Genotoxicity of Coffee, Coffee By-Products, and Coffee Bioactive Compounds: Contradictory Evidence from In Vitro Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Genotoxicity Testing Methods

3.2. Studies Showing No Effects

3.2.1. Green Coffee Beans and Unprocessed Coffee Products

3.2.2. Processed Coffee Products

3.2.3. Coffee By-Products

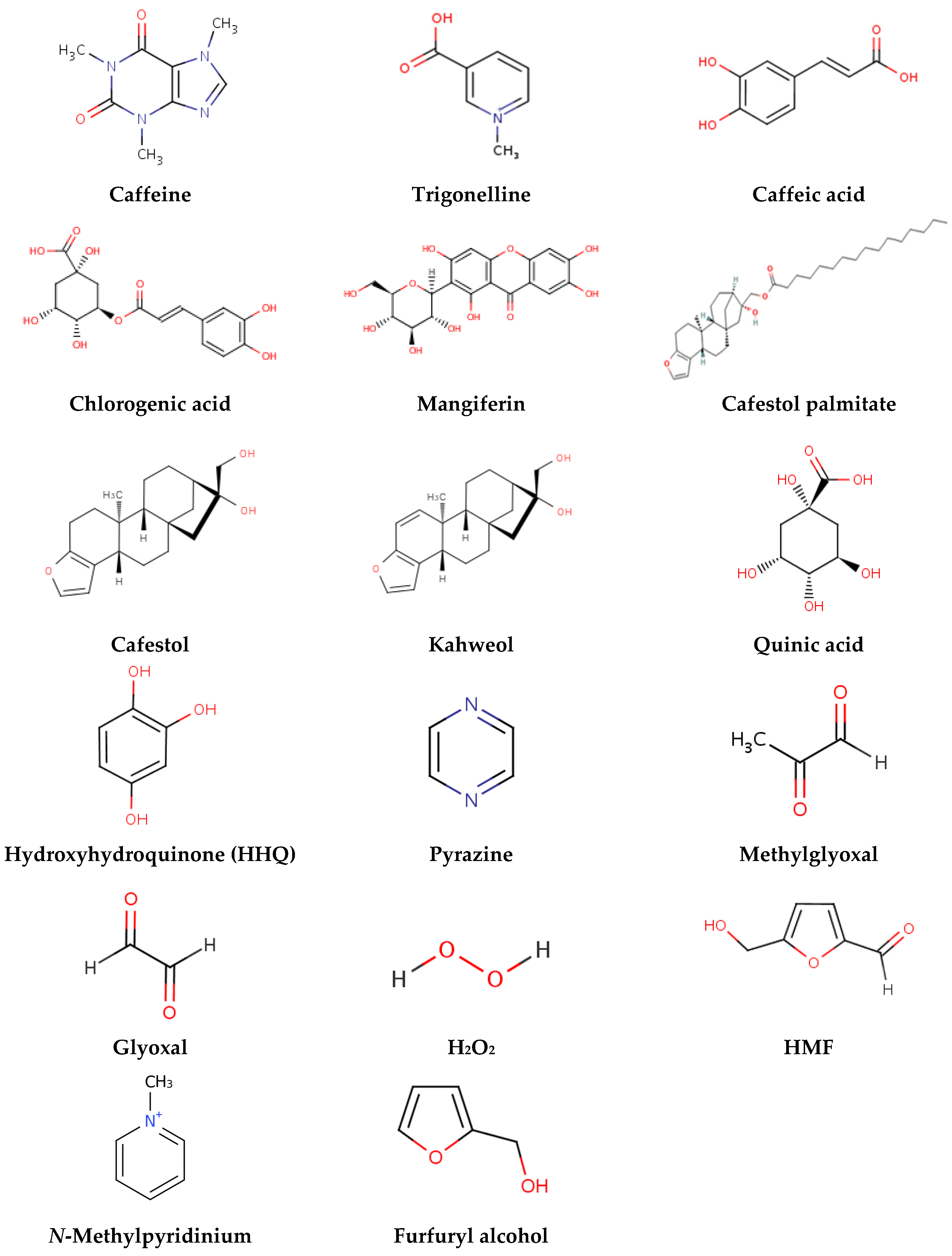

3.2.4. Coffee Bioactive Compounds

3.2.5. Compounds Formed During the Maillard Reaction

3.3. Studies Showing Genotoxic Effects

3.3.1. Roasted Coffee

3.3.2. Instant Coffee

3.3.3. Coffee By-Products

3.3.4. Coffee Bioactive Compounds

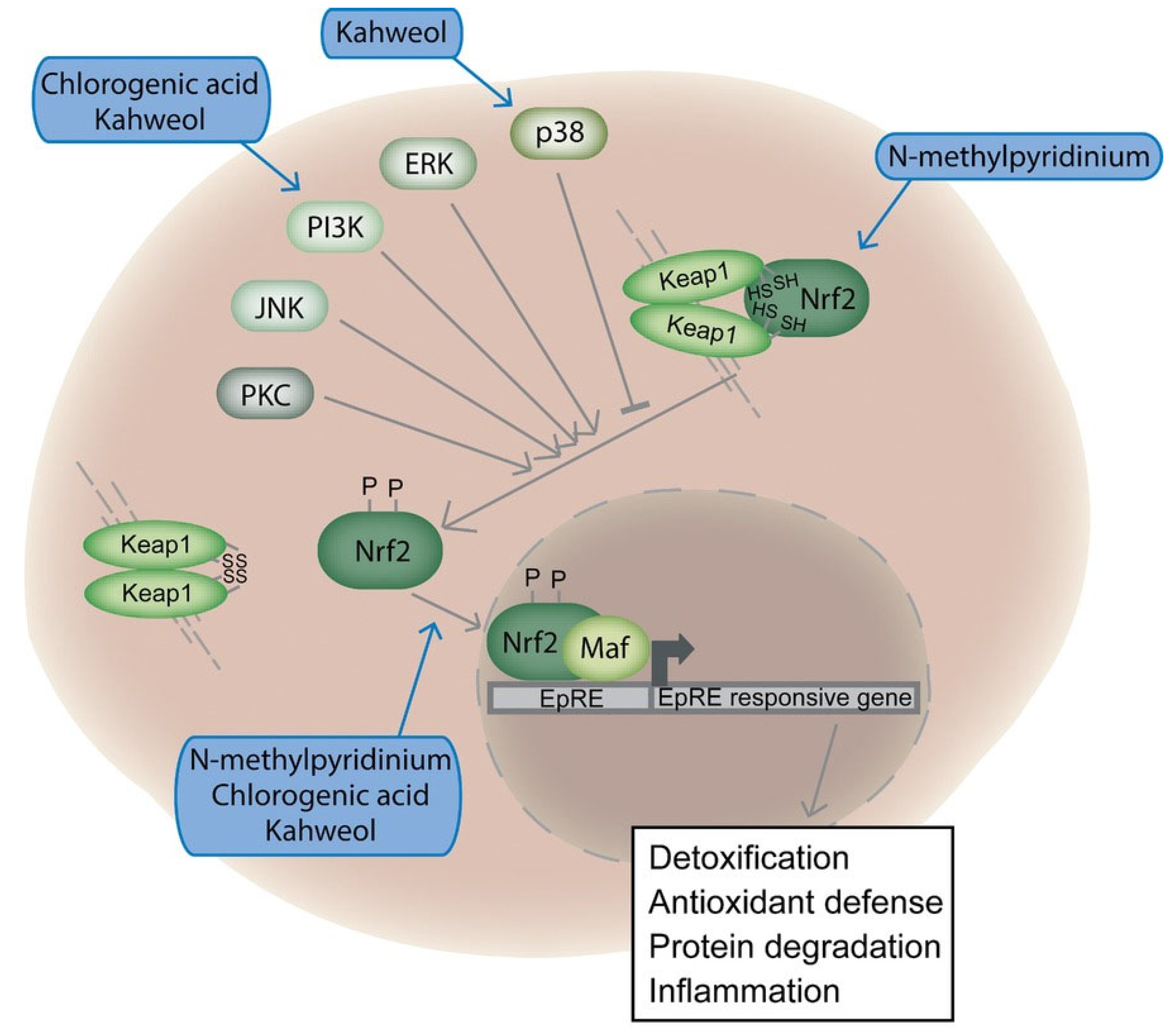

3.4. Studies Showing Protective and Antimutagenic Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NT | Not tested |

| HMF | 5-hydroxymethylfurfural |

| AFB1 | Aflatoxin B1 |

| PhIP | 2-Amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine |

| NDMA | N-nitrosodimethylamine |

| BaP | Benzo[a]pyrene |

| MNNG | N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine |

| MMC | Mitomycin C |

| MMS | Methyl methanesulfonate |

| NPD | 4-Nitro-o-phenylenediamine |

| 2-AF | 2-Aminofluorene |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| Trp-P-2 | 3-Amino-1-methyl-5H-pyrido [4,3-b]indole acetate |

| FFA | Furfuryl alcohol |

| BHMF | 2,5-Bis(hydroxymethyl)furan |

| 5-SMF | 5-Sulfooxymethylfurfural |

| t-BOOH | t-Butylhydroperoxide |

| C + K | Cafestol and kahweol |

| HHQ | Hydroxyhydroquinone |

| SULT1A1 | Sulfotransferase 1A1 |

| CHO | Chinese hamster ovary cells |

| HepG2 | Human hepatocellular carcinoma cells |

| THLE | Human liver epithelial cells |

| L5178Y | Mouse lymphoma cells |

| V79 | Chinese hamster lung fibroblast cells |

| HT29 | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells |

| TK+/− L5178Y cells | Mouse lymphoma thymidine kinase +/− Cells |

| CHL | Chinese hamster lung cells |

| HeLa | Cervical cancer cells |

| HL-60 | Human promyelocytic leukemia cells |

| HT29 | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells |

| Caco-2 | Human intestinal epithelial cells |

| Ara test | L-arabinose forward mutation assay |

| TK | Thymidine kinase locus mutation assay |

| HPRT | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase mutation assay |

| γ-H2AX | Phosphorylated histone H2AX |

| TARDIS | Trapped in agarose DNA immunostaining assay |

| Fpg enzyme | Formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase |

Appendix A

| Test Material | Name of the Test | Experimental System Species, Strain | Concentration | Results | Comments | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With S9 | Without S9 | ||||||

| Coffee cherry | Ames test | Salmonella typhimurium TA98, TA100, TA1535, TA1537 Escherichia coli WP2 uvrA | 31.6–5000 μg/plate | – | – | Strain TA1537 exhibited toxicity at higher concentrations | [32] |

| Green coffee beans | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100 | 5–50 mg/plate | NT | – | [33] | |

| Green coffee beans | Comet test | HT29 (colon) HepG2 (liver) cells | 0.006, 0.8 g/L | NT | – | [35] | |

| Green coffee beans | Sister chromatid exchange | Chinese hamster CHO-K1 | 10 mg/mL | – | – | [36] | |

| Green coffee beans | Ara forward mutation test | S. typhimurium BA1, BA3, BA13, BA9 | 0.5–5 mg/plate | – | – | [34] | |

| Green coffee beans | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA102, TA104 | 0.5–5 mg/plate | – | – | [34] | |

| Green coffee beans | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA98, TA1535, TA92 E. coli WP2 uvrA, WP2uvrA/pKMlO1 | 10–30 mg/plate | – (TA98, TA100) NT (WP2 uvrA/pKM101) | – (TA98, TA100) – (WP2 uvrA/pKM101) | [15] | |

| Green coffee beans | Prophage induction test | E. coli K12, repair-deficient GY5027 (envA uvrB, λ lysogen), repair-competent GY5022 (envA uvr+, λ lysogen), GY4015 (non-lysogenic) | 20–60 mg/plate | NT | – (GY5027) | [15] | |

| Roasted coffee beans | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA98 | 0.005–50 mg/mL | – (TA98) + (TA100) | – (TA98) – (TA100) | [39] | |

| Roasted coffee beans | Cytokinesis-block micronucleus test | HepG2 cells | 0.005–50 mg/mL | NT | – | [39] | |

| Roasted coffee beans | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98, TA100, TA1535 | 100–500 μL/plate | – | – | [40] | |

| Roasted coffee beans | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100 | 10–50 mg/plate | NT | + | [33] | |

| Roasted coffee beans | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA98 | Moderately roasted (US): 7, 21, 35 mg/plate Well roasted (US): 5.8,17,29 mg/plate Well roasted (Japan): 2.3, 4.7, 14 mg/plate Instant coffee (Japan): 1, 3, 6 mg/plate Instant coffee (US): 1, 3, 5 mg/plate Caffeine-free (Japan): 1, 3, 5 mg/plate | – (TA100) – (TA98) | + (TA100) – (TA98) | [38] | |

| Roasted coffee beans | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA98, TA1535, TA92 E. coli WP2 uvrA, WP2uvrA/pKMlO1 | 10–30 mg/plate | – (TA98, TA100) NT (TA92, TA1535, WP2 uvrA, WP2 uvrA/pKM101) | + (TA98, TA100) – (TA92, TA1535) + (WP2 uvrA/pKM101) – (WP2 uvrA) | [15] | |

| Roasted coffee beans | Prophage induction test | E. coli K12, repair-deficient GY5027 (envA uvrB, λ lysogen), repair-competent GY5022 (envA uvr+, λ lysogen), GY4015 (non-lysogenic) | 20–60 mg/plate | NT | + (GY5027) – (GY5022) | [15] | |

| Regular, sugar-roasted ground coffee Regular, sugar-roasted instant coffee | Ara test forward mutation | S. typhimurium BA1, BA3, BA13, BA9 | 0.5–5 mg/plate | – (all strains) | + (all strains) | [34] | |

| Regular, sugar-roasted ground coffee Regular, sugar-roasted instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA102, TA104 | 0.5–5 mg/plate | – (all strains) | + (all strains) | [34] | |

| Roasted coffee beans | Micronucleus test | Blood sample | 0.005–1.0% | NT | + | [37] | |

| Instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100 | 100–800 µg/plate | NT | – | Positive mutagenicity effect after nitrosation | [41] |

| Instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98 TA100 | 250 mg/mL | NT | – | Positive mutagenicity after partial purification on TA98 | [47] |

| Instant coffee | DNA breaking activity | plasmid pBR 322 DNA | 250 mg/mL | NT | – | Positive DNA damage after partial purification | [47] |

| Instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98, YG1024, YG1029 | 0.20, 0.75 gEq/plate | + (all strains) | – (all strains) | [46] | |

| Caffeinated instant coffee | In vitro cytokinesis-block micronucleus test Comet test | L5178Y cells | 125 μg/mL | NT | – | [55] | |

| Instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA1535, TA 1537, TA 1538, TA 98, TA 100 | 5–75 mg/plate | – (TA100) – (TA1535, TA 1537, TA 1538, TA 98) | w+ (TA100) – (TA1535, TA 1537, TA 1538, TA 98) | [54] | |

| Instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA98, TA1535, TA92 E. coli WP2 uvrA, WP2uvrA/pKMlO1 | 10–40 mg/plate | NT | + (WP2 uvrA/pKM101) – (WP2 uvrA) | [15] | |

| Instant coffee | Prophage induction test | E. coli K12, repair-deficient GY5027 (envA uvrB, λ lysogen), repair-competent GY5022 (envA uvr+, λ lysogen), GY4015 (non-lysogenic) | 10–40 mg/plate | NT | + (GY5027) – (GY5022) | [15] | |

| Caffeine-free instant coffee | Prophage induction test | E. coli K12, repair-deficient GY5027 (envA uvrB, λ lysogen), repair-competent GY5022 (envA uvr+, λ lysogen), GY4015 (non-lysogenic) | 10–40 mg/plate | NT | + (GY5027) | [15] | |

| Instant coffee | Ara test | S. typhimurium BA13 (araD531, hisG46, AuvrB, pKM101) | 0.25–5 mg/plate | NT | + | [43] | |

| Instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA102 | 10–40 mg/plate | NT | + (TA100, TA102) | Mutagenic effects above 10 mg/plate Negative result in the presence of catalase | [19] |

| Instant Coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA 98, TA 100, TA 102, TA 104, YG 1024 | 5–40 mg/plate | – (most strains) | + (all strains) | [50] | |

| Instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100 | 5–50 mg/plate | NT | + (TA100) | [33] | |

| Instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA98, TA1535, TA1537, TA1538 | 5–50 mg/plate | – (TA100) – (TA98, TA1535, TA1537, TA1538) | w+ (TA100) – (TA98, TA1535, TA1537, TA1538) | [53] | |

| Caffeinated instant (dark roast, medium roast, dark roast plus chicory) Decaffeinated instant coffees | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA102, TA104 | 10–60 mg/plate | – (TA100) + (TA102, TA104) | + (TA100, TA102, TA104) | [18] | |

| Instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA102 | 10–50 mg/plate | – (TA100, TA102) | + (TA100, TA102) | Weakly positive with glyoxalase I and II and reduced glutathione, both with and without S9 | [48] |

| Caffeinated instant coffee Decaffeinated instant coffee | Sister chromatid exchange | Chinese hamster CHO-K1 | 10 mg/mL | + (blend and instant coffee) – (roasted coffee) – (high roasted) – (Decaffeinated blend and decaffeinated instant) | + (blend and instant coffee) – (roasted coffee) + (high roasted) + (Decaffeinated blend and decaffeinated instant) | [36] | |

| Caffeine-containing and decaffeinated instant coffee | Chromosomal aberration | Human lymphocytes | 2.5–4.3 mg/mL | w+ | + | [42] | |

| Instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100 | 5–30 mg/plate | NT | + | [51] | |

| Instant coffee | Ara test forward mutation | S. typhimurium BA13 | 2.5 mg/plate | – | + | [49] | |

| Instant coffee | Diphtheria toxin resistance as a selective marker | CHL cells | Instant coffee 2–8 mg/mL | NT | + | [44] | |

| Caffeinated and decaffeinated instant coffee, filtered and unfiltered | In vitro cytokinesis-block Micronucleus test Comet test | L5178Y cells | 125 μg/mL | NT | – | [25] | |

| Regular instant coffee Caffeine-free instant coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA98 | 2–10 mg/plate | NT | + (TA100) w+ (TA98) | [45] | |

| Regular instant coffee Caffeine-free instant coffee | phage-inducing activity | E. coli K12 envA uvrB (X), strain GY5027, and X indicator Amp R bacteria, strain GY4015 | 2, 10, 20 mg/plate | NT | + | [45] | |

| Regular roast instant coffee | Ara test Lac I test | E. coli UC838 (wild-type, Catalase-proficient) E. coli UC1218 (wt/pRW144) E. coli UC1221 (catalase defective katG katE) E. coli UC1218 (katG katE/ pRW144) | Ara test 3.75, 7.50, 15 mg/mL lacI mutant analysis: 4, 10, 20 mg/mL | NT | + | [52] | |

| Caffeinated drip dark roasted coffee Decaffeinated drip coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA102, TA104 | 10–60 mg/plate | – (TA100) + (TA102, TA104) | + (TA100, TA102, TA104) | [18] | |

| Ground coffee | Ara test | S. typhimurium BA13 (araD531, hisG46, AuvrB, pKM101) | 0.25–5 mg/plate | NT | + | [43] | |

| Ground coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98, TA100 | 0.25 g | – | – | [56] | |

| Coffee, type of coffee not specified | Comet test | Lung fibroblasts V79- rCYP1A2- rSULT1C1 | 2.5% (w/v) | NT | – | [57] | |

| Metal filtered coffee | Comet test | Human lymphocytes | 25–600 µL/ml | NT | – | Negative result up to 50 µL/ml | [59] |

| Boiled coffee prepared from coarsely ground coffee powder | In vitro cytokinesis-block Micronucleus test Comet test | L5178Y cells | 15, 30, 60 μL/mL | NT | – | [25] | |

| Brewed regular and decaffeinated coffee | p53R test | p53R cells (colorectal cell line expressing TP53 reporter gene) | 453 gr/532 gr water | + | NT | [61] | |

| Freshly-brewed coffee | phage-inducing activity | E. coli K12 envA uvrB (X), strain GY5027, and X indicator Amp R bacteria, strain GY4015 | 2–20 mg/plate | NT | + | [45] | |

| Freshly-brewed coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA98 | 2–20 mg/plate | NT | + (TA100) w+ (TA98) | The mutagenicity was suppressed by addition of sodium sulfite. | [45] |

| Freshly-brewed coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA1535, TA 1537, TA 1538, TA 98, TA 100 | 5–75 mg/plate | – (TA100) – (TA1535, TA 1537, TA 1538, TA 98) | w+ (TA100) – (TA1535, TA 1537, TA 1538, TA 98) | [54] | |

| Regular home brew coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA98, TA1535, TA1537, TA1538 | 5–50 mg/plate | – (TA100) – (TA98, TA1535, TA1537, TA1538) | w+ (TA100) – (TA98, TA1535, TA1537, TA1538) | [53] | |

| Home brew coffee prepared from caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee beans | Chromosomal aberration | Human lymphocytes | 2.5–4.3 mg/mL | w+ | + | [42] | |

| Coffee brew (Arabica filter and Canephora espresso) | Ames test | S. typhimurium His−, TA98 | 2.4–7.2 mg/plate | – | – | [62] | |

| Thick coffee syrup Coffee solid residues Dichloromethane and ethanol extracts of coffee solid residues Normal brewed coffee Overheated brewed coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98, TA100 | Thick coffee syrup: 1–1000 µg/plate Coffee solid residues: 25–12,500 µg/plate Dichloromethane extracts of coffee solid residues: 25–5000 µg/plate Ethanol extracts of coffee solid residues: 25–12,500 µg/plate Normal and overheated brewed coffee: 25–5000 µg/plate | + (TA98, Overheated brewed coffee) – (TA100, all types of coffee preparations) | – (TA98, all types of coffee preparations) – (TA100, all types of coffee preparations) | [60] | |

| Silverskin extract | Alkaline comet test | HepG2 cells | 10–1000 μg/mL | NT | – | [63] | |

| Spent coffee grounds | Comet test | HeLa cells | 111, 333 μg/mL | NT | – | [65] | |

| Spent coffee grounds (Arabica filter and Canephora espresso) | Ames test | S. typhimurium His−, TA98 | 2.4–9.6 mg/plate | – | – | [62] | |

| Leached (LE) and solubilized (SE) extracts from spent coffee grounds | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98, TA100 | 6.25–100% | + (TA98, leached extract) + (TA100, leached extract) + (TA98, solubilized extract) – (TA100, solubilized extract) | + (TA98, leached extract) – (TA100, leached extract) + (TA98, solubilized extract) + (TA100, solubilized extract) | [64] | |

| Leached (LE) and solubilized (SE) extracts from spent coffee grounds | Micronucleus test | HepG2 cell line | 6.25–100% | NT | + (TA98, leached, solubilized extracts) | [64] | |

| HHQ | DNA breaking activity | plasmid pBR 322 DNA | 0.01–10 mM | NT | + | [66] | |

| Trigonelline Caffeic acid Chlorogenic acid Pyrazine | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA1535, TA1537, TA1538, TA98, TA100 | 333.0–10,000.0 µg/plate | – | – (all strains) | [68] | |

| Trigonelline Caffeic acid Chlorogenic acid Pyrazine | Chromosomal aberrations test | TK+/− L5178Y mouse lymphoma cells | Caffeic acid 114–900 µg/mL Chlorogenic acid 500–10,000 µg/mL Pyrazine 2286–10,000 µg/mL | – (Pyrazine and trigonelline) – (Caffeic acid) + (Chlorogenic acid) | – (Pyrazine and trigonelline) + (Caffeic acid) –(Chlorogenic acid) | [68] | |

| Trigonelline and amino acids | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA 98, YG 1024, YG 1029 | Trigonelline 1000 µmol Trigonelline + a single amino acid: 1000 µmol + 1000 µmol Trigonelline+ glucose: 1000 µmol + 100 µmol/L, and a mixture of amino acids | + (TA 98, YG 1024) – (YG 1029) | + (TA 98, YG 1024, YG 1029) | [67] | |

| Mangiferin | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98, TA100, TA1535, TA1537 | 16–5000 µg/plate | – | – | [82] | |

| Mangiferin | In vitro mammalian chromosomal aberration test | E. coli WP2 uvrA | 19.6–625 µg/mL | NT | + | [82] | |

| 1,2-dicarbonyl compounds (glyoxal, methylglyoxal, kethoxal) | Sister chromatid exchange | CHO AUXB1 cells Human peripheral lymphocytes | In CHO cell: Glyoxal 200–1600 µM Methylglyoxal 100–500 µM Kethoxal 50–300 µM H2O2 40–240 µM In lymphocytes: Glyoxal 400–2800 µM Kethoxal 1000–3400 µM | NT | + | [86] | |

| Methylglyoxal Glyoxal | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100 | 1 mg/plate | – | + | [83] | |

| Caffeine H2O2 Methylglyoxal Glyoxal Caffeic acid Chlorogenic acid | Ara test | S. typhimurium BA13 (araD531, hisG46, AuvrB, pKM101) | Methylglyoxal Glyoxal Caffeic acid Chlorogenic acid 14, 28 µmoles/plate H2O2 44, 88 nmol/plate Caffeine 0.3–13 µmoles/plate | NT | – (Caffeine) + (H2O2, Methylglyoxal, glyoxal, caffeic acid, Chlorogenic acid) + (combination of H2O2 and methylglyoxal or glyoxal) | Negative result for H2O2 when catalase was added to the system | [43] |

| H2O2 Methylglyoxal | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100 | H2O2 5, 10 µgr/plate Methylglyoxal 1.5, 3.78 µgr/plate | NT | w+ (H2O2) + (combination of H2O2 and methylglyoxal) | [89] | |

| H2O2 | Ara test Lac I test | E. coli UC838 (wild-type, Catalase-proficient) E. coli UC1218 (wt/pRW144) E. coli UC1221 (catalase defective katG katE) E. coli UC1218 (katG katE/ pRW144) | 1 mM | NT | + | [52] | |

| Coffee aroma | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98, TA100, TA102 | Alyphatic carbonyl compounds: 0.01 nmol–1.7 mmol/plate N-Heterocyclics: 3.5 nmol–1.2 mmol/plate Other compounds: H2O2 29.4 μM–0.15 mM/plate Phenol 0.7 fmol–70 μM/plate Guaiacol 9 nmol–0.9 mmol/plate | + (TA100, YA102, aliphatic dicarbonyl:methylglyoxal, glyoxal, and diacetyl) w+ (TA98, N-heterocyclic Quinoxaline) – (all strains, Furans and sulfur-containing compounds, N-heterocyclics: pyridine, pyrazine, 2,5-dimethylpyrazine, ethylpyrazine, Maleic anhydride, 2-Methylbutanal and 3-methylbutanal) | + (TA100, YA102, aliphatic dicarbonyl:methylglyoxal, glyoxal, and diacetyl) – (TA98, N-heterocyclic Quinoxaline) – (all strains, Furans and sulfur-containing compounds, N-heterocyclics: pyridine, pyrazine, 2,5-dimethylpyrazine, ethylpyrazine, Maleic anhydride, 2-Methylbutanal and 3-methylbutanal) | [90] | |

| Coffee aroma | Chromosomal aberration | Human lymphocytes | 10–48 µg/mL | w+ | + | [42] | |

| Caffeine Sodium bisulfite Methylglyoxal | Diphtheria toxin resistance as a selective marker | CHL cells | Methylglyoxal 25–75 µg/mL Sodium bisulfite 100–320 µg/mL | NT | + (Methylglyoxal) – (Caffeine, Sodium Bisulfite) | [44] | |

| Caffeine | Comet test | Mice embryo cells | 2 mM, 5 mM | NT | – | Caffeine affected DNA repair processes. | [88] |

| Caffeine | Chromosomal aberration | Human lymphocytes | 5–100 µg/ml | – | – | [42] | |

| Caffeic acid Chlorogenic acid | Comet Test | HL-60 and Jurkat cells | 1–100 μM | NT | – | [71] | |

| Caffeic acid Chlorogenic acid | Micronucleus test | HL-60 and Jurkat cells | 1–100 μM | NT | – | [71] | |

| Cafestol palmitate a mixture of cafestol and kahweol (C + K) | Micronucleus tests | HepG2 cells | Cafestol palmitate 27.6–415 µg/mL C + K 3.9–31.3 µg/mL | NT | – | [91] | |

| Chlorogenic acid Catechol Caffeic acid Caffeine | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100 | 100–800 µg/plate | NT | – | Positive mutagenicity effect after nitrosation, except caffeine | [41] |

| Chlorogenic acid | Comet test | HT29 HepG2 cells | 1–500 µM | NT | – | [35] | |

| Chlorogenic acid | isolated λ DNA systems | – | 89 µg/mL | NT | + | [75] | |

| Chlorogenic acid | isolated plasmid DNA (pBR322) | – | 35 µg/mL | NT | + | The presence of NO-releasing compounds increased DNA breaks | [73] |

| Chlorogenic acid Caffeic acid | DNA strand break test | Supercoiled ΦX174 RF I DNA | 100 µM | NT | – | Positive result in the presence of Cu2+ | [70] |

| Chlorogenic acid | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98 | 166, 1660 nmol/plate | – | – | [80] | |

| Chlorogenic acid | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98 | 1–9 mg/mL | – | – | [79] | |

| Chlorogenic acid Caffeic acid Quinic acid | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98, TA100 | Chlorogenic acid 19, 28 mg/plate Caffeic acid 6, 10 mg/plate D(-)quinic acid 162, 203 mg/plate | – | – | Positive result for chlorogenic and caffeic acid in the presence of Mn2+ | [69] |

| Chlorogenic acid Caffeic acid Quinic acid | Gene conversion test | Saccharomyces cerevisiae D7 | Chlorogenic acid 20, 49, 80 mg/mL Caffeic acid 20, 30, 40 mg/mL D(-)quinic acid 60, 120, 240 mg/mL | – | + | Convertogenic activity enhanced by Mn2+, Cu2+ had minimal effects | [69] |

| Chlorogenic acid Caffeic acid Quinic acid | Chromosome aberration test | CHO cells | 0.01–0.4 mg/mL | – | + | Chromosome aberration test enhanced by Mn2+, Cu2+ had minimal effects | [69] |

| Chlorogenic acid | Gene conversion test | S. cerevisiae D7 | 1 mg/mL | NT | – | Induced mitotic conversion only at alkaline pH levels | [76] |

| Chlorogenic acid | Mutagenesis tests with mammalian cells | Chinese hamster V79-6 cells | 500 nmol/mL | NT | – | [81] | |

| Chlorogenic acid | Comet test | Chinese hamster V79 cells | 0.07 mg/mL | NT | + | [77] | |

| Chlorogenic acid | Chromosomal aberration test | CHO cells | 125–250 µg/mL | – | + | [78] | |

| Chlorogenic acid | Comet test | Human K562 leukemia cells | 0.5, 1, 5 mM | NT | + | [20] | |

| Chlorogenic acid | Immunofluorescence γ-H2AX Focus Test | Human K562 leukemia cells Chinese hamster ovary AA8 cell line | 0.5, 1, 5 mM | NT | + | [20] | |

| Chlorogenic acid | TARDIS test | Human K562 leukemia cells | 0.5, 1, 5 mM | NT | + | [20] | |

| Dimethylpyrazine HMF | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA98 | Dimethylpyrazine: 1–150 µg/plate HMF: 1–50 µL/plate | – | – | [97] | |

| HMF | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA98, TA100, TA1535, TA1537 E.coli WP2uvrapKM101 | 5–5000 µg/plate | – | – (all strains) | [94] | |

| HMF | Micronucleus test | HepG2 cells | 5.35–36.6 mM | NT | – | [94] | |

| HMF | Comet test | HepG2 cells | 5.35–36.6 mM | NT | + | [94] | |

| HMF | Comet test | Human cell lines (with SULT1A1-activity): Caco-2 HEK293 L5178Y cells (without SULT1A1-activity) V79 cells (without SULT1A1-activity) Chinese hamster V79-hP-PST (express high levels of human SULT1A1) | 25–100 mM | NT | + (all cell lines) | [95] | |

| HMF | Umu test | S. typhimurium TA1535/pSK1002 | 8–20 mM | + | + | [93] | |

| HMF | Alkaline comet test | V79 cells Caco-2 cells Primary rat hepatocytes Primary human colon cells | V79 and Caco-2 cells 8–20 mM Primary rat hepatocytes 40–100 mM Primary human colon cells 80, 120 mM | NT | – (V79 cells, Caco-2 cells, Primary human colon cells, Rat hepatocytes) w+ (V79 cells) | Induced weak genotoxicity at high concentration (120 mM) in V79 cells | [93] |

| HMF | HPRT test | V79 cells | 80–140 mM | NT | w+ | [93] | |

| HMF FFA BHMF 5-SMF 3-hydroxymethylfuran | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA100-hSULT1A1 | 10–10,000 nmol/plate | NT | – (all strains, HMF) – (TA100, HMF, BHMF, FFA, 5-methyl-FFA) w+ (all strains, 3-hydroxymethylfuran) + (TA100, 5-SMF, Furfuryl acetate) + (TA100-hSULT1A1, HMF, BHMF, FFA, 5-methyl-FFA) | [96] | |

| HMF Acetol Glyoxal Methylglyoxal Diacetyl | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100 | – | NT | + (Methylglyoxal) – (HMF, acetol, glyoxal, diacetyl) | [87] | |

| Diacetyl Methyl Glyoxal HMF Acetol Furfural | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100 | Diacetyl methyl glyoxal glyoxal: 1.05 µmol/plate HMF acetol furfural: 4.44 µmol/plate | NT | + | [84] | |

| Furfural HMF Glyoxal Methylglyoxal | Chromosome aberration test | V79 cells | Furfural: 500–2000 µg/mL HMF: 1000–2000 µg/mL Glyoxal: 100–400 µg/mL Methylglyoxal: 10–100 µg/ml | NT | + | [85] | |

| Maillard reaction products isolated from brewed coffee | PM2 bacteriophage DNA | – | 0.1–0.001% w/v | NT | + | [98] | |

| Water-insoluble fraction of coffee | Ames test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA98 | 10–50 mg/mL | – | – | Strong antigenotoxicity against AFB1 MNNG BaP | [16] |

| Caffeinated instant coffee Decaffeinated instant coffee Boiled coffee | Tk locus mutation test | L5178Y cells | Caffeinated and decaffeinated instant coffee 125 µg/mL Boiled coffee 15, 30, 60 µg/mL MNNG 0.75 µg/ml | NT | – | Strong antigenotoxicity of caffeinated and decaffeinated instant coffee and boiled coffee against MNNG | [25] |

| Caffeinated instant coffee Decaffeinated instant coffee Boiled coffee | Comet test | L5178Y cells | Caffeinated and decaffeinated instant coffee 125 µg/mL MNNG 0.5 µg/ml | NT | – | Strong antigenotoxicity of caffeinated and decaffeinated instant coffee against MNNG | [25] |

| Caffeinated instant coffee Decaffeinated instant coffee Boiled coffee | Micronucleus formation | L5178Y cells | Caffeinated and decaffeinated instant coffee 125 µg/mL MNNG 0.75 µg/mL | NT | – | Strong antigenotoxicity of caffeinated and decaffeinated instant coffee against MNNG | [25] |

| Caffeinated instant coffee | In vitro Cytokinesis-block micronucleus test Comet Test | L5178Y cells | (1) Micronucleus Test: Coffee 125 µg/mL MNNG 0.75 and 1.5 µg/mL MMS 30 µg/mL MMC 40 and 80 ng/mL Gamma radiation 0.5, 1 and 2 Gy (2) Comet test: Coffee 125 µg/mL MMS 30 and 40 µg/mL | NT | – | Strong antigenotoxicity in a dose dependent manner against various genotoxic agents: MNNG, MMC, Methyl MMS, gamma radiation | [55] |

| Instant coffee | Ames plate test | S. typhimurium TA100, TA102 | Instant coffee 2.5–20 mg/plate t-BOOH 1 µmole | NT | – | Strong antigenotoxicity against t-BOOH | [19] |

| Coffee silverskin | Alkaline comet test | HepG2 cells incubated with Fpg enzymes | Coffee silverskin 1, 10, 100 μg/mL BaP 100 μM | NT | – | Strong antigenotoxicity against BaP-induced DNA damage | [63] |

| Spent coffee grounds (Arabica filter and Canephora espresso) | Comet test | HeLa cells | Spent coffee grounds 111, 333 μg/mL H2O2 500 µM | NT | – | Strong antigenotoxicity against H2O2 | [65] |

| Arabica filter: Spent coffee Coffee brew Canephora espresso: Spent coffee Coffee brew | Ames Test | S. typhimurium TA98 | Spent coffee 2.4, 4.8, 9.6 mg/plate Coffee brew 2.4, 4.8, 7.2 mg/plate NPD 20 µg/plate 2-AF 10 µg/plate | – | – | Significant antimutagenic with and without S9 against NPD and 2-AF | [62] |

| Cafestol palmitate C + K | Micronucleus tests | HepG2 cells | Cafestol palmitate 0.55–55 µg/mL C + K 0.31–3.8 µg/mL PhIP 300 µM NDMA 100 mM | NT | – | Inhibited MN induced by PhIP and NDMA | [91] |

| Cafestol and kahweol | DNA adduct formation | THLE cells | C + K 2–8 µg/mL 10 nM [3H]-AFB1 | NT | NT | Reduction in AFB1- DNA adducts Formation | [92] |

| Green coffee beans Chlorogenic Acid | Comet test | HT29 HepG2 cells | Chlorogenic acid 1–500 µM Green coffee beans 0.006, 0.8 g/L H2O2 75µM | NT | – | Strong antigenotoxicity reduction in H2O2-induced DNA damage | [35] |

| Coffee (metal filtered and paper filtered coffee) | Comet test | Human lymphocytes | Coffee 25, 50, 100 µL/mL H2O2 50 µM Trp-P-2 200 µM | NT | – | Strong antigenotoxicity against H2O2 and Trp-P-2 | [59] |

| Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee | DNA adducts | Rat primary hepatocytes Human primary hepatocytes THLE cells | Coffee 50–1200 µg/mL 10 nM [3H]-AFB1 | NT | NT | Reduction in AFB1- DNA adduct formation | [58] |

| Coffee, type of coffee not specified | Comet test | V79 cells- rCYP1A2- rSULT1C1 | Coffee 2.5% PhIP 100 µM | NT | – | Protective effect against PhIP | [57] |

References

- Daglia, M.; Papetti, A.; Gregotti, C.; Bertè, F.; Gazzani, G. In vitro antioxidant and ex vivo protective activities of green and roasted coffee. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adong, A.; Kornher, L.; Chichaibelu, B.B.; Arslan, A. The Hidden Costs of Coffee Production in the Eastern African Value Chains. Background Paper for The State of Food and Agriculture 2024; Agric. Dev. Econ. Work. Pap. 24-06; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottstein, V.; Bernhardt, M.; Dilger, E.; Keller, J.; Breitling-Utzmann, C.M.; Schwarz, S.; Kuballa, T.; Lachenmeier, D.W.; Bunzel, M. Coffee Silver Skin: Chemical Characterization with Special Consideration of Dietary Fiber and Heat-Induced Contaminants. Foods 2021, 10, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service. Coffee: World Markets and Trade; Foreign Agric. Serv./USDA Glob. Mark. Anal; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1–9.

- Chałupnik, A.; Borkowska, A.; Sobstyl, A.; Chilimoniuk, Z.; Dobosz, M.; Sobolewska, P.; Piecewicz-Szczęsna, H. The impact of coffee on human health. J. Educ. Health Sport 2019, 9, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Gómez, J.A.; Florez-Pardo, L.M.; Leguizamón-Vargas, Y.C. Valorization of coffee by-products in the industry, a vision towards circular economy. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, A.; das Neves, J.; Sarmento, B.; Amaral, M.H.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Coffee silverskin: A possible valuable cosmetic ingredient. Pharm. Biol. 2015, 53, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, F.; Gaspar, C.; Palmeira-de-Oliveira, A.; Sarmento, B.; Helena Amaral, M.; P P Oliveira, M.B. Application of Coffee Silverskin in cosmetic formulations: Physical/antioxidant stability studies and cytotoxicity effects. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2016, 42, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingel, T.; Kremer, J.I.; Gottstein, V.; Rajcic de Rezende, T.; Schwarz, S.; Lachenmeier, D.W. A Review of Coffee By-Products Including Leaf, Flower, Cherry, Husk, Silver Skin, and Spent Grounds as Novel Foods within the European Union. Foods 2020, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Committee. Scientific opinion on genotoxicity testing strategies applicable to food and feed safety assessment. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens; Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; de Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Guidance on the scientific requirements for an application for authorisation of a novel food in the context of Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Test no. 471: Bacterial reverse mutation test. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECHA. Guidance for the Implementation of REACH. In Guidance on Information Requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment; Chapter R.7.a: Endpoint Specific Guidance. Section R.7.7 Mutagenicity and Carcinogenicity; European Chemicals Agency: Helsinki, Finland, 2008; p. 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajurao, E.C.; Revale, I.F.H. Antigenotoxicity screening of coffee (Coffea arabica Linn) and Cacao (Theobroma cacao Linn.). APJEAS 2016, 3, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, A.; Nagao, M.; Suwa, Y.; Wakabayashi, K.; Sugimura, T. Roasting coffee beans produces compounds that induce prophage λ in E. coli and are mutagenic in E. coli and S. typhimurium. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. 1983, 116, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molund, V.P. Inhibition of Carcinogen Induced Biological Responses with a Coffee Water-Insoluble Fraction and a Model System Melanoidin; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 1984; pp. 1–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.P.L.; Ferreira, E.B.; Barbisan, L.F.; Brigagao, M. Organically produced coffee exerts protective effects against the micronuclei induction by mutagens in mouse gut and bone marrow. Food Res. Int. 2014, 61, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, B.S.; Troxclair, A.M.; McMillin, D.J.; Henry, C.B. Comparative mutagenicity of nine brands of coffee to Salmonella typhimurium TA100, TA102, and TA104. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1988, 11, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, R.H.; Turesky, R.J.; Müller, O.; Markovic, J.; Leong-Morgenthaler, P.M. The inhibitory effects of coffee on radical-mediated oxidation and mutagenicity. Mutat. Res. 1994, 308, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Morón, E.; Calderón-Montaño, J.M.; Orta, M.L.; Pastor, N.; Pérez-Guerrero, C.; Austin, C.; Mateos, S.; López-Lázaro, M. The coffee constituent chlorogenic acid induces cellular DNA damage and formation of topoisomerase I- and II-DNA complexes in cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 7384–7391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, K.; Gürtler, R.; Berg, K.; Heinemeyer, G.; Lampen, A.; Appel, K.E. Toxicology and risk assessment of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural in food. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binello, A.; Cravotto, G.; Menzio, J.; Tagliapietra, S. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in coffee samples: Enquiry into processes and analytical methods. Food Chem. 2021, 344, 128631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gałan, A.; Jesionek, W.; Majer-Dziedzic, B.; Lubicki, Ł.; Choma, I.M. Investigation of different extraction methods on the content and biological activity of the main components in Coffea arabica L. extracts. JPC-J. Planar Chromatogr. Mod. TLC 2015, 28, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrah, R.P.; Rahimi, A.; Yarahmadi, M.; Talebi-Ghane, E. Health Risk Assessment of Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Coffee-based Products: A Meta-analysis Study and Systematic Review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.K.; Stopper, H. Anti-genotoxicity of coffee against N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine in mouse lymphoma cells. Mutat. Res. 2004, 561, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.K.; Singh, S.P. Anti-genotoxicity and glutathione S-transferase activity in mice pretreated with caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Drinking Coffee, Mate, and Very Hot Beverages. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): Lyon, France, 2016; Volume 116, pp. 1–499. [Google Scholar]

- Behne, S.; Franke, H.; Schwarz, S.; Lachenmeier, D.W. Risk Assessment of Chlorogenic and Isochlorogenic Acids in Coffee By-Products. Molecules 2023, 28, 5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Test no. 487: In vitro mammalian cell micronucleus test. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4; OECD: Paris, France, 2023; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Scientific Committee; More, S.; Bampidis, V.; Benford, D.; Bragard, C.; Halldorsson, T.; Hernández-Jerez, A.; Bennekou, S.H.; Koutsoumanis, K.; Lambré, C.; et al. Guidance on risk assessment of nanomaterials to be applied in the food and feed chain: Human and animal health. EFSA J. 2021, 19, 6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.; Srivastava, R. Bacterial worth in genotoxicity assessment studies. J. Microbiol. Methods 2023, 215, 106860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heimbach, J.T.; Marone, P.A.; Hunter, J.M.; Nemzer, B.V.; Stanley, S.M.; Kennepohl, E. Safety studies on products from whole coffee fruit. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 2517–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, S.; Friederich, U.; Schlatter, C.; Würgler, F.E. The influence of roasting procedure on the formation of mutagenic compounds in coffee. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1985, 23, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorado, G.; Barbancho, M.; Pueyo, C. Coffee is highly mutagenic in the L-arabinose resistance test in Salmonella typhimurium. Environ. Mutagen. 1987, 9, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glei, M.; Kirmse, A.; Habermann, N.; Persin, C.; Pool-Zobel, B.L. Bread enriched with green coffee extract has chemoprotective and antigenotoxic activities in human cells. Nutr. Cancer 2006, 56, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Maria, A.; López, A.; Díaz, M.M.; Ortíz, A.I.; Caballo, C. Sister chromatid exchange induced by several types of coffees in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Teratog. Carcinog. Mutagen. 2001, 21, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, S.E.D.A.; Alkhalifah, D.H. In-vitro comparative studies: Three techniques for comparing the mutagenicity, genotoxicity of irradiated and processed food. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2013, 7, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Nagao, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamanaka, H.; Sugimura, T. Mutagens in coffee and tea. Mutat. Res. 1979, 68, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, C.Q.; Da Fernandes, A.S.; Teixeira, G.F.; França, R.J.; Da Marques, M.R.C.; Felzenszwalb, I.; Falcão, D.Q.; Ferraz, E.R.A. Risk assessment of coffees of different qualities and degrees of roasting. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.-S.; Chen, P.-W.; Wang, J.-Y.; Kuo, T.-C. Assessment of Cellular Mutagenicity of Americano Coffees from Popular Coffee Chains. J. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, M.P.; Laires, A.; Gaspar, J.; Oliveira, J.S.; Rueff, J. Genotoxicity of instant coffee and of some phenolic compounds present in coffee upon nitrosation. Teratog. Carcinog. Mutagen. 2000, 20, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aeschbacher, H.U.; Ruch, E.; Meier, H.; Würzner, H.P.; Munoz-Box, R. Instant and brewed coffees in the in vitro human lymphocyte mutagenicity test. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1985, 23, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariza, R.R.; Dorado, G.; Barbancho, M.; Pueyo, C. Study of the causes of direct-acting mutagenicity in coffee and tea using the Ara test in Salmonella typhimurium. Mutat. Res. 1988, 201, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakasato, F.; Nakayasu, M.; Fujita, Y.; Nagao, M.; Terada, M.; Sugimura, T. Mutagenicity of instant coffee on cultured Chinese hamster lung cells. Mutat. Res. 1984, 141, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwa, Y.; Nagao, M.; Kosugi, A.; Sugimura, T. Sulfite suppresses the mutagenic property of coffee. Mutat. Res. 1982, 102, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.A.; Knize, M.G.; Jägerstad, M.; Felton, J.S. Characterization of mutagenic activity in instant hot beverage powders. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1995, 25, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Hiramoto, K.; Kikugawa, K. Possible occurrence of new mutagens with the DNA breaking activity in coffee. Mutat. Res. 1994, 306, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friederich, U.; Hann, D.; Albertini, S.; Schlatter, C.; Würgler, F.E. Mutagenicity studies on coffee. The influence of different factors on the mutagenic activity in the Salmonella/mammalian microsome assay. Mutat. Res. 1985, 156, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariza, R.R.; Pueyo, C. The involvement of reactive oxygen species in the direct-acting mutagenicity of wine. Mutat. Res. 1991, 251, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, M.P.; Laires, A.; Gaspar, J.; Leão, D.; Oliveira, J.S.; Rueff, J. Genotoxicity of instant coffee: Possible involvement of phenolic compounds. Mutat. Res. 1999, 442, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, Y.; Wakabayashi, K.; Nagao, M.; Sugimura, T. Characteristics of major mutagenicity of instant coffee. Mutat. Res. 1985, 142, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Laguna, J.; Pueyo, C. Hydrogen peroxide and coffee induce G:C→T:A transversions in the lacI gene of catalase-defective Escherichia coli. Mutagenesis 1999, 14, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aeschbacher, H.U.; Würzner, H.P. An evaluation of instant and regular coffee in the Ames mutagenicity test. Toxicol. Lett. 1980, 5, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aeschbacher, H.U.; Chappuis, C.; Würzner, H.P. Mutagenicity testing of coffee: A study of problems encountered with the Ames Salmonella test system. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 1980, 18, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, S.K.; Vukicevic, V.; Stopper, H. Coffee-mediated protective effects against directly acting genotoxins and gamma-radiation in mouse lymphoma cells. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2004, 20, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.M.S.; Rainer, B.; Wagner, I.; Krauter, V.; Janalíková, M.; Vicente, A.A.; Vieira, J.M. Valorization of Cork Stoppers, Coffee-Grounds and Walnut Shells in the Development and Characterization of Pectin-Based Composite Films: Physical, Barrier, Antioxidant, Genotoxic, and Biodegradation Properties. Polymers 2024, 16, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edenharder, R.; Sager, J.W.; Glatt, H.; Muckel, E.; Platt, K.L. Protection by beverages, fruits, vegetables, herbs, and flavonoids against genotoxicity of 2-acetylaminofluorene and 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) in metabolically competent V79 cells. Mutat. Res. 2002, 521, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavin, C.; Marin-Kuan, M.; Langouët, S.; Bezençon, C.; Guignard, G.; Verguet, C.; Piguet, D.; Holzhäuser, D.; Cornaz, R.; Schilter, B. Induction of Nrf2-mediated cellular defenses and alteration of phase I activities as mechanisms of chemoprotective effects of coffee in the liver. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bichler, J.; Cavin, C.; Simic, T.; Chakraborty, A.; Ferk, F.; Hoelzl, C.; Schulte-Hermann, R.; Kundi, M.; Haidinger, G.; Angelis, K.; et al. Coffee consumption protects human lymphocytes against oxidative and 3-amino-1-methyl-5H-pyrido[4,3-b]indole acetate (Trp-P-2) induced DNA-damage: Results of an experimental study with human volunteers. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, C.A.; Shibamoto, T. Ames mutagenicity tests of overheated brewed coffee. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1984, 22, 971–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.Z.; Gilbert, S.F.; Patel, K.; Ghosh, S.; Bhunia, A.K.; Kern, S.E. Biological clues to potent DNA-damaging activities in food and flavoring. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 55, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monente, C.; Bravo, J.; Vitas, A.I.; Arbillaga, L.; de Peña, M.P.; Cid, C. Coffee and spent coffee extracts protect against cell mutagens and inhibit growth of food-borne pathogen microorganisms. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 12, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriondo-DeHond, A.; Haza, A.I.; Ávalos, A.; Del Castillo, M.D.; Morales, P. Validation of coffee silverskin extract as a food ingredient by the analysis of cytotoxicity and genotoxicity. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.S.; Mello, F.V.C.; Thode Filho, S.; Carpes, R.M.; Honório, J.G.; Marques, M.R.C.; Felzenszwalb, I.; Ferraz, E.R.A. Impacts of discarded coffee waste on human and environmental health. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 141, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, J.; Arbillaga, L.; de Peña, M.P.; Cid, C. Antioxidant and genoprotective effects of spent coffee extracts in human cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 60, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiramoto, K.; Li, X.; Makimoto, M.; Kato, T.; Kikugawa, K. Identification of hydroxyhydroquinone in coffee as a generator of reactive oxygen species that break DNA single strands. Mutat. Res. 1998, 419, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Skog, K.; Jägerstad, M. Trigonelline, a naturally occurring constituent of green coffee beans behind the mutagenic activity of roasted coffee? Mutat. Res. 1997, 391, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, V.A.; Cameron, T.P.; Hughes, T.J.; Kirby, P.E.; Dunkel, V.C. Mutagenic activity of some coffee flavor ingredients. Mutat. Res. 1988, 204, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stich, H.F.; Rosin, M.P.; Wu, C.H.; Powrie, W.D. A comparative genotoxicity study of chlorogenic acid (3-O-caffeoylquinic acid). Mutat. Res. 1981, 90, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Trush, M.A. Reactive oxygen-dependent DNA damage resulting from the oxidation of phenolic compounds by a copper-redox cycle mechanism. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 1895s–1898s. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hernandes, L.C.; Machado, A.R.T.; Tuttis, K.; Ribeiro, D.L.; Aissa, A.F.; Dévoz, P.P.; Antunes, L.M.G. Caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid cytotoxicity, genotoxicity and impact on global DNA methylation in human leukemic cell lines. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2020, 43, 20190347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stich, H.F.; Stich, W.; Rosin, M.P.; Powrie, W.D. Mutagenic activity of pyrazine derivatives: A comparative study with Salmonella typhimurium, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Chinese hamster ovary cells. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 1980, 18, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshie, Y.; Ohshima, H. Nitric oxide synergistically enhances DNA strand breakage induced by polyhydroxyaromatic compounds, but inhibits that induced by the Fenton reaction. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1997, 342, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stich, H.F.; Rosin, M.P.; Wu, C.H.; Powrie, W.D. The action of transition metals on the genotoxicity of simple phenols, phenolic acids and cinnamic acids. Cancer Lett. 1981, 14, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Shirahata, S.; Mirakami, H.; Nishiyama, K.; Shinohara, K.; Omura, H. DNA breakage by phenyl compounds. Agric. Biol. Chem 1985, 49, 1423–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, M.P. The influence of pH on the convertogenic activity of plant phenolics. Mutat. Res. 1984, 135, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, E.D.D.M.; da Silva, J.; Carvalho, P.D.S.; Grivicich, I.; Picada, J.N.; Salgado Junior, I.B.; Vasques, G.J.; Pereira, M.A.D.S.; Reginatto, F.H.; Ferraz, A.D.B.F. In vivo and in vitro toxicological evaluations of aqueous extract from Cecropia pachystachya leaves. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2020, 83, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, F.W.; San, R.H.; Stich, H.F. An intestinal cell-mediated chromosome aberration test for the detection of genotoxic agents. Mutat. Res. 1983, 111, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San, R.H.; Chan, R.I. Inhibitory effect of phenolic compounds on aflatoxin B1 metabolism and induced mutagenesis. Mutat. Res. 1987, 177, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacGregor, J.T.; Jurd, L. Mutagenicity of plant flavonoids: Structural requirements for mutagenic activity in Salmonella typhimurium. Mutat. Res. 1978, 54, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, A.W.; Huang, M.T.; Chang, R.L.; Newmark, H.L.; Lehr, R.E.; Yagi, H.; Sayer, J.M.; Jerina, D.M.; Conney, A.H. Inhibition of the mutagenicity of bay-region diol epoxides of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by naturally occurring plant phenols: Exceptional activity of ellagic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 5513–5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddeman, R.A.; Glávits, R.; Endres, J.R.; Clewell, A.E.; Hirka, G.; Vértesi, A.; Béres, E.; Szakonyiné, I.P. A Toxicological Evaluation of Mango Leaf Extract (Mangifera indica) Containing 60% Mangiferin. J. Toxicol. 2019, 2019, 4763015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, M.; Fujita, Y.; Wakabayashi, K.; Nukaya, H.; Kosuge, T.; Sugimura, T. Mutagens in coffee and other beverages. Environ. Health Perspect. 1986, 67, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Hayase, F.; Kato, H. Desmutagenic effect of α-dicarbonyl and α-hydroxycarbonyl compounds against mutagenic heterocyclic amines. Mutat. Res. 1987, 177, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Miyakawa, Y.; Kato, K. Chromosome aberrations induced by pyrolysates of carbohydrates in Chinese hamster V79 cells. Mutat. Res. 1989, 227, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.D.; Taylor, R.T.; Christensen, M.L.; Strout, C.L.; Hanna, M.L. Cytogenetic response to coffee in Chinese hamster ovary AUXB1 cells and human peripheral lymphocytes. Mutagenesis 1989, 4, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, H.; Kumeno, K.; Yamaizumi, Z.; Nishimura, S.; Nagao, M.; Fujita, Y.; Sugimura, T.; Nukaya, H.; Kosuge, T. Mutagenicity of methylglyoxal in coffee. Gan 1982, 73, 681–683. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, W.U.; Bauch, T.; Wojcik, A.; Böcker, W.; Streffer, C. Comet assay studies indicate that caffeine-mediated increase in radiation risk of embryos is due to inhibition of DNA repair. Mutagenesis 1996, 11, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, Y.; Wakabayashi, K.; Nagao, M.; Sugimura, T. Implication of hydrogen peroxide in the mutagenicity of coffee. Mutat. Res. 1985, 144, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aeschbacher, H.U.; Wolleb, U.; Löliger, J.; Spadone, J.C.; Liardon, R. Contribution of coffee aroma constituents to the mutagenicity of coffee. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1989, 27, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majer, B.J.; Hofer, E.; Cavin, C.; Lhoste, E.; Uhl, M.; Glatt, H.R.; Meinl, W.; Knasmüller, S. Coffee diterpenes prevent the genotoxic effects of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) and N-nitrosodimethylamine in a human derived liver cell line (HepG2). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2005, 43, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavin, C.; Mace, K.; Offord, E.A.; Schilter, B. Protective effects of coffee diterpenes against aflatoxin B1-induced genotoxicity: Mechanisms in rat and human cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2001, 39, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzowski, C.; Glaab, V.; Samimi, E.; Schlatter, J.; Eisenbrand, G. 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural: Assessment of mutagenicity, DNA-damaging potential and reactivity towards cellular glutathione. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2000, 38, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severin, I.; Dumont, C.; Jondeau-Cabaton, A.; Graillot, V. Genotoxic activities of the food contaminant 5-hydroxymethylfurfural using different in vitro bioassays. Toxicol. Lett. 2010, 192, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durling, L.J.K.; Busk, L.; Hellman, B.E. Evaluation of the DNA damaging effect of the heat-induced food toxicant 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) in various cell lines with different activities of sulfotransferases. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatt, H.; Schneider, H.; Murkovic, M.; Monien, B.H.; Meinl, W. Hydroxymethyl-substituted furans: Mutagenicity in Salmonella typhimurium strains engineered for expression of various human and rodent sulphotransferases. Mutagenesis 2012, 27, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeschbacher, H.U.; Chappus, C.; Manganel, M.; Aeschbach, R. Investigation of Maillard products in bacterial mutagenicity test systems. Prog. Food Nutr. Sci. 1981, 5, 279–294. [Google Scholar]

- Wijewickreme, A.N.; Kitts, D.D. Modulation of metal-induced genotoxicity by Maillard reaction products isolated from coffee. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1998, 36, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Shlyankevich, M.; Jeong, H.-K.; Douglas, J.S.; Surh, Y.J. Bioactivation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde to an electrophilic and mutagenic allylic sulphuric acid ester. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 209, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surh, Y.J.; Liem, A.; Miller, J.A.; Tannenbaum, S.R. 5-Sulfooxymethylfurfural as a possible ultimate mutagenic and carcinogenic metabolite of the Maillard reaction product, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Carcinogenesis 1994, 15, 2375–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surh, Y.J.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Activation of the Maillard reaction product 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural to strong muta gens via allylic sulfonation and chlorination. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1994, 7, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan-García, A.; Caprioli, G.; Sagratini, G.; Mañes, J.; Juan, C. Coffee Silverskin and Spent Coffee Suitable as Neuroprotectors against Cell Death by Beauvericin and α-Zearalenol: Evaluating Strategies of Treatment. Toxins 2021, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzesik, M.; Bartosz, G.; Stefaniuk, I.; Pichla, M.; Namieśnik, J.; Sadowska-Bartosz, I. Dietary antioxidants as a source of hydrogen peroxide. Food Chem. 2019, 278, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Kusama, K.; Satoh, K.; Takayama, E.; Watanabe, S.; Sakagami, H. Induction of cytotoxicity by chlorogenic acid in human oral tumor cell lines. Phytomedicine 2000, 7, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Satoh, K.; Kusama, K.; Watanabe, S.; Sakagami, H. Interaction between chlorogenic acid and antioxidants. Anticancer Res. 2000, 20, 2473–2476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mercer, J.R.; Gray, K.; Figg, N.; Kumar, S.; Bennett, M.R. The methyl xanthine caffeine inhibits DNA damage signaling and reactive species and reduces atherosclerosis in ApoE-/- mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 2461–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morii, H.; Kuboyama, A.; Nakashima, T.; Kawai, K.; Kasai, H.; Tamae, K.; Hirano, T. Effects of instant coffee consumption on oxidative DNA damage, DNA repair, and redox system in mouse liver. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, H155–H161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.-H. Pleiotropic Effects of Caffeine Leading to Chromosome Instability and Cytotoxicity in Eukaryotic Microorganisms. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Ambrosio, S.M. Evaluation of the genotoxicity data on caffeine. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1994, 19, 243–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.-Z.; Lai, C.-Y.; Chan, W.-H. Caffeine induces cell death via activation of apoptotic signal and inactivation of survival signal in human osteoblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008, 9, 698–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinidis, N.; Franke, H.; Schwarz, S.; Lachenmeier, D.W. Risk Assessment of Trigonelline in Coffee and Coffee By-Products. Molecules 2023, 28, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Cheng, Y.; Tang, Z.; Chen, J.; Xia, Y.; Xu, C.; Cao, X. Potential Mechanisms of Methylglyoxal-Induced Human Embryonic Kidney Cells Damage: Regulation of Oxidative Stress, DNA Damage, and Apoptosis. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.J.; Dubin, N.; Kurland, D.; Ma, B.L.; Roush, G.C. The effects of hydrogen peroxide on DNA repair activities. Mutat. Res. 1995, 336, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, N.; Kitts, D.D. Antioxidant property of coffee components: Assessment of methods that define mechanisms of action. Molecules 2014, 19, 19180–19208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, M.A.; Patel, D.; Das, A.; Tipparaju, S.R.; Shinde, S.S.; Anderson, R.F. Inhibition of radical-induced DNA strand breaks by water-soluble constituents of coffee: Phenolics and caffeine metabolites. Free Radic. Res. 2013, 47, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, W.W.; Prustomersky, S.; Delbanco, E.; Uhl, M.; Scharf, G.; Turesky, R.J.; Thier, R.; Schulte-Hermann, R. Enhancement of the chemoprotective enzymes glucuronosyl transferase and glutathione transferase in specific organs of the rat by the coffee components kahweol and cafestol. Arch. Toxicol. 2002, 76, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettler, U.; Volz, N.; Pahlke, G.; Teller, N.; Kotyczka, C.; Somoza, V.; Stiebitz, H.; Bytof, G.; Lantz, I.; Lang, R.; et al. Coffees rich in chlorogenic acid or N-methylpyridinium induce chemopreventive phase II-enzymes via the Nrf2/ARE pathway in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakuradze, T.; Boehm, N.; Janzowski, C.; Lang, R.; Hofmann, T.; Stockis, J.-P.; Albert, F.W.; Stiebitz, H.; Bytof, G.; Lantz, I.; et al. Antioxidant-rich coffee reduces DNA damage, elevates glutathione status and contributes to weight control: Results from an intervention study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2011, 55, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bøhn, S.K.; Blomhoff, R.; Paur, I. Coffee and cancer risk, epidemiological evidence, and molecular mechanisms. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2014, 58, 915–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, Y.P.; Jeong, H.G. The coffee diterpene kahweol induces heme oxygenase-1 via the PI3K and p38/Nrf2 pathway to protect human dopaminergic neurons from 6-hydroxydopamine-derived oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 2655–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, R.; Lu, Y.; Bowman, L.L.; Qian, Y.; Castranova, V.; Ding, M. Inhibition of activator protein-1, NF-kappaB, and MAPKs and induction of phase 2 detoxifying enzyme activity by chlorogenic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 27888–27895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettler, U.; Sommerfeld, K.; Volz, N.; Pahlke, G.; Teller, N.; Somoza, V.; Lang, R.; Hofmann, T.; Marko, D. Coffee constituents as modulators of Nrf2 nuclear translocation and ARE (EpRE)-dependent gene expression. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Test Material | Studies Showing Genotoxic Effects a | Studies Showing No Effects a | Studies Showing Antimutagenic Effects a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee cherry | – | [32] | – |

| Green coffee beans | – | [15,33,34,35,36] | [35] |

| Roasted coffee beans | [15,33,34,37,38,39] | [39,40] | – |

| Caffeinated instant coffee | [15,18,19,33,36,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] | [25,41,53,54,55] | [19,25,55] |

| Caffeine-free instant coffee | [15,18,36,42,46] | [25] | [25] |

| Caffeinated drip dark roasted coffee Decaffeinated drip coffee | [18] | – | – |

| Ground coffee | [43] | [56] | – |

| Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee | – | [57] | [57,58] |

| Metal filtered coffee | [59] | [59] | [59] |

| Boiled coffee | – | [25] | [25] |

| Brewed coffee | [42,45,46,60,61] | [53,54,60,62] | |

| Silverskin extract | – | [63] | [63] |

| Spent coffee grounds | [64] | [62,65] | [62,65] |

| Water-insoluble fraction of coffee | – | [16] | [16] |

| HHQ | [66] | – | – |

| Trigonelline | [67] | [68] | – |

| Caffeic acid | [43,68,69,70] | [41,68,69,71] | – |

| Chlorogenic acid | [20,43,68,69,70,72,73,74,75,76,77,78] | [35,68,69,71,72,79,80,81] | [35] |

| Pyrazine | – | [68] | – |

| Mangiferin | [82] | [82] | – |

| Glyoxal | [43,83,84,85,86] | [87] | – |

| Methylglyoxal | [43,44,83,84,86] | – | – |

| Caffeine | – | [41,42,43,44,88] | – |

| H2O2 | [43,52,89] | – | – |

| Coffee aroma | [42,90] | [90] | – |

| Cafestol palmitate | – | [91] | [91] |

| Cafestol and kahweol | – | [91] | [91,92] |

| Quinic acid | [69] | [69] | – |

| HMF | [84,85,93,94,95,96] | [87,93,94,97] | – |

| Furfuryl alcohol | [84,85,96] | – | – |

| Acetol | [84] | [87] | – |

| Diacetyl | [84] | [87] | – |

| Maillard reaction products | [98] | – | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monazzah, M.; Lachenmeier, D.W. Genotoxicity of Coffee, Coffee By-Products, and Coffee Bioactive Compounds: Contradictory Evidence from In Vitro Studies. Toxics 2025, 13, 409. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13050409

Monazzah M, Lachenmeier DW. Genotoxicity of Coffee, Coffee By-Products, and Coffee Bioactive Compounds: Contradictory Evidence from In Vitro Studies. Toxics. 2025; 13(5):409. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13050409

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonazzah, Maryam, and Dirk W. Lachenmeier. 2025. "Genotoxicity of Coffee, Coffee By-Products, and Coffee Bioactive Compounds: Contradictory Evidence from In Vitro Studies" Toxics 13, no. 5: 409. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13050409

APA StyleMonazzah, M., & Lachenmeier, D. W. (2025). Genotoxicity of Coffee, Coffee By-Products, and Coffee Bioactive Compounds: Contradictory Evidence from In Vitro Studies. Toxics, 13(5), 409. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13050409