. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2024, 11, nwae403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Receitas Para Vegetarianos. Available online: https://receitas.maispower.pt/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Arnowitz, J.; Arent, M.; Berger, N. Effective Prototyping for Software Makers; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 9780120885688. [Google Scholar]

- Preece, J.; Sharp, H.; Rogers, Y. Interaction Design: Beyond Human-Computer Interaction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Otwell, T. Laravel Framework Documentation; Laravel LLC: Chicago, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Drenth, P.J.D. The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. In Promoting Research Integrity in a Global Environment; Steneck, N.H., Mayer, T., Eds.; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2011; pp. 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- ACM. SIGACCESS Research Ethics Guidelines for Accessibility Studies; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bangor, A.; Kortum, P.T.; Miller, J.T. An Empirical Evaluation of the System Usability Scale. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2008, 24, 574–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REST API—Ready to Use. Available online: https://restful-api.dev/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- ChatGPT. Available online: https://chatgpt.com/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- HuggingFace the AI Community Building the Future. Available online: https://huggingface.co/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- DeepSeek. Available online: https://www.deepseek.com/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Professional AI Image Generation with Precision|Diffus. Available online: https://www.diffus.me/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Vidnoz AI Tools: Create FREE Engaging AI Videos 10X Faster. Available online: https://www.vidnoz.com/?a_aid=65893b93b3725&gad_source=1 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- OpenRouter. Available online: https://openrouter.ai/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Brooke, J. SUS: A ‘Quick and Dirty’ Usability Scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Jordan, P.W., Thomas, B., McClelland, I.L., Weerdmeester, B.A., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1996; pp. 189–194. ISBN 978-0-7484-0504-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sauro, J.; Lewis, J.R. Quantifying the User Experience; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780123849687. [Google Scholar]

- PHP. Available online: https://www.php.net/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Community, W. HTML Standard. Available online: https://html.spec.whatwg.org/#the-canvas-element (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Wilson, K. Cascading Style Sheets. Available online: https://www.w3.org/Style/CSS/Overview.en.html (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- JavaScript|MDN. Available online: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Apache Friends Download XAMPP. Available online: https://www.apachefriends.org/es/download.html (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- MySQL. Available online: https://www.mysql.com/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Shaw, D. Handbook of Usability Testing: How to Plan, Design, and Conduct Effective Tests; Wiley Publishing: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1996; Volume 47, ISBN 978-0-470-18548-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.