1. Introduction

Kubernetes (K8s) is considered the industry standard for orchestrating containerized applications, offering a powerful abstraction for automating deployment, scaling, and lifecycle management across distributed environments. Edge-focused Kubernetes distributions, such as K3s and MicroK8s, are specifically designed to operate efficiently on resource-constrained devices, allowing container orchestration with minimal overhead. K8s also effectively handles deployment, update, and management across distributed edge locations from a central control plane. The extent of K8s utilization in enterprise and edge–cloud infrastructures triggers the demand for robust security measures against an evolving threat landscape that strikes at the core of container orchestration vulnerabilities, including misconfigurations, privilege escalation, and network-based attacks. However, the implementation of these security measures typically results in CPU and memory overhead, which can increase the energy consumption of the underlying infrastructure. Data centers have already been under pressure to reduce their energy footprint [

1], a demand even more pressing at the edge, where devices are resource- and power-constrained and often battery-powered, especially if they provide AI capabilities [

2]. These pressures motivate intelligent mechanisms and techniques that consider security, performance, cost, and energy efficiency across the edge–cloud continuum.

Despite the critical importance of both security and energy consumption—especially in the cloud–edge–IoT and smart city context—they are frequently addressed independently, with little consideration of their interaction. For instance, a cluster hardened according to strict security standards may be more resilient against attacks but also potentially less energy- and resource-efficient than one operating with relaxed configurations, particularly when scaled across multiple locations and nodes. Therefore, understanding and managing this security–energy trade-off is essential, particularly in edge deployments that serve as primary data producers within sensor and IoT ecosystems.

Several research papers investigate energy consumption in smart cities, from macro-level surveys [

3,

4] to system designs [

5,

6]. While this work focuses primarily on K8s-based cloud-native environments, its insights also extend to the design and optimization of distributed edge and smart city ecosystems. In such domains, there is a continuous need to study and balance security assurance with strict energy constraints [

7]. Understanding how security mechanisms influence power consumption at scale can therefore guide the development of more efficient protection strategies in energy-limited contexts. Techniques such as lightweight encryption, selective telemetry, and adaptive security provisioning—explored in cloud-native systems—can be adapted to enhance the resilience and sustainability of such deployments. Thus, although this paper appears peripheral in scope, it contributes critically to understanding the energy–security trade-offs that are central to resource-constrained and smart city workloads.

In this work, we aim to fill the security–energy trade-off gap by quantifying the energy overhead of various K8s security mechanisms and assessing how hardening techniques affect cluster-level energy consumption under diverse workload scenarios. Our study offers several contributions to the broader field of cloud-native security and sustainability.

We identify and analyze the interplay between security and energy efficiency in K8s environments.

We implement and evaluate a range of common K8s security mechanisms, providing insights into their impact on energy consumption.

We investigate diverse cluster operating conditions, including a realistic, containerized e-commerce workload with reproducible load generation and observability to measure the security–energy interactions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the necessary background to clarify the context of our work, while

Section 3 discusses the existing literature in K8s security, energy and performance evaluation.

Section 4 explains the experimentation methodology and

Section 5 details our experiment results. Lastly,

Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines potential directions for future work.

2. Background

K8s deployments integrate multiple layers of security and networking components, such as service meshes, kernel-level observability, runtime enforcement, and encrypted network overlays, each of which influences the overall power profile of a cluster. Understanding the energy–security trade-off requires evaluating how these mechanisms interact with typical workloads and how their operation translates into measurable energy overhead. In sensor- or IoT-oriented deployments, these trade-offs become particularly critical. Gateways and edge nodes often manage streams of sensor data under tight power and latency constraints, while the orchestration of secure communication, processing, and data aggregation for thousands of distributed IoT devices must balance protection levels with minimal energy impact to sustain continuous sensing operations.

In the following subsections, we examine the key categories that define this relationship: traffic encryption, which secures communication between cluster entities; runtime security, which monitors event streams and checks for anomalies; network security monitoring, which provides visibility into network flows and threats; vulnerability scanning, which identifies weaknesses and misconfigurations; and energy observability, which links power metrics to K8s resources to enable quantifiable comparisons.

2.1. Traffic Encryption

In IoT environments, encrypted communication channels are critical for securing telemetry from sensors and edge devices—such as environmental sensors, surveillance cameras, or industrial controllers. However, encryption adds computational load to constrained gateways. Measuring this additional cost helps quantify how securing sensor data streams influences node-level energy consumption and overall system sustainability. In a K8s cluster, traffic between nodes or pods may not be encrypted by default, unless the underlying network plugin supports it. Traffic encryption can be applied at multiple layers to mitigate eavesdropping, tampering, and Man-in-the-Middle attacks, thereby ensuring secure data transfer, confidentiality, and integrity of inter-node communications. At the network layer, protocols such as IPsec and kernel-integrated Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) provide node-to-node tunnels, with several Container Network Interfaces (CNIs) such as Calico and Cilium supporting optional IPsec or WireGuard for cluster-wide encryption. WireGuard provides a high-performance, encrypted overlay network that is frequently leveraged in cloud-native environments to secure inter-node traffic. It operates as an efficient VPN protocol integrated directly into the Linux kernel, establishing secure tunnels by utilizing state-of-the-art cryptographic primitives (e.g., ChaCha20Poly1305 and Curve25519) [

8]. For multi-cluster connectivity, tools such as Submariner (

https://submariner.io (accessed on 3 December 2025)) establish encrypted interconnects across clusters. At the transport and application layers, service meshes (e.g., Istio (

https://istio.io/ (accessed on 3 December 2025)) and Linkerd (

https://linkerd.io/ (accessed on 3 December 2025))) provide cluster-wide mutual TLS (mTLS), per-flow confidentiality, integrity, and peer authentication, while automating certificate issuance and rotation, authorization policies, and observability. While these capabilities greatly strengthen security with minimal application changes, they also introduce proxy and control-plane overhead, which can impact performance (e.g., latency and throughput) and energy consumption.

2.2. Runtime Security

Runtime security helps detect signs of sensor compromise by monitoring suspicious behavior. However, enabling continuous monitoring across hundreds of lightweight sensor data streams can significantly increase CPU utilization and energy draw—an important consideration for edge nodes powered by limited energy sources, such as solar or battery systems. In containerized environments, runtime security focuses on detecting and responding to suspicious behavior as software executes, providing continuous, host-level visibility into system activity. Typical mechanisms capture kernel events (syscalls, file, and network activity) and evaluate them against predefined rules or policies to identify anomalies and policy violations in real time. Depending on configuration, responses may include alerting, process termination, syscall blocking, or file access denial, thereby enforcing runtime integrity. Representative open-source tools include eBPF-based solutions for low-overhead visibility and control. Tools such as Falco (

https://falco.org/ (accessed on 3 December 2025)), Cilium Tetragon (

https://tetragon.io/ (accessed on 3 December 2025)), and Aqua Tracee (

https://www.aquasec.com/products/tracee/ (accessed on 3 December 2025)) monitor kernel activity (e.g., via eBPF or probes), enrich captured events with workload metadata, and evaluate them against rulesets. While these solutions enhance observability and security posture, they also introduce measurable resource and energy overhead, as each node expends CPU cycles on continuous event capture, parsing, and rule evaluation. The magnitude of this overhead scales with event frequency, rule complexity, and logging volume. In this context, eBPF-based probes act as fine-grained software sensors embedded in the kernel, generating detailed event data that can be correlated with physical power measurements.

2.3. Network Security Monitoring

Network security monitoring provides visibility into traffic patterns, protocol behavior, and potential misuse by transforming packet streams into analyzable logs. In sensor-based or IoT deployments, network security monitoring helps identify compromised devices or abnormal communication patterns, such as unexpected data surges from a sensor or rogue devices injecting false readings. Unlike signature-only intrusion detection, modern monitoring emphasizes protocol-aware context, enabling operators to detect policy violations, data exfiltration, and suspicious network behavior. In K8s, where traffic is highly ephemeral and often short-lived, monitoring is particularly valuable for reconstructing service interactions and detecting anomalies that may not appear in application-level logs. Data sources can range from packet capture for deep forensics to protocol or transaction logs and flow telemetry. In K8s, sensors run as DaemonSets on nodes or tap traffic via CNI port mirroring. Representative tools include Zeek (

https://zeek.org/ (accessed on 3 December 2025)), which parses end-to-end protocols and generates structured logs integrated with Security Information and Event Management (SIEM)/data systems, supporting real-time alerting and offline forensics. In addition, Cilium Hubble (

https://github.com/cilium/hubble (accessed on 3 December 2025)) records L3–L7 flow telemetry with network policy awareness, while Calico flow logs offer policy-aware visibility within Calico-managed clusters. Lastly, Kubeshark (

https://www.kubeshark.co/ (accessed on 3 December 2025)) is a K8s-native network observability tool that captures traffic and reconstructs application protocols. It supports network security monitoring through lightweight agents that enable anomaly detection and policy enforcement; however, since it is not a full signature-based intrusion detection system (IDS), it is typically deployed alongside such tools to achieve defense in depth.

2.4. Vulnerability Scanning

In cloud-native environments, vulnerability scanning complements runtime defenses by identifying known weaknesses before and after deployment. Scanners analyze container images, OS packages, language dependencies, and configuration artifacts to match versions against vulnerability databases, often alongside checks for misconfigurations and exposed secrets. Their primary goal is to surface actionable risks early and keep running workloads continuously assessed as new CVEs are published. Two of the most popular tools are Trivy (

https://trivy.dev/ (accessed on 3 December 2025)) and Grype/Syft (

https://github.com/anchore/grype (accessed on 3 December 2025)), which provide scanning of container images, filesystems, and K8s manifests or Helm charts. The Trivy Operator extends these capabilities into the K8s control loop by automatically discovering workloads, scanning their images, and storing results as custom resources. Similarly, Kubescape (

https://kubescape.io/ (accessed on 3 December 2025)) integrates with K8s clusters to assess configuration compliance and perform in-cluster image scanning using Grype. Both operators support scheduled and on-demand scans, offering configurable throttling to balance resource utilization and result freshness.

Beyond scanning for vulnerabilities and misconfigurations, K8s hardening guidance such as the CIS K8s Benchmark [

9] and NSA/CISA K8s Hardening Guide [

10] emphasize reducing the attack surface, enforcing strong authentication, least-privilege Role-Based Access Control (RBAC), encryption of data in transit and at rest, traffic isolation, network policies, and many more techniques and configurations. Many of these controls offer minimal runtime cost, whereas security measures such as mesh-wide encryption, runtime telemetry, and frequent in-cluster scans incur noticeable overhead—therefore their scope should be tuned to balance security and energy constraints, especially in edge and IoT contexts.

2.5. Energy Observability

Accurate energy measurement is a prerequisite for analyzing the trade-offs between security and efficiency. Energy observability can be achieved by correlating power consumption with the workloads that generate it, e.g., across nodes, pods, and services, thus enabling quantification of the energy cost introduced by specific security and networking mechanisms. Energy attribution methods are typically either sensor-driven, using hardware interfaces such as RAPL or NVML to obtain real-time power readings, or model-based, where power models map performance counters (e.g., CPU cycles, instructions, and cache misses) to estimated energy on the target hardware [

11]. Tools like Kepler (Kubernetes-based Efficient Power Level Exporter) [

12] combine both approaches, leveraging hardware sensors when available and relying on validated power models otherwise to estimate per-container and per-node energy use. In contrast, Scaphandre (

https://hubblo-org.github.io/scaphandre/ (accessed on 3 December 2025)) focuses exclusively on hardware energy counters via the Linux powercap/RAPL interface, estimating total system power by combining these readings with per-process CPU accounting and resource utilization metrics [

13].

3. Related Work

Recent studies tackle energy in K8s environments along two primary fronts: (i) attribution/measurement and (ii) energy-aware control.

Table 1 summarizes representative studies across these categories, highlighting their domains, techniques, platforms, and key findings. For attribution, tools such as Kepler estimate per-pod/container/cluster power by combining hardware telemetry with eBPF counters and energy models, reporting low error [

12]. In this context, Pijnacker et al. [

14] evaluate Kepler’s container attribution against iDRAC/Redfish ground truth and report misattribution patterns, concluding that container-level accuracy is not yet satisfactory; they then introduce KubeWatt, which splits static/dynamic power from Redfish and redistributes dynamic power by CPU usage, validating low node-level error on their testbed while cautioning against fine-grained container accuracy. Werner et al. [

15] present an automated experimentation framework for K8s that quantifies energy efficiency trade-offs of architectural choices (Microservice as baseline, Monolith, Serverless, Service Reduction, and Runtime Improvement) across the cloud-native stack and evaluate its functionality with the deployment of a realistic workload. Findings show that in terms of energy, Runtime Improvement delivered the most consistent energy win with lower energy per request across workloads, while the Serverless variant increased energy usage due to added platform overhead.

On the energy-aware control side, Kaur et al. [

16] introduce KEIDS, a K8s scheduler for edge–cloud that optimizes energy with interference/carbon objectives and shows improvement over baseline placements. Rao & Li [

17] present EA-K8S, which uses an improved Sparrow Search Algorithm (ISSA) to place high consumption/communicative microservices on nodes with low power usage effectiveness to reduce energy consumption, achieving an energy reduction of ∼5–6%. Beena et al. [

18] integrate Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and hardware-level Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling (DVFS) algorithms with K8s autoscaling and lifecycle control (ARAA/ARKLM). Reported results show DVFS achieving the lowest average CPU (

) while ACO yields the fastest completion at higher CPU consumption, highlighting a speed–resource trade-off. A recent serverless edge design, FaasHouse, augments k3s/OpenFaaS with an energy-aware function scheduler that monitors each node’s state of charge (SoC) and capacity and then offloads functions from low-powered to well-powered nodes. Placement is scored via pluggable policies and solved with a House-Allocation-style assignment to respect capacity and prioritize local tenants. It is implemented on a 10-node Raspberry Pi edge cluster and evaluated in a 24 h experiment. Regarding energy, results show a 76% reduction in wasted energy compared to K8s [

6]. Ali & Sofia [

19] propose including energy-awareness in K8s orchestration along the edge–cloud continuum using the CODECO framework. The PDLC-CA component collects node and network energy metrics based on proposed aggregated cost functions in order to score nodes on different performance profiles and feed recommendations to the scheduler. The experiments took place on a k3s testbed (laptop master + Raspberry Pi 4 workers) with Kepler-based estimates and JMeter loads. Results show that energy-aware scheduling generally reduced total energy compared to vanilla K8s, especially under high load intensity.

Smart city platforms push computation from the cloud to fog/edge to meet strict latency and cost constraints, making energy-efficient orchestration a major concern. Recent fog architectures adopt K8s to place microservices across the edge/fog/cloud. For example, the Adaptive Fog Computing Architecture (AFCA) deploys microservices on K8s, adding a Context-Aware Decision Engine and a Resource Orchestration Layer for load steering and prediction based on Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM). Evaluated on smart parking, pollution, and traffic datasets in a hybrid testbed including Raspberry Pi edge nodes, Intel NUC fog servers, and AWS-hosted cloud instances, AFCA reports 31% energy efficiency [

5].

Focusing on security and resource overhead trade-offs in containerized environments, Koukis et al. [

20] conduct a comparative study of five CNI plugins across vanilla K8s and MicroK8s, explicitly toggling tunneling (VXLAN/IPIP/Geneve/HostGW), security/encryption, and service mesh options (WireGuard, IPsec, eBPF, and Istio) in TCP and UDP scenarios and then reporting CPU, RAM, and throughput. They find that plugin choice dominates performance; WireGuard tends to drive the highest CPU consumption and Istio/eBPF can deliver higher throughput at comparable or lower resource usage. Kapetanidou et al. [

21] evaluate K8s vulnerability/misconfiguration scanners, comparing scan time, detections, and CPU/RAM/bandwidth usage. They report low overall overhead, with CPU usage comparable between Trivy and Kubescape operators. Trivy peaks higher in memory—attributed to storing reports as Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs)—while Kubescape consumes network bandwidth for intra-operator communication and result storage, whereas Trivy shows no network usage during scans. Overall, both operators remain resource-efficient, suitable even for constrained clusters, but they exhibit different cost profiles. Viktorsson et al. [

22] evaluate container runtimes by comparing runC, gVisor, and Kata in the same K8s cluster and show that the added isolation layers come with substantial costs: runC outperforms the hardened runtimes by up to 5x in deployment time and application execution across TeaStore, Redis, and Spark; gVisor deploys

x faster than Kata but runs applications slower. They also report negligible idle CPU overhead but a higher memory footprint (

MB for gVisor;

MB for Kata) relative to runC.

Despite the growing attention to energy consumption in edge–cloud deployments, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that measure the energy costs of network encryption, runtime monitoring, and vulnerability scanning in K8s. Most studies focus primarily on performance rather than energy costs, with limited evidence and analysis of interaction effects when these mechanisms are combined. This gap motivates an energy-centric evaluation that measures individual and combined security controls under both synthetic and realistic workloads to provide comparable and reproducible results.

4. Experimentation Setup and Methodology

This section details the experimental environment, workload design, and measurement methodology used to assess the energy impact of the selected security mechanisms. We describe the testbed configuration, the security scenarios under evaluation, the synthetic and microservice-based workloads used for evaluation, and the methodology for collecting and attributing energy telemetry.

4.1. Experimental Setup

The testbed environment is hosted on a lab server equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2630 v2 at 2.60GHz, 6-core CPU, 128GB RAM, and

TB HDD, running the XCP-ng virtualization platform (

https://xcp-ng.org/ (accessed on 3 December 2025)). The setup includes all cluster VMs, i.e., one control plane and two worker nodes, which are automatically deployed utilizing the CODECO Experimentation Framework (CODEF) [

23] to ensure consistency and reproducibility, as clusters are fully torn down and redeployed from scratch. CODEF provides an integrated framework that automates the entire experimentation workflow across cloud–edge infrastructures. It orchestrates resource provisioning, cluster setup, experiment execution, and monitoring through modular abstraction layers that build upon well-established technologies such as Docker, Ansible, Jq, and kubeadm. Each scenario is executed multiple times to ensure statistical reliability, while the full system specifications, i.e., nodes, K8s flavors, and networking, are provided in

Table 2.

4.2. Experimental Workflow and Scenarios

To evaluate the energy and security trade-offs in K8s environments, a series of controlled experiments was designed and executed on the deployed testbed. The selected tools represent widely adopted open-source solutions that cover complementary aspects of cluster protection, as summarized below:

Encryption: WireGuard and Istio (mTLS).

Runtime: Falco and Cilium Tetragon.

Network Monitoring: Zeek.

Vulnerability Scanning: Trivy.

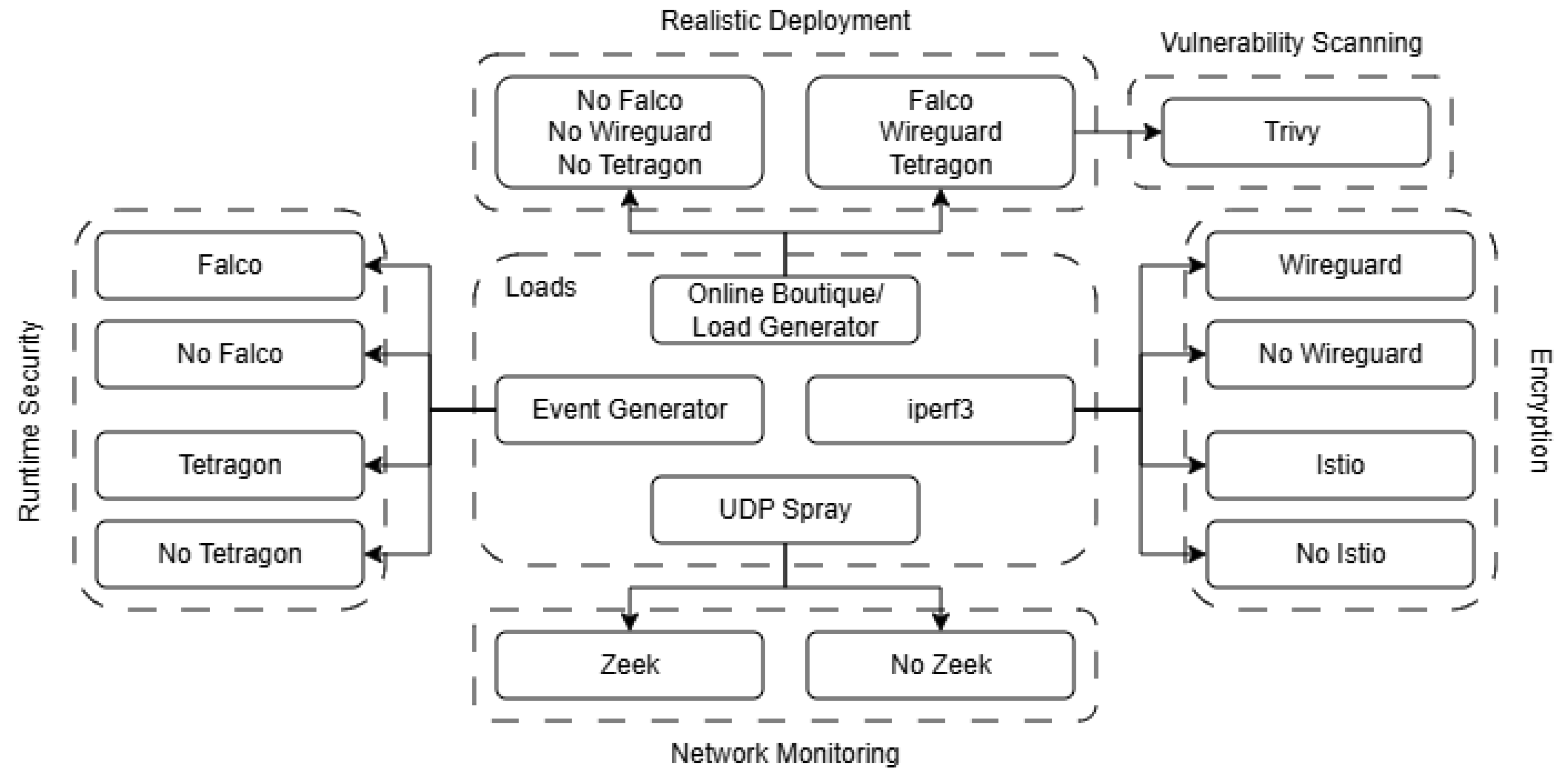

The study is conducted with security and networking scenarios evaluated both individually and in combination, as illustrated in

Figure 1. For link encryption, iperf3 over plain networking is compared against encrypted WireGuard under an identical configuration. For in-mesh encryption, Istio is deployed in sidecar mode with a

STRICT mTLS policy and evaluated against the plain networking configuration. Runtime security is toggled by enabling/disabling Falco (default ruleset) and Cilium Tetragon under the Falco Event Generator (EG). For network security monitoring, Zeek is deployed as a K8s DaemonSet on all worker nodes with the default configuration, while the UDP Spray is active. To capture interactions under realistic load, Online Boutique (OB) is deployed while selectively enabling WireGuard, Falco, and Tetragon, since real-world deployments usually combine multiple security measures to ensure the resilience of the cluster. Finally, the energy cost of vulnerability assessment (Trivy) is measured in the cluster.

4.3. Synthetic Workload and Triggering Mechanisms

The experimental workflow combines synthetic network load, runtime event generation, vulnerability scanning, and a realistic microservice-based application, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The experiments were designed to isolate and quantify the energy impact of individual and combined security mechanisms in K8s. For the synthetic network load, we utilized iperf3 (

https://github.com/esnet/iperf/ (accessed on 3 December 2025)) in TCP mode (transmitting “default” 128 KB chunks of data) between pods on separate worker nodes. To stress network security monitoring, we ran a custom “UDP spray” client with iperf3 to generate high packets-per-second traffic towards the server. For runtime detection triggering, we utilized Falco EG to produce a repeatable stream of events. In terms of microservices, the Online Boutique (

https://github.com/GoogleCloudPlatform/microservices-demo (accessed on 3 December 2025)) (OB) and its built-in traffic generator were deployed to reflect realistic communication patterns of an e-commerce application. Finally, the evaluation of preventive security was achieved by scanning the cluster with Trivy.

4.4. Energy Measurement

Energy telemetry is obtained via Kepler, exported as time-series data to Prometheus (with 5 s scrape), and inspected in Grafana to identify the appropriate aggregation functions and time windows used in the analysis. Kepler estimates energy consumption by continuously sampling low-level execution and resource usage signals from the host kernel and mapping them to power models when direct hardware energy meters are unavailable. In model-based mode, Kepler utilizes eBPF to collect performance counters and feed them to calibrated energy models that approximate the power contribution of each subsystem. The resulting estimates are integrated over time to produce monotonically increasing energy counters in Joules. Since the clusters run on VMs without hardware power sensors, Kepler operates in model-based mode. The approach depends on indirect measurements such as performance counters and resource usage metrics, making the resulting energy estimates subject to modeling errors and approximation inaccuracies, which may affect the precision of energy consumption assessments. Kepler reports cumulative energy (in Joules), with instantaneous power derived with PromQL:

The expression calculates the rate of change in the total energy consumed by the node(s) over a sliding window (e.g., 35 s), providing the system’s instantaneous power in Watts (Joules/second) with a monotonically increasing per-node energy counter, smoothed over the defined interval. This time window is selected as it provides sufficient smoothing to filter short-lived counter fluctuations while remaining responsive enough to capture transient power changes introduced by security operations.

5. Results

In this section, we present the outcomes of the experimental evaluation. We begin by establishing an idle baseline where Kepler runs with only essential platform services active and no user workload or synthetic traffic. This serves as a reference for all subsequent scenarios. We then report representative time-series results for each experiment under loaded (e.g., synthetic traffic) and realistic application workloads (with application-level traffic), illustrating the system’s energy behavior throughout the execution period. Each security configuration is compared against its corresponding baseline, enabling clear visualization of relative performance differences and energy overheads.

5.1. Encryption Consumption

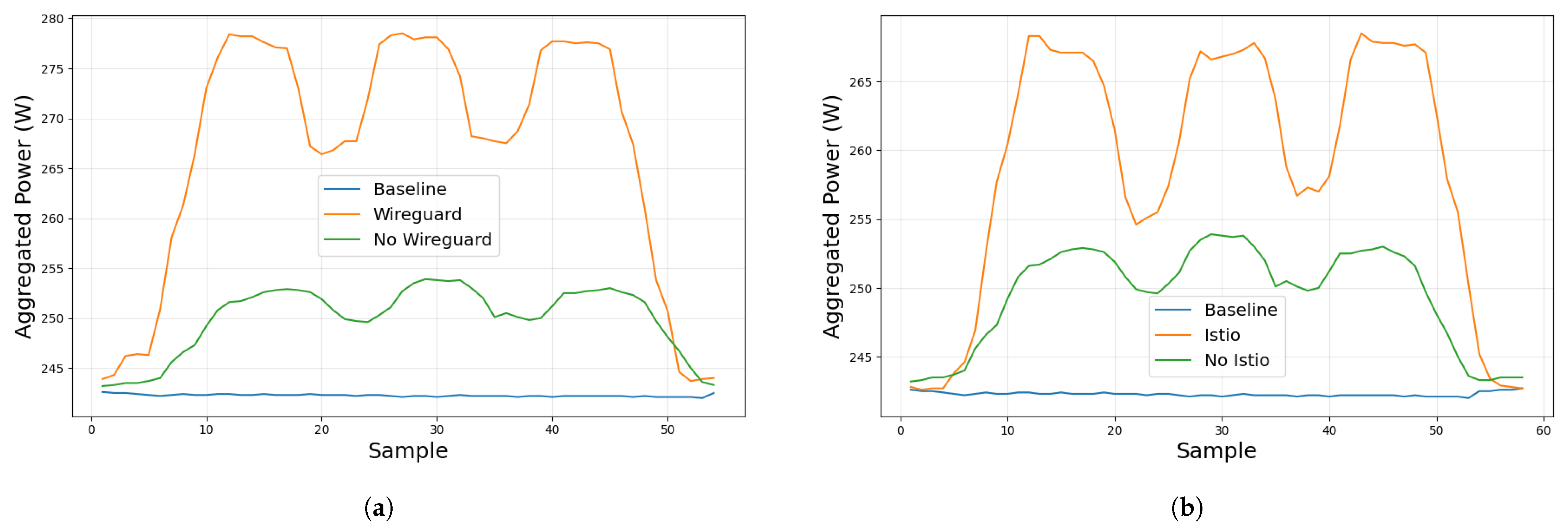

Figure 2a,b summarize the energy consumption experiments for link and mesh encryption. In both panels, the blue trace is the aforementioned idle baseline and the green trace shows iperf over plain networking.

Figure 2a compares idle, plain networking, and WireGuard. Power rises when traffic begins, plateaus during steady state, and drops. The periodic dips between plateaus occur because the iperf client is defined as a K8s job with three completions. After each completion finishes, the pod is terminated and the job is briefly deleted, so power drops; when the next completion is scheduled and the new pod spawns, traffic resumes and power rises again. A clear, persistent increase in power is observed with WireGuard relative to plain traffic, raising peak power consumption by about 25–30 W.

Regarding Istio, enabling sidecar-based strict mTLS results in a consistent increase in power relative to the no-mesh condition, mirroring the experimental procedure followed in the previous experiment.

Figure 2b shows that the increase in energy consumption is lower than that observed with WireGuard (around 15–20 W in peak, relative to plain iperf) yet remains clearly noticeable.

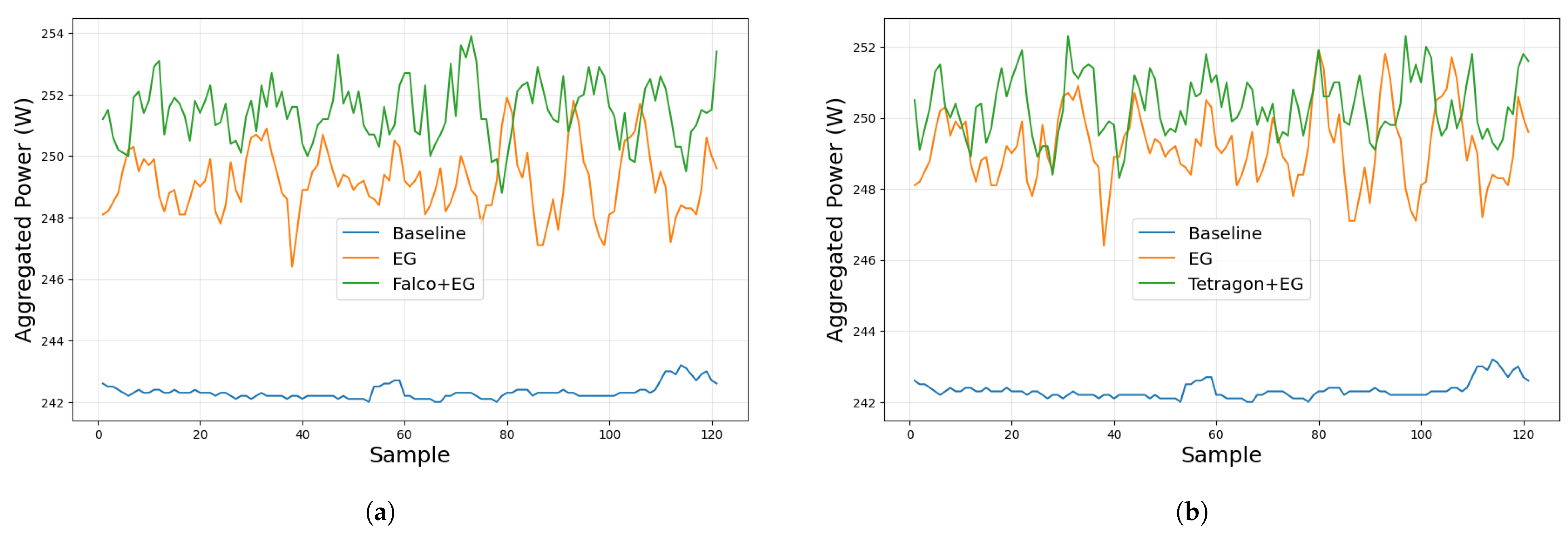

5.2. Runtime Detection Consumption

Figure 3a,b show aggregated power over time for Falco and Cilium Tetragon. The blue traces represent the idle baseline as before. Enabling the event generator alone significantly raises the power consumption (

W on average), while activating the runtime monitors increases it further, reflecting the additional work of syscall/event capture and rule evaluation. The oscillations in the orange/green traces follow the driven event rate as the event generator spawns and despawns pods that trigger Falco rules and generate logs ingested by Tetragon. Falco exhibits a noticeably higher power footprint (about

W on average) than the alternative configuration (

W). Overall, the figures indicate that always-on runtime monitoring imposes a persistent energy tax whose magnitude depends on the volume of emitted telemetry.

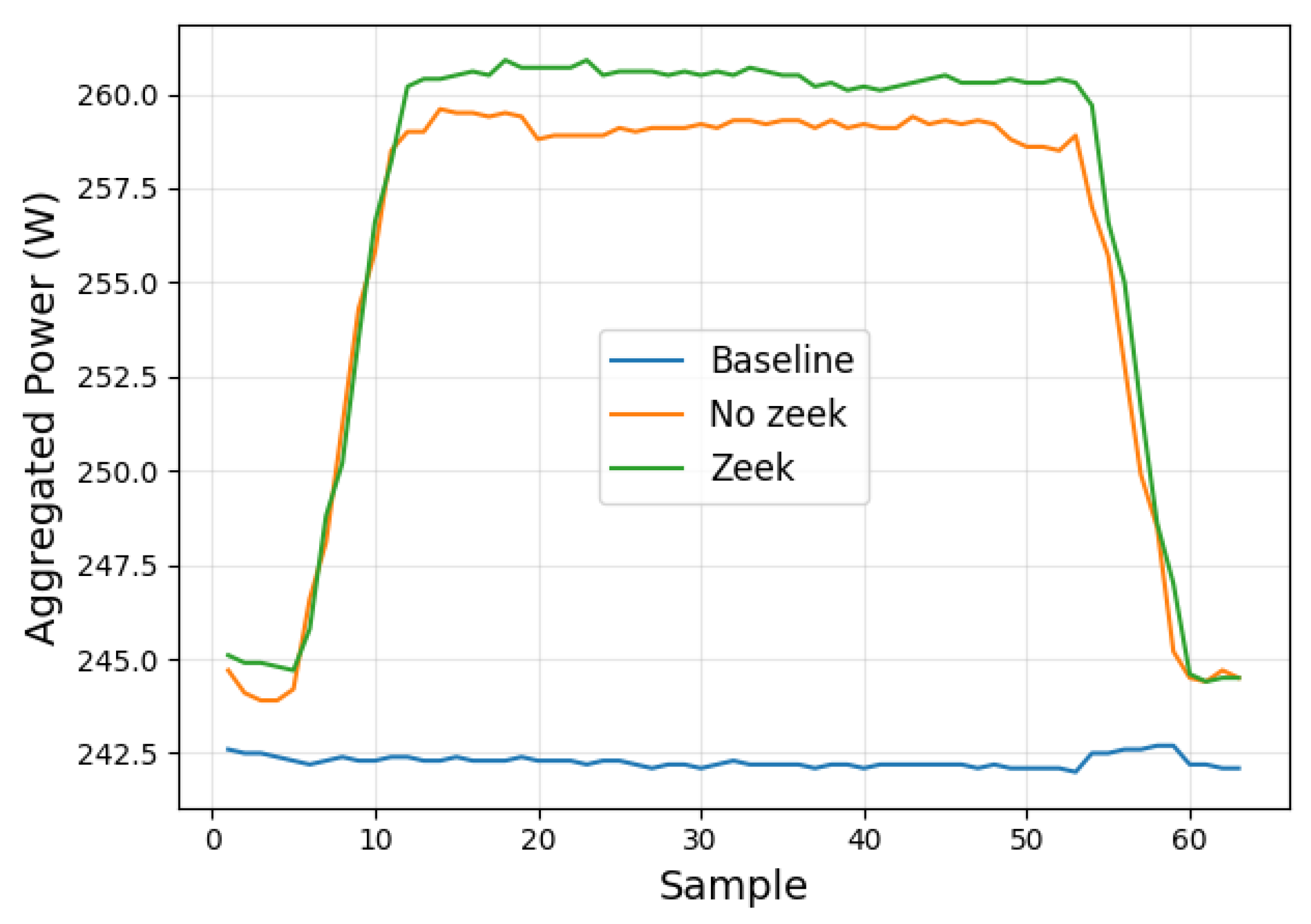

5.3. Network Security Monitoring Consumption

Figure 4 shows the difference in energy consumption between a high-rate UDP spray and the same traffic with Zeek enabled. The spray increases power to a steady plateau (orange), while enabling Zeek produces a further persistent but modest increase (

–5 W increase relative to the UDP spray without Zeek). The increment reflects the cost of packet capture and log generation. The sharp rise and fall at the edges correspond to job start/stop. Clearly, packet capture and log emission with Zeek add only a small incremental load relative to the UDP spray itself.

5.4. Energy Consumption over Realistic Workload

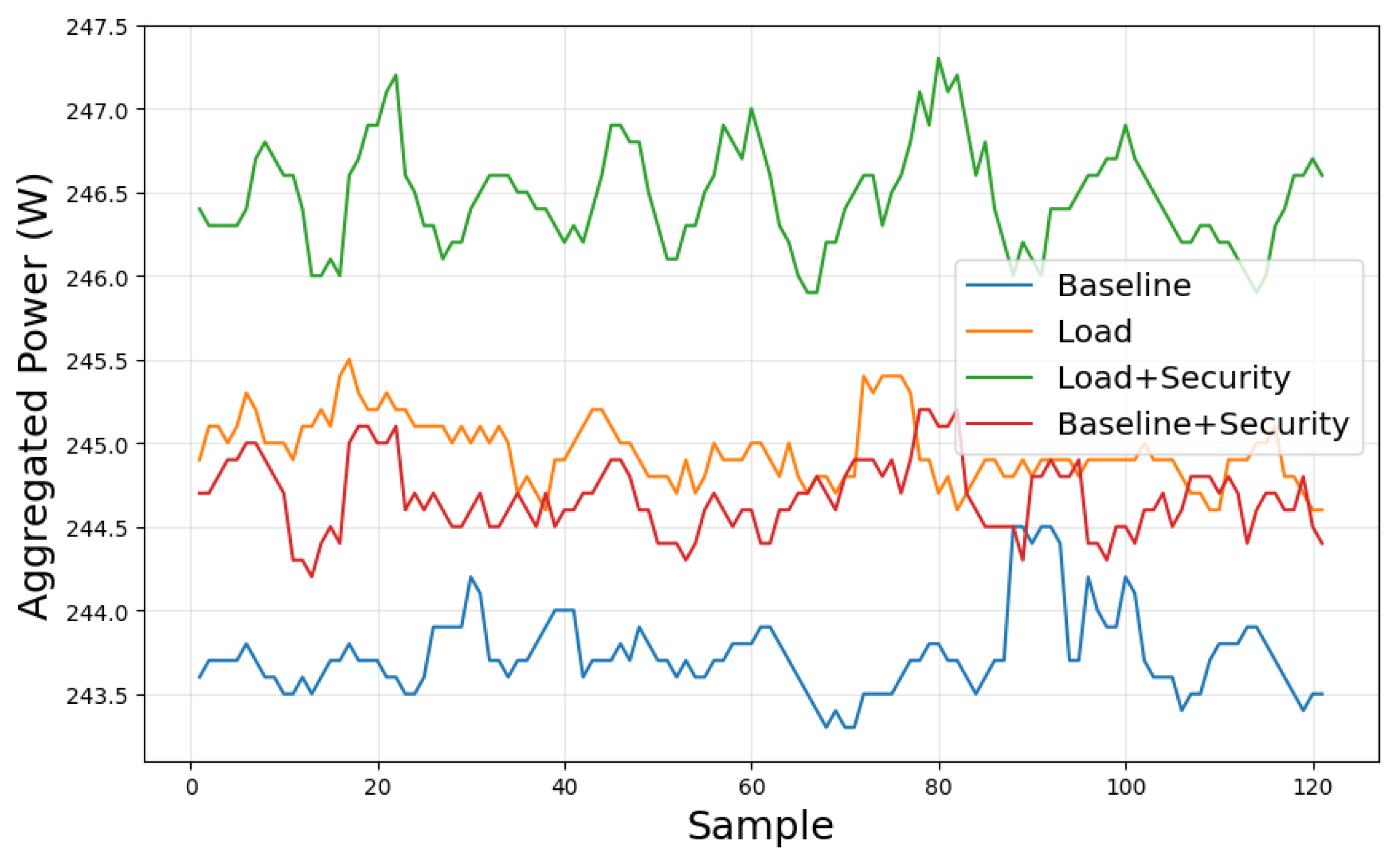

Figure 5 presents four time series of aggregated power for the same cluster under different conditions.

Baseline is the reference trace with Online Boutique deployed.

Load represents the previous configuration with load generator (Locust) enabled and scaled at 3 replicas with 400 users and a 40 spawn rate.

Baseline+Security illustrates the idle state with Falco, Tetragon, and WireGuard enabled, while

Security+Load combines the aforementioned security measures with the load generator.

A key observation is that an idle cluster with security enabled (Baseline+Security) draws power close to—or even overlapping with—a cluster with load without security measures. In particular, OB+Load shows an average power increase of W, peaking at W relative to OB+Baseline and OB+Security, which give values of 0.89 W and 1.47 W, respectively. This highlights the steady energy cost of always-on controls, which consume CPU and memory even when the deployed application is in idle state. With Security+Load, consumption rises further above that level ( W on average, peaking at W), indicating that the triggering of encryption and runtime monitoring presents significant energy overhead in realistic workloads.

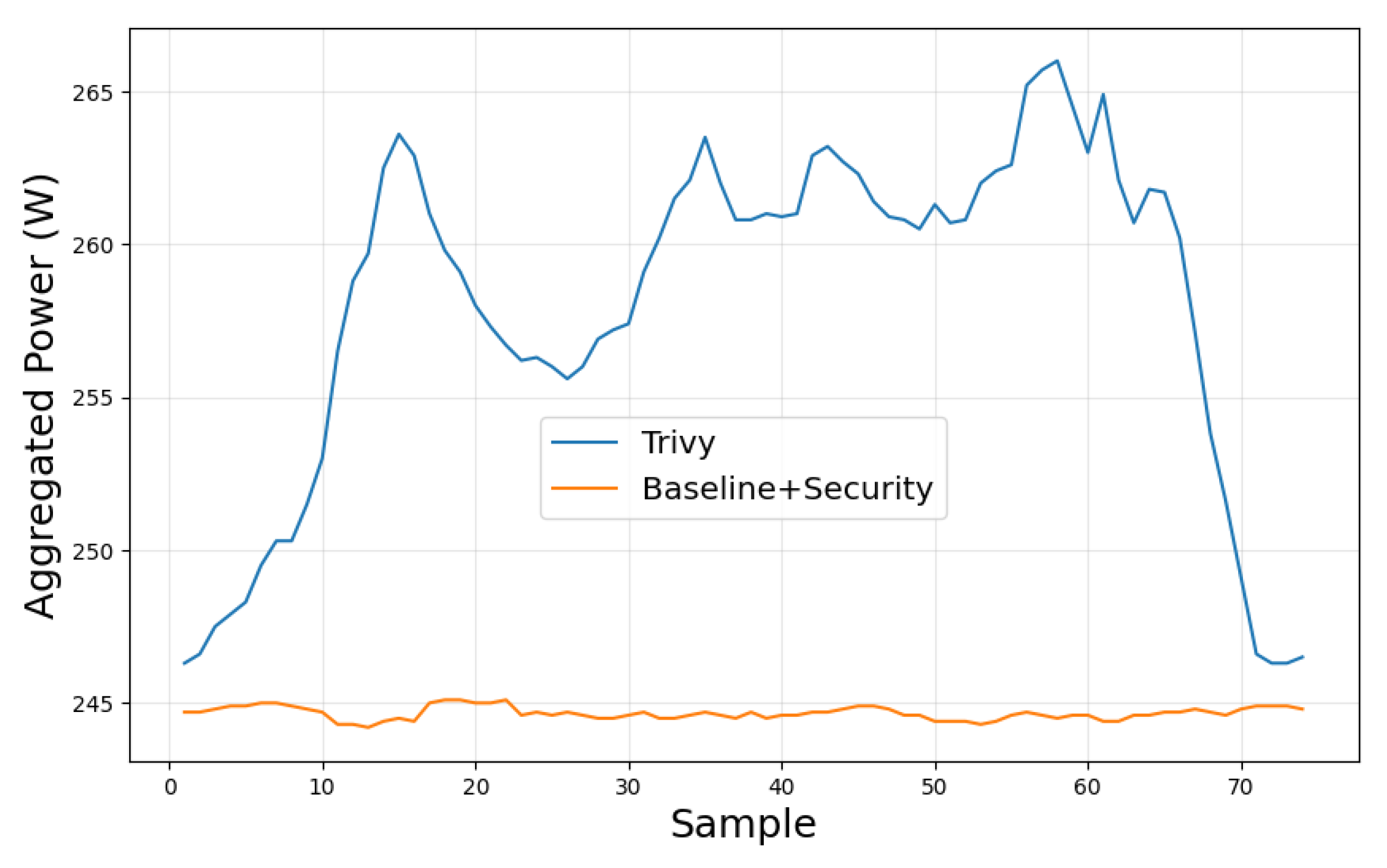

5.5. Vulnerability Scanning Consumption

The chart in

Figure 6 compares Trivy (blue) against Online Boutique deployment with security measures (orange). The blue line shows a sharp, short-lived jump in power, which then drops back near the baseline. The spike corresponds to the vulnerability scan window: Trivy updates its database, reads image layers, and matches against CVEs. These steps are CPU-intensive and create bursty disk I/O and network traffic.

Although each scan produces only a short-lived but significant increase in power draw (15–20 W), these spikes will recur periodically with the Trivy operator as part of routine cluster hardening. In practice, the energy impact becomes a sequence of brief bursts rather than a continuous overhead. The behavior can be shaped—but not eliminated—by tuning scan frequency and scoping (e.g., limiting scans to selected namespaces and workloads).

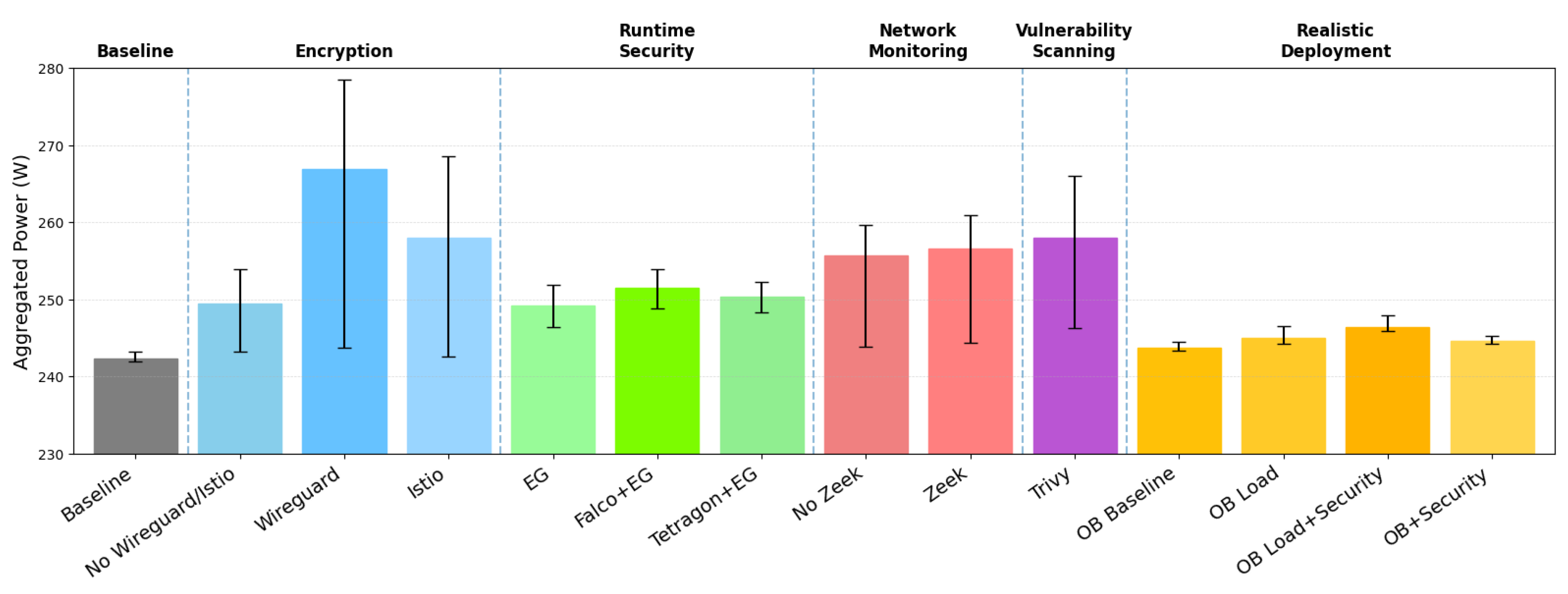

5.6. Overall Consumption

The bar chart illustrated in

Figure 7 summarizes mean aggregated power across multiple configurations. Error bars show variability between the minimum and maximum values of measured power. Baseline sits lowest (≈242–243 W). Adding a service mesh or full-tunnel encryption raises power consumption the most: Istio and WireGuard have the highest means (

W and

W) and widest variability. Host-level eBPF sensors are comparatively light: Falco and Tetragon show small, steady upticks over the baseline, with average power ranging between

W and

W, respectively. Network monitoring is also light as the UDP spray significantly increases the power consumption, but with Zeek enabled the mean power does not increase substantially (

W without Zeek and

W with Zeek). Trivy has a higher mean (

W) with large error bars, consistent with short, compute-intensive scan windows that spike power. For the realistic workload, the Online Boutique baseline with security (

W) seems to approach

OB+Load without security, which reaches an average of

W, illustrating that safeguards carry a steady energy tax.

In

Table 3, we distinguish between two reference points for energy evaluation. The idle baseline denotes the power consumption of the Kubernetes cluster with only essential system components running and no active workload or synthetic traffic. This baseline captures the minimum steady-state energy draw of the platform. The experimental baseline, on the other hand, corresponds to the execution of a given workload or traffic pattern without the security mechanism under evaluation. Comparing against the experimental baseline allows us to isolate the marginal energy overhead introduced solely by the security control, independently of the workload itself. The next two columns report the differences between the mean and peak values observed in

Figure 7 and the cluster’s baseline, capturing the absolute uplift over an idle system. After that, we provide the mechanism’s mean and peak power minus the experimental baseline, isolating the overhead introduced solely by the security component. In the final column, standard deviation (SD) is calculated to quantify temporal power variability.

Results show that link encryption (WireGuard) introduces the largest overhead, adding approximately W mean and W peak over the idle baseline (or ≈17.4 W mean compared to plain iperf), while Istio with mTLS is the second most demanding mechanism, contributing ≈15.7 W mean over idle and ≈8.5 W marginal overhead relative to the unencrypted workload. Runtime monitors impose comparatively small costs under repeated security events, as Falco + EG add ≈2.3 W, while Tetragon + EG add ≈1.2 W. For network monitoring, Zeek introduces a modest ≈0.9 W marginal overhead, even though the high-rate UDP spray itself increases power consumption by ≈13.3 W on average. Vulnerability scanning with Trivy was executed on top of the Online Boutique deployment with all security mechanisms enabled; thus, the experimental baseline corresponds to the full OB + Security configuration. Under these conditions, Trivy adds ≈13.3 W mean and peaks at ≈21.4 W. In the realistic application scenario, enabling security mechanisms during idle traffic results in a small steady marginal overhead of ≈0.9 W, peaking at ≈1.5 W, while under heavy workload the overhead increases to ≈1.4 W mean and ≈3 W peak. Standard deviation reveals that encryption mechanisms exhibit high variability due to the experimental design with three iperf iterations, capturing traffic startup, steady-state, and shutdown phases; similarly, Zeek and Trivy show moderate variability, reflecting UDP spray activation/deactivation and scanning start/stop transitions, respectively. In contrast, eBPF-based monitors and realistic application workloads demonstrate exceptional stability under continuous operation.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

In this study, we analyzed the trade-offs between security and energy consumption in K8s-based environments, providing quantitative insights into how common cloud-native safeguards affect power consumption—insights that are pertinent to IoT and smart city deployments. Our results show that always-on mechanisms introduce a steady power draw that can bring an idle, secured cluster close to the consumption of a loaded, unsecured one. Under realistic microservice traffic, the incremental overhead of security under load remained additive and stable, whereas vulnerability scanning produced short but significant spikes in power. Service mesh and full-tunnel encryption contributed the largest sustained overheads; host-level eBPF was comparatively modest; and network security monitoring also introduced modest costs. Overall, the results indicate that careful selection and tuning of safeguards can maintain strong protection while keeping energy impact manageable.

Despite the fact that encryption, runtime monitoring, and other security mechanisms introduce a non-negligible energy overhead, these measures play a critical role in ensuring system integrity. The additional energy consumption stems from essential operations such as cryptographic processing, continuous observability, and real-time detection of malicious activity, all of which significantly reduce the risk of successful attacks. In security-sensitive environments, the cost of inadequate protection can far outweigh the energy savings achieved by disabling such mechanisms, potentially leading to data breaches, service disruption, or system compromise. Therefore, the incurred energy overhead should be viewed as a necessary trade-off for achieving security guarantees, rather than as an avoidable inefficiency.

Future work will broaden the evaluation to a wider spectrum of security tools, more diverse workloads as well as execution times, and larger cluster-scale experiments. Expanding the evaluation to include larger clusters with diverse configurations will be essential to improve the generalizability of the findings. In addition, experiments conducted on bare-metal infrastructures will allow access to hardware power counters, enabling more accurate attribution of energy consumption, as Kepler’s model may introduce potential estimation errors. By characterizing the energy overhead introduced by specific safeguards, the findings enable trade-off decisions between security strength and power usage. The result can be leveraged by ML/AI-based energy-aware adaptive security mechanisms that dynamically tune safeguards in response to workload and power signals, preserving security while respecting energy budgets—especially on edge/IoT nodes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D. and V.T.; methodology, I.D. and G.K.; software, I.D.; validation, I.D., G.K. and V.T.; formal analysis, I.D.; investigation, I.D.; resources, I.D. and G.K.; data curation, G.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D.; writing—review and editing, I.D., G.K. and V.T.; visualization, I.D.; supervision, V.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation (EU) 2024/2143 of 29 July 2024 Setting out Guidelines for the Interpretation of Article 3 of Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards the Energy Efficiency First Principle. 2024. Notified Under Document C(2024) 5284. Official Journal of the European Union, L Series. 9 August 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reco/2024/2143/oj/eng (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Mao, Y.; Yu, X.; Huang, K.; Zhang, Y.J.A.; Zhang, J. Green edge AI: A contemporary survey. Proc. IEEE 2024, 112, 880–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almihat, M.G.M.; Kahn, M.T.E.; Aboalez, K.; Almaktoof, A.M. Energy and Sustainable Development in Smart Cities: An Overview. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1389–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpilko, D.; Fernando, X.; Nica, E.; Budna, K.; Rzepka, A.; Lăzăroiu, G. Energy in Smart Cities: Technological Trends and Prospects. Energies 2024, 17, 6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snousi, H.M. Adaptive fog computing architecture for scalable smart city infrastructure. Electron. Commun. Comput. Summit 2025, 3, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Aslanpour, M.S.; Toosi, A.N.; Cheema, M.A.; Chhetri, M.B. FaasHouse: Sustainable serverless edge computing through energy-aware resource scheduling. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2024, 17, 1533–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Mamun, Q.; Islam, R. Balancing Security and Efficiency: A Power Consumption Analysis of a Lightweight Block Cipher. Electronics 2024, 13, 4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donenfeld, J.A. WireGuard: Next Generation Kernel Network Tunnel. In Proceedings of the NDSS, San Diego, CA, USA, 26 February–1 March 2017; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Internet Security. CIS Kubernetes Benchmark v1.11.1; Center for Internet Security: East Greenbush, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.cisecurity.org/benchmark/kubernetes (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Kubernetes Hardening Guidance. In Technical Report Version 1.2; National Security Agency (NSA): Meade, MD, USA; Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA): Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Fahad, M.; Shahid, A.; Manumachu, R.R.; Lastovetsky, A. A Comparative Study of Methods for Measurement of Energy of Computing. Energies 2019, 12, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, M.; Chen, H.; Chiba, T.; Nakazawa, R.; Choochotkaew, S.; Lee, E.K.; Eilam, T. Kepler: A Framework to Calculate the Energy Consumption of Containerized Applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 16th International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD), Chicago, IL, USA, 2–8 July 2023; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centofanti, C.; Santos, J.; Gudepu, V.; Kondepu, K. Impact of power consumption in containerized clouds: A comprehensive analysis of open-source power measurement tools. Comput. Networks 2024, 245, 110371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijnacker, B.; Setz, B.; Andrikopoulos, V. Container-level Energy Observability in Kubernetes Clusters. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.; Borges, M.C.; Wolf, K.; Tai, S. A Comprehensive Experimentation Framework for Energy-Efficient Design of Cloud-Native Applications. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Software Architecture (ICSA), Odense, Denmark, 31 March–4 April 2025; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, K.; Garg, S.; Kaddoum, G.; Ahmed, S.H.; Atiquzzaman, M. KEIDS: Kubernetes-based energy and interference driven scheduler for industrial IoT in edge-cloud ecosystem. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 7, 4228–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, W.; Li, H. Energy-aware Scheduling Algorithm for Microservices in Kubernetes Clouds. J. Grid Comput. 2025, 23, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beena, B.; Ranga, P.C.; Holimath, V.; Sridhar, S.; Kamble, S.S.; Shendre, S.P.; Priya, M.Y. Adaptive Energy Optimization in Cloud Computing Through Containerization. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 159548–159565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.; Sofia, R.C. Experimenting with Energy-Awareness in Edge-Cloud Containerized Application Orchestration. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.09116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukis, G.; Skaperas, S.; Kapetanidou, I.A.; Mamatas, L.; Tsaoussidis, V. Evaluating CNI Plugins Features & Tradeoffs for Edge Cloud Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Paris, France, 26-29 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapetanidou, I.A.; Nizamis, A.; Votis, K. An evaluation of commonly used Kubernetes security scanning tools. In Proceedings of the 2025 2nd International Workshop on MetaOS for the Cloud-Edge-IoT Continuum, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 30 March–3 April 2025; pp. 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Viktorsson, W.; Klein, C.; Tordsson, J. Security-performance trade-offs of kubernetes container runtimes. In Proceedings of the 2020 28th International Symposium on Modeling, Analysis, and Simulation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems (MASCOTS), Nice, France, 17–19 November 2020; IEEE: Piscataway Township, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Koukis, G.; Skaperas, S.; Kapetanidou, I.A.; Tsaoussidis, V.; Mamatas, L. An Open-Source Experimentation Framework for the Edge Cloud Continuum. In Proceedings of the IEEE Infocom 2024—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20 May 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |