Tourism Innovation Ecosystems: Insights from Theory and Empirical Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

- Barriers to Collaboration within the Ecosystem

- Barriers to Actor Integration

- Technology Acceptance

- Technology Adoption

- Innovation Generation through Collaboration and Integration in the Ecosystem

- Sustainability as a Consequence of Innovation

- Overall Ecosystem Performance

2.1. Barriers to Collaboration and Actor Integration in the Ecosystem

2.2. Technology Acceptance and Adoption

2.3. Innovation Generation, Sustainability, and Ecosystem Performance

3. Methodology

3.1. Empirical Study

3.2. Data Collection Instrument and Hypotheses

- 8.

- Barriers to Collaboration (Wirtz et al., 2019; Madanaguli et al., 2022)

- 9.

- Barriers to Integration (Luthe & Wyss, 2016; Morant-Martínez et al., 2019)

- 10.

- 11.

- Technology Adoption (Boes et al., 2016; Gretzel et al., 2015a; Buhalis et al., 2019; Khalifa et al., 2022; Buhalis et al., 2024)

- 12.

- Innovation Generation (Salvado et al., 2023; Morant-Martínez et al., 2019)

- 13.

- 14.

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Pilot Study in the Las Vegas Tourism Innovation Ecosystem

4.2. Measurement Model Validation in the Orlando Tourism Innovation Ecosystem

4.3. Final Analysis and Hypothesis Validation

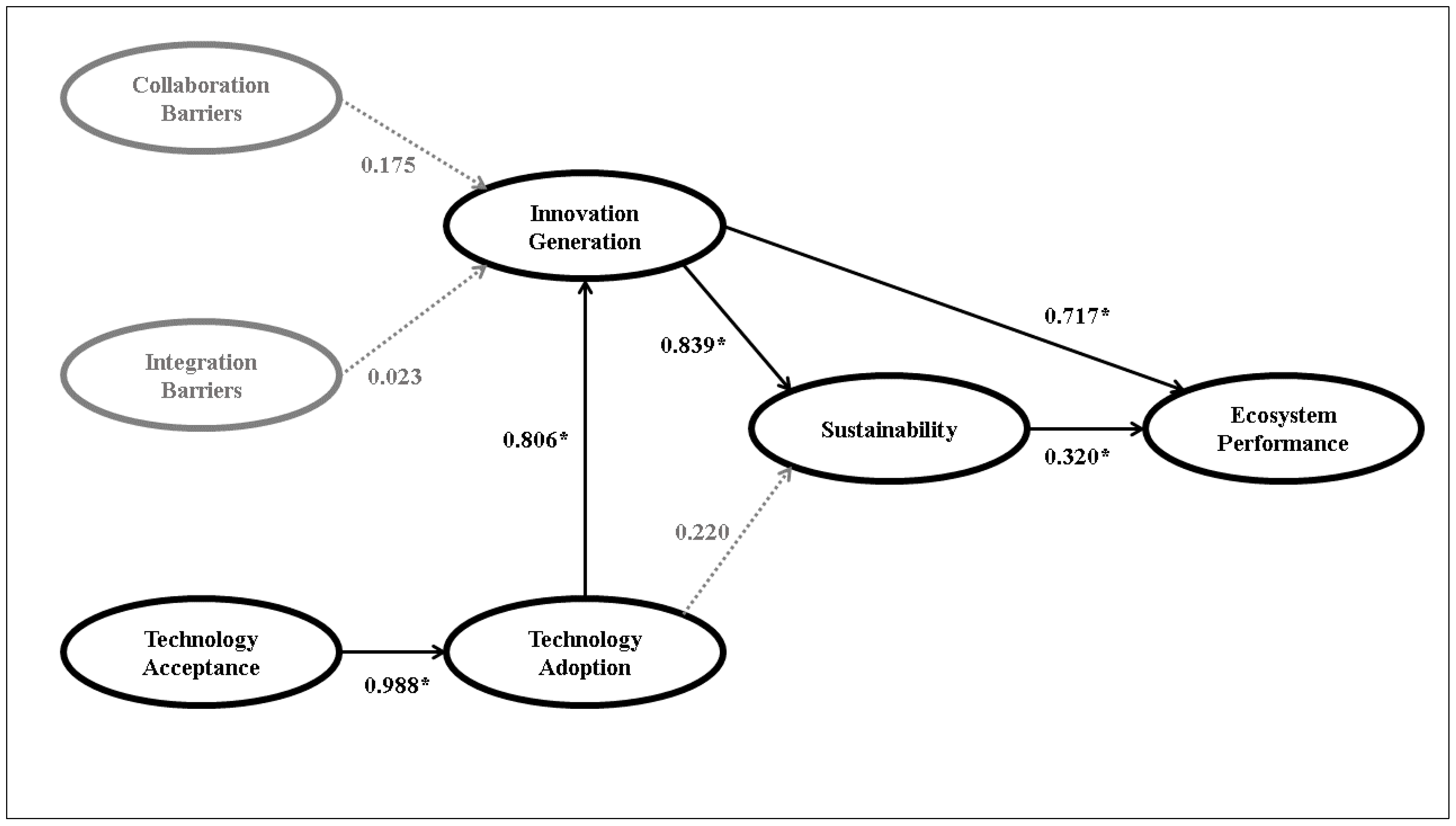

- Technology Adoption: R2 = 0.415

- Innovation Generation: R2 = 0.556

- Sustainability: R2 = 0.312

- Ecosystem Performance: R2 = 0.619

5. Final Considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adner, R. (2006). Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harvard Business Review, 84(4), 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (2012). Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(1), 8–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbetta, P. A. (2002). Estatística aplicada às ciências sociais (8th ed.). UFSC. [Google Scholar]

- Boes, K., Buhalis, D., & Inversini, A. (2016). Smart tourism destinations: Ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 2(2), 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. (2020). Technology in tourism-from information communication technologies to eTourism and smart tourism towards ambient intelligence tourism: A perspective article. Tourism Review, 75(1), 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., & Amaranggana, A. (2015). Smart tourism destinations enhancing tourism experience through personalisation of services. In Information and communication technologies in tourism 2015: Proceedings of the international conference in Lugano, Switzerland, February 3–6, 2015 (pp. 377–389). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D., Efthymiou, L., Uzunboylu, N., & Thrassou, A. (2024). Charting the progress of technology adoption in tourism and hospitality in the era of industry 4.0. EuroMed Journal of Business, 19(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., Harwood, T., Bogicevic, V., Viglia, G., Beldona, S., & Hofacker, C. (2019). Technological disruptions in services: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. Journal of Service Management, 30(4), 484–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D., & Sinarta, Y. (2019). Real-time co-creation and nowness service: Lessons from tourism and hospitality. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(5), 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business View Magazine. (2024, July 29). Orlando, Florida—The city beautiful. Business View Magazine. Available online: https://businessviewmagazine.com/orlando-florida/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Chakraborty, P. P. (2024). The role of technology in enhancing sustainable tourism practices: Innovations and impacts. In Special interest trends for sustainable tourism (pp. 195–230). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Collado-Agudo, J., Herrero-Crespo, Á., & San Martín-Gutiérrez, H. (2023). The adoption of a smart destination model by tourism companies: An ecosystem approach. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 28, 100783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D. R., & Schindler, P. S. (2016). Métodos de pesquisa em administração-12ª edição. McGraw Hill Brasil. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, C., Kastenholz, E., & Carneiro, M. J. (2020). Entrepreneurs in rural tourism: Do lifestyle motivations contribute to management practices that enhance sustainable entrepreneurial ecosystems? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 44, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Chiappa, G., & Baggio, R. (2015). Knowledge transfer in smart tourism destinations: Analyzing the effects of a network structure. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(3), 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, C., & Morgan, G. B. (2014). A comparison of diagonal weighted least squares robust estimation techniques for ordinal data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichelberger, S., Peters, M., Pikkemaat, B., & Chan, C. S. (2020). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in smart cities for tourism development: From stakeholder perceptions to regional tourism policy implications. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. (2009). Descobrindo a Estatística Usando o SPSS (L. Viali, Trans.; 2nd ed.). Grupo A-Bookman. [Google Scholar]

- Flora, D. B. (2020). Your coefficient alpha is probably wrong, but which coefficient omega is right? A tutorial on using R to obtain better reliability estimates. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 3(4), 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L. A., Facin, A. L. F., Salerno, M. S., & Ikenami, R. K. (2018). Unpacking the innovation ecosystem construct: Evolution, gaps and trends. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 136, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U., Sigala, M., Xiang, Z., & Koo, C. (2015a). Smart tourism: Foundations and developments. Electronic Markets, 25(3), 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U., Werthner, H., Koo, C., & Lamsfus, C. (2015b). Conceptual foundations for understanding smart tourism ecosystems. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2009). Análise multivariada de dados. Bookman Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalager, A. M. (2010). A review of innovation research in tourism. Tourism Management, 31(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjalager, A. M., Kwiatkowski, G., & Østervig Larsen, M. (2018). Innovation gaps in Scandinavian rural tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Yang, F. (2013). Nonlinear structural equation models: The Kenny–Judd model with interaction effects. In Advanced structural equation modeling (pp. 57–88). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, M. G., Tay, L., & Harms, P. D. (2017). Systems perspective on Amazon Mechanical Turk for organizational research: Review and recommendations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A. A., Ibrahim, A. J., Amhamed, A. I., & El-Naas, M. H. (2022). Accelerating the transition to a circular economy for net-zero emissions by 2050: A systematic review. Sustainability, 14(18), 11656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinova, S. (2019). Digital transformation in tourism. International Journal of Knowledge, 35(1), 188–193. [Google Scholar]

- Lavorel, S., Colloff, M. J., Locatelli, B., Gorddard, R., Prober, S. M., Gabillet, M., & Peyrache-Gadeau, V. (2019). Mustering the power of ecosystems for adaptation to climate change. Environmental Science & Policy, 92, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LSE Impact Blog. (2020). How to conduct valid social science research using MTurk: A checklist. London School of Economics and Political Science. Available online: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2020/12/15/how-to-conduct-valid-social-science-research-using-mturk-a-checklist/ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Luthe, T., & Wyss, R. (2016). Resilience to climate change in a cross-scale tourism governance context: A combined quantitative-qualitative network analysis. Ecology and Society, 21(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanaguli, A., Kaur, P., Mazzoleni, A., & Dhir, A. (2022). The innovation ecosystem in rural tourism and hospitality—A systematic review of innovation in rural tourism. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(7), 1732–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, N. K., Do, T. T., & Tran, P. M. (2023). How leadership competences foster innovation and high performance: Evidence from tourism industry in Vietnam. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 6(3), 1253–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. F. (1993). Predators and prey: A new ecology of competition. Harvard Business Review, 71(3), 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Morant-Martínez, O., Santandreu-Mascarell, C., Canós-Darós, L., & Millet Roig, J. (2019). Ecosystem model proposal in the tourism sector to enhance sustainable competitiveness. Sustainability, 11(23), 6652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro Visconti, R. (2020). Corporate governance, digital platforms, and network theory: Information and risk-return sharing of connected stakeholders. Management Control, 2, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, K., & Hughes, T. L. (2018). Comparing Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform to conventional data collection methods in the health and medical research literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(4), 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando Economic Partnership. (n.d.). Innovation in Orlando. Orlando Economic Partnership. Available online: https://orlando.org/l/innovation/ (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Pencarelli, T. (2020). The digital revolution in the travel and tourism industry. Information Technology & Tourism, 22(3), 455–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkemaat, B., & Zehrer, A. (2016). Innovation and service experiences in small tourism family firms. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 10(4), 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, F., Botti, A., Grimaldi, M., Monda, A., & Vesci, M. (2018). Social innovation in smart tourism ecosystems: How technology and institutions shape sustainable value co-creation. Sustainability, 10(1), 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, I., Williams, A. M., & Hall, C. M. (2014). Tourism innovation policy: Implementation and outcomes. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvado, J., Kastenholz, E., Cunha, D., & Cunha, C. (2023). The stakeholder-entrepreneur value-cocreation pyramid in wine tourism: Taking supplier collaboration to the next level. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento (RT&D)/Journal of Tourism & Development, (43), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampieri, R. H., Collado, C. F., & Lucio, P. B. (2006). Metodologia de pesquisa. In Metodologia de pesquisa (5th ed., pp. xxiv–583). Penso. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M. (2023). Thriving in wine tourism through technology and innovation: A survival or a competitiveness need? In Technology advances and innovation in wine tourism: New managerial approaches and cases (pp. 3–11). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Sotirofski, I. (2024). Understanding innovation ecosystems. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research and Development, 11(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stare, M., & Križaj, D. (2018). Evolution of an innovation network in tourism: Towards sectoral innovation eco-system. Amfiteatru Economic, 20(48), 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, J., So, K. K. F., Mody, M. A., Liu, S. Q., & Chun, H. H. (2019). Platforms in the peer-to-peer sharing economy. Journal of Service Management, 30(4), 452–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, I. D., Brown, G., & Wohlfart, T. (2018). Applying public participation GIS (PPGIS) to inform and manage visitor conflict along multi-use trails. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(3), 470–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., & Gearhart, S. (2023). Comparing Amazon’s MTurk and a SONA student sample: A test of data quality using attention and manipulation checks. Survey Practice, 16(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R., Zhen, S., Mei, L., & Jiang, H. (2021). Ecotourism practices in potatso national park from the perspective of tourists: Assessment and developing contradictions. Sustainability, 13(22), 12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Structure | Factor Loadings | AVE | McDonald’s Omega |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration Barriers | 4 itens | 0.714~0.797 | 0.598 | 0.852 |

| Integration Barriers | 4 itens | 0.674~0.798 | 0.565 | 0.836 |

| Innovation Generation through Collaboration and Integration | 4 itens | 0.676~0.791 | 0.533 | 0.808 |

| Technology Acceptance | 5 itens | 0.693~0.757 | 0.518 | 0.828 |

| Technology Adoption | 5 itens | 0.654~0.765 | 0.537 | 0.840 |

| Sustainability | 4 itens | 0.678~0.774 | 0.531 | 0.813 |

| Innovation Ecosystem Performance | 5 itens | 0.677~0.766 | 0.518 | 0.824 |

| Characteristic | n | % | Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Job title in the tourism sector | ||||

| Female | 119 | 33.00 | Entrepreneur | 128 | 35.50 |

| Male | 242 | 67.00 | Manager | 126 | 34.90 |

| Generational age group | Government Representative | 38 | 10.50 | ||

| Generation Z (ages 18–29) | 90 | 24.90 | Academic | 20 | 5.50 |

| Generation Y (ages 30–43) | 231 | 64.00 | Researcher | 40 | 11.10 |

| Generation X (ages 44–59) | 40 | 11.10 | Local Community | 9 | 2.50 |

| Educational level | Years of experience | ||||

| Primary education (completed) | 4 | 1.10 | Up to 3 years | 184 | 51.00 |

| Technical course | 9 | 2.50 | 3 to 5 years | 109 | 30.20 |

| Incomplete higher education | 6 | 1.70 | More than 5 years | 68 | 18.80 |

| Completed higher education | 190 | 52.60 | Participation in the ecosystem | ||

| Postgraduate degree | 152 | 42.10 | Never | 5 | 1.40 |

| Employment sector | Occasionally | 79 | 21.90 | ||

| Private sector | 274 | 75.90 | Frequently | 277 | 76.70 |

| Public sector | 87 | 24.10 |

| Dimension | Items | Factor Loadings | AVE | McDonald’s Omega |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration Barriers | COLAB01 | 0.728 | 0.542 | 0.796 |

| COLAB02 | 0.730 | |||

| COLAB03 | 0.716 | |||

| COLAB04 | 0.768 | |||

| Integration Barriers | INTEG01 | 0.692 | 0.514 | 0.737 |

| INTEG03 | 0.745 | |||

| INTEG04 | 0.715 | |||

| Innovation Generation through Collaboration and Integration | GERACAO02 | 0.708 | 0.507 | 0.768 |

| GERACAO03 | 0.697 | |||

| GERACAO04 | 0.718 | |||

| GERACAO05 | 0.706 | |||

| Technology Acceptance | ACEITA01 | 0.751 | 0.534 | 0.744 |

| ACEITA03 | 0.679 | |||

| ACEITA05 | 0.719 | |||

| Technology Adoption | ADOCAO01 | 0.720 | 0.547 | 0.841 |

| ADOCAO02 | 0.713 | |||

| ADOCAO03 | 0.710 | |||

| ADOCAO04 | 0.746 | |||

| ADOCAO05 | 0.752 | |||

| Sustainability | SUSTEN01 | 0.705 | 0.516 | 0.785 |

| SUSTEN02 | 0.746 | |||

| SUSTEN03 | 0.712 | |||

| SUSTEN04 | 0.726 | |||

| Innovation Ecosystem Performance | AVALIA01 | 0.740 | 0.537 | 0.790 |

| AVALIA03 | 0.702 | |||

| AVALIA04 | 0.744 | |||

| AVALIA05 | 0.745 |

| SECONDARY HYPOTHESES | Relationship Coefficient | S.E. | p-Value | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H01 | Collaboration Barriers => Innovation Generation | 0.175 | 0.276 | 0.526 | Not Supported |

| H02 | Integration Barriers => Innovation Generation | 0.023 | 0.259 | 0.930 | Not Supported |

| H03 | Technology Acceptance => Technology Adoption | 0.988 | 0.014 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H04 | Technology Adoption => Innovation Generation | 0.806 | 0.071 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H05 | Technology Adoption => Sustainability | 0.220 | 0.416 | 0.596 | Not Supported |

| H06 | Innovation Generation => Sustainability | 0.839 | 0.415 | 0.043 | Supported |

| H07 | Innovation Generation => Ecosystem Performance | 0.717 | 0.150 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H08 | Sustainability => Ecosystem Performance | 0.320 | 0.144 | 0.026 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coelho de Souza Filho, J.J.; dos Anjos, S.J.G.; dos Anjos, F.A.; Kuhn, V.R. Tourism Innovation Ecosystems: Insights from Theory and Empirical Validation. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050272

Coelho de Souza Filho JJ, dos Anjos SJG, dos Anjos FA, Kuhn VR. Tourism Innovation Ecosystems: Insights from Theory and Empirical Validation. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):272. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050272

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoelho de Souza Filho, Jairo Jeronimo, Sara Joana Gadotti dos Anjos, Francisco Antônio dos Anjos, and Vitor Roslindo Kuhn. 2025. "Tourism Innovation Ecosystems: Insights from Theory and Empirical Validation" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050272

APA StyleCoelho de Souza Filho, J. J., dos Anjos, S. J. G., dos Anjos, F. A., & Kuhn, V. R. (2025). Tourism Innovation Ecosystems: Insights from Theory and Empirical Validation. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 272. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050272