Linearly Responsive, Reliable, and Stretchable Strain Sensors Based on Polyaniline Composite Hydrogels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

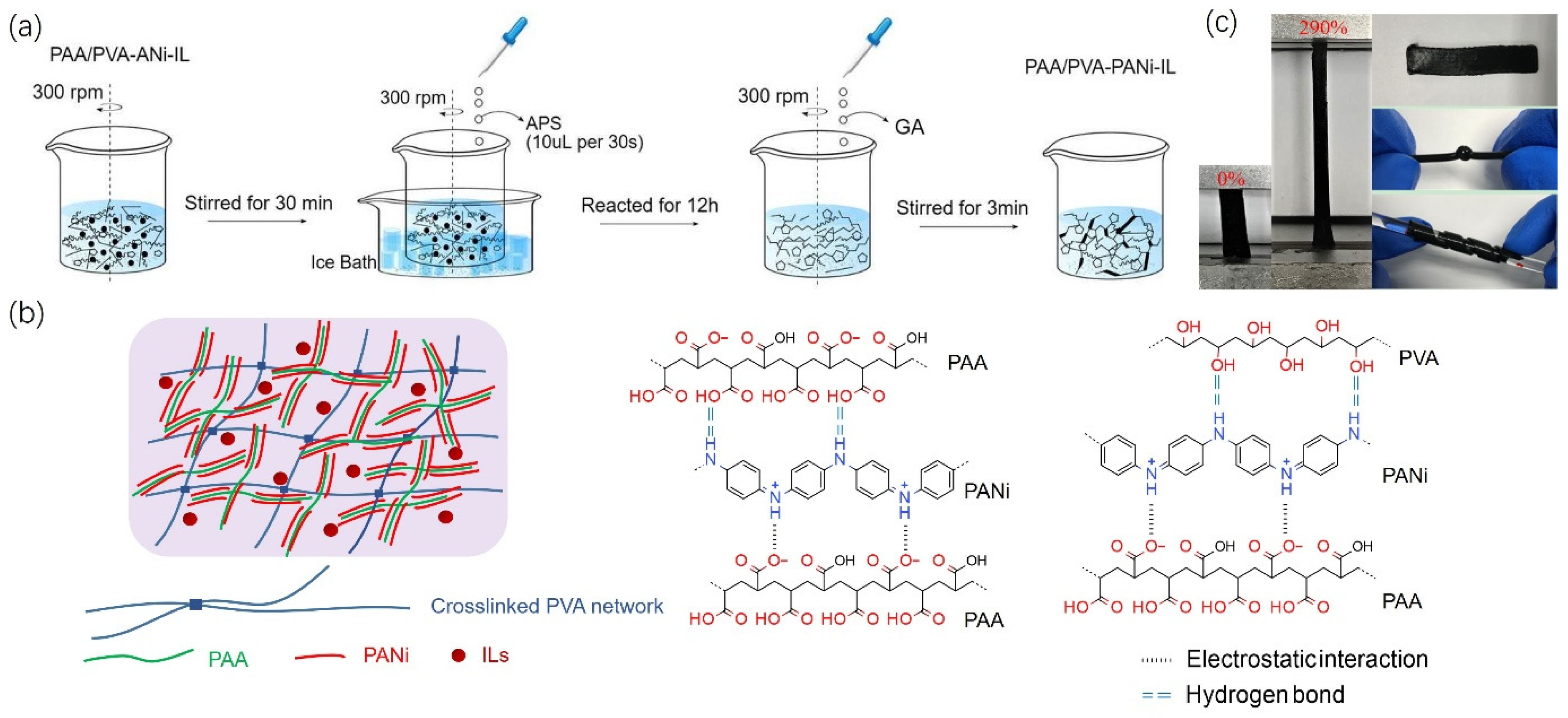

2.1. The Preparation of PVA-PAA/PANi/[EMIM]TFSI Conductive Hydrogels

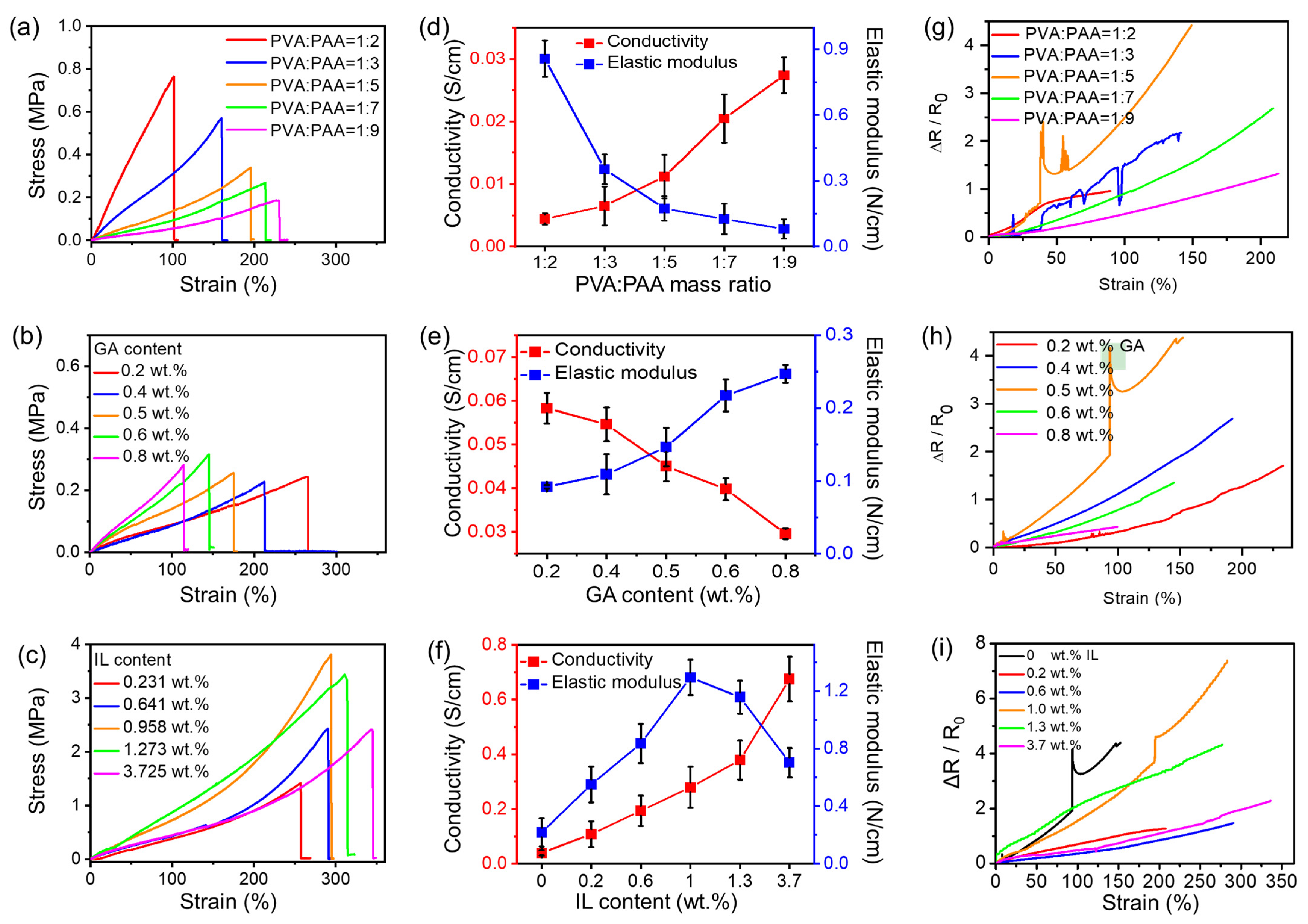

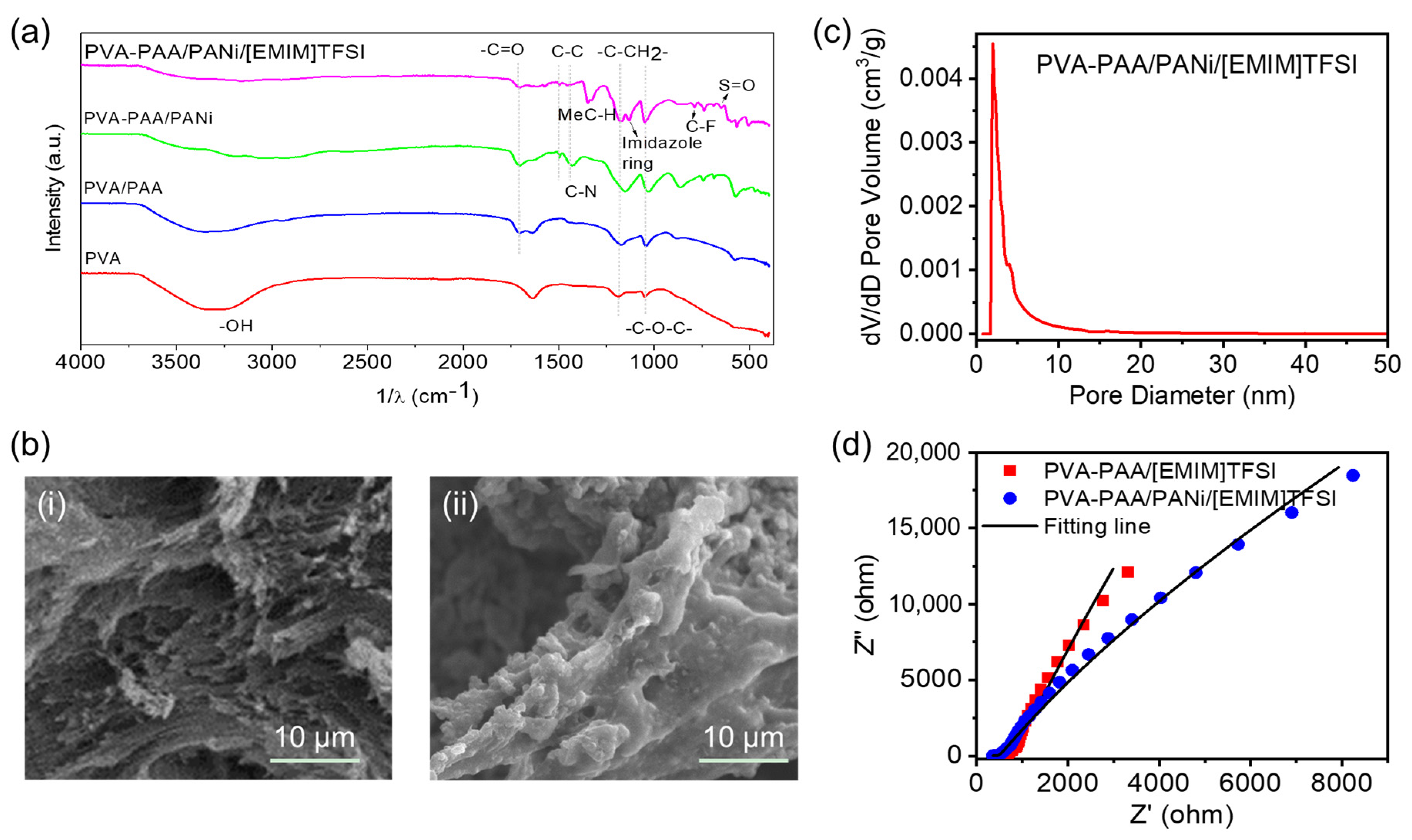

2.2. Optimization of Preparation Conditions and Sample Characterization

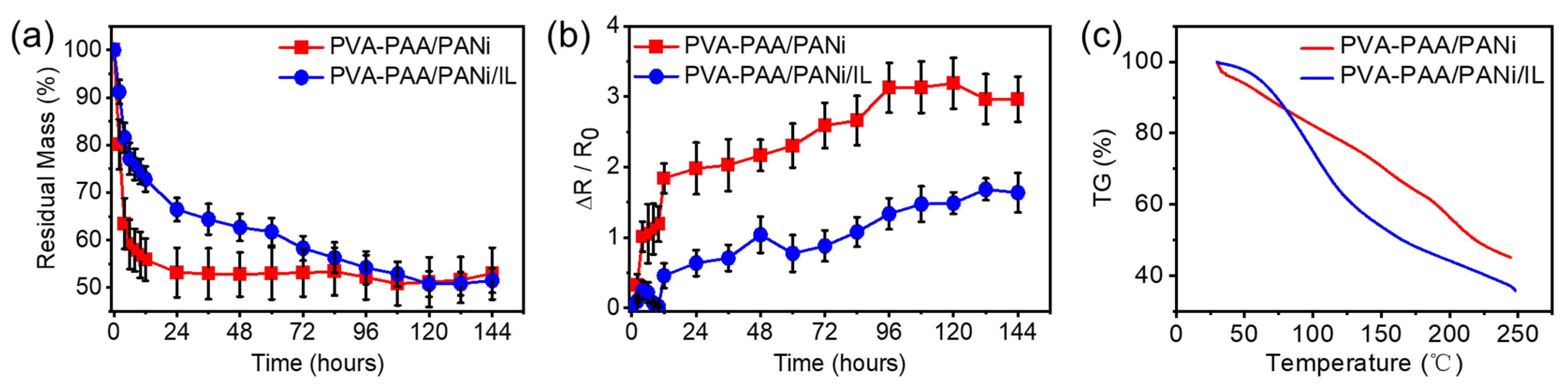

2.3. The Anti-Drying Property of PVA-PAA/PANi/[EMIM]TFSI Conductive Hydrogels

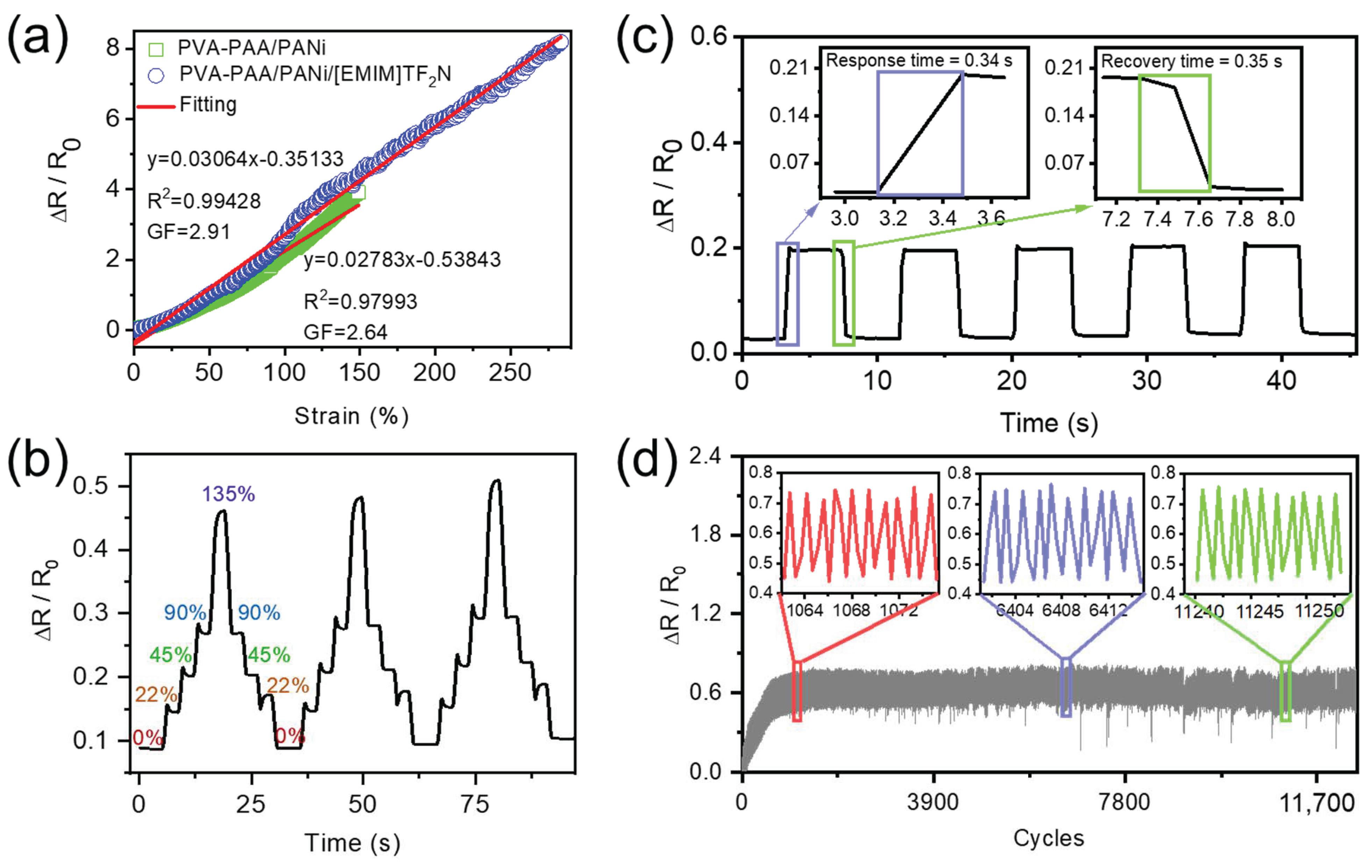

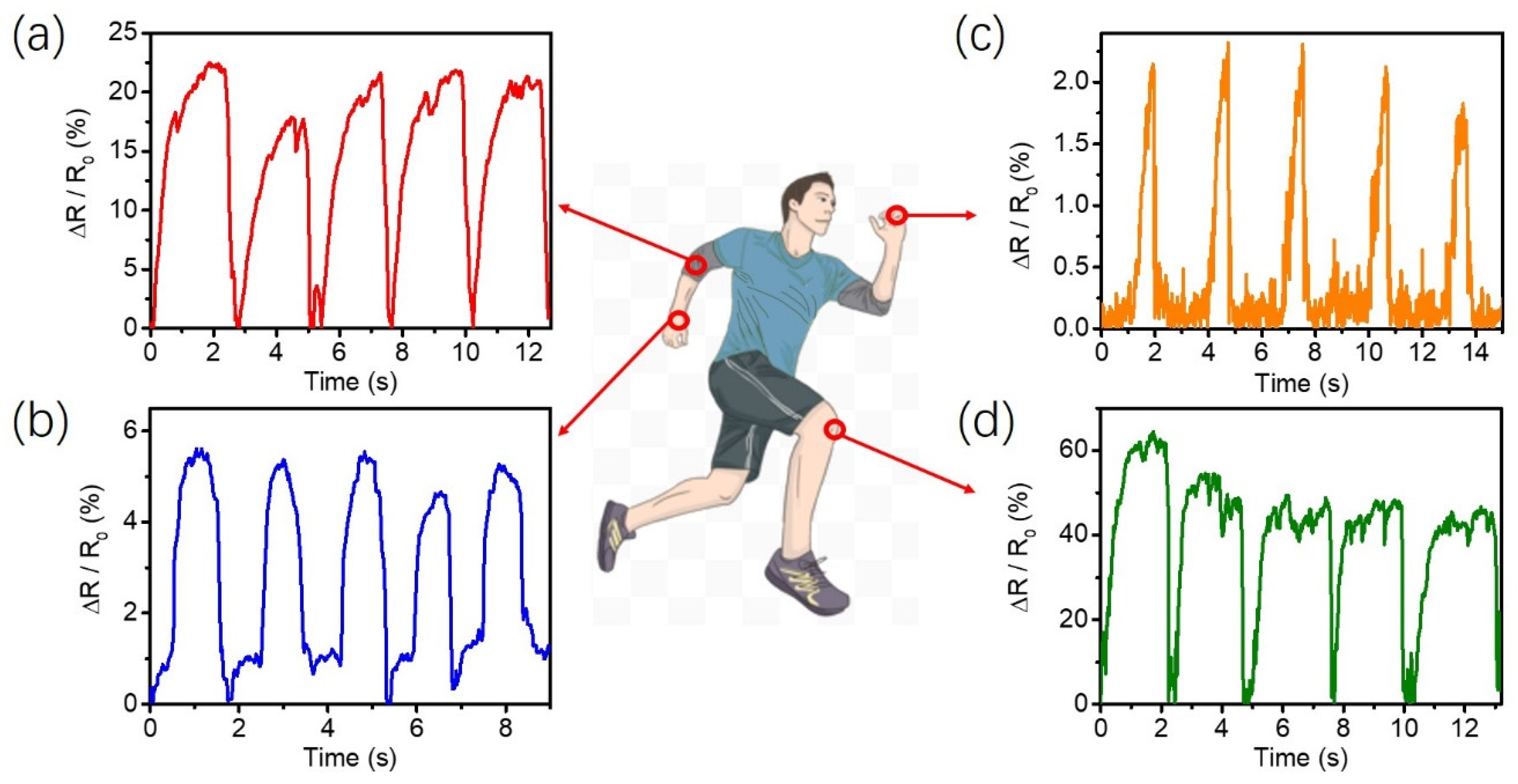

2.4. The Strain Sensing and Mechanism of PVA-PAA/PANi/[EMIM]TFSI Conductive Hydrogels

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of PVA-PAA/PANi/[EMIM]TFSI Conductive Hydrogels

4.2. Fabrication of the Strain Sensor Based on PVA-PAA/PANi/[EMIM]TFSI Hydrogels

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, J.C.; Mun, J.; Kwon, S.Y.; Park, S.; Bao, Z.; Park, S. Electronic Skin: Recent Progress and Future Prospects for Skin-Attachable Devices for Health Monitoring, Robotics, and Prosthetics. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1904765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Jian, M.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y. Carbonized Silk Nanofiber Membrane for Transparent and Sensitive Electronic Skin. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1605657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentz, F.; Mohammadi, M.; Tybrandt, K.; Berggren, M.; Arvidsson, R.; Rahmanudin, A. Integrating environmental assessment into early-stage wearable electronics research. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 19983–19999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shao, Y.; Yu, Y. Percolation networks in stretchable electrodes: Progress and perspectives. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 16904–16928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Yao, Y.; Wu, L.; Xue, Y.; Shen, G.; Guo, C.; Du, B.; Wu, H.; Jin, Y. Design principles of electroluminescent devices based on different electrodes and recent advances toward their application in textiles. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 8934–8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Fang, B.; Liu, Y.; Gao, W.; Zhao, P.; Wang, H.; Gao, C. Highly stretchable carbon aerogels. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, X.; Xin, Y.; Lubineau, G. Coaxial Thermoplastic Elastomer-Wrapped Carbon Nanotube Fibers for Deformable and Wearable Strain Sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1705591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, J.; Yang, S.; Li, B.; Huang, W.; Zeng, Z.; Hu, Y.; Gui, X. Flexible, conductive Cu-x@CNT films for ultra-broadband electromagnetic interference shielding and low-voltage electrothermal heating. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 18440–18449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Shi, G. High-Performance Strain Sensors with Fish-Scale-Like Graphene-Sensing Layers for Full-Range Detection of Human Motions. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 7901–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacquin, T.; Wanstall, S.; Park, I.; Stokes, A.A.; Heidari, H.; Lim, T.; Amjadi, M. Wearable, near temperature insensitive laser-induced graphene nanocomposite strain sensors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 20000–20012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perala, R.S.; Chandrasekar, N.; Balaji, R.; Alexander, P.S.; Humaidi, N.Z.N.; Hwang, M.T. A comprehensive review on graphene-based materials: From synthesis to contemporary sensor applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2024, 159, 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, K.; Rao, Z.; Zou, Z.; Ershad, F.; Lei, J.; Thukral, A.; Chen, J.; Huang, Q.-A.; Xiao, J.; Yu, C. Metal oxide semiconductor nanomembrane–based soft unnoticeable multifunctional electronics for wearable human-machine interfaces. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav9653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.S.; Kim, D.; Park, B.; Joh, H.; Woo, H.K.; Hong, Y.-K.; Kim, T.-i.; Ha, D.-H.; Oh, S.J. Multiaxial and Transparent Strain Sensors Based on Synergetically Reinforced and Orthogonally Cracked Hetero-Nanocrystal Solids. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1806714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Lee, D.W.; Jeong, H.Y.; Choi, J.-C.; Chung, S. Crosslinking site sharing-driven interface engineering to enhance adhesion between PDMS substrates and Ag–PDMS conductors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 21137–21144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Facchetti, A. Mechanically Flexible Conductors for Stretchable and Wearable E-Skin and E-Textile Devices. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1901408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, W.; Wang, X.; Pan, L.; Xu, B.; Xu, H. A Self-Healable, Highly Stretchable, and Solution Processable Conductive Polymer Composite for Ultrasensitive Strain and Pressure Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1705551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Guterman, T.; Adadi, N.; Yadid, M.; Brosh, T.; Adler-Abramovich, L.; Dvir, T.; Gazit, E. A Self-Healing, All-Organic, Conducting, Composite Peptide Hydrogel as Pressure Sensor and Electrogenic Cell Soft Substrate. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, N.; Rao, J.; Jia, S.; Su, Z.; Hao, X.; Peng, F. Ultrafast fabrication of organohydrogels with UV-blocking, anti-freezing, anti-drying, and skin epidermal sensing properties using lignin–Cu2+ plant catechol chemistry. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 14381–14391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Banerji, P. Polyaniline composite by in situ polymerization on a swollen PVA gel. Synth. Met. 2009, 159, 2519–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, J.; Al-Thani, N.J.; Madi, N.K.; Al-Maadeed, M.A. Effects of aniline concentrations on the electrical and mechanical properties of polyaniline polyvinyl alcohol blends. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yan, H.; Peng, Q.; Wang, R.; Barkey, M.E.; Jeon, J.W.; Wujcik, E.K. Ultrastretchable Conductive Polymer Complex as a Strain Sensor with a Repeatable Autonomous Self-Healing Ability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 20453–20464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Rastak, R.; Wang, Y.; Yan, H.; Feig, V.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, S.; Lian, F.; Molina-Lopez, F.; et al. Strain- and Strain-Rate-Invariant Conductance in a Stretchable and Compressible 3D Conducting Polymer Foam. Matter 2019, 1, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-Y.; Wang, M.-J. Removal of Heavy Metal Ions by Poly(vinyl alcohol) and Carboxymethyl Cellulose Composite Hydrogels Prepared by a Freeze–Thaw Method. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2830–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Liang, X.; Guo, J.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, L. Ultra-Stretchable and Force-Sensitive Hydrogels Reinforced with Chitosan Microspheres Embedded in Polymer Networks. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 8037–8044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoufei, N.; Wenling, Y.; Guibin, Z. PVA Porous Carrier Material Prepared by Gel-Chemical Cross-Linking Method. Plastics 2015, 3, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, J.M.; Carrillo, A.; Mota, M.L.; Ambrosio, R.C.; Aguirre, F.S. Purification and Glutaraldehyde Activation Study on HCl-Doped PVA(-)PANI Copolymers with Different Aniline Concentrations. Molecules 2018, 24, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakki, R.; Afzal Syed, M.; Kandadi, P.; Veerabrahma, K. Development of a self-microemulsifying drug delivery system of domperidone: In vitro and in vivo characterization. Acta Pharm. 2013, 63, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeel, M.; Yasin, G.; Arif, M.; Zhang, X.; Abbas, Z.; Khan, S.; Rehman, W.; Zaman, U.; Ul Haq Khan, Z.; Li, B. A facile band alignment with sharp edge morphology accelerating the charge transportation for visible light photocatalytic degradation: A multiplex synergy. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 32, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Gu, K.; Yao, J.; Shao, Z.; Chen, X. Poly(vinyl alcohol) Hydrogels with Integrated Toughness, Conductivity, and Freezing Tolerance Based on Ionic Liquid/Water Binary Solvent Systems. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 29008–29020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Shang, Y.; Shen, H.; Li, W.; Wang, Q. Highly transparent conductive ionohydrogel for all-climate wireless human-motion sensor. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 129865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, W.G.; Pires, B.M.; Thaines, E.H.N.S.; Pereira, G.M.A.; da Silva, L.M.; Freitas, R.G.; Zanin, H. Operando Raman spectroelectrochemical study of polyaniline degradation: A joint experimental and theoretical analysis. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mažeikienė, R.; Niaura, G.; Malinauskas, A. Red and NIR laser line excited Raman spectroscopy of polyaniline in electrochemical system. Synth. Met. 2019, 248, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trchová, M.; Morávková, Z.; Bláha, M.; Stejskal, J. Raman spectroscopy of polyaniline and oligoaniline thin films. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 122, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xing, L.; Shi, L.; Ran, R. Stable, Strain-Sensitive Conductive Hydrogel with Antifreezing Capability, Remoldability, and Reusability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 44000–44010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Lai, J.; Yan, B.; Liu, H.; Jin, X.; Ma, A.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, W.; Chen, W. Extremely stretchable and electrically conductive hydrogels with dually synergistic networks for wearable strain sensors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2018, 6, 9200–9207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Peng, Q.; Thundat, T.; Zeng, H. Stretchable, Injectable, and Self-Healing Conductive Hydrogel Enabled by Multiple Hydrogen Bonding toward Wearable Electronics. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 4553–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Pan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yao, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y. A large-strain weft-knitted sensor fabricated by conductive UHMWPE/PANI composite yarns. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2016, 238, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, H.; Yu, H.-Y.; Ouyang, Z.; Yao, J.; Krucinska, I.; Kim, D.; Tam, K.C. Highly sensitive self-healable strain biosensors based on robust transparent conductive nanocellulose nanocomposites: Relationship between percolated network and sensing mechanism. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 191, 113467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Hsieh, Y.-L. Conductive Polymer Protonated Nanocellulose Aerogels for Tunable and Linearly Responsive Strain Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 27902–27910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Cong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, T.; Nie, L.; Fu, J. Ultrastretchable Strain Sensors and Arrays with High Sensitivity and Linearity Based on Super Tough Conductive Hydrogels. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 8062–8069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, R.; Fu, J. Tough, Adhesive, Self-Healable, and Transparent Ionically Conductive Zwitterionic Nanocomposite Hydrogels as Skin Strain Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 3506–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Q.; Wang, S.; Zhai, W.; Shao, C.; Xu, L.; Yan, D.; Yang, N.; Dai, K.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Highly linear and low hysteresis porous strain sensor for wearable electronic skins. Compos. Commun. 2021, 26, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Yu, H.; Huang, G.; Wu, Q.; Ling, F.; Zhuang, Z.; Wang, H.; et al. Wide-range linear viscoelastic hydrogels with high mechanical properties and their applications in quantifiable stress-strain sensors. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 399, 125697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, C.; Xu, X. Linearly Responsive, Reliable, and Stretchable Strain Sensors Based on Polyaniline Composite Hydrogels. Gels 2025, 11, 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120966

He C, Xu X. Linearly Responsive, Reliable, and Stretchable Strain Sensors Based on Polyaniline Composite Hydrogels. Gels. 2025; 11(12):966. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120966

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Chubin, and Xiuru Xu. 2025. "Linearly Responsive, Reliable, and Stretchable Strain Sensors Based on Polyaniline Composite Hydrogels" Gels 11, no. 12: 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120966

APA StyleHe, C., & Xu, X. (2025). Linearly Responsive, Reliable, and Stretchable Strain Sensors Based on Polyaniline Composite Hydrogels. Gels, 11(12), 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120966