Influence of Hydrocolloids on Lipid Digestion and Vitamin D Bioaccessibility of Emulsion-Filled Soft Gels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Emulsion Characterization

2.2. Characterization of Emulsion-Filled Gels

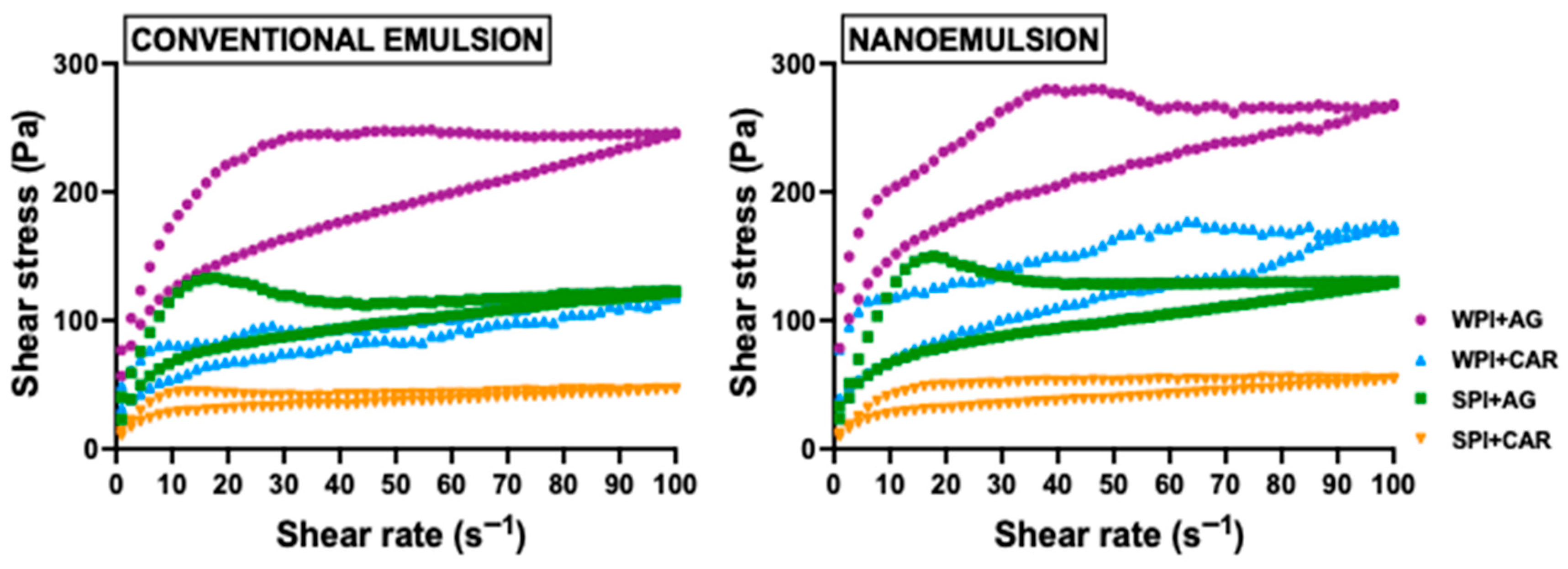

2.2.1. Flow Behavior

2.2.2. Texture Properties

2.3. In Vitro Digestion of Emulsion-Based Gels

2.3.1. Lipid Digestion

2.3.2. Vitamin D Bioaccessibility

2.3.3. Microstructure

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Emulsions and Emulsion-Filled Gels Preparation

4.3. Emulsions Characterization

4.4. Rheological and Texture Properties of Emulsion-Filled Gels

4.5. In Vitro Digestion of Emulsion-Filled Gels

4.5.1. In Vitro Digestion

- Oral Phase: A 25 g sample was chewed by a male volunteer (aged over 73 years old), following a structured protocol for bolus formation and collection: (1) The volunteer abstained from food for at least two hours before the experiment. (2) The volunteer rinsed their mouth with water before starting the protocol. (3) The gel sample was divided into three portions to facilitate oral handling. Each portion was placed in the oral cavity and held for 10 s without chewing or swallowing. (4) The formed bolus was collected in a 50 mL centrifuge tube until all portions had been processed. To complete the bolus preparation, 20 mL of preheated (37 °C) simulated oral fluid (SOF) and 125 µL of 0.3 M CaCl2 were added, maintaining a 1:1 (v/v) ratio of bolus to SOF, as specified by the INFOGEST protocol. Ethical approval for the involvement of human subjects in this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad de Santiago de Chile (reference number 228, dated 19 April 2023).

- Gastric Phase: The bolus obtained in the previous phase (50 mL) was mixed with simulated gastric fluid (SGF) at a 1:1 ratio. The SGF consisted of 40 mL of gastric electrolyte solution, 25 µL of 0.3 M CaCl2, and 2.5 mL of pepsin solution (1500 U/mL in the final mixture). The mixture was incubated in a temperature-controlled bath at 37 °C with constant agitation at 200 rpm for 180 min. The pH of the sample was adjusted using 0.5 M HCl with an automatic titration device (902 Titrando, Metrohm, Riverview, FL, USA) in three stages: (a) to pH 4 at a rate of 0.15 mL/min for 20 min, (b) to pH 3 at a rate of 0.08 mL/min for 40 min, and (c) to pH 2 at a rate of 0.07 mL/min for 120 min.

- Intestinal phase: The chyme was mixed with simulated intestinal fluid (SIF) in a 1:1 ratio. The SIF consisted of 42.5 mL of intestinal electrolyte solution, 200 µL of 0.3 M CaCl2, 12.5 mL of a bile solution (10 mmol/L), and 25 mL of pancreatin solution (80 U/mL in the final mixture). This mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 120 min with constant agitation at 200 rpm. The pH was maintained at 7 using an automatic titration device, which added 0.5 M NaOH to neutralize the free fatty acids (FFAs) released during lipolysis during digestion.

4.5.2. Quantification of Lipid Digestion

4.5.3. Vitamin D Bioaccessibility

4.5.4. Microstructure

4.6. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Cava, E.; Lombardo, M. Nutritional strategies for ageing populations: Focusing on dysphagia and geriatric nutritional needs. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 79, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Olivas, E.; Muñoz-Pina, S.; Andrés, A.; Heredia, A. Impact of elderly gastrointestinal alterations on in vitro digestion of salmon, sardine, sea bass and hake: Proteolysis, lipolysis and bioaccessibility of calcium and vitamins. Food Chem. 2020, 326, 127024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neri, M.C.; d’Alba, L. Nutrition and healthy aging: Prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, J.M.; Araújo, J.F.; Vieira, J.M.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Vicente, A.A. Tackling older adults’ malnutrition through the development of tailored food products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 115, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, A.B.A.; Samuel, P.J. Macronutrients and their roles in aging. In Evidence-Based Functional Foods for Prevention of Age-Related Diseases; Pathak, S., Banerjee, A., Duttaroy, A.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 137–153. [Google Scholar]

- Bojang, K.P.; Manchana, V. Nutrition and healthy aging: A review. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, M.; Szarvas, Z.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Feher, A.; Csipo, T.; Forrai, J.; Dosa, N.; Peterfi, A.; Lehoczki, A.; Tarantini, S.; et al. Nutrition strategies promoting healthy aging: From improvement of cardiovascular and brain health to prevention of age-associated diseases. Nutrients 2022, 15, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavar, M.; Sorić, T.; Bagarić, E.; Sarić, A.; Matek Sarić, M. The power of vitamin D: Is the future in precision nutrition through personalized supplementation plans? Nutrients 2024, 16, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisz-Urbańska, M.; Płudowski, P.; Marcinowska-Suchowierska, E. Vitamin D deficiency in older patients—Problems of sarcopenia, drug interactions, management in deficiency. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, C.C.Y.; Liang, S.W.; Mukhtar, K.; Kim, W.; Wang, Y.; Selomulya, C. Food emulsion gels from plant-based ingredients: Formulation, processing, and potential applications. Gels 2023, 9, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Li, X.; Wen, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, B.; Xu, D. Calcium ion-regulated oil body-filled pea protein isolate–inulin emulsion gels for dysphagia-oriented products. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 169, 111605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonlao, N.; Ruktanonchai, U.R.; Anal, A.K. Enhancing bioaccessibility and bioavailability of carotenoids using emulsion-based delivery systems. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 209, 112211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Guo, Y.; Dong, A.; Yang, X. Protein-based emulsion gels as materials for delivery of bioactive substances: Formation, structures, applications and challenges. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 144, 108921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes-Candia, C.; Martínez, J.C.; López-Rubio, A.; Salvia-Trujillo, L.; Martín-Belloso, O.; Martínez-Sanz, M. Emulsion gels and oil-filled aerogels as curcumin carriers: Nanostructural characterization of gastrointestinal digestion products. Food Chem. 2022, 387, 132877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Wan, L.; Duan, X.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, F.; Xu, X.; Pan, S. Potential low-calorie model that inhibits free fatty acid release and helps curcumin deliver in vitro: Ca2+-induced emulsion gels from low methyl-esterified pectin with erythritol. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 200, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Jiang, J.; Cheng, X.; Bi, L. Investigation of the stability and bioaccessibility of β-carotene encapsulated in emulsion gels with nonspherical droplets. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Hao, Y.; Gan, J.; Ye, H.; Shen, X. Development of quinoa protein emulsion gels to deliver curcumin: Influence of oil type. J. Food Eng. 2025, 384, 112260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah; Liu, L.; Javed, H.U.; Xiao, J. Engineering emulsion gels as functional colloids emphasizing food applications: A review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 890188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wan, Z.; Li, C.; Tang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, P.; Li, P.; et al. Impacts of citric acid concentration and pH on rheological properties of cold-set whey protein fibril hydrogels. LWT 2023, 183, 114872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhou, P.; Li, P.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G.; Zhang, M. Fibrous whey protein–mediated homogeneous and soft-textured emulsion gels for elderly: Enhancement of curcumin bioaccessibility. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, N.; Savignones, C.; López, A.; Zúñiga, R.N.; Arancibia, C. Effect of gelling agent type on the physical properties of nanoemulsion-based gels. Colloids Interfaces 2023, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Ding, Y. Enhanced probiotic viability in innovative double-network emulsion gels: Synergistic effects of whey protein concentrate–xanthan gum complex and κ-carrageenan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 131758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Zhan, Z.; Duan, Q.; Yang, Y.; Xie, H.; Dong, X.; Zhang, H.; Yu, L. Application of soybean protein isolate–polysaccharide hybrid emulsion gels as alternative fats in plant-based meats. LWT 2025, 218, 117524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, N.; Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Yang, X. Construction and formation mechanism of phase-change polysaccharide–protein composite emulsion gels: For simultaneous printing of complex food structures. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 160, 110817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiasmin, M.N.; Al Azad, S.; Easdani, M.; Islam, M.S.; Hussain, M.; Cao, W.; Chen, N.; Uriho, A.; Asaduzzaman, M.; Liu, C.; et al. The state-of-the-art on exploring polysaccharide-protein interactions and its mechanisms, stability, and their role in food systems. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 1, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W.W.; Deutz, N.E.; Volpi, E.; Apovian, C.M. Nutritional interventions: Dietary protein needs and influences on skeletal muscle of older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, A.; Li, D.; Guo, Y.; Sun, L. Applications of mixed polysaccharide–protein systems in fabricating multi-structured binary food gels: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Hao, S.; Han, H.; Du, P.; Li, A.; Shao, H.; Li, C.; Liu, L. Ultrasonic modification of whey protein isolate: Implications for the structural and functional properties. LWT 2021, 152, 112272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Regenstein, J.M.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Z. Soy protein isolates: A review of their composition, aggregation, and gelation. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1940–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascuta, M.S.; Varvara, R.A.; Teleky, B.E.; Szabo, K.; Plamada, D.; Nemeş, S.A.; Mitrea, L.; Martău, G.A.; Ciont, C.; Călinoiu, L.F.; et al. Polysaccharide-based edible gels as functional ingredients: Characterization, applicability, and human health benefits. Gels 2022, 8, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Hart, P.; Thakur, V.K. Seaweed based hydrogels: Extraction, gelling characteristics, and applications in the agriculture sector. ACS Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 1876–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, A.; Wani, S.M.; Malik, A.R.; Gull, A.; Ramniwas, S.; Nayik, G.A.; Ercisli, S.; Marc, R.A.; Ullah, R.; Bari, A. Recent insights into nanoemulsions: Their preparation, properties and applications. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, J.; Pinjari, D.V.; Kumar Saharan, V.; Pandit, A.B. Critical review on hydrodynamic cavitation as an intensifying homogenizing technique for oil-in-water emulsification: Theoretical insight, current status, and future perspectives. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 10587–10602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giorgio, L.; Salgado, P.R.; Mauri, A.N. Fish oil-in-water emulsions stabilized by soy proteins and cellulose nanocrystals. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2022, 3, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Jafari, S.M. General aspects of nanoemulsions and their formulation. In Nanoemulsions; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupikowska-Stobba, B.; Domagała, J.; Kasprzak, M.M. Critical review of techniques for food emulsion characterization. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, X.; Su, D.; Chen, L.; Chen, C.; Jin, B. Molecular mechanisms affecting the stability of high internal phase emulsions of zein–soy isoflavone complexes fabricated with ultrasound-assisted dynamic high-pressure microfluidization. Food Res. Int. 2023, 170, 113051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjami, T.; Madadlou, A. An overview on preparation of emulsion-filled gels and emulsion particulate gels. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Rao, J. Food-grade nanoemulsions: Formulation, fabrication, properties, performance, biological fate, and potential toxicity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 285–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Shams, R.; Dash, K.K.; Shaikh, A.M.; Kovács, B. Protein–polysaccharide complexes and conjugates: Structural modifications and interactions under diverse treatments. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methacanon, P.; Gamonpilas, C.; Kongjaroen, A.; Buathongjan, C. Food polysaccharides and roles of rheology and tribology in rational design of thickened liquids for oropharyngeal dysphagia: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 4101–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Padilla, L.P. Rheology of liquid foods under shear flow conditions: Recently used models. J. Texture Stud. 2024, 55, e12802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirazimi, F.; Saldo, J.; Sepulcre, F.; Gràcia, A.; Pujola, M. Enriched potato puree with soy protein for dysphagia patients using 3D printing. Food Front. 2022, 3, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Moschakis, T. Whey proteins: Musings on denaturation, aggregate formation and gelation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3793–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sanz, M.; Ström, A.; Lopez-Sanchez, P.; Knutsen, S.H.; Ballance, S.; Zobel, H.K.; Sokolova, A.; Gilbert, E.P.; López-Rubio, A. Advanced structural characterization of agar-based hydrogels: Rheological and small-angle scattering studies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 236, 115655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, R.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Q.; Qu, Y.; Jia, X.; Yin, L. Curcumin-loaded zein–alginate nanogels with “core–shell” structure: Formation, characterization and simulated digestion. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 251, 126201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmarhoum, S.; Ako, K.; Munialo, C.D.; Rharbi, Y. Helicity degree of carrageenan conformation determines the polysaccharide and water interactions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 314, 120952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, L.; Li, K.; Zhu, F.; Wang, G.; Xi, G.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, B.; Xie, F. Revealing the role of λ-carrageenan on the enhancement of gel-related properties of acid-induced soy protein isolate/λ-carrageenan system. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 150, 109608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierulf, A.V.; Whaley, J.K.; Liu, W.; Smoot, J.T.; Jenab, E.; Perez Herrera, M.; Abbaspourrad, A. Heat- and shear-reversible networks in food: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3405–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez, F.C.; Gómez, I.; Merino, G.; Beriain, M. Textural characteristics of safe dishes for dysphagic patients: A multivariate analysis approach. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Chávez, R.E.; Schaen-Heacock, N.E.; Hitchcock, M.E.; Kurosu, A.; Suzuki, R.; Hartel, R.W.; Ciucci, M.R.; Rogus-Pulia, N.M. Effects of food and liquid properties on swallowing physiology and function in adults. Dysphagia 2023, 38, 785–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDDSI. The IDDSI Framework: International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative. Available online: https://www.iddsi.org/images/Publications-Resources/DetailedDefnTestMethods/English/V2DetailedDefnEnglish31july2019.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Hadde, E.K.; Chen, J. Texture and texture assessment of thickened fluids and texture-modified food for dysphagia management. J. Texture Stud. 2021, 52, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Al-Attabi, Z.H.; Al-Habsi, N.; Al-Khusaibi, M. Measurement of instrumental texture profile analysis (TPA) of foods. In Techniques to Measure Food Safety and Quality; Khan, M.S., Shafiur Rahman, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Kelly, A.L.; Miao, S. The role of mixing sequence in structuring O/W emulsions and emulsion gels produced by electrostatic protein–polysaccharide interactions between soy protein isolate-coated droplets and alginate molecules. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 113, 106537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibañez, F.C.; Merino, G.; Marín-Arroyo, M.R.; Beriain, M.J. Instrumental and sensory techniques to characterize the texture of foods suitable for dysphagic people: A systematic review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 2738–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, S.; Kawate, N.; Mizuma, M. What type of food can older adults masticate: Evaluation of mastication performance using color-changeable chewing gum. Dysphagia 2017, 32, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichero, J.A.Y. Evaluating chewing function: Expanding the dysphagia field using food oral processing and the IDDSI framework. J. Texture Stud. 2020, 51, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishinari, K.; Fang, Y.; Rosenthal, A.J. Human oral processing and texture profile analysis parameters: Bridging the gap between sensory evaluation and instrumental measurements. J. Texture Stud. 2019, 50, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munialo, C.D.; Kontogiorgos, V.; Euston, S.R.; Nyambayo, I. Rheological, tribological and sensory attributes of texture-modified foods for dysphagia patients and the elderly: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 1862–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makame, J.; Nolden, A.A.; Emmambux, M.N. Texture properties of foods targeted for individuals with limited oral processing capabilities: The elderly, dysphagia, and head and neck cancer patients. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 3949–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Bi, L. Characterization and stability of low-oil emulsion gels with newly shaped droplets stabilized by camellia saponin and κ-carrageenan. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 149, 109585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquelme, N.; Robert, P.; Troncoso, E.; Arancibia, C. Influence of particle size and hydrocolloid type on lipid digestion of thickened emulsions. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 5955–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Tian, W.; Abdullah; Wang, H.; Chen, M.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Lu, M.; Song, M.; Cao, Y. Updated design strategies for oral delivery systems: Maximized bioefficacy of dietary bioactive compounds achieved by inducing proper digestive fate and sensory attributes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 817–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, X.; Bao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Huang, L.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Y.; Lu, W. Investigation of the in vitro digestion fate and oxidation of protein-based oleogels prepared by pine nut oil. LWT 2022, 164, 113660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Li, Y. Structured emulsion-based delivery systems: Controlling the digestion and release of lipophilic food components. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 159, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infantes-Garcia, M.R.; Verkempinck, S.H.E.; Gonzalez-Fuentes, P.G.; Hendrickx, M.E.; Grauwet, T. Lipolysis product formation during in vitro gastric digestion is affected by the emulsion interfacial composition. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 110, 106163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, A.; Mulet-Cabero, A.I.; Torcello-Gómez, A. Simulating human digestion: Developing our knowledge to create healthier and more sustainable foods. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 9397–9431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günter, E.A.; Martynov, V.V.; Belozerov, V.S.; Martinson, E.A.; Litvinets, S.G. Characterization and swelling properties of composite gel microparticles based on pectin and κ-carrageenan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, H.J.; Ye, A.; Acevedo-Fani, A.; Singh, H. In vitro digestion of curcumin–nanoemulsion-enriched dairy protein matrices: Impact of the type of gel structure on the bioaccessibility of curcumin. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 117, 106692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Chatterjee, N.; Chakraborty, A.; Banerjee, A.; Haiti, S.B.; Datta, S.; Chattopadhyay, H.; Dhar, P. Fabrication of rice bran oil nanoemulsion and conventional emulsion with mustard protein isolate as a novel excipient: Focus on shelf-life stability, lipid digestibility and cellular bioavailability. Food Hydrocoll. Health 2023, 4, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.B.; Simpson, R.; Vega-Castro, O.; Del Campo, V.; Pinto, M.; Fuentes, L.; Nuñez, H.; Young, A.K.; Ramírez, C. Effect of particle size on in vitro intestinal digestion of emulsion-filled gels: Mathematical analysis based on the Gallagher–Corrigan model. Food Bioprod. Process. 2020, 120, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, M.; Guo, Q. Understanding formation, gastrointestinal breakdown, and application of whey protein emulsion gels: Insights from intermolecular interactions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e70034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, C.; Ma, Y.; Shen, L.; Gong, Q.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, L. Study on the structure, function, and interface characteristics of soybean protein isolate by industrial phosphorylation. Foods 2023, 12, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, S.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y. Fabrication, in vitro digestion and pH-responsive release behavior of soy protein isolate glycation conjugate-based hydrogels. Food Res. Int. 2023, 169, 112884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zou, L.; McClements, D.J.; Liu, W. Recent progress in improving the bioavailability of nutraceutical-loaded emulsions after oral intake: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 3963–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, R.; Chang, M.; Wang, X. Medium- and long-chain structured triacylglycerol enhances vitamin D bioavailability in an emulsion-based delivery system: Combination of in vitro and in vivo studies. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 1762–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddir, M.; Porras Yaruro, J.F.; Cocco, E.; Hardy, E.M.; Appenzeller, B.M.; Guignard, C.; Larondelle, Y.; Bohn, T. Impact of protein-enriched plant food items on the bioaccessibility and cellular uptake of carotenoids. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iddir, M.; Yaruro, J.F.P.; Larondelle, Y.; Bohn, T. Gastric lipase can significantly increase lipolysis and carotenoid bioaccessibility from plant food matrices in the harmonized INFOGEST static in vitro digestion model. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 9043–9053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G.; De Pinho, S.C. Microstructural analysis of whey/soy protein isolate mixed gels using confocal Raman microscopy. Foods 2021, 10, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhao, G.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, L.; Liu, H. Protease-induced soy protein isolate characteristics and structure evolution at the oil–water interface of emulsion. J. Food Eng. 2022, 317, 110849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, F.; Gao, Y.; Mao, L. Emulsion gels with different proteins at the interface: Structures and delivery functionality. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 116, 106637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Fani, A.; Singh, H. Biophysical insights into modulating lipid digestion in food emulsions. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022, 85, 101129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, H.; Stein, H. Differences in amino acid digestibility and protein quality among various protein isolates and concentrates derived from cereal grains, plant and dairy proteins. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa050_004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddir, M.; Vahid, F.; Merten, D.; Larondelle, Y.; Bohn, T. Influence of proteins on the absorption of lipophilic vitamins, carotenoids and curcumin: A review. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, 2200076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arancibia, C.; Paredes-Toledo, J.; Riquelme, N. Oral structural breakdown and sensory perception of plant-based emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 156, 110291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamonpilas, C.; Kongjaroen, A.; Methacanon, P. The importance of shear and extensional rheology and tribology as design tools for developing food thickeners for dysphagia management. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 140, 108603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, O.; Lesmes, U.; Shani-Levi, C.S.; Calahorra, A.A.; Lavoisier, A.; Morzel, M.; Rieder, A.; Feron, G.; Nebbia, S.; Mashiah, L.; et al. Static in vitro digestion model adapted to the general older adult population: An INFOGEST international consensus. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 4569–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; McClements, D.J. New mathematical model for interpreting pH-stat digestion profiles: Impact of lipid droplet characteristics on in vitro digestibility. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 8085–8092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoener, A.L.; Zhang, R.; Lv, S.; Weiss, J.; McClements, D.J. Fabrication of plant-based vitamin D3-fortified nanoemulsions: Influence of carrier oil type on vitamin bioaccessibility. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1826–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Emulsion Type | Droplet Size | Polydispersity Index [-] | Creaming Index [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional emulsion (CE) | 20.7 ± 0.4 b µm | - | 9.4 ± 0.2 a |

| Nanoemulsion (NE) | 193.5 ± 2.6 a nm | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 3.8 ± 0.2 b |

| Sample | K [Pa s] | n | η50s−1 [Pa s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| CE + WPI + CAR | 27.39 ± 1.37 b | 0.34 ± 0.01 a | 2021 ± 96 b |

| CE + WPI + AG | 84.12 ± 1.53 c | 0.25 ± 0.01 c | 5494 ± 107 c |

| CE + SPI + CAR | 18.95 ± 1.63 a | 0.23 ± 0.01 d | 924 ± 115 a |

| CE + SPI + AG | 26.16 ± 1.44 b | 0.31 ± 0.01 b | 2121 ± 101 b |

| NE + WPI + CAR | 28.63 ± 1.77 b | 0.35 ± 0.01 a | 2158 ± 136 b |

| NE + WPI + AG | 89.67 ± 1.37 d | 0.25 ± 0.01 c | 5903 ± 96 d |

| NE + SPI + CAR | 18.73 ± 2.16 a | 0.21 ± 0.01 d | 925 ± 152 a |

| NE + SPI + AG | 29.34 ± 1.37 b | 0.31 ± 0.01 b | 2262 ± 152 b |

| Sample | Hardness [N/m2] | Adhesiveness [J/m2] | Cohesiveness [-] |

|---|---|---|---|

| CE + WPI + CAR | 495 ± 38 cd | 0.05 ± 0.01 bc | 0.57 ± 0.02 bc |

| CE + WPI + AG | 682 ± 46 e | 0.06 ± 0.01 c | 0.63 ± 0.02 d |

| CE + SPI + CAR | 297 ± 38 a | 0.02 ± 0.01 a | 0.43 ± 0.02 a |

| CE + SPI + AG | 412 ± 38 bc | 0.03 ± 0.01 ab | 0.56 ± 0.02 b |

| NE + WPI + CAR | 509 ± 38 cd | 0.05 ± 0.01 c | 0.57 ± 0.02 bc |

| NE + WPI + AG | 586 ± 39 de | 0.06 ± 0.01 c | 0.62 ± 0.02 cd |

| NE + SPI + CAR | 339 ± 48 a | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.46 ± 0.02 a |

| NE + SPI + AG | 353 ± 38 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 abc | 0.53 ± 0.02 b |

| Sample | Emulsion Type | Type and Concentration of Hydrocolloid | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein (% w/w) | Polysaccharide (% w/w) | ||

| CE + WPI + CAR | Conventional emulsion (CE) | Whey protein isolate (WPI) 5.97% | κ-carrageenan (CAR) 0.75% |

| CE + WPI + AG | Agar (AG) 0.75% | ||

| CE + SPI + CAR | Soy protein isolate (SPI) 5.83% | κ-carrageenan (CAR) 0.75% | |

| CE + SPI + AG | Agar (AG) 0.75% | ||

| NE + WPI + CAR | Nanoemulsion (NE) | Whey protein isolate (WPI) 5.97% | κ-carrageenan (CAR) 0.75% |

| NE + WPI + AG | Agar (AG) 0.75% | ||

| NE + SPI + CAR | Soy protein isolate (SPI) 5.83% | κ-carrageenan (CAR) 0.75% | |

| NE + SPI + AG | Agar (AG) 0.75% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arancibia, C.; Rojas, C.; Meneses, M.; Vielma, K.; Vásquez, T.; Riquelme, N. Influence of Hydrocolloids on Lipid Digestion and Vitamin D Bioaccessibility of Emulsion-Filled Soft Gels. Gels 2025, 11, 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120964

Arancibia C, Rojas C, Meneses M, Vielma K, Vásquez T, Riquelme N. Influence of Hydrocolloids on Lipid Digestion and Vitamin D Bioaccessibility of Emulsion-Filled Soft Gels. Gels. 2025; 11(12):964. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120964

Chicago/Turabian StyleArancibia, Carla, Cristóbal Rojas, Matías Meneses, Karen Vielma, Teresa Vásquez, and Natalia Riquelme. 2025. "Influence of Hydrocolloids on Lipid Digestion and Vitamin D Bioaccessibility of Emulsion-Filled Soft Gels" Gels 11, no. 12: 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120964

APA StyleArancibia, C., Rojas, C., Meneses, M., Vielma, K., Vásquez, T., & Riquelme, N. (2025). Influence of Hydrocolloids on Lipid Digestion and Vitamin D Bioaccessibility of Emulsion-Filled Soft Gels. Gels, 11(12), 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120964