Abstract

Tannery effluents constitute highly complex chemical and biological matrices that can affect ecosystem integrity and public health. In Paraguay, metagenomic information on industrial discharge remains limited. In this context, the aim of this study was to characterize microbiome diversity and detect antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) via metagenomic sequencing complemented by chemical analyses. Total DNA was sequenced using Oxford Nanopore technologies and analyzed with Kraken2 for taxonomic assignment and CARD for ARG detection. The results revealed a hypersaline, metal-containing effluent with a high organic load and measurable nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations. Microbiome profiles were dominated by Pseudomonadota (77.2%), primarily Thiocapsa (27.8%) and Francisella (23.0%). The phototrophic and sulfur-oxidizing metabolism characteristic of Thiocapsa may explain the distinctive coloration of the effluent, while the predominance of Francisella is consistent with tolerance to hostile environmental conditions. DNA sequences assigned to taxa of clinical relevance, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, were also detected, along with a range of ARGs associated with resistance to tetracyclines, β-lactams, and aminoglycosides. These findings demonstrate that treated tannery effluent can retain clinically relevant genetic material and ARGs, underscoring the need to integrate metagenomic surveillance into environmental monitoring frameworks to better understand and mitigate emerging resistance determinants in aquatic systems. This study provides one of the first metagenomic characterizations of a tannery effluent in the country and contributes novel insights at a regional scale.

1. Introduction

Tanneries are among the most polluting industries worldwide, generating large volumes of effluents enriched in organic matter, heavy metals, recalcitrant compounds, and a high microbial load [1,2]. The chemical and microbiological composition of these discharges varies widely depending on the technologies employed in leather processing and the type of waste treatment applied. Consequently, such effluents may exhibit visible color changes ranging from dark brown to reddish-purple hues, the latter often associated with the activity of sulfur-metabolizing or pigment-producing microorganisms [3].

In addition to their complexity, inadequately treated tannery effluents pose substantial risks to aquatic ecosystems and public health. Their continuous release may promote the persistence and dissemination of microorganisms, including taxa with pathogenic or opportunistic potential, in receiving waters used for domestic, agricultural, or recreational purposes [4,5,6].

Beyond their physicochemical impacts, industrial effluents have increasingly been recognized as reservoirs and dissemination pathways of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). These genes can be disseminated into the environment, where they may contribute to the spread and persistence of resistance determinants within microbial communities. Although the presence of ARGs does not equate to antimicrobial resistance (AMR), their environmental dissemination is considered relevant to the broader AMR framework, and the World Health Organization (WHO) identifies AMR as a major public health concern [7,8,9,10]. Contaminated aquatic environments, particularly those impacted by industrial and hospital discharges, act as critical hotspots for the emergence and dissemination of ARGs [11].

In this context, metagenomic analysis of environmental DNA via high-throughput sequencing is a powerful tool for taxonomic profiling. It enables inference of microbial community composition by assigning reads and contigs to reference databases. It also supports the detection of DNA signatures assigned to taxa associated with pathogenic or opportunistic lineages. In addition, it supports the characterization of the repertoire of functional genes, including ARGs [12].

This strategy can be implemented using various high-throughput sequencing platforms, including long-read technologies such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), which provide advantages for genetic resolution and the contextual analysis of ARGs. Applying this approach to industrial effluents is essential to elucidate their contribution to the environmental resistome and their potential impact on local ecosystems [13].

In Paraguay, the growth of industrial activity has not always been accompanied by adequate environmental management. Many industries, including tanneries, discharge their effluents directly into streams and rivers without effective treatment, exacerbating water pollution [14]. Moreover, metagenomic characterization of industrial effluents in Paraguay is virtually absent. This gap limits our understanding of the environmental resistome and of the DNA based microbiome profiles (taxonomic signatures) present in these discharges. It also limits current knowledge of their potential ecological and public health impacts [15,16]. Overall, this approach provides an integrated, high-resolution framework for environmental monitoring that remains scarcely applied in the country.

This study presents one of the first metagenomic assessments of a tannery effluent in Paraguay. Its objective was to characterize microbiome diversity and detect antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) through metagenomic sequencing complemented by chemical analyses. The public availability of the dataset is intended to foster reproducibility, enable re-analysis, and support integration with comparative studies across the region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Site

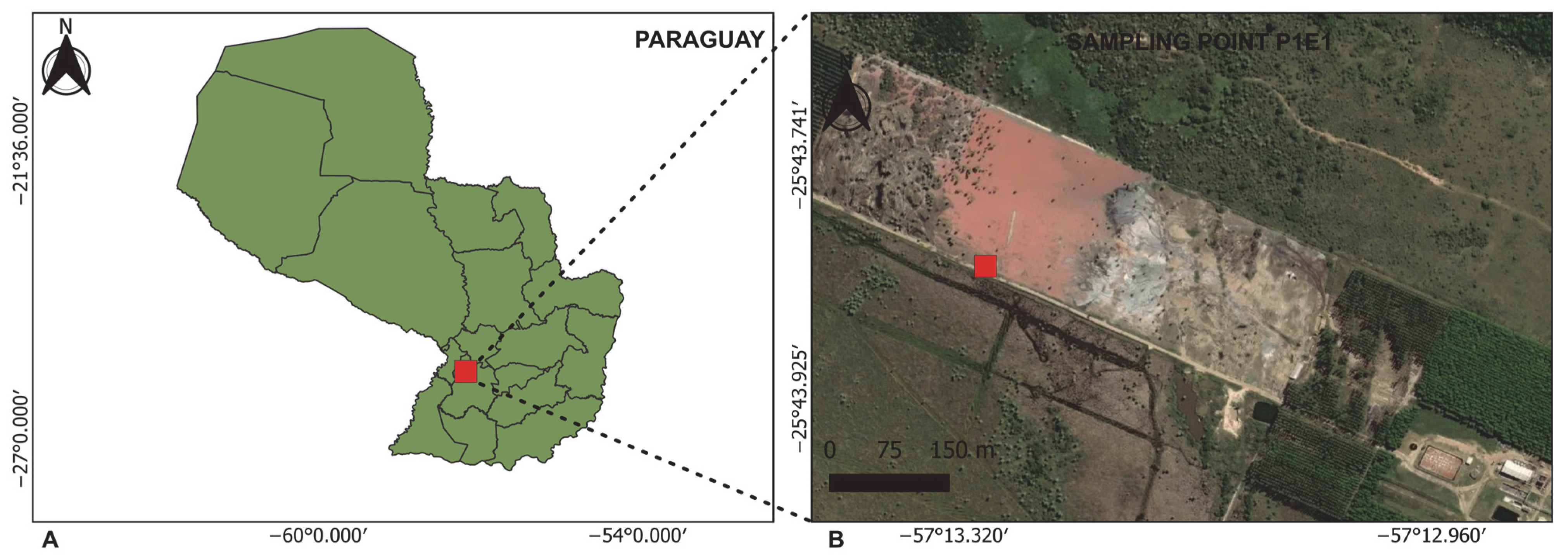

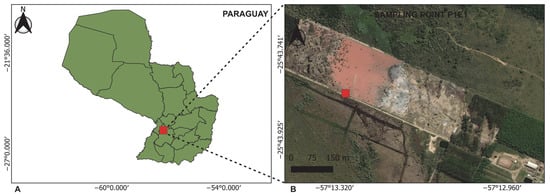

The liquid sample was collected in August 2021 by technicians from the Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development (MADES) at an accessible location (25°43′49.4″ S, 57°13′17.8″ W). The sampling point was identified as P1E1 and corresponds to the discharge area of a tannery located approximately 75 km from Asunción and situated near a stream (Figure 1). At the time of sampling, the effluent exhibited a distinctive reddish-purple (wine-red) coloration, a feature uncommon in industrial wastewater. This visual anomaly prompted MADES to collect the sample for subsequent metagenomic analysis to assess its composition and potential causes.

Figure 1.

The geographic location of the sampling site. (A) A map of Paraguay showing the region where the sampling point is located. (B) A satellite view of the study area, indicating sampling point P1E1. Source Information: Map layers were adapted from multiple sources. Panel (A) uses cartography from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), Paraguay (https://www.ine.gov.py/microdatos/cartografia-digital-2022.php (accessed on 30 September 2025)), Public Information Use License. The basemap in Panel (B) was adapted from ©MapTiler and ©OpenStreetMap contributors (https://openmaptiles.org/ (accessed on 30 September 2025)), used under the Open Database License.

2.2. Sample Collection

A total of 2 L of treated tannery effluent was collected as a pooled (composite) sample. Of this volume, 1800 mL was allocated for chemical determinations, while 200 mL was reserved for metagenomic analysis [17].

2.3. Chemical Characterization of the Effluent

Chemical water-quality data were provided by the Ministry of the Environment (MADES) from laboratory analyses of the effluent collected in August 2021 (Table 1). Sodium, potassium, chromium, iron, manganese, nickel, lead, cadmium, arsenic, chlorides, chemical oxygen demand (COD), total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and sulfates were determined according to the Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater [18]. Metal concentrations were determined using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) in accordance with the referenced analytical standards.

Table 1.

Chemical parameters and heavy metals detected in the tannery effluent. Sampling point: P1E1.

2.4. DNA Extraction and Purification

A total of 200 mL of aliquot was transported under cold-chain conditions (4 °C) to the CEMIT laboratory at the National University of Asunción (UNA) [19,20,21]. Upon arrival at the laboratory, the sample was filtered through 0.22 µm pore-size nitrocellulose membranes [22]. The membranes were then cut into small fragments and transferred to sterile tubes containing microbeads to facilitate mechanical disruption of microbial cells prior to DNA extraction [23].

Genomic DNA was extracted following a modified protocol based on the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The extracted DNA was subsequently purified using the ProNex® Size-Selective Purification System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to obtain high-quality DNA suitable for next-generation sequencing (NGS) library construction [24].

2.5. Library Preparation

The sequencing library was prepared using the SQK-RAD004 Rapid Sequencing Kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, UK). All kit components were thawed at room temperature, briefly centrifuged, and mixed via gentle pipetting; reagents were kept on ice until use [25]. For fragmentation, a 10 μL reaction was assembled in a thin-walled PCR tube by combining the DNA with 7.5 μL of Fragmentation Mix (FRA), gently mixing, and briefly centrifuging. Enzymatic fragmentation was performed at 30 °C for 1 min, followed by heat inactivation at 80 °C for 1 min and immediate cooling on ice. For adapter ligation, 1 μL of Rapid Adapter (RAP) was added to 10 μL of fragmented DNA, gently mixed, briefly centrifuged, and incubated at room temperature for 5 min, according to the manufacturer’s instructions for SQK-RAD004 [25].

2.6. Sequencing and Data Analysis

Sequencing was performed on a MinION device (ONT) controlled by MinKNOW using a FLO-MIN106D (R9.4.1) flow cell [26]. The FAST5 files obtained from the sequencer were converted to POD5 format using the pod5 program (v0.3.23). Subsequently, basecalling was performed using Dorado (v0.9.6) with GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) support, using the super-accuracy model (dna_r9.4.1_e8_sup). The resulting reads were filtered with Filtlong (v0.2.1), retaining only those that met the following parameters: a minimum length of ≥50 bp (--min_length 50) and an average quality (Q) of ≥10 (--min_mean_q 90), according to the criteria described by Haan and Drown (2021) [27,28].

Taxonomic assignment of the reads was performed using Kraken2 (v2.1.3), followed by Bracken (v3.0.1) to estimate relative abundances [29,30]. Both tools utilized the Standard Plus RefSeq Protozoa, Fungi & Plant (PlusPFP) database, which has an index size of approximately 171 GB (version 2024) and includes genomes of bacteria, archaea, viruses, protozoa, fungi, plants, and human reference sequences [31,32]. Metagenomic assembly was conducted with Flye (v2.9.3) using the --meta parameter to reconstruct longer assembled sequences from complex metagenomic datasets. Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) were then identified by applying ABRicate (v1.0.1) to the Flye-generated contigs using the CARD nucleotide database (version 2025-Sep-2). Functional annotation of taxonomic profiles was performed with FAPROTAX (v1.2.9) [33,34].

The geographical representation of the sampling sites was created in QGIS (v3.40). Abundance plots were generated in R (v4.5.1) and Pavian (v1.2.1), while the remaining figures were produced using the packages ggplot2 (v3.5.2), dplyr (v1.1.4), RColorBrewer (v1.1.3), grid (v4.5.1), gridExtra (v2.3), and scales (v1.4.0). For chord diagram visualization, the circlize package (v0.4.16) was employed [35,36,37].

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition of the Tannery Effluent

The chemical analysis of the liquid effluent (Table 1) showed a highly saline matrix with elevated concentrations of sodium (5081 mg L−1) and chlorides (4232 mg L−1). In addition, the presence of sulfate (23.3 mg L−1), iron (2.31 mg L−1), manganese (0.33 mg L−1), chromium (0.27 mg L−1), arsenic (0.16 mg L−1), nickel (0.023 mg L−1), lead (0.005 mg L−1), and cadmium (0.003 mg L−1) was also detected. The organic matter content, represented by the chemical oxygen demand (COD), reached 1454 mg O2 L−1. Finally, total nitrogen (2.80 mg N L−1) and total phosphorus (1.51 mg P L−1) were quantified.

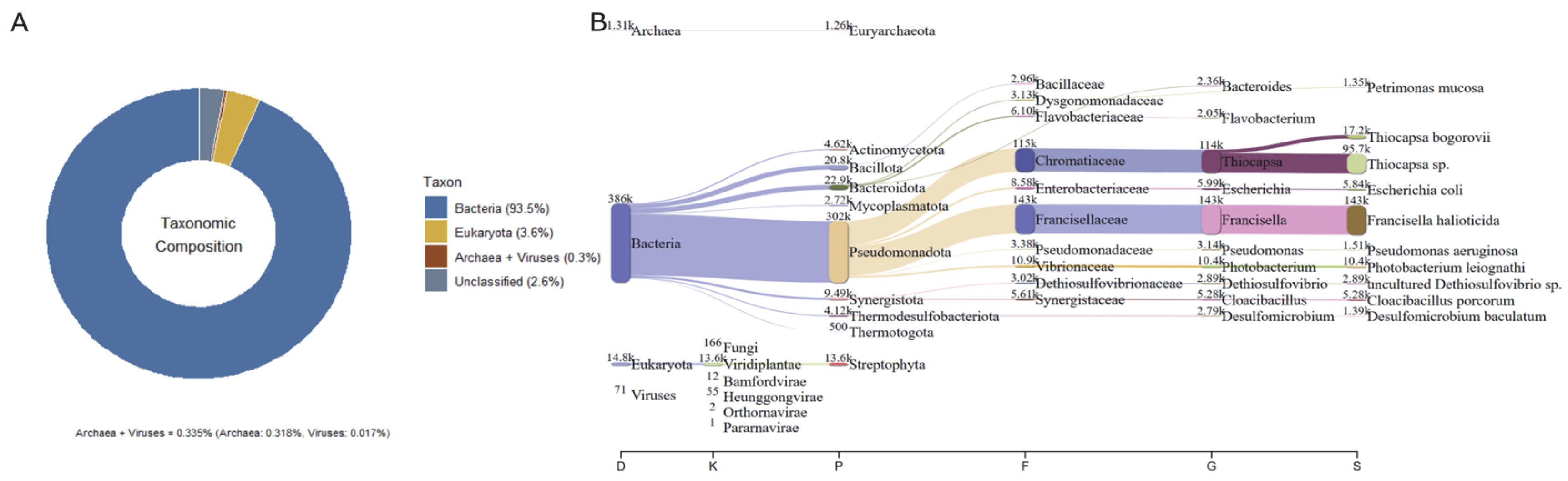

These conditions are consistent with sulfidic and hypersaline conditions that can support sulfur-oxidizing and phototrophic bacteria such as Thiocapsa (Chromatiaceae) (Table 1 and Figure 2). Their pigments may help explain the reddish-purple coloration observed during sampling [38,39].

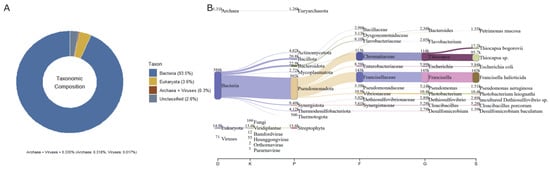

Figure 2.

The relative abundances of taxonomic assignments based on metagenomic reads. (A) The relative abundance of reads classified as bacteria (93.5%), Eukaryota (3.6%), archaea + viruses (0.335%), and unclassified sequences (2.6%). (B) Sankey diagram D (domain) → K (kingdom) → P (phylum) → F (family) → G (genus) → S (species); the band width is proportional to read counts. In panel (A), colors denote the major taxonomic categories, whereas in panel (B) colors highlight the most abundant taxa traced down to the species level.

3.2. Taxonomic Composition and Structure of the Microbiome

Based on the metagenomic profile (Figure 2A,B), the community was dominated by bacteria (93.5% of classified reads), with minor contributions from Eukaryota (3.6%) and a residual fraction of rchaea + viruses (0.335%); 2.6% remained unclassified. The Sankey diagram revealed that within bacteria, Pseudomonadota (Proteobacteria sensu lato) predominated, followed by Actinomycetota, Bacillota, and Bacteroidota, with families of sanitary or environmental relevance such as Enterobacteriaceae (Escherichia—E. coli), Pseudomonadaceae (Pseudomonas—P. aeruginosa), Vibrionaceae (Photobacterium), Francisellaceae (Francisella), and groups associated with the sulfur cycle (Chromatiaceae—Thiocapsa, Dethiosulfovibrionaceae, and Desulfomicrobium), as well as Synergistaceae (Cloacibacillus). Within Eukaryota, Viridiplantae/Streptophyta predominated; among archaea, Euryarchaeota predominated; and viruses appeared marginally (e.g., Bamfordvirae and Heunggongvirae).

Overall, the pattern reflected a strongly bacterium-dominated, DNA-based taxonomic profile, including DNA signatures assigned to taxa of recognized environmental and public health relevance (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli). The dataset also revealed anaerobic metabolisms associated with sulfur cycling, consistent with matrices characterized by redox gradients and high organic load.

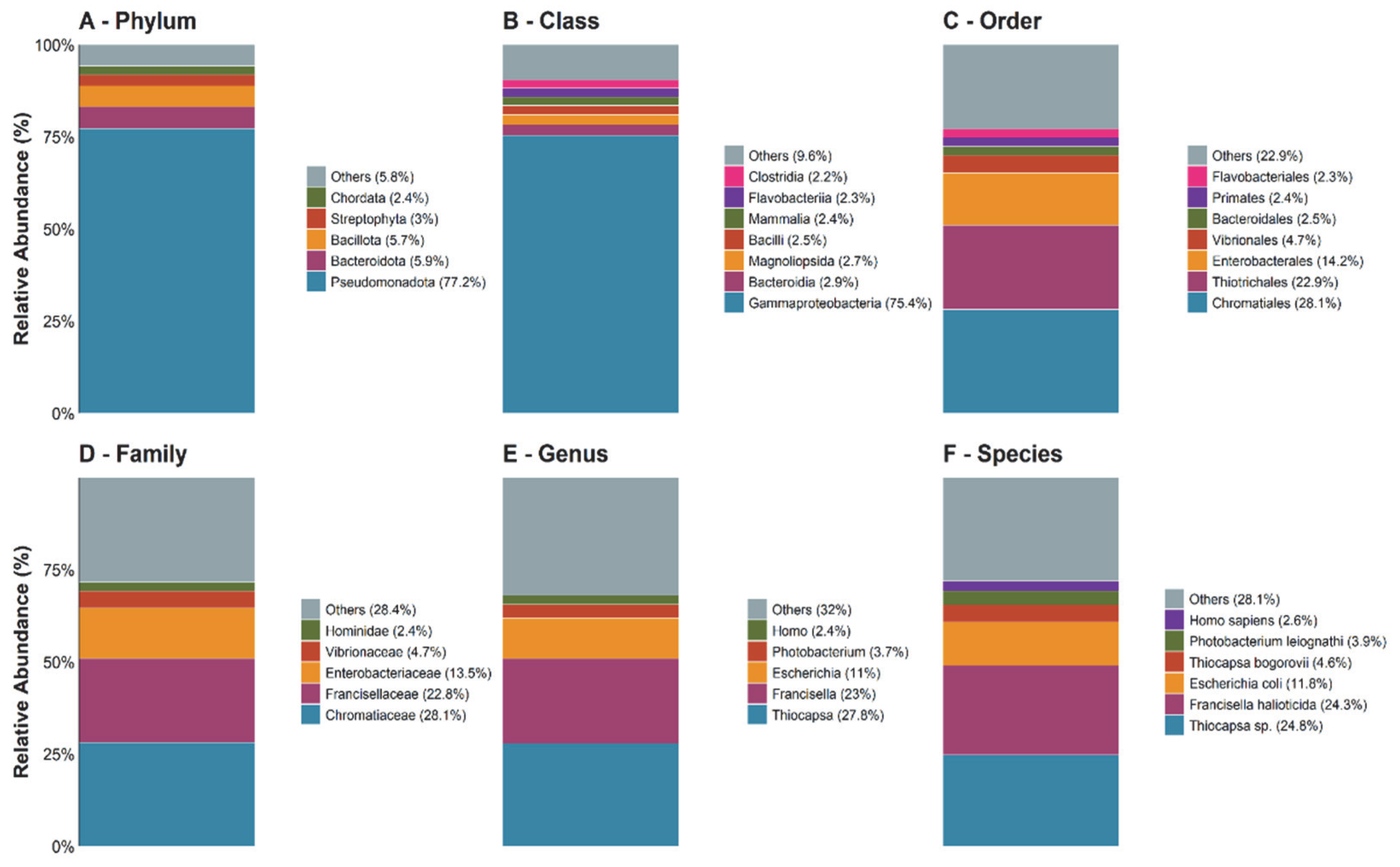

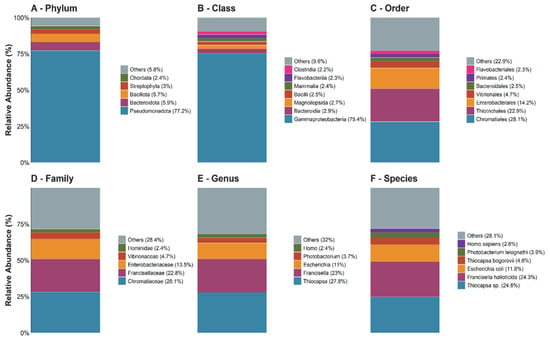

At the phylum level (Figure 3A), the profile was dominated by Pseudomonadota (77.2%), followed by Bacteroidota (5.9%) and Bacillota (5.7%). The eukaryotic fraction was minor, represented mainly by Streptophyta (3%) and Chordata (2.4%), while the “Others” group contributed 5.8%.

Figure 3.

The relative taxonomic composition inferred from metagenomic reads across hierarchical ranks (A–F). The bar plots show the proportional distribution of taxa at the phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species levels, based on Kraken2 assignments.

Within Pseudomonadota (Figure 3B), Gammaproteobacteria accounted for 75.4% of DNA-based assignments. At the order level (Figure 3C), Chromatiales (28.1%) and Thiotrichales (22.9%) predominated. This pattern was driven by Chromatiaceae (Chromatiales; 28.1%) and Francisellaceae (Thiotrichales; 22.9%), respectively, with Thiocapsa and Francisella as the dominant genera (Figure 3C–E). At the species level (Figure 3E), the most abundant DNA signatures corresponded to Thiocapsa sp. (24.8%) and Francisella halioticida (24.3%). Overall, the profile was dominated by Proteobacteria sensu lato.

3.3. DNA Signatures Associated with Taxa of Public Health Relevance

Metagenomic sequencing generated 445,400 reads, of which DNA sequences were assigned to several bacterial taxa of public health relevance in the final effluent (Table 2). Overall, 15 taxa with genetic signatures corresponding to bacteria, including clinically important strains, were identified, spanning genera such as Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Acinetobacter, Enterococcus, Escherichia, Salmonella, Shigella, Bacteroides, and Clostridioides. The highest read counts corresponded to Escherichia coli (5488 reads; 1.23% of the dataset), followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1118 reads) and Salmonella enterica (616 reads), together with Klebsiella pneumoniae, Shigella flexneri, and Clostridioides difficile. These DNA sequences represent genetic fragments assigned to taxa known to include strains implicated in human disease, indicating that genetic material of public health interest persists in the effluent. The detection of these sequences highlights the potential ecological relevance of the discharged genetic material in aquatic and terrestrial environments.

Table 2.

Clinically associated DNA signatures identified in the final effluent of the tannery wastewater treatment plant. The table presents each taxon, its commonly reported clinical associations, genus- and species-level assignments, and the corresponding number of metagenomic reads assigned to each *.

3.4. Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs)

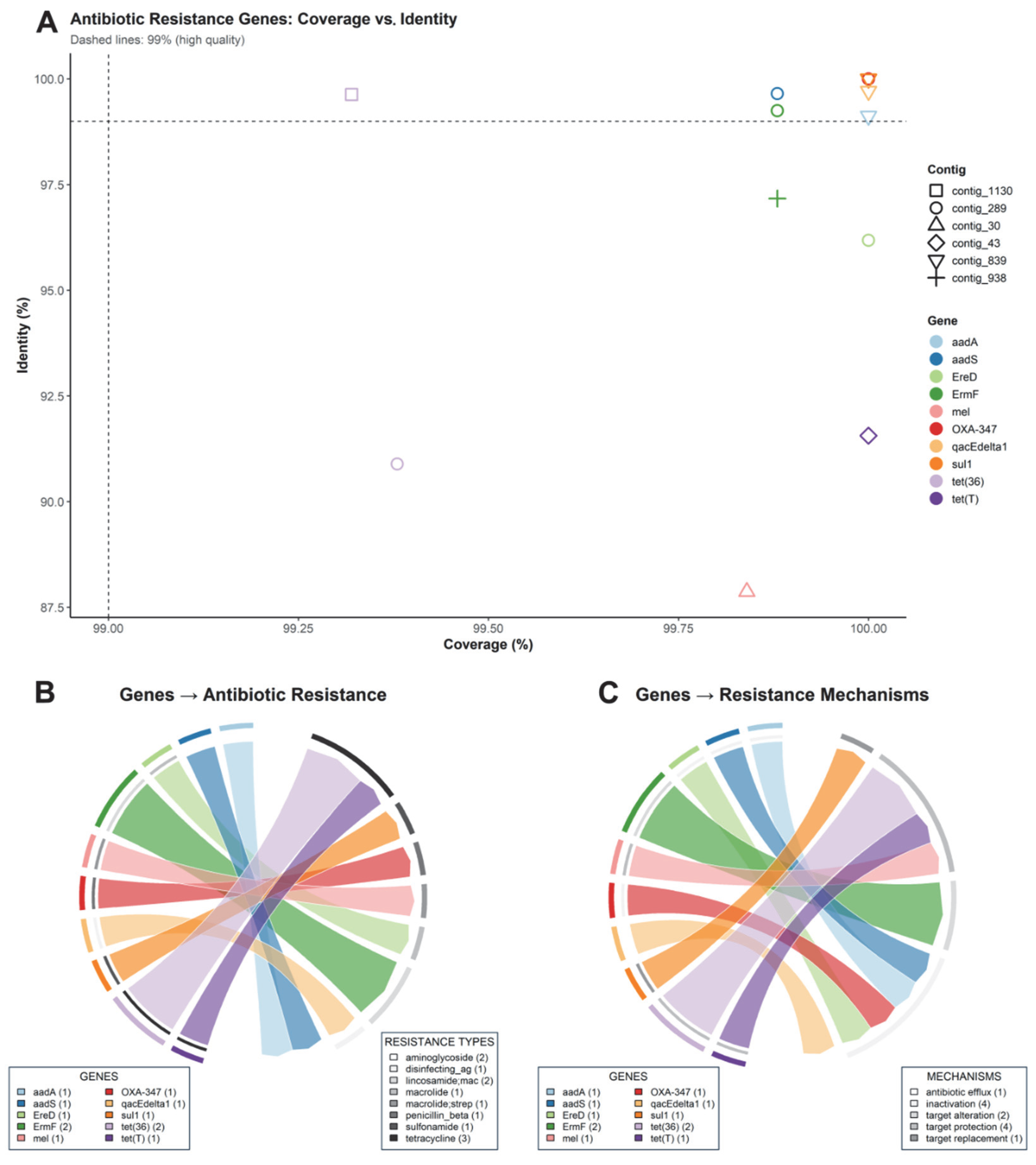

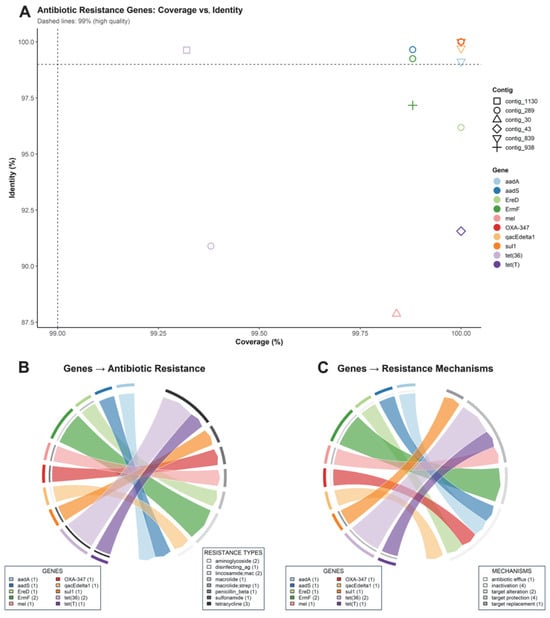

Multiple antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) were identified in the metagenomic assemblies obtained. The analysis of coverage and nucleotide identity (Figure 4A) showed that most ARGs met the high-quality threshold (≥99% coverage and ≥99% identity), indicating reliable assignment. Among the detected genes were aadA, aadS, ermF, ereD, mel, qacEΔ1, sul1, tet(36), tet(T), and OXA-347, distributed across different contigs, with no evidence of fragmentation compromising annotation integrity.

Figure 4.

Resistome identified by metagenomics. (A) Scatter plot of identity (%ID) vs. coverage (%COV) per gene and contig. (B) Chord diagram linking genes with antibiotic classes. (C) Chord diagram linking genes with resistance mechanisms.

Functional analysis revealed a diversity of resistance classes (Figure 4B). The ARGs were mainly associated with resistance to tetracyclines (tet(36), tet(T)), followed by genes linked to aminoglycosides (aadA and aadS) and lincosamides/macrolides (ermF, ereD, and mel). Specific determinants were also detected for isolated macrolide resistance, macrolide–streptogramin combinations, β-lactam resistance of the penicillin type (OXA-347), sulfonamides (sul1), and a marker associated with resistance to quaternary ammonium biocides and disinfectants (qacEΔ1). This distribution indicates a multiresistant potential, consistent with the coexistence of different genetic defense mechanisms against antimicrobials.

Mechanistically (Figure 4C), the identified ARGs were mainly associated with enzymatic inactivation (e.g., aadA, aadS for aminoglycosides; OXA-347 for β-lactams), as well as active efflux (ereD, mel, tet(36), and tet(T)) that reduces the intracellular antibiotic concentration. Determinants linked to ribosomal protection and target site modification were also identified (e.g., ermF for macrolides and lincosamides), as well as a case of functional target replacement (sul1). The combined presence of these mechanisms suggests a high adaptive plasticity of microbial communities under antimicrobial selective pressure.

4. Discussion

The present study constitutes one of the first metagenomic characterizations of a tanning-industry effluent in Paraguay and provides unprecedented information for the region, where data on industrial microbiomes remain scarce and fragmentary [45,52,53]. The profile obtained revealed a complex DNA-based taxonomic profile strongly dominated by Pseudomonadota (77.2%), with a marked abundance of Francisella (23.0%) and Thiocapsa (27.8%), as well as genera commonly associated with clinical relevance, such as Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Acinetobacter, Enterococcus, Escherichia, Salmonella, Shigella, Bacteroides, and Clostridioides [54]. This pattern may reflect DNA signatures from taxa associated with organic-rich, high-load industrial effluents exhibiting pronounced redox heterogeneity and sulfur-influenced conditions [55].

The chemical profile described in Table 1 supports this interpretation, as the effluent exhibited extreme salinity (Na+ = 5081 mg L−1; Cl− = 4232 mg L−1) and detectable levels of iron, chromium, and arsenic, suggesting an anoxic or microaerophilic, sulfide-rich, and hypersaline environment. The high chemical oxygen demand (1454 mg O2 L−1) together with measurable total nitrogen (2.80 mg N L−1) and total phosphorus (1.51 mg P L−1) indicate a substantial organic and nutrient load capable of supporting dense and metabolically diverse microbial populations. Such conditions are consistent with the proliferation of purple sulfur bacteria such as Thiocapsa (family Chromatiaceae), whose bacteriochlorophylls and carotenoids may explain the reddish-purple coloration observed during sampling [39]. The co-occurrence of Francisella and Thiocapsa likely reflects a joint microbial response to extreme redox and saline gradients, rather than a direct biological association, consistent with redox-related functional potential across these taxa [56,57].

Nevertheless, the DNA-based taxonomic dominance of Francisella and Thiocapsa contrasts with reports from India, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia, where sequencing-based profiles of tannery effluents are typically dominated by Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, and Enterobacteriaceae, and with studies from Brazil and Argentina reporting predominance of metal-tolerant Gammaproteobacteria [58,59,60,61]. This difference suggests that site-specific processing conditions, together with the limited treatment efficiency suggested by the chemical profile at the time of sampling, may favor environmental taxa such as Francisella halioticida and Thiocapsa. These niche conditions are poorly documented in the region and may explain the distinctive taxonomic profile observed in this effluent [62]. This finding underscores the importance of generating local data, as extrapolating metagenomic profiles from other regions could underestimate the true complexity of our systems [63].

A relevant finding for environmental surveillance and risk assessment was the detection of DNA signatures assigned to bacterial taxa of clinical relevance, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Salmonella enterica, Shigella flexneri, and Gram-positive taxa such as Streptococcus agalactiae, Enterococcus faecium, and Clostridioides difficile. These species appear on WHO priority lists because their viable forms are associated with severe infections and nosocomial outbreaks [9].

However, in this study, only DNA fragments assigned to these taxa were detected, and treatment processes may have already inactivated the viable cells. This indicates that the local treatment system fails to eliminate or degrade potentially transferable genetic material, rather than demonstrating active infection risk [64].

Recent DNA-based studies in the region have reported the presence of E. coli and Klebsiella in industrial and urban effluents, with relative abundances and taxonomic profiles comparable to those observed here [45,65,66]. However, for Paraguay, comparable genomic surveillance data remain limited, and environmental regulation is still largely based on conventional indicators such as fecal coliforms and BOD/COD. Therefore, the detection of enteric and clinically associated DNA signatures in the studied industrial discharge highlights a regulatory and monitoring gap that could be addressed by integrating DNA-based approaches [67]. Rivers and streams affected by industrial activity are frequently used for irrigation, local fishing, and recreational activities. The continuous release of effluent containing this genetic material may contribute to the environmental dissemination of microorganisms of public health relevance. This, in turn, could increase potential exposure risks for human and animal populations [68,69,70,71].

The identified resistome deepens this concern because we detected determinants for multiple antibiotic classes—tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, lincosamides, macrolides, β-lactams, sulfonamides—with high coverage and identity [69,72]. This distribution reflects the coexistence of multiple selective pressures: frequently used clinical antibiotics (human/animal use) and industrial compounds and disinfectants, a pattern consistent with tanning effluent studies from Brazil and India but, until now, undocumented for Paraguay [73,74].

The coexistence of multiple resistance mechanisms indicates the high adaptive plasticity of the microbial community under cumulative antimicrobial pressures, suggesting that this effluent could serve as a relevant reservoir of resistance determinants with potential implications for horizontal gene transfer [8,69]. The simultaneous presence of genes associated with resistance to clinically critical antibiotics (such as OXA-347) and to industrial disinfectants (qacEΔ1) is especially concerning. This pattern suggests cross-selective pressure, in which the use of biocides and quaternary ammonium compounds could favor the retention and dissemination of antibiotic resistance. This phenomenon has been documented in effluents from the food and healthcare industries, but its demonstration in a Paraguayan tannery provides novel regional evidence and points to an additional risk to receiving ecosystems, which could become hotspots for evolution and the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance [75].

The relevance of these findings for South America extends beyond surface water quality. Paraguay hosts two of the most important aquifers in the region: the Patiño, which supplies much of the Asunción metropolitan area, and the Guaraní, one of the largest freshwater reservoirs in the world [76,77,78]. The recharge zones of these aquifers are vulnerable to infiltration of chemical and biological contaminants from impacted surface waters and soils affected by industrial discharges. The detection of DNA signatures associated with taxa of public health relevance—together with antibiotic resistance genes—in effluents lacking advanced treatment is noteworthy. These findings raise concerns about the potential movement of such genetic determinants into subsurface environments. This risk is particularly relevant in areas where hydrogeological monitoring and the protection of recharge zones are limited [79,80]. Recent studies in Brazil have shown the presence of ARGs in groundwater associated with industrial and urban activity. However, for Paraguay, there are no published data on the possible infiltration of antibiotic resistance genes into key aquifers, which underscores the urgency of monitoring the microbiological and genetic quality of groundwater [81].

Integrating the observed microbiome diversity with the detection of DNA signatures from taxa of public health relevance and a multiclass resistome provides a broader perspective on the potential risks associated with discharging industrial effluents without advanced controls in a country that critically depends on its aquifers for human consumption and agricultural production [82,83]. Although metagenomic data do not allow inference of microbial viability, the environmental circulation of genetic material—including antibiotic resistance genes—raises concerns regarding its potential movement through surface and subsurface systems, particularly in regions where hydrogeological protection is limited [11,84]. In addition, the metabolic potential associated with sulfur-based and reducing functional groups may influence local biogeochemical processes. This, in turn, may favor redox regimes consistent with anoxic to microaerophilic conditions, which can facilitate the mobility of metals and other contaminants into deeper zones.

In this context, the One Health framework remains relevant, even though metagenomic data do not provide evidence of microbial viability or gene expression. Nevertheless, the findings highlight the potential risks arising from the interface between environmental contamination and human or animal exposure. From a One Health perspective, these results underscore the importance of monitoring aquatic systems that are vulnerable to this type of impact [85,86,87].

The findings should be viewed as a pilot-scale metagenomic assessment, as industrial effluents can vary across facilities and over time. Nevertheless, despite this scope, the dataset provides a critical first insight into the DNA-based taxonomic and genetic profile of the final effluent from the studied tannery in Paraguay. Future studies, including multi-site replication and additional sampling time points, are needed to quantify inter-facility and temporal variability.

Despite these limitations, the results highlight the urgent need to modernize environmental regulation in Paraguay and neighboring countries. Current monitoring practices focus mainly on coliforms and basic physicochemical parameters. These approaches do not capture DNA-based genomic indicators that can signal potential microbiological risks or antibiotic resistance. Improved treatment strategies and the protection of aquifer recharge zones are also necessary to reduce the impact of the leather-tanning industry and other highly polluting activities.

Regionally, the data generated here provide an initial foundation for developing water-management policies that integrate public health, industrial sustainability, and aquifer protection. These policies are increasingly relevant given global concerns about antimicrobial resistance and water security.

5. Conclusions

This study provides one of the first metagenomic characterizations of DNA-based taxonomic and antibiotic resistance profiles from a tannery final effluent sample collected in Paraguay. The results reveal a highly saline environment enriched in metals and DNA signatures associated with taxa such as Francisella and Thiocapsa, the latter of which likely contributes to the distinctive reddish-purple coloration observed in the effluent. The detection of genetic markers associated with bacteria of public health relevance, together with a diverse array of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) linked to tetracyclines, β-lactams, aminoglycosides, macrolides, and sulfonamides, indicates the presence of resistance determinants in non-hospital industrial discharges.

These findings underscore the need to integrate environmental metagenomics into national water-quality-monitoring frameworks and expand regulatory standards beyond conventional microbiological indicators. Incorporating genomic tools alongside advanced treatment and source-control measures will be essential to mitigate the dissemination of resistance determinants, protect aquatic ecosystems, and safeguard critical groundwater reserves such as the Patiño and Guaraní aquifers.

Overall, these findings strengthen the need for integrated monitoring approaches within a One Health framework, connecting industrial pollution control with public and environmental health protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B.R. and A.A.A.; methodology, M.M.S. and S.A.Q.; software, S.A.Q.; formal analysis, S.A.Q.; investigation; G.B.R. and A.A.A.; resources, A.A.A.; data curation, S.A.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.A. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, S.A.Q. and A.R.; supervision, G.B.R.; project administration, G.B.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded through self-financing by the Multidisciplinary Center for Technological Research (CEMIT) of the Rectorate of the National University of Asunción (UNA). No external grant number applies.

Data Availability Statement

The metagenomic sequences generated and analyzed in this study have been deposited in the NCBI BioProject database under the accession number PRJNA1354099.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaboration of the Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development (MADES) under the specific cooperation agreement MADES–CEMIT 2020–2022. All scientific content and interpretations remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CEMIT | Multidisciplinary Center for Technological Research |

| UNA | National University of Asuncion |

| MADES | Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development |

| ONT | Oxford Nanopore Technologies |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ARGs | Antibiotic resistance genes |

| AMR GPU | Antimicrobial resistance Graphics Processing Unit |

References

- Singh, K.; Kumari, M.; Prasad, K.S. Tannery Effluents: Current Practices, Environmental Consequences, Human Health Risks, and Treatment Options. CLEAN—Soil Air Water 2023, 51, 2200303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiarajan, J.; Krishnan, M.; Suganya, T. Recent Trends on Mining of Microbial Tannase from Waste Water Recycling Units of Tannery. In Microbial Niche Nexus Sustaining Environmental Biological Wastewater and Water-Energy-Environment Nexus; Kandasamy, S., Shah, M.P., Subbiah, K., Manickam, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 489–510. ISBN 978-3-031-62660-9. [Google Scholar]

- Overmann, J. Ecology of Phototrophic Sulfur Bacteria. In Sulfur Metabolism in Phototrophic Organisms; Hell, R., Dahl, C., Knaff, D., Leustek, T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 375–396. ISBN 978-1-4020-6863-8. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, U.; Choudhary, A.K.; Sharma, S. A 3-Year Field Study Reveals That Agri-Management Practices Drive the Dynamics of Dominant Bacterial Taxa in the Rhizosphere of Cajanus Cajan. Symbiosis 2022, 86, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uttam, S.; Singh, D.; Kumar, R.; Verma, S. Assessing the Environmental Impact Due to the Influence of Tannery Effluent on Water Quality. Chem. Afr. 2025, 8, 5635–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, M.C.; Maugeri, A.; Favara, G.; La Mastra, C.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Barchitta, M.; Agodi, A. The Impact of Wastewater on Antimicrobial Resistance: A Scoping Review of Transmission Pathways and Contributing Factors. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meradji, S.; Basher, N.S.; Sassi, A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Idres, T.; Touati, A. The Role of Water as a Reservoir for Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.-X.; Huang, K.; Miao, Y.; Shi, P.; Liu, B.; Long, C.; Li, A. Metagenomic Profiling of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and Mobile Genetic Elements in a Tannery Wastewater Treatment Plant. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Organization Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240093461 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, A.; Basher, N.S.; Kirat, H.; Meradji, S.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Idres, T.; Touati, A. The Role of the Environment (Water, Air, Soil) in the Emergence and Dissemination of Antimicrobial Resistance: A One Health Perspective. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.; Rout, S.S.; Dey, S.; Parida, C.K.; Jena, R.; Dhar, S.; Tiwari, B.; Singh, R.K.; Singh, A.K. Metagenomics and Its Application in Environmental Monitoring. In Advances in Omics Technologies; Rout, A.K., Singh, R.K., Shukla, A.K., Behera, B.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 1–37. ISBN 978-981-9502-84-4. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, B.C.; Brown, C.; Gupta, S.; Calarco, J.; Liguori, K.; Milligan, E.; Harwood, V.J.; Pruden, A.; Keenum, I. Recommendations for the Use of Metagenomics for Routine Monitoring of Antibiotic Resistance in Wastewater and Impacted Aquatic Environments. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 1731–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HCS. Preocupa la Contaminación de Ríos y Arroyos a Nivel Nacional. Available online: https://www.senado.gov.py/index.php/noticias/noticias-generales/14198-preocupa-la-contaminacion-de-rios-y-arroyos-a-nivel-nacional-2024-09-26-15-31-47 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Cañete, C. La importancia del control y monitoreo de la calidad del agua del Río Paraguay para el desarrollo y la defensa nacional. Rep. Científicos FACEN 2019, 10, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenkölbl, A.R.; Laino-Guanes, R.; Vogt-Penzkofer, C.; Benítez-Cañiza, A. Contaminación de acuíferos y eficiencia de plantas de tratamiento de aguas residuales en centros urbanos de Itapúa, Paraguay. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua 2025, 16, 327–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Brown, C.; Bürgmann, H.; Larsson, D.G.J.; Nambi, I.; Zhang, T.; Flach, C.-F.; Pruden, A.; Vikesland, P.J. Long-Read Metagenomic Sequencing Reveals Shifts in Associations of Antibiotic Resistance Genes with Mobile Genetic Elements from Sewage to Activated Sludge. Microbiome 2022, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-87553-287-5. [Google Scholar]

- Strike, W.; Faleye, T.O.C.; Lubega, B.; Rockward, A.; Torabi, S.; Noble, A.; Banadaki, M.D.; Keck, J.; Mugerwa, H.; Scotch, M.; et al. Implementing Wastewater-Based Epidemiology for Long-Read Metagenomic Sequencing of Antimicrobial Resistance in Kampala, Uganda. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.; Stebbins, B.; Ajmani, A.; Comendul, A.; Hamner, S.; Hasan, N.A.; Colwell, R.; Ford, T. Nanopore-Based Metagenomics Analysis Reveals Prevalence of Mobile Antibiotic and Heavy Metal Resistome in Wastewater. Ecotoxicology 2021, 30, 1572–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolbiecki, D.; Paukszto, Ł.; Krawczyk, K.; Korzeniewska, E.; Sawicki, J.; Harnisz, M. Chlorine Disinfection Modifies the Microbiome, Resistome and Mobilome of Hospital Wastewater—A Nanopore Long-Read Metagenomic Approach. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazi, D.; Abreu-Silva, J.; Ferreira, C.; Boudjehem, F.; Manaia, C.M.; Ouelhadj, A. Evaluation of Antibiotic Resistance in a Full-Scale Algerian Wastewater Treatment Plant: Environmental Protection Implications. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 4385–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delafont, V.; Perrin, Y.; Bouchon, D.; Moulin, L.; Héchard, Y. Targeted Metagenomics of Microbial Diversity in Free-Living Amoebae and Water Samples. In Legionella; Buchrieser, C., Hilbi, H., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 1921, pp. 421–428. ISBN 978-1-4939-9047-4. [Google Scholar]

- Promega Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit. Available online: https://worldwide.promega.com/products/nucleic-acid-extraction/genomic-dna/wizard-genomic-dna-purification-kit/ (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- ONT. Nanoporetech.Com/Es/Document/Rapid-Sequencing-Sqk-Rad004. Available online: https://nanoporetech.com/es/document/rapid-sequencing-sqk-rad004 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- ONT. Welcome to Oxford Nanopore Technologies. Available online: https://nanoporetech.com/es (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Holt, K.E. Performance of Neural Network Basecalling Tools for Oxford Nanopore Sequencing. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haan, T.J.; Drown, D.M. Unearthing Antibiotic Resistance Associated with Disturbance-Induced Permafrost Thaw in Interior Alaska. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, N.A.; Lindsey, L.L.; Kipp, E.J.; Reinschmidt, A.; Heins, B.J.; Runck, A.M.; Larsen, P.A. Nanopore-Based Surveillance of Zoonotic Bacterial Pathogens in Farm-Dwelling Peridomestic Rodents. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Thielen, P.; Salzberg, S.L. Bracken: Estimating Species Abundance in Metagenomics Data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2017, 3, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, N.A.; Wright, M.W.; Brister, J.R.; Ciufo, S.; Haddad, D.; McVeigh, R.; Rajput, B.; Robbertse, B.; Smith-White, B.; Ako-Adjei, D.; et al. Reference Sequence (RefSeq) Database at NCBI: Current Status, Taxonomic Expansion, and Functional Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D733–D745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved Metagenomic Analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Huynh, W.; Chalil, R.; Smith, K.W.; Raphenya, A.R.; Wlodarski, M.A.; Edalatmand, A.; Petkau, A.; Syed, S.A.; Tsang, K.K. CARD 2023: Expanded Curation, Support for Machine Learning, and Resistome Prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D690–D699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and Applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhadher, S.A.A.; Sidek, L.M.; Khan, M.S.J.; Al-Habshi, M.M.A.; Kurniawan, T.A. Seasonal Variations in Water Quality and Hydrological Dynamics in a Tropical Reservoir Driven by Rainfall, Runoff, and Anthropogenic Activities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitwieser, F.P.; Salzberg, S.L. Pavian: Interactive Analysis of Metagenomics Data for Microbiome Studies and Pathogen Identification. Bioinformatics 2019, 36, 1303–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Fu, Y.; Qiu, R.; Ning, H.; Liu, H.; Li, C.; Gao, Y. Carbon Amendments Shape the Bacterial Community Structure in Salinized Farmland Soil. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01012-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dungan, R.S.; Leytem, A.B. Detection of Purple Sulfur Bacteria in Purple and Non-Purple Dairy Wastewaters. J. Environ. Qual. 2015, 44, 1550–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushkevych, I.; Procházka, J.; Gajdács, M.; Rittmann, S.K.-M.R.; Vítězová, M. Molecular Physiology of Anaerobic Phototrophic Purple and Green Sulfur Bacteria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manika, M.M.; Tano, A.K.; Kapend’a, L.K.; Mujing’a, F.M.; Kakisingi, C.N.; Matanda, S.K.; wa Mwanza Teta, I.; Mukalay, Y.B.; Kasamba, E.I.; Barhayiga, B.N.; et al. Bacteriological Profile and Antimicrobial Resistance in Sepsis Cases in Intensive Care Units in Lubumbashi: Challenges and Perspectives. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2025, 24, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, M.A.I.; William-Dee, J.; Morni, M.A.; Azhar, N.A.A.; Sabarudin, N.A.-S.; Jinggong, E.R.; Zolkapley, S.; Baharom, N.I.M.; Haqeem, M.D.; Sien, V.L.; et al. Metagenomic Insights into Host-Specific Gastroenteritis Bacteria in Forest Rodents of Sarawak, Borneo: Implications for One Health Surveillance of Rodent-Borne Pathogens. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Bharadwaj, H.R.; Al Ta’ani, O.; Khan, S.; Alsakarneh, S.; Malik, S.; Hayat, U.; Gangwani, M.K.; Ali, H.; Dahiya, D.S. Updates and Current Knowledge on the Common Forms of Gastroenteritis: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlasco, J.; Beqiraj, I.; Bolla, C.; Marino, E.M.I.; Zanelli, C.; Gualco, C.; Rocchetti, A.; Gianino, M.M. Impact of Septic Episodes Caused by Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a Tertiary Hospital: Clinical and Economic Considerations in Years 2018–2020. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.K.; Pham, T.T.N.; Nguyen, H.D.; Dam, Q.T.; Phung, T.B.T.; Nguyen, T.V.H.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Hoang, K.C.; Do, T.H. Metagenomic Analysis of the Gastrointestinal Phageome and Incorporated Dysbiosis in Children with Persistent Diarrhea of Unknown Etiology in Vietnam. Pathogens 2025, 14, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Guido, B.; Barrantes, K.; Rodríguez, C.; Rojas-Jimenez, K.; Arias-Andres, M. The Impact of Urban Pollution on Plasmid-Mediated Resistance Acquisition in Enterobacteria from a Tropical River. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, I. Microbiology and Management of Intra-Abdominal Infections in Children. Pediatr. Int. 2003, 45, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takesue, Y.; Kusachi, S.; Mikamo, H.; Sato, J.; Watanabe, A.; Kiyota, H.; Iwata, S.; Kaku, M.; Hanaki, H.; Sumiyama, Y.; et al. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Common Pathogens Isolated from Postoperative Intra-Abdominal Infections in Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 2018, 24, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Chu, S.-M.; Wang, H.-C.; Yang, P.-H.; Huang, H.-R.; Chiang, M.-C.; Fu, R.-H.; Tsai, M.-H.; Hsu, J.-F. Complicated Streptococcus Agalactiae Sepsis with/without Meningitis in Young Infants and Newborns: The Clinical and Molecular Characteristics and Outcomes. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Cisneros, J.M.; Fernández-Cuenca, F.; Ribera, A.; Vila, J.; Pascual, A.; Martínez-Martínez, L.; Bou, G.; Pachón, J.; Grupo de Estudio de Infección Hospitalaria (GEIH). Clinical Features and Epidemiology of Acinetobacter baumannii Colonization and Infection in Spanish Hospitals. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2004, 25, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballouz, T.; Aridi, J.; Afif, C.; Irani, J.; Lakis, C.; Nasreddine, R.; Azar, E. Risk Factors, Clinical Presentation, and Outcome of Acinetobacter baumannii Bacteremia. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, K.; Müller, K.; Moter, A.; Baums, C.G.; Seydel, A. Streptococcus Suis Serotype 9 Endocarditis and Subsequent Severe Meningitis in a Growing Pig despite Specific Bactericidal Humoral Immunity. JMM Case Rep. 2017, 4, e005093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrea, V.; Páez-Triana, L.; Velásquez-Ortiz, N.; Camargo, M.; Patiño, L.H.; Vega, L.; Ballesteros, N.; Hidalgo-Troya, A.; Galeano, L.-A.; Ramírez, J.D.; et al. Metagenomic Analysis of Surface Waters and Wastewater in the Colombian Andean Highlands: Implications for Health and Disease. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, M.R.; Lepper, H.C.; McNally, L.; Wee, B.A.; Munk, P.; Warr, A.; Moore, B.; Kalima, P.; Philip, C.; de Roda Husman, A.M.; et al. Secrets of the Hospital Underbelly: Patterns of Abundance of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Hospital Wastewater Vary by Specific Antimicrobial and Bacterial Family. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 703560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, A.; Yadav, P.; Raj, A.; Ferreira, L.F.R.; Saratale, G.D.; Bharagava, R.N. Tannery Wastewater: A Major Source of Residual Organic Pollutants and Pathogenic Microbes and Their Treatment Strategies. In Microbes in Agriculture and Environmental Development; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, M.K.; Kumar, M.; Singhania, R.R.; Giri, B.S. Tannery Waste Management and Cleaner Production of Leather in Beam House and Tanning Section: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2025, 30, 102116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.K. Halotolerant Life in Feast or Famine: Organic Sources of Hydrocarbons and Fixers of Metals. In Evaporites: A Geological Compendium; Warren, J.K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 833–958. ISBN 978-3-319-13512-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, C.D.; Hennebique, A.; Peyroux, J.; Pelloux, I.; Caspar, Y.; Maurin, M. Presence of Francisella Tularensis Subsp. Holarctica DNA in the Aquatic Environment in France. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanekar, P.P.; Kanekar, S.P. Metallophilic, Metal-Resistant, and Metal-Tolerant Microorganisms. In Diversity and Biotechnology of Extremophilic Microorganisms from India; Kanekar, P.P., Kanekar, S.P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 187–213. ISBN 978-981-19-1573-4. [Google Scholar]

- Abayneh, M.; Zeynudin, A.; Tamrat, R.; Tadesse, M.; Tamirat, A. Drug Resistance and Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBLs)—Producing Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas Species from the Views of One-Health Approach in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. One Health Outlook 2023, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, Z.; Manik, M.R.K.; Rahman, A.; Karim, M.M.; Islam, L.N. Impact of Untreated Tannery Wastewater in the Evolution of Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria in Bangladesh. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.Q.; Zeeshan, N.; Ashraf, N.M.; Akhtar, M.A.; Ashraf, H.; Afroz, A.; Shaheen, A.; Naz, S. Environmental Impact and Diversity of Protease-Producing Bacteria in Areas of Leather Tannery Effluents of Sialkot, Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 54842–54851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka, K.; Skrzypczak, D.; Mikula, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A.; Izydorczyk, G.; Kuligowski, K.; Bandrów, P.; Kułażyński, M. Progress in Sustainable Technologies of Leather Wastes Valorization as Solutions for the Circular Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Tran, P.Q.; Cowley, E.S.; Trembath-Reichert, E.; Anantharaman, K. Diversity and Ecology of Microbial Sulfur Metabolism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 122–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Söderquist, B.; Jass, J. Prevalence and Diversity of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Swedish Aquatic Environments Impacted by Household and Hospital Wastewater. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.; Júnior, E.; Alegria, O.; Vieira, E.; Patroca, S.; Cecília, A.; Moreira, F.; Nunes, A. Metagenomics Insights into Bacterial Diversity and Antibiotic Resistome of the Sewage in the City of Belém, Pará, Brazil. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1466353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opitz-Ríos, C.; Burgos-Pacheco, A.; Paredes-Cárcamo, F.; Campanini-Salinas, J.; Medina, D.A. Metagenomics Insight into Veterinary and Zoonotic Pathogens Identified in Urban Wetlands of Los Lagos, Chile. Pathogens 2024, 13, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MADES. Padrón de Calidad de Aguas en el Territorio Nacional. In Resolución 222/02; MADES: Asunción, Paraguay, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Habibu, S.; Idris, M.B.; Birniwa, A.H.; Abdullahi, S.S.; Tukur, A.I.; Gumel, S.M. Chapter 2—Environmental Impact and Management of Industrial Effluents. In Biorefinery of Industrial Effluents for a Sustainable Circular Economy; Naushad, M., Mohamed Kutty, S.R., Hossain, M.S., Birniwa, A.H., Jagaba, A.H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 11–25. ISBN 978-0-443-21801-9. [Google Scholar]

- Olaniyan, T.O.; Martínez-Vázquez, A.V.; Escobedo-Bonilla, C.M.; López-Rodríguez, C.; Huerta-Luévano, P.; Castrejón-Sánchez, O.; de la Cruz-Flores, W.L.; Cedeño-Castillo, M.J.; de Luna-Santillana, E.d.J.; Cruz-Hernández, M.A.; et al. The Prevalence of ESKAPE Pathogens and Their Drug Resistance Profiles in Aquatic Environments Around the World. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.M.; Khan, M.K.; Mazhar, B.; Mustafa, M. Impact of Water Pollution on Waterborne Infections: Emphasizing Microbial Contamination and Associated Health Hazards in Humans. Discov. Water 2025, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, M.; Dubey, S.K. Antimicrobial Resistance Transmission in Environmental Matrices: Current Prospects and Future Directions. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2025, 263, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tang, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, X.; Yuan, H.; Gao, C.; Guo, Q.; Guo, X.; Wan, J.; Dagot, C. The Environmental Lifecycle of Antibiotics and Resistance Genes: Transmission Mechanisms, Challenges, and Control Strategies. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Dias, C.; Pereira, A.R.; de Oliveira Paranhos, A.G.; Rodrigues, M.V.D.; de Lima, W.G.; de Aquino, S.F.; de Queiroz Silva, S. Spread of Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in a Swine Wastewater Treatment Plant. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2023, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czatzkowska, M.; Wolak, I.; Harnisz, M.; Korzeniewska, E. Impact of Anthropogenic Activities on the Dissemination of ARGs in the Environment—A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.M.; Hayes, A.; Snape, J.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Gaze, W.H.; Murray, A.K. Co-Selection for Antibiotic Resistance by Environmental Contaminants. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayale, K.; Little, K.; Crawford, M.; Swatuk, L. Transboundary Groundwater Governance and Management: The Case of the Guarani Aquifer—Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay. In Water, Climate Change and the Boomerang Effect; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tujchneider, O.; Perez, M.; Paris, M.; D’Elia, M. The Guaraní Aquifer System: State-of-the-Art in Argentina. In Aquifer Systems Management: Darcy’s Legacy in a World of Impending Water Shortage; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Báez, L.; Ávalos, C.; von Lücken, C.; Villalba, C.; Nogués, J.P. Designing and Validating a Groundwater Sampling Campaign in an Unmonitored Aquifer: Patiño Aquifer Case. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, J.P.S.; Gupta, V.V.S.R.; Stange, C.; Ho, J.; Harris, N.; Barry, K.; Gonzalez, D.; Van Nostrand, J.D.; Zhou, J.; Page, D.; et al. Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence Genes in the Biofilms from an Aquifer Recharged with Stormwater. Water Res. 2020, 185, 116269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, C.; Casado, M.; Martinez-Landa, L.; Valhondo, C.; Amalfitano, S.; Di Pippo, F.; Levantesi, C.; Carrera, J.; Piña, B. Efficient Removal of Antibiotic Resistance Genes and of Enteric Bacteria from Reclaimed Wastewater by Enhanced Soil Aquifer Treatments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 953, 176078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekeres, E.; Chiriac, C.M.; Baricz, A.; Szőke-Nagy, T.; Lung, I.; Soran, M.-L.; Rudi, K.; Dragos, N.; Coman, C. Investigating Antibiotics, Antibiotic Resistance Genes, and Microbial Contaminants in Groundwater in Relation to the Proximity of Urban Areas. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 236, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.C.; Shaw, H.; Rhodes, V.; Hart, A. Review of Antimicrobial Resistance in the Environment and Its Relevance to Environmental Regulators. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christou, A.; Beretsou, V.G.; Iakovides, I.C.; Karaolia, P.; Michael, C.; Benmarhnia, T.; Chefetz, B.; Donner, E.; Gawlik, B.M.; Lee, Y.; et al. Sustainable Wastewater Reuse for Agriculture. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 504–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitton, G.; Harvey, R.W. Transport of Pathogens through Soils and Aquifers. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 19, 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Gufe, C.; Chari, T.A.; Jambwa, P.; Dinginya, L.; Mahlangu, P.; Marowero, S.T.; Majuru, C.S.; Kadungure, T.; Machakwa, J. A Review on the Occurrence of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Found in Abattoir Effluent from Resource-Limited Settings: The Necessity of a Robust One Health Framework. Sustain. Environ. 2025, 11, 2464419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, A.; Tanveer, H.; Shafiq, M.; Ihsan, M.; Maqbool, T.; Scholz, M. Horizontal Flow Floating Treatment Wetlands (HFFTWs) for Reclaiming Safer Irrigation Water from Tannery Effluent. Water 2025, 17, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Corona, C.G.; Gonzalez-Avila, L.U.; Hernández-Cortez, C.; Rojas-Vargas, J.; Castro-Escarpulli, G.; Castelán-Sánchez, H.G. Impact of Heavy Metal and Resistance Genes on Antimicrobial Resistance: Ecological and Public Health Implications. Genes 2025, 16, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.