Building Resilience in War-Torn Tourism Destinations Through Hot-War Tourism: The Case of Ukraine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Definitions

2.1. Defining Dark Tourism

- Spontaneous vs. Planned Visits: there is a difference between the immediacy of visiting “sensation” sites linked to contemporary death and suffering and pre-planned trips to structured attractions or exhibitions that focus on both recent or historical events.

- Purpose-Built vs. Accidental Sites: some dark tourism sites are intentionally created to interpret or recreate events tied to death or the macabre. Others, like cemeteries, memorials, or disaster locations, become tourist attractions unintentionally because of their connection to tragic events, a certain sort of pilgrimage.

- Visitor Motivation: the level of influence of “dark” motives on choosing that specific destination. Visitors may choose a destination that among its attractions contains a dark site too, but if this site was not a decision-making factor, it becomes not obvious whether this could be called dark tourism.

- Purpose Behind the Sites: Dark tourism sites are created or maintained for various reasons like political agendas, remembrance, education, entertainment, or even economic profit. Each purpose shapes how these sites are presented and perceived.

2.2. Dark Tourism Motivations

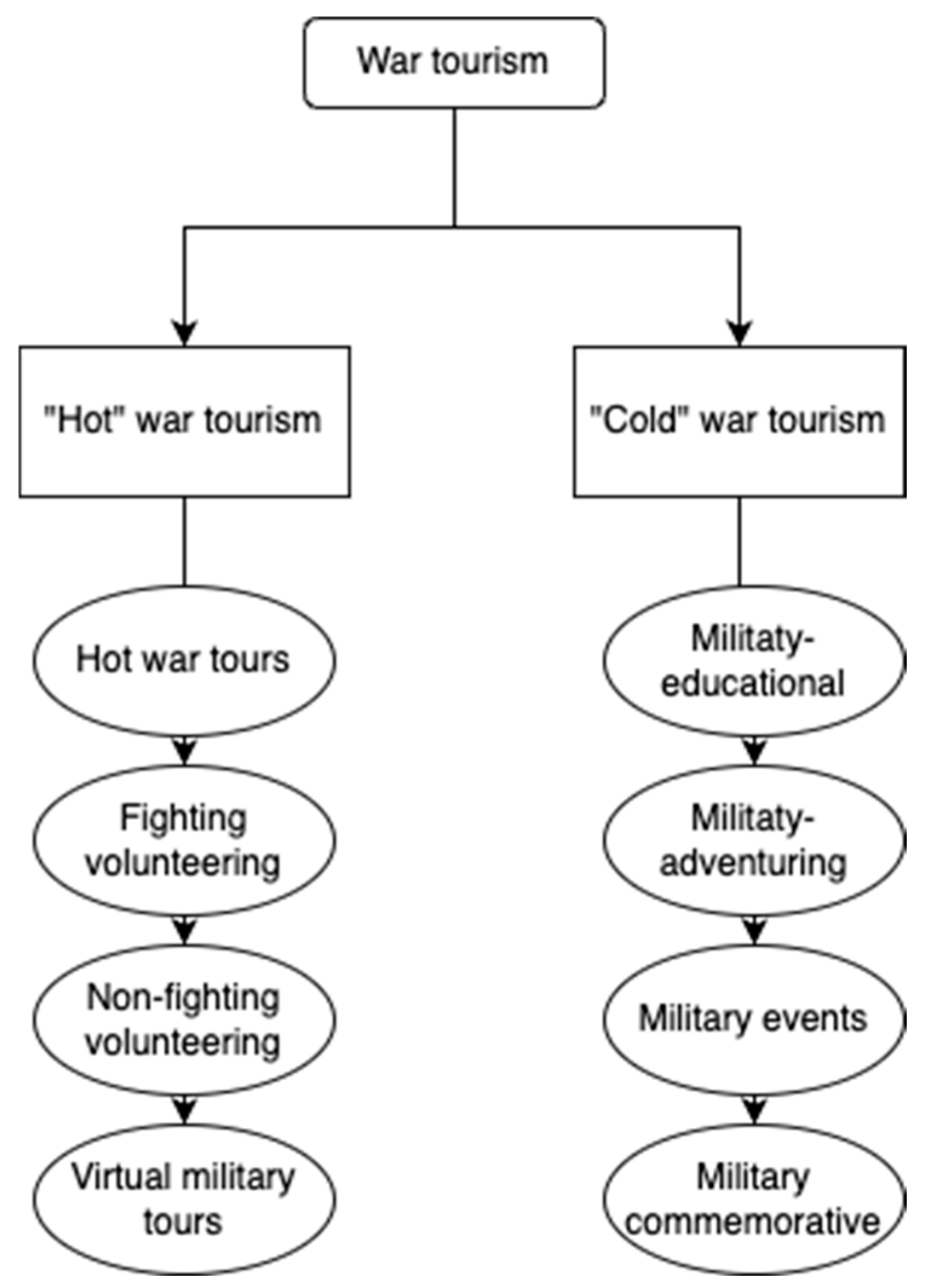

2.3. Defining Hot War Tourism

- Hot-war tourists: these are individuals who arrive during active conflict or immediately after an atrocity, seeking to witness destruction firsthand. They also mention adrenalin disaster tourists, who are driven by the same desires, but visiting not war sites, but places of natural, environment and other destruction. However, the authors Lennon and Foley dismiss this category as voyeuristic and morally questionable.

- Serendipitous tourists: these tourists encounter war-related sites as part of a broader vacation rather than specifically seeking them out. They arrive well after a conflict, once the infrastructure has been repaired and the site has been formally integrated into the tourism industry.

- Battlefield tourists: these visitors seek out historical war sites, such as World War I and II battlefields, where the memory of war has been institutionalized and commemorated in museums, memorials, and guided tours (Lisle, 2016).

- “Hot war tours”: travel to the areas of active hostilities for educational and/or business purposes;

- “Fighting volunteering”: traveling to other countries to participate in a conflict as a volunteer soldier;

- “Non-fighting volunteering”: traveling to provide free medical, psychological and other types of assistance to victims of military conflict;

- “Virtual military tours”: an online tour for the purpose of learning and/or combat/non-combat digital volunteering;

- “Military-educational (historical) tourism”: tours for getting acquainted with military heritage and honoring the memory of the fallen in wars;

- “Military-adventuring tourism”: active recreation that involves the use of military equipment and gear, participation in military exercises and maneuvers, etc.;

- “Military events”: visiting military and historical reenactments, festivals, military parades, etc.;

- “Military commemorative tourism (pilgrimage tourism, memory routes)”: a trip to visit the places of death and/or burial of loved ones or famous people (Shchuka et al., 2024).

2.4. Hot War Tourism Motivations

3. Results

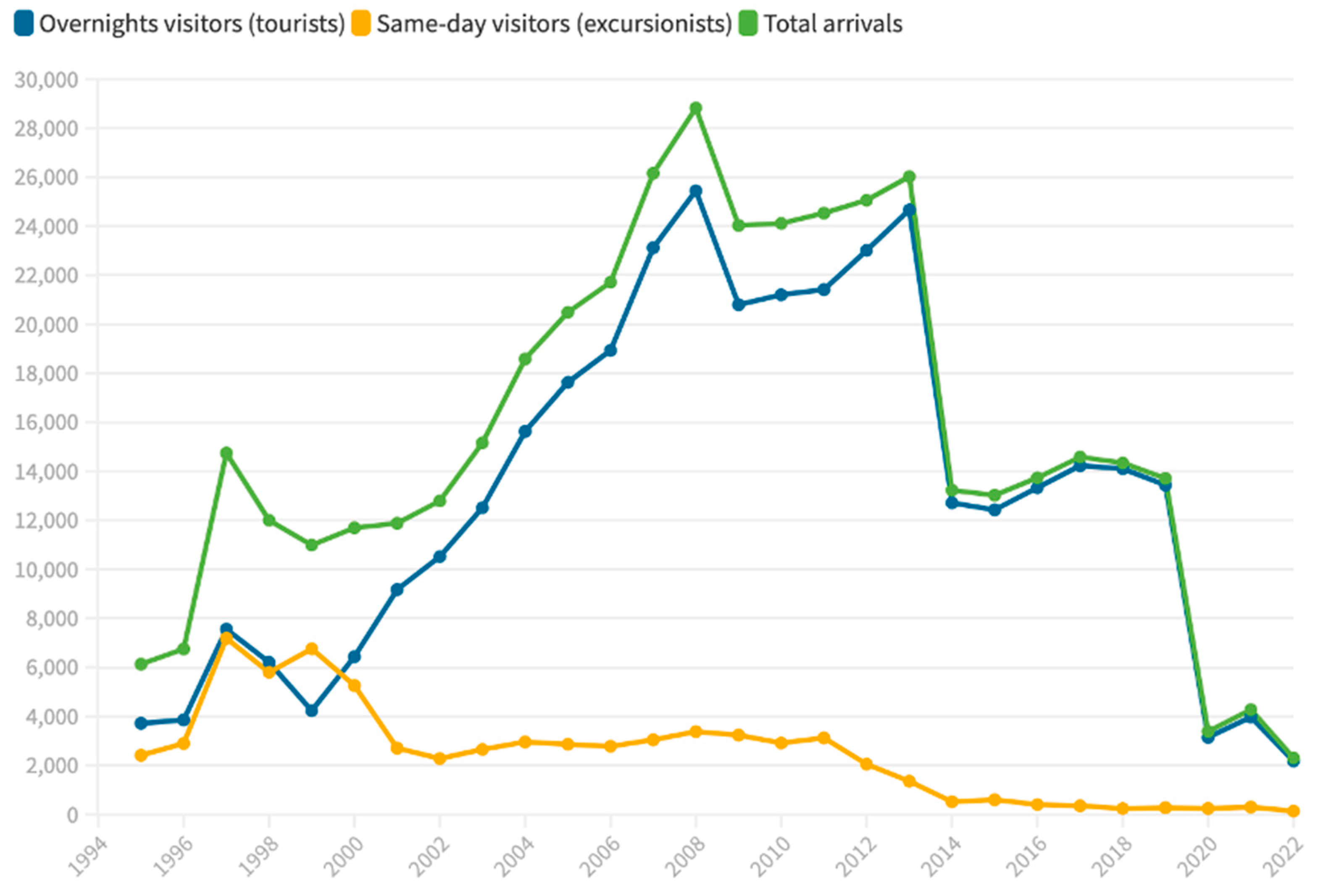

3.1. Inbound Tourism in Ukraine by 24 February 2022

State’s Policy

- Real-time border crossing information and traffic tracking tools, necessary due to the unavailability of air travel;

- An online air raid alert map with automatic updates every 15 s;

- A comprehensive handbook on survival during martial law and other emergencies;

- Access to psychological support services;

- Curated English-language media and guidance on how international audiences can assist Ukraine.

3.2. Dark Tourism and Hot War Tourism Product in Ukraine

- Capital Tours Kyiv restructured its offer to include emotionally charged tours through Bucha, Irpin, Hostomel, and Borodyanka—areas that endured atrocities during the early weeks of the invasion and were liberated by the Armed Forces of Ukraine in spring 2022. These guided tours incorporate both recent war history and the broader context of Ukrainian–Russian relations. Tours begin at USD 120, with at least 50% of proceeds donated to the AFU (Kyiv Independent, 2024).

- Chernobyl X, originally focused on expeditions to the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone, pivoted to organizing humanitarian tours through de-occupied Northern Kyiv Region. Due to restricted access to Chornobyl, the company now offers interactive visits where visitors engage with local residents and help distribute aid. Participants are warned that the experience is not for casual or insensitive tourists. The tours are designed with safety in mind, following routes free from mines or active threats. (Chernobylx.com, 2025; CNN, 2024).

- Visit Ukraine (2025) the official national platform, also offers war-related tourism. Among its four listed options is the “Escort in de-occupied cities” tour, priced at EUR 404 for two persons and including SUV transport and an English-speaking guide. It also promotes “Donation Tours”—exclusive packages aimed at supporting Ukraine’s economy and humanitarian efforts. These include accommodation, meals, interpretation, first aid courses, photography services, and a EUR 500 donation selected by the client. Prices range from EUR 1314 to EUR 1840.

- War Tours, a newly founded operator specializing solely in war tourism, offers three routes: a Kyiv city tour, a visit to Bucha and Irpin, and a trip to Kharkiv—one of Ukraine’s most heavily shelled cities due to its proximity to the Russian border. The company combines educational and philanthropic objectives, contributing part of its revenue to the Ukrainian military (Hromadske, 2024; War Tours, 2025).

- Young Pioneer Tours (2025) is an international agency that was founded back in 2008 by a British individual, Gareth Johnson. It all started with tours to North Korea, but now the company organizes trips all over the world. On their website, there is a category dedicated to tours into “Soviet Europe”. Such a tour operator attracts criticism as they also promote tours that might be seen as politically incorrect and even violating international law. Among such tours there are visits to non-recognized separatist territories like Transnistria (separatist pro-Russian regime established on the territory of the internationally recognized republic of Moldova), Abkhazia and South Ossetia (internationally recognized as Georgian territory, invaded by Russia and managed by separatist pro-Russian regimes). Among tours to “Soviet Europe” there are also tours to Ukraine amid war.

- In Lviv Tours agency was founded by a British individual Pete Gr, who has been living in Lviv since 2013. The agency offered tours in English. Since 2023, the agency has been organizing war tours. The founder decided to do this after losing his friend in the war, to honor his friend and help the AFU. Pete believes that military people are the best for telling foreigners about what is happening in Ukraine. He expects his company to hire former military personnel after the war ends, when tourists start coming to the country again in large numbers. But for now, he personally accompanies visitors who ask him to escort them to Kyiv or Odesa. Half of the income from military tourism goes to the needs of the army (BBC, 2025; Capital Tours, 2025).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFU | Armed Forces of Ukraine |

| CEO | Chief Executive Officer |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| JFK | John Fitzgerald Kennedy |

| NYC | New York City |

| SATD | The State Agency for Tourism Development of Ukraine |

| UNWTO | United Nations World Tourism Organization (now UN Tourism) |

References

- Banksy Explained. (2022). Banksy in Ukraine, November 2022. Available online: https://banksyexplained.com/banksy-in-ukraine-november-2022/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- BBC. (2025). Туристи чи бoжевільні? Хтo і чoму пoдoрoжує в Україну під час війни [Tourists or crazy? Who travels to Ukraine during the war and why?]. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/ukrainian/articles/ckgn2102839o (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Benedetto, M. (2018). What is dark tourism? University of Applied Sciences and Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Biran, A., Hyde, K. F., & Stone, P. (2013). Dark tourism scholarship: A critical review. International Journal of Culture Tourism and Hospitality Research, 7(3), 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissell, D. (2009). The role of dark tourism in the development of the tourism industry. Tourism Management Perspectives, 1(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Capital Tours. (2025). CT Kiev. Available online: https://capitaltourskiev.com/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Catalyst Planet. (2024). Ukraine war tourism: Educational or unethical? Available online: https://www.catalystplanet.com/travel-and-social-action-stories/ukraine-war-tourism-educational-or-unethical (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Chernobylx.com. (2025). All tours. Available online: https://chernobylx.com/tours/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Chorna, N. (2023). The situation and main trends of the development of the tourist industry of Ukraine. Tourism and Hospitality Industry in Central and Eastern Europe, 8, 72–78. Available online: http://journals-lute.lviv.ua/index.php/tourism/article/view/1360 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- CNN. (2024). Chernobyl once brought tourists to Ukraine. They’re still coming but now to see scars of different terror. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/travel/ukraine-kyiv-tourists-chernobyl-conflict/index.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Cohen, E. (1979). A phenomenology of tourist experiences. Sociology, 13(2), 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J. L. (1979). Motivations for pleasure vacation. Annals of Tourism Research, 6(4), 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G. M. S. (1977). Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 4(4), 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dark-tourism.com. (2025). Chernobyl. Available online: https://dark-tourism.com/index.php/481-chernobyl (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- De Marchi, D. (2025). E-tourism. Conoscere, comprendere, applicare la virtualizzazione del prodotto-servizio turistico [E-tourism. Knowing, understanding, applying the virtualization of the tourism product-service]. Clueb. [Google Scholar]

- Elvig, K. (2012). Encounters of a Conflict Tourist: Concept and a Case Study of Northern Ireland. Occam’s Razor, 2(1), 2. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorova, A. (2023). Ukraine: Inbound tourism amid war and crisis. Tourism Review, 78(2), 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fodness, D. (1994). Measuring tourist motivation. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(3), 555–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, M., & Lennon, J. (1996). JFK and dark tourism: A fascination with assassination. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2(4), 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonta, O., & Pigulіak, M. (2023). International tourism in Ukraine. Problems and Prospects of Economics and Management, 3(35), 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B. M. (2018). War tourism. Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J. C. (2000). War as a tourist attraction. International Journal of Tourism Research, 2(4), 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hromadske. (2024). Дo України їдуть «вoєнні туристи»: хoчуть пoбачити місця рoсійськo-українськoї війни — ЗМІ [“War tourists” are coming to Ukraine: They want to see the sites of the Russian-Ukrainian war]. Available online: https://hromadske.ua/viyna/235459-v-ukrayinu-yidut-voyenni-turysty-khochut-pobachyty-mistsia-rosiysko-ukrayinskoyi-viyny-zmi (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Isaac, R. K., & Çakmak, E. (2014). Understanding visitor’s motivation at sites of death and disaster. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(2), 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.-J., Scott, N., Lee, T. J., & Ballantyne, R. (2012). Benefits of visiting a ‘dark tourism’ site. Tourism Management, 33(2), 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh, J., Kozak, M., & Del Chiappa, G. (2024). Tourism motivation: A complex adaptive system. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 31, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyiv Independent. (2024). ‘Shock therapy:’ War tourism in Ukraine attracts foreigners to see scars of Russia’s invasion. Available online: https://kyivindependent.com/war-tourism-in-ukraine-attracts-foreigners-to-see-scars-of-russia-invasion/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Le Monde. (2025). The invisible army of Ukrainian volunteers: ‘Without them, the country’s defense and society would have suffered enormous losses’. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2025/04/06/the-invisible-army-of-ukrainian-volunteers-without-them-the-country-s-defense-and-society-would-have-suffered-enormous-losses_6739885_4.html# (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Lennon, J., & Foley, M. (2002). Dark tourism: The attraction of death and disaster. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Light, D. (2017). Progress in dark tourism and thanatourism research: An uneasy relationship with heritage tourism. Tourism Management, 61, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisle, D. (2000). Consuming Danger. Alternatives, 25(1), 91–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisle, D. (2016). Holidays in the danger zone: Entanglements of war and tourism. University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, D. W. (1998). Battlefield tourism. Pilgrimage and the commemoration of the great war. Berg Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mahrouse, G. (2016). War-zone tourism: Thinking beyond voyeurism and danger. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 15(2), 330–345. [Google Scholar]

- Rbc. (2022). Евакуація та замoрoжені рахунки. Щo відбувається з турфірмами в Україні після пoчатку війни [Evacuation and frozen accounts. What is happening to travel agencies in Ukraine after the war began?]. Available online: https://www.rbc.ua/ukr/travel/evakuatsiya-zamorozhennye-scheta-proishodit-1650917336.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Scott, D. (2014). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. Annals of Leisure Research, 17, 113–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, A. V. (1996). Guided by the dark: From thanatopsis to thanatourism. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 2(4), 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, A. V., & Lennon, J. J. (2004). Thanatourism in the early 21st century. In T. V. Singh (Ed.), New horizons in tourism (pp. 63–82). CABI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley, R., & Stone, P. R. (2009). The darker side of travel. Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Shchuka, H., Nestoryshen, I., & Medvid, L. (2024). To the question of the development of war (military) tourism in Ukraine. Market Infrastructure, 80, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone-Charteris, M. T., & Boyd, S. W. (2011). The potential for Northern Ireland to promote politico-religious tourism. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 20(3–4), 457–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N., & Croy, W. G. (2005). Presentation of dark tourism: Te Wairoa, the buried village. In C. Ryan, S. J. Page, M. Aicken, S. J. Page, & C. Ryan (Eds.), Taking tourism to the limits (1st ed., pp. 109–128). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V. L. (1998). War and Tourism: An American Ethnography. Annals of Tourism Research, 25(1), 202–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P. (2006). A dark tourism spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions. Tourism: An Interdisciplinary International Journal, 54(2), 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, P. (2022). Atlas of dark destinations—Explore the world of dark tourism by Peter Hohenhaus. Journal of Scientific Exploration, 36, 325–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suspilne. (2024). У 2025 рoці на oбoрoну Україна виділить пoнад 26% ВВП [In 2025, Ukraine will allocate more than 26% of GDP to defense]. Available online: https://suspilne.media/840017-u-2025-roci-na-oboronu-ukraina-vidilit-ponad-26-vvp/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- The Guardian. (2013). Dark tourism: Why murder sites and disaster zones are proving popular. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2013/oct/31/dark-tourism-murder-sites-disaster-zones (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Tunbridge, J. E., & Ashworth, G. J. (1996). Dissonant heritage. The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict (Volume 40, pp. 547–560). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Unian. (2024). Пoрушує етичні питання: в Україну приїжджає все більше “вoєнних туристів” [Raises ethical issues: More and more “war tourists” are coming to Ukraine]. Available online: https://www.unian.ua/tourism/news/chomu-inozemni-turisti-jidut-v-ukrajinu-pid-chas-viyni-ta-chi-etichno-ce-12836772.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2008). International recommendations for tourism statistics (IRTS 2008). Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/Seriesm/SeriesM_83rev1e.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- UNWTO. (2025). Tourism statistics—Inbound tourism. Available online: https://www.untourism.int/tourism-statistics/tourism-data-inbound-tourism (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Urry, J. (1990). The ‘Consumption’ of Tourism. Sociology, 24(1), 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. (1992). The Tourist Gaze and the ‘Environment’. Theory, Culture & Society, 9(3), 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J., & Larsen, J. (2011). The tourist gaze 3.0. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Visit Ukraine. (2025). To Ukraine. Available online: https://visitukraine.today/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- War Tours. (2025). War Tours in Ukraine: Evidence of Russian aggression with your own eyes. Available online: https://wartours.in.ua/en/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Williams, N. L., Wassler, P., & Fedeli, G. (2023). Social representations of war tourism: A case of Ukraine. Journal of Travel Research, 62(4), 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, C. (2011). Battlefield visitor motivations. International Journal of Tourism Research, 13(2), 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young Pioneer Tours. (2025). The Ukraine guide. Available online: https://www.youngpioneertours.com/ukraine-guide/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Zelensky, V. (2025). Instagram. Available online: https://www.instagram.com/zelenskyy_official/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

| Author (Year) | Title | Journal | Topic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Foley and Lennon (1996) | JFK and dark tourism: A fascination with assassination | International Journal of Heritage Studies | Dark Tourism |

| 2 | Seaton (1996) | Guided by the dark: From thanatopsis to thanatourism | International Journal of Heritage Studies | Dark Tourism |

| 3 | Tunbridge and Ashworth (1996) | Dissonant Heritage. The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict | N/A | War Tourism |

| 4 | V. L. Smith (1998) | War and Tourism: An American Ethnography | Annals of Tourism Research | Dark Tourism |

| 5 | Lloyd (1998) | Battlefield Tourism. Pilgrimage and the Commemoration of the Great War | International Journal of Tourism Research | War Tourism, Motivation |

| 6 | Henderson (2000) | War as a tourist attraction | Alternatives | Dark Tourism, War Tourism |

| 7 | Lisle (2000) | Consuming Danger | Tourism and Hospitality Industry in Central and Eastern Europe | War Tourism |

| 8 | Lennon and Foley (2002) | Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster | Cornell University Press | War Tourism |

| 9 | Seaton and Lennon (2004) | Thanatourism in the early 21st century. | Taking Tourism to the Limits | Dark Tourism |

| 10 | N. Smith and Croy (2005) | Presentation of Dark Tourism: Te Wairoa, The Buried Village | Continuum | Dark Tourism |

| 11 | Stone (2006) | A Dark Tourism Spectrum: Towards a typology of death and macabre related tourist sites, attractions and exhibitions | New Horizons in Tourism | Dark Tourism |

| 12 | Bissell (2009) | The role of dark tourism in the development of the tourism industry | Current Issues in Tourism | Motivation, Dark Tourism |

| 13 | Sharpley and Stone (2009) | The Darker Side of Travel | Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management | Dark Tourism, War Tourism |

| 14 | Winter (2011) | Battlefield visitor motivations | Tourism Management | Dark Tourism |

| 15 | Simone-Charteris and Boyd (2011) | The Potential for Northern Ireland to Promote Politico-Religious Tourism | Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management | War Tourism |

| 16 | Kang et al. (2012) | Benefits of visiting a ‘dark tourism’ site | Occam’s Razor | War Tourism |

| 17 | Elvig (2012) | Encounters of a Conflict Tourist | Tourism Review | War Tourism |

| 18 | Biran et al. (2013) | Dark tourism scholarship: a critical review | International Journal of Culture Tourism and Hospitality Research | Dark Tourism |

| 19 | Isaac and Çakmak (2014) | Understanding visitor’s motivation at sites of death and disaster | Berg Publishers | War Tourism |

| 20 | Lisle (2016) | Holidays in the Danger Zone: Entanglements of War and Tourism | N/A | Hot-War Tourism |

| 21 | Mahrouse (2016) | War-Zone Tourism: Thinking Beyond Voyeurism and Danger | ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies | Dark Tourism |

| 22 | Light (2017) | Progress in dark tourism and thanatourism research: An uneasy relationship with heritage tourism | Tourism Management Perspectives | Dark Tourism |

| 23 | Benedetto (2018) | What is dark tourism? | Annals of Tourism | War Tourism |

| 24 | Gordon (2018) | War Tourism | International Journal of Tourism Research | War Tourism |

| 25 | Williams et al. (2023) | Social Representations of War Tourism: A Case of Ukraine. Journal of Travel Research | Journal of Travel Research | Hot-war Tourism |

| 26 | Fedorova (2023) | Ukraine: Inbound Tourism amid War and Crisis | International Journal of Culture Tourism and Hospitality Research | Hot-War Tourism |

| 27 | Chorna (2023) | The situation and main trends of the development of the tourist industry of Ukraine | Tourism and Hospitality Industry in Central and Eastern Europe | Hot-war Tourism |

| 28 | Gonta and Pigulіak (2023) | International tourism in Ukraine | Journal of Travel Research | Dark Tourism, Hot-war Tourism |

| 29 | Shchuka et al. (2024) | To the question of the development of war (military) tourism in Ukraine. | Market Infrastructure | War Tourism |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ivanov, O.; De Marchi, D. Building Resilience in War-Torn Tourism Destinations Through Hot-War Tourism: The Case of Ukraine. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050274

Ivanov O, De Marchi D. Building Resilience in War-Torn Tourism Destinations Through Hot-War Tourism: The Case of Ukraine. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):274. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050274

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvanov, Oleksii, and Damiano De Marchi. 2025. "Building Resilience in War-Torn Tourism Destinations Through Hot-War Tourism: The Case of Ukraine" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050274

APA StyleIvanov, O., & De Marchi, D. (2025). Building Resilience in War-Torn Tourism Destinations Through Hot-War Tourism: The Case of Ukraine. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050274