Development of Starter Inoculum for Controlled Arabica Coffee Fermentation Using Coffee By-Products (Pulp and Mucilage Broth), Yeast, and Lactic Acid Bacteria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Coffee Variety

2.2. Starter Cultures

2.3. Inhibition Test for Pathogenic Bacteria

2.4. Resistance Test of Lactic Acid Bacteria at Different Temperatures

2.5. Inoculum Preparation

2.6. pH

2.7. Soluble Solids

2.8. Acidity

2.9. Viability

3. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

3.1. Model Quality

3.2. Optimization

3.3. Experimental Validation

3.4. Coffee Fermentation

3.5. Microbiological Analysis

3.6. Ochratoxin A

3.7. Sensory Evaluation

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Inhibition of Pathogenic Bacteria and Temperature Resistance

4.1.1. Inhibition Test for Pathogenic Bacteria

4.1.2. Resistance to Different Temperatures

4.2. Optimization of the Inoculum Using Statistical Methods

4.2.1. pH and Acidity

4.2.2. Soluble Solids (°Brix)

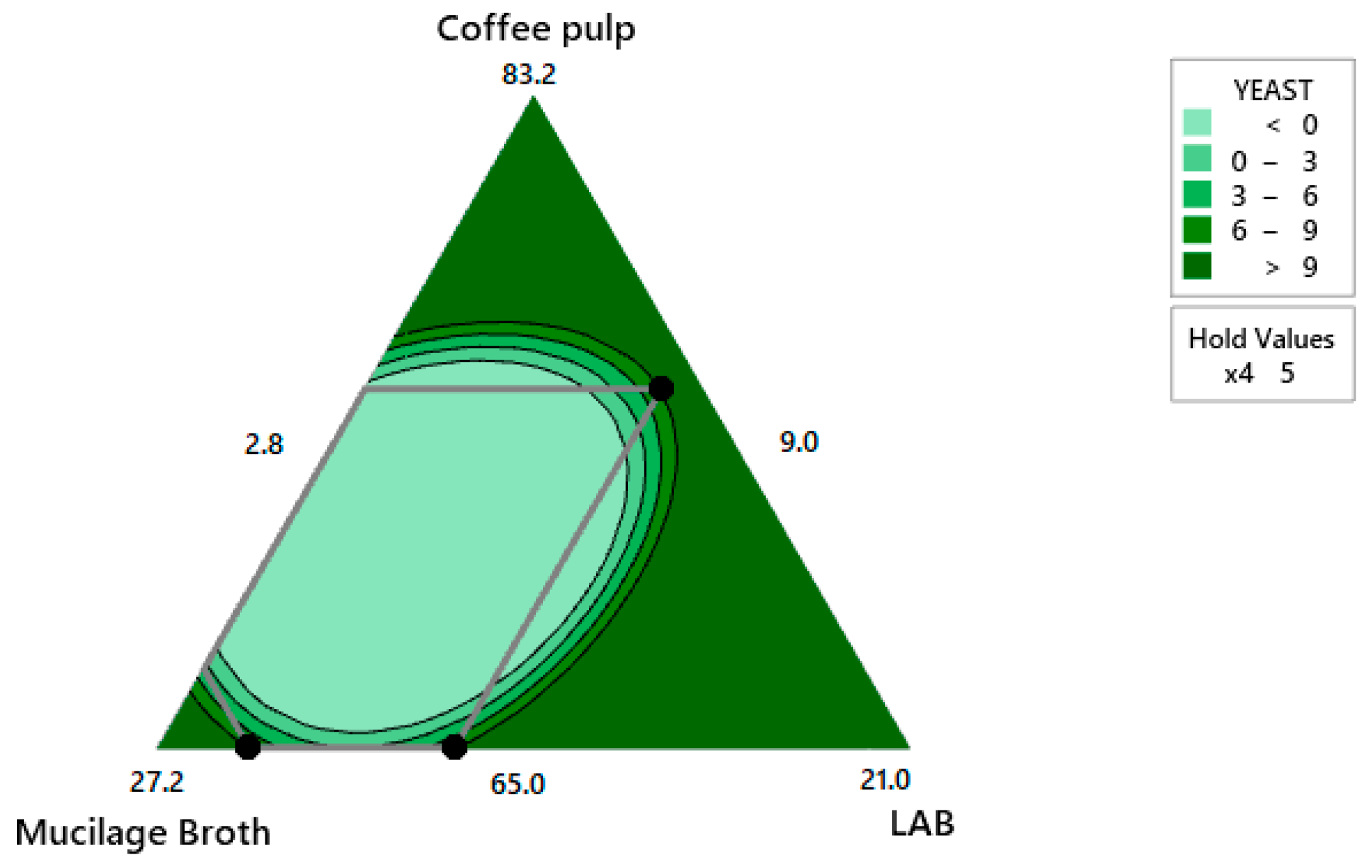

4.2.3. Microbial Growth in the Inoculum

4.2.4. Statistical Analysis

4.2.5. Optimization

4.3. Application of the Optimized Inoculum in Controlled Coffee Fermentation

4.3.1. Coffee Fermentation Process

4.3.2. pH and Acidity

4.3.3. Soluble Solids (°Brix)

4.3.4. Microbial Growth during Fermentation Process

4.3.5. Microbiological Analysis

4.3.6. Ochratoxin A

4.3.7. Sensory Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation. FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/markets-and-trade/commodities/coffee/en/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- ICO. Coffee Market Report; International Coffee Organization: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://icocoffee.org/documents/cy2023-24/Coffee_Report_and_Outlook_December_2023_ICO.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Giraldo, L.H. Estrategias Para el Aprovechamiento de la Pulpa de Café en las Fincas Cafeteras del Municipio de Andes, Antioquia; Tecnológico de Antioquia Institución Universitaria: Medellín, Colombia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro-Cabrales, N.; Contreras-Oliva, A.; González-Ríos, O.; Rosas-Mendoza, E.S.; Morales-Ramos, V. Chemical and nutritional characterizationof coffee pulp (Coffea arabica L.). Agroproductividad 2018, 11, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruyn, F.; Zhang, S.J.; Pothakos, V.; Torres, J.; Lambot, C.; Moroni, A.V.; Callanan, M.; Sybesma, W.; Weckx, S.; De Vuyst, L. Exploring the Impacts of Postharvest Processing on the Microbiota and Metabolite Profiles during Green Coffee Bean Production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e02398-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haile, M.; Kang, W.H. The Role of Microbes in Coffee Fermentation and Their Impact on Coffee Quality. J. Food Qual. 2019, 2019, 4836709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressani, A.P.P.; Martinez, S.J.; Evangelista, S.R.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Characteristics of fermented coffee inoculated with yeast starter cultures using different inoculation methods. LWT 2018, 92, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Mota, M.C.B.; Batista, N.N.; Rabelo, M.H.S.; Ribeiro, D.E.; Borém, F.M.; Schwan, R.F. Influence of fermentation conditions on the sensorial quality of coffee inoculated with yeast. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Melo Pereira, G.V.; Neto, E.; Soccol, V.T.; Medeiros, A.B.P.; Woiciechowski, A.L.; Soccol, C.R. Conducting starter culture-controlled fermentations of coffee beans during on-farm wet processing: Growth, metabolic analyses and sensorial effects. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, M.; Kang, W.H. Isolation, Identification, and Characterization of Pectinolytic Yeasts for Starter Culture in Coffee Fermentation. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo Pereira, G.V.; da Silva Vale, A.; de Carvalho Neto, D.P.; Muynarsk, E.S.; Soccol, V.T.; Soccol, C.R. Lactic acid bacteria: What coffee industry should know? Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassimiro, D.M.d.J.; Batista, N.N.; Fonseca, H.C.; Naves, J.A.O.; Coelho, J.M.; Bernardes, P.C.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Wet fermentation of Coffea canephora by lactic acid bacteria and yeasts using the self-induced anaerobic fermentation (SIAF) method enhances the coffee quality. Food Microbiol. 2023, 110, 104161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUCAST, EUCAST: Método de Difusion con Discos Para el Estudio de la Sensibilidad de los Antimicrobianos; European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: Basel, Switzerland, 2020.

- Hernandez, L.L. Proceso de Fermentación Sólida Para la Disminución de Taninos en el Sorgo. Universidad del Valle, Cali. 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10893/15538 (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- NTC 5247; NTC 5247: Determinacion de Acidez Titulable en Café Tostado, en Grano o Molido. ICONTEC: Bogotá, Colombia, 2004.

- Lingle, T.R. The Coffee Cuppeŕs Handbook: Systematic Guide to the Sensory Evaluation of Coffeés Flavor; Specialty Coffee Association of America: Irvine, CA, USA, 2011; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Meilgaard, M.C.; Carr, B.T.; Civille, G.V. Sensory Evaluation Techniques; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E.; Sanchez, K.; Phan, U.X.T.; Miller, R.; Civille, G.V.; Di Donfrancesco, B. Development of a ‘living’ lexicon for descriptive sensory analysis of brewed coffee. J. Sens. Stud. 2016, 31, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzafera, P. Degradation of caffeine by microorganisms and potential use of decaffeinated husk and pulp in animal feeding. Sceintia Agric. 2002, 59, 821–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloo, O.S.; Gemechu, F.G.; Oh, H.-J.; Kilel, E.C.; Chelliah, R.; Gonfa, G.; Oh, D.-H. Harnessing fermentation for sustainable beverage production: A tool for improving the nutritional quality of coffee bean and valorizing coffee byproducts. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 59, 103263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, V.K.; Han, J.-H.; Rather, I.A.; Park, C.; Lim, J.; Paek, W.K.; Lee, J.S.; Yoon, J.-I.; Park, Y.-H. Characterization and Antibacterial Potential of Lactic Acid Bacterium Pediococcus pentosaceus 4I1 Isolated from Freshwater Fish Zacco koreanus. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalié, D.K.D.; Deschamps, A.M.; Richard-Forget, F. Lactic acid bacteria—Potential for control of mould growth and mycotoxins: A review. Food Control 2010, 21, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, K.; Liu, M.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, T.; Fan, M.; Wei, X. Antibacterial activity of selenium-enriched lactic acid bacteria against common food-borne pathogens in vitro. J. Dairy. Sci. 2018, 101, 1930–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shori, A.B.; Baba, A.S.; Muniandy, P. Potential Health-Promoting Effects of Probiotics in Dairy Beverages. In Value-Added Ingredients and Enrichments of Beverages; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 173–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Munekata, P.E.; Dominguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Franco, D. Main Groups of Microorganisms of Relevance for Food Safety and Stability. In Innovative Technologies for Food Preservation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 53–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, P.F.; Pinheiro, C.A.; Osório, V.M.; Pereira, L.L. Chemical Constituents of Coffee. In Quality Determinants in Coffee Production; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 209–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, N.; Wohlt, D.; Winter, A.R.; Ortner, E. Aroma-Active Compounds in Robusta Coffee Pulp Puree—Evaluation of Physicochemical and Sensory Properties. Molecules 2021, 26, 3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrantes, E.M.; Vargas, Y.C. Aprovechamiento de la Pulpa Residual del Proceso Agroindustrial del Café (Coffee arabica) Para el Desarrollo de Productos Alimenticios en Cooperativas Caficultoras; Universidad Técnica Nacional: Atenas, Costa Rica, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, H.M. Análisis de la Producción del Hongo COMESTIBLE pleurotus Ostreatus Obtenida a Partir de los Subproductos de la Etapa de Despulpado del Café; Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina: Lima, Perú, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, L.L. Effect of solid state fermentation with Rhizopus oryzae on biochemical and structural characteristics of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). Int. J. Food Ferment. Technol. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, M.A.P. Evaluación de las Propiedades de Tres Variedades de Pulpa de Café Para la Producción de una Bebida Tipo té. Fundación Universidad de América: Bogotá, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Onyeaka, H.N.; Nwabor, O.F. Lactic acid bacteria and bacteriocins as biopreservatives. In Food Preservation and Safety of Natural Products; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero, G.I.P. Factores, Procesos y Controles en la Fermentación del Café. Cenicafé 2012, 1–12. Available online: https://biblioteca.cenicafe.org/bitstream/10778/327/1/avt0422.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- da Silva, B.L.; Pereira, P.V.; Bertoli, L.D.; Silveira, D.L.; Batista, N.N.; Pinheiro, P.F.; Carneiro, J.d.S.; Schwan, R.F.; Silva, S.d.A.; Coelho, J.M.; et al. Fermentation of Coffea canephora inoculated with yeasts: Microbiological, chemical, and sensory characteristics. Food Microbiol. 2021, 98, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesulu-Dahunsi, A.T.; Dahunsi, S.O.; Olayanju, A. Synergistic microbial interactions between lactic acid bacteria and yeasts during production of Nigerian indigenous fermented foods and beverages. Food Control 2020, 110, 106963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, H.; Guilloux-Benatier, M. Yeast autolysis in sparkling wine—A review. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2006, 12, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreson, M.; Kazantseva, J.; Kuldjärv, R.; Malv, E.; Vaikma, H.; Kaleda, A.; Kütt, M.-L.; Vilu, R. Characterisation of chemical, microbial and sensory profiles of commercial kombuchas. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 373, 109715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Melo Pereira, G.V.; Soccol, V.T.; Pandey, A.; Medeiros, A.B.P.; Lara, J.M.R.A.; Gollo, A.L.; Soccol, C.R. Isolation, selection and evaluation of yeasts for use in fermentation of coffee beans by the wet process. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 188, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Bravo, F.; González-Lutz, M.I. Análisis de métodos estadísticos para evaluar el desempeño de modelos de simulación en cultivos hortícolas. Agron. Mesoam. 2019, 30, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.J.; Rabelo, M.H.S.; Bressani, A.P.P.; Da Mota, M.C.B.; Borém, F.M.; Schwan, R.F. Novel stainless steel tanks enhances coffee fermentation quality. Food Res. Int. 2021, 139, 109921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho Neto, D.P.; De Melo Pereira, G.V.; Finco, A.M.O.; Rodrigues, C.; De Carvalho, J.C.; Soccol, C.R. Microbiological, physicochemical and sensory studies of coffee beans fermentation conducted in a yeast bioreactor model. Food Biotechnol. 2020, 34, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, S.R.; Miguel, M.G.d.C.P.; Silva, C.F.; Pinheiro, A.C.M.; Schwan, R.F. Microbiological diversity associated with the spontaneous wet method of coffee fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 210, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassimiro, D.M.d.J.; Batista, N.N.; Fonseca, H.C.; Naves, J.A.O.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Coinoculation of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts increases the quality of wet fermented Arabica coffee. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 369, 109627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhalis, H.; Cox, J.; Frank, D.; Zhao, J. Microbiological and biochemical performances of six yeast species as potential starter cultures for wet fermentation of coffee beans. LWT 2021, 137, 110430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, A.-K.; Pleissner, D.; Mehlmann, K.; Schneider, R.; Puerta-Quintero, G.I.; Venus, J. Fermentative utilization of coffee mucilage using Bacillus coagulans and investigation of down-stream processing of fermentation broth for optically pure l(+)-lactic acid production. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 211, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNutt, J.; He, Q. Spent coffee grounds: A review on current utilization. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2019, 71, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battista, F.; Barampouti, E.M.; Mai, S.; Bolzonella, D.; Malamis, D.; Moustakas, K.; Loizidou, M. Added-value molecules recovery and biofuels production from spent coffee grounds. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 110007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, G.; Peng, Y.; Xu, N.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, H.; Liang, H.; Zhan, J.; Huang, W.; You, Y. Mechanisms and effects of non-Saccharomyces yeast fermentation on the aromatic profile of wine. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 124, 105660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, I.; Kumar, P.; Om, H.; Basavaraj, K.; Murthy, P.S. Metabolomics and volatile fingerprint of yeast fermented robusta coffee: A value added coffee. LWT 2022, 154, 112717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.J.C.; Casé, I.N.; Bertarini, P.L.L.; de Oliveira, L.M.; Santos, L.D. Impact of immature coffee fruits and water addition during spontaneous fermentation process: Chemical composition and sensory profile. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 69, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahingsapun, R.; Tantayotai, P.; Panyachanakul, T.; Samosorn, S.; Dolsophon, K.; Jiamjariyatam, R.; Lorliam, W.; Srisuk, N.; Krajangsang, S. Enhancement of Arabica coffee quality with selected potential microbial starter culture under controlled fermentation in wet process. Food Biosci. 2022, 48, 101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.S.; Evangelista, S.R.; da Cruz Pedrozo Miguel, M.G.; van Mullem, J.; Silva, C.F.; Schwan, R.F. Microbiological and chemical-sensory characteristics of three coffee varieties processed by wet fermentation. Ann. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santanatoglia, A.; Angeloni, S.; Caprioli, G.; Fioretti, L.; Ricciutelli, M.; Vittori, S.; Alessandroni, L. Comprehensive investigation of coffee acidity on eight different brewing methods through chemical analyses, sensory evaluation and statistical elaboration. Food Chem. 2024, 454, 139717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, P.P.; Veloso, T.G.R.; de Cássia Soares da Silva, M.; da Luz, J.M.R.; Oliveira, S.F.; Kasuya, M.C.M. Soil Microorganisms and Quality of the Coffee Beverage. In Quality Determinants in Coffee Production; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 101–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhalis, H.; Cox, J.; Zhao, J. Ecological diversity, evolution and metabolism of microbial communities in the wet fermentation of Australian coffee beans. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 321, 108544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmourougane, K. Impact of Natural Fermentation on Physicochemical, Microbiological and Cup Quality Characteristics of Arabica and Robusta Coffee. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 83, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuela-Martínez, A.E.; García-Duque, J.F.; Sanz-Uribe, J.R. Characterization of Fermentations with Controlled Temperature with Three Varieties of Coffee (Coffea arabica L.). Fermentation 2023, 9, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerta, G.I. Calidad del café. Federación Nacional de Cafeteros de Colombia, Manual del cafetero colombiano: Investigación y tecnología para la sostenibilidad de la caficultura 2013, 3, 81–110. Available online: https://biblioteca.cenicafe.org/bitstream/10778/4346/1/cenbook-0026_30.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- Tirado-Kulieva, V.; Quijano-Jara, C.; Avila-George, H.; Castro, W. Predicting the evolution of pH and total soluble solids during coffee fermentation using near-infrared spectroscopy coupled with chemometrics. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhalis, H.; Cox, J.; Zhao, J. Coffee fermentation: Expedition from traditional to controlled process and perspectives for industrialization. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, R.K.C. Caracterización de la Diversidad Microbiana Presente en el Proceso de Fermentación de Coffea arabica L. y su Influencia en la Calidad Sensorial de la Bebida en la Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (SNSM); Universidad del Magdalena: Santa Martha, Colombia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peñuela-Martínez, A.E.; Velasquez-Emiliani, A.V.; Angel, C.A. Microbial Diversity Using a Metataxonomic Approach, Associated with Coffee Fermentation Processes in the Department of Quindío, Colombia. Fermentation 2023, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.; Rendueles, M.; Díaz, M. Liquid-phase food fermentations with microbial consortia involving lactic acid bacteria: A review. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Liu, Z.; Yu, T.; Yan, F. Spent coffee grounds: Present and future of environmentally friendly applications on industries-A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SILVA, C.; BATISTA, L.; ABREU, L.; DIAS, E.; SCHWAN, R. Succession of bacterial and fungal communities during natural coffee (Coffea arabica) fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, D.M.; Pereira, G.V.d.M.; Silva, C.F.; Batista, L.R.; Schwan, R.F. Molecular ecology and polyphasic characterization of the microbiota associated with semi-dry processed coffee (Coffea arabica L.). Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhalis, H.; Cox, J.; Frank, D.; Zhao, J. Microbiological and Chemical Characteristics of Wet Coffee Fermentation Inoculated with Hansinaspora uvarum and Pichia kudriavzevii and Their Impact on Coffee Sensory Quality. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 713969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhalis, H.; Cox, J.; Frank, D.; Zhao, J. The crucial role of yeasts in the wet fermentation of coffee beans and quality. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 333, 108796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwan, R.F.; Fleet, G.H. Cocoa and Coffee Fermentations; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, A.; Onbası, E. Mycotoxins and Food Safety, 1st ed.; IntechOpen Ltd.: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyeye, S.A.O. Fungal mycotoxins in foods: A review. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2, 1213127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Algeri, T.A.; Castagnaro, D.; de Bortoli, K.; de Souza, C.; Drunkler, D.A.; Badiale-Furlong, E. Mycotoxins in Bovine Milk and Dairy Products: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, R544–R552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickova, D.; Ostry, V.; Malir, J.; Toman, J.; Malir, F. A Review on Mycotoxins and Microfungi in Spices in the Light of the Last Five Years. Toxins 2020, 12, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepa, N.; Sreenivasa, M.Y. Sustainable approaches for biological control of mycotoxigenic fungi and mycotoxins in cereals. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmudiono, T.; Fakhri, Y.; Sarafraz, M.; Mehri, F.; Hoseinvandtabar, S.; Khaneghah, A.M. The prevalence and concentration of ochratoxin A in green coffee-based products: A worldwide systematic review, meta-analysis, and health risk assessment. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 122, 105423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaneghah, A.M.; Fakhri, Y.; Abdi, L.; Coppa, C.F.S.C.; Franco, L.T.; de Oliveira, C.A.F. The concentration and prevalence of ochratoxin A in coffee and coffee-based products: A global systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Fungal Biol. 2019, 123, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, E.S.; Triyadi, R.; Khusna, R.N.B.; Djaafar, T.F.; Utami, T.; Marwati, T.; Hatmi, R.U. Indigenous Yeast, Lactic Acid Bacteria, and Acetic Acid Bacteria from Cocoa Bean Fermentation in Indonesia Can Inhibit Fungal-Growth-Producing Mycotoxins. Fermentation 2021, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panebianco, F.; Caridi, A. New insights into the antifungal activity of lactic acid bacteria isolated from different food matrices. Grasas y Aceites 2021, 72, e400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiocchetti, G.M.; Jadán-Piedra, C.; Monedero, V.; Zúñiga, M.; Vélez, D.; Devesa, V. Use of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts to reduce exposure to chemical food contaminants and toxicity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1534–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.L.; Strub, C.; Fontana, A.; Verheecke-Vaessen, C.; Durand, N.; Beugré, C.; Guehi, T.; Medina, A.; Schorr-Galindo, S. Biocontrol activities of yeasts or lactic acid bacteria isolated from Robusta coffee against Aspergillus carbonarius growth and ochratoxin A production in vitro. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 415, 110638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borém, F.M.; Rabelo, M.H.S.; Alves, A.P.d.C.; Santos, C.M.; Pieroni, R.S.; Nakajima, M.; Sugino, R. Fermentation of coffee fruit with sequential inoculation of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Effect on sensory attributes and chemical composition of the beans. Food Chem. 2024, 446, 138820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.; Adhikari, K.; Choi, K.S.; Lee, J. Analysis of Caffeine, Chlorogenic Acid, Trigonelline, and Volatile Compounds in Cold Brew Coffee Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography and Solid-Phase Microextraction—Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Foods 2020, 9, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Vale, A.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; de Carvalho Neto, D.P.; Rodrigues, C.; Pagnoncelli, M.G.B.; Soccol, C.R. Effect of Co-Inoculation with Pichia fermentans and Pediococcus acidilactici on Metabolite Produced During Fermentation and Volatile Composition of Coffee Beans. Fermentation 2019, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Coffee Pulp (%) | Mucilage Broth (%) | LAB (%) | Yeast (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 75 | 20 | 0 | 5 |

| 3 | 65 | 25 | 10 | 0 |

| 4 | 65 | 20 | 10 | 5 |

| 5 | 75 | 15 | 10 | 0 |

| 6 | 70 | 25 | 0 | 5 |

| 7 | 65 | 25 | 5 | 5 |

| 8 | 75 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| 9 | 70.6 | 20.6 | 5.6 | 3.1 |

| 10 | 72.8 | 22.8 | 2.8 | 1.6 |

| 11 | 72.8 | 20.3 | 2.8 | 4.1 |

| 12 | 67.8 | 22.8 | 7.8 | 1.6 |

| 13 | 67.8 | 20.3 | 7.8 | 4.1 |

| 14 | 72.8 | 17.8 | 7.8 | 1.6 |

| 15 | 70.3 | 22.8 | 2.8 | 4.1 |

| 16 | 67.8 | 22.8 | 5.3 | 4.1 |

| 17 | 72.8 | 15.3 | 7.8 | 4.1 |

| 18 | 70.6 | 20.6 | 5.6 | 3.1 |

| 19 | 70.6 | 20.6 | 5.6 | 3.1 |

| 20 | 70.6 | 20.6 | 5.6 | 3.1 |

| 21 | 70.6 | 20.6 | 5.6 | 3.1 |

| Pathogenic Bacteria | Inhibition Halos (mm) |

|---|---|

| Proteus ssp. | 14.2 ± 0.028 |

| Escherichia coli | 6.2 ± 0.056 |

| Salmonella | 12.4 ± 0.042 |

| Pseudomonas | 7.0 ± 0.021 |

| Klebsiella | 12.5 ± 0.14 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 7.0 ± 0.07 |

| Temperature (°C) | 10−2 CFUs | 10−3 CFUs | 10−4 CFUs | 10−5 CFUs | 10−6 CFUs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | >300 | >300 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 | >300 | >300 | >300 | 3 | 1 |

| 35 | >300 | >300 | >300 | 20 | 10 |

| Treatment | Components | Viability (Log CFUs/g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | Yeast | LAB | |

| 1 | 75 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 0 |

| 2 | 75 | 20 | 0 | 5 | 8.45 | 0 |

| 3 | 65 | 25 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 5.94 |

| 4 | 65 | 20 | 10 | 5 | 8.88 | 8.66 |

| 5 | 75 | 15 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 5.38 |

| 6 | 70 | 25 | 0 | 5 | 8.29 | 0 |

| 7 | 65 | 25 | 5 | 5 | 9.09 | 8.69 |

| 8 | 75 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 9.35 | 8.92 |

| 9 | 70.6 | 20.6 | 5.6 | 3.1 | 8.41 | 8.68 |

| 10 | 72.8 | 22.8 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 8.29 | 8.5 |

| 11 | 72.8 | 20.3 | 2.8 | 4.1 | 8.76 | 8.69 |

| 12 | 67.8 | 22.8 | 7.8 | 1.6 | 9.13 | 8.49 |

| 13 | 67.8 | 20.3 | 7.8 | 4.1 | 8.94 | 8.83 |

| 14 | 72.8 | 17.8 | 7.8 | 1.6 | 8.18 | 7.96 |

| 15 | 70.3 | 22.8 | 2.8 | 4.1 | 8.77 | 8.84 |

| 16 | 67.8 | 22.8 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 8.56 | 8.28 |

| 17 | 72.8 | 15.3 | 7.8 | 4.1 | 8.63 | 8.61 |

| 18 | 70.6 | 20.6 | 5.6 | 3.1 | 8.84 | 8.64 |

| 19 | 70.6 | 20.6 | 5.6 | 3.1 | 8.43 | 8.3 |

| 20 | 70.6 | 20.6 | 5.6 | 3.1 | 7.92 | 8.22 |

| 21 | 70.6 | 20.6 | 5.6 | 3.1 | 8.55 | 8.18 |

| Term | p-Value | Regression Coefficients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAB | Yeast | LAB Viability | Yeast Viability | |

| X1 | - | - | 253.9 | 664 |

| X2 | - | - | 1698 | 4839 |

| X3 | - | - | 6135 | 16,840 |

| X4 | - | - | −16,973 | −48,049 |

| X1xX2 | 0.005 | 0.002 | −3215 | −9047 |

| X1xX3 | 0.007 | 0.003 | −7974 | −22,188 |

| X1xX4 | 0.021 | 0.008 | 16,420 | 47,213 |

| X2xX3 | 0.278 | 0.08 | −6384 | −26,004 |

| X2xX4 | 0.024 | 0.011 | 19,543 | 53,682 |

| X3xX4 | 0.081 | 0.163 | −35,215 | −59,687 |

| X1xX2xX3 | 0.984 | 0.509 | 197 | 14,590 |

| X1xX3xX4 | 0.058 | 0.085 | 56,096 | 110,912 |

| X1xX2xX3Xx4 | 0.055 | 0.06 | 100,341 | 220,587 |

| Model | Special Cubic | |||

| R2 | 98.86 | 99.23 | ||

| Adjusted-R2 | 96.13 | 97.39 | ||

| Lack of fit (p-value) | 0.672 | 0.075 | ||

| Global Solution | |

|---|---|

| Components | Value |

| X1 | 74.5375 |

| X2 | 18.2339 |

| X3 | 2.8125 |

| X4 | 4.41606 |

| Parameter | Experimental Value | Predicted Value | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAB viability | 8.5549 ± 0.3408 | 8.74857 | 2.26 |

| Yeast viability | 8.9408 ± 0.1641 | 8.79799 | 1.60 |

| Type of Fermentation | Microorganism | log (CFUs/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t = 0 h | t = 36 h | ||||||

| 10−2 | 10−3 | 10−4 | 10−2 | 10−3 | 10−4 | ||

| Control | Mesophilic aerobic bacteria | >300 | >300 | 7.55 | >300 | >300 | 7.15 |

| Fungi and yeast | >300 | >300 | 7.25 | >300 | >300 | 8.49 | |

| Enteric bacteria | >300 | 5.72 | 6.57 | 4.14 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lactic acid bacteria | >300 | >300 | >300 | >300 | >300 | 8.22 | |

| Inoculum | Mesophilic aerobic bacteria | >300 | >300 | 7.08 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 7.5 |

| Fungi and yeast | >300 | >300 | 8.31 | >300 | >300 | 9.00 | |

| Enteric bacteria | >300 | 5.40 | 5.85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lactic acid bacteria | >300 | >300 | >300 | >300 | 7.37 | 8.17 | |

| Item | Characteristics | Qualification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fragrance/aroma | 7.5 |

| 2 | Flavor | 7.5 |

| 3 | Residual flavor | 7.25 |

| 4 | Acidity | 7.25 |

| 5 | Body | 7.5 |

| 6 | Uniformity | 10.0 |

| 7 | Sweetness | 10.0 |

| 8 | Clean cup | 10.0 |

| 9 | Balance | 7.25 |

| 10 | Taster score | 7.50 |

| Final score | 81.75 | |

| Item | Characteristics | Qualification |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fragrance/aroma | 8.00 |

| 2 | Flavor | 8.00 |

| 3 | Residual flavor | 7.75 |

| 4 | Acidity | 7.75 |

| 5 | Body | 7.50 |

| 6 | Uniformity | 10.0 |

| 7 | Sweetness | 10.0 |

| 8 | Clean cup | 10.0 |

| 9 | Balance | 7.75 |

| 10 | Taster score | 7.75 |

| Final score | 84.50 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polanía Rivera, A.M.; López Silva, J.; Torres-Valenzuela, L.S.; Plaza Dorado, J.L. Development of Starter Inoculum for Controlled Arabica Coffee Fermentation Using Coffee By-Products (Pulp and Mucilage Broth), Yeast, and Lactic Acid Bacteria. Fermentation 2024, 10, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation10100516

Polanía Rivera AM, López Silva J, Torres-Valenzuela LS, Plaza Dorado JL. Development of Starter Inoculum for Controlled Arabica Coffee Fermentation Using Coffee By-Products (Pulp and Mucilage Broth), Yeast, and Lactic Acid Bacteria. Fermentation. 2024; 10(10):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation10100516

Chicago/Turabian StylePolanía Rivera, Anna María, Jhennifer López Silva, Laura Sofía Torres-Valenzuela, and José Luis Plaza Dorado. 2024. "Development of Starter Inoculum for Controlled Arabica Coffee Fermentation Using Coffee By-Products (Pulp and Mucilage Broth), Yeast, and Lactic Acid Bacteria" Fermentation 10, no. 10: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation10100516

APA StylePolanía Rivera, A. M., López Silva, J., Torres-Valenzuela, L. S., & Plaza Dorado, J. L. (2024). Development of Starter Inoculum for Controlled Arabica Coffee Fermentation Using Coffee By-Products (Pulp and Mucilage Broth), Yeast, and Lactic Acid Bacteria. Fermentation, 10(10), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation10100516