Abstract

Background: We present our experience of carrying out endovascular therapy (EVT) of a pseudo-aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery (PTA) with an associated arteriovenous fistula (AVF). We also present results of a systematic review which was carried out to cast light on endovascular treatment modalities. Methods: A 31-year-old patient with a history of war trauma presented with pain of increasing severity in the lower leg. A CT angiogram confirmed an aneurysm of the PTA with an AVF. With a bidirectional endovascular approach, the aneurysm was occluded with coils and excluded with a Viabahn endoprosthesis. Aspirin and clopidogrel were recommended postoperatively. After 18 months of follow-up, the patient was free of symptoms, with patent endoprosthesis. Multiple databases (Scopus, Pubmed, Medline, OVID) were systematically searched using MeSH terms. The studies were scrutinized, and data on demographics, procedural details, and follow-up were collected and aggregated. Results: A total of 44 studies (56 patients) were eligible and were included. Average age was 50 (15–87 years). The most common etiology was trauma (iatrogenic 29/56 (51.7%); non-iatrogenic 15/56 (26.7%)). EVT strategies included coil embolization (n = 29), stent implantation (n = 25), and a combination of both (n = 2). Median stent diameter was 3 mm (2.5–6). The follow-up period ranged from 1 week to 60 months. Aggregated reported primary patency was 18/27 (66.6%) with no documented complications—an observation that likely reflects reporting and publication bias, rather than a true absence of adverse events. Conclusions: EVT offers a feasible and safe alternative to simple ligation or occlusion of crural aneurysms, to preserve distal flow to the foot. Dedicated stents for crural arteries are not available. Studies with long-term follow-up are lacking.

1. Introduction

Aneurysms of the crural arteries are rare entities. The current literature reports a diverse etiology, with trauma being the most common inciting factor [1]. Trauma can be iatrogenic, e.g., following orthopedic surgery [2,3], following vascular interventions such as balloon angioplasty or embolectomy [4], or after blunt [5] or penetrating non-iatrogenic trauma [6]. These aneurysms have also been reported in patients with connective tissue disorders like panarteritis nodosa [7], Ehlers–Danlos syndrome [8], and Behcet’s disease [9] who have no history of trauma. Infected mycotic aneurysms in patients with endocarditis have also been reported [10,11].

The characteristic symptomatology of crural aneurysms is pain, swelling, and/or a pulsatile mass in the lower leg [11,12]. Rarely, neurological symptoms such as paresthesia or foot drop caused by nerve compression [13], or rupture of the aneurysm with or without compartment syndrome [14,15], can be the presenting feature. In a few cases, the course of crural aneurysms is completely asymptomatic, and diagnosis appears to be incidental [16,17].

The spectrum of treatment modalities encompasses conservative management, open surgical treatment [17], minimally invasive treatment with thrombin injection, and endovascular treatment [18]. EVT includes coiling of the aneurysm and/or the feeding vessel to occlude the aneurysm [19,20,21,22]. Alternatively, exclusion of the aneurysm with a stent graft offers the opportunity to preserve blood flow distal to the aneurysm [23,24,25,26].

Apart from reporting our experience with EVT of an aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery (PTA), the aim of this study was to systematically summarize the current literature regarding EVT of crural aneurysms, focusing on the type of EVT, stent characteristics, patency, and reintervention rates.

2. Materials and Methods

Case Report

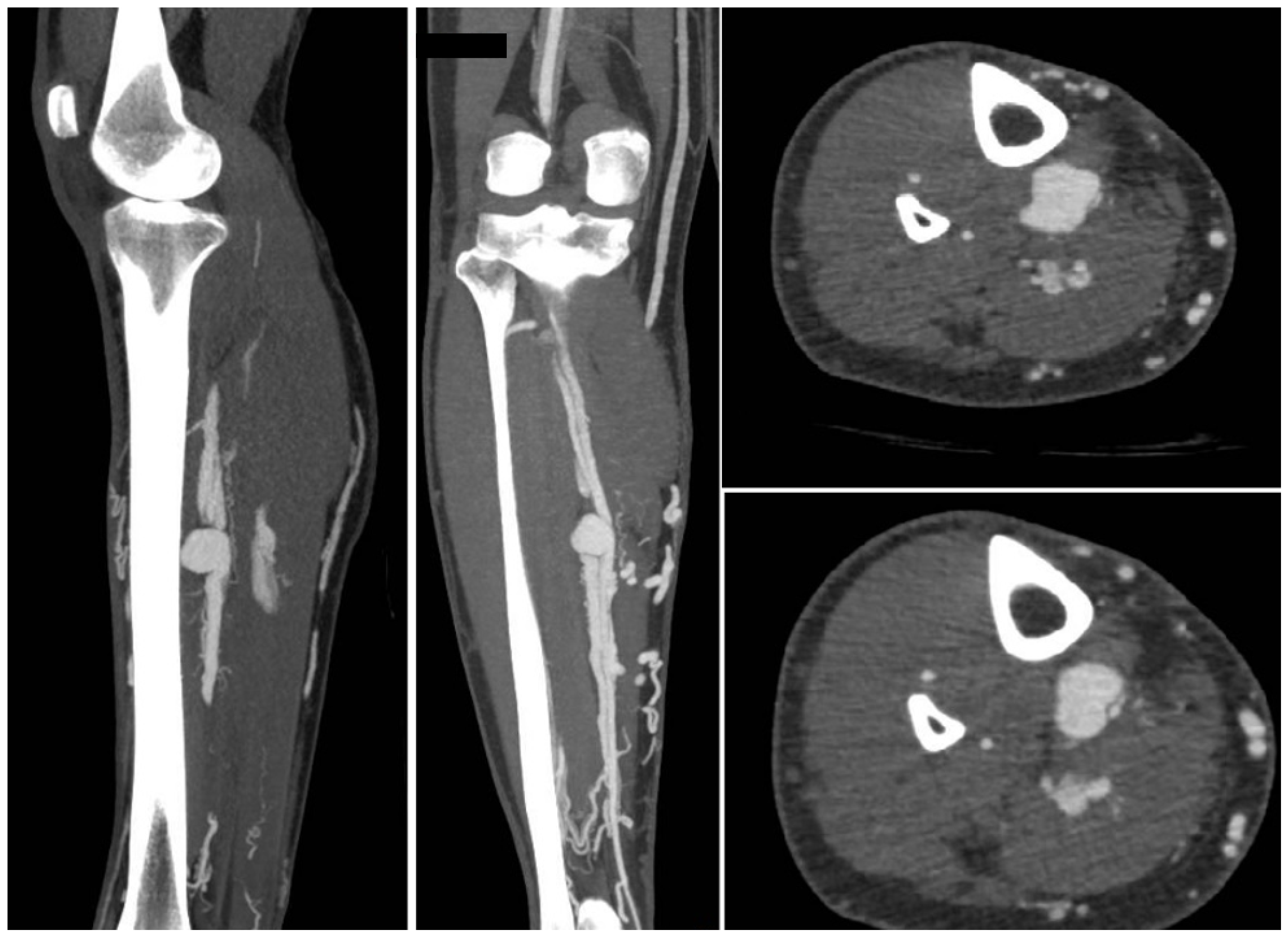

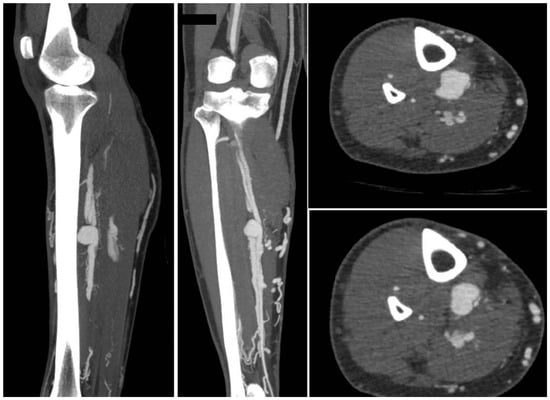

A 31-year-old man presented with calf pain in the right limb which had gradually increased in severity over the previous few months. The pain was throbbing in nature and was not associated with walking. There was a history of war injury to his lower leg in the region of the pain. The patient reported being hit by bomb shrapnel in the lower leg region. Physical examination revealed a pulsatile, tender mass in the mid-calf region. Duplex ultrasound revealed an aneurysm in the mid-calf region of the posterior tibial artery. To define the morphology of the aneurysm and the anatomy of the crural vessels, a CT angiogram was obtained. This confirmed the presence of an aneurysm of the PTA associated with an AV fistula to the deep posterior tibial veins (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The CT angiogram shows the aneurysm of the posterior tibial artery with AV fistula (contrast uptake by the deep and the superficial veins).

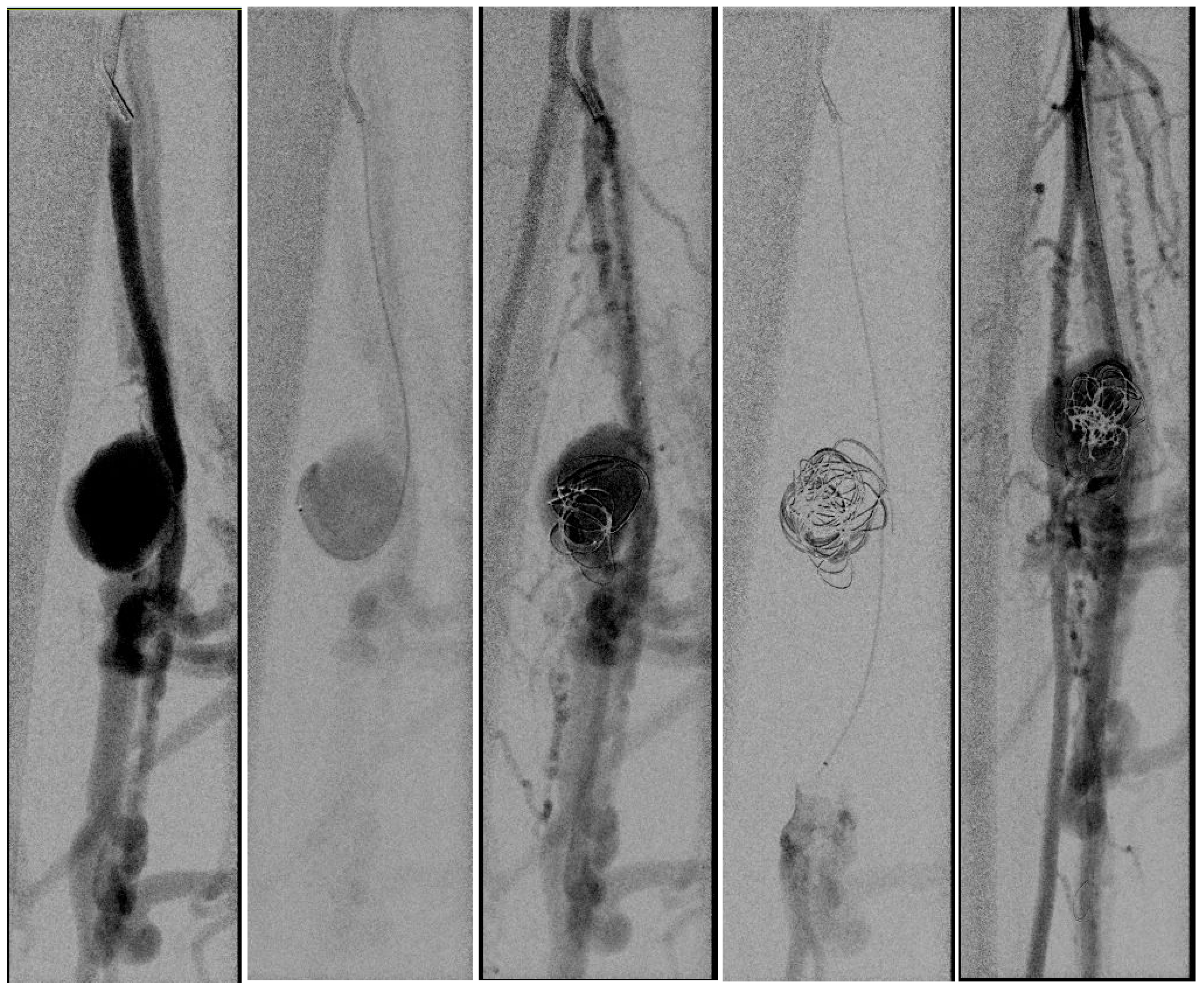

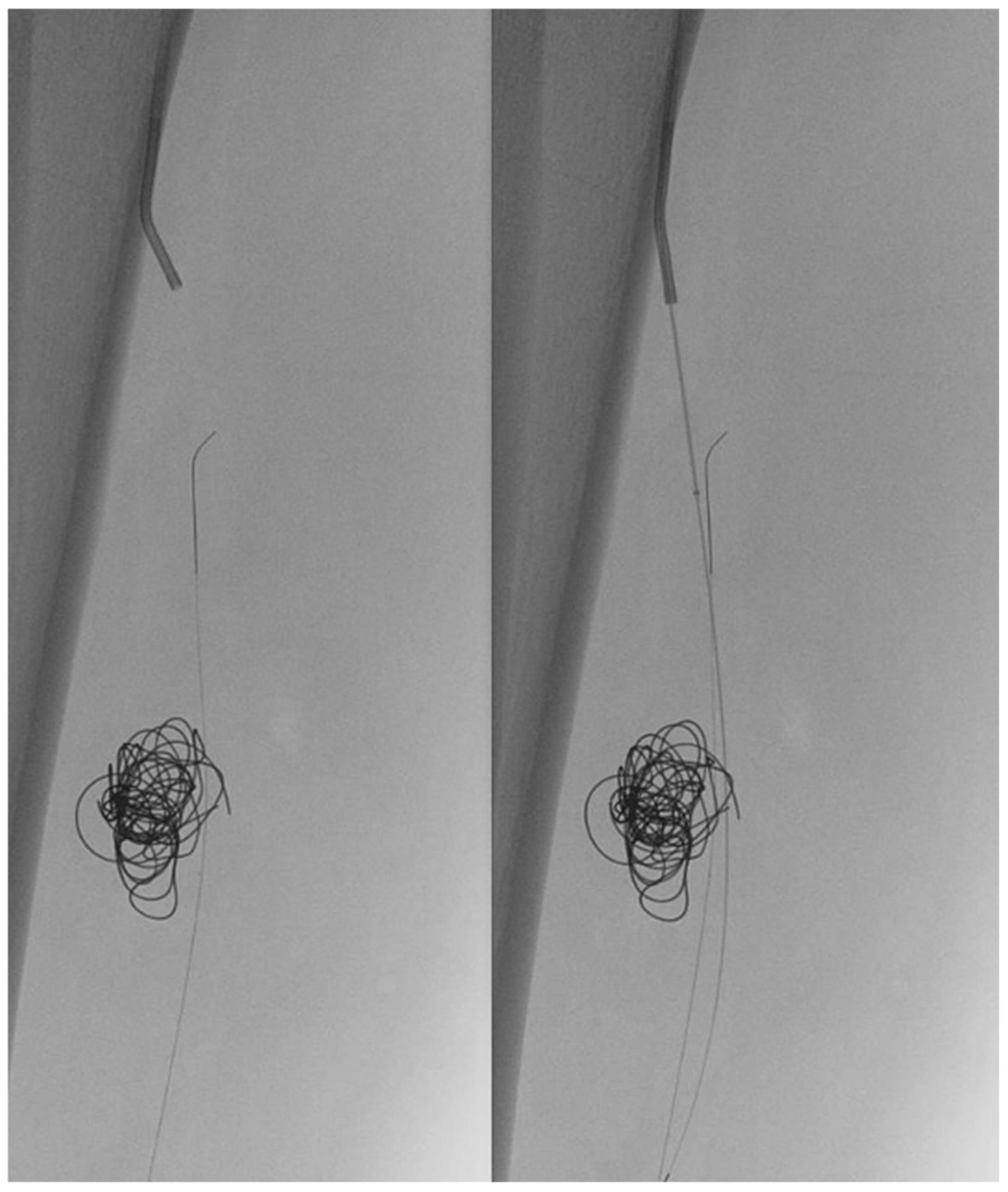

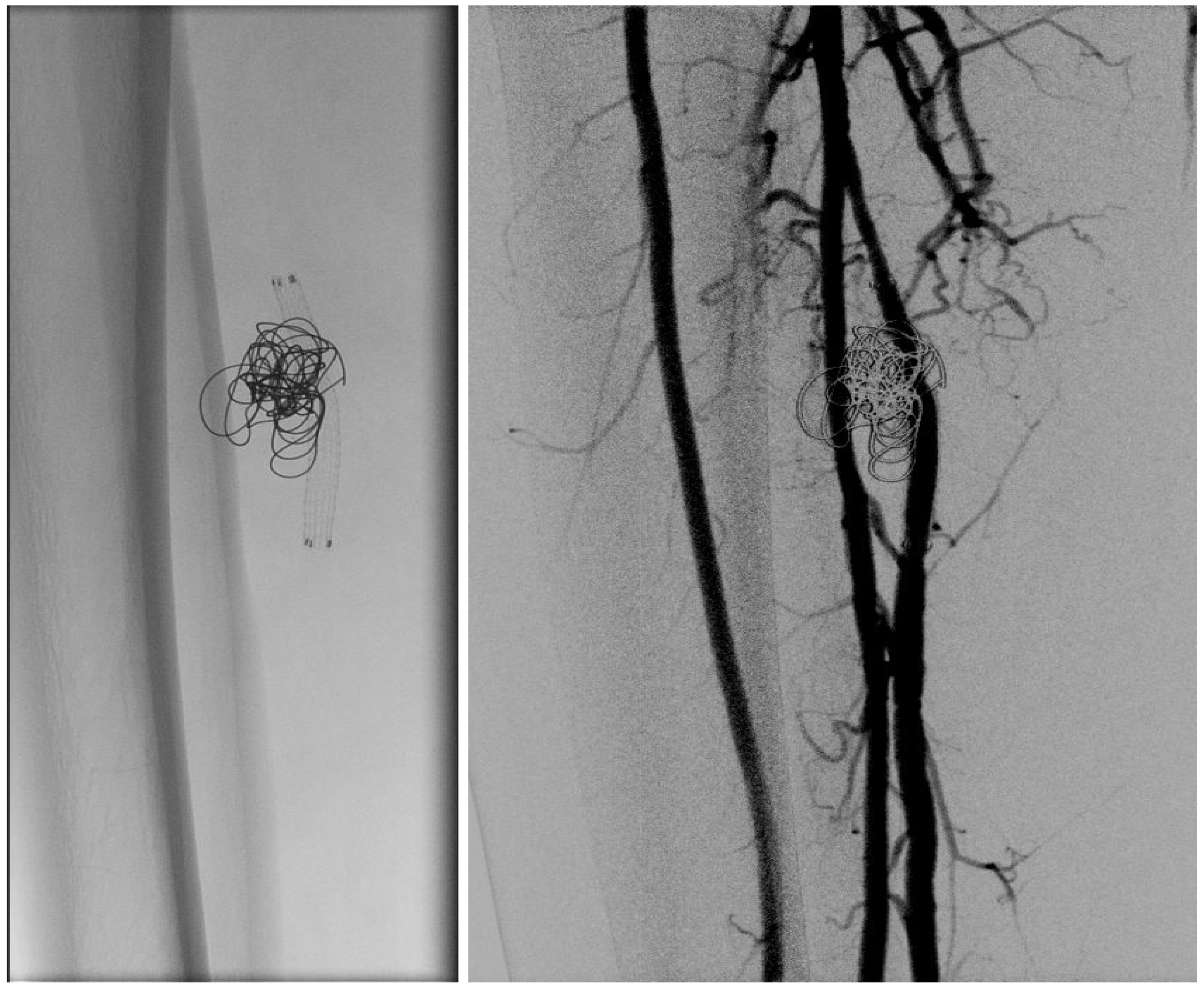

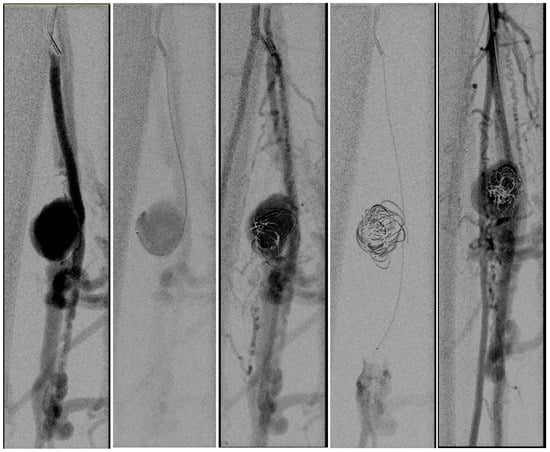

In light of a symptomatic aneurysm, treatment was offered to the patient. After discussing the risks of open and endovascular treatment options with the patient, an endovascular approach was opted for. The presence of a large aneurysm with an AV fistula and venous congestion posed an increased risk of significant bleeding complications associated with open surgery. An antegrade femoral access was obtained via a 5F sheath (Terumo, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, Japan). After obtaining an angiogram, two coils were deployed in the aneurysm sac (Concerto PGLA helical PV-20-50-Helix and Concerto PGLA 3D PV-18-40-3D, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), with the aim of causing sac thrombosis and obliterating the flows from multiple AV fistulas. As anticipated, this did not lead to complete occlusion of the aneurysm and AV fistula. A retrograde pedal access was obtained, and cannulation of the PTA was successfully performed with a V14 guidewire (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) (Figure 2 and Figure 3). After obtaining guidewire access, the aneurysm was excluded with a stent graft (Viabahn Endoprosthesis 5 mm × 50 mm, WL Gore, Flagstaff, AZ, USA). Immediately after the procedure, angiography control visualized complete exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm, occlusion of the sac, and absence of any AVF (Figure 4). Postoperatively, the patient reported pain reduction. Both pedal pulses were palpable. Postoperative antithrombotic therapy included aspirin 100 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg daily for 6 months. Additionally, Class 2 compression stockings were recommended for 1 month. After 18 months of follow-up, the patient was free of symptoms, and the stent graft was patent.

Figure 2.

(Left) to (right). An angiogram was obtained, and the aneurysm sack was coiled. Multiple attempts to cannulate the distal posterior tibial artery failed (A microcatheter is in the crural vein). After coiling the aneurysm sack, the AV fistula was still patent.

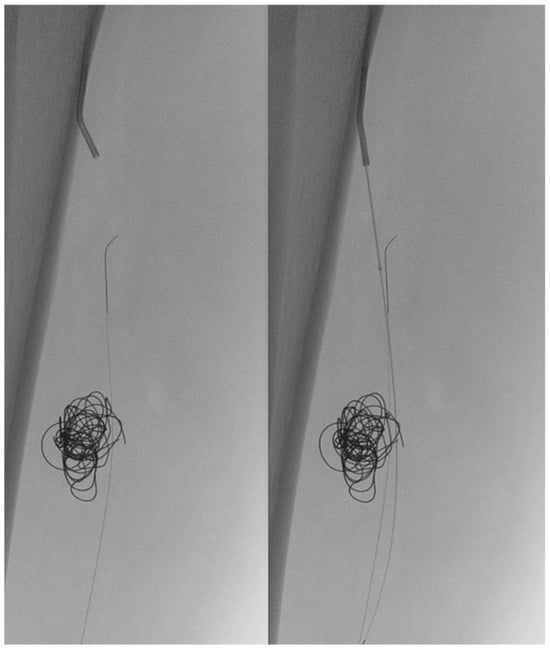

Figure 3.

(Left) to (right). Retrograde pedal access was obtained and cannulation was successful with a V14 Guidewire.

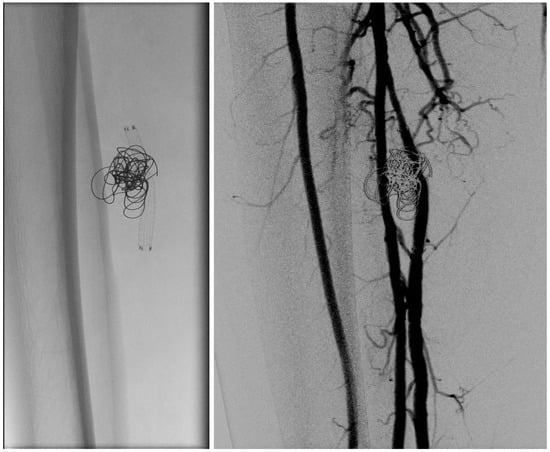

Figure 4.

(Left) to (right). Coils and Viabahn stent graft. Post-stenting angiogram showing excluded aneurysm and fully deployed Viabahn.

3. Systematic Review

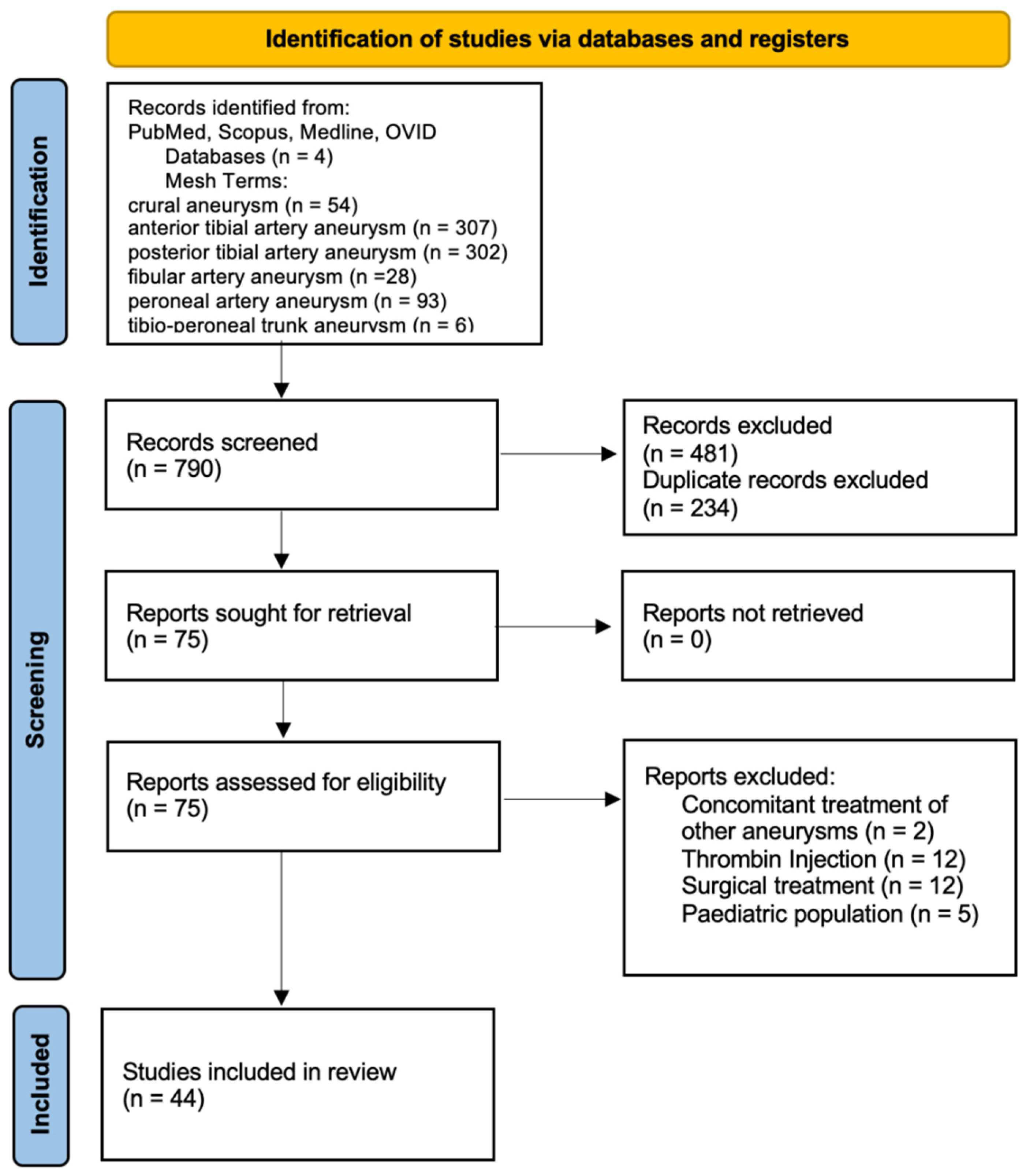

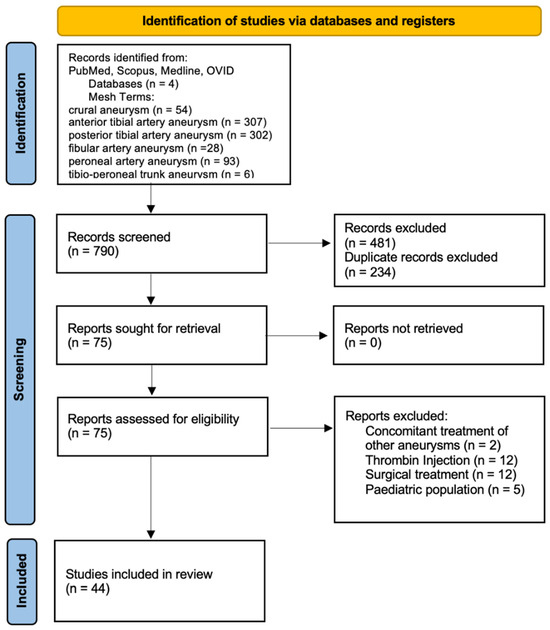

A multiple-database search (Scopus, PubMed, Medline, OVID) was carried out, in accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidelines, for studies published between January 2000 and January 2024 (Figure 5) [27]. MeSH terms with and without Boolean operators were used for the search strategy. These were ‘crural aneurysm’, ‘anterior tibial artery AND aneurysm’, ‘posterior tibial artery AND aneurysm’, ‘peroneal artery AND aneurysm’, and ‘tibio-peroneal trunk AND aneurysm’. Only human studies published in English were included. The studies were assessed, and data on demographics, procedural details, and follow-up were collected and aggregated independently by two reviewers. Case series, trials, and retrospective studies of EVT of aneurysms were included. Concomitant treatment of aneurysms other than crural aneurysms; patients treated conservatively, surgically or with thrombin; and patients < 15 years were excluded from the study. A formal risk of bias/quality assessment using the CARE (Case Report) Guidelines revealed substantial heterogeneity among the included case reports. Data on long-term follow-up and outcomes—particularly regarding patency, procedure-related complications, and re-interventions—were frequently lacking. Owing to this heterogeneity, the present review should be interpreted as a descriptive analysis rather than a meta-analysis.

Figure 5.

Flow diagram of systematic review including searched databases and study selection.

4. Results

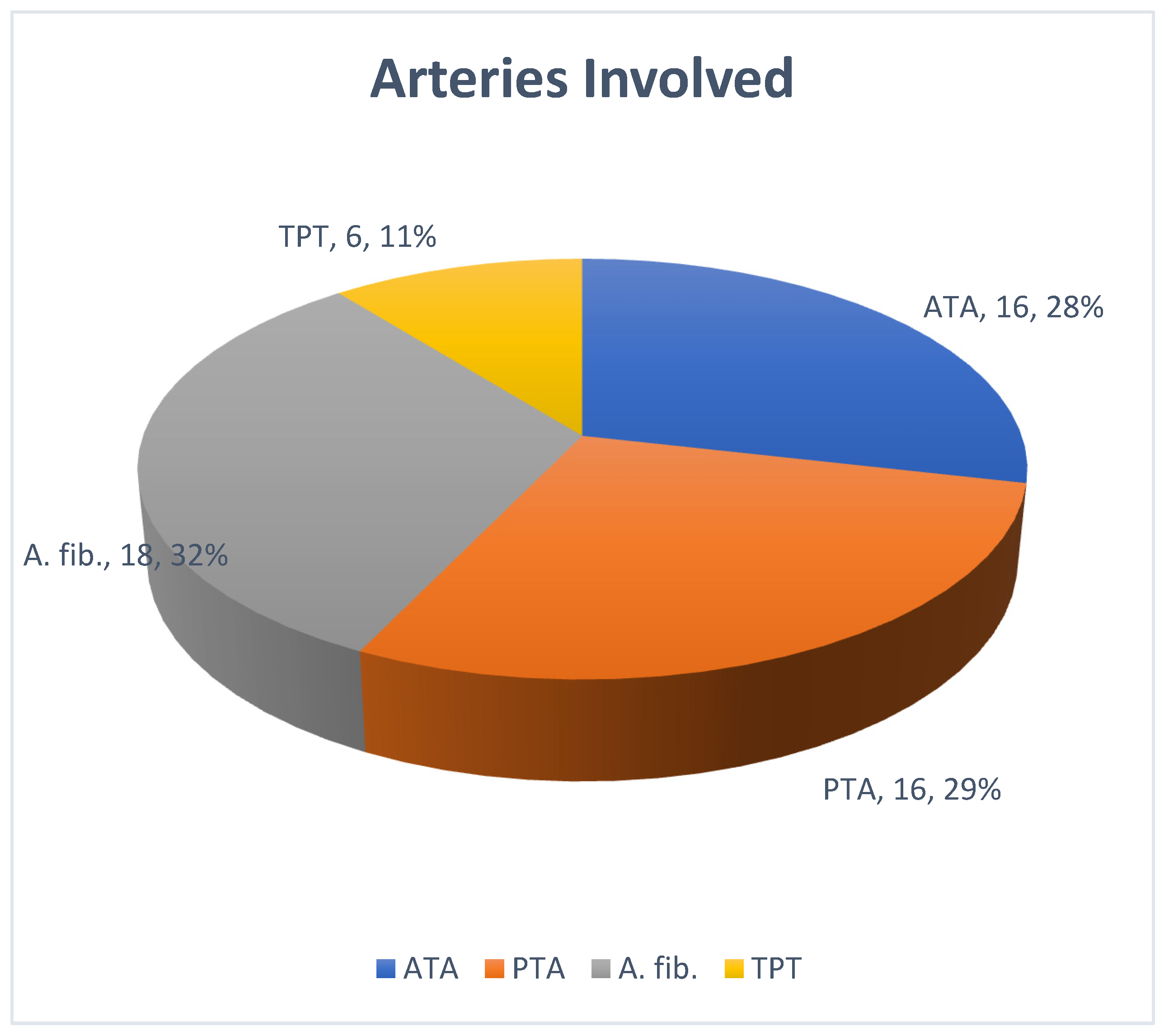

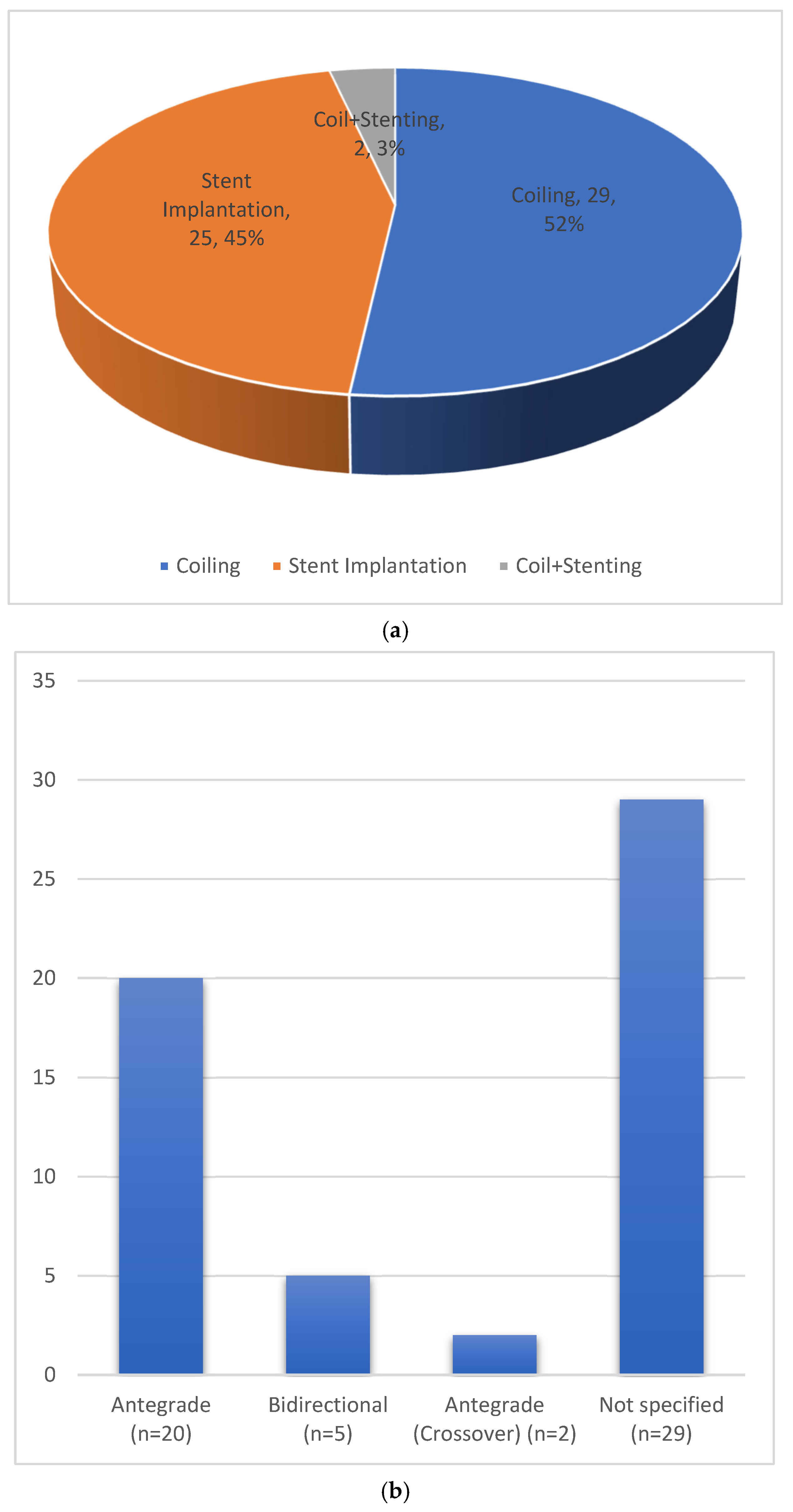

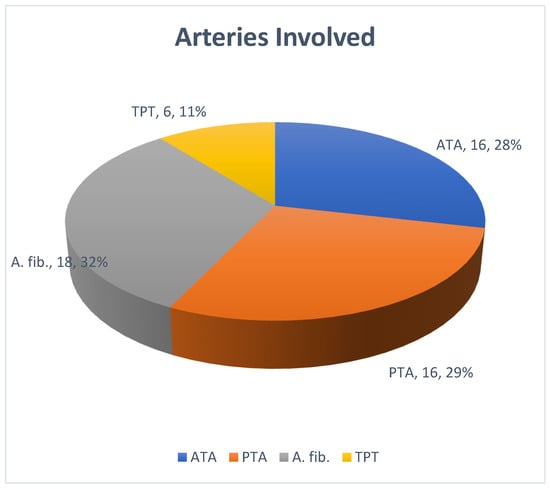

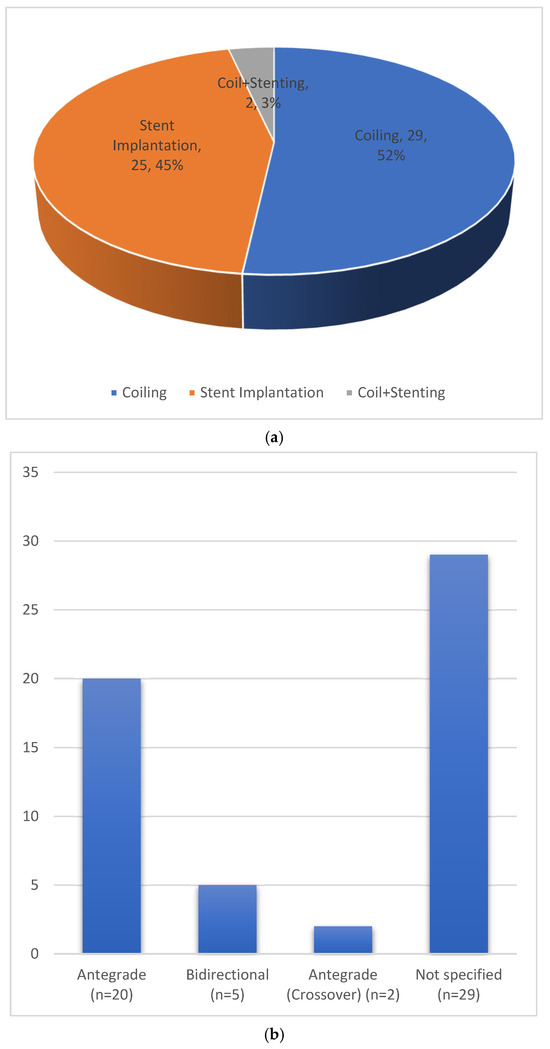

A total of 790 records were identified (Figure 5). After initial screening of titles and abstracts, and removal of duplicates, a total of 75 studies were sought for retrieval. A total of 44 studies were eligible to be included in the current review [1,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,14,16,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. These included forty-three case reports and one case series, and involved a total of 56 treated patients/limbs (Table 1). The average age of patients was 50 years (range 15–87). The peroneal artery was the most frequently affected crural vessel (Figure 6). The most common etiology was iatrogenic trauma (29/56 (51.7%)), followed by outside-hospital trauma (15/56 (26.7%)), connective tissue disorders like Behcet’s disease and Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (6/56 (10.7%)), mycotic (1/56 (1.7%)), and idiopathic (5/56 (8.9%)). Types of endovascular procedure and access method are depicted in Figure 7a,b. Various stents and stent grafts were used for endovascular exclusion of crural aneurysms. The most commonly used type of stent graft was balloon-expandable, followed by self-expanding (Table 2). The median stent diameter was 3 mm (range 2.5–6 mm), and the Graftmaster™ RX Coronary Stent Graft (Abbott, Chicago, IL, USA) was the most commonly used stent graft system. The average follow-up was 9.5 months (1 week to 60 months). Eighteen of twenty-seven (18/27) patients had patent stents at follow-up, with an aggregated reported primary patency proportion of 66.6%. No studies reported any reinterventions or complications.

Table 1.

Details of investigators, years of study, age and sex of patients, etiology, and localization of aneurysms. Anterior tibial artery (ATA), posterior tibial artery (PTA), peroneal artery (A. fib.), tibioperoneal trunk (TPT), Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), syndrome (sy.), not mentioned (NM).

Figure 6.

Involvement of arteries in the aggregated data of patients from the studies included in the review. Anterior tibial artery (ATA), posterior tibial artery (PTA), peroneal artery (A. fib.), tibioperoneal trunk (TPT).

Figure 7.

(a) Endovascular treatment strategies chosen for treatment of crural aneurysms in the studies included in the review. (b) Choice of access for the endovascular treatment strategy chosen for treatment of crural aneurysms in the studies included in the review.

Table 2.

Studies using stents or stent grafts for exclusion of the crural aneurysms, with size, type, and number of stents deployed, and their patency at the end of follow-up.

5. Discussion

Aneurysms of the crural arteries are rare entities whose incidence is unknown. As encountered in the case presented in this study, the association of these aneurysms with an AV fistula to the deep veins is even rarer. An associated AV fistula was found in 5/56 (8.9%) patients in the current review. All of these patients had a history of trauma. Two of these were treated with coil occlusion [12,30] of the pseudoaneurysm and the affected vessel, and three were treated with stent graft implantation [31,47,49]. In our case, we started the procedure with an antegrade approach and coil occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm. This was to cause thrombosis of the aneurysm and prevent flow in the aneurysm from the multiple venous fistula tracts. Because the following angiogram demonstrated persistent but reduced contrast uptake by the aneurysm and associated deep veins, we decided to proceed with stent graft implantation. The rationale for this was to seal the inflow to the aneurysm, preserve the vessel and its distal outflow, and avoid coiling of the whole vessel. This approach contrasts with the findings of the current review, where the most common treatment strategy was found to be coil occlusion of the aneurysm and the vessel (52%). A prerequisite of this approach is the presence of distal flow to the foot through the non-affected arteries. Stent grafts, on the other hand, offer an opportunity to preserve distal blood flow in the affected artery. A combination of both coiling and stent graft implantation is rarely described (3% in the current review).

The natural history of these aneurysms is unknown, and size does not seem to play a role, either in symptomatology or as a causative factor for complications. Madison et al. describe a case with a 7–9 mm aneurysm of the anterior tibial artery associated with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, with acute onset of calf pain, massive tenderness, and impending rupture. Similarly, Parry et al. describe a case of a pseudoaneurysm of the posterior tibial artery presenting as acute arterial hemorrhage from a chronic venous ulcer in a patient with deep-vein thrombosis and post-thrombotic syndrome. Singh et al. [12] and Nwilati et al. [15] describe urgent repair of a ruptured crural pseudoaneurysm with local compartment syndrome. Case studies including Spronk et al. [52] describe a risk of distal embolization and blue toe syndrome as initial presentation. The rarity of this entity makes it difficult to give recommendations regarding diameter cut-off values to guide treatment. Analogous to popliteal artery aneurysms, we recommend treating symptomatic crural aneurysms on an urgent basis. Asymptomatic aneurysms without any signs of compression can be followed up regularly. Because rupture rates in patients with connective tissue disorders are high, these patients can be monitored closely [15].

Various treatment strategies have been described in the literature. A recent publication concerning the treatment of 38 patients with peripheral artery pseudoaneurysms (traumatic and/or iatrogenic) compared three modalities (open repair, endovascular approach, and ultrasound-guided thrombin injection). Open repair was associated with higher amounts of blood loss requiring more blood transfusion, significantly longer operative times, and longer hospital stays [53]. A large aneurysm with an AV fistula, as in the described cases, carries a potential risk of profuse hemorrhage with open reconstruction. In our case, the size of the defect in the artery and the number of AV fistula connections could not be determined preoperatively. Additionally, due to the potential severe trauma associated with exploration during open reconstruction, we opted for an endovascular approach. An open approach appears feasible for aneurysms that have a small defect and where delineation of the AV fistula tract is possible. The options include patch reconstruction of the defect or a venous interposition graft [53].

The current literature review also provides information regarding the types and sizes of stents that are being used worldwide for this indication. The rare nature of this clinical entity explains the absence of dedicated stents and the lack of consensus on which stent can or should be used in the crural arteries for aneurysm exclusion. The most commonly used stent was a balloon-expandable stent (coronary stent, Graftmaster from Abbott). The aggregated data showed that the median diameter of the stents used was 3 mm. We used a self-expanding stent graft (Viabahn 5 mm diameter, WL Gore, Flagstaff, AZ, USA), which one might think would be large for crural vessels. However, in this young patient, the vessels had a diameter of 4 mm, as measured in the preoperative CT angiogram. The literature review revealed one more study group who used a 5 mm Viabahn to exclude a crural aneurysm without any complications and with a patent stent at 12 months of follow-up [11]. Surprisingly, Yamamoto et al. reported the use of a self-expanding bare-metal stent (Innova, Boston Scientific) as a barrier to trap coils in the aneurysm sac to cause sac thrombosis [19]. A recent study reported the use of a flow-diverter pipeline embolization device (PED) with a diameter of 3.5 mm for crural aneurysm exclusion [48]. These devices are used for the exclusion of intracranial aneurysms or dissections.

The average follow-up of the aggregated patients was 9.5 months (one week to sixty months). Eighteen of twenty-seven (18/27) patients had patent stents at follow-up, with an aggregated reported primary patency proportion of 66.6%. In the reported case, after 18 months of follow-up, the patient was free of symptoms, and the endoprosthesis was patent. This review highlights a key limitation of the available literature: long-term follow-up data, including information on reinterventions and secondary patency rates, are largely missing. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. The apparent absence of reported complications or reinterventions in the aggregated case reports likely reflects reporting and publication bias, and is influenced by the predominance of case reports and small case series, short and inconsistent follow-up durations (mean follow-up of 9.5 months), a lack of standardized surveillance protocols, and selective reporting of successful outcomes. Collectively, these factors substantially limit conclusions regarding the safety and durability of the reported interventions.

6. Conclusions

The endovascular approach to crural aneurysms offers an additional management modality with the advantages of low blood loss and early ambulation. The disadvantages include the necessity of postoperative antithrombotic therapy, along with insufficient data regarding its duration. Moreover, long-term results regarding stent patency are lacking. The absence of re-interventions or post-procedural complications in this review likely reflects reporting and publication bias. Open repair is associated with higher amounts of blood loss requiring more blood transfusion, significantly longer operative times, and longer hospital stays [53]. The superiority of any one modality over the others cannot be determined on the basis of the currently available literature. However, the endovascular approach offers an additional tool in the armory of a vascular surgeon for flow preservation, and it is indeed a feasible alternative to open ligation or coil occlusion of the affected vessels.

Author Contributions

Conceiving and designing the study, A.S., R.S., M.F., S.K., and F.A.; collecting the data: A.S. and R.S.; analyzing and interpretating the data, A.S., R.S., M.F., S.K., and F.A.; writing the manuscript, A.S., R.S., and F.A.; critical revisions of the article, A.S., R.S., M.F., S.K., and F.A.; final approval of the article, A.S., R.S., M.F., S.K., and F.A.; overall responsibility, A.S., R.S., M.F., S.K., and F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics committee approval and the approval of institutional review board was not required for this study, as it consists of a single case report and a systematic review of previously published data.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available on request. Patient data can be provided on a pseudo-anonymous basis if needed, due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sadat, U.; See, T.; Cousins, C.; Hayes, P.; Gaunt, M. Peroneal artery pseudoaneurysm—A case report and literature review. BMC Surg. 2007, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, J.F.; Cheng, J.C.; Lung, T.K.; Chan, M. Pseudoaneurysm after high tibial osteotomy and limb lengthening. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1998, 354, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.J.; Won, Y.Y.; Khang, S.Y. Pseudoaneurysm after tibial nailing. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2004, 418, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehlert, W.H. A complication of the Fogarty arterial embolectomy catheter. Am. Heart J. 1972, 84, 484–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrencik, M.T.; Caraballo, B.; Yokemick, J.; Pappas, P.J.; Lal, B.K.; Nagarsheth, K. Infrapopliteal Arterial Pseudoaneurysm Development Secondary to Blunt Trauma: Case Series and Literature Review. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020, 54, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoro, M.; Baldassarre, V.; Sirignano, P.; Mansour, W.; Capoccia, L.; Speziale, F. Endovascular Treatment of an Anterior Tibial Artery Pseudoaneurysm Secondary to Penetrating Trauma in a Young Patient: Case Report and Literature Review. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 60, 479.e5–479.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maga, P.; Batko, B.; Kaczmarczyk, P.; Krawiec, P.; Krzanowski, M. Unusual presentation of polyarteritis nodosa with unilateral pseudoaneurysm of the posterior tibial artery. Pol. Arch. Med. 2015, 125, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagspiel, K.D.; Bonatti, H.; Sabri, S.; Arslan, B.; Harthun, N.L. Metachronous bilateral posterior tibial artery aneurysms in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2011, 34, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, J.V.; Gallardo Pedrajas, F.; Cao González, I.; Segura Iglesias, R.J. Urgent endovascular treatment of a ruptured tibioperoneal pseudoaneurysm in Behçet’s disease. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 25, 385.e11–385.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, E.; Ferri, M.; Carbonatto, P.; Viazzo, A.; Robaldo, A.; Calvo, A.; Pecchio, A.; Berardi, G.; Piazza, S.; Cumbo, P.; et al. Endovascular treatment of a symptomatic mycotic aneurysm of the peroneal artery. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 25, 982.e11–982.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenick, N.; Cho, J.S.; Abu Hamad, G.; Makaroun, M.S.; Chaer, R.A. Endovascular repair of multiple infrageniculate aneurysms in a patient with vascular type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 54, 848–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Singh, D.; Ferero, A. Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the posterior tibial artery treated by endovascular coil embolization. Foot Ankle Spec. 2013, 6, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kars, H.Z.; Topaktas, S.; Dogan, K. Aneurysmal peroneal nerve compression. Neurosurgery 1992, 30, 930–931. [Google Scholar]

- Madison, M.K.; Wang, S.K.; King, J.R.; Motaganahalli, R.L.; Sawchuk, A.P. Urgent Endovascular Repair of an Anterior Tibial Artery Aneurysm: Case Report and Literature Review. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020, 54, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwilati, A.E.; AlQedra, D.; Shafiei, M.; AlSaleh, F.M. True anterior tibial artery aneurysm with rupture and compartment syndrome. J. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 70, e198–e199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, S.; Shimogawara, T.; Yamazoe, S.; Matsui, J. Successful endovascular isolation of a huge true anterior tibial artery aneurysm by the bi-directional approach in a young patient. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 95, E175–E178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musio, D.; Perfumo, M.C.; Gazzola, V.; Pane, B.; Spinella, G.; Palombo, D. A true giant aneurysm of the anterior tibial artery. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 29, 1319.e5–1319.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratl, A.; Klocker, J.; Glodny, B.; Wick, M.; Fraedrich, G. Treatment options of crural pseudoaneurysms. Vasa 2014, 43, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Uchiyama, H.; Oonuki, M. Endovascular coil embolization of a large tibioperoneal trunk pseudoaneurysm. J. Vasc. Surg. Cases Innov. Tech. 2020, 6, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micari, A.; Vadalà, G. Tibioperoneal trunk pseudoaneurysm coil embolization. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2010, 75, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, T.; Soga, Y.; Nobuyoshi, M. Iatrogenic peroneal artery pseudoaneurysm treated by transluminal coil embolization. Cardiovasc. Interv. Ther. 2013, 28, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okugi, S.; Watanabe, K. Endovascular Embolisation for Proximal Anterior Tibial Artery Aneurysm. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2021, 61, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Troia, A.; Biasi, L.; Iazzolino, L.; Azzarone, M.; Tecchio, T.; Rossi, C.; Salcuni, P. Endovascular stent grafting of a posterior tibial artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to penetrating trauma: Case report and review of the literature. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 28, 1789.e13–1789.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golledge, J.; Velu, R.; Quigley, F. Use of a covered stent to treat two large false aneurysms of the anterior tibial artery. J. Vasc. Surg. 2008, 47, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joglar, F.; Kabutey, N.K.; Maree, A.; Farber, A. The role of stent grafts in the management of traumatic tibial artery pseudoaneurysms: Case report and review of the literature. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2010, 44, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Roo, R.A.; Steenvoorde, P.; Schuttevaer, H.M.; Outer, A.J.D.; Oskam, J.; Joosten, P.P.H. Exclusion of a crural pseudoaneurysm with a PTFE-covered stent-graft. J. Endovasc. Ther. 2004, 11, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, D.; Parikh, A.; Robertson, I.; Kessel, D.; Scott, D. Arterial haemorrhage from a chronic venous ulcer-pseudoaneurysm formation of the posterior tibial artery. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2000, 20, 489–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebrang, A.; Grga, A.; Brkljacic, B.; Drinkovic, I. Successful closure of large pseudoaneurysm of peroneal artery using transluminal temporary occlusion of the neck with the catheter. Eur. Radiol. 2001, 11, 1206–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, P.; O’DOnnell, S.D.; Goff, J.M.; Gillespie, D.L.; Starnes, M.B. Endovascular management of a peroneal artery injury due to a military fragment wound. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2003, 17, 678–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spirito, R.; Trabattoni, P.; Pompilio, G.; Zoli, S.; Agrifoglio, M.; Biglioli, P. Endovascular treatment of a post-traumatic tibial pseudoaneurysm and arteriovenous fistula: Case report and review of the literature. J. Vasc. Surg. 2007, 45, 1076–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hensbroek, P.B.; Ponsen, K.J.; A Reekers, J.; Goslings, J.C. Endovascular treatment of anterior tibial artery pseudoaneurysm following locking compression plating of the tibia. J. Orthop. Trauma 2007, 21, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbano, B.; Gigante, A.; Zaccaria, A.; Polidori, L.; Martina, P.; Schioppa, A.; Ferrazza, A.; Lanciotti, K.; Cianci, R. True posterior tibial artery aneurysm in a young patient: Surgical or endovascular treatment? BMJ Case Rep. 2009, 2009, bcr0420091812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Seymour, R.; Hockings, M. Endovascular coil embolization of pseudoaneurysm of a branch of the anterior tibial artery following total knee replacement. J. Knee Surg. 2009, 22, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goltz, J.P.; Bastürk, P.; Hoppe, H.; Triller, J.; Kickuth, R. Emergency and elective implantation of covered stent systems in iatrogenic arterial injuries. Rofo 2011, 183, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, E.; Groot, D.; Das, M.; Hermus, J.P. Pseudoaneurysm of the anterior tibial artery after ankle arthroscopy. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2011, 50, 361–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Bodhey, N.K.; Gupta, A.K.; Bele, K. Coil migration through skin after posterior tibial artery pseudoaneurysm trapping. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2011, 34, S315–S317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, E.; Ferri, M.; Carbonatto, P.; Robaldo, A.; Viazzo, A.; Calvo, A.; Berardi, G.; Pecchio, A.; Piazza, S.; Cumbo, P.; et al. Symptomatic aneurysm of a perforating peroneal artery after a blunt trauma. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2012, 26, 277.e1–277.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, F.; Mani, G.; Martini, G.; Zipponi, D. Endovascular exclusion coupled with operative anterior leg compartment decompression in a case of postthromboembolectomy tibialis anterior false aneurysm. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 27, 973.e1–973.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopal, A.; Aranson, N.; Woo, K.; Clavijo, L.; Shavelle, D.M. Recalcitrant peroneal artery pseudoaneurysm in a patient with Hemophilia B. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2013, 14, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, F.; Salerno, C.F.; Albisetti, W. Pseudoaneurysm of the peroneal artery: An unusual complication of open docking site procedure in bone transport with Taylor Spatial Frame. Musculoskelet. Surg. 2013, 97, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczynski, J.; Beveridge, E.; Holdsworth, R.J. Iatrogenic pseudoaneurysm of the peroneal artery. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016, bcr2016215836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhao, R.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Z. Pseudoaneurysm of a high-division anterior tibial artery following primary TKA. Orthopade 2017, 46, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanaka, K.; Miki, K.; Akahori, H.; Imanaka, T.; Yoshihara, N.; Tanaka, T.; Nakayama, H.; Masuyama, T.; Ishihara, M. Therapy with a Covered Stent Graft for Pseudoaneurysm of the Peroneal Artery Complicating High Tibial Osteotomy—A Case Report. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2019, 58, 380.e13–380.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetic, V.; Lukic, B. Endovascular Management of Tibioperoneal Trunk Pseudoaneurysm with Arteriovenous Fistula. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2020, 60, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristiani-Winer, M. Distal peroneal artery pseudoaneurysm. Acta Ortop. Mex. 2021, 35, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, J.; Schäfer, F.P.; Kobe, A.R.; Messmer, F.; Pape, H.C.; Rauer, T. Ordinary injury, big surprise—Traumatic false aneurysm and arteriovenous fistula of the posterior tibial artery after civilian trauma: A case report. Trauma Case Rep. 2021, 32, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Plotnik, A.N.; Srinivasa, R.N.; Szeder, V.; Moriarty, J. Preservation of Posterior Tibial Artery Flow Following Dissection with Associated Aneurysmal Degeneration in Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Type IV Treated with Flow-Diverting Stent. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2021, 73, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgopoulou, C.; Nikolakopoulos, K.; Ntouvas, I.; Papadoulas, S.; Kritikos, N. A rare combination of tibial artery aneurysm and traumatic arteriovenous fistula: A case report. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 42, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, J.J.; Perry, L.D.; Tamburrini, D.; Kumar, S. Successful Coil Embolization of a Large Anterior Tibial Artery Pseudoaneurysm After Open Reduction Internal Fixation of a Bi-condylar Tibial Plateau Fracture. Am. Surg. 2023, 89, 3886–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R.J.; Sellars, J.; Vennam, S.; Bhutia, S. Off-label use of PK Papyrus coronary covered stent to treat traumatic pseudoaneurysm of posterior tibial artery. ANZ J. Surg. 2023, 93, 1398–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spronk, S.; den Hoed, P.T.; Veen, H.F. Case report: Blue toe syndrome caused by a true crural aneurysm. J. Vasc. Nurs. 2003, 21, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.; Ma, J.; Huang, M.; Li, J.; Ma, X. Comparison of three different treatment methods for traumatic and Iatrogenic peripheral artery pseudoaneurysms. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 14, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.