Abstract

Portuguese ceramic tile (azulejo) production has evolved significantly since its beginnings in the 16th century. While historic tiles reflect well-established traditional techniques and styles, modern and contemporary works began to explore new aesthetic and material possibilities, introducing textures, surface effects, and experimental approaches that challenge conventional conservation methods. This study examines a contemporary Portuguese tile panel dated from 1987, featuring decorative effect glazes with crater and crazing textures, which were characterized and reproduced. Analytical techniques, including optical microscopy, micro-X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, and Raman spectroscopy in microscopic mode, were employed to characterize material composition and formation mechanisms. Results showed that the crater-effect glazes were achieved with a silica-rich glaze recipe with MnO2 and ZrO2. The crazing effect developed in regions where unmelted crystalline silica induced internal stresses within a lead-silicate glaze, contributing to localized degradation. Experimental reproductions of the glazes, guided by analytical data, were conducted to better understand their formation and inform conservation strategies. The results provide essential insights for the technical assessment, documentation, and preservation of contemporary ceramic artworks featuring decorative effect glazes and contribute to the broader field of cultural heritage conservation.

1. Introduction

Since the 16th century, ceramic tile production in Portugal has undergone profound transformations. Whereas traditional tiles embody established methods and stylistic conventions, modern and contemporary works experiment with novel materials, textures, and surface treatments, embracing innovative approaches that often pose challenges for conventional conservation practices. Glazes exhibiting what were previously considered technical flaws—crazing, crawling, shivering, pinholes, and blisters [1,2,3]—are now sought after for their expressive qualities, as documented in recent literature [4,5].

However, these novel tactile results introduced by modern and contemporary ceramicists can pose specific conservation challenges. Irregular glaze textures with inclusions, craters, or crazing, are more susceptible to degradation phenomena such as glaze detachment and biological colonization [1]. Addressing such challenges requires a conservation assessment grounded in material knowledge, for which recent analytical examinations and technical art history studies have been making increasingly significant contributions [6,7]. Furthermore, the study of artists’ materials and techniques through documentation and reproduction is especially relevant to the conservation and restoration of azulejos, in which historical reproductions of tiles or large tile fragments are used to fill significant gaps in historical panels [8,9,10,11].

Despite the expressive diversity and emerging conservation issues, academic studies focusing on the material and technical characterization of modern and contemporary tile production remain limited, with a predominant emphasis on traditional tin glaze techniques, also known as maiolica. More recently, microscopy and spectroscopic methods have been applied to investigate glaze composition [8,9,12,13]. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyses in early to mid-20th-century Portuguese tile panels generally revealed silicon-rich glazes with lead and potassium as main fluxes, typically opacified with tin [8,9,13]. Mortari et al. [12] identified lead-silicate glazes in tiles from 1959–1972, where ZrO2 replaced tin as an opacifier. Several coloring agents were also detected by µRaman and µXRF, including Naples yellow, lead–tin yellow type II, Pb–Sn–Sb triple oxide, cobalt blue, chromium oxide, malayite sphene, and manganese-based purples.

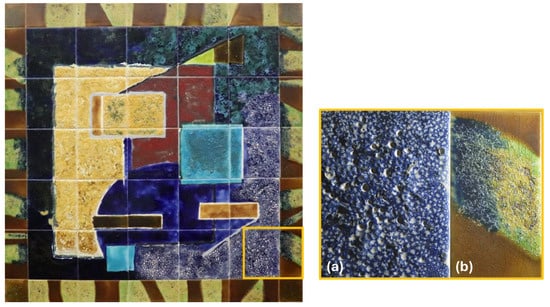

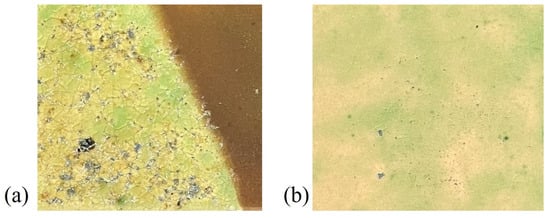

To the best of our knowledge, decorative effect glazes—such as crater glazes and crazing—used in tile art have not yet been systematically studied from either a material or technical perspective. To initiate this line of research, we analyzed a tile panel from the collection of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Lisbon (FBAUL), created in 1987. This panel exhibits effect glazes, some of which pose specific conservation challenges—particularly crazing associated with the detachment of vitreous layers, alongside stable crater-effect glazes (Figure 1a,b). Crazing, historically perceived as a glaze defect, occurs when the glaze expands more than the underlying clay body during cooling. This typically results from an insufficient amount of silica and/or alumina in the glaze to counteract the high thermal expansion of fluxes such as potassium oxide [4]. Nowadays, however, crazing is often intentionally used by contemporary artists for aesthetic purposes. Crater glazes, as described by Bloomfield [4], form when materials in the glaze release gases during firing: water at around 500 °C, carbon dioxide from carbonates at 600–800 °C, and gases from the breakdown of silicon carbide and metal oxides (Mn, Fe, Cu) above 1000 °C. These gases create bubbles and craters as the glaze melts and bonds with the clay body.

Figure 1.

FBAUL/CER/AzC/182, Ana Maria Alves Casimiro Nunes (1987), tile panel (90.4 cm × 90.4 cm) (left) and detail of tile panel under racking light (right). Crater glaze (a). Crazing glaze (b). Rafaela Schenkel©.

To deepen the understanding of the artistic processes employed in contemporary tile production and contribute to the conservation assessment of this and similar panels, the present study aims to gather detailed information on the materials and techniques used. For this purpose, a multi-analytical approach was employed, combining optical microscopy, XRF spectrometry, and Raman spectroscopy, alongside experimental reproductions of the original effect glazes to further document the decorative techniques.

Recent work shows that XRF can provide reliable semi-quantitative results for glaze and enamel investigations when appropriate calibration, reference materials, and measurement strategies are used [12,14]. Comparative studies have validated p-XRF against destructive analytical methods such as SEM-EDS or PIXE, confirming its suitability for major-element evaluation and for relative comparison of glaze compositions [15,16]. Additional research highlights the influence of surface geometry and emphasizes the need to select flat or gently sloped areas to reduce topography-related artefacts in elemental mapping [17,18]. Together, these studies indicate that semi-quantitative XRF is sufficiently reliable for comparative purposes, particularly when assessing technological similarities or differences between original samples and replicas.

Through this research, we aim to advance understanding, documentation, and preservation of tile heritage featuring decorative effect glazes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Tile Panel

The tile panel in this study (Figure 1) belongs to the alumni collection of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Lisbon (FBAUL), catalogued under inventory number FBAUL/CER/AzC/182. It was created in 1987 by Ana Maria Alves Casimiro Nunes, a former student. The panel, measuring 90.4 cm × 90.4 cm, features abstract geometric compositions in shades of blue, brown, green, and yellow. The glazes of the frame were applied directly onto the bisque-fired ceramic body. This is evident in areas where the glaze is semi-transparent, revealing the yellowish color of the ceramic body (Figure 1b). It is referred to in the literature as possessing a high degree of artistic quality and remains on display within the premises of the faculty [19].

The glazes applied to the panel reflect the artist’s expressive intent, characterized by tactile surfaces created through deliberate variations in the thickness and depth of the vitreous layers [20]. Among the material and chromatic effects, one is observed in a blue-toned section, where the formation of alveoli—caused by the release of air during the firing process—results in the so-called “crater effect”. The other reveals structural instability, as evidenced by an extensive network of crazing that leads to partial detachment of the glaze. In addition, there is no record of any past conservation action.

The tiles from the panel, preserved individually in a box in the ceramic painting storage area, were brought to the laboratory for observation and analysis using microscopy techniques. The examinations were carried out directly on the tile surfaces.

2.2. Stereo Microscope Observations

The surface morphology of the glazes was observed using a M205 C stereomicroscope from Leica, Vila Nova de Famalicão, Portugal, featuring magnifications of 10 to 160×, a resolution of 1050 lp/mm, and an LED lighting system. The images were taken with a Leica IC80HD camera and processed using the Leica Application 4.0 program. The equipment belongs to the Physics Department at NOVA FCT (Caparica, Portugal).

2.3. Micro-X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (μXRF) Analysis

The analytical procedure used for the µXRF characterization of the effect glazes included acquisition of elemental distribution maps and quantitative analysis of selected areas. This procedure made use of a μXRF Tornado M4 from Bruker, Berlin, Germany, equipped with a Rh target X-ray tube, coupled to a XFlash® SDD detector, with a 30 mm2 sensitive area and an energy resolution <145 eV at 5.9 keV. Outside the X-ray tube, a polycapillary lens is located, which accounts for a spot size of 25 μm or less at the sample. The X-ray tube operated at 50 kV and 300 μA for 180 s. Spectra acquisition was performed under a pressure of 20 mbar. The XRF measurements were performed on crater-effect zones specifically selected for being large and/or shallow, thereby minimizing surface irregularities. By focusing on the relatively flat regions of the craters, we reduced artefacts related to topography. This selection helps ensure that variations in surface geometry have minimal impact on both the quantitative results and the elemental maps. Quantitative evaluation of the glazes was carried out using the internal software MQuant version 1.2.0.2687, which is based on the fundamental parameter method and enables standardless quantification of sample oxides, considering those typically present in glaze matrices. Because this study focuses on comparative trends, semi-quantitative concentrations were preferred over absolute values. For glaze characterization, ten measurement points were analyzed to reduce standard deviation, increase representativeness, and compensate for the micro-scale compositional heterogeneity typical of glazed surfaces. The equipment belongs to the Physics Department at NOVA FCT (Caparica, Portugal).

2.4. Micro-Raman Spectroscopy (μRaman) Analysis

The structural composition was investigated using μRaman spectroscopy with an XploRA confocal spectrometer from Horiba-Jobin Yvon GmbH, equipped with an air-cooled iDus CCD detector, Grabels, France. Spectra were obtained using a 785 nm laser wavelength, a 100× magnification objective, a 300 μm pinhole, a 200 μm entrance slit, and a 1200 lines/mm diffraction grating. The laser power at the sample was kept at 0.05 mW to avoid structural and compositional crystallographic changes. Accumulation times per spectrum were set to 100 s. Spectra deconvolution was performed using LabSpec (V5.78) software. The equipment belongs to the Physics Department at NOVA FCT (Caparica, Portugal).

2.5. Experimental Reproductions

Experimental reproductions of a blue crater-effect glaze (Figure 1a) and a transparent, light green, crazing-effect glaze (Figure 1b) were carried out at the ceramics workshop of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Lisbon (FBAUL), based on the results obtained by optical microscopy, μXRF and μRaman and the expertise of P. Fortuna as a ceramic painter and professor of the FBAUL.

Both reproductions utilized bisque-fired (biscuit) industrial ceramic tiles, equivalent to those used in the original tile panel (Figure 2).

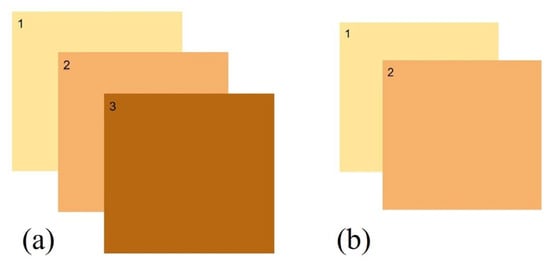

Figure 2.

Scheme representing the different layers involved in the experimental reproduction of the crater effect glaze (a) 1. Biscuit, 2. CE VBC 32 (FERRO©) enriched with MnO2, 3. Layer of CE VTR 29 with CoO; and of the crazing effect glaze (b) 1. Biscuit, 2. CE VTR 29 (FERRO) with CuO sprinkled with tiny pieces of crystalline silicon.

All glazes were applied as an aqueous suspension prepared from finely ground glaze powder to ensure uniform distribution over the surface.

For the reproduction of the blue glaze featuring white craters, an initial layer composed of 25 g of industrial opaque glaze CE VBC 32 by FERRO© (FERRO© product information (adapted), see the table below) enriched with 0.25 g of manganese oxide (MnO2) was applied to the biscuit surface. Subsequently, a second layer consisting of 25 g of CE VTR 29 transparent lead-based glaze by FERRO© supplemented with 0.5 g of cobalt oxide (CoO), was also applied.

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | B2O3 | Na2O | K2O | CaO | MgO | ZrO2 | ZnO | PbO | |

| CE VBC 32 | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | + | +++ | + | + |

| CE VTR 29 | +++ | ++ | + | + | +++ |

To reproduce the crazing effect glaze, 25 g of the CE VTR 29 FERRO© was applied to the bisque tile, supplemented with 0.125 g of copper oxide (CuO). The surface was then sprinkled with tiny pieces of crystalline silicon.

Both tiles were fired at the ceramics workshop in the Faculty of Fine Arts in Lisbon, using an electric kiln under the following conditions: oxidizing atmosphere, heating ramp of 100 °C/hour, dwell of 20 min at 1020 °C, and natural cooling with the kiln closed.

3. Results and Discussion

Results are presented by glaze effect, considering first crater glazes and then crazing.

3.1. Crater Glazes

The characterization of both the original and reproduction crater-effect glazes was based on elemental distribution mapping and quantitative analysis of selected areas using µXRF spectrometry.

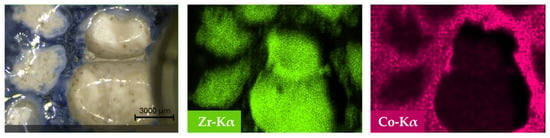

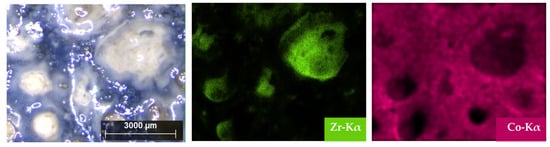

The observation of the maps obtained from the original glaze revealed a distinct elemental distribution on its surface (Figure 3). Localized concentrations of elements such as zirconium (Zr) were identified within the white cratered regions. In contrast, cobalt (Co) was predominantly distributed around the periphery of the craters. These results suggest that the final glaze was obtained by the superposition of two overlapping layers: a Zr-opacified glaze, responsible for the white background, covered by a Co-containing glaze, which produces the blue coloration observed around the craters.

Figure 3.

Micrograph of the blue cratered glaze area and respective elemental distribution maps of zirconium (Zr-Kα) and cobalt (Co-Kα) obtained by µXRF from the original glaze.

To gain further insight into the material composition of the white Zr-opacified glaze layer —responsible for crater formation—semi-quantitative analysis of the white cratered regions was carried out using µXRF. The results presented in Table 1 indicate a high-silica matrix (66 wt.% SiO2) with Na2O (7 wt.%), PbO (6 wt.%), and CaO (4 wt.%) as main fluxes. Alumina is also present in a significant amount (8 wt.% Al2O3), enhancing melt viscosity and contributing to the structural integrity of the glaze during firing [2]. The incorporation of 5 wt.% ZrO2 into the glaze composition serves a dual role as both a white opacifier and a structural stabilizer within the glaze matrix. As an opacifier, zirconium dioxide gained importance during the 20th century as a more economical alternative to traditional tin dioxide (SnO2), which had been used for many centuries to produce white glazes [3,7,20]. Zirconium-opacified glazes have been identified in Portuguese azulejos from the second half of the 20th century and is associated with industrial productions [20]. In addition, ZrO2 is also known to reduce thermal expansion and improve mechanical rigidity [21], properties that may contribute to the stabilization of gas-formed voids during firing. Simultaneously, the addition of 0.5 wt.% MnO2 introduces a controlled gas-releasing mechanism through its thermal decomposition into MnO and O2, promoting the formation of surface craters characteristic of crater-effect glazes [4]. The presence of ZrO2 appears to support the retention of these surface features by inhibiting the collapse of the resulting voids, thereby enhancing both the textural definition and visual complexity of the glaze. To the best of our knowledge, the use of ZrO2 in relation to crater-effect glazes has not been previously reported in the literature.

Table 1.

Mean chemical composition (wt.%) and standard deviation obtained 1 from 10 analysis points of the original and reproduction white glazes, determined by XRF analysis.

The integration of elemental distribution mapping (Figure 3) and the quantitative analysis of the white, cratered glaze (Table 1) provided information on the artistic production, including the identification of the chemical composition necessary to reproduce the original material.

The reproduction of the original glaze presented in Figure 4 demonstrates visual and textural characteristics that closely match those of the original crater effect glaze observed on the historical panel.

Figure 4.

Photograph details of the original (a) and the reproduction glaze (b).

The similarity of the elemental distribution maps obtained via µXRF for the reproduction glaze confirms the intended use of two overlapping glaze layers, consisting of a blue glaze applied over a white one (Figure 5). Moreover, the chemical composition determined the white glaze closely parallels that of the original (Table 1), thereby validating the effectiveness of the reproduction protocol in reproducing both material selection and technological procedures.

Figure 5.

Micrograph of the reproduction glaze and respective elemental distribution maps of zirconium (Zr-Kα) and cobalt (Co-Kα) obtained by µXRF.

3.2. Crazing Glazes

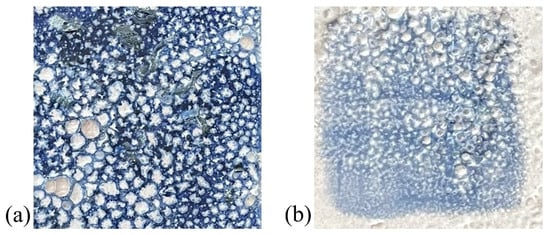

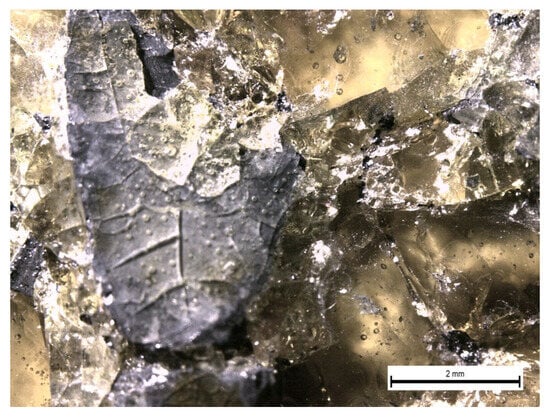

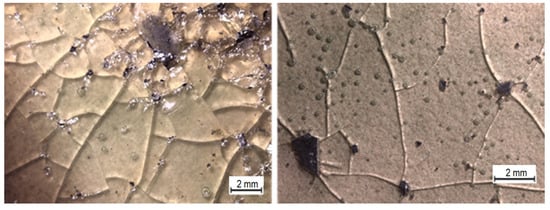

The first results were obtained through stereomicroscopic observations of the crazed areas on the frame of the original tile panel followed by elemental distribution mapping using µXRF spectrometry. These observations revealed that detachments predominantly occur over dark grains that did not melt within the transparent glaze during the firing process, as shown in Figure 6. These regions also exhibit significant tension, as evidenced by the high density of microcracks.

Figure 6.

Micrograph of one of the glazes on the frame of the tile panel, showing dark grains embedded beneath the transparent glaze, with visible crazing and partial detachment.

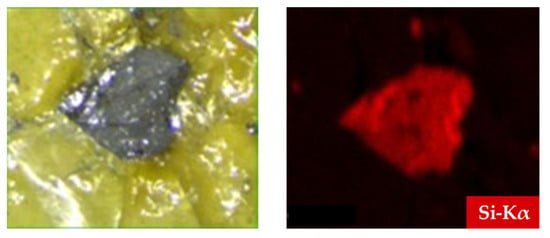

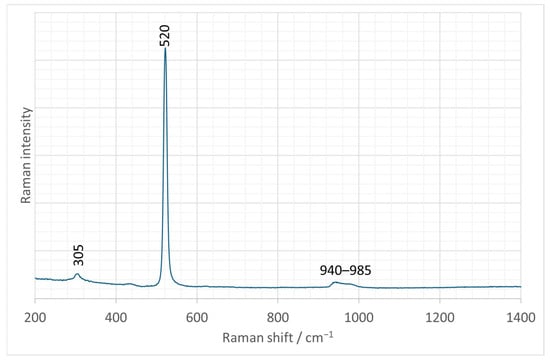

The elemental distribution obtained by µXRF over the grains shows silicon (Si) concentrated in these areas, indicating that the grains contain this element in their composition (Figure 7). Raman spectroscopy analysis further revealed characteristic peaks at 305 cm−1 and 520 cm−1, along with a broad band between 940 and 985 cm−1, all indicative of the crystalline structure of silicon (Figure 8) [22]. Given that the melting point of crystalline silicon (~1400 °C) is significantly higher than the firing temperature of the glaze (~900 °C) [4], these silicon grains exhibit minimal interaction with the vitreous matrix and its network modifiers. As a result, they act as stress concentrators within the glaze, leading to cracking and structural weakening of the overlying glaze layer. In fact, according to the results obtained for the dark grains, all crazing effects seem to have originated in silicon particles.

Figure 7.

Micrograph of a crazing glaze surface showing a dark grain embedded beneath the transparent layer and respective elemental distribution map of silicon (Si-Kα) obtained by µXRF.

Figure 8.

Raman spectrum obtained at a dark grain, revealing the characteristic peaks and bands from crystalline silicon [23].

To further investigate the material composition, semi-quantitative analysis of the semi-transparent glaze with greenish hues was performed using µXRF. The results presented in Table 2 reveal the use of a lead–silica glaze containing approximately 37 wt.% PbO and 53 wt.% SiO2 with a considerable amount of Al2O3 (8.0 wt.%). The presence of CuO (0.47 wt.%) suggests intentional addition for coloration purposes, specifically to produce greenish hues in a silica-lead glaze matrix [2]. The obtained composition does not correspond to the explanation commonly reported in the literature for the occurrence of crazing, which attributes it to a deficiency of silica and/or alumina needed to counterbalance the high thermal expansion of fluxes such as potassium oxide. Instead, these findings support the assumption that Si crystals were responsible for the crazing effect observed in the glazes. As for the artistic intention, it remains uncertain; the crazing could have been deliberately embraced as part of the visual outcome, but it could also have resulted from an unintended consequence of the chosen materials.

Table 2.

Mean chemical composition (wt.%) and standard deviation obtained 1 from 10 analysis points of the original and reproduction semi-transparent glazes with greenish hues, determined by XRF analysis.

The mapping of the elemental distribution (Figure 7) and the elemental composition determined by µXRF of the original crazed glaze, together with the structural composition of the chemical compounds determined by µRaman spectroscopy (Table 2 and Figure 8), enabled the identification of the material composition required to reproduce the original glaze. Original glaze and reproduction are shown in Figure 9 for direct comparison.

Figure 9.

Photographs of the original glaze (a) and the reproduction (b).

Comparative micrographs presented in Figure 10 reveal similarities between the original glaze and the reproductions. A lack of interaction is observed between the vitreous matrix and the embedded dark particles, which are identified as crystalline silicon. This incompatibility leads to the development of crazing and microcracks within the glaze, which is attributed to the stress generated during firing and cooling. Additionally, the chemical composition of the reproduction glaze closely matches the chemical composition of the original one (Table 2).

Figure 10.

Comparative micrographs showing the original glaze texture (left) and reproduction (right).

4. Conclusions

This study offers the first analytical insights into the material composition and structural characteristics of a contemporary tile panel featuring decorative effect glazes such as crater glaze and crazing. The identification of deterioration mechanisms—particularly internal stresses induced by unmelted crystalline silicon in lead-silicate glazes—highlights key factors affecting glaze stability. Simultaneously, the documentation and reproduction of crater-effect glazes based on analytical data deepen the understanding of their formation processes. These findings provide a foundation for developing informed conservation strategies tailored to the specific challenges posed by modern ceramic surfaces. Beyond supporting the preservation of the studied panel, this work establishes a methodological framework for future research on decorative glazes in modern and contemporary ceramic art, contributing to the long-term safeguarding of cultural heritage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., R.S. and P.F.; methodology, M.M. and P.F.; validation, M.M., P.F. and S.C.; formal analysis, M.M., P.F. and S.C.; investigation, M.M. and R.S.; resources, M.M. and P.F.; data curation, M.M. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M., R.S. and S.C.; supervision, M.M. and P.F.; project administration, M.M. and P.F.; funding acquisition, M.M. and S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), contracts DOI:10.54499/CEECINST/00102/2018/CP1567/CT0038 through (CEEC INST 2018) and projects 2023.11076.TENURE.045; DOI: 10.54499/UID/00729/2025 and DOI:10.54499/UID/PRR/00729/2025 through VICARTE; DOI:10.54499/UIDB/04559/2020 and DOI:10.54499/UIDP/04559/2020) through LIBPhys; and LA/P/0008/2020 through LAQV.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mimoso, J.M.; Esteves, L. Vocabulário Ilustrado da Degradação dos Azulejos Históricos; LNEC—Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil: Lisboa, Portugal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eppler, R.A.; Eppler, D.R. Glazes and Glass Coatings; The American Ceramic Society: Westerville, OH, USA, 2000; ISBN 1-57498-054-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, D. Clay and Glazes for the Potter; Greenberg: New York, NY, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield, L. Special Effect Glazes; Herbert Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, J. Estudos Teórico-Práticos—Disciplina Cerâmica II (Ceramics II—Lecture Notes); Faculdade de Belas Artes da Universidade de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Veronesi, U.; Bandiera, M.; Manso, M.; Ruivo, A.; Vilarigues, M.; Coentro, S. Naples Yellow: Experimental Re-Working of Historical Recipes and the Influence of the Glazing Process in the in Situ Analysis of Historical Artwork. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Y Vidr. 2023, 62, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandiera, M.; Veronesi, U.; Manso, M.; Ruivo, A.; Vilarigues, M.; Esteves, L.; Pais, A.; Coentro, S. The Colour Palette of 16th-18th Century Azulejos: A Multi-Analytical Non-Invasive Study. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 66, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A. Jorge Barradas e Seus Caprichos, Conservação e Restauro de um Painel. Master’s Thesis, Faculdade de Belas-Artes da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sarroeira, S. Jorge Rey Colaço: Estudo, Interpretação e Reprodução de Técnicas Realizadas pelo Artista e Sua Aplicação na Conservação e Restauro de Paineis Azulejares. Master’s Thesis, Faculdade de Belas-Artes da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, E. As Cores Na Azulejaria Portuguesa: Restauro e Caracterização Analítica de dois Conjuntos Azulejares dos Séculos XVII-XVIII Pertencentes ao Museu Nacional do Azulejo. Master’s Thesis, NOVA School of Science and Technology, Caparica, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, M. Estudo, Diagnóstico e Conservação de um Painel de Azulejos Do Século XVIII. Master’s Thesis, NOVA School of Science and Technology, Caparica, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mortari, C.; Nobre Pais, A.; Esteves, L.; Gago da Câmara, A.; Carvalho, M.L.; Manso, M. Raman and X-Ray Fluorescence Glaze Characterisation of Maria Keil’s Decorative Tile Panels. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2021, 52, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F. José António Jorge Pinto, Estudo Sobre o Artista e sua Obra Azulejar. Master’s Thesis, Faculdade de Belas-Artes da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Colomban, P.; Gironda, M.; Simsek Franci, G.; d’Abrigeon, P. Distinguishing Genuine Imperial Qing Dynasty Porcelain from Ancient Replicas by On-Site Non-Invasive XRF and Raman Spectroscopy. Materials 2022, 15, 5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arli, B.D.; Franci, G.S.; Kaya, S.; Arli, H.; Colomban, P. Portable X-Ray Fluorescence (P-Xrf) Uncertainty Estimation for Glazed Ceramic Analysis: Case of Iznik Tiles. Heritage 2020, 3, 1302–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, J.W.; Kim, H.; Oh, Y.; Park, J.; Conte, M.; Kim, J. Selecting Reproducible Elements in Non-Destructive Portable X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis of Prehistoric and Early Historical Ceramics from Korea. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2023, 47, 103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geil, E.C.; Thorne, R.E. Correcting for Surface Topography in X-Ray Fluorescence Imaging. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2014, 21, 1358–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trojek, T.; Trojková, D. Uncertainty of Quantitative X-Ray Fluorescence Micro-Analysis of Metallic Artifacts Caused by Their Curved Shapes. Materials 2023, 16, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, N.A. Pigmentos Sobre a Terra: Painéis Contemporâneos do Acervo de Cerâmica da FBAUL. Master’s Thesis, Faculdade de Belas Artes Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Geraldes, C. Conservação dos Azulejos Modernos Portugueses (1950–1974). Ph.D. Thesis, NOVA University Lisbon, Caparica, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Li, A.; Wu, J.; Yin, Y.; Ma, S.; Yuan, J. Effect of Zirconia Addition Amount in Glaze on Mechanical Properties of Porcelain Slabs. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 20080–20087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Chang, Y.H. Growth without Postannealing of Monoclinic VO2 Thin Film by Atomic Layer Deposition Using VCl4 as Precursor. Coatings 2018, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The RRUFF Project. Available online: https://www.rruff.net/odr/rruff_sample#/odr/view/640650/2010/eyJkdF9pZCI6IjczOCIsInNvcnRfYnkiOlt7InNvcnRfZGZfaWQiOiI3MDUyIiwic29ydF9kaXIiOiJhc2MifV0sIjcwNTIiOiJTaWxpY29uIiwiNzA1NSI6IlNpIn0 (accessed on 11 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.