Accommodation Tax as a Tool of Financial Management of Destination: Insights from Selected European Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Context and Case Selection

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Analytical Methods

3.4. Comparative Benchmarking

- (1)

- Funding structure (share of accommodation tax in total DMO revenue),

- (2)

- Governance model (degree of decentralization and stakeholder composition),

- (3)

- Fiscal intensity (approximate accommodation tax per overnight stay and per capita),

- (4)

- Institutional maturity (years since national DMO legislation and coverage of local DMOs).

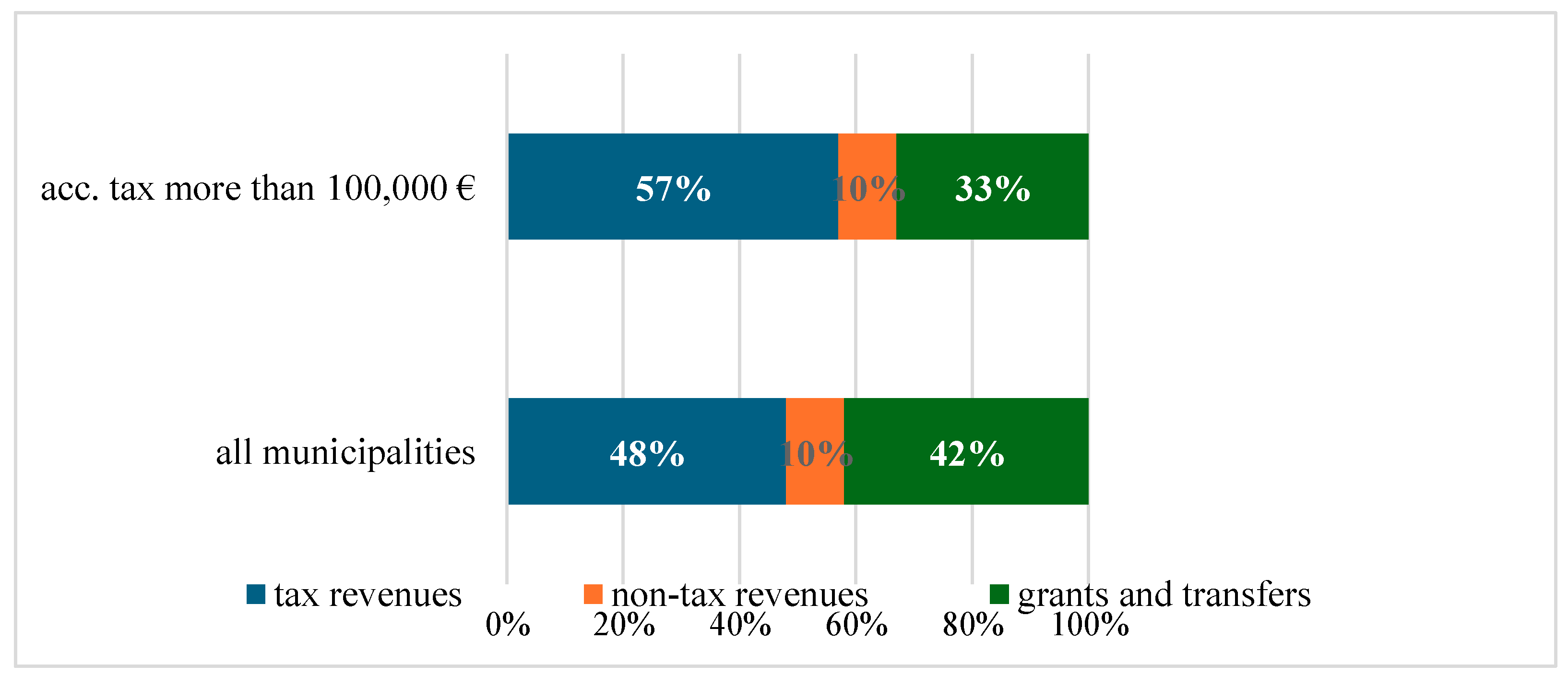

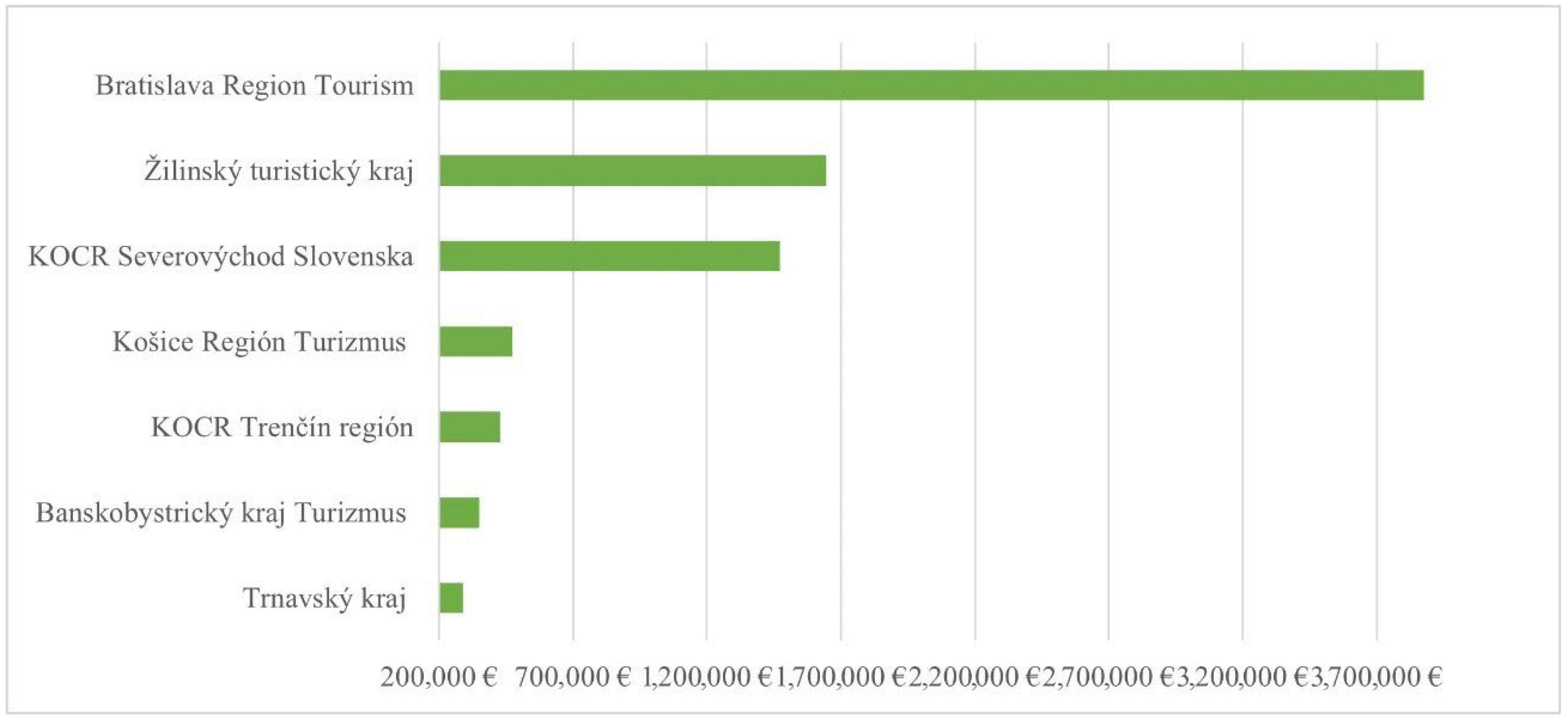

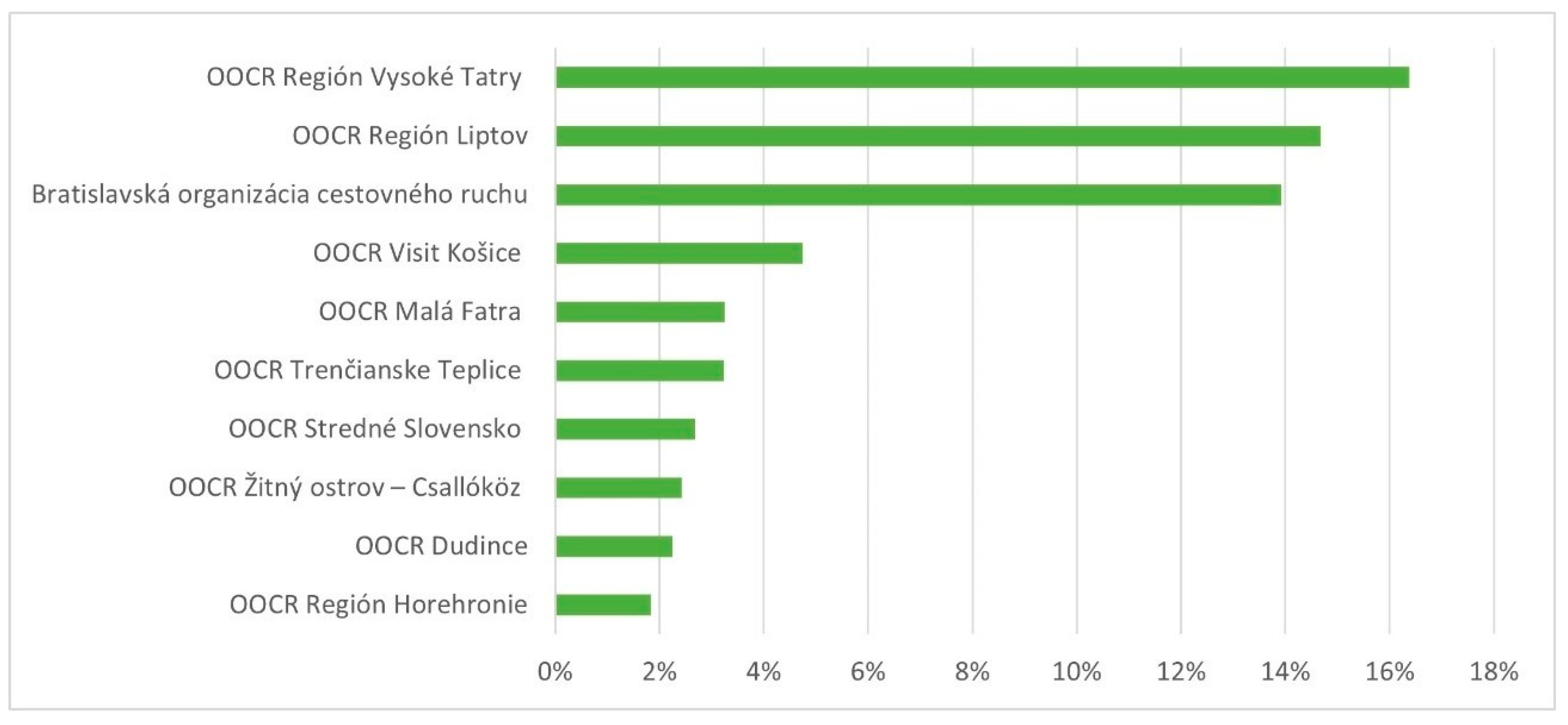

4. Results

5. Discussion

- Redesign subsidy allocation rules to avoid reinforcing spatial inequalities.

- Support revenue-smoothing mechanisms or reserve funds to manage seasonal volatility.

- Encourage DMOs to expand their own-income activities to improve long-term resilience.

6. Conclusions

- Theoretically, the study extends existing models of destination governance by incorporating post-transition contexts.

- Practically, it emphasizes the importance of transparent allocation, stakeholder participation, and diversification of DMO funding sources.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| DMO | Destination Management Organization |

| RevPar | Revenue Per Available Room |

| EU | European Union |

| EUR | Euro |

| Acc | Accommodation |

| LTO | Local Tourism Organisation |

References

- Aguiló, E., Riera, A., & Rosselló, J. (2005). The short-term price effect of a tourist tax through a dynamic demand model: The case of the Balearic Islands. Tourism Management, 26, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfano, V., De Simone, E., D’Uva, M., & Gaeta, G. L. (2022). Exploring motivations behind the introduction of tourist accommodation taxes: The case of the Marche region in Italy. Land Use Policy, 113, 105181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguea, N. M., & Hawkins, R. R. (2015). The rate elasticity of Florida tourist development (aka bed) taxes. Applied Economics, 47(18), 1823–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baños-Pino, J. F., Zapico, E., Mayor, M., & Balado-Naves, R. (2024). The design of an eco-tax on tourism waste for sustainable destinations, based on environmental efficiency and spatial dependence. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 33(10), 2202–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beritelli, P., & Laesser, C. (2018). Destination logo recognition and implications for intentional destination branding by DMOs: A case for saving money. Journal of destination marketing & management, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Biagi, B., Brandano, M. G., & Pulina, M. (2016). The effect of tourism taxation: A synthetic control approach (Working Paper CRENoS 201609). Centre for North South Economic Research, University of Cagliari and Sassari, Sardinia. [Google Scholar]

- Biagi, B., Brandano, M. G., & Pulina, M. (2021). Tourism taxation: Good or bad for cities? In M. Ferrante, O. Fritz, & Ö. Öner (Eds.), Regional science perspectives on tourism and hospitality. Advances in spatial science (pp. 477–505). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bonham, C. S., & Gangnes, B. (1996). Intervention analysis with cointegrated time series: The case of the Hawaii hotel room tax. Applied Economics, 28(10), 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantallops, A. S. (2004). Policies supporting sustainable tourism development in the Balearic Islands: The Ecotax. Anatolia, 15(1), 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-García, P. J., Pulido-Fernández, J. I., Durán-Román, J. L., & Carrillo-Hidalgo, I. (2022). Tourist taxation as a sustainability financing mechanism for mass tourism destinations. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, G., Alrawadieh, Z., Dincer, M. Z., Istanbullu Dincer, F., & Ioannides, D. (2017). Willingness to pay for tourist tax in destinations: Empirical evidence from Istanbul. Economies, 5(2), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. J., Qiu, R. T. R., Jiao, X., Song, H., & Li, Y. (2023). Tax deduction or financial subsidy during crisis?: Effectiveness of fiscal policies as pandemic mitigation and recovery measures. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights, 4(2), 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Combs, J., & Elledge, B. (1979). Effects of a room tax on resort hotel/motels. National Tax Journal, 32, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancey, C. P., & Reidy, J. (2017). Statistics without maths for psychology (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- do Valle, P., Pintassilgo, P., Matias, A., & Andre, F. (2012). Tourism attitudes towards an accommodation tax earmarked for environmental protection: A survey in the Algarve. Tourism Management, 33, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Román, J. L., Cárdenas-García, P. J., & Pulido-Fernández, J. I. (2021). Tourist tax to improve sustainability and the experience in mass tourism destinations: The case of Andalusia (Spain). Sustainability, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbarry, R. (2008). Tourism taxes: Implications for tourism demand in the UK. Review of Development Economics, 12(1), 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2017). The impact of taxes on the competitiveness of European tourism. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/130660/The%20Impact%20of%20Taxes%20on%20the%20Competitiveness%20of%20European%20tourism.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- European Tourism Association, Group NAO & Global Destination Sustainability Movement. (2024). Tourism taxes by design. Available online: https://groupnao.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/TOURISM-TAXES-BY-DESIGN-NOV12-2020_rettet-compressed-2.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Eurostat. (2023). Tourism satellite accounts in Europe—2023 edition. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/7870049/16527548/KS-FT-22-011-EN-N.pdf/c0fa9583-b1c9-959a-9961-94ae9920e164?version=4.0&t=1683792112888 (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Federal Statistical Office Switzerland. (2023). Swiss tourism statistics 2023. Swiss Federal Statistical Office (SFSO). [Google Scholar]

- Gago, A., Labandeira, X., Picos, F., & Rodríguez, M. (2009). Specific and general taxation of tourism activities: Evidence from Spain. Tourism Management, 30(3), 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdošík, T., Gajdošíková, Z., Maráková, V., & Borseková, K. (2017). Innovations and networking fostering tourist destination development in Slovakia. Quaestiones Geographicae, 36(4), 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooroochurn, N., & Sinclair, M. T. (2005). Economics of tourism taxation—Evidence from Mauritius. Annals of Tourism Research, 32, 478–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göktaş, L., & Çetin, G. (2023). Tourist tax for sustainability: Determining willingness to pay. European Journal of Tourism Research, 35, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göktaş, L., & Polat, S. (2019). Tourist tax practices in European Union member countries and its applicability in Turkey. Journal of Tourismology, 5(2), 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Göktaş, L. S., & Erdem, A. (2024). Determination of accommodation tax spending areas using the SWARA method. Journals Serie A: Advancements in Tourism, Recreation and Sports Sciences (ATRSS), 7(2), 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guix, M., Babakhani, N., & Sun, Y. Y. (2024). Doing all we can? Destination management organizations’ net-zero pledges and their decarbonization plans. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 33(8), 1730–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gúčik, M., & Hornok, M. (2021). Accommodation tax as a source of revenue for budgets of local municipalities and tourism support in the Slovak Republic. In Wybrane aspekty działalności pozaprodukcyjnej na obszarach przyrodniczo cennych (pp. 161–171). Wydawnictwo Ekomomia a Środowisko. ISBN 978-83-942623-8-9. [Google Scholar]

- Heffer-Flaata, H., Voltes-Dorta, A., & Suau-Sanchez, P. (2021). The impact of accommodation taxes on outbound travel demand from the United Kingdom to European destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 60(4), 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, G. V., Grama, V., Ilieș, A., Safarov, B., Ilieș, D. C., Josan, I., Buzrukova, M., Janzakov, B., Privitera, D., & Dehoorne, O. (2023). The relationship between motivation and the role of the night of the museums event: Case study in Oradea municipality, Romania. Sustainability, 15(2), 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, G. V., Wendt, J. A., Dumbravă, R., & Gozner, M. (2019). The role and importance of promotion centers in creating the image of tourist destination: Romania. Geographia Polonica, 92, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornok, M. (2019). Potenciál dane za ubytovanie na Slovensku. Potential of accommodation tax in Slovakia. Ekonomická Revue Cestovného Ruchu, 52(2), 78–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hornok, M. (2021a). Analýza návštevnosti ubytovacích zariadení a výnosu dane za ubytovanie. Ekonomická Revue Cestovného Ruchu, 54(4), 216–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hornok, M. (2021b). Výnos dane za ubytovanie na Slovensku v rokoch 2019 a 2020. Accommodation tax revenue in Slovakia 2019 and 2020. Ekonomická Revue Cestovného Ruchu, 54(2), 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hornok, M. (2022). Analýza výnosu dane za ubytovanie. Analysis of accommodation tax revenue. Ekonomická Revue Cestovného Ruchu, 55(4), 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeji, T., & Yamada, Y. (2020). How to gain accommodation managers’ support for accommodation tax? Exploring the mediating role of perceived fairness. Travel and tourism research association: Advancing tourism research globally. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/entities/publication/1cfc94b0-7d13-4892-8c4b-a22a36d83efe (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Laesser, C., Küng, B., Beritelli, P., Boetsch, T., & Weilenmann, T. (2023). Tourismus-destinationen: Strukturen und aufgaben sowie herausforderungen und perspektiven. Bericht im Auftrag des Staatssekretariats für Wirtschaft SECO. SECO. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. K. (2014). Revisiting the impact of bed tax with spatial panel approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 41, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, J., & Nishimura, E. (1979). The economics of a hotel room tax. Journal of Travel Research, 17(4), 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notaro, S., Grilli, G., & Paletto, A. (2018). The role of emotions on tourists’ willingness to pay for the Alpine landscape: A latent class approach. Landscape Research, 44(6), 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R. (2015). Tourism development and trust in local government. Tourism Management, 46, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2011). Residents’ satisfaction with community attributes and support for tourism. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 35(2), 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2021). OECD revenue statistics 2021: The tax revenue database. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/revenue-statistics-2021_6e87f932-en.html (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- OECD. (2022). Slovak Republic: OECD tourism trends and policies 2022—Country-specific governance description and budgeting figures. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-tourism-trends-and-policies-2022_a8dd3019-en/full-report.html (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- OECD. (2024a). Tourism trends and policies 2024—Governance and policy notes on DMOs and funding. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2024b). Tourism trends and policies; Guidance to strengthen DMO structures in Croatia. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Rodríguez, C., Vena-Oya, J., Barreal, J., & Józefowicz, B. (2024). How to finance sustainable tourism: Factors influencing the attitude and willingness to pay green taxes among university students. Green Finance, 6(4), 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, T., & Riera, A. (2003). Tourism and environmental taxes. With special reference to the “Balearic ecotax”. Tourism Management, 24, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piriyapada, S., & Wang, E. (2015). Modeling willingness to pay for coastal tourism resource protection in Ko Chang Marine National Park, Thailand. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(5), 515–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponjan, P., & Thirawat, N. (2016). Impacts of Thailand’s tourism tax cut: A CGE analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 61, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, S., Laesser, C., & Beritelli, P. (2018). The 2016 consensus on advances in destination management. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 426–431. [Google Scholar]

- Rosselló-Nadal, J., & Sansó, A. (2017). Taxing Tourism: The effects of an accommodation tax on tourism demand in the Balearic Islands. Cuadernos Economicos, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandford, M. (2024). Tourist taxes: Policy and debates. Available online: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-10158/CBP-10158.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Sharma, A., Perdue, R. R., & Nicolau, J. L. (2022). The effect of lodging taxes on the performance of US hotels. Journal of Travel Research, 61(1), 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L., & Tsui, Y. (2009). Taxing tourism: Enhancing or reducing welfare? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 17(5), 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J. R. R., Remoaldo, P., Perinotto, A. R. C., Gabriel, L. P. M. C., Lezcano-González, M. E., & Sánchez-Fernández, M.-D. (2022). Residents’ perceptions regarding the implementation of a tourist tax at a UNESCO World Heritage site: A cluster analysis of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). Land, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sour, L., & Arcos, S. (2024). Comparative analysis of stochastic frontier efficiency in payroll and accommodation tax collection in Mexico (2010–2020). Apuntes del Cenes, 43(78), 181–206. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. (2023). Tourism satellite account 2023. Bratislava. Available online: https://slovak.statistics.sk/wps/portal/ext/products/informationmessages/!ut/p/z1/pVXLbtswEPyWfoGW4ks-UopFMaQVPSgl1aXwoSgMtE4OQdHPL6O4BSQ6aweWTgJn9jHcHSVT8pRMx_3vw4_96-H5uP8Zvr9O4tvomizPiYKHjpTQAtjaZt6IUSSPM6DQqmLSAWROczCqGrpNSykomkzX8OGDR8F1_Faad0DGJYCp-wFg7KHXZOZ_dKzkBX4ALPn5mIKRdUds22pL2JqvqyEL_By03jgChVzV3w8qHHeGFy6neoQo_yKBGgSWX1XkxP-fQEtPQoLQwJi1dFvyZf7l8ZBeyE9ytH9SC5z_JtCyf0HCpXbc8dwJCkKu618Bovn5JF9IrP9dkAfVb0fpbfy1_sv7D8Wi86fbil7HRwALflbtQnmla8Zm64mESL8YgOyP7VN8f6xlt_EDAOF7Q3G-B3Yb36z1L3MBretqCANOoWCR_hHgc_619A92z6_jI4AJt9f--zHEmFCZ3lREfRTgBCj7JlUbpou77qEE44s0651IAcgJgP0oLpWK16DJGnDGi5EI78uGAZTnESC2a1QH_Q-AGTYKqAGvYbZstM2G4RHsINc1nHFlzFe6EfAuZl9FAZ7hKSRwfB5m68HmgeUiimCLIgC4v-NjTZvtpQhhO19-DWefpz_msHq__AWjI7wP/dz/d5/L2dJQSEvUUt3QS80TmxFL1o2X0FRUVFTTFZWMEdWMkYwSTMxRzBOVVUwMEI2/?1dmy&urile=wcm%3Apath%3A/Obsah-EN-INF-AKT/informativne-spravy/vsetky/2ad9ac6b-a99b-41a1-b10b-f95331e17f8e (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Stiglitz, J. E., & Rosengard, J. K. (2015). Economics of the public sector (4th ed.). W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Sunaningsih, S. N., Nugraheni, A. P., Simamora, A. J., Hartono, B., & Sitoresmi, M. W. (2024). Tourism seasonality and tax compliance of hotel and accommodation sector in Magelang Regency, Indonesia: Mediating role of intention to comply. Journal of Accounting and Investment, 25(3), 1005–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeri, M., & Baggio, R. (2021). Knowledge management in tourism: Paradigms, approaches and methods Editorial. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 35(2), 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2025). Tourism and competitiveness. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/competitiveness/brief/tourism-and-competitiveness#:~:text=In%202024%2C%20tourism%20accounted%20for%2010%20percent%20of,highlighting%20its%20central%20role%20in%20the%20labor%20market (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- WTTC. (2025). Travel & tourism to create 4.5MN new jobs across the EU by 2035, says WTTC. Available online: https://wttc.org/news/travel-and-tourism-to-create-4-5mn-new-jobs-across-the-eu-by-2035 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Yu, J., Safarov, B., Yi, L., Buzrukova, M., & Janzakov, B. (2023). The adaptive evolution of cultural ecosystems along the Silk Road and cultural tourism heritage: A case study of 22 cultural sites on the Chinese section of the Silk Road World Heritage. Sustainability, 15(3), 2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Goals/Aims | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Lee (2014) | Assess the impact of the hotel occupancy tax introduction in 2007 on Midland hotels in Texas, compared to the adjacent Odessa lodging submarket. | Midland hotels performed worse compared to the Odessa lodging submarket after the tax introduction. |

| Arguea and Hawkins (2015) | Analyze the elasticity of bed tax base across Florida counties (1997–2012) in response to tax rate increase. | A large short-run decline was observed in the hotel tax base due to a tax rate increase. |

| Biagi et al. (2016) | Study effects of tourism tax on tourist flows in Sardinia, Italy (2006–2011), focusing on domestic vs. international demand. | Tourism tax led to a decline in domestic tourist demand but not in international demand. |

| European Commission (2017) | Recommend a reduction in tourism taxes to enhance destination competitiveness and support tourism. | Reduction in tourism taxes is suggested to improve destination competitiveness and support tourism. |

| Notaro et al. (2018) | Examine the willingness of tourists to pay tourist tax to support local development initiatives in the Italian Alps. | Tourists are willing to pay tourist tax to support local development initiatives. |

| Sharma et al. (2022) | Explore effects of lodging taxes on hotel performance (RevPar) in the US, focusing on group vs. transient bookings. | Lodging taxes have a more negative effect on hotel performance (RevPar) for group bookings than for transient bookings. |

| Biagi et al. (2021) | Examine how the tourist tax affects tourism demand in Italy (Rome, Florence, Padua) using time series analysis, static CGE method, DD approach, and placebo analysis. | Tourists in Italy are not sensitive to price increases due to the tourist tax. |

| Heffer-Flaata et al. (2021) | Investigate the elasticity of visitor demand to accommodation taxes for UK travelers to Spanish, French, and Italian destinations (2012–2018). | UK international tourists are sensitive to hotel taxes, with varying impacts between peak and off-peak periods and across destination countries. |

| Alfano et al. (2022) | Explore factors influencing the adoption of tourist accommodation tax in Italian municipalities. | Probability of introducing tourist accommodation tax linked to municipality size, fiscal conditions, tourist attractiveness, electoral disproportionality, and strategic interactions. |

| Soares et al. (2022) | Investigate the perception of tourist tax implementation in Santiago de Compostela and suggest future tourism strategies. | Positive perception of tourist tax implementation in Santiago de Compostela, suggesting future tourism strategies to mitigate negative effects and enhance the resident–visitor relationship. |

| L. Göktaş and Çetin (2023) | Determine tourists’ willingness to pay tourist tax and identify factors affecting willingness in Turkey. | Tourists’ willingness to pay tourist tax depends on the expenditure items specified, cultural heritage support scenario, socio-demographics, knowledge level, travel content, and behavioral factors. |

| Chen et al. (2023) | Assess the effectiveness of tax reduction and financial subsidies for residents in facilitating post-pandemic tourism recovery. | Tax reduction and financial subsidies for residents have been found ineffective in facilitating a quick post-pandemic tourism recovery. Other policy measures are suggested. |

| Sour and Arcos (2024) | Assess the effectiveness of accommodation tax collection at the state level in Mexico from 2010 to 2020. | States with beachfront locations and tourist attractions tend to exhibit greater efficiency in collecting accommodation taxes. |

| Study | Main Findings |

|---|---|

| Palmer and Riera (2003) | Suggested that an occupancy tax on tourism stays could address negative externalities from tourism and support resource preservation efforts. |

| Gooroochurn and Sinclair (2005) | Proposed that an accommodation tax could potentially alleviate congestion issues in tourist destinations. |

| Gago et al. (2009) | Supported the idea that an accommodation tax could alleviate congestion issues in tourist destinations. |

| Sheng and Tsui (2009) | Highlighted the role of destination market power in determining the impact of tourism taxes on social welfare, suggesting that considering broader social and environmental contexts could enhance their welfare benefits. |

| do Valle et al. (2012) | Discovered that sun-and-beach tourists were generally unwilling to pay accommodation taxes, while environmentally conscious and nature-oriented tourists showed more willingness. |

| Ponjan and Thirawat (2016) | Demonstrated that tourism tax cuts could mitigate the adverse effects of natural disasters on tourism. |

| Cetin et al. (2017) | Visitors are more likely to pay a tax when this improves their experiences, but they do not want to take on liability concerning matters relating to destination sustainability. |

| Durán-Román et al. (2021) | Emphasized the positive role of tourism tax cuts in enhancing the sustainability of tourism destinations. |

| Cárdenas-García et al. (2022) | Tourism taxation is one of the tools that can effectively contribute to obtaining resources that favor the development of policies to improve sustainability and the tourist experience in the destination. |

| L. Göktaş and Çetin (2023) | Visitors are willing to pay higher rates of accommodation tax if the tax is earmarked for specific investments in sustainable tourism. |

| Ortega-Rodríguez et al. (2024) | A relationship was found between tourists’ positive attitudes towards green policies and their willingness to pay accommodation taxes. |

| Aspects | Advantages | Disadvantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | A sustainable source of income for countries and regions Influence on the development of regional infrastructure Financing regional promotional activities Help in addressing the negative impacts of tourism development | Decreased regional competitiveness Reduced corporate profitability Decline in tourism demand Short-term economic impacts | Balancing income and regional competitiveness Coordination between stakeholders |

| Environmental | Mitigating the negative impacts of tourism crises Helping to increase tourism resilience Reducing overtourism Protecting the environment | Ineffective when misused | Ensuring that tourism tax revenues are actually spent on sustainable development |

| Social | Increasing social well-being financing local social initiatives | Price sensitivity of certain tourist groups | Achieving fairness in tax design |

| Slovakia | Acc. Tax Revenue | Overnight Stays | Tax Rate (Eur) | Price (Eur) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 21,244,280 | 14,851,364 | 1.43 | 37.9 |

| 2022 | 14,921,711 | 12,719,545 | 1.17 | 34.1 |

| 2021 | 9,934,529 | 8,169,505 | 1.22 | 29.1 |

| 2020 | 11,111,058 | 9,790,597 | 1.13 | 28.3 |

| 2019 | 16,225,300 | 17,703,695 | 0.92 | 29.2 |

| 2018 | 15,011,918 | 15,515,083 | 0.98 | 27.6 |

| 2017 | 14,529,815 | 14,936,762 | 0.97 | 26.6 |

| Accommodation Tax (EUR) | Accommodation Tax (EUR) | Months 1–6 (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 202306 | 2022 | 202206 | 2023 | 2022 | |

| Slovakia | 21,244,280 | 7,710,781 | 14,921,711 | 5,308,208 | 36 | 36 |

| Bratislava | 5,798,099 | 2,022,290 | 3,548,516 | 1,330,343 | 35 | 37 |

| High Tatras | 1,737,117 | 692,945 | 1,131,157 | 370,619 | 40 | 33 |

| Piešťany | 909,961 | 339,157 | 651,194 | 223,189 | 37 | 34 |

| Dudince | 431,466 | 176,469 | 426,679 | 145,849 | 41 | 34 |

| Košice | 1,086,274 | 460,319 | 612,266 | 227,381 | 42 | 37 |

| Demänovská Dolina | 724,184 | 259,883 | 413,994 | 210,695 | 36 | 51 |

| DMO Income in %/Organization Level | Regional | Local | Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subsidies | 29 | 44 | 40 |

| membership fees | 64 | 53 | 56 |

| own activity | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| DMO Income in %/Organization Level | Regional | Local | Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| accommodation tax | 36 | 34 | 35 |

| public finances | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| own activity | 22 | 24 | 23 |

| membership fees | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Creation and Support of Sustainable Products | |

|---|---|

| Subsidies from the Ministry of Transport | 0.4760191 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maráková, V.; Wszendybył-Skulska, E.; Dzúriková, L. Accommodation Tax as a Tool of Financial Management of Destination: Insights from Selected European Countries. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050258

Maráková V, Wszendybył-Skulska E, Dzúriková L. Accommodation Tax as a Tool of Financial Management of Destination: Insights from Selected European Countries. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050258

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaráková, Vanda, Ewa Wszendybył-Skulska, and Lenka Dzúriková. 2025. "Accommodation Tax as a Tool of Financial Management of Destination: Insights from Selected European Countries" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050258

APA StyleMaráková, V., Wszendybył-Skulska, E., & Dzúriková, L. (2025). Accommodation Tax as a Tool of Financial Management of Destination: Insights from Selected European Countries. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050258