Abstract

The theme of the conference regards images. Since the theme is so vast, I have handled it by dedicating to it some basic general reflections. Therefore, I maintain that the best choice is to evoke the aphorism in the epigraph: I propose a series of fragmented memories or annotations taken while reading and looking at images, or even citations.

1. Introduction

The true sense of the aphorism in critical theory is precisely this: writing with urgency, starting from a concrete figure, throwing flashes of theory here and there with the awareness that one cannot do better. (Stefano Petrucciani).

The theme of the conference regards images.

Since the theme is so vast, I have handled it by dedicating to it some basic general reflections. Therefore, I maintain that the best choice is to evoke the aphorism in the epigraph: I propose a series of fragmented memories or annotations taken while reading and looking at images, or even citations, although I am often guilty of lacking the author’s name. I offer “flashes of theory” proposed in concurring or even contradictory sequences, “without chronological or narrative order, but with the coherence of a detonation moving along the entirely Proustian thread of a memory that proceeds through figurative madeleines”, as Gianni Canova would say (see below).

These are notes, therefore, that try to trace a border around my main interest and a line within, which is perhaps discontinuous and contorted where it intersects materials and essential techniques.

My interest is overtly for the formed image: the one intentionally given a form with aesthetic goals (which in many experiences in modern art can also be “unformed”, as Rosalind Krauss has demonstrated).

Having said this explicitly, another preliminary caution is important. As the writer of the Italian Wikipedia page states, the image in a literally rigorous sense is a “visual, non-solid representation”. As clarified then in a footnote, “the image is not the physical support on which it can be fixed or visualized. It is the visual information fixed or visualized upon the support”. This affirmation—increasingly valid today in the digital age—seems to suggest the essential conceptual nature of the techniques used to produce actual images, that is, an inventive search for meaningful ways and procedures that are mostly virtual.

On the other hand, throughout history, the image was inseparably fixed in works with a physical substance, even if it was sometimes only represented allusively. Beyond those preceding the pure conceptualization of an appearance, it also refers to other techniques—material production to use Kandinsky’s term—of the artificial references of the images, production as the fruit of knowledge and ancient traditions or very modern experimentation.

But in this age of transition, the subsistence/coexistence within images of both types of techniques does not constitute an insoluble conflicting condition. Better yet, on the one hand, it reconfirms both their specific cognitive value—that is, not only descriptive/illustrative—and the mandatory need for systematic experimentation with them (as an unavoidable need to verify the law of facts). On the other hand, it finally pushes towards the desired start of systematic investigation of the means from which the work of art is born, setting aside both the spiritual abstractions of romantic aesthetics and the likewise abstract institutionalism of superperforming advantages of the digital medium.

All of this is initially oriented towards a reflection on the possibility/opportunity for a linguistic structure of the systems of formed visual images, beginning with an attempt to indicate their possible grammatical foundation.

All of what follows is basically notes that intersect with the various techniques, to be collected and developed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Picture of the author visiting In Orbit—2017 tempoarary exhibit of Tomás Saraceno in Standenhaus, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf.

2. On Images and Imagination

- “We make pictures of the world for ourselves”, Ludwig Wittgenstein said in his Tractatus. Today’s technoscience has only increased the capacity of scientists to work with images and representations.

- Various types of images can be classified: the image as a picture (figure on supporting material), the mental or representational image, the dreamlike and mnemic image, the image as a figured trope of language, the image as an object of individual and collective imagination and unconscious; from A. Pinotti and A. Somaini, Cultura visuale, Einaudi, Turin, 2016.

- Like memory, imagination does not only sanctions the step from the sensible to the intelligible, from physis to all its opposite extremes (logos, techné, nomos, etc.) but is specified in a nature and a culture that it has made possible on its own. (Maurizio Ferraris)

- Seeing oneself. Seeing is not a neutral or naïve act separable from the person who sees or is seen. With regard to The Anatomy Lesson by Rembrandt in Amsterdam, Valery loved to say that the eye is the most spiritual of the senses. Words, like an image, a reflection, a representation, converge on the ophthalmic scene. The eye is the inevitable organ both of knowledge and its distortion. All that pertains to the experience of looking is a mental refraction of matter …. The maximum of reality and the maximum of theatricality come into contact with artifice, reflex, interference on reality, of reality, with reality. The viewpoint is to be used as a great metaphor, only by knowing itself to be unknown to itself without certainty or identity, is it possible, can one try to reposition oneself as objects of the world. (Magrelli).

3. Notes on the Techniques of Invention

- Repetition is impartial and a null sum of variations and unaltered identities.

- “Repetition is recollection carried forward”. (Kierkegaard)

- Editing: composing what is simultaneous into a sequence, connecting what is iconic to what is discursive.

- Metre is a measure and ordering value. The measure fixes a value as an opportune limit, but gives a hint of the sense of limitlessness, of what lies beyond.

- Every work in some phase of its development acquires its own “normativeness”, becoming a model of “rule-making creativeness”.

4. Notes on the Techniques of Inventing the disegno and Some Expressive Methods

- Manual disegno [1] is one of the oldest means of experience and human knowledge, certainly predating writing and history. Its “effective, subtle artisanship” recalls the myth of Daedalus, whose work expressed creative fantasy and the community’s productive ability. Today the sense of community seems rather weak, yet like the disegno, it survives and does not disappear, even if we must accept that it changes. The “new pencil”, however, should allow and authorize the meaning of sentiments that we mistakenly claimed were stable to change freely, but not to reduce or delete them.

- The private worth of the disegno as a memorandum remains unaltered; looking at another’s disegno has always meant immersing oneself in a dimension separate from the mental field of its creator.

- To understand the aspect (and the value) of a disegno that was just made, one should imagine it as terrain whose superficial similarity highlights the stratification of its elaboration (and its sense). Immediately after observing its format and the approach with which it was set, it is first necessary to concentrate on analysing the visible surface (with the graphical techniques that produced it). Its consistency is given concretely by a “humus” of sensible phenomena—physical matter and manual practices to distinctively recognize and classify: shading and light, colouring and staining, collage and superposition of the most varied materials, dry and desiccated or, in contrast, viscous and thickened, disposed to “texturizing” larger or smaller fields or to mark the linear outlines of figures.

- Tracing the sign and the space together: the magical capacity of the design consists in fencing in the space but also the time, the “iconographic instant of the archetypical sign”, consigning it definitively to the present.

- Any invention disegno is also a self-portrait, or better yet, “the disegno is a double transfer: from reality to the author and then back to artificial reality” (Franco Purini).

- “Thought does not descend from the sky, nor does it bypass the head. It is, rather, the result of practice, of habits of externalization that retrospectively constitute our inner reality”, Maurizio Ferraris in Il Pensiero manuale in La Repubblica, 12 February 2017—(like the disegno. Author’s note).

- Cézanne says, “the instant the paint becomes a gesture, the painter thinks in paint”.

5. Notes on the Techniques of the Masters

- Vasari writes, “Giotto discovered, in part, something of the gradation and foreshortening of figures”.

- Michelangelo’s disegni grew not through layers of technical determination, but instead, according to him, as occurred for the form, which was nestled in the heart of the marble and awoken by “force of removal”, that is, by erosion and excavation far from any simple talent and by naturalistic mimesis, although so easy for him, but empty of sense and aimed at an arduous identity of their making.

- Raphael opened the 1500s with The Marriage of the Virgin [2].

- Wislawa Szymborska (Polish poet) states that Vermeer “is the painter of silence. Each of his paintings is painted silence”.

- According to Federico Zeri, Ingres was “the minister of the line”. His line is absolute.

- Rembrandt had, like few others, the ability to represent the glare of metals.

- John Constable (1776–1837) was one of the best landscape painters: the inventor of the modern landscape (the so-called “Constable Country”). To find a parallel it is necessary to think of the Provence of Cézanne and Van Gogh or the Île of Corot and Monet).

- Poussin defined his own position with respect to colour: he indicated, in fact, a sort of theory of the “methods” to be applied as a function of the “genre”.

- Delacroix: colour as a luminous mass that coagulates its own edges. Assembler les rêves (Assembling Dreams) is the title of Delacroix’s diary.

- The Lemon by Manet (1880) disavows the chromatic naturalism of Caravaggio.

6. Monet’s Turning Point

- “Gather the nature of the fact”, Monet said. For this it was not necessary to work more than two hours continuously. The effect of the luminous-chromatic condition for Monet lasted about 30 min and the goal of painting was to render the history of those 30 min.

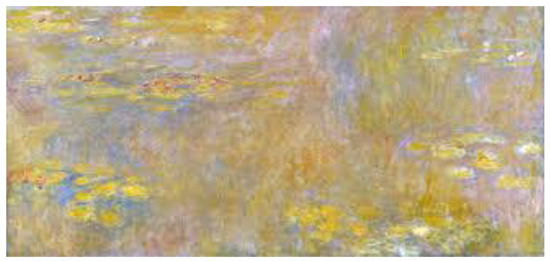

- It is probably with one of his famous water lilies, painted around 1907, that Monet abolished the horizon. He physically expels it above the “window”, which therefore ceases to be such; between observed reality and representation, the relationship that is instituted becomes completely different: a relationship of instantaneous correspondence, as Monet himself said many times about wanting to search and establish. (Figure 2 and Figure 3)

Figure 2. Claude Monet Ninfee, 1920, National Gallery, London.

Figure 2. Claude Monet Ninfee, 1920, National Gallery, London. Figure 3. Claude Monet Stagno di ninfee, 1915–1926, Chichu Art Museum, Naoshima, Kagawa.

Figure 3. Claude Monet Stagno di ninfee, 1915–1926, Chichu Art Museum, Naoshima, Kagawa.

7. Notes on the Modernism Masters

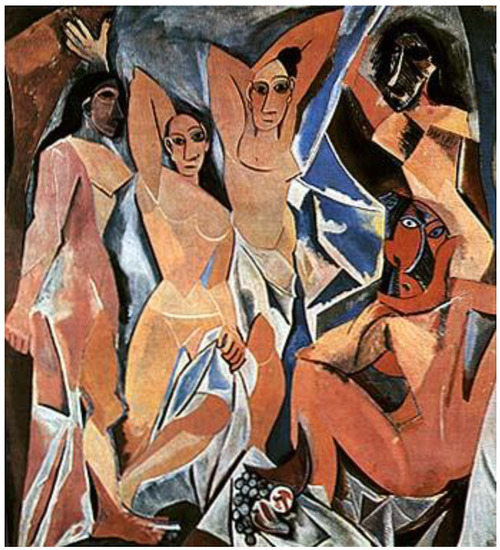

- Critical syntheses on the origin of painting in the 1900s “rest upon” a binary scheme of two complementary evolutionary lines: (a) the line from Fauvism to Divisionism and (b) the line from Cézanne to Cubism [3] (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Pablo Picasso, 1906–1907, Les demoiselles d’Avignon, MoMA, New York.

Figure 4. Pablo Picasso, 1906–1907, Les demoiselles d’Avignon, MoMA, New York. - “In nature everything is modelled according to three fundamental modes: the sphere, the cone, the cylinder. You must learn to paint these very simple figures, then you can do what you want”. (Cézanne)

- 1906 is the year of Les demoiselles d’Avignon, that is, the year when modern painting began [4].

- In 1913 Franz Marc, one of the promoters—with Kandinsky—of Der Blaue Reiter, painted and exhibited a painting called Blaue Fohlen [Blue Foals]. He was asked by a visitor when he had ever seen blue horses and he responded curtly with what could be considered one of the most blunt summaries of modern art: “I didn’t paint horses. I painted a painting”.

- “Here for the first time,” says Shklovsky, “iron is standing on its hind legs and seeking its artistic formula. In the age of construction cranes, as fine as the wisest Martian, iron has the right to go on a rampage … The monument is made of iron, glass, and revolution”.

- The modern painter no longer considers the image as a simple substitute for a sensible reality. The great painting tradition of the 1900s cannot be understood without also rediscovering the icon. The metaphysical world of a Malevic is the icon in an anti-icon sense. But also Mondrian. In Mondrian there is a search for the archetype. (The variations are variations on something identical.) These influences are very noticeable not only in theory but also in certain figurative choices: as Malevic said and as Mondrian would repeat, in the elimination of what is retinal, in a solely mental depiction, in the strong push towards intellectualization. It is a painting of pure intelligence where feeling counts for absolutely nothing: it is a revelation of archetypes, of geometrical figures. It is a revelation of reality in a platonic, not empirical, sense.

- Klee and German idealistic metaphysics, which embraced the romantic details of what was close and what was far away, close-up detail and a cosmic panorama.

- “Klee invented his pentagram—elegant and unstable—of forms and colours that are imposed to be an arpeggio always in a precarious balance between a steadfast calling for an encoded realism and the slow irresistible calling to be freed from any concrete fact”. (Cesare De Seta in an article probably in La Repubblica about a Klee exhibit in Bonn in some unknown year).

- For Klee, figurative is not the representation of the object, but the internal construction of the image (in this sense what is visible also has an abstract conception).

- Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs create problems in some perceptual certainties, due to which it is a “celibate machine”.

- For the abstract expressionists, the abysses of I represented the main element generating the work.

- Detournement, wandering through a labyrinth of random correspondences.

- The sculptural machines created by Jean Tinguely (the reference is the so-called kinetic painting).

- Magritte is a figurative painter of abstract thought.

- Marcel Duchamp, responding to a request from Tzara who invited him to participate in a show, said “I have nothing to exhibit—that the word exhibit is like the word marriage for me”.

8. Notes on Film Techniques

- “The close-up originated in the images of kings on coins”. (J. L. Godard)

- Perhaps histories (a history) today can only be done so. A history (of design? of cinema?), with all the other possible histories within … In the approach and the themes, but also in the supports and languages. Without any chronological or narrative order, but with the coherence of a detonation moving along the entirely Proustian thread of a memory that proceeds through figurative madeleines, twists around itself, opens illuminating flashes of inspiration, sinks into the darkness of black images and then re-emerges with surprising, always revealing combinations”. (Gianni Canova, Il cinema è una madeleine (Cinema is a Madeleine), in Alias No. 5, 30 January 1999).

- “I look for plasticity, especially the plasticity of the image, along a path which I can never forget, begun by Masaccio: his proud chiaroscuro, his black and white—or the path, if you like, of archaic painters, in a strange union of subtlety and crudeness. I can’t be an impressionist. I love the background, not the landscape”. (Pier Paolo Pasolini on Mamma Roma, Rizzoli, Milan, 1962).

9. Notes on Digital Techniques

- The digital age has defined a form of Taylorism in the decomposition of commonly synthetic cognitive activities into as many parcelled functions.

- Many contemporary digital images show a tendency for a figurative change. In the meantime, the precondition is merely quantitative order: because the figural intent, that is, the manifestation of a formative intention expressed through disegni or schemes, is increased significantly (and open to everyone) with digital design. Then, in a richer sense, because the potential transformability of the images—to which animation procedures, with their dynamic and chromatic variations, can also very easily be applied—has begun to go beyond the absolute visual determinism of static representation, towards possible continuous changes and manipulations.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

The Italian term Disegno was not deliberately translated into the entire article. | |

There was a double exhibit of this iconographic theme at the Accademia di Brera this year. | |

Before reaching the final version of Les demoiselles d’Avignon, Picasso created a large number of versions, reworking and transforming them, which would lead him to the known version. But not even that could be considered the true final version because what we see now is the last draft made by the artist, who at a certain point simply stopped working on it. | |

In its simplification, this scheme sets aside an important series of phenomena; e.g., the conquest of pure colour that would give rise to all of impressionism or the esotericism of Gauguin’s school or even symbolism, etc. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).