Abstract

Encouraged by the perceived success of new public management (NPM) in other nations globally, the Abu Dhabi government adopted this system of management after 2010. To date, limited research has investigated the advantages and disadvantages of NPM for both the organization and the employee. Thus, the purpose of this study is to assess the extent to which NPM influences employee behaviors, particularly focusing on any possible negative effects of NPM on employee work–life balance. An exploratory, inductive, qualitative research method was adopted, which involved a total of 42 semi-structured interviews, conducted in two rounds with 21 public sector managers in Abu Dhabi. It was found that the strategic objective of maximizing customer satisfaction increased the workload of most managers, and one-third of our research participants perceive that their work–life balance has deteriorated since NPM was adopted. However, removing levels from organizational hierarchies and increasing individual responsibilities were generally reported as motivating. Although studies undertaken in other countries have suggested a link between NPM and worsening employee work–life balance, this link does not always hold true among our participants. Indeed, most individuals reported high levels of loyalty toward their organization and high levels of organizational citizenship behaviors. The reasons for these positive outcomes are explained.

1. Introduction

The adoption of new public management (NPM) practices began in the early 1980s, in countries such as the United Kingdom (UK) and United States (US). NPM may be understood as a collection of strategies and techniques that are used to enhance productivity in the public sector [1]. NPM focuses on reducing bureaucracy and increasing accountability for results, and it involves adopting private sector management practices [2]. Accountability for results requires managers to establish goals and specify the outputs required to meet these goals [3]. In recent years, public sector organizations have operated in unpredictable and changing environments, hence the need for a management approach that enables rapid and effective responses to change. To ensure efficient and effective administration, and the smooth delivery of public services, managers are required to become less authoritarian and more interactive, allowing others greater autonomy and responsibility.

In the early 2000s, public sector organizations in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) recognized the need to modernize and streamline their structures and processes, in order to become more efficient and effective in satisfying the needs of the nation’s citizens. After 2010, a series of public sector reforms were undertaken in Abu Dhabi—the capital city and largest of the UAE’s seven emirates—which replaced the style of management characterized by hierarchy, regulations, and bureaucracy with one based on decentralization, performance standards, and efficiency maximization. While NPM focuses on maximizing customer satisfaction and minimizing costs, relatively little attention has been given to employee welfare [4]. The implementation of NPM typically leads to decreased staffing levels, heavier workloads, and increased monitoring of individual and departmental performance [5]. Such changes may result in employees experiencing increased stress and worsening work–life balance [6].

In Abu Dhabi, the adoption of NPM led to organizational structures being simplified and employees receiving new job descriptions that gave them more responsibilities and accountabilities. A number of studies conducted in recent years have indicated that the UAE scores poorly for employee work–life balance when compared to other countries [7,8]. However, such studies have rarely distinguished between public and private sector employees, or specifically considered the impacts of NPM on the work–life balance and behaviors of managers, such as their staying/leaving intentions and organizational citizenship behaviors.

To date, limited research has investigated the advantages and disadvantages of NPM for organizations and employees. The purpose of this study is to assess the extent to which NPM influences employee behaviors, particularly focusing on any possible negative effects of NPM on employee work–life balance. The primary objective of the research is to analyze the implementation of NPM in Abu Dhabi with respect to managers’ perceived work–life balance, staying/leaving intentions, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The data collection was undertaken in two stages, so that before we examine managers’ behaviors (both planned and actual) we first understand how individuals’ jobs changed after the introduction of NPM. To achieve our research objectives, we specify four research questions, as follows:

- RQ1: What are the key characteristics of the system of management (NPM) implemented in Abu Dhabi’s public sector?

- RQ2: Has the system of management (NPM) implemented in Abu Dhabi’s public sector impacted upon the work–life balance of managers?

- RQ3: Does the work–life balance of managers in Abu Dhabi’s public sector influence individuals’ organizational citizenship behaviors?

- RQ4: Does the work–life balance of managers in Abu Dhabi’s public sector influence individuals’ staying/leaving intentions?

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The literature review provides concise summaries on NPM, work–life balance, organizational citizenship behaviors, and employee turnover intentions, which is followed by an overview of our theoretical frame. Then, in the method section, we explain our research design and sampling process. Following this, we present our findings, before concluding with a discussion and conclusion that highlights the study’s main findings and their implications for theory and practice.

2. Literature Review

2.1. New Public Management (NPM)

NPM differs from traditional public management practices in a number of ways. First, while traditional approaches involve centralized decision-making and control, NPM uses divisionalized units that are organized around products or services. Second, while relationships are characterized by unspecified and open-ended agreements in traditional approaches, NPM prefers a contract-based approach [9]. Third, in terms of budgeting, rather than maintaining stable budgets, NPM seeks to maximize efficiency and minimize resource use [10]. Fourth, while traditional approaches adopt qualitative and implicit standards, NPM is based on explicit standards and targets that are clearly defined [9].

NPM was introduced as a means to tackle perceived weaknesses of traditional management approaches that were characterized by minimal accountabilities, high costs, and low levels of satisfaction among the service users [1]. Concepts such as service quality and customer service, which require flexibility and rapid responsiveness, are key concepts of NPM, which are replicated from the private sector to improve the quality of public services [11]. Since NPM seeks to achieve superior service quality, managers are required to engage in continuous monitoring of the outputs, which are used as the basis for assessing the success of the organization [12]. Furthermore, services must be delivered efficiently and at minimal cost.

Research has indicated that NPM may be effective in improving efficiency, productivity, and cost minimization, although it is not without drawbacks [13]. The focus on pursuing short term goals may be detrimental to organizations in the long term. The permanent downward pressure that NPM exerts on budgets may result in long-term resource depletion [14], and the strong emphasis on costs and outputs may divert the attention of decision-makers away from the final impacts on the end user and society in general [15]. Furthermore, while bureaucracy may fail to ensure organizational effectiveness, it scores well in terms of securing equity and due processes compared to the majority of NPM related reforms [16].

Efficiency and productivity may be maximized in organizations by promoting competition among employees. Performance-related pay is common under NPM. Decentralization and smaller workforces have resulted in employees having more autonomy, but also more responsibilities and accountabilities. In many cases, individuals may feel stressed and over-worked, which may lead to job dissatisfaction and thoughts of leaving the organization for a new employer [17]. However, the links between NPM and employees’ work–life balance and actual and intended behaviors are not well established.

2.2. Work–Life Balance (WLB)

Work–life balance (WLB) is a concept that has always existed, yet one universally accepted definition for it does not exist [18]. In its broadest sense, WLB may be regarded as an individual’s happiness and ability to function effectively both at work and at home [19]. Hill et al. [20] describe WLB as the ability to fulfill all mental, behavioral, and time demands from paid work, personal, and family obligations at the same time. It is essential for most individuals to achieve a balance between their working and personal lives, where role conflict between the two is minimized [21]. However, what two individuals may consider a ‘good balance’ could vary quite considerably depending upon their career and life goals, and their family values [22]. When the introduction of NPM leads to lower staffing levels, enlarged job roles, and increased monitoring, the individual’s WLB may worsen.

In the past, women have tended to be the focus in WLB studies, but nowadays the concept is applied equally to both sexes, and to employees at all levels in the organizational hierarchy [23]. Additionally, in recent years, the concept of non-work life has broadened, to now include leisure, recreation, hobbies, and other personal matters in addition to family life [24]. Spillover theory describes how jobs may affect families and vice versa [25]. Spillover effects may be positive or negative, and feelings, moods, and satisfaction may be transferred between the workplace and home. For example, a spillover may occur when work-related stress that can be attributed to role overload leads to negative impacts on the individual’s personal life, such as their marital relationship.

Resource drain theory explains how individuals are affected by their scarcity of time, energy, and money, which may lead to psychological conflicts and role overload [26]. On the other hand, enrichment theory demonstrates the significance of instrumental sources such as experiences, skills, abilities, and values, or even productive sources of mood and satisfaction [25]. Allis and O’Driscoll [27] reported that satisfactory levels of WLB may have a positive effect on an individual’s mental health and general wellbeing. The resultant spillovers may include enhanced productivity and increased loyalty to the organization. In contrast, Lingard et al. [28] found that excessive workloads contribute negatively to WLB and lower quality work. Additionally, when WLB is perceived as poor, individuals are more likely to be dissatisfied with their job and less likely to engage in extra-role behaviors [29], but more likely to consider changing their employer or job [30]. When employees have a good WLB, they are more likely to be satisfied and happy in their job, and when they are happy, they are more likely to be motivated, engaged, and productive, and produce higher quality work [31]. Thus, employers have a direct interest in ensuring that their employees have a good WLB.

2.3. Organizational Citizenship Behaviors (OCB)

Employees often go beyond the call of duty and perform extra-role behaviors that are not part of the formal requirements of their job, and for which they are not directly rewarded. These extra-role behaviors are often referred to as organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB). Organ [32] identified five dimensions of OCB, namely altruism, sportsmanship, conscientiousness, civic virtue, and courtesy. OCB are discretionary behaviors of the individual that benefit the organization and contribute to the achievement of organizational goals [33]. Nevertheless, OCB may be directed at the organization or at the individual through person-to-person interactions [33]. With public organizations facing greater scrutiny from politicians and administrators, and greater performance expectations from citizens, while operating with smaller budgets and workforces, it has become common for such organizations to rely on OCB and the goodwill of employees [34].

In a systematic literature review of OCB in the public sector, De Geus et al. [33] found that the employee characteristics of organizational commitment, public service motivation, and job satisfaction are the factors that most likely lead to OCB, while stress is the most likely barrier that deters the individual from engaging in OCB. Similarly, individuals who perceive that they have a poor WLB may not feel that they have the time to engage in OCB. OCB may also be encouraged by job characteristics such as goal clarity and job autonomy, and organizational characteristics such as good leadership, interpersonal justice, procedural justice, distributive justice, organizational support, and psychological empowerment. Biygautane and Al-Yahya [35] found that employee engagement in organizational and social activities are strongly influenced by WLB. Thus, it follows that if NPM objectives and processes result in a worse WLB, OCB are likely to be lower. WLB shares close relationships with national cultural values—which are strong in the Arab world—as it requires employees to fulfil their duties in accordance with the organization’s expectations, societal expectations, religious obligations, and expected ethical standards of citizens [36]. Increasingly, public sector organizations have developed the private sector culture where job survival requires the individual to be ruthlessly hard-working and efficient while working with shrinking budgets and resources [37].

2.4. Employee Turnover Intentions

When employees feel stressed and do not enjoy their job, and when they do not feel adequately valued and rewarded, they are less likely to have feelings of loyalty toward their employer [38]. Thus, if the adoption of NPM objectives and processes increases workload, job responsibilities and stress levels, individuals’ loyalty towards their organization may decline. When WLB worsens, so may job satisfaction, leading to higher employee intentions to quit. Most public organizations avoid having high levels of labor turnover. Employee turnover has consequences that are not limited to financial implications, as it may lead to inferior organizational performance, lower productivity and morale among remaining employees, service disruptions, and customer dissatisfaction [39]. In relation to productivity, Hausknecht and Holwerda [40] found that high turnover impedes the proficiency of the remaining employees due to issues such as changes in workload allocation and the need to adapt to changing task demands. Research also indicates that replacing employees with inexperienced new hires has substantially negative impacts on service quality and standards of customer service [41].

Not all employees who experience low WLB are able to leave their jobs. For example, older employees may be reluctant to leave their jobs due to the negative impact it would have on pension payments [29]. In such a case, the employee displays continual commitment but lacks affective commitment. By definition, continuance commitment describes a state in which the employee’s decision to stay with a given organization is only as a result of the perceived inability to find better alternatives and the perceptions of negative consequences that would follow after leaving. In contrast, affective continuance revolves around commitment to the organization that emanates from emotional attachment to and involvement with the organization. The dimension of affective continuance is considered to have better organizational outcomes, such as higher productivity among employees [42].

While an increasing number of organizations recognize potential benefits of NPM and the importance of WLB and its possible negative effects on individual and organizational performance, OCB, and employee turnover, they may face a number of barriers and challenges, both internal and external to the organization, which make it difficult to improve employees’ WLB. Internally, an organization culture that expects and rewards long working hours and high organizational commitment while abandoning other life commitments contributes towards low WLB. As an external factor, De Cieri et al. [43] for found that public organizations are facing increased demands from stakeholders such as customers, administrators, and politicians, while the organizational resources to meet such demands are fewer. In the process, organizations tend to employ fewer employees and also adopt participative structures leading to increased workloads, worsening WLB, and higher employee turnover. Furthermore, contemporary organizations are characterized by high levels of workforce diversity in dimensions such as age, ethnic background, religion, and family responsibilities, which requires organizations to effectively engage in diversity management so that WLB strategies satisfy every individual’s needs [44].

The adoption of NPM objectives and processes may result in increased job demands, reduced resources, and increased stress levels, which may each have a negative impact on WLB, OCB, and employee turnover intentions. Thus, OCB and turnover intentions may be negatively influenced by increased job demands, reduced resources, and increased stress levels and/or poorer WLB. However, in this study, we focus on the relationships between NPM and WLB, and WLB and OCB.

2.5. Theoretical Frame

Public choice theory constitutes a central theory of the NPM model. The theory suggests that voters in a given nation remain centered to economic egocentricity, whereas interest groups remain rent seekers. In the context of public services, the public choice theory proposes that since individuals are self-seeking, public agencies should operate structured decision rules. When managerial decision rules are applied, there are higher chances that allocation decisions may be made in ways that reflect greater responsiveness to societal preferences [45]. In contrast, public interest theory suggests that decision making in government is to a large extent based on unselfish benevolence not only by elected representatives but also by full-time government employees [46]. Thus, public servants may be largely motivated by the need to maximize societal welfare.

In the context of normative institutionalism, individuals are geared towards the achievement of collective goals, which are embedded in intricate series of relationships with other individuals and collectives. In the context of public sector organizations, principal-agent theory explains that the provision of public services involves principal-agent relationships, where citizens are the main principals and the government is the major agent [47]. All relationships between the principals and agents are characterized by trade-offs on the part of the agent, and the agent possesses superior information about tasks, resources, costs, and operational performance. The NPM model may overcome some principal-agent problems through decentralization and competitive initiatives, such as partnerships with the private sector, which may reduce information asymmetry among the citizens and government, and the likelihood of low-quality service provision [48]. In this study, the citizen’s opinions and satisfaction are considered vital in deciding how the state runs the public sector organizations and how employees perform their jobs.

3. Method

3.1. Research Design

The primary aim of this research is to evaluate the implementation of NPM in Abu Dhabi’s public sector, and identify the effects of working in a NPM environment on managers’ WLB, OCB, and turnover intentions. In order to achieve this aim, the study adopts an exploratory, inductive, qualitative research design involving semi-structured interviews. This approach enabled the researchers to understand how human subjects make sense of their world and the experiences they have in it [49]. The study population is individuals employed in management positions in a public organization in Abu Dhabi. A purposive sampling strategy was adopted, to recruit participants who could provide in-depth and detailed information about the phenomena under investigation. To ensure sample validity, only credible and trustworthy informants were recruited, according to predefined criteria that included having worked in the Abu Dhabi public sector for at least ten years and holding the same position for at least five years. These criteria ensure that participants have substantial managerial experience, and that they witnessed first-hand the organizational changes brought about by the shift from traditional management approaches to NPM.

The study’s data were collected in two rounds of interviews, approximately three months apart, which resulted in every research participant being interviewed twice. The first interview collected data only on how the individual undertakes their job, noting changes that occurred after the introduction of NPM. Thus, the first interview was only concerned with answering the study’s first research question about the key characteristics of the system of management (NPM) implemented in Abu Dhabi’s public sector. Then, the second interview investigated the extent to which each individual perceived that new working methods, i.e., the changes brought about by adopting NPM, impacted upon their WLB, and, if WLB has changed, how this impacts upon their OCB and staying/leaving intentions. Thus, the second interview answers the study’s second, third, and fourth research questions. Collecting the data in two interview rounds helped ensure the reliability of the data, as it avoids biases that would more likely be caused if participants understood more clearly our hypothesized link between the adoption of NPM and worsening WLB, and the consequences of worsening WLB on OCB and turnover intentions. This research approach led to high levels of consistency among participants’ responses, which assured the quality of the data and the interpretation of it, making possible replicability of the findings more likely [50].

Two interview guides were developed for the two interview rounds, informed by the literature, and designed to answer the study’s research questions. The first interview guide consists of fourteen questions, with additional prompt questions. Examples of questions include To what extent does your organization focus on satisfying customers’ needs?; How does your organization satisfy customer needs?; Does your organization focus on becoming more efficient? If yes, what does it do to increase efficiency?; Has your level of responsibility increased in recent years? If yes, how, and why?; Do you have to work to performance targets?; and Do you spend a lot of time monitoring work performance and processes? Please give examples and details. The second interview guide has nine questions, also with additional prompt questions. Examples of questions include To what extent does your work life affect your personal and family lives?; Do you think that you have a poor or unsatisfactory work–life balance? If you think it is poor or unsatisfactory, what do you think is the cause of this?; Do you volunteer to do tasks that are not strictly part of your job? Please explain why or why not; Have you ever thought about leaving your organization? If yes, why?

A pilot study was undertaken with three managers employed in public organizations in Abu Dhabi, to ensure the validity and reliability of the survey instruments. The pilot study interviewees did not participate in the final study. The two interview guides worked well with each of the three pilot participants, who answered the questions openly and in considerable detail. Hence, no notable modification of the interview guides was necessary.

3.2. Sample

The sample size was not determined a priori; rather, interviews were conducted until the researchers were satisfied that data saturation had been achieved. As a result, 21 managers employed in a public organization in Abu Dhabi were each interviewed on two occasions, approximately three months apart. Thus, 42 interviews were conducted in total (see the Supplementary File for the participant details). As the study participants were all managers, the youngest was 32 years of age and the mean age was 40.3 years. Of our 21 participants, 17 were male and 4 female. The bias towards males is not representative of the organizations’ workforces, but it was difficult for the male researchers to secure female volunteers. UAE nationals accounted for 16 of the participants, with the remainder being expatriates. No noticeable differences in the perceived WLB of the UAE nationals and expatriates was observed. All of the participants were married and living as part of a family, which is normal for individuals aged over 30 in the UAE. Thus, each individual agreed that they had family responsibilities, which typically translates to caring for their spouse as well as children and/or parents.

3.3. Data Analysis

The research was conducted as an empirical enquiry that focuses on the lives and practices of the study participants as told through their own stories and narratives. Thus, the study adopted a narrative research strategy [49], where participants shared their experiences and attitudes toward NPM from the perspectives of WLB, OCB, and loyalty, as indicated by staying/leaving intentions. The narrative approach provided a rich insight into the participants’ daily life experiences and their thoughts and responses to these experiences. The data were analyzed using a process of thematic analysis, supported by the NVivo software. Thematic analysis enabled the researchers to make sense of the attitudes, opinions, and experiences that were communicated by the participants in the interviews [51]. The researchers followed Braun and Clarke’s [52] six stage process for thematic analysis, starting with familiarization and concluding with interpretation. The resulting themes were not defined a priori, and were only generated inductively from the raw data.

4. Findings

The Supplementary File provides an overview of the research findings.

4.1. Implementation of NPM in Abu Dhabi’s Public Sector

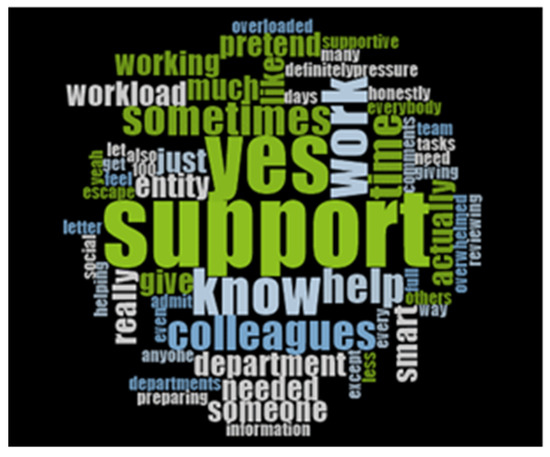

In the first round of interviews, participants were asked questions regarding the organizational structure, culture, and processes, to discover the extent, and how, NPM has been implemented in Abu Dhabi’s public organizations. Our participants unanimously agreed that the application of NPM principles in Abu Dhabi’s public organizations has contributed towards achieving superior levels of efficiency and productivity, while delivering higher quality services to citizens. Although all participants reported that providing high quality services and achieving customer satisfaction are objectives of their organization, the emphasis is stronger in organizations that more strongly apply NPM principles. The focus on serving customers is illustrated by the word cloud (Figure 1), generated using the NVivo software.

Figure 1.

Word cloud depicting organizational objectives.

While some organizations use traditional service management approaches such as measuring customer feedback in a reactive manner to ensure customer satisfaction, others use proactive measures which require employees to go ‘above and beyond’. To satisfy customers, organizations need to be efficient and flexible, able to deliver rapid responses for customers in times of crisis or service failure. All of the organizations aim to maximize efficiency (e.g., minimizing resource use, providing higher quality services) and productivity (e.g., maximizing output per employee or work team), at least to some extent. Additionally, cost minimization is a common objective. Sometimes, costs are reduced by stripping out a layer from the organizational hierarchy, giving individuals additional responsibilities, or outsourcing certain work tasks, activities, or services to private sector firms. However, some organizations are reluctant to outsource, mainly because of concerns over quality and control/monitoring.

Organizations have developed diverse communication channels that enable customers to easily communicate their needs, wants, and expectations. However, there is a common feeling among our participants that stakeholders—customers, administrators, and politicians—have generally expected more to be achieved with less, which can be very challenging for employees to achieve. Some organizations have changed operational processes and invested in technology to improve service quality. Improving service quality and customer satisfaction are other key objectives in Abu Dhabi’s public organizations. For example, Participant 6 noted that their organization has implemented service automation to ensure that the customer experience is enhanced and streamlined, which has resulted in both higher service quality and customer satisfaction.

Efficiency is not just like a step we do. It’s a lifestyle and it’s a culture which takes honestly a long time and a huge amount of effort to influence the brain of the employees, the people around us, the people who we work with, the people who we provide our services to, to make sure that efficiency means a lot and it favorably benefits them in the first place. We achieve it by always following an analytical approach. We break down the issue to determine what kind of services and what kind of resources we need. There needs to be shared tools. Then we start to see what the value additions are, trying something out and filtering out something else. And then we benchmark, to see the efficiency with our customers, and assess whether we are meeting our targets. We do surveys. We meet. We engage. We talk about the effectiveness and then we try to again take user’s comments and suggestions on board and put them back again into the process and keep refining. (Participant 21)

Internal competition is generally encouraged between individuals and departments. Although such competition may add pressure to the workloads of individuals, some employees appreciate the culture of excellence, find it motivating, and welcome the opportunities for advancement and taking new responsibilities. Virtually all participants agreed that they work to performance targets and that individual and departmental performance is closely and regularly monitored. Virtually every participant agreed that their organization had a culture that encouraged excellence, to achieve efficiency, high service quality, and high levels of customer satisfaction. To an extent, the culture within Abu Dhabi’s public organizations reflects the emirate’s culture and objectives. Participant 14’s organization has continuously updated its processes and procedures, to make it more user and business friendly, in line with the Abu Dhabi 2030 Vision, a plan to make Abu Dhabi one of the easiest and most friendly places in the Arabian Gulf region to deal with business.

Competition keeps employees mentally fit and looking for better always. Life has little meaning if there is no competition to achieve the best. Likewise, at work, this concept is largely encouraged, largely emphasized. Management believes in the value of having competition. Of course, this increases the effort and the pressure on the employee to excel, but this is for healthy results and for good reasons. It’s needed because it drives the organization to be agile and fit, to deal with any arising circumstances, any arising challenge which happens. Ethical competition is helpful for the management, as it encourages teamwork to remove the barriers that may prevent us from reaching our targets. We don’t forget our mission and we don’t become busy pointlessly competing against each other. (Participant 3)

In 2012, we began measuring customer satisfaction through a third party. For the first time, we hired a company, it’s a global company, and they specialize in market research. So rather than us measuring our customers’ satisfaction, we hired them, as they use best practice methodology and we ensured that there is an objectivity in this. And since then this has been the case. By the way, in 2017, we won the ADAEP Award, which is the Abu Dhabi Excellence Award for Government Performance, for the customer satisfaction category. (Participant 9)

In summary, the key aspects of NPM mentioned by our participants as implemented in their organization are customer focus; going above and beyond; increasing efficiency and productivity; improving service quality; using private sector organizations; internal competition; performance standards; monitoring performance; and increased job responsibilities. The focus on improving service quality and customer satisfaction, often with fewer staff and resources, has put additional pressures on managers, with many working longer than their formal working hours.

4.2. Work–Life Balance in Abu Dhabi’s Public Sector

The second round of interviews focused primarily on the extent to which our participants perceived that the implementation of NPM had impacted upon their WLB, and the consequences of this on their OCB and staying/leaving intention. Two primary clusters were identified, which primarily differ based on whether good or poor WLB was reported. Cluster 1, consisting of 14 participants, represents managers who have good or neutral WLB, and Cluster 2, consisting of 7 participants, represents managers who have poor WLB. Overall, one-third of our research participants perceive that their WLB has deteriorated since NPM was adopted. In addition to understanding managers’ low levels of WLB based on their job responsibilities and whether or not they are able to enjoy non-work activities as well as spend quality family time, the managers were also asked to rate their perception of WLB. This provided an objective benchmark against which to cluster the managers.

NPM approaches, which are evident in all Abu Dhabi public organizations, at least to some extent, are perceived by Cluster 1 participants to help individuals and departments to organize and perform their work more efficiently and to a higher standard. Cluster 1 participants, who do not perceive poor or unsatisfactory WLB, typically believe that work pressures and additional demands on their time are the result of rising the organizational hierarchy, which involves accepting new tasks and responsibilities, rather than as the result of new NPM working methods. For example, new work tasks and responsibilities include participation in strategic decision making and developing operational plans. The managers in Cluster 1 generally believe that the NPM style of management is best for the organization and its customers, and they mostly enjoy working with NPM methods. These individuals reported that the removal of levels from organizational hierarchies and increasing individual responsibilities are generally motivating, as they offer new opportunities for career enrichment and advancement.

Although the Cluster 1 participants acknowledge that NPM work methods may increase workloads and responsibilities, these individuals are less likely to perceive a negative influence on their own WLB. However, WLB is determined not only by the individual’s job but also their family and non-work situations, e.g., responsibilities for caring for children and other family members, and their recreational/leisure interests and hobbies. Some managers made it clear that their perception of a reasonable WLB is influenced considerably by their non-work situation. In other words, if they had more family responsibilities or hobbies that required time, then their WLB would be less satisfactory. On the other hand, career-focused individuals who derive pleasure and satisfaction from their work may have less need for out-of-work hobbies and interests, hence their WLB is judged positively.

In this organization, you never work enough. But it’s fun. I’ve never feel stressed, even when I have many tasks to deal with at the same time, mainly because they are all interesting. Every task needs to be completed on time and to a high quality standard, and sometimes as part of a team, not only as one individual manager. I enjoy being busy with a heavy workload. It’s better than sitting in my office and waiting for somebody to ask for something. For me, I am really… I wouldn’t say overloaded, but obviously I am loaded enough. (Participant 5)

Managers in Cluster 2 perceive that they possess a poor or unsatisfactory WLB, and this is generally attributed, at least in part, to the new work methods introduced as part of the public sector reforms that adopted NPM structures, processes, and principles. Participants in this cluster perceive that they are expected to achieve more and higher quality output with fewer staff and resources. These individuals repeatedly alluded to the fact that the extensive focus on performance management and reporting is cumbersome and time-consuming, and with their other core work, a challenge. Key performance indicators (KPIs) establish each organization’s objectives, and individual and department performance is assessed against the KPIs. The KPIs themselves are often established according to the demands, or perceived demands, of the service users. Some managers perceive that nowadays the demands and expectations of customers are often unrealistic and unreasonable, putting a lot of pressure on the staff in public organizations. Several managers confessed to constantly feeling under pressure, which leads to stress, and sometimes to health issues. When work demands impact upon non-work activities and relationships, the lives of both the manager and their family are affected.

We have to report everything in a systematic manner to the management. Therefore, I spend considerable time ensuring that the reports I have to submit to the management are accurate and useful. Sometimes I have to continue working after the official working hours, to ensure that I can complete all of my work tasks and reports. I always have many tasks to do at the same time, so it is often a challenge to prioritize them and complete everything to a high standard. (Participant 1)

Year by year, we go through a new era. Now, it’s AI (artificial intelligence), its blockchain, and innovation. So, you need to adapt to the new technology, and you need to adapt to new ways of doing things, to deliver a service that will meet the high standards expected by our customers. Each year, our customers have become wiser and smarter. So, every year we review all of our KPIs, and devise new strategies to improve the KPI outcomes, which cover both our processes and our end services. Other organizations may focus on output, but output is never enough because it will not necessarily deliver customer satisfaction, or customer happiness. As I said, customer demands have become more and more. Customers have lots of expectations and every year there are new expectations. (Participant 2)

A key point to note is that while the industries in which our participants work varies from one manager to the next, their job roles have many similarities. For instance, there are several operations managers and customer relationship managers in the sample across the two clusters. Thus, the job role itself is not a key point of difference in the varying rates of WLB evidenced.

4.3. Consequences of Perceived Work–Life Balance

All of the managers in Cluster 1 displayed high or medium levels of OCB with respect to their organization and colleagues. These individuals have pride in their jobs and are motivated to do whatever is best for the customers and organization. Additionally, these managers recognize the importance of effective teamwork and high-quality internal customer service, where one individual and department supports another individual or department. OCB may be recognized among Cluster 1 participants as individuals who work beyond their formal working hours; undertake tasks and activities that better serve customers, e.g., supervising remedial actions after service failures; volunteer for special projects and new initiatives; offer suggestions to the organization to improve processes or services; and offer advice and support to colleagues to help them work efficiently in ways that benefit the individual, the customer, and the organization. Even though Cluster 1 managers may feel overworked, they are satisfied with their job, and both individual and organizational success is important to them. These individuals display loyalty to their organization and have not had any serious thoughts about leaving their employer. One participant said that they felt part of an organizational family, where mutually beneficial reciprocal offerings kept both the individual and the employer satisfied. Even though some individuals perceive that they are over-worked, they feel that the organization values, respects, and cares about them, and that such a work atmosphere may be difficult to find elsewhere.

Whenever I see a potential improvement area, I share it with the senior management. We have a good managing director, who welcomes all ideas. Actually, offering suggestions is one of the objective measurements set for the contributions of team members. Practically, I did some improvements in the reporting, and I did some improvements in the manuals by establishing criteria that were not there before. We are working towards establishing new systems that will help enhance all work processes, our coordination, our timing, our follow-up, our outcomes, and so on. In our area, there is not now much to do, but there is always a new area to be audited that’s different from the others, where I can offer advice and suggestions. We strive always for new solutions, new innovative things, new software that will help us. We don’t want to be followers, we want to be leaders, and training sessions help us to change the organizational culture and the ways we do things. Sometimes, I volunteer to help with training others. (Participant 5)

It was reported by our research participants, that the more an organization utilizes NPM approaches, the greater the demands on its employees. What varies among individuals is how they perceive the extra workload, the extent to which it leads to feelings of stress, and how it impacts on their perceived WLB. All participants in Cluster 2—who reported poor or unsatisfactory WLB—emphasized their intention or desire to engage in OCB wherever possible. This is illustrated by the OCB word cloud for the Cluster 2 participants (Figure 2). Each individual wants to do all that they can to help and support customers, colleagues, and the organization as a whole. However, in practice, some managers perceive that they simply do not have the time to engage in OCB. Overall, it seems that the more an organization utilizes traditional NPM approaches, the less likely that managers will be able to engage in OCB.

Figure 2.

Word cloud depicting OCB among the Cluster 2 participants.

Some participants commented on how they serve the country and its citizens. It is clear that both organizational and national cultures, which emphasize collectivism, teamwork, success, and winning, influence individuals, particularly the UAE nationals, to engage in OCB. Furthermore, human resource management that has moved away from nepotism and promotion based on position in society, to career advancement based on performance [53], has been motivating for employees and encouraged them to ‘go the extra mile’ through displaying OCB. Most of the managers in Cluster 2 admitted to at least having occasional thoughts of leaving their organization or changing their job, but in most cases these are not thoughts that will ever lead to action. Some less-satisfied individuals hope that their jobs will improve in the future, while others believe that other organizations are likely to be no better. Thus, employee loyalty is relatively high even among the managers with poor WLB.

Honestly, with so much workload, there’s very little time to actually support others. But if there are days when there’s not so much work, and someone in my own team or in my own department needed support, one hundred per cent I would give it. I can be very supportive towards others, and I also get support from others when I’m overwhelmed with work. What is most important is the service that we deliver to our customers, both external and internal. Also, I am expected to, and wish to, achieve my individual and departmental KPIs, for my own satisfaction and to maintain good relationships with my superiors. (Participant 18)

I’m not going to lie, I did think about leaving many times. But then when I hear about other places and other entities, and how their work structure is, and the way they work, I feel like I’m blessed in this company. In stressful times, at times when I feel I can’t take a break, and times where there’s a lot of pressure, and there’s no support, these are the times when I feel like, ‘Okay, I’m giving up. I need to leave. I need a job that is a bit less hectic, one that gives me a better work–life balance’. But then their words—the customers, my colleagues, and even the top managers—as well as the generally positive work environment, encourage me to stay. (Participant 8)

It is clear from Participant 8’s response that NPM objectives and processes may lead to additional work-related pressures and stress, but pleasure and job satisfaction resulting from things such as a positive work environment and good relationships with others may result in continued loyalty toward the organization.

5. Discussion

The primary aim of the study was to gain an understanding of the effects of NPM on WLB and consequent employee behavior, specifically with regard to OCB and job turnover intentions. More specifically, the objectives revolved around understanding the key aspects of NPM in the Abu Dhabi public sector, and how employee behavior in this sector has been affected by national and regional institutions, e.g., culture and values in the Arab Gulf region.

Our first research question is concerned with identifying the key characteristics of NPM that are implemented in Abu Dhabi’s public organizations. In particular, we considered how different the implementation of NPM is in Abu Dhabi compared to its implementation in Western countries such as the UK and US. Our participants unanimously agreed that the application of NPM principles in Abu Dhabi’s public organizations has contributed towards achieving superior levels of efficiency and productivity, while delivering higher quality services to citizens. However, the results reveal the presence of two types of implementation: traditional and innovative. The majority of the organizations featured in this research implement NPM in an innovative manner whereby the use of the private sector is limited to selected redundant services and contracts. Furthermore, while customer service is emphasized in these organizations, the steps taken towards ensuring the happiness of the customer are markedly different from organizations that implement NPM in its traditional entirety. For example, organizations adopting an innovative approach to NPM implementation use customer feedback to understand the needs of customers and develop proactive measures to ensure that every customer is satisfied.

It is not entirely clear what has prompted some organizations to implement NPM innovatively. This will require a deeper analysis of the cultural orientations and other organizational factors, which is outside the scope of this research. However, some stipulations for why some companies can implement NPM innovatively while others do not are discussed. First, it is possible that variations in NPM implementation may be attributed to the fact that, in the UAE each public sector organization is granted some degree of autonomy, giving it the power to make changes to its internal processes as it sees fit. Second, the organizational culture and dialogue that exists within an organization can help to account for this difference in the implementation of NPM wherein an organization that favors a more open and innovative culture may have implemented NPM innovatively. Third, the leadership governing the organizations may also play a role in the implementation of NPM. These parameters can be further explored by future researchers.

Although traditional NPM implementation also focuses on the customer, NPM has sometimes been criticized for its limited involvement of citizens, such that citizens have often been frustrated by the shallow participation efforts [54]. This limitation is not found in the implementation of NPM in Abu Dhabi’s public sector, as organizations actively involve customers in product and process design and delivery, and proactively try to resolve any potential issues that the customers may have. Furthermore, our participants observed that customer satisfaction with services and the organizations delivering them also extended to overall satisfaction with the government.

In the organizations that adopt an innovative implementation approach to NPM, our participants reported that efficiency as a whole is integrated into the strategic objectives of the organization to the extent that it influences the mind-sets of employees into seeking efficiency in work as a positive form of a contribution to the organization and to the country. Serving the country is perhaps something unique to the Arab Gulf culture, in comparison to Western cultures. In many Abu Dhabi public organizations, efficiency is not considered as an outcome, but rather a part of the organization’s culture, whereby everything is done with efficiency at its core.

Some organizations benchmark their performance against other countries, to reveal the differences and shortcomings in their internal and external services. Employees are involved in the performance evaluation process and given ownership to deliver solutions that will improve both efficiency and service quality. Most public organizations in Abu Dhabi have made tremendous progress in making most key services automatic or smart, where customers access services using as much technology as possible. This has resulted in smaller workforces, but it has not reduced the workload of employees or managers, who simply have new work tasks and responsibilities. The specification of KPIs gives managers clear targets to achieve, but working with limited resources often results in work overload and feelings of pressure and stress.

To answer our second research question about how NPM has impacted upon the perceived WLB of managers in Abu Dhabi’s public organizations, it was found that our participants can be organized into two clusters, with one group having good or acceptable WLB and one group having poor or unsatisfactory WLB. Individuals employed in organizations adopting the innovative approaches to NPM were more likely to be in the good WLB group, compared to individuals working in organizations implementing the traditional approaches. Individuals in the poor WLB cluster typically reported decreased staffing, increased responsibilities, heavy workloads, tougher KPIs, and increased monitoring of individual work performance, which often lead to feelings of overwork and stress. When individuals work several hours each week beyond their formal work hours, they are more likely to perceive that they possess a poor WLB.

Managers in the poor WLB cluster generally view performance management and monitoring as a burden and a huge task. It should be noted that these managers tend to work for organizations that have outsourced their key services to the private sector. These managers refer to performance monitoring and management as being external to their work, such that there is no integration of performance management and reporting responsibilities in their daily jobs. Furthermore, some managers indicated that their reporting responsibilities were very time consuming due to the requirement for an exorbitant amount of detail in the reporting of the progress on their work.

Although a manager’s WLB is determined in part by their organization’s structure, processes, and goals, as well as the individual’s specific work tasks and responsibilities and the resources and support provided to them, WLB is also shaped by the individual’s marital and family status and obligations for caring for family members, as well as their leisure and recreational interests and hobbies. The incomes of public sector managers in the UAE is such that many individuals employ home maids or nannies for their children, which may reduce the non-work demands on them.

From a theoretical standpoint, current research indicates that the NPM model has many elements that may provide job difficulties for managers of public organizations [11,14,37]. These obstacles may have an effect on a manager’s WLB. Ferris and Grady [48] claim that management models designed for the private sector often have limits in terms of their effectiveness when applied in the public sector. Private sector management methods may help achieve the desired efficiency and effectiveness, but before transferring them to the public sector, all problems influencing their acceptance and implementation must be thoroughly addressed. The basic assumption is that the two sectors are fundamentally distinct in terms of decision-making, problems of interest, and objective complexity. As a consequence, managers of public organizations are often under pressure to produce outcomes using a model that does not fully fit the public sector’s character [55].

Previous research has suggested that performance expectations under the NPM paradigm are often exaggerated and, in some instances, unreasonable [56]. Coles and Jones [56] also argue that NPM reform plans are often oversold, creating unrealistic expectations for efficiency improvements on the part of public agency management. Particular issues that limit the effectiveness of NPM include a lack of suitable performance measurement methods, institutional changes that are out of step with their settings, and a dearth of capacity development in the public sector. NPM methods such as contracting may fail to produce the anticipated advantages, and additional responsibilities may be placed on the managers. Thus, this research further extends the discourse that exists in terms of how NPM implementation leads to higher levels of job responsibilities, which may then lead to worsening WLB amongst managers. However, it was observed in this study that managers who welcomed additional responsibilities to achieve career growth and advancement, or as an indication of their success, tended to have superior perceived WLB.

Our third research question is concerned with how OCB are affected by WLB. The findings from this research are surprising and suggest that, even in the face of poor WLB, the OCB of most employees is not affected. In other words, participants from both clusters exhibit OCB, regardless of their WLB. It is important to understand why managers who have poor WLB still have good levels of OCB. Virtually all of our participants demonstrated a keenness to help both their organization and their colleagues. Regardless of their cluster, several participants showed an active interest in ensuring that their organization improves and better serves the end users. It is likely that in some cases an individual’s poor WLB is partially attributable to keen participation in OCB. In other words, the OCB may be part of the cause of low WLB.

Particularly in Cluster 1, several participants spoke about ‘going above and beyond’, to ensure that their organization moves forward as a whole. A similar belief is harbored by these participants with respect to helping their colleagues; they assist their colleagues because they believe that they are all part of the whole, and if their colleagues are impacted by something then they will also be impacted. The OCB of managers in Cluster 2 is focused more toward their colleagues than to the organization itself. Furthermore, the reasons why individuals provide support to colleagues also differs; managers in Cluster 1 often support their colleagues to empower them and help them succeed in their careers, while managers in Cluster 2 provide support to alleviate the work pressures that colleagues have.

The findings of this study are in stark contrast to previous research, which suggests that the various dimensions of poor WLB, such as lack of adequate time for social and personal commitments, are negatively related with OCB dimensions such as altruism and civic virtue [57,58]. One of the possible reasons for this could be the collectivist nature of the society in the UAE, whereby people expect to look after themselves and their immediate family members as well as others, compared to the degree of support received from social institutions [59]. National culture influences organizational culture through national cultural beliefs, norms, and values being imposed on organizations. This process occurs through societal establishment in which case organizations are compelled to adopt the dominant societal practices in order to achieve a good fit. Therefore, the societal practice of helping one another translates into workplace behavior where colleagues offer support to one another due to the collective nature of the society.

Another possible reason for this phenomenon is that the employees are expected not only to commit themselves to their work goals, but also to identify with their respective workplaces [60]. Individuals’ feelings of organizational identification may lead to high levels of OCB regardless of their WLB. Although top managers may be pleased that individuals from both clusters display OCB, it does not mean that they can ignore WLB issues. It may be considered unethical to demand workloads that impact negatively upon WLB, and having many individuals with poor WLB may impact upon the organization in other ways, such making the organization less attractive to potential new recruits.

Our fourth and final research question seeks to understand how turnover intentions are affected by WLB. It was observed that managers who have a good WLB have a lower rate of turnover intention whereas managers who have poor WLB are less loyal to the organization. This result was largely expected because it has been established in prior research [38,39,41,43]. However, the present findings support and extend the existing literature. In general, turnover intentions are higher among managers who have more demanding family responsibilities or family members who express dissatisfaction with the individual’s work demands. In summary, the findings of this research suggest that NPM implementation in Abu Dhabi’s public sector does have an effect on the WLB of the managers; however, how this impacts upon OCB and turnover intentions varies. Although it is good that employee turnover is relatively low among Abu Dhabi’s public sector organizations, the fact that some individuals even think about leaving suggests that top managers should be aware of this fact and implement actions that reduce such thoughts. However, it should be noted that individuals may contemplate leaving their organization for many different reasons, which may be unrelated to NPM or WLB, for example to pursue an opportunity that offers career advancement, or a new challenge or experience.

6. Conclusions

This research identified two categories of manager in Abu Dhabi public organizations: one that perceives good or acceptable WLB and where individuals have low turnover intentions, and a second where individuals perceive poor or unsatisfactory WLB and as a result may have higher turnover intentions. Both groups demonstrated reasonably high levels of OCB, for reasons that have been discussed. This study contributes to theory by identifying that there is a clear dichotomy between managers of innovative implementation of NPM relative to managers of organizations with traditional NPM.

Second, it was observed that managerial attitudes towards accepting new work tasks and responsibilities, and their overall outlook on the utility of competition, is also a determinant of WLB. This is an interesting finding and indicates that within the same public sector, differences in operationalizing NPM result in different outcomes. Creating an internal organizational culture that embeds efficiency at its core ensures that the managers work with the mind-set of efficiency in all of their work tasks and do not consider it as additional work that needs to be done. While the role of organizational culture has been established as a parameter in WLB, more research needs to be conducted on how managerial attitudes determine the extent of WLB in an organization. Moreover, when the private sector is fully outsourced, it imposes increased pressure on the managers because they have to oversee the performance of their subordinates as well as the private sector.

Third, the cultural and institutional profile of the UAE and the general attitude of the population towards bettering public services needs special mention. It was noted previously that the managers who have good WLB maintain a positive attitude in relation to additional and extra work and have high levels of OCB. However, it was noted that managers who have poor WLB, who may hold a generally negative disposition towards their work, still display OCB. This is perhaps indicative of the camaraderie between the people in the UAE and the collective nature of the society. In this case, the contribution is the understanding that the institutional makeup of a country influences the extent to which the NPM is implemented and the resultant impact it has on WLB, OCB, and loyalty of managers. This study also makes a conceptual contribution by creating new knowledge in the area of NPM in an Arab Gulf country that is markedly different from Western contexts, where most of the extant research is concentrated.

The fourth contribution of this study is that, by shedding light on the implementation of NPM in a nation that has considerable centralized economic planning, it has outlined an innovative and new manner in which NPM may be implemented, which results in higher citizen participation, greater focus on customer service, and greater emphasis on internal automation and efficiency, with a positive culture and attitude towards work and achievement, and with high levels of positive internal competition.

The main practical implication of the results is that the implementation of NPM need not follow the traditional approach, because when an innovative approach is applied to the implementation of NPM, it leads to greater employee-level benefits, such as superior levels of WLB, OCB, and loyalty, which may also enhance the individual’s productivity and job satisfaction. Therefore, organizations in the public sector need to adopt NPM in a unique and contextually appropriate manner, rather than simply applying all of its principles together without adaptation and customization.

The research is not, of course, without limitations. The study was undertaken with a relatively small sample in only one city, which may limit generalizability of the findings. Our proposed conceptual model—which links NPM with OCB and employee turnover intentions through WLB acting as a mediating influence—may in future be tested using quantitative data. Of course, in reality, there are other factors/concepts that may act as mediating variables in addition to WLB and future research can also investigate the explanatory power of such alternatives. The research design appeared to work well, but some participants questioned whether it was really necessary to collect the data in two rounds of interviews. The researchers maintain their original view that this approach helped minimize possible biases while gaining rich and detailed information from the participants, who appeared to share their attitudes, feelings, and experiences quite candidly.

Future studies could be conducted in different locations globally, and it could be investigated whether demographic features such as gender, age, nationality, and education level have an impact on perceived WLB, OCB, and loyalty. Finally, in line with the insights gained in the present research, future researchers may conduct a large-scale comparative case study comparing an Arab Gulf or Middle Eastern country with a Western nation, to analyze in greater detail the specific differences between the implementation of NPM in the countries. This will provide a deeper understanding of how emerging nations differ in comparison to the developed nations in their NPM implementation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/merits3010005/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.H. and S.W.; Methodology, A.A.H.; Formal analysis, A.A.H.; Data curation, A.A.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.A.H. and S.W.; Writing—review & editing, A.A.H. and S.W.; Supervision, S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethics policy of The British University in Dubai, and was approved by the University Ethics Committee on 22 July 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- Sue, Y. The new public management and tertiary education: A blessing in disguise for academics. N. Z. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2015, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, N.; Brower, A.; Duncan, R. New public management and collaboration in Canterbury, New Zealand’s freshwater management. Land Use Pol. 2017, 65, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, S.; Bordogna, L. Varieties of new public management or alternative models? The reform of public service employment relations in industrialised democracies. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2011, 22, 2281–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, G.A.; Kundi, G.M.; Qureshi, Q.A. Relationship between WLB and Organisational Commitment. Res. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 2224–5766. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, R.; Edwards, C.; Woodall, J. The new public management and managerial roles: The case of the police sergeant. Brit. J. Manag. 2005, 16, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, I.; Ackroyd, S.; Walker, R. The New Managerialism and Public Service Professions; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Denman, S. The Eternal Quest for the Perfect Work-Life Balance. The National, 3 June 2018. Available online: https://www.thenational.ae/lifestyle/comment/the-eternal-quest-for-the-perfect-work-life-balance-1.736096 (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Jabeen, F.; Friesen, H.L.; Ghoudi, K. Quality of work life of Emirati women and its influence on job satisfaction and turnover intention: Evidence from the UAE. J. Org. Chang. Manag. 2018, 28, 737–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Helden, G.; Hodges, R. Public Sector Accounting and Budgeting for Non-Specialists; Macmillan International Higher Education: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cambra-Berdún, J.; Cambra-Fierro, J.J. Considerations and implications on the necessity of increasing efficiency in the public education system: The new public management (NPM) and the market orientation as reference concepts. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2006, 3, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Slack, N.J. New public management and customer perceptions of service quality: A mixed-methods study. Int. J. Public Admin. 2022, 45, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felício, T.; Samagaio, A.; Rodrigues, R. Adoption of management control systems and performance in public sector organizations. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapuente, V.; Van de Walle, S. The effects of new public management on the quality of public services. Governance 2020, 33, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, T.; Budding, T. New public management’s current issues and future prospects. Financ. Account. Manag. 2008, 24, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsson, G. Accrual accounting in the public sector: Experiences from the central government in Sweden. Financ. Account. Manag. 2006, 22, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouban, L. Citizens and the New Governance: Beyond New Public Management; IOS Press: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Amour, N. The Difficulty of Balancing Work and Family Life: Impact on the Physical and Mental Health of Quebec Families; Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec: Sainte-Foy, QC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, J.L.; Higbee, J.L. An exploration of theoretical foundations for working mothers formal workplace social networks. J. Bus. Econ. Res. 2010, 8, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S. Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J.; Hawkins, A.J.; Ferris, M.; Weitzman, M. Finding an extra day a week: The positive influence of perceived job flexibility on work and family life balance. Fam. Relat. 2001, 50, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, T.; Hasluck, C.; Pierre, G.; Winterbotham, M.; Vivian, D. Work-Life Balance 2000: Results from the Baseline Study; Department for Education and Employment: Norwich, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Allen, T.D. Work–family balance: A review and extension of the literature. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology; Quick, J.C., Tetrick, L.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Brough, P.; Holt, J.; Bauld, R.; Biggs, A.; Ryan, C. The ability of work-life balance policies to influence key social/organisational issues. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Res. 2008, 46, 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.R.; Viswesvaran, C. Whistleblowing in organizations: An examination of correlates of whistleblowing intentions, actions, and retaliation. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 62, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.S.; Kotrba, L.M.; Mitchelson, J.K.; Clark, M.A.; Baltes, B.B. Antecedents of work–family conflict: A meta-analytic review. J. Org. Behav. 2011, 32, 689–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Pichler, S.; Bodner, T.; Hammer, L.B. Workplace social support and work–family conflict: A meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organisational support. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allis, P.; O’Driscoll, M. Positive effects of non-work-to-work facilitation on well-being in work, family and personal domains. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Brown, K.; Bradley, L.; Bailey, C.; Townsend, K. Improving employees’ work-life balance in the construction industry: Project alliance case study. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2007, 133, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Bozionelos, N. Work-life balance as source of job dissatisfaction and withdrawal attitudes. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, K.J.; Ison, S.G.; Dainty, A.R. The job satisfaction of UK architects and relationships with work-life balance and turnover intentions. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2009, 16, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, A.J.; Proto, E.; Sgroi, D. Happiness and productivity. J. Lab. Econ. 2014, 33, 789–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, KY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- de Geus, C.J.; Ingrams, A.; Tummers, L.; Pandey, S.K. Organizational citizenship behavior in the public sector: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Public Admin. Rev. 2020, 80, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Erez, A.; Johnson, D.E. The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biygautane, M.; Al-Yahya, K. Knowledge Management in the UAE’s Public Sector: The Case of Dubai. Dubai School of Government. In Proceedings of the Gulf Research Meeting Conference at the University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 6–9 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Deery, M. Talent management, work-life balance and retention strategies. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 20, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Davies, A. Theorizing the micro-politics of resistance: New public management and managerial identities in the UK public services. Org. Stud. 2005, 26, 683–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yucel, I. Examining the relationships among job satisfaction, organisational commitment, and turnover intention: An empirical study. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 7, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; George, R.T. Understanding the influence of polychronicity on job satisfaction and turnover intention: A study of non-supervisory hotel employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausknecht, J.P.; Holwerda, J.A. When does employee turnover matter? Dynamic member configurations, productive capacity, and collective performance. Org. Sci. 2013, 24, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmer, S.; Hillmer, B.; McRoberts, G. The real costs of turnover: Lessons from a call center. Hum. Res. Plan. 2004, 27, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, T.I.; Jam, F.A.; Akbar, A.; Khan, M.B.; Hijazi, S.T. Job involvement as predictor of employee commitment: Evidence from Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 6, 252–262. [Google Scholar]

- De Cieri, H.; Holmes, B.; Abbott, J.; Pettit, T. Achievements and challenges for work/life balance strategies in Australian organizations. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2005, 16, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P. The Next Society. The Economist, 3 November 2001. Available online: https://scholar.google.ae/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Drucker%2C+P.+%282001%29.+The+next+society.+The+Economist%2C+1.&btnG= (accessed on 22 January 2022).

- Denhardt, J.V.; Denhardt, R.B. The New Public Service: Serving, Not Steering; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hantke-Domas, M. The public interest theory of regulation: Non-existence or misinterpretation? Eur. J. Law Econ. 2003, 15, 165–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunleavy, P.; Hood, C. From old public administration to new public management. Public Money Manag. 1994, 14, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, J.M.; Grady, E.A. A contractual framework for new public management theory. Int. Public Manag. J. 1998, 1, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Doing Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, J.W.; Cresswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Method Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Hur, H. Revisiting the old debate: Citizens’ perceptions of meritocracy in public and private organizations. Public Manag. Rev. 2022, 24, 1226–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Callahan, K. Citizen involvement efforts and bureaucratic responsiveness: Participatory values, stakeholder pressures, and administrative practicality. Public Admin. Rev. 2007, 67, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiasen, D.G. The new public management and its critics. Int. Public Manag. J. 1999, 2, 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, A.; Jones, G. Reshaping the state: Administrative reform and new public management in France. Governance 2005, 18, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.K.; Jena, L.K.; Kumari, I.G. Effect of work-life balance on organisational citizenship behaviour: Role of organisational commitment. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2016, 17, 15S–29S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetio, A.P.; Yuniarsih, T.; Ahman, E. Perceived work-life interface and organisational citizenship behaviour: Are job satisfaction and organisational commitment mediates the relations? Int. J. Hum. Res. Stud. 2017, 7, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organisations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: Maidenhead, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Loi, R.; Lam, L.W. Linking organizational identification and employee performance in teams: The moderating role of team-member exchange. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2011, 22, 3187–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).