Abstract

While fictional orality (spoken language in fictional texts) has received some attention in the context of quantitative register studies at the interface of linguistics and literature, only a few attempts have been made so far to apply the quantitative methods of register studies to interior monologues (and other forms of inner speech or thought representation). This article presents a case study of the three main characters of James Joyce’s Ulysses whose thoughts are presented extensively in the novel, i.e., Leopold and Molly Bloom and Stephen Dedalus. Making use of quantitative, corpus-based methods, the thoughts of these characters are compared to fictional direct speech and (literary and non-literary) reference texts. We show that the interior monologues of Ulysses span a range of non-narrative registers with varying degrees of informational density and involvement. The thoughts of one character, Leopold Bloom, differ substantially from that character’s speech. The relative heterogeneity across characters is taken as an indication that interior monologue is used as a means of perspective taking and implicit characterization.

1. Introduction

Studies on the linguistic aspects of spoken language in literary works have a long pedigree, and they continue to be of interest to scholars working at the interface of literary studies and linguistics (see, for instance, DeVito 1963, p. 354; Burton 1980; Akinnaso 1982, pp. 121–25; Erzgraeber and Goetsch 1987; Goetsch 1985, 1987; Fludernik 1986, 2005; Mace 1987; Bishop 1991; Erzgraeber 1998; Thomas 2012; Bublitz 2017; Egbert and Mahlberg 2020; Jucker 2021—among others). Goetsch (1985) used the term ‘fingierte Mündlichkeit’—fictional orality—for this mode. The relevant studies typically focus on two comparisons, the differences between authentic speech and its fictionalization, and the contrast between narrative and spoken passages of literary works.

The discussion of fictional orality has often revolved around the mimesis debate, i.e., the extent to which fictional speech succeeds in emulating natural conversation (or even whether it intends to) (e.g., Bishop 1991, pp. 59–61; Leech and Short 1991, pp. 159–66; Fludernik 1993, p. 281; Thomas 2012, pp. 15–16). There is general consensus among critics that, due to aesthetic reasons but also because of the different productive circumstances underlying the two modes of communication, literary dialogue represents, at best, an approximation of authentic orality but can by no means be considered the equivalent of a transcript of a tape-recorded speech sequence. While fictional orality may, to some extent, strive to emulate real-world conversational behavior, it is obvious that the imperfections of authentic speech and the plethora of phatic elements (interjections, fillers, pauses) found in everyday conversation are not normally represented in fictional orality (there are, of course, exceptions, such as William Gaddis’s novel J R). Obviously, there is significant variation among authors, genres and epochs in the degree of authenticity in fictional orality. In fact, there may be variation among the characters of a novel, as will be demonstrated in this study.

Rather than just emulating natural language conversation, spoken language in literary texts has several functions of its own. Fictional orality supplements the narrative voice, offering additional information, accounts of subjective experience, or personal memories and opinions. It is, thus, an important element of indirect characterization, and in consequence, the respective figures may employ particular registers, focus on ‘their’ topics, obey or subvert expectations for gendered speech, and/or show recognizable linguistic patterns or repetitive phrases that indicate eccentricities (e.g., Uncle Toby in Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy) or ideological obsessions (e.g., Bounderby in Charles Dickens’ Hard Times).

Differences between fictional orality and authentic speech primarily concern aspects of linguistic organization that are fairly obvious. On the one hand, they are the necessary consequences of the written format, in which, for example, overlap is hard to represent and contextual information is missing or provided through lexical material. Proper names are therefore used more often to allow for a smooth understanding of turn-taking within groups, and to indicate the addressee without intervention of the narrative voice (’Sorry, Veronica; excuse me.’, from Roddy Doyle’s novel The Snapper). Spoken language in fictional texts typically features more complex and normatively ‘correct’ sentences than natural conversation, and especially in older works, the utterances can be of considerable length and occasionally border on monologues.

A new dimension of analysis comes into play when we look at modernist literature. Modernist texts often employ interior monologue or a stream of consciousness (see, for instance, Bickerton 1967; Pascal 1977; Cohn 1978; McHale 1978; Fludernik 1993), so the binary distinction between narration and speech is not applicable, and the perspective has to be extended to include the representation of thought processes. Broadening the perspective in this way also raises some new questions. As in the case of fictional orality, we may ask to what extent the interior speech of the characters varies from one figure to another; we can, moreover, compare the private thoughts of a given character to that character’s public speech. Again, such differences can be analyzed in terms of their literary functions, e.g., as a means of perspective-taking and indirect characterization.

The present study investigates the interior monologue in James Joyce’s novel Ulysses in comparison to the characters’ speech and the narrative voice. Joyce made ample use of this technique and is widely regarded as having perfectionized it. While Joyce did not invent interior monologue—he always pointed at Édourd Dujardin and his novel Les lauriers sont coupés as his source of inspiration—this technique plays a particularly prominent role in Ulysses. Of course, earlier authors have informed their readers about the thoughts and mental lives of their protagonists, but this usually happened in narrative form, or in the form of free indirect thought. In consequence, the linguistic representation of thoughts did not markedly differ from the rest of the narration. Such sentences are grammatically complete and coherent, and while associations do in part lead to rapid shifts in focus, the trains of thought can still be followed with relative ease, e.g., in Jane Austen’s Emma and, later, Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. Joyce, instead, aims at a simulation of the thought processes, and in consequence, the interior monologue differs from narration and from the simulated orality. William James wrote in The Principles of Psychology:

As we take, in fact, a general view of the wonderful stream of our consciousness, what strikes us first is this different pace of its parts. Like a bird s life, it seems to be made of an alternation of flights and perchings. The rhythm of language expresses this, where every thought is expressed in a sentence, and every sentence closed by a period.(James 1890, p. 243)

This alternation of flight and perching is recognizable in Joyce’s stream of consciousness, and it can at times be difficult to follow the mental jumps and the rapid succession of seemingly incoherent associations. But while James still considered thoughts to correspond to linguistic units (like sentences), in Ulysses they are often fragmented and grammatically incomplete; there is an abundance of ellipses, and as will be shown, particular linguistic elements are over- or underrepresented.

A considerable part of the text (71,499 out of 216,680 tokens) consists of the interior speech of the three main characters, Stephen Dedalus (11,826 tokens), Leopold Bloom (34,617 tokens), and Molly Bloom (25,055 tokens).1 We can thus compare their interior speech, and for (Leopold) Bloom and Stephen (Dedalus), we can also compare their interior monologues to their direct speech. This is not possible for Molly (Bloom), as she only speaks a few words directly in Chapter 4 (’Calypso’). (1), (2), and (3) below show the first segments of interior monologue by Stephen, Bloom, and Molly, respectively (the chapter and the line number in the Gabler Edition (Joyce 1986) are given in parentheses, in the format commonly used in Joyce studies, i.e. chapter and lines separated by a period):2

- (1)

- As he and others see me. Who chose this face for me? This dogsbody to rid of vermin. It asks me too. (1.136–137)

- (2)

- Another slice of bread and butter: three, four: right. Right. […] Good. Mouth dry. […] Just how she stalks over my writingtable. Prr. Scratch my head. Prr. […] They call them stupid. They understand what we say better than we understand them. She understands all she wants to. Vindictive too. Cruel. Her nature. Curious mice never squeal. Seem to like it. Wonder what I look like to her. Height of a tower? No, she can jump me. … (4.11–29)

- (3)

- Yes because he never did a thing like that before as ask to get his breakfast in bed with a couple of eggs since the City Arms hotel when he used to be pretending to be laid up with a sick voice doing his highness to make himself interesting for that old faggot Mrs Riordan that he thought he had a great leg of and she never left us a farthing all for masses for herself and her soul greatest miser ever was actually afraid to lay out 4 d for her methylated spirit telling me all her ailments she had too much old chat in her about politics and earthquakes and the end of the world … (18.1–8)

Joyce’s experiments were highly influential, and subsequent authors, e.g., John Dos Passos and William Faulkner, adapted the interior monologue to their specific works and agendas. The linguistic analysis of this mode as distinct from narration and simulated orality is thus an important contribution to the field of literary linguistics, providing a better understanding of the individual literary work and the conceptualization of literary language and techniques in general.

Our analysis focuses on two main questions:

- Does Joyce distinguish between the characters’ interior speech or thought representations, and what (if any) are the linguistic features underlying these distinctions?

- Are there recognizable linguistic differences between the (direct) speech and thought (interior speech) of the figures?

Of course, we are not the first to ask such questions. Stephen, Bloom, and Molly are quite different in their interests, and their minds not only wander through their respective memories but also reflect on very different topics. Stephen and Bloom have been characterized as having a poetic/philosophical mind (Stephen), as opposed to a scientific/musical mind (Bloom). This general distinction can easily be confirmed by a look at the contents of their thoughts (nouns, proper names, etc.), which has been done comprehensively and convincingly (see for instance Steinberg 1973; Houston 1989; Wales 1992).

In this study, we are not primarily interested in what the characters think, but in how they think. In other words, we are dealing with the distribution of linguistic ‘features’ in the sense of multidimensional register studies, as advocated by Biber (1988) and in subsequent work. In this tradition, the register is regarded as a multidimensional concept comprising ‘dimensions’, which are mathematically defined as latent variables underlying the distribution of linguistic features in (parts of) texts, and which are assumed to be symptomatic of specific (situational, functional) varieties. We use the term ‘genre’ for types of text that are defined in terms of the ‘external’ circumstances of production. Genres are obviously hierarchically structured. Higher-level genre categories comprise ‘fiction’ as opposed to ‘non-fiction’, and at a more specific level, we can distinguish, for instance, news reports from academic texts within non-fiction. Texts belonging to a given genre may exhibit internal register heterogeneity. For example, a prose text may contain direct speech. We use the term ‘mode’ for such lower-level varieties defined in terms of the circumstances of production. The traditional ‘rhetorical modes’ or ‘modes of discourse’ concern the type of information conveyed (‘narrative’, ‘report’, ‘descriptive’, ‘information’, ‘argument’; see Smith 2003). We will use the term ‘mode’ to stand in for ‘mode of production’ in this study, subsuming the narrative voice, reported speech, and interior monologue.

The (externally defined) genres and modes have linguistic reflexes. In particular, they are associated with (multinomial) distributions of specific types of linguistic expressions (words, categories), summarized under the term ‘features’ in multidimensional register analysis. Unlike keyword analysis (Culpeper 2009), Biber-style register analysis abstracts away from lexical content, focusing on the structural design features of a variety. Biber (1988) used 67 features, grouped into 16 major classes.3 The choice of features is comprehensively discussed and motivated, with pointers to relevant earlier literature (Biber 1988, Appendix II). While originally developed for non-fictional language, multidimensional register analysis has also been applied to literary texts, e.g., by Egbert (2012) and Egbert and Mahlberg (2020).

While following the general spirit of Biber-style quantitative register analysis, our study is also informed by the qualitative work in the tradition of Koch and Oesterreicher (1986), which addresses very similar issues from a slightly different point of view. Koch and Oesterreicher (1986) have reanalyzed the distinction between spoken and written language by distinguishing between the code (phonic, graphic) and the conception (language of immediacy and language of distance; see Werner 2021 for a recent study that deals with performed language).

Beyond the specific goal of investigating the interior monologues of three characters in one of the most important works of modernism, we intend to show how linguistics and literary studies can benefit from, and cross-fertilize, each other. It is important to note that quantitative register analyses of literary texts can only inform and complement, not replace, the hermeneutic analyses traditionally carried out in literary studies. There are two main types of insights for literary studies from such enterprises, which we may call ‘confirmatory’ and ‘exploratory’. Empirical studies can be confirmatory in the sense that they may provide objective and replicable evidence for literary analyses. They can be exploratory in the sense that they may bring to light new aspects of a work that had previously gone unnoticed, in particular, features that are usually under the radar of recognition. From a linguistic point of view, the benefit of studying interior monologue lies in expanding our knowledge of the manifold ways in which language varies according to the situational or functional context, which is the general objective of register studies as a sub-discipline of linguistics.

2. Materials and Methods

Our research is based on a corpus of literary texts compiled and annotated for the purpose of a project on fictional orality, in which Ulysses (Gabler edition) was included (Joyce 1986). A list of the texts is provided in Appendix A. For the present analysis, the following thirteen chapters of Ulysses are relevant, as they contain either direct speech or interior speech, or both:

- Ch. 1 (’Telemachus’)

- Ch. 2 (’Nestor’)

- Ch. 3 (’Proteus’)

- Ch. 4 (’Calypso’)

- Ch. 5 (’Lotus Eaters’)

- Ch. 6 (’Hades’)

- Ch. 7 (’Aeolus’)

- Ch. 8 (’Laistrigonians’)

- Ch. 9 (’Scylla and Charybdis’)

- Ch. 12 (’Cyclops’)

- Ch. 13 (’Nausicaa’)

- Ch. 16 (’Eumaeus’)

- Ch. 18 (’Penelope’)

We did not include Ch. 15 (’Circe’) in our analysis, even though it is written in dramatic form and thus contains a lot of speech. The hallucinatory language is simply too artificial for our purposes.

The data was manually annotated for speakers by adding XML-style tag pairs to the raw text, as illustrated in (4). The annotations for thoughts were created independently by D. Vanderbeke and T. Mészáros. Cases of disagreement were resolved by discussion.4

- (4)

- <buck>The aunt thinks you killed your mother.</buck><narr>he said.</narr><buck>That is why she will not let me have anything to do with you.</buck><step>Someone killed her,</step><narr>Stephen said gloomily.</narr>

In order to estimate degrees of variability in the structural make-up of character/mode combinations, we identified larger segments of Bloom’s and Stephen’s speech and thoughts—segments that were not interrupted by more than thirty words of another mode—and treated them as sets of sub-samples. Molly’s soliloquy was segmented by treating yes as a separator. These ‘segment samples’, as we call them, allowed us to determine significance levels for comparisons between character/mode combinations and other texts.

Register studies require a reference corpus in order to create a multidimensional space within which the data under analysis can be situated. We used the British National Corpus (BNC)5 for this purpose, a standard corpus with fine-grained genre classifications for texts, thereby distinguishing 46 categories.6

The data were also annotated per token, in two ways. First, the entire corpus, including the BNC, was lemmatized and annotated for parts of speech with the state-of-the-art Python package stanza.7 We used the tagset of the Penn Treebank (PTB) with 36 tags, which are listed in Appendix B.8 The PTB tags represent a standard in much of theoretical and computational linguistics. The PTB annotations are therefore useful for comparison with other datasets.

The PTB tags contain rather general information, subsuming not only major content words but also function words in major classes. For example, personal pronouns are represented by the tag ‘PRP’. For register studies, it is, however, useful to differentiate between different types of pronouns (I, you, she, etc.). The same applies to prepositions and other classes of function words. We therefore created a representation of the texts that abstracts away from content words while keeping individual function words. We call this type of representation a ‘structural skeleton’. By generalizing over content words, we wanted to make sure that we measure register features of the genres and modes under analysis, not topicality as reflected in lexical material (lexical material plays a central role in keyword analysis; see, for instance, Fischer-Starcke 2009; see Culpeper 2009 for a discussion of the potential of keywords, part-of-speech tags and semantic categories). Nouns, proper nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs were replaced by their relevant part-of-speech tags in the structural skeletons. For illustration, consider Table 1. The top row shows the raw text, the second row contains the text annotated with the PTB tags, and the third row shows the structural skeleton that remains if the specific content words (lemmata) are replaced with the appropriate tag. The corpus in this format is made available in the Supplementary Materials (see the Data Availability Statement).

Table 1.

From raw text to a structural skeleton.

The second type of structural annotation was carried out with the ‘Multidimensional Analysis Tagger’ (MAT).9 The MAT replicates the tagger used by Biber (1988), developed specifically for register research. It is based on the Stanford tagger10 and applies replacement rules to obtain results that are largely equivalent to those of the tagger used by Biber (1988). The tagger assigns not only part-of-speech tags to tokens but also categorizes specific elements semantically. For example, it assigns tokens to semantic classes such as ‘private verb’, ‘public verb’, and ‘suasive verb’, and it distinguishes different types of modals (possibility modals, necessity modals, predictive modals).

The MAT moreover determines dimension scores for texts, for the following dimensions of register variation:

- Involved vs. informational discourse.

- Narrative vs. non-narrative concerns.

- Context-independent vs. -dependent discourse.

- Overt expression of persuasion.

- Abstract vs. non-abstract information.

- Online informational elaboration.

Nini (2019) points out that the MAT is not fully equivalent to the original Biber tagger. Validating the MAT on the basis of the LOB-corpus (also used by Biber 1988), he found that despite some differences (specifically in the scores determined for Dimension 3), it is reliable and also generalizes beyond the data used by Biber (1988). Still, it must be kept in mind that there is a certain deviation from the scores assigned by the Biber tagger, and that any subtleties in dimension scores, therefore, must be treated with care.

For our quantitative analyses, we relied on methods that are commonly used in literary register studies. In order to locate a text in multidimensional register space, we used the dimension scores (obtained with factor analysis) of the MAT. For comparisons of genres and modes, we applied the Mann–Whitney U test, as the data were not normally distributed. In order to identify linguistic features that are characteristic of a specific genre, mode, or character/mode combination, we determined adjusted Pearson residuals. Adjusted Pearson residuals are defined as the differences between the observed and the expected frequency, divided by the standard error of the residual (O: observed frequency; E: expected frequency; n: sample size):

- (5)

As is standard, we regard a structural marker as over- or underrepresented (at ) if the standardized residual is higher than 2 or lower than .

3. Results

We start in Section 3.1 by locating the modes of interest (interior monologue, fictional orality, and the narrative voice) in multidimensional register space. These results are based on the tags obtained with the multidimensional tagger, and the data from Ulysses are compared to other literary texts of our sample and the texts from the BNC. In Section 3.2, we zoom in on the (fictional) speech and interior monologues of Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus, and the interior monologue of Molly Bloom. This section is based on the PTB tags assigned by the stanza package.

3.1. Thoughts and Speech in Multidimensional Register Space

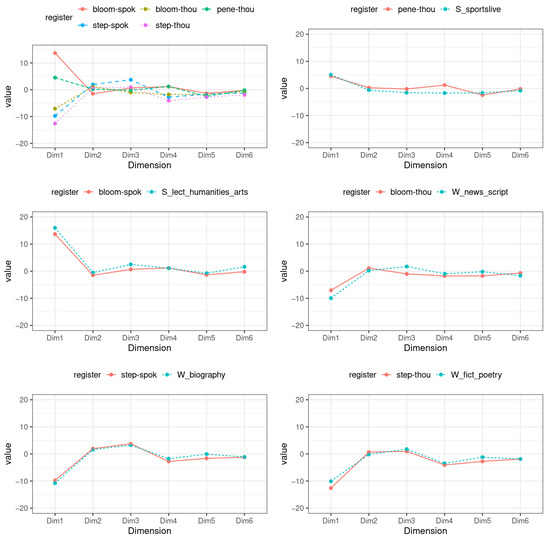

The dimension scores for the five character/mode combinations according to the MAT are shown in Figure 1, in the way Biber-style dimension scores are ‘traditionally’ displayed (see, for instance, Biber 1989, Crosthwaite and Cheung 2019). The plot in the top-left shows all character/mode combinations. The other plots show one character/mode combination together with the genre from the BNC which is most similar in terms of the dimension scores (measuring similarity as Euclidean distance in multidimensional space):11

Figure 1.

Dimension scores according to the MAT, for all genre/mode combinations and individual speakers with the most similar BNC genre (mean value): Molly/thoughts, S_sportslive (top right); Bloom/speech, S_lect_humanities_arts (middle left); Bloom/thoughts, W_news_script (middle/right); Stephen/speech, W_biography (bottom left); Stephen/thoughts, W_fict_poetry (bottom right).

- Bloom/thoughts: news script

- Bloom/speech: lectures on humanities and arts subjects

- Stephen/thoughts: poetry

- Stephen/speech: (auto)biographies

- Molly/thoughts: live sport commentaries and discussions

While some of these associations between characters and genres may appear peculiar choices, they are certainly not unreasonable if we keep in mind that we are comparing grammatical structures, not vocabulary or topics. Bloom’s thoughts and speech feature elements of written-to-be-spoken genres (news scripts and lectures). Stephen’s thoughts resemble poetry, and his speech is similar to the language of biographies. Molly’s thoughts resemble unplanned monological spoken language, as far as structural organization is concerned.

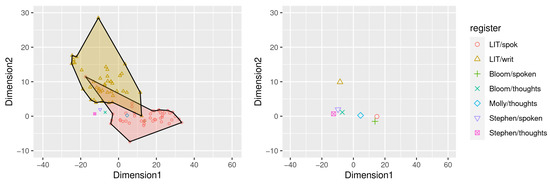

Figure 1 shows that most of the variance between the character/mode combinations is found along Dimension 1 of the multidimensional register space. The lines for the other dimensions are relatively flat. If we compare speech and thought representations to the narrative voice, Dimension 2 is the most distinctive one. The two plots in Figure 2 show the Dimension 1 and 2 scores for the five character/mode combinations, along with fictional speech and the narrative voice from all literary works of our corpus (left: all values, right: mean values; for Ulysses, the chapters were treated separately, given their considerable stylistic variability). The plots give us an idea of the distances between different modes or character/mode combinations. They show that on Dimensions 1 and 2, thought aligns with speech (in literary texts) insofar as the relevant data points cluster around zero.

Figure 2.

Dimension 1 and 2 scores according to the MAT for the narrative voice and fictional orality and the speech and thoughts of Bloom, Stephen, and Molly (left: scores per text, right: mean values).

The upper polygon in the left plot in Figure 2 encloses the written material from the texts of our literary corpus. Unsurprisingly perhaps, this material exhibits relatively high values on Dimension 2, which measures ‘narrative concerns’. The polygon at the bottom encloses the spoken material from the corpus (dialogues). As is to be expected, the spoken material from the novels exhibits higher values for Dimension 1 (measuring ‘involvement’) than the narrative voices, and lower values for Dimension 2. (Note that the left-top spike of the LIT/spoken polygon represents Chapter 4 of Ulysses, where Bloom and Molly are introduced; most other novels or chapters have much lower values for Dimension 2, for fictional orality.)

With respect to the interior monologues of the novel in comparison to the characters’ speech, the following observations stand out when inspecting the plots in Figure 1:

- 1.

- Speech and thought representation in Ulysses are generally non-narrative, as is reflected in their low Dimension-2 values (see also Figure 1).

- 2.

- Both speech and thought representations occupy a large range of values for Dimension 1, showing varying degrees of involvement and informativity.

More specifically, we can make the following observations about the characters under analysis:

- 3.

- Molly’s thoughts and Bloom’s speech are located well within the region of values covered by spoken language in other fictional texts, whereas both Stephen’s speech and thoughts, and Bloom’s thoughts, are located outside of that region.

- 4.

- Stephen’s thoughts and speech are very close to each other, whereas Bloom’s thoughts and speech are quite far apart, mainly distinguished by Dimension 1.

Before discussing these results in Section 4, we now turn to a more fine-grained analysis of the structural patterns observed in the character/mode combinations of interest.

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Speech and Thoughts in Ulysses

In this section, we zoom in on the three characters, comparing their thoughts to each other, and to direct speech where available (Bloom, Stephen). We start with Stephen in Section 3.2.1 because his thoughts constitute an extreme case of informational language, which we can use as a point of reference for Bloom (Section 3.2.2) before we compare both of these characters to Molly (Section 3.2.3).

3.2.1. Stephen’s Thoughts and Speech

The markers that are significantly over-represented (with an adjusted residual of >2) are shown in Table 2. There is very little verbal material even in the right columns (showing speech). Both modes exhibit a heavily nominal style, though Stephen’s speech is slightly more verbal than his thoughts. The main difference between speech and thoughts consists of the type of referential expressions used. In his thoughts, Stephen uses the (deictic) first-person pronouns I and my, and the second-person pronoun you, more than in his speech, where the (anaphoric) third-person singular pronouns he and it are more prominent. Moreover, singular and plural nouns (and pronouns) figure more prominently in his thoughts, as do gerunds and adjectives. The absence of verbal elements from the list of over-represented markers, and the absence of elements creating cohesion, is striking. ‘Verbless’ subjects render Stephen’s reflections often static and tableauesque, which is in keeping with his aesthetic theory developed in ‘Proteus’.

Table 2.

Adjusted Pearson residuals for structural markers in Stephen’s thoughts and speech.

While Stephen’s thoughts seem to be organized around the noun phrase as a main structural unit, his speech exhibits traces of nominal and stative verbal predication, as reflected in the copula be and the auxiliaries may and have. Moreover, there are symptoms of the rhetorical mode of description, e.g., the relative pronouns who(m) and which. Stephen’s speech also features a relatively large number of prepositions and conjunctions, in comparison to his thoughts.

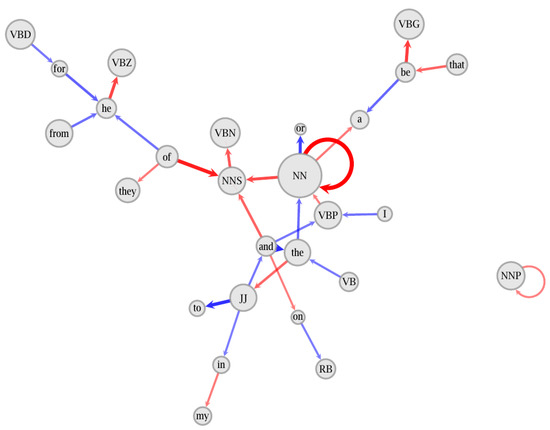

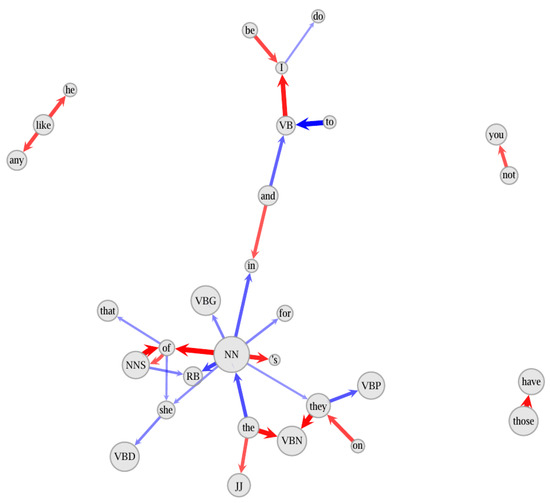

Figure 3 shows a comparative bigram graph for Stephen’s thoughts and speech. The arrows indicate over-representation in either thoughts (red) or speech (blue), in comparison to the other mode. The cluster at the centre illustrates the nominal patterns that are frequent in his thoughts: singular and plural nouns co-occurring with other nouns, in combination with the preposition of and past participles (VBN). The (blue) patterns showing the conditional distribution of elements in speech point to more verbal structures, e.g., and .

Figure 3.

Comparative bigram graph for Stephen’s speech and thoughts. Blue arrows indicate over-representation in speech, red arrows indicate over-representation in thoughts.

The lack of cohesion characteristic of Stephen’s thoughts can be illustrated with examples (6) to (8). There are no conjunctions or anaphoric pronouns. Note also the heavily nominal style.

- (6)

- Her secrets: old featherfans, tasselled dancecards, powdered with musk, a gaud of amber beads in her locked drawer. (1.255–256)

- (7)

- A sail veering about the blank bay waiting for a swollen bundle to bob up, roll over to the sun a puffy face, saltwhite. (1.675–677)

- (8)

- A jester at the court of his master, indulged and disesteemed, winning a clement master’s praise. (2.43–45)

The relatively incoherent nature of Stephen’s thoughts is probably not unrelated to the over-representation of plural nouns. These structural markers are symptoms of a generalizing attitude, making reference to categories rather than instances of those categories, as can be observed in (6) above and in the following examples:

- (9)

- Young shouts of moneyed voices in Clive Kempthorpe’s rooms. (1.165)

- (10)

- Like him was I, these sloping shoulders, this gracelessness. My childhood bends beside me. Too far for me to lay a hand of comfort there once or lightly. Mine is far and his secret as our eyes. Secrets, silent, stony sit in the dark palaces of both our hearts: secrets weary of their tyranny: tyrants, willing to be dethroned. (2.168-172)

The highly impersonal type of reference that characterizes Stephen’s thoughts also drives the over-representation of plural pronouns. They are often used for collective reference, e.g., to cows (in (11)), pupils (in (12)), or implicitly, the police (in (13)).

- (11)

- Crouching by a patient cow at daybreak in the lush field, a witch on her toadstool, her wrinkled fingers quick at the squirting dugs. They lowed about her whom they knew, dewsilky cattle. (1.400–403)

- (12)

- In a moment they will laugh more loudly, aware of my lack of rule and of the fees their papas pay. (2.28–29)

- (13)

- Yes, used to carry punched tickets to prove an alibi if they arrested you for murder somewhere. (3.179–180)

As was seen above, Stephen’s thoughts often center around himself, as is reflected in a relatively frequent occurrence of the pronoun I (cf. the interior dialogue in (14)). The pronoun you is also over-represented, often used to refer to Stephen himself or used impersonally; cf. (15). Note also that some of Stephen’s self-references are associated with past-tense verbs (in memories, cf. (16)).

- (14)

- How now, sirrah, that pound he lent you when you were hungry? Marry, I wanted it. Take thou this noble. Go to! You spent most of it in Georgina Johnson’s bed, clergyman’s daughter. Agenbite of inwit. Do you intend to pay it back? (9.192–197)

- (15)

- If you can put your five fingers through it it is a gate, if not a door. (3.8–9)

- (16)

- Pretending to speak broken English as you dragged your valise, porter threepence, across the slimy pier at Newhaven. (3.194–196)

The most typical features of Stephen’s thoughts—the generalizing reference and the lack of cohesion—are symptoms of a type of reflection that is often a direct response to immediate sensory input. This is compatible with a low frequency of occurrence of the distal demonstrative determiner that, which is significantly underrepresented in Stephen’s thoughts and speech in comparison to Bloom’s thoughts and speech, as will be seen in Section 3.2.2. Examples where Stephen uses the proximal demonstrative this (rather than that), in contexts of perception, are given in (17)–(19) (narrative elements are in brackets).

- (17)

- [Stephen bent forward and peered at the mirror held out to him, cleft by a crooked crack.] Hair on end. As he and others see me. Who chose this face for me? This dogsbody to rid of vermin. (1.135–137)

- (18)

- [Anxiously he glanced in the cone of lamplight where three faces, lighted, shone.] See this. Remember. [Stephen looked down on a wide headless caubeen, hung on his ashplanthandle over his knee.] (9.292–296)

- (19)

- [Hauled stark over the gunwale he breathes upward the stench of his green grave, his leprous nosehole snoring to the sun.] A seachange this, brown eyes saltblue. Seadeath, mildest of all deaths known to man. (3.480–483)

To sum up, Stephen’s thoughts exhibit a heavily nominal style, with large numbers of plural nouns and pronouns. This style is symptomatic of Stephen’s often impersonal, generalizing reference and his abstract thinking. The striking lack of cohesive elements—reflected in the rarity of conjunctions and anaphoric pronouns, among other features—is compatible with the high degree of information density pointed out above. It is also what renders Stephen’s thoughts similar to the language of poetry, where anaphoric pronouns are relatively rare and definite descriptions are relatively frequent. The high information density in Stephen’s monologue could also be part of a narrative strategy that aims at a simulation of rapid thought processes.

Stephen’s thoughts are very similar to his speech, stylistically speaking. In fact, a comparison of the segment samples shows that Stephen’s thought and speech differ in only one of Biber’s (1988) six dimensions, Dimension 1, according to a Mann–Whitney U test (p = 0.037). There is no significant difference in any of the other dimensions. As was shown above, the differences between Stephen’s thoughts and speech in Dimension 1 are mainly due to types of reference. It is probably natural for people to think more about themselves than they speak about themselves (and Joyce was probably aware of this when creating Stephen’s thought representations). From this point of view, even the difference along Dimension 1 may not be primarily a matter of style, but of perspective and topicality—self-reference and egocentric thinking vs. a more outward-directed attitude in speech. This difference is illustrated in (20)–(21) (thoughts) and (23)–(25) (speech).

- (20)

- He fears the lancet of my art as I fear that of his. (1.152)

- (21)

- Silent with awe and pity I went to her bedside. (1.251–252)

- (22)

- So I carried the boat of incense then at Clongowes. I am another now and yet the same. (1.310–311)

- (23)

- All Ireland is washed by the gulfstream, Stephen said as he let honey trickle over a slice of the loaf. (1.476–77)

- (24)

- Cochrane and Halliday are on the same side, sir, Stephen said. (2.190)

- (25)

- But they are afraid the pillar will fall, Stephen went on. They see the roofs and argue about where the different churches are: Rathmines’ blue dome, Adam and Eve’s, saint Laurence O’Toole’s. However, it makes them giddy to look so they pull up their skirts. (7.1010–1013)

3.2.2. Bloom’s Thoughts and Speech

The adjusted Pearson residuals for Bloom’s speech and thoughts are shown in Table 3. There is a straightforward separation into markers associated with nominal style at the top in the left column (prevalent in thoughts) and markers typical of verbal style in the right column, associated with Bloom’s speech.

Table 3.

Adjusted Pearson residuals for Bloom’s thoughts and speech.

Among the most important structural markers that are over-represented in Bloom’s thoughts, in comparison to his speech, we found elements of nominal syntax (nouns, proper names, adjectives, gerunds, etc.), the pronoun she, reflecting Bloom’s thoughts about Molly, past tense verbs reflecting memories, and the demonstrative determiner that. The list of structural markers that are underrepresented in Bloom’s thoughts, and hence, over-represented in his speech, includes first and second-person pronouns (I, me, you), the interjection yes, the modals will and can, the demonstrative pronoun that, and the demonstrative determiner this. Some of these features are elements of conversation; the modals and demonstratives will be discussed below.

A comparative bigram graph for Bloom’s thoughts and speech is shown in Figure 4. Bigrams associated with thoughts (in red) include nominal ones, such as the combination of the definite determiner the and plural nouns (NNS), but there are also verbal patterns, e.g., . The blue edges, signaling over-representation in speech, are more pronounced, including elements pointing to interactive speech (e.g., , and ). This is in accordance with the impression given by Figure 2. Bloom’s interior monologues are distinguished from his speech by low values on Dimension 1, showing low degrees of involvement, and hence, relatively low frequencies of features prominently associated with this dimension, such as first and second-person pronouns.

Figure 4.

Comparative bigram graph for Bloom’s speech and thoughts. Blue arrows indicate over-representation in speech, red arrows indicate over-representation in thoughts.

To date, we have considered Bloom’s thoughts in comparison to his speech. The picture changes considerably if we change our perspective and compare Bloom’s thoughts to Stephen’s thoughts. The adjusted residuals for this comparison are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Adjusted Pearson residuals for Stephen’s and Bloom’s thoughts.

Symptoms of nominal style, such as proper names (NNP), plural nouns (NNS), and the preposition of, are more prevalent in Stephen’s thoughts. In Bloom’s thoughts, base forms of verbs (VB) are over-represented, which corresponds to the relatively high incidence of modal auxiliaries (could, must, might, would).

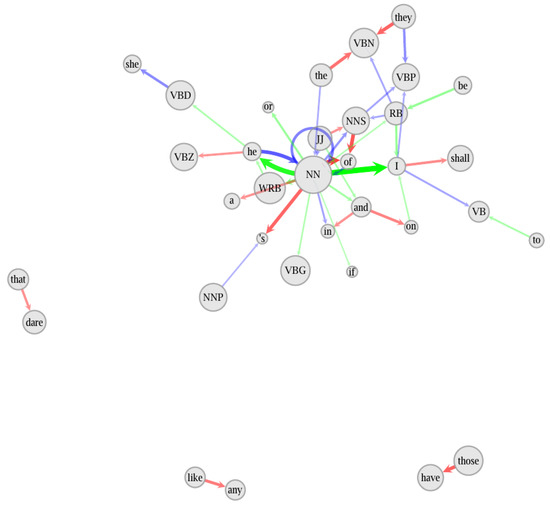

More precise observations can be made by inspecting the comparative bigram graph in Figure 5. Stephen often combines nouns with other nouns, either with a Saxon genitive (’s) or with the preposition of. Sequences of a definite article and a noun are more typical of Bloom’s thoughts, pointing to a higher degree of cohesion. Another observation to keep in mind is the important role of adverbials (RB), which are not only relatively frequent in Bloom’s thoughts (cf. Table 4) but also figure prominently in bigrams following (singular or plural) nouns (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparative bigram graph for Bloom’s and Stephen’s thoughts. Blue arrows indicate over-representation in Bloom’s thoughts, red arrows indicate over-representation in Stephen’s thoughts.

As has been pointed out, there are elements of dialogue in Bloom’s thoughts, despite their mostly nominal organization. Relevant examples are given in (26)–(28) (narrative elements are in brackets).

- (26)

- Why are their tongues so rough? To lap better, all porous holes. Nothing she can eat? [He glanced round him.] No. (4.47–48)

- (27)

- O, well: she knows how to mind herself. But if not? No, nothing has happened. Of course it might. (4.428–429)

- (28)

- By the way, did I tear up that envelope? Yes: under the bridge. (5.385)

Bloom’s inner dialogues and self-corrections testify to a high degree of epistemic uncertainty.12 In Bloom’s thoughts, epistemic uncertainty is once more reflected in the use of modals. The modal must is particularly typical of Bloom’s thoughts and is significantly over-represented in comparison to both Bloom’s speech and Stephen’s thoughts and speech. This is found in both deontic and epistemic contexts. In deontic uses of must, Bloom’s inner voice often has a reminding or self-admonishing function, as illustrated in (29)–(31).

- (29)

- That book I must change for her. (6.154–155)

- (30)

- I must see about that ad after the funeral. (6.742)

- (31)

- Sad about her lame of course but must be on your guard not to feel too much pity. They take advantage. (13.1094–1096)

Examples of epistemic uses of must, where inferences are made, are given in (32)–(34).

- (32)

- Lot of babies she must have helped into the world. (4.418)

- (33)

- That must be why the women go after them. (5.69)

- (34)

- Squareheaded chaps those must be in Rome: they work the whole show. (5.434–435)

While epistemic must, though expressing uncertainty in comparison with an indicative sentence, conveys a relatively high degree of certainty, epistemic could is more tentative. It is significantly over-represented in Bloom’s thoughts in comparison to all other speech or thought combinations. Could is sometimes used by Bloom to make a suggestion to himself, as in the following examples:

- (35)

- Workbasket I could buy for Molly’s birthday. (8.1119)

- (36)

- Hynes might have paid me that three shillings. I could mention Meagher’s just to remind him. (13.1046–1047)

- (37)

- Athlone, Mullingar, I could make a walking tour to see Milly by the canal. (6.444–445)

The comparatively high degree of interactiveness in Bloom’s thoughts—in comparison to Stephen’s thoughts—is also reflected in the use of demonstratives. The demonstrative that, used as a prenominal determiner (e.g., that Father Farley), is significantly over-represented in this mode, in comparison to both Bloom’s speech and Stephen’s thought and speech. As a determiner, that often appears in a ‘recognitional’ use (cf. Diessel 1999; Enfield 2003). In recognitional use, a demonstrative refers to an entity that is presupposed as shared knowledge; i.e., the author of the proposition relies on the (implied) addressee’s ability to identify the intended referent. This can be observed in (38), where the temporal adverbial that time refers to an earlier experience that is accessible to the character (in ‘normal’ conversation it would have to be accessible to the addressee).13 The same familiarity requirement is present for that Norwegian captain in (39) and for that Capel street library book in (40).

- (38)

- Creaky wardrobe. No use disturbing her. She turned over sleepily that time. (4.73–74)

- (39)

- Chap you know just to salute bit of a bore. His back is like that Norwegian captain’s. (4.214–215)

- (40)

- Must get that Capel street library book renewed or they’ll write to Kearney, my guarantor. (4.360–361)

As was mentioned above, Bloom’s thoughts have a large number of adverbials in comparison to Stephen’s thoughts. The relative frequency of adverbials is, to some extent, due to deictic adverbs such as there, here, and now, as in the following examples (again, narrative elements are in brackets):

- (41)

- [On the doorstep he felt in his hip pocket for the latchkey.] Not there. In the trousers I left off. Must get it. (4.72–73)

- (42)

- [He bent down to regard a lean file of spearmint growing by the wall.] Make a summerhouse here. (4.475–476)

- (43)

- I have a few left from Andrews. Molly spitting them out. Knows the taste of them now. (4.203–204)

Some of the observations made above can be related to the dimension scores obtained with the MA Tagger (remember the caveat from Section 2 regarding the not entirely perfect, but reasonable, match between the tags assigned by the MAT and those of the Biber tagger):

- Bloom’s thoughts exhibit little involvement in comparison to Bloom’s speech, but more involvement than Stephen’s thoughts. This is reflected in the fact that they have significantly higher scores for Dimension 1 ().

- They are located at the lower end of narrativity but are more narrative than Stephen’s thoughts, with higher scores for Dimension 2 ().

- They use a more situation-dependent reference than Stephen’s thoughts, as is also reflected in lower scores for Dimension 3 ().

- They display more features of persuasion (have higher values on Dimension 4) than Stephen’s thoughts, or perhaps more appropriately in the context of interior monologue, deliberation ().

- They exhibit more traces of online informational elaboration than Stephen’s thoughts (have higher values on Dimension 6, ).

As this list shows, there are substantial differences between Stephen’s and Bloom’s thoughts. In the next section, we will see that Bloom’s thoughts tend in the direction of Molly’s thoughts, whose interior monologues exhibit even higher Dimension 1 scores.

3.2.3. Molly’s Thoughts

As Table 5 shows, Molly’s thoughts are characterized by a high incidence of the personal pronouns I and he (and markers such as reflexive possessive forms), reflecting her thoughts about herself, Bloom, and her lover Blazes Boylan (and other men). The stream-of-consciousness-like style is reflected in conjunctions and subjunctions, and ‘heavy’ prepositions (disyllabic ones, or monosyllabic ones with at least three sounds); e.g., with, like, into, and about. As Molly thinks about the day past, past-tense verbs figure prominently. The relative over-representation of nominal elements in Stephen’s and Bloom’s thoughts, reflected in the high residuals for the tags NN, NNP, and NNS, corresponds to an under-representation in Molly’s thoughts. Molly essentially avoids nouns and adjectives, and there are hardly any genitives or prepositional phrases headed by of. Other ‘light’ prepositions (with two sounds only) such as to and in are also underrepresented.

Table 5.

Adjusted Pearson residuals for Stephen’s, Bloom’s, and Molly’s thoughts.

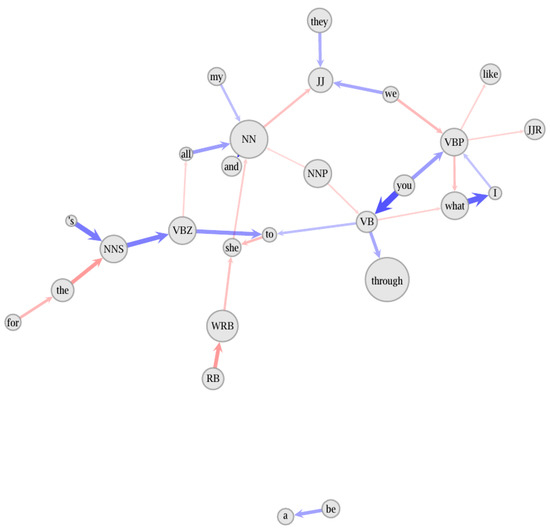

The comparative bigram graph shown in Figure 6 shows an interesting fact: While nouns are significantly under-represented in Molly’s thoughts, as pointed out above, there are two bigrams that are heavily over-represented, and . There are two main reasons for the frequency of these patterns in Molly’s speech. First, due to the absence of punctuation, there are often sequences of an object and the subject of the following sentence or clause, as in (44) (flower he). Second, Molly makes relatively frequent use of ‘bare’ object relative clauses, as in (45) (story he).

Figure 6.

Comparative bigram graph for Bloom’s, Stephen’s, and Molly’s thoughts. Blue arrows indicate over-representation in Bloom’s thoughts, red arrows indicate over-representation in Stephen’s thoughts, green arrows indicate over-representation in Molly’s thoughts.

- (44)

- …I wonder is he awake thinking of me or dreaming am I in it who gave him that flower he said he bought he smelt of some kind of drink …(18.124–126)

- (45)

- …it was down there he was really and the hotel story he made up a pack of lies …(18.36–37)

Molly’s thoughts compare to Stephen’s and Bloom’s thoughts as follows, as far as dimension scores are concerned:

- They differ significantly from Bloom’s and Stephen’s thoughts on Dimensions 1 (high degree of involvement, for both Bloom and Stephen).

- They differ significantly from Stephen’s thoughts on Dimensions 3 and 4 (context-dependent vs. dependent discourse, , and high degree in expression of persuasion, ).

- They differ significantly from Bloom’s and Stephen’s thoughts on Dimension 6 (high value of online informational elaboration, for Bloom, for Stephen).

In sum, Molly’s thoughts are much more similar to fictional orality than either Stephen’s or Bloom’s thoughts, but they are much closer to Bloom’s thoughts in terms of their structural make-up.

4. Discussion

We started by asking two questions in Section 1, repeated here for convenience:

- Does Joyce distinguish between the characters’ interior speech or thought representations, and what (if any) are the linguistic features underlying these distinctions?

- Are there recognizable linguistic differences between the (direct) speech and thoughts (interior speech) of the figures?

The answer to question 1 is very clear: There are marked differences between the three characters. On one end of the scale, there is Stephen, with a heavily nominal style, high information density, a low level of cohesion, a high level of elaboration, and comparatively few signs of online processing constraints. On the other end of the scale, Molly has a primarily verbal style, with lower information density, a higher degree of cohesion (e.g., through anaphoric pronouns and conjunctions), and obvious online production constraints. Bloom is located in between in this respect, though overall much closer to Stephen than to Molly.

An answer to question 2 is more difficult to provide. Joyce does distinguish quite categorically between Leopold Bloom’s speech and thoughts, but the stylistic differences between Stephen’s speech and thoughts are very minor. A significant difference in the dimension scores was only observed in Dimension 1, and it was mainly due to the type of reference (self-reference vs. anaphoric reference). The observation that Stephen’s thoughts center around himself while in his speech he tends to refer to others is probably not even primarily a stylistic difference. By contrast, the speech and thoughts of Bloom differ significantly in five of Biber’s six dimensions. They are less involved, more narrative, and more context-dependent; they feature more elements of deliberation; and they show more traces of online production under time constraints.

The difference in the degrees of similarity between Bloom’s and Stephen’s speech and thought processes could be seen as a means of implicit characterization. In Stephen’s case, speech and thought are rather similar, as the reader in fact learns very early on, when Stephen unabashedly complains about Haines to Buck Mulligan at the beginning of the novel. Bloom’s speech, by contrast, shows a marked contrast between the public face and the private thoughts. Such discrepancies between Bloom’s thoughts and speech become apparent, for instance, when he greets the pub owner Larry O’Rourke:

- (46)

- Do you know what I’m going to tell you? What’s that, Mr O’Rourke? Do you know what? The Russians, they’d only be an eight o’clock breakfast for the Japanese. (thoughts, 4.115–117)

- (47)

- Turning into Dorset street he said freshly in greeting through the doorway: Good day, Mr O’Rourke. […] Lovely weather, sir. (speech, 4.120–125)

We can thus notice a tension in Bloom, a desire to please, but the rather polite and positive external appearance hides a sometimes less comforting and agreeable internal perspective. We also observed a certain type of epistemic uncertainty in his thoughts, reflected in the use of modals and frequent self-corrections, which is often due to the kind of ‘theory formation’ characteristic of Bloom—he states a concept or preliminary hypothesis which is then rejected and replaced by a more accurate one. This is also reflected in the relatively high frequency of no as an interjection, as shown in Table 5.

Our quantitative findings based on thoughts and speech have also confirmed the familiar characteristics often attributed to Bloom and Stephen—Bloom’s careful nature and polite demeanour vs. Stephen’s egocentrism and arrogance, and Bloom’s tendency to generalize and to speculate about various matters vs. Stephen’s focus on himself.

On the basis of the results reported above, we can now ask a more general question: Is ‘interior monologue’ a mode that can be identified as such by using the tools of register analysis?14 As should have become clear, an answer to this question is not easy to provide on the basis of the material from Ulysses, as there are marked differences between the characters. Interior monologue typically exhibits few elements of conversational interaction (though there is some self-talk), and thus tends to be distinguished from speech (though less so in Stephen’s case, who refrains from the use of linguistic politeness markers and phatic communication in his speech, rendering his speech quite thought-like). For the same reason, thought representations tend to be informationally denser than speech: the social dimension of speech is missing. However, as was seen in Molly’s case, interior monologue may still primarily resemble spoken language.

On the basis of the (limited) evidence available to us in James Joyce’s Ulysses, our answer to question 2 is that the form of the thought and interior speech representations is not primarily determined by the design features of any given mode; rather, it is a matter of choice, and it is used for at least two important poetological functions, perspectivization and implicit characterization. Seeing the fictional world through the eyes of a character, without the burden of social communication (as in direct speech), opens up a multitude of perspectives. Peeping into a character’s mind moreover tells us something about that character him/herself, e.g., when we think of Bloom’s inner deliberation and discrepancies between thoughts and speech. Molly is primarily accessed through her own thoughts.

5. Conclusions

The present study is part of an interdisciplinary effort to use the tools of quantitative linguistic analysis (as widely applied in corpus linguistics and register studies) for a better understanding of literary texts. We compared interior monologue with fictional orality in J. Joyce’s novel Ulysses because this mode has not received much attention in quantitative studies, and because in Ulysses, one of the most important literary works of modernism, Joyce makes extensive use of that technique and exhibits a level of sophistication that is remarkable even today. Needless to say, the study of interior monologues from a register point of view should be extended in the future by comparing our results to those obtained on the basis of other texts to further understand this understudied mode.

At the most specific level, our study has shown that interior monologue in Ulysses, while being clearly distinct from the narrative voice, is not linguistically homogeneous. In particular, the thoughts of the characters under analysis (Leopold Bloom, Molly Bloom, and Stephen Dedalus) exhibit varying degrees of involvement, as measured by Dimension 1 of a multidimensional register analysis. One character, Stephen Dedalus, showed a very low level of involvement and a high degree of information density, whereas another character, Molly Bloom, is located at the opposite end of the spectrum, and her thoughts resemble spoken language. The third character, Leopold Bloom, is located in between.

Representing the thoughts or interior monologues of speakers obviously implies quite some creativity on the part of the author. There is no consensus as to whether or not, or to what extent, thoughts can be thought without being verbalized. In any case, the author does not have access to other people’s thoughts. While the speech of characters can be modeled on the example of observed behavior—and it is well-known that Joyce did use real-world models for his characters—no such emulation is possible for the representation of thoughts. Obviously, authors can reproduce their own inner voices. As Stephen is widely regarded as Joyce’s alter ego (also in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man), it is likely that his interior monologues to some extent represent the author’s thoughts. This may, to a lesser extent, also apply to Bloom, who exhibits features of the older James Joyce (Bloom is 38 years old in the novel; Joyce was 36 when the novel started to be published in The Little Review in 1918). For Molly, it is conceivable that Joyce, to some extent, was inspired by letters from his wife Nora, who—like the representation of Molly’s thoughts—did not use punctuation marks.

In Section 1, we made a distinction between ‘confirmatory’ and ‘exploratory’ results of quantitative register studies applied to literary texts. Most of our results have been confirmatory, providing empirical evidence for some fairly well-known aspects of the novel, such as properties of the characters. However, the linguistic analysis also highlighted specific elements of the characters and their representations that were not immediately obvious, specifically in the case of Leopold Bloom. For instance, while the use of the particle yes by Molly Bloom is very prominent in her soliloquy, it is not widely known that her husband Leopold Bloom displays a significant preference for no in his interior monologues, compared to the thoughts of Molly and Stephen (cf. Table 5). In fact, following must and she, no is the third most prominent word in Bloom’s thoughts. Whatever the exact implications of that observation may be, the observation itself is certainly not trivial, specifically as Joyce is known to have been extremely careful and precise in the linguistic construction of his figures, and to have paid attention to minuscule details.

Finally, we wish to point out that the methods that we have used have been rather conventional within a quantitative register framework. We used frequency distributions of structural markers as input to quantitative analyses, as is customary in register studies. The texts were treated as bags of words, or rather, bags of structural markers. This means that we focused on global statistical distributions, rather than a linear sequence of elements. Given that methods taking linear order into account are becoming more and more important in computational linguistics, and as more and more complex language models have been developed, it seems reasonable to explore ways of applying such models to questions of literary interest like the one addressed in this study.

Supplementary Materials

The Supplementary Material with the data and scripts can be downloaded at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7439251.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, V.G.; software, V.G.; validation, V.G., C.W. and D.V.; resources, V.G., D.V.; data curation, V.G., C.W.; writing—original draft preparation, V.G.; writing—review and editing, V.G., D.V.; visualization, V.G.; funding acquisition, V.G., D.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) grant number 380283145.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original texts constituting the literary corpus cannot be published for reasons of copyright. The structural skeletons on which the analysis is based are contained in the TSV-file ‘data/LitCorpSkeleton.tsv’. The MAT dimension scores underlying the analyses are provided in the files ‘data/Dimensions_BNC_for_MAT.csv’, ‘data/Dimensions_MAT_by_speaker.csv’, and ‘data/Dimensions_MAT_chunks_new.csv’. The adjusted Pearson residuals were determined with the script ‘py/get_residuals.py’. The results are contained in the folder ‘results’. The plots in Figure 1 were generated with the script R/plots_and_stats.R, using the R-packages tidyverse (Wickham et al. 2019), stringr (Wickham 2022), ggplot2 (Wickham 2016), ggrepel (Slowikowski 2021), and ggforce (Pedersen 2022). The bigram models shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 were created with the Python scripts in the folder ‘py’, using the graphtool package for Python (https://graph-tool.skewed.de/, accessed on 2 January 2023).

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank our audience at the 26th International James Joyce Symposium and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. List of Texts in the Corpus

- Daniel Defoe, Moll Flanders (1722)

- Henry Fielding, Joseph Andrews (1742)

- Charlotte Lennox, The Female Quixote (1752)

- Oliver Goldsmith, The Vicar of Wakefield (1766)

- Maria Edgeworth, Castle Rackrent (1800)

- Jane Austen, Emma (1816)

- Elizabeth Gaskell, Mary Barton (1848)

- Charles Dickens, Hard Times (1854)

- George Eliot, Silas Marner (1861)

- Thomas Hardy, The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886)

- Martin Ross and Edith Somerville, The Real Charlotte (1894)

- Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890)

- E.M. Forster, Howards End (1910)

- D.H. Lawrence, Sons and Lovers (1913)

- James Joyce, Ulysses (1922)

- Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway (1925)

- Ernest Hemingway, The Sun also Rises (1926)

- Elizabeth Bowen, The Last September (1929)

- Henry Green, Living (1929)

- Ivy Compton-Burnett, Brothers and Sisters (1929)

- Evelyn Waugh, Vile Bodies (1930)

- Allan Sillitoe, Saturday Night & Sunday Morning (1958)

- Edna O’Brien, The Country Girls (1960)

- Jennifer Johnston, How Many Miles to Babylon? (1974)

- Hilary Mantel, Every Day Is Mother’s Day (1985)

- Roddy Doyle, The Commitments (1987), The Snapper (1990), The Van (1991)

- Hanif Kureishi, The Buddha of Suburbia (1990)

- Nick Hornby, High Fidelity (1995)

- Zadie Smith, White Teeth (2000)

Appendix B. The Penn Treebank Tagset

| 1. | CC | Coordinating conjunction |

| 2. | CD | Cardinal number |

| 3. | DT | Determiner |

| 4. | EX | Existential there |

| 5. | FW | Foreign word |

| 6. | IN | Preposition or subordinating conjunction |

| 7. | JJ | Adjective |

| 8. | JJR | Adjective, comparative |

| 9. | JJS | Adjective, superlative |

| 10. | LS | List item marker |

| 11. | MD | Modal |

| 12. | NN | Noun, singular or mass |

| 13. | NNS | Noun, plural |

| 14. | NNP | Proper noun, singular |

| 15. | NNPS | Proper noun, plural |

| 16. | PDT | Predeterminer |

| 17. | POS | Possessive ending |

| 18. | PRP | Personal pronoun |

| 19. | PRP$ | Possessive pronoun |

| 20. | RB | Adverb |

| 21. | RBR | Adverb, comparative |

| 22. | RBS | Adverb, superlative |

| 23. | RP | Particle |

| 24. | SYM | Symbol |

| 25. | TO | to |

| 26. | UH | Interjection |

| 27. | VB | Verb, base form |

| 28. | VBD | Verb, past tense |

| 29. | VBG | Verb, gerund or present participle |

| 30. | VBN | Verb, past participle |

| 31. | VBP | Verb, non-3rd person singular present |

| 32. | VBZ | Verb, 3rd person singular present |

| 33. | WDT | Wh-determiner |

| 34. | WP | Wh-pronoun |

| 35. | WP$ | Possessive wh-pronoun |

| 36. | WRB | Wh-adverb |

(https://www.ling.upenn.edu/courses/Fall_2003/ling001/penn_treebank_pos.html, accessed on 2 January 2023).

Notes

| 1 | These figures are based on the part of the text used for the analysis only; see Section 2. |

| 2 | The novel actually contains an earlier minimal thought of Stephen, the word “Chrysostomos” (1.26). |

| 3 | A. Tense and aspect markers. B. Place and time adverbials. C. Pronouns and pro-verbs. D. Questions. E. Nominal forms. F. Passives. G. Stative Forms. H. Subordination features. I. Prepositional phrases. adjectives and adverbs. J. Lexical specificity. K. Lexical classes. L. Modals. M. Special verb classes. N. Reduced forms and dispreferred structures. O. Coordination. P. Negation. See Biber (1988, pp. 73–75). |

| 4 | Ideally, annotations that are not entirely obvious should be carried out in a maximally objective and replicable way, as a matter of reliability. We decided against a multi-annotator approach because the annotations of thoughts in Ulysses require thorough familiarity with the text. Annotators (e.g., students of literature) can thus not be easily recruited or trained. The annotations are made available in the Supplementary Materials, where readers can inspect them. |

| 5 | https://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk, accessed on 2 January 2023. |

| 6 | https://gawron.sdsu.edu/functions_of_language/course_core/lectures/genres.html, accessed on 2 January 2023. |

| 7 | https://stanfordnlp.github.io/stanza/, accessed on 2 January 2023. |

| 8 | https://www.ling.upenn.edu/courses/Fall_2003/ling001/penn_treebank_pos.html, accessed on 2 January 2023. |

| 9 | See Nini (2019) and https://sites.google.com/site/multi-dimensionaltagger, accessed on 2 January 2023. In order to maintain a certain degree of comparability with earlier work on register studies, we used Biber’s original model (as annotated by the MAT), rather than, for instance, the model of Egbert (2012), or the ‘enhanced’ model of Xiao (2009). |

| 10 | https://nlp.stanford.edu/software/tagger.shtml, accessed on 2 January 2023. |

| 11 | The MAT also assigns to each text the closest text type, based on the corpus material used for Biber’s (1988) original study (the LOB corpus). The genres of the LOB-corpus are more coarse-grained than those of the BNC, however. For Bloom’s thoughts the tagger identifies ‘general narrative exposition’ as the closest text type, ‘involved persuasion’ for Bloom’s speech. ‘General narrative exposition’ is also the text type that is closest to Stephen’s thoughts and speech. Molly’s thoughts are grouped with ‘involved persuasion’. |

| 12 | It may be noted that the dialogical form then governs Chapter 17 (’Ithaca’). Focusing on Bloom in his own home, it is presented as a catechism, consisting completely of questions and answers. In contrast to the pseudo-scientific language of this chapter, the result is also epistemic uncertainty, and the most important nuggets of useful knowledge are frequently buried in a form of literary logorrhea garbed as precise factual information. |

| 13 | The example is ambiguous because, in addition to recognitional use, it might also represent an example of what Halliday and Hasan (1976, p. 66) term ‘extended reference’, with that time referring back to an event rather than a single lexical item. That time, thus, could either refer to the present situation (Bloom just having witnessed Molly turning over in her bed) or to a specific past event remembered by Bloom. |

| 14 | Note that in Egbert (2012), ‘Thought Presentation versus Description’ constitutes a dimension of register variation, but it does not refer to interior monologue as a mode. The dimension captures ‘thought-external’ elements such as verbs introducing them, e.g., know, think etc. |

References

- Akinnaso, F. Niyi. 1982. On the differences between spoken and written language. Language and Speech 25: 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, Douglas. 1988. Variation across Speech and Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber, Douglas. 1989. A typology of english texts. Language 27: 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bickerton, Derek. 1967. Modes of interior monologue: A formal definition. Modern Language Quarterly 28: 229–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, Ryan. 1991. There is nothing natural about natural conversation: A look at dialogue in fiction and drama. Oral Tradition 6: 58–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bublitz, Wolfgang. 2017. Oral features in fiction. In Pragmatics of Fiction (Handbooks of Pragmatics 12). Edited by Miriam A. Locher and Andreas H. Jucker. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 235–64. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, Deirdre. 1980. Dialogue and Discourse: A Sociolinguistic Approach to Modern Drama Dialogue and Naturally Occurring Conversation. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, Dorrit. 1978. Transparent Minds: Narrative Modes for Presenting Consciousness in Fiction. Princeton: Princeton University Pree. [Google Scholar]

- Crosthwaite, Peter, and Lisa Cheung. 2019. Learning the Language of Dentistry. Disciplinary Corpora in the Teaching of English for Specific Academic Purposes. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Culpeper, Jonathan. 2009. Keyness: Words, parts-of-speech and semantic categories in the character-talk of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 14: 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVito, Joseph A. 1963. A linguistic analysis of spoken and written language. Central States Speech Journal 18: 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diessel, Holger. 1999. Demonstratives: Form, Function, and Grammaticalization. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Egbert, Jesse. 2012. Style in nineteenth century fiction: A multi-dimensional analysis. Scientific Study of Literature 2: 167–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbert, Jesse, and Michaela Mahlberg. 2020. Fiction-one register or two?: Speech and narration in novels. Register Studies 2: 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enfield, Nicholas J. 2003. The definition of what-d’-you-call-it: Semantics and pragmatics of recognitional deixis. Journal of Pragmatics 35: 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erzgraeber, Willi. 1998. James Joyce: Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit im Spiegel Experimenteller Erzählkunst. Tübingen: Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Erzgraeber, Willi, and Paul Goetsch, eds. 1987. Mündliches Erzählen im Alltag, Fingiertes Mündliches Erzählen in der Literatur. Tübingen: Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Starcke, Bettina. 2009. Keywords and frequent phrases of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice: A corpus-stylistic analysis. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 14: 492–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fludernik, Monika. 1986. The dialogic imagination of Joyce: Form and function of dialogue in Ulysses. Style 12: 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fludernik, Monika. 1993. The Fictions of Language and the Languages of Fiction: The Linguistic Representation of Speech and Consciousness. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fludernik, Monika. 2005. Speech representation. In Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory. Edited by David Herman, Manfred Jahn and Marie-Laure Ryan. London: Routledge, pp. 558–63. [Google Scholar]

- Goetsch, Paul. 1985. Fingierte Mündlichkeit in der Erzählkunst entwickelter Schriftkulturen. Poetica 17: 202–18. [Google Scholar]

- Goetsch, Paul. 1987. Dialekte und Fremdsprachen in der Literatur. Tübingen: Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, Michael Alexander Kirkwood, and Ruqaiya Hasan. 1976. Cohesion in English. Harlow: Longman Group Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, John Porter. 1989. Joyce and Prose: An Exploration of the Language of Ulysses. Lewisburg: Bucknell UP. [Google Scholar]

- James, William. 1890. The Principles of Psychology. New York: Dover Publications, vols. 1 and 2. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, James. 1986. Ulysses. The Gabler edition. Edited by Hans Walter Gabler, Wolfhard Steppe and Claus Melchior. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jucker, Andreas. 2021. Features of orality in the language of fiction: A corpus-based investigation. Language and Literature 30: 341–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, Peter, and Wulf Oesterreicher. 1986. Sprache der Nähe – Sprache der Distanz: Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit im Spannungsfeld von Sprachtheorie und Sprachgeschichte. In Romanistisches Jahrbuch. Edited by Olaf Deutschmann, Hans Flasche, Bernhard König, Margot Kruse, Walter Pabst and Wolf-Dieter Stempel. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 15–43. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, Geoffrey N., and Michael H. Short. 1991. Style in Fiction: A Linguistic Introduction to English Fictional Prose. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Mace, Renate. 1987. Funktionen des Dialekts im Regionalen Roman von Gaskell bis Lawrence. Tübingen: Narr. [Google Scholar]

- McHale, Brian. 1978. Free indirect discourse: A survey of recent accounts. PTL: A Journal for Descriptive Poetics and Theory of Literature 3: 249–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nini, Andrea. 2019. The Multidimensional Analysis Tagger. In Research Methods and Current Issues. Edited by Tony Berber Sardinha and Marcia Veirano Pinto. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academy, pp. 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Pascal, Roy. 1977. The Dual Voice: Free Indirect Speech and Its Functioning in the Nineteenth-Century European Novel. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, Thomas Lin. 2022. ggforce: Accelerating ‘ggplot2’. R package version 0.3.4. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggforce (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Slowikowski, Kamil. 2021. ggrepel: Automatically Position Non-Overlapping Text Labels with ‘ggplot2’. R package version 0.9.1. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggrepel (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Smith, Carlota S. 2003. Modes of Discourse. The Local Structure of Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, Erwin R. 1973. The Stream of Consciousness and Beyond in Ulysses. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Bronwen. 2012. Fictional Dialogue: Speech and Conversation in the Modern and Postmodern Novel. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wales, Latie. 1992. The Language of James Joyce. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, Valentin. 2021. Text-linguistic analysis of performed language: Revisiting and re-modeling Koch and Oesterreicher. Linguistics 59: 541–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, Hadley. 2016. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, Hadley. 2022. stringr: Simple, Consistent Wrappers for Common String Operations. R package version 1.4.1. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=stringr (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Wickham, Hadley, Mara Averick, Jennifer Bryan, Winston Chang, Lucy D’Agostino McGowan, Romain François, Garrett Grolemund, Alex Hayes, Lionel Henry, Jim Hester, and et al. 2019. Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software 4: 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Richard. 2009. Multidimensional analysis and the study of world Englishes. World Englishes 28: 412–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).