Abstract

We present a psycholinguistic test battery designed to examine the cognitive and affective processes involved in reading Polish poetry. This toolkit combines reader profiling (vocabulary, memory and reading proficiency) with tasks that assess the influence of lexical, textual, affective and poetic features on recognition, context restoration and association generation. Pilot data confirmed the reliability of the measures and their sensitivity to recognised psycholinguistic effects. Vocabulary size and delayed memory rehearsal strongly predicted performance in content restoration, while recognition and association latencies were closely related, indicating shared retrieval mechanisms. Structural and affective properties also influenced responses: line-final words improved recognition but impeded association, with these effects being moderated by word length and frequency. Words that were negatively valenced, abstract and hardly imaginable were restored more accurately than positive or concrete ones. These findings demonstrate the potential of the battery for profiling readers and provide new insights into how Polish poetic language engages memory and associative processes.

1. Introduction

Reading is a multidimensional phenomenon involving cognitive and perceptual, socio-emotional, and background knowledge domains (e.g., Cain and Oakhill 1999; Kim 2020; Smith et al. 2021). The reading process is further influenced by modalities, i.e., paper vs. screen (Hakemulder and Mangen 2024; Mangen and Kuiken 2014), and text genres (Hanauer 1998; McCarthy et al. 2024; Zwaan 1994) yet the genre effect is challenged by recent studies (Hartung et al. 2017; Triantafyllopoulos et al. 2021).

Empirical studies of literature (ELS) is a rapidly growing interdisciplinary field (Alber and Strasen 2020; Kuiken and Jacobs 2021; Lauer 2015) that explores how literary reading influences our cognition and emotions. Within ELS, empirical research on poetry has emerged as a distinct subfield. Since Roman Jakobson introduced the poetic function of language (Jakobson 1975) and advocated for the application of rigorous scientific methods to study poetry (Jakobson 1976), several influential frameworks have been developed, including Cognitive Poetics (Tsur 2008), Neurocognitive Poetics (Jacobs 2014, 2015), and Psychopoetics (van Peer and Chesnokova 2022). They combine literary analysis with modern empirical techniques such as eye tracking, fMRI, or EEG. However, the methodological framework of cognitive poetics is still being developed (e.g., Brône and Vandaele 2009).

Poetry is an example of “unconventional” texts (De Beaugrande and Dressler 1982), being charged with poetic devices, specific prosody, syntax violations, and visuo-spatial organization (e.g., Kulawik 1994, pp. 52–130; Lukin 1999). These traits challenge the reader’s ability to create a coherent text representation in mind. The quality of these representations often depends on linguistic markers, narrative types, readers’ background knowledge, etc. (Moss and Schunn 2015; Saux et al. 2021; van Dijk and Kitsch 1983). Once poetry steps outside conventional narrative frameworks, it initiates comprehension tactics that differ from those used with other text types.

In recent decades, researchers have uncovered remarkable patterns in how poetry shapes readers’ experience, stirring feelings, awakening emotions, and guiding the reading process. Poetry is read more slowly, provoking more regressive eye movements with a higher number of fixations compared to prose (Blohm et al. 2022; Fechino et al. 2020; Peskin 2007), and metrical anomalies exhibit disruptive eye movements and increased rereadings (Beck and Konieczny 2021). Geyer et al. (2020) reported that juxtaposition of two images and the usage of cut markers complicate meaning resolution and reading fluency. They likely act as foregrounding elements and thus de-automatizing the reading process.

In Gao and Guo’s (2018) study, Chinese poetry was evaluated as more beautiful than prose and induced intense activation of “aesthetic centers” in the human brain. Obermeier et al. (2015) observed the facilitating effect of rhyme and meter in different levels of processing and increased liking of rhymed and metered pieces. Kraxenberger and Menninghaus (2017) have shown that affinity with poetry affects aesthetic evaluation. Cross and Fujioka (2019) observed the right hemisphere dominance and left hemisphere reduction while rhyme processing by lyricists compared to non-lyricists. Experts are likely more attuned to phonological incongruity, employing more holistic problem-solving and decision-making strategies (Cross 2023). Lea et al. (2021) suggested experts’ advanced skills in phonological anticipation, and Kao and Jurafsky (2012) reported exceptional skills of poetry experts in lexical and poetic forms reception. Fokin et al. (2022) observed that poets tend to keep a steady pace, progressing through the line, suggesting that they perceive all words as equally important.

Menninghaus and Wallot (2021) observed rhymed and metered poetry is more beautiful and moving and provokes the deceleration of the reading pace, likely caused by “savoring effect”. Xue et al. (2019, 2023) cemented the list of predictors important for poetry reading, including lexical, textual, affective-semantic features such as orthographic neighborhood and dissimilarity, sonority score, valence, etc. During the rereading session, affective features became even more important. This is in line with findings on the key role of affective characteristics of words in poetry (Aryani et al. 2016; Lüdtke et al. 2014). Hugentobler and Lüdtke (2021) reported that higher semantic cohesion induces fewer and less varied associations, contributes to mental image creation, and influences basic (word identification) and higher-order (integration) processes.

A recent large-scale study by Porter and Machery (2024) introduces a new angle to this debate by comparing AI-generated and human-authored poetry. Readers were unable to distinguish between two types of poetry and evaluated aesthetically higher AI-generated pieces while human-written pieces more often “made no sense”. Researchers concluded that more straightforward artificial poetry unambiguously communicates image, mood, and emotions, and does not require in-depth comprehension and understanding. Similar patterns were previously observed in Köbis and Mossink’s (2021) study, yet readers found AI-generated poems more semantically poor.

Together, these findings provide extensive evidence on how poetry shapes reading and cognitive processes, revealing the unique influence of poetry on comprehension and aesthetic appreciation. However, the rich tradition of Polish poetry remains underrepresented in empirical research. The underrepresentation leads to the perpetuation of a methodological lacuna and conceptual blindness to particular language families and poetic traditions, creating a systematic bias. Hence, it is crucial to conduct empirical research that is as linguistically and formally diverse as possible, expanding the research scope and thus increasing the empirical material on the basis of which universal patterns might be observed. In this study, we enlarge the extant body of work by including Polish poetic material.

2. The Present Study

2.1. State-of-the-Art

Only a few papers investigate Polish poetry using empirical and quantitative methods. Comparing English and Polish texts, Grabska-Gradzińska et al. (2012) found that literary texts, i.e., poetry and prose, tend to follow a scale-free structure, meaning a high dispersion of the lexical network with only a few significant nodes (concepts) having a high number of connections; scientific texts, in turn, consist of a pool of highly frequent and well-connected words (for review see Nodus Labs 2012; Sole and Valverde 2004). Osowiecka and Kolanczyk (2018) observed increased indices of creative thinking after reading Szymborska’s “Utopia” compared to the cooking book description, aligning genre-specific hypotheses (Hanauer 1998). Yet, these isolated studies do not apply mixed-method approaches or propose methodological tools suitable for empirical research on Polish poetry. This highlights the need for methodologically robust instruments to investigate poetry comprehension in controlled settings.

For the experiment, we selected poems by the most renowned modern Polish poets: Wisława Szymborska, Adam Zagajewski, and Zbigniew Herbert. Their practices arouse permanent interest among literary scholars (e.g., Czapliński and Śliwiński 2000; Hutnikiewicz and Lam 2000), Szymborska was honoured with the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1996 while Zagajewski was its finalist and Herbert—a candidate in 1968. Also, all three won numerous international awards. The empirical study of these authors offers fresh insights on their poetry and its influence on readers. In the present study, we introduce a psycholinguistic test battery for the empirical study of poetry and poetry readers.

2.2. Aims and Hypotheses

The main purposes of the study are to develop an experimental toolkit for the empirical study of poetry and readers’ cognitive and behavioral responses and to pilot the battery under controlled circumstances. The following research question guided our exploration:

RQ1.

What means are best-fitted for comprehensive empirical study of modern poetry?

RQ2.

How does reading modern poetry impact cognitive processes involved in verbatim and content remembrance, associative processes, and topic identification?

RQ3.

What are the roles of textual, lexical, poetic, and affective features in framing these effects?

Based on the proposed questions, we assume:

H1.

The in-depth analysis of modern poetry comprehension can be conducted, employing the two-step experimental toolkit consisting of preliminary reading-related skills assessment and control study of reading-related cognitive processes;

H2.

Selected means are capable of (a) measuring verbatim memory, content remembrance, and associative processes; and (b) the reader’s ability to identify the poetic topic.

H3.

Affective features are the key drivers in poetry reception, shaping verbatim memory, content remembrance, and associative responses. Textual word properties, particularly position in the line, are salient predictors of remembrance but are refined by poetic devices, e.g., rhyme or enjambment. Lexical features contribute to reception, but their influence is contingent on affective word properties, which can either enhance or diminish their impact.

3. Materials and Methods

Stimuli

The selected poems exemplify two of the most prevalent forms of contemporary Polish poetry (Kulawik 1994; Pszczołowska 2001). Herbert’s poem adheres to regular syllabic-accentual verse, while Szymborska’s and Zagajewski’s poems are written in free verse (the so-called sentence poem). All three adhere to the syntactic norms of the Polish language, use conventional lexicon, and utilize analogous poetic devices, such as enumeration, syntactic parallelism, and verse anaphora, while being devoid of rhyme regularities.

The poems are comparable in readability index (SMOG) (McLaughlin 1969; Scott 2025), number of lines, and average word length, diverging in visual layout, prosodic contour, and poetic tropes employed (e.g., metaphor, enjambment) (Table 1). Thus, poems represent the broad but nevertheless comparable spectrum of poetic practice.

Table 1.

Stimulus poems descriptives.

4. Research Variables

The research variables reflect distinct yet interacting layers of poetic architectonics (Jacobs 2015)—lexical, textual, affective, and poetic—which shape how readers cognitively engage with poetic texts.

Lexical properties of words (e.g., frequency and length) typically follow Zipf’s law (Lestrade 2017; Linders and Louwerse 2023; Zipf 1949), where high-frequency words tend to be shorter. These properties directly affect eye movement behavior (Rayner 1998), appear to be universal across alphabetic languages (Kuperman et al. 2024), and also influence memory in line with Kolmogorov complexity (Ehret 2018), which links length to the restoration of information content. Word length represents the number of letters per word. Word frequencies were derived from Polish Web Corpus 2019 (Jakubíček et al. 2013; Lexical Computing CZ s.r.o. n.d.) and log-transformed to normalize the distribution and mitigate skewness typical for raw word frequencies. Textual features included position within the line (initial, medial, or final) and the word’s serial position in the poem. Word placement is a crucial feature for poetic study since it represents syntactic peculiarities (including such devices as enjambement) and spatial organization (Blohm et al. 2022; Fechino et al. 2020). It was observed that overall line-final words are better remembered and induce the closure effect (Kuperman et al. 2010; Menninghaus and Wallot 2021).

Poetic variables included rhyme, enjambment, metaphor, and enumeration, and were manually annotated (0 = absent; 1 = present). These poetic tropes were chosen due to their well-documented effect on reading behavior and experienced emotions (Jacobs and Kinder 2018; Rasse et al. 2020; Stamenković et al. 2023). Metaphors were identified based on conceptual mappings and figurative language markers, e.g., wój wyścig z suknią nadal trwa (my race with the dress is still on). Enjambments are well-known as disturbing elements that impede reading and comprehension fluency (Delente 2024; van ‘t Jagt et al. 2013) and create a tension between syntactic and versification lines, adding fragmentarity but also flow to the poetic piece (Mastalski 2023; Tsur 2015):

Omszały woźny drzemie słodko zwiesiwszy wąsy nad gablotkąW. Szymborska

The moss-grown guard in golden slumber props his moustache on the Exhibit Number.(transl. S. Barańczak and C. Cavanagh)

Enumerations function as prosodic scaffolding, contributing rhythmicity and cohesion to the poetic structure. It adds rhythmicity and references to the clause, creating a sense of stasis and motion, manipulating it with different degrees of connections between elements involved (e.g., Brickey 2022; Vedder 2022). In the study, enumerations are understood as phonological parallelisms and list-like elements, sequentially located within one or several lines and linked to one semantic construct, e.g.,

dotykamy i oka i powietrza, ciemności i światła, Indii i Europy(A. Zagajewski)

We touch the eye and air, the darkness and the light, India and Europe.(literal transl. D.F.)

Rhyme, as a basic parallelistic, rhythm-related element, creates the beauty, poeticity, and melodiousness of poetry (Menninghaus and Wallot 2021), purposefully delivers a wide spectrum of emotions (Kraxenberger and Menninghaus 2017; Johnson-Laird and Oatley 2022), and evokes intense feelings and aesthetic appreciation (Obermeier et al. 2015). In the paper, rhyme is understood as rhymed consonances in any line position:

w niebieskich chmurach aromatu

smakował uśmiech w wargach wąskichZ. Herbert

In the blue clouds of aroma

He savored a smile in his narrow lips(literal transl. D.F.)

The selected poems lack regular metrical and rhyming patterns. So, these dispersed rhythmic structures require readers to rely more heavily on localized poetic cues.

Finally, affective features refer to the emotional meaning of a word and readers’/listeners’ feelings evoked by a word (Kuperman et al. 2014). They were taken from Imbir’s (2016) norms gathered using the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM) 9-point scale (Lang 1980) and included: Valence (unpleasant vs. pleasant); Dominance (submissive vs. control); Origin (emotional vs. rational); Arousal (calmness vs. excitement); Significance (unimportant vs. important); Concreteness1 (concrete vs. abstract); Imageability (low vs. high degree of mental imagery)2. A recent study of Aka et al. (2021) revealed the positive influence of some affective features (valence, arousal, concreteness) on word remembrance. Other studies revealed the impact of affective word properties on poetry reading, liking, aesthetic, and emotional appreciation (e.g., Aryani et al. 2016; Hugentobler and Lüdtke 2021; Johnson-Laird and Oatley 2022; Ullrich et al. 2017). Thus, lexical affectiveness may play a key role in poetry reception, creating a tone and atmosphere of a poem but also modulating readers’ perception of it. Table 2 summarizes the variables included in the analysis.

Table 2.

Descriptives of features used in the study.

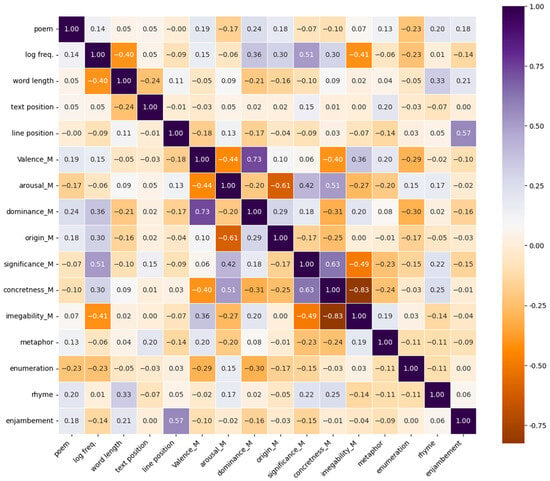

The interactions of all the above-mentioned features are summarized in Figure 1 (see for details Fokin (forthcoming). In short, the matrix reveals strong relations between lexical and affective word properties, the key role of word frequencies, whereas textual features barely correlate with linguistic and affective ones.

Figure 1.

The correlation matrix of all variables included in the study.

5. Methodology

5.1. General Overview

The test battery (six experiments lasting around 60 min) consists of two main blocks:

- Preliminary experiments (three tests lasting 15 min) include the Polish adaptation of the SLS-Berlin test (Lüdtke et al. 2019) to assess one’s reading proficiency, hereafter referred to as the Polish Reading Proficiency Test (PRPT); the Polish Vocabulary Size Test (Fokin et al. 2025), developed to evaluate participants’ receptive vocabulary size; and the Polish MoCA, a verbal short-term memory subtest (Gierus et al. 2015), which explores the accuracy of word remembrance. Together, they are aimed at creating a reader’s linguistic profile.

- Control experiments (3 tests lasting 45 min) assessing high-level cognitive processes such as memory-based processes, task-switching, inferencing, and contextual associations: Context-Primed Associations Task, designed to test key predictors impacted by verbatim memory, switching between intermediate- and long-term memory buffers, and associative processes. The Cloze-Test (CT) is employed to study the quality of text representation and poetic content remembrance, and the Topic Inferential Task aims to reveal inferential skills.

5.2. Procedure

Participants first signed an informed consent form and an agreement for the processing of personal data. They were then instructed about the procedure and proceeded with the study. First, they completed the PRPT on the experimental computer, followed by the MoCA. Next, participants read a practice verse—the first quatrain of Ewa Lipska’s “Kraj podobny do innych”—displayed on the screen, and then completed the CPAT, CT, and TIT tasks to familiarize themselves with the design. After reading the practice verse, they were asked to repeat aloud the words from a delayed memory task.

After the practice session, the control experiment began. Participants read the three poems presented in random order, one by one. After reading each poem, they completed the CPAT (via the LimeSurvey platform, version 6.4; Lime Survey GmbH 2023) and CT tasks. This sequence was repeated three times—once for each poem.

Participants’ eye movements were recorded using an SMI 500 eye tracker throughout the reading phase. The CPAT was completed on participants’ personal devices, while the Cloze Test (CT) was administered on the experimental computer.

Finally, after all three poems and the respective tasks were completed, participants performed the TIT task on the experimental computer.

5.3. Polish Reading Proficiency Test (PRPT)

PRPT was adapted to Polish from the SLS-Berlin Test (Lüdtke et al. 2019), aiming to bridge the critical gap in assessing reading proficiency. Here, participants read 77 sentences and responded aloud whether the sentence aligned with general world knowledge (correct) or violated it (incorrect). Then, they evaluate sentence complexity on a 5-point scale. Readers’ complexity evaluations were averaged for each sentence and compared with the German original. Sentences were translated from German, considering Polish cultural and language nuances. The Polish adaptation is comparable with the original in the number of syllables but exceeds it in the number of letters and long words, and yields to it the number of words in a sentence (see Appendix A, Table A1).

5.4. Polish Vocabulary Size Test (PVST)

PVST (Fokin et al. 2025) was newly developed using a procedure introduced by Golovin (2015). It measures the receptive vocabulary width of native Polish speakers with high precision. During the test, participants decide whether they know at least one of the word’s meanings (yes/no) and the word’s synonym in several multiple-choice questions. Test-takers responded to around 40 items within around 2.5 min.

Once the test is completed, participants provide their age and native language (Polish vs. non-Polish), and respond whether they answered honestly (when the test taker did not tick this box, their responses were not counted). Participants completed the test on their personal devices.

5.5. Polish Verbal Short-Term Memory Test

Polish MoCA verbal subtest (Gierus et al. 2015) evaluates one’s verbal memory capacity. The participant first listens to the five words, pronounced by the examiner, then s/he recalls them aloud twice: in around 2.5 min (right after PVST) and in around 10 min after the practice trial. While the MoCA protocol traditionally uses a ~5 min interval between encoding and delayed recall, our study implemented a longer delay (~10 min) with intervening tasks involving linguistic processing. This variation aims to assess the durability of intermediate-term memory (Kamiński 2017; Rosenzweig et al. 1993) under cognitive load and interference, critical circumstances of the present research design.

5.6. Context-Primed Association Test (CPAT)

CPAT combines elements of the Recognition Memory Task (Rich 2017) and the Free Association Test (see Goroshko 2001; Aitchison 1987). The test was designed with three main goals: 1. to assess the speed and accuracy of retrieving items presented outside their poetic context, i.e., verbatim memory; 2. to measure task-switching between recognition and associative tasks, assuming that both rely on verbal–semantic processing; and 3. to collect associative data, given the lack of associative dictionaries in Polish.

It is widely acknowledged that the mental lexicon is organized as a network based on associative principles, where activation of one node spreads gradually across the entire network (Collins and Loftus 1975). Word meaning is defined by both context (Schmid 2005) and background knowledge (Duch et al. 2008). The part of speech also influences the types of associations produced (Anstatt 2008; Gawarkiewicz 2024; Kurcz 1967). Thus, this test is well-suited for studying associations activated by poems and the influence of poetic content on the variation and richness of associative responses.

Participants are presented with 24 words (16 nouns and 8 adjectives) in total—five stimuli and three foils per poem, across three poems. The control items differed in their placement in a line (7 line-final vs. 7 line-middle). In addition, some of them represent poetic devices (three enjambments, four rhymes, and one—a component of a metaphor). First, participants answered a recognition question: “Was this word present in a poem?” (yes/no). If they answered “yes”, they were then asked to recall as much context as they remembered (open question with “don’t remember” accepted as a valid response). Regardless of their recognition answer, test-takers were subsequently asked to provide the first five words that came to mind upon seeing the stimulus. This sequence was designed to anchor participants in the poem’s content, so that their associations would be influenced by contextual recall.

We measured response times for the recognition and association tasks, and properties of the associations themselves.

5.7. Cloze-Test (CT)

CT evaluates participants’ verbatim memory and the ability to use contextual clues to restore gaps (Mcgee 1981, pp. 145–56; Sadeghi 2021, pp. 65–83). Up to 10 words were removed from the poem, and participants filled in the gaps from memory by pronouncing the missing word. Contrary to the common practice of removing every fifth word, we wanted to examine how the word position in line and poetic tropes influence verbatim recall. Thus, the removed items were dispersed over the text but did not follow each other. The proportion of the removed items is as follows: five initial, fifteen middle, ten final words; out of them, there were fourteen rhymes and ten enjambments. We followed the common practice of exact scoring (Sadeghi 2021, pp. 73–77) (correct vs. incorrect).

5.8. Topic Inferential Task (TIT)

TIT examines participants’ abilities to draw topical inferences within poems. The test was adapted from Cain et al. (2004) and Long et al. (1997). Participants read six two-line excerpts (twelve lines total) drawn from three poems, for example: “w niebieskich chmurach aromatu/smakował uśmiech w wargach wąskich.” Each excerpt was followed by three word pairs (prime–target), such as chmura–zadowolenie (“cloud–satisfaction”), chmura–arogancja (“cloud–arrogance”), and niepogoda–chandra (“bad weather–depression”). These pairs served as semantically appropriate, inappropriate, or filler trials, respectively (see Supplementary Materials). The participants’ task was to choose a word pair that better fits the topic of a sentence. We measured the accuracy of the responses.

6. Participants

Thirty-eight Polish native speakers (Mage = 22.5; female = 75%) participated in this study either voluntarily or via SONA panel (https://uw.sona-systems.com/ (accessed 25 November 2025)) in exchange for ECTS credits. The majority were BA students (84%); only five (13%) participants were enrolled in Philology programs, and only two studied Polish philology.

Six participants (15%) reported reading poetry at least a few times per week, preferring either regular metered or free verse poetry. Only one individual reported writing poetry. Thus, the sample was largely inexperienced in both literary training and poetry reading/writing, making it well-suited for the pilot study, establishing a baseline for future comparisons. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and were naïve to the purpose of the research.

7. Data Analysis

Raw data were checked manually for extreme and missing values and removed before applying an automatic cleaning procedure. In CPAT, 19 trials of one participant were discarded due to technical problems, 22 binary response time values of 26 participants, and 15 response time values in the associations’ test were preliminarily removed, being extremely high. Then, we removed outliers exceeding the participants’ specific cut-offs (Mean ± 3 SD). Among affective features, only 667 values were available based on Imbir’s (2016) data. RTs were additionally log-transformed to normalize distribution (available Removed for peer-review). Statistical analyses were conducted via JASP software (JASP Team 2023; version 0.18.3.), employing binomial Generalized Linear-Mixed Models, Pearson’s correlation, paired- and one-sample t-Tests, and Linear Mixed Regression Models.

8. Results

8.1. Polish Reading Proficiency Test (PRPT)

We compared the means of sentence complexity between the Polish and German versions of the SLS test to evaluate their comparability.

Table 3 reveals strong positive correlations between sentence-level psycholinguistic features (e.g., syllables, letters, word length) and average complexity ratings, but a strong negative link with the difference scores between versions. A paired-samples t-test confirmed this effect (t(76) = 7.55, p < 0.001, d = 0.86), supported by reduced range and standard deviation in the Polish version (rangepolish = 1.580; rangegerman = 2.680; SDpolish_difficulty = 0.269; SDgerman_difficulty = 0.504). This indicates that although PRPT reflects systematic relations at the sentence level, its sentences were overall easier than those in the German original, yielding, on average, a one-point lower complexity rating and a narrower distribution of item difficulty. This suggests the necessity to consider syntactic specificities of the Polish language, which were not addressed within the current adaptation. Nevertheless, both versions are moderately to strongly correlated (r(75) = 0.58, z = 0.66) (see Supplementary Materials), supporting the construct validity of the Polish adaptation (Messick 1988).

Table 3.

Pearson’s correlations between sentence characteristics in PRPT.

While the reduced difficulty in the Polish version limits its discrimination among highly proficient readers, the adaptation remains psycholinguistically grounded and suitable for inclusion in the present test battery.

8.2. Polish MoCA Verbal Subscale (P-MoCA)

To demonstrate that immediate and delayed responses in the P-MoCA test measure the same phenomenon, we examined their relationship. We also expected links between P-MoCA results and other memory-related measures, i.e., response times in the recognition and free association tasks in CPAT. In addition, we included vocabulary size (PVST) scores, as this test was completed before the delayed recall and might modulate performance.

We found that participants who performed better in immediate recall also performed better in delayed recall (r = 0.832; p < 0.001), confirming a strong connection between the two measures. Better memory scores in P-MoCA (i.e., lower values) were associated with larger vocabulary size (r_immediate = −0.124; p < 0.001; r_delayed = −0.162; p < 0.001). This is not surprising: people who remember better also tend to possess a broader vocabulary. Finally, response times in both recognition and free association tasks tended to correlate with MoCA delayed, but not immediate, scores (r_recognition = 0.110; p = 0.002; r_associations = 0.117; p < 0.001) (see Appendix A, Table A2).

8.3. Polish Vocabulary Size Test (PVST)

The present study utilized one of the early iterations of PVST, although the exact version cannot be retrospectively confirmed. However, the lack of validated tests does not allow for measuring vocabulary size differently. The current findings should be interpreted with caution, especially in regard to psychometric properties.

Nevertheless, Pearson’s correlation analysis reveals strong associations between PVST’s key variables: larger vocabulary scores are linked to higher accuracy (r = 0.279) and longer test duration (r = 0.274), while test accuracy is negatively related to test duration (r = −0.258) (see Supplementary Materials). This suggests that participants with higher vocabulary scores were more engaged with the task; longer total duration likely reflects the decision-making process, which in turn supports higher accuracy. At the same time, the negative accuracy–duration link indicates that more confident responses required less time per decision, whereas hesitation was associated with lower accuracy.

PVST yielded a normally distributed range of scores (M = 46.526; SD = 23.861; skewness = 0.981), suggesting meaningful individual variation in vocabulary size among participants. However, participants varied significantly in their receptive vocabulary knowledge (range 18,000–108,000; M = 46.270; SD = 23.821; Supplementary Materials).

8.4. Context-Primed Associations Test (CPAT)

The main target of CPAT—the associations provided by participants—was not analyzed in the present paper, as an in-depth qualitative analysis is required. These data will be published separately.

Table 4 presents descriptives of key variables. Overall, readers performed above chance in the recognition memory task, having ~67% of correct responses. Separated by the poem, results are slightly more accurate for Zagajewski’s poem compared to the other two (Mzagajewski = 0.719; Mszymborska = 0.626; Mherbert = 0.649).

Table 4.

Context-Primed Associations Test descriptives.

We then ran a statistical model (binomial GLMM) to see what modulates readers’ certainty when deciding whether a word had appeared in the poem. Here, two factors are crucial: the speed of decision-making and the placement of the word. First, the quicker the response, the more accurate it is (B = −0.919; t = −3.789, p < 0.001)—delays and mistakes are both due to uncertainty.

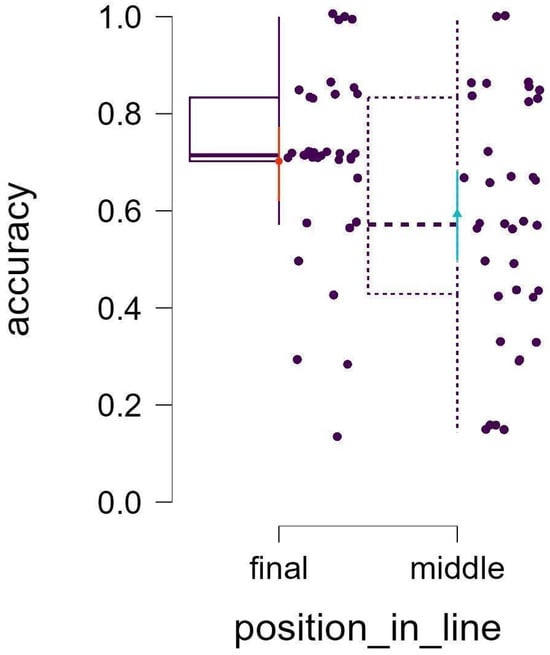

Second, line-final words are remembered better than line-middle ones (B = 1.356; t = 3.291; p = <0.001; Figure 2). However, the advantage of line-final words fades if the reader hesitates: as response time increases, the memory boost for line-final words disappears (see Appendix A, Table A3). In other words, the effect of ending words is strongest when recognition is immediate; otherwise, the word placement effect weakens.

Figure 2.

The effect of the word position on response accuracy.

To explore the relationship between lexical retrieval in the recognition task, context restoration, and performance in the free association task, we conducted a Pearson’s correlation analysis (see Supplementary Materials). The results revealed that word recalling is linked to the generation of associations, but not to the production of the context (RTrecognitionxRTassociations r = 0.198; p < 0.001; RTrecognitionxRTcontext r = 0.038; p = 0.449). So, the quick decision-making in word recognition expedites associative processes, evidencing the overlap between these cognitive performances and a possible prime effect.

Lastly, we examined which factors influence the generation of associations and found an interesting pattern: unlike in the recognition task, where line-final words improved accuracy, in the free association task, they instead led to longer hesitations before producing associations (B = 0.238; t = 4.493; p < 0.001). However, two interactions moderated this effect. First, the interaction between word length and line position (B = −0.023; t = −3.472; p < 0.001) indicated that longer words at the end of the line slowed responses less than shorter ones. Second, the interaction between word length and word frequency (B = −0.027; t = −2.844; p = 0.007) showed that short, high-frequency words contribute to the associative process. Results suggest that while line-final words generally decelerate associative responses, short and frequent words at the end of a line facilitate the generation of associations.

8.5. Cloze-Test (CT)

In CT, overall readers’ performance was below average, with only 33% of correct responses (Mean = 0.334; SD = 0.472). Yet there were differences in accuracy across poems: while reconstruction of Herbert’s and Szymborska’s poems is comparable (M_accuracy_herbert = 0.383; M_accuracy_szymborska = 0.354), Zagajewski’s poem significantly challenged participants (M_Accuracy_zagajewski = 0.265).

We first obtained that word length and valence and their interaction crucially affected participants’ performance (Table 5). Results demonstrate that short (up to five letters) and pleasant (valence ~ 4) words were remembered and restored much better compared to long and unpleasant ones (see here Appendix A, Table A5). Word valence is a stronger predictor of accuracy than word length; thus, increasing valence penalizes the advantage of length, and the accuracy decreases.

Table 5.

Fixed Effects Estimates: valence and word length impact on CT accuracy.

Most intriguing is the interaction of affective word properties while reconstructing a poetic content. Calm words (low in arousal), such as palmy (palms) or trwać (to last) restored significantly better (B = −7.186; t = −4.947 p < 0.001) than exciting ones (high in arousal). Decrease in imageability score, i.e., hard-to-imagine words, (B = −2.535; t = −4.119; p < 0.001) and increase in concreteness, i.e., abstract words3 (B = 1.922; t = 3.114; p = 0.002), additionally contribute to accuracy (see Appendix A, Table A6). Thus, words such as żyć (to live) or słodko (sweet) were better reconstructed than concrete and easy-to-imagine dywan (carpet) or glina (clay).

Further, the concreteness of a word modulates the effects of lexical imageability. Concrete and imaginative words, e.g., ściana (wall), are restored better, but an increase in word abstractness penalizes the effect of lexical imagery (Appendix A, Table A6). So, abstract but easy-to-imagine words, e.g., smakować (to taste), were remembered worse.

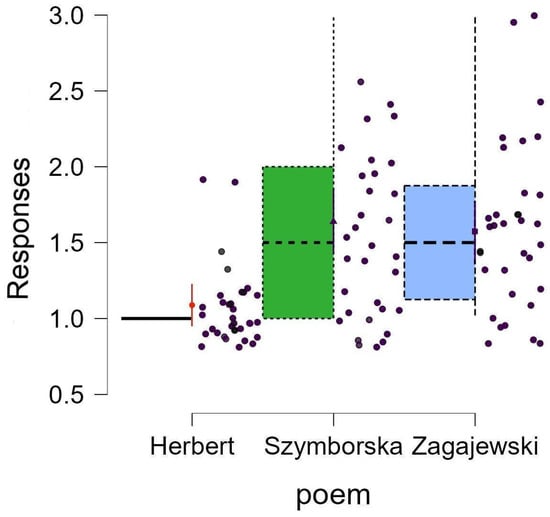

8.6. Topic Inferential Task (TIT)

TIT revealed a main effect of a poem in favor of Herbert’s text compared to the other two (Figure 3). The response accuracy to Herbert’s verses was substantially higher, approaching the ceiling effect (B = 0.985; CI95% = [0.577, 1.000]), whereas responses to Szymborska’s (B = 0.575; CI95% = [0.434, 0.705]) and Zagajewski’s (B = 0.530; CI95% = [0.410, 0.646]) poems were more evenly divided. No reliable effects of priming pairs or priming pair x poem were observed.

Figure 3.

Responses distribution in the Topic Inferential Task by authors: Herbert (black), Szymborska (green), and Zagajewski (blue).

9. Discussion and Conclusions

The present pilot study aimed to develop and test a psycholinguistic battery tailored for the empirical investigation of Polish poetry processing. Our goals were 1. to create a tool for linguistic profiling of readers and 2. to explore how lexical, textual, affective, and poetic word properties influence cognitive and behavioral responses.

RQ1.

What means are best-fitted for comprehensive empirical study of modern poetry?

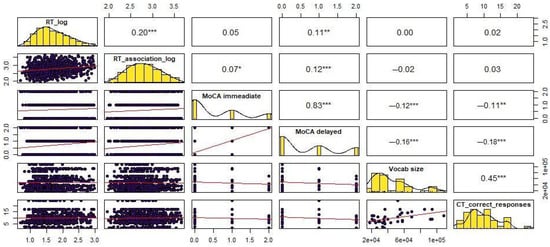

As preliminary measures, we selected the SLS-Berlin Reading Proficiency Test (Lüdtke et al. 2019), Vocabulary Size test (Fokin et al. 2025), and verbal MoCA subscale (Gierus et al. 2015), all previously shown to measure crucial text comprehension skills (Chateau and Jared 2000; Just and Carpenter 1980; Matchin et al. 2024). The control experiments included the Context-Primed Associations Task (CPAT), the Cloze-Test (CT), and the Topic Inferential Task (TIT), intended to measure verbatim and content memory, associative processes, participants’ ability to restore the context, and topic inference. The correlations among the scores of all tests included in the study are summarized in Figure 4, revealing potentially similar cognitive processes underlying word remembrance and associative mechanisms related to delayed memory recall. Contextual word restoration, in turn, requires activation of the mental lexicon and verbal memory, resulting in a strong association between the Cloze Test scores and the MoCA and PVST results.

Figure 4.

Pearson’s correlation on scores in the test battery. (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

The Polish Reading Proficiency Test (PRPT) showed a moderate-to-strong correlation with the German original and consistent relations between sentence-level features, supporting its validity for further application. Yet, PRPT proved easier: in contrast to the German original, which strongly predicted score differences (r = −0.850, p < 0.001), our adaptation did not (r = −0.074; p = 0.524), evidencing its reduced sensitivity.

We observe moderate-to-strong associations between 1. immediate and delayed lexical rehearsal (r = 0.83); 2. weak but statistically significant links between P-MoCA delayed scores and the vocabulary size (r = −0.18), recognition memory (r = −0.11), and association generation times (r = −0.12); 3. moderately strong association between times in recognition and association generation tasks (r = 0.20) (CPAT); 4. strong connection between context restoration scores and the vocabulary size (r = 0.45).

The Topic Inferential Task (TIT) showed an imbalance in design, leading to uneven responses across poems and no expected priming effects. However, TIT’s results may illustrate differences in topic distinguishing: the semantic mainline in Herbert’s poem—the disappearance of the narrator’s father—is depicted in a more straightforward way, while the meanings of Szymborska’s and Zagajewski’s poems are more fuzzy and dispersed, with no pronounced main topic. Thus, the results may demonstrate the higher semantic and narrative coherence in the first poem compared to the last two, and participants identify it more easily. However, since TIT did not demonstrate the expected priming effects, we decided to remove it from the battery until calibrated. This will also streamline the test battery and reduce participants’ cognitive load.

To sum up, we confirmed our hypothesis by revealing the capability of the proposed test battery to capture meaningful links across the measures, supporting the feasibility of this two-step design for further studies. PRPT requires further calibrations and stimulus set refinements, and TIT, in its current form, cannot yet capture topic inference. Overall, the combined battery demonstrates strong potential for linguistic profiling of readers and examining memory, vocabulary size, and associative processes.

RQ2.

How does reading modern poetry impact cognitive processes involved in verbatim and content remembrance, associative processes, and topic identification?

We hypothesized that the control experiments in their current state may capture differences in verbatim memory, content remembrance, and the generation of associations.

The main finding is a moderately strong interaction between word recognition and association–generation times (Figure 3), with no relation to context recall times. Two perspectives may account for this. First, textual information is stored in an episodic buffer (Baddeley 2000, 2003), from which it can later be extracted, and the storage process relies on the similar cognitive functioning that supports lexical retrieval from long-term memory. Second, quick and correct recognition responses may prime the associative network through preactivation, enabling faster retrieval of associations. By contrast, context recall was intentionally designed as a filler to reduce guessing, but it also demands recalling large pieces of textual representations, which are likely stored in the intermediate-term memory (Kamiński 2017), where participants often fail (see below).

The Context-Primed Associations Test’s results suggest that readers likely construct a situation model (Zwaan and Radvansky 1998)—a mental representation of a poem’s narrative, imagery, and structure. However, the latest model proposed by Zwaan (Zwaan 2025) cannot fully explain the observed relations. Our results imply the presence of an intermediate memory store, where larger chunks of textual information might be maintained. This store appears to be a buffer between short-term memory, accessed via a recognition memory task, and long-term memory, engaged during the association generation. It seems task-dependent: knowing the upcoming task, readers initiate attention-guiding mechanisms (e.g., Moss and Schunn 2015). It allows them to retrieve poem-specific information beyond standard working-memory limits (Baddeley 2003). Thus, comprehenders request a situation model through this buffer, performing both working- and long-term memory-related tasks. The quality of this model shapes both recognition accuracy and association generation, which emphasizes mental simulation of time, space, and causality. It is further evidenced from low but significant correlations between recognition and association generation times and delayed memory rehearsal, with no relation to immediate recall.

Context recall is strongly related to vocabulary size and delayed memory rehearsal. It suggests that CT requires additional cognitive consumption, accessing textual representations, appropriate word selection, and then grammatical manipulations with selected items (Appendix A, Table A8). In line with Rugg et al. (1998), who showed that recognition is more accurate than recall and both involve distinct neural activities, our findings confirm: CT taps into long-term memory processes but not word recognition alone and draws the situation model for retrieval and usage of a context when filling the gaps.

Yet, the participants’ mean performance in CT was low (M = 0.334), approaching a floor effect. To evaluate whether it is a task-design issue, we applied a Rasch model (R Core Team 2025; Robitzsch et al. 2020). It enables observing how well stimuli fit the measured dimension, i.e., the ability to restore poetic content. The model indicated trustworthy item functioning (EAP Reliability = 0.792; Correlations = 0.975; Appendix A, Table A7; Supplementary Materials). High item and person fit suggest that CT reliably measures participants’ ability to restore poetic content, despite overall low scores.

These low scores may instead reflect properties of modern poetry itself: lack of coherence, resistance to prediction, and high cognitive demand. Participants inexperienced in modern poetry reading may additionally struggle to use contextual cues and text coherence to restore the content. Unlike rhymed or metered verse, which offers prosodic regularities that aid memory (e.g., Lea et al. 2021), the selected poems were rich in syntactic interruptions, enjambments, and semantic complexity. Moreover, preliminary Exploratory Factor Analysis on the lexical content (Fokin, forthcoming) revealed the prevalence of abstract, hard-to-imagine, and calm words with an increase in perceived significance, engaged in the abstract–significance continuum. Such forms of lexical content contain a foreground trajectory of perception (Kuiken and Shawn 2017), challenging participants and requiring reflective and close reading. Non-expert readers, in turn, may not be intended for in-depth analysis or puzzle-solving, preferring unambiguous communication (Porter and Machery 2024). Additionally, they lack clear “reference points” to build a qualitative textual representation. As a result, readers fail in successful content restoration due to the lack of expertise, motivation, and inference skills.

It is worth noting the poem’s influence on participants’ memory: words from Zagajewski’s poem were better recognized, while its content was less accurately restored. This may illustrate the phenomenon of foregrounding: Zagajewski’s text is non-uniform, with numerous punctuation marks and a disproportion between long and short lines. The absence of a clear narrative streamline disrupts attention, making it dispersed. As a result, some particular words are remembered, whereas the content is not. Such structural complexity makes it difficult to form a coherent mental image of the piece, yet at the same time, it captures attention, which may facilitate short-term retention of individual words.

In sum, consistent with our hypothesis, the proposed tests show promise in capturing memory-based processes in poetry reading. Although certain tasks require refinement and the full battery may need adjustment to reduce cognitive load, the study yielded valuable insights. First, cognitive processes involved in reading Polish poetry appear to align with those observed for linguistic materials in other languages, indicating potential universality in language processing mechanisms. Our participants were inexperienced poetry readers, and thus their responses may reflect general, background-independent mechanisms of poetry reception—processing poetry much like other texts. Linguistic properties of words modulate memory encoding and retrieval, either facilitating or complicating them. Importantly, we observed that poetic devices and affective word properties—unique to each poem and to Polish poetic language—modulate contextual restoration. This finding demonstrates that readers are guided by the poem’s affective contour, which directs attention and triggers specific behavioral responses. In this sense, the stimuli (poems) and readers’ responses (words) are both unique and language-dependent. Our findings thus provide novel cognitive and behavioral evidence of how readers engage with Polish poetic texts.

RQ3.

What is the role of textual, lexical, poetic, and affective features in framing these effects?

We hypothesized that affective word features are key drivers in poetry reception; word position in line is a salient predictor of remembrance, being refined by poetic tropes, and lexical word properties are subordinated by affective ones, which can either enhance or diminish the impact of lexical properties.

The main discovery here is the central role of word line position in recognition and association–generation processes. More accurate responses in the recognition task (CPAT) are linked with faster responses to line-final words compared to middle words (Appendix A, Table A4). This result aligns with earlier findings in neurocognitive poetics (Fechino et al. 2020; Jacobs 2015; Lüdtke et al. 2014) and empirical stylistics (Menninghaus and Wallot 2021), showing that final words are often semantically loaded and foregrounded (e.g., through rhyme or enjambment). Such words are likely more memorable due to wrap-up and savoring effects (Jacobs 2014; Menninghaus and Wallot 2021). Readers anticipate closure and therefore allocate more attention to the line’s end, while middle words remain less salient and attract less focus.

However, association–generation shows a different pattern. Here, word position is modulated by lexical properties such as word length and frequency. Contrary to recognition, final words slow down associative generation (B = 0.237, SE = 0.052; t = 4.525, Supplementary Materials). This may stem, again, from their poetic foregrounding: while recognition can be facilitated by familiarity, association becomes more difficult if these words carry semantic weight, involve syntactic disruption (e.g., via enjambment), or create incoherent textual representations that reduce priming effects. The negative effect of line-final position is reduced by length, with short final words leading to quicker associations. Likewise, length × frequency interactions show that short, high-frequency words accelerate association production. Taken together, these results demonstrate that word position and fundamental lexical properties are key predictors of memory-based and associative processes. They may reflect principles described by Kolmogorov and Zipf (Ehret 2018; Linders and Louwerse 2023) as well as known mechanisms of memory retrieval and storage (Baddeley 2003; Lea et al. 2021; Rosenzweig et al. 1993; Rugg et al. 1998): short and high-frequency items are easier to identify, remember, and manipulate. Readers focus more on foregrounded elements (see Kuiken and Jacobs 2021; Hakemulder et al. 2025; Hakemulder 2004), making them easier to recognize because of their salience. Yet, when accessing long-term lexical storage, these same elements can hinder retrieval, while basic lexical properties such as length and frequency reliably reduce the negative effects of line position.

Finally, short and negatively valenced words were restored more accurately in CT compared to positive or long-word items. Moreover, an increase in valence (words becoming more positively-colored) decreased the negative effect of long words, leading to higher accuracy. Higher remembrance of negatively-colored words was previously observed by Inaba et al. (2005), and our results are aligned with the prior ones.

Analysis of affective features revealed the crucial role of arousal, imaginability, and concreteness, as well as their interactions. Hardly imagined and abstract words were better restored than concrete and easy-to-imagine ones, contrasting well-established patterns that concrete and imaginative words are better understood, imagined, and remembered (Aka et al. 2021; Altarriba et al. 1999; Imbir 2016). The effect of arousal was moderated by imaginability, reflecting that imaginative content plays a greater role than emotional arousal in poetry processing. A possible explanation here is that abstract and hard-to-imagine words may induce associative and reflective processes—a kind of mind-drift—and readers may react to them as semantically salient or foregrounded figures (see Fokin, forthcoming). Previously, we assumed that CT involves multi-step cognitive processes. Thus, only here do we observe the impact of affective items, suggesting that when restoring content, participants may access long-term lexical storage, and abstract words may trigger larger networks than concrete and familiar ones. So, despite failing to confirm a prominent role of affective features in overall memory processes, we revealed their importance for high-order lexical manipulations and access. We also established the key role of word position in line on readers’ memory, suggesting the importance of visuo-spatial organization for memory-based functions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/literature5040028/s1, Figure S1: Scatter plot of the Means of German and Polish Reading Proficiency Tests; Table S1: Estimated marginal means in the recognition task in CPAT; Table S2: Estimated Marginal Means of arousal x imageability on response accuracy (CT).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F., Ł.W. and M.P.; methodology, D.F., Ł.W. and M.P.; software, D.F.; validation, D.F.; formal analysis, D.F.; investigation, D.F.; resources, D.F., Ł.W. and M.P.; data curation, D.F.; writing—original draft preparation, D.F.; writing—review and editing, D.F., Ł.W. and M.P.; visualization, D.F.; supervision, Ł.W. and M.P.; project administration, D.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Committee for the Ethics of Research Involving Human Participants of the University of Warsaw (No. 272/2024, 2 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants signed informed consents to participate in the study and consent to the processing of personal data.

Data Availability Statement

All the materials are available via https://osf.io/rp3xz/.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of 77 Polish sentences and their German original.

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics of 77 Polish sentences and their German original.

| 95% CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polish Mean (SD) | German Mean (SD) | t | p | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| number of letters | 64.03 (19.19) | 74.36 (17.80) | −4.7244 | 1.036 × 10−5 | 59.669 | 68.382 |

| number of syllables | 26.68 (8) | 25.38 (5.72) | 1.421 | 0.159 | 24.86 | 28.491 |

| number of words | 9.81 (2.75) | 10.96 (2.91) | −3.687 | <0.000 | 9.181 | 10.429 |

| number of long words (>6 letters) | 4.96 (1.96) | 4.27 (1.46) | 3.089 | 0.003 | 4.515 | 5.407 |

Table A2.

Pearson’s correlations between MoCA scores and memory-related variables.

Table A2.

Pearson’s correlations between MoCA scores and memory-related variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MoCA_immediate | Pearson’s r | — | ||||

| 2. Vocabulary Size | Pearson’s r | −0.124 *** | — | |||

| 3. MoCA_delayed | Pearson’s r | 0.832 *** | −0.162 *** | — | ||

| 4. Response Time_recognition | Pearson’s r | 0.049 | −0.002 | 0.110 ** | — | |

| 5. Response Time_associations | Pearson’s r | 0.070 | −0.016 | 0.117 *** | 0.198 *** | — |

Note. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Statistically significant correlations are bolded.

Table A3.

Anova summary of General Linear Mixed-Model on response accuracy in CPAT.

Table A3.

Anova summary of General Linear Mixed-Model on response accuracy in CPAT.

| Effect | df | ChiSq | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1 | 29.188 | <0.001 |

| position_in_line | 1 | 7.040 | 0.008 |

| log(response time) | 1 | 15.076 | <0.001 |

| position in line × log(RT) | 1 | 5.276 | 0.022 |

Note. ID (36) was used as a random factor with 409 observations. A binomial general mixed model was employed, and accuracy was used as a dependent factor tested with the likelihood ratio test method. Model fit is singular, which might inflate the reported p-value.

Table A4.

Anova summary of Linear Mixed-Model on response time in the Free Association Task in CPAT.

Table A4.

Anova summary of Linear Mixed-Model on response time in the Free Association Task in CPAT.

| Term | df | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| length | 1, 76.78 | 0.117 | 0.773 |

| position in line | 1, 105.55 | 20.472 | <0.001 |

| word frequency | 1, 65.54 | 3.335 | 0.072 |

| Length × position in line | 1, 279.23 | 12.175 | <0.001 |

| Length × word frequency | 1, 46.78 | 8.121 | 0.006 |

Table A5.

Estimated Marginal Means of length × valence on response accuracy (CT).

Table A5.

Estimated Marginal Means of length × valence on response accuracy (CT).

| CI 95% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length | Valence | Estimate_Accuracy (SE) | Lower | Upper |

| 4.604 | 4.432 | 0.697 (0.055) | 0.581 | 0.793 |

| 6.502 | 4.432 | 0.464 (0.044) | 0.380 | 0.551 |

| 8.399 | 4.432 | 0.246 (0.036) | 0.181 | 0.324 |

| 4.604 | 5.549 | 0.570 (0.43) | 0.484 | 0.652 |

| 6.502 | 5.549 | 0.393 (0.35) | 0.326 | 0.463 |

| 8.399 | 5.549 | 0.240 (0.37) | 0.175 | 0.320 |

| 4.604 | 6.666 | 0.432 (0.54) | 0.330 | 0.540 |

| 6.502 | 6.666 | 0.327 (0.43) | 0.248 | 0.417 |

| 8.399 | 6.666 | 0.237 (0.49) | 0.154 | 0.346 |

Note. responses are not on the response scale. Significant changes in rates are bolded.

Table A6.

Estimated Marginal Means of imageability × concreteness on response accuracy (CT).

Table A6.

Estimated Marginal Means of imageability × concreteness on response accuracy (CT).

| CI 95% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imageability | Concreteness | Estimate (SE) | Lower | Upper |

| 5.553 | 2.082 | 0.319 (0.123) | 0.134 | 0.587 |

| 5.553 | 2.082 | 0.407 (0.072) | 0.276 | 0.552 |

| 5.553 | 2.082 | 0.501 (0.055) | 0.394 | 0.607 |

| 6.810 | 3.628 | 0.353 (0.066) | 0.236 | 0.491 |

| 6.810 | 3.628 | 0.296 (0.042) | 0.220 | 0.385 |

| 6.810 | 3.628 | 0.345 (0.054) | 0.155 | 0.365 |

| 8.066 | 5.175 | 0.388 (0.066) | 0.268 | 0.523 |

| 8.066 | 5.175 | 0.205 (0.058) | 0.114 | 0.343 |

| 8.066 | 5.175 | 0.095 (0.044) | 0.037 | 0.223 |

Note. responses are not on the response scale. Significant changes in rates are bolded.

Table A7.

The dichotomous Rasch model summary on CT responses.

Table A7.

The dichotomous Rasch model summary on CT responses.

| Metrics | Statistics |

|---|---|

| Deviance | 1005.08 |

| Log Likelihood | −502.54 |

| AIC | 1065 |

| BIC | 1113 |

| EAP Reliability | 0.792 |

| Variance | 0.951 |

| Correlations | 0.975 |

| Regression Coefficients | 0 |

Note. EAP Reliability reflects the precision of the model; Covariances is the variance of the latent dimension; Correlations are connections between latent dimensions.

Table A8.

Stimuli difficulties assessment based on Rasch modelling.

Table A8.

Stimuli difficulties assessment based on Rasch modelling.

| Item | English | Mean | xsi_ Difficulty | Item | English | Mean | xsi_ Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| zagubione | lost (adj.pl.) | 0.027 | 4.044 | żyję | to live (1 pers. sing.) | 0.297 | 1.016 |

| przenika | to penetrate (3pers.sing.) | 0.054 | 3.278 | głowę | head (sing.acc.) | 0.324 | 0.876 |

| smakował | to taste | 0.056 | 3.255 | zdejmował | to take off (past. 3 pers.sing.) | 0.389 | 0.534 |

| starości | old age (sing. gen.) | 0.081 | 2.806 | zdjęto | removed (past. impers.) | 0.389 | 0.534 |

| Wstyd | shame | 0.108 | 2.454 | odwrócił | to turn around (past pers.sing.) | 0.417 | 0.395 |

| odległych | distant (pl.loc.) | 0.111 | 2.426 | oczy | eyes (pl.acc.) | 0.444 | 0.260 |

| kochałiście | to love (2.pers. pl.) | 0.135 | 2.168 | światło | light (sing.acc.) | 0.459 | 0.187 |

| glina | clay (nom.sing) | 0.162 | 1.925 | ścianie | wall (sing.loc.) | 0.514 | −0.071 |

| przedmiotów | objects (pl.gen.) | 0.189 | 1.710 | apetytu | appetite (sing.gen.) | 0.514 | −0.071 |

| powietrza | air (sing.gen.) | 0.189 | 1.710 | ojciec | father (1 pers. sing.) | 0.583 | −0.409 |

| słodko | sweet (adv.) | 0.189 | 1.710 | dywanie | carpet (sing.loc.) | 0.583 | −0.409 |

| wieczności | eternity (sing.acc.) | 0.216 | 1.517 | palmy | palms (pl.nom.) | 0.583 | −0.409 |

| szarej | grey (sing.fem.loc.) | 0.243 | 1.339 | trzystu | three hundred (sing.gen.) | 0.676 | −0.878 |

| krople | drops (pl.acc.) | 0.278 | 1.132 | rzeczy | things (pl.acc.) | 0.892 | −2.444 |

| trwa | to last (3 pers.sing.) | 0.919 | −2.791 |

Note. The greater the difficulty, the less often participants responded correctly. Thus, “trwa” was accurately filled by most of the readers, whereas “zagubione” was filled by only a few. One item (cichutko) was excluded from the analysis due to the absence of the correct responses.

Notes

| 1 | Concreteness is a reversed scale. Thus, a higher concreteness rate is associated with abstract words. |

| 2 | For the entire list of word properties, please consult Removed for peer review. |

| 3 | Both “imaginability” and “concreteness” scales are reversed. Thus, scores of hard-to-imagine items are lower, cf. czas (time) 4.78 vs. niebieski (blue) 8.14; abstract words have higher scores, cf. jedzenie (meal) 2.5 vs. nuda (boredom) 6.28. |

References

- Aitchison, Jean. 1987. Words in the Mind: An Introduction to the Mental Lexicon. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Aka, Ada, Tung D. Phan, and Michael J. Kahana. 2021. Predicting recall of words and lists. Journal of Experimental Psychology Learning, Memory, and Cognition 47: 765–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alber, Jan, and Sven Strasen. 2020. Empirical Literary Studies: An Introduction. Anglistik 31: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarriba, Jeanette, Lisa M. Bauer, and Claudia Benvenuto. 1999. Concreteness, context availability, and imageability ratings and word associations for abstract, concrete, and emotion words. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 31: 578–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstatt, Tanja. 2008. Wer “dunkel” hört, muss nicht “hell” sagen: Wortassoziationen in slavischen und germanischen Sprachen. In Slavistische Linguistik 2006/2007: Referate des XXXII. und XXXIII. Konstanzer Slavistischen Arbeitstreffens (Slavistische Beiträge, t. 464). Edited by Peter Kosta and Daniel Weiss. München: Otto Sagner, pp. 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Aryani, Arash, Maria Kraxenberger, Susan Ullrich, Arthur M. Jacobs, and Conrad Marcus. 2016. Measuring the basic affective tone of poems via phonological saliency and iconicity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 10: 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, Alan. 2000. The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4: 417–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baddeley, Alan. 2003. Working memory: Looking back and looking forward. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 4: 829–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, Judith, and Lars Konieczny. 2021. Rhythmic subvocalization: An eye-tracking study on silent poetry reading. Journal of Eye Movement Research 13: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blohm, Stefan, Stefano Versace, Sanja Methner, Valentin Wagner, Matthias Schlesewsky, and Winfried Menninghaus. 2022. Reading poetry and prose: Eye movements and acoustic evidence. Discourse Processes 59: 159–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickey, Alyson. 2022. Aesthetic Unrest: “Howl” and the Literary List. In Forms of List-Making: Epistemic, Literary, and Visual Enumeration. Edited by Barton Roman Alexander, Böckling Julia, Link Sarah and Rüggemeier Anne. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 171–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brône, Geert, and Jeroen Vandaele, eds. 2009. Cognitive Poetics: Goals, Gains and Gaps. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, Kate, and Jane Oakhill. 1999. Inference making ability and its relation to comprehension failure in young children. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal 11: 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, Kate, Jane Oakhill, and Kate Lemmon. 2004. Individual Differences in the Inference of Word Meanings From Context: The Influence of Reading Comprehension, Vocabulary Knowledge, and Memory Capacity. Journal of Educational Psychology 96: 671–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chateau, Dan, and Debra Jared. 2000. Exposure to print and word recognition processes. Memory & Cognition 28: 143–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M. Alan, and Elizabeth F. Loftus. 1975. A spreading-activation theory of semantic processing. Psychological Review 82: 407–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, Keith. 2023. Psychoacoustic Similarity Judgments in Expert Rappers and Laypersons. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 52: 1141–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, Keith, and Takako Fujioka. 2019. Auditory rhyme processing in expert freestyle rap lyricists and novices: An ERP study. Neuropsychologia 129: 223–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czapliński, Przemysław, and Piotr Śliwiński. 2000. Literatura polska 1976–1998: Przewodnik po Prozie i Poezji. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- De Beaugrande, A. Robert, and Wolfgang Dressler. 1982. Introduction to Text Linguistics. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Delente, Éliane. 2024. A Temporal and Dynamic Approach to Enjambments in French Versified Poetry from the 17th to the late 19th Century Studia. Metrica et Poetica 11: 45–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duch, Włodzisław, Paweł Matykiewicz, and John P. Pestian. 2008. Neurolinguistic approach to natural language processing with applications to medical text analysis. Neural Networks: The Official Journal of the International Neural Network Society 21: 1500–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehret, Katharina. 2018. Kolmogorov Complexity as a Universal Measure of Language Complexity. Available online: https://www.christianbentz.de/MLC2018/Ehret.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Fechino, Merion, Arthur M. Jacobs, and Jana Lüdtke. 2020. Following in Jakobson and Levi-Strauss’ footsteps: A neurocognitive poetics investigation of eye movements during the reading of Baudelaire’s ‘Les Chats’. Journal of Eye Movement Research 13: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokin, Danil. Forthcoming. The Depth beyond the Lines: Key Linguistic Features of three Polish poems. Studia Metrica et Poetica 12.

- Fokin, Danil, Monika Płużyczka, and Grigory Golovin. 2025. The Polish Vocabulary Size Test: A new tool of the receptive vocabulary size assessment. Behavioral Research Methods 57: 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokin, Danil, Stefan Blohm, and Elena Riekhakaynen. 2022. Reading Russian Poetry: An expert-novice study. Journal of Eye Movement Research 13: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Chunhai, and Cheng Guo. 2018. The Experience of Beauty of Chinese Poetry and Its Neural Substrates. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawarkiewicz, Robert, ed. 2024. Polski słownik asocjacyjny. Dwie dekady (t. 1: Od bodźca do reakcji; t. 2: Od reakcji do bodźca). Szczecin: Wydawnictwo Naukowe US. Available online: https://wnus.usz.edu.pl/asocjacyjny1/pl/issue/1399/ (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Geyer, Thomas, Franziska Günther, Hermann J. Müller, Jim Kacian, Heinrich René Liesefeld, and Stell Pierides. 2020. Reading English-language haiku: An eye-movement study of the ‘cut effect’. Journal of Eye Movement Research 13: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierus, Jan, Andrzej Mosiołek, Tomasz Koweszko, Anna Kozyra, Piotr Wnukiewicz, Bogdan Łoza, and Andrzej Szulc. 2015. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment 7.2—Polish adaptation and research on equivalency. Psychiatria Polska 49: 171–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovin, Grigory. 2015. Izmerenie passivnogo slovarnogo zapasa russkogo yazyka [Receptive vocabulary size measurement for Russian language]. Socio-Ipsiholingvisticheskie Issledovaniya [Socio-Psycholinguistic Research] 3: 148–59. [Google Scholar]

- Goroshko, Elena I. 2001. Integrativnaya Model’ Svobodnogo Assotsiativnogo Eksperimenta [Integration Model of the Free Associations Test]. Available online: https://www.textology.ru/article.aspx?aId=90#r1 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Grabska-Gradzińska, Iwona, Anna Kulig, Jędrzej Kwapień, and Stanisław Drożdż. 2012. Complex network analysis of literary and scientific texts. International Journal of Modern Physics C 23: 1250051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakemulder, Frank, Amir Harash, and Julia Scapin. 2025. Foregrounding. In The Routledge Companion to Literature and Cognitive Studies, 1st ed. Edited by Jan Alber and Ralf Schneider. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakemulder, Frank, and Anna Mangen. 2024. Literary Reading on Paper and Screens: Associations Between Reading Habits and Preferences and Experiencing Meaningfulness. Reading Research Quarterly 59: 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakemulder, J. Frank. 2004. Foregrounding and its effect on readers’ perception. Discourse Processes 38: 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanauer, David. 1998. Genre-specific hypothesis of reading: Reading poetry and encyclopedic items. Poetics 26: 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, Franziska, Peter Withers, Peter Hagoort, and Roel M. Willems. 2017. When Fiction Is Just as Real as Fact: No Differences in Reading Behavior between Stories Believed to be Based on True or Fictional Events. Frontiers in psychology 8: 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugentobler, Katrin G., and Jana Lüdtke. 2021. Micropoetry Meets Neurocognitive Poetics: Influence of Associations on the Reception of Poetry. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 737756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutnikiewicz, Artur, and Andrzej Lam, eds. 2000. Literatura Polska XX Wieku: Przewodnik Encyklopedyczny. T. 1–2. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Imbir, K. Kamil. 2016. Affective Norms for 4900 Polish Words Reload (ANPW_R): Assessments for Valence, Arousal, Dominance, Origin, Significance, Concreteness, Imageability and Age of Acquisition. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, Midori, Michio Nomura, and Hideki Ohira. 2005. Neural evidence of effects of emotional valence on word recognition. International Journal of Psychophysiology 57: 165–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Arthur M. 2014. Towards a Neurocognitive Poetics model of Literary Reading. In Cognitive Neuroscience of Natural Language Use. Edited by Roel Willems. Cambridge: Cambridge Editors, pp. 135–59. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Arthur M. 2015. Neurocognitive poetics: Methods and models for investigating the neuronal and cognitive-affective bases of literature reception. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 9: 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, Arthur M., and Annette Kinder. 2018. What makes a metaphor literary? Answers from two computational studies. Metaphor and Symbol 33: 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobson, Roman. 1975. Lingwistika i poetika. [Linguistics and Poetics]. In Strukturalizm Za i Protiv. [Structuralism. Pro et Contra]. Edited by E. Basin and M. Polyakov. London: Palgrave, pp. 193–231. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, Roman. 1976. Hölderlin, Klee, Brecht: Zur Wortkunst dreier Gedichte. Berlin: Suhrkamp Taschenbuch Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Jakubíček, Michal, Adam Kilgarriff, Václav Kovář, Pavel Rychlý, and Václav Suchomel. 2013. The TenTen corpus family. Paper presented at 7th International Corpus Linguistics Conference CL, Valletta, Malta, May 13–15; pp. 125–27. [Google Scholar]

- JASP Team. 2023. JASP (Version 0.18.3) [Computer Software]. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Johnson-Laird, Philip N., and Keith Oatley. 2022. How poetry evokes emotions. Acta Psychologica 224: 103506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Just, Marcel A., and Patricia A. Carpenter. 1980. A theory of reading: From eye fixations to comprehension. Psychological Review 87: 329–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiński, Jan. 2017. Intermediate-Term Memory as a Bridge between Working and Long-Term Memory. Journal of Neuroscience 37: 5045–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Justine, and Dan Jurafsky. 2012. A computational analysis of style, affect, and imagery in contemporary poetry. Paper presented at NAACL-HLT 2012 Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Literature, Montréal, QC, Canada, June 8; pp. 8–17. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/W12-2502/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Kim, Young-Suk G. 2020. Toward Integrative Reading Science: The Direct and Indirect Effects Model of Reading. Journal of Learning Disabilities 53: 469–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köbis, Nils, and Luca D. Mossink. 2021. Artificial intelligence versus Maya Angelou: Experimental evidence that people cannot differentiate AI-generated from human-written poetry. Computers in Human Behavior 114: 106553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraxenberger, Maria, and Winfried Menninghaus. 2017. Affinity for Poetry and Aesthetic Appreciation of Joyful and Sad Poems. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiken, Donald, and Arthur M. Jacobs, eds. 2021. Handbook of Empirical Literary Studies. Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 145–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiken, Donald, and Douglas Shawn. 2017. Forms of absorption that facilitate the aesthetic and explanatory effects of literary reading. In Narrative Absorption. Edited by Frank Hakemulder, Moniek M. Kuijpers, Ed S. Tan, Katalin Bálint and Miruna M. Doicaru. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, pp. 217–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawik, Adam. 1994. Poetyka: Wstęp do Dzieła Literackiego [An Introduction to the Literary Activity]. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Antykwa. [Google Scholar]

- Kuperman, Victor, Marcus Dambacher, and Antje Nuthmann. 2010. The effect of word position on eye-movements in sentence and paragraph reading. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 63: 1838–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuperman, Victor, Simon Schroeder, and Daniil Gnetov. 2024. Word length and frequency effects on text reading are highly similar in 12 alphabetic languages. Journal of Memory and Language 135: 104497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperman, Victor, Zev Estes, Marc Brysbaert, and Abigail B. Warriner. 2014. Emotion and language: Valence and arousal affect word recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 143: 1065–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurcz, Ida. 1967. Polskie normy powszechności skojarzeń swobodnych na 100 słów z listy Kent–Rosanoffa. Studia Psychologiczne 8: 122–255. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, Peter J. 1980. Behavioral treatment and bio-behavioral assessment: Computer applications. In Technology in Mental Health Care Delivery Systems. Edited by Joseph B. Sidowski, James Harding Johnson and Thomas A. Williams. Norwood: Ablex, pp. 119–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lauer, Gerhard. 2015. Introduction: Empirical Methods in Literary Studies. Journal of Literary Theory 9: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, R. Brooke, Andrew Elfenbein, and David N. Rapp. 2021. Rhyme as resonance in poetry comprehension: An expert–novice study. Memory and Cognition 49: 1285–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestrade, Stéphane. 2017. Unzipping Zipf’s law. PLoS ONE 12: e0181987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexical Computing CZ s.r.o. n.d. SketchEngine V. 2024; Sketch Engine. Brno-Královo Pole: Lexical Computing CZ s.r.o. Available online: https://www.sketchengine.eu/ (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Lime Survey GmbH. 2023. Lime Survey (Version 6.4). Available online: https://www.limesurvey.org/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Linders, Guiso M., and Max M. Louwerse. 2023. Zipf’s law revisited: Spoken dialog, linguistic units, parameters, and the principle of least effort. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 30: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, David L., Michael J. Oppy, and Michael R. Seely. 1997. Individual differences in readers’ sentence- and text-level representations. Journal of Memory and Language 36: 129–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdtke, Jana, Bettina Meyer-Sickendieck, and Arthur M. Jacobs. 2014. Immersing in the stillness of an early morning: Testing the mood empathy hypothesis of poetry reception. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 8: 363–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdtke, Jana, Eva Froehlich, Arthur M. Jacobs, and Frank Hutzler. 2019. The SLS-Berlin: Validation of a German Computer-Based Screening Test to Measure Reading Proficiency in Early and Late Adulthood. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukin, Vladimir. A. 1999. Hudojhestvennyj Tekst I Sredstva ego Analiza. [The Literary Text and Tools of Its Analysis]. Moscow: Os’-89.

- Mangen, Anne, and Donald Kuiken. 2014. Lost in an iPad: Narrative engagement on paper and tablet. Scientific Study of Literature 4: 150–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastalski, Andrzej S. 2023. O przerzutni. [On Enjambment]. Zagadnienia Rodzajów Literackich the Problems of Literary Genres 66: 157–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matchin, William, Zeinab K. Mollasaraei, Leonardo Bonilha, Christofer Rorden, Gregory Hickok, Dirk Den Ouden, and Julius Fridriksson. 2024. Verbal working memory and syntactic comprehension segregate into the dorsal and ventral streams, respectively. Brain Communications 6: fcae449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, Kathryn S., Marco van de Ven, Jacqueline Evers-Vermeul, Eliane Segers, and Paul van den Broek. 2024. Cognitive perspectives on the role of genre in reading comprehension. In Multidisciplinary Views on Discourse Genre: A Research Agenda, 1st ed. Edited by Ninke Stukker, John A. Bateman, Danielle McNamara and Wilbert Spooren. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcgee, Lea M. 1981. Effects of the Cloze Procedure on Good and Poor Readers’ Comprehension. Journal of Reading Behavior 13: 145–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]