1. Introduction

Brain disorders impact a large portion of the world’s population and are caused by a complex interplay of biological, social, and psychological factors. Autism is one of these neurodevelopmental disorders that typically appears in children [

1].

According to research conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO), the treatment of mental disorders has not kept pace with the increase in these disorders, which have lasting and detrimental effects on the lives of affected children and their families, as well as on society as a whole [

2,

3].

The detrimental effects of ASD on families and children include difficulties adjusting to new environments, difficulties in the classroom, increased levels of stress and psychological strain, and, to differing degrees in different cultures, societal and economic setbacks [

2]. This is reflected in the rise in costs associated with this group, including social, educational, and healthcare support; costs associated with low financial return as a result of unemployment; and costs associated with caring for people with ASD across all age groups [

4].

In order to identify the root causes of autism, medical intervention from experienced physicians is necessary. Observing the behavior of affected children in various settings and the challenges they face when interacting with their surroundings are the main components of an autism diagnosis [

4].

Although it shares symptoms with other mental illnesses, ASD is a complicated disorder in and of itself. Therefore, it is crucial to diagnose individuals with ASD using suitable evaluation tools [

3]. According to Radhakrishnan [

5], there are a variety of tests that may be used to determine whether a child has autism, including behavioral evaluation and occupational therapy screening. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) [

6], and the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised (ADI-R) [

7] are some of the clinical procedures commonly used to evaluate autism spectrum disorder. But we must not forget that these evaluations are not interchangeable; they each have their own set of strengths and weaknesses. These evaluations are defined by the amount of time they take, the breadth of the questions they cover, and the requirement that licensed professionals must administer them [

5,

8,

9].

Several time–frequency analysis methods can be applied to biomedical images and data in order to identify and diagnose a wide range of human disorders [

5,

10]. In addition, several anomalies in brain electrical activity can be detected using electroencephalogram (EEG) tests and analyses [

11,

12,

13].

EEG can be utilized to assist with the early detection, management, and prevention of autism by revealing complex relationships. Early in the first year after birth, EEG waveforms, in particular the gamma

band from the frontal brain lobe, can differentiate ASD from normal controls [

14]. In addition, statistical learning approaches can use the non-linear properties of EEG to differentiate between individuals with ASD and those without [

3,

15].

Indeed, there have been tremendous improvements in the EEG areas of diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of people with ASD, particularly due to the use of artificial intelligence in autism research, detection, and classification [

16]. As an essential part of artificial intelligence, machine learning uses different algorithms like support vector machine (SVM), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), and decision tree (DT) [

5,

17].

A subfield of machine learning is deep learning, which uses artificial neural networks designed to mimic the structure of the human brain. Deep learning is highly effective in image identification, speech analysis, and natural language processing, all of which impact our ability to understand and treat autism [

5,

17]. Neural networks, including recurrent neural networks (RNNs), particularly long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, have been widely used to analyze time-series data. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been utilized to analyze neuroimaging data and video and have improved diagnostic accuracy while also reducing the influence of subjectivity [

14,

18,

19,

20].

Neurobiological studies have recently attracted much attention. Thus, this study integrates statistical analyses with machine learning and deep learning algorithms to capture the heterogeneity of autism. The EEG dataset contains recordings from mild ASD patients, moderate ASD patients, severe ASD patients, and typically developing children. Conventional filters and discrete wavelet transforms (DWTs) are used in the preprocessing stage to denoise the EEG data. Relative power frequency-domain features are extracted to obtain the spectro-spatial EEG profile. The first part of this study looks at relative power features to create spectral neuro-markers, using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Pearson’s correlations to identify spectro-spatial ASD profiles in various brain regions. A comparative study is then conducted to autonomously determine ASD severity from EEG signals using DT machine learning-based classification algorithms and LSTM deep learning-based classification models.

The objectives of this study are to analyze the relative power features using statistical analyses to characterize the spectro-spatial profile of ASD severity using EEG data and to assess the effectiveness of machine learning and deep learning models in determining ASD severity. Thus, it aims to discriminate autism through the characterization of temporal changes in physiological EEG activity in these individuals by identifying EEG alterations in children with ASD and assessing aspects of their responses in relation to the severity of ASD, according to a conventional statistical method of ANOVA that is employed to compare differences in ASD severity through relative power spectrum coefficients between children with ASD and neurotypicals. Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation approach is employed to define the correlation that exists between adaptive behaviors and autism severity in order to determine the dimensions of these aspects. Furthermore, a DT and an LSTM network are employed for time-series modeling, separating sequences of brain activity associated with diagnosing and treating autism.

The combination of statistical analyses with machine and deep learning techniques improves not only the quality of the outcomes derived from studies on autism but also the prospect of discovering the spectro-spatial profile of ASD severity.

This study makes three contributions: it is the first to use a combination of relative power features to develop a spectro-spatial profile identification for ASD severity in brain regions using statistical analyses; second, it is the first study that automatically manages ASD severity as a multiclassification problem of autism severity, specifically separating mild, moderate, and severe autistic symptoms from typically developing control subjects; and third, the ASD EEG-based dataset has never been used before.

2. Related Works

Clinical diagnostic criteria rely on behavioral observations and therefore often result in delayed therapeutic intervention and less-than-favorable outcomes for patients with ASD [

21,

22]. Recently, interest has shifted toward using neuroimaging techniques, like MRI and fMRI, and neurophysiological tools, including EEG, to objectively define ASD [

23,

24].

EEG has several important advantages, such as its non-invasive nature, temporal resolution, and ability to record dynamic neural activity that is fundamentally related to deficits observed in individuals with ASD [

25,

26]. The related literature has examined the use of EEG features like power spectral densities, coherencies, and complexity measures to distinguish between ASD patients and healthy controls [

27,

28,

29,

30].

In recent years, ASD classification has been investigated using features extracted from EEG signals with the aid of machine learning algorithms. Features derived from raw data can be used to train a machine learning classifier to diagnose ASD [

31].

However, the majority of existing studies on EEG-based ASD diagnosis relied solely on binary classification (ASD vs. control) or did not consider the severity of symptoms at all [

32,

33]. More integrative methods need to be developed to accurately quantify the pathology of ASD from EEG signals, monitor the progression of the disease, and provide more targeted intervention and treatment plans [

34,

35].

Brihadiswaran [

17] discussed EEG-based ASD classification using machine learning approaches and highlighted the need for early identification and a standardized method of diagnosing the disorder. Moreover, Heunis et al. [

36] applied recurrence quantification analysis (RQA) with linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and support vector machine (SVM) classifiers. Haputhanthri et al. [

37,

38] applied statistical features with SVM, naive Bayes (NB), and random forest (RF) and emphasized the potential of more complex mathematical techniques through the investigation of Shannon entropy with the linear regression (LR) classifier. However, researchers have also used machine learning to analyze genetic data and identify biomarkers associated with autism. This has helped us learn more about the genetic profile of the disorder [

39].

Deep learning’s rapid growth demonstrates its ability to extract features, thereby increasing the accuracy of classification, reducing human intervention and data processing times, and helping doctors in this field with diagnoses and filling gaps in traditional approaches. Advanced neural networks are now being used to analyze EEG datasets related to autism, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which can identify interaction patterns in large-scale neuroimaging data [

40].

Thus, new research using deep learning could help us determine how EEG data recorded from people with neurological disorders such as autism can be more effectively utilized. Based on exploratory research conducted over the past few years, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) have shown that EEG data can be used to detect neurological disorders. They are capable of learning from data and sometimes outperform traditional machine learning methods [

41,

42].

Indeed, deep learning enables the extraction of additional valuable information from EEG signals. For instance, Hasan et al. [

43] applied CNN, DNN, and LSTM models to demonstrate their effectiveness in handling complex data like EEG signals. Also, Al-Qazzaz et al. [

18] used EEG to determine the severity of ASD in patients after encoding EEG signals into images to make them easier to interpret by deep learning models. They showed that using both EEG features and images improved classification accuracy when using a pre-trained SqueezeNet CNN model [

18].

Several studies have used EEG-based datasets to address ASD-related challenges.

Table 1 presents a summary of research on distinguishing between ASD and normal controls using EEG analysis with the aid of machine and deep learning techniques such as SVM, NB, RF, LR, and DNN [

5,

37,

38,

44,

45].

For machine learning, feature extraction techniques have included statistical measures, power spectral densities, and entropy [

5,

37,

38,

44,

45]. In these studies, classification accuracy ranged from 56% to 94%. However, most of these studies relied on machine learning classifiers, indicating the ability of such methods to distinguish specific patterns between ASD individuals and those who are typically developing. Deep learning-based approaches have also achieved high classification accuracy, suggesting that deep learning could enhance diagnostic tools and guide future therapeutic interventions. While previous studies have utilized deep learning to distinguish between typically developing children and autistic individuals, what sets our study apart is its focus on the multiclassification problem of autism severity, specifically distinguishing mild, moderate, and severe autistic symptoms from typically developing controls.

Table 1.

Related works.

| Studies (Year) | Extracted Features | Classification Approaches | Classification Accuracy (%) |

|---|

| Haputhanthri et al. [37] | Statistical features (mean and standard deviation) | SVM, NB, RF | 53.33, 73.33, 66.66 |

| Haputhanthri et al. [38] | Shannon entropy, statistical methods | LR | 94 |

| Radhakrishnan et al. [5] | Automatic feature extraction and classification | DNN | 81 |

| Garcés et al. [44] | Power spectrum | ElasticNet | 56, 64 |

| Hou et al. [45] | t-test, PCA, ReliefF, Chi-square | SVM | 74.1 |

In general, the studies indicate a progression from empirical-type methodologies to machine learning-based methodologies that could be useful in the diagnosis of ASD, but there is still a lot to be done in this area in terms of having a standardized method and increasing the accuracy of diagnostic prediction across different datasets.

This research seeks to fill this gap by adopting an interdisciplinary approach that uses statistical methods and artificial intelligence, including machine learning and deep learning models, to assess ASD severity from EEG signals. Hence, this work provides an objective and more direct estimation of ASD severity, which could potentially be helpful for patients in terms of diagnosis and treatment.

3. Materials and Methods

Preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification are all necessary steps in processing and analyzing recorded EEG signals in order to evaluate ASD severity using EEG signals.

Figure 1 is a schematic depicting the proposed strategy.

The implementation was carried out on a computer with a 13th Gen Intel Core i7-13650HX 2.6 GHz CPU, which offers high processing power appropriate for model training and numerical calculations. To expedite the LSTM model’s training, we employed an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU. This GPU made it possible to handle large-scale EEG datasets efficiently by drastically cutting down on training time. During model training and validation, the system’s 16 GB of RAM allowed for seamless data handling and processing. In order to ensure compatibility with MATLAB R2024b and its related toolboxes, the implementation was conducted in a Windows 11 environment.

3.1. ASD EEG-Based Dataset

The EEG dataset consists of recordings from forty subjects, including ten normal subjects, comprising five females and five males, with an average age of 8.545 ± 1.1 years; ten mild autism spectrum disorder patients, comprising four females and six males. In the case of moderate ASD, 10 cases, where the average age of the cohort is 8.364 yrs old with a standard deviation of 0.8 yrs, 3 of the ten are female, and 7 are male, with a mean age of 8.727 yrs old and standard deviation of 0.98 yrs old; and 10 cases of severe autism spectrum disorder, where the average age of the cohort is 8.727 yrs old with a standard deviation of 0.98 yrs.

The patients were the participants in the research conducted both at the Neurophysiology Department of the Baghdad Teaching Hospital and the Autism Centre of the Paediatric Hospital in Medical City, Baghdad, Iraq. No children included in the ASD had taken medication within the two weeks before the recording of the EEG. The children of the control group did not have any family record of a neurological or mental disorder and were enrolled in normal, health promoting schools.

The interviews of the children were done by a psychiatrist based on the provisions set in

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) [

46]. Moreover, subjects were assessed for the severity of ASD based on the Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS-3) [

47].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of assessing ASD severity from EEG signals.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of assessing ASD severity from EEG signals.

A device manufactured in Japan by Nihon Kohden was required to record a 10 min EEG signal. Nineteen Ag/AgCl electrodes were laid as per the 10–20 system and two reference electrodes were placed on the mastoid bones. The data was collected with an impedance of less than 5 K if the impedance, a resolution of 12 bits and a sampling rate of Hz. When the recording was recorded, the bandpass filter was adjusted between 0.1 and 70 Hz and the notch filter was adjusted to 50 Hz. The data was filtered to be analyzed in the range of bandpass filters of 0.1 to 64 Hz.

This study followed the 1964 Helsinki Declaration with all its amendments, and the principles of the medical school and the institutional research committee, which was held in the College of Medicine of the University of Baghdad. The consent of the parents of the children used in the study was obtained after all the necessary information was received.

3.2. Preprocessing

In the initial stage of processing, conventional filters, including a notch filter at 50 Hz, were employed to remove interfering noise, and a bandpass filter with a frequency range of 0.1–64 Hz was used to limit the band of the recorded EEG signals [

48,

49].

After that, each of the 19 denoised EEG channels had its signal split into non-overlapping epochs of 5 s length, and each epoch contained samples, as the sampling frequency was set at Hz. Segmenting the EEG channels significantly increased the amount of data available for analysis, effectively enhancing the dataset’s dimensionality.

The 5-second segmentation was preliminary and supported by a trade-off between temporal precision and EEG data analysis. EEG signals exhibit large frequency changes; therefore, 5-second is enough to capture brain electrical activity from delta to (

,

,

, and

) bands. Each 5-second segment was expected to capture EEG signal transients and structures. This study used a length of time that has been employed in other EEG analysis-based studies to discriminate neurophysiological properties for distinct states or disorders, including ASD [

18,

50,

51]. To maintain neurophysiological features for meaningful segmental assessment, all channels were filtered before obtaining the segments. In the next step, all the attributes were extracted from each 5-second sequence and related to the 10-min dataset.

As a denoising approach, wavelet transforms are widely used. Recently, they have been utilized to process non-stationary data such as EEG signals. Zikov et al. and Krishnaveni et al. utilized wavelet transforms to eliminate ocular artifacts [

52,

53], and other studies have demonstrated that discrete wavelet transforms (DWTs) are effective for denoising and feature extraction. Therefore, DWTs were used in this study to denoise the raw EEG data. Due to their time-invariant qualities and enhanced time resolution, the DWT is a powerful method for recognizing patterns, detecting changes, and extracting features through EEG wave decomposition [

54,

55].

Because of their impact on denoising and decomposition, choosing the mother wavelet and decomposition level is crucial. The mother wavelet is ideal for identifying changes in EEG signals and offers superior accuracy compared to other wavelets. Furthermore, its sinusoidal shape and increased stretch on the time axis make it an attractive choice for EEG denoising [

56,

57].

The coiflet mother wavelet order 3 (coif3) was used in this study, as it is perfect for spiky artifact removal, which includes eye movements/blinks and muscular movements [

58]. Moreover, the universal threshold was used as the main thresholding method in this study [

56,

57].

3.3. Feature Extraction

The time-invariance qualities of the signal are crucial, and the DWT can preserve these, particularly when locating and recognizing changes or transient features in the EEG [

54,

59,

60].

These benefits are a result of the DWT method’s multi-resolution analysis characteristic, which is why it is widely used by researchers to analyze EEG data [

58]. Therefore, the DWT technique was employed to denoise and decompose the EEG signals in this study.

For this reason, the impulse responses of the EEG signals were separated into low-pass and high-pass filters according to the selected wavelet criteria. Coefficients of approximation (A), containing low-frequency components, are produced by low-pass filtering. The detail (D) coefficients, containing high-frequency components, are produced by high-pass filtering. Consequently, the DWT is a suitable technique for acquiring brain rhythms with various frequency components [

56,

57].

Each filter halved the signal frequency because the input EEG signal was 256 Hz. As a result, 128 Hz was the frequency of the low-pass and high-pass filters. Following the filtering phase, the EEG signals were divided into their components using the DWT technique and the coif3 mother wavelet.

Since the EEG input used in this experiment had a sample rate of 256 Hz, five decomposition levels were necessary to extract the desired brain rhythms. The decomposition (D1) occurred at a frequency of 64–128 Hz, which was considered noise; however, D2, D3, D4, and D5 represented the (, , , and ) rhythms at 30 to 64, 16 to 30 Hz, 8 to 16 Hz, and 4 to 8 Hz, respectively. The approximation (A5) also represented the wave at 0 to 4 Hz.

Previous studies have revealed changes in the (, , , and ) bands of neural oscillations, leading researchers to posit that EEG-based markers may help improve the diagnosis and assessment of ASD.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

To begin with, the first step involved categorizing the 19 channels of the EEG data of healthy people and those with different severity of ASD into 5 recording regions that represented different parts of the cerebral cortex in the scalp. These were the channels of the frontal, temporal, parietal, central and occipital respectively. Normality was then tested using KolmogorovSmirnoff. There were two statistical analysis sessions carried out in SPSS 23.

3.4.1. ANOVA

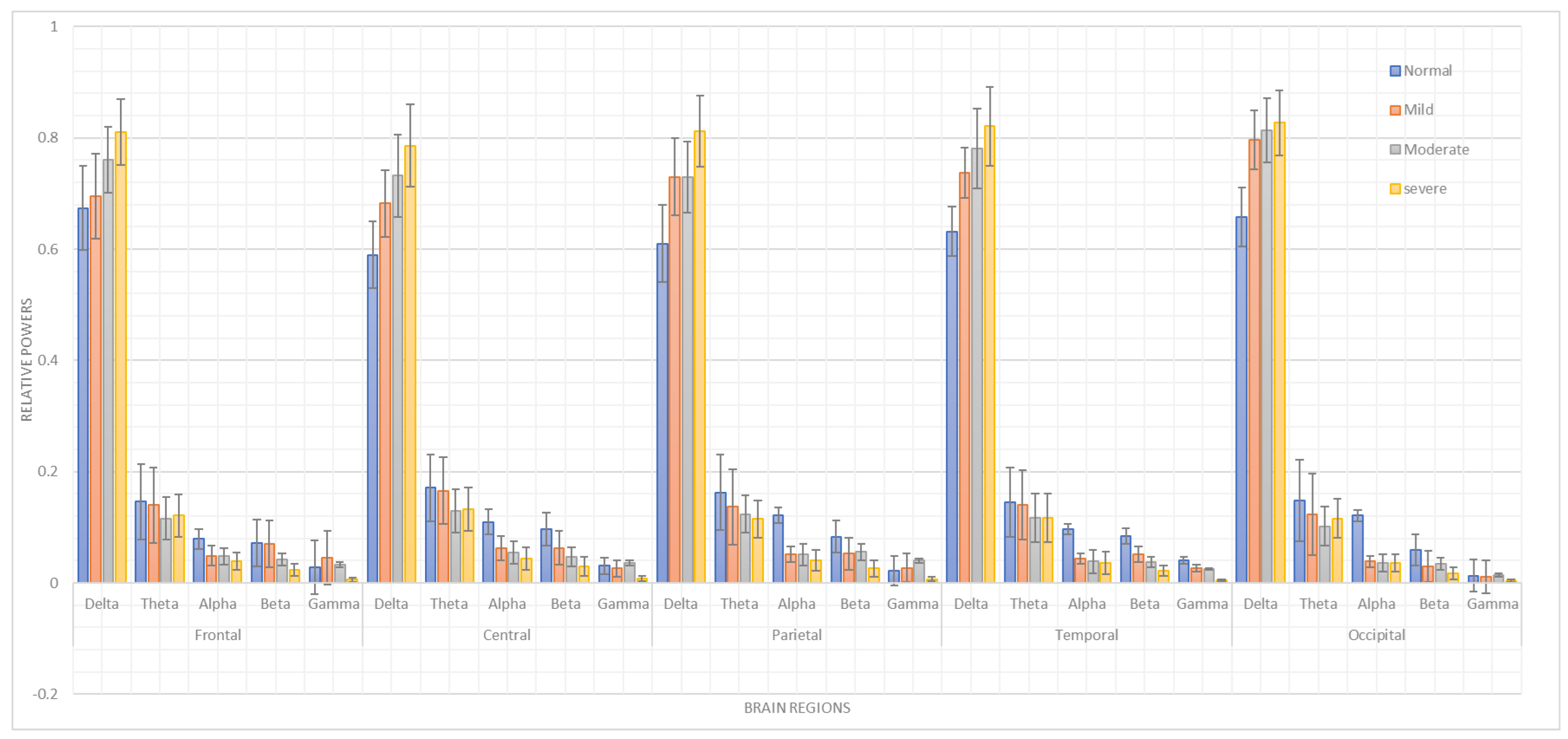

The first statistical analysis conducted was a two-way ANOVA. The dependent variable was the relative power in (, , , , and ), while the independent variables were the group factors (healthy age-matched typically developing children, mild ASD, moderate ASD, and severe ASD) and the brain lobes (frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital). Post hoc comparisons were made using Duncan’s test. A significance level of was established for all statistical tests.

3.4.2. Pearson’s Correlation

Additionally, in order to assess the correlation of the proposed features, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was utilized to calculate correlations between the high-frequency relative powers (, , and ) and the low-frequency band relative powers ( and ). Patients with mild, moderate, and severe ASD were the subjects of the Pearson’s correlation session. Two levels of significance were established for Pearson’s correlations: and .

3.5. Classification

To distinguish between individuals with ASD and typically developing children, machine learning and deep learning classification models were used. Initially, the frequency-domain relative power features were extracted from the EEG signals as part of this research. Then, the DT machine learning classifier and the LSTM RNN deep learning model were applied to obtain the classification results.

3.5.1. Machine Learning Classification

The DT served as the final stage for distinguishing between individuals with ASD and typically developing children. Utilizing decision trees enables a high degree of interpretability through their decision structure, and they handle numerical and categorical inputs well, making them suitable for this task. Decision trees provide great benefits in clinical environments since they offer reasonable model decisions combined with simple communication for practitioners. Field-based research on ASD classification has previously used decision trees [

61,

62,

63,

64].

The DT is a recursively generated tree that uses the supervised classification technique to divide a large problem into smaller subproblems. In a DT, each leaf node is assigned a class label, while internal nodes and the parent node utilize attribute testing criteria to divide records according to their features [

65]. The number of trees does not significantly impact classification accuracy. In this investigation, an ensemble of 100 binary decision trees was used.

3.5.2. Deep Learning Classification

In this study, the RNN deep learning classification model was utilized to distinguish between individuals with ASD and typically developing children. LSTM effectively identifies temporal connections within sequential data, such as EEG signals, thereby enabling appropriate analysis for time-series data. LSTM networks were used since they have a remarkable ability to identify long-term dependencies and, when combined with EEG data oscillations, can indicate ASD severity. Several studies have used LSTM networks for neurophysiological data classification, supporting our choice [

66,

67,

68,

69].

RNNs suffer from the vanishing gradient problem, making them difficult to use for practical purposes. However, LSTM helps reduce the multiplication of gradients smaller than zero [

70]. An LSTM consists of the following components:

Input gate: uses the

activation function, as given by Equation (

1):

where the current input is

and the previous cell’s output is

.

The input gate, a sigmoid-activated node in the hidden layer, is expressed in Equation (

2):

The output of the input gate is

Forget gate: delays the inner state of the LSTM by one time step and adds it to Equation (

3). This creates an internal recurrence loop that learns the relationship between the inputs given at various times. This stage includes sigmoid-activated nodes that decide which previous state should be remembered. The forget gate is expressed in Equation (

4):

The output of this stage is obtained using Equation (

5):

where

represents the inner state of the previous cell.

Output gate: is composed of a

squashing function and an output sigmoid function, as expressed in Equation (

6):

The cell’s output is calculated as

where

,

, and

represent the input bias, input weight, and preceding cell’s output for each stage. The weights and biases are set during the training phase.

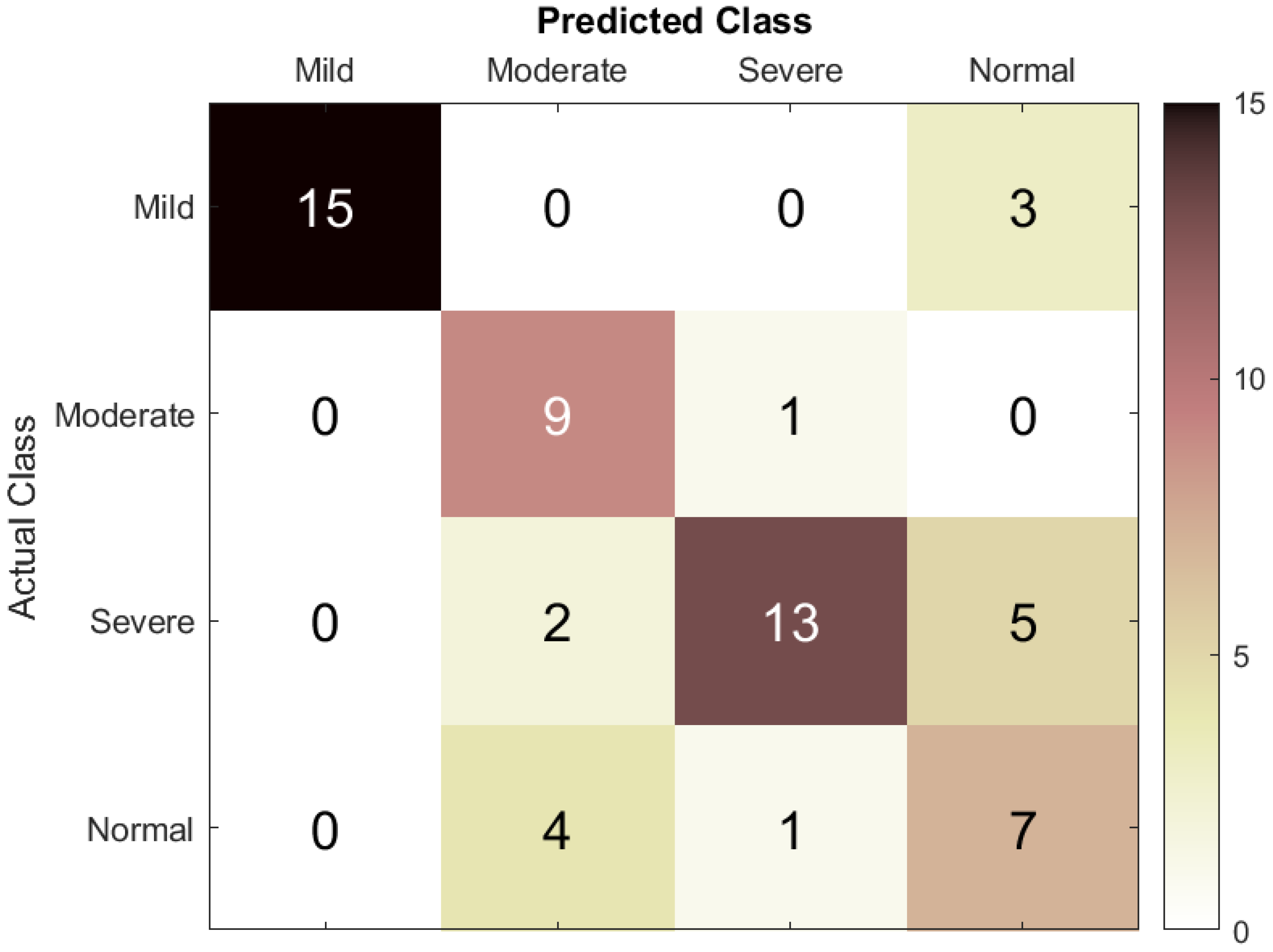

Ten mild, ten moderate, and ten severe ASD patients, as well as ten typically developing children, were classified using the LSTM RNN model with an initial input size of per feature. To classify patients as normal, mild ASD, moderate ASD, or severe ASD, the LSTM RNN contained 100 hidden units and the following layers: a feature input layer, a fully connected layer, the rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function, a softmax layer, and lastly, a classification output layer. Using a learning rate of 0.001 and a batch size of 64, the RNN was trained using the adaptive moment estimation (Adam) optimizer across 30 epochs.

3.6. Model Evaluation Metrics

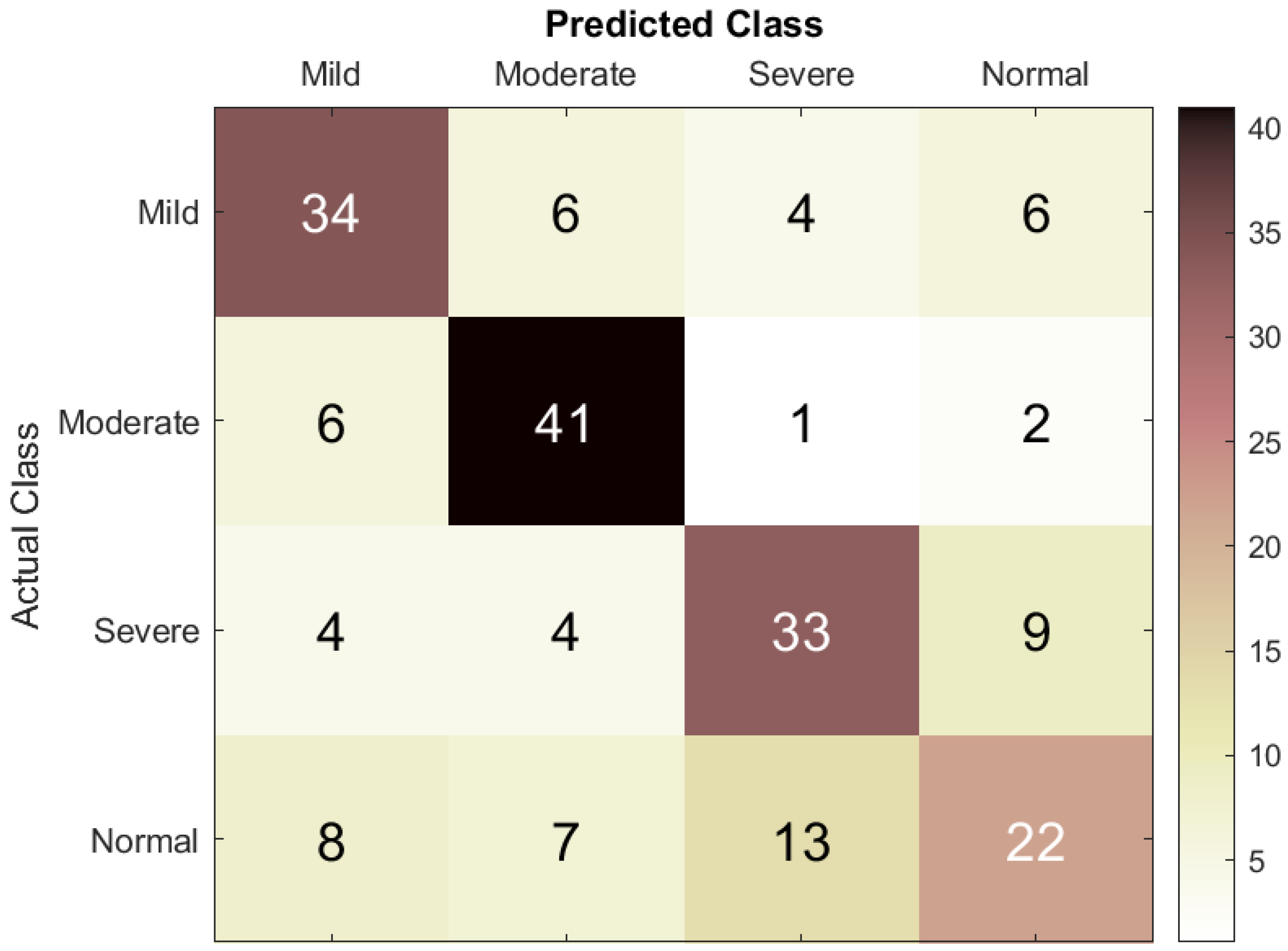

In this research, classification accuracy was calculated by first using the DT machine learning classification model and then the LSTM RNN to classify the EEG dataset into four classes: mild ASD, moderate ASD, severe ASD, and normal controls. To prevent class imbalance, the dataset was split into for training and validation and for testing (80:20).

The scope of the evaluation was expanded to include segment- and event-based performance results. To assess ASD prediction performance, the true positive (TP) rate was defined as the number of EEG segments correctly classified as belonging to a specific ASD category, the true negative (TN) rate as the number of segments correctly classified as not belonging to that category, the false positive (FP) rate as the number of segments incorrectly classified as belonging to the category, and the false negative rate as the number of segments incorrectly classified as not belonging to it. These parameters were used to calculate accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1-score.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to assess the degree of ASD severity based on a statistical analysis of patient data and the use of artificial intelligence frameworks. The observed results emphasize the usefulness of EEG as a diagnostic method for ASD, which can provide valuable data on the electrical manifestations of the disorder depending on the extent of the symptoms. This study also demonstrated the use of statistical analysis to obtain the relative power features for the spectro-spatial profile of ASD severity. The statistical analysis of EEG data, including two-way ANOVA and Pearson’s correlation analyses, identified differences in the EEG patterns of mild ASD, moderate to severe ASD, and TD children. Most significantly, and activity, aligned with , , and activity, differed between the regions, manifesting characteristic neurophysiological patterns for different ASD severities.

Among the transfer learning with CNN models we studied in earlier work are AlexNet, ResNet18, GoogLeNet, MobileNetV2, SqueezeNet, ShuffleNet, and EfficientNetb0 [

18]. The SqueezeNet model in particular achieved a classification accuracy of 85.5%; when deep features from SqueezeNet were classified using a DT model, a small performance enhancement was observed, yielding an accuracy of 87.8%. In the current work, an RNN with LSTM architecture was applied, which, trained on our ASD EEG dataset, achieved a classification accuracy of 73.3%. Our intention in presenting these comparative results is not to claim superiority but to contextualize our work within the broader field of ASD classification research.

Overall, the investigation showed that the developed LSTM model exhibited better precision and sensitivity, especially for mild and moderate to severe cases of ASD. These results improve the understanding of how deep learning models can infer temporal patterns in EEG data to enhance ASD classification. Therefore, there is an opportunity for the integration of statistical and artificial intelligence frameworks to help develop solutions for the early detection of distinct EEG patterns before the development of clinical symptoms of ASD, potentially allowing earlier intervention. Furthermore, the correct identification of individuals with varying ASD severity levels supports the development of more efficacious treatment plans and, consequently, greater patient satisfaction.

The investigations should be extended to a larger population sample to validate the findings and enhance the external validity of the conclusions, since the present study indicates that dataset limitations may have affected the performance of the model. The existing single-site, single-cohort design will require subsequent confirmation in multiple populations, laboratories, and acquisition devices to reduce possible cultural, procedural, and device biases. Moreover, the LSTM model should be trained on larger datasets to make it more robust and generalizable to ASD groups, which may include multimodal data to identify typical ASD comorbidities such as anxiety or sleep problems. Regarding clinical use, both the proposed spectro-spatial profile of ASD severity and the artificial intelligence systems (such as integrating EEG into ML/DL methods) may be incorporated into real-world ASD diagnostic and treatment workflows to differentiate mild, moderate, and severe ASD patients from typically developing individuals, thereby enhancing clinical decision-making by practitioners. Further research should also focus on optimizing and regularizing DL models and expanding comparisons with a broader range of competitive ML and DL algorithms.

Statistical, machine learning, and deep learning approaches were employed to classify mild, moderate, and severe ASD and to distinguish ASD from typical control data. This helps our understanding of the correlation between multistage ASD and EEG activity by providing a spectro-spatial profile of ASD severity across various brain regions. The obtained level of accuracy makes this study relevant and provides a dependable tool for the early diagnosis of autism. Overall, these findings highlight the potential of the proposed methods to make a valuable contribution to both autism research and clinical practice in the future.