Abstract

The Washington Arms Limitation Treaty 1922 was arguably one the most significant disarmament treaties of the first half of the 20th century. It can be shown that the heritage items associated with this treaty are still extant. Ship’s bells are one of the few moveable objects that are specific to the operational life of a ship and are therefore highly symbolic in representing a vessel. This paper surveys which bells of the ships scrapped under conditions of the Washington Arms Limitation Treaty are known to exist. A typology of ship’s bells has been developed to understand the nature of bell provisioning to vessels newly commissioned into the U.S. Navy. Each of the countries associated with the Washington Treaty have divergent disposal practices with respect to navy property, and this is reflected in both the prevalence and nature of custodianship of ship’s bells from this period. Such procedures range from the U.S. requirement commanding all surplus Navy property to be deemed government property upon ship deactivation, to the British practice of vending ship’s bells to private parties at public sales. However, ship’s bells, like many obsolete functional items, can be regarded as iconic in terms of heritage and therefore warrant attention for future preservation and presentation in the public domain.

1. Introduction

In the past decade, the field of conflict archaeology has moved from being a fringe aspect of heritage management to becoming a sub-discipline in its own right. Much of the work on conflict heritage of the 20th century focusses on a range of military installations and battlefields primarily associated with World War I [1,2,3] and World War II [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11], as well as associated objects such as ships [12], aircraft [13,14], tanks [15], and gun installations [16,17]. There is also an extensive body of research that deals with submerged shipwrecks, both individual wrecks [18] and of groups of sunken vessels, either derived from single military operations [19,20,21] or as part of organized denial through scuttling [22]. Yet little research has been carried out into the whereabouts of ships that were associated with specific events but that were not sunk in action and thus were disposed of in the normal course of action due to their obsoleteness [23].

Such specific events include arms limitation treaties, which are bi-lateral or multi-lateral agreements designed to prevent an escalation of an arms race and thus defuse conditions that could lead to an open military conflict. Most treaties are designed to limit new construction to mutually agreed levels, such as the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935 [24]. A few treaties are designed not only to limit arms to agreed levels, but also to reduce the overall number of arms in the signatories’ arsenals, such as the Washington Arms Limitation Treaty 1922. Despite consensual agreements limiting military assets such as naval tonnage and the make-up of large ships through acts of scrapping or scuttling, there is evidence that heritage items associated with such treaties are still extant [25]. Guns removed from such ships, for example, were re-installed as part of coastal defence systems in areas including the Pacific Coast of the U.S., Micronesia, Aleutian Islands (Alaska), and Banaba (Kiribati) [25]. However, to date, limited research has investigated the fate of vessels and associated items with limitation treaties, and this study is one of the few that do so.

Alongside tangible objects such as armaments existing despite arms limitation treaties, other objects existed that have both tangible and intangible heritage dimensions, the intangible component existing due to a sound being purposefully emanated through the object’s functional use [26,27]. Such an example is a ship’s bell, an object legally required to be provided on all vessels of 12 m or more in length [28].

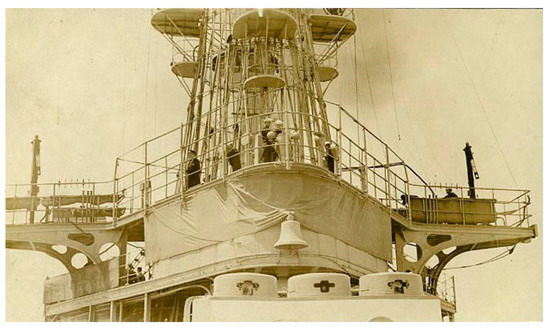

Traditionally, ship’s bells fulfilled two functions, one operational and one navigational. On an operational level, the bell audibly signalled the passing of time on a ship. Crew duties, in particular of naval vessels, were divided into watches of four hours’ duration, with the bell signalling the passage of each half hour (with eight bells signalling the end of watch) [29]. In addition, for vessels at anchor in areas of restricted visibility such as fog, the bell would act as a navigational warning aid, being rung rapidly for about five seconds at intervals of no less than one minute to alert other ships of one’s presence [28]. Any vessel aground in similar weather was required to follow the same bell directive, with the addition of three separate and distinct strokes on the bell immediately before and after the rapid ringing of the bell. Land-based fog bells as well as those located on light vessels served a directional navigational purpose, with the pattern of bell ringing at each location having a distinctive number of strokes within a given period [30,31].

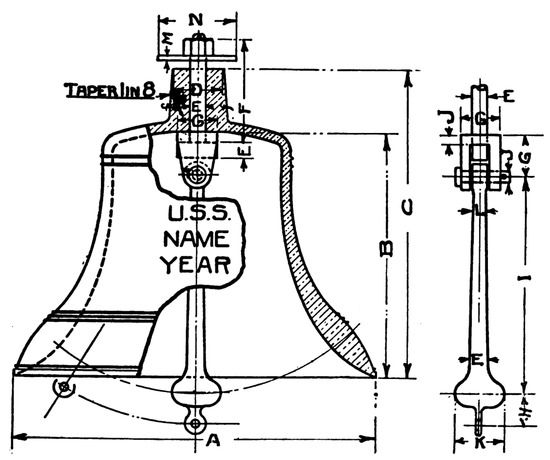

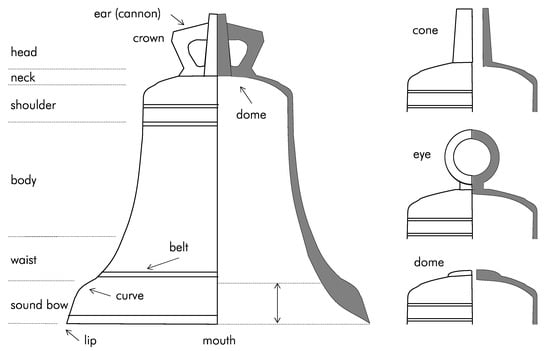

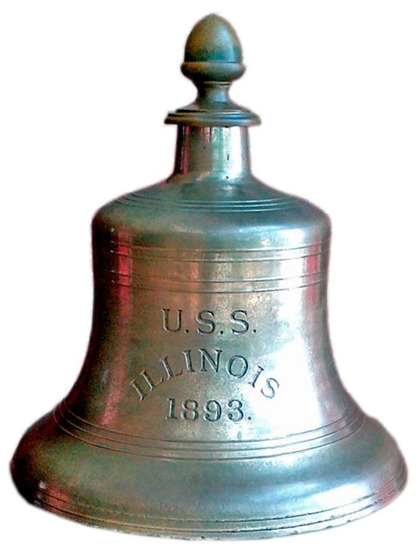

At least among larger ships, the ship’s bell carries the name of the vessel, either in relief or more commonly engraved in large letters, with the engraving blackened to make the name stand out. If a ship’s bell is inscribed also with a year, that date reflects the year the ship was formally commissioned rather than the year it was launched.

The bells of naval vessels hold special significance for the men and women who served on them:

“A warship’s bell is something that all onboard are familiar with. In days gone by they were the ‘heart-beat’ of a ship’s routine, marking the passing of watches and other important ceremonies such as the raising of morning colours when in port or at anchor. Every member of a ship’s company is familiar with its ring and as such these bells are important artefacts which, long after a ship is lost in action or decommissioned, form a ‘touchstone’ for former shipmates and relatives of those who served, fought and died in them”.(John Perryman) [32]

Ship’s bells, apart from builder’s plates, are the only (re-)moveable object specific to any given ship1 and therefore are highly sought after by collectors of maritime memorabilia [33,34,35]. The bells are generally removed once a ship is decommissioned and scrapped, with the bells retained or disposed as the owners deem appropriate. Among shipwrecked and sunken vessels, especially in situations where damage to the vessel is extensive due to environmental decay or due to wartime or collision impact, bells can provide conclusive proof of the identity of a shipwrecked vessel [36,37,38,39,40]. Not surprisingly, they are highly sought after by wreck divers [40,41] specifically because they are a single iconic item and therefore endowed with a “trophy” status [42,43]. Consequently, bells are salvaged for personal collections or for profit, even though they are frequently acquired illegally from protected shipwrecks [38,44,45,46].

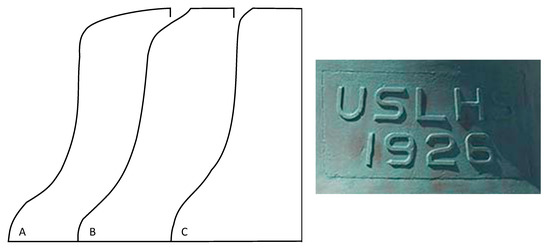

This paper describes the fate of the ships that each of the signatory powers agreed to disarm and scrap as a result of the Washington Arms Limitation Treaty 1922. It also explores specifications, characteristics, and current locations, custodianships, and dispositions of any surviving ship’s bells associated with these vessels. In doing so, it provides a classification of U.S. Navy and Lighthouse Service bells to create a novel working typology for ship’s bells of this period.

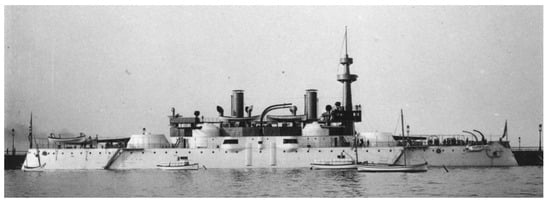

3. The Fate of the Washington Ships

To comply with the conditions, each of the signatory powers agreed to disarm and scrap within 18 months a large number of capital ships based on a scrapping and replacement schedule (Washington Arms Limitation Treaty 1922 Part 3 § 2). Onwards sale of these ships was not permitted. Not surprisingly, of course, it was the old and outdated ships that were struck off the active lists as well as ships that were under construction but were not completed (Table 1, Figure 1 and Figure 2). Although the specific scrapping of existing vessels without replacement (in order to reduce existing tonnage to agreed limits) was restricted to the British Empire, the United States, and Japan, both Italy and France also decommissioned warships that otherwise would have been retained for several years. As they were essentially obsolete, however, they were scrapped in order to free up tonnage for new construction. These vessels, such as the formerly Austrian and later Italian SMS Tegethoff (1912), were excluded from this study.

Table 1.

The details and fate of the warships disposed of under the terms of the Washington Arms Limitation Treaty (for details of shipyards).

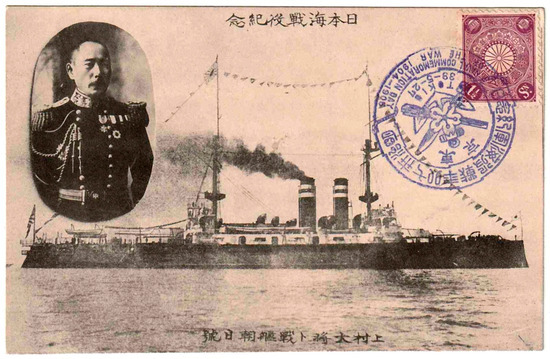

Figure 1.

The Japanese battleship Asahi (朝日) as shown on a contemporary postcard (source: author). (The captions on the card read 日本海戦役記念/Sea of Japan Campaign Memorial and 上村大将と戦艦朝日号/General Uemura and Battleship Asahi).

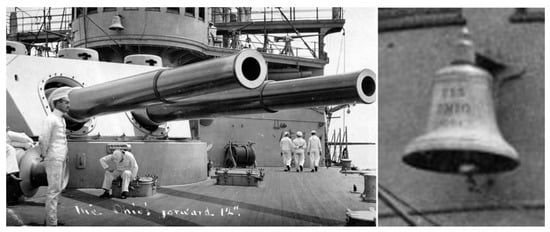

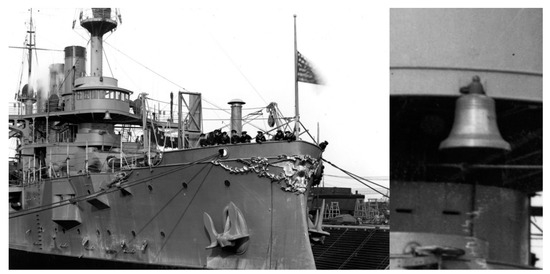

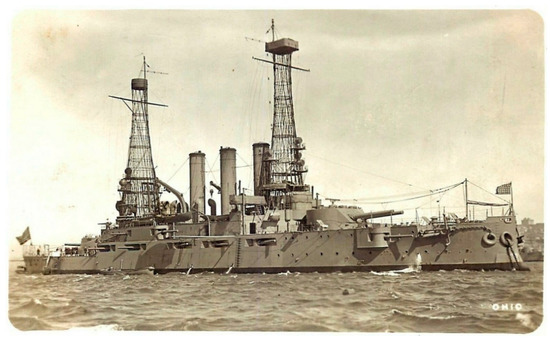

Figure 2.

The U.S. battleship USS Ohio (BB–12) as shown on a contemporary real photo postcard (source: author).

The cultural heritage assets related to the development and signature of the Washington Arms Limitation Treaty, in particular the fate of the vessels and their armament, have been discussed elsewhere [25], so a brief summary may suffice. In principle, the signatory nation was at liberty to dispose of its ships via three options: breaking up the vessel for scrap, scuttling and sinking it, or using it for target practice, with subsequent scrapping or scuttling. In addition, and subject to the acquiescence of the other signatories, a small number of ships could be disarmed and retained for non-combatant purposes, such as training hulks. In the process of disposal, the armament of most vessels was landed and placed in storage for later use as coastal defence guns or on merchant vessels during WWII [25,56,57,58,59]. Given the adjustment in tonnage needed, the scrapping or scuttling only affected the fleets of the Empire of Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America (Table 1).

6. Japanese Bells

Data on the nature and fate of the bells associated with the Japanese ships are very limited and nothing has been formally published on the bells in general. The background of the 15 Japanese vessels scrapped under the treaty is complex. Five ships were built at British shipyards as part of the original battleship development of the Japanese Fleet [159]. These were the Asahi (朝日) (1900), built by John Brown & Co. at Clydebank (Figure 1); the Shikishima (敷島) (1900), built by Thames Iron Works, Blackwall, London; the Kashima (鹿島)(1906), built by Armstrong Whitworth, Elswick; and the Mikasa (三笠) (1902) and the Katori (香取) (1906), both built by Vickers, Barrow-in-Furness [159,160]. It can be surmised that these vessels, on commissioning, would have received bells from British castings.

Eight of the ships were built by Japanese yards, with the Aki (安芸) (1911), Ibuki (伊吹) (1907), Ikoma (生駒) (1908), and Settsu (摂津) (1912) built by the Kure Naval Arsenal; the Kurama (鞍馬) (1911) and the Satsuma (薩摩) (1910) built by the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal; and the Amagi (天城) and Tosa (土佐) (1921) built by the Mitsubishi shipyards in Nagasaki. It can be assumed that these Japanese-built vessels, on commissioning, would have received bells from Japanese castings. The construction of the battlecruiser Amagi was halted following the signing of the Washington Treaty, with subsequent conversion into an aircraft carrier. Damaged on the slipway during the Kanto earthquake (September 1923), the Amagi was never completed and was broken up as a part-build [161]. As it was never commissioned, no bells would have been issued.

The origin of the remaining two vessels is even more complex. The Iwami (生駒) was originally the Russian battleship Oryol (Орёл), built at the Galerniy Island Shipyards in Saint Petersburg (Russia) and commissioned in 1904. The vessel was disabled and captured in the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905. Repaired at the Kure Naval Yards, the Oryol was commissioned into the Japanese Navy as the Iwami in 1907 [160]. The Hizen (肥前) was also originally Russian battleship Retvizan (Ретвизан), built by William Cramp & Sons Shipbuilding in Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA, USA) and commissioned in 1902. Sunk in December 1904 at Port Arthur, the Retvizan was likewise re-floated, repaired at Sasebo Naval Yard, and commissioned into the Japanese Navy as the Hizen in 1908 [160]. We can assume that the Iwami (ex-Oryol) would have been commissioned into the Imperial Russian Navy with a bell of Russian casting, and the Hizen (ex-Retvizan) with a bell of U.S. casting supplied by the shipyard. Given that the Retvizan was launched in October 1900 and commissioned in March 1902, the battleship is synchronous with USS Maine (BB-10), also built by William Cramp & Sons, which was launched in July 1901 and commissioned in December 1902. We can speculate that the bells of these two vessels would have been replaced with bells of Japanese castings once the vessels were repaired and commissioned into the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Surviving Bells of Japanese Vessels

Pre-World War II, HJMS Mikasa (三笠) held a special place in the minds of the Japanese government and people, because, as Japan’s most modern battleship, she served as Admiral Togo Heihachiro’s flagship in the 1904 attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur and in the Battle of Tsushima on 27/28 May 1905, when the Japanese Navy decisively defeated the Russian fleet. Soon after the implications of the Washington Arms Limitation Treaty became public, the threat of losing the Mikasa as a symbol of Japan’s rise to a naval power gave rise to a popular movement [162,163] that succeeded in it being preserved as a historic vessel at Yokosuka and opened as a memorial ship in 1926 (Figure 20) [160].

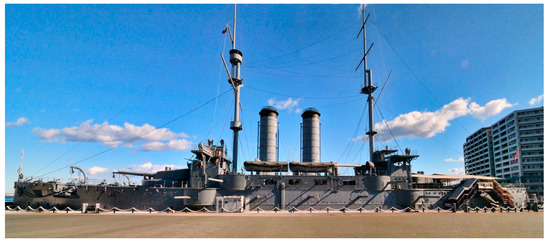

Figure 20.

The Memorial Battleship Mikasa (三笠) at Yokosuka Harbor (three-image composite by DHRS).

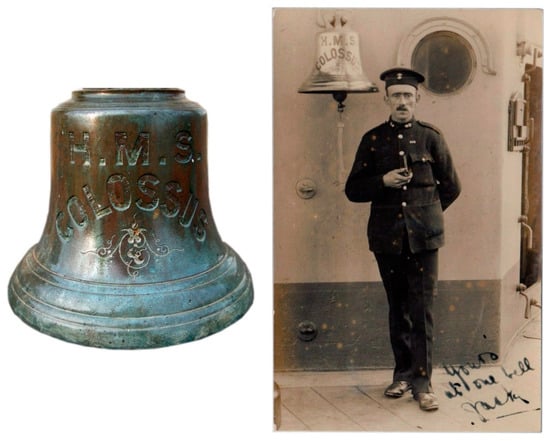

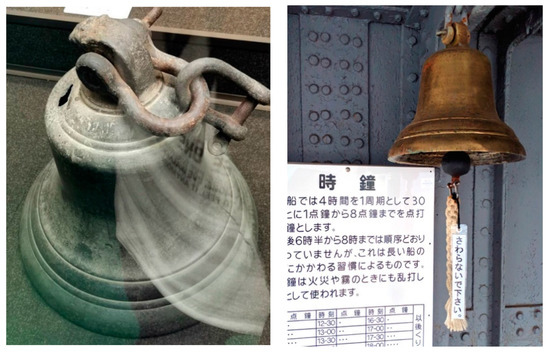

The exhibition on board the museum ship Mikasa contains the original bell that was slightly damaged during U.S. air raids on Yokosuka during World War II. The shape of the bell exhibits a strongly carinated, broad beading with two beads on the neck, two widely spaced beads on the waist, and an undecorated sound bow. The bell is suspended with a solidly cast eye with a rounded top. The profile and decoration of the bell do not resemble that of bells of British casting (see above), suggesting that this is Japanese cast. Why the original bell was removed is unclear. A second, undamaged bell is suspended at the quarterdeck and can be rung by visitors to the ship.

One of the bells of the battlecruiser Ibuki (伊吹) (1907), in addition to the ship’s wheel [164] and a model of the vessel [165], were promised to the Australian government in 1923, after the acting Prime Minister, Earl Page, requested a memento of the vessel that was in the process of being broken up [166]. The vessel’s relevance to Australia rests in the fact that in November 1914, in conjunction with HMAS Sydney, the Ibuki escorted the troopships carrying the Australian and New Zealand Auxiliary Corps (ANZAC) across the Indian Ocean to their staging post in Egypt [167]. The bell and wheel arrived in Australia in December 1925 and went on display in the temporary Australian War Memorial in Melbourne until 1935 [166]. The bell is of Japanese casting, possibly manufactured at Kure Naval Yard, where the vessel was built. The profile and decoration of the bell, with its strongly carinated, broad beading (Figure 21), is the same as that of the Mikasa (Figure 22). The bell of the Ibuki measures 480 mm in height and 450 mm in diameter. Its weight has not been documented [168].

Figure 21.

The bell of the Ibuki (伊吹), held by the Australian War Memorial (RELAWM08239).

Figure 22.

The bells of the Mikasa (三笠) at the Memorial Battleship museum at Yokosuka. (Left) damaged bell on display. (Right) quarterdeck bell for ringing by visitors (photo hawk26) [169].

There appears to have been no formal process of retention of ship’s bells once vessels were decommissioned. Some of these seem to have been passed into private hands. In addition, there is an indication that bells did not stay with a ship from commissioning to final decommissioning but rather could be changed over mid-career. The bell of the Asahi (朝日) (Figure 1) is very illuminating in that regard. In October 2020 a bell 22 cm in diameter, 23 cm in height, and with an approximate weight of 3 kg was sold at auction on Yahoo Japan (Figure 23) [170]. The size of the bell suggests that this was the quarterdeck bell. The bell carries two inscriptions on its sound bow: “本帝国海軍艦朝日” (i.e., “Imperial Navy Ship Asahi”) and “明治参拾七年調” (i.e., “Meiji 37” (1904))9. The Asahi, which was laid down in August 1898, launched on 13 March, 1899, and commissioned on 28 April, 1900, was placed on the list of ships to be disposed of under the Washington Treaty. The vessel was reclassified as a training and submarine depot ship on 1 April 1923, and completely disarmed three month later [160]. Following a brief career as submarine tender and salvage and repaid ship, as well as a floatplane test ship, the Asahi was mothballed in reserve in 1928. In 1937 she was reactivated as a repair ship and torpedo depot ship, seeing limited service in the Pacific War. She was sunk on 25/26 May 1942, some 160 km southeast of Cape Padaran, Vietnam [160].

Figure 23.

The quarterdeck bell of the Asahi installed after the 1904 repair. (a) full bell; (b) detail of the inscription. For translation of inscription, see text (source: sutanisurao_0323).

This now raises the question as to the nature of the bell, given that the Asahi was built by John Brown & Co and upon commissioning would have received a bell of British casting, which should have gone down with the ship in 1942.

The Asahi was damaged in the Battle of the Yellow Sea (August 1904) by a Russian shell as well as two of her own shells that exploded prematurely in barrels of the 12 in aft turret [172,173]. She was repaired and headed back to support the blockade of Port Arthur, where she was severely damaged by a Russian mine on 26 October, 1904. Repaired at the Sasebo Naval Arsenal from November 1904 to April 1905, the Asahi re-joined the fleet to participate in the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905 [174]. It would appear that on the occasion of the repair in November 1904, the British-cast bell was replaced by a Japanese cast. It should be noted that the profile and decoration of this bell deviates from the bells of the Mikasa and Ibuki.

7. Discussion

As the preceding assessment has shown, the survival and preservation of bells from the warships disposed of under the terms of the Washington Arms Limitation Treaty varies significantly between the three nations: Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. Notwithstanding the small number of bells that cannot be located at this time, the majority of the bells derived from U.S. Navy vessels have survived. This can be attributed to the persistence and efforts of the Naval History and Heritage Command to collect these bells, which is exemplified by the great lengths that the U.S. Navy’s Naval History and Heritage Command went to in order to claim title and possession of the bell of USS Vestal [99]. Another factor that should not be discounted, however, is the fact that U.S. Navy battleships were named after the states of the Union, and that the states took great pride in “their” ships, as is evidenced by the silver sets that were often given to the captain’s mess, often accompanied by formal accounts of fundraising and details of the sets [175]. Not surprisingly, then, many of the bells are prominently displayed in or at public buildings in the respective states (see Table 7).

Table 7.

The disposition of the bells associated with warships disposed of under the terms of the Washington Arms Limitation Treaty.

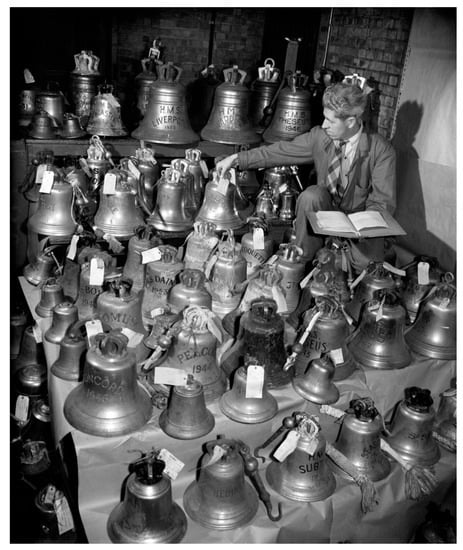

This obsession with claiming ownership over every single main and quarterdeck bells of major U.S. Navy vessels stands in total contrast to the discard program run by the Royal Navy. Here, all bells of decommissioned vessels were sold to the public, with preference given to the officers and ratings who had served on the vessel in question. Consequently, the bells are scattered far and wide, with the overwhelming majority, if they still survive, held in unknown private hands. A few bells are held in public collections, such as the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich and the Imperial War Museum in London. Exceptions are the inscribed bells of HMAS Australia and HMS New Zealand, which are held in the military museums of the respective namesake countries. The preservation of the bells as mementoes of the battlecruisers is a manifestation of the national pride of the nascent nations to fund a battlecruiser each as an Empire contribution to the Royal Navy. As such, then, the preservation can be seen in the same light as the preservation of the bells of the U.S. battleships named after the states of the Union.

The preservation of HJMS Mikasa as a museum ship and national memorial was a matter of national pride, and a cause célèbre for the Japanese delegation when negotiating the terms of the Washington agreement. As noted, Australia and New Zealand retained the bells and their namesake vessels. No such patriotic sentiment extended to the bells of the other decommissioned British and Japanese battleships and battlecruisers.

That the Royal Navy placed so little emphasis on the protection and preservation of naval bells is exemplified in the iconic British warship HMS Dreadnought. Modern naval history uses the launching of the all big-gun HMS Dreadnought in 1906 as a watershed in naval design (Figure 24), noting that ships either belong to the pre-Dreadnought era or are classified as “modern” battleships [178,179]. During the early part of the 20th century, the term “dreadnought” was synonymous with, and a portmanteau for, a modern battleship, akin to “hoover” for a vacuum cleaner or “kleenex” for a paper tissue. Having made all earlier battleships essentially obsolete, the design of HMS Dreadnought sparked an arms race among all major naval powers [178]. Although revolutionary, in the eyes of the British naval architects of the World War I era, HMS Dreadnought was already dated by 1911, when it lost its status as flagship of the Home Fleet, and quite outdated at the outbreak of the war, having been supplanted by “superdreadnoughts” such as HMS Orion (also scrapped as part of the Washington Treaty). As HMS Dreadnought was in refit at the time and saw no action in the major naval battle of World War I (the Battle of Jutland), its wartime service history was limited [136]. Consequently, there was at the time little desire to conserve any meaningful objects as part of the vessel’s heritage. Although the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich owns a bell of the 98-gun second-rate ship of the line HMS Dreadnought launched in 1801, it does not own the bell of the first “real” battleship of the modern era. The only object of the HMS Dreadnought in question known to have been preserved in collections in public hands is an unofficial gun tampion kept by the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich (Inv. Nº AAA1696) [180].

Figure 24.

HMS Dreadnought as depicted on a contemporary real photo postcard (source: author).

In the 1920s, when the vessels were decommissioned and scrapped, the concepts of heritage preservation and values-based significance assessment were unknown. With the benefit of hindsight, the bells of HMS Dreadnought would have been the bells to collect and preserve in public hands. It can only be hoped that it still exists safely in private hands and that its cultural significance is appreciated by its current owner.

When assessing the heritage significance of the bells of the other scrapped British battleships and battlecruisers, we need to consider their service history and involvement in the various naval engagements of World War I (Table 8). A large number of vessels, with the exception of HMS Agamemnon, which at the time was stationed in the Mediterranean, took an active part in the major naval battle of World War I, the Battle of Jutland (31 May–1 June 1916). In most cases, that was the only action they saw. Only four of the ships listed in Table 8 saw action in more than one battle. HMS Lion, Admiral David Beattie’s flagship, and HMS New Zealand were involved the Battle of Heligoland Bight (28 August 1914), the Battle of Dogger Bank (23 January 1915), and the Battle of Jutland. HMS Indomitable saw action in the Battle of Dogger Bank and the Battle of Jutland, and like HMS Inflexible, was also involved in the landings at the Dardanelles (Gallipoli) in the Eastern Mediterranean. The latter battlecruiser had already taken part in the Battle of the Falkland Islands (8 December 1914), where it was involved in annihilating Admiral von Spee’s Pacific squadron.

Table 8.

The combat service during World War I of the British vessels discussed in this paper.

From a cultural heritage and collections perspective, the bells of HMS Lion, for its role as Beattie’s flagship and involvement in three major naval battles in the North Sea, and HMS Inflexible, for its involvement in three theatres of war (Mediterranean, North Sea, and South Atlantic), are the most significant. From a World War I service point of view, of least significance are the bells of HMS Commonwealth, HMAS Australia, and HMS Dreadnought. The latter two vessels have significance, of course, as being the first true modern battleship (HMS Dreadnought, see above) and being the first battlecruiser financed by the nascent Commonwealth of Australia (HMAS Australia).

It is of interest to note that with the exception of the already mentioned bells of HMS New Zealand and HMAS Australia, none of the bells are in public hands. The accessions of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich and the Imperial War Museum seem to have been opportunistic without clear targeting of significant vessels. Thus, the main bell of HMS Tiger, the oldest battlecruiser retained by the Royal Navy after the fleet reduction subsequent to the Washington Arms Limitation Treaty, is held by the Imperial War Museum [138], but the bells of the significant vessels of World War I are not. It appears inexplicable why the bell of HMS Lion was not retained for public display.

Irrespective of formal significance assessments, ship’s bells may hold a high level of significance today for individuals associated with maritime history, as illustrated by the case of the bell of USS New Jersey (BB-16). The Battleship New Jersey Museum (BB-62) wanted to develop an exhibit about its namesake predecessor. As the original bell of the USS New Jersey is on permanent display in front of City Hall in Elizabeth, NJ, the museum commissioned a 3D-printed full-size replica [181]. The significance of public engagement and ownership of maritime heritage is further exemplified in an account of the movement of the bell of USS Montana. Although referring to the earlier ACR-13 rather than the BB-51, which was scrapped under the Washington Limitation Treaty, the story of two rival fraternities engaging in a 43-year contest over a ship’s bell speaks highly of the pride and significance placed on such objects [70]. This is especially the case here; the USS Montana was renamed USS Missoula, with the victor being a fraternity based in the city of the same name, despite the bell having the inscription of the original ship’s name.

The trophy status of ship’s bells alluded to in the introduction also manifests itself in bells taken off enemy vessels that were captured intact or as wrecks. These bells tend to be in public collections, and often placed on exhibition. An example from World War I are the bells of the Imperial German cruiser SMS Emden, which was destroyed by HMAS Sydney at the Cocos and Keeling Islands in November 1914, and which are now on display in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra [182] and the Imperial War Museum in London [183]. An example of World War II is the bell of the German WWII-era heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, famous for its role in the Battle of the Demark Strait when the Bismarck sank the British battleship SMS Hood. The Prinz Eugen was surrendered to British Navy at the end of the war, passed to the USA as a war prize, and deployed by the U.S. Navy as a target ship for atomic bomb tests in Bikini Atoll in 1946 [88].

In addition to the bells, and setting aside the guns that had been landed and subsequently used in coastal defence [17,56,57,58,59], there are few other elements of the scrapped vessels that have survived (Table 9). These primarily comprise the celebratory silver service given by the namesake state to the officer’s mess of U.S. battleships, but also include ships’ wheels, a gun tampion, and a foremast (Figure 25).

Table 9.

Some examples of other surviving items of the warships scrapped under the terms of the Washington Arms Limitation Treaty.

Figure 25.

The foremast of USS Oregon erected in 1956 at Tom McCall Waterfront Park in Portland, OR (photo: Lia Brown).

8. Implications

That some individuals and even countries go to great lengths to retain and display naval bells greatly demonstrates the iconic nature of a ship’s bell: being a trophy of a key battle, or a symbol of past histories or iconic moments, such as the beginnings of an emergence of a country unto its own. That a large number of (particularly British and Japanese) bells are unaccounted for does not suggest disinterest or indifference towards these items. On the contrary, the ownership of many such bells by ex-service personnel suggests a deep connection to past histories and practices. The central issue that presents itself here is the matter of public and private ownership of such items. To what extent should iconic heritage items be accepted exclusively into the private domain? One could be reminded of a Van Gogh or Monet being in the possession of a private collector, but this analogy is delusionary—works of art are often commissioned and usually do not have the ability to be representative icons of a country’s military prowess. Instigating retrospective governmental or public ownership of such items may not only impractical but may well also be disrespectful to any individual who obtained a ship’s bell by legal means and where the custodial chain of legal ownership can be demonstrated. In particular, this applies to the British bells where, as shown above, the Royal Navy intentionally disinvested itself of ownership and irrevocably abandoned any claim to the bells. In the Japanese case the processes are less clear, but as the vessels were disposed of the 1920s, we can assume that illegal transmission in ownership would not have occurred. We may need to differentiate the legal from the moral dimension, however. Clearly, it would be preferable that bells associated with vessels that have a high level of cultural significance be held in public hands. Although heritage value criteria have been developed for heritage structures [189,190], they do not exist for ship’s bells.

In this paper we took some steps when assessing the significance of the bells of British vessels. The question then arises regarding the processes that should be developed to “reclaim” culturally significant bells in private hands. Although there is a body of literature dealing with the repatriation of objects acquired in colonial settings [191,192,193], this is conceptually different and thus has only limited informative value.

The implications of this paper are futures based. Careful thought and planned action needs to be undertaken for any item that may be indicative of being considered worthy as public heritage, representative in the naval domain, or otherwise. This may be critically so with reference to items that are at risk of, or are considered to be, redundant and therefore obsolete, as the scrapping of or cessation of action marks the finality of the item in working order.

Furthermore, the manner of exhibition and presentation of objects such as ship’s bells in public spaces could also be amended to incorporate intangible heritage qualities such as emanated sound. With the history of ship’s bells being utterly entwined as functioning items, fulfilling both operational and navigational functions as well as forming a touchstone for those who have associations, to have a naval bell silently resting as a museum piece misses the heartbeat of the history and presents a dehumanised form of a cold metallurgic body.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.H.R.S.; methodology, D.H.R.S.; formal analysis, D.H.R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.H.R.S. and M.P.; writing—D.H.R.S. and M.P.; visualization, D.H.R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethics approval.

Acknowledgments

A study like this would not be possible without the support of a wide range of custodians of the bells and other individuals with pertinent knowledge. We are gratefully indebted to the following for the provision of details or images of their bells and other contextual information: May Ames Booker (Battleship North Carolina Inc., Wilmington, NC, USA); Kate Brett (Naval Historical Branch, HM Naval Base, Portsmouth, UK); David Briska (Dunkirk Lighthouse & Veterans Park Museum, Dunkirk, NY, USA); Erika Broenner (The Verdin Co, Cincinnati, OH, USA); Denise Clemons (Archivist, Historical Society, Lewes, DE, USA); Lia Brown (Washington, DC, USA); Ann Coats (School of Civil Engineering & Surveying, University of Portsmouth, UK); Lea French Davis (Curator Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, DC, USA); Cliff Eckle (Ohio History Connection, Columbus, OH, USA); Jessica Eichlin (West Virginia & Regional History Center, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, USA); Scarlet Faro (Royal Museums Greenwich, UK); Carmen Gunther (Ashford, Kent, UK); Mark J Halvorson (Battleship Texas Foundation, Bismarck, ND, USA); Ellen J. Henry (Ponce de Leon Inlet Lighthouse Preservation Association, Ponce Inlet, FL, USA); Desiree Heveroh (East Brother Light Station Association, Richmond, CA, USA); Richard Holdsworth (Historic Dockyard Chatham, Kent, UK); Katelyn Kean and Peter Lesher (Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, St. Michaels, MD, USA), Ellen Kennedy (National Museum of the Great Lakes, Toledo, OH, USA), John W. Keyes (Hospital Point Range Front Light, USCG); Anne L’Hommedieu (Sodus Bay Lighthouse Museum, Sodus Point, NY, USA); Tony Lovell (Dreadnought Project, Cambridge, MA, USA); Jane Peek (Military Heraldry & Technology, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, ACT), Maribeth Quinlan (Collections Access & Research, Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, CT, USA); Cristian Rivera (Battleship Texas Foundation, Elizabeth, NJ, USA); Minoru Shiroyama (Takasago, Hyogo Prefecture, Japan); Richard Southwell (Upton Lovell, Wilts, UK); Lane Sparkman (Rhode Island Department of State, Providence, RI, USA); Kandace Trujillo (Battleship Texas Foundation, Houston, TX, USA); Michael A Ward (Army ROTC, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA); Judith Webberley (Naval Dockyards Society, Waterlooville, Hants, UK); and Jack Zeilenga (Vermont State Curator’s Office, Montpelier, VT, USA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Stichelbaut, B.; Note, N.; Bourgeois, J.; Van Meirvenne, M.; Van Eetvelde, V.; Van den Berghe, H.; Gheyle, W. The archaeology of world war I tanks in the Ypres Salient (Belgium): A non-invasive approach. Archaeol. Prospect. 2019, 26, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheyle, W.; Dossche, R.; Bourgeois, J.; Stichelbaut, B.; Van Eetvelde, V. Integrating archaeology and landscape analysis for the cultural heritage management of a World War I militarised landscape: The German field defences in Antwerp. Landsc. Res. 2014, 39, 502–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hollebeeke, Y.; Stichelbaut, B.; Bourgeois, J. From landscape of war to archaeological report: Ten years of professional World War I archaeology in Flanders (Belgium). Eur. J. Archaeol. 2014, 17, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrell, T.; Burns, J.; McKinnon, J.; Krivor, M.; Enright, J.; Roth, M.; Pascoe, K.; Raupp, J.; Arnold, S.; Keusenkothen, M. Peleliu’s Forgotten WWII Battlefield; Ships of Exploration and Discovery Research: Santa Fe, NM, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, J.F.; Carrell, T.L. Underwater Archaeology of a Pacific Battlefield: The WWII Battle of Saipan; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Using KOCOA Military Terrain Analysis for the Assessment of Twentieth Century Battlefield Landscapes. Heritage 2020, 3, 753–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R.; Poynter, C. Using 3-D spatial visualisation to interpret the coverage of Anti -Aircraft Batteries on a World War II Battlefield. Heritage 2019, 2, 2457–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushynsky, J. Defining Karst Defenses: Construction and Features. Hist. Archaeol. 2019, 53, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passmore, D.G.; Harrison, S.; Tunwell, D.C. Second World War conflict archaeology in the forests of north-west Europe. Antiquity 2014, 88, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tunwell, D.C.; Passmore, D.G.; Harrison, S. Landscape archaeology of World War Two German logistics depots in the forêt domaniale des Andaines, Normandy, France. Int. J. Hist. Archaeol. 2015, 19, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, C.; Gater, J.; Saunders, T.; Adcock, J. D-Day: Geophysical investigation of a World War II German site in Normandy, France. Archaeol. Prospect. 2004, 11, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg, H. Japanese Midget Sub at Pearl Harbor: Collaborative Maritime Heritage Preservation. In Underwater Cultural Heritage at Risk: Managing Natural and Human Impacts; Grenier, R., Nutley, D., Cochran, I., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Last Flight of the “St. Quentin Quail”. Investigations of the Wreckage and History of Consolidated B-24 “Liberator” Aircraft #42-41205 off Jab’u Island, Arno Atoll, Republic of the Marshall Islands; The Johnstone Centre for Parks, Recreation and Heritage, Charles Sturt University: Albury, Australia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lickliter-Mundon, M.; Cantelas, F.; Coble, W.; Kinney, J.; McKinnon, J.; Meyer, J.; Pietruszka, A.; Pilgrim, B.; Pruitt, J.R.; Van Tilburg, H. Identification of a Deep-water B-29 WWII Aircraft via ROV Telepresence Survey. J. Marit. Archaeol. 2018, 13, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, M. Landing at Saipan: The Three M4 Sherman Tanks That Never Reached the Beach. In Underwater Archaeology of a Pacific Battlefield; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Japanese Short-Barrelled 12cm and 20cm Dual Purpose Naval Guns. Their Technical Details, War-Time Distribution and Surviving Examples; Institute for Land Water and Society, Charles Sturt University: Albury, Australia, 2017; Volume 104. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R.; Clemens, J. Silent Sentinels. The Japanese Guns of the Kiska WWII Battlefield; US National Park Service Alaska Regional Office: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T. Managing an Australian midget: The imperial Japanese navy type a submarine ‘M24’ at Sydney. J. Australas. Inst. Marit. Archaeol. 2008, 32, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, P.A. Shipwrecks of Truk, 2nd ed.; P.A. Rosenberg: Holualoa, HI, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, K. Hailstorm Over Truk Lagoon: Operations Against Truk by Carrier Task Force 58, 17 and 18 February 1944, and the Shipwrecks of World War II; Wipf and Stock Publishers: Eugene, OR, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann, K.P. Desecrate 1: Operations Against Palau by Carrier Task Force 58, 30 and 31 March 1944, and the Shipwrecks of World War II; Pacific Press: Belleville, ON, Canada, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Oxley, I. Scapa Flow and the protection and management of Scotland’s historic military shipwrecks. Antiquity 2002, 76, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Naval heritage of Project Apollo: A case of losses. J. Marit. Res. 2005, 7, 170–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglo-German Naval Agreement. [An exchange of notes]. Note from the UK Secretary of State [Sir Samuel Hoare] for Foreign Affairs to the German Ambassador [Joachim von Ribbentrop], London 18 June 1935.—Note from the German Ambassador, London, to the UK Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, London 18 June 1935. Leag. Nations Treaty Ser. 1935, 161, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Managing the Heritage of Arms Limitation Treaties. Int. J. Hist. Archaeol. in press. [CrossRef]

- Parker, M. The Heritage of Sound in The Built Environment: An Exploration. Bachelor’s thesis, Charles Sturt University, Albury, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R.; Parker, M. Hitting the ‘Pause’ Button: What does COVID tell us about the future of heritage sounds? Noise Mapp. 2020, 7, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization. Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972 (COLREGs); International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 1972; Volume 35. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, S.J. For whom the ship’s bell tolls. Legion. 15 May 2019. Available online: https://legionmagazine.com/en/2019/05/for-whom-the-ships-bell-tolls/ (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Elson, A. Sound and Its Uses. Musical Q. 1918, 4, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, A. Lost Sounds: The Story of Coast Fog Signals; Whittles Publishing: Caithness, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- RAN. HMAS Perth (I). Available online: http://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-perth-i (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- BBC. USS Osprey ship’s bell to be handed to US after mysterious return. BBC News, 3 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Antiques Navigator. Antique 16 Solid Bronze Ships Bell WWII U.S. Navy USS Rail Pearl Harbor Ship. Available online: https://www.antiquesnavigator.com/d-746877/antique-16-solid-bronze-ships-bell-wwii-us-navy-uss-rail-pearl-harbor-ship.html (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Cowan’s Auctions. U.S.S. Woyot Brass Ship’s Bell. Available online: https://www.lotsearch.net/lot/u-s-s-woyot-brass-ships-bell-41842128?searchID=1468297 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Grządziel, A. Using Remote Sensing Data to Identify Large Bottom Objects: The Case of World War II Shipwreck of General von Steuben. Geosciences 2020, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Openshaw, M.; Openshaw, S. Problems in Correctly Identifying a Shipwreck. Mar. Mirror 2013, 99, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, B. The future of Chuuk Lagoon’s submerged WW II sites. J. Australas. Inst. Marit. Archaeol. 2012, 36, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Gambin, T.; Licari, J. A Bell Saved! Tessarae Herit. Malta Bull. 2029, 8, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, D. Shipwreck Diving: A Complete Diver’s Handbook to Mastering the Skills of Wreck Diving; Aqua Explorers Inc.: East Rockaway, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Edney, J. A framework for managing diver impacts on historic shipwrecks. J. Marit. Archaeol. 2016, 11, 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, D.A. A Ship for the Taking: The Wreck of the Brisbane as a Case Study; Charles Darwin University: Darwin, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Edney, J. A review of recreational wreck diver training programmes in Australia. J. Australas. Inst. Marit. Archaeol. 2011, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, J. An Amnesty Assessed. Human Impact on Shipwreck Sites: The Australian Case. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 2009, 38, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaoru, Y.; Hoagland, P. The value of historic shipwrecks: Conflicts and management. Coast. Manag. 1994, 22, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N. Naval shipwrecks in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 3rd Asia-Pacific Regional Conference on Underwater Cultural Heritage, Hong Kong, China, 27 November–2 December 2017; Fahy, B., Tripati, S., Walker-Vadillo, V., Jeffery, B., Kimura, J., Eds.; Volume 2, pp. 1152–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Hiery, H.J. The Neglected War. The German South Pacific and the Influence of World War I; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schencking, C. Bureaucratic Politics, Military Budgets, and Japan’s Southern Advance: The Imperial Navy’s Seizure of German Micronesia in World War I. War Hist. 1998, 5, 308–326. [Google Scholar]

- Treaty of Versailles. Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Germany. Signed at Versailles 28 June 1919. Available online: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2579181373/view?partId=nla.obj-2579475611#page/n0/mode/1up (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Buckley, T.H. The United States and the Washington Conference; University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville, TN, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Van Meter, R.H. The Washington Conference of 1921–1922. A New Look. Pac. Hist. Rev. 1977, 46, 603–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.E.; Cabot Lodge, H.; Underwood, O.W.; Root, E. Conference on the Limitation of Armament. Am. J. Int. Law 1922, 16, 159–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.G. The “Yardstick” and Naval Disarmament in the 1920’s. Miss. Val. Hist. Rev. 1958, 45, 441–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, J.C. The Drafting of the Four-Power Treaty of the Washington Conference. J. Mod. Hist. 1953, 25, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington Arms Limitation Treaty. Treaty between the United States of America, the British Empire, France, Italy, and Japan, Signed at Washington, February 6, 1922. In Proceedings of the Conference on the Limitation of Armament, Washington, DC, USA, 12 November 1921–6 February 1922; League of Nations Treaty Series. Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. British Naval Guns in Micronesia. Mar. Mirror 1995, 81, 343–347. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Present and Future Management of the Japanese Guns on Kiska Island, Aleutians, Alaska. The 4.7-Inch Battery on North Head, Kiska Island. Documentation and Condition Report. Study prepared for the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Alaska; Heritage Futures Australia: Shepparton, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Present and Future Management of the Japanese Guns on Kiska Island, Aleutians, Alaska. The 6-Inch Gun Battery on Little Kiska Island. Documentation and Condition Report. Study prepared for the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Alaska; Heritage Futures Australia: Shepparton, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Present and Future Management of the Japanese Guns on Kiska Island, Aleutians, Alaska. The 6-Inch Gun Battery on North Head, Kiska Island. Documentation and Condition Report. Study prepared for the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Alaska; Heritage Futures Australia: Shepparton, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pate, M. The Naval Artificer’s Manual. (The Naval Artificer’s Hand-Book Revised) Text, Questions and General Information for Deck Artificers in the United States Navy; The United States Naval Institute: Annapolis, MD, USA, 1918; 797p. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Construction and Repair. Specifications for Building Twin-Screw Armored Battle Ship Connecticut, No. 18, for the United States Navy, Including Specifications for Equipment, and Specifications for the Installation of Ordnance and Ordnance Outfit; Bureau of Construction and Repair, Navy Department, United States: Washington, DC, USA, 1902.

- Bureau of Construction and Repair. Specifications for Building Twin-Screw Armored Cruiser Washington, No. 11, for the United States Navy, Including Specifications for Equipment, and Specifications for the Installation of Ordnance and Ordnance Outfit; Bureau of Construction and Repair, Navy Department, United States: Washington, DC, USA, 1902.

- Brodnax, J. Spreadsheet of Entries in Troy Meneely Ledger Book (Transcribed and Augmented). 2008. Available online: https://hudsonmohawkgateway.org/the-meneely-bells (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Ward, M.A. The Bell of USS Georgia (BB-15); Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Army ROTC, Georgia Institute of Technology: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, C. The Bell of USS New Jersey; Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Office of Public Information, City of Elizabeth: Elizabeth, NJ, USA, 2020.

- Halvorson, M.J. The Bell of USS North Dakota (BB-29); Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Battleship Texas Foundation: Bismarck, ND, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkman, L. The Bell of USS Rhode Island; Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; RI Department of State: Providence, RI, USA, 2020.

- Pope, C. USS South Carolina (Navy Ship Bell); Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Public Works, City of Florence: Florence, SC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zeilenga, J. The Bell of USS Vermont; Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Vermont State Curator’s Office: Montpelier, VT, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Heaney, J. Artifacts. Mont. Mag. Univ. Mont. 2013. Available online: https://archive.umt.edu/montanan/s13/Artifacts.php (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Booker, T.W. The Bell of USS North Carolina (ACR-12); Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Battleship North Carolina Inc.: Wilmington, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eckle, C. The Bell of USS Ohio; Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Ohio History Connection: Columbus, OH, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo, K. The Bell of USS Texas (BB-35); Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Battleship Texas Foundation: Houston, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell, J. [Unit History] ACR-8 USS Maryland/USS Frederick. Available online: http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~cacunithistories/military/USS_Maryland_Frederick.htm (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- McShane Bell Foundry. The McShane Bell Foundry: Henry McShane Manufacturing Co., Proprietors, Baltimore, MD., U.S.A., Manufacturers of Chimes and Peals and Bells of All Sizes for Churches, Fire Alarms, Court House, Tower Clocks, &c., &c., Mounted in the Most Approved Manner and Fully Warranted; McShane Bell Foundry: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Meneely Bell Co. Church Bells, Peals and Church Bell Chimes: Also Bells for All Known Uses, Which are Composed of the Highest Grade of Genuine Copper and Tin Bell-Metal; Meneely Bell Co.: Troy, NY, USA, 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert, W.A.; Sharp, D.B.; Taherzadeh, S.; Perrin, R. Partial frequencies and Chladni’s law in church bells. Open J. Acoust. 2014, 4, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Audy, J.; Audy, K. Analysis of bell materials: Tin bronzes. Overseas Foundry 2009, 5, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- USLS. Light Station Detail Report. Fog Signal—Bell Signal—Manufacturer. Available online: https://uslhs.org/inventory/bell_signal_detail.php?idx=6&type=station (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- USLS. Light Station Detail Report. Fog Signal—Bell Signal—Weight. Available online: https://uslhs.org/inventory/bell_signal_detail.php?idx=1&type=station (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Anonymous. Louisiana in Commission. The Sun (New York), 3 June 1906; 6. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Congress House Committee on Naval Affairs. Work on U.S.S. Louisiana. Congressional Document; U.S. Congress House Committee on Naval Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 1907.

- Gillig, J.S. The Predreadnought Battleship USS Kentucky. Regist. Ky. Hist. Soc. 1990, 88, 45–81. [Google Scholar]

- Handy, M. The Official Directory of the World’s Columbian Exposition, May 1 to October 23rd, 1893. A Reference Book of Exhibitors and Exhibits; of the Officers and Members of the World’s Columbian Commission, the World’s Columbian Exposition and the Board of Lady Managers; a Complete History of the Exposition. Together with Accurate Descriptions of All State, Territorial, Foreign, Departmental and Other Buildings and Exhibits, and General Information Concerning the Fair; W. B. Gonkey Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R. Ring in the New Year at Navy Pier with a Bell from The White City. Chicago Now. 2013. Available online: http://www.chicagonow.com/chicago-history-cop/2013/12/ring-in-the-new-year-at-navy-pier-with-a-bell-from-the-white-city/ (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- American Legion. USS Chicago Bell Memorial. Available online: https://www.legion.org/memorials/238181/uss-chicago-bell-memorial (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Krafft, H.F. Catalogue of Historic Objects at the United States Naval Academy; United States Naval Instutute: Annapolis, MD, USA, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- NHHC. Ship’s Bell USS Prinz Eugen (IX-300). Available online: https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/artifacts/ship-and-shore/ShipsBells/ship-s-bell-uss-prinz-eugen--ix-300-.html (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Anonymous. The Connecticut in commission. New-York Tribune, 30 September 1906; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Big battleship Connecticut is ocean’s bride. The Washington Times, 29 September 1904; 1. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Navy. Navy Property Redistribution and Disposal Regulation n° 1; Department of the Navy: Washington, DC, USA, 1949.

- U.S. Navy. General Policy for the Inactivation, Retirement, and Disposition of U.S. Naval Vessels; Department of the Navy: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- U.S. Office of Naval Operations. General Instructions for Reserve Fleets; U.S. Office of Naval Operations, U.S. Navy: Washington, DC, USA, 1964.

- U.S. Navy. Navy Property Redistribution and Disposal Regulation n° 1; Department of the Navy: Washington, DC, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Navy. General Policy for the Inactivation, Retirement, and Disposition of U.S. Naval Vessels; Department of the Navy: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- NHHC. Ships’ Bells. Available online: https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/b/bells-on-ships.html (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Pallas, W.J. The Doctrine of State Succession and the Law of Historic Shipwrecks, The Bell of the Alabama: United States v. Steinmetz. Tulane Marit. Law J. 1992, 17, 343–352. [Google Scholar]

- Ivan, W. USS Osprey II (AM-56) [+1944] [Michelle Mary Fishing & Diving Charters]. Available online: https://wrecksite.eu/imgBrowser.aspx?5522 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Jacobs, J.H. Much of What to Know about U.S. Navy Bells. Available online: http://landandseacollection.com/id1189.html (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- JWH1975. Scrapping the Warships of WWII. Available online: https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2020/09/07/scrapping-the-warships-of-wwii/ (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Zhou, Z. The Bell of the US Retired Aircraft Carrier Sounds on Campus. Available online: https://tw.appledaily.com/life/20170630/7RYCI7T7YB5JROIHEFIWANFNPM/ (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Underwood, A. Ding! Ding! History and Heritage Blog on Ships’ Bells, Arriving! In The Sextant; Naval History and Heritage Command: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Volume 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.F. The Whereabouts of the Bells of the Ships Scrapped as Part of Washington Arms Limitations Treaty of 1922; Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Curator Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, I. Ding dong, the old student union’s dead. Ariz. Wildcat Mag. (online). 2000. Available online: https://wc.arizona.edu/papers/94/74/01_4_m.html (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Williamson, R. Salvaged Bell to Ring again. Ariz. Wildcat Mag. (online). 2002. Available online: https://wc.arizona.edu/papers/96/4/01_4.html (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Quinlan, M. The Bell of USS Connecticut; Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Mystic Seaport Museum: Mystic, CT, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Delaware in World War I Exhibit Opens at Archives in Dover. Cape Gaz. 2017. Available online: https://www.capegazette.com/article/delaware-world-war-i-exhibit-opens-archives-dover/146949 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Lee, C.U.S., Jr. Battleship Georgia. Description and trials. J. Am. Soc. Nav. Eng. 1906, 18, 802–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Naval 6 Inch 50 Caliber Gun—ROTC, Georgia Tech: Atlanta, GA, USA. Available online: https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/wm5MPD_Naval_6_Inch_50_Caliber_Gun_ROTC_Georgia_Tech_Atlanta_GA (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Hall, R.T. U.S.S. Minnesota. J. Am. Soc. Nav. Eng. 1906, 18, 1143–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. USS Minnesota (BB22). Available online: https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=91371 (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- O’Neil, T. Fair Fire. A Look Back Marines Save the Bell as the Missouri Building Burns during 1904 World’s Fair; St. Louis Post-Dispatch: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt, W.A., Jr. U.S.S. New Hampshire. J. Am. Soc. Nav. Eng. 1908, 20, 273–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, C. Warship Wednesday July 15, 2015: The Great War’s Granite State. Available online: https://laststandonzombieisland.com/2015/07/15/warship-wednesday-july-15-2015-the-great-wars-granite-state/ (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Anonymous. U.S. Battleship New Jersey. J. Am. Soc. Nav. Eng. 1906, 18, 845–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerseyman. United States Navy Ship’s Bells. A Naval Heritage Tribute. Battleships. USS New Jersey (BB-16). Jerseyman 2006. p. 22. Available online: https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-navy-ships/battleships/new-jersey-bb-16.html (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Yasuhara, N. The Bell of USS Oregon; Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Oregon Historical Society: Portland, OR, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- RIDS. Rhode Island State House Online Tour. Second Floor. The Battleship Bell. Available online: https://www.sos.ri.gov/divisions/Civics-And-Education/ri-state-house/online-tour/second-floor (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Edwards, C.B.; Lovell, R.L. U.S. Battleship Rhode Island. J. Am. Soc. Nav. Eng. 1906, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B. Florence Veterans Park. Available online: https://www.scpictureproject.org/florence-county/florence-veterans-park.html (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Yarnall, P.R. BB-20 USS Vermont. Available online: https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-navy-ships/battleships/vermont-bb-20.html (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Anonymous. U.S.S. Vermont. Description and official trial. J. Am. Soc. Nav. Eng. 1907, 19, 159–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHHC. USS Virginia Bell. Available online: https://www.dvidshub.net/image/5014810/uss-virginia-bell (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Anonymous. The Great War. Illus. War News 1917. pp. 2–4. Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/18334/18334-h/18334-h.htm (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Royal Museums Greenwich. Ship’s Bell [HMS Valiant]. Available online: https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/18088.html (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Colledge, J.J.; Warlow, B. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of All Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy; rev. ed.; Chatham Publishing: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Navy, Military and Air Force Ships’ Bells for Sale. The Times (London), 19 September 1931; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Royal Navy. Sale of Ships’ Bells. The Times (London), 17 December 1938; 19. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Cracks that tell tales. 24 Ship’s Bells to be sold. Famous relics. Derby Daily Telegraph, 8 November 1929; 10. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Historic Ship’s Bells. Relics of famous battles. Offered for sale. Dented and cracked instruments. 1929; unprovenanced newspaper clipping. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, E. Where do Ship’s Bells go? The Ringing World, 10 August 1956; 508. [Google Scholar]

- Buswell, A.A.J. Ship’s Bells. The Ringing World, 11 December 1959; 744. [Google Scholar]

- Admiralty. Admiralty Fleet Order 1234/28 1928. Available online: https://www.navy.gov.au/media-room/publications/admiralty-fleet-orders/1910-1937 (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Anonymous. Royal Navy. Ships’ Bells for Sale. The Times (London), 18 April 1934; 4. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Warships’ Bells: Surplus war relics to be sold. The Times (London), 31 May 1928; 11. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R.A. British Battleships of World War One: New Revised Edition; Naval Institute Press: Anapolis, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Navy. The Ship’s Bell from the Great War battleship HMS Valiant. In Royal Navy Facebook Page; Navy, R., Ed.; Royal Navy: London, UK, 2014; Volume 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Imperial War Memorial. Accessory, Ship’s Bell (HMS Tiger), British. Available online: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30003983 (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Worthpoint. HMS Tiger Ship’s Bell Jutland 1916. Available online: https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/hms-tiger-ships-bell-jutland-1916-454418883 (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Barnebys. Brass Ships Bell. From HMS Tiger a Battle Cruiser of the Royal Navy. Available online: https://www.barnebys.com/auctions/lot/brass-ships-bell-from-hms-tiger-a-battle-cruiser-of-the-roy-szp3caudmo2 (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Bonhams. World War I: The Battle of Jutland. A Ships Bell Cast Using Brass from the HMS Tiger. British: C. 1917. Available online: https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/26461/lot/2/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Superb Association. The, H.M.S. Superb (Cruiser) Association. Available online: https://roy935.wixsite.com/hms-superb/before-1943-photo-album (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Southwell, R. The Bell of HM Superb; Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; e-mail ed.; Upton Lovell, UK; Wilts, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Museum of the Royal New Zealand Navy. HMS New Zealand’s Ship’s Bell. Available online: https://navymuseum.co.nz/explore/by-collections/ship-items/hms-new-zealands-ships-bell/ (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Anonymous. HMS New Zealand. The Colony’s Presentation. New Zealand Herald, 6 May 1905; 6. [Google Scholar]

- TBNM. HMS New Zealand’s Ship’s Bell. Available online: https://navymuseum.co.nz/explore/by-collections/ship-items/hms-new-zealands-ships-bell/ (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Royal Australian Navy. HMAS Australia (I). Available online: https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-australia-i (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Anonymous. General News. The Age (Melbourne, Vic.), 12 April 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Striking the bell. The Sun (Sydney, NSW), 11 November 1926; 13. [Google Scholar]

- AWM. Ship’s Bell: HMAS Australia (I) [RELAWM04469]. Available online: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C110606 (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Australian War Memorial. Ship’s Bell: HMAS Parramatta (1910–1928). Available online: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C110656 (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Royal Australian Navy. HMAS Sydney (I) Part 2. Available online: https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-sydney-i-part-2 (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Royal Australian Navy. HMAS Sydney (I). Available online: https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-sydney-i (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Royal Australian Navy. HMAS Parramatta (I). Available online: https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-parramatta-i (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Australian War Memorial. Ship’s Bell: HMAS Huon (1915–1928). Available online: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C110657 (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Australian War Memorial. Ship’s Bell: HMAS Swan (1915–1928). Available online: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C110658 (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Royal Australian Navy. HMAS Swan (I). Available online: https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-swan-i (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Royal Australian Navy. HMAS Huon (I). Available online: https://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-huon-i (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Jane, F.T. The Imperial Japanese Navy; Thacker: London, UK, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Jentschura, H.; Jung, D.; Michel, P. Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy 1869–1945; Arms & Armour Press: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Stille, M. Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carriers 1921–1945; Osprey Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sydney Morning Herald. Togo’s Flagship. Sydney Morning Herald, 19 July 1922; 11. [Google Scholar]

- Sydney Morning Herald. A War relic. Admiral Togo’s Flagship. Japan’s desire for preservation. Sydney Morning Herald, 19 March 1924; 13. [Google Scholar]

- Australian War Memorial. Ship’s Wheel from HIJMS ‘Ibuki’ (RELAWM08238). Available online: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C110619 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Australian War Memorial. Model Ship: HIJMS ‘Ibuki’ (RELAWM08039). Available online: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C111976 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Bullard, S. A Model Gift. Wartime 2008. pp. 28–31. Available online: https://www.awm.gov.au/wartime (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Swinden, G. White Ensign, Rising Sun: Australian-Japanese Naval Relations during World War I. Signals 2018. pp. 40–44. Available online: https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=037532508930601;res=E-LIBRARY (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Peek, J. Ibuki Bell; Spennemann, D.H.R., Ed.; Australian War Memorial: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- hawk26. Visit to the Battleship “Mikasa”: Togo Heihachiro’s Bedroom is Decorated with Exquisite Decoration, and It Is a Nobleman Style. Available online: https://new.qq.com/omn/20190824/20190824A0AY6C00.html (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- sutanisurao_0323. [Battleship Asahi Ship’s Bell, Imperial Japanese Navy 1904] Auction Yahoo Japan 31 October–5 November 2020. Available online: https://page.auctions.yahoo.co.jp/jp/auction/b512623191 (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- 1stdibs. Japanese Fine Bronze Ships Bell with Fine Patina, Bold Sound & Signed [LU1289214118411]. Available online: https://www.1stdibs.com/furniture/building-garden/garden-furniture/ja…-fine-bronze-ships-bell-fine-patina-bold-sound-signed/id-f_14118411/ (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Corbett, J.S. Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905; Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, MD, USA, 1994; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ichioka, T. The Russo-Japanese War: Naval, By Permission of the Naval Department; Kazumasa Ogawa: Tokyo, Japan, 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, B.; Kingsepp, S. IJN Repair Ship ASAHI Tabular Record of Movement. Available online: http://www.combinedfleet.com/Asahi_t.htm (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Anonymous. Indiana’s Gift to the Battleship Indiana; Carlon & Hollenbeck, Printers: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1896. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, R. The Eclipse of the Big Gun: The Warship, 1906–1945. In Conway’s History of the Ship; Conway Maritime Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, A. HMS Dreadnought (1906)—A Naval Revolution Misinterpreted or Mishandled? The Northern Mariner/le Marin du Nord 2010, 20, 175–198. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. [Visit to the Battleship “Mikasa”: Togo Heihachiro’s Bedroom is Decorated in an Exquisitely Elegant Style]. Available online: http://www.ifuun.com/a2019082420434947/ (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Lovell, T. Dreadnought Project, Personal communication, e-mail to Dirk H.R. Spennemann, dated Nov 26, 2020.Stille, M. In Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carriers 1921–1945; Osprey Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Museums Greenwich. Unofficial Gun Tompion of HMS Dreadnought. 1906. Available online: https://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/1696.html (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- IC3D Printers. Replica Bell of USS New Jersey. Available online: https://twitter.com/ic3d_printers/status/1195443236426440705 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Australian War Memorial. Ship’s Bell from SMS Emden. Available online: https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C158710?image=1 (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Imperial War Memorial. Accessory, Ship’s Bell (SMS Emden 1916), German. Available online: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30004080 (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Marsden, A. Steam Pinnace No 48. Steam Pinnace Newsletter 2020. pp. 1–4. Available online: https://www.navy.gov.au/ (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Comegno, C. U.S. Navy returns silver service to Battleship NJ. The Tennessean, 26 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- NDHC. Exhibits-Hall of Honor. Available online: https://statemuseum.nd.gov/exhibits/hall-honors (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Governor’s Mansion Commission. State Dining Room. South Carolina Governor’s Mansion. Available online: https://www.scgovernorsmansion.org/mansion/?nav=map&show=33 (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Committee on Naval Affairs. Disposition of Silver Service of U.S.S. Louisiana; Report to Accompany H.R. 13404 submitted by Mr Broussard Jan 7, 1929; Senate Committee on Naval Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 1929.

- Australia ICOMOS. The Burra Charter. The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance 2013; Australia ICOMOS Inc., International Council of Monuments and Sites: Burwood, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Heritage Office. Assessing Heritage Significance; NSW Heritage Office: Sydney, Australia, 2001; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, M. Museums and restorative justice: Heritage, repatriation and cultural education. Mus. Int. 2009, 61, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, N. Decolonising Artefacts at the British Museum: Decolonising Heritage: Border Thinking, Border Practices. In Proceedings of the association of Critical Heritage Annual Conference, Hangzhou, China, 1–6 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garsha, J.J. Expanding Vergangenheitsbewältigung? German Repatriation of Colonial Artefacts and Human Remains. J. Genocide Res. 2020, 22, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | There are a number of other items that may carry the name of the vessel, such as bands for sailor’s hats carrying the name of the vessel or mess items where the vessel’s name is shown on the décor or engraved on utility as well as decorative tableware. Examples of the latter are listed in Table 9. These are items that constitute part of the moveable cultural heritage associated with a vessel. They do not exist for every vessel and are in a “lesser league” than builder’s plates and ships’ bells. Builder’s plates carry the hull constriction number and represent the formal registration of the vessel, whereas the ship’s bell is the sole item that is associated with the operational history of the vessel, from commissioning to decommissioning. |

| 2 | Among the other vessels depicted is the Great Lakes steamer SS Huronic, launched in 1901 by the Collingwood Shipbuilding Company (Collingwood, Canada). |

| 3 | It needs to be noted that the bell typology advanced in this paper is purely based on visual physical characteristics. The bell profile, and in particular the thickness of the sound bow, has direct effects on the pitch [77]. As shown by Audy & Audy, the nature and admixture rates of the alloys used for bell casting, as well as the purity of the raw metals used for the alloys, will influence the hardness of the bell metal and thus also affect the sound the bell gives [78]. None of the acoustic signatures of the bells examined here were assessed. |

| 4 | Also melted down were the bells of USS Indiana (BB-1) (commissioned 1895, decommissioned 1919); USS Massachusetts (BB-2) (commissioned 1896, decommissioned 1919); USS Alabama (BB-8) (commissioned 1900, decommissioned 1920). |

| 5 | At one point on display in the visitor information area of the Amtrak station Mystic, on loan from Mystic Seaport. |

| 6 | The clapper was removed and is stored separately [66]. |

| 7 | Bell is in the inventory of the Oregon Historical Society in Portland but has not been seen since 1959 [118]. |

| 8 | It would appear that in some instances a bell was removed upon decommissioning, but not reissued to the vessel when it was recommissioned under its original name. A case in point is the C-class light cruiser HMS Canterbury, which spent much of her service career in and out of fleet reserve. She was originally commissioned in April or May 1916, decommissioned in 1922, recommissioned in May 1924, decommissioned in about June 1925, recommissioned in November 1926, decommissioned in March 1931, recommissioned in about August 1932, and decommissioned for the last time in December 1933 and then sold for scrap in July 1934 [126]. Even though her final commission ran from August 1932 to December 1933, one of her bells was for public sale in September 1931 [127]. |

| 9 | If Japanese bells carry inscriptions, they tend to have been added after casting with a punch, essentially writing the Kanji characters stroke by stroke. See also: A Japanese ship’s type bell (30 cm tall, 20 cm diameter, unspecified weight) with an engraved inscription 大正十三年度 卒業記念 (Taisho 13 (or the year 1924), graduation commemoration) [171]. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).