1. Introduction

Cultural heritage institutions are at a critical juncture. In an increasingly digital world, they face the profound challenge of engaging a new generation of visitors for whom immersive and interactive experiences are not a novelty, but an expectation. Generation Z, born between 1995 and 2010 [

1], has rapidly become a key audience segment, in some cases accounting for over 60% of visitors at major national museums [

2]. As “digital natives” [

3], this demographic possesses high levels of digital literacy and a distinct preference for personalized, participatory, and media-rich content [

4]. This presents a fundamental conflict with traditional exhibition methods, which often rely on static displays, linear pathways, and text-based explanations—formats that frequently fail to meet the expectations of this young audience [

5]. Without a strategic evolution in engagement practices, museums risk a growing disconnect with their future patrons, leading to reduced reach and a diminished role as influential cultural voices.

In response to this strategic imperative, Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a powerful medium for bridging this generational gap. By moving beyond the physical limitations of the gallery space, VR offers the potential to transform cultural heritage from a static monologue into a dynamic, embodied dialogue. Its capacity for high levels of immersion and interactivity can significantly enhance visitors’ emotional resonance and cognitive participation with cultural content [

6,

7]. VR reshapes the narrative logic of heritage by overcoming spatiotemporal constraints, allowing visitors to witness historical events, explore inaccessible sites, or deconstruct artistic processes in ways that promote deeper knowledge acquisition and strengthen memory retention [

8,

9,

10]. This potential has not gone unnoticed; leading institutions worldwide have actively deployed VR, from the Louvre’s Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass to the Tate Modern’s Ochre Atelier, signaling a sector-wide move towards creating more profound, immersive visitor experiences.

However, the mere adoption of technology does not guarantee meaningful engagement. Despite a surge in development, many VR projects within the curatorial field are critiqued for being technologically driven “gimmicks” rather than narratively integrated experiences [

11]. Often, they lack deep integration with core cultural narratives and fail to trigger the intended cultural resonance and learning [

12]. This criticism aligns with broader concerns in digital museology regarding “technological solutionism,” where the focus on a tool’s novelty overshadows its pedagogical and interpretive purpose [

13]. This creates a critical research gap: while museums are investing heavily in VR, there is a lack of systematic, evidence-based understanding of how their target young audiences actually perceive and decide to adopt these technologies. Without a robust theoretical model, the design and evaluation of museum VR risk remaining a matter of intuition rather than informed strategy.

This challenge is magnified when considering the unique characteristics of Generation Z. Their technology acceptance patterns differ markedly from previous cohorts. Heavily influenced by social media ecosystems, they value peer recommendations and user-generated content, making Subjective Norm a powerful driver of their behavior [

14]. Furthermore, their engagement is often predicated on hedonic motivations; they gravitate towards experiences that are not only useful but also entertaining, emotionally resonant, and gamified. These traits suggest that traditional technology acceptance models, which often prioritize utilitarian factors like perceived usefulness and ease of use, may be insufficient to capture the complex decision-making process of this audience in a cultural context. Yet, specific research modeling Generation Z’s acceptance of museum VR remains notably limited.

In this study, we focus on on-site (in-museum) VR experiences, where visitors engage with immersive content during a physical museum visit. Prior research suggests that digitally mediated museum experiences, including VR, can enhance visitors’ willingness to participate in physical on-site visits, indicating a complementary rather than substitutive relationship between virtual engagement and place-based heritage consumption [

15,

16]. Moreover, digital heritage scholarship emphasizes that immersive digitization is intended to enrich interpretation and access to artefacts in situ rather than replace or decontextualize them [

17]. While at-home or online VR exhibitions represent an important parallel domain [

18], they involve different usage contexts and adoption mechanisms and are therefore beyond the scope of the present model.

To address this gap and provide a rigorous foundation for future practice, this study develops and validates an extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) tailored to Generation Z in the museum context. We aim to systematically explore the psychological mechanisms that influence their intention to use museum VR experiences. Specifically, this research seeks to answer the following questions:

What are the key factors, including experiential and social variables, that influence Generation Z visitors’ intention to use museum VR?

How do these factors interact to shape their acceptance behaviors and perceptions of value?

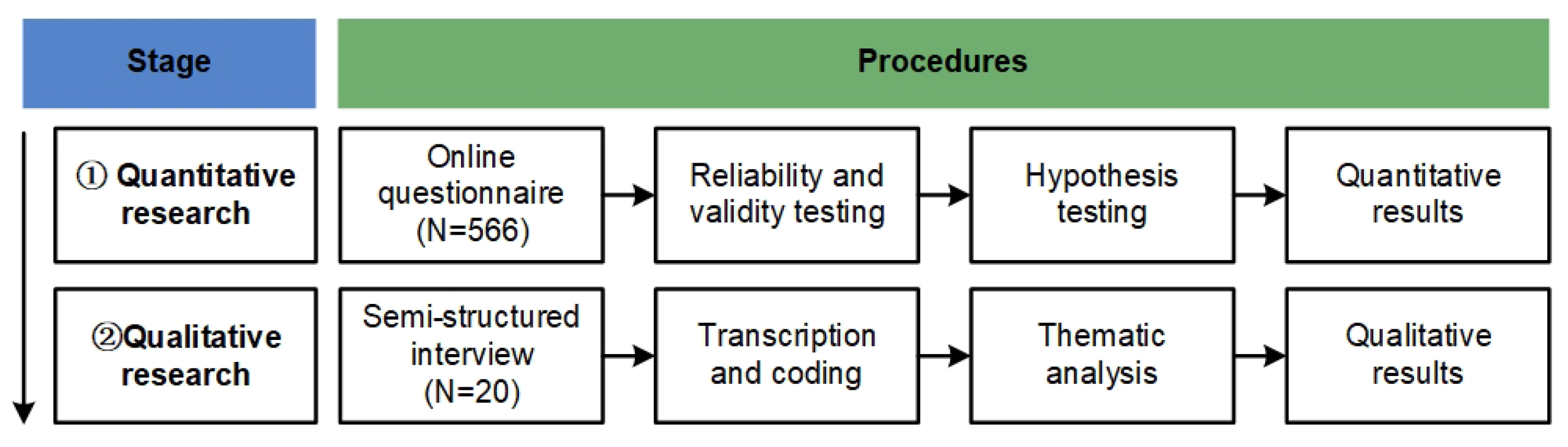

To this end, we employ an explanatory sequential mixed-methods approach, combining a large-scale quantitative survey (N = 566) analyzed via covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) with in-depth, semi-structured interviews (N = 20) for qualitative validation. This study offers a multi-faceted contribution. For HCI and information systems scholarship, it presents theoretical novelty by developing and validating a context-specific extension of technology acceptance theory. For the cultural heritage sector, it provides demographic novelty through the first large-scale investigation into Generation Z’s unique adoption behaviors, yielding an empirically grounded framework and actionable design principles. Finally, it delivers a robust empirical contribution through a mixed-methods study combining a large-scale survey (N = 566) with in-depth qualitative insights, ensuring the generalizability and practical relevance of its findings for creating more effective and resonant VR experiences.

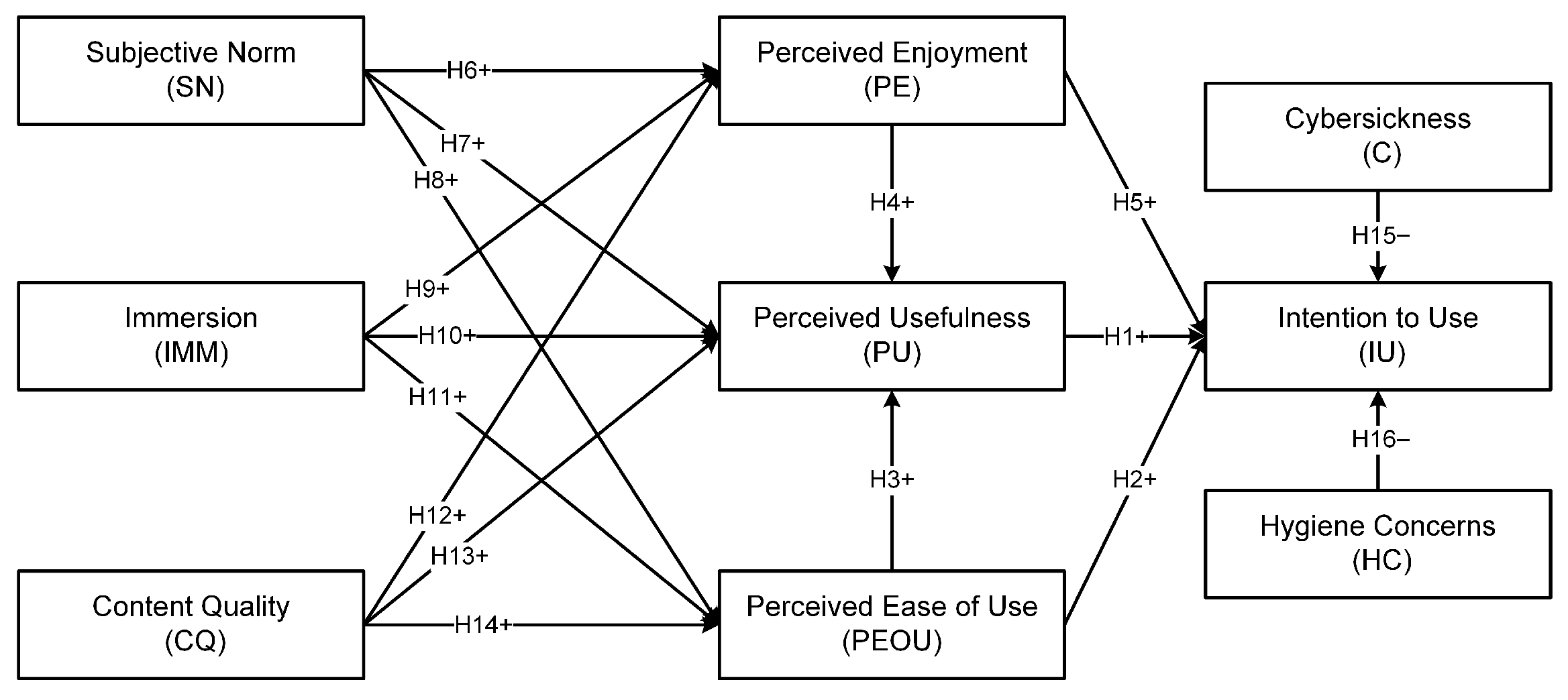

3. Proposed Model and Hypotheses

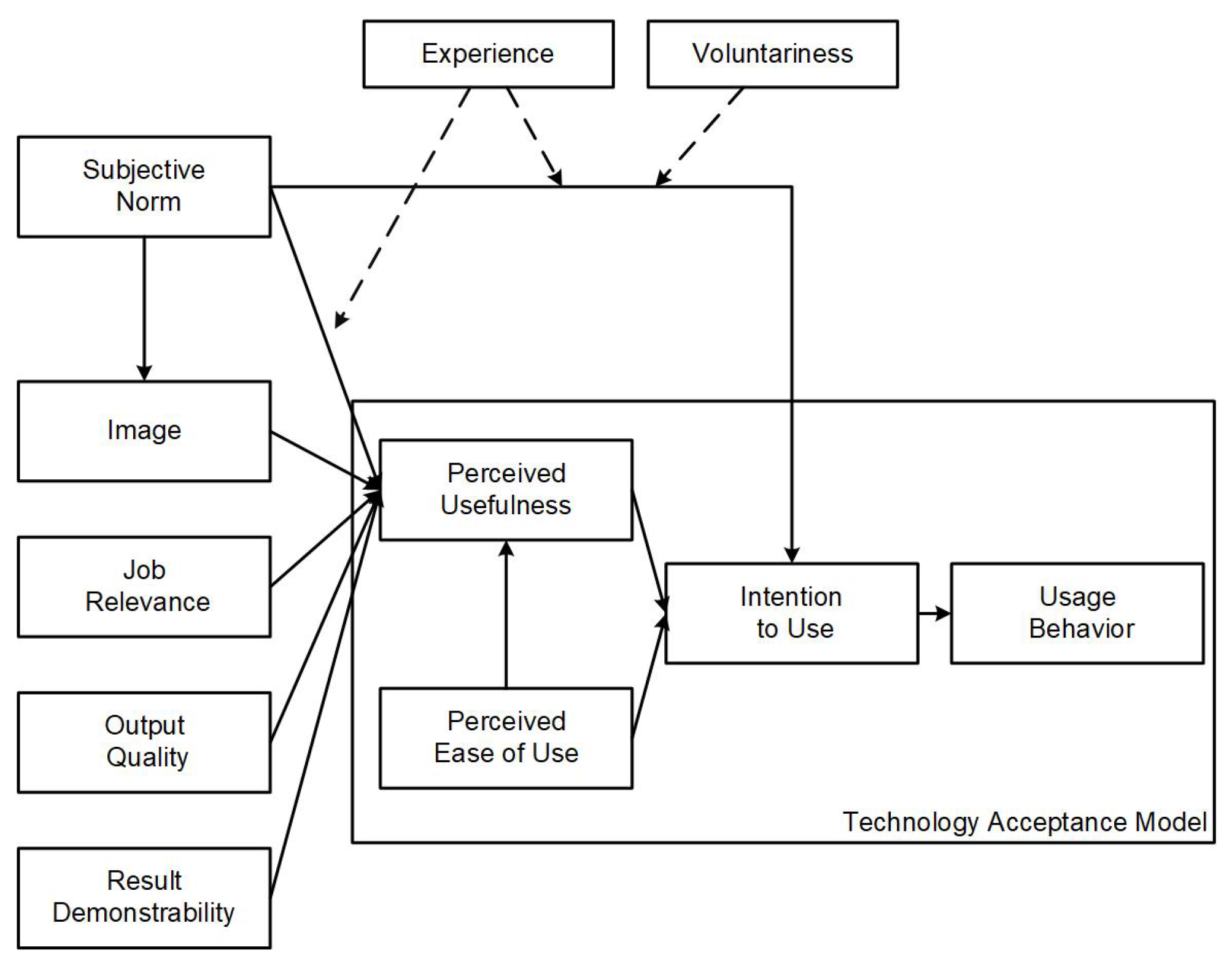

To address the identified research gap, this study develops a multi-dimensional model that synthesizes cognitive, hedonic, social, and contextual factors to explain Generation Z’s acceptance of museum VR. While grounded in the robust theoretical foundations of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [

22], our proposed model is substantially extended to account for the unique characteristics of the cultural heritage context and the target demographic. Specifically, drawing from the insights established in our literature review, the model (depicted in

Figure 2) integrates key variables identified as critical in prior work, including experiential constructs (Perceived Enjoyment, Immersion, Content Quality), social dynamics (Subjective Norm), and context-specific perceived risks (Cybersickness, Hygiene Concerns). This integrated approach moves beyond a purely utilitarian view of technology adoption to provide a more holistic and nuanced explanation of user acceptance in an experientially rich informal learning environment.

3.1. Core TAM Constructs: Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use

Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) are the foundational pillars of TAM. PU refers to the degree to which an individual believes that using a technology will enhance their experience or performance, while PEOU is the extent to which they believe using it will be free of effort [

22]. In the context of museum VR, PU relates to how much visitors feel the technology enriches their understanding and appreciation of cultural heritage. PEOU pertains to the perceived simplicity of operating the VR headset and interacting with the virtual environment. Consistent with decades of TAM research, PU is expected to be a primary determinant of usage intention. Furthermore, a system that is easier to use is often perceived as more useful, as it reduces the cognitive load required to achieve a goal [

23]. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Perceived usefulness positively influences Generation Z museum visitors’ intention to use VR.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Perceived ease of use positively influences Generation Z museum visitors’ intention to use VR.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Perceived ease of use positively influences perceived usefulness.

3.2. Hedonic Motivation: Perceived Enjoyment

Given that museum visits are voluntary, leisure-time activities, hedonic motivations are likely to play a crucial role. Perceived Enjoyment (PE) is defined as the pleasure and fun derived from using a technology itself, independent of any performance consequences [

32]. For Generation Z, an audience that prioritizes experiential and entertaining content, enjoyment is a central component of a digital product’s value proposition [

29]. When visitors find the VR experience intrinsically enjoyable, they are more willing to invest the cognitive effort required for exploration and learning. This heightened engagement leads them to discover more of the exhibit’s educational value, thereby enhancing their perception of the technology’s pedagogical usefulness. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Perceived enjoyment positively influences perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 5 (H5). Perceived enjoyment positively influences intention to use.

3.3. Experiential and Social Antecedents

Based on the literature review, we identified three key external variables that are expected to influence the core TAM constructs: Subjective Norm (SN), Immersion (IMM), and Content Quality (CQ).

Subjective Norm (SN) reflects the social pressure an individual feels to perform a certain behavior [

23]. For the highly connected Generation Z, who rely heavily on peer recommendations and social media trends [

14], the opinions of significant others are powerful influencers. Recent work specifically highlights the significant positive effect of social influence on attitude in the context of museum VR for young users [

30]. Positive social cues are therefore expected to enhance the perceived value, enjoyment, and usability of the VR experience.

Immersion (IMM) is a central affordance of VR, representing the psychological state of being enveloped by and absorbed in the virtual environment. A higher degree of immersion can intensify the experience, making it more engaging, enjoyable, and memorable [

10]. This heightened engagement, closely related to the concept of presence, is fundamental to the user experience in heritage tourism [

27]. It can also make the technology seem more effective as an educational tool (more useful) and more intuitive to interact with (easier to use).

Content Quality (CQ) refers to the perceived quality of the information and presentation within the VR system, including its accuracy, richness, and aesthetic appeal. In the specific context of cultural heritage, CQ also involves the narrative coherence and interpretative depth through which VR contextualizes artefacts historically and culturally. Rather than treating “content” as neutral information, museum VR content is expected to function as heritage interpretation—i.e., helping visitors construct meaning, understand historical backgrounds, and emotionally connect to cultural narratives [

9,

12]. High-quality content is fundamental to a positive visitor experience and engagement [

15]. It enhances the system’s credibility and educational value (PU), makes the experience more pleasurable (PE), and contributes to a more seamless and understandable interaction (PEOU).

Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 6 (H6). Subjective Norm positively influences perceived enjoyment.

Hypothesis 7 (H7). Subjective Norm positively influences perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 8 (H8). Subjective Norm positively influences perceived ease of use.

Hypothesis 9 (H9). Immersion positively influences perceived enjoyment.

Hypothesis 10 (H10). Immersion positively influences perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 11 (H11). Immersion positively influences perceived ease of use.

Hypothesis 12 (H12). Content Quality positively influences perceived enjoyment.

Hypothesis 13 (H13). Content Quality positively influences perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 14 (H14). Content Quality positively influences perceived ease of use.

3.4. Perceived Risks: Cybersickness and Hygiene Concerns

Finally, the model incorporates two potential inhibitors specific to the on-site use of shared VR headsets. Cybersickness (C) refers to symptoms of discomfort, such as nausea or dizziness, that can occur during VR exposure [

33]. Such negative physical experiences are widely recognized as a significant barrier that can deter users from future use [

34]. Hygiene Concerns (HC) relate to user apprehension regarding the cleanliness of shared devices that come into direct contact with the face. In public settings like museums, inadequate sanitation of shared equipment can be a major deterrent, negatively impacting a visitor’s willingness to engage with the technology [

12]. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 15 (H15). Cybersickness negatively influences intention to use VR.

Hypothesis 16 (H16). Hygiene concerns negatively influence intention to use VR.

6. Discussion

This study provides an integrated understanding of Generation Z’s adoption of museum VR by combining quantitative modeling with qualitative insights. The findings not only validate a robust model for predicting use intention but also offer nuanced explanations for the unique ways this digital-native cohort evaluates and engages with immersive cultural heritage technologies. Below, we discuss the theoretical contributions to the field of computing and cultural heritage, and the practical implications arising from these findings.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

This research makes several contributions to the literature on technology acceptance and digital cultural heritage by developing and validating a context-specific model for a critical, yet understudied, demographic.

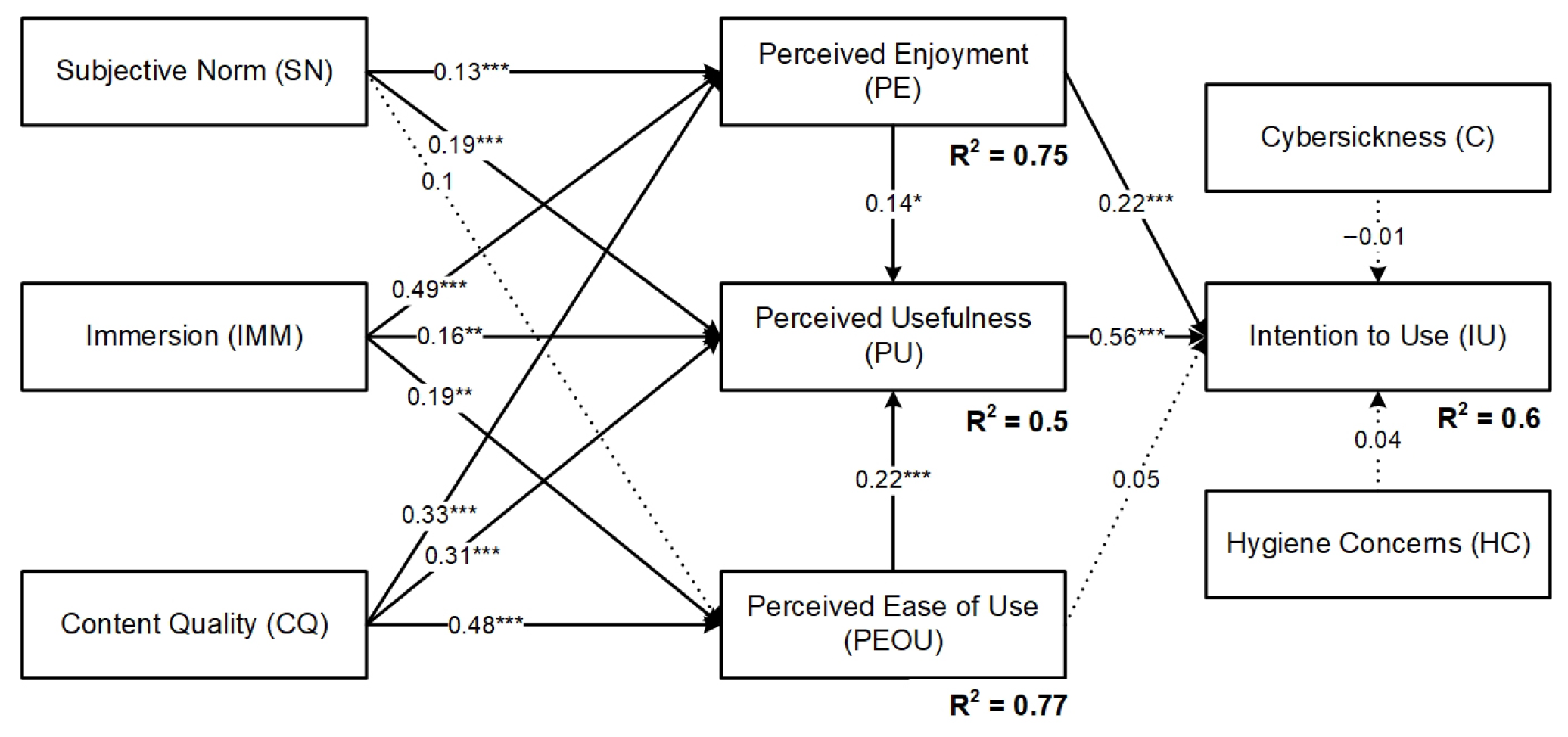

First, our findings confirm that Perceived Usefulness (PU) remains the single most powerful predictor of Generation Z’s intention to use museum VR (

,

), reinforcing a core tenet of TAM [

22]. This aligns with prior studies on immersive cultural heritage experiences within this journal [

15,

24]. However, our qualitative data enriches this finding, revealing that for this audience, “usefulness” is deeply intertwined with enhanced learning, emotional engagement, and memory retention. As one participant noted, the experience of a painting “coming alive” made it ”much more clearly” memorable (P03), validating VR’s pedagogical value in a heritage context [

54].

Second, this study clarifies the shifting role of Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU). While PEOU significantly influenced PU (

,

), its direct impact on intention was non-significant (H2 not supported). This finding, which deviates from the original TAM but echoes recent VR research [

55,

56], is powerfully explained by our qualitative data. Initial usability challenges were noted (P03), but they were consistently framed as minor and rapidly overcome by this digitally fluent cohort (P09). This suggests that for Generation Z users in experiential settings, ease of use has shifted from a primary motivator to a baseline “hygiene factor”; its presence is expected but does not directly drive adoption. This indirect role is also observed in non-immersive screen-based TAM studies, including web archives and conventional virtual exhibition websites, where PEOU tends to influence intention mainly through PU rather than as a direct predictor [

41,

57]. A clear contrast appears in VR acceptance. Traditional interfaces are adopted largely for utilitarian efficiency, whereas in our model intention is shaped by two parallel motives, usefulness and enjoyment. Consistent with digital museum research emphasizing playfulness [

26], Perceived Enjoyment remains a direct driver, and in VR it is strongly supported by Immersion, a sensory and experiential dimension absent in standard video or web presentations. In addition, although TAM2 often reports a weak direct effect of Subjective Norm in voluntary non-immersive settings [

23], SN is significant in our VR model, suggesting that social endorsement becomes more salient when users engage with an immersive and relatively novel medium. This nuanced role of PEOU and the prominence of experiential and social drivers constitute key theoretical contributions of this work.

Third, our model provides strong evidence for the dual importance of hedonic and experiential factors. Perceived Enjoyment (PE) emerged as a significant direct predictor of intention (

,

), supporting the argument that in voluntary, informal learning contexts, hedonic motivation is not secondary but parallel to utilitarian goals [

15]. Crucially, we identified Immersion (IMM) and Content Quality (CQ) as powerful antecedents. IMM was the strongest predictor of PE (

,

), while CQ was a strong predictor for all core TAM constructs. This suggests that for Generation Z, a high-quality, immersive experience constitutes a form of “experiential authenticity” [

10]. The value proposition is not just about accessing content, but about feeling a sense of presence within it [

27], a sentiment captured by participants’ desire to “‘live’ in history for a moment” (P08). Beyond sensory immersion, a key contribution of museum VR lies in its interpretative and narrative function in cultural heritage learning. VR can support historical and cultural understanding by situating artefacts within embodied storyworlds, enabling visitors to experience spatial, temporal, and social contexts that are often inaccessible in physical galleries [

31,

54]. In this sense, VR contributes not merely by “delivering content”, but by creating experiential interpretation that strengthens meaning making, contextual learning, and emotional resonance with heritage narratives [

9]. Accordingly, Content Quality in our model should be understood as a visitor-perceived proxy for interpretative quality, which helps explain its strong effects on Perceived Usefulness (meaningful learning) and Perceived Enjoyment (emotional connection). This interpretative role is also consistent with our interview data, in which participants repeatedly described VR as making heritage feel “alive” and historically situated.

Fourth, the study highlights the critical role of Subjective Norm (SN) as a catalyst for engagement (

for PU,

for PE), a finding consistent with studies that have incorporated social influence into their models [

30]. Our qualitative findings reveal that this is not just about social pressure, but about peer recommendations acting as “a quality filter” (P02) and the VR experience itself serving as ”social currency” for online self-expression (P08). This extends technology acceptance theory by framing social influence not just as a compliance mechanism, but as an integral part of the value discovery and identity-building process for this generation.

Finally, and perhaps most surprisingly, our mixed-methods approach offers a nuanced explanation for the non-significance of perceived risks. Neither Cybersickness (C) nor Hygiene Concerns (HC) were significant deterrents. The qualitative data reveal a pragmatic “cost-benefit” calculus: participants viewed these issues as manageable trade-offs for a compelling experience. Mild discomfort was “worth it” (P01) and hygiene fears were easily assuaged by simple measures like providing wipes (P02). This finding challenges the assumption that such physical factors are absolute barriers and suggests that for motivated young users in a cultural context, the perceived experiential rewards can significantly outweigh the perceived physical risks.

6.2. Practical and Design Implications

Our empirically validated model translates into a set of actionable recommendations for cultural heritage institutions aiming to strategically engage Generation Z. These implications are designed to guide curators, experience designers, and museum strategists in creating more effective and resonant immersive experiences.

For Curators and Content Strategists: Prioritize Narrative Depth over Novelty. The finding that Content Quality is a cornerstone of the entire user experience (H12, H13, H14 supported) is a powerful directive. Resources should be invested in creating VR experiences with high-fidelity visuals, accurate historical information, and compelling, narrative-driven content. VR should be treated not as a tech demo, but as a digital curatorial medium. The goal is to leverage immersion to deepen the story of the artifact or heritage site, not merely to showcase the technology itself. More importantly, VR should be designed as a form of digital heritage interpretation that enables visitors to build cultural meaning, rather than a tool for superficial cultural consumption [

9,

12].

For Marketing and Outreach Managers: Leverage Social Proof and Influencer Engagement. The strong influence of Subjective Norm (H6, H7 supported) confirms that for Generation Z, the path to adoption is often social. Marketing campaigns should be built around peer-to-peer sharing and collaboration with digital influencers in the realms of culture, history, and technology. Institutions can facilitate this by designing “shareable moments” within the VR experience and making it easy for visitors to capture and post their virtual journey, turning visitors into brand ambassadors.

For Experience Designers and Developers: Design for Enjoyment and Manage Risks Proactively. Perceived Enjoyment being a direct driver of intention (H5 supported) means that incorporating elements of play, discovery, and interactivity is not a trivial addition but a core design requirement. Furthermore, while cybersickness and hygiene were not significant deterrents, they remain experiential frictions. Designers should proactively manage these by, for example, avoiding rapid virtual movements that induce motion sickness and working with front-of-house staff to ensure that sanitation protocols (providing disposable masks, wipes) are not only implemented but are also made visible to visitors to build trust.

For Museum Directors and Strategists: Understand the Value Equation of the Next Generation. Our model demonstrates that Generation Z is willing to embrace immersive technologies when the experiential payoff is high. This justifies strategic investment in high-quality VR as a core component of a museum’s engagement portfolio. Rather than viewing it as an ancillary cost, it should be seen as a high-value asset that can increase visitor dwell time, enhance educational outcomes, generate powerful word-of-mouth marketing, and ultimately solidify the institution’s relevance and cultural authority in the post-digital era [

13].

For Museum Directors and Strategists: Plan for Sustainability and Long-Term Maintenance.

Beyond initial deployment, museums should view VR as a maintained service rather than a one-off exhibit. Stable long-term adoption requires planning for hardware replacement cycles, routine technical maintenance, staff facilitation and training, and periodic content updates. Proactive sustainability and maintenance planning can prevent experiential degradation (e.g., malfunctioning devices, outdated narratives) that would otherwise erode perceived enjoyment, usefulness, and continued engagement.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that provide fruitful opportunities for future research. First, the quantitative and qualitative samples were drawn exclusively from a Chinese context. Cultural values and institutional norms may moderate the acceptance mechanisms identified in our model. Future studies could validate the model in different regions and conduct cross-cultural comparisons to test its generalizability.

Second, this study examined Generation Z’s acceptance primarily at the stage of first-time or early VR use in museums. Prior research suggests that initial encounters in virtual museum settings often determine whether Gen Z users are willing to form subsequent and future adoption intentions [

58]. Nevertheless, our cross-sectional design does not capture how perceptions and intentions evolve with repeated use, and thus cannot directly speak to long-term engagement or loyalty. Future research should employ longitudinal or diary-based approaches, or track repeat on-site VR usage, to examine continuance intention and the potential decay or reinforcement of perceived enjoyment and usefulness over time.

Third, the quantitative phase relied on a video stimulus rather than a hands-on VR interaction. Although this approach ensured standardization of exposure, it may have constrained participants’ sense of immersion and underestimated physical risks such as cybersickness, as well as situational concerns tied to sharing headsets on-site (e.g., hygiene cues). Field experiments or on-site data collection with fully interactive systems would strengthen ecological validity.

Fourth, our model focused on psychological and experiential determinants and did not incorporate several potentially relevant contextual variables, such as monetary cost, privacy concerns, or spatial design of VR areas. These factors emerged in the interviews as practical considerations for continued use and should be incorporated into extended models in future work.

Fifth, this study operationalized user experience mainly through Immersion and Content Quality, and did not quantify Authenticity as a standalone latent variable. We acknowledge that authenticity is a crucial factor in shaping visitor responses in heritage-oriented VR experiences [

59]. Prior work also suggests that in VR settings, authenticity is often experienced as presence authenticity generated through immersive perception, rather than only the objective authenticity of exhibited information [

60]. Our qualitative interviews echoed this tendency, as participants frequently evaluated the realness of the experience in terms of environmental fidelity and embodied presence. Future research can extend this framework to the broader spectrum of XR technologies. According to the virtuality continuum proposed by Milgram and Kishino [

61], AR and MR anchor virtual content in the physical world and may strengthen situational authenticity relative to fully virtual VR environments. Comparative TAM-based studies across VR, AR, and MR modalities would be valuable for clarifying how different forms of technological mediation shape authenticity perception and subsequent adoption [

62].

Sixth, our extended TAM focuses on visitor-level psychological determinants of early-stage acceptance and does not model institutional sustainability or long-term maintenance constraints. In practice, museums’ continued adoption of VR also depends on operational resources such as lifecycle cost, device durability, energy use, staffing and training capacity, sanitation/maintenance workload, and the ability to update or refresh digital content over time. Future research could integrate these organizational and sustainability variables into acceptance frameworks, or employ longitudinal field studies to examine how maintenance quality and sustainability planning shape continuance intention and repeat use.

Moreover, our qualitative findings highlight that Generation Z visitors differ markedly in their preferred social context for museum VR. Some participants anticipated shared VR visits with friends or family and felt that being “in the same situation together” would heighten enjoyment, echoing the notion of copresence as a subjective sense of mutual entrainment with others [

63]. Others, however, explicitly preferred solitary engagement, expressing concern that visible avatars or conspicuous co-visitors would disrupt the narrative atmosphere and diminish immersion, a pattern consistent with museum learning research showing distinct benefits of solitary versus shared visits [

64]. Future studies are encouraged to experimentally manipulate social context or compare individual- versus group-based VR, in order to test whether copresence moderates hedonic and immersive pathways in museum environments.