1. Introduction

Photocatalysis is a chemical process where light energy is used to accelerate a specific reaction in the presence of a catalyst. The process typically involves a semiconductor material, such as titanium dioxide (TiO2), which absorbs photons with energy equal to its band gap. This absorption excites an electron from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), thereby creating a highly reactive electron–hole pair (e−/h+). These charges then migrate to the surface of the catalyst, where they can initiate redox reactions with adsorbed molecules. This leads, for example, to the degradation of pollutants, water splitting for hydrogen production, or other chemical transformations.

The term “induced photocatalysis” typically refers to a modified or enhanced form of photocatalysis where the activation of the catalyst is “induced” by a secondary mechanism. This is often performed to extend the catalyst’s activity to a broader range of the electromagnetic spectrum, particularly visible light, which is more abundant than UV light. There are two common ways to induce photocatalysis: (1) dye sensitization where a visible light-absorbing dye is adsorbed onto the surface of a wide-band-gap photocatalyst (e.g., TiO2), subsequently injecting an electron into the CB of the catalyst, and (2) plasmon nanoparticle loading where the addition of noble metal nanoparticles (like gold or silver) to the catalyst enables it to absorb visible light through a phenomenon called Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR), thereby creating “hot electrons” that can be transferred to the photocatalyst to initiate the catalytic reaction.

Induced photocatalysis has been a hot topic in recent years, with the photocatalytic properties of various nanoparticles (NPs) being intensively studied due to their unique physical and chemical properties, especially when applied for efficient wastewater treatment purposes [

1,

2,

3]. As previously mentioned, the mechanism of photocatalytic activity for semiconductor NPs relies on the transition of electrons from the VB to the CB, but their application has been greatly limited by both a large band gap and the low utilization of visible light [

4].

On the other hand, in plasmon-mediated photocatalysis, incident light excites LSPR in metal nanocrystals, leading to the generation of energetic, non-equilibrium “hot electrons” through plasmon decay. These hot electrons have energies greater than the Fermi level of the metal. If the metal nanoparticle is in contact with a semiconductor or a molecular adsorbate, these hot electrons can be injected into the conduction band of the semiconductor or the unoccupied molecular orbitals of the adsorbate. This highly efficient charge transfer process directly drives the chemical reaction. The remaining positively charged nanoparticle (due to the loss of an electron) then acts as a site for hole transfer from the reactant, completing the charge separation. This characteristic makes it a highly promising approach with regard to the controllable selective degradation of organic substances. This process differs from traditional photocatalysis by creating high-energy electrons beyond the thermal equilibrium, which can overcome activation barriers and enable selective chemical transformations, such as the reduction of small molecules, even in the absence of traditional reducing agents [

5,

6,

7]. Thus, the unique ability of plasmonic NPs to efficiently utilize the visible and near-infrared light spectrum to generate hot electrons can be utilized to generate and directly inject hot electrons to drive the catalytic reaction, overcome the bandgap limitations of traditional semiconductors, and offer a more efficient and broadband approach to photocatalysis.

Designing well-defined plasmonic nanostructures is essential for manipulating surface plasmons and enhancing the efficiency of hot-electron-based processes. Therefore, it is necessary to provide the tools required to determine the optimal conditions for effective photocatalysis. One way of achieving this goal is to determine the most effective frequency range of electromagnetic radiation at which photocatalytic processes occur. As mentioned above, in the case of organic compounds, hot electrons are injected into the unoccupied molecular orbitals of the molecule, causing its reduction. Methylene blue was selected as the organic compound for this study; it acts as a redox indicator because it changes color depending on its oxidation state. In its oxidized form, it is blue, while in its reduced form, it is colorless. This property allows it to visually signal the presence or absence of oxidizing or reducing agents in a chemical reaction [

8]. Consequently, the electronic setup was designed to determine the effective light frequency range in photocatalytic activity with plasmonic NPs. Using silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) may be better than gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) due to their lower cost and stronger LSPR effects in the visible and UV regions, which can lead to higher photocatalytic activity. AgNPs exhibit better light absorption in the UV-A and near-UV spectrum, which is beneficial for many photocatalytic reactions. However, AgNPs also have some drawbacks compared to AuNPs—they are less stable and susceptible to oxidation and aggregation, which can, in turn, lead to the loss of their unique optical and catalytic properties over time. Nevertheless, for pure photocatalytic studies, AgNPs may offer higher efficiency.

2. Experimental Setup

AgNPs (dispersion < 100 nm, 10 wt.% in ethylene glycol) and Methylene Blue (>98% purity) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Burlington, MA, USA). Triply distilled water was used in all measurements.

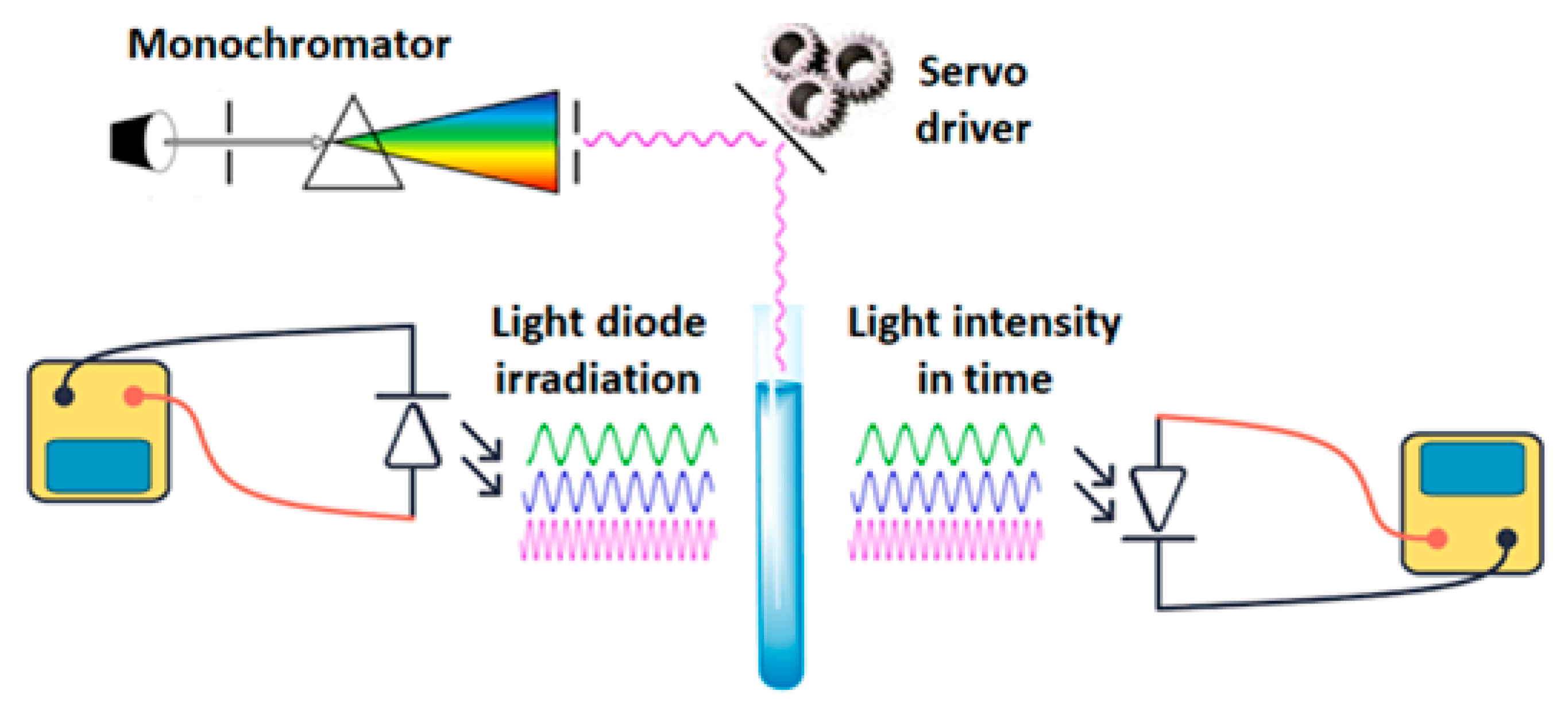

To determine the effective light wavelength range in photocatalytic activity with AgNPs, an experimental setup with software-controlled wavelength scanning was developed and implemented. The hardware was built around the Atmega2560 microcontroller, which ensures the coordination of all electronic setup components. These components include the light sources, the wavelength selection unit, the irradiation time control unit, and the registration unit (

Figure 1).

The setup installation configuration includes the following key elements:

An incandescent lamp generating light across the visible spectrum serves as the primary electromagnetic radiation source. The light irradiation passes through an optical collimation unit before entering the monochromator. For monitoring the degradation process (indicated by absorption) within the wavelength range of 610–660 nm, a separate appropriate LED is used.

A prism monochromator is used to separate a narrow range of wavelengths. The mechanism allows the prism’s rotation angle to be changed programmatically, thereby ensuring the selection of the desired wavelength with a step of less than 5 nm.

Aqueous solution of methylene blue (MB) and Ag NPs was prepared by mixing 10 μL stock Sigma AgNPs solution with 990 μL H2O and 10 μL 5% mass solution of MB with 990 μL H2O, accordingly. The reaction mixture (containing the aqueous solution of MB and AgNPs) was placed in a glass vial, which was fixed on the optical axis, perpendicular to the direction of light radiation.

A silicon photodiode (an analog light sensor) was placed behind the vial to measure the light intensity passing through the solution. The change in transmittance was subsequently used as a marker of photocatalytic activity.

The embedded software of the Atmega2560 microcontroller was designed to provide sequential scanning of a given wavelength range, exposure time control, signal recording from the photodetector, and data transmission for subsequent analysis.

All components were powered by a stabilized power supply equipped with appropriate protection. Current stabilization for the LED was specifically implemented to ensure radiation stability throughout the entire series of measurements.

3. Results and Discussion

Shown in

Figure 2 is the size distribution of Ag NPs and the absorption spectra of Ag NP with the MB solution.

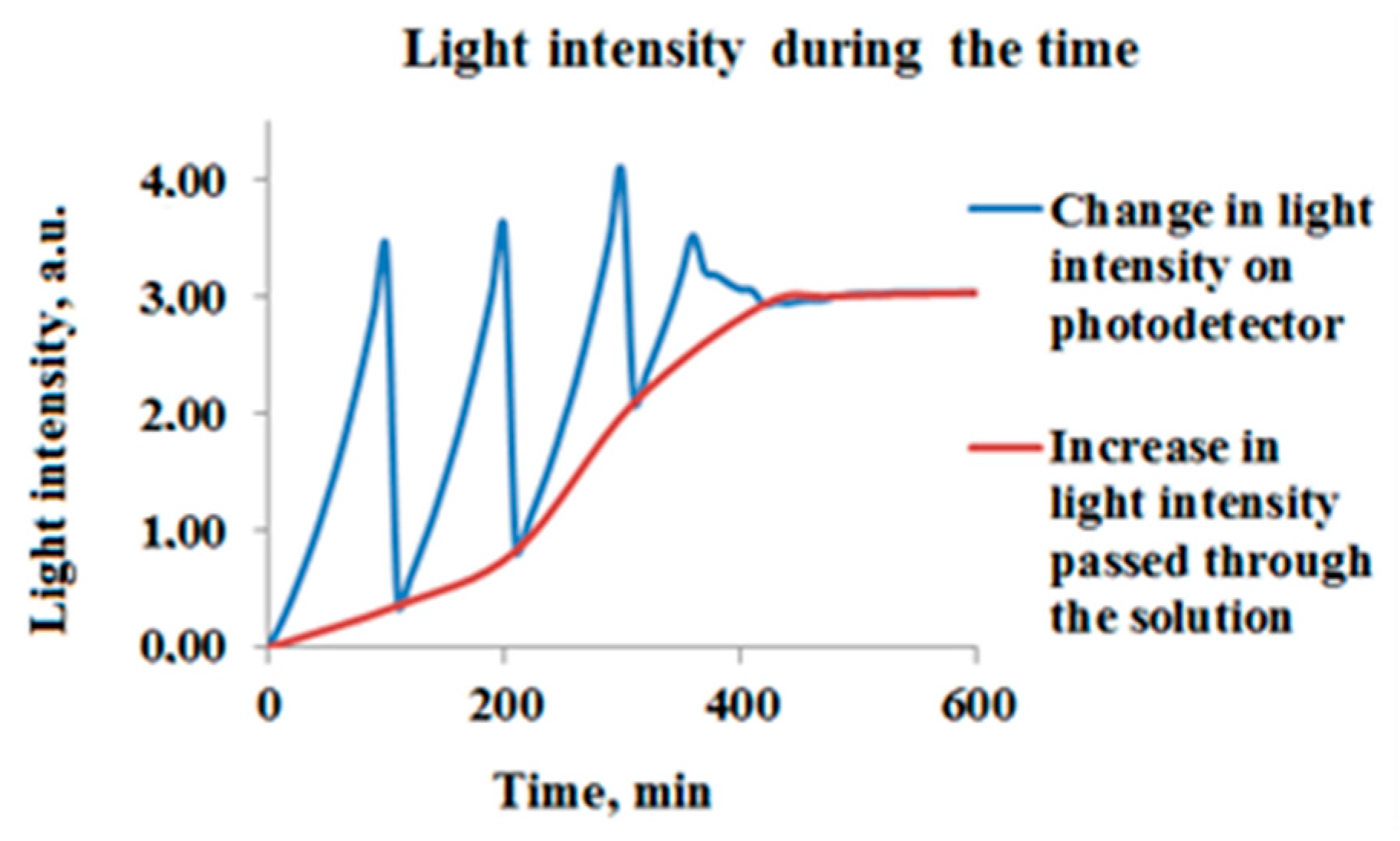

Light irradiation from the incandescent lamp passes through an optical collimation unit before entering the monochromator, where a narrow range of desired wavelengths is separated. The selected light wavelength then passes through the transparent quartz vial containing the AgNPs-MB mixture and impinges upon the photodetector, which measures the light intensity transmitted through the solution. MB acts as a redox indicator; it is blue in its oxidized form and colorless in its reduced form. This property allows for the visualization of the presence or absence of oxidizing or reducing agents in a reaction mixture [

8]. As a result of hot electron generation—which occurs when the AgNPs are irradiated with light close to their plasmonic frequency due to the LSPR—the blue dye solution becomes colorless. This discoloration or degradation of MB molecules leads to a corresponding increase in light intensity measured by the detector (

Figure 3) [

9,

10].

Conversely, the light irradiation at a wavelength significantly detuned from the Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) frequency does not induce the photocatalytic transformation of MB.

4. Conclusions

Photocatalysis is a chemical process where light energy is used to accelerate a specific reaction in the presence of a catalyst. The mechanism of photocatalytic activity for semiconductor nanoparticles (NPs) relies on the transition of electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). However, this application has been greatly limited by the large band gap and low utilization of visible light. Induced photocatalysis, specifically plasmon-mediated photocatalysis, occurs when incident light excites the Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) in metal nanocrystals, leading to the generation of energetic, non-equilibrium “hot electrons”. This process differs significantly from traditional photocatalysis by creating high-energy electrons beyond thermal equilibrium, which can overcome activation barriers and enable selective chemical transformations. The unique ability of plasmonic NPs to efficiently utilize the visible and near-infrared light spectrum to generate hot electrons overcomes the bandgap limitations of traditional semiconductors, thereby offering a more efficient and broadband approach to photocatalysis. To determine the optimal condition for effective photocatalysis, an electronic setup was designed to identify the effective electromagnetic radiation range. The proposed setup architecture can be readily adapted to determine the photocatalytic activity range for both pure semiconductor NPs and those combined with plasmonic metals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M. and S.K.; methodology, E.M.; software, S.K.; validation, P.B.; formal analysis, B.S.; investigation, S.K.; resources, B.S.; data curation, B.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M. and S.K.; writing—review and editing, P.B.; visualization, S.K.; supervision, B.S.; project administration, B.S.; funding acquisition, B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ghamarpoor, R.; Fallah, A.; Jamshidi, M. A Review of Synthesis Methods, Modifications, and Mechanisms of ZnO/TiO2-Based Photocatalysts for Photodegradation of Contaminants. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 25457–25492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-E.; Kim, M.-K.; Danish, M.; Jo, W.-K. State-of-the-art review on photocatalysis for efficient wastewater treatment: Attractive approach in photocatalyst design and parameters affecting the photocatalytic degradation. Catal. Commun. 2023, 183, 106764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, T.; Liao, A.; Xu, Y.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C. Recent advances and mechanism of plasmonic metal–semiconductor photocatalysis. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 17041–17050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanif, M.A.; Lee, I.; Akter, J.; Islam, M.A.; Zahid, A.A.S.M.; Sapkota, K.P.; Hahn, J.R. Enhanced Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Performance of ZnO Nanoparticles Prepared by an Efficient Thermolysis Method. Catalysts 2019, 9, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Nguyen, S.C.; Ye, R.; Ye, B.; Weller, H.; Somorjai, G.A.; Alivisatos, A.P.; Toste, F.D. Paul Alivisatos, Dean Toste, A Comparison of Photocatalytic Activities of Gold Nanoparticles Following Plasmonic and Interband Excitation and a Strategy for Harnessing Interband Hot Carriers for Solution Phase Photocatalysis. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Ren, L.; Wang, D.; Ye, J. Metal nanoparticles induced photocatalysis. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017, 4, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linic, S.; Christopher, P.; Ingram, D.B. Plasmonic-metal nanostructures as light harvesters for solar fuels and chemicals. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Zekker, I.; Zhang, B.; Hendi, A.H.; Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, S.; Zada, N.; Ahmad, H.; Shah, L.A. Review on Methylene Blue: Its Properties, Uses, Toxicity and Photodegradation. Water 2022, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, K. Fast Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Dye Using a Low-power Diode Laser. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 283, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáenz-Trevizo, A.; Pizá-Ruiz, P.; Chávez-Flores, D.; Ogaz-Parada, J.; Amézaga-Madrid, P.; Vega-Ríos, A.; Miki-Yoshida, M. On the Discoloration of Methylene Blue by Visible Light. J. Fluoresc. 2019, 29, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).