Abstract

The outbreak of COVID-19 challenged the sustainability of global agri-food markets. Through this research, the authors have made sincere efforts to recognize and remove/improve the potential factors that contribute towards an inefficient agro-based supply chain. COVID-19 has created much urgency to evaluate the existing supply chain and to propose a valid solution. In this particular research, the involvement of intermediaries is the point of focus. In addition, the profit margins for the farmer are hugely affected due to intermediaries. The current supply chain must be optimized, and this will lead to easier flows between each phase of the supply chain. Surveys were conducted and the farmers’ problems and expected solutions are highlighted in this research. Farmers in the northern states of India experienced more significant disruptions than those in other states because of a decreased availability of foods due to lack of diversity in crops. This research examines the existing supply chain for wheat crops and presents an optimization of the respective supply chain to save farmers more revenue. Through this research, the authors have attempted to observe and explore the problems faced by farmers and consumers due to the inefficient supply chain infrastructure prevalent in India because of the onslaught of COVID-19 and find an efficient solution. Due to the lack of adequate infrastructure, storage facilities, and old food-processing and supply chain technology almost 30–35% of the agricultural produce in India is wasted. A scientific solution to the existing problems is also presented after analyzing the existing supply chain and crop selection of farmers.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has created much urgency to evaluate the existing supply chain and to propose a valid solution. The prices of crops were drastically affected, and many farmers were not able to make ends meet. The supply chain used by the farmers has many unnecessary complications [1]. In this particular research, the involvement of intermediaries is the point of focus. Intermediaries’ involvement leads to higher prices of the crops for the end customer. In addition, the profit margin of the farmer is hugely affected. In this research, we have directly interviewed farmers, customers and drivers about the conditions before COVID and during COVID. The current supply chain must be optimized, and this will lead to easier flows between each phase of the supply chain [2,3]. We have explained why improving quality controls across the whole food supply chain is a must for attaining sustainable control. Working together during COVID-19 is necessary. This study emphasizes the need for optimization to ensure smoother flows and reduced dependency on intermediaries. A farmer cannot fully benefit by just minding his duties [4]. We carried out an investigation into how collaboration in food supply chains leads to innovation and how that, in turn, leads to sustainability with a case study [5]. We studied the farmers markets in Bangalore during lockdown. Surveys were conducted and the farmers’ pros and cons were depicted. In the study in [6], a method for increasing revenue for farmers and other parties was described. They have explained the co-ordination problems when consumer demand is uncertain. They also explained that revenue sharing factors can co-ordinate the agricultural supply chain, and by adjusting these, the profits of the parties can be increased. Phone surveys were conducted [7] and the results concluded that farmers experienced greater disruptions as a result of the decreased market availability of foods. The COVID-19 problem has revealed India’s agriculture and food markets’ fragility. Small and marginal farmers make up 90% of India’s agricultural sector [8], and they are particularly exposed to economic shocks like COVID. Farmers were drastically affected by COVID-19, and people who were expecting 700 to 800 thousand Indian rupees as profit on their crops were finding it hard to make their initial investment back [9]. In the early months of the pandemic, China and then Italy took a number of steps to ensure food security [10]. Many articles were written on measures for farmers during COVID-19. Some of them suggest: (1) redirecting farm supply chains to local areas, (2) moving away from cash crops, (3) increasing allocations for direct transfers and (4) setting up mobile food vans that would help farmers get through this pandemic [11]. Although some came into existence and some did not, many did help farmers to some extent. It is necessary to develop an innovative model which could increase the profit margin of farmers [12].

2. Methodology

In this study, the inefficiencies of the past and continuing agricultural supply chain management structure are investigated. The study is focused on scrutinizing the current agricultural supply chain management framework and innovate and reduce the shortcomings in the proposed framework [13]. The survey mainly focuses on farmers and consumers in rural and semi-urban areas.

Step 1: The analysis of various research papers and supply chain management frameworks/structures which are prevalent today. Step 2: Highlighting the shortcomings of the current framework of the agro-based SCM, highlighting the issues faced by the members of the supply chain management (farmers, drivers, customers, government) pre-COVID-19 and during COVID-19, conducting surveys on the current SCM framework, agriculture, etc, with a set questionnaire to gain insights into the situation and needs of the farmers. Step 3: Devising a new innovative SCM framework that is more efficient and less complex than the prevailing frameworks. Step 4: Again, conducting a survey to gain feedback on our framework. Modifying and altering it according to the market situation and farmers’ needs. Step 5: Planning and implementation. The research adopts a comprehensive approach, combining literature review, surveys, personal interviews and data collection. The focus is on farmers, and consumers in rural and semi-urban areas. The study is limited by COVID-19 restrictions, relying on secondary sources.

3. Major Issues in the Existing Frameworks

The inefficiencies of the current supply chain structure are highlighted, with a focus on various stages and the involvement of intermediaries. Major problems include poor credit facilities, convoluted marketing channels and inadequate information dissemination.

4. Data Collection

Data and resources regarding the present study were collected from respondents through a structured set of questionnaires and interviews. The collected data are observed, analysed and tabulated considering the objectives of the study using simple statistical tools such as frequency and percentages. All the major constraints faced by the farmers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Constraints faced by farmers.

In Table 2, data collected from the farmers on their suggestion to overcome these constraints are portrayed.

Table 2.

Solutions to the constraints faced by farmers.

From the tables presented, we can conclude that there is an urgent need to remove the unwanted intermediaries from the system and to develop strategies such as minimal transport charges, adequate credit facilities for farmers and information sharing on market rates which can cut down costs from the supply chain structure, so that customers don’t have to pay more money to acquire the produce.

Table 3 shows the preferred marketing channels used by the farmers for the sale of wheat. From the data collected, we can conclude that majority of the farmers have been traditionally selling their crops through commissioning agents (37 votes; 61.67%) followed by local markets (10 votes; 16.7%) and the lowest voted channels are cooperative marketing societies (2 votes; 3.33%) and supermarkets (3 votes; 5.00%). The main reasons behind farmer’s not selling their produce through cooperative marketing society and supermarkets can be lack of market information, which also constitutes four of the major problem farmers are facing in Table 1, and the traditional supply chain structure is devised in such a way that it does not provide small farmers with a lot of options for marketing channels to choose from. So, under compulsion, these farmers are forced to sell through any channel that is easily accessible to them, thereby losing a lot of revenue. It should be noted that the selling price for a consumer is INR 39.9 per kilogram but a farmer may receive only INR 12 which is not even 30% of the total share.

Table 3.

Share of intermediaries in the consumer rupee.

Hence, it is of paramount importance to devise a supply chain that would increase the profit to the farmers significantly. A new framework is suggested, involving government support and a streamlined process. Farmers would receive proper equipment and training, and credit facilities and direct access to markets.

5. Frameworks

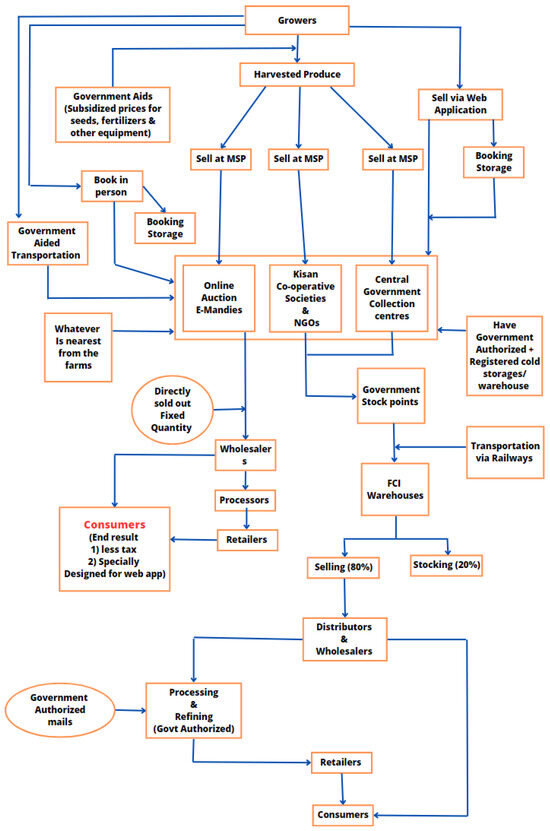

This is a system aimed at regularizing the market cost of a crop and providing the farmers their fair share of dues. This system is devised following a proper market study of current channels and aims to fill the gaps in current supply chain and create an ideal sustainable supply chain. Here, the government has a more active role to play as it can ensure a good harvest by providing farmers with the equipment and proper knowledge for a good harvest. They can also provide them with interest free loans so that a farmer can support his family for the initial 6 months without being completely dependent on the harvest. Once the harvest is completed, the farmers sell to the collection points setup by the government at maximum selling price, they can also put their produce up for auction using the E-mandi platform and obtain a desired rate. The produce collected at government points would then be transported to storage units setup by the food corporation of India, where 20% is then separated for reserve for natural calamities. A total of 80% of the stock is then opened up to mills, wholesalers, dealers etc. The suggested frame-work is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Suggested framework.

6. Conclusions

This study sheds light on the challenges within India’s agro-based supply chain, particularly during the pandemic. The results of the study and the model proposed will help the farmers and consumers to face any natural calamity faced by the world that is of the same nature as the pandemic. The framework produced increases the share of farmers up to 50% of the consumer price. The study succeeds in not only providing the farmers a fair share of the market but also in controlling market inflation, corruption and tax evasion, as observed in the current system. Extensive survey analysis on different stages of the supply chain helped us highlight the issues. These were further understood by studying the existing literature and talking to APMC officials in various regions. From quantitative and qualitative studies, we were able to devise a new supply chain which addressed all the highlighted issues, which resulted in controlled market price with a fair share going to the farmers.

7. Limitations to the Study

This paper was prepared based on surveys conducted, the existing literature available and data collected from government authorities. This study is limited to only certain geographical locations in India.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.; methodology, K.V.; validation, N.W.; formal analysis, S.K.; writing—review and editing, D.R.-B.; software, E.B.-I.; data curation, Y.M.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, K.V., N.W. and S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Original data is available with the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anand, N.; Trivedi, S.; Negi, S. Impact of COVID-19 on agriculture supply chain in India and the proposed solutions. Int. J. Sustain. Agric. Manag. Inform. 2021, 6, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamprecht, J.; Corsten, D.; Noll, M.; Meier, E. Controlling the sustainability of food supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. 2005, 10, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Yen, P.; Agarwal, R.; Arshinder, K.; Bajada, C. Collaborative innovation and sustainability in the food supply chain- evidence from farmer producer organisations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefian, N.; Devy, M.S.; Geetha, K.; Dittrich, C. Lockdown farmers markets in Bengaluru: Direct marketing activities and potentials for rural-urban linkages in the food system. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2021, 10, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-F.; Wang, Z.-X. Research on Coordination of Multi-Product “Agricultural Super-Docking” Supply Chain. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 30, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, F.; Kannan, S.; Kramer, B. Impacts of a national lockdown on smallholder farmers’ income and food security: Empirical evidence from two states in India. World Dev. 2020, 136, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Bijeta, M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Smallholder Farmers in India and the Way Forward—IGC. 1 March 2021. Available online: https://www.theigc.org/blog/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-smallholder-farmers-in-india-and-the-way-forward/ (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Aggarwal, M. COVID-19 Lockdown Locks Down Farmers’ Income. 3 April 2020. Available online: https://india.mongabay.com/2020/04/covid-19-lockdown-locks-down-farmers-income/ (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)—Addressing the Impacts of COVID-19 in Food Crises (May Update)—World | ReliefWeb. 18 May 2020. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-addressing-impacts-covid-19-food-crises-may-update (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Four Measures that Can Help Farmers Deal with the Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown. 24 April 2021. Available online: https://thewire.in/agriculture/farmers-covid-19-lockdown-india-relief-measures (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Arumugam, N.; Fatimah, M.A.; Chiew, E.F.; Zainalabidin, M. Supply chain analysis of fresh fruits and vegetables (FFV): Prospects of contract farming. Agric. Econ. 2010, 56, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panghal, A.; Singh, B.P.; Sindhu, S. Amity Journal of Agribusiness.1.1. Amity J. Agribus. ADMAA 2016, 1, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, H.; Gray, R.; Nolan, J. Agricultural supply chain optimization and complexity: A comparison of analytic vs. simulated solutions and policies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 159, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).