Abstract

For a complex parameter c outside the unit disk and an integer

, we examine the n-ary collinear fractal , defined as the attractor of the iterated function system

, where

. We investigate some topological features of the connectedness locus

defined as the set of those c for which

is connected. In particular, we provide a detailed answer to an open question posed by Calegari, Koch, and Walker in 2017. We also extend and refine the technique of the “covering property” by Solomyak and Xu to any

. We use it to show that a nontrivial portion of

is regular closed. When

, we enhance this result by showing that in fact, the whole

lies within the closure of its interior, thus proving that the generalized Bandt’s conjecture is true.

Keywords:

collinear fractals; Bandt’s conjecture; connectedness locus; iterated function systems; Mandelbrot set; roots of integer polynomials MSC:

28A80; 28A78; 37F45; 11R06; 26C10

1. Introduction

Polynomials with integer coefficients are fundamental objects in mathematics, serving as building blocks in various areas such as algebra, number theory, and geometry. The roots of these polynomials often exhibit fascinating and intricate patterns in the complex plane. In this paper, we uncover a deep connection between these roots and a class of self-similar sets that we call collinear fractals. These fractals are generated by repeatedly applying simple mathematical transformations involving a complex parameter c and an integer n. Exotic elements of the family include some self-affine tiles with a collinear digit set independently studied in [1]. Remarkably, the set

of parameters c for which the corresponding fractal is connected can be identified with the set of roots of polynomials with integer coefficients restricted from

to

. By exploring this bridge between algebra and geometry, we provide new insights into long-standing mathematical questions, demonstrating how the algebraic properties of polynomials shape the geometric structure of fractals and give rise to complex and beautiful sets.

The concept of visualizing roots of polynomials is not new, and numerous mathematical explorations have arisen from this idea, particularly in blogs and online mathematical discussions [2,3]. Research on the so-called Littlewood polynomials, whose coefficients are

, produced some of the earliest

-like imagery; see, for instance, the work of Peter and Jonathan Borwein [4,5]. Similarly, polynomials with coefficients restricted to

, known as Newman polynomials, were thoroughly investigated in the seminal work of Odlyzko and Poonen [6]. Other studies related to roots of polynomials include the Thurston’s Master Teapot [7,8,9], Algebraic Number Starscapes [10,11], and the eigenvalues of Bohemian Matrices [12].

For any integer

, let

be the set

Let

denote the closed unit disk. For any parameter

, consider the iterated function system (IFS)

, where

. The attractor

of this IFS is the unique nonempty compact set satisfying

These sets

, which we refer to as collinear fractals, are fundamental examples of self-similar sets in the plane, and understanding their topological and fractal properties is of significant interest. For a geometric description of

, label the n first-level pieces of

as

For odd n values, the central piece is

, which is a copy of

centered at 0, scaled down by

and rotated by

. The neighboring pieces of

are

and

. For even n values,

and the central pieces are

and

, with centers at

and 1, respectively. Each piece

is just a translated copy of

, and with the exception of

when n is odd, each piece

comes with an identical pair

symmetrically centered on the opposite side of the real line. See Figure 1 and Figure 2.

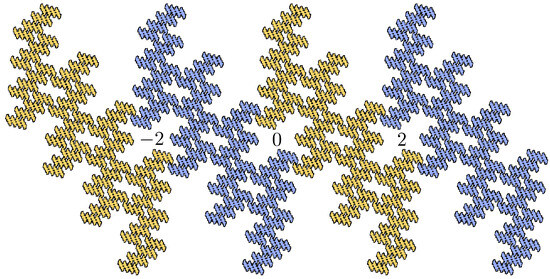

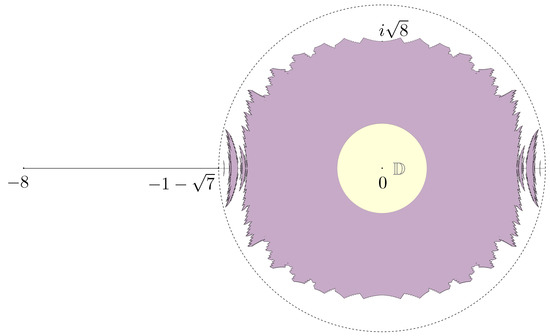

Figure 1.

Example of a collinear fractal

for a specific parameter

, illustrating the intersection of neighboring pieces centered at

. By symmetry, the three main components of

are centered at

.

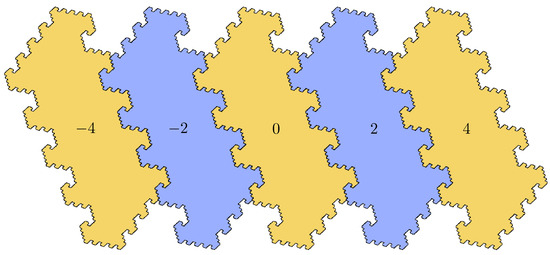

Figure 2.

Plane-filling collinear fractal

with

. The first-level pieces are centered at

.

A natural question is whether the attractor

is connected or completely disconnected. For IFS consisting of two maps (), there is a well-known dichotomy: the attractor is connected if and only if the images of the attractor under the two maps overlap, i.e., the two pieces

and

intersect.

For a general IFS with

contractions, this dichotomy does not hold in general: see, for instance, some examples of homogeneous self-similar sets in [13]. However, for the collinear fractals

considered here, we have a similar criterion: we will show (Proposition 1) that

is connected if and only if neighboring pieces on the right-hand side of (1) intersect.

The connectedness locus

is defined as the set of parameters c for which

is connected:

In the last decades, considerable efforts have been dedicated to understanding the topological properties of the set

. It is worth noticing that traditionally, the open unit disk has been the preferred parameter space for studying

. However, using its geometric inversion

is advantageous to clarify the boundary of

and simplify the geometric arguments.

In 2008, Bandt and Hung [14] introduced a family of self-similar sets known as n-gon fractals for

with

and parameterized by

, which reduce to our collinear fractals

when

. The authors proved that the corresponding connectedness loci

are regular-closed for all

:

The regular-closedness of

was proved in 2020 by Himeki and Ishii [15] by extending some techniques from [16]. The extreme points of the n-gon fractals were characterized by Calegari and Walker in [17]. Bousch [18] proved that

is connected for any

. The same author [19] also showed that

is connected and locally connected. Finally, Nakajima [20] extended the work of Bousch proving the local connectedness of

for any

. Therefore, the problems concerning the regular-closedness, connectedness, and local connectedness of

have been fully solved.

Going back to our sets

, it turns out that Nakajima’s general framework for studying the connectivity of the set of zeros of power series can be directly applied to our families of collinear fractals, which results in the sets

being connected and locally connected for any

(Theorem 1 in Section 2).

This paper focuses on understanding the connectedness loci

for any

. The case

, sometimes referred to as the “Mandelbrot set for a pair of linear maps”, has been extensively studied [16,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], but less is known for

. Bandt [23] conjectured that

is contained in the closure of its interior; that is, the nonreal part of

is regular-closed. Solomyak and Xu [24] made significant progress toward this conjecture by showing that a nontrivial portion

of

near the imaginary axis is the closure of its interior,

For a set

, its set of differences will be denoted as

In 2017, Calegari, Koch, and Walker [16] proved Bandt’s conjecture by introducing the technique of traps to certify interior points of

. The authors also wondered about the properties of

for

and its set of differences, which turns out to be

, leaving the further investigation of

for

as an open problem. In this paper, we address this not only for

but also for any

. We extend Solomyak and Xu’s covering property lemma to all

. Specifically, we improve and adapt the techniques used in [24] to the general setting. As a result, we obtain that for

, the covering property lemma suffices to prove the generalized Bandt’s conjecture, namely, that

is contained in the closure of its interior.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we introduce some basic definitions and establish some properties of collinear fractals

and their connectedness locus

.

Proposition 1.

For any integer

,

is connected if and only if

Proof.

It is immediate that the condition

is equivalent to the property that, for any pair

,

In other words, that any two neighboring pieces have a nonempty intersection.

Consider the connectivity graph G, which is a combinatorial graph whose vertices are the n elements of

and there is an edge connecting a pair of vertices

if and only if the corresponding first-level pieces

and

intersect. Now, observe that either G contains all the edges

for

if (2) holds, or G is a collection of n singletons (with no edges) otherwise. So, the proposition follows from the well-known fact that a self-similar set is connected if and only if the corresponding connectivity graph is connected [33,34]. □

An explicit representation of

is well known [13] and is given by

From (3) and the fact that

, it easily follows that the set of differences of

is

Define now the set

Using these definitions, we can characterize the connectedness locus

as follows.

Proposition 2.

For any integer

,

Proof.

From Proposition 1 and the characterization (3) of

, it follows that

is connected if and only if

where in the last equality we have used (4). This equality, again using (3), implies that there exist

and

such that

□

The subsequent result is a direct consequence of Proposition 2 and the straightforward observation that

. See Figure 3.

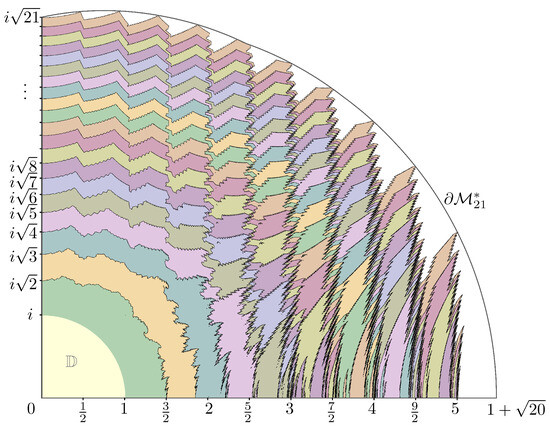

Figure 3.

Superimposed arrangement of

,

, …,

constrained within the upper-right section of the complex plane. From Proposition 3, we know that the connectedness loci are nested. The illustration suggests the existence of infinitely many holes, and that for

, the intersection

is nonempty.

Proposition 3.

for any integer

.

In order to estimate a bounding region for

, we will use a deep connection between

and the set of zeros of a larger class of power series investigated earlier by Beaucoup et al. [35]. Let

be the convex hull of

. We define the convexity set as

In Figure 4, we have represented the convexity sets

for

.

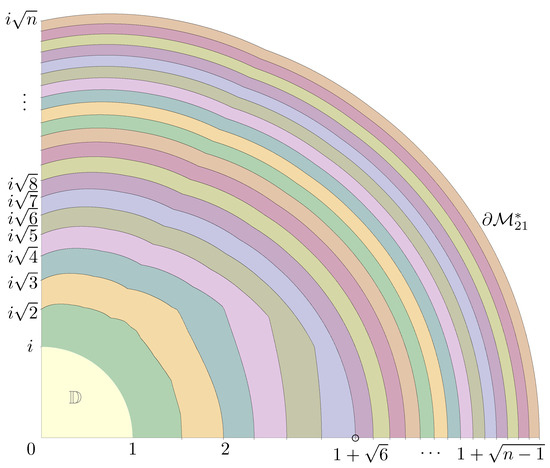

Figure 4.

Convexity sets

,

, …,

constrained within the upper-right section of the complex plane. From Proposition 4, we know that

.

In what follows, the closed disk of radius r centered at

will be denoted by

.

Proposition 4.

For any integer

,

Proof.

The inclusion

comes directly from the definition (6), the fact that

and Proposition 2.

Let us now see that

. In [35], the authors study the set

of all zeros with an absolute value smaller than 1 of the power series of the form

for a positive real number g. Note that by definition (6),

is nothing more than the inversion of the set

when

. Let

be the infimum of the moduli of all numbers in

with a fixed argument

. Theorem A of [35] states that

, with the equality achieved when

. By inversion and taking

, this proves that

.

On the other hand, Theorem B of [35] states that

for all

. Taking inverses and setting

, this implies that

. □

Additional bounds for

are provided by the following result, which corresponds to Lemma 2.5 of [13].

Proposition 5.

For any integer

,

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- .

By Propositions 4 and 5(i), the boundary of

lies essentially in the closed annulus

. In fact, the contention is not strict due to the antennae given by Proposition 5(ii). This peculiar feature of the sets

restricted to the real axis has been previously described for

in [16,21,23,27]. See Figure 5 for a representation of the connectedness locus

with the interval

removed from the positive real antenna.

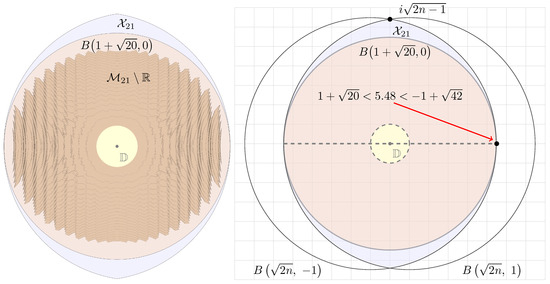

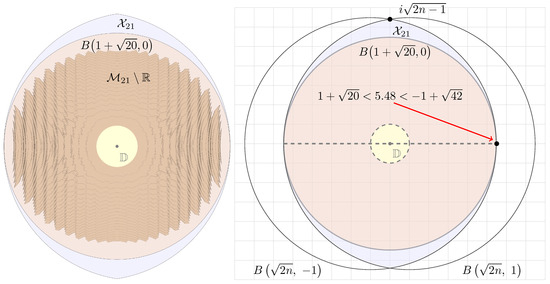

Figure 5.

The connectedness locus

. From Proposition 4, we know that

is contained in a disk of radius

.

Finally, as mentioned in Section 1, Nakajima’s study of the set of zeros of power series [20] can be applied to our families of collinear fractals. Specifically, in view of Proposition 5(ii) and taking into account that

, we can use Theorem B of [20] with

to obtain the following result.

Theorem 1.

is connected and locally connected for any integer

.

3. Statement of the Main Result

To state the main result of this paper, we need to define a particular region

as follows. Inspired by the methods in [24], we define the set

as

See Figure 6 for an illustration of the region

.

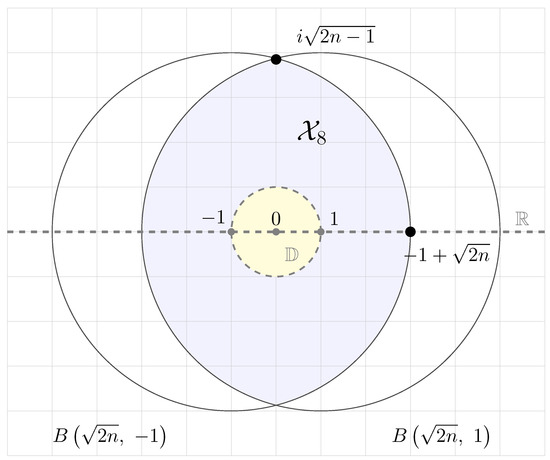

Figure 6.

Illustration of the region

defined in (7) for

. The shaded area represents

, which is the intersection of two disks of radius

centered at −1 and 1, excluding the unit disk

and the real axis

.

Theorem 2.

for any integer

. Moreover, if

, then

.

An immediate consequence of Theorem 2 is that the generalized Bandt’s conjecture is true for

.

The proof of Theorem 2 provides numerous specific examples of interior points in

. Let

be the set of zeros of polynomials with coefficients in

defined as

We will show that every point in

is located within the interior of

.

4. Proof of Theorem 2

To prove Theorem 2, we need some preliminary lemmas, adapting techniques from [24]. The first result is standard: see, for instance, Lemma 7 of [22].

Lemma 1.

If

is a compact set,

, and

then

.

Lemma 2.

If

and there exist

such that

then

.

Proof.

Our hypothesis, via (3) and (5), implies that

for some sequence

such that

. Now, take

for

and

for all

. Rewrite (9) as

Since

for all

, Proposition 2 tells us that

. □

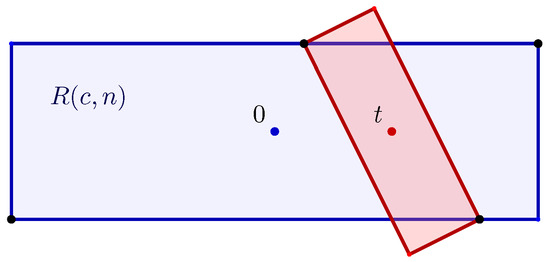

Next, we state a covering property which will be the key tool to prove Theorem 2. Its proof is much simpler than the one given by Solomyak and Xu for the case

, see [24], Lemma 3.3. For instance, they lacked an explicit parameterization for the covering rectangle. Let

denote the rectangle centered at the origin with vertices

where

is the complex conjugate of the vertex

defined as

where

denotes the real part of c. The expression of the vertex

in terms of c and n was obtained by imposing the geometric conditions prescribed in the proof of the covering property (Lemma 3).

Lemma 3

(covering property). For any

, the rectangle

is covered by its n first-level images

Proof.

Recall that

is the rectangle (10) centered at the origin with vertices defined in (11). One can easily check that for any

, there is a pair of diagonally opposing vertices of the rectangle

placed along the horizontal lines containing the upper and lower edges of

. The remaining pair of vertices of

are placed above and below those lines (see Figure 7).

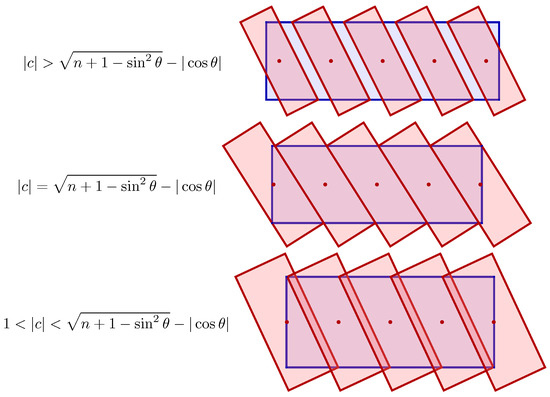

Figure 7.

Geometric configuration of the rectangle

and its image

for

.

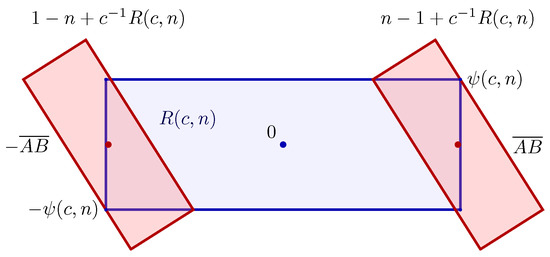

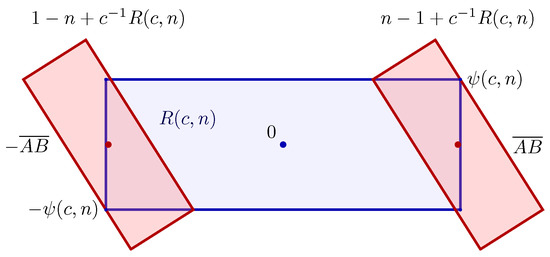

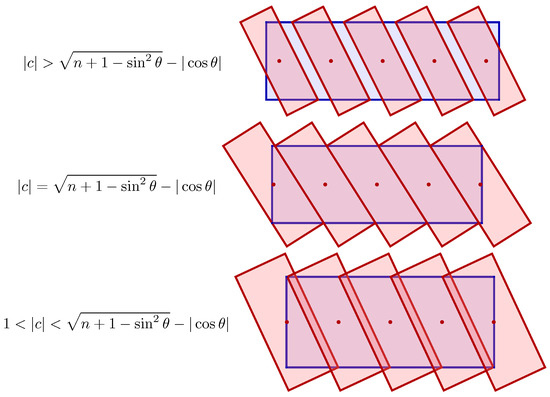

To show that the n rectangles

cover

as long as the parameter c is in

, consider the outer boundary of

defined as

which, after some algebraic manipulations, can be implicitly parameterized by

where

denotes the argument of c.

Now, observe that if the parameter c satisfies (12), then

and the vertices

and

intersect the edges

and

of the leftmost and rightmost rectangles, where

and

. See Figure 8. Moreover, the n rectangles

intersect tangentially side by side, thus critically covering the rectangle

; see Figure 9.

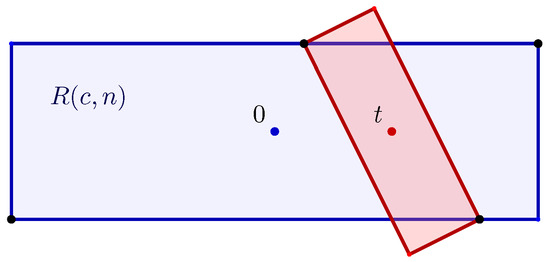

Figure 8.

An illustration of the critical case

in the proof of Lemma 3.

Figure 9.

An illustration of the proof of the covering property (Lemma 3).

The following lemma is a standard consequence of Rouché’s theorem. Recall that

denotes the set of zeros of polynomials with coefficients in

given in (8).

Lemma 4.

.

Now, we have all the necessary ingredients to prove Theorem 2.

Proof of Theorem 2.

Let us prove that

for any

. In view of Lemma 4, it is enough to show that

. So, let

. We must see that there is an open neighborhood U of

contained in

.

Since

, there exist

such that

Note that

is a solid (with nonempty interior) rectangle centered at 0. Hence,

We are assuming that

. Moreover, the functions (11) that define the rectangles

are continuous with respect to c. These facts, together with (13) and the continuity of

, imply that there is an open neighbourhood U of

such that

and

On the other hand, from Lemmas 1 and 3, it follows that

Let us now prove the second statement of the theorem. We must show that for

, we have

. The inclusion

is obvious because

. Hence, we only need to show that

for

. It is easy to check that

for

. See Figure 10 for an example. In consequence,

Figure 10.

The set

contained in

. Since

, the region

contains

which in turn contains

by Proposition 4.

Since

and, from Proposition 4, we know that

is contained within the disk

, it follows that

. □

5. Remarks and Suggestions on Further Research

The connection we established between the convexity set

and the connectedness locus

is clearer when we consider the following characterizations of

and

involving the set

of differences of

and its convex hull

.

In particular, the condition

implies that there is an asymptotic self-similarity between

and

. For each

, we have

, and a neighborhood of c from

looks asymptotically similar to a neighborhood of

from

; observe the animation [36].

For

, we conjecture that the set

is regular-closed. One could try to extend the partial results of Nguyen Viet Hung for

, who, as part of his Ph.D. thesis [37], obtained three new regions in addition to

. Note that for any n, it holds that

, and when

, it is expected that

possesses a nonempty interior, given that the similarity dimension of the IFS exceeds 2. Computational evidence ([38] personal notes) suggests that by replacing the rectangle

with the parallelogram

centered at the origin with vertices

we have that

for any non-real

. These findings are part of ongoing work and will be further investigated in future research.

Additionally, inspired by Solomyak and Xu’s investigation into complex Bernoulli convolutions [24], exploring the measures supported on

and their absolute continuity could prove to be a productive avenue for future research.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we have introduced the family of collinear fractals

defined as the compact sets invariant under the iterated function system

, where c is a complex parameter outside the unit disk and t ranges over the symmetric set of integers

.

For any integer

, we define the connectedness locus

as the set of parameters c for which

is connected. Among other results, we have proven that a nontrivial portion of

is contained in the closure of its interior for any

. In addition, we prove that when

, the whole

lies in fact within the closure of its interior. In other words, the generalized Bandt’s conjecture about the regular-closedness of

is true.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.E.; methodology, B.E.; formal analysis, B.E., D.J. and J.S.; investigation, B.E.; writing—original draft preparation, B.E.; writing—review and editing, D.J. and J.S.; visualization, B.E.; supervision, D.J. and J.S.; funding acquisition, D.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been funded by grants PID2023-146424NB-I00 of Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades and 2021 SGR 00113 of Generalitat de Catalunya. The first author has been supported by the research grant from the University of Girona (UdG) in collaboration with Banco Santander, through UdG Grant Programme for Researchers in Training (IFUdG 2022–2024).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akiyama, S.; Loridant, B.; Thuswaldner, J. Topology of planar self-affine tiles with collinear digit set. J. Fractal Geom. 2021, 8, 53–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.D. Plots of Roots of Polynomials with Integer Coefficients. 2006. Available online: http://jdc.math.uwo.ca/roots/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Baez, J.C.; Christensen, J.D.; Derbyshire, S. The Beauty of Roots. Not. Am. Math. Soc. 2023, 70, 1495–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.H.; Borwein, J.M.; Calkin, N.J.; Girgensohn, R.; Luke, D.R.; Moll, V.H. Experimental Mathematics in Action; A K Peters: Natick, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borwein, P.; Erdélyi, T.; Littmann, F. Polynomials with coefficients from a finite set. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2008, 360, 5145–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odlyzko, A.M.; Poonen, B. Zeros of Polynomials with 0, 1 Coefficients. L’Enseignement Mathématique 1993, 39, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, H.; Davis, D.; Lindsey, K.; Wu, C. The shape of Thurston’s Master Teapot. Adv. Math. 2021, 377, 107481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, K.; Wu, C. A characterization of Thurston’s Master Teapot. Ergod. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2023, 43, 3354–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, K.; Tiozzo, G.; Wu, C. Master teapots and entropy algorithms for the Mandelbrot set. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriss, E.; Stange, K.E.; Trettel, S. Algebraic Number Starscapes. Exp. Math. 2022, 31, 1098–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfsman-Hopkins, G.; Xu, S. Searching for rigidity in algebraic starscapes. J. Math. Arts 2022, 16, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra, J. Bohemian Matrices: Past, Present and Future. In Proceedings of the Communications in Computer and Information Science, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2–6 November 2020; Volume 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomyak, B. Measure and dimension for some fractal families. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1998, 124, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandt, C.; Hung, N.V. Fractal n-gons and their Mandelbrot sets. Nonlinearity 2008, 21, 2653–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Himeki, Y.; Ishii, Y. M4 is regular-closed. Ergod. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2020, 40, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calegari, D.; Koch, S.; Walker, A. Roots, Schottky semigroups, and a proof of Bandt’s conjecture. Ergod. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2017, 37, 2487–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calegari, D.; Walker, A. Extreme points in limit sets. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2019, 147, 3829–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousch, T. Sur Quelques Problémes de Dynamique Holomorphe. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Paris-Sud, Orsay, France, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bousch, T. Connexité locale et par chemins holderiens pour les systemes itérés de fonctions. Unpublished work. 1993; 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, Y. Mandelbrot set for fractal n-gons and zeros of power series. Topol. Appl. 2024, 350, 108918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnsley, M.F.; Harrington, A.N. A Mandelbrot set for pairs of linear maps. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1985, 15, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indlekofer, K.H.; Járai, A.; Kátai, I. On some properties of attractors generated by iterated function systems. Acta Sci. Math. 1995, 60, 411. [Google Scholar]

- Bandt, C. On the Mandelbrot set for pairs of linear maps. Nonlinearity 2002, 15, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomyak, B.; Xu, H. On the ‘Mandelbrot set’ for a pair of linear maps and complex Bernoulli convolutions. Nonlinearity 2003, 16, 1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Solomyak, B. Mandelbrot set for a pair of linear maps: The local geometry. Anal. Theory Appl. 2004, 20, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomyak, B. On the ’Mandelbrot set’ for pairs of linear maps: Asymptotic self-similarity. Nonlinearity 2005, 18, 1927–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmerkin, P.; Solomyak, B. Zeros of {-1, 0, 1} Power Series and Connectedness Loci for Self-Affine Sets. Exp. Math. 2006, 15, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bandt, C.; Hung, N. Self-similar sets with an open set condition and great variety of overlaps. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2008, 136, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, K.G.; Sidorov, N. Two-dimensional self-affine sets with interior points, and the set of uniqueness. Nonlinearity 2015, 29, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, K.G.; Sidorov, N. On a family of self-affine sets: Topology, uniqueness, simultaneous expansions. Ergod. Theory Dyn. Syst. 2017, 37, 193–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmerkin, P.; Solomyak, B. Absolute continuity of complex Bernoulli convolutions. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2016, 161, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, S.; Pérez, R.A. Accessibility of the Boundary of the Thurston Set. Exp. Math. 2023, 32, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandt, C.; Keller, K. Self-Similar Sets 2. A Simple Approach to the Topological Structure of Fractals. Math. Nachrichten 1991, 154, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, M. On the structure of self-similar sets. Jpn. J. Appl. Math. 1985, 2, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaucoup, F.; Borwein, P.; Boyd, D.; Pinner, C. Power series with restricted coefficients and a root on a given ray. Math. Comput. 1998, 67, 715–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espigule, B. Asymptotic Self-Similarity Between Collinear Fractals E(c,2n − 1) and Mn. 2024. Available online: https://youtu.be/11NZDHNahJs (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Hung, N.V. Polygon Fractals. Ph.D. Thesis, Greifswald University, Greifswald, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Espigule, B. Mandelbrot Set Mn for Collinear Fractals E(c,n). Available online: https://www.complextrees.com/collinear/talks/Talk2024June10th.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).