The Role of Adsorption in Agarose Gel Cleaning of Artworks on Paper

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

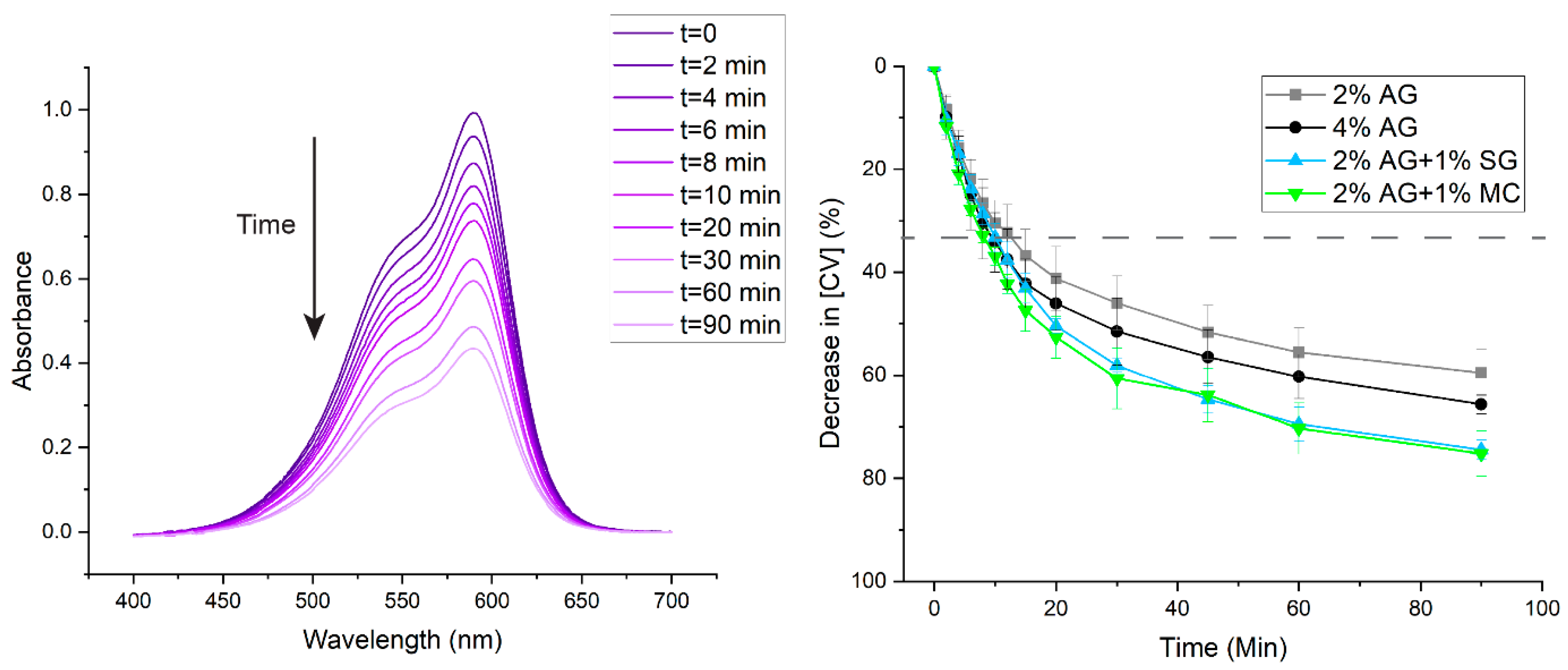

2.1. Adsorption of Crystal Violet Dye

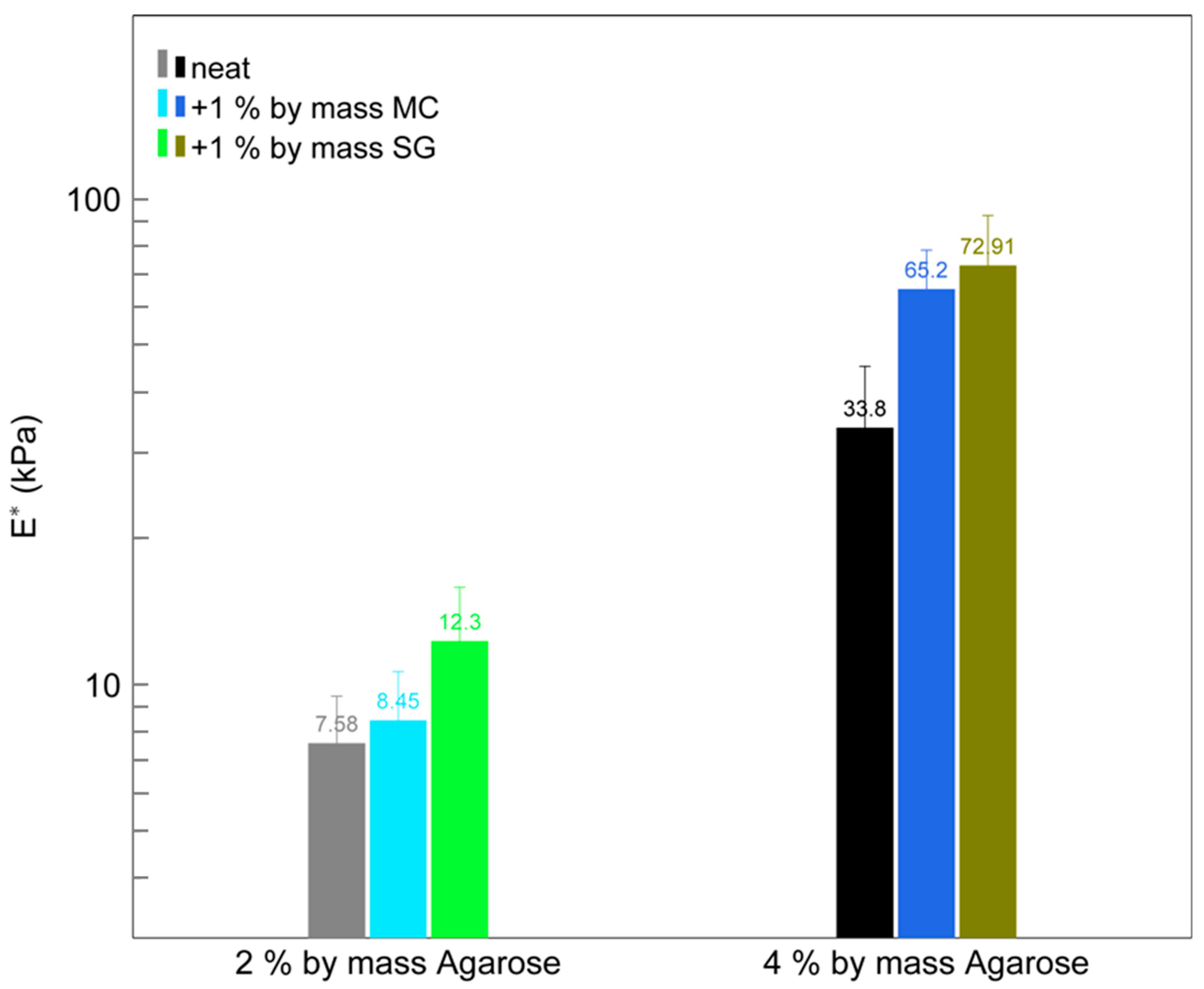

2.2. Physical Property Measurements

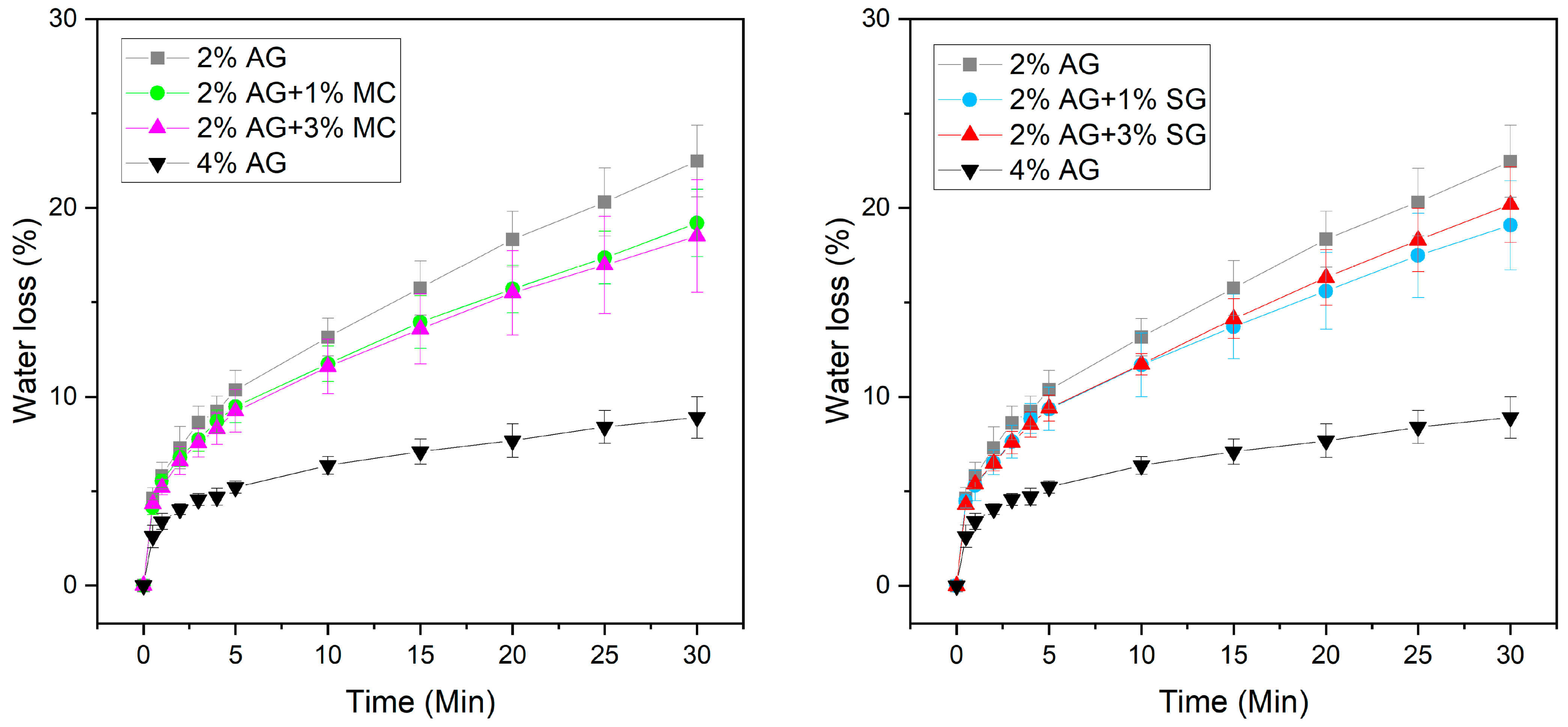

2.3. Water Loss Measurements

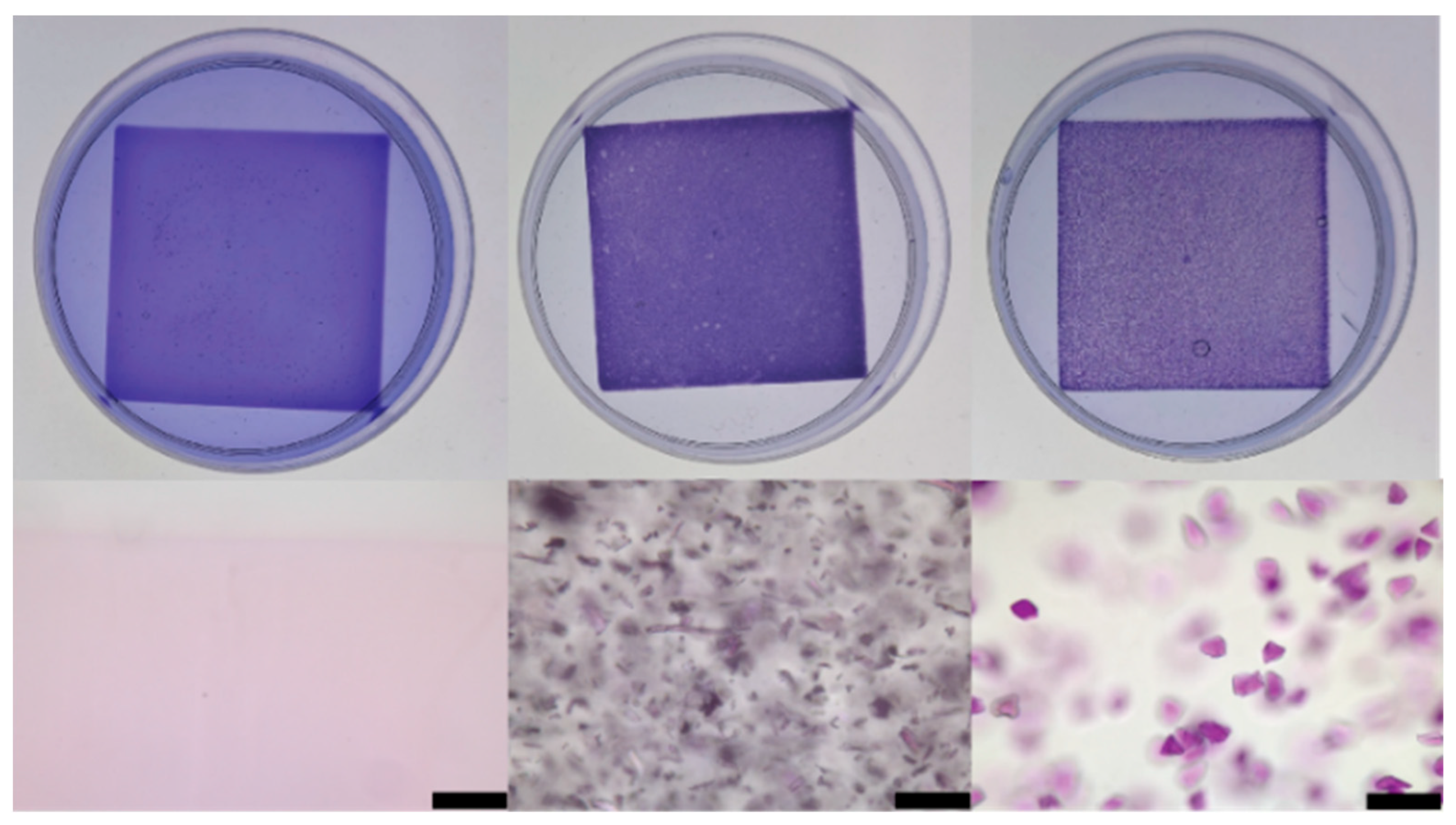

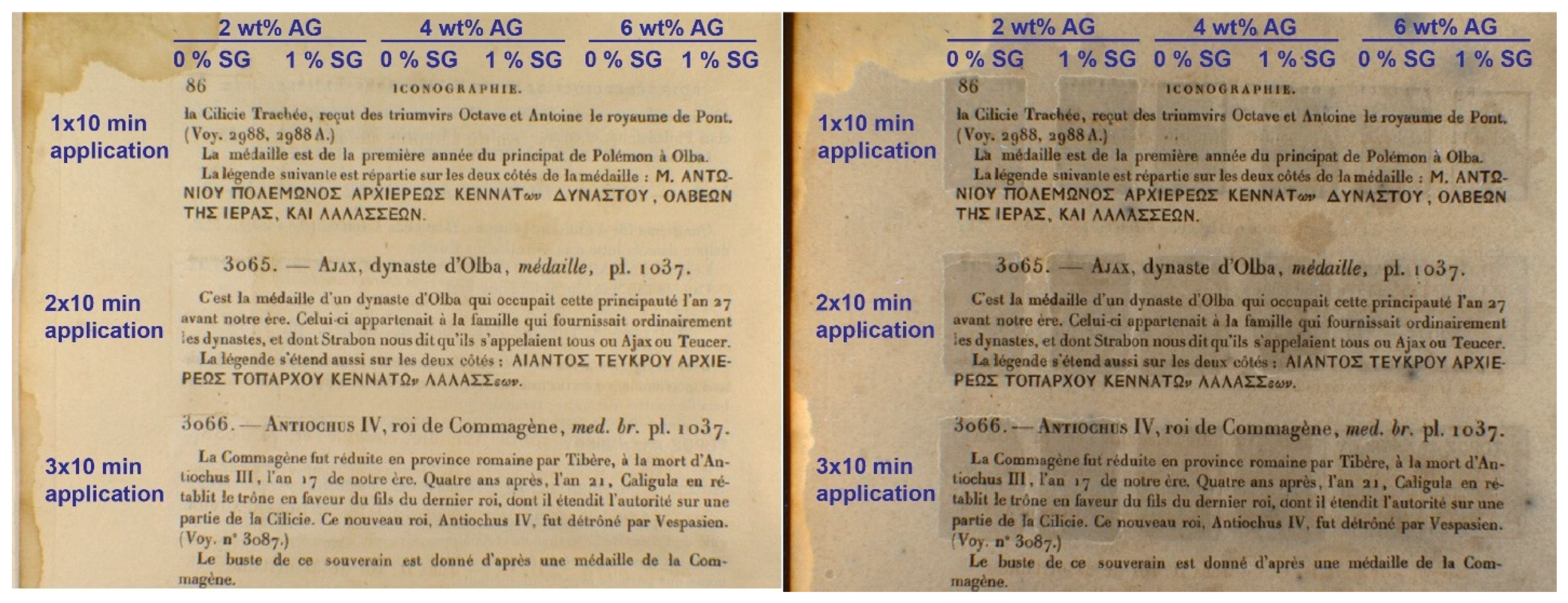

2.4. Comparative Gel Cleaning of 19th-Century Book Paper

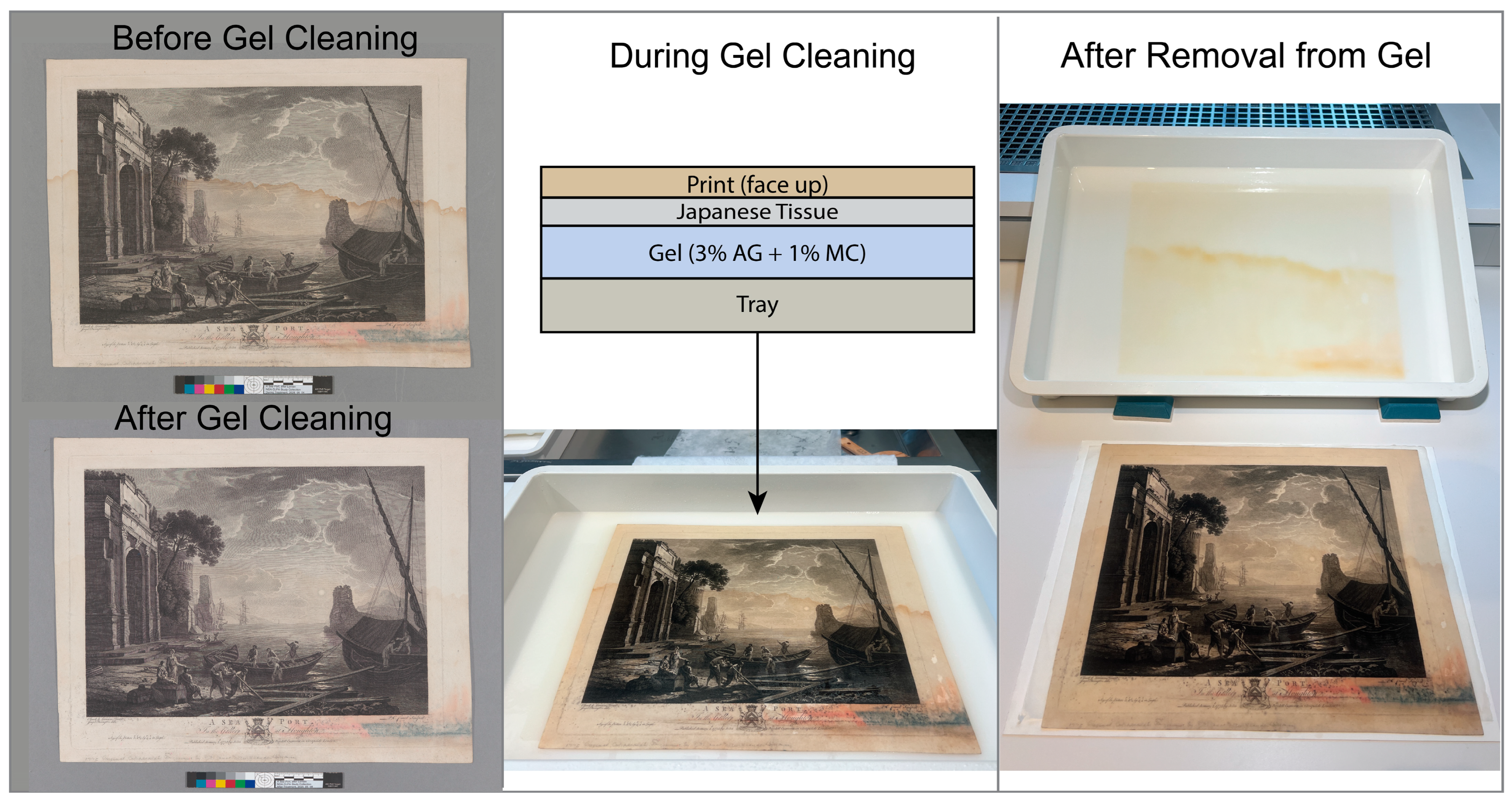

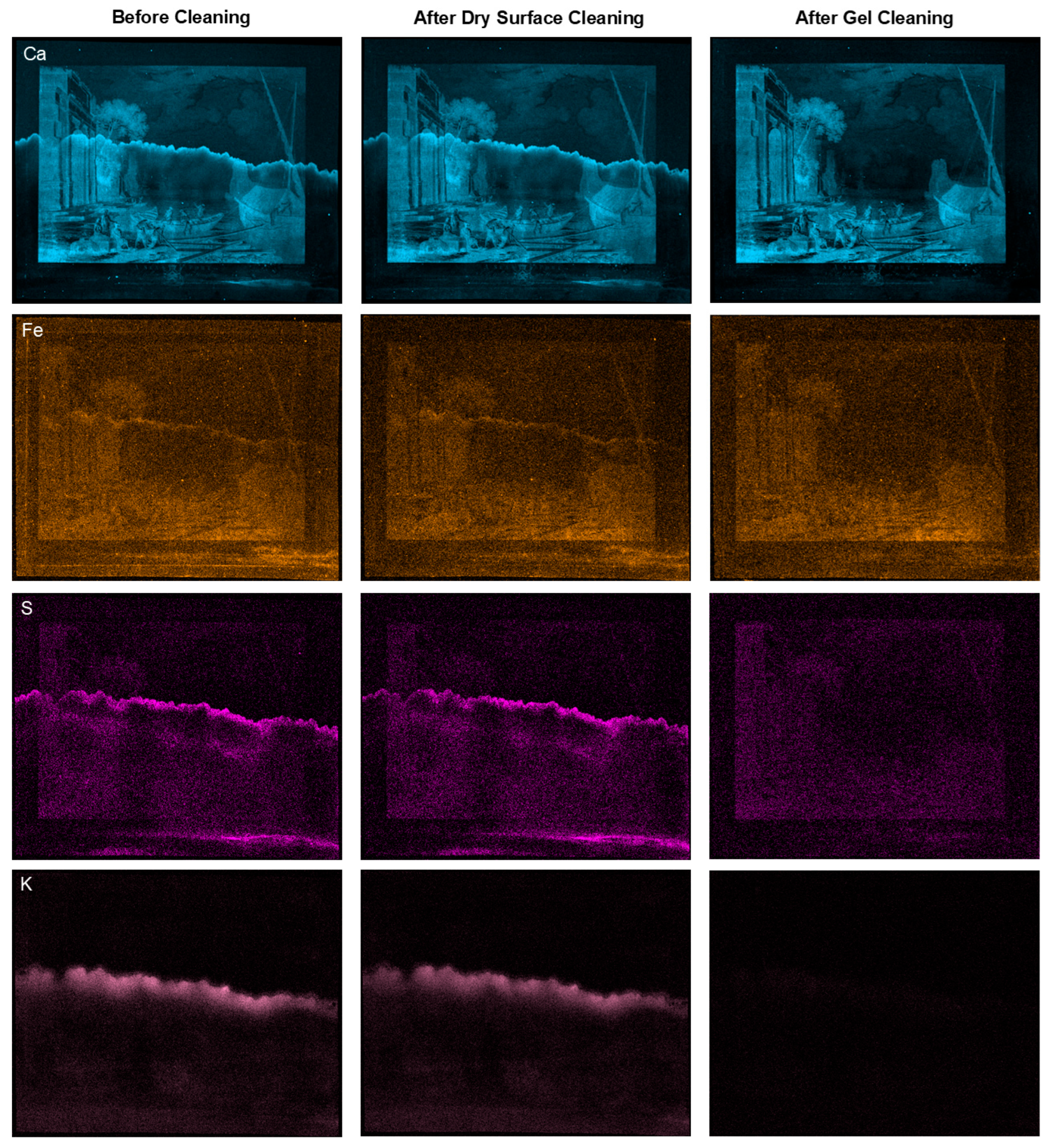

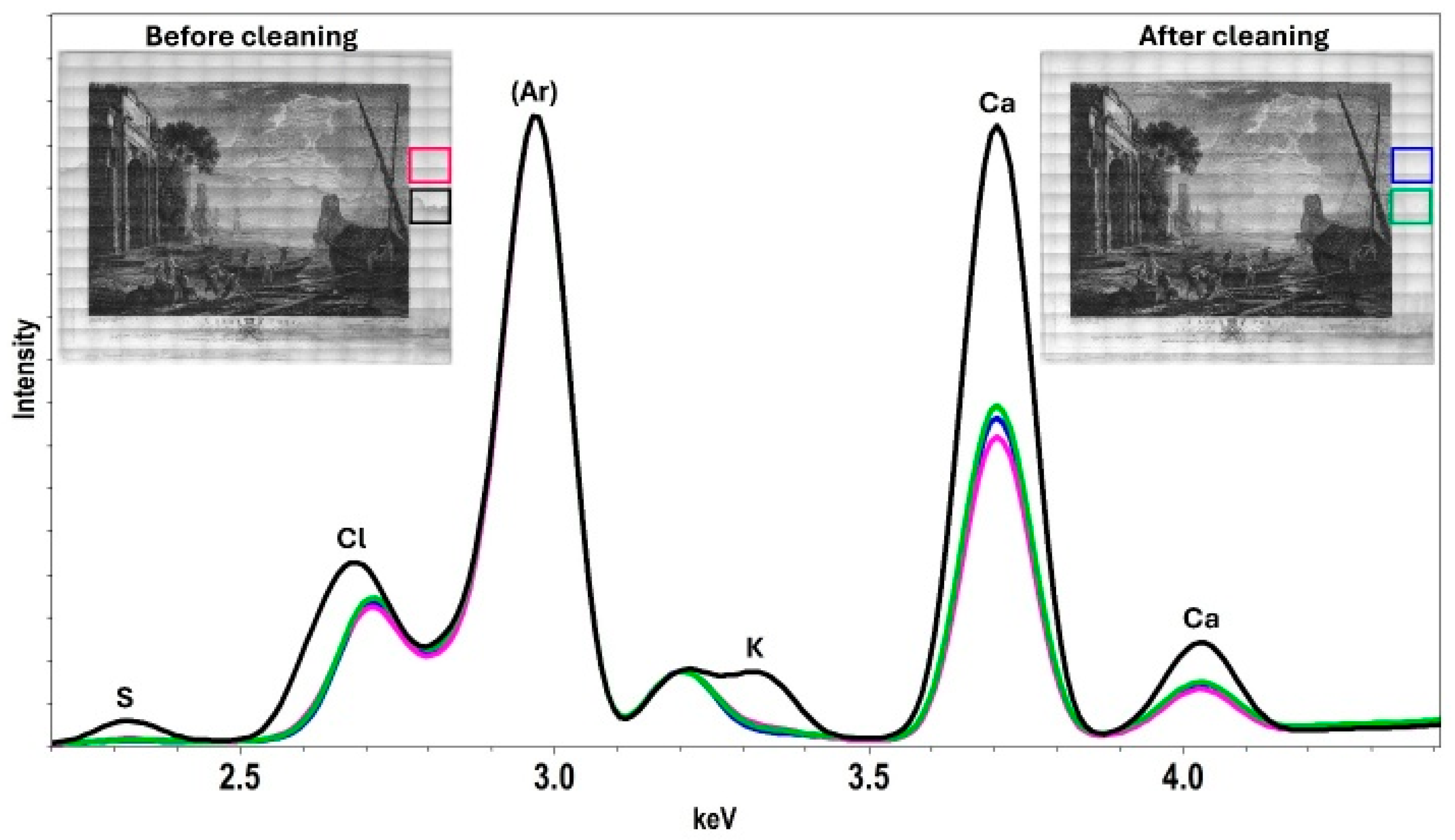

2.5. Gel Cleaning of a Water-Damaged 18th-Century Print with an MC-Containing Agarose Gel

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Gel Preparation

4.2.2. Solid Adsorption Kinetics Measurements

4.2.3. Gel Adsorption Kinetics Measurements

4.2.4. Elastic Modulus Measurements

4.2.5. Water Retention Measurements

4.2.6. Localized Gel Treatment of Book Page

4.2.7. Overall Gel Treatment of Print

4.2.8. X-Ray Fluorescence Mapping

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AG | Agarose |

| Br | Bromine |

| Ca | Calcium |

| Cl | Chlorine |

| CV | Crystal violet |

| Fe | Iron |

| K | Potassium |

| MC | Microcellulose |

| S | Sulfur |

| SG | Silica gel |

| UV–Vis | Ultraviolet/visible |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

References

- Dwan, A. Paper Complexity and the Interpretation of Conservation Research. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 1987, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmore, P.M. Paper Aging and the Influence of Water. In Paper and Water: A Guide for Conservators; Banik, G., Bruckle, I., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 219–254. [Google Scholar]

- Zervos, S.; Alexopoulou, I. Paper conservation methods: A literature review. Cellulose 2015, 22, 2859–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Reyden, D. Recent Scientific Research in Paper Conservation. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 1992, 31, 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warda, J.; Brückle, I.; Bezúr, A.; Kushel, D. Analysis of Agarose, Carbopol, and Laponite Gel Poultices in Paper Conservation. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2007, 46, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaksar-Baghan, N.; Koochakzaei, A.; Hamzavi, Y. An overview of gel-based cleaning approaches for art conservation. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, J.A.; Bonelli, N.; Giorgi, R.; Fratini, E.; Gorel, F.; Baglioni, P. Innovative hydrogels based on semi-interpenetrating p(HEMA)/PVP networks for the cleaning of water-sensitive cultural heritage artifacts. Langmuir 2013, 29, 2746–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuca, C.; Micheli, L.; Carbone, M.; Basoli, F.; Cervelli, E.; Iannuccelli, S.; Sotgiu, S.; Palleschi, A. Gellan hydrogel as a powerful tool in paper cleaning process: A detailed study. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 416, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.R.; Duncan, T.T.; Berrie, B.H.; Weiss, R.G. Rigid Polysaccharide Gels for Paper Conservation: A Residue Study. In Gels in the Conservation of Art; Angelova, L.V., Ormsby, B., Townsend, J.H., Wolbers, R., Eds.; Archetype: London, UK, 2017; pp. 250–256. [Google Scholar]

- Henniges, U.; Brückle, I.; Khaliliyan, H.; Böhmdorfer, S. Gellan residues on paper: Quantification and implication for paper conservation. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.; Severini, L.; Buratti, E.; Tavagnacco, L.; Sennato, S.; Micheli, L.; Missori, M.; Ruzicka, B.; Mazzuca, C.; Zaccarelli, E.; et al. Gellan-based hydrogels and microgels: A rheological perspective. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 354, 123329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severini, L.; Tavagnacco, L.; Angelini, R.; Franco, S.; Bertoldo, M.; Calosi, M.; Micheli, L.; Sennato, S.; Chiessi, E.; Ruzicka, B.; et al. Methacrylated gellan gum hydrogel: A smart tool to face complex problems in the cleaning of paper materials. Cellulose 2023, 30, 10469–10485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, B.; Franco, S.; Severini, L.; Tumiati, M.; Buratti, E.; Titubante, M.; Nigro, V.; Gnan, N.; Micheli, L.; Ruzicka, B.; et al. Gellan Gum Microgels as Effective Agents for a Rapid Cleaning of Paper. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2020, 2, 2791–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.; Sullivan, M. Targeted Cleaning of Works on Paper: Rigid Polysaccharide Gels and Conductivity in Aqueous Solutions. Book Pap. Group Annu. 2016, 35, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Seow, W.Y.; Hauser, C.A.E. Freeze–dried agarose gels: A cheap, simple and recyclable adsorbent for the purification of methylene blue from industrial wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guastaferro, M.; Baldino, L.; Cardea, S.; Reverchon, E. Different Drying Techniques Can Affect the Adsorption Properties of Agarose-Based Gels for Crystal Violet Removal. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, Q.; Cavallini, I.; Lasemi, N.; Sabbatini, S.; Tittarelli, F.; Rupprechter, G. Waste-Valorized Nanowebs for Crystal Violet Removal from Water. Small Sci. 2024, 4, 2300286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perullini, M.; Jobbagy, M.; Japas, M.L.; Bilmes, S.A. New method for the simultaneous determination of diffusion and adsorption of dyes in silica hydrogels. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 425, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellatolas, I.; Bantawa, M.; Damerau, B.; Guo, M.; Divoux, T.; Del Gado, E.; Bischofberger, I. Local Mechanism Governs Global Reinforcement of Nanofiller-Hydrogel Composites. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 20939–20948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

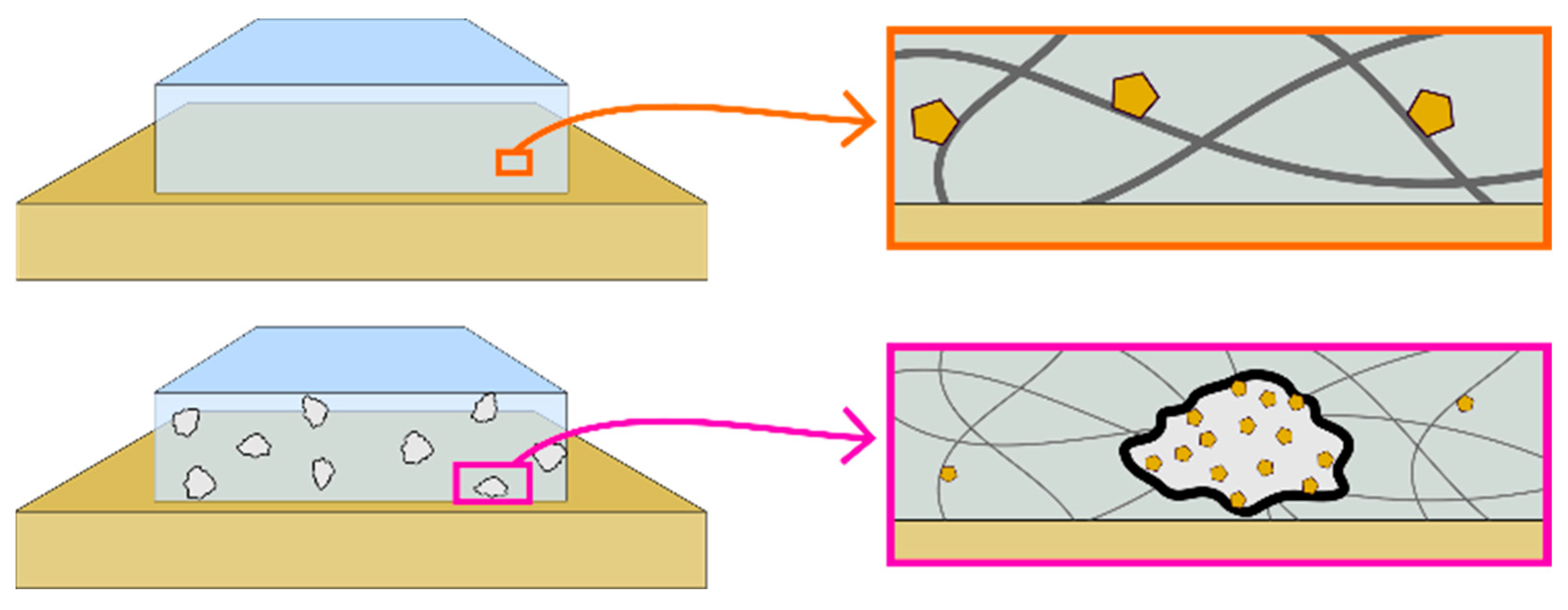

- Duncan, T.T.; Chan, E.P.; Beers, K.L. Maximizing Contact of Supersoft Bottlebrush Networks with Rough Surfaces To Promote Particulate Removal. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 45310–45318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, T.T.; Chan, E.P.; Beers, K.L. Quantifying the ‘press and peel’ removal of particulates using elastomers and gels. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 48, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertasa, M.; Poli, T.; Riedo, C.; Di Tullio, V.; Capitani, D.; Proietti, N.; Canevali, C.; Sansonetti, A.; Scalarone, D. A study of non-bounded/bounded water and water mobility in different agar gels. Microchem. J. 2018, 139, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, I.; Turunen, P.; Garms, B.C.; Rowan, A.; Corrie, S.; Grøndahl, L. Evaluation of techniques used for visualisation of hydrogel morphology and determination of pore size distributions. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansonetti, A.; Bertasa, M.; Canevali, C.; Rabbolini, A.; Anzani, M.; Scalarone, D. A review in using agar gels for cleaning art surfaces. J. Cult. Herit. 2020, 44, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, T.; Erhardt, D. Changes in paper color due to artificial aging and the effects of washing on color removal. In Proceedings of the ICOM Committee for Conservation, 10th Triennial Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 22–27 August 1993; pp. 507–515. [Google Scholar]

- Kosek, J.; I’Anson, S.; Tindal, A.; Daniels, V.; Sandy, M. Model discoloured paper for analysis of aqueous washing and other conservation processes/Untersuchung und Bewertung wässriger Behandlungstechniken mittels gefärbter Modellpapiere/Analyse et évaluation de techniques de traitement aqueux grâce aux papiers modèles colorés. Restaur. Int. J. Preserv. Libr. Arch. Mater. 2014, 35, 47–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.; Melo, R.A. Global shortage of technical agars: Back to basics (resource management). J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 2463–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusman, E. Tideline Formation in Paper Objects: Cellulose Degradation at the Wet-Dry Boundary. Stud. Hist. Art 1995, 51, 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, A.L. Degradation of Cellulose at the Wet/Dry Interface. I. The Effect of Some Conservation Treatments on Brown Lines. Restaur. Int. J. Preserv. Libr. Arch. Mater. 1996, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.-J.; Dupont, A.-L.; de la Rie, E.R. Degradation of cellulose at the wet-dry interface: I—Study of the depolymerization. Cellulose 2012, 19, 1135–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.J.; Dupont, A.L.; de la Rie, E.R. Degradation of cellulose at the wet-dry interface. II. Study of oxidation reactions and effect of antioxidants. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souguir, Z.; Dupont, A.-L.; de la Rie, E.R. Formation of Brown Lines in Paper: Characterization of Cellulose Degradation at the Wet−Dry Interface. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 2546–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shull, K.R. Contact mechanics and the adhesion of soft solids. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2002, 36, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, T.T.; Vicenzi, E.P.; Lam, T.; Brogdon-Grantham, S.A. A Comparison of Materials for Dry Surface Cleaning Soot-Coated Papers of Varying Roughness: Assessing Efficacy, Physical Surface Changes, and Residue. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2023, 62, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, H. Über die berührung fester elastischer Körper. J. Für Die Reine Angew. Math. 1881, 92, 156–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz, H. Über die Berührung fester elastischer Körper und Über die Härte. In Verhandlungen des Vereins zur Beförderung des Gewerbefleisscs; Verein zur Beförderung des Gewerbefleisses: Berlin, Germany, 1882. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.L. Contact Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.L.; Kendall, K.; Roberts, A.D. Surface energy and the contact of elastic solids. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1971, 324, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.L.; Heß, M.; Willert, E. Handbook of Contact Mechanics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Material Added to CV Solution | CV Removal in 1 h (%) |

|---|---|

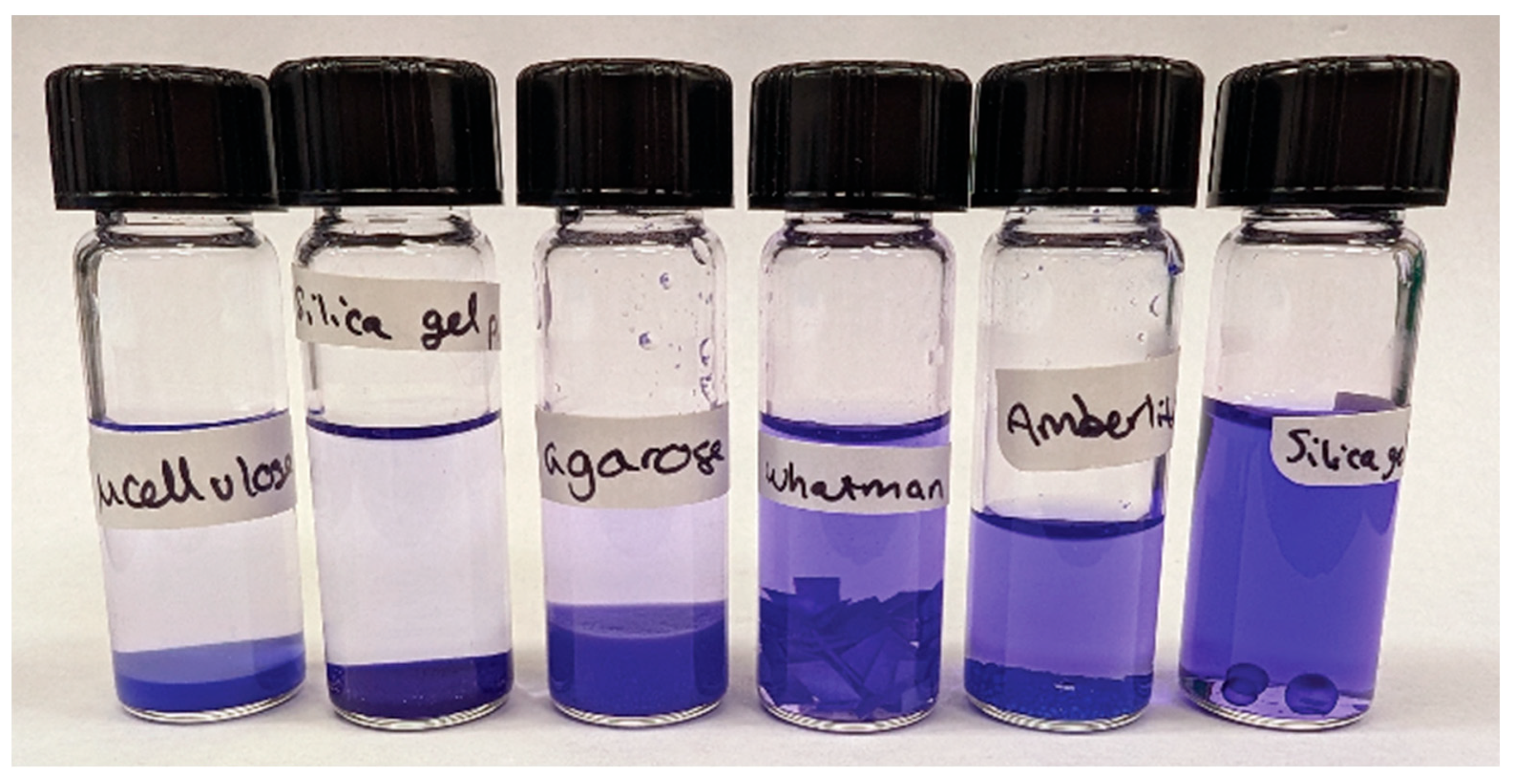

| Silica gel powder (SG) | 94 ± 1 |

| Microcellulose powder (MC) | 93 ± 5 |

| Agarose | 90 ± 3 |

| Whatman filter paper | 59 ± 3 |

| Amberlite XAD7HP | 45 ± 8 |

| Silica gel desiccant | 22 ± 3 |

| Control (glass vial; no adsorbent) | 14 ± 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duncan, T.T.; Sullivan, M.R.; Hughes, A.E.; Morales, K.M.; Chan, E.P.; Berrie, B.H. The Role of Adsorption in Agarose Gel Cleaning of Artworks on Paper. Gels 2025, 11, 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120965

Duncan TT, Sullivan MR, Hughes AE, Morales KM, Chan EP, Berrie BH. The Role of Adsorption in Agarose Gel Cleaning of Artworks on Paper. Gels. 2025; 11(12):965. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120965

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuncan, Teresa T., Michelle R. Sullivan, Amy Elizabeth Hughes, Kathryn M. Morales, Edwin P. Chan, and Barbara H. Berrie. 2025. "The Role of Adsorption in Agarose Gel Cleaning of Artworks on Paper" Gels 11, no. 12: 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120965

APA StyleDuncan, T. T., Sullivan, M. R., Hughes, A. E., Morales, K. M., Chan, E. P., & Berrie, B. H. (2025). The Role of Adsorption in Agarose Gel Cleaning of Artworks on Paper. Gels, 11(12), 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120965