Abstract

The northern areas of Pakistan are highly vulnerable to climate change due to anthropogenic activities and deforestation, which directly affect the precipitation pattern and variations in temperature. Due to these climate fluctuations, cloud bursts, extreme events like floods and droughts, and the melting of glaciers occur. This study presents the statistical trend analysis of the Dasu watershed in northern Pakistan using a non–parametric approach. In this study, the hydroclimatic data of 16 meteorological stations from 1980 to 2022 were used and the major focus was on an annual Rabi and Kharif seasonal trend analysis. Research revealed that the rate of precipitation increased from the east to west side of the study area in the annual Kharif season, while in the Rabi season, only four stations showed an increasing trend, and the remaining showed a decreasing trend, of which shendor2 showed a significantly decreasing trend with a rate of −3.91 mm/year. On the contrary, annual temperature was declining in the east side of the study area, while three stations showed significantly increasing temperature trends in the central region of the study area. Kharif season showed a decreasing trend in the major part of the study area, while Rabi season’s temperature revealed a significantly increasing trend in most of the stations and a decreasing trend in some eastern parts of the area. Overall, the majority of the study area revealed non–significant warming trends across the annual Rabi season, while the kharif season showed a decreasing trend. Precipitation trends remained largely non–significant but increasingly variable. The findings of this research can be utilized by research institutions and farmers to modify their cropping patterns and cropping calendar to optimize crop productivities.

1. Introduction

Climate change poses a threat to humanity, biodiversity, and the agricultural sector globally [1]. Temperature variation affects the precipitation pattern, which extends the cropping seasons, disrupts the irrigation scheduling, and sometimes, due to excessive precipitation, floods and drought conditions occur, which directly affect crop growth [2].

Bilgili et al. [3] analyzed various climatic factors and trends in Europe and globally from 1970 to 2023. The results indicated that the average air temperature for Europe in 2023, relative to 1991–2020 as a baseline, increased by 1.0738 °C and precipitation for the same period of time increased by 0.0413 mm annually. The same climate indicators were conducted globally, which indicated a 0.6008 °C increase in temperature, and there a decline in precipitation by 0.0130 m.

A study was conducted in Jimma City, Southwestern Ethiopia, for a forty–year period (1978–2017). To monitor the significance level and linear trend analysis, they used the M–K test and Sen’s slope estimator. Results indicated that the maximum temperature changes were between 0.033 and 0.045 °C (January and April), while the minimum temperature trend changes were between 0.081 and 0.025 °C in November and April, respectively. The annual precipitation variation coefficient was 11%. The same as the 85% result from the survey which indicated an increasing trend in temperature [4].

Pakistan’s economy mainly lies in the agriculture sector and is the fifth affected country by climate change [5]. A total of 60% of Pakistan’s population is directly or indirectly linked to the agriculture sector for their livelihood. Water resources in the Himalayan region, especially the Dasu watershed, are essential for hydropower production, domestic and commercial water use, as well as agricultural use. Kharif and Rabi cropping seasons depend on precipitation and temperature patterns [6] but the seasonal and monsoon patterns shift due to global warming, which is threatening food security. It is estimated that, by the end of 2040, agricultural production will suffer an 8–10% decline if the temperature increases at the same rate [7].

Khan et al. [8] investigated climate change in two time periods (1962–1990, 1991–2019) of Pakistan using 54 stations with a differential statistical method. The study area was divided into five homogenous zones. M–K test analysis showed there was an increasing trend in precipitation and a decreasing trend in Tmin and Tmax in the Karakoram zone during the first time period. On the contrary, from 1991 to 2019, an inverse relation was found as there was an increase in Tmin and Tmax and a decrease in precipitation. Reference [9] analyzed the spatiotemporal fluctuation at UIB using 20 stations’ data. During 1991–2013, the Tmax for 10 stations showed rapid warming, from which Naltar, Gupis, and Khunjrab indicated an increase of 0.43, 0.29, and 0.36 °C/decade, respectively.

Anjum et al. [10] investigated the change in precipitation and temperature in three major mountainous ranges of Pakistan from 1975 to 2014. The gauge weight method was used to estimate the areal average of climatic variables (temperature and precipitation). For trend analysis, they used the non–parametric M–K test, Sen’s slope estimator, and the Mann–Whitney U–test. Results indicated that the annual average temperature of all mountainous ranges was increasing by 0.08, 0.04, and 0.03 °C/decade in Karakoram, Hindu–Kush, and the Himalayas, respectively. On the contrary, precipitation showed a mixed trend. In the Himalayas, the annual precipitation trend was significantly decreasing (38.90 mm/decade) while the Hindu–Kush and Karakoram showed an increasing trend in annual precipitation with rates of 13.88 mm/decade and 11/86 mm/decade, respectively [11,12].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

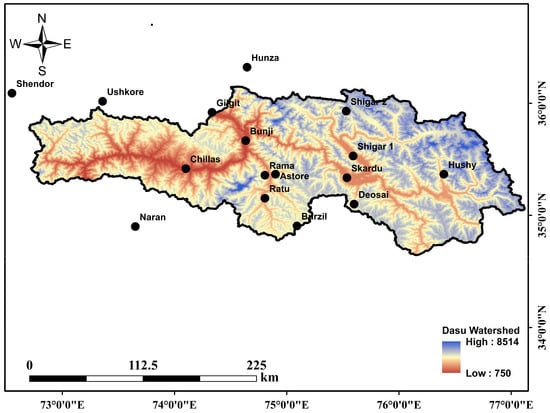

The Dasu dam is being constructed on the Indus River, which is located in the upper Kohistan district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, and its reservoir area is located in the Gilgit Baltistan province of Pakistan. The Dasu hydropower project site is being spread along the Indus River, 7 km north of the Dasu town and 348 km north of Islamabad. The coordinates of this study area are 35.32° north latitude and 73.2° east longitude (Figure 1). This project is a run–of–the–river hydropower project. It plays an important role in the agriculture sector because Pakistan’s economy mainly depends on agricultural exports. According to PMD (Pakistan Meteorological Department), the average precipitation of the Dasu area is 648 mm, and the hottest month is July with a maximum temperature of 36 °C, while the coldest month is January with a minimum temperature of 2.5 °C (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Dasu watershed with 16 meteorological stations.

Table 1.

Study area specification.

2.2. Data Set

Pakistan Meteorological Department (PMD) provided the daily data of 14 stations, while the daily data of 2 stations were provided by WAPDA. The above–mentioned organizations provided the data of precipitation and temperature for a 43–year time period (1980 to 2022), which were utilized in this study. The threshold values of the daily data were checked three times by applying the standard deviation. If the threshold and missing values were greater than 5% in a single month, the data from that specific month were not considered for analysis. After the arrangement of daily data, the data were converted to monthly, annual, Rabi, and Kharif periods.

2.3. Mann–Kendall Trend Test

“Mann–Kendall Test” (MK) and “Theil–Sen’s Slope Estimator Test” were used for the trends of precipitation (precipitation) and temperature in this study. The mathematical equations of Mann–Kendall for calculating S, “variance” V(S), “Standardized test statistics” Z, and “corrected variance” V(S) are given below:

First of all, the mean (S) value was calculated from the yj and yi, which are the values of i and j in the time series data, respectively. After the mean, the variance (V(S)) was calculated with the above equation, in which n indicates no of observations and t indicates the extent of time for time series data. From the mean and variance values Mann–Kendall Statistics Z can be evaluated with the given equation.

2.4. Interpolation Technique

A Geographic Information System (GIS) technique was used to capture, store, analyze, and visualize the geographically referenced data. In this study, we used GIS to interpolate our data, which were obtained from the M–K test. We used Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW), which is a geostatistical method in Geo Information Systems (GIS) software (ArcMap 10.8). We put our trend analysis values through this technique, which included the latitude and longitude of the meteorological station, as well as the Z–value and Q–value, which we interpolated for the spatial analysis.

3. Results

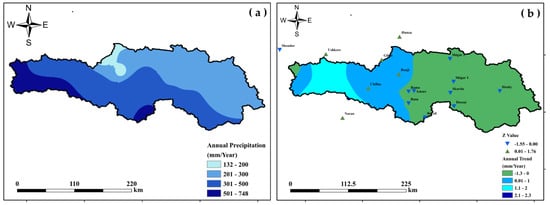

3.1. Precipitation Annual Trend

Annual average precipitation in the Dasu watershed was 407.48 mm, with the minimum at Hunza (120.49) and the maximum at Naran (1392.23) station (Figure 2a). Annual Mann–Kendall results showed that there was a non–significant decreasing trend in the North–East region of the study area, and the most west station (Shendor) also showed a decreasing trend with Z–value −1.55 and rate of −2.94 mm/year (Figure 2b). The remaining area of the Dasu watershed showed an increasing trend, but not significantly. The Ushkore and Naran stations showed the most increasing trend with Z–values 1.76, 1.67, and rates of 2.03 and 5.72 mm/year, respectively.

Figure 2.

(a) shows the annual precipitation range and (b) shows the annual trend in precipitation.

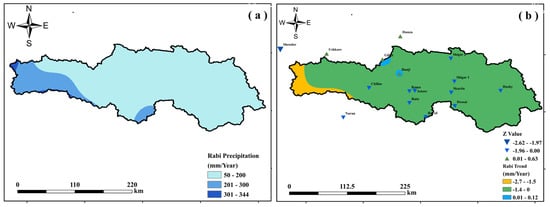

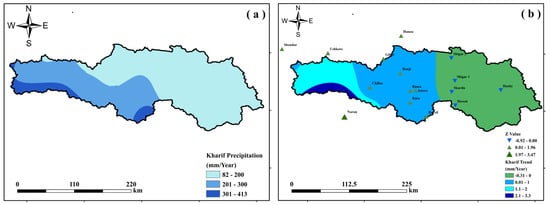

3.2. Precipitation Seasonal Trend

In the Rabi and Kharif seasons, the annual precipitation was 186.76 mm and 218.12 mm, respectively (Figure 3a). Results of Mann–Kendall showed that in the Rabi season, only four stations (Hunza, Gilgit, Bunji, Ushkore) showed a non–significant increasing trend, and all the remaining stations indicated a non–significantly decreasing trend, except Shendor2, which showed a significantly decreasing trend with Z = −2.62, with a rate of −3.91 mm/year (Figure 3b). The precipitation trend of the Kharif season showed there was a non–significant decreasing trend in the North–East region (Stations: Shigar 1, Skardu, Deosai, Hushy and Shigar 2) (Figure 4a), while the remaining stations of the study area showed a non–significant increasing trend, except Naran, which showed a significant increasing trend with Z–value 3.47 and with a rate of 7.92 mm/year (Figure 4b).

Figure 3.

(a) shows the Rabi precipitation range and (b) shows the Rabi trend in precipitation.

Figure 4.

(a) shows the Kharif precipitation range and (b) shows the Kharif trend in precipitation.

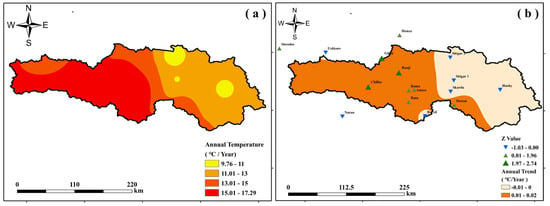

3.3. Temperature Annual Trend

The annual average temperature of the study area, as per the results, was 14.40 °C (Figure 5a). Mann–Kendall results indicated a decreasing annual trend of temperature in the North–East region, adding to Burzil and Ushkore, they also showed a decreasing trend, but not significantly, while the remaining stations showed an increasing trend in the area (Figure 5b). The only stations that showed a significantly increasing trend were Bunji, Chillas, and Hunza, with Z (2.55, 2.74, and 2.74, respectively), with a rate of 0.2 °C/decade for each station.

Figure 5.

(a) shows the annual temperature range and (b) shows the annual trend in temperature.

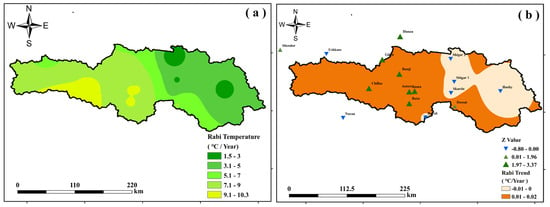

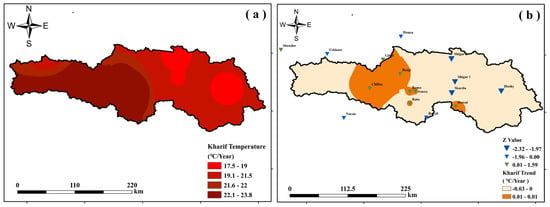

3.4. Temperature Seasonal Trend

The annual average temperature of the Rabi and Kharif seasons was 6.98 and 21.37 °C, respectively (Figure 6a). In the case of the Mann–Kendall results of the Rabi and Kharif seasons, temperature in the Rabi season revealed the same decreasing trends of the stations as those of the annual results, but with a different rate (Figure 6b). Only two stations showed a non–significant increasing trend; the remaining stations showed a significantly increasing trend in Kharif Season (Figure 7a). Temperature in the Kharif season showed an increasing trend in the middle of the area, with the highest rate of 0.1 °C/decade at Deosai station with Z = 1.59 (Figure 7b). The remaining 50% of the stations showed a decreasing trend in area, with significantly decreasing stations being Hushy, Shigar 1, Skardu, and Shigar 2, with Z values of −2.32, −2.26, −2.13, and −2.13, respectively, and with a rate of −0.2 °C/decade for each station.

Figure 6.

(a) shows the Rabi temperature range and (b) shows the Rabi trend in temperature.

Figure 7.

(a) shows the Kharif temperature range and (b) shows the Kharif trend in temperature.

4. Conclusions

- This study used the Mann–Kendall test to analyze trends in precipitation and temperature for annual, Rabi, and Kharif periods in the Dasu watershed. The results revealed a majority of non–significant trends in temperature in all three of the time spans. Precipitation trends remained largely non–significant but increasingly variable.

- Overall, the precipitation trend was increasing in the annual (Z = 0.063, Q = 0.055) and Kharif (Z = 1.319, Q = 0.652) time span, while decreasing in the Rabi season (Z = −1.34, Q = −1.158). Temperature was increasing in the annual (Z = 0.900, Q = 0.005) and Rabi (Z = 1.465, Q = 0.009) season, while decreasing in the Kharif season (Z = −0.502, Q = −0.004).

- These climatic changes, if maintained, could be very beneficial for water availability, crop productivity, and hydropower operations. Therefore, adaptive water and better agricultural management practices must be introduced, taking into account emerging climate patterns in the watershed.

- Future work should consider incorporating additional statistical methods (e.g., Sen’s slope, Pettitt test) and integrating climate model projections to better understand future scenarios and inform policy interventions.

Author Contributions

Data collection, S.A. and A.A.K.; bias correction, S.A. and C.M.S.; data preparation, A.A.K. and K.M.; data analysis, S.A., S.R.S. and M.N.A.; writing and review, S.A., A.A.K. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

On–demand data will be provided.

Acknowledgments

Pakistan Meteorological Department, PMAS–Arid Agriculture University, and Pilot Project for Data Driven Smart Decision Platform (DDSDP) for increased agriculture productivity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Statistics|FAO|Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: http://www.fao.org/statistics/en (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Heino, M.; Kinnunen, P.; Anderson, W.; Ray, D.K.; Puma, M.J.; Varis, O.; Siebert, S.; Kummu, M. Increased Probability of Hot and Dry Weather Extremes during the Growing Season Threatens Global Crop Yields. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilgili, M.; Tokmakci, M. Climate Change and Trends in Europe and Globally over the Period 1970–2023. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2025, 139, 103928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeda, D.O.; Feyssa, D.H.; Garedew, W. Meteorological data trend analysis and local community perception towards climate change: A case study of Jimma city, Southwestern Ethiopia. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 5885–5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Chaudhary, M.N.; Jafri, S.Z.H.; Malik, S.; Ali, N.; Awan, D.-e.S. Climate Change and Its Impacts on Pakistan. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 9195–9217. [Google Scholar]

- Bibi, S.; Ali, N.; Nazneen, S.; Rehman, S.; Yousaf, R.; Khan, S. Climate Change Impacts on the Cropping Pattern in the Foothills of the Himalayas, Pakistan. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.; Raza, T.; Bhatti, T.T.; Eash, N.S. Climate Impacts on the Agricultural Sector of Pakistan: Risks and Solutions. Environ. Chall. 2022, 6, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Ali, S.; Mayer, C.; Ullah, H.; Muhammad, S. Climate Change and Spatio-Temporal Trend Analysis of Climate Extremes in the Homogeneous Climatic Zones of Pakistan during 1962–2019. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, Y.; Yaoming, M.; Yaseen, M.; Muhammad, S.; Wazir, M.A. Spatial Analysis of Temperature Time Series over the Upper Indus Basin (UIB), Pakistan. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2020, 139, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, M.N.; Cheema, M.J.M.; Hashmi, M.Z.U.R.; Azam, M.; Afzal, A.; Ijaz, M.W. Climate Change in the Mountains of Pakistan and Its Water Availability Implications. In Water Resources of Pakistan: Issues and Impacts; Watto, M.A., Mitchell, M., Bashir, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 79–94. ISBN 978-3-030-65679-9. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, W.; Cheema, M.J.M.; Anjum, M.N.; Amin, M.; Hussain, S. Projections of precipitation and temperature changes in the Neelam River Basin, western Himalaya: A CMIP6-based assessment under shared socioeconomic pathways. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.U.; Anjum, M.N.; Asif, M.; Iqbal, T.; Hussain, S.; Sarwar, H.R.A.; Abbas, A. Spatio-Temporal Assessment of Satellite Based Precipitation Products for Hydroclimatic Applications over Potohar Region, Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 23, 18. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).