Abstract

Introduction: Temporary non-tunneled catheters are necessary in patients with chronic kidney disease requiring acute hemodialysis care, and complications associated with these catheters, such as infection and thrombosis, represent the most important sources of morbidity. There are no studies available that suggest the optimum duration of their use before catheter exchange or removal. This study aimed to explore the duration of temporary catheter insertion before the occurrence of catheter-related infection and mechanical complications in hemodialysis patients. Methods: Systematic searches were conducted according to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines on four databases up to 1 May 2025 (PROSPERO: CRD420251069657). The study outcome was the occurrence time to catheter-related infection and mechanical complications (thrombosis, obstruction, and kinking, causing dysfunction, failure, or insufficient blood flow) in days, pooled using a single-arm meta-analysis. Mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) were used as the summary statistics. Results: Nine studies involving 1448 participants undergoing hemodialysis using temporary catheters were included. Incidence of infection ranged from 0.7 to 13.58 per 1000 catheter-days. The most common bacterium identified was Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The pooled mean time to catheter-related infection from 298 catheters was 15.98 days (95% CI 10.47–21.50; I2 = 97.73%). We also found that the pooled mean time to mechanical complications from 507 catheters was 6.69 days (95% CI 2.49–10.90; I2 = 98.03%). Conclusion: Among patients who developed complications, the mean time from temporary catheter insertion was approximately two weeks to the occurrence of catheter-related infection and one week to mechanical complications. Our finding was consistent with the recommendation of the KDOQI guideline, which suggests limiting catheter duration to typically less than two weeks.

1. Introduction

Vascular access is crucial for effective hemodialysis. Sustainable and complication-free hemodialysis relies highly on a safe, unobstructed, and reliable blood flow. Established types of vascular access used in hemodialysis are arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) and arteriovenous grafts (AVGs) as permanent accesses [1], and central venous catheters (CVCs) [2,3]. The native AVF stands out as the preferred vascular access due to its durability and reduced risk of infection or intervention. However, many patients still need temporary vascular access for a short period of time because of acute renal failure, delayed AVF development, access failures, or transitions to transplants, peritoneal dialysis, or AVF maturation [2,3]. CVC is better tolerated in patients who are hemodynamically unstable or have limited cardiovascular reserve, whereas AVF and AVG impose a greater hemodynamic burden. CVC does not create an arteriovenous shunt and, therefore, does not increase cardiac output or preload, making it more suitable for patients with acute hemodynamic instability, severe heart failure, or critical illness [4]. Also, temporary catheters may be inserted with relative ease by a bedside procedure under local anesthesia [2].

Recent data from the Dialysis Outcome and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) reveals that a significant portion of patients in Europe and the US begin hemodialysis treatment with a catheter as their primary access [1]. Specifically, 15–50% of patients in Europe and 60% of patients in the US utilize catheters for vascular access during their initial hemodialysis session [1]. According to the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), catheters were employed in 62.6% of patients in the US for vascular access during their first hemodialysis treatment, while only 16% opted for an AVF for their initial session. Notably, approximately 81% of patients relied solely on catheters as their vascular access or were awaiting the maturation of an AVF [5]. In addition, among new end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients, 48% of those in the US and 75% of those in Europe commence hemodialysis with temporary catheters [6]. Even among prevalent patients, over a third still use temporary catheters as their vascular access [6]. Concurrently, the use of CVCs at the initiation of dialysis has seen a notable increase, rising from 61% in 2015 to 71% in 2020, representing a relative increase of 16% [7].

CVC is an essential modality for the delivery of hemodialysis in patients who lack alternative functional vascular access, whether in the setting of acute or chronic renal failure. Its principal advantage lies in its rapid and relatively easy insertion, allowing for immediate initiation of hemodialysis. Nevertheless, the use of CVC is associated with a substantially higher rate of complications compared with other vascular access options, such as AVF and AVG [1,8]. CVCs are categorized into temporary catheters and tunneled permanent catheters (TPC). A tunneled catheter is considered permanent because it can be used for long-term vascular access for hemodialysis patients. In contrast, a temporary catheter, also called a non-tunneled catheter (NTC), is used for urgent hemodialysis, typically in clinical settings of acute kidney injury (AKI) or rapidly deteriorating chronic kidney disease (CKD) when a patient lacks an ESRD care plan. A temporary catheter for hemodialysis is considered a significantly less favorable option compared to AVF and AVG due to the higher incidence of complications [9,10,11,12].

One of the most significant causes of hospital admission (16–25%) and mortality among hemodialysis patients is vascular access complications [6,13]. Temporary catheters are associated with various complications, both early and late [14]. Early complications, typically occurring within the first week after insertion, are most commonly related to mechanical issues, such as catheter malposition, kinking, or underlying venous abnormalities [14], including puncture site hemorrhaging, hematoma formation, artery punctures, and spontaneous pneumothorax [9,15]. Late complications, which are the most common, are mechanical complications and catheter-related bacteremia (CRB) [1,16]. Developing either of these complications significantly impacts the functionality and lifespan of the catheter, leading to high rates of morbidity and mortality despite the considerable cost [9,15]. Temporary catheters are also associated with much higher rates of CRB [17]. The incidence of bacteremia is 10 times greater than that of either fistulas or synthetic grafts [18,19]. The main risk factors for developing CRB are the duration of catheter use and the number of performed dialyses [18,19,20]. Prolonged catheter use provides a greater opportunity for bacterial colonization and subsequent infection. According to European Recommendations for Good Practice in hemodialysis, temporary catheters are indicated only in emergencies and should be replaced as soon as possible by a TPC to reduce the risk of infection [21]. However, this switch can be complicated by patients’ comorbidities, poor vasculature, older age, and an inadequate multidisciplinary approach [2].

It remains uncertain whether the increased burden of adverse events associated with this access modality is an inevitable consequence of establishing a persistent conduit between the external environment and the intravascular compartment, or whether it predominantly reflects the greater comorbidity burden characteristic of patients who require CVC. Nevertheless, there is now a strong emphasis in nephrology practice that increasingly emphasizes minimizing catheter dependence whenever feasible and, in patients for whom catheter use is unavoidable, implementing measures aimed at reducing catheter-related complications [1,8,9]. However, to date, there are no studies available that suggest the optimum duration of temporary catheter use before catheter exchange or removal. Previous meta-analyses have commonly used the incidence rate of catheter-related infection as the outcome measure, and none have evaluated the average duration of event occurrence. To answer this question, we accordingly conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to explore the duration of temporary catheter insertion before the occurrence of complications, specifically catheter-related infection and mechanical complications, as outcomes in hemodialysis patients. Finally, we discussed this observed pattern of duration in catheter complications in relation to the patterns described in the current hemodialysis vascular access guidelines. All catheters used in this study were NTCs, which will be further regarded as temporary catheters. We will also consistently use the term CRB throughout the manuscript and interchangeably use the terms catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) and catheter-associated bloodstream infection (CABSI).

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [22] (see Supplementary Table S1 for the completed PRISMA checklist). The protocol of this study has been registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD420251069657).

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection of Studies

A computerized data searching of relevant studies was conducted in four electronic medical databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ProQuest from inception to 1 May 2025. Keywords were constructed based on Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms combined with their synonyms and other additional terms as follows: “temporary catheter”, “hemodialysis”, “complication”, and “duration”. We additionally conducted a manual search on Google. There were no language or publication date restrictions. The complete search strings for each database are provided in Supplementary Table S2. Articles were then deduplicated and screened according to their title and abstract. Next, studies with available full-texts were retrieved and assessed according to the eligibility criteria. The overall study selection process was performed by two independent investigators (IK and BS). Any disagreements were resolved independently by a third investigator (AP).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) participants were adult patients aged 18 years or older undergoing hemodialysis; (2) the study used any type of temporary catheters for hemodialysis; (3) the study reported duration of catheter use as hemodialysis access before the occurrence of catheter-related infection or mechanical complications, including thrombosis, obstruction, and kinking causing dysfunction, failure, or insufficient blood flow for hemodialysis. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) irretrievable full-texts and (2) review articles, clinical trials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, case reports or series, letters to editors, and conference abstracts.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data extraction and quality assessment were performed independently by three of the co-authors (IK, BS, AP). Any disagreements were resolved in a consensus involving all authors. The extracted data included the authors’ name, publication year, and year of population sampling, study design and location, sample size, age, sex, comorbidities, number of catheters, definition of catheter-related infection and mechanical complications, type and vein location of temporary catheters, incidence, and time to onset of complications. We assessed the quality of cohort and cross-sectional studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) tool. For cohort studies, their quality was considered as “good”, “moderate”, or “poor” if the score was 7–9, 4–6, and 0–3, respectively. For cross-sectional studies, a score of 7–10 is “good”, 4–6 is “moderate”, and 0–3 is “poor”. One randomized controlled trial (RCT) study was assessed using the Risk of Bias 2 (RoB 2) tool.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA ver. 17.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). The study outcome was the occurrence time to catheter-related infection or mechanical complications in days, pooled using a single-arm meta-analysis. We pooled the events of thrombosis, obstruction, kinking, and poor flow into a single summary estimate of mechanical complications, as separate data were limited. Time to occurrence of events was calculated only among studies in which events occurred. Mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) were used as the summary statistics. We only included the population without the use of an antibiotic lock solution to estimate the time to catheter-related infection. For meta-analysis, data that were not reported in mean and standard error (SE) were transformed beforehand. Data in median and interquartile range (Q1–Q3) or range (minimum–maximum) were transformed first to mean and standard deviation (SD) using the method suggested by Shi et al. (2020) [23]. Subsequently, SD was transformed into SE using a standard formula by dividing it by the square root of the corresponding sample size. We performed meta-analyses if each outcome was reported by at least two studies.

The heterogeneity between studies was determined using Cochran’s Q statistic, and then its level was quantified using Higgins’ I2 statistic, with 0%, <25%, 25–75%, and >75% considered as negligible, low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Since we expected variability in the characteristics among the studies, we primarily applied the random-effects model for all analyses. p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Sensitivity analysis was carried out using the leave-one-out method. Analysis for publication bias was not conducted since there was no appropriate method to apply in a single-arm meta-analysis.

To search for potential variables contributing to heterogeneity, we conducted subgroup analyses based on regions, study designs, definition of outcome, and vein location of catheters. Due to inadequate data from the included studies, subgrouping analyses based on catheter location, such as internal jugular, subclavian, and femoral catheters, were not possible. Hence, we subgrouped the analyses into two: (1) data that included femoral catheters, which included studies that provided specific data for femoral catheters and studies that combined the data for femoral catheters with internal jugular and/or subclavian catheters; and (2) data that did not include any femoral catheters.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Literature Search

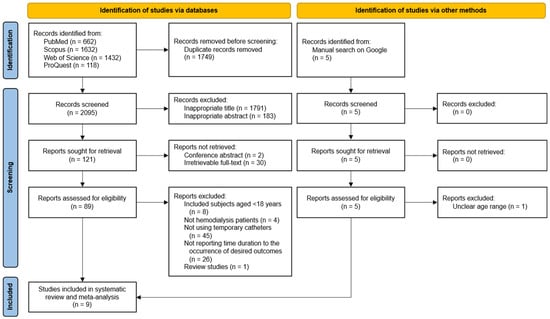

A PRISMA flow diagram of the overall study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1. Searches on databases resulted in a total of 3844 studies. Of those, 1749 studies were removed due to duplicates. We obtained 121 studies with eligible titles and abstracts and then thoroughly reviewed 89 studies. Afterwards, 84 studies were excluded due to the reasons shown in Figure 1. Additionally, we identified five studies through a manual search and excluded one study. Finally, nine studies [15,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] were included in the systematic review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the study selection process. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

3.2. Characteristics, Outcomes, and Quality Assessment of Included Studies

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. The nine studies comprised 1448 adults undergoing hemodialysis using temporary catheters. Study designs were cross-sectional (n = 1), cohort (n = 7), and RCT (n = 1). Four studies were conducted in Asia, four studies in Europe, and one in Africa. Most studies used only heparin for the catheter lock solution. One RCT had three arms; two of them were given an antibiotic lock solution, and one was given only heparin solution. The quality of all cohort and cross-sectional studies was good, with total scores ranging from 7 to 9 (Table 1; see details in Supplementary Table S3). The overall risk-of-bias judgment for one RCT according to RoB-2 was considered to be of some concern, as there was no detail regarding the pre-specified analysis plan or trial protocol (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

3.3. Time to Catheter-Related Infection

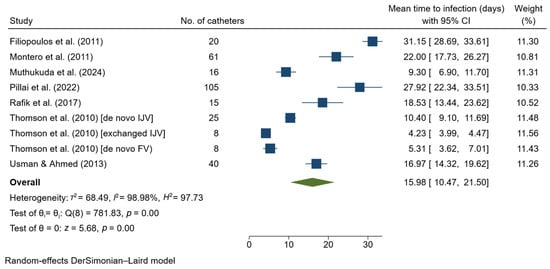

Outcome summary for catheter-related infection is presented in Supplementary Table S4. Eight studies used the term either CRB, CRBSI, or CABSI. Only one study used the term ‘infection’. In terms of the definition of CRB, two studies by Montero et al. [24] and Usman & Ahmed [25] used only clinical signs, while the rest used a combination of clinical signs and blood culture. The most common bacterium identified was Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Incidence of infection ranged from 0.7 to 13.58 per 1000 catheter-days. For meta-analysis, data from Filiopoulos et al. [26] that used an antibiotic lock solution were excluded. Also, Agrawal et al. [27] and Naumovic, Jovanovic, & Djukanovic (2004) [13] were excluded due to insufficient data; however, the outcome they reported was similar to that of other studies included in the meta-analysis. Accordingly, a total of 298 catheters from seven studies and nine datasets were analyzed, with the study by Pillai et al. (2022) [29] contributing the largest number of catheters (n = 105). Based on patients who experienced this event, the pooled mean time to catheter-related infection was 15.98 days (95% CI 10.47–21.50; Figure 2), with a high level of heterogeneity (I2 = 97.73%). Sensitivity analysis using the leave-one-out method showed no significant change in the pooled result.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for single-arm meta-analysis of mean time (days) from temporary catheter insertion to the occurrence of catheter-related infection in hemodialysis patients. CI, confidence interval; FV, femoral vein; IJV, internal jugular vein [24,25,26,28,29,30,31].

Subgroup analyses (Table 2) showed no differences in the pooled mean time between regions, in the definitions of catheter-related infection, or in the vein locations of the catheters. Although the findings were insignificant, studies that used clinical signs and blood culture showed a lower mean time to infection compared to those that only used clinical signs. A similar result was also observed for studies that included femoral catheters compared to studies that did not include any femoral catheters. Conversely, subgroup analysis according to study design revealed a significant difference (p < 0.001), indicating that study design might be a source of heterogeneity.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of time to occurrence of catheter-related infection and mechanical complications.

3.4. Time to Mechanical Complications

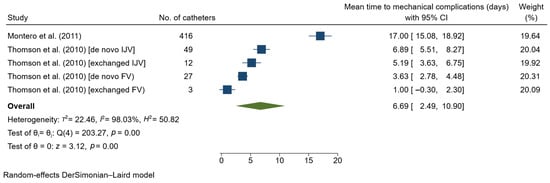

The outcomes for mechanical complications are summarized in Supplementary Table S5. Two studies reported mechanical complications using the term ‘poor flow’. The meta-analysis included 507 catheters, of which the study by Montero et al. (2011) [24] accounted for the largest number of catheters (n = 416). We found that the pooled mean time to mechanical complications was 6.69 days (95% CI 2.49–10.90; Figure 3) among patients who experienced this event, with a high level of heterogeneity (I2 = 98.03%). Sensitivity analysis excluding Montero et al. [23] showed a substantial change in the pooled result, to 4.16 days (95% CI 1.90–6.41). Analysis based on catheter location showed no significant difference between subgroups (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Forest plot for single-arm meta-analysis of mean time (days) from temporary catheter insertion to the occurrence of mechanical complications in hemodialysis patients. CI, confidence interval; FV, femoral vein; IJV, internal jugular vein [24,31].

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

Our study found that the average time from temporary catheter insertion to infection among patients who experienced this event was approximately 16 days, with a range from 10 to 21 days. On the other hand, we found the mean time from temporary catheter insertion to the development of mechanical complications among patients who experienced this event was around 7 days, with a range from 2 to 11 days. These findings highlight the relatively early development of catheter-related complications and that catheters should be well monitored to prevent unwanted outcomes.

Based on the location of venous catheters, infections in studies that did not include femoral catheters were seen at 17.95 days, while infections in studies that included femoral catheters were seen at 13.49 days. This finding indicated that the development of infections in femoral catheters occurred approximately at the 2nd week of catheterization, which was earlier than other catheter sites. Femoral vein catheterization is technically simple and rapid but is associated with higher risks of arterial puncture and infection, while subclavian access is generally avoided due to the risk of central venous stenosis; therefore, selection of the insertion site should be individualized based on operator expertise and the patient’s long-term vascular access plan [12]. The incidence of CRB should ideally be less than 10% at 3 months, as per KDOQI clinical practice guidelines for hemodialysis [11]. The high frequency of CRB in the second week and the relatively short duration of catheterization before CRB develops could be attributed to multiple factors [26].

CVC management, particularly for NTC, requires careful consideration of both patient- and device-related risk factors for CRB. Evidence indicates that prolonged catheter dwell time, use of multilumen catheters, underlying kidney disease, immunosuppression, and exposure to total parenteral nutrition are consistently associated with an increased risk of infection, factors that are highly relevant in acute dialysis settings [32]. Poor patient hygiene and inadequate adherence to catheter care protocols by dialysis unit staff are associated with an increased risk for Gram-negative CRBs [32,33]. In addition to these intrinsic and treatment-related risks, catheter care practices play a critical role, as audits of aseptic technique have demonstrated substantial variability in hub disinfection and access behaviors, which may directly contribute to microbial contamination of NTC. Importantly, catheter access practices represent a critical and potentially modifiable determinant of infection risk, as audits of aseptic technique have demonstrated inconsistent adherence to recommended “scrub the hub” procedures, with variability in both duration and technique of hub disinfection prior to catheter access [34]. Inadequate hub scrubbing has been shown to permit microbial contamination of the catheter lumen, thereby facilitating intraluminal colonization and subsequent bloodstream infection, a mechanism particularly relevant to NTCs that are accessed frequently in dialysis units. Additionally, dialyzer reuse and contaminated water are other risk factors associated with outbreaks of Gram-negative bloodstream infections [35]. Collectively, these findings underscore that infection risk in non-tunneled CVC is multifactorial and influenced not only by duration of use but also by catheter design, patient complexity, and adherence to standardized aseptic access protocols.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified specific interventions that are important in reducing the risk of CRBs. These interventions include hand hygiene, catheter and exit site care protocols, the use of antibiotic lock solutions, antiseptic-impregnated dressings and catheters, dialysis station disinfection protocols, and staff and patient education programs [27,36]. Staff training, periodic assessment of competency in catheter care and aseptic technique, and audits of hand hygiene and vascular access care have been shown to reduce bloodstream infection rates by up to 54% [37]. Coupled with patient education initiatives, these interventions would be the most appropriate strategies to reduce the CRB rate in this area. To control this high infection rate, practitioners should use antiseptic and antimicrobial coated or impregnated catheters, use antibiotic–anticoagulant locks, and limit the duration of use of temporary catheters [38].

Another late complication of vascular access is mechanical complications. Mechanical complications include thrombosis, catheter extrusion, and kinking, which can result in inadequate blood flow for effective hemodialysis without extending the prescribed dialysis session or may lead to complete catheter obstruction [14,15]. Patients with uremia are characterized by elevated plasma homocysteine concentrations and a chronic proinflammatory state, both of which are recognized contributors to enhanced thrombotic risk [14,39]. Furthermore, vascular injury resulting from catheter insertion may lead to endothelial disruption, thereby promoting platelet adhesion and activation of the intrinsic coagulation cascade. Thrombotic complications associated with catheter use may remain clinically asymptomatic or manifest as recurrent catheter dysfunction [14,15,39]. The KDOQI guidelines advise against the routine administration of prophylactic systemic anticoagulants, such as warfarin or low-dose aspirin, solely for the purpose of preserving or enhancing central venous catheter patency, citing insufficient evidence to support a beneficial effect on catheter function [11]. When supplementary heparinization or flushing with normal saline fails to reestablish adequate blood flow through the catheter lumen, removal of the catheter is indicated in cases of lumen thrombosis [26]. When early removal of an NTC is not feasible, conversion to a tunneled cuffed catheter is often pursued because TPCs are associated with lower infection rates, have demonstrated longer catheter survival, and offer better overall patency beyond approximately six weeks of use compared with NTCs [40].

Strategies to prevent hemodialysis catheter dysfunction focus on both thrombosis prevention and infection control, including appropriate catheter positioning, selection of catheter type or design, and the use of evidence-based lock solutions such as citrate or targeted thrombolytic locks in selected high-risk patients [14,41]. In addition, multifaceted catheter-care bundles that emphasize optimal insertion techniques, meticulous maintenance, and timely catheter removal have been shown to significantly reduce rates of both early and late catheter dysfunction in the hemodialysis population.

The most plausible explanation for this discrepancy is that our study predominantly involved NTCs, which have a substantially shorter average duration of use compared with TPCs. Consequently, these devices are more likely to be removed promptly at the earliest indication of treatment failure or the development of complications, and thus, an NTC has a much lower chance of developing a second or third complication compared to a TPC. Although our study did not formally test the two-week time cut-off, this finding does not contradict the recommendation of the KDOQI guideline. It is to note that the recommendation was based on expert opinions, synthesized from clinical experience, observational data, and cumulative indirect evidence. They suggested that non-tunneled internal jugular central venous catheters may be used primarily as temporary vascular access for a limited duration, typically less than two weeks or in accordance with institutional policy, to mitigate infection risk [11].

The main message of our study on hemodialysis vascular access, which addresses overall complications, can be summed up by a recommendation that temporary catheters be used for <2 weeks. Although this approach remains supported by evidence-based recommendations for dialysis access, it may not be optimal for all patient populations, particularly those with terminal illness or advanced chronic conditions, in whom it may adversely affect quality of life or life expectancy. Therefore, individualized selection of the most appropriate vascular access modality should involve a multidisciplinary team, including vascular surgeons, nephrologists, primary care physicians, and other relevant stakeholders.

Future directions in the use of NTC should move beyond rigid time-based thresholds and instead incorporate modifiable, device-related factors that influence infection risk. Emerging evidence suggests that advances in catheter sealing cap technology can significantly reduce blood backflow and intraluminal contamination, thereby potentially lowering the risk of CRB during short-term use [42]. Recent bench studies have demonstrated that different sealing caps vary substantially in their ability to prevent backflow, highlighting the importance of device selection in infection prevention strategies [42,43]. In parallel, the use of hub protection devices has gained increasing attention, with narrative reviews indicating a meaningful reduction in catheter-related infections among dialysis patients through improved hub disinfection and barrier protection [42,43]. These technological innovations suggest that the infection risk associated with NTCs is dynamic and modifiable rather than solely dependent on the duration of catheter placement. Consequently, reliance on a single universal time cut-off for NTC use may have limited generalizability across clinical settings with differing access to advanced catheter technologies. Future clinical guidelines should consider integrating device-specific factors and evolving preventive technologies when defining optimal use and dwell time for non-tunneled dialysis catheters.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis that has examined the duration of temporary catheter insertion before the occurrence of common complications. We acknowledge several limitations in this study. First, the number of catheters included was low. During study screening, we observed that many studies did not report the occurrence time of complications. Second, the analyses showed high heterogeneity. Although subgroup analyses have been conducted, there are still other factors that could not be accounted for. For example, variation in the methods of catheter insertion and the use of different sealing caps and Hub Devices were not reported in detail in each included study. Third, we could not analyze the effect of antibiotic use on the occurrence time of infection, as the data were insufficient. Fourth, it should be noted that restricting inclusion to studies reporting time to complications may introduce selection bias towards studies originating from centers with better documentation practices or studies with a specific research focus. This methodological consideration may limit the generalizability of the findings. Finally, the use of means as an outcome may only serve as a simple measure. This outcome was calculated only among those with events and excluded those who did not experience events, and thus did not represent population-level time-to-event metrics. Analysis in the form of a time-to-event outcome could not be conducted as the data were limited.

5. Conclusions

Among patients who developed complications, the mean time from temporary catheter insertion was two weeks to the occurrence of catheter-related infection and one week to mechanical complications. Consistent with the recommendation by the KDOQI guideline, which is based on expert opinions, limiting the duration of catheterization to less than two weeks is generally associated with a lower risk of catheter-related complications, thus supporting the consideration of catheter removal or exchange within this time frame. The current findings may provide a basis of evidence to strengthen future recommendations on the management of temporary dialysis catheters. However, it is important to note that these time cut-offs serve only as an approximation rather than definite summary values. Time to complications may vary within certain ranges. Further large multi-center studies are still required to identify the occurrence time of complications in temporary hemodialysis patients, given future advances in infection control and better catheter materials with insertion methods that may reduce the risk of mechanical complications. Additionally, future management of NTC should move beyond fixed time-based thresholds by incorporating modifiable device-related factors, such as advanced sealing caps and hub protection devices, that dynamically influence the risk of complications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/kidneydial6010007/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 checklist used to guide reporting of the systematic review; Table S2: Detailed database search strategies applied to identify eligible studies; Table S3: Quality assessment of included observational studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale; Table S4: Summary of catheter-related infection outcomes across included studies; Table S5: Summary of catheter-related mechanical complication outcomes across included studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K.A.S. and B.S.W.; methodology, I.K.A.S. and B.S.W.; software, B.S.W. and A.P.W.; validation, I.K.A.S., B.S.W. and A.P.W.; formal analysis, I.K.A.S. and B.S.W.; investigation, I.K.A.S. and B.S.W.; resources, I.K.A.S. and A.T.; data curation, I.K.A.S. and B.S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.A.S. and B.S.W.; writing—review and editing, I.K.A.S., B.S.W. and A.T.; visualization, I.K.A.S. and B.S.W.; supervision, A.T.; project administration, I.K.A.S.; funding acquisition, I.K.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study’s funding was supported by the LPDP—Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education Agency.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

AKI: acute kidney injury; AVF: arteriovenous fistula; AVG: arteriovenous graft; CAD: coronary artery disease; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CABSI: catheter-associated bloodstream infection; CI: confidence interval; CKD: chromic kidney disease; CRB: catheter-related bacteremia; CRBSI: catheter-related bloodstream infection; CVC: Central Venous Catheterization; DM: diabetes mellitus; DOPPS: dialysis outcome and practice patterns study; ESRD: end stage renal disease; F: female; HTN: hypertension; KDOQI: Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative; M: male; MC: mechanical complications; MeSH: Medical Subject Headings; NKF-DOQI: National Kidney Foundation-Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative; NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; NTC: non-tunneled catheter; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses; PVD: peripheral vascular disease; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RoB 2: Risk of Bias 2; SE: standard error; TPC: tunneled permanent catheters; USRDS: United States Renal Data System.

References

- Pisoni, R.L.; Young, E.W.; Dykstra, D.M.; Greenwood, R.N.; Hecking, E.; Gillespie, B.; Wolfe, R.A.; Goodkin, D.A.; Held, P.J. Vascular access use in Europe and the United States: Results from the DOPPS. Kidney Int. 2002, 61, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masnic, F.; Resic, H.; Dzubur, A.; Beciragic, A.; Coric, A.; Prohic, N.; Tahirovic, E. Factors associated with the initial vascular access choice and median utilization time in hemodialysis patients. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2025, 112, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lok, C.E.; Huber, T.S.; Cheff, A.O.; Rajan, D.K. Arteriovenous access for hemodialysis: A review. JAMA 2024, 331, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Hagai, K.; Nacasch, N.; Grupper, A.; Shashar, M.; Allon, M. More than a last resort: The role of tunneled catheters in hemodialysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, R.N.; Collins, A.J. The USRDS: What you need to know about what it can and can’t tell us about ESRD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, K.L.; Gilbertson, D.T.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Roetker, N.S.; Ku, E.; Schulman, I.H.; Greer, R.C.; Chan, K.; et al. US renal data system 2023 annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 83, A8–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allon, M.; Zhang, Y.; Thamer, M.; Crews, D.C.; Lee, T. Trends in vascular access among patients initiating hemodialysis in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2326458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polkinghorne, K.R.; McDonald, S.P.; Atkins, R.C.; Kerr, P.G. Vascular access and all-cause mortality: A propensity score analysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.J. Acute dialysis catheters. Semin. Dial. 2001, 14, 432–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NKF-KDOQI. Clinical practice guidelines for vascular access. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2006, 48, 176–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for hemodialysis adequacy: 2015 update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 66, 884–930, Erratum in Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 67, 534.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, C.E.; Huber, T.S.; Lee, T.; Shenoy, S.; Yevzlin, A.S.; Abreo, K.; Allon, M.; Asif, A.; Astor, B.C.; Glickman, M.H.; et al. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for vascular access: 2019 update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 75, S1–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, D.; Kaufman, J.S. Catheter first: The reality of incident hemodialysis patients in the United States. Kidney Med. 2020, 2, 242–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, B.; Lok, C.E.; Moist, L.; Polkinghorne, K.R. Strategies to prevent hemodialysis catheter dysfunction. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2025, 36, 952–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumovic, R.T.; Jovanovic, D.B.; Djukanovic, L.J. Temporary vascular catheters for hemodialysis: A 3-year prospective study. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2004, 27, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoglu, S.; Akalin, S.; Kidir, V.; Suner, A.; Kayabas, H.; Geyik, M.F. Prospective surveillance study for risk factors of central venous catheter-related bloodstream infections. Am. J. Infect. Control 2004, 32, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijmer, M.C.; Vervloet, M.G.; TerWee, P.M. Compared to tunnelled cuffed haemodialysis catheters, temporary untunnelled catheters are associated with more complications already within 2 weeks of use. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2004, 19, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inrig, J.K.; Reed, S.D.; Szczech, L.A.; Engemann, J.J.; Friedman, J.Y.; Corey, G.R.; Schulman, K.A.; Reller, L.B.; Fowler, V.G. Relationship between clinical outcomes and vascular access type among hemodialysis patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 1, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.; Gravel, D.; Johnston, L.; Embil, J.; Holton, D.; Paton, S.; The Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program; The Canadian Hospital Epidemiology Committee. Incidence of bloodstream infection in multicenter inception cohorts of hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Infect. Control 2004, 32, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaze, F.F.; Ashuntantang, G.; Halle, M.P.; Kengne, A.P. Outcomes of non-tunneled non cuffed hemodialysis catheters in patients on chronic hemodialysis in a resource limited Sub-Saharan Africa setting. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2014, 18, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaud, B.; Fouque, D. European recommendations for good practice in hemodialysis: Part two. Nephrol. Ther. 2008, 4, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Luo, D.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.T.; Lin, L.; Chu, H.; Tong, T. Optimally estimating the sample standard deviation from the five number summary. Res. Syn. Methods 2020, 11, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero, R.C.; Abad, M.D.C.; Cuesta, R.C.; Benítez, I.M.; Delgado, M.C.M.; Cabello, L.S. Retrospective study of the complications of temporary catheters for haemodialysis. Rev. Soc. Esp. Enferm. Nefrol. 2011, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, M.; Ahmed, W. Frequency of catheter related blood stream infections due to indwelling temporary double lumen catheter with respect to duration of catheterization in hemodialysis patients. Proc. SZPGMI 2013, 27, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Filiopoulos, V.; Hadjiyannakos, D.; Koutis, I.; Trompouki, S.; Micha, T.; Lazarou, D.; Vlassopoulos, D. Approaches to prolong the use of uncuffed hemodialysis catheters: Results of a randomized trial. Am. J. Nephrol. 2011, 33, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, V.; Valson, A.T.; Mohapatra, A.; David, V.G.; Alexander, S.; Jacob, S.; Bakthavatchalam, Y.D.; Prakash, J.A.J.; Balaji, V.; Varughese, S. Fast and furious: A retrospective study of catheter-associated bloodstream infections with internal jugular nontunneled hemodialysis catheters at a tropical center. Clin. Kidney J. 2019, 12, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukuda, C.; Suriyakumara, V.; Samarathunga, T.; Liyanage, L.; Marasinghe, A. Non-tunneled haemodialysis catheter-related blood stream infections and associated factors among first time haemodialysis patients: A prospective study from a tertiary care hospital in Sri Lanka. BMC Nephrol. 2024, 25, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.B.; Jacob, A.M.; Prathapan, S.K.; Joy, S.A.; Kurian, K.; Balakrishnan, S.; Padmaraj, S.R.; Thomas, R. Microbiology and clinical outcomes of central venous catheter-related blood stream infections in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. J. Med. Allied Sci. 2022, 12, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafik, H.; Bahadi, A.; Aatif, T.; Sobhi, A.; Kabbaj, D.E. Bacteremia and thrombotic complications of temporary hemodialysis catheters: Experience of a single center in Morocco. Ibnosina J. Med. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 9, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, P.; Stirling, C.; Traynor, J.; Morris, S.; Mactier, R. A prospective observational study of catheter-related bacteraemia and thrombosis in a haemodialysis cohort: Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk association. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2010, 25, 1596–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrero, E.L.; Robledo, R.T.; Cuñado, A.C.; Sardelli, D.G.; López, C.H.; Formatger, D.G.; Perez, L.L.; López, C.E.; Moreno, A.T. Risk factors of catheter-associated blood stream infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282290. [Google Scholar]

- Sahli, F.; Feidjel, R.; Laalaoui, R. Hemodialysis catheter-related infection: Rates, risk factors and pathogens. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desra, A.P.; Breen, J.; Harper, S.; Slavin, M.A.; Worth, L.J. Aseptic technique for accessing central venous catheters: Applying a standardised tool to audit “scrub the hub” practices. J. Vasc. Access 2016, 17, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayan, A.; Boyce, J.M. 100% use of infection control procedures in hemodialysis facilities call to action. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 13, 671–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.J.; Callery, S.M.; Thorpe, K.E.; Schwab, S.J.; Churchill, D.N. Risk of bacteremia from temporary hemodialysis catheters by site of insertion and duration of use: A prospective study. Kidney Int. 2000, 58, 2543–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.R.; Yi, S.H.; Booth, S.; Bren, V.; Downham, G.; Hess, S.; Kelley, K.; Lincoln, M.; Morrissette, K.; Lindberg, C.; et al. Bloodstream infection rates in outpatient hemodialysis facilities participating in a collaborative prevention effort: A quality improvement report. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2013, 62, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, A.K.; Panhotra, B.R. Prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infections: An appraisal of developments in designing an infection-resistant ‘dream dialysis-catheter’. Nephrology 2005, 10, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, A. Can you recognize a patient at risk for a hypercoagulable state? JAAPA 2008, 21, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mahapatra, H.S.; Muthukumar, B.; Khrisnan, C.; Thakker, T.; Pursnani, L.; Binoy, R.; Suman, B.; Alam, M.M.; Jha, A.; Gupta, V.; et al. Comparative outcome of tunneledand non-tunneled catheters as bridge to arteriovenous fistula creation in incident hemodialysis patients. Semin. Dial. 2025, 38, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buetti, N.; Marschall, J.; Catho, G.; Timsit, J.F.; Mermel, L. Which trial do we need? Infectious and non-infectious complications of peripherally inserted central venous catheters and midline catheters. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 568–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, D.; Giustivi, D.; Langer, T.; Fiorina, E.; Gotti, F.; Rossini, M.; Brunoni, B.; Capsoni, N. Effect of different sealing caps on the backflow of short-term dialysis catheters: A bench study. J. Vasc. Access 2025, 26, 1717–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorina, E.; Giustivi, D.; Gotti, F.; Akyüz, E.; Privitera, D. The use of Hub Devices to reduce catheter-related infections in dialysis patients: A narrative review. J. Vasc. Access 2025, 26, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.