Abstract

An Identity-based encryption (IBE) simplifies key management by taking users’ identities as public keys. However, how to dynamically revoke users in an IBE scheme is not a trivial problem. To solve this problem, IBE scheme with revocation (namely revocable IBE scheme) has been proposed. Apart from those lattice-based IBE, most of the existing schemes are based on decisional assumptions over pairing-groups. In this paper, we propose a revocable IBE scheme based on a weaker assumption, namely Computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) assumption over non-pairing groups. Our revocable IBE scheme is inspired by the IBE scheme proposed by Döttling and Garg in Crypto2017. Like Döttling and Garg’s IBE scheme, the key authority maintains a complete binary tree where every user is assigned to a leaf node. To adapt such an IBE scheme to a revocable IBE, we update the nodes along the paths of the revoked users in each time slot. Upon this updating, all revoked users are forced to be equipped with new encryption keys but without decryption keys, thus they are unable to perform decryption any more. We prove that our revocable IBE is adaptive IND-ID-CPA secure in the standard model. Our scheme serves as the first revocable IBE scheme from the CDH assumption. Moreover, we extend our scheme to support Decryption Key Exposure Resistance (DKER) and also propose a server-aided revocable IBE to decrease the decryption workload of the receiver. In our schemes, the size of updating key in each time slot is only related to the number of newly revoked users in the past time slot.

1. Introduction

The concept of Identity-Based Encryption (IBE) was proposed by Shamir [1] in 1984. In an IBE scheme, the public key of a user can simply be the identity of the user, like name, email address, etc. An IBE scheme considers three parties: key authority, sender and receiver. The key authority is in charge of generating secret key for user . A sender simply encrypts plaintexts under the receiver’s identity and the receiver uses his own secret key for decryption. With IBE, there is no need for senders to ask for authenticated public keys from Public-Key Infrastructures, hence key management is greatly simplified.

Over the years, there have been many IBE schemes proposed from various assumptions in the standard model. Most of the assumptions are decisional ones, like the bilinear Diffie-Hellman assumption [2,3,4] over pairing-groups, or the decisional learning-with-errors (LWE) assumption from lattices [5,6,7]. Most recently, a breakthrough work was done by Döttling and Garg [8], who proposed the first IBE scheme based solely on the Computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) assumption over groups free of pairings.

Though IBE enjoys the advantage of easy key management, how to revoke users in an IBE system is a non-trivial problem. It was Boneh and Franklin [9] who first proposed revocable IBE (RIBE) to solve the problem. Later, Boldyreva et al. [10] formalized the definition of selective-ID security and constructed a more efficient RIBE scheme based on a fuzzy IBE scheme [11]. Then Libert and Vergnaud proposed the first adaptive-ID secure revocable IBE scheme [12]. In [13], Seo and Emura strengthened the security model by introducing an additional important security notion, called Decryption Key Exposure Resistance (DKER). They also constructed a revocable IBE scheme in the strengthened model, and the security of this scheme is from the Decisional Bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH) assumption. Since then, most of the revocable IBE schemes constructed from pairing groups achieved DKER. For example, in the strengthened security model, Lee et al. [14] constructed a revocable IBE scheme via subset difference methods to reduce the size of key updating based on the DBDH assumption, and Watanabe et al. [15] introduced a new revocable IBE with short public parameters based on both the Decisional Diffie-Hellman (DDH) assumption and the Augmented Decisional Diffie-Hellman (ADDH) assumption over pairing-friendly group. Furthermore, Park et al. [16] constructed a revocable IBE whose key update cost is only , but the scheme relied on multilinear maps. Without pairing, it seems difficult to achieve DKER. In [17], Chen et al. proposed the first selective-ID secure revocable IBE scheme from the LWE assumption over lattices in the traditional security model (without DKER). Later, Takayasu and Watanabe [18] designed a lattice-based revocable IBE with bounded DKER. Meanwhile, to improve the decryption efficiency for the receiver, Qin et al. [19] provided a new model named Server-Aided Revocable Identity-Based Encryption (SR-IBE) which used a server as an intermediary to help the receiver to decrypt part of the ciphertext. In fact, the revocable property is so important that it is studied not only in IBE but also in Identity-Based Proxy Re-encryption [20], Fine-Grained Encryption of Cloud Data [21,22] and Attribute-Based Encryption [23]. It should be noted that bilinear pairings are essential techniques in these schemes [20,21,22,23].

Please Please note that all the existing RIBE schemes are based on assumptions over pairing-friendly groups or the LWE assumption over lattices. On the other hand, Döttling and Garg’s IBE scheme [8] is based on the CDH assumption over non-pairing group, but it does not consider user revocation. In this paper, we aim to fill the gap by designing RIBE from the CDH assumption without use of pairings.

1.1. Our Contributions

In this paper, we propose the first revocable IBE (RIBE) schemes and server-aided revocable IBE (SR-IBE) based on the Computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) assumption over groups free of pairings. The corner stone of this scheme is the IBE scheme proposed by Döttling and Garg [8]. Our RIBE schemes enjoy the following features.

- Weaker security assumption. The securities of our RIBE and SR-IBE schemes can be reduced to the CDH assumption. Hence our schemes serve as the first RIBE/SR-IBE schemes from the CDH assumption over non-pairing groups. More precisely, our first RIBE scheme can achieve adaptive-IND-ID-CPA security but without the property of decryption key exposure resistance(DKER). Our second RIBE scheme obtains decryption key exposure resistance but with selective-IND-ID-CPA security. Our SR-IBE scheme is selective-SR-ID-CPA secure. The securities of the three schemes can be reduced to the CDH assumption.

- Smaller size of key updating. When a time slot begins, the key updating algorithm of our RIBE/SR-IBE will issue updating keys whose size is only linear to the number of newly revoked users in the past time slot. In comparison, most of the existing RIBE/SR-IBE schemes have to update keys whose number is related to the number of all revoked users across all the previous time slots.

In Table 1, we compare our RIBE scheme with some existing RIBE schemes.

Table 1.

Comparison with RIBE schemes (in the standard model). Here N is the total number of users, r is the number of all revoked users and is the number of newly revoked users the past time slot. DKER means decryption key exposure resistance.

Remark 1.

Döttling and Garg’s IBE makes use of garbled circuits to implement the underlying cryptographic primitives. Hence it is prohibitive in terms of efficiency. Our RIBE inherits their idea, hence the efficiency of our RIBE scheme is also incomparable to the RIBE schemes from bilinear maps. However, since no RIBE scheme is available from the CDH assumption over non-pairing groups, our scheme serves as a theoretical exploration in the field of RIBE.

1.2. Paper Organization

In Section 2, we collect notations and some basic definitions used in the paper and present the framework. We illustrate our idea of RIBE in Section 3. In Section 4, we construct a revocable IBE scheme (without DKER) based on the CDH assumption and present the correctness and security analysis of the scheme. Then we show how to make our RIBE to obtain DKER in Section 5. In Section 6, we provide a SR-IBE scheme from the CDH assumption. In Section 7, we illustrate the key updating complexity analysis of our scheme.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Notations

The security parameter is denoted by . “probabilistic polynomial-time” is abbreviated by “PPT”. Let and b be integers. Denote by the set , by the set , by the set of bit-strings of arbitrary length, and by the set of bit-strings of length at most ℓ. Let be an empty string. and be the bit-length of string v. Obviously, . Denote by the concatenation of two bit-strings x and y, by the i-th bit of x, by the process of sampling the element x from the set uniformly at random, and by the process of sampling the element a over the distribution . By we mean that a is the output of a function f. A function is negligible if for any polynomial it holds that for all sufficiently large .

2.2. Pseudorandom Functions

Let PRF: be an efficiently computable function. For an adversary , define its advantage function as

where is a truly random function. PRF is a pseudorandom function (PRF) if the above advantage function Adv is negligible for any PPT .

2.3. Revocable Identity-Based Encryption

A revocable IBE (RIBE) consists of seven PPT algorithms . Let denote the message space, the identity space and the space of time slots.

- Setup: The setup algorithm is run by the key authority. The input of the algorithm is a security parameter and n, where the maximal number of users is . The output of this algorithm consists of a pair of key , an initial state st = (KL, PL, RL, KU), where KL is the key list, PL is the list of public information, RL is the list of revoked users and KU is the update key list. In formula,

- Private Key Generation: This algorithm is run by the key authority which takes as input the key pair , an identity and the state st. The output of this algorithm is a private key and an updated state . In formula, .

- Key Update Generation: This algorithm is run by the authority. Given the key pair , an update time , and a state st, this algorithm updates the update key list and the the list of public information . In formula, .

- Decryption key generation: This algorithm is run by the receiver. Given the master public key , a private key , the update key list and the time slot , this algorithm outputs a decryption key for time slot . In formula,

- Encryption: This algorithm is run by the sender. Given the public key , a public list PL, an identity id, a time slot and a message m, this algorithm outputs a ciphertext . In formula, .

- Decryption: This algorithm is run by the receiver. The algorithm takes as input the master public key , the decryption key and the ciphertext , and outputs a message m or a failure symbol ⊥. In formula, .

- Revocation: This algorithm is run by the key authority. Given a revoked identity and the time slot during which is revoked and a state , this algorithm updates the revocation list with . It outputs a new state .

Correctness.

For all all , all identity , all time slot , and revocation list , for all , , and we have if (i.e., is not revoked at time t) and .

Now we explain how a revocable IBE system works. To setup the system, the key authority invokes to generate master public key , master secret key and the state . Then it publishes the public key . When a user registers in the system with identity , the key authority invokes to generate the private key for user . If a user needs to be revoked during time slot , the key authority invokes . Next it updates the state . At the beginning of each time slot , the key authority might invoke to update keys by updating set . Then it publishes some information about the updated set . Meanwhile it may also publish some public information . During time slot , when a user wants to send a message m to another user , he/she invokes to encrypt m to obtain the ciphertext , then sends to user . To decrypt a ciphertext encrypted at time , the receiver first invokes to generate its own decryption key of time t. The receiver invokes to decrypt the ciphertext and recover the plaintext.

Remark.

In the definition of our RIBE, KL is the key list which stores the essential information used to generate the update key. PL is a public information list which is used in the encryption algorithm. In the traditional definition of RIBE in other works, no PL is defined. However, in our construction, PL will serve as an essential input to the encryption algorithm and that is the reason we define it. Nevertheless, our definition can be regarded as a general one, while the traditional definition of RIBE can be seen as a special case of .

Security.

Now we formalize the security of a revocable IBE. We first consider four oracles: private key generation oracle , key update oracle , decryption key generation oracle and revocation oracle which are shown in Table 2. The security of adaptive-IND-ID-CPA defines as follows.

Table 2.

Three oracles that the adversary can query.

Definition 1.

Let be a revocable IBE scheme. Below describes an experiment played between a challenger and a PPT adversary .

The experiment has the following requirements for .

- The two plaintexts submitted by have the same length, i.e., .

- The time slot submitted to and by is in ascending order.

- If the challenger has published at time , then it is not allowed to query oracle with .

- If has queried to oracle , then there must be query to oracle satisfies , i.e., must has been revoked before time .

- If is not revoked at time , cannot be queried on .

A revocable IBE scheme is adaptive-IND-ID-CPA secure (with DKER) if for all PPT adversary , the following advantage is negligible in the security parameter λ, i.e.,

Remark 2.

The security definition without DKER is similarly defined with changing the experiment so that an adversary is not allowed to make any decryption key reveal query, i.e., cannot query for the oracle .Next we define selective-IND-ID-CPA security for RIBE, where the adversary has to determine the target identity , target time slot at the beginning of the experiment. Clearly, selective-IND-ID-CPA security is weaker than adaptive-IND-ID-CPA security.

Definition 2.

Let be a revocable IBE scheme. Below describes an experiment played between a challenger and a PPT adversary .

| . |

The requirements for in this experiment are the same as the requirements in . A revocable IBE scheme is selective-IND-ID-CPA secure (with DKER) if for all PPT adversary , the following advantage is negligible in the security parameter λ, i.e.,

Selective-IND-ID-CPA security without DKER is defined can be similarly defined by changing the experiment so that an adversary is not allowed to query for the oracle .

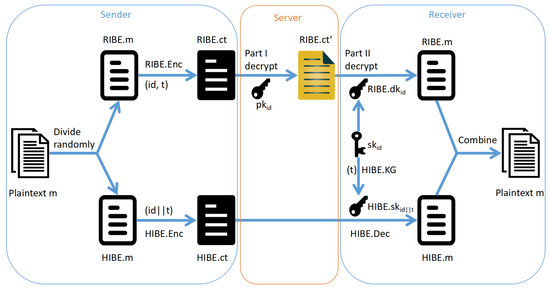

2.4. Server-Aided Revocable Identity-Based Encryption

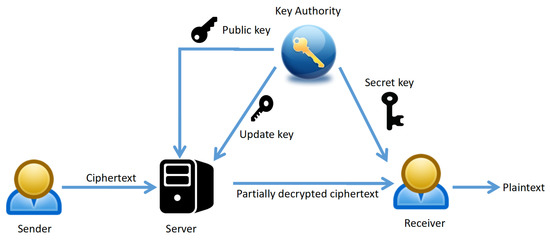

In a server-aided revocable identity-based encryption scheme [19], there are four parities and they work as follows (as shown in Figure 1):

Figure 1.

System model of a server-aided revocable IBE.

- Key Authority generates a public key and a secret key for every registered user and issues the secret key to the user and the public key to the server. In each time slot, the key authority delivers a update key list (to revoke users) to the server.

- Sender encrypts a message for an identity and a time slot and sends the ciphertext to the server.

- Sever combines the update key list and the stored users’ public keys to generate the transformation keys in every time slot for all users. When receiving a ciphertext, the server transforms it to a partially decrypted ciphertext using the transformation key corresponding to the receiver’s identity and the corresponding time slot. Then it sends the partially decrypted ciphertext to the receiver.

- Receiver recovers the sender’s message from the partially decrypted ciphertext using a decryption key which can be generated by his/her own secret key and the corresponding time slot.

Now, we formally define Server-Aided Revocable Identity Based Encryption (SR-IBE) which was first proposed by Qin et al. [19]. A SR-IBE scheme consists of ten PPT algorithms . Let denote the message space, the identity space and the space of time slots.

- Setup: The setup algorithm is run by the key authority. The input of the algorithm is a security parameter and a parameter n, which indicates that the maximal number of users is . The output of this algorithm consists of a pair of key and an initial state , where is the key list, is the list of public information, is the list of revoked users and is the update key list. In formula,

- Public Key Generation: The public key generation algorithm is run by the key authority. It takes as input a master secret key , an identity and a state . The output of this algorithm is the public key on identity . In formula, .

- Key Update Generation: The key update generation algorithm is run by the key authority. It takes as input a master secret key , an update time and a state . The output of this algorithm is an update key list and an updated state . In formula, .

- Transformation Key Generation: The transformation key generation algorithm is run by the server. It takes as input the master public key , the public key and an update key list . The output of this algorithm is the transformation key . In formula, .

- Private Key Generation: The private key generation algorithm is run by the key authority. It takes the master secret key and an identity as input. The output of this algorithm is the private key on identity . In formula, .

- Decryption Key Generation: The decryption key generation algorithm is run by the receiver. It takes the secret key and a slot as input. The output of this algorithm is the decryption key . In formula, .

- Encryption: The encryption algorithm is run by the sender. It takes the master public key , an identity , a time plot , a plaintext message and a public list as the input. The output of this algorithm is the ciphertext . In formula, .

- Transformation: The transformation algorithm is run by the server. It takes the master public key , the transformation key and the ciphertext as the input. The output of this algorithm is the partially decrypted ciphertext . In formula, .

- Decryption: The decryption algorithm is run by the receiver. The input of this algorithm consists of the master public key , the decryption key and the partially decrypted ciphertext . The output of this algorithm is the plaintext . In formula, .

- Revocation: The revocation algorithm is run by the key authority. The input of this algorithm consists of an identity , a time plot and a state . The output of this algorithm is the updated state . In formula, .

Correctness.

The correctness requires that for all message , if the receiver is not revoked at time period and all parties follow the algorithms above, then we have .

Security.

Now we formalize the security of SR-IBE. We first consider five oracles: public key generation oracle , key update oracle , private key generation oracle , decryption key generation oracle and revocation oracle which are shown in Table 3. The selective-SR-ID-CPA security is defined as follows.

Table 3.

Five oracles that the adversary of a SR-IBE scheme can query.

Definition 3.

Let be a server-aided revocable IBE scheme. Below describes an experiment played between a challenger and a PPT adversary .

| . |

The experiment has the following requirements for .

- The two plaintexts submitted by have the same length, i.e., .

- The time slot submitted to and by is in ascending order.

- If the challenger has published at time , then it is not allowed to query oracle with .

- If has queried to oracle , then there must exist a query to oracle satisfying , i.e., must has been revoked before time .

- If is not revoked at time , cannot be queried on .

A server-aided revocable IBE scheme is selective-SR-ID-CPA secure (with DKER) if for all PPT adversary , the following advantage is negligible in the security parameter λ, i.e.,

2.5. Garbled Circuits

A garbled circuits scheme consists of two PPT algorithms .

- : The algorithm takes a security parameter and a circuit as input. This algorithm outputs a garbled circuit and labels where each . Here represents the set [ℓ] where ℓ is the bit-length of the input of the circuit .

- : The algorithm takes as input a garbled circuit and a set of label , and it outputs y.

Correctness.

In a garbled circuit scheme, for any circuit and an input , it holds that

where .

Security.

In a garbled circuit scheme, the security means that there is a PPT simulator such that for any and for any PPT adversary , the following advantage of is negligible in the security parameter :

where .

2.6. Computational Diffie-Hellman Assumption

Let be a group generation algorithm which outputs a cyclic group of order p and a generator of .

Definition 4.

[CDH Assumption]The computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) assumption holds w.r.t. GGen, if for any PPT algorithm its advantage ϵ in solving computational Diffie-Hellman (CDH) assumption in is negligible. In formula, .

2.7. Chameleon Encryption

A chameleon encryption scheme has five PPT algorithms .

- HGen: The algorithm takes the security parameter and a message-length n as input. This algorithm outputs a key k and a trapdoor t.

- H: The algorithm takes the key k, a message and a randomness r as input. This algorithm outputs a hash value h and the length of h is .

- : The algorithm takes a trapdoor t, a previously used message , random coins r and a message as input. It outputs .

- HEnc: The algorithm takes a key k, a hash value h, an index , a bit , and a message as input. It outputs a ciphertext .

- HDec: The algorithm takes a key k, a message , a randomness r and a ciphertext as input. It outputs a value m or ⊥.

The chameleon encryption scheme enjoys the following properties:

- Uniformity. For all ,if both r and are chosen uniformly at random, the two distribution and are statistically indistinguishable.

- Trapdoor Collisions. For any and r, if and , then it holds that Moreover, if r is chosen uniformly and randomly, is statistically close to uniform.

- Correctness. For all , randomness r, index and message m, if , and , then

- Security. For a PPT adversary against a chameleon encryption, consider the following experiment:The security of a chameleon encryption defines as follows: For any PPT adversary , the advantage of in experiment satisfies

In [8], such a chameleon encryption was constructed from the CDH assumption.

3. Idea of Our Revocable IBE Scheme

3.1. Idea of the DG Scheme

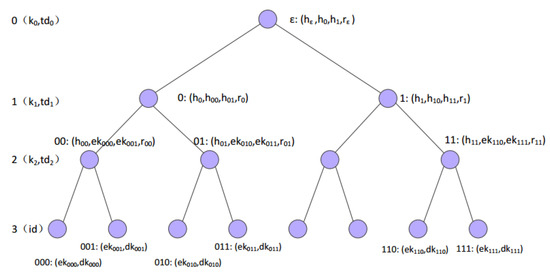

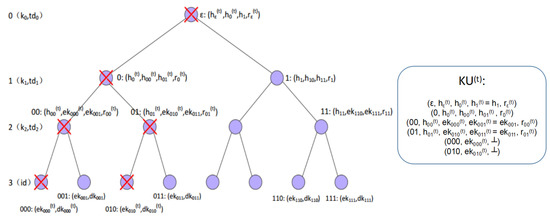

In the IBE scheme [8] proposed by Döttling and Garg, say the DG scheme, each is an n-bit binary string. In other words, each user can be regarded as a leaf of a complete binary tree of depth n, which is the length of a user’s identity id. For each level in the tree, the key authority generates a pair of chameleon encryption key and trapdoor . As shown in Figure 2, a leaf v is attached with a key pair , which is the public/secret key of an IND-CPA secure public-key encryption scheme PKE=(G, E, D), i.e., . In addition, a non-leaf node v in the tree is attached with four values: the hash value of this node, the hash value of the left child node, the hash value of the right child node, a randomness r such that epecially for , . The master public key of IBE is given by the hash keys and the hash value of the root. The master secret key is the seed of a pseudorandom function to generate and the trapdoors of the chameleon encryption.

Figure 2.

The IBE tree of depth .

Key Generation.

Each user is assigned to a leaf in the tree according to . The secret key is just all the values attached to those nodes on the path from the root to the leaf. For example, in Figure 2, if , then the secret key is .

Encryption.

As for encryption, two kinds of circuits are defined.

- (1)

- is a circuit with m hardwired and its input is . It computes and outputs the ciphertext of message m under the public-key .

- (2)

- is a circuit which hardwires bit , key k and a serial of labels . It computes and outputs , where is the short for .

To encrypt a message m under , the sender generates a series of garbled circuits from the bottom to the top. Specifically, for level n, it generates , the garbled circuit of , and the corresponding label , i.e.,

Then, , and are hardwired into circuit . Next, invoke the garbled circuit

Let Invoke . Repeat this procedure and we have . Recall that . Choose labels from according to the bits of .

The final ciphertext is .

Decryption.

The decryption goes from the top to bottom. It will invoke the evaluation algorithm of the garbled circuits to obtain chameleon encryption of labels, and uses the secret key of chameleon encryption scheme to recover the corresponding label. For the leaf, it will use the decryption algorithm of PKE to recover the message m.

3.2. Idea of Our Revoked IBE Scheme

Our revocable IBE is based on the original DG scheme. An important observation of the DG scheme is that among all the elements in the secret key of user , is the most critical element. Recall that and is the decryption key of the underlying building block PKE. The sibling of leaf knows everything about except . This gives us a hint for revocation. To revoke user , we can change the decryption key in into a new one and this fresh decryption key will not issued to the revoked user . As long as the essential element is missing, user will not be able to decrypt anything. Now we outline how the revocable IBE works.

The tree is updated according to the revoked users.

- If a leaf is revoked during time period , then a new public/secret key pair will generated with for this leaf. As a result, is replaced with a fresh value . This fresh value will not consistent to what the father node of has. Therefore, we have to change the attachments of all nodes along the path from the revoked leaf to root bottom upward.

- For i from down to 0Let . Choose random coins ; ;Here if is not defined, where .

In this way, a new tree is built with root attached with new value . Please Please note that the hash keys remain unchanged.

When revocation happens, what a sender does is updating the new hash value , then invoking the encryption algorithm for encryption.

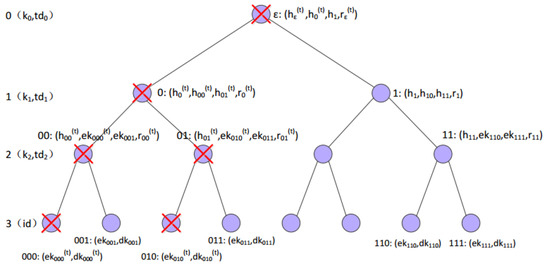

For decryption to go smoothly, the IBE system has to issue updating keys to users. The updating key includes all the information of the nodes on the paths from revoked leaves to the root, but the new is not issued. In Figure 3, for example, two users, namely 000 and 010, are revoked and determine two paths. Then all the nodes along the two paths are marked with cross. All the nodes are updated with new attachments, but leaf 000 is only attached with a new (without ) and leaf 010 is only attached with a new (without ). The updating key are , .

Figure 3.

The IBE tree of depth when users “000” and “010” have been revoked.

Any legal user is able to update his secret key with the new attachments of nodes along the path from his leaf to the root. For example, the updated secret key of user 001 is now , . The updated secret key of user 111 is now , .

In this way, any legal user is able to decrypt ciphertexts since he knows the secret key corresponding to the new tree. Any revoked user is unable to implement decryption anymore, since the new is missing.

4. Revocable IBE Scheme

In this section, we present our construction of revocable IBE scheme from chameleon encryption (without DKER). Let PRF: be a pseudorandom function. Let be a chameleon encryption scheme and be an IND-CPA secure public-key encryption scheme. We denote by the i-th bit of and by the first i bits of . Define . We first introduce five subroutines which will be used repeatedly in our scheme (as shown in Table 4). All of these five subroutines are run by the key authority. The subroutines NodeGen and LeafGen are invoked by the key authority in setup algorithm, where NodeGen is used to generate non-leaf nodes and LeafGen to generate leaves and their parents. Just like [8], given all chameleon keys, trapdoors, a randomness s, a node v and a length parameter ℓ, the NodeGen subroutine generates four values stored in node v: the hash value of the node , the hash value of it left-child node , the hash value of it right-child node , and the randomness of this node . Given all chameleon keys and trapdoors of the -th level, a randomness s, a node v in the -th level and a length parameter ℓ, the LeafGen subroutine generates two pairs of public/secret keys , of the scheme, and generates the hash value and the randomness of the node v. The children of v are two leaves associated by and . Each user can be uniquely represented by a leaf node. The subroutine FindNodes, subroutine NodeChange and subroutine LeafChange are invoked by the key authority in key update algorithm. Given a revocation list , a time and the global key list , subroutine FindNodes outputs all leaves which are revoked at time and all their ancestor nodes. Given a chameleon key, a chameleon trapdoor, a node v, two hash values of the two children of node v and a randomness s, subroutine NodeChange outputs a new hash value and a new randomness for node v. Given a leaf node v, a time , a randomness s, subroutine LeafChange outputs a fresh public key by invoking the key generation algorithm of .

Table 4.

Five subroutines run by the key authority.

Construction of RIBE.

Now we describe our revocable IBE scheme .

- Setup: given a security parameter , an integer n where is the maximal number of users that the scheme supports. Define identity space as and time space as , and do the following.

- Sample .

- For each , invoke .

- Initialize key list , public list , key update list and revocation list .

- ; ; .

- Output .

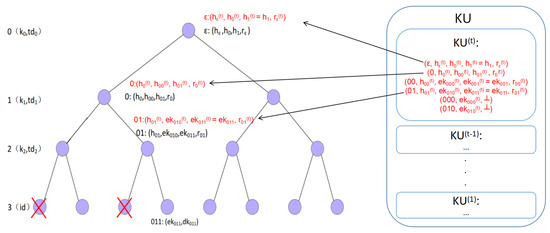

- Private Key Generation See Figure 4 for illustrations.

Figure 4. The illustration of Private Key Generation for user “110”. The private key of user “110” collects all the node values along the path from “110” to “” in the tree.

Figure 4. The illustration of Private Key Generation for user “110”. The private key of user “110” collects all the node values along the path from “110” to “” in the tree.- Parse and .

- , where is the empty string.

- For all :,,.

- For :,,.

- and .

- Output .

- Key Update Generation: See Figure 5 for illustrations.

Figure 5. The illustration of when users “000” and “010” have been revoked at time slot .

Figure 5. The illustration of when users “000” and “010” have been revoked at time slot .- Parse , and .

- . // stores all revoked leaves and their ancestors

- If , Output() //stay unchanged.

- Set key update list .

- For all node such that : // deal with all leaves in Y,. // new attachments for all leaves in Y.

- For to 0: // generate new attachments for all non-leaf nodes in Yall node and :, .()s.t.,;..

- and .

- Output .

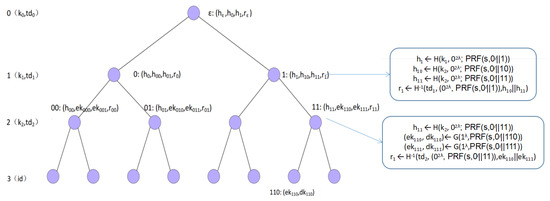

- Decryption Key Generation: See Figure 6 for illustrations.

Figure 6. The illustration of the Decryption Key Generation for user “011” when users “000” and “010” have been revoked at time slot t. For i from 1 to , the node values along the path from “011” to “” in the tree will be replaced by the corresponding node values in . The decryption key of user “011” collects all the updated node values along the path from “011” to “” in the tree.

Figure 6. The illustration of the Decryption Key Generation for user “011” when users “000” and “010” have been revoked at time slot t. For i from 1 to , the node values along the path from “011” to “” in the tree will be replaced by the corresponding node values in . The decryption key of user “011” collects all the updated node values along the path from “011” to “” in the tree.- , where is the empty string.

- Parse mpk and .

- From retrieve a set .

- For each with in ascending order, does the following:to :(Recall ).:.

- If s.t. : is revoked at.

- Output

- Encryption:We describe two circuits that will be garbled during the encryption procedure.

- -

- Compute and output .

- -

- : Compute and output , where is the short for .

Encryption proceeds as follows:- Retrieve the last item from . If , output ⊥; otherwise .

- Parse mpk.

- .

- For to 0,and set .

- Output , where is the bit of .

- Decryption

- , where is the empty string.

- Parse mpk and , where .

- Parse

- Set .

- For to :(Recall ;, set and , and for each ,, set and for each , compute

- Compute .

- Output .

- Revocation:

- Parse .

- Update the revocation list by .

- .

- Output .

Remark.

It is possible for us to reduce the cost of users’ key updating in our construction. Now we provide a more efficient variant of decryption key generation algorithm . With this variant algorithm, if a user has already generated a key at time period where , he or she can use as the input instead of and generates the decryption key with lower computational cost. The algorithm proceeds as follows:

Decryption Key Generation:

- , where is the empty string.

- Parse mpk and .

- If , Output ⊥.

- If , Output .

- From retrieve a set .

- For each with in ascending order, does the following:to :(Recall ).:.

- If s.t. : is revoked at.

- Output .

4.1. Correctness

We first show that our revocable IBE is correct. During the time slot , the key updating algorithm (together with the key generation algorithm ) uniquely determines a fresh tree of time . The root of the fresh tree has attachment . Set , where is the empty string. Please Please note that each uniquely determines a path (from the root of the tree to the leaf of ). records all non-leaf nodes on the path. For all nodes , we have , and if .

Consider the ciphertext , which is the output of . Consider the secret key , which is the output . Obviously, is exactly the the secret key of in the tree (of time ). As long as the used in to generate is identical to the in , the decryption can always recover the plaintext due to the correctness of the DG scheme.

Below we show the details of the correctness (this analysis is similar to that in [8]). For all nodes , we have the following facts.

- Recall that and are the output of .

- Due to the correctness of the chameleon encryption, we know that given one can recover by decrypting. And is the label for the next garbled circuit .

- When , we obtain the set of labels . Recall that and are the output of . And is the result of selected by . Thus,Due to the correctness of , given decryption key , one can always recover the original message m correctly with .

4.2. Security

In this subsection, we prove that our revocable IBE scheme is IND-ID-CPA secure. Assume q is a polynomial upper bound for the running-time of an adversary , and it is also an upper bound for the number of ’s queries (which contains private key queries, key update queries, and revocation queries).

Theorem 1.

Assume that is the size of the time space and be the maximal number of users. If is a pseudorandomn function, the garbled circuit scheme is secure, the chameleon encryption scheme is secure and is IND-CPA secure, the above proposed revocable IBE scheme is adaptive-IND-ID-CPA secure (without decryption key exposure resistance) More specificly, for any PPT adversary issuing at most q queries, there exist PPT adversaries , , and such that

Proof.

The full proof of Theorem 1 is in Appendix B.1. □

5. Revocable IBE Scheme with DKER

In this section, we present the construction of revocable IBE scheme with decryption key exposure resistance from the CDH assumption. In [24], Katsumata et al. provided a generic construction of RIBE scheme with DKER from a hierarchal IBE (HIBE) scheme (the formal definition of HIBE is provided in Appendix A) and a RIBE scheme without DKER. Following this idea, based on the previous RIBE scheme in Section 4 and a HIBE scheme in [8], both of which are based on the CDH assumption, we can construct a revocable IBE scheme with DKER from the CDH assumption.

Let , and denote identity space, time period space and plaintext space respectively. We assume and . and , . In addition, we assume .

Construction of RIBE with DKER.

Now we describe our revocable IBE scheme with DKER following [24].

- : given a security parameter , an integer n where is the maximal number of users that the scheme supports, i.e., . Define the time space as .

- Run .

- Parse .

- Run .

- Output .

- :

- Parse and .

- Run .

- Run .

- Output .

- :

- Parse and .

- Run .

- Output ().

- :

- Parse and .

- Run .

- Run .

- Output .

- :

- Parse .

- Sample a pair uniformly at random, subject to .

- Run .

- Run .

- Output .

- :

- Parse and .

- Run .

- Run .

- Output .

- :

- Run .

- Output .

Obviously, the correctness of scheme follows from the correctness of the underlying RIBE scheme and HIBE scheme. The security of scheme is guaranteed by the following theorem.

Theorem 2.

(Theorem 1 in [24]) If the underlying RIBE scheme in the above RIBE scheme Π is selective-IND-ID-CPA secure but without decryption key exposure resistance (DKER), and the underlying HIBE scheme in Π is selective-IND-ID-CPA secure, then the resulting RIBE scheme Π is selective-IND-ID-CPA secure with DKER.

Please note that our RIBE scheme in Section 4 is adaptive-IND-ID-CPA secure without DKER and the hierarchal IBE constructed in [8] is selective-IND-ID-CPA secure. Both of and are based on the CDH assumption. Following Theorem 2, the constructed RIBE scheme will be selective-IND-ID-CPA secure with DKER based on the CDH assumption.

Corollary 1.

When instantiating the building blocks with our RIBE scheme in Section 4 and the hierarchal IBE in [8], the RIBE scheme Π is selective-IND-ID-CPA secure with DKER based on the CDH assumption.

6. Server-Aided Revocable IBE Scheme

In this section, we present a server-aided version of our revocable IBE scheme. Following the ideas in Section 4 and Section 5, we use a standard HIBE scheme in [8] as a building block to construct such a SR-IBE , so that can obtain DKER. To describe our server-aided revocable IBE scheme , we make use of these five subroutines (NodeGen, LeafGen, FindNodes, NodeChange, LeafChange) as defined in Section 4.

Let , and denote the identity space, the time period space and the plaintext space of scheme respectively. Let and denote the identity space and the plaintext space of scheme respectively. For all and all , we assume . In addition, we assume .

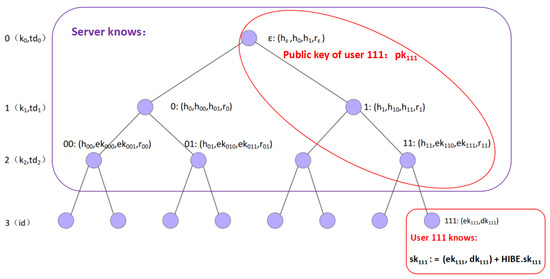

Idea. To convert the RIBE scheme with DKER in Section 5 to the SR-IBE scheme , the problem is how to divide the decryption ability between the server and the users.

- Key Generation: Recall that in RIBE the secret key of a user is . Moreover, as shown in Figure 2, the RIBE private key can be treated as a path from the root to the leaf corresponding to in a tree. Now for SR-IBE , we divide the RIBE private key into two parts, the non-leaf part and the leaf part. The non-leaf part (we name it ) is assigned to the server and the leaf part () (in fact is enough) to user . Besides, user is also assigned with the HIBE private key . This is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Separation of to the server and the user “111” in SR-IBE , where is the public key and is the private key of user “111”.

Figure 7. Separation of to the server and the user “111” in SR-IBE , where is the public key and is the private key of user “111”. - Key Update: If a user has been revoked in RIBE , the updating information in the leaf node corresponding to the user will not be issued. In other words, all the key updating information only occurs in the upper part of the tree excluding the leaves. Therefore, in SR-IBE the key authority can issue the key updating list to the server and the server is in charge of updating keys for users.

- Decryption: Recall that in the RIBE scheme with DKER in Section 5, the ciphertext consists of two parts: the ciphertext of the RIBE scheme and the ciphertext of the HIBE scheme . To decrypt in SR-IBE , the decryption is implemented from the top to the bottom along the path in the tree. The server will decrypt the upper non-leaf part while the user will decrypt the leaf part. Meanwhile, the user is alway able to use and time slot to compute and decrypt with it. The process is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. The process of the SR-IBE scheme.

Figure 8. The process of the SR-IBE scheme.

Construction of SR-IBE.

Now we describe our server-aided revocable IBE scheme .

- : given a security parameter , an integer n where is the maximal number of users that the scheme supports. Define identity space as and time space as , and do the following.

- Sample .

- For each , invoke .

- Initialize key list , public list , key update list and revocation list .

- Run .

- ; ; .

- Output .

- Parse , and .

- , where is the empty string.

- For all :,,.

- For :,,.

- and .

- Output .// This algorithm is almost the same as the Private Key Generation algorithm in Section 4 except that there is no in .

- :

- Parse , and .

- . // stores all revoked leaves and their ancestors

- If , Output()

- Set key update list .

- For all node such that : ,. .

- For to 0: all node and :, .()s.t.,;..

- and .

- Output .// This algorithm is identical to the Key Update Generation algorithm in Section 4.

- :

- , where is the empty string.

- Parse and .

- From retrieve a set .

- For each with in ascending order, does the following:to :(Recall ).:.

- Output// This algorithm is almost the same as the Decryption Key Generation algorithm in Section 4 except that all update operations do not involve leaf nodes, i.e., .

- Parse and .

- Run .

- .

- Output .

- Parse .

- Run .

- .

- Output .

- :Same to the encryption algorithm in Section 4, we use these two circuits that will be garbled during the encryption procedure.

- -

- Compute and output .

- -

- : Compute and output , where is the short for .

Encryption proceeds as follows:- Retrieve the last item from . If , output ⊥; otherwise .

- Parse .

- Sample a pair uniformly at random, subject to .

- Run .

- .

- For to 0,and set .

- Output , where is the bit of .

- Output .

- , where is the empty string.

- Parse , and , where .

- Parse

- Set .

- For to :(Recall ;, set and , and for each ,, set and for each , compute

- Compute .

- Output// This algorithm is almost the same as the Decryption algorithm in Section 4 except that this algorithm omits the last step, i.e., it does not recover from f.

- Parse , and .

- Run .

- Run .

- Output

- :

- Parse .

- Update the revocation list by .

- .

- Output .

Obviously, the correctness of this scheme follows from the correctness of the RIBE scheme described in Section 4 and the HIBE scheme used as the building block. The security of scheme is guaranteed by the following theorem.

Theorem 3.

If is the hierarchal IBE constructed in [8], the above server-aided revocable IBE scheme Σ is selective-SR-ID-CPA secure (with decryption key exposure resistance ) based on the CDH assumption.

Proof.

The full proof of Theorem 3 is in Appendix B.2. □

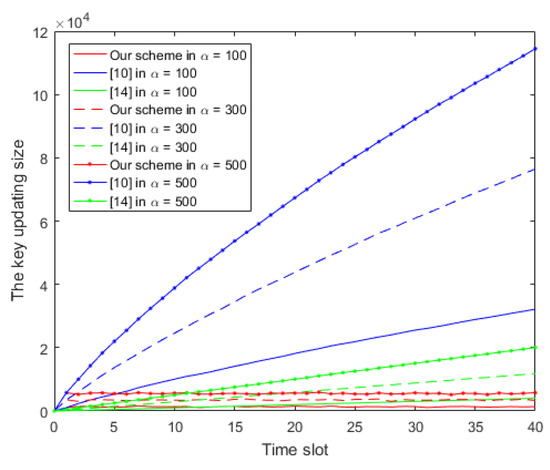

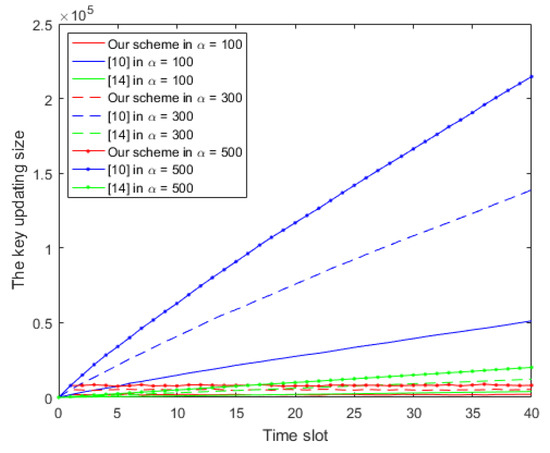

7. Analysis of Key Updating Size

In this section, we analyze the key updating efficiency of our revocable IBE scheme. Different from an IBE scheme, a revocable IBE scheme has enormous cost on the publishing updating keys at each time slot. In our RIBE, the number of updating keys is linear to the number of updated nodes. Therefore, we focus on the number of updated nodes for the performance. The advantage of our RIBE lies in the fact that the nodes that needs to updated is only related to the number of newly revoked users in the past time slot. More precisely, in all the three schemes proposed in this paper, the number of nodes needs to be updated in each time plot is at most . Thus the key updating size of our scheme is at most . If there is no new users revoked in the previous time slot, then key updating is not necessary at all.

Recall that in the most of RIBE schemes, the size of updating keys is closely related to the total number r of all the revoked users across all the past slots. For example, in [10] the size of updated key during each time slot is of order , where N is the number of users. In addition, in [14], the size of updated key during each time slot is of order .

For simulation, we use Poisson distribution to simulate the number of revoked users at each time period, where denotes the expected number of revoked users in each time slot. At a time slot , we sample a random number following the Poisson distribution parameterized by , and denotes the number of revoked users at time slot t. The total number of the revoked users up to time slot is given by . We evaluate the key updating sizes in our RIBE, the RIBE in [10] and the RIBE in [14]. Since all the our three schemes share the same updating complexity in each time plot, we only simulate our RIBE scheme without DKER and compare the results with the RIBE scheme in [10] and the RIBE scheme in [14]. The simulation results for and are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10 respectively.

Figure 9.

N = 20.

Figure 10.

N = 25.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H.; Methodology, Z.H. and S.L.; Simulation, K.C. and Z.H.; Validation, J.K.L.; Formal Analysis, Z.H. and S.L.; Investigation, K.C.and J.K.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Z.H. and S.L.; Writing—Review & Editing, K.C.and J.K.L.; Visualization, K.C.; Supervision, J.K.L.; Project Administration, S.L.; Funding Acquisition, S.L. and K.C.

Funding

Ziyuan Hu and Shengli Liu were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC Grant No. 61672346). Kefei Chen was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFB0802000), NSFC (Grant No. U1705264) and (Grant No. 61472114).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Special thanks go to Atsushi Takayasu who helped us to give a better presentation of this paper and told us their work of converting a RIBE scheme without DKER to a RIBE scheme with DKER.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Hierarchical Identity Based Encryption

We formally define Hierarchical Identity Based Encryption (HIBE). A HIBE scheme consists of four PPT algorithms . Let denote the message space and the identity space.

- Setup: The setup algorithm is run by the key authority. The input of the algorithm is a security parameter . The output of this algorithm consists of a pair of key . In formula,

- Key Generation: The key generation algorithm is run by the key authority. It takes a secret key ( for ) and an identity as the input. The output of this algorithm is . In formula, .

- Encryption: The encryption algorithm is run by the sender. It takes the master public key , an identity and a plaintext message as the input. The output of this algorithm is the ciphertext . In formula, .

- Decryption: The decryption algorithm is run by the receiver. The input of this algorithm consists of the master public key , the secret key and the ciphertext . The output of this algorithm is the plaintext . In formula, .

Correctness.

For all , all , , , all and , it holds that .

Security.

Now we formalize the security of a revocable IBE. We first consider a oracle key generation oracle . This oracle takes an identity as the input and outputs .

Definition 5.

Let be a hierarchical IBE scheme. Below describes an experiment between a challenger and a PPT adversary .

| . |

The experiment has the following requirements for .

- The two plaintexts submitted by have the same length, i.e., .

- If has queried to oracle , then cannot be the a prefix of .

A hierarchical IBE scheme is selective-IND-ID-CPA secure if for all PPT adversary , the following advantage is negligible in the security parameter λ, i.e.,

Appendix B. Proofs of Theorems

Appendix B.1. Proof of Theorem 1

Proof.

The proof consists of hybrids, , {, , , , }, ⋯, , and we will show that adjacent hybrids are computational indistinguishable. Compared with , hybrid has small changes in how the oracle queries are answered and/or the challenge ciphertext is generated. Denote by the event that the hybrid outputs 1.

- : This hybrid is just the original experiment (without oracle ) as shown in Definition 1. ThusSpecifically, in this hybrid, the challenger will first invoke to obtain where . sends to the adversary and answers oracle queries as follows.

- Private key generation oracle . Upon receiving ’s query , the challenger invokes and returns to .

- Key update oracle . Upon receiving ’s query , does as follows:For from 1 to :.ParseReturns to .

- Revocation oracle . Upon receiving ’s query an and a , invokes and parses . It returns to .

- : In this hybrid, we change how the challenger answers oracle and oracle . Recall that in , the subroutines NodeGen and LeafGen are involved in RIBE.KG when answering queries to the oracle , and the subroutines NodeChange and LeafChange are involved in RIBE.KU when answering queries to the oracle A pseudo-random subroutine is invoked in all the four subroutines. Now in , this will be replaces by a truly subroutine . Note that can efficiently implement the truly subroutine : Given a fresh input x, chooses a random element R in as the output of . records locally. If x is not fresh, retrieves R from its records.Any difference between and will lead to a distinguisher , who can distinguish from . Hence

- for : In this hybrid, challenger changes the generation of the challenge ciphertext. Recall that the challenge ciphertext . In hybrid , invokes the simulator provided by the garbled circuit scheme to generate the first garbled circuits . Meanwhile, for , the input of the is the chameleon encryption ciphertexts. We stress that the labels satisfy . Please note that needs the hash value with . Therefore the challenger has to determine first with . Then invokes to generate , and invokes to generate the rest circuits. Below is the detailed description of the generation of the challenge ciphertext by .Assume ’s challenge query as . first chooses a random bit , and encrypts under in as follows:

- Define , where is the empty string. Determine the values which are the values attached to all nodes on the path from the root to .

- -

- .

- -

- .Retrieve from .

- -

- .Parse , where. Please note that if has been revoked before .

- , where .

- For to ,Set .

- For to 0, set , where if .and set .

- Output , where is the bit of .

Please note that the randomnesses in and are generated by random subroutines instead of the . - for : This hybrid is the same as except that the challenger changes the way of generating and when answering private key queries and the way of generating and when answering key update queries for . For , set . In addition, setwhere and . Specifically, changes the generation process of fromtouses the same way to generate , i.e., is chosen randomly, and .Due to uniformity properties of the chameleon hash, hybrids and are statistical indistinguishable. So

- for : This hybrid is the same as except step 3 (as shown in in detail). Specifically, set . changes the generation process of garbled circuits fromand setting toand setting .Since is exactly the output of , the indistinguishability of and directly follows from the security of the garbled circuit scheme. If there is a PPT adversary who can distinguish and with advantage , then we can construct a PPT algorithm who can break the security of the garbled circuit scheme with same advantage . Please note that can generate itself and simulate all the oracles for perfectly. embeds its own challenge to . If is generated by , perfectly simulates . If is generated by , perfectly simulates . Hence

- for : This hybrid is the same as except step 4 (as shown in ). Challenger changestoPlease note that is not used any more, the indistinguishability between and can be reduced to the security of the chameleon encryption scheme defined in Section 2.7. We need hybrids, , to prove this, where is the same as except the generation of . SetIn ,Obviously, is the same as and is the same as . Please note that the only difference between and is , whereIf there is a PPT adversary who can distinguish and with a advantage for , we can construct a PPT distinguisher can use this adversary to break the security of the chameleon encryption scheme with the same advantage . simulates () for as follows:

- receives a hash key from it own challenger of the chameleon encryption scheme.

- generates . resets . Now does not know the corresponding chameleon hash trapdoor . Then sends to .

- can perfectly simulates all oracles for since these oracles do not need the trapdoor anymore.

- When receiving the challenge query , sets, (Please note that is chosen randomly).

- -

- generates according to (A3), just like ().

- -

- To generate , does the following. It computes but leaves undefined. Set and , where . sets its own challenge query as . Then the challenger of generates a challenge ciphertext and sends it to . sets . In addition, it computes as (A7).

- -

- generates according to (A4), just like ().

- -

- sends the challenge ciphertext.

- If returns a guessing bit to , returns to its own challenger.

If is the chameleon encryption of , simulates perfectly for . If is the chameleon encryption of , simulates perfectly for . If can distinguish these two hybrids with advantage , can break the security of the multi-bit chameleon encryption with the same advantage . Therefore,Recall that is the same as and is the same as . We have - for : In this hybrid, challenger undoes the changes made from and . It is obvious that the computational indistinguishability between and also follows from uniformity properties of the chameleon hash. Please note that is the same as . We have

- : This hybrid is the same as except that the challenger changes the way of generating . More Formally, changes the generation process of garbled circuits fromtoThis indistinguishability between and follows by the security of the garble circuit scheme. The proof is similar to the indistinguishability between and .Hence,

- : This hybrid is the same as except that the challenger replaces the ciphertext hard-coded in the circuit with .If there is a PPT adversary who can distinguish between and with advantage , there is a PPT distinguisher who can break the IND-CPA security of with advantage . First of all, We consider two kinds of adversaries:

- Type-I

- : never queries to key generation oracle for .

- Type-II

- : queries to and obtains . In this case should be revoked before .

Claim 1

.

Proof.

Suppose that issues queries to oracle , and let be ’s j-th query to . For each PPT such that , we build a PPT algorithm breaking the IND-CPA security of with the advantage . simulates () to as follows:

- generates . sends to .

- receives encryption key from its own challenger.

- chooses .

- If , since has , can perfectly simulate all oracles for as in (). embeds in the private key generation of identity (the output of ()). More specifically, invokes with a little change (framed parts are added) in the fourth step of the algorithm as follows:

- -

- For :, where .,

. . ,.Recall that is generated byin LeafGen algorithm, hence has identical distribution with . As a result, perfectly simulates the oracle on for just like ().

- receives the challenge query from .If and , aborts the game.If and there exists such that , aborts the game.Otherwise:chooses .sets its own challenge query as and .receiving the challenge ciphertext from its own challenger, computes , and continues to generate according to (A4), just like .sends the challenge ciphertext to .

- Finally, outputs what outputs.

Claim 2.

Proof.

Suppose that issues queries to oracle , and let () be ’s j-th query to . For each PPT such that , we build a PPT algorithm breaking the IND-CPA security of with the advantage . simulates () to as follows:

- generates . sends to .

- receives encryption key from its own challenger.

- chooses .

- Since has , can perfectly simulate all oracles for as in (). embeds in the key update generation (the output of ) of time . More specifically, invokes with a little change (a framed part is added) in the fifth step of the algorithm as follows:

- -

- For all node such that : ,

If , . ..Recall that is generated by in LeafChange algorithm, hence has an identical distribution with . As a result, perfectly simulates the oracle for just like ().

- receives the challenge query parsed as from .If , aborts the game.Else:chooses .sets its own challenge query as and .receiving the challenge ciphertext from its own challenger, computes , and continues to generate according to (A4), just like .sends the challenge ciphertext to .

- Finally, outputs what outputs.

□

According to (A13), Claim 1 and Claim 2, we have

- Please note that in , the challenge ciphertext is information theoretically independent of the plaintexts submitted by . So we have

□

Appendix B.2. Proof of Theorem 3

Proof.

This theorem can be derived from Corollary 1. For any PPT adversary in the selective-SR-ID-CPA security game of SR-IBE , we can construct a PPT algorithm breaking the selective-IND-ID-CPA security of RIBE such that

simulates as follows:

- generates the challenge identity and time slot to . Then sends the same challenge pair to its own challenger.

- receives from its own challenger and sets . Then sends to .

- When queries for the oracle PubKG with an identity , queries for his oracle KG with the same identity to its own challenger. Set , where is the empty string. Upon receiving the , parses , where and . sends to .

- When queries for the oracle PrivKG with an identity , queries for his oracle KG with the same identity to its own challenger. Set , where is the empty string. Upon receiving the , parses , where and . sends to .

- When queries for the oracle KU, queries for the oracle KU to its own challenger. Upon receiving the , sends to .

- When queries for the oracle DK with an identity and a time slot , queries for his oracle DK with the same pair () to its own challenger. Set , where is the empty string. Upon receiving the , parses . sends to .

- When queries for the oracle Rvk with an identity and a time slot , queries for his oracle Rvk with the same pair () to its own challenger.

- When submits the challenge query , sends the same challenge query to its own challenger. Upon receiving the challenge ciphertext , sends to .

- Finally, outputs what outputs.

Since has the same requirements as , simulates to perfectly. Therefore, we have

According to Corollary 1, we have that for PPT adversary , the advantage is negligible:

Thus we finish the proof. □

References

- Shamir, A. Identity-Based Cryptosystems and Signature Schemes. In Proceedings of the CRYPTO 1984, Advances in Cryptology, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 19–22 August 1984; pp. 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, B. Efficient Identity-Based Encryption Without Random Oracles. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Advances in Cryptology (EUROCRYPT 2005), Aarhus, Denmark, 22–26 May 2005; pp. 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, C. Practical Identity-Based Encryption Without Random Oracles. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Advances in Cryptology (EUROCRYPT 2006), St. Petersburg, Russia, 28 May–1 June 2006; pp. 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T.; Takashima, K. Fully Secure Functional Encryption with General Relations from the Decisional Linear Assumption. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Cryptology Conference, Advances in Cryptology (CRYPTO 2010), Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 15–19 August 2010; pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, C.; Peikert, C.; Vaikuntanathan, V. Trapdoors for hard lattices and new cryptographic constructions. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, Victoria, BC, Canada, 17–20 May 2008; pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Boneh, D.; Boyen, X. Efficient Lattice (H)IBE in the Standard Model. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques: Advances in Cryptology: (EUROCRYPT 2010), Monaco/Nice, France, 30 May–3 June 2010; pp. 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, D.; Hofheinz, D.; Kiltz, E.; Peikert, C. Bonsai Trees, or How to Delegate a Lattice Basis. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Advances in Cryptology (EUROCRYPT 2010), Monaco/Nice, France, 30 May–3 June 2010; pp. 523–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döttling, N.; Garg, S. Identity-Based Encryption from the Diffie-Hellman Assumption. In Proceedings of the 37th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Advances in Cryptology (CRYPTO 2017), Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 20–24 August 2017; pp. 537–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boneh, D.; Franklin, M.K. Identity-Based Encryption from the Weil Pairing. SIAM J. Comput. 2003, 32, 586–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldyreva, A.; Goyal, V.; Kumar, V. Identity-based encryption with efficient revocation. In Proceedings of the 2008 ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS 2008), Alexandria, VA, USA, 27–31 October 2008; pp. 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, A.; Waters, B. Fuzzy Identity-Based Encryption. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Advances in Cryptology (EUROCRYPT 2005), Aarhus, Denmark, 22–26 May 2005; pp. 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libert, B.; Vergnaud, D. Adaptive-ID Secure Revocable Identity-Based Encryption. In Proceedings of the Cryptographers’ Track at the RSA Conference on Topics in Cryptology (CT-RSA 2009), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–24 April 2009; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.H.; Emura, K. Revocable Identity-Based Encryption Revisited: Security Model and Construction. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Practice and Theory in Public-Key Cryptography: Public-Key Cryptography (PKC 2013), Nara, Japan, 26 February–1 March 2013; pp. 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, D.H.; Park, J.H. Efficient revocable identity-based encryption via subset difference methods. Des. Codes Cryptogr. 2017, 85, 39–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Emura, K.; Seo, J.H. New Revocable IBE in Prime-Order Groups: Adaptively Secure, Decryption Key Exposure Resistant, and with Short Public Parameters. In Proceedings of the Cryptographers’ Track at the RSA Conference on Topics in Cryptology (CT-RSA 2017), San Francisco, CA, USA, 14–17 February 2017; pp. 432–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, K.; Lee, D.H. New Constructions of Revocable Identity-Based Encryption from Multilinear Maps. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2015, 10, 1564–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lim, H.W.; Ling, S.; Wang, H.; Nguyen, K. Revocable Identity-Based Encryption from Lattices. In Proceedings of the 17th Australasian Conference on Information Security and Privacy (ACISP 2012), Wollongong, NSW, Australia, 9–11 July 2012; pp. 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayasu, A.; Watanabe, Y. Lattice-Based Revocable Identity-Based Encryption with Bounded Decryption Key Exposure Resistance. In Proceedings of the 22nd Australasian Conference on Information Security and Privacy (ACISP 2017), Auckland, New Zealand, 3–5 July 2017; pp. 184–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Deng, R.H.; Li, Y.; Liu, S. Server-Aided Revocable Identity-Based Encryption. In Proceedings of the 20th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security (ESORICS 2015), Vienna, Austria, 21–25 September 2015; pp. 286–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K.; Liu, J.K.; Wong, D.S.; Susilo, W. An Efficient Cloud-Based Revocable Identity-Based Proxy Re-encryption Scheme for Public Clouds Data Sharing. In Proceedings of the 19th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security (ESORICS 2014), Wroclaw, Poland, 7–11 September 2014; pp. 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, J.K.; Liang, K.; Choo, K.R.; Zhou, J. Extended Proxy-Assisted Approach: Achieving Revocable Fine-Grained Encryption of Cloud Data. In Proceedings of the 20th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security (ESORICS 2015), Vienna, Austria, 21–25 September 2015; pp. 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, J.K.; Wei, Z.; Huang, X. Towards Revocable Fine-Grained Encryption of Cloud Data: Reducing Trust upon Cloud. In Proceedings of the 22nd Australasian Conference on Information Security and Privacy (ACISP 2017), Auckland, New Zealand, 3–5 July 2017; pp. 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.K.; Yuen, T.H.; Zhang, P.; Liang, K. Time-Based Direct Revocable Ciphertext-Policy Attribute-Based Encryption with Short Revocation List. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Applied Cryptography and Network Security (ACNS 2018), Leuven, Belgium, 2–4 July 2018; pp. 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumata, S.; Matsuda, T.; Takayasu, A. Lattice-based Revocable (Hierarchical) IBE with Decryption Key Exposure Resistance. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2018, 2018, 420. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).