Culture-Based Wastewater Surveillance for the Detection and Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcal Species

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Collection

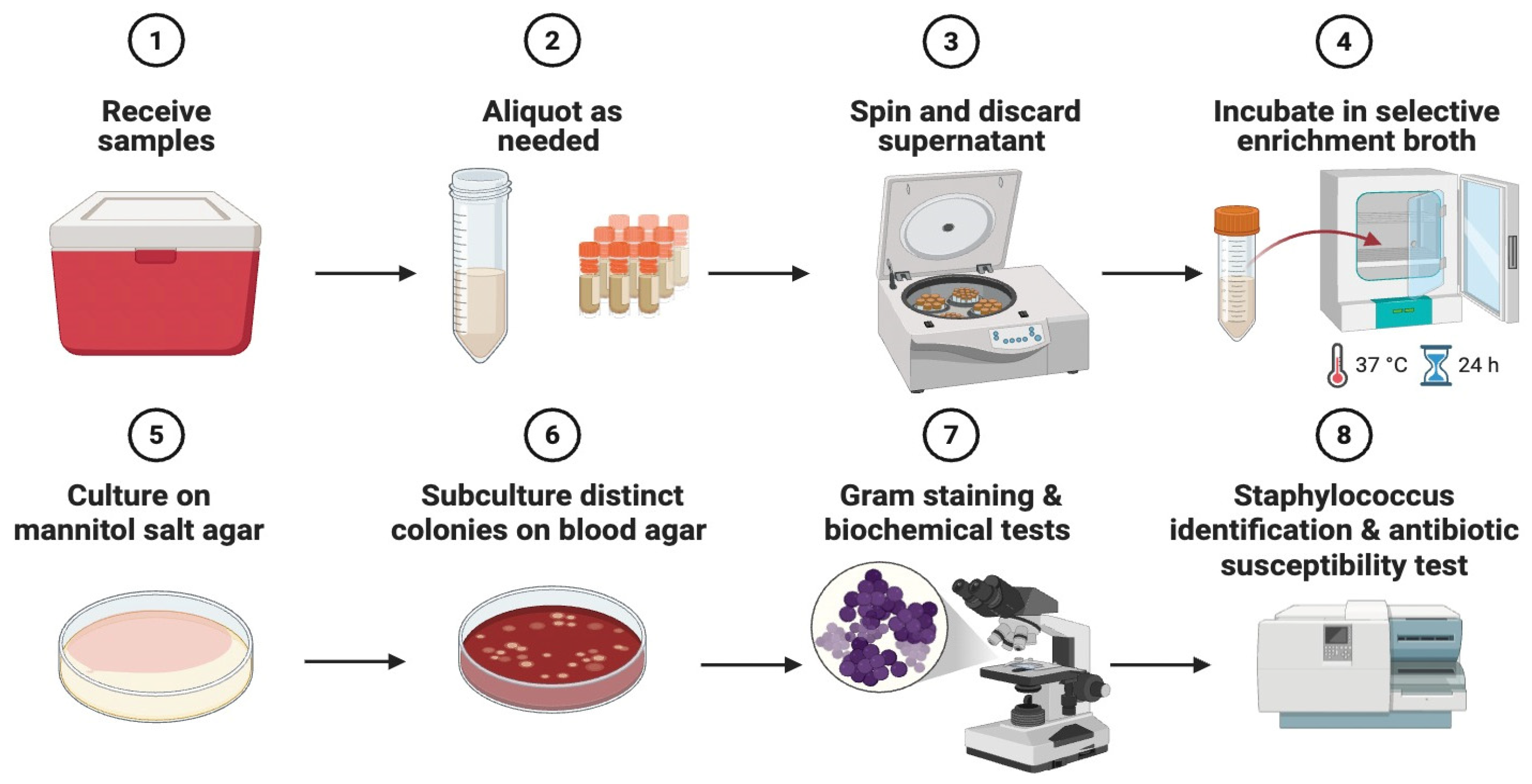

2.2. Sample Processing and Primary Isolation

2.3. Species-Level Identification

2.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

2.5. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

2.6. Bioinformatics and Genomic Analyses

3. Results

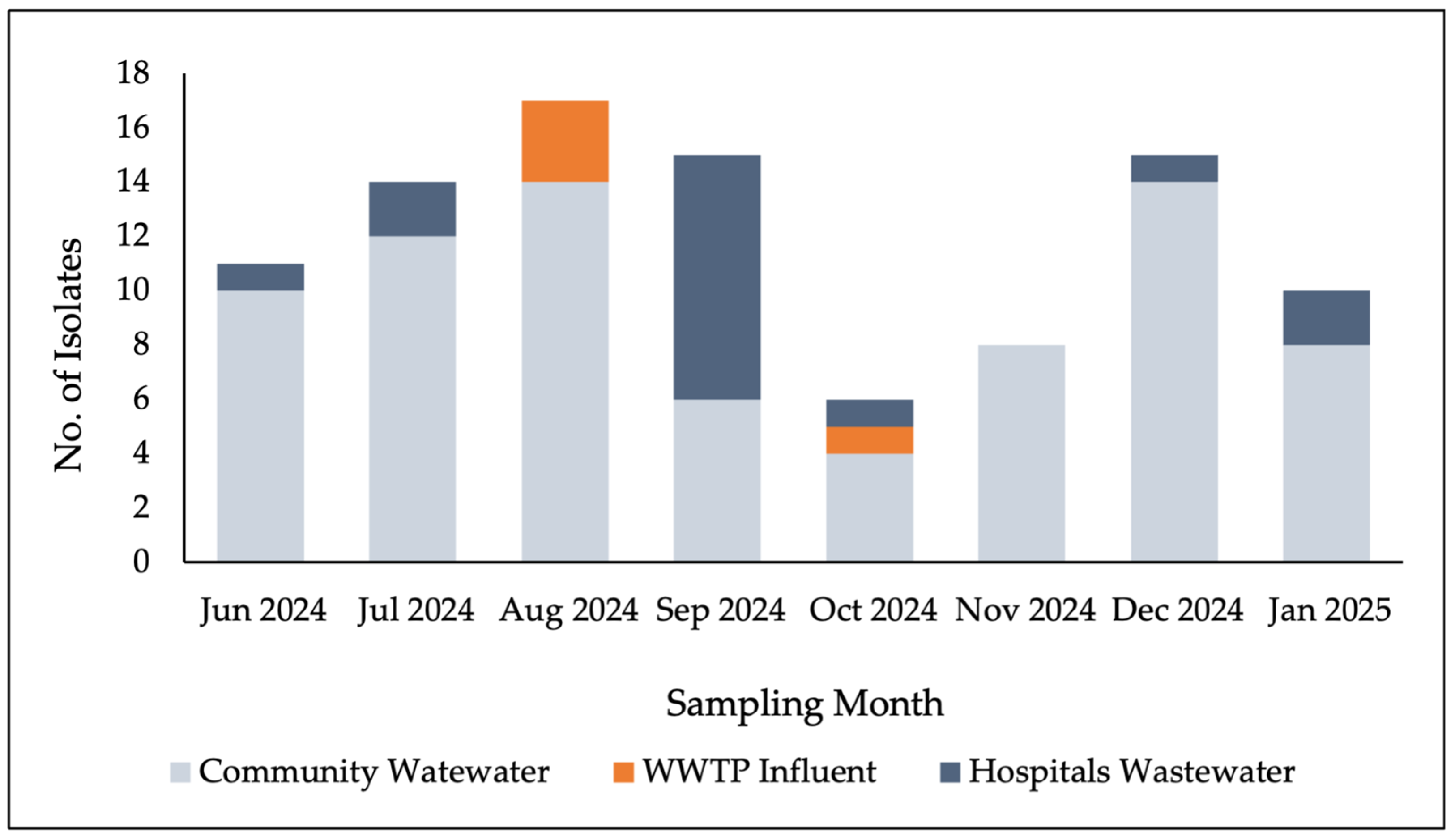

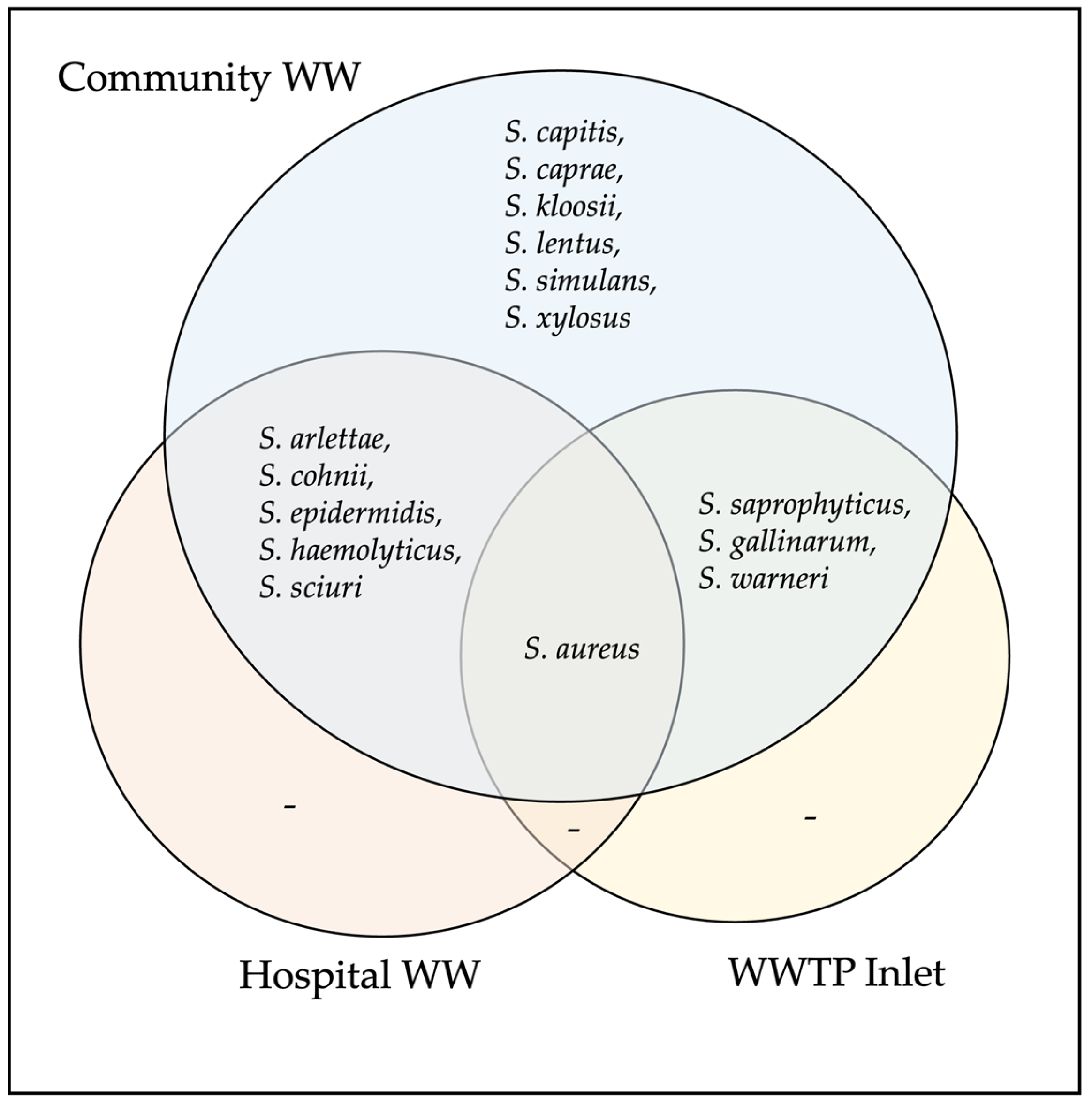

3.1. Detection of Staphylococcal Species

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

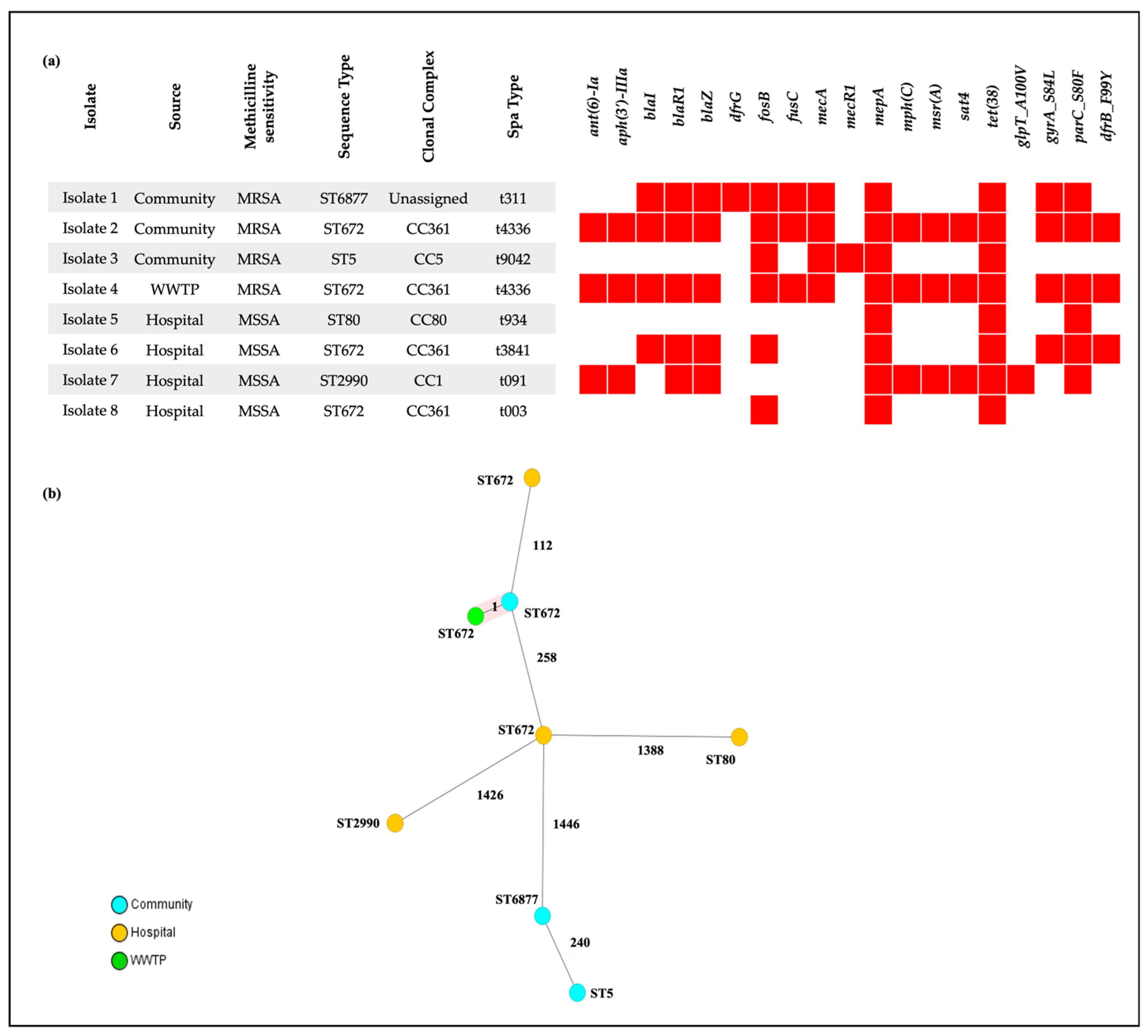

3.3. Whole-Genome Sequencing of S. aureus Isolates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Anti-microbial Resistance |

| AST | Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| cgMLST | Core genome multilocus sequence typing |

| CoNS | Coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| CoNs | Coagulase-positive staphylococci |

| CoPS | Coagulase-positive staphylococci |

| HGT | Horizontal Gene Transfer |

| ID-GP | Identification—Gram-Positive |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MICs | Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations |

| MR-CoNS | Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| MSSA | Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus |

| TSB | Tryptic Soy Broth |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

| WBS | Wastewater-Based Surveillance |

| WGS | Whole Genome Sequencing |

| WWTP | Wastewater Treatment Plant |

References

- Mariani, F.; Galvan, E.M. Staphylococcus aureus in Polymicrobial Skinand Soft Tissue Infections: Impact of Inter-Species Interactionsin Disease Outcome. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, N.; Di Carlo, P.; Andriolo, M.; Mazzola, G.; Diprima, E.; Rea, T.; Anastasia, A.; Fasciana, T.M.A.; Pipito, L.; Capra, G.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus and Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci from Bloodstream Infections: Frequency of Occurrence and Antimicrobial Resistance, 2018–2021. Life 2023, 13, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albavera-Gutierrez, R.R.; Espinosa-Ramos, M.A.; Rebolledo-Bello, E.; Paredes-Herrera, F.J.; Carballo-Lucero, D.; Valencia-Ledezma, O.E.; Castro-Fuentes, C.A. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus Infections in the Implantation of Orthopedic Devices in a Third-Level Hospital: An Observational Cohort Study. Pathogens 2024, 13, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Santana, G. Staphylococcus aureus: Dynamics of pathogenicity and antimicrobial-resistance in hospital and community environments—Comprehensive overview. Res. Microbiol. 2025, 176, 104267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesoji, T.O.; Somda, N.S.; Tetteh-Quarcoo, P.; Shittu, A.O.; Donkor, E.S. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibniz Institute DSMZ. List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). Genus Staphylococcus. Available online: https://lpsn.dsmz.de/search?word=staphylococcus (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Wildsmith, C.; Barratt, S.; Kerridge, F.; Thomas, J.; Negus, D. Genomic and phenotypic characterization of staphylococci isolated from the skin of non-human primates. Microbiology 2025, 171, 001546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argemi, X.; Hansmann, Y.; Prola, K.; Prevost, G. Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Pathogenomics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touaitia, R.; Mairi, A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Basher, N.S.; Idres, T.; Touati, A. Staphylococcus aureus: A Review of the Pathogenesis and Virulence Mechanisms. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.T.; Andam, C.P. Extensive Horizontal Gene Transfer within and between Species of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus. Genome Biol. Evol. 2021, 13, evab206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Martin, M.; Corbera, J.A.; Suarez-Bonnet, A.; Tejedor-Junco, M.T. Virulence factors in coagulase-positive staphylococci of veterinary interest other than Staphylococcus aureus. Vet. Q. 2020, 40, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monistero, V.; Graber, H.U.; Pollera, C.; Cremonesi, P.; Castiglioni, B.; Bottini, E.; Ceballos-Marquez, A.; Lasso-Rojas, L.; Kroemker, V.; Wente, N.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Bovine Mastitis in Eight Countries: Genotypes, Detection of Genes Encoding Different Toxins and Other Virulence Genes. Toxins 2018, 10, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westgate, S.J.; Percival, S.L.; Knottenbelt, D.C.; Clegg, P.D.; Cochrane, C.A. Microbiology of equine wounds and evidence of bacterial biofilms. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 150, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, V.; Canica, M.; Manageiro, V.; Verbisck, N.; Tejedor-Junco, M.T.; Gonzalez-Martin, M.; Corbera, J.A.; Poeta, P.; Igrejas, G. Staphylococcus aureus and Methicillin-Resistant Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci in Nostrils and Buccal Mucosa of Healthy Camels Used for Recreational Purposes. Animals 2022, 12, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, M.A.; Ullah, H.; Tabassum, S.; Fatima, B.; Woodley, T.A.; Ramadan, H.; Jackson, C.R. Staphylococci in poultry intestines: A comparison between farmed and household chickens. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 4549–4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, W.T.; Jun, J.W.; Giri, S.S.; Yun, S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, S.W.; Han, S.J.; Kwon, J.; Park, S.C. Staphylococcus xylosus Infection in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) As a Primary Pathogenic Cause of Eye Protrusion and Mortality. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbovska, V.; Sedlacek, I.; Zeman, M.; Svec, P.; Kovarovic, V.; Sedo, O.; Laichmanova, M.; Doskar, J.; Pantucek, R. Characterization of Staphylococcus intermedius Group Isolates Associated with Animals from Antarctica and Emended Description of Staphylococcus delphini. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, P.; Lozano, C.; Benito, D.; Estepa, V.; Tenorio, C.; Zarazaga, M.; Torres, C. Characterization of staphylococci in urban wastewater treatment plants in Spain, with detection of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 212, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladipo, A.O.; Oladipo, O.G.; Bezuidenhout, C.C. Detection of mecA positive staphylococcal species in a wastewater treatment plant in South Africa. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 117165–117178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, M.; Alexa, M.; Mabandza, D.B.; Dulaurent, S.; Huynh, B.T.; Gaschet, M.; Opatowski, L.; Breurec, S.; Ploy, M.C.; Dagot, C. Wastewater-based AMR surveillance associated with tourism on a Caribbean island (Guadeloupe). J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 43, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Meza, M.E.; Galarde-Lopez, M.; Cornejo-Juarez, P.; Carrillo-Quiroz, B.A.; Velazquez-Acosta, C.; Bobadilla-Del-Valle, M.; Ponce-de-Leon, A.; Alpuche-Aranda, C.M. Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus sp. and Enterococcus sp. in Municipal and Hospital Wastewater: A Longitudinal Study. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.K.; Barker, L.; Budgell, E.P.; Vihta, K.D.; Sims, N.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Harriss, E.; Crook, D.W.; Read, D.S.; Walker, A.S.; et al. Systematic review of wastewater surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in human populations. Environ. Int. 2022, 162, 107171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philo, S.E.; De Leon, K.B.; Noble, R.T.; Zhou, N.A.; Alghafri, R.; Bar-Or, I.; Darling, A.; D’Souza, N.; Hachimi, O.; Kaya, D.; et al. Wastewater surveillance for bacterial targets: Current challenges and future goals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0142823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albastaki, A.; Naji, M.; Lootah, R.; Almeheiri, R.; Almulla, H.; Almarri, I.; Alreyami, A.; Aden, A.; Alghafri, R. First confirmed detection of SARS-COV-2 in untreated municipal and aircraft wastewater in Dubai, UAE: The use of wastewater based epidemiology as an early warning tool to monitor the prevalence of COVID-19. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 760, 143350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.M.; Gundogdu, A.; Stratton, H.M.; Katouli, M. Antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospital wastewaters and sewage treatment plants with special reference to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 114, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinski, W.; Korzeniewska, E.; Harnisz, M.; Hubeny, J.; Buta, M.; Rolbiecki, D. The prevalence of drug-resistant and virulent Staphylococcus spp. in a municipal wastewater treatment plant and their spread in the environment. Environ. Int. 2020, 143, 105914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, S.; Mitra, S.; Mondal, A.H.; Kumari, H.; Mukhopadhyay, K. Prevalence and molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant coagulase negative staphylococci from urban wastewater in Delhi-NCR, India. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endalamaw, K.; Tadesse, S.; Asmare, Z.; Kebede, D.; Erkihun, M.; Abera, B. Antimicrobial resistance profile of bacteria from hospital wastewater at two specialized hospitals in Bahir Dar city, Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbait, G.D.; Daou, M.; Abuoudah, M.; Elmekawy, A.; Hasan, S.W.; Everett, D.B.; Alsafar, H.; Henschel, A.; Yousef, A.F. Comparison of qPCR and metagenomic sequencing methods for quantifying antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johar, A.A.; Salih, M.A.; Abdelrahman, H.A.; Al Mana, H.; Hadi, H.A.; Eltai, N.O. Wastewater-based epidemiology for tracking bacterial diversity and antibiotic resistance in COVID-19 isolation hospitals in Qatar. J. Hosp. Infect. 2023, 141, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadi, V.S.; Daou, M.; Zayed, N.; AlJabri, M.; Alsheraifi, H.H.; Aldhaheri, S.S.; Abuoudah, M.; Alhammadi, M.; Aldhuhoori, M.; Lopes, A.; et al. Long-term study on wastewater SARS-CoV-2 surveillance across United Arab Emirates. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 887, 163785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, I.R.D.; de Lima, L.F.; de Souza, M.B.; da Silva, I.N.M.; de Sousa, A.R.V.; Bailao, A.M.; Amaral, C.L.D.; Bailao, E. First record of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolated from the Meia Ponte River and effluent in Brazil: An analysis of 1198 isolates. N. Microbes N. Infect. 2025, 66, 101603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolefas, E.; Leung, T.; Okshevsky, M.; McKay, G.; Hignett, E.; Hamel, J.; Aguirre, G.; Blenner-Hassett, O.; Boyle, B.; Levesque, R.C.; et al. Culture-Dependent Bioprospecting of Bacterial Isolates From the Canadian High Arctic Displaying Antibacterial Activity. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. In CLSI Supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talbot, B.M.; Jacko, N.F.; Petit, R.A.; Pegues, D.A.; Shumaker, M.J.; Read, T.D.; David, M.Z. Unsuspected Clonal Spread of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Causing Bloodstream Infections in Hospitalized Adults Detected Using Whole Genome Sequencing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 2104–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.N.M.; Alberto-Lei, F.; Santos, F.F.; Balera, M.F.C.; Kurihara, M.N.; Cunha, C.C.; Seriacopi, L.S.; Durigon, T.S.; Reis, F.B.; Eisen, A.K.A.; et al. Comparative genomic analysis of resistance and virulence genes in Staphylococcus epidermidis and their impact on clinical outcome of musculoskeletal infections. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltwisy, H.O.; Twisy, H.O.; Hafez, M.H.; Sayed, I.M.; El-Mokhtar, M.A. Clinical Infections, Antibiotic Resistance, and Pathogenesis of Staphylococcus haemolyticus. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Mkrtchyan, H.V.; Cutler, R.R. Antibiotic resistance and mecA characterization of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from three hotels in London, UK. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, L.M.; Hayes, A.; Snape, J.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Gaze, W.H.; Murray, A.K. Co-selection for antibiotic resistance by environmental contaminants. npj Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uluseker, C.; Kaster, K.M.; Thorsen, K.; Basiry, D.; Shobana, S.; Jain, M.; Kumar, G.; Kommedal, R.; Pala-Ozkok, I. A Review on Occurrence and Spread of Antibiotic Resistance in Wastewaters and in Wastewater Treatment Plants: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 717809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalaifah, H.; Rahman, M.H.; Al-Surrayai, T.; Al-Dhumair, A.; Al-Hasan, M. A One-Health Perspective of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR): Human, Animals and Environmental Health. Life 2025, 15, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, M.C.; Maugeri, A.; Favara, G.; La Mastra, C.; Lio, R.M.S.; Barchitta, M.; Agodi, A. The Impact of Wastewater on Antimicrobial Resistance: A Scoping Review of Transmission Pathways and Contributing Factors. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egyir, B.; Dsani, E.; Owusu-Nyantakyi, C.; Amuasi, G.R.; Owusu, F.A.; Allegye-Cudjoe, E.; Addo, K.K. Antimicrobial resistance and genomic analysis of staphylococci isolated from livestock and farm attendants in Northern Ghana. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akya, A.; Lorestani, R.C.; Zhaleh, H.; Zargaran, F.N.; Ghadiri, K.; Rostamian, M. Effect of Vigna radiata, Tamarix ramosissima and Carthamus lanatus extracts on Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica: An in vitro study. Chin. Herb. Med. 2020, 12, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akya, A.; Chegenelorestani, R.; Shahvaisi-Zadeh, J.; Bozorgomid, A. Antimicrobial Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Hospital Wastewater in Kermanshah, Iran. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucherabine, S.; Nassar, R.; Mohamed, L.; Habous, M.; Nabi, A.; Husain, R.A.; Alfaresi, M.; Oommen, S.; Khansaheb, H.H.; Al Sharhan, M.; et al. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: The Shifting Landscape in the United Arab Emirates. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, J.; Abdulrazzaq, N.M.; Consortium, U.A.S.; Menezes, G.A.; Moubareck, C.A.; Everett, D.B.; Senok, A. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the United Arab Emirates: A 12-year retrospective analysis of evolving trends. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1244351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, I.; Ghazawi, A.; Mohamed, M.I.; Lakshmi, G.B.; Nassar, R.; Monecke, S.; Ehricht, R.; Moradigaravand, D.; Everett, D.; Goering, R.; et al. Exploring human-to-food contamination potential: Genome-based analysis of diversity, toxin repertoire, and antimicrobial resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in United Arab Emirates retail meat. One Health 2025, 21, 101216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, G.W.; Monecke, S.; Pearson, J.C.; Tan, H.L.; Chew, Y.K.; Wilson, L.; Ehricht, R.; O’Brien, F.G.; Christiansen, K.J. Evolution and diversity of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a geographical region. BMC Microbiol. 2011, 11, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, M.Z.; Daum, R.S. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 616–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkuraythi, D.M.; Alkhulaifi, M.M.; Binjomah, A.Z.; Alarwi, M.; Aldakhil, H.M.; Mujallad, M.I.; Alharbi, S.A.; Alshomrani, M.; Alshahrani, S.M.; Gojobori, T.; et al. Clonal Flux and Spread of Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Meat and Its Genetic Relatedness to Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Patients in Saudi Arabia. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkhoo, E.; Udo, E.E.; Boswihi, S.S.; Monecke, S.; Mueller, E.; Ehricht, R. The Dissemination and Molecular Characterization of Clonal Complex 361 (CC361) Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Kuwait Hospitals. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 658772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneeb, K.H.; Sudha, S.; Sivaraman, G.K.; Ojha, R.; Mendem, S.K.; Murugesan, D.; Raisen, C.L.; Shome, B.; Holmes, M. Whole-genome sequence analysis of Staphylococcus aureus from retail fish acknowledged the incidence of highly virulent ST672-MRSA-IVa/t1309, an emerging Indian clone, in Assam, India. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2022, 14, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Wen, X.; Zhang, B.; Yang, Y. Diversity and assembly patterns of activated sludge microbial communities: A review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W.; Han, X.; Sangeetha, T.; Yao, H. Causality and correlation analysis for deciphering the microbial interactions in activated sludge. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 870766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidhu, C.; Vikram, S.; Pinnaka, A.K. Unraveling the Microbial Interactions and Metabolic Potentials in Pre- and Post-treated Sludge from a Wastewater Treatment Plant Using Metagenomic Studies. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Nine Community Wastewater (Pumping Stations) | Two Hospital Wastewater (Pre-Sewer Junction) | Two Wastewater Treatment Plants (Influent & Effluent) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling Method | Grab | Grab | 24-h Composite |

| No. of Samples | 72 | 16 | 32 |

| Total No. of Samples | 120 wastewater samples | ||

| Staphylococcus Species | S. arlettae | S. aureus | S. capitis | S. caprae | S. cohnii | S. epidermidis | S. gallinarum | S. haemolyticus | S. kloosii | S. lentus | S. saprophyticus | S. sciuri | S. simulans | S. warneri | S. xylosus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of isolates detected | 6 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 13 | 1 | 3 | 9 |

| No. of multidrug-resistant * isolates | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| No. of methicillin-resistant isolates | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| No. of penicillin-resistant isolates | 6 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shouqair, D.; Alghafri, R.; Naji, M.; Albastaki, A.; Nassar, R.; Mohamed, L.; Aloba, B.; Awad, B.S.; Al Dhaheri, F.; Everett, D.; et al. Culture-Based Wastewater Surveillance for the Detection and Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcal Species. Vet. Sci. 2026, 13, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010014

Shouqair D, Alghafri R, Naji M, Albastaki A, Nassar R, Mohamed L, Aloba B, Awad BS, Al Dhaheri F, Everett D, et al. Culture-Based Wastewater Surveillance for the Detection and Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcal Species. Veterinary Sciences. 2026; 13(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleShouqair, Douha, Rashed Alghafri, Mohammed Naji, Abdulla Albastaki, Rania Nassar, Lobna Mohamed, Bisola Aloba, Bayan S. Awad, Fatima Al Dhaheri, Dean Everett, and et al. 2026. "Culture-Based Wastewater Surveillance for the Detection and Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcal Species" Veterinary Sciences 13, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010014

APA StyleShouqair, D., Alghafri, R., Naji, M., Albastaki, A., Nassar, R., Mohamed, L., Aloba, B., Awad, B. S., Al Dhaheri, F., Everett, D., Habib, I., Almashadani, M., Shibl, A. A., Rodríguez, J., Moradigaravand, D., Monecke, S., Ehricht, R., Khan, M., Goering, R., & Senok, A. (2026). Culture-Based Wastewater Surveillance for the Detection and Monitoring of Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcal Species. Veterinary Sciences, 13(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci13010014