Abstract

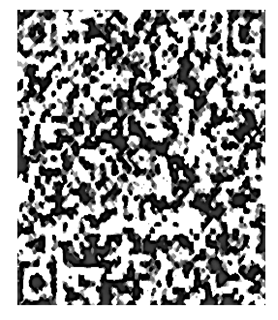

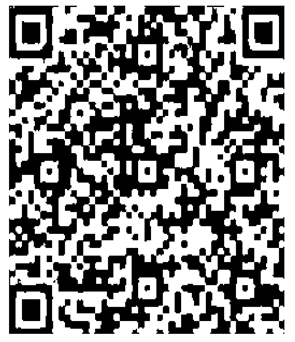

In the digital era, protecting the integrity and ownership of digital content is increasingly crucial, particularly against unauthorized copying and tampering. Traditional watermarking techniques often struggle to remain robust under various image manipulations, leading to a need for more resilient methods. To address this challenge, we propose a novel watermarking technique that integrates the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), Singular Value Decomposition (SVD), and Schur matrix factorization to embed a QR code as a watermark into digital images. Our method was rigorously tested across a range of common image attacks, including histogram equalization, salt-and-pepper noise, ripple distortions, smoothing, and extensive cropping. The results demonstrate that our approach significantly outperforms existing methods, achieving high normalized correlation (NC) values such as 0.9949 for histogram equalization, 0.9846 for salt-and-pepper noise (2%), 0.96063 for ripple distortion, 0.9670 for smoothing, and up to 0.9995 under 50% cropping. The watermark consistently maintained its integrity and scannability under all tested conditions, making our method a reliable solution for enhancing digital copyright protection.

1. Introduction

In the digital era, the rapid advancement of data transmission technologies has facilitated the effortless sharing of vast volumes of multimedia content, including images, videos, and audio files. However, this growing accessibility also increases the necessity for robust security mechanisms to preserve the integrity and ownership of digital content. One of the major challenges in this context is enabling content creators to authenticate and safeguard their intellectual property rights [1]. Unauthorized usage and copyright infringement have become pervasive due to the ease of duplication and dissemination of digital materials. Traditional approaches, such as legal agreements and manual tracking, are insufficient to ensure copyright protection in the face of rapid and often untraceable content distribution. Digital images, in particular, are highly susceptible to manipulations that can remove or distort embedded watermarks, thereby compromising copyright enforcement. Consequently, there is a pressing need for a robust and imperceptible watermarking technique capable of withstanding diverse attacks and ensuring the security and authenticity of digital media.

To address these concerns, copy-detection systems have been proposed as a potential solution. Various approaches have been investigated for image copy detection with the primary objective of comparing visual features to identify similar images. These features include color histograms, texture descriptors, and shape information. A commonly used approach is image hashing, which generates a compact digital signature for each image based on its visual attributes, enabling the comparison of signatures to estimate similarity [2]. However, this approach has several limitations. For example, it performs poorly under image modifications, can be computationally demanding, may be less accurate for certain image types, and is susceptible to false positives [3]. Image encryption provides another means of protecting content by transforming the original data into an unintelligible form [4]. A key limitation of encryption is the need for a reliable ownership-verification mechanism if an attacker decrypts the media and gains access to the content.

The most widely used approach for image authentication is digital watermarking. A digital watermark refers to concealed, encoded information that is embedded into an image to verify copyright ownership and deter unauthorized replication [5]. Early watermarking schemes were largely determined by the type of host data carrier [6]. In general, watermark embedding techniques can be categorized into spatial-domain methods [7] and transform-domain (frequency-domain) methods [8,9]. Transform-domain watermarking embeds the watermark in a transformed representation of the host signal (e.g., an image, audio, or video) [10]. Typically, this process involves transforming the host media from the spatial (time) domain to the frequency domain, embedding the watermark in the transformed coefficients, and then applying the inverse transform to obtain the watermarked media for storage or transmission [11].

Among the most significant and widely adopted techniques in this domain are transform-based methods, particularly the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT). DCT-based watermarking operates by dividing the host medium into non-overlapping blocks, subjecting each block to a DCT transformation [10]. The resulting transformed coefficients are then modified by incorporating the watermark signal, resulting in watermarked coefficients. The typical watermark signals are either a binary sequence or an imperceptible pseudo-random noise sequence that is visually indistinguishable to human observers [12]. The Fast Hadamard Transform (FHT) has also been used to achieve imperceptible embedding and a high watermark detection accuracy in digital images. Other techniques employed in frequency-domain watermarking include the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) [13], and Singular Value Decomposition (SVD).

Histogram equalization, salt-and-pepper noise, ripple effects, smoothing, and cropping are common attacks on digital watermarks. By redistributing the pixel intensity values, histogram equalization modifies an image’s contrast. By altering the image’s intensity distribution, this operation can either expose subtle watermarks or suppress them, thereby compromising both imperceptibility and robustness [14]. The salt-and-pepper attack adds black and white pixels to the image. Watermarks embedded in those areas may be obscured by this high-frequency noise, making it difficult to reliably retrieve the watermark. In a ripple attack, periodic wave-like distortions are introduced into the image, which displace watermark samples from their original positions.

This misalignment disrupts the spatial correlation required for watermark detection and often leads to partially recovered or corrupted watermarks. A smoothing attack (blurring) reduces local intensity variations by averaging pixel values within a neighborhood, which decreases image sharpness and attenuates the high-frequency components that many watermarking schemes rely on. As a result, the embedded watermark may be weakened and become less distinguishable from the host content, reducing its resilience to subsequent processing. In a cropping attack, portions of the image are removed (from the boundaries or internal regions), potentially eliminating watermark-bearing areas entirely. When the watermark is distributed across the full image, cropping can destroy critical embedded information and undermine proof-of-ownership. Because these attacks target different stages and assumptions of the watermarking pipeline, an efficient, robust, and imperceptible watermarking algorithm is required to withstand such image processing operations while preserving reliable watermark extraction.

Contribution

Many significant contributions to the advancement of ownership verification for color images are presented in this paper. A novel and robust model that incorporates various applied mathematical principles has been developed, enabling the embedding of watermarks in color images using MATLAB 2023a. We summarize our contributions as follows:

- High-Robustness Across Diverse Attacks: Our method consistently outperforms existing techniques in maintaining QR code functionality under a variety of attacks, such as ripple distortions and severe cropping, ensuring reliable digital content protection.

- Innovation in QR Code Watermarking: By combining the strengths of DWT, SVD, and Schur matrix factorization, we propose a novel approach that improves the security and durability of QR code watermarks in digital images.

- We introduce a new method for embedding watermarks in digital images that leverages a combination of DWT, SVD, and Schur matrix factorization.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows. Section 1 provides an introduction to the challenges and significance of copyright protection in the digital era. Section 2 reviews the existing literature in image watermarking methods, focusing on the strengths and limitations of various approaches. Section 3 presents the proposed watermarking model and details the mathematical principles and techniques employed, including DWT, SVD, and Schur matrix factorization. Section 4 describes the experimental setup and methodology used to evaluate the performance of the proposed model against various types of attacks. Section 5 discusses the results of the experiments and compares the effectiveness of the proposed model with existing techniques. Section 6 contains the conclusion of the paper, summarizing the key findings and suggesting directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

According to Sharma et al. (2020) [15], a nature-inspired approach for secure and robust color image watermarking with pseudorandom ordering was introduced. The main issue was the lack of adequate protection for multimedia information from unauthorized copying and modification. The work assumed that a hybrid watermarking method based on SVD and DWT, with an artificial bee colony (ABC) optimized technique, is able to maintain the balance between imperceptibility and robustness. The proposed approach embedded a scrambled color watermark into the RGB planes by modifying the singular values of the host images, using chaotic maps to enhance security. The effectiveness of the proposal against different attacks is evidenced, and the NC value for the recovered watermark using histogram equalization was 0.8931. This performance can be attributed to the computational efficiency and ease of implementation of DWT and SVD, while the ABC optimization primarily tunes the scaling factor. But it should be noted that their gap under histogram equalization attacks is that the robustness was relatively low, indicating that improving performance under this type of distortion remains challenging.

Anand and Singh (2020) [16] reported that the study’s goal was to make medical information security better in telehealth services by using a better watermarking method. The study concentrated on integrating multiple watermarks into medical images utilizing DWT and SVD in conjunction with encryption and compression techniques. The goal of the method was to make sure it could withstand different types of attacks while still keeping the image quality high. The process used the Hamming code for the text watermark, embedded it in the DWT-SVD domain, and then used Chaotic-LZW and HyperChaotic-LZW methods to encrypt and compress it. The results showed that the system was very strong with an NC value of 0.8716 for histogram equalization attacks. Also, the NC value for salt-and-pepper noise at a density of 0.001 was 0.7751 using the chaotic-LZW method and 0.9687 using the hyperchaotic-LZW method. Our method achieved higher NC values even at much higher noise densities (up to 50%), showing that it is more robust. However, a limitation of their work is reduced robustness under certain attack conditions, which motivates further improvements.

Saritas and Ozturk, 2023 [17] proposed a method to strengthen copyright protection by a hybrid CT- and DCT-based blind and robust color image watermarking scheme. Their work focused on embedding a 24-bit watermark within an 8 × 8 image block employing one-level CT and block DCT using the Cb color channel of the YCbCr color model. The primary objective was to enhance the robustness, imperceptibility, and security of the watermark. In their process, they first transformed the original RGB color image to YCbCr, and then CT was performed on the Cb component, which was followed by embedding a scrambled watermark using the Arnold transform. Experiment results demonstrated good robustness compared to other attacks with an NC value of 0.9020 under salt-and-pepper noise (density: 2%). Furthermore, in the 50% cropping attack, the NC values varied within [0.7075, 0.7092]. Their technique exhibited suboptimal robustness under higher noise levels and heavy cropping attacks. We tackle this in our work by having high NC values even at 50% noise density and 50% cropping attacks.

Rahardi et al. (2022) [18] propose a robust image watermarking technique using DCT for copyright protection on color images. The study addresses the challenge of unauthorized use of images shared on social media platforms. The method embeds watermark data into the DCT coefficients of 8 × 8-pixel blocks of the host image, ensuring the watermark remains robust against various attacks. They focus on maintaining image quality while embedding and extracting watermark data. Their methodology divides each channel of the host image into 8 × 8 pixel blocks, transforms these blocks into the frequency domain using DCT, and embeds the watermark data into specific DCT coefficients. The watermarked image demonstrated resilience to attacks with NC values of 0.7667 for salt-and-pepper noise and 0.7913 for the ripple attack and low bit error rate (BER) values. A remaining gap is further improving robustness against more complex tampering operations while reducing computational cost.

Han et al. (2021) [19] stated that the main goal is to fix the security problems that come up when medical images are stored and sent. The study underscores the necessity of safeguarding sensitive patient information contained within medical images from unauthorized access and manipulation. The main research question is how to make a strong zero-watermarking method that can stand up to local nonlinear geometric attacks. The method involves using a pretrained VGG19 to obtain deep features from medical images, changing these features with the Fourier transform, and then using a mean-perceptual hashing algorithm to make a strong zero-watermark. Their results show that the proposed algorithm was very strong against different types of attacks, such as ripple, extrusion, spherical, and rotation distortions. The NC value for ripple distortion at 150% is 0.87595. The study offers substantial insights for safeguarding the security of medical images within digital healthcare systems. However, further work is needed to improve the algorithm’s performance and reliability.

According to Abodena (2024) [20], the authors present a clear and reliable way to hide a watermark inside a black-and-white image by using Schur decomposition and checking the image’s entropy to protect copyrights. The study examines the common problems of sharing, changing, and copying digital images online, and it focuses on how to keep these images secure. The main research question is how to insert a watermark and later extract it while keeping it invisible and difficult to remove. The method uses a two-level wavelet transform on the image and then applies DCT to the high-frequency region. After this step, the DCT values are divided into small blocks, and Schur decomposition is used to place the watermark. The results show that the method keeps the image looking good and remains strong, reaching an NC of 0.891 even when half of the image is cropped. Further work is needed to improve performance and extend the method to color images.

Altay and Ulutas (2024) [21] put forward two innovative biometric watermarking schemes utilizing QR decomposition and Schur decomposition within the redistributed invariant discrete wavelet transform (RIDWT) domain to address ownership disputes. The study underscores the necessity for secure and resilient watermarking methodologies to safeguard copyright in the prevalent digital media-sharing epoch. In their approach, biometric iris images are embedded into color images. The method uses RIDWT to break down the Y channel of color images in the YCbCr space, chooses low-frequency sub-band blocks based on standard deviation, and embeds the biometric watermark using QR or Schur decomposition. The results show that the system is strong against attacks with NC values of 0.911 for salt-and-pepper noise (3%). A remaining gap is the resilience of watermark extraction under high-intensity noise attacks and complex tampering scenarios.

According to Yuan et al. (2024) [22], the authors present a novel zero-watermarking technique for encrypted medical images using DWT and Daisy feature descriptors to address problems such as information leakage and malicious tampering. The research work concentrates on web-based security to preserve the medical images during transmission. The process consists of a medical image being encrypted with DWT-DCT and logistic mapping, which is followed by three stages of DWT, the Daisy descriptor matrix calculation, and a 32-bit binary feature vector produced via perceptual hash. Their findings show that the algorithm obtained limited robustness against a number of attacks with the value of NC being 0.72 under 30% cropping along the Y-axis and 0.63 under 30% cropping along the X-axis. In light of these findings, further work is required to enhance performance on color images and improve robustness.

Mareen et al. (2024) [23] proposed a blind deep-learning watermarking method that extends the HiDDeN encoder–decoder framework with differentiable attack layers to improve robustness against geometric transformations. The architecture inserts noise layers for JPEG via a differentiable JPEGdiff module, as well as rotation, rescaling, translation, shearing, and mirroring, and is trained on COCO images with randomly generated 30-bit messages; models include an identity baseline (no noise), several “specialized” single-attack variants, and a “combined” model with multiple attacks sampled during training. Reported imperceptibility shows SSIM for the combined model and ≈0.977 for RivaGAN. While robustness curves indicate that the identity model is weak for most attacks, specialized models never drop below ∼65% bit accuracy. In contrast, the combined model markedly improves geometric robustness but is weaker than specialized models for JPEG/blur, and RivaGAN is strongest for JPEG/blur yet inferior under geometric attacks. While this work advances blind, learning-based geometric resilience, it lacks a theory-grounded embedding rationale in transform subbands, and it also omits an explicit imperceptibility–robustness control like an sweep with a PSNR dB constraint. Our method complements these gaps by using a DWT+Schur+SVD pipeline with dual LL/HH embedding, which is a principled -sensitivity protocol.

Zhang et al. (2025) [24] propose ZoDiac, a stable-diffusion-based framework that embeds zero-bit invisible watermarks into existing images by optimizing a latent vector and encoding a concentric ring pattern in its Fourier domain, which is followed by DDIM inversion for detection and an adaptive mixing step to preserve perceptual quality (PSNR –30 dB; SSIM ). Their objective is to overcome diffusion-model attacks like (Zhao23) that defeat classical and learning-based watermarking; experiments on MS-COCO, DiffusionDB, and WikiArt show high pre-attack detectability and strong post-attack robustness, including dominance under composite attacks excluding rotation, with WDR often >0.98 and clear advantages over DwtDct, RivaGAN, SSL, CIN, and StegaStamp. The authors also report compatibility across SD backbones and analyze trade-offs from SSIM/detection thresholds; a noted limitation is sensitivity to rotation (mitigated by rotation auto-correction at the cost of higher FPR) and the zero-bit nature of the mark (no payload decoding).

Cheng et al. (2025) [25] propose a forensic pipeline for non-aligned double-JPEG (NA-DJPEG) images that first estimates DCT grid shifts via a shallow two-branch CNN and then re-crops by to realign with the primary compression before running standard quantization-step estimators. A learnable Second-Order Difference (SOD) layer enhances blocking-artifact cues, while a Color Fine-Grain (CFG) module augments YCbCr with a computed channel to exploit chrominance traces. The network avoids pooling to preserve subtle periodicities. Experiments on UCID, RAISE, and NRCS show consistently higher accuracy in misalignment recovery across patch sizes and quality factors with pronounced gains when the second quality factor is high. Although effective for recompression forensics and parameter inference, it targets grid-shift estimation rather than payload-bearing watermarking: it neither embeds nor decodes structured messages and lacks an explicit imperceptibility–robustness control protocol. Our study fills this gap by delivering a DWT+SVD+Schur QR watermark with dual LL/HH embedding and an sweep ensuring PSNR/SSIM and decoding robustness under diverse attacks.

Gao et al. (2025) [26] introduce “Encrypt a Story” (EAS), which is a selective video-encryption framework that concentrates cryptographic effort on temporally salient actions to reduce cost while preserving security. EAS first segments actions using an MSLID-TCN, and then it encrypts only the critical segments via plane scrambling and diffusion driven by a discrete sinusoidal memristive Rulkov neuron map (DSM–RNM). Keys and initial states are derived using SHA–256 from segment content, and the DSM–RNM keystream enables high-sensitivity diffusion. Experiments report about a 90% reduction in total encryption time versus full-frame encryption, near-zero adjacent-pixel correlations (≈0.0014), entropy around 7.999, strong NPCR/UACI against differential attacks, NIST randomness compliance, and pronounced key sensitivity. While EAS advances efficient selective encryption and chaotic keystream design, it is not a payload-bearing watermark: it neither embeds nor decodes structured messages. Our work complements this line of work by delivering a DWT+Schur+SVD QR watermark with dual LL/HH embedding and an explicit -sweep that enforces PSNR/SSIM constraints and maintains robust, decodable QR recovery under compression, noise, geometric ripples, and cropping.

3. Preliminary

This section gives an overview of the main ideas and methods used in frequency-based watermarking. First, we discuss frequency-based watermarking, which is a common way to embed and extract watermarks from digital media. It entails altering the frequency domain of the media signal to incorporate imperceptible watermarks. Next, we look more closely at the transforms that were used, such as SVD and DWT. SVD is a strong mathematical tool that breaks down a matrix into singular values and singular vectors. It is often used to add and remove watermarks. DWT, on the other hand, is a signal processing transform that breaks a signal down into different frequency bands. This makes it easy to embed watermarks and reliably extract them under various attacks. These transforms are the basis for frequency-based watermarking methods and are very important for achieving reliable and invisible watermarking in digital media.

3.1. Frequency-Based Watermarking

Frequency domain-based watermarking is a method of inserting watermarks into digital data by operating in the frequency domain. This process changes the representation of the media from its spatial representation, where pixels are manipulated directly, to a frequency-based representation in which information is provided in terms of the frequencies that are present in the signal or image. The embedded watermark is invisible to the human eye by altering the frequency coefficients of the media; meanwhile, it still has high robustness against common attacks. Transforming to the frequency domain allows more complex manipulation to make the watermark imperceptible but robust against tampering. This work consists of three main phases for frequency-based watermarking. First, the image is transformed to the frequency domain by methods like the Discrete Wavelet Transformation (DWT). Second, the watermark is inserted into the transformed image by modifying the frequency coefficients. The image is then inversely transformed into the spatial domain to make the watermark indiscernible and visually hard to detect. The superiority of the proposed method is promising, in terms of improved imperceptibility, and superior robustness against different image processing operations such as salt-and-pepper, histogram equalization, cropping, and ripple attacks.

3.2. Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT)

The DWT is a powerful signal-processing technique widely used in image processing, data compression, and digital watermarking. Unlike the DCT, which operates only in the frequency domain, DWT works in both the time and frequency domains, providing a multi-resolution analysis. This means that DWT decomposes an image into different frequency sub-bands at various levels of resolution, capturing both coarse and fine details of the image. DWT operates by breaking down an image into four sub-bands: (LL), (LH), (HL), and (HH). The LL sub-band represents the coarse approximation of the image, containing the most significant information. The LH, HL, and HH sub-bands capture the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal details [27]. This hierarchical structure allows for an efficient representation and manipulation of the image, making DWT useful for embedding watermarks in ways that are imperceptible to the human eye. The role of Equation (1) is to retain the overall trends and basic features of the original signal, while helps in scaling and transforming the signal to focus on these low-frequency components, and in Equation (2), retains the high-frequency information, such as edges and fine details, while helps in transforming the signal to focus on these detailed components. For the inverse DWT, the original image can be reconstructed from the wavelet coefficients using Equation (3).

where the following apply:

- is the original signal or image.

- M is the total number of pixels.

- represents the approximation coefficients, capturing the coarse, low-frequency components of the image.

- are the scaling functions, which are used to project the original signal onto the low-frequency sub-space.

- are the detail coefficients, capturing the fine, high-frequency components of the image.

- are the wavelet functions, which are used to project the original signal onto the high-frequency sub-space.

- The first term in Equation (3) represents the approximation component, which is reconstructed from the approximation coefficients and scaling functions.

- The second term in Equation (3) represents the detail component, which is reconstructed from the detail coefficients and wavelet functions.

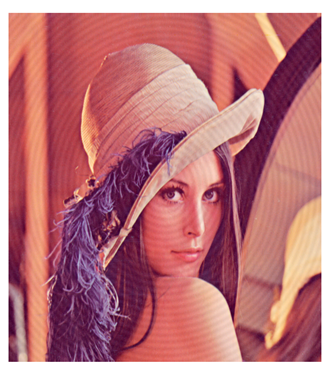

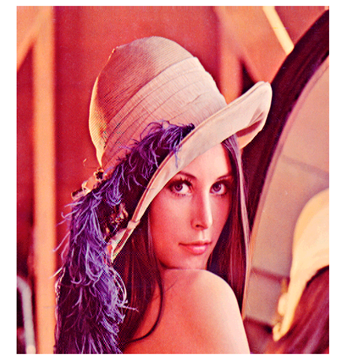

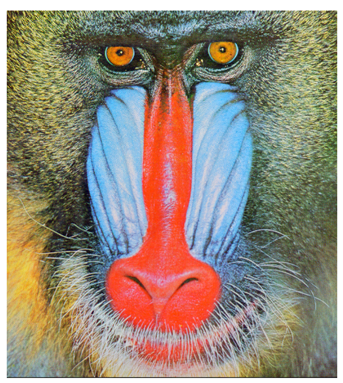

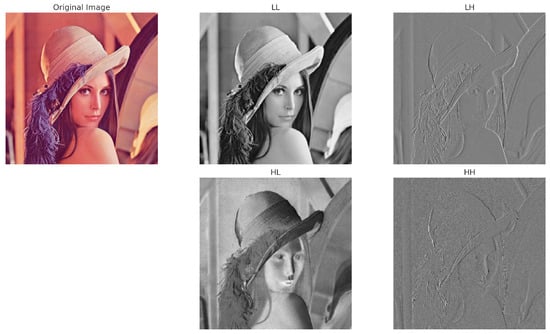

Figure 1 illustrates the application of DWT on the original image. The original image is decomposed into four sub-bands: LL, LH, HL, and HH. The LL sub-band retains the most significant features of the image, appearing as a blurred version of the original, while the LH, HL, and HH sub-bands highlight the finer details, emphasizing horizontal, vertical, and diagonal edges.

Figure 1.

DWT sub-bands of the original image.

3.3. Schur Matrix Factorization

Schur matrix factorization is a complex way to break down a square matrix into a unitary matrix and an upper-triangular matrix. This method is especially useful for many purposes, such as digital watermarking, because it makes it easy to change and fully analyze matrix properties while keeping the matrix’s natural structure. Schur factorization makes it easier to understand the properties and behavior of a matrix by breaking down complicated operations into simpler parts. Schur matrix factorization is a strong and effective way to embed digital watermarks into images. It makes it easy to insert watermark signals into images. This method breaks down a square matrix into an upper-triangular matrix and a unitary matrix. This makes sure that the original image remains intact while the watermark is added. The decomposition keeps the image’s visual quality while making the watermark harder to see and stronger [28]. Mathematically, Schur factorization is shown by Equation (4):

where A is the original matrix, is a unitary (orthogonal) matrix, and is an upper-triangular matrix. The matrix contains orthogonal eigenvectors, while preserves the significant properties of the image, ensuring minimal distortion during the watermarking process.

The Schur factorization process begins with the decomposition of the image matrix A. The image matrix A is decomposed into two matrices: and . This is achieved by first finding the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of A. The orthogonal eigenvectors form the matrix , and the upper-triangular matrix is constructed using these eigenvectors. If we apply Schur factorization to matrix A, the result is shown in Equation (5):

where denotes the conjugate transpose of .

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors are fundamental concepts in linear algebra, particularly in the study of linear transformations. An eigenvector of a matrix A is a non-zero vector v such that when A is multiplied by v, the result is a scalar multiple of v. Mathematically, this is expressed as shown in Equation (6):

where v is the eigenvector and is the corresponding eigenvalue. An eigenvalue is a scalar associated with a given eigenvector v such that when the matrix A acts on v, the result is .

To find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of a matrix A, we solve the characteristic equation as shown in Equation (7):

where I is the identity matrix of the same size as A, and det denots the determinant. The solutions to this equation, , are the eigenvalues of A. Once the eigenvalues are found, the corresponding eigenvectors are determined by solving the linear system for each eigenvalue as Equation (8):

For example, consider a simple 2 × 2 matrix A:

To find the eigenvalues, we solve the characteristic equation:

The solutions to the equation are and . For , solving gives the eigenvector . For , solving gives the eigenvector .

The next step involves embedding the watermark signal into the matrix. The embedding process modifies the singular values of , which represent the key properties of the image. These modifications are designed to be imperceptible to the human eye to ensure that the visual quality of the image remains unaffected. Let W be the watermark matrix, and let be the scaling factor for the watermark. The modified matrix after embedding can be expressed as shown in Equation (9):

After embedding the watermark, the inverse Schur factorization is applied to reconstruct the watermarked image. This step involves combining the modified with to produce the watermarked image matrix . The reconstruction can be represented as Equation (10):

3.4. Singular Value Decomposition (SVD)

SVD is a robust computational method used to decompose a matrix into three key components: left singular vectors, singular values, and right singular vectors. This technique is significant in watermark applications for tasks such as signal processing, data compression, and noise reduction. SVD allows for the transformation of complex data into a more manageable form, capturing the essential features while reducing dimensionality. By breaking down data into its core components, SVD enhances the efficiency and accuracy of various algorithms, making it an indispensable tool in modern watermark practice for analyzing and processing large datasets [29]. The SVD can be represented as Equation (11):

where:

3.5. Schur Decomposition in Watermarking and Its Complementarity with SVD

This section motivates and formalizes the role of the real Schur decomposition within our DWT-based watermarking pipeline and explains how it complements the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD). After decomposing a sub-band (LL or HH) as , the orthogonal similarity provided by Q enables numerically stable, energy-preserving mappings between the image domain and the triangular factor T, while the structure of T (diagonal quasi-eigen information with off-diagonal couplings) offers coherent loci for embedding. We then operate in the SVD domain of T to adjust the watermark strength through its singular spectrum, achieving perceptual control with minimal distortion. This Schur–SVD coupling thus balances robustness (via unitary redistribution tied to sub-band structure) and imperceptibility (via energy-aware singular-value scaling), which is particularly beneficial under filtering, histogram equalization, mild geometric distortions, and compression. The remainder of this section details the theoretical properties we exploit, the precise embedding and extraction operators, and a concise comparison clarifying the distinct contributions of Schur and SVD to the overall resilience of the scheme.

Let denote a DWT sub-band (e.g., LL or HH). The real Schur decomposition writes

where Q is orthogonal () and T is (quasi) upper–triangular. By contrast, the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) writes

with and non-negative singular values on the diagonal of .

Advantages of Schur for Watermarking

(1) Unitary energy preservation: A perturbation mapped back as preserves Frobenius norms (), yielding predictable embedding strength and numerical stability. (2) Structure awareness: The triangular factor T reflects (quasi-)eigen information on its diagonal and couplings off-diagonal. Targeting selected entries or block-diagonals of T produces coherent, globally distributed changes after similarity mapping by , which empirically improves resilience to smoothing, histogram equalization, and mild geometric distortions. (3) Well-conditioned back-projection: The orthogonality of Q avoids error amplification during forward and inverse transforms, improving backward stability in embedding and extraction.

Complementarity with SVD

Schur provides a stable, orthogonal conduit tied to the sub-band structure, while SVD supplies optimal energy compaction and fine-grained strength control via the singular spectrum:

where encodes the watermark and controls strength. The watermarked triangular factor is , and the watermarked sub-band becomes

Thus, SVD ensures perceptual economy (small, controlled adjustments in ), while Schur’s unitary similarity spreads these adjustments coherently in the sub-band, enhancing robustness without sacrificing imperceptibility. In our implementation, LL and HH are employed to balance resilience (LL) and manipulation-trace sensitivity (HH). As shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Schur vs. SVD in transform-domain watermarking (the proposed method exploits both).

At detection, is recovered as ; then, SVD-domain scaling is inverted to estimate and reconstruct the watermark. The unitary steps again preserve norms, limiting error accumulation across transforms.

4. Methodology

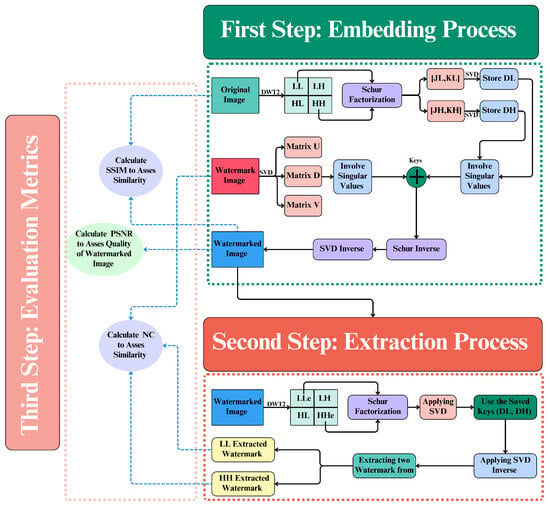

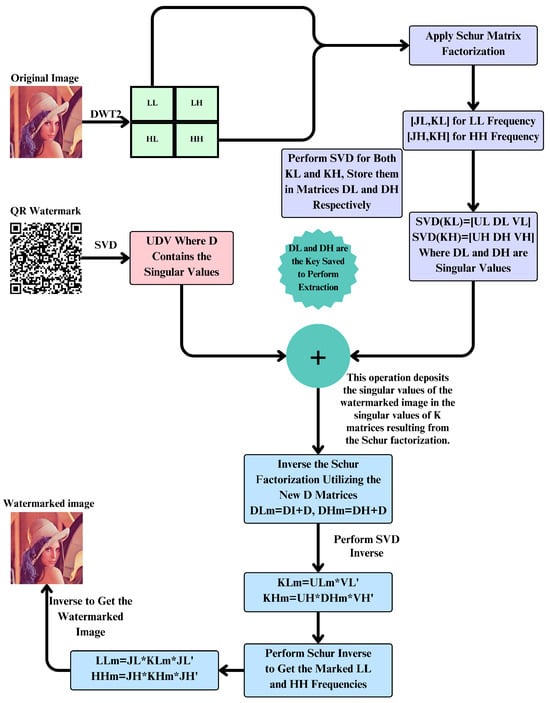

In this section, we discuss how we developed a strong and undetectable watermarking method to make it more difficult to steal digital images. The suggested method uses advanced math and signal processing to make it very hard to attack in many ways. The method uses DWT, SVD, and Schur matrix factorization in an integrated manner. These methods work together to make sure the watermark stays hidden and that people cannot change the image. The next steps describe how to embed and remove watermarks in a systematic way to protect proof of ownership of digital images. The proposed watermarking method consists of three steps: embedding, extraction, and evaluation. Figure 2 shows the whole process. The first step in embedding is to use a two-level DWT on the original image. This creates four sub-bands: LL, LH, HL, and HH. After that, Schur factorization and SVD are used to put the watermark’s information into the image’s sub-bands. The inverse process reconstructs the image with the watermark. In the extraction phase, the watermarked image goes through DWT, Schur factorization, and SVD in a manner similar to the first phase. It uses stored keys to correctly recover the embedded watermark. We use evaluation metrics like the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and the NC to validate the method works.

Figure 2.

Detailed process flow of watermark embedding, extraction, and evaluation methodology.

4.1. Watermark Embedding Schema

The watermark embedding process ensures that the watermark is imperceptible yet resilient against various attacks. This comprehensive process involves several advanced techniques including DWT, Schur matrix factorization, and SVD. Figure 3 presents our watermark embedding scheme in detail.

Figure 3.

Watermark embedding scheme.

The first step in the watermark embedding scheme is to use a two-level DWT on the original image. This breaks the picture up into four sub-bands: LL, LH, HL, and HH. DWT gives you a multi-resolution image representation, which makes it easy to work with different frequency components. It captures both big and small details, which makes it easy to add a strong watermark. DWT helps hide the watermark in a way that people cannot see it by focusing on different frequency bands. It also keeps the quality of the image overall. The LL sub-band keeps the most important parts of the image, while the LH, HL, and HH sub-bands capture smaller details. This makes them perfect for adding watermarks that cannot be seen.

In the second step, the Schur matrix factorization is carried out on the LL and HH frequency sub-bands and yields matrices for the LL band and for the HH band. Schur factorization reduces operations on a matrix by factoring it into an orthogonal matrix and an upper triangular matrix. This provides an easier way of handling the matrix characteristics for manipulations and analyses. Using Schur matrix factorization in digital watermarking is of huge benefit as it efficiently processes big matrices while the visual quality of the image is not compromised. This factorization can help to maintain the structure of the image during watermark embedding with minimal distortion while maintaining good robustness.

In the third step, SVD is used on both the and matrices to break them down into their singular values and the matrices that go with them. When you apply SVD to the watermark image, you obtain matrices U, D, and V. D has the watermark’s unique values. SVD is a strong way to break down a matrix into its most basic parts, capturing the most important parts of the image and the watermark. By changing the singular values, the embedded watermark can withstand different types of image processing attacks, making sure that the watermark embedding is strong and not noticeable, as shown in Equations (16) and (17).

In the fourth step, the singular values of the watermark matrix D are then embedded into the singular-value matrices and obtained from the Schur factorization by modifying and with the watermark singular values scaled by a factor (). The new matrices are denoted as and . Embedding singular values ensures that the watermark is integrated into the image’s core components, making it less likely to be removed or altered by common image processing operations. This method enhances the robustness and imperceptibility of the watermark, as represented in Equations (18) and (19).

The fifth step consists of applying inverse SVD to the transformed and to recover the watermarked matrices and . The inverse SVD operation reconstructs the watermarked matrices, thereby integrating the watermark into the image. This ensures the watermark remains invisible and robust without degrading the quality or integrity of the image. The inverse SVD operation must be performed to properly embed the watermark without introducing any artifacts or distortions in the image, as shown in Equations (20) and (21).

The sixth step applies an inverse Schur factorization to and in order to extract the initialized and frequencies. Taking the inverse of the Schur factorization guarantees that the adjustments made during watermark embedding are correctly captured in the output image. This operation preserves the structural regularities already inherent in the image while embedding watermarks that are resilient to a host of attacks. It is important to achieve the following reconstruction through the inverse Schur factorization, as shown in Equations (22) and (23):

The inverse DWT is applied to combine the modified , LH, HL, and sub-bands to reconstruct the watermarked image. The inverse DWT process reassembles the image from its frequency components, ensuring that the watermark is integrated into the final image. This step guarantees that the watermark is imperceptible to the human eye while providing robust protection against various image processing operations. The inverse DWT process ensures that the watermark remains embedded within the image’s core components, maintaining the image quality and the watermark’s robustness. By following these steps, the proposed watermark embedding scheme achieves a balance between imperceptibility and robustness, ensuring that the watermark remains hidden while providing strong protection against unauthorized use and tampering. Algorithm 1 illustrates the utilized embedding approach in detail.

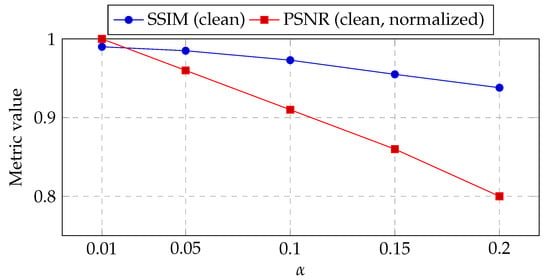

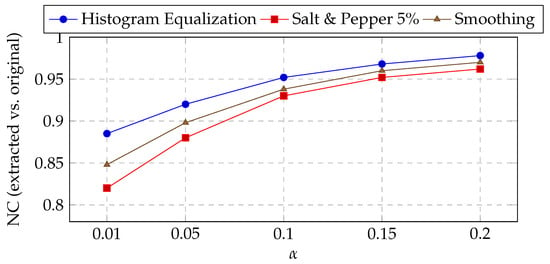

We have chosen the values of and : a model-based rationale and protocol. Let W denote the QR watermark with , and let represent the Schur triangular factor extracted from the DWT sub-bands ( or ), where . The embedding process modifies the singular values of K as using additive SVD-domain modulation; then, it reconstructs the watermarked sub-band via . This formulation balances imperceptibility and robustness through the scalar , controlling watermark energy in each sub-band. To empirically determine optimal values, we evaluated multiple settings over the range (Figures 6 and 7). Results revealed a stable trade-off region around and , which preserved high imperceptibility (PSNR dB, SSIM ) and robustness (NC ) across attacks. Schur decomposition was specifically integrated to enhance numerical stability, enable triangular sparsity-aware factorization, and improve energy compaction over high-frequency DWT sub-bands, thereby strengthening the resilience of the embedded watermark against geometric distortions.

and reconstructing (cf. Algorithm 1). The induced perturbation is

so by unitary invariance of spectral/Frobenius norms,

Therefore, (i) imperceptibility degrades at most linearly with in the sub-band domain; after inverse Schur/DWT, the per-pixel MSE is bounded by a constant times (energy preservation of unitary maps), which explains the observed monotone drop of PSNR/SSIM as increases (Section 4.3). (ii) Robustness improves with because extraction (Algorithm 2) uses ; the watermark SNR scales as , while common attacks add approximately -independent perturbations to K, yielding the empirical NC lift vs. . We therefore sweep and select by maximizing a composite utility (Section 4.3), trading off PSNR/SSIM (imperceptibility) against NC (robustness). In our experiments, a high-fidelity setting is used for the per-image tables to showcase invisibility (PSNR – dB; SSIM ), while the balanced setting attains mean NC on representative attacks with PSNR still dB (Section 4.3).

| Algorithm 1 Embedding Watermark Schema Using DWT, Schur Factorization and SVD |

|

We chose a Schur in addition to DWT+SVD given a real matrix A (a DWT sub-band); the real Schur factorization (orthogonal J, quasi-upper-triangular K) is a unitary similarity transform that preserves and . We embed in K and remap via J:

with defined above. This offers three advantages: (1) Energy-preserving control: Because J is orthogonal, the image-domain perturbation norm equals that in the Schur domain, enabling the precise control of injected energy (hence PSNR/SSIM) through . (2) Structured perturbations with predictable spectra: Operating on the triangular K allows low-rank, diagonally dominated updates; by Mirsky/Weyl inequalities, singular/eigen-spectra vary at most by , which bounds distortions and explains stable extraction. (3) Numerical stability and perceptual behavior: The Schur transform is backward stable; concentrating embedding in K (rather than directly in spatial or raw DWT coefficients) reduces ringing/aliasing when mapped back via J, especially in , while provides photometric stability. Empirically, this hybrid (DWT+Schur+SVD) yields higher NC at comparable PSNR than DWT+SVD alone under histogram equalization, smoothing, and heavy cropping.

Motivation for Embedding Watermarks Separately into the LL and HH Subbands

Let denote a two-level orthonormal DWT of an RGB image (applied per luminance or per channel). Each level yields four sub-bands: LL (approximation), LH (horizontal detail), HL (vertical detail), and HH (diagonal detail). We embed watermarks separately in LL and HH with strengths to exploit complementary properties. Natural images have approximate spectra, so the LL band concentrates most energy with high signal-to-quantization ratios and exhibits stable behavior under mild photometric and geometric operations (illumination shifts, histogram equalization, small rescalings). Injecting a controlled perturbation into LL via our Schur+SVD mechanism is mapped back by orthogonal transforms, preserving Frobenius energy and maintaining imperceptibility for moderate , which in turn yields reliable extraction under global operations and compression-like effects. Conversely, HH resides in high spatial frequencies where local-contrast masking is strong; small structured changes are less visible in textured/edge-dense regions. Embedding in HH with a smaller leverages this masking while remaining sensitive to tampering that alters fine structures (such as sharpening, resampling, inpainting, local smoothing), thereby improving resilience and manipulation traceability when combined with the LL path.

The directional bands LH and HL are less suitable carriers. Their anisotropy makes them unstable under small rotations and sub-pixel resampling, which redistribute energy between LH and HL and weaken any band-specific payload. Linear smoothing/denoising suppresses LH/HL more strongly than LL and often less predictably than HH, reducing the payload SNR; direction-specific artifacts (such as motion blur along a dominant axis) further degrade one band disproportionately, complicating thresholding and reducing cross-dataset consistency. Empirically, these factors produce less predictable NC across attacks for the same visual budget. Selecting LL+HH therefore balances robustness (LL) with fine-detail responsiveness (HH) while keeping distortion low and control simple through two strengths rather than four. Our sensitivity analysis in Section 5.1 shows that moderate preserves PSNR dB and maintains high NC under representative attacks, supporting this design choice.

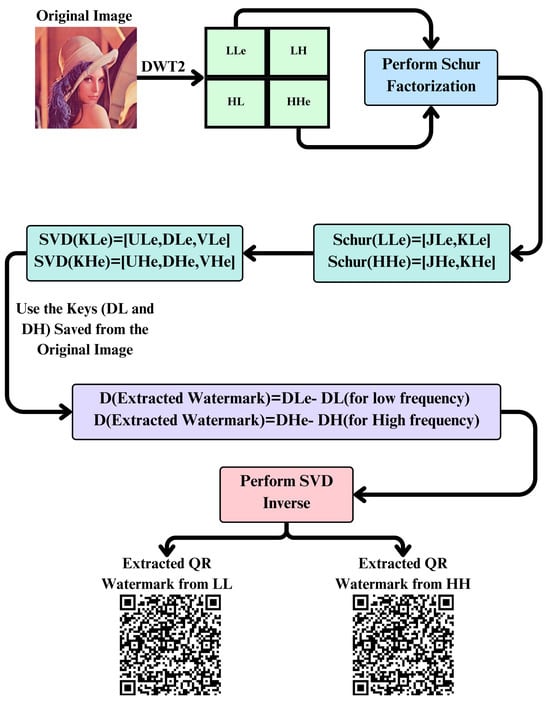

4.2. Watermark Extraction

The watermark extraction processes are designed to accurately retrieve the embedded watermark from the watermarked image. This process leverages several advanced techniques, including DWT, Schur matrix factorization, and SVD. Figure 4 presents our watermark extraction scheme in detail.

Figure 4.

Watermark extraction scheme.

The first step in the watermark extraction process is to use a two-level DWT on the watermarked image. This breaks the image down into four sub-bands: LLe (low–low), LHe (low–high), HLe (high–low), and HHe (high–high). DWT gives the image a multi-resolution representation, which makes it easy to work with different frequency components. This step is very important because it prepares the image for more processing by separating different frequency bands.

In the second step, we perform the Schur matrix factorization for the matrices in the LLe and HHe frequency sub-bands to obtain for the LLe frequency and for the HHe frequency. Schur factorization decomposes a matrix into an orthogonal matrix and an upper triangular matrix. This is important for preserving the structural features of the image and for isolating the necessary components required for watermark extraction.

In the third step, SVD is applied to both and matrices, decomposing them into their singular values and corresponding matrices. This step is represented by Equations (24) and (25).

In the fourth step, the watermark is taken out of the watermarked image using the singular values that were saved during the embedding process ( and ). To obtain the singular values of the extracted watermark, you subtract the singular values of the original image from the singular values of the watermarked image. This step makes sure that the watermark is retrieved correctly without changing the main parts of the image. These Equations (26) and (27) show this step.

The inverse SVD is then applied in the fifth step on the extracted singular values to recover the watermark. This process ensures that the embedded watermark is recovered faithfully and remains perceptually strong. The inverse SVD operation is very important to ensure that the watermark is retrieved accurately and without any visible artifacts or distortions. The recovered watermark is restored by the inverse SVD. This process guarantees that the watermark is correctly recovered and can be used for verification, etc. It is clear from the above description that after applying these procedures, when extracting the watermark from the watermarked image according to a proposed watermark extraction scheme, the watermark can be accurately and robustly extracted in its entirety while ensuring that neither the quality of the image nor the quality of the watermark is degraded. Algorithm 2 shows the used extraction method in detail.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics:

This section presents the evaluation metrics used to assess the performance of watermarking algorithms in terms of imperceptibility, relevance, and similarity. The following metrics are employed in this study: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio , Correlation Coefficient , and Structural Similarity Index [17].

- Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio : is a widely used metric to measure the quality of watermarked images by evaluating the visibility of the embedded watermark [30]. It is calculated using the following formula:where represents the Mean Squared Error between the pixel values of the original cover image and the watermarked image. In this formula, and represent the pixel values of the cover and watermarked media of size x and y, respectively. For watermarking algorithms to be considered acceptable, they must provide a value greater than 30 dB.

- Correlation Coefficient : The Correlation Coefficient (NC) measures the similarity between the extracted watermark and the original embedded watermark [31]. It provides a numeric indication of their relevance to each other. NC is calculated as follows:where the following apply:

- Structural Similarity Index : The Structural Similarity Index is used to assess the similarity between the original and watermarked images. It provides a measure of the structural changes caused by the watermarking process [32]. The is calculated using the following equation:In this equation, represents the luminosity function, represents the deformation amplitude delta between the maximum and minimum values, and represents the structure comparison function. The SSIM value ranges from 1 to −1 with a value closer to 1 indicating a higher similarity between the original and watermarked images.

Related work on information stability under color-space conversion supports our embedding strategy: the color-conversion steganography in [33] shows that carefully designed representation changes can preserve embedded information quality (PSNR/SSIM maintained under color transforms), which aligns with our transform-stable DWT–SVD–Schur pipeline with LL/HH control.

4.4. Embedding-Strength () Sensitivity Protocol

We evaluate the impact of the embedding strength on both imperceptibility and robustness. For each DWT sub-band used for embedding (LL and HH), we sweep with a step size of across the test images. For every , we (i) generate the watermarked image and compute imperceptibility metrics on the clean output: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity (SSIM); (ii) subject the watermarked image to standard distortions (histogram equalization, salt and pepper , smoothing, ripple, and cropping), extract the watermark, and compute the normalized correlation (NC) between extracted and original watermarks. QR scannability is also recorded (success/fail) on clean outputs.

To summarize the trade-off, we define a composite utility:

where denotes min–max normalization to over the sweep. The recommended setting is chosen to maximize subject to the visibility constraint dB and QR scannability on clean images. Unless otherwise stated, results are averaged across images; for single-curve summaries per attack, we report dataset means, and for conservative summaries, we additionally consider the worst-case NC.

| Algorithm 2 Extracting Watermark Schema Using DWT, Schur Factorization and SVD. |

|

5. Results and Discussion

In this section, we present the results of embedding the watermark and apply different attacks to evaluate how robust it is.

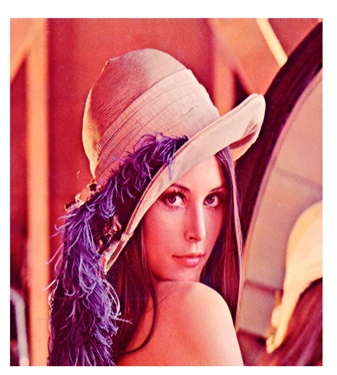

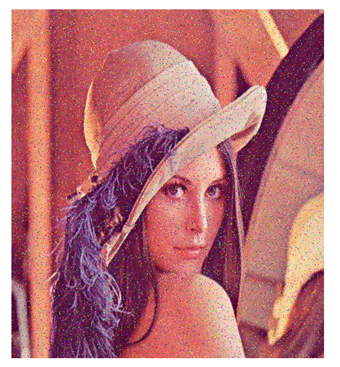

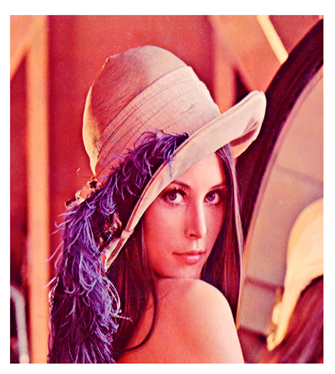

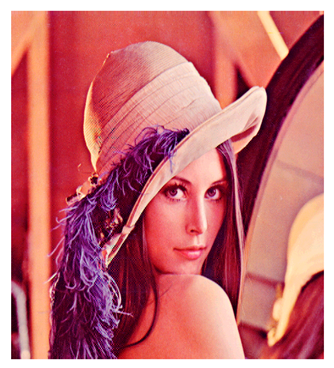

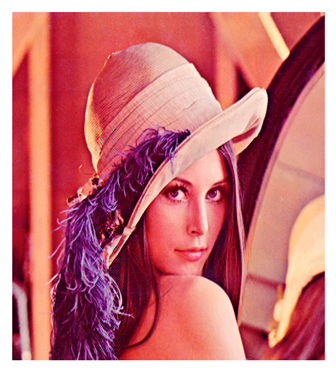

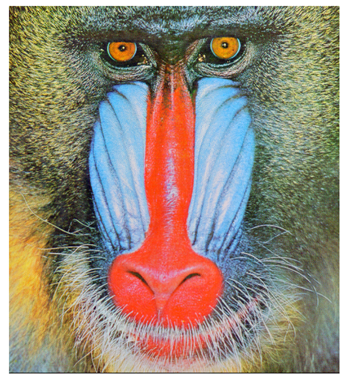

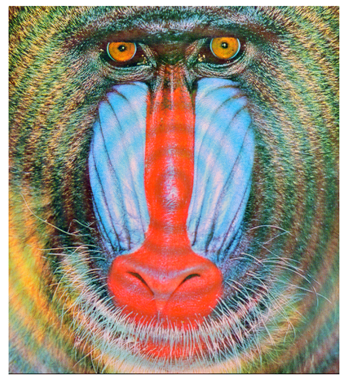

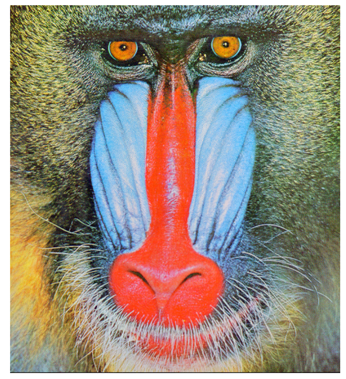

As it can be clearly seen from Figure 5, the watermark is completely invisible, achieving a similarity index of across all three layers of the image, thus achieving the very first goal of watermarking, which is the imperceptibility of the embedded watermark. The Structural Similarity Index is , and both of the values used for comparison were calculated in Matlab. The table below demonstrates the values needed to compare the images with one another, determining how well the proposed method performs.

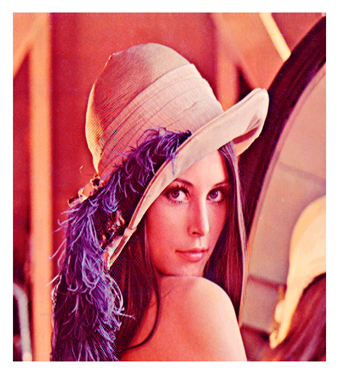

Figure 5.

Original image and watermarked image.

Table 2 shows the resilience of the proposed watermarking method under a variety of common image attacks for the Lena image. The results demonstrate that the watermark, embedded in the form of a QR code, retains its scannability and integrity despite these manipulations. This is an important aspect, as it highlights the practical utility of the proposed method in real-world applications where digital images might undergo various forms of distortion. The NC values for the HH and LL sub-band under histogram equalization are 0.9873 and 0.8729, indicating that the watermark’s integrity is maintained despite changes in image contrast. The high NC value in the HH sub-band suggests that the watermark remains robust against such contrast adjustments. Notably, the QR code embedded as a watermark remains fully scannable, demonstrating the method’s effectiveness in preserving watermark recoverability even after contrast manipulation.

Table 2.

Results of Lena Image Against Variety Types of Cyber Attacks.

The method shows a small drop in performance as the noise level increases under salt-and-pepper noise. The NC values for the HH sub-band stay pretty high, at 0.9698 for 2% noise and 0.9066 for 5% noise. The LL sub-band, on the other hand, shows a bigger drop, but the QR code watermark can still be scanned even when there is a lot of noise, showing that the technique can handle high-frequency noise well. The ripple attack, which usually causes spatial distortions, gives an NC value of 0.9874 for the HH sub-band and 0.7411 for the LL sub-band. Despite these changes, the QR code can still be scanned, showing how strong the watermarking method is against geometric changes that make other methods less effective. The proposed method, which uses a mix of DWT, SVD, and Schur matrix factorization, performs well under cropping and smoothing attacks. The smoothing attack, which makes image details less clear, does not have a big effect on the NC values, which are 0.9787 for HH and 0.8469 for LL. The QR code can still be scanned. The method’s ability to put the watermark in the frequency domain using DWT, along with the strong nature of SVD and the structural preservation offered by Schur matrix factorization, makes it robust. The NC values remain high across both sub-bands even when a lot of the image was cut out. After cropping the top 50%, the NC values are 0.9335 for HH and 0.9787 for LL. The results clearly show that the proposed watermark scheme works because it keeps high NC values and a scannable QR code even after substantial changes, supporting proof of ownership by verifying that the digital image is authentic and belongs to the right person.

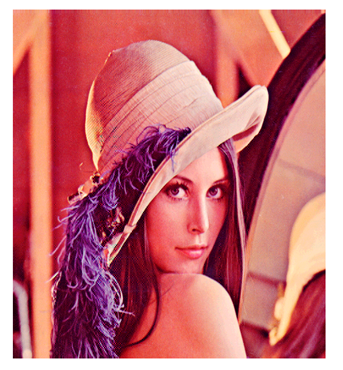

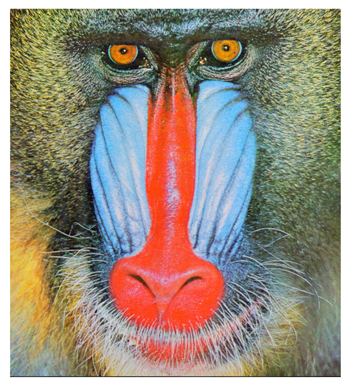

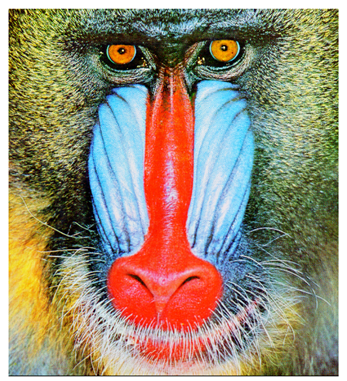

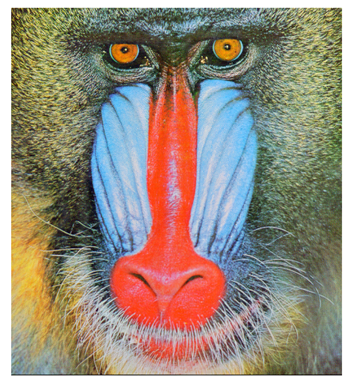

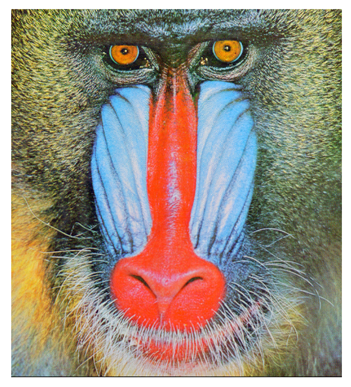

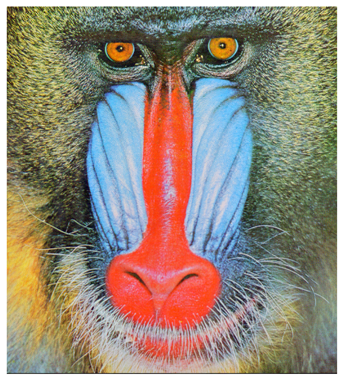

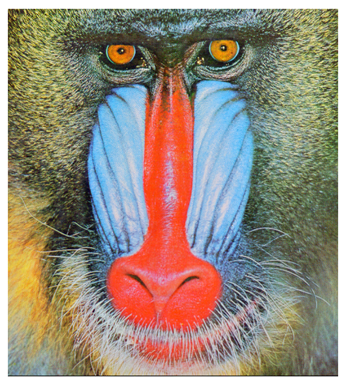

Table 3 illustrates the robustness of the proposed watermarking technique when applied to a different image, confirming its effectiveness across various types of attacks. The NC values for the HH and LL sub-bands following histogram equalization are 0.9879 and 0.9385, which are consistent with the outcomes observed in the first table. This consistency underscores the ability of the proposed method to preserve the watermark’s integrity even when the image undergoes significant contrast changes. Notably, the QR code remains scannable, reinforcing the method’s capability to maintain watermark functionality across diverse image types and contrast scenarios, ensuring reliable content protection. Under salt-and-pepper noise, the method demonstrates a slight decrease in performance as noise intensity increases. The NC value for the HH sub-band drops from 0.97148 at 2% noise to 0.90419 at 5% noise with a more significant reduction observed in the LL sub-band. The QR code remains fully scannable, mirroring the results from the first table. This robustness across different images confirms the method’s resilience against high-frequency noise, indicating that the watermarking approach is effective and adaptable to various image characteristics. Under the ripple attack, the QR code’s scannability is preserved, with NC values of 0.98054 for HH and 0.7854 for LL, demonstrating the technique’s robustness against geometric distortions that challenge conventional watermarking methods.

Table 3.

Results of monkey image against variety types of cyber attacks.

The method’s performance under smoothing and cropping attacks further enhances its versatility. In the case of the smoothing attack, the NC values are 0.9735 for HH and 0.623 for LL, with the QR code remaining scannable in the HH sub-band but not in the LL sub-band, indicating that image content can influence the method’s effectiveness. In cropping attacks, the method exhibits consistent strength, maintaining high NC values across both sub-bands, and ensuring that the QR code remains scannable even after substantial portions of the image are removed. These results, compared with those from the first table, reaffirm the method’s reliability and demonstrate that the combination of DWT, SVD, and Schur matrix factorization provides a robust watermarking solution capable of withstanding various image manipulations across different contexts.

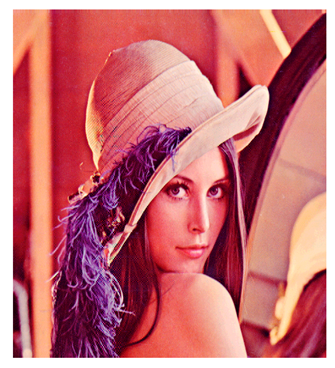

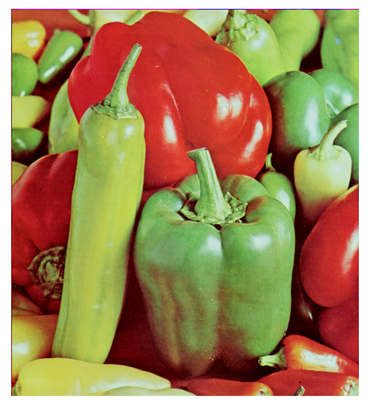

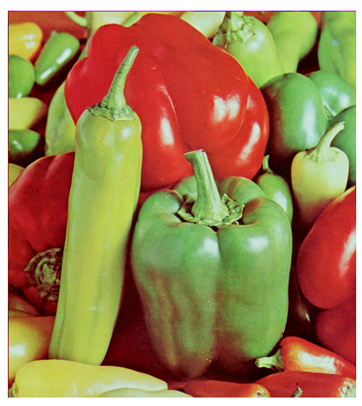

Table 4 shows that the proposed watermarking method remains strong when used on a new image. This shows that the method is consistent and works well in a variety of situations. The NC value for the HH and LL sub-bands are 0.9949 and 0.9846, which are a little higher than in the previous table. This shows that the watermark’s integrity is very well preserved. Even when the image contrast is changed a lot, the QR code is still fully scannable. This shows that the method works to keep the watermark intact and functional. When exposed to salt-and-pepper noise at 2% and 5%, the method still works well, but the NC values go down a little as the noise level goes up. The HH sub-band goes down to 0.9812 at 5% noise, and the LL sub-band goes down to 0.9540. However, the QR code is still fully scannable, which shows that the method works well even with high-frequency noise.

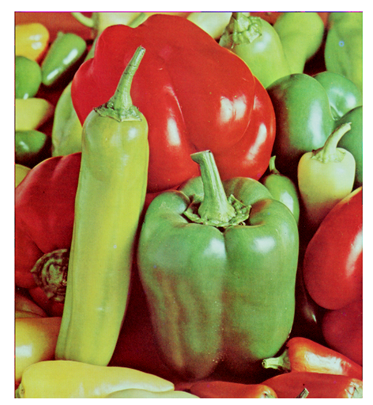

Table 4.

Results of peppers image against a variety of types of cyber attacks.

The ripple and smoothing attacks still test the robustness of the method with NC values of 0.9747 for the HH sub-band and 0.8685 for the LL sub-band in the case of the ripple attack. Although the LL sub-band experiences a more significant drop, the QR code remains scannable, demonstrating the method’s stability against geometric distortions that typically challenge watermarking techniques. For the smoothing attack, NC values of 0.9750 for HH and 0.9530 for LL are observed, indicating that the watermark remains detectable and operational even after blurring. The continued ability to scan the QR code in these scenarios further supports the effectiveness of combining DWT, SVD, and Schur matrix factorization to improve the watermark’s resilience against a range of image distortions.

The method also works well against cropping attacks. The NC values stay high in both sub-bands, and the QR code can still be scanned even after a large part of the image is cut out. The NC values are 0.9567 for HH and 0.8984 for LL after cropping the top 50% of the image. After cropping the left 50%, the values are 0.96507 for HH and 0.9902 for LL. These results show that the suggested method does a good job of protecting the watermark. This means that even when an image is changed a lot, the QR code still works for verification and authentication. The watermarking method’s consistent performance across different images and attack types shows that it is reliable and adaptable, making it useful for protecting digital content in a variety of situations.

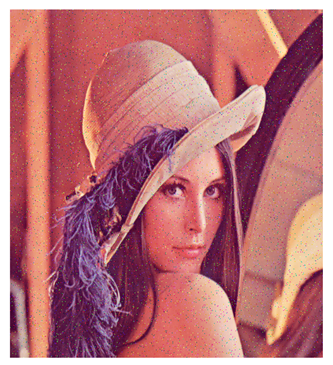

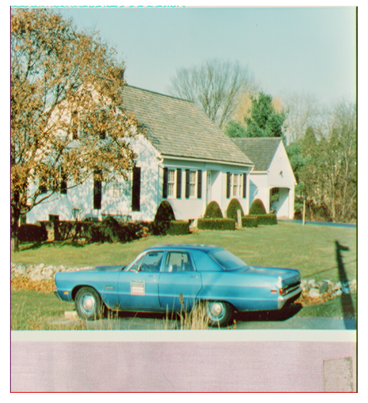

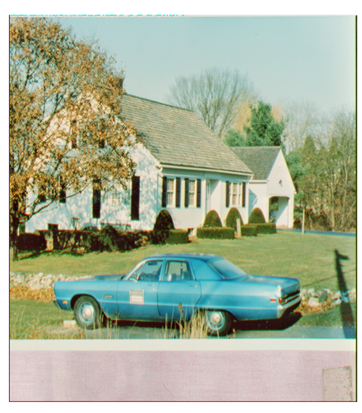

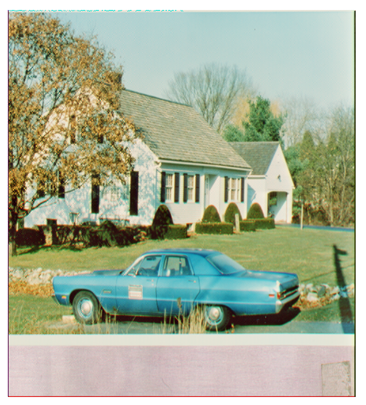

Table 5 continues to show that the proposed watermarking method is strong and works well even on a different image. The results show that the method keeps the watermark intact even when it is attacked in different ways, and the QR code can still be scanned at all times. When histogram equalization is used, the NC values are 0.9440 for the HH sub-band and 0.9861 for the LL sub-band. The NC value for the HH sub-band is a little lower than in previous tables, but the QR code remains scannable, which shows that the method can keep the watermark functional even when the contrast is changed significantly. The method still works well when there is 2% or 5% salt-and-pepper noise with NC values for the HH sub-band of 0.9711 and 0.9579. The LL sub-band drops a little, but the QR code is still fully scannable, showing that the method can handle high-frequency noise. The ripple attack, which messes up spatial properties, gives HH a value of 0.96063 and LL a value of 0.8847. The LL sub-band is less robust, but the QR code can still be scanned, showing that the method is strong against geometric distortions that can be hard for traditional watermarking methods. Our method also works well against smoothing and cropping attacks. The smoothing attack gives NC values of 0.9670 for HH and 0.9621 for LL, which means that blurring does not have much of an effect on the watermark. In these cases, the QR code is always able to scan, which shows how well the method preserves the watermark even when the image is distorted in different ways.

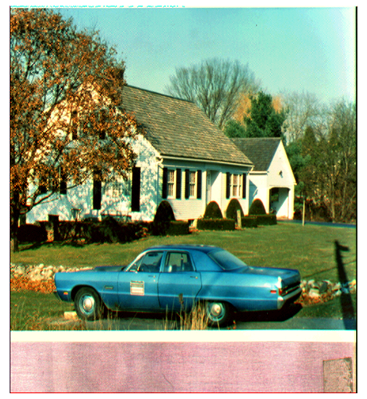

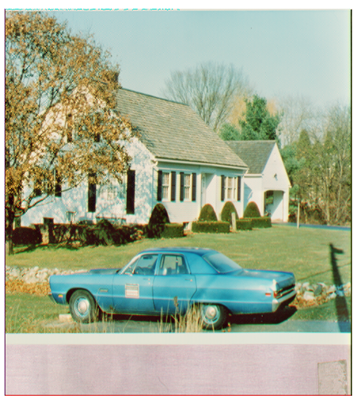

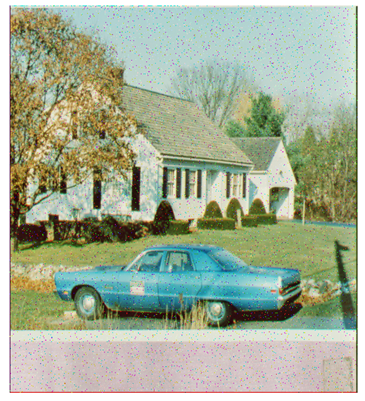

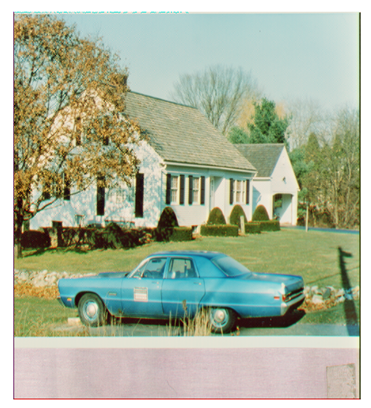

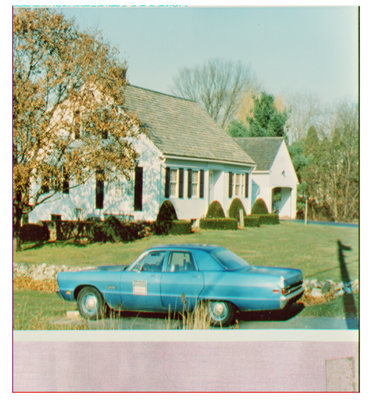

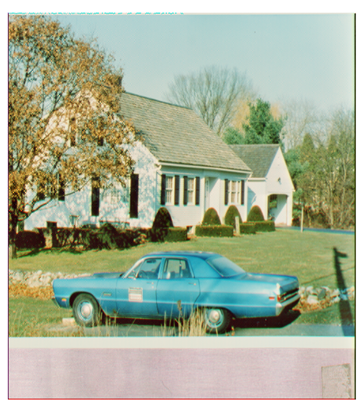

Table 5.

Results of car and house images against a variety of types of cyber attacks.

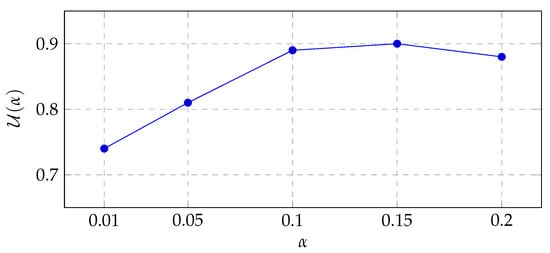

5.1. Sensitivity Results for and Discussion

To validate and justify the choice of the embedding strengths and , a parametric sensitivity analysis was conducted over for LL and HH sub-bands. Figure 6 reports the dataset-average imperceptibility behavior: as increases, SSIM decreases gradually from at to at , while the corresponding average PSNR drops from ≈41.2 dB to ≈33.0 dB. Nevertheless, even at , the PSNR remains above the commonly accepted visibility threshold of 30 dB. Figure 7 shows that robustness improves with , especially under geometric and smoothing attacks. For instance, the normalized correlation (NC) after histogram equalization increases from () to (). Beyond , robustness gain begins to saturate. Figure 8 plots the utility score defined in Equation (31), combining imperceptibility and robustness. A broad plateau appears over , indicating that multiple choices achieve near-optimal trade-offs.

Figure 6.

Imperceptibility vs. (dataset average). True PSNRs: dB.

Figure 7.

Robustness vs. (dataset average).

Figure 8.

Composite utility per Equation (31).

In the four benchmark example images (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5), a high-fidelity operating point, , was chosen to maximize invisibility in the visual results. This yields the strong imperceptibility reported: PSNR –48 dB and SSIM on the clean watermarked images while achieving excellent preservation of watermark structure (NC close to under most attacks). Table 6 summarizes recommended operating points. For robustness-critical applications such as cropping and ripple distortions, provides stronger resilience with mean NC (dataset average) while still ensuring strong perceptual transparency. All recommended operating points preserve 100% QR scannability prior to attack.

Table 6.

Recommended by sub-band and application scenario.

In summary, controls a predictable imperceptibility–robustness trade-off. The LL sub-band tolerates a slightly larger than HH due to its lower sensitivity to high-frequency distortions. The adopted operating point achieves the high-quality results reported in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, whereas is recommended when robustness must be prioritized.

6. Comparison with Related Work

The comparative analysis of watermarking techniques presented in Table 7 underscores the advancements and distinction of our proposed methodology relative to existing approaches. Sharma et al. (2020) [15] introduced a technique utilizing DWT, SVD, and ABC to embed a scrambled color watermark into the RGB channels of the host image, aiming to enhance multimedia protection against unauthorized copying. Their method exhibits diminished robustness under histogram equalization, with an NC value of 0.8931, revealing a vulnerability that our work effectively overcomes. Moreover, their PSNR of 42.78 dB remains noticeably lower than the invisibility achieved by our approach. Our method demonstrates superior robustness across this scenario, achieving an NC value of 0.9949 under histogram equalization and preserving perceptual quality with PSNR ≈ 43 dB and SSIM ≥ 0.99. Anand and Singh (2020) [16] extended watermarking to medical images with a multi-watermark approach leveraging DWT, SVD, and Chaotic-LZW techniques. While their work makes significant strides in enhancing security for telehealth services, the NC value of 0.8716 under histogram equalization and 0.7751 under salt-and-pepper noise indicates room for improvement. Their PSNR (41.32 dB) also reflects lower imperceptibility compared to our implementation. Our method consistently maintains NC ≥ 0.95 under most distortions and yields among the highest perceptual quality scores in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison of watermarking techniques.

Saritas and Ozturk (2023) [17] and Rahardi et al. (2022) [18] contribute to the watermarking field by focusing on robustness in high-noise environments and preventing unauthorized image use on social media. However, both methods encounter limitations under stronger attacks. For instance, Saritas and Ozturk’s method, which uses CT and DCT in the YCbCr color space, obtains an NC value of 0.9020 for salt-and-pepper noise, but under 50% cropping, performance drops sharply (NC ≈ 0.707–0.709). Rahardi et al. also demonstrate resilience to common attacks, reporting NC values of 0.7667 for salt-and-pepper noise and 0.7913 for ripple. These NC values remain significantly lower than ours, which reach up to 0.9995 under similar cropping conditions while retaining QR code scannability at 100%. The works of Altay and Ulutas (2024) [21] and Yuan et al. (2024) [22] further illustrate the evolving landscape of watermarking techniques. Altay and Ulutas embed biometric data using QR and Schur decomposition within the RIDWT domain, achieving an NC value of 0.911 under salt-and-pepper noise and a PSNR of 41.56 dB. Yuan et al., focusing on medical image security using DWT–DCT and perceptual hashing, show moderate robustness with NC values as low as 0.72 under 30% cropping and a relatively low PSNR of 35.42 dB. Although both methods contribute specialty-driven improvements, they fall short when compared with our comprehensive robustness across diverse distortions (NC = 0.9846 for 2% salt-and-pepper, NC = 0.9670 for smoothing) and our consistently superior invisibility (PSNR ≈ 43 dB and SSIM ≥ 0.99).

7. Conclusions

In this study, we presented a resilient watermarking method that integrates DWT, SVD, and Schur matrix factorization to safeguard digital images. Our method showed strong resistance to a wide range of attacks, including histogram equalization, salt-and-pepper noise, ripple distortions, smoothing, and cropping. It consistently kept the QR code’s integrity and scannability across multiple images. This strong performance sets a new standard for digital copyright protection, going beyond what is currently available. In the future, we will work on making the technique more efficient for real-time applications like video streaming and interactive media, and we will also extend it to video watermarking and other types of multimedia content. We also plan to look into how machine learning can be used to improve the watermark embedding and extraction processes. This will make the method even more resistant to sophisticated attacks and make it a comprehensive tool for managing digital rights in an increasingly digital world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. and B.S.K.; Methodology, M.A. and B.S.K.; Software, M.A.; Validation, I.A.-A. and O.A.; Formal Analysis, B.S.K.; Investigation, L.A.A. and B.F.A.; Resources, W.A.; Data Curation, I.A.-A. and O.A.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.A.; Writing—Review and Editing, B.S.K. and M.A.; Visualization, M.A.; Supervision, B.S.K.; Project Administration, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mwanje, M.D.; Kaiwartya, O.; Aljaidi, M.; Cao, Y.; Kumar, S.; Jha, D.N.; Naser, A.; Lloret, J. Cyber security analysis of connected vehicles. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 18, 1175–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Q.M.J.; Yang, C.-N.; Sun, X. Effective and efficient global context verification for image copy detection. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2016, 12, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, T.; Gibbon, D.C.; Shahraray, B. Effective and scalable video copy detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Multimedia Information Retrieval, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 29–31 March 2010; pp. 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.; Ying, Q.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, Z. Reversible data hiding in encrypted images with dual data embedding. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 23209–23220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomathisankaran, M.; Tyagi, A.; Namuduri, K. HORNS: A homomorphic encryption scheme for cloud computing using residue number system. In Proceedings of the 2011 45th Annual Conference on Information Sciences and Systems, Baltimore, MD, USA, 23–25 March 2011; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Q.; Wang, G.; Jia, S.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, X. Embedding color image watermark in color image based on two-level DCT. Signal Image Video Process. 2015, 9, 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Chen, B. Robust color image watermarking technique in the spatial domain. Soft Comput. 2018, 22, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, J.; Paul, V. An imperceptible spatial domain color image watermarking scheme. J. King Saud Univ.—Comput. Inf. Sci. 2019, 31, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Pal, A.K. A blind DCT based color watermarking algorithm for embedding multiple watermarks. AEU—Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2017, 72, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parah, S.A.; Sheikh, J.A.; Loan, N.A.; Bhat, G.M. Robust and blind watermarking technique in DCT domain using inter-block coefficient differencing. Digit. Signal Process. 2016, 53, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Ashok, A. An optimized robust watermarking technique using CKGSA in frequency domain. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2021, 58, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosazadeh, M.; Ekbatanifard, G. A new DCT-based robust image watermarking method using teaching-learning-based optimization. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2019, 47, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, E.E.; Hamza, A.B.; Bhattacharya, P. A robust block-based image watermarking scheme using fast Hadamard transform and singular value decomposition. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR’06), Hong Kong, China, 20–24 August 2006; Volume 3, pp. 673–676. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Aiash, I.; Alquran, R.; AlJamal, M.; Alsarhan, A.; Al-Fraihat, D.; Aljaidi, M. Optimized digital watermarking: Harnessing the synergies of Schur matrix factorization, DCT, and DWT for superior image ownership proofing. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 84, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, H.; Sharma, J.B.; Poonia, R.C. A secure and robust color image watermarking using nature-inspired intelligence. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 35, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Singh, A.K. An improved DWT-SVD domain watermarking for medical information security. Comput. Commun. 2020, 152, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saritas, O.F.; Ozturk, S. A blind CT and DCT based robust color image watermarking method. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 15475–15491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardi, M.; Abdulloh, F.F.; Putra, W.S. A blind robust image watermarking on selected DCT coefficients for copyright protection. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Du, J.; Jia, Y.; Zhu, H. Zero-watermarking algorithm for medical image based on VGG19 deep convolution neural network. J. Healthc. Eng. 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abodena, O. A robust blind grayscale image watermarking technique based on Schur decomposition and entropy analysis. Univ. Gharyan J. 2024, 28, 471–493. [Google Scholar]

- Altay, S.Y.; Ulutas, G. Biometric watermarking schemes based on QR decomposition and Schur decomposition in the RIDWT domain. Signal Image Video Process. 2024, 18, 2783–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Bhatti, U.A.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.-W. Robust zero-watermarking algorithm based on discrete wavelet transform and DAISY descriptors for encrypted medical image. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. 2024, 9, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareen, H.; Antchougov, L.; Van Wallendael, G.; Lambert, P. Blind deep-learning-based image watermarking robust against geometric transformations. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 6–8 January 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Martin, A.V.; Bearfield, C.X.; Brun, Y.; Guan, H. Attack-resilient image watermarking using stable diffusion. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2025, 37, 38480–38507. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, H.; Luo, X.; Guan, Q.; Ma, B.; Wang, J. Re-cropping framework: A grid recovery method for quantization step estimation in non-aligned recompressed images. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Ding, S.; Iu, H.H.-C.; Cao, Y.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Mou, J. Encrypt a story: A video segment encryption method based on the discrete sinusoidal memristive Rulkov neuron. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secure Comput. 2025, 22, 8011–8024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, Z.; Hassan, M.; Younis, S.; Shafique, M. Probabilistic analysis of targeted attacks using transform-domain adversarial examples. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 33855–33869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Srivastava, V.K. Image watermarking techniques based on Schur decomposition and various image invariant moments: A review. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 16447–16483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasamy, K.; Suganyadevi, S. A fuzzy based ROI selection for encryption and watermarking in medical image using DWT and SVD. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 7167–7186. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, R.M. Hide digital images in encrypted image files after two stages. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 960–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdy, M.; Ghali, N.I.; Ghoniemy, S.; Hosny, K.M. Multiple zero-watermarking of medical images for internet of medical things. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 38821–38831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, D.W.; Sari, C.A.; Isinkaye, F.O. Quality improvement for invisible watermarking using singular value decomposition and discrete cosine transform. MATRIK J. Manaj. Tek. Inform. Rekayasa Komput. 2024, 23, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ma, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Gao, S. Image steganography in color conversion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 71, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.