Abstract

Virtualisation has received widespread adoption and deployment across a wide range of enterprises and industries throughout the years. Network Function Virtualisation (NFV) is a technical concept that presents a method for dynamically delivering virtualised network functions as virtualised or software components. Virtualised Network Function (VNF) has distinct advantages, but it also faces serious security challenges. Cyberattacks such as Denial of Service (DoS), malware/rootkit injection, port scanning, and so on can target VNF appliances just like any other network infrastructure. To create exceptional training exercises for machine or deep learning (ML/DL) models to combat cyberattacks in VNF, a suitable dataset (VNFCYBERDATA) exhibiting an actual reflection, or one that is reasonably close to an actual reflection, of the problem that the ML/DL model could address is required. This article describes a real VNF dataset that contains over seven million data points and twenty-five cyberattacks generated from five VNF appliances. To facilitate a realistic examination of VNF traffic, the dataset includes both benign and malicious traffic.

Dataset License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.

1. Introduction

The emergence of virtualised network functions (VNFs) has given the computing world agility, flexibility, cost effectiveness, resource optimisation, and scalability in offering network functions or services on demand by allowing VNF appliances to run on commodity hardware, decoupling them from dedicated, proprietary hardware. VNF appliances can provide tasks such as routing, firewalling, intrusion detection, and load balancing; therefore, there is a significant need to protect these functions because the bulk of VNF appliances are deployed at the network’s edge, where malevolent individuals can easily target them [1,2,3,4,5]. Current research on combating attacks using Machine or Deep learning (ML/DL) models is frequently based on well-known datasets, many of which are based on capturing network traffic patterns during an attack and a non-attack scenario. Several existing datasets, such as the BETH [6], ISOT CID [7], CIC-IDS2017 [8], CSE-CIC-IDS [9] and NSL-KDD [10], and CIC-Bell-DNS-EXF-2021 [11], have been used to train ML/DL models to prevent intrusions and attacks over time. However, these datasets are not focused on network traffic in a VNF-enabled system. This work introduces the VNFCYBERDATA, the first VNF dataset for cybersecurity, and the first session-level dataset in this domain, with the potential to inspire new research directions.

A VNF-based dataset is necessary due to the observed discrepancies, such as differences in throughput, packet delay, resource contention, and the hypervisor obscuring important information in the case of anomaly detection, which can change the overall behaviour of network traffic [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Whiteaker et al. [13] found that virtualisation can increase latency due to additional abstraction layers, especially in high-throughput scenarios with significant packet processing demands. Chung and Wang [12] further illustrate that while high-performance cloud systems can mitigate some latency issues through optimised architectures, the fundamental overhead of virtualisation remains a challenge. Wang and Ng [14] investigated the impact of virtualisation on network performance in Amazon EC2 data centres, observing that resource sharing among different VNFs might result in unexpected performance owing to contention for CPU, memory, and I/O resources. This contrasts with Physical Network Functions (PNFs), which typically have dedicated resources, resulting in more predictable and stable performance metrics. Gogunska et al. [15] further explored the implications of measuring traffic in a virtualised environment, emphasising that the overhead associated with virtualisation can complicate traffic measurement and analysis. This overhead can introduce additional latency, jitter, and packet processing delays, altering the behaviour or pattern of a virtualised appliance compared to the PNF counterpart. Lee et al. [16] investigated traffic anomaly characteristics in a virtualised network testbed, revealing that VNFs may exhibit different traffic patterns than PNFs. The authors note that the virtualisation layer can obscure certain traffic behaviours, making it more challenging to detect anomalies. Collectively, these studies demonstrated that the bottlenecks introduced by virtualisation, such as increased packet delays, resource contention, and hypervisor complexity, can have a considerable impact on network traffic performance when compared with PNFs. As a result, a VNF-based dataset is required to properly capture and investigate the behaviour of virtualised network devices under these described constraints, as traditional PNF-based datasets may not reflect the unique problems and performance characteristics introduced by virtualisation.

The BETH dataset [6] contains two sensor logs—kernel-level process calls and network traffic; however, it needs to provide adequate network features for traffic analysis since it contains fourteen features that do not offer diversity in investigating network traffic. The ISOT CID dataset [7] offers an even smaller number of features than BETH. Also, it follows a generic approach in labelling the dataset by not specifying the actual malicious behaviour that was captured. The ISOT CID [7] shares similarities to this work in capturing performance metrics such as CPU utilisation. The CIC-IDS2017 [8] offers an improved dataset in terms of diversity and volume; however, it poses a limitation in the number of attacks (eight cyberattacks) and a minimal number of protocols generated in the dataset (FTP, SSH, brute force SSH, DoS, etc.). The work described here captured seventy-seven protocol sets and twenty-nine cyberattacks. A similar work to [8,9] also offers an improved dataset for anomaly detection that provides a benchmark for intrusion detection based on creating user profiles with about eighty features; however, it is limited in the number of cyberattacks.

The VNFCYBERDATA dataset provides researchers with several data points to develop ML/DL models to safeguard VNF appliances. It could also serve as a guide to study or investigate the network behaviour of VNF appliances in comparison with physical network functions. During the collection of the dataset, the following considerations and actions were taken:

- All VNF environments were completely updated/upgraded to the most recent version/build before collecting the dataset; therefore, no known vulnerabilities were present.

- Not all attacks were carried out at the same time.

- Attacks were initiated from both inside (LAN) and outside (Internet) the network.

- Not all initiated attacks were successful in exploiting the VNF appliances; the aim of generating the dataset is to monitor and collect network behaviour during such attacks and regular operation, not necessarily exploit the VNF appliances.

2. Data Description

The VNFCYBERDATA dataset comprises over seven million anonymised data points with forty attributes and a target (Label) column (as seen in Table 1) collected between 03 December 2023 and 28 March 2024. The target column is multiclass in nature, with normal traffic classified as “Benign” and malicious/attack traffic classified as shown in Table 2. Table 3 shows the list of entries for each attack and the overall percentage. The link to archived data is available online.

Table 1.

The VNFCYBERDATA dataset features with description.

Table 2.

Malignant traffic classification label.

Table 3.

Total number of entries and corresponding percentages for benign traffic and each attack type.

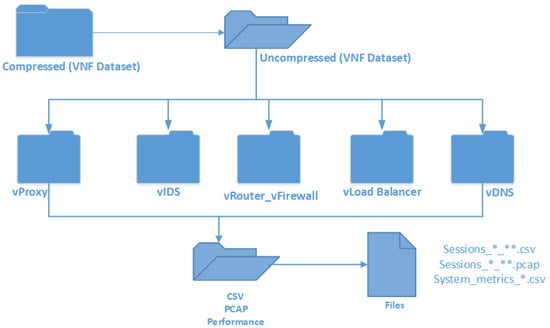

As shown in Figure 1, the folder is organised to keep data for each VNF appliance distinct. The dataset for each appliance is further divided into multiple files to avoid a single huge file for easy analysis/transfer. The vLoad balancer, vProxy, vIDS, vRouter, and vDNS are 20.64, 8.01, 6.68, 4.92, and 3.70 gigabytes, respectively. The total size of the dataset is 43.94 gigabytes. The VNFCYBERDATA dataset includes the following file formats:

Figure 1.

Folder structure of the dataset.

- PCAP format: This format includes network packet data that can be used to analyse the network properties. This comprises information about the communication, such as port numbers, IP addresses, payload sizes, protocols, and TCP flags. The format facilitates further analysis of the gathered traffic.

- CSV format: The collected packets are transformed to CSV files, which can be readily viewed in a processing application like Microsoft Excel which shows traffic information in rows and columns.

The naming structure for network traffic datasets is “sessions_#_*.csv”, where “#” denotes the numerical sequence of the file (starting from 1 to last serial number) and “*” represents the type of VNF, such as vIDS. Additionally, the dataset folders include the “performance” folder, which contains system performance measurements in CSV format. The performance data were collected for vDNS, vLoad Balancer, vRouter_Firewall, and vProxy, containing the CPU, memory, disk, and network utilisation of the VNF appliances in benign and attack scenarios.

Additionally, Table 4 shows the number of sessions captured for each protocol type/set in the dataset for each appliance. Arkime keeps track of a protocol set for a given session.

Table 4.

The number of sessions captured for each protocol type/set.

3. Methods

This Section provides a detailed explanation of the setup used to capture the VNFCYBERDATA dataset, including the hypervisors, VNF appliances, and network related details and types of cyberattacks.

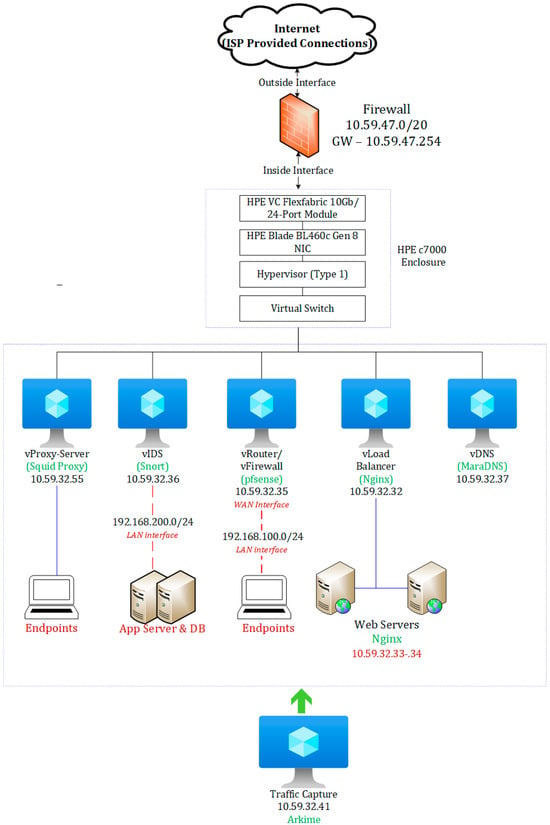

3.1. VNF Environment

The architecture in Figure 2 shows the design/layout of the environment with various VNF appliances deployed for traffic capturing while Table 5 shows details of the network addresses, operating systems, and the VNF appliances deployed. The environment consists of two Type 1 hypervisors, ESXi-Server1 and ESXi-Server2, both of which are deployed on separate HPE blade servers (ProLiant BL460c Gen 8). A firewall device connects to the Internet Service Provider (outside interface) and the LAN network (inside interface) and connects to the HPE Virtual Connect Flexfabric 10 GB/24-port module on the HPE c7000 enclosure, which then connects to the mezzanine card on the BL460c blade server and then the hypervisor’s virtual switch (vSwitch).

Figure 2.

The environment for capturing VNFCYBERDATA dataset.

Table 5.

Network information of VNF appliances deployed.

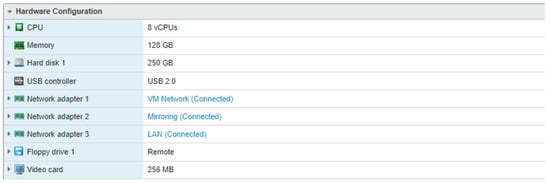

Furthermore, two vSwitches are configured at the hypervisor level for this setup for all appliances. As shown in Table 6, each VNF appliance is connected to two vSwitches: the “VM Network” vSwitch handles standard VNF traffic with an IPv4 address assigned to the interface, while the “Mirroring” vSwitch is configured to intercept and read all network packet hence, operating in promiscuous mode. For vRouter_vFirewall and vIDS, an additional vSwitch is set up to carry network traffic for an internal subnet–LAN interface as seen in Figure 3.

Table 6.

vSwitch connecting the appliances and capture solutions.

Figure 3.

Image showing an example of how the vSwitch are connected to a VNF appliance.

A capture solution—Arkime [18]—was deployed to capture and subsequently extract network information in PCAP and CSV formats. Arkime is installed separately on Ubuntu 22.04 LTS operating system and linked to the “Mirroring” vSwitch.

Inbound traffic to the Arkime is blocked using a host-based firewall (Ubuntu ufw), leaving only outbound traffic for collecting network traffic data. Figure 3 shows an example of the connection of an appliance to the vSwitches in Table 6.

In addition to the information in Table 5, the following resources were deployed or used:

- Public DNS: Google DNS (8.8.8.8), Cloudflare DNS (1.1.1.1), Quad9 DNS (9.9.9.9), OpenDNS (208.67.222.222, 208.67.220.220). vDNS is sometimes used for name resolution with the previous public DNS setup as forwarders.

- Kali Linux VMs: 10.59.32.52, 10.59.32.53, 10.59.32.51, 10.59.32.50

- VM for traffic capturing (Arkime): 10.59.32.41.

- Internal subnet connected to vRouter_vFirewall: 192.168.100.0/24.

- Internal subnet connected to vIDS: 192.168.200.0/24.

- Internet port forwarding from public IP to 10.59.32.32 (vLoad Balancer) on port 443 and 80.

- Internet port forwarding from public IP to 10.59.32.37 (vDNS) on port 53.

- vProxy is set up to allow client access on port 8080.

- Domain name registration techtechinfra.tech and vnfdataset.info. Also includes subdomains like www.techtechinfra.tech, vpn.techtechinfra.tech, kali.techtechinfra.tech.

- Public SSL certificate installed on vLoad Balancer and web servers.

3.2. Benign Traffic

For all the VNF appliances, the traffic capture process began with the benign traffic and progressed to malicious traffic capture; however, while attacks are being simulated, benign traffic is also being generated simultaneously. The following describes how benign traffic was generated for each VNF appliances.

- vLoad Balancer: Benign traffic was generated using Apache JMeter [19], two custom scripts [20]. HTTP traffic was generated both internally and outside (Internet) of the network using the JMeter and the custom script. Internet traffic was based on port forwarding. Inbound traffic on the domain name www.techtechinfra.tech on port 443 and 80 was forwarded to the vLoad balancer.

- vDNS: All internal name resolution was performed using vDNS which generated numerous benign traffic. Further name resolution was carried out using a custom script found in [21]. In addition, a port forwarding rule was created to redirect all DNS traffic on the well-known port 53 to the vDNS appliance.

- vRouter_vFirewall, vProxy, and vIDS: The vRouter and the vIDS were set up with two interfaces each, with one interface serving as the internal interface that connects to internal machines (Figure 1). For vProxy, we set up all the devices in the lab environment to connect to the internet with the vProxy on port 8080.

3.3. Details of Attack

For all VNF appliances, the traffic capture process began with benign traffic and progressed to malicious traffic capture. Malicious traffic capture was carried out in two stages: stage one involved attacks without deploying malware samples, and stage two involved the deployment of several types of malwares on each VNF appliance or corresponding environment (such as VMs attached to the VNF appliances). Table 7 and Table 8 provide a summary of malware hash and each attack on the VNF appliances, including the number of data points recorded, respectively. The malware samples were carefully chosen to reflect MITRE ATT&CK [22] tactics displayed by conventional malware such as persistency, directory discovery, defence evasion, reconnaissance, lateral movement, command and control, privilege escalation, file encryption, and collection.

Table 7.

The type of malware attack, behaviour, and corresponding hash function for each VNF appliance.

Table 8.

The entries of each of the VNF appliances.

As previously stated in the Section 1, the primary goal of this dataset is to record the network’s behaviour throughout different attacks. It is worth noting that not all attacks successfully exploited the VNF appliances. The following gives a summary of the attack states observed:

- Malware Attacks: All malware attacks were carried out internally by intentionally infecting the VNF appliances with malware samples of various types, as shown in Table 7. These attacks usually stemmed from internal malicious content or were delivered via malicious emails.

- DoS Attacks: The DoS attacks against the vLoad Balancer, vRouter, and vIDS, vProxy did not consistently drain system resources. The vLoad Balancer’s performance was captured in the performance dataset, allowing for comparing its performance under attack scenarios and everyday operations. Aligning the timestamps in the attack and performance datasets can provide insight into the overall behaviour of the network during attack and normal operations.

- DNS Attacks: DNS-related attacks, including DNS exfiltration, DNS spoofing, and DNS amplification attacks, were carried out successfully.

- Web Application Vulnerabilities: Attacks such as directory traversal, injection, SQL injection, unrestricted file uploads, and remote code execution were successfully exploited due to vulnerabilities in the web application.

- Unsuccessful Attacks: XSS and brute force attempts were unsuccessful.

- Both ARP spoofing and Man-in-the-Middle (MiTM) attacks were successfully executed within the network. In some situation these attacks disrupted the connectivity in the entire hypervisor as the devices may remain unresponsive over a period of time.

3.4. Labelling of Dataset

The labelling of the VNFCYBERDATA dataset entails precisely establishing the ground truth which is labelling the dataset to either benign or attack class labels identified in Table 2. The labelling of the dataset was carried out using the following approaches:

- Labelling traffic begins with manual inspection to discover patterns. Once identified, a Python script [23] labels the resulting csv file. This procedure is continued until all patterns are labelled. When the script cannot be used to classify a pattern, it is manually labelled based on observed pattern behaviour. Furthermore, the session was assessed using Arkime and WiresShark [24] for easy traffic pattern identification.

- External threat intelligence was utilised in analysing traffic behaviour in addition to the manual inspection of traffic. Tools such as Virustotal [25], AbuseIPDB [26], Who.is [27], Wireshark, Mx Toolbox [28], and Shodan [29] were leveraged to identify known malicious IPs, subdomain and domain names, and attack patterns. External intelligence was mostly used in situations where an observed pattern could not be established and required further study.

- VNF appliance logs: There are events where logs from VNF appliances were correlated with traffic captured in Arkime to fully understand the overall traffic behaviour. This approach gave better insight to identified traffic with patterns that could not be identified easily. Such situations were utilised in relation to Nginx logs (vLoad balancer) and Snort logs (vIDS).

It is worth noting that Arkime does not have the capacity to collect system performance measures, so a custom script [30] was created to acquire the required information. The timestamp generated in the collected system performance dataset allows the performance metrics dataset to be correlated with the network dataset. In addition, to protect privacy, public IP addresses were anonymised using private class B IP addresses, with the exception of public IP addresses for DNS resolutions such as Google DNS and OpenDNS.

Author Contributions

B.A. helped in the conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, validation, traffic collection, labelling of the dataset, analysis and writing of the original draft. V.B. helped in the conceptualisation, review, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank the Malta Digital Innovation Authority (MDIA) and Tertiary Education Scholarship Scheme (TESS) from the Ministry of Education, Sport, Youth, Research and Innovation Malta for funding the tuition of the first author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset is available online at https://figshare.com/s/f065022eb85701278c58 (accessed on 2 October 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chaudhry, S.R.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Cahill, V.; Collier, M. A measurement study of offloading virtual network functions to the edge. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 1565–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emu, M.; Yan, P.; Choudhury, S. Latency Aware VNF Deployment at Edge Devices for IoT Services: An Artificial Neural Network Based Approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops), Dublin, Ireland, 7–11 June 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leivadeas, A.; Kesidis, G.; Ibnkahla, M.; Lambadaris, I. VNF Placement Optimization at the Edge and Cloud. Future Internet 2019, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, A.L.É.; Macedo, E.L.C.; Josué, M.I.P.; Barbalho, H.; Delicato, F.C.; Muchaluat-Saade, D.C.; Pires, P.F.; Mattos, D.P.d.; Oliveira, A.C.B.d. A Novel Strategy for VNF Placement in Edge Computing Environments. Future Internet 2022, 14, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.L.; Battisti, A.L.; Macedo, E.L.; Pires, P.F.; Muchaluat-Saade, D.C.; Delicato, F.C.; Oliveira, A.C. Dynamic and Mobility-Aware VNF Placement in 5G-Edge Computing Environments. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 9th International Conference on Network Softwarization (NetSoft), Madrid, Spain, 19–23 June 2023; pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highnam, K.; Arulkumaran, K.; Hanif, Z.; Jennings, N.R. BETH Dataset: Real Cybersecurity Data for Anomaly Detection Research. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2021, 3095, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aldribi, A.; Traoré, I.; Moa, B.; Nwamuo, O. Hypervisor-based cloud intrusion detection through online multivariate statistical change tracking. Comput. Secur. 2020, 88, 101646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafaldin, I.; Lashkari, H.A.; Ghorbani, A.A. Toward Generating a New Intrusion Detection Dataset and Intrusion Traffic Characterization. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP), Funchal, Portugal, 22–24 January 2018; Available online: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ids-2017.html (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- UNB. IDS 2018 Datasets. Available online: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ids-2018.html (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Travallaee, M.; Bagheri, W.; Lu, W.; Ghorbani, A. A Detailed Analysis of the KDD CUP 99 Data Set. Available online: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/nsl.html (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Mahdavifar, S.; Salem, A.; Victor, P.; Razavi, A.; Garzon, M.; Hellberg, N.; Habibi Lashkari, A. Lightweight Hybrid Detection of Data Exfiltration using DNS based on Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 the 11th International Conference on Communication and Network Security, Weihai, China, 3–5 December 2021; pp. 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, W.-C.; Wang, Y.-H. The Effects of High-Performance Cloud System for Network Function Virtualization. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteaker, J.; Schneider, F.; Teixeira, R. Explaining Packet Delays under Virtualization. Comput. Commun. Rev. 2011, 41, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ng, T.S.E. The Impact of Virtualization on Network Performance of Amazon EC2 Data Center. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 14–19 March 2010; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gogunska, K.; Barakat, C.; Urvoy-Keller, G.; Lopez-Pacheco, D. On the Cost of Measuring Traffic in a Virtualized Environment. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 7th International Conference on Cloud Networking (CloudNet), Tokyo, Japan, 22–24 October 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Abe, H.; Hirotsu, T.; Umemura, K. Traffic Anomaly Analysis and Characteristics on a Virtualized Network Testbed. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2011, 94, 2353–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedyalkov, I. Performance comparison between virtual MPLS IP network and real IP network without MPLS. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. Syst. 2021, 12, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkime. Arkime—Full Capture Solution. Available online: http://arkime.com (accessed on 11 July 2023).

- Apache. Apache JMeter—User’s Manual: Building a Web Test Plan. Available online: https://jmeter.apache.org/usermanual/build-web-test-plan.html (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Ayodele, B. BelieveDjango/http_request. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/BelieveDjango/http_request (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Ayodele, B. BelieveDjango/dns_request. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/BelieveDjango/dns_request (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- MITRE ATT&CK®. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/ (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Ayodele, B. BelieveDjango/labelling_dataset_python. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/BelieveDjango/labelling_dataset_python (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Wireshark Go Deep. Available online: https://www.wireshark.org/ (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Virustotal. Home. Available online: https://www.virustotal.com/gui/home/upload (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- AbuseIPDB. IP Address Abuse Reports—Making the Internet Safer, One IP at a Time. Available online: https://www.abuseipdb.com/ (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- WHOIS. Search, Domain Name, Website, and IP Tools. Available online: https://who.is/ (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- MxToolbox. DNS Lookup Tool. Available online: https://mxtoolbox.com/Public/Content/Toolhandler.aspx?command=a (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Shodan. Available online: https://www.shodan.io (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Ayodele, B. BelieveDjango/system_performance_metrics. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/BelieveDjango/system_performance_metrics (accessed on 24 January 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).