Abstract

Lichens are an important vegetative component of the Antarctic terrestrial ecosystem and present a wide diversity. Recent advances in omics technologies have allowed for the identification of lichen microbiomes and the complex symbiotic relationships that contribute to their survival mechanisms under extreme conditions. The preservation of biodiversity and genetic resources is fundamental for the balance of ecosystems and for human and animal health. In order to assess the current knowledge on Antarctic lichens, we carried out a systematic review of the international applied research published between January 2019 and February 2024, using the PRISMA model (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). Articles that included the descriptors “lichen” and “Antarctic” were gathered from the web, and a total of 110 and 614 publications were retrieved from PubMed and ScienceDirect, respectively. From those, 109 publications were selected and grouped according to their main research characteristics, namely, (i) biodiversity, ecology and conservation; (ii) biomonitoring and environmental health; (iii) biotechnology and metabolism; (iv) climate change; (v) evolution and taxonomy; (vi) reviews; and (vii) symbiosis. Several topics were related to the discovery of secondary metabolites with potential for treating neurodegenerative, cancer and metabolic diseases, besides compounds with antimicrobial activity. Survival mechanisms under extreme environmental conditions were also addressed in many studies, as well as research that explored the lichen-associated microbiome, its biodiversity, and its use in biomonitoring and climate change, and reviews. The main findings of these studies are discussed, as well as common themes and perspectives.

1. Introduction

Antarctica is the coldest continent on the planet, with average annual temperatures that can reach −10 °C on the Antarctic Peninsula and −50 °C in the interior of the continent. Precipitation and air relative humidity are low but can vary depending on proximity to coastal areas. The scarcity of organic matter, the low temperature and the presence of intense solar radiation are the main factors that limit life in Antarctica, but, unlike many species, lichens present high ecological plasticity and can tolerate extreme environmental conditions [1].

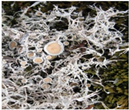

Traditionally, lichens are composite organisms with a mutualistic relationship between a heterotrophic mycobiont (i.e., a fungus) and an autotrophic photobiont (usually green algae and, in some cases, cyanobacteria), where this fungal lifestyle includes around 20% of all known fungal species [1]. Nevertheless, recent studies have verified that lichens are multi-symbionts, i.e., complex multi-species associations, including bacteria and other fungi, algae, and even yeasts and viruses [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. These bipartite or multipartite symbionts are the main vegetative component of the Antarctic terrestrial ecosystem, widely distributed in the continent and islands [8], which can be explained by their immense capacity to adapt to extreme environmental conditions.

Most lichens are extremely tolerant to desiccation and low temperatures, surviving for months to years in a state of cryptobiosis, and to UV radiation, because many of their diverse secondary metabolites act as UV filters [9,10,11]. However, the mechanisms by which lichens tolerate extreme stress are still not completely understood and have been the subject of several studies, most of them suggesting that these adaptations rely on the physiological integration of the symbionts [10,11]. This physiological integration favors the adaptation of lichens in different types of environments, from arid regions of hot climate to alpine and polar regions, beyond tropical areas, and they are recognized to colonize a diversity of substrates, such as tree trunks, rocks and soil, among others [4]. Due to these characteristics, lichens can possibly be good models for the study of astrobiology [12].

Lichens can also be considered relevant species in the biomonitoring of atmospheric pollution, as they can accumulate trace elements or metals from the air and/or soil, thus acting as environmental health markers [4,13]. They also act as climate indicators, as some can tolerate large fluctuations in climate, while others require more specific regimes [14,15,16,17,18]. Lichens may be vulnerable to global warming, as the respiratory demand of the mycobiont partner may increase, requiring an increase in the proportion of cells of the photobiont partners to allow for survival and carbon balance [19].

Omics technologies have allowed for the expansion of knowledge about the molecular and taxonomic composition of different types of lichens, as well as gene expression patterns under different ecological conditions [4,13,20,21]. However, due to the complexity of these symbiotic systems and problems related to the formation of chimeric contigs, many studies are attempting the sequencing of individual partners cultivated axenically, although this approach cannot reveal the complete diversity of symbionts [7]. The virome of lichens may also contribute to multiple functions of the symbiotic system, although very little is known about viruses that infect components of these organisms [4].

Many secondary metabolites are produced by fungi, but other microorganisms that compose the symbiotic system are able to produce compounds with biotechnological value, and this characteristic makes the exploration of the lichen microbiome much more interesting [22,23]. The ability of lichen-forming fungi to produce antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer compounds and enzymes with diverse biotechnological applications has been investigated over the years, as has the ability of many symbiotic bacteria that make up lichens to produce bioactive compounds, especially with antimicrobial activity [24].

Given the global scenario of climate change and anthropogenic impact, emerging disease spread, and the need to develop new inputs for health, lichen research in the Antarctic ecosystem can present a promising approach both for environmental health and prospection for new molecular targets and biotechnological development in the field of health.

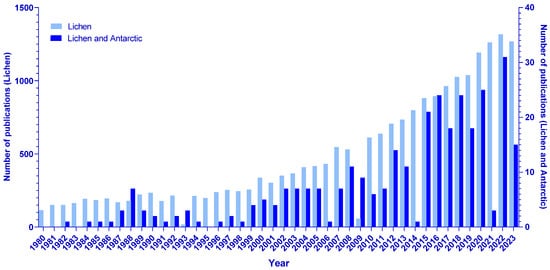

Research on lichens has increased considerably in the last 23 years, according to the PubMed database, and, following this trend, the same increase can be seen for research on lichens related to the Antarctic continent (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of publications in the PubMed database from January 1980 to December 2023 that include the descriptor “lichen” (light blue, with scale on the left); number of publications on lichens related to Antarctic ecosystems in the PubMed database from January 1980 to December 2023, including the descriptors “lichen” and “Antarctic” (dark blue, with scale on the right).

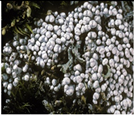

Antarctica is a continent with unique characteristics which has numerous natural resources that need to be preserved. Studies have reported more than 380 species of lichens on the Antarctic continent, with many new species recently described, including Tephromela Antarctica, Umbilicaria Antarctica and Usnea Antarctica, and at least 31 endemic species of the genera Acarospora, Amandinea, Buellia, Leptogium, Pertusaria and Tetramellas [25].

However, anthropogenic actions and global warming may affect this biodiversity, leading to ecosystem imbalances, with unpredictable impacts, such as increase, reduction or extinction of native species. Our review of lichen research in the Antarctic ecosystem over the past five years allowed us to identify trends and perspectives in the study of these organisms, as well as knowledge gaps that can be filled in the coming years, taking into account possible implications for the areas of clinical and environmental health.

2. Methods

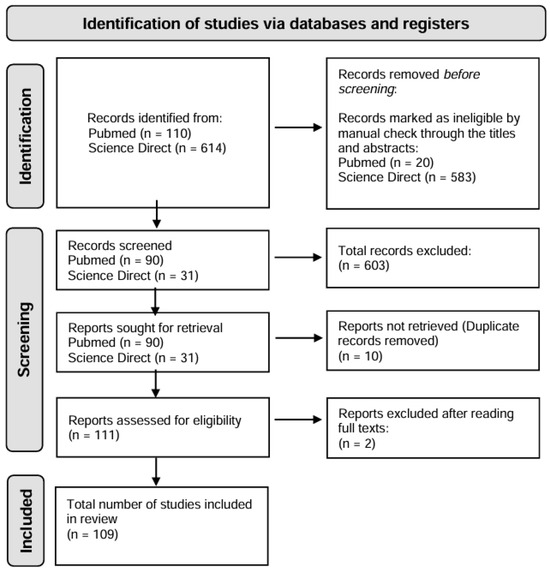

The present study is a literature review based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) model [26] (Figure 2). The PubMed and ScienceDirect databases were used to collect publications, using the descriptors “lichen” and “Antarctic”. The research was carried out considering the last 5 years (January 2019 up to February 2024).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of selection steps for studies related to lichen research in Antarctic ecosystem (January 2019 to February 2024).

This study included original research articles, short communications and reviews that addressed lichen research in the Antarctica ecosystem to evaluate the highlighted themes and research that have been prioritized by the conducting institutes, universities and government agencies, among others, in the last several years. Book and encyclopedia chapters, conference abstracts and news articles were not included in this review. Related articles that used meta-analysis data from the literature or discussed relationships between lichens and their symbiotic associations on the global scale in which the Antarctic continent was cited were also included in the analysis. For the selection of articles related to this area of study, the appearance of key terms was considered only in the fields of title and abstract. After reading the abstracts, articles that presented results or discussion about lichen research in Antarctica were included, thereby reducing the recovery of documents that contained the key terms casually but did not present any relation to the scope of this review. Duplicate articles, articles that were not related to the research theme and publications in other languages than English were also excluded from the study.

3. Results

The search in the databases retrieved 110 publications from PubMed and 614 from ScienceDirect, and, after reading the titles and abstracts, we selected 121 texts that addressed the topic more closely. After duplicate removal and full-text scrutiny, 109 publications were considered eligible for the preparation of the review, according to the flowchart in Figure 2.

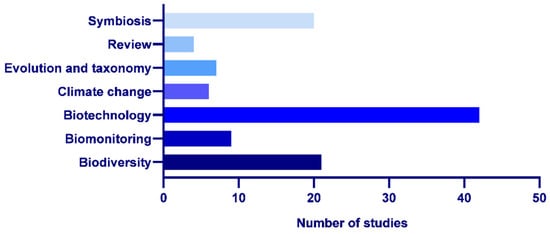

The articles involving research on lichens in Antarctic ecosystems could be classified according to the main scope of the analysis, which we divided into the following themes: (i) biodiversity, ecology and conservation; (ii) biomonitoring and environmental health; (iii) biotechnology and metabolism; (iv) climate change; (v) evolution and taxonomy; (vi) reviews and (vii) symbiosis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Number of studies included by thematic area (January 2019–February 2024).

Biotechnology and metabolism (38.5%) was the area with a higher number of studies in the last several years, followed by biodiversity, ecology and conservation (19%); symbiosis (18.5%); biomonitoring and environmental health (8.5%); evolution and taxonomy (6.5%); climate change (5.5%); and reviews (3.5%) (Figure 3).

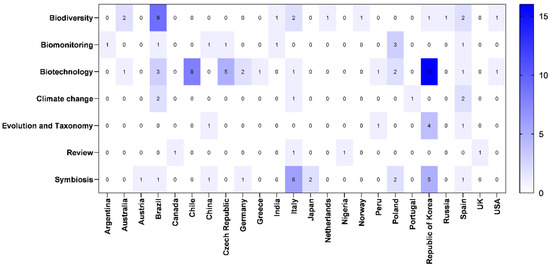

Figure 4 shows the distribution pattern, in percentages, of articles according to the country of origin of the first author.

Figure 4.

Heatmap showing the number of studies according to the country of the first author involved in lichen research in the Antarctic ecosystem by thematic area (January 2019–February 2024). Data spanned from white (low number of articles) to dark blue (higher number of articles), as illustrated by the color scale in the bar.

The countries with the highest number of studies related to lichen research on the Antarctic continent published in the last five years included the Republic of Korea (23.8%), Brazil (14.5%), Italy (10%), Chile (7%), Spain (7%), Poland (6.5%) and the Czech Republic (5.5%). Other countries accounted for less than 3% of the total number of studies on this topic during this period (Figure 4). Many studies were carried out in collaborations involving different countries; therefore, some countries traditionally associated with research on the Antarctic continent [27] may not have appeared on this list (Figure 4). In any case, it is interesting to observe the interest of some South American countries in lichen research on the Antarctic continent (Figure 4).

A greater number of articles were related to research involving the potential of lichens in biotechnological applications. Research involving metabolomics and the description or discovery of secondary metabolites with potential antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, cytotoxic or cytoprotective activities and protein inhibition too k the lead. Table 1 presents a list of the lichens, the secondary metabolites or bioactive compounds, and the potential biotechnological applications studied in these publications.

Table 1.

Compounds with bioactive properties extracted from Antarctic lichens with potential biotechnological and health applications (data obtained from the literature: 2019–2024).

Some of the studies in the field of biotechnology and metabolism also involved research on metabolites in endolithic communities [3]. Mechanisms of activation and/or photoinhibition of photosynthesis under natural and laboratory conditions have also been explored in some eco-physiological studies using fluorescence and spectroscopy techniques [9,10,11,57,58,59,60,61,62].

Species composition, diversity and spatial coverage patterns were included in the thematic area of biodiversity, ecology and conservation [63,64,65,66,67,68,69]. The use of automated or semi-automated methods, such as semi-automatic object-based image analysis, remote sensing and satellite imagery, have been used to monitor the distribution patterns, productivity and biodiversity of lichens in Antarctica [68,70,71,72,73,74,75,76].

Articles addressing the theme of symbiosis involved the prospection of microbial communities (bacteria, yeasts, algae and fungi) that live in association with Antarctic lichens [16,52,54,56,77,78,79,80,81]. Many of these studies used metagenomic assays targeting 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing to explore the diversity of microbial communities, while others used whole- genome sequencing techniques to better understand their mechanisms of evolution [20,21]. Several studies aimed at characterizing these symbiotic microbial communities under different environmental conditions, considering the influence of different physicochemical parameters on their composition and functional profiles [2,5,6,7,15,16,48,50,52,80,82,83,84,85,86,87].

Studies using lichens as bioindicators of environmental contamination or in investigations into the sequestration of toxic compounds (e.g., novel brominated flame retardants), trace elements, metals and radionuclides were classified under the theme of biomonitoring and environmental health [88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95].

Although the topic of climate change is in the spotlight, few studies [15,17,18,96,97] could be classified in this area, although articles focusing on other themes sometimes included discussions of the future impact of their research on the issues of global warming and water scarcity. Perhaps the absence of consistent and verified data and the difficulty in carrying out long-term studies are reasons why studies directly related to climate change impacts on Antarctic biodiversity are scarce.

In evolution and taxonomy, studies involving population structure, gene flow, dating analyses, genealogical reconstruction methods, and phylogenetic analyses using molecular markers or target rDNA sequencing, aiming to establish the taxonomy of bacteria, fungi and algae symbionts in lichens, were observed [1,5,7,52,79,98].

A summary of the most frequently reported lichen species and their locations of occurrence can be consulted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lichen species observed in the Antarctic region (2019–2024). Species/location/reference.

Checklists on the diversity of lichen species already described on the Antarctic continent can be consulted in several references [16,25,65,99].

Finally, we observed a smaller number of reviews published in this period, covering topics such as biodiversity protection, survival mechanisms under extreme conditions and pharmacological potential [15,25,100,101].

4. Discussion

4.1. General Aspects

A trend of increasing interest in lichen research on a global scale and on the Antarctic continent was observed through a search for articles published in the last several years in databases that compiled relevant scientific productions from the selected period. The search for articles using the generic term “lichen” in the Pubmed database resulted in 19,431 items over the last 23 years (1980 to 2023), with a trend of expressive increase in research on the topic in the last 10 years. The same trend could be observed for lichen research on the Antarctic continent searched for using the descriptors “lichen” and “Antarctic”, which resulted in 315 articles published in the last 23 years, with a significant percentage made available in the last 10 years.

This review also showed that there is a tendency towards an increase in research related to the identification of metabolites with potential biotechnological applications. Due to the peculiar characteristics of the Antarctic continent, native or endemic species can represent potential sources for the discovery of new molecules, mainly applicable in the health sector.

No less important were studies on biodiversity conservation and long-term monitoring to assess the impact of anthropogenic activities on this biodiversity, including the global climate change scenario. The balance of ecosystems depends on maintaining Earth’s biodiversity, and this topic is also relevant to the researchers’ goals. Knowledge of lichens as symbiotic systems reveals that the diversity of associated microorganisms and their abundance can be variable depending on different abiotic gradients of the ecosystem. Therefore, it is necessary to study this microbial diversity in the face of the harsh climate and discover new microorganisms, genes and metabolic routes that, ultimately, could result in applied biotechnology research.

In this regard, it is not surprising that countries that are investing heavily in research and development and in the biotechnology industry, such as South Korea (the Republic of Korea) [102], are prominent in Antarctic research. There is also an expressive participation in research on lichens by developing countries in the South Atlantic and/or Latin American countries. Countries with greater geographic proximity to the Antarctic continent can be more directly affected by the consequences of environmental changes in this ecosystem, including disturbances caused by global warming, ecological imbalances, and the emergence or re-emergence of new or unknown pathogens. Advances in the technological capabilities of these countries to monitor the effects of anthropogenic impacts on Antarctic biodiversity may be boosting research in this field.

4.2. Secondary Metabolites and Potential Biotechnological Applications

Undoubtedly, lichens represent a rich source of bioactive molecules, which makes them interesting objects for the study of possible applications in the medical and biotechnological fields. In Antarctica, the potential for exploring new molecules or enzymes obtained from lichen extracts is promising given the unique characteristics of this ecosystem and the survival of several still unknown species.

Secondary metabolites of lichen have been shown to possess biological activities, such as antioxidant, analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties, amongst others [103]. Efforts toward the development of new drugs based on natural products are increasing worldwide [39,103,104], in part due to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens and new diseases, in addition to well-known diseases for which there are still no effective treatments, and the need to replace current medications due to toxicity or side effects associated with their use [39,104,105,106].

Lichen secondary metabolites have been widely studied using high-resolution chromatography (HPLC) techniques coupled to mass spectrometry (MS), and some studies have indicated that there are more than 1000 bioactive compounds currently registered [35,36,105]. The main metabolites studied in terms of biological activity include those derived from the acetyl– malonate pathway, such as depsides (e.g., atranorin), depsidones (e.g., salazinic acid) and dibenzofurans (e.g., usnic acid) [105,106]. The latter classes were shown to have anti-inflammatory activity and were able to inhibit the mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines and mediators using a zebrafish larval model [28].

Antioxidant and cholinesterase inhibitory activities of these compounds have been demonstrated in recent metabolomic studies and may be promising for the treatment of diseases related to oxidative stress, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and metabolic syndromes, such as diabetes mellitus [30,34,35].

Several other studies have shown the antioxidant activity and enzyme inhibitory potential of lichen ethanolic extracts, such as Areche et al.’s study [32] on Himantormia lugubris from Antarctica, in which the antioxidant activity and enzyme inhibitory potential (against cholinesterase and tyrosinase) of such extracts were observed. They detected 28 metabolites that showed enzymatic inhibitory activity. Since the inhibition of cholinesterase enzymes could play a role in the therapy of Alzheimer’s disease, these results illustrate the potential of this phenolic-enriched lichen to produce an extract with properties that can be used in neurodegenerative or related chronic nontransmittable diseases [32].

Ethanolic compounds present in extracts of Cladonia chlorophaea and C. gracilis species and their antioxidant activity and anti-inflammatory potential against pathologies such as asthma and other inflammatory disorders, such as allergic rhinitis and rheumatoid arthritis, have also been investigated [30]. Antarctic lichens, such as Umbilicaria Antarctica, Cladonia cariosa and Himantormia lugubris, can also produce compounds with inhibitory activity against tau protein, which is related to Alzheimer’s disease, in addition to other neurodegenerative disorders named tauopathies [31,41].

At present, there are many in vivo and in vitro experiments that have studied the anticancer effect of lichens [23,40,104]. Different species of lichens have demonstrated effects on lung cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer, melanoma, colon cancer, liver cancer, leukemia, cervical cancer, rectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, lymphatic cancer, glioblastoma, astrocytoma and other cell lines [44,103]. The anticancer activities are attributed to cytotoxic action, cell cycle regulation, antiproliferation, anti-invasiveness, antimigration, antiangiogenesis, telomerase inhibition and inhibition of endothelial tube formation, among other pathways [39,104].

The genus Usnea also appears promising for the investigation of phenolic extracts and its potential antioxidant and antitumor activities, for example, its activity against melanoma [44]. Melanoma is a skin tumor and is related to excessive exposure of the skin to ultra-violet (UV) light. The UV radiation in Antarctica is very intense, and some organisms produce compounds that can absorb this radiation as a defense mechanism, as has been observed for several species of lichens that can produce relevant secondary metabolites that act in this protection [44].

Usnic acid, found in the genus Usnea, is one of the most abundant secondary metabolites with possible use in the treatment of various diseases, such as diarrhea, ulcers, urinary tract infections, tuberculosis and pneumonia, among others [44]. Vega-Bello et al. [44] identified usnic acid as the main metabolite present in the Antarctic lichen Usnea aurantiaco-atra and that the levels of this compound are much higher than those identified in other species of the same genus, such as U. barbata. High levels of this metabolite could be related to the environmental and climatic conditions in which lichens develop.

In addition to antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities, many substances produced by lichens, such as usnic acid, salazinic acid, evernic acid, protolichesterinic acid, isodivaricatic acid and divaricatinic acid, have been found to inhibit microbial pathogens, including bacteria, fungi and viruses [103]. Two new depsidones, himantormiones A and B (1 and 2), were isolated and identified from the Antarctic lichen Himantormia lugubris (Parmeliaceae) [33]. The isolated compounds were tested for antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities, and himantormione B (2) exhibited an inhibitory effect against Staphylococcus aureus [33]. Lee et al. [37] also discovered two new metabolic compounds isolated from Ramalina terebrata, collected from King George Island, Antarctica, in January 2021. The new compounds (stereocalpin B, a new cyclic depsipeptide, and a new dibenzofuran derivative) were tested for antimicrobial activities against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Candida albicans and Mycobacterium smegmatis, but moderate antimicrobial activity was only observed against E. coli [37].

Other studies have demonstrated that a methanol– acetone extract—a crude extract from the Antarctic lichen Usnea aurantiaco-atra—shows antibacterial activity against S. aureus at a low concentration, and there is at least one bioactive compound that confers this activity [107]. This work also compared two species of lichens (U. aurantiaco-atra and U. Antarctica) and demonstrated that U. aurantiaco-atra presented greater cytotoxic and antibacterial activity than U. Antarctica, demonstrating the potential of this species for the isolation of antibacterial compounds in the Antarctic ecosystem [107].

Knowledge of the microbiome, genes and metabolic routes of symbiont microorganisms, such as yeasts and bacteria, has been explored in some studies [20,22,51,56,108], and potential applications of substances or enzymes have been highlighted for the detergent, food and biofuel industries and for the bioremediation of emerging contaminants.

Although lichen extracts have potential for the treatment of several diseases, some authors have pointed out the need to develop bioassay-guided fractionation and further isolation of minor compounds from crude extracts to accurately determine the bioactive compounds responsible for therapeutic activities that have been derived from these Antarctic species [32,44,51].

4.3. Physiological Properties and Survival in Extreme Environments

Unlike vascular plants, which have stomata or cuticles in their outer layers that help control water balance, lichens do not have the ability to regulate their water content [4]. Therefore, at first sight, one would assume that lichens would be quite sensitive to the extreme climatic conditions and low relative air humidity that are found in Antarctica. However, they have a poikilohydric lifestyle which enables them to survive extreme weather conditions for long periods in a dormant state [16]. In this review, we identified several studies that discuss survival and adaptation mechanisms of lichens in hostile environments, including resistance to alternating desiccation/rehydration cycles [9,10]. These investigations are particularly relevant for understanding the mechanisms and strategies for evolution and stress tolerance in conditions such as the absence of light, desiccation, low or high temperatures, and water scarcity. In lichens, physiological studies involving the photosynthetic apparatus and its protective mechanisms against extreme conditions have been reported [10,11].

Many of these studies verified the kinetics of hydration-induced activation of photosynthesis and often included analyse s of the activation or deactivation of photosynthesis under different conditions of light, water stress and hydration intervals at specific times [9,10,57]. Antarctic lichens, such as Cladonia gracilis, C. borealis, Dermatocarpon polyphyllizum, Himantormia lugubris, Leptogium puberulum, Umbilicaria Antarctica, Usnea aurantiaco-atra and Xanthoria elegans, have been tested in such experiments [9,10,11,57,60,62]. Most studies concluded that extremophile lichens have a mechanism to protect the chloroplastic apparatus of photobiont partners, especially when the water content is below 20% [9,10,60].

Resistance to dehydration is an advantageous strategy and could even be applicable in conditions outside Earth, such as in outer space, which, in addition to severe dehydration, is characterized by a vacuum and a broader spectrum of irradiation [58,109]. Therefore, researchers are also investigating the behavior of residual water in thallus through advanced techniques such as relaxometry, spectroscopy and sorption isotherm analysis, expanding research in the fields of biotechnology and astrobiology [12,109,110]. Some lichen species can produce large amounts of hydrogen, even after being exposed to extreme conditions, such as high doses of UVB radiation and very low or high temperatures (−196 °C and/or +70 °C, respectively) [12]. An international and interdisciplinary consortium (BIOMEX) has analyzed several groups of organisms, including Buellia frigida, an endemic Antarctic lichen, in experiments in outer space and under simulated space conditions [58,111]. Preliminary results demonstrated that a significative percentage of the tested lichens can survive in extreme conditions but a re sensitive to different doses of irradiation [58]. The lichen B. frigida also seems to be sensitive to outer space conditions, especially due to the DNA damage observed under these conditions [111]. Therefore, there is still a large gap in knowledge on this topic, and scientists need to better understand the adaptation and resistance mechanisms of different lichen species under adverse conditions in outer space.

4.4. Biodiversity and Environmental Health

In the field of biodiversity, ecology and conservation, some studies evaluated the changes in associated communities of mosses– lichens along a pedoenvironmental gradient, i.e., how species diversity (richness, species composition and beta diversity) are related to physical–chemical parameters and the organic matter and water content of soil. Some authors have also demonstrated that the distribution of species can be affected by the presence of penguin, elephant seal and seabird colonies because the se species can influence nitrogen concentrations and the circulation of pollutants in the Antarctic ecosystem [63,112,113,114,115]. Collections from large areas, taxonomic analysis and plant inventory data have also been used to monitor biodiversity [25,64,65,69], and analysis of photographs has been performed to calculate plant community coverage of sampled areas over time [70,74].

The use of automated or semi-automated methods is especially valuable in Antarctica, as access is limited and conditions are extreme. Furthermore, climate change can affect the Antarctic ecosystem, interfering with the coverage and distribution patterns of different species of lichens, mosses and other species of native fauna and flora. Therefore, it is essential to detect biodiversity trends to understand how changes may affect these communities. In this regard, several recent studies have used remote sensing and lichen spectra and/or satellite pictures to evaluate the surface reflectance profile patterns for Antarctic biological soil crusts (algae, lichens and mosses), generating vegetation cover distribution maps that can be monitored over time [67,68,70,71,72,73,75,76]. Due to the increasing anthropogenic impacts in the region, Phillips et al. [66] suggested that a greater number of Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs) be adopted, considering the habitats and the patterns of occurrence and distributions of species as parameters for the establishment of protection areas [66].

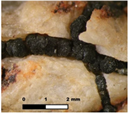

The discovery of a variety of microorganisms that compose the symbiotic system of lichens and the characterization of the functional profiles of these communities was the third theme in evidence. Emphasis ha s been given to endolithic communities (found inside or embedded in rocks), a recent increase in the number of reports on which has been observed [2,3,6,15,79,81,85,86]. Lichen-forming fungal species were found in c ontinental Antarctica endoliths, revealing that these habitats may favor colonization by these symbiotic species in the most extreme climatic conditions [116,117]. The most abundant bacterial phyla identified from most of the lichen species analyzed in the studies were Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria and Actinobacteria, with variations in this abundance depending on the geographic characteristics of the areas and the substrates from which they were collected [2,47,52,82,85,117]. In summary, in most studies, the functional profiles of communities vary according to geographic regions and variable environmental conditions, such as altitude, spatial distance, sun exposure, temperature, humidity, soil organic matter content, deglaciation time and microclimatic conditions, in the case of lichen thallus parts [2,5,7,15,50,52,77,82,83,84,85,116,117]. Shrestha et al. [21] also identified CRISPR-Cas loci in the complete genomes of a lichen-associated Burkholderia sp. which may reveal different infection mechanisms in lichens. New Antarctic lichen-associated bacteria species have also been described [49,52,53].

In the area of biomonitoring and environmental health, the accumulation of radionuclides (90Sr, 137Cs, 238,239+240Pu and 241Am), selected natural radionuclides (40K, 230,232Th and 234,238U), trace elements (mainly Sm, La, Sc, Fe, Co, Hg and Ca), trace metals (Cd), and organic contaminants such as aliphatic hydrocarbons (e.g., petroleum and its by-products) in lichens (for example, Usnea Antarctica) has been addressed in some studies [89,90,91,92,93,94,95,97], and contamination levels have been found to vary according to whether locations are more or less impacted by human action, or influenced by glacier melt and penguin guano. In general, lichens are considered good biomarkers to evaluate the presence of these elements in the Antarctic ecosystem. Given the growing anthropogenic impact in the region from scientific, tourism and fishing activities, there is an increased expectation that lichens will be used in the biomonitoring of environmental health conditions.

Meta-analyses and field studies involving the identification of different species of lichens in specific localities and different climatic conditions have revealed that the macroclimate is the main driver of species distribution, making certain species useful as bioindicators of climatic conditions and, consequently, for assessing the consequences of climate change [2,14,16,17,18,19,118]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has pointed to current global warming trends that could cause a rise in ocean levels, the loss of sea and land ice, and, consequently, negative impacts on global health and biodiversity [19,118]. Given the importance of this topic, especially considering the impact of climate change on Antarctic biodiversity and topics related to One Health (an approach that considers the integration between human, animal, plant and environmental health), it is expected that more studies will be conducted to characterize the diversity of lichens under climate change in this ecosystem.

4.5. Final Considerations

In recent years, research on lichens from the Antarctic continent has demonstrated that there is growing scientific interest in the discovery of new metabolites and their biotechnological applications, especially for human health and the production of new drugs for the treatment of infectious, metabolic, neurodegenerative and cancer diseases. As lichens are organisms formed by a symbiotic association involving multiple microorganisms, knowledge of the microbiome can help to elucidate distribution patterns and metabolic profiles, as well as the contribution of each partner to essential functions for survival in the most diverse and extreme environments on the planet.

The search for molecules and substances produced by lichens with bioactive properties is not new, but it has intensified in recent years because of technological advances and the interest in discovering new drugs that could, to some extent, be promising substitutes for synthetic drugs. Despite their potential, unique metabolites produced by lichens have received less attention by the pharmaceutical industry due to their slow growth and low biomass availability and the technical challenges involved in their artificial cultivation [119]. However, mass spectrometry-based metabolomics is a promising tool to detect and identify small molecules produced by the lichen microbiome and to understand the functional role of these microbial metabolites. The advancement of molecular engineering and synthetic biology could revolutionize the way medicines and other medical supplies are produced [119].

Often, secondary metabolites in extracts are explored through direct detection using HPLC and MS, but an alternative approach makes use of comparative genomics (“genome mining” strategies), which allows tracking of genes that encode proteins and families of genes and pathways that result in metabolites of interest [120]. The recent development of omics technologies linked to synthetic biology can assist in the expression of heterologous proteins using culturable hosts to provide specialized metabolites in a sustainable way [106,107,119]. This is particularly relevant, as the preservation of natural resources is imperative. Genetic engineering systems, when carefully controlled, can minimize the problem of overexploitation and extractivism and support the conservation of biological and genetic resources for future generations.

Environmental changes will have significant direct impacts on ecosystems. Considering the increase in the discharge of pollutants and the intensification of climate change, it is important to monitor and evaluate the effects of these changes on Antarctic biodiversity so that we have information that can guide the management and conservation of this territory, minimizing negative impacts on human, animal and environmental health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.P., W.M.S.D. and G.F.D.; methodology, T.P.; investigation, T.P., W.M.S.D. and G.F.D.; validation and visualization, T.P., W.M.S.D. and G.F.D.; writing—original draft, T.P.; writing—review and editing, T.P., W.M.S.D. and G.F.D.; supervision and project administration, W.M.S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was received from the Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro—FAPERJ [process: 203.530/2023].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data obtained for lichen figures can be consulted through the following websites: https://guatemala.inaturalist.org/; the Consortium of Lichen Herbaria (lichenportal.org); Wikipedia3; BioDiversity4All4 (https://www.biodiversity4all.org/login); Antarctica NZ5 (https://www.antarcticanz.govt.nz/). Accessed on 1 March 2024. All the material included in this article is licensed under a Creative Commons International License.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the FIOANTAR Working Group (https://fioantar.fiocruz.br/equipe, accessed on 1 March 2024), the Brazilian Antarctic Program—PROANTAR, the Vice-Presidency of Production and Innovation in Health (VPPIS) and the Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro—FAPERJ [process: 203.530/2023]. G.F.D. thanks UFRJ for the assignment granted to Fiocruz to participate as a collaborating researcher in the FioAntar Project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cho, M.; Lee, S.J.; Choi, E.; Kim, J.; Choi, S.; Lee, J.H.; Park, H. An Antarctic lichen isolate (Cladonia borealis) genome reveals potential adaptation to extreme environments. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleine, C.; Stajich, J.E.; Pombubpa, N.; Zucconi, L.; Onofri, S.; Canini, F.; Selbmann, L. Altitude and fungal diversity influence the structure of Antarctic cryptoendolithic bacteria communities. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2019, 11, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, G.; Coleine, C.; Gevi, F.; Onofri, S.; Selbmann, L.; Timperio, A.M. Metabolomics of dry versus reanimated Antarctic lichen-dominated endolithic communities. Life 2021, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, M.; Grube, M.; Schiefelbein, U.; Zühlke, D.; Bernhardt, J.; Riedel, K. The lichen´s microbiota, still a mystery? Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 623839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yan, D.; Ji, Z.; Chen, X.; Yu, L. A comprehensive assessment of fungal communities in various habitats from an ice-free area of Maritime Antarctica: Diversity, distribution, and ecological trait. Environ. Microbiome 2022, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canini, F.; Borruso, L.; Newsham, K.K.; D’Alò, F.; D’Acqui, L.P.; Zucconi, L. Wide divergence of fungal communities inhabiting rocks and soils in a hyper-arid Antarctic desert. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 25, 3671–3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Casanova-Katny, A.; Gerasimova, J. Metabarcoding of Antarctic lichens from areas with different deglaciation times reveals a high diversity of lichen-associated communities. Genes 2023, 14, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.K.; da Silva, A.V.; Fernandez, P.M.; Montone, R.C.; Alves, R.P.; de Queiroz, A.C.; de Oliveira, V.M.; dos Santos, V.P.; Putzke, J.; Rosa, L.H.; et al. Extracellular hydrolytic enzymes produced by yeasts from Antarctic lichens. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2022, 94 (Suppl 1), e20210540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.B.; Vítek, P.; Mishra, A.; Hájek, J.; Barták, M. Chlorophyll a fluorescence and Raman spectroscopy can monitor activation/deactivation of photosynthesis and carotenoids in Antarctic lichens. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 239, 118458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednaříková, M.; Váczi, P.; Lazár, D.; Barták, M. Photosynthetic performance of Antarctic lichen Dermatocarpon polyphyllizum when affected by desiccation and low temperatures. Photosynth. Res. 2020, 145, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barták, M.; Hájek, J.; Halıcı, M.G.; Bednaříková, M.; Casanova-Katny, A.; Váczi, P.; Puhovkin, A.; Mishra, K.B.; Giordano, D. Resistance of primary photosynthesis to photoinhibition in Antarctic lichen Xanthoria elegans: Photoprotective mechanisms activated during a short period of high light stress. Plants 2023, 12, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriatzi, A.; Tzivras, G.; Pirintsos, S.; Kotzabasis, K. Biotechnology under extreme conditions: Lichens after extreme UVB radiation and extreme temperatures produce large amounts of hydrogen. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 342, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eymann, C.; Lassek, C.; Wegner, U.; Bernhardt, J.; Fritsch, O.A.; Fuchs, S.; Otto, A.; Albrecht, D.; Schiefelbein, U.; Cernava, T.; et al. Symbiotic interplay of fungi, algae, and bacteria within the lung lichen Lobaria pulmonaria L. Hoffm. as assessed by state-of-the-art metaproteomics. J. Proteome. Res. 2017, 16, 2160–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancho, L.G.; Pintado, A.; Green, T.G.A. Antarctic studies show lichens to be excellent biomonitors of climate change. Diversity 2019, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleine, C.; Stajich, J.E.; de Los Ríos, A.; Selbmann, L. Beyond the extremes: Rocks as ultimate refuge for fungi in drylands. Mycologia 2021, 113, 108–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Brunauer, G.; Bathke, A.C.; Cary, S.C.; Fuchs, R.; Sancho, L.G.; Türk, R.; Ruprecht, U. Macroclimatic conditions as main drivers for symbiotic association patterns in lecideoid lichens along the Transantarctic Mountains, Ross Sea region, Antarctica. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, J.; Rodríguez, A.; Fangueiro, D.; De Los Ríos, A. In-situ soil greenhouse gas fluxes under different cryptogamic covers in Maritime Antarctica. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 144557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannone, N.; Malfasi, F.; Favero-Longo, S.E.; Convey, P.; Guglielmin, M. Acceleration of climate warming and plant dynamics in Antarctica. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 1599–1606.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colesie, D.; Walshaw, C.V.; Sancho, L.G.; Davey, M.P.; Gray, M. Antarctica’s vegetation in a changing climate. Adv. Rev. 2022, 14, e810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.R.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, B.; Chi, Y.M.; Kang, S.; Park, H.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Oh, T.J. Complete genome sequencing of Shigella sp. PAMC 28760: Identification of CAZyme genes and analysis of their potential role in glycogen metabolism for cold survival adaptation. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 137, 103759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, P.; Han, S.R.; Lee, J.H.; Park, H.; Oh, T.J. A computational approach to identify CRISPR-Cas loci in the complete genomes of the lichen-associated Burkholderia sp. PAMC28687 and PAMC26561. Genomics 2021, 113, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, N.; Kim, B.; Lee, C.M.; Oh, T.J. Comparative genome analysis among Variovorax species and genome guided aromatic compound degradation analysis emphasizing 4-hydroxybenzoate degradation in Variovorax sp. PAMC26660. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, M.H.; Kim, E.J.; Lee, J.H.; Han, S.J.; Lee, Y.M.; Lee, S.; Youn, U.J. Cyclic dipeptides and alkaloids from the rare actinobacteria Streptacidiphilus carbonis isolated from Sphaerophorus globosus (Huds.) Vain. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2023, 110, 104709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.T.; Parrot, D.; Berg, G.; Grube, M.; Tomasi, S. Lichens as natural sources of biotechnologically relevant bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So, J.E.; Halda, J.P.; Hong, S.G.; Hur, J.S.; Kim, J.H. The revision of lichen flora around Maxwell Bay, King George Island, Maritime Antarctic. J. Microbiol. 2023, 61, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Page, M.J. PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S: Common questions on tracking records and the flow diagram. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2022, 110, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.B.; Feitosa, A.O.; Lima, I.G.O.; Bispo, J.R.S.; Santos, A.C.M.; Moreira, M.S.A.; Câmara, P.E.A.S.; Rosa, L.H.; Oliveira, V.M.; Duarte, A.W.F.; et al. Antarctic organisms as a source of antimicrobial compounds: A patent review. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2022, 94 (Suppl. 1), e20210840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.E.; Min, S.K.; Hong, J.-M.; Kim, K.H.; Han, S.J.; Yim, J.H.; Park, H.; Kim, C. Anti-inflammatory effects of methanol extracts from the Antarctic lichen, Amandinea sp. in LPS-stimulated raw 264.7 macrophages and zebrafish. Fish Shellfish. Immunol. 2020, 107, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Liu, R.; Woo, S.; Kang, K.B.; Park, H.; Yu, Y.H.; Ha, H.H.; Oh, S.Y.; Yang, J.H.; Kim, H.; et al. Linking a gene cluster to atranorin, a major cortical substance of lichens, through genetic dereplication and heterologous expression. mBio 2021, 12, e0111121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Benítez, A.; Ortega-Valencia, J.E.; Sánchez, M.; Hillmann-Eggers, M.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P.; Vargas-Arana, G.; Simirgiotis, M.J. UHPLC-MS chemical fingerprinting and antioxidant, enzyme inhibition, anti-inflammatory in silico and cytoprotective activities of Cladonia chlorophaea and C. gracilis (Cladoniaceae) from Antarctica. Antioxidants 2022, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, C.; Cartagena, C.; Caballero, L.; Melo, F.; Areche, C.; Cornejo, A. The fumarprotocetraric acid inhibits Tau covalently, avoiding cytotoxicity of aggregates in cells. Molecules 2021, 26, 3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Areche, C.; Parra, J.R.; Sepulveda, B.; García-Beltrán, O.; Simirgiotis, M.J. UHPLC-MS metabolomic fingerprinting, antioxidant, and enzyme inhibition activities of Himantormia lugubris from Antarctica. Metabolites 2022, 12, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, M.H.; Shin, M.J.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, S.; Eun, J.; So, E.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Suh, S.-S.; Youn, U.J. Bioactive secondary metabolites isolated from the Antarctic lichen Himantormia lugubris. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202200374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Benítez, A.; Ortega-Valencia, J.E.; Sanchez, M.; Divakar, P.K.; Simirgiotis, M.J.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P. Metabolomic profiling, antioxidant and enzyme inhibition properties and molecular docking analysis of Antarctic lichens. Molecules 2022, 27, 8086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Benítez, A.; Ortega-Valencia, J.E.; Jara-Pinuer, N.; Sanchez, M.; Vargas-Arana, G.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P.; Simirgiotis, M.J. Antioxidant and antidiabetic activity and phytoconstituents of lichen extracts with temperate and polar distribution. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1251856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Lee, J.H.; Youn, U.J. Steroids from the Antarctic lichen Ramalina terebrata and their chemotaxonomical significance. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2023, 107, 104583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jeong, S.Y.; Nguyen, D.L.; So, J.E.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, J.H.; Han, S.J.; Suh, S.S.; Lee, J.H.; Youn, U.J. Stereocalpin B, a new cyclic depsipeptide from the Antarctic lichen Ramalina terebrata. Metabolites 2022, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.K.; Hong, J.M.; Kim, K.H.; Han, S.J.; Kim, I.C.; Oh, H.; Yim, J.H. Potential of ramalin and its derivatives for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules 2021, 26, 6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phi, K.H.; Shin, M.J.; Lee, S.; So, J.E.; Kim, J.H.; Suh, S.S.; Koo, M.H.; Shin, S.C.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Bioactive terphenyls isolated from the Antarctic lichen Stereocaulon alpinum. Molecules 2022, 27, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.H.; Youn, U.J.; Suh, S.S. The comprehensive roles of atranorin, a secondary metabolite from the Antarctic lichen Stereocaulon caespitosum, in HCC tumorigenesis. Molecules 2019, 24, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, F.; Caballero, J.; Vargas, R.; Cornejo, A.; Areche, C. Continental and Antarctic lichens: Isolation, identification and molecular modeling of the depside tenuiorin from the Antarctic lichen Umbilicaria Antarctica as Tau protein inhibitor. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yañez, O.; Osorio, M.I.; Osorio, E.; Tiznado, W.; Ruíz, L.; García, C.; Nagles, O.; Simirgiotis, M.J.; Castañeta, G.; Areche, C.; et al. Antioxidant activity and enzymatic of lichen substances: A study based on cyclic voltammetry and theoretical. Chem. Bio.l Interact 2023, 372, 110357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.M.; Kim, J.E.; Min, S.K.; Kim, K.H.; Han, S.J.; Yim, J.H.; Park, H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, I.C. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Antarctic lichen Umbilicaria Antarctica methanol extract in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophage cells and zebrafish model. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 8812090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Bello, M.J.; Moreno, M.L.; Estellés-Leal, R.; Hernández-Andreu, J.M.; Prieto-Ruiz, J.A. Usnea aurantiaco-atra (Jacq) Bory: Metabolites and biological activities. Molecules 2023, 28, 7317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phi, K.-H.; So, J.E.; Kim, J.H.; Koo, M.H.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, S.; Youn, U.J. Chemical constituents from the Antarctic lichen Usnea aurantiaco-atra and their chemotaxonomic significance. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2023, 106, 104581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Li, X.J.; Kim, D.C.; Kim, T.K.; Sohn, J.H.; Kwon, H.; Lee, D.; Kim, Y.C.; Yim, J.H.; Oh, H. PTP1B Inhibitory secondary metabolites from an Antarctic fungal strain Acremonium sp. SF-7394. Molecules 2021, 26, 5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, H.J.; Park, Y.; Hong, S.G.; Lee, Y.M. Diversity and physiological characteristics of Antarctic lichens-associated bacteria. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, N.; Han, S.R.; Kim, B.; Park, H.; Lee, J.H.; Oh, T.J. Comparative genomic study of polar lichen-associated Hymenobacter sp. PAMC 26554 and Hymenobacter sp. PAMC 26628 reveals the presence of polysaccharide-degrading ability based on habitat. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 2940–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Lee, C.W.; Bae, D.W.; Do, H.; Jeong, C.S.; Hwang, J.; Cha, S.S.; Lee, J.H. Structural basis of the cooperative activation of type II citrate synthase (HyCS) from Hymenobacter sp. PAMC 26554. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesiak, J.; Woltyńska, A.; Zdanowski, M.K.; Górniak, D.; Świątecki, A.; Olech, M.A.; Aleksandrzak-Piekarczyk, T. Metabolic fingerprinting of the Antarctic cyanolichen Leptogium puberulum-associated bacterial community (Western Shore of Admiralty Bay, King George Island, Maritime Antarctica). Microb. Ecol. 2021, 82, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.M.; Byeon, S.M.; Gwak, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Shin, D.H.; Park, H.Y. Novel, acidic, and cold-adapted glycoside hydrolase family 8 endo-β-1,4-glucanase from an Antarctic lichen-associated bacterium, Lichenicola cladoniae PAMC 26568. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 935497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, H.J.; Shin, S.C.; Park, Y.; Choi, A.; Baek, K.; Hong, S.G.; Cho, Y.J.; Lee, H.; Lee, Y.M. Lichenicola cladoniae gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the family Acetobacteraceae isolated from an Antarctic lichen. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 5918–5925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, H.J.; Baek, K.; Hwang, C.Y.; Shin, S.C.; Hong, S.G.; Lee, Y.M. Lichenihabitans psoromatis gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of a novel lineage (Lichenihabitantaceae fam. nov.) within the order of Rhizobiales isolated from Antarctic lichen. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 3837–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A.V.; de Oliveira, A.J.; Tanabe, I.S.B.; Silva, J.V.; da Silva Barros, T.W.; da Silva, M.K.; França, P.H.B.; Leite, J.; Putzke, J.; Montone, R.; et al. Antarctic lichens as a source of phosphate-solubilizing bacteria. Extremophiles 2021, 25, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, N.; Han, S.R.; Kim, B.; Jung, S.H.; Park, H.; Lee, J.H.; Oh, T.J. Complete genome sequencing and comparative CAZyme analysis of Rhodococcus sp. PAMC28705 and PAMC28707 provide insight into their biotechnological and phytopathogenic potential. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 1731–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A.V.; da Silva, M.K.; de Oliveira, A.J.; Silva, J.V.; Paulino, S.S.; de Queiroz, A.C.; Leite, J.; França, P.H.B.; Putzke, J.; Montone, R.; et al. Phosphate solubilization by Antarctic yeasts isolated from lichens. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, K.B.; Vítek, P.; Barták, M.A. A correlative approach, combining chlorophyll a fluorescence, reflectance, and Raman spectroscopy, for monitoring hydration induced changes in Antarctic lichen Dermatocarpon polyphyllizum. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 208, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vera, J.P.; Alawi, M.; Backhaus, T.; Baqué, M.; Billi, D.; Böttger, U.; Berger, T.; Bohmeier, M.; Cockell, C.; Demets, R.; et al. Limits of life and the habitability of Mars: The ESA space experiment BIOMEX on the ISS. Astrobiology 2019, 19, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.M.; Lee, H.; Hong, S.G.; Lee, J. Study of ecophysiological responses of the Antarctic fruticose lichen Cladonia borealis using the PAM fluorescence system under natural and laboratory conditions. Plants 2020, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barták, M.; Hájek, J.; Orekhova, A.; Villagra, J.; Marín, C.; Palfner, G.; Casanova-Katny, A. Inhibition of primary photosynthesis in desiccating Antarctic lichens differing in their photobionts, thallus morphology, and spectral properties. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Sanz, N.; Raggio, J.; Gonzalez, S.; Dal Grande, F.; Prost, S.; Green, A.; Pintado, A.; Sancho, L.G. Climate change leads to higher NPP at the end of the century in the Antarctic tundra: Response patterns through the lens of lichens. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 835, 155495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín, C.; Barták, M.; Palfner, G.; Vergara-Barros, P.; Fernandoy, F.; Hájek, J.; Casanova-Katny, A. Antarctic lichens under long-Term passive warming: Species-specific photochemical responses to desiccation and heat shock Treatments. Plants 2022, 11, 2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokhorst, S.; Convey, P.; Aerts, R. Nitrogen inputs by marine vertebrates drive abundance and richness in Antarctic terrestrial ecosystems. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 1721–1727.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, D.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R.; Putzke, J.; Francelino, M.R.; Ferrari, F.R.; Corrêa, G.R.; Villa, P.M. How does the pedoenvironmental gradient shape non-vascular species assemblages and community structures in Maritime Antarctica? Ecol. Indic. 2020, 108, 105726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, D.; Villa, P.M.; Michel, R.F.M.; Putzke, J.; Pereira, A.B.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R. Species composition, diversity and coverage pattern of associated communities of mosses-lichens along a pedoenvironmental gradient in Maritime Antarctica. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2021, 94 (Suppl. 1), e20200094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, L.M.; Leihy, R.I.; Chown, S.L. Improving species-based area protection in Antarctica. Conserv. Biol. 2022, 36, e13885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotille, M.E.; Bremer, U.F.; Vieira, G.; Velho, L.F.; Petsch, C.; Simões, J.C. Evaluation of UAV and satellite-derived NDVI to map Maritime Antarctic vegetation. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 125, 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotille, M.E.; Bremer, U.F.; Vieira, G.; Velho, L.F.; Petsch, C.; Auger, J.D.; Simões, J.C. UAV-based classification of Maritime Antarctic vegetation types using GEOBIA and random forest. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 71, 101768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, L.G.; Aramburu, A.; Etayo, J.; Beltrán-Sanz, N. Floristic Similarities between the lichen flora of both sides of the Drake passage: A biogeographical approach. J. Fungi. 2023, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.H.; Wasley, J.; Ashcroft, M.B.; Ryan-Colton, E.; Lucieer, A.; Chisholm, L.A.; Robinson, S.A. Semi-automated analysis of digital photographs for monitoring East Antarctic vegetation. Front. Plant. Sci. 2020, 11, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, E.L.; Santos, E.C.D.; Figueiredo, A.R.; Simões, J.C. Antarctic biological soil crusts surface reflectance patterns from landsat and sentinel-2 images. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2022, 94 (Suppl. 1), e20210596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, E.L.D.; Santos, E.C.D.; Figueiredo, A.R.; Simões, J.C. The use of sentinel-2 imagery to generate vegetations maps for the Northern Antarctic peninsula and offshore islands. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2023, 95 (Suppl. 3), e20230710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, V.; Pina, P.; Heleno, S.; Vieira, G.; Mora, C.G.R.; Schaefer, C. Monitoring recent changes of vegetation in Fildes Peninsula (King George Island, Antarctica) through satellite imagery guided by UAV surveys. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putzke, J.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R.; Villa, P.M.; Pereira, A.B.; Schunemann, A.L.; Putzke, M.T.L. The diversity and structure of plant communities in the Maritime Antarctic is shaped by southern giant petrel’s (Macronectes giganteus) breeding activities. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2022, 94 (Suppl. 1), e20210597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, A.; Tovar-Sánchez, A.; Fernandez-Marín, B.; Navarro, G.; Barbero, L. Characterization of an Antarctic penguin colony ecosystem using high-resolution UAV hyperspectral imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 125, 103565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.P.; Joshi, H.; Kakadiya, D.; Bhatt, M.S.; Bajpai, R.; Paul, R.R.; Upreti, D.K.; Saini, S.; Beg, M.J.; Pande, A.; et al. Mapping lichen abundance in ice-free areas of Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica using remote sensing and lichen spectra. Polar Sci. 2023, 38, 100976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Marín, B.; López-Pozo, M.; Perera-Castro, A.V.; Arzac, M.I.; Sáenz-Ceniceros, A.; Colesie, C.; De Los Ríos, A.; Sancho, L.G.; Pintado, A.; Laza, J.M.; et al. Symbiosis at its limits: Ecophysiological consequences of lichenization in the genus Prasiola in Antarctica. Ann. Bot. 2020, 124, 1211–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, H.J.; Park, Y.; Yang, J.; Jang, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, Y.M. Polymorphobacter megasporae sp. nov., isolated from an Antarctic lichen. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggia, L.; Coleine, C.; De Carolis, R.; Cometto, A.; Selbmann, L. Antarctolichenia onofrii gen. nov. sp. nov. from Antarctic endolithic communities untangles the evolution of rock-inhabiting and lichenized fungi in Arthoniomycetes. J. Fungi. 2021, 7, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Noh, H.J.; Hwang, C.Y.; Shin, S.C.; Hong, S.G.; Jin, Y.K.; Lee, H.; Lee, Y.M. Hymenobacter siberiensis sp. nov., isolated from a marine sediment of the East Siberian Sea and Hymenobacter psoromatis sp. nov., isolated from an Antarctic lichen. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleine, C.; Biagioli, F.; de Vera, J.P.; Onofri, S.; Selbmann, L. Endolithic microbial composition in Helliwell Hills, a newly investigated Mars-like area in Antarctica. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 4002–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woltyńska, A.; Gawor, J.; Olech, M.A.; Górniak, D.; Grzesiak, J. Bacterial communities of Antarctic lichens explored by gDNA and cDNA 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2023, 99, fiad015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Naganuma, T.; Nakai, R.; Imura, S.; Tsujimoto, M.; Convey, P. Microbiomic analysis of bacteria associated with rock tripe lichens in Continental and Maritime Antarctic regions. J. Fungi. 2022, 8, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faluaburu, M.S.; Nakai, R.; Imura, S.; Naganuma, T. Phylotypic characterization of mycobionts and photobionts of rock tripe lichen in East Antarctica. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezzasoma, A.; Coleine, C.; Sannino, C.; Selbmann, L. Endolithic bacterial diversity in lichen-dominated communities is shaped by sun exposure in McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 83, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagioli, F.; Coleine, C.; Buzzini, P.; Turchetti, B.; Sannino, C.; Selbmann, L. Positive fungal interactions are key drivers in Antarctic endolithic microcosms at the boundaries for life sustainability. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2023, 9, fiad045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragazza, L.; Robroek, B.J.M.; Jassey, V.E.J.; Arif, M.S.; Marchesini, R.; Guglielmin, M.; Cannone, N. Soil microbial community structure and enzymatic activity along a plant cover gradient in Victoria Land (Continental Antarctica). Geoderma 2019, 353, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Hao, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Pei, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, G. Accumulation and influencing factors of novel brominated flame retardants in soil and vegetation from Fildes Peninsula, Antarctica. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 756, 144088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szufa, K.M.; Mietelski, J.W.; Olech, M.A.; Kowalska, A.; Brudecki, K. Anthropogenic radionuclides in Antarctic biota—Dosimetrical considerations. J. Environ. Radioact. 2020, 213, 106140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szufa, K.M.; Mietelski, J.W.; Olech, M.A. Assessment of internal radiation exposure to Antarctic biota due to selected natural radionuclides in terrestrial and marine environments. J. Environ. Radioact. 2021, 237, 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catán, S.P.; Bubach, D.; Arribere, M.; Ansaldo, M.; Kitaura, M.J.; Scur, M.C.; Lirio, J.M. Trace elements baseline levels in Usnea Antarctica from Clearwater Mesa, James Ross Island, Antarctica. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saniewski, M.; Wietrzyk-Pełka, P.; Węgrzyn, M.H.; Saniewska, D.; Bałazy, P.; Zalewska, T. Distribution of 90Sr and 137Cs in biotic and abiotic elements of the coastal zone of the King George Island (South Shetland Archipelago, Antarctic Peninsula). Chemosphere 2023, 322, 138218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coufalík, P.; Uher, A.; Zvěřina, O.; Komárek, J. Determination of cadmium in lichens by solid sampling graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (SS-GF-AAS). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhakta, S.; Rout, T.K.; Karmakar, D.; Pawar, C.; Padhy, P.K. Trace elements and their potential risk assessment on polar ecosystem of Larsemann Hills, East Antarctica. Polar Sci. 2022, 31, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.C.; de Abreu-Mota, M.A.; do Nascimento, M.G.; Dauner, A.L.L.; Lourenço, R.A.; Bícego, M.C.; Montone, R.C. Sources and depositional changes of aliphatic hydrocarbons recorded in sedimentary cores from Admiralty Bay, South Shetland Archipelago, Antarctica during last decades. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 795, 148881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, F.R.; Thomazini, A.; Pereira, A.B.; Spokas, K.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R. Potential greenhouse gases emissions by different plant communities in Maritime Antarctica. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2022, 94 (Suppl. 1), e20210602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-García, S.; Sánchez-García, L.; Prieto-Ballesteros, O.; Carrizo, D. Molecular and isotopic biogeochemistry on recently-formed soils on King George Island (Maritime Antarctica) after glacier retreat upon warming climate. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Benavent, I.; Pérez-Ortega, S.; de Los Ríos, A.; Mayrhofer, H.; Fernández-Mendoza, F. Neogene speciation and Pleistocene expansion of the genus Pseudephebe (Parmeliaceae, lichenized fungi) involving multiple colonizations of Antarctica. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2021, 155, 107020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andeev, M. Lichens of Larsemann Hills and adjacent oases in the area of Prydz Bay (Princess Elizabeth Land and MacRobertson Land, Antarctica). Polar Sci. 2023, 38, 101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauchope, H.S.; Shaw, J.D.; Terauds, A. A snapshot of biodiversity protection in Antarctica. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüner, N.P.A.; Smith, D.R.; Cvetkovska, M.; Zhang, X.; Ivanov, A.G.; Szyszka-Mroz, B.; Kalra, I.; Morgan-Kiss, R. Photosynthetic adaptation to polar life: Energy balance, photoprotection and genetic redundancy. J. Plant. Physiol. 2022, 268, 153557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zastrow, M. South Korea. Nature 2016, 536, S22–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, B. A comprehensive review on secondary metabolites and health-promoting effects of edible lichen. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 1, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solárová, Z.; Liskova, A.; Samec, M.; Kubatka, P.; Büsselberg, D.; Solár, P. Anticancer potential of lichens’ secondary metabolites. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulsen-Silva, E.; Gordillo-Fuenzalida, F.; Atala, C.; Moreno, A.A.; Otero, M.C. Bioactive lichen secondary metabolites and their presence in species from Chile. Metabolites 2023, 13, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, M.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Pan, X.; Pan, F.; Wei, X. Discovery and excavation of lichen bioactive natural products. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1177123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Londone-Bailon, P.; Sánchez-Robinet, C.; Alvarez-Guzman, C. In vitro antibacterial, antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of methanol-acetone extracts from Antarctic lichens (Usnea Antarctica and Usnea aurantiaco-atra). Polar Biol. 2019, 22, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, S.B.; Dos Santos, B.C.; Kreusch, M.G.; da Silva, A.F.; Duarte, R.T.D.; Robl, D. The hidden rainbow: The extensive biotechnological potential of Antarctic fungi pigments. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 1675–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harańczyk, H.; Strzałka, K.; Kubat, K.; Andrzejowska, A.; Olech, M.; Jakubiec, D.; Kijak, P.; Palfner, G.; Casanova-Katny, A. A comparative analysis of gaseous phase hydration properties of two lichenized fungi: Niebla tigrina (Follman) Rundel & Bowler from Atacama Desert and Umbilicaria Antarctica Frey & I. M. Lamb from Robert Island, Southern Shetlands Archipelago, Maritime Antarctica. Extremophiles 2021, 25, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacior, M.; Harańczyk, H.; Nowak, P.; Kijak, P.; Marzec, M.; Fitas, J.; Olech, M.A. Low-temperature immobilization of water in Antarctic Turgidosculum complicatulum and in Prasiola crispa. Part I. Turgidosculum complicatulum. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 173, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, T.; MeeBen, J.; Demets, R.; de Vera, J.-P.P.; Ott, S. DNA damage of the lichen Buellia frigida after 1.5 years in space using Randomly Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD). Planet. Space Sci. 2019, 177, 104687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnelli, A.; Corti, G.; Massaccesi, L.; Ventura, S.; D’Acqui, L.P. Impact of biological crusts on soil formation in polar ecosystems. Geoderma 2021, 401, 115340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipro, C.V.Z.; Bustamante, P.; Montone, R.C.; Oliveira, L.C.; Petry, M.V. Do population parameters influence the role of seabird colonies as secondary pollutants source? A case study for Antarctic ecosystems. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 149, 110534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipro, C.V.Z.; Bustamante, P.; Taniguchi, S.; Silva, J.; Petry, M.V.; Montone, R.C. Seabird colonies as relevant sources of pollutants in Antarctic ecosystems: Part 2—Persistent Organic Pollutants. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 866–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, B.A.; Convey, P.; Feeser, K.L.; Nielsen, U.N.; Van Horn, D.J. Environmental harshness mediates the relationship between aboveground and belowground communities in Antarctica. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 164, 108493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleine, C.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Albanese, D.; Singh, B.K.; Stajich, J.E.; Selbmann, L.; Egidi, E. Rocks support a distinctive and consistent mycobiome across contrasting dry regions of Earth. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2022, 98, fiac030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, H.J.; Lee, Y.M.; Park, C.H.; Lee, H.K.; Cho, J.C.; Hong, S.G. Microbiome in Cladonia squamosa is vertically stratified according to microclimatic conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Convey, P.; Peck, L.S. Antarctic environmental change and biological responses. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaz0888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, R.; Conlan, X.A.; Goel, M. Recent advances in research for potential utilization of unexplored lichen metabolites. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 62, 108072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Dal Grande, F.; Schmitt, I. Genome mining as a biotechnological tool for the discovery of novel biosynthetic genes in lichens. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 993171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).