Abstract

Extensive research has outlined the potential of augmented, mixed, and virtual reality applications. However, little attention has been paid to scalability enhancements fostering practical adoption. In this paper, we introduce the concept of scalable extended reality (XR), i.e., spaces scaling between different displays and degrees of virtuality that can be entered by multiple, possibly distributed users. The development of such XR spaces concerns several research fields. To provide bidirectional interaction and maintain consistency with the real environment, virtual reconstructions of physical scenes need to be segmented semantically and adapted dynamically. Moreover, scalable interaction techniques for selection, manipulation, and navigation as well as a world-stabilized rendering of 2D annotations in 3D space are needed to let users intuitively switch between handheld and head-mounted displays. Collaborative settings should further integrate access control and awareness cues indicating the collaborators’ locations and actions. While many of these topics were investigated by previous research, very few have considered their integration to enhance scalability. Addressing this gap, we review related previous research, list current barriers to the development of XR spaces, and highlight dependencies between them.

1. Introduction

Using different kinds of extended reality (XR) technologies to enter augmented, mixed, or virtual reality scenes has been considered supportive for various areas of application. For instance, users could receive contextual information on demand during training or maintenance tasks, and product development processes could benefit from fast and cheap modifications as virtual augmentations are adapted accordingly. Furthermore, connecting multiple head-mounted or handheld displays in one network holds great potential to provide co-located as well as distributed collaborators with customized accesses to a joint space. However, so far the majority of XR applications are limited to single use cases, specific technology, and two users. We believe that this lack of scalability limits the practical adoption of XR technologies as switching between tasks and technologies requires costly adaptions of the setup, as well as relearning interaction techniques.

Seeking to reduce these efforts, we introduce the concept of scalable XR spaces (XR) that we deem beneficial for various applications. For instance, product development could be supported by systems scaling from virtual to hybrid prototypes, and finally physical products augmented with single annotations. Similarly, virtuality could decrease according to established skills in training systems or progress at construction sites. Furthermore, co-located teams operating in augmented or mixed reality could be joined by absent collaborators entering virtual reconstructions of their scene. Depending on individual tasks and preferences, collaborators could thereby be provided either with head-mounted or handheld displays.

While previous research dealt rather separately with the three topics that we consider most crucial for the development of XR spaces (i.e., collaboration support features, consistent and accessible visualizations, and intuitive interaction techniques), we focus on their integration to enhance scalability. To this end, we review the latest research in related fields and propose a future research agenda that lists both remaining and newly arising research topics.

2. Background and Terminology

2.1. Augmented, Mixed, and Virtual Reality

In 1994, Milgram and Kishino [1] introduced a taxonomy categorizing technologies that integrate virtual components according to their degree of virtuality, which is today known as the so-called reality–virtuality continuum [2]. Virtual reality (VR) applications are located at the right end of the continuum. In such completely computer-generated environments, users experience particularly high levels of immersion. Moving along the continuum to the left, the degree of virtuality decreases. As depicted in Figure 1, the term mixed reality (MR) encompasses both the augmentation of virtual scenes with real contents (augmented virtuality, AV) as well as the augmentation of real scenes with virtual contents (augmented reality, AR). While the continuum presents AR and AV as equal, the amount of research that has been published subsequent to its introduction is significantly higher for AR than for AV. This negligence of AV is also reflected in today’s general interpretation of MR. Currently, MR is associated with spaces that embed virtual objects into the physical world (i.e., onto, in front of, or behind real-world surfaces), while AR instead refers to real-world scenes that are augmented with pure virtual overlays—independently of the scene’s physical constraints.

Figure 1.

The reality–virtuality continuum, reproduced with permission from [2].

While most smartphones and tablets can be used as handheld displays (HHDs) to enter MR and VR spaces, the quality of the experience is heavily affected by incorporated technology and sensors. For instance, the LiDAR scanner incorporated in Apple’s iPad Pro [3] enhances scene scanning and thus embedding virtual objects into the real world. Apart from HHDs, users may wear head-mounted displays (HMDs). To access VR scenes, headsets such as the HTC VIVE [4], Oculus Rift, or Oculus Quest [5] may be used. HMDs that allow users to enter MR scenes include the Microsoft HoloLens [6], Magic Leap [7], and Google Glass [8]. Furthermore, Apple is expected to release a game-changing HMD within the next years [9]. While some of these technologies provide interaction with built-in gesture recognition, others take use of touchscreens, external handheld controllers, or tracking technology such as the Leap Motion controller [10]. Furthermore, projection-based technologies such as Powerwalls or spatial AR can be employed. In this paper, we focus on the scalability between HMDs and HHDs, i.e., environments that can be accessed individually with 2D or 3D displays.

2.2. Scalable Extended Reality (XR)

Recently, the term extended reality, and less often, cross reality (XR), is increasingly being used as an umbrella term for different technologies located along the reality–virtuality continuum [1,2]. In this paper, we use XR to refer to AR, MR, and VR applications in general and summarize HMDs and HHDs by XR devices or XR technologies.

In addition, we introduce the concept of scalable extended reality (XR) describing spaces that scale along the three different dimensions depicted in Figure 2: ■ from low to high degrees of virtuality (i.e., from the left to the right end of the reality–virtuality continuum [1,2]); ■ between different devices (i.e., HMDs and HHDs); and ■ from single users to multiple collaborators that may be located at different sites. In the following, we use the term XR whenever we refer to the concept of these highly scalable spaces.

Figure 2.

Scalable extended reality (XR) spaces providing scalability between different ■ degrees of virtuality, ■ devices, and ■ numbers of collaborators.

While existing XR applications are mostly limited to single use cases, specific technology, and two users, XR spaces could serve as flexible, long-time training or working environments. Highly scalable visualization and interaction techniques could increase memorability, allowing users to switch intuitively between different degrees of virtuality and devices while keeping their focus on the actual task. For instance, product development could be supported by applications that scale from initial virtual prototypes to physical prototypes that are augmented with single virtual contents, i.e., the degree of virtuality decreases as the product evolves. In this context, time and costs could be reduced as the modification of virtual product parts is faster and cheaper than for physical parts. Since different XR technologies might be appropriate for different degrees of virtuality and different tasks, the memorability of interaction techniques needs to be enhanced to prevent users from relearning interaction techniques whenever they switch to another device. Considering multiple system users, each collaborator could be provided with the information needed for task completion on demand via customized augmentations and join the XR space in MR or VR scenes using HMDs or HHDs depending on their individual preferences and the collaborative setting.

Johansen [11] distinguished groupware systems with respect to time and place. In this paper, we mainly focus on synchronous collaboration, i.e., collaborators are interacting at the same time but can be located at the same (co-located collaboration) or different sites (distributed or remote collaboration). In this context, we use the term on-site collaborator for anyone located in the actual working environment (e.g., the location of a real factory or physical prototype) and the term off-site collaborator for anyone joining the session from a distant location. Previous research also refers to this off-site collaborator as a remote expert. While the term remote implies that two collaborators are located at different sites, it does not indicate which collaborator is located at which site. This information is, however, of high relevance in XR spaces where different technologies may be used for on-site collaborators in an MR scene (i.e., the working environment with virtual augmentations) and off-site collaborators immersed in a VR scene (i.e., the virtual replication of the working environment including the augmentations). Since such XR spaces could support not only co-located but also distributed collaboration, they hold considerable potential for saving costs and time related to traveling.

3. Towards Scalable Extended Reality (XR): Relevant Topics and Related Research

While XR spaces as outlined above are not yet available, previous research in various fields may contribute to their development. Based on the three dimensions (see Figure 2) along which XR spaces are meant to scale, we define the following three topics to be relevant: Making XR spaces scale ■ from single users to multiple collaborators requires appropriate collaboration support features; providing scalability ■ between different degrees of virtuality requires a consistent and accessible visualization of virtual augmentations and replications of physical scenes; and enhancing scalability ■ between different XR technologies requires designing interaction techniques in a way that lets users intuitively switch between devices. As a first step towards developing XR, this section provides an overview of related research in each of these fields and explains where integrating previous research outcomes to build XR spaces is challenging. This review served as a basis for establishing the agenda of remaining and newly arising questions that is presented in Section 4.

3.1. Collaboration Support Features

Depending on the configuration of the XR space, collaboration can be very different from on-site, face-to-face collaboration. For instance, collaborators may not be able to see or hear each other, which may impede natural interaction among them. To overcome these barriers, previous research proposed several features to support communication and coordination in co-located [12,13] or distributed [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] scenarios, using HHDs [12,13], HMDs [14,15,16,17,18,20,21,22], or both [19,23].

Such collaboration support features include awareness cues indicating where collaborators are or what they do. To represent absent collaborators in space, previous research considered different kinds of avatars: While some used human-like avatars [18,20,21,24], others only visualized parts of the collaborator using virtual replications of the respective XR device [18,19,25], view frustums [14,21,25], or further virtual objects as abstract representations [19,22,25]. While most avatars were created based on hand and head movements, some approaches tracked the entire body. For instance, Yu et al. [26] tracked users based on their shadow to create the corresponding avatar in real time and Ahuja et al. [27] estimated body postures combining the views of multiple users’ HHD cameras in a co-located scenario. An approach combining 2D and 3D displays was presented by Ibayashi et al. [24]. Collaborators could touch at a tabletop interface to point at specific locations in a virtual space while another collaborator entering the same space with an HMD could see large virtual hands pointing at the respective location as well as the tabletop users’ faces captured by a camera. The HMD user on the other side could point at certain locations by touching on an HHD mounted in front of the HMD and was represented by an avatar whose arms and head orientations were adjusted accordingly. Piumsomboon et al. [20] note that life-size avatars of collaborators are likely to cause occlusions and might exceed fields of view. To this end, they proposed a miniature avatar that represented the off-site collaborator and mimicked the respective gaze direction and gestures. A miniature of the life-size avatar representing the off-site collaborator followed the on-site collaborator’s gaze while a ring indicator at the miniature’s feet indicated the life-size avatar’s location [20]. In [21], the miniature avatar representing the off-site collaborator was not attached to the on-site collaborator’s field of view but could add a visual cue (i.e., a virtually burning torch) to attract the on-site collaborator’s attention. Lee et al. [17] found that augmenting a collaborator’s view with a rectangle, depicting the other collaborator’s current field of view, failed when using HMDs with different viewing angles. Thus, they reduced the size of the rectangles according to the viewing angle provided by the output device. Similar to [14], they considered the integration of arrows pointing towards the other collaborator’s location, as in large 3D spaces collaborators could have problems finding each other when they have very opposing fields of view.

Distributed collaboration, especially remote assistance, requires collaborators to reference objects or locations in the joint space. A common approach to indicate where someone is pointing at is to render rays originating at the user’s eye [14,28] or hand [13,16,20,22,23]. Instead of rendering the entire ray, De Pace et al. [18] only rendered a circle where ray and object collided. Pereira et al. [19] highlighted collaborators and objects with arrows and supported navigation to specific targets in space with moving radars and transparent walls. Concerning the integration of cues for hand movements, previous work mainly focused on tracking the off-site collaborator’s hands, as the hands of the on-site collaborator are often captured within the reconstruction of the MR space. 3D cameras [15] and the Leap Motion controller [14,16,17] were used to capture the off-site collaborator’s hand gestures and augment the on-site collaborator’s view with the obtained mesh in real time. Others [19,21,22] tracked the motion of VR controllers to provide an abstract representation of hand movements. In the approach presented by Kim et al. [16], the off-site collaborator could further perform different hand gestures to activate a ray or draw virtual sketches into the shared environment.

More complex scenarios, especially those allowing active manipulations by multiple collaborators, require access control. Grandi et al. [13] allowed co-located collaborators interacting with HHDs to simultaneously manipulate an object by multiplying each transformation matrix with the one of the virtual object. Thereby, differently colored rays indicated which object a user selected and icons represented the manipulation being performed. On the contrary, Wells and Houben [12] allowed only one of the co-located collaborators to manipulate an object at a time. During manipulation, the respective object was locked for the other users as indicated by a colored border around the screen of the HHD. Pereira et al. [19] considered a master client which was supposed to give ownership to the other clients.

3.2. Consistent and Accessible Visualizations

XR spaces scaling between different degrees of virtuality (i.e., from the left to the right end of the reality–virtuality continuum [1,2] and vice versa), would allow augmenting on-site collaborators’ views in MR scenes while providing off-site collaborators with a virtual reconstruction of the on-site environment. To support effective collaboration, this reconstruction needs to be consistent with the on-site environment (i.e., changes in the physical environment need to be adapted in the virtual scene) and accessible (i.e., off-site collaborators should be able to reference certain parts in the scene and interact with virtual objects).

Previous research followed different approaches to provide off-site collaborators with a virtual reconstruction of physical scenes. The on-site environment was captured using technologies such as 360-degree cameras providing pictures [22] or videos [17,21,22], light fields constructed out of pictures taken with a smartphone [29], multiple RGB-D [30] cameras, as well as built-in spatial mapping [22,31] to generate a mesh of the environment. While some captured the on-site environment prior to the actual collaboration [29,31], others provided online reconstruction of the on-site environment [17,21,30] allowing the virtual scene to be updated in line with changes on-site. Reconstructed scenes could be accessed via VR-HMDs [17,19,21,22,30,31] or HHDs [29].

To support collaboration in XR spaces, off-site collaborators should be provided with representations of physical scenes that offer high visual quality, live updates, viewpoint independence, and bidirectional manipulation. However, research to date has not found an approach that meets all of these quality criteria. In fact, a review of previous research revealed trade-offs among visual quality and further quality criteria: While 360-degree cameras deliver high visual quality, they also restrict the off-site collaborator’s viewpoint according to the camera’s position. In contrast to static 360-degree pictures, 360-degree videos provide the off-site collaborator with a dynamic representation of the on-site environment. A common approach to do so is to mount the 360-degree camera on an on-site collaborator’s head and provide the off-site collaborator with the corresponding video stream [17,21]. As such, the orientation of the 360-degree video will, however, always depend on the orientation of the on-site collaborator’s head, as noted by Lee et al. [17]. To provide the off-site collaborator with an independent view, they tracked the orientation of the on-site collaborator’s head and adjusted the off-site collaborator’s view accordingly. Furthermore, reconstructions based on 360-degree cameras usually prevent bidirectional manipulation as off-site collaborators can see everything happening on-site but cannot manipulate virtual objects themselves. Instead, several visual cues were rendered as virtual augmentations to let off-site collaborators instruct the on-site collaborator throughout task performance [17,21]. Since static 360-degree pictures do not capture changes on-site, Teo et al. [22,32] allowed off-site collaborators to choose between a 360-degree video stream for a dynamic, high-quality visualization and a static 3D mesh textured with a 360-degree picture to explore the space independently of the on-site collaborator. In [33], they developed this system further, such that off-site collaborators could retexture the static mesh with different 360-degree pictures. However, they found that this approach is likely to produce holes in the virtual scene at spots where objects in the picture occlude each other.

Geometric reconstructions of physical scenes obtained by depth cameras aim to enhance the off-site collaborator’s spatial awareness of the scene and allow exploring the space independently of the on-site collaborator’s location. However, providing live updates of changes in the on-site environment is challenging, as only those parts in space can be updated that are captured by the depth camera in this particular moment. Approaches that used sensors incorporated in the HoloLens captured a static reconstruction of the scene prior to the actual collaboration [22,31,32,33]. For instance, Tanaya et al. [31] used a mesh obtained with HoloToolkit Spatial Mapping to provide VR-HMD users with a reconstruction of an MR scene. Using this approach, live updates would depend heavily on the on-site collaborator’s head movements and are thus likely to be delayed. Providing live updates independently of the user’s position and orientation, as presented by Lindlbauer and Wilson [30], requires a more complex setup. They used eight RGB-D cameras to provide a geometric live reconstruction of a physical room that allowed detailed modifications by the user such as erasing, copying, or reshaping real-world objects. Real-time manipulation was enabled by performing interactions on a voxel grid—a volumetric representation of the reconstructed space where each voxel held information on possible manipulations—which was computationally less expensive than performing interactions on the underlying mesh. Mohr et al. [29], however, note that the visual quality of such approaches may be impaired by shiny and transparent surfaces which are common in industrial environments—a major application field for XR technologies. Addressing this issue, they proposed to provide off-site collaborators with a light field of the relevant parts of the workspace. To do so, the on-site collaborator used an HHD to take pictures that were stored together with the HHD’s position and orientation. As such, the off-site collaborator could add 3D annotations to the generated light field: a high-quality, yet static visualization of the workspace. While increasing visual quality and accessibility is expected to enhance collaboration, it is also likely to increase the amount of data that need to be processed. This, on the other hand, may cause latency, which could impede communication among collaborators. Hence, another crucial research topic concerns the optimization of data processing. In this context, Stotko et al. [34] presented a framework for sharing reconstructed static scenes based on RGB-D images with multiple clients in real time. Moreover, the amount of data to be processed may be minimized by the incorporation of digital twins. As such, real-world objects that change their appearance in line with accessible sensor values would not have to be tracked and re-rendered continuously. Instead, the respective sensor values could be sent to the off-site collaborator’s application which renders the virtual appearance of the object according to its digital twin’s current state. In addition, some parts of the real environment could not only be manipulated by the on-site collaborator but also by the off-site collaborator. For instance, Jeršov and Tepljakov [35] presented a system which allowed altering the water levels of a physical multi-tank system by manipulating the system’s digital twin in a virtual environment.

To support bidirectional interaction in XR, off-site collaborators should further be able to access and reference objects in the joint space. While the approach presented by Lindlbauer and Wilson [30] allows users to manipulate certain parts in the reconstructed space, they did not provide semantic segmentation, i.e., manipulations were not performed on specific objects but on a set of voxels selected by the user. A semantic segmentation of the reconstructed space would allow storing additional information as well as predefined manipulation behavior in semantically segmented objects, and is hence expected to accelerate object selection and to facilitate interaction. Schütt et al. [36] presented an approach that allows to segment real-world spaces semantically while using an MR application. They used a mesh of a static scene that was captured by the HoloLens prior to the segmentation. Using the actual MR application, the HoloLens sent RGB images to a server application that followed an existing method to perform the semantic segmentation. First, class probabilities were assigned to each pixel and subsequently the mesh was segmented by its projection onto these probabilities. By assigning each vertex in the mesh to one class, connected components of object-class vertices could be interpreted as semantic objects. The semantically segmented mesh was then back-projected onto the physical scene such that real-world objects could be highlighted, offering object-specific manipulation options upon selection. Automated annotation of 3D scenes could further benefit from recent advancements in deep learning. However, Dai et al. [37] noted that in this context labeled training data are missing. To address this issue, they presented a system that allowed novices to capture 3D scenes via RGB-D scans. The corresponding 3D meshes were reconstructed automatically and could be annotated by the user. As such, they were able to collect a large data set of labeled 3D scenes. Huang et al. [38] took use of this data set and presented an approach that allowed to semantically segment a 3D space described by supervoxels in real time. They noted that so far, applying deep learning techniques has been inefficient due to the large amounts of data describing the 3D scenes. To reduce the amount of data that need to be processed, they only considered voxels describing surfaces in the 3D environment and applied on-surface supervoxel clustering. Using a convolutional neural network, they were able to predict a semantic segmentation for these supervoxels.

As described above, XR environments are meant to be accessible with HHDs as well as with HMDs. While both technologies can be used to explore a 3D scene, anchoring 2D annotations in the 3D scene is not straightforward. Especially in collaborative settings, off-site collaborators may use HHDs to annotate the physical environment. However, simple virtual overlays such as annotations that are not semantically anchored in space will become useless whenever the on-site collaborator’s viewpoint differs from the one from which the annotation was added. This issue was addressed in several research papers [29,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Nuernberger et al. [43] proposed an advanced way to anchor 2D sketches of circles and arrows in a world-stabilized way. They used a gesture classifier to interpret the user’s drawing and scene surface normals to render the respective sketch in 3D space. Another approach was presented by Mohr et al. [29], who allowed the off-site collaborator to annotate light fields on a 2D plane, which could afterwards be adjusted to the 3D scene by rotation and translation. As the on-site and off-site collaborator’s view relied on the same coordinate system, the annotations appeared as virtual augmentations in the on-site collaborator’s field of view when shared. The world-stabilized rendering of 2D annotations presented by Lien et al. [44] was based on an interactive segmentation technique. The 3D space was modeled as a graph consisting of three types of vertices representing the 2D annotation, 3D scene points, and 3D volumes. To localize the referenced target object, they proposed a method to label these vertices as part of the target or its background. As such, the target object could be highlighted in a world-stabilized way.

3.3. Intuitive Interaction Techniques

XR technologies offer a variety of interaction techniques ranging from touch-interfaces and external controllers to input based on gaze, speech, or in-air gestures. Considering a single MR or VR application, the interaction technique is usually selected according to the specific task and the constraints posed by the technology. For instance, HHDs require at least one hand to hold the device and VR-HMDs usually prevent users from seeing their own bodies. As such, different interaction techniques might be considered most suitable for task completion with HMDs or HHDs in MR or VR applications. Concerning XR spaces, an additional criterion comes into play: the interaction technique should scale between HMDs and HHDs, i.e., the technique should remain intuitive to the users even when they switch devices. However, previous research has mostly focused individually on the various interaction modalities offered by XR technologies including in-air [45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54], touch-based [55,56,57,58,59], tangible [60,61,62], head-, gaze-, or speech-based [45,55,58,63,64,65], and multi-modal [55,58,64] input techniques to select and manipulate virtual objects as well as to navigate in space. Many of these approaches require tracking parts of the users’ bodies or external interaction devices. In the following, we present interaction techniques that mainly rely on optical or inertial tracking. Optical tracking, as noted by Fikkert et al. [66], offers low latency and high update rates. They distinguish between marker-based and markerless approaches. While marker-based approaches provide high accuracy, they are considered less intuitive than markerless approaches based on computer vision techniques. In the context of XR, a popular approach of markerless optical tracking was to capture input via hand gestures with the Leap Motion controller [25,47,50,51] or the sensors incorporated in the HoloLens [45,46]. For marker-based approaches, markers were attached to the user’s feet [53], upper body [49], or an external device [62] depending on the input modality. However, a major disadvantage of both markerless and marker-based optical tracking concerns the required direct line of sight between camera and target object. Depending on the XR setting and the camera’s position, this could cause discomfort and restrict the user’s mobility. In these cases, inertial tracking is considered beneficial. Previous work (e.g., [56,58]) tracked the position and orientation of external input devices in space using device-incorporated IMU sensors—an inertial measurement unit that usually consists of accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers. Such approaches do not limit interaction to a particular part in space. However, the respective sensors may have to be reset to maintain accuracy and correct drift errors [66]. Further approaches (e.g., [63,64,65]) used head-mounted eye trackers to provide input via fixations or eye movements. A detailed overview of approaches for eye tracking and head movement detection is provided by [67].

Selecting virtual objects is a key task in 3D spaces as it serves to highlight and to manipulate target items. Selection usually includes two steps: (1) pointing at the target and (2) confirming the choice. In the following, we refer to these substeps by the terms point and confirm. While some HMDs such as the HoloLens provide built-in gesture recognition using an incorporated camera, most VR-HMDs need to be equipped with additional sensors to allow selection via mid-air gestures. For instance, García-Pereira et al. [25] attached the Leap Motion controller to a VR-HMD that captured the user’s hand and augmented it with a ray when pointing at a target. However, tracking technology mounted on the user’s head requires arms to be raised high enough to be captured by the sensor and is thus likely to cause fatigue. Approaches that capture in-air gestures via external cameras provide tracking in more comfortable positions, but often require a complex setup and may limit the user’s mobility. For instance, Schwind et al. [49] attached 18 markers to the user’s arm and body that were tracked by 14 cameras. Seeking to reduce arm fatigue while maintaining mobility, previous research proposed several alternative selection techniques for HMD users. In this context, Brasier et al. [50] used the Leap Motion controller to create a virtual plane at the user’s waist, thigh, or wrist, which offered a more comfortable input position for small-scale hand movements to control a cursor in MR. Users could point at targets by moving the hand to the respective position in the virtual plane; keeping the cursor at the point of interest confirmed the choice. Taking use of the device-incorporated IMU, Ro et al. [56] provided users wearing an MR-HMD with a smartphone acting as a laser pointer to point at targets. At the same time, the touch interface of the smartphone served as an input modality for further manipulations. Similarly, Chen et al. [58] compared IMU-based interaction with smartphones and smartwatches acting as laser pointers. The cursor was hereby either controlled by the smart device only (i.e., the cursor could leave the field of view) or in a hybrid approach where the cursor always stayed within the field of view and large-scale movements could be performed by head movements and small-scale movements inside the current field of view with the smart device. Alternatively, a cursor fixed in the center of the field of view could be controlled by head movements only. Selections could then be confirmed by tapping on the touch interface or by wrist rotation (smartwatch). Instead of the laser pointer paradigm, they also considered using the smart device’s touch surface as a trackpad. However, the smartwatch display turned out to be too small for this approach. Another smartphone-based selection technique for MR-HMD users was proposed by Lee et al. [57]. Different (force) touch gestures were used to navigate a cursor to the starting point of a text section; the text section subsequent to the starting point could be selected either by performing a circular touch gesture or by selecting the end point. Besides text selection, this technique may also apply to other tasks. Besançon et al. [61] presented an approach for spatial selection with an HHD combining touch and tangible input. The user drew a shape on the touch interface which was then used to brush through the 3D data space by physically moving the HHD to select a set of 3D data points. Another tangible input technique was proposed by Wacker et al. [62], who used a 3D-printed pen with visual markers that allowed users holding an HHD to select virtual objects. Small spheres or rays represented the pen’s position and buttons could be used to confirm the selection. Further approaches that could reduce arm fatigue during selection rely on input via gaze and feet. As proposed by Müller et al. [53], users wearing an MR-HMD could tap on the floor with their optically tracked foot to select items on a virtual user interface that was either projected on the floor or in mid-air. Nukarinen et al. [63] evaluated two different gaze-based selection techniques where the object to be selected was focused via gaze and the selection was confirmed by either pressing a button or by keeping the gaze fixed on the object for a certain period of time. While this approach is limited to a single type of gaze input, Hassoumi and Hurter [65] presented an approach for the gaze-based input of numerical codes (i.e., each gaze gesture was mapped to a specific digit). To do so, the virtual numeric keypad was augmented with small dots that continuously traced the shape of the available digits such that digits could be entered by keeping the eyes fixed on the respective moving dot. A multi-modal approach to lock messages to real-world objects was presented by Bâce et al. [64]. Real-world objects were selected upon fixations detected by eye-trackers and information to be stored in the object was selected via touch on a smartwatch. Gaze gestures were used to lock and unlock the respective information.

Having selected a target object, users should be provided with suitable techniques to manipulate the virtual object’s position, orientation, and size. Chaconas and Höllerer [48] evaluated two-handed gestures to adapt the orientation and the size of virtual objects while wearing an MR-HMD. To yaw, roll, pitch, and scale virtual objects, users had to move their pinched hands relative to each other in predefined directions. An approach using one-handed gestures to grab and move virtual objects using smartphones was presented by Botev et al. [54]. Ro et al. [56] used conventional touch input with smartphones such as single and double taps, swiping, and dragging with two fingers for selection and subsequent manipulation. Concerning one-handed touch input, Fuvattanasilp et al. [59] highlighted the difficulty of controlling six degrees of freedom (DoFs) with one hand on an HHD. To address this issue, they presented an approach that reduced the number of DoFs that need to be controlled at once. The user selected the initial 2D position via tap and subsequently manipulated depth via a slide gesture along a ray on the HHD; the orientation was then adjusted automatically according to the direction of gravity (obtained by the built-in IMU) such that the user only had to rotate the object around this gravity vector with a slide gesture performed on the HHD. Further research considered tangible manipulation techniques. For instance, Bozgeyikli and Bozgeyikli [60] evaluated rotating and translating a virtual cube with an external controller, hand gestures, and tangible interaction (i.e., moving a physical cube that was tracked by a controller placed inside). The AR-Pen presented by Wacker et al. [62] allowed users holding an HHD to move virtual objects in the 3D scene. After selecting the respective object, it could be dragged and dropped by pressing and releasing buttons on the physical pen. Apart from the target’s position and orientation, users might also want to manipulate its size. For instance, Kiss et al. [45] evaluated different techniques for zooming in MR. To zoom in and out, users wearing an HMD could either move one pinched hand or an external controller along an imaginary axis, move two pinched hands towards or away from each other, or use voice commands using the keywords smaller or bigger. In this context, they noted that future research should further investigate how discrete input (such as provided by voice commands) affects interaction. To annotate targets in XR, users have to add new virtual objects into space. In this context, Chang et al. [46] asked MR-HMD users to draw virtual arrows and circles with pinched hands. The annotations were either rendered at the fingertip or at a 2D plane, which was determined by the intersection of a ray originating at the HMD and a real-world surface. Furthermore, Surale et al. [47] considered techniques for mode switching, such as changing colors during 3D line drawing. To this end, they evaluated different in-air hand gestures captured by a Leap Motion controller. The VR-HMD user either performed both line drawing and mode switching with the dominant hand, or used a two-handed approach where each operation was performed with one hand. Similar to [46], 3D lines were drawn with pinched hands. Mode-switching could be evoked by rotating the wrist or pinching another finger (one-handed approach), as well as by raising the non-dominant hand, forming a fist, clicking a controller, or touching the HMD (two-handed approach).

A key benefit of purely virtual environments concerns the available space that can hold even huge objects. While VR allows users to be immersed in virtual spaces that can be infinitely large, the size of the physical room they are actually located in is restricted in size. Thus, appropriate navigation techniques are needed. In this context, von Willich et al. [52] investigated the potential of different input techniques based on the position, pressure, and orientation of the user’s feet for locomotion in VR. The direction in which to move was either given by the direction a foot was pointing in, the relative direction between the two feet, or the side a user leaned towards (i.e., left or right, measured by pressure); the distance to the target point was either given by the height at which the forefoot was lifted, the distance between the two feet, or the part of the foot receiving the most pressure (i.e., toes or heels for small or large distances). Leveraging the available space in VR, Biener et al. [55] allocated multiple screens in a VR scene that are usually accessed with a desktop computer. They provided the VR-HMD users with a tablet that could be used similar to a trackpad to navigate on a virtual screen using one finger only and to switch between different virtual screens by performing a two-handed gesture on the tablet’s touchscreen, or by gazing at the specific screen. While two-handed interaction techniques were deemed beneficial in this case, they are not applicable to settings where at least one hand is needed to hold the HHD. Furthermore, Satriadi et al. [51] introduced two hybrid interaction techniques for navigation on large-scale horizontal maps aiming to reduce hand movement (i.e., arm fatigue) while maintaining precise interaction when needed. They combined an interaction technique based on a joystick metaphor where the zoom and pan rate was given by the displacement of the user’s hand from a starting position with indirect grab, a more intuitive and precise but also fatigue-prone technique, allowing users to pan and zoom by moving their hands in a pinched state.

4. A Future Research Agenda

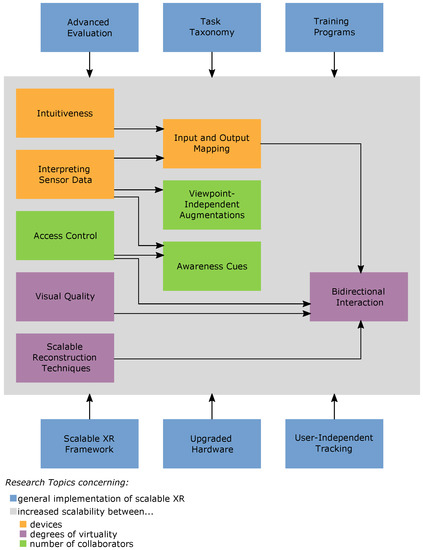

As summarized above, previous research focused on enhancing collaboration support features, visualization and interaction techniques in the context of XR settings. However, state-of-the-art research considers these topics separately and does not take into account the integration of research outcomes in each of these fields to support collaboration in XR spaces. Addressing this gap, we present a future research agenda that lists remaining as well as newly arising research questions. The proposed agenda is structured into topics concerning the ■ general implementation of XR and topics to increase scalability between ■ different devices (i.e., HMDs and HHDs), ■ different degrees of virtuality (i.e., from the left to the right end of the reality–virtuality continuum [1,2]), and ■ different numbers of collaborators that may be located at different sites. Expected contributions among these new research topics are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Research topics that are relevant to the development of XR spaces and expected contributions among them.

4.1. General Research Topics

■XR Framework. Since available XR technologies are provided by different manufacturers and run with different operating systems (e.g., MR-HMD: HoloLens by Microsoft [6], VR-HMD: VIVE by HTC [4], and HHD: iPad Pro by Apple [3]), incorporating all of them to a joint XR space requires cross-platform development which is impeded by the lack of available interfaces. To facilitate the development of such interfaces, future research should consider the development of a framework that formalizes the interactions with real and virtual objects and describes which kind of data need to be tracked and shared among the entities.

■Upgraded Hardware. To apply XR in practice, upgraded hardware is needed that enhances ergonomic aspects and provides larger fields of view. Some studies (e.g., [21,51]) used VR-HMDs to mirror the real-world scene, including the virtual augmentations. While currently available VR-HMDs provide larger viewing angles than MR-HMDs, this approach impedes leveraging the actual benefits of MR technologies such as reduced isolation and natural interaction with real-world objects.

■User-Independent Tracking. In previous research, hardware for tracking parts of the user’s body as well as to capture the on-site scene was attached to users. A common approach to incorporate hand gestures as awareness cues in the XR space was to attach the Leap Motion controller [10] to the off-site collaborator’s HMD. As such, the augmentation of the on-site collaborator’s view with the off-site collaborator’s hands depends heavily on the off-site collaborator’s hand and head movements. Similarly, tracking the physical scene with hardware attached to the on-site collaborators’ HMD will be affected by their head movements and position. Considering the practical adoption of XR spaces, these dependencies on human behavior should be decreased.

■Advanced Evaluation. The majority of the reviewed papers evaluated collaborative systems with two participants. While some pairs of collaborators knew each other prior to the experiment, others had never met before, and some researchers (e.g., [20,21]) employed actors to collaborate with all participants. The latter approach makes results more comparable but at the same time harder to transfer to real use cases. As such, it remains unclear if a system that turned out to support collaboration between an instructed and an uninstructed person will do so as well when used by two uninstructed collaborators. Furthermore, many studies were limited to simplified, short-term tasks. Hence, further research should take into account the evaluation with multiple collaborators performing real-world and long-term tasks.

■Task Taxonomy. Due to the variety of visualization and interaction techniques offered in XR, these technologies are deemed supportive in various fields of applications. As each field of application comes with individual requirements, developing and configuring XR spaces for the individual use cases could be supported by task taxonomies that describe which collaborator needs to perform which actions and needs to access which parts of the joint space. Establishing task taxonomies for the individual use cases would also highlight which tasks are relevant in multiple use cases such that future research efforts can be prioritized accordingly.

■Training Programs. XR spaces are meant to serve as very flexible long-time working environments that allow each user to easily switch between different technologies. Hence, once XR spaces are ready to be applied in practice, appropriate training methodologies will be needed for the different use cases, technologies, and users with different levels of expertise.

4.2. Scalability between Different Devices

■Intuitiveness. To enhance scalability between HMDs and HHDs, users should be provided with visualization and interaction techniques that remain intuitive to them when switching between these devices. To this end, it should be researched which kind of mapping between interaction techniques for 2D and 3D displays is perceived as intuitive. In particular, it needs to be investigated whether and how intuitiveness is affected by previous experiences and well-known, established interaction paradigms. For instance, certain touch-based interaction techniques are internalized by many people using smartphones in their everyday lives. As such, it remains to be researched whether modifying these interaction techniques, in a way that objectively may appear more intuitive, would confuse rather than support them.

■Interpreting Sensor Data. In order to implement collaboration support features, previous research took use of sensors incorporated in XR devices such as the orientation of HMDs to render gaze rays. While the orientation of HHDs can also be obtained by incorporated sensors, it should be noted that an HHD’s orientation does not always correspond to the user’s actual gaze direction. Hence, transferring collaboration support features that are implemented for a specific device to a different device is not straightforward and could cause misunderstandings. To prevent them, future research should also focus on how available data are to be interpreted in the context of different use cases.

■Input and Output Mapping. The mapping of input and output between HMDs and HHDs should be designed based on newly gained insights concerning intuitiveness, the interpretation of sensor data, and established task taxonomies. Thus, available input modalities of the different devices should be exploited in a way that allows the user to intuitively enter information with HMDs and HHDs. Hereby, the design of output mapping should take into account varying display sizes. As pointed out by multiple authors, using small displays can either cause occlusion when large virtual augmentations are rendered on small screens or impede the detection of virtual augmentations when they are not captured by their limited field of view. Hence, it needs to be investigated whether and how augmentations can be adapted to the display size.

4.3. Scalability between Different Degrees of Virtuality

■Visual Quality. To achieve optimal usability, future research should also focus on the trade-off between visual quality and latency. In this context, it should be investigated which parts of a physical scene need to be reconstructed at which time intervals. For instance, in large XR spaces, real-time reconstruction might not be necessary for the entire scene but only for particular parts. As such, reducing the overall amount of processed data could help to enhance the visual quality of particular areas.

■Scalable Reconstruction Techniques. In the previous section, we presented a variety of existing techniques for reconstructing physical scenes along with their individual advantages and drawbacks. Considering the practical adoption of these techniques, physical scenes might differ according to surface materials, lightning conditions, and size such that different reconstruction techniques are appropriate for different kinds of environments. To foster scalability, further research should be dedicated to developing reconstruction techniques that are applicable to a variety of physical scenes.

■Bidirectional Interaction. Previous research focused rather separately on the reconstruction and semantic segmentation of physical scenes that are either static or dynamic. As such, future research should take into account the integration of existing findings in these different research fields to provide consistent and accessible visualizations that allow bidirectional interaction (i.e., both on-site and off-site collaborators should be able to reference and manipulate certain parts in the XR space).

4.4. Scalability between Different Numbers of Collaborators

■Access Control. Access control features implemented by previous research include simultaneous manipulation via the multiplication of transformation matrices as well as locking objects for all but one collaborator. Considering an increasing number of collaborators, simultaneous manipulation could lead to objects being moved, rotated, or translated too far. Consequently, they have to be manipulated back and forth, which could impede collaboration rather than support it. Hence, it should be evaluated for what amount of collaborators simultaneous manipulation is feasible and in which cases ownership should be given to single collaborators.

■Viewpoint-Independent Augmentations. An increasing number of collaborators, especially in co-located settings, will no longer be allowed to stand next to each other, having more or less the same perspective of the XR scene. Instead, they might gather around virtual augmentations in circles, facing virtual augmentations from different perspectives. To avoid misunderstandings and maintain collaboration support, it needs to be investigated how visualizations can be adjusted in a way that allows collaborators to access the virtual objects from different perspectives.

■Awareness Cues. Previous research proposed different kinds of awareness cues indicating what collaborators do or where they are located in space. However, the majority of reviewed user studies were limited to two collaborators. Considering settings that include multiple collaborators, rendering awareness cues such as gaze rays for all collaborators at once is likely to produce visual clutter, which may increase cognitive load. To avoid cognitive overload while maintaining optimal performance, each collaborator should be provided with those awareness cues delivering the information needed for task completion. Since tasks and cognitive load may vary strongly among collaborators, rendering individual views for each collaborator should be taken into consideration.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we introduce the concept of XR spaces scaling between different degrees of virtuality, different devices, and different numbers of possibly distributed users. We believe that increasing scalability holds great potential to enhance the practical adoption of XR technologies, as such highly flexible long-time training or working environments are expected to reduce costs and enhance memorability. However, developing such applications is not straightforward and involves interdisciplinary research. In fact, we consider the following topics to be the most relevant research fields for developing XR spaces: (1) collaboration support features such as access control, as well as awareness cues that indicate where the other collaborators are and what they do; (2) consistent and accessible visualizations incorporating the semantic segmentation of virtually reconstructed physical scenes; (3) interaction techniques for selection, manipulation, and navigation in XR that remain intuitive to the users even when they switch between devices or degrees of virtuality.

While so far these topics have been investigated rather separately, we propose to integrate the outcomes of previous works to enhance scalability. Developing XR spaces is related to several independent research fields that existed long before the emergence of XR technologies. In this paper, we focus on the most recent research papers in these fields dealing with AR, MR, or VR applications. Thus, as a first step towards building XR spaces, we review related work and highlight challenges arising upon the integration of previous research outcomes. Based on this, we propose an agenda of highly relevant questions that should be addressed by future research in order to build XR spaces that fully exploit the potential inherent in XR technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M.M. and A.E.; references—selection and review, V.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M.M.; writing—review and editing, V.M.M. and A.E.; visualization, V.M.M.; project administration, A.E.; funding acquisition, A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—252408385—IRTG 2057.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AR | Augmented reality |

| AV | Augmented virtuality |

| DoFs | Degrees of freedom |

| HMD | Head-mounted display |

| HHD | Handheld display |

| IMU | Inertial measurement unit |

| MR | Mixed reality |

| VR | Virtual reality |

| XR | Extended or cross reality |

| XR | Scalable extended reality |

References

- Milgram, P.; Kishino, F. A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 1994, 77, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Milgram, P.; Takemura, H.; Utsumi, A.; Kishino, F. Augmented Reality: A class of displays on the reality-virtuality continuum. In Telemanipulator and Telepresence Technologies; Das, H., Ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1995; Volume 2351, pp. 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iPad Pro. Available online: https://www.apple.com/ipad-pro/ (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- VIVE Pro Series. Available online: https://www.vive.com/us/product/#pro%20series (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Oculus Headsets. Available online: https://www.oculus.com/compare/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- HoloLens 2. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/hololens/hardware (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Magic Leap. Available online: https://www.magicleap.com/en-us/magic-leap-1 (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Glass. Available online: https://www.google.com/glass/tech-specs/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Perry, T.S. Look Out for Apple’s AR Glasses: With head-up displays, cameras, inertial sensors, and lidar on board, Apple’s augmented-reality glasses could redefine wearables. IEEE Spectr. 2021, 58, 26–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leap Motion Controller. Available online: https://www.ultraleap.com/product/leap-motion-controller/ (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Johansen, R. Teams for tomorrow (groupware). In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, 8–11 January 1991; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1991; Volume 3, pp. 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, T.; Houben, S. CollabAR—Investigating the Mediating Role of Mobile AR Interfaces on Co-Located Group Collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, J.G.; Debarba, H.G.; Bemdt, I.; Nedel, L.; Maciel, A. Design and Assessment of a Collaborative 3D Interaction Technique for Handheld Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Tuebingen/Reutlingen, Germany, 18–22 March 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Sasikumar, P.; Yang, J.; Billinghurst, M. A User Study on Mixed Reality Remote Collaboration with Eye Gaze and Hand Gesture Sharing. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Alem, L.; Tecchia, F.; Duh, H.B.L. Augmented 3D hands: A gesture-based mixed reality system for distributed collaboration. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2018, 12, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, G.; Huang, W.; Kim, H.; Woo, W.; Billinghurst, M. Evaluating the Combination of Visual Communication Cues for HMD-based Mixed Reality Remote Collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.A.; Teo, T.; Kim, S.; Billinghurst, M. A User Study on MR Remote Collaboration Using Live 360 Video. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Munich, Germany, 16–20 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pace, F.; Manuri, F.; Sanna, A.; Zappia, D. A Comparison between Two Different Approaches for a Collaborative Mixed-Virtual Environment in Industrial Maintenance. Front. Robot. AI 2019, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pereira, V.; Matos, T.; Rodrigues, R.; Nóbrega, R.; Jacob, J. Extended Reality Framework for Remote Collaborative Interactions in Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Graphics and Interaction (ICGI), Faro, Portugal, 21–22 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piumsomboon, T.; Lee, G.A.; Hart, J.D.; Ens, B.; Lindeman, R.W.; Thomas, B.H.; Billinghurst, M. Mini-Me: An Adaptive Avatar for Mixed Reality Remote Collaboration. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piumsomboon, T.; Lee, G.A.; Irlitti, A.; Ens, B.; Thomas, B.H.; Billinghurst, M. On the Shoulder of the Giant: A Multi-Scale Mixed Reality Collaboration with 360 Video Sharing and Tangible Interaction. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.; Hayati, A.F.; Lee, G.A.; Billinghurst, M.; Adcock, M. A Technique for Mixed Reality Remote Collaboration using 360 Panoramas in 3D Reconstructed Scenes. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, Parramatta, NSW, Australia, 12–15 November 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, S.; White, D. Multi-Device Collaboration in Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Virtual and Augmented Reality Simulations, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 14–16 February 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibayashi, H.; Sugiura, Y.; Sakamoto, D.; Miyata, N.; Tada, M.; Okuma, T.; Kurata, T.; Mochimaru, M.; Igarashi, T. Dollhouse VR: A Multi-View, Multi-User Collaborative Design Workspace with VR Technology. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH Asia 2015 Emerging Technologies, Kobe, Japan, 2–6 November 2015; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pereira, I.; Gimeno, J.; Pérez, M.; Portalés, C.; Casas, S. MIME: A Mixed-Space Collaborative System with Three Immersion Levels and Multiple Users. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality Adjunct (ISMAR-Adjunct), Munich, Germany, 16–20 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, D.; Jiang, W.; Wang, C.; Dingler, T.; Velloso, E.; Goncalves, J. ShadowDancXR: Body Gesture Digitization for Low-cost Extended Reality (XR) Headsets. In Proceedings of the Companion, 2020 Conference on Interactive Surfaces and Spaces, Virtual Event, Portugal, 8–11 November 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, K.; Goel, M.; Harrison, C. BodySLAM: Opportunistic User Digitization in Multi-User AR/VR Experiences. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Spatial User Interaction, Virtual Event, Canada, 30 October–1 November 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, A.; Norouzi, N.; Kim, K.; Schubert, R.; Jules, J.; LaViola, J.J., Jr.; Bruder, G.; Welch, G.F. Sharing gaze rays for visual target identification tasks in collaborative augmented reality. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2020, 14, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, P.; Mori, S.; Langlotz, T.; Thomas, B.H.; Schmalstieg, D.; Kalkofen, D. Mixed Reality Light Fields for Interactive Remote Assistance. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindlbauer, D.; Wilson, A.D. Remixed Reality: Manipulating Space and Time in Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaya, M.; Yang, K.; Christensen, T.; Li, S.; O’Keefe, M.; Fridley, J.; Sung, K. A Framework for analyzing AR/VR Collaborations: An initial result. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Virtual Environments for Measurement Systems and Applications (CIVEMSA), Annecy, France, 26–28 June 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.; Lawrence, L.; Lee, G.A.; Billinghurst, M.; Adcock, M. Mixed Reality Remote Collaboration Combining 360 Video and 3D Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T.; Norman, M.; Lee, G.A.; Billinghurst, M.; Adcock, M. Exploring interaction techniques for 360 panoramas inside a 3D reconstructed scene for mixed reality remote collaboration. J. Multimodal User Interfaces 2020, 14, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stotko, P.; Krumpen, S.; Hullin, M.B.; Weinmann, M.; Klein, R. SLAMCast: Large-Scale, Real-Time 3D Reconstruction and Streaming for Immersive Multi-Client Live Telepresence. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2019, 25, 2102–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jeršov, S.; Tepljakov, A. Digital Twins in Extended Reality for Control System Applications. In Proceedings of the 2020 43rd International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Milan, Italy, 7–9 July 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütt, P.; Schwarz, M.; Behnke, S. Semantic Interaction in Augmented Reality Environments for Microsoft HoloLens. In Proceedings of the 2019 European Conference on Mobile Robots (ECMR), Prague, Czech Republic, 4–6 September 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A.; Chang, A.X.; Savva, M.; Halber, M.; Funkhouser, T.; Nießner, M. ScanNet: Richly-Annotated 3D Reconstructions of Indoor Scenes. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 2432–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, S.S.; Ma, Z.Y.; Mu, T.J.; Fu, H.; Hu, S.M. Supervoxel Convolution for Online 3D Semantic Segmentation. ACM Trans. Graph. 2021, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauglitz, S.; Lee, C.; Turk, M.; Höllerer, T. Integrating the physical environment into mobile remote collaboration. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services, San Francisco, CA, USA, 21–24 September 2012; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gauglitz, S.; Nuernberger, B.; Turk, M.; Höllerer, T. In Touch with the Remote World: Remote Collaboration with Augmented Reality Drawings and Virtual Navigation. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, Edinburgh, UK, 11–13 November 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauglitz, S.; Nuernberger, B.; Turk, M.; Höllerer, T. World-stabilized annotations and virtual scene navigation for remote collaboration. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, Honolulu, HI, USA, 5–8 October 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nuernberger, B.; Lien, K.C.; Grinta, L.; Sweeney, C.; Turk, M.; Höllerer, T. Multi-view gesture annotations in image-based 3D reconstructed scenes. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Conference on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, Munich, Germany, 2–4 November 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nuernberger, B.; Lien, K.C.; Höllerer, T.; Turk, M. Interpreting 2D gesture annotations in 3D augmented reality. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Symposium on 3D User Interfaces (3DUI), Greenville, SC, USA, 19–20 March 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, K.C.; Nuernberger, B.; Höllerer, T.; Turk, M. PPV: Pixel-Point-Volume Segmentation for Object Referencing in Collaborative Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Merida, Mexico, 19–23 September 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, F.; Woźniak, P.W.; Biener, V.; Knierim, P.; Schmidt, A. VUM: Understanding Requirements for a Virtual Ubiquitous Microscope. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, Essen, Germany, 22–25 November 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Nuernberger, B.; Luan, B.; Höllerer, T. Evaluating gesture-based augmented reality annotation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium on 3D User Interfaces (3DUI), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 18–19 March 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surale, H.B.; Matulic, F.; Vogel, D. Experimental Analysis of Barehand Mid-air Mode-Switching Techniques in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaconas, N.; Höllerer, T. An Evaluation of Bimanual Gestures on the Microsoft HoloLens. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Tuebingen/Reutlingen, Germany, 18–22 March 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwind, V.; Mayer, S.; Comeau-Vermeersch, A.; Schweigert, R.; Henze, N. Up to the Finger Tip: The Effect of Avatars on Mid-Air Pointing Accuracy in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 28–31 October 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasier, E.; Chapuis, O.; Ferey, N.; Vezien, J.; Appert, C. ARPads: Mid-air Indirect Input for Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR), Porto de Galinhas, Brazil, 9–13 November 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satriadi, K.A.; Ens, B.; Cordeil, M.; Jenny, B.; Czauderna, T.; Willett, W. Augmented Reality Map Navigation with Freehand Gestures. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Osaka, Japan, 23–27 March 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- von Willich, J.; Schmitz, M.; Müller, F.; Schmitt, D.; Mühlhäuser, M. Podoportation: Foot-Based Locomotion in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, F.; McManus, J.; Günther, S.; Schmitz, M.; Mühlhäuser, M.; Funk, M. Mind the Tap: Assessing Foot-Taps for Interacting with Head-Mounted Displays. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botev, J.; Mayer, J.; Rothkugel, S. Immersive mixed reality object interaction for collaborative context-aware mobile training and exploration. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM Workshop on Immersive Mixed and Virtual Environment Systems, Amherst, MA, USA, 18 June 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biener, V.; Schneider, D.; Gesslein, T.; Otte, A.; Kuth, B.; Kristensson, P.O.; Ofek, E.; Pahud, M.; Grubert, J. Breaking the Screen: Interaction Across Touchscreen Boundaries in Virtual Reality for Mobile Knowledge Workers. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2020, 26, 3490–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ro, H.; Byun, J.H.; Park, Y.J.; Lee, N.K.; Han, T.D. AR Pointer: Advanced Ray-Casting Interface Using Laser Pointer Metaphor for Object Manipulation in 3D Augmented Reality Environment. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, L.H.; Zhu, Y.; Yau, Y.P.; Braud, T.; Su, X.; Hui, P. One-thumb Text Acquisition on Force-assisted Miniature Interfaces for Mobile Headsets. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications (PerCom), Austin, TX, USA, 23–27 March 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Katsuragawa, K.; Lank, E. Understanding Viewport- and World-based Pointing with Everyday Smart Devices in Immersive Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuvattanasilp, V.; Fujimoto, Y.; Plopski, A.; Taketomi, T.; Sandor, C.; Kanbara, M.; Kato, H. SlidAR+: Gravity-aware 3D object manipulation for handheld augmented reality. Comput. Graph. 2021, 95, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozgeyikli, E.; Bozgeyikli, L.L. Evaluating Object Manipulation Interaction Techniques in Mixed Reality: Tangible User Interfaces and Gesture. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR), Lisboa, Portugal, 27 March–1 April 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besançon, L.; Sereno, M.; Yu, L.; Ammi, M.; Isenberg, T. Hybrid Touch/Tangible Spatial 3D Data Selection. Comput. Graph. Forum 2019, 38, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wacker, P.; Nowak, O.; Voelker, S.; Borchers, J. ARPen: Mid-Air Object Manipulation Techniques for a Bimanual AR System with Pen & Smartphone. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukarinen, T.; Kangas, J.; Rantala, J.; Koskinen, O.; Raisamo, R. Evaluating ray casting and two gaze-based pointing techniques for object selection in virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, Tokyo, Japan, 28 November–1 December 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bâce, M.; Leppänen, T.; de Gomez, D.G.; Gomez, A.R. ubiGaze: Ubiquitous Augmented Reality Messaging Using Gaze Gestures. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH ASIA 2016 Mobile Graphics and Interactive Applications, Macau, 5–8 December 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hassoumi, A.; Hurter, C. Eye Gesture in a Mixed Reality Environment. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications—HUCAPP, Prague, Czech Republic, 25–27 February 2019; pp. 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikkert, W.; D’Ambros, M.; Bierz, T.; Jankun-Kelly, T.J. Interacting with Visualizations. In Proceedings of the Human-Centered Visualization Environments: GI-Dagstuhl Research Seminar, Dagstuhl Castle, Germany, 5–8 March 2006; Revised Lectures. Kerren, A., Ebert, A., Meyer, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 77–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahayfeh, A.; Faezipour, M. Eye Tracking and Head Movement Detection: A State-of-Art Survey. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2013, 1, 2100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).